-

Watermelon [Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai var. lanatus], originally from Africa, is a member of the Cucurbitaceae family and constitutes an economically significant crop in China[1]. Grafting technology has become instrumental in addressing the challenges of continuous cropping, enhancing plant stress tolerance, and achieving high yields in watermelon cultivation[2]. Despite the growth in protected cultivation and the increased area dedicated to watermelon farming, grafted watermelons only represent about 20% of the cultivation area in China[3], primarily due to a shortage of suitable rootstocks. These rootstocks are in demand for their compatibility, quality, and multi-resistance to diseases such as fusarium wilt and anthracnose, as well as to adverse conditions like low temperatures and insufficient light.

The selection of rootstocks is paramount for successful watermelon grafting and achieving high yields. The ideal rootstocks should exhibit strong compatibility with the scion, resistance to soil-borne pathogens, vigorous growth, and promote high yields without compromising fruit quality[4]. Currently, the rootstocks used in watermelon production encompass wild watermelon (C. lanatus subsp. lanatus), citron watermelon (C. amarus), C. colocynthis, pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima), butternut squash (C. moschata), hybrids of C. maxima × C. moschata, and bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria Standl.)[5−7]. Among these, hybrids of C. maxima × C. moschata and L. siceraria are preferred for their positive impact on fruit yield and quality[8]. Watermelon grafting significantly influences fruit quality, with varying outcomes[9−12]. Grafts involving Lagenaria hybrids show high survival rates[13]. Compared to non-grafted watermelons, those grafted onto bottle gourd and pumpkin rootstocks, particularly the latter, have larger single fruit weights but lower total soluble solid content (TSS) and taste quality[14]. Contrary findings suggest that grafting onto interspecific hybrid squash and gourd rootstocks does not adversely affect fruit quality, including TSS, titratable acidity, pH, and sensory properties[11,15]. The variability in fruit quality of grafted watermelons may be attributed to environmental conditions, rootstock-scion combinations, and delayed ripening[4,14]. Consequently, further research is necessary to understand the effects of scion-rootstock interactions on fruit quality in watermelon.

Watermelon is widely consumed for its refreshing quality, and its fruit flavor quality is a crucial determinant of its market value[16]. The unique aroma profile of watermelon, attributed to its aromatic volatiles, has significant sensory value, enhancing consumer appeal and differentiating it in the marketplace[17]. These aroma compounds, a complex blend of volatiles including alcohols, aldehydes, aromatic hydrocarbons, ketones, and terpenes, are integral to the sensory experience of watermelon[18]. In watermelon juice, the dominant aromatic volatiles are primarily C6 and C9 alcohols, aldehydes, and ketones, which are characterized by their low olfactory thresholds[19]. Grafting has been shown to significantly modify volatile composition. For example, citron melon-grafted watermelons displayed only minor changes in their volatile profiles compared to non-grafted ones[20]. Guler et al.[21] found that among various local and commercial bottle gourd rootstocks, two local bottle gourds were identified as the most suitable for yielding desirable volatile compounds in grafted watermelon, particularly affecting the concentrations of (Z)-6-nonenal and 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one. Furthermore, watermelons grafted onto pumpkin interspecific hybrids exhibited increased levels of (E)-2-nonenal compared to those that were not grafted[22].

Current research on the impact of various rootstocks on grafted watermelon fruit quality has predominantly examined parameters such as fruit weight, firmness, soluble sugars, organic acids, vitamin C, and carotenoids[10,22−29]. Comparative studies on the aroma quality of watermelons grafted onto different rootstocks, however, are less common. Moreover, identifying rootstock-scion combinations that enhance the sensory quality of grafted watermelons remains a significant challenge. In this study, headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) techniques were employed to analyze the volatile compounds in the 'Ningnongke huadai' watermelon grafted onto 11 commercial rootstocks, which include wild watermelon, bottle gourd, and pumpkin. How grafting impacts fruit quality traits was also assessed. The present findings illuminate the influence of these rootstock types on the sensory quality attributes of watermelon and provide an empirical foundation for selecting optimal rootstocks in watermelon cultivation.

-

The study was conducted in a plastic tunnel at the Ningxia Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences in Yinchuan, China, during the spring of 2021. The scion used was the commercial watermelon variety 'Ningnongke huadai,' with a selection of three wild watermelons, two bottle gourds, and six pumpkin rootstocks (Table 1). Rootstock seeds were planted 5 d before the scion seeds in an organic substrate using polystyrene trays. Grafting was performed using the hole insertion method at the emergence of the first true leaf, following the procedure outlined by Guan & Zhao[30]. Standard horticultural practices for drip irrigation, fertilization, and pest management were adhered to. Plants were spaced at 1.0 m between rows and 0.5 m within rows. Only one fruit per plant was allowed to develop, selected from the same node. The experimental design was a randomized complete block with three replicates, each consisting of 20 plants. Fruits were harvested upon reaching visual maturity, indicated by senescent tendrils, ground spot color, and external fruit color. In total, six fruits from each replicate (18 fruits per grafting combination) were collected at maturity in June 2021, transported to the laboratory at a controlled low temperature, and immediately processed for sampling.

Table 1. Eleven rootstocks for 'Ningnongke huadai' watermelon.

Rootstock Abbreviation Type Yongshi YS Wild watermelon (Citrullus lanatus subsp. Lanatus) Ningzhen 101 NZ101 Wild watermelon (Citrullus lanatus subsp. Lanatus) Yezhuang 1 YZ1 Wild watermelon (Citrullus lanatus subsp. Lanatus) Jingxinzhen 1 JX1 Bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria Standl.) Sizhuang 111 SZ111 Bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria Standl.) Jingxinzhen 2 JX2 Pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima × Cucurbita moschata) Zhuangshi ZS Pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima × Cucurbita moschata) Ningzhen 1 NZ1 Pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima × Cucurbita moschata) Mingxiu MX Pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima × Cucurbita moschata) Jinchengxuefeng JC Pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima × Cucurbita moschata) Qingyou 1 QY1 Pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima × Cucurbita moschata) Chemicals and reagents

-

Hexane, ethanol, and sodium chloride were procured from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The internal standard, 3-hexanone, and the n-alkanes standard mix (C8−C20) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA). Thirty-six authentic standards were sourced from three companies: Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd., Rhawn Co., Ltd., and ZZBIO Co., Ltd., all located in Shanghai, China. These standards were solubilized in ethanol for subsequent GC-MS analysis.

Measurement of fruit quality characteristics

-

The quality characteristics of each fruit (18 fruits per grafting combination) were assessed, including weight (kg), dimensional attributes such as length and width (cm), rind thickness (cm), and firmness of both rind and flesh (kg/cm²). Additionally, soluble solids content was measured at both central and edge locations (°Brix). Fruit weight was determined using an electronic balance, while dimensions and rind thickness were gauged with a vernier caliper. Firmness was evaluated in the watermelon's rind and central flesh, excluding seed locations, using an FT 011 penetrometer (Effegi, Japan). The concentration of soluble solids was quantified using a PAL-1 handheld digital refractometer (ATAGO, Japan), taking readings at the fruit's central flesh and 1 cm from the rind edge.

Extraction of volatiles and GC-MS analysis

-

For each replicate, six mature fruits were harvested. The central flesh from these fruits was combined, finely chopped, and homogenized to prepare a uniform sample. Samples were immediately frozen at −20 °C until analysis. Volatile compounds extraction from the watermelon samples employed the HS-SPME method as outlined by Yu et al[31]. In a 20 mL headspace vial, 6 mL of watermelon juice and 1.5 g of sodium chloride were mixed thoroughly. To this mixture, 6 μL of 3-hexanone (0.163 g/L), serving as an internal standard was added. The vial was then sealed with a magnetic crimp cap and a silicone/PTFE septum (Gerstel, Linthicum, MD, USA). Vials were placed into an autosampler (Model MPS2, Gerstel) with a cooling holder (Laird Tech, Gothenburg, Sweden). The samples were incubated at 40 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, a triphase SPME fiber (50/30 μm DVB/CAR/PDMS; Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) was exposed to the headspace for 60 min at the same temperature to absorb analytes. The SPME fiber was then inserted into the injection port of a GC (7890B, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) interfaced with a Time-of-Flight MS (LECO, Saint Joseph, MI, USA), where it was equipped with a DB-5 column (30 m × 0.25 μm × 0.25 μm, Rxi-5 Sil MS, Restek, Bellefonte, PA, USA). The volatile compounds were desorbed at 250 °C for 5 min. The GC oven temperature began at 40 °C, held for 5 min, then ramped up to 230 °C at 3 °C/min, followed by an increase to 260 °C at 15 °C/min, and maintained at 260 °C for a final 5 min. Helium served as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1 mL/min. The MS operated with an electron ionization energy of 70 eV, scanning from 30 to 500 m/z, with the ion source kept at 230 °C.

