-

Temperature is a key environmental factor determining crop yield and quality. However, excess temperature, such as heat stress, influences the growth and development of plant[1], which refers to the change in cellular membrane lipid composition, protein denaturation, electrolyte leakage, reactive oxygen species (ROS) as well as the decline of photosynthesis[2]. More importantly, photosynthesis is very sensitive to temperature and 90% of the plant yield comes from photosynthesis[3], and during photosynthesis, any part, such as Photosystem I (PSI), Photosystem II (PSII), photosynthetic electron transport as well as photosynthetic carbon fixation, is damaged by abiotic stresses and will inhibit the whole photosynthetic metabolism process[4]. Thus, the study of photosynthesis under abiotic stresses is meaningful for the promotion of yield. Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) is one of the main vegetables in the protected cultivation, which is a typical chilling-sensitive plant, but is not resistant to heat temperature. Heat stress, occurring in summer and autumn crops, becomes the typically limiting factors for cucumber yield and quality[5,6]. Our previous studies have shown that heat stress caused the cell membrane injury, ROS accumulation as well as the significant PSII photoinhibition and decrease of photosynthetic enzymes activities in cucumber plants, which further led to an obvious decline in cucumber yield[7−9]. Thus, reducing the heat damage to cucumber plants during the production is an important pathway to improve cucumber growth and yield. A number of studies have proven that the application of plant growth regulators, including abscisic acid (ABA), jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), auxin (IAA), etc, both were effective method to promote the abiotic stress resistance[10−12].

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine, MT) is a small molecule indole that was first discovered in the bovine pineal gland[13]. In 1995, Dubbels et al. found the existence of MT in higher plants[14]. Subsequently, a number of studies demonstrated exogenous or endogenous MT both participated in the regulation of plant growth and abiotic stress response[15,16]. As is well known, tryptophan decarboxylase (TDC), tryptophan 5-hydroxylase (T5H), serotonin N-acetyltransferase (SNAT), N-acetyl-5-serotonin-methyltransferase (ASMT), or caffeic acid-O-methyltransferase (COMT) are involved in MT synthesis[17,18], which have been cloned from numerous plant species, and the overexpression of these genes can promote MT content in plants, consequently enhancing the tolerance to abiotic stresses, which is mediated by MT[19−21]. To date, it has been demonstrated that heat stress can induce the accumulation of endogenous MT[22], and Shi et al.[23] found that the application of MT could increase the thermotolerance of Arabidopsis through inducing the expression of class A1 heat-shock factors (HSFA1s). In parallel to this, our previous studies also investigated that high temperature stress could induce the synthesis of endogenous MT via stimulating the relative expression of TDC and ASMT and the application of MT significantly alleviated the oxidative damage through increasing the antioxidant ability and abundance of heat shock transcription factors HSF7, HSP70.1, and HSP70.11 to further increase the cucumber heat stress tolerance[9]. Moreover, Jahan et al.[24] found that the application of melatonin could increase the heat tolerance of tomato plants via increasing the photosynthetic pigment content and alleviated the decline of photosynthetic capacity, such as the decline of Rubisco and RCA activities as well as the PSI and PSII photoinhibition caused by heat stress. However, the underlying molecular mechanism of melatonin-mediated photosynthesis in cucumber exposed to heat stress largely remain elucidated. Thus, CsASMT overexpression and inhibition transgenic cucumber plants were used to show the role of MT on photosynthesis of cucumber under heat stress and the results will provide a theoretical framework for improving cucumber heat tolerance via exogenous MT application.

-

'Jinyou 35' cucumber, 'Xintaimici' cucumber (wild type), CsASMT transgenic cucumber (OE-CsASMT and Anti-CsASMT, obtained in our previous studies) were used in this experiment.

To generate the cucumber PGR5 suppression lines, the PGR5 (GenBank accession No. XM-004147117) coding sequence was amplified from cucumber complementary DNA (cDNA) with specific primers: F: TCAAGCAAGAAATCCTAATTTTTCC; R: AAAGCCGGTAAGATTCCGGC. The purified PCR product was digested with Xbal and Smal and then cloned into PBI121. Then the positive plasmids were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404 by the heat shock method. Finally, cotyledon disk transformation using 'Xintaimici' cucumber plants was performed and the transgenic plants were verified by PCR and sequencing.

Growth and treatments

-

Cucumber seeds were sown in plastic pots filled with base material in a solar greenhouse with sunlight during the day (maximum of 800~1,000 μmol·m−2·s−1 PFD) and 25~31 °C/13~21 °C day/night temperature under a 13 h photoperiod.

At the two-leaf stage, the 'Jinyou 35' cucumber seedlings were sprayed with 0 μmol·L−1 (H2O), 25 μmol·L−1, 50 μmol·L−1, 75 μmol·L−1, 100 μmol·L−1, and 125 μmol·L−1 melatonin (MT) for 2 d. Afterward, half of these seedlings were transferred to a heat temperature simulated growth chamber (day/night temperature 42 °C/35 °C, 600 μmol·m-2·s−1 PDF), and the other half seedlings were placed at 25/18 °C as the control. Meanwhile, the WT, OE-CsASMT, and Anti-CsASMT cucumber seedlings with two leaves were also subjected to the same heat conditions. WT and Anti-CsPGR5 seedlings were sprayed with H2O and 100 μmol·L−1 MT, respectively, for 2 d. Then half of WT and Anti-CsPGR5 seedlings were treated with heat stress (similar to the above) and the other half were placed at 25/18 °C as the control. The transgenic cucumber plants used in this paper were all homozygous T2 plants. The samples were obtained or photosynthetic parameters were measured at 0 d, 1 d, 3 d, and 5 d after heat stress.

Determination of growth, heat damage index, and electrolyte leakage rate

-

The plants were sampled at 0 d, 1 d, 3 d, and 5 d after heat stress and firstly blanched for 30 min at 95 °C, then dried at 110 °C to a constant weight to calculate the dry matter weight. Leaf area was measured according to the method of Gong & Xiang[25].

The methods used to measure electrolyte leakage rate (EL) and the heat damage index have been described previously[6,26].

Determination of gas exchange parameters

-

The Ciras-3 portable photosynthesis measurement system (PP-Systems, USA) was used to determine the Pn, Gs, Tr, and intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci). All measurements were recorded at 600 μmol·m-2·s−1 PDF, 390 μL·L−1 CO2 concentration and (25 ± 1) °C leaf temperature. According to the method of von Caemmerer & Farquhar[27] to determine the light-saturated CO2 assimilation rate (Asat), firstly, different light-intensity gradients were set up to determine the photosynthetic rate of cucumber leaves under each light intensity. Generally, the photosynthetic rate of cucumber leaves reached a stable value after 1 min. With the increase in light intensity, the photosynthetic rate showed an upward curve. When the light intensity reached 1,200 μmol·m−2·s−1, it reached stability, and the corresponding photosynthetic rate was Asat.

Determination of chlorophyll fluorescence

-

The FMS-2 modulated chlorophyll fluorometer (Hansatech, England) was used to measure the chlorophyll fluorescence parameters. The determination of fluorescence under light: Firstly, the plants were treated with light adaptation for more than half an hour (600 μmol·m−2·s−1), and the adapted leaves were irradiated with light for 30 s (consistent with the intensity of the treated light), and the steady-state fluorescence value Fs was recorded. Then, turn on the high-intensity saturated pulsed light (10,000 μmol·m−2·s−1), and the illumination time was 0.7 s, then the maximum fluorescence value Fm' under light adaptation was determined. Then turn off the action light and turn on the far-red light, the illumination time was 3 s, and the minimum fluorescence value Fo' under light adaptation was determined. Fluorescence measurement under dark adaptation: The leaves were darkened for more than half an hour, and the initial fluorescence value Fo was measured with extremely weak measurement light, and then the high-intensity saturated pulse light (10,000 μmol·m−2·s−1) was turned on, the illumination time was 0.7 s, and the maximum fluorescence value Fm under dark adaptation was measured. Fv/Fm, ΦPSII, qP, NPQ, and ETR were calculated according to Demming-Adams[28].

Chlorophyll fluorescence imaging of the cucumber seedlings placed in the dark for 30 min was visualized using FluorCam chlorophyll fluorescence imaging system (Photon Systems Instruments, Czech Republic) according to the method of Baker[29].

Determination of chlorophyll a fluorescence transient and 820-nm transmission

-

Chlorophyll a fluorescence transient and 820-nm transmission were measured using an integral multifunctional plant efficiency analyzer (M-PEA, Hansatech, King's Lynn, Norfolk, UK). After illuminating with a saturating red light pulse of 3,000 μmol·m−2·s−1, the instrument automatically recorded the fluorescence signal from 10 μs to 1 s, and then ΔVt, Wk, φE0, and PIABS were calculated according to the JIP-test method[30−31]. To measure the relative content of the active PSI reaction center, the amplitude of the 820-nm reflection (ΔI/I0) during far-red illumination was determined using a previously reported method[32].