Identification of volatile compounds

-

Volatile compounds in watermelon flesh were identified by comparing their mass spectra and retention time against those of authentic standards or by referencing retention indices (RIs) and mass spectra from the NIST05.L (National Institute of Standards and Technology Mass Spectral Library, Gaithersburg, MA, USA) and ADAMS.L[32]. The RIs for these compounds were determined using a series of n-alkane standards (C8−C20) and were calculated daily under consistent conditions. The relative content of each volatile compound, including both identified and unidentified peaks was quantified by comparing its peak area with that of the internal standard.

Statistical analysis

-

The study employed a completely randomized design, with three replicates per grafting combination. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), JMP Pro 13 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA), and Origin 8.0 (Origin, Northampton, MA, USA). Comparative profiles of volatile compounds from different rootstock-scion combinations were illustrated using Venn diagrams and Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA), based on Ward's method, was conducted using R software (v4.2.1) to discern patterns in the volatile profiles across combinations. Significant differences were assessed using one-way ANOVA, Student's t-test, and Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference test, with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

-

Grafting significantly influenced watermelon quality traits, including fruit weight and length, rind thickness, flesh firmness, and central soluble solids (Table 2). Consistent with previous studies[33,34], grafting onto Cucurbita spp., Lagenaria spp., and Citrullus spp. rootstocks increased average fruit weight. Specifically, pumpkin-grafted watermelons (11.5−14.22 kg) weighed more than non-grafted ones (NG, 10.41 kg). Pumpkin rootstocks enhanced leaf photosynthesis and increased expression levels of ClCWIN4, ClAGA2, and ClVST1, as well as CWIN activity, contributing to weight gain[35]. Rind thickness, crucial for transport, was reduced in watermelons grafted onto 'Zhuangshi' (ZS, 0.73 cm), 'Jingxinzhen 2' (JX2, 0.75 cm), and 'Ningzhen 1' (NZ1, 0.66 cm) compared to NG (1.05 cm). In contrast, watermelons grafted onto wild rootstocks, such as 'Yongshi' (YS, 1.15 cm), 'Ningzhen 101' (NZ101, 1.13 cm), and 'Yezhuang 1' (YZ1, 1.3 cm), had thicker rinds. While citron or Cucurbita rootstocks increased rind thickness and fruit size compared to NG[20], but this study found that wild watermelon rather than pumpkin rootstocks led to even larger fruits with thicker rinds.

Table 2. Fruit quality characteristics of 'Ningnongke huadai' watermelon grafted onto different rootstocks.

Type NG Wild watermelon Bottle gourd Pumpkin NZ101 YS YZ1 JX1 SZ111 JC MX QY1 ZS JX2 NZ1 Fruit weight (kg) 10.41h 11.76ef 12.01de 10.94fgh 11.36efg 10.78gh 14.22a 14.08a 12.64cd 13.54ab 11.50efg 12.97bc Fruit length (cm) 22.62cd 24.17bcd 23.77cd 26.32ab 23.50cd 22.80cd 27.12a 24.38bc 23.97bcd 21.81d 23.78cd 23.30cd Fruit width (cm) 29.65c 32.99abc 31.98abc 31.38bc 35.00ab 34.05abc 35.68ab 37.03a 35.15ab 31.33bc 35.61ab 34.55abc Rind thickness (cm) 1.05bc 1.13b 1.15b 1.30a 1.12b 0.95cd 0.87def 0.92cd 0.88de 0.73fg 0.75efg 0.66g Rind firmness (kg/cm2) 15.21abc 16.65a 14.69bc 14.90abc 14.56bcd 16.02ab 14.90abc 14.88bc 14.02cd 12.82d 15.84ab 14.32bcd Flesh firmness (kg/cm2) 0.63e 0.53e 0.59e 0.61e 0.77cde 0.70de 1.03ab 0.97abc 1.19a 1.08ab 0.93bcd 1.14ab Central soluble solids (°Brix) 11.30bcd 12.17a 11.93ab 11.67abc 10.40ef 10.80def 9.98f 10.48def 10.30ef 10.85cde 10.72def 10.87cde Edge soluble solids (°Brix) 8.05abc 8.02abc 8.40a 7.47bc 7.65abc 7.72abc 8.17abc 7.43bc 7.37c 7.83abc 8.27ab 8.42a All values are mean of three biological replicates (six fruits each) per grafting combination. Distinct letters within the same row indicate statistically significant differences, as determined by Student's t test at p < 0.05. Pumpkin rootstocks, specifically 'Qingyou 1' (QY1, 1.19 kg/cm²), ZS (1.08 kg/cm²), and NZ1 (1.14 kg/cm²), significantly enhanced flesh firmness in watermelon compared to NG (0.63 kg/cm²). Flesh firmness is a critical sensory attribute of watermelon quality, with numerous studies documenting increased firmness in grafted fruits[5,12,36,37]. TSS is key to consumer acceptance. Wild watermelon-grafted fruits had the highest TSS, ranging from 11.67 °Brix in YZ1 to 12.17 °Brix in NZ101. Conversely, bottle gourd- (10.4−10.8 °Brix) and pumpkin-grafted (9.98−10.87 °Brix) watermelons had lower central soluble solids compared to NG (11.3 °Brix). The effects of grafting on watermelon TSS vary across rootstock-scion combinations. Citrullus spp. rootstocks increase, while Lagenaria spp. rootstocks decrease, TSS in watermelon 'NS-295'[34]. Sun et al.[35] found that C. maxima × C. moschata rootstocks altered sugar profiles by increasing glucose and fructose and reducing sucrose, likely due to up-regulated ClVIN2 expression and increased VIN activity. Several genes related to glucose and sucrose metabolism (FBA2, FK, SuSy, SPS, IAI, AI, SWT3b) may play a central role in regulating TSS in pumpkin-grafted watermelon[3].

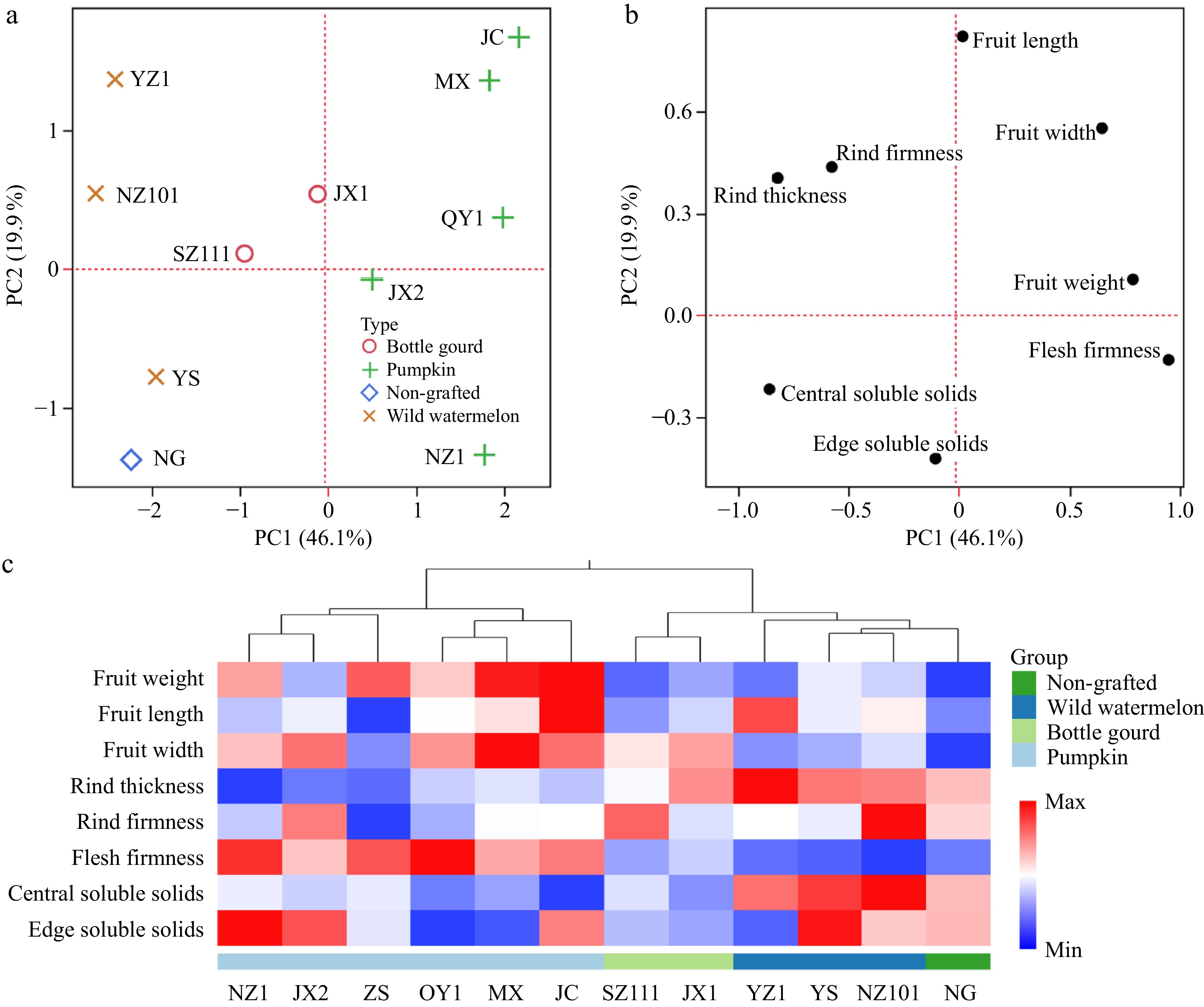

PCA and HCA were utilized to assess differences in fruit quality between NG and their grafted counterparts. PC1 accounted for 46.1% of the variance, effectively separating pumpkin-grafted watermelons from NG and other grafted types based on flesh firmness, central soluble solids, and fruit weight (Fig. 1a & b). HCA also grouped all pumpkin-grafted watermelons into a distinct cluster (Fig. 1c). Wild watermelon-grafted fruits excelled in TSS, while pumpkin-grafted watermelons had better texture and size but lower TSS, supporting previous findings[38,39].

Figure 1.

PCA and HCA of fruit characteristics for 'Ningnongke huadai' watermelon grafted onto various rootstocks. (a) PCA score, and (b) loading plots of fruit characteristics. (c) HCA of fruit characteristics. Each row in the figure corresponds to a distinct fruit trait and each column to a specific sample. The color gradient represents the relative magnitudes of the fruit characteristics across the sample groups. The dendrogram at the top indicates the clustering of samples, with the sample names listed below.

Fruit volatile profile of NG watermelon

-

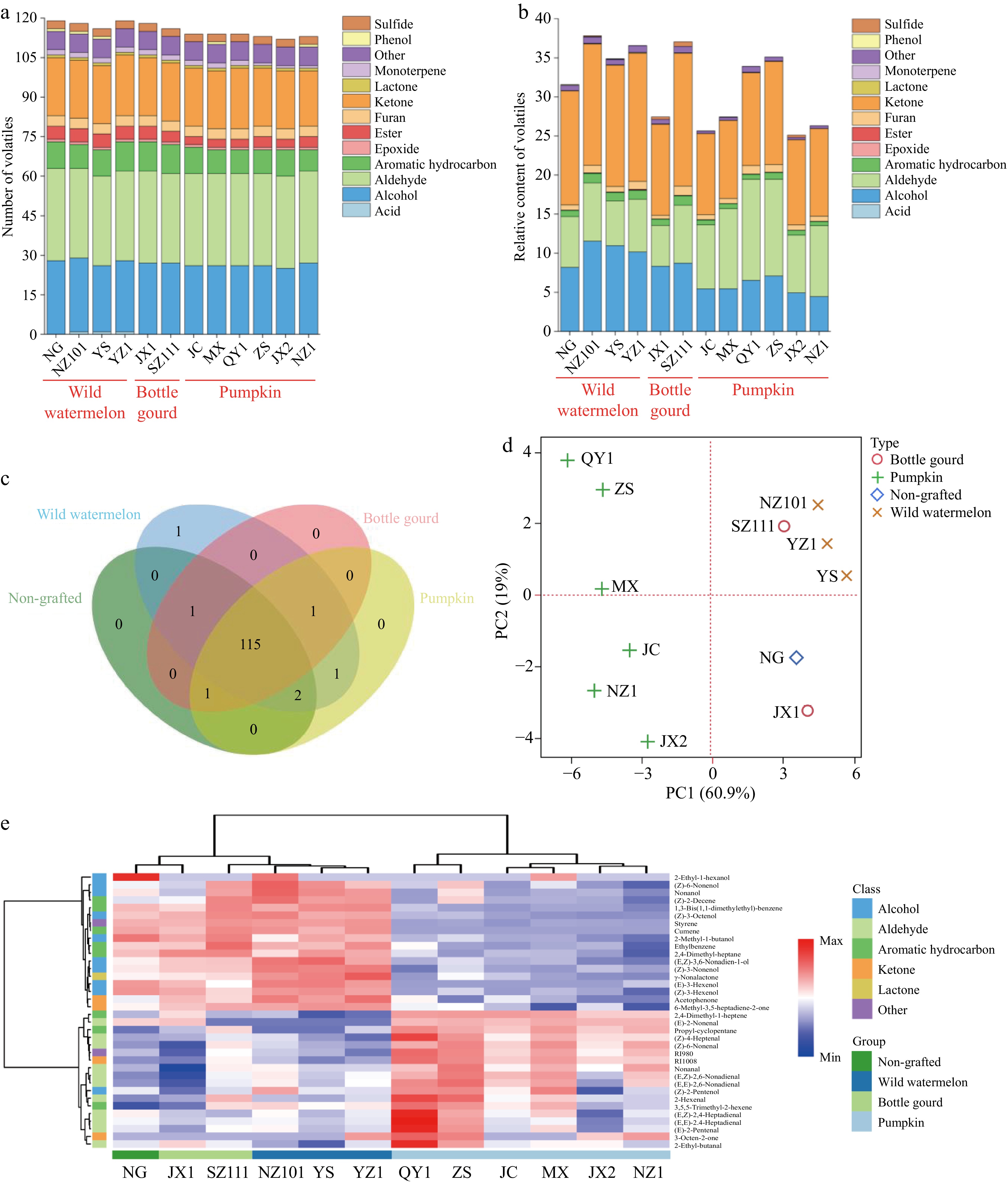

HS-SPME coupled with GC-MS facilitated the extraction and quantification of volatile constituents within the watermelon flesh. A spectrum of 122 volatile compounds was identified, comprising one acid, 28 alcohols, 35 aldehydes, 10 aromatic hydrocarbons, one epoxide, five esters, four furans, 20 ketones, one lactone, two monoterpenes, one phenol, and three sulfides (Tables 3 & 4, Fig. 2a). These compounds align with those previously reported in watermelon literature[40,41]. Predominantly, ketones were the most prevalent group, with 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one ranging from 8.68 to 15.05, contributing to the characteristic herbaceous, fruity, and oily green aromas (Tables 3 & 5, Fig. 2b). This ketone is speculated to arise from the degradation of lycopene, a highly unstable carotenoid abundant in watermelon[20,42]. Geranyl acetone (0.84−1.67), the subsequent most abundant ketone, noted for its floral and fruity scent, is a byproduct of β-carotene breakdown. Despite their abundance, neither 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one nor geranyl acetone significantly contribute to watermelon aroma due to their high odor thresholds, at 50 μg/L and 186 μg/L, respectively[43]. Additionally, β-ionone, with its violet-like fragrance, was detected and is also a metabolite of β-carotene catabolism[43].

Table 3. Volatile compounds of 'Ningnongke huadai' watermelon grafted onto different rootstocks.