Determination of CEF rate

-

The Dual-PAM-100 (Walz Effeltrich, Germany) was used to measure rapid light curves of leaves after dark adaptation from different treatments in a dual channel mode monitoring both P700 and chlorophyll fluorescence signal. During the measurement, seven light intensities 46, 100, 225, 463, 868, 1,065, and 1,317 μmol·m−2·s−1 were set and each light intensity lasted for 2 min, the related parameters were calculated according to previous studies[33−35]. Electron transfer rate of PSI ETR(I) = Y(I) × PFD × Abs × (1 − dII); Electron transfer rate of PSII ETR(II) = Y(II) × PFD × Abs × dII, where Y(I) and Y(II) are quantum yields of PSI and PSII under different light conditions, respectively; dII = Y(I)/(Y(I) + Y(II)), where Y(I) and Y(II) are quantum yields of PSI and PSII under low light conditions; CEF rate = ETR(I) – ETR(II) (Abs, fraction of photons absorbed by leaf; dII, fraction of the absorbed photos distributed to PSII).

Determination of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) and Rubisco activase (RCA) activities

-

0.1 g fresh leaves were ground in an ice bath and then analyzed according to the instructions of Rubisco Kit (RUBPS-1-Y, KeMing, Suzhou, China) and RCA ELISA kit (MM-0602O1, KeTe, Jiangsu, China).

Determination of gene and protein level

-

An RNA Trizol kit (ET-101-01, TransGen, Beijing, China) was used for total RNA extraction from cucumber leaf tissue, and the first strand cDNA for real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was obtained according to the instructions of a Kit (R323-01, Vazyme, Nanjing, China). RT-qPCR was performed with a TransStart® TipTop Green qPCR Super Mix (Q711-02, Cwbio, Beijing, China) using a LightCycler® 480 II system (Roche, Penzberg, Germany). The primers of CsASMT, CsPGR5, RCA, rbcL and rbcS are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The conditions included predenaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by cycles of denaturing at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. The cucumber β-actin gene (XM_011659465) was used as an internal reference gene.

The relative protein level was detected by western blot with goat anti-rabbit antibody (Cwbio, Beijing, China), described in our previous studies[36].

Statistical analysis

-

The data are presented as the mean ± the standard deviation (SD) in at least three biological replicates with 5~10 plants for each measurement. All presented data were statistically analyzed with DPS software (p < 0.05).