Code Compound Class RI (Caculated) RI (Published)b NG NZ101 YS YZ1 JX1 SZ111 JC MX QY1 ZS JX2 NZ1 3 2-methyl-1-butanol alcohol 726 724 0.14z 0.08zy 0.11zy 0.10zy 0.11zy 0.13zy 0.05zy 0.05zy 0.05zy 0.06zy 0.04zy 0.04y 6 dimethyl disulfide sulfide 728 785c 0.02 0.06 0.04 0.02 0.22 0.39 0.02 0.03 0.02 tr 0.19 tr 10 2-methyl-3-pentanone ketone 731 745d 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.04 0.02 0.01 0.01 13 (E)-2-pentenala aldehyde 734 744 0.07zy 0.08zy 0.07y 0.07zy 0.06y 0.08zy 0.07zy 0.09zy 0.16z 0.11zy 0.06y 0.07zy 17 pentanola alcohol 741 762 0.26 0.25 0.19 0.23 0.19 0.19 0.17 0.18 0.29 0.24 0.15 0.18 20 (Z)-2-pentenola alcohol 743 765 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 tr 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 tr 0.01 21 2-methyl-3-pentanol alcohol 745 775d tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 29 2-methyl-4-pentenal aldehyde 757 793d tr tr tr 0.01 tr 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.02 tr tr 31 2,3-butanediol alcohol 760 785 tr 0.02 nd 0.04 tr 0.01 0.03 0.01 0.03 0.02 nd 0.01 33 hexanala aldehyde 764 801 2.88zy 2.86zy 2.02y 2.56zy 2.52zy 2.90zy 2.93zy 2.97zy 5.35z 3.91zy 2.75zy 2.70zy 38 2,4-dimethyl-heptane aromatic hydrocarbon 783 822d tr tr tr tr 0.01 0.01 tr tr tr tr tr tr 41 pentyl formate ester 789 797d tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 43 propylcyclopentane aromatic hydrocarbon 792 834d ndx ndx ndx tryx trx tryx trzyx 0.01zy 0.01z trzyx tryx trzyx 47 2-ethyl-butanal aldehyde 797 762d 0.02y 0.01y 0.01y 0.02y 0.03zy 0.02zy 0.02y 0.02zy 0.06z 0.03zy 0.02zy 0.02y 48 2,4-dimethyl-1-heptene aromatic hydrocarbon 801 840d tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 50 (E)-2-hexenala aldehyde 807 846 tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 51 (E)-3-hexenol alcohol 812 844 trzyx 0.01zy 0.01z trzyx trzy trx ndx ndx ndx ndx ndx trx 52 2-hexenal aldehyde 813 856c 0.08y 0.10y 0.09y 0.11y 0.09y 0.15zy 0.12zy 0.14zy 0.22z 0.19zy 0.11y 0.10y 53 1-(2-methyl-1-cyclopenten-1-yl)-ethanone ketone 813 tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 0.01 tr tr tr 55 (Z)-3-hexenola alcohol 816 850 0.22z 0.21z 0.23z 0.19z 0.18z 0.13zy 0.04y 0.06y 0.04y 0.07y 0.05y 0.03y 60 ethylbenzenea aromatic hydrocarbon 819 850d 0.11zy 0.13zy 0.12zy 0.15zy 0.12zy 0.18z 0.06y 0.07y 0.10zy 0.06y 0.07zy 0.05y 61 4-methyl-octane aromatic hydrocarbon 825 863d tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr nd 65 hexanola alcohol 832 863 1.12 0.93 0.69 0.88 1.03 0.69 0.54 0.39 0.83 0.64 0.55 0.33 70 styrenea other 851 893c 0.33zy 0.45z 0.43z 0.51z 0.31zy 0.51z 0.02y 0.03y 0.02y 0.03y 0.02y 0.02y 73 2-heptanonea ketone 853 889 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.04 0.01 0.01 tr 75 2-butylfuran furan 854 892d 0.01 0.01 tr 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.03 0.02 0.01 tr 80 (Z)-4-heptenal aldehyde 864 893 try try try try try trzy trzy 0.01zy 0.02z 0.01zy 0.01zy 0.01zy 82 heptanala aldehyde 866 901 0.16 0.14 0.10 0.14 0.10 0.13 0.12 0.13 0.34 0.20 0.12 0.11 84 methional sulfide 871 909c tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 85 (E,E)-2,4-hexadienala aldehyde 876 907 tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 89 amyl acetate ester 883 911 tr tr tr 0.01 tr 0.01 tr tr 0.01 0.01 tr tr 92 cumene aromatic hydrocarbon 889 924 trzy trz trzy trz trzy trz ndy ndy ndy ndy ndy ndy 102 4-methyl-2-heptanone ketone 908 918 tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 106 RI918 other 918 0.04zy 0.03zy 0.02y 0.04zy 0.05zy 0.04zy 0.03zy 0.04zy 0.11z 0.05zy 0.04zy 0.03zy 110 6-methyl-2-heptanone ketone 929 955d 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.01 111 (E)-2-heptenala aldehyde 931 947 0.13 0.12 0.10 0.13 0.10 0.10 0.09 0.09 0.22 0.14 0.08 0.09 113 benzaldehydea aldehyde 933 952 0.05 0.07 0.05 0.06 0.09 0.06 0.05 0.06 0.14 0.07 0.05 0.04 116 dimethyl trisulfidea sulfide 939 974c 0.01 0.05 0.02 0.01 0.11 0.20 0.02 0.02 0.01 tr 0.11 tr 117 2-methyl-1-hepten-6-one ketone 943 966d 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 tr tr 0.01 0.01 0.01 tr 118 (Z)-3-heptenol alcohol 944 959d 0.02 0.01 tr tr 0.01 tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 119 (E)-2-heptenola alcohol 948 958 tr tr nd tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 121 heptanola alcohol 952 959 0.15 0.11 0.06 0.09 0.09 0.07 0.06 0.05 0.15 0.09 0.06 0.04 122 3,5,5-trimethyl-2-hexene aromatic hydrocarbon 954 968d try 0.02zy 0.01zy 0.01zy try 0.02zy 0.01zy 0.02zy 0.02z 0.02zy 0.01zy 0.01y 123 1-octen-3-one ketone 957 972 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.03 0.02 0.02 0.02 127 1-octen-3-ol alcohol 965 974 0.42 0.50 0.41 0.54 0.39 0.47 0.35 0.34 0.72 0.51 0.35 0.32 128 phenol phenol 968 980c 0.08 0.05 0.05 nd nd nd nd 0.02 nd nd nd 0.01 129 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-onea ketone 969 981 13.09 13.80 13.98 14.53 10.54 15.05 9.19 8.68 10.15 11.61 9.72 9.76 131 3-octanonea ketone 970 979 0.04 0.05 0.04 0.05 0.03 0.04 0.04 0.05 0.10 0.06 0.04 0.04 133 2-pentylfuran furan 973 984 0.61 0.89 0.62 0.93 0.42 1.09 0.58 0.63 1.01 0.89 0.62 0.61 136 1-cyclohexyl-ethanone ketone 978 963d tr tr 0.01 0.01 tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 137 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-ola alcohol 978 989 0.05 0.04 0.06 0.09 0.04 0.07 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.04 0.02 0.02 138 (E,Z)-2,4-heptadienal, aldehyde 980 1,000c 0.06zy 0.06zy 0.05y 0.06zy 0.05y 0.05y 0.06zy 0.07zy 0.14z 0.08zy 0.04y 0.06zy 139 RI980 other 980 0.03yx 0.03yx 0.02yx 0.01x 0.01x 0.04yx 0.06zyx 0.09zyx 0.16z 0.12zy 0.05yx 0.07zyx 141 trans-2-(2-pentenyl)furan furan 983 984d tr 0.01 0.01 0.01 tr 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.01 tr 142 hexanoic acid acid 985 967 nd tr tr tr nd nd nd nd nd nd nd nd 144 octanala aldehyde 989 998 0.27 0.29 0.20 0.26 0.15 0.22 0.25 0.28 0.60 0.46 0.23 0.28 149 (E,E)-2,4-heptadienal aldehyde 997 1,005 0.09y 0.09y 0.07y 0.08y 0.07y 0.08y 0.08y 0.09y 0.31z 0.14zy 0.05y 0.07y 152 hexyl acetatea ester 1,002 1,007 tr tr tr 0.01 tr tr nd nd nd tr nd nd 154 RI1008 ketone 1,008 trw trw trw trw trw 0.01xw 0.02yxw 0.03zyx 0.05z 0.03zy 0.02yxw 0.02yxw 155 3-ethyl-4-methylpentanol alcohol 1,011 1,023d tr tr tr tr tr tr tr nd tr tr tr tr 156 p-cymene monoterpene 1,012 1,020 tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr nd nd nd 158 RI1018 aromatic hydrocarbon 1,017 0.01 nd 0.01 0.01 tr 0.02 tr nd nd nd tr nd 159 limonenea monoterpene 1,018 1,024 0.01zy 0.01zy try 0.01zy try 0.01zy 0.01zy 0.01zy 0.04z 0.02zy trzy 0.01zy 161 (Z)-2-decene aromatic hydrocarbon 1,020 1,009d 0.57zyx 0.98z 0.84zyx 0.86zyx 0.61zyx 0.91zy 0.49zyx 0.49zyx 0.46yx 0.72zyx 0.48yx 0.40x 163 2-ethyl-1-hexanola alcohol 1,022 1,032c trz trzy ndy ndy ndy ndy ndy trzy ndy ndy ndy ndy 165 2,2,6-trimethyl-cyclohexanone ketone 1,023 1,036d tr tr 0.01 0.01 tr 0.01 tr tr tr tr tr tr 166 benzyl alcohola alcohol 1,024 1,026 0.18 0.18 0.24 0.31 0.44 0.19 0.16 0.22 0.34 0.26 0.17 0.15 170 3-octen-2-one ketone 1,031 1,030 ndy ndy ndy trzy ndy ndy ndy ndy trz trzy trzy trzy 172 benzeneacetaldehydea aldehyde 1,033 1,036 0.02 0.03 0.03 0.04 0.02 0.03 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.03 0.01 0.02 175 RI1040 ketone 1,040 0.04 0.04 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.03 0.02 0.03 0.09 0.04 0.03 0.03 180 2,6-dimethyl-2,6-octadiene aromatic hydrocarbon 1,047 980d 0.03 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.02 0.03 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.03 0.02 0.03 181 bergamal aldehyde 1,049 1,051 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.02 tr 0.01 tr tr tr 0.01 tr 0.01 183 (Z)-3-octenol alcohol 1,051 1,047 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 tr tr tr tr tr tr 185 RI1053 other 1,053 0.06 0.08 0.06 0.08 0.02 0.05 0.03 0.02 0.02 0.04 0.02 0.02 187 (E)-2-octenala aldehyde 1,054 1,060c 0.09 0.09 0.07 0.10 0.06 0.06 0.05 0.05 0.13 0.08 0.04 0.06 191 acetophenone ketone 1,059 1,059 trzy trzy trzy trz trzy trzy trzy try trzy ndy ndy ndy 192 6-methyl-3,5-heptadiene-2-one ketone 1,061 1,105d trzyxw trzyx trz trzy trzyxw trzyx trxw trw tryxw trzyxw trxw ndw 195 (E)-2-octenola alcohol 1,068 1,060 0.04 0.06 0.05 0.07 0.04 0.05 0.05 0.04 0.07 0.06 0.04 0.04 196 (E,E)-3,5-octadien-2-one ketone 1,068 1,083d 0.02 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.02 0.03 0.03 0.03 0.04 0.03 0.02 0.03 199 RI1072 other 1,073 0.05 0.06 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.03 0.05 0.08 0.08 0.02 0.04 200 octanola alcohol 1,073 1,063 0.17 0.19 0.11 0.14 0.10 0.11 0.10 0.11 0.21 0.19 0.12 0.10 211 2-nonanone ketone 1,095 1,087 tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 217 (E)-4-nonenal aldehyde 1,098 1,105d tr 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 tr 0.01 223 perillene furan 1,103 1,102 0.04 0.06 0.06 0.08 0.03 0.07 0.04 0.03 0.03 0.05 0.03 0.04 227 (Z)-6-nonenal aldehyde 1,108 1,097 0.24x 0.43yx 0.30x 0.25x 0.13x 0.73zyx 0.87zyx 1.5zy 1.16zyx 1.67z 0.73zyx 1.24zyx 228 nonanala aldehyde 1,112 1,100 0.71zy 1.04zy 0.82zy 0.83zy 0.34y 1.06zy 1.04zy 1.39zy 1.28zy 1.81z 0.99zy 1.48zy 239 RI1137 other 1,137 0.16 0.15 0.10 0.16 0.14 0.13 0.08 0.10 0.29 0.16 0.10 0.11 246 RI1153 ketone 1,153 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.04 0.02 0.02 0.02 247 (E,E)-2,6-nonadienal aldehyde 1,154 1,152d 0.02zy 0.03zy 0.02zy 0.03zy 0.01y 0.02zy 0.03zy 0.03zy 0.04zy 0.04z 0.02zy 0.03zy 254 (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal aldehyde 1,166 1,150 0.54yx 0.99zyx 0.71zyx 0.89zyx 0.36x 0.86zyx 1.24zyx 1.42zy 1.28zyx 1.65z 0.70zyx 1.17zyx 256 (Z)-3-nonenol alcohol 1,176 1,152 0.29zyxw 0.48z 0.46zyx 0.48zy 0.33zyxw 0.34zyxw 0.17zyxw 0.17xw 0.15w 0.23zyxw 0.20zyxw 0.17yxw 257 (E)-2-nonenal aldehyde 1,177 1,157 0.25 nd nd nd 0.47 nd 0.59 1.29 0.68 0.94 0.82 0.80 258 (E,Z)-3,6-nonadienol alcohol 1,178 1,149 3.77yxw 5.97zy 6.32z 4.94zyx 4.35zyxw 4.42zyxw 2.73xw 2.82xw 2.71xw 3.21xw 2.32w 2.23w 259 (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienol alcohol 1,183 1,159 tr 0.03 0.02 0.05 tr 0.02 0.06 0.04 0.02 0.03 tr 0.02 261 (E)-2-nonenol alcohol 1,187 1,163 0.02 0.07 0.05 0.17 0.03 0.04 0.14 0.06 0.03 0.06 0.02 0.04 263 (Z)-6-nonenol alcohol 1,191 1,164 0.25zyx 0.50z 0.41zy 0.33zyx 0.22yx 0.39zyx 0.17yx 0.24zyx 0.22yx 0.33zyx 0.17yx 0.14x 265 nonanola alcohol 1,193 1,165 1.00zy 1.84z 1.51zy 1.41zy 0.69y 1.36zy 0.58y 0.63y 0.57y 1.02zy 0.64y 0.53y 268 1-(4-methylphenyl)-ethanone ketone 1,200 1,191c tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 277 2,4-nonadienal aldehyde 1,214 1,200c tr 0.01 tr 0.01 tr 0.01 tr tr 0.01 0.01 tr tr 286 decanala aldehyde 1,228 1,201 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.04 0.03 0.03 0.02 293 9-decenol alcohol 1,234 1,262d tr 0.01 0.01 0.02 tr 0.01 tr tr tr tr tr tr 295 (E,E)-2,4-nonadienal aldehyde 1,236 1,210 0.10 0.12 0.09 0.14 0.07 0.08 0.07 0.08 0.16 0.13 0.07 0.09 296 β-cyclocitrala aldehyde 1,238 1,217 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.02 tr 0.02 tr tr 0.01 0.01 tr 0.01 302 2-ethylhexyl acrylate ester 1,252 1,220d tr tr tr tr tr nd nd nd nd nd nd tr 304 3-methyl-3-(4-methyl-3-pentenyl)-2-oxiranecarbaldehyde aldehyde 1,254 1,236d 0.04 0.06 0.05 0.05 0.02 0.03 0.02 0.03 0.02 0.03 0.02 0.04 309 neral aldehyde 1,261 1,235 0.15 0.20 0.22 0.23 0.12 0.20 0.11 0.10 0.11 0.15 0.11 0.15 314 RI1268 other 1,268 tr tr tr tr tr tr 0.03 0.02 0.05 0.02 0.02 0.02 316 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-benzene aromatic hydrocarbon 1,272 1,249d 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.03 0.01 0.03 tr tr tr tr tr tr 317 geraniola alcohol 1,277 1,249 tr 0.01 0.01 0.01 tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 319 (E)-2-decenal aldehyde 1,288 1,260 0.04 0.04 0.03 0.04 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.04 0.03 0.01 0.02 322 geranial aldehyde 1,294 1,264 0.34 0.43 0.45 0.47 0.25 0.39 0.22 0.21 0.23 0.31 0.24 0.31 329 decanol alcohol 1,301 1,266 tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 339 (E)-2,7-octadien-1-yl acetate ester 1,323 1,388d 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.06 tr 0.02 0.02 tr tr tr tr 0.01 342 4-ethyl-2-hexynal aldehyde 1,328 0.02 0.05 0.05 0.09 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.02 tr 0.01 345 undecanal aldehyde 1,338 1,305 tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr 349 (E,E)-2,4-decadienal aldehyde 1,346 1,315 0.01 0.01 tr 0.01 tr tr tr tr 0.03 0.01 tr 0.01 358 γ-nonalactone lactone 1,386 1,358 0.03zy 0.06zy 0.07zy 0.09z 0.04zy 0.04zy 0.02y 0.02y 0.02y 0.03zy 0.02y 0.01y 359 (E)-2-undecenal aldehyde 1,395 1,357 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 tr tr tr tr 0.02 0.01 tr tr 374 geranyl acetonea ketone 1,478 1,453 1.21 1.44 1.27 1.54 0.84 1.67 0.98 1.02 1.20 1.28 0.95 1.20 377 (E)-β-ionone ketone 1,505 1,487 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.03 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 380 β-ionone epoxide epoxide 1,507 1,473d 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.03 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.02 391 trans-ψ-ionone ketone 1,601 1,589d tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr tr The volatile relative content was determined by normalizing the areas of the compound peaks to that of the internal standard. Mean values were obtained from three biological replicates for each grafting combination. Retention indices (RI) were calculated using a standard mixture of alkanes ranging from C8 to C20. The abbreviation 'RI' stands for retention index; 'tr' indicates that the peak was detected, but the value was below 0.0095; 'nd' denotes that the compound was not detected. aCompounds were identified using authentic volatile standards. bPublished RI for the DB-5 column, unless otherwise stated, were sourced from Adams[32]. cPublished RI on DB-5 column reported on Flavornet and Human Odor Space[58]. dPublished RI on DB-5 column reported on PubChem[59]. z−wDifferent letters in the same rows indicate significant differences according to Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference test at p < 0.05. Table 4. Total number of volatile compounds in each chemical class in watermelon grafted onto different rootstocks.