-

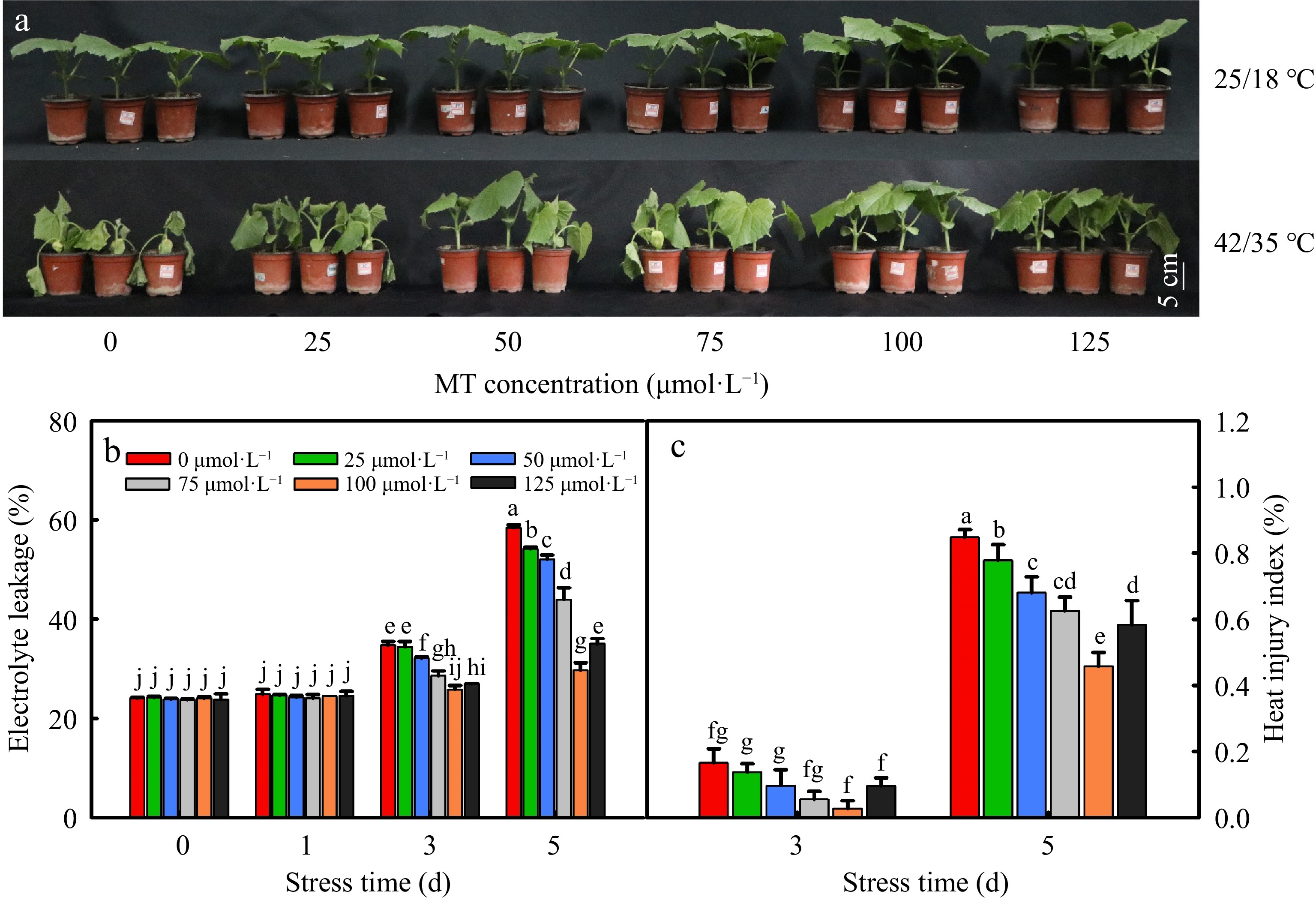

As shown in Fig. 1a, exogenous melatonin had little effect on the cucumber seedlings under control conditions at 25/18 °C and cucumber leaves of all treatments wilted and turned yellow after 5 d at 42/35 °C. However, the tolerance of cucumber seedlings for heat stress was improved by exogenous melatonin pretreatment. Indeed, heat-induced damage to seedlings, as manifested by electrolyte leakage rate (EL) and heat injury index, was notably alleviated by the MT pre-treatment (Fig. 1b, c), especially at a concentration of 100 μmol·L−1.

Figure 1.

The effect of different concentrations of melatonin on heat tolerance of cucumber seedings. (a) The phenotype of cucumber seedlings after 5 d of high temperature stress; (b) Electrolyte leakage rate; (c) Heat injury index. The two-leaf-stage cucumber seedlings were treated at 42/35 °C for 5 d, the samples were taken at 0, 1, 3, and 5 d after high temperature treatment. All values shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3). Lowercase letters a–j indicate that mean values are significantly different among samples (p < 0.05).