Class NG Type Wild watermelon Bottle gourd Pumpkin NZ101 YS YZ1 JX1 SZ111 JC MX QY1 ZS JX2 NZ1 Acid 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Alcohol 28 28 25 27 27 27 26 26 26 26 25 27 Aldehyde 35 34 34 34 35 34 35 35 35 35 35 35 Aromatic hydrocarbon 10 9 10 11 11 11 10 9 9 9 10 8 Epoxide 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Ester 5 5 5 5 5 4 3 3 3 4 3 4 Furan 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 Ketone 22 22 22 23 22 22 22 22 23 22 22 21 Lactone 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Monoterpene 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 Other 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 Phenol 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 Sulfide 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Total 119 118 116 119 118 116 114 114 114 113 112 113 Table 5. Total relative content of volatile compounds in each chemical class in watermelon grafted onto different rootstocks.

Class NG Type Wild watermelon Bottle gourd Pumpkin NZ101 YS YZ1 JX1 SZ111 JC MX QY1 ZS JX2 NZ1 Acid 0 0.01 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Alcohol 8.19abcd 11.55a 10.99ab 10.16abc 8.33abcd 8.73abcd 5.46bcd 5.47bcd 6.54abcd 7.09abcd 4.96cd 4.44d Aldehyde 6.49 7.45 5.71 6.77 5.23 7.41 8.17 10.22 12.9 12.37 7.36 9.08 Aromatic hydrocarbon 0.77ab 1.2a 1.07ab 1.12a 0.79ab 1.2a 0.6ab 0.62ab 0.63ab 0.85ab 0.6ab 0.51b Epoxide 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.03 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.02 Ester 0.03 0.04 0.04 0.1 0.02 0.04 0.03 0.02 0.02 0.03 0.01 0.02 Furan 0.67 0.97 0.71 1.03 0.46 1.19 0.64 0.69 1.09 0.97 0.68 0.66 Ketone 14.6 15.54 15.5 16.39 11.64 17 10.39 9.95 11.88 13.23 10.9 11.21 Lactone 0.03ab 0.06ab 0.07ab 0.09a 0.04ab 0.04ab 0.02b 0.02b 0.02b 0.03ab 0.02b 0.01b Monoterpene 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.04 0.02 0.01 0.01 Other 0.66 0.81 0.67 0.84 0.57 0.81 0.28 0.35 0.72 0.49 0.28 0.32 Phenol 0.08 0.05 0.05 0 0 0 0 0.02 0 0 0 0.01 Sulfide 0.03 0.11 0.06 0.04 0.33 0.6 0.04 0.06 0.04 0.02 0.3 0.01 Total 31.58 37.82 34.9 36.58 27.44 37.06 25.66 27.44 33.91 35.12 25.13 26.32 The relative content data are presented as the mean based on three biological replicates. In the same row, differing letters indicate a statistically significant difference as determined by Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference test (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Multivariate statistical analysis of volatile profiles for 'Ningnongke huadai' watermelon grafted onto different rootstocks. (a) Number, and (b) relative content of volatile compounds in each chemical class. (c) Venn diagram analysis of volatile compounds. (d) PCA score plot of volatile compounds that were identified as differentially accumulated among watermelon samples. (e) HCA of volatile compounds that were identified as differentially accumulated among watermelon samples. Each column in the figure corresponds to a sample, and each row to a volatile compound. The color coding indicates the relative content of volatile compounds in the respective sample groups. On the left, the dendrogram illustrates the clustering of volatile compounds, whereas the top dendrogram shows the clustering of samples, with sample names listed below.

Aldehydes, ranging from 5.23 to 12.9, and alcohols, between 4.44 and 11.55, were prominent volatile constituents in the watermelon samples (Table 5 & Fig. 2b). Notably, C6 and C9 aldehydes and alcohols are recognized as key aroma volatiles of the Cucurbitaceae family[7]. According to Yang et al.[44], C9 saturated and unsaturated linear aldehydes and alcohols, including (E)-2-nonenal, (Z)-2-nonenal, (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal, (Z)-3-nonenol, (E)-6-nonenol, (E,E)-3,6-nonadienol, (E,Z)-3,6-nonadienol, and (Z,Z)-3,6-nonadienol, are representative of watermelon's distinctive aroma. Additionally, aldehydes and alcohols comprised the largest groups, with 34 to 35 and 25 to 28 volatile compounds, respectively. Among the aldehydes, hexanal, nonanal, (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal, geranial, and octanal were the most abundant, with concentrations detailed in Table 3. Hexanal, a C6 aldehyde resulting from linoleic acid oxidation, imparts a green and floral aromatic quality[45]. Conversely, the C9 aldehydes, nonanal and (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal, are pivotal in defining watermelon's aroma, lending melon, citrus peel, and cucumber-like scents[46,47]. Interestingly, (Z,Z)-3,6-nonadienal was not detected in this study, although frequently reported in prior research, possibly due to its quick isomerization to (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal and (E)-2-nonenal[42].

The watermelon samples demonstrated significant levels of various alcohols, with nonanol and its homologues being particularly abundant. Concentrations of (E,Z)-3,6-nonadienol ranged from 2.23 to 6.32, while hexanol, nonanol, 1-octen-3-ol, and (Z)-3-nonenol were present in lower quantities (Table 3). (E,Z)-3,6-Nonadienol was notably the second most prevalent volatile, contributing green and cucumber-like aromas to the watermelon. This compound is especially influential in the aroma profile of fresh watermelon due to its low olfactory perception threshold[48] and is also a common constituent in the scent profiles of melons (Cucumis melo) and cucumbers (C. sativus)[49,50]. Other key aroma components in watermelon include (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal, nonanal, (Z)-3-nonenol, (E)-2-nonenal, and (Z)-6-nonenal, which are characterized by their low odor detection thresholds and thereby define the fruit's characteristic flavor[19]. Additionally, sulfides, with concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 0.6, are known for imparting the distinctive flavors of onion, garlic, cabbage, and other vegetables and may influence the flavor profile of watermelon[42,51].

Grafting effect of different rootstock types on fruit volatile profiles

-

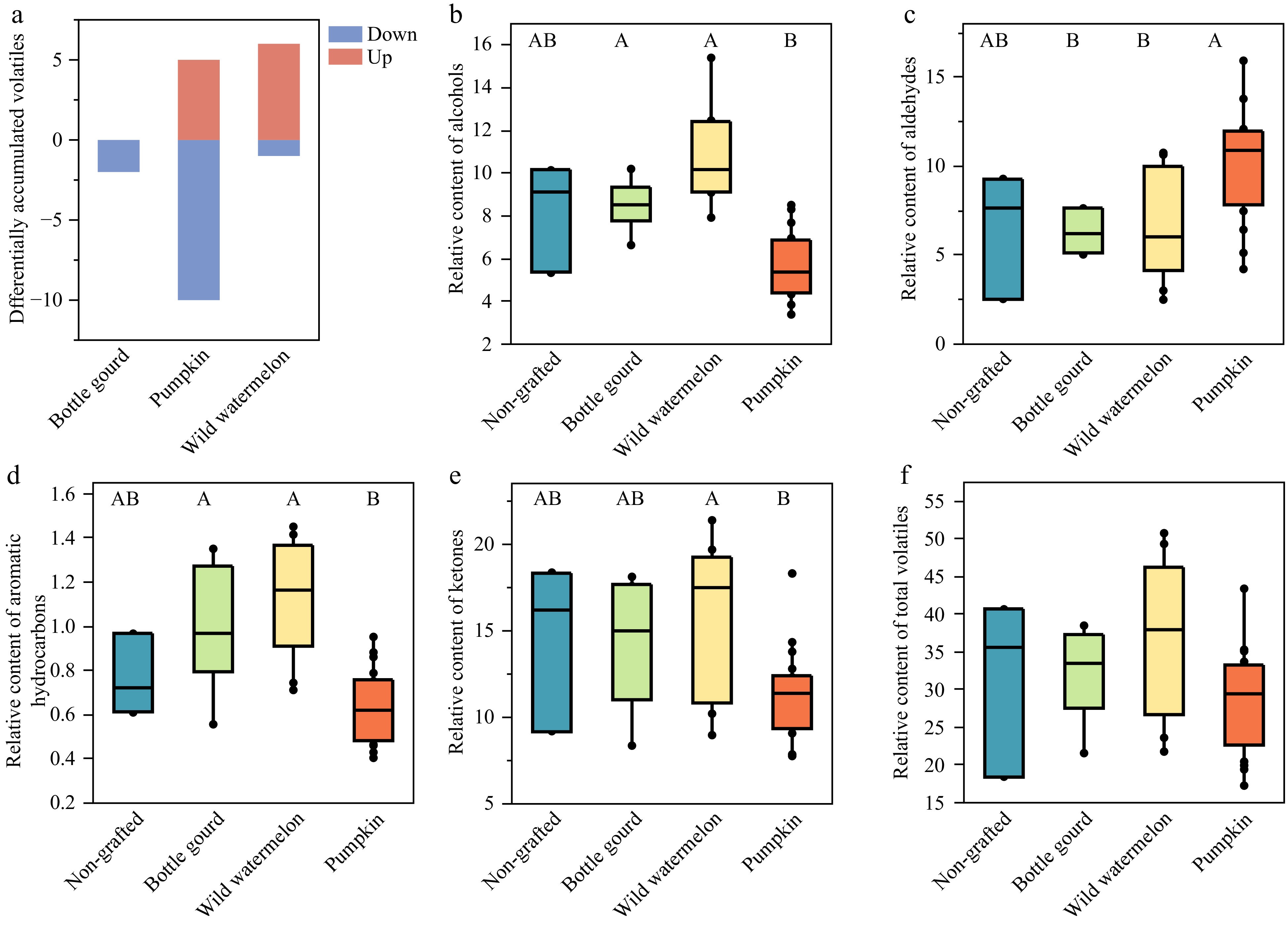

A comprehensive analysis of fruit volatile profiles revealed that 119, 121, 118, and 120 volatile compounds were identified in NG, wild watermelon-, bottle gourd-, and pumpkin-grafted watermelons, respectively. Pairwise comparisons were conducted to ascertain the differential accumulation of volatile compounds between NG and grafted watermelons, resulting in the identification of 21 distinct metabolic features (Table 6). Relative to NG, none, five and six volatile compounds were more abundantly accumulated in bottle gourd-, pumpkin- and wild watermelon-grafted fruits, respectively. Conversely, the relative content of two aroma volatiles in bottle gourd-grafted, 10 in pumpkin-grafted, and one in wild watermelon-grafted samples was significantly lower (Fig. 3a). Grafting with different rootstocks did not alter the basic volatile composition of the watermelon fruits, which primarily consisted of ketones, aldehydes, and alcohols. Notably, wild watermelon-grafted fruits exhibited higher alcohol contents (10.16−11.55) than both NG (8.19) and other grafted fruits (4.44−8.73) (Fig. 3b). Research has indicated that wild watermelon rootstocks enhance fruit quality by augmenting sugar, organic acid, and total phenolic content[52]. Furthermore, pumpkin-grafted fruits displayed increased aldehyde levels and decreased alcohol, aromatic hydrocarbon, and ketone levels when compared to NG and other grafted fruits (Fig. 3c−f). The volatile compounds 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one and (E,Z)-3,6-nonadienol were the most prevalent in NG, wild watermelon, and bottle gourd-grafted watermelons (Tables 3 & 6). In contrast, hexanal and (E,Z)-3,6-nonadienol were the first and second most abundant volatiles, respectively, in pumpkin-grafted samples.