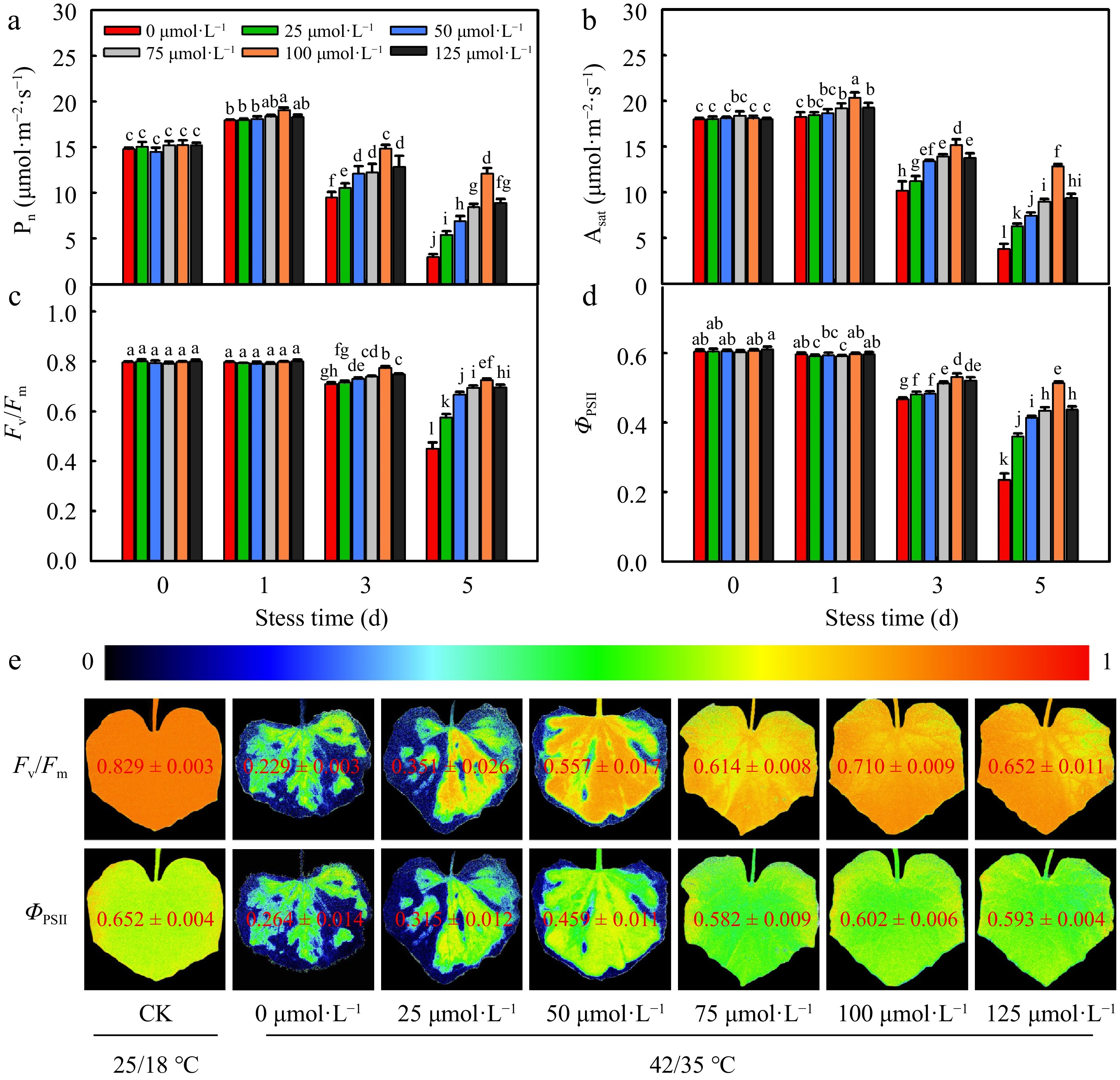

Subsequently, we studied the effects of MT on photosynthesis under high temperature stress. The net photosynthetic rate (Pn), light-saturated photosynthetic rate (Asat), as well as the actual photochemical efficiency of PSII (ΦPSII) and maximum photochemical efficiency of PSII in darkness (Fv/Fm) gradually decreased after 3 d heat temperature stress, but a significant increase in Pn, Asat, ΦPSII, and Fv/Fm were observed after exogenous melatonin application (Fig. 2). Similarly, cucumber seedlings showed the highest photosynthesis parameters pre-treated with 100 μmol·L−1. These data implied that exogenous melatonin at 100 μmol·L−1 alleviated the leaf damage and photosynthesis decline caused by heat stress, contributing to heat tolerance in cucumber seedlings.

Figure 2.

The effect of different concentrations of melatonin on photosynthesis of cucumber seedings under high temperature stress. (a) Pn; (b)Asat; (c) Fv/Fm; (d) ΦPSII; (e) Images of Fv/Fm and ΦPSII. The two-leaf-stage cucumber seedlings were treated at 42/35 °C for 5 d. All values shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3). Lowercase letters a–l indicate that mean values are significantly different among treatments (p < 0.05).

Effects of CsASMT overexpression and inhibition on heat stress tolerance of cucumber under heat stress

-

To further explore the mechanism of MT on heat stress tolerance of cucumber seedlings, two independent transgenic lines (obtained in our previous study) that overexpressed and suppressed the MT biosynthesis gene CsASMT encoding N-acetyl-5-serotonin-methyltransferase (ASMT) were used as the experimental materials. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S1, the relative expression of CsASMT and endogenous MT content was higher in OE-CsASMT plants and lower in Anti-CsASMT plants, compared with the wild type (WT).