Table 6. Differentially accumulated volatile compounds identified in watermelon grafted onto each rootstock type compared to NG.

Code Compound Class NG Wild watermelon Bottle gourd Pumpkin 3 2-methyl-1-butanol alcohol 0.14a 0.1a 0.12a 0.05b 43 propyl-cyclopentane aromatic hydrocarbon nd b tr b tr b 0.01a 48 2,4-dimethyl-1-heptene aromatic hydrocarbon tr b tr b tr b 0.01a 51 (E)-3-hexenol alcohol 0.01ab 0.01a tr bc tr c 55 (Z)-3-hexenol alcohol 0.22ab 0.21a 0.16b 0.05c 65 hexanol alcohol 1.12a 0.83ab 0.86ab 0.55b 70 styrene other 0.33a 0.46a 0.41a 0.02b 92 cumene aromatic hydrocarbon tr a 0.01a tr a nd b 117 2-methyl-1-hepten-6-one ketone 0.02a 0.01ab 0.01ab 0.01b 118 (Z)-3-heptenol alcohol 0.02a 0.01ab 0.01ab tr b 128 phenol phenol 0.08a 0.03ab nd b 0.01b 154 RI1008 ketone tr b tr b 0.01b 0.03a 161 (Z)-2-decene aromatic hydrocarbon 0.57bc 0.89a 0.76ab 0.5c 163 2-ethyl-1-hexanol alcohol 0.01a tr b nd b tr b 191 acetophenone ketone tr b tr a tr b tr b 192 6-methyl-3,5-heptadiene-2-one ketone tr bc tr a tr ab tr c 227 (Z)-6-nonenal aldehyde 0.24b 0.33b 0.43b 1.2a 254 (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal aldehyde 0.54b 0.86ab 0.61b 1.24a 256 (Z)-3-nonenol alcohol 0.29bc 0.47a 0.34b 0.18c 258 (E,Z)-3,6-nonadienol alcohol 3.77bc 5.74a 4.39b 2.67c 358 γ-nonalactone lactone 0.03b 0.07a 0.04b 0.02b The relative volatile content was quantified by normalizing the peak area of each compound to the peak area of the internal standard. The values represent the mean of three biological replicates per type. The notation 'tr' indicates a detected peak with a value below 0.0095, while 'nd' signifies not detected. Variations in letters within the same rows denote statistically significant differences as determined by Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference test (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of volatile compounds in 'Ningnongke huadai' watermelon grafted onto different rootstock types. (a) Number of differentially accumulated volatile compounds identified in watermelons grafted onto each rootstock type compared to the non-grafted watermelons (p < 0.05). Red bars represent volatile compounds that were more abundant, while blue bars indicate those that were less abundant in the grafted watermelons compared to the non-grafted. The boxplots show the relative contents of volatiles in each chemical class among watermelon samples including (b) alcohols, (c) aldehydes, (d) aromatic hydrocarbons, (e) ketones, and (f) total volatiles. Groups denoted by the same letter are not significantly different as determined by Tukey's honestly significant difference test at p < 0.05.

Grafting significantly influenced the concentrations of hexanal, (Z)-6-nonenal, and 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one[21], but here only the levels of (Z)-6-nonenal exhibited a notable difference, with a substantial increase in pumpkin-grafted samples compared to NG. Petropoulos et al.[22] observed that grafting onto the 'TZ148' rootstock (C. moschata × C. maxima hybrid) elevated the levels of seven volatile compounds, including (Z)-6-nonenal, nonanal, (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal, (Z,Z)-3,6-nonadienol, and (E)-2-nonenal in seeded watermelons, a change considered detrimental to the fruit's volatile profile. Additionally, select volatile compounds such as propyl-cyclopentane, 2,4-dimethyl-1-heptene, RI1008, and (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal were more concentrated in pumpkin-grafted samples, distinctly differentiating them from other watermelons (Tables 3 & 6). The study by Fredes et al.[20] found increased levels of (Z)-6-nonenal and (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal, which impart melon-like and cucumber-like aromas, in Cucurbita-grafted watermelons, a finding corroborated by our research. Notably, these grafted fruits exhibited elevated levels of (Z)-6-nonenol, associated with a pumpkin-like odor and considered adverse to fruit quality[20]. However, the pumpkin rootstocks in the present study did not significantly raise the levels of (Z)-6-nonenol. In contrast, acetophenone, (Z)-3-nonenol, (E,Z)-3,6-nonadienol, and γ-nonalactone were markedly more abundant in wild watermelon-grafted samples. Mendoza-Enano et al.[53] suggested that a higher concentration of acetophenone might lead to undesirable odors. In line with Gong et al.[40], who reported a positive correlation between TSS and (Z)-3-nonenol, the present study found that wild watermelon rootstocks significantly boosted both central soluble solids and (Z)-3-nonenol levels in grafted fruits (r = 0.84).

A Venn diagram was constructed to analyze the specific volatile compounds unique to NG and grafted watermelons. It revealed that wild watermelon, bottle gourd, and pumpkin grafts contributed three, one, and two exclusive volatile compounds, respectively (Fig. 2c). For instance, 3-octen-2-one was exclusively detected in wild watermelon and pumpkin grafted samples (Table 3). In contrast to the others, wild watermelon-grafted samples lacked (E)-2-nonenal, which may be attributed to their elevated levels of (Z)-3-nonenol; this compound is known to arise from the reduction and isomerization of (E)-2-nonenal[19]. Additionally, propyl-cyclopentane was present in all grafted variants but absent in NG samples. This compound is common in grafted plants and was also identified in Populus deltoides following methyl jasmonate treatment[54].

Pairwise comparisons were conducted to identify volatile compounds that differed significantly among the 12 samples (NG and 11 grafted), resulting in the detection of 36 differentially accumulated aroma volatiles in at least one comparison (Table 3). The impact of grafting on watermelon fruit aroma was assessed using PCA, which revealed that PC1 and PC2 accounted for 60.9% and 19% of the total variance, respectively (Fig. 2d). Specifically, PC1 effectively distinguished pumpkin-grafted watermelons based on their relative concentrations of alcohols and aromatic hydrocarbons, such as (Z)-3-nonenol, (Z)-3-hexenol, (E)-3-hexenol, (Z)-3-octenol, (Z,Z)-3,6-nonadienol, cumene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-benzene, propyl-cyclopentane, 2,4-dimethyl-1-heptene, and 2,4-dimethyl-heptane (Table 7). The volatile profiles of watermelon fruits grafted onto citron melon (C. lanatus var. citroides) showed similarity to those of NG and self-grafted samples[20]. Notably, the NG and the wild watermelon-, bottle gourd-grafted samples clustered closely along PC1, suggesting comparable volatile profiles.

Table 7. Volatile compounds with high contribution to the PC1 and PC2 in Fig. 1d.

Code Compound Class PC1 PC2 70 styrene other 0.94 92 cumene aromatic hydrocarbon 0.91 256 (Z)-3-nonenol alcohol 0.90 55 (Z)-3-hexenol alcohol 0.90 51 (E)-3-hexenol alcohol 0.89 316 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-

benzenearomatic hydrocarbon 0.87 183 (Z)-3-octenol alcohol 0.87 154 RI1008 ketone 0.86 139 RI980 other 0.81 258 (Z,Z)-3,6-nonadienol alcohol 0.81 43 propylcyclopentane aromatic hydrocarbon 0.80 80 (Z)-4-heptenal aldehyde 0.80 48 2,4-dimethyl-1-heptene aromatic hydrocarbon 0.78 38 2,4-dimethyl-heptane aromatic hydrocarbon 0.78 358 γ-nonalactone lactone 0.77 122 3,5,5-trimethyl-2-hexene aromatic hydrocarbon 0.66 20 (Z)-2-pentenol alcohol 0.61 13 (E)-2-pentenal aldehyde 0.60 149 (E,E)-2,4-heptadienal aldehyde 0.52 263 (Z)-6-nonenol alcohol 0.45 52 2-hexenal aldehyde 0.43 247 (E,E)-2,6-nonadienal aldehyde 0.43 138 (E,Z)-2,4-heptadienal aldehyde 0.42 HCA based on the relative concentrations of differentially accumulated volatiles categorized the 12 watermelon samples into two primary clusters (Fig. 2e). All pumpkin-grafted watermelons grouped in one cluster, while the remaining samples formed the second cluster. The volatile profiles of pumpkin-grafted watermelons differed markedly from the others, characterized by higher levels of aldehydes and lower levels of alcohols and aromatic hydrocarbons. C6 and C9 aldehydes and alcohols are mainly regulated by genes such as LOX and ADH in the lipoxygenase pathway[55]. Due to the possible remarkable deterioration of fruit shape and taste, the Cucurbita spp. was rarely used as a rootstock for melon[15]. The HCA results were consistent with previous PCA findings, which indicated that the bottle gourd- and wild watermelon-grafted samples showed no clear differentiation from NG samples, whereas pumpkin-grafted watermelons had unique volatile profiles, resulting in a distinct watermelon fruit aroma. Similarly, pumpkin rootstocks significantly reduced the odor intensity and odor preference scores of the grafted melons decreased the concentration or even caused the absence of main aroma components, and down-regulated ADH and AAT activity and the expression levels of CmADH and CmAAT homologs, while muskmelon rootstocks displayed no significant grafting effect[56].

Grafting effect of different rootstocks on fruit volatile profiles

-

To elucidate the influence of 11 different rootstocks on watermelon fruit aroma, a comparative analysis of volatile compound profiles were performed. The total volatile content ranged from 25.31 in JX2 to 37.82 in NZ101. Relative to NG samples, six grafted watermelons exhibited higher total volatile concentrations. Notably, 'Sizhuang 111' (SZ111, 15.05) and 'Mingxiu' (MX, 8.68) demonstrated the highest and lowest concentrations of 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one, respectively. The abundance of aldehydes varied significantly, with QY1 registering the highest (12.9) and 'Jingxinzhen 1' (JX1, 5.23) the lowest levels, predominantly due to differences in hexanal, (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal, nonanal, and (Z)-6-nonenal accumulation. NZ101 contained the most alcohols (11.55), particularly (E,Z)-3,6-nonadienol and nonanol, while the least was found in NZ1 (4.44). Together, alcohols and aldehydes comprised over half of the 36 distinct volatiles identified among the 12 watermelon samples. Specifically, C6 and C9 alcohols and aldehydes, such as (E,Z)-3,6-nonadienol, nonanol, hexanal, and nonanal, are recognized as characteristic watermelon aroma compounds[4,43,57]. Grafting notably affected the relative concentrations of several C6 and C9 alcohols and aldehydes, including (E)-3-hexenol, (Z)-3-hexenol, (E,Z)-3,6-nonadienol, (Z)-3-nonenol, (Z)-6-nonenol, nonanol, (E)-2-nonenal, (E,E)-2,6-nonadienal, nonanal, (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal, 2-hexenal, and (Z)-6-nonenal (Table 3). According to prior research, (E,Z)-2,6-nonadienal, (E)-2-nonenal (fatty, green and waxy odors), and (Z)-3-nonenol (fresh, waxy and green odors) dominate the aroma profile of watermelon flesh[20]. Volatile compounds such as (E)-2-nonenal, (Z)-6-nonenal, and (Z)-6-nonenol correlated positively with watermelon fruit preference[53] and were found in higher levels in pumpkin rootstocks ZS and MX.

PCA more effectively assessed the relationships among various watermelon samples (Fig. 2d). The close clustering of JX1 and YS with NG indicated that grafting watermelons onto them did not significantly alter their fruit volatile profiles. Distinctly, QY1 and ZS were separated from other pumpkin-grafted samples on PC2, primarily due to their elevated levels of volatile compounds such as 3,5,5-trimethyl-2-hexene, (E)-2-pentenal, (E,E)-2,4-heptadienal, 2-hexenal, and (E,Z)-2,4-heptadienal. The compounds acetophenone, dimethyl trisulfide, and (E,E)-2,4-heptadienal have been identified as key contributors to off-odor, substantially impacting the overall flavor preference of stored watermelon samples[53]. HCA grouped NG and bottle gourd-, wild watermelon-grafted samples together, reflecting their similar volatile profiles (Fig. 2e). The effects of different rootstocks on the volatile components and overall flavor quality of grafted watermelons are complex due to varietal and environmental differences. Investigating the underlying mechanisms for the alterations of volatile compounds in grafted watermelons is essential for future research. For example, studies on small RNAs or mobile proteins within the phloem will help reveal the interaction mechanisms between rootstock and scion and explore the influence of grafting on flavor quality in watermelon.

-

In summary, this study provides a comprehensive analysis of the volatile composition and their abundance in watermelon fruits, alongside fruit quality attribute assessments, to elucidate the impact of different rootstocks on grafted watermelons. The findings indicate that the choice of rootstock significantly influences the flavor quality of grafted fruit. Notably, wild watermelon rootstocks increased central soluble solids compared to NG, whereas pumpkin rootstocks enhanced fruit weight and flesh firmness but reduced central soluble solids. Watermelons grafted onto wild rootstocks YS and NZ101 exhibited higher central and edge soluble solids than NG. Using HS-SPME-GC-MS, the study identified 122 volatile compounds, with ketones as the predominant chemical group, followed by alcohols and aldehydes. Remarkably, 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one was the most abundant volatile, along with (E,Z)-3,6-nonadienol and hexanal. The influence of grafting on volatile profiles varied among rootstocks. Wild watermelon grafts had the highest levels of total volatile compounds, while pumpkin grafts had the least. Bottle gourd and wild watermelon grafts exhibited volatile compositions closely resembling those of NG. Grafting watermelons onto JX1, YS, YZ1, SZ111, and NZ101 did not significantly alter their fruit volatile profiles. In contrast, pumpkin grafts were particularly rich in aldehydes but deficient in alcohols and aromatic hydrocarbons, indicating significant differences in fruit volatile profiles. Watermelons grafted onto QY1 and ZS exhibited a highly distinct volatile composition from NG, primarily due to their elevated aldehydes. The wild watermelon rootstocks increased soluble solids and demonstrated a minimal impact on fruit volatile profiles. Consequently, wild watermelon rootstocks, such as YS and NZ101, with robust growth potential and strong disease resistance, were recommended to effectively mitigate the negative grafting effects on flavor quality in 'Ningnongke huadai' watermelon production. This research lays the groundwork for understanding how different rootstocks affect watermelon fruit quality and underscores the importance of considering fruit aroma in watermelon rootstock breeding programs. Future research should explore the molecular mechanisms driving aroma formation in various watermelon grafting combinations.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study design and coordinating: Yu Y, Zhang Y, Li H; sample collecting and experiment performing: Yang W, Zhou J, Yu R; data analysis: Du H, Tian M, Guo S; writing manuscript with input from all authors: Yu Y, Zhang Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

This study was financially supported by the Independent innovation fund of agricultural science and technology in Ningxia Hui autonomous region (Grant No. NGSB-2021-7-03).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Wanbang Yang, Jinyu Zhou

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yang W, Zhou J, Yu R, Du H, Tian M, et al. 2024. Assessment of fruit quality and volatile profiles in watermelons grafted onto various rootstocks. Vegetable Research 4: e036 doi: 10.48130/vegres-0024-0034

Assessment of fruit quality and volatile profiles in watermelons grafted onto various rootstocks

- Received: 30 April 2024

- Revised: 18 August 2024

- Accepted: 26 August 2024

- Published online: 02 December 2024

Abstract: Grafting is a common technique used to enhance watermelon yield under biotic and abiotic stress conditions; however, it may influence fruit development and quality. This study evaluated the impact of grafting on the fruit quality attributes and volatile profiles of 'Ningnongke huadai' watermelon using 11 commercial rootstocks, encompassing wild watermelons, bottle gourds, and pumpkins. Significant variations were observed in fruit weight, length, rind thickness, firmness of rind and flesh, and central soluble solids content. Notably, wild watermelon grafting increased central soluble solids, while pumpkin-grafted fruits exhibited higher fruit weight but lower central soluble solids. The analysis identified 122 volatile compounds in watermelon samples, primarily ketones, aldehydes, and alcohols. Regarding volatile composition, bottle gourd and wild watermelon grafts did not significantly differ from non-grafted watermelons, whereas pumpkin-grafted fruits showed distinctive volatile profiles characterized by higher aldehyde content and lower levels of alcohols and aromatic hydrocarbons. In conclusion, wild watermelon rootstocks increased soluble solids and had minimal impact on the volatile profiles of grafted fruits, making them potentially suitable for commercial production of 'Ningnongke huadai' watermelon. The evident variability in volatile profiles among grafting combinations underscores the need for watermelon rootstock breeding programs to account for the influence of rootstocks on fruit aroma.

-

Key words:

- Watermelon /

- Rootstock /

- Grafting /

- Fruit quality /

- Aroma /

- Volatile