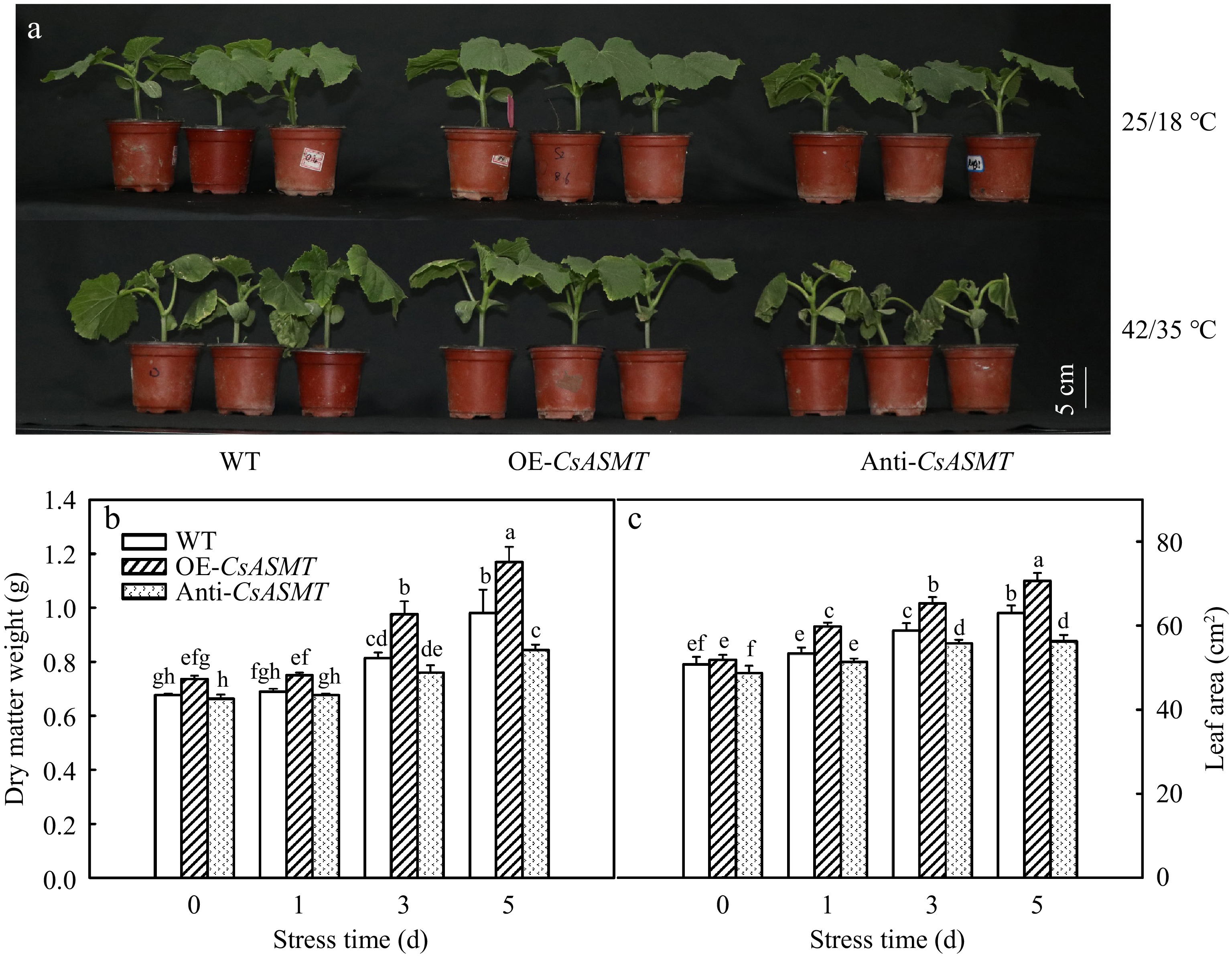

First, the effect of CsASMT overexpression and inhibition on heat stress tolerance of cucumber plants was studied. As shown in Fig. 3a, CsASMT overexpression promoted the growth of cucumber seedlings and CsASMT inhibition decreased the growth of cucumber seedlings compared to WT under high temperature stress. After 5 d heat stress significantly injured cucumber leaves, but the overexpression of CsASMT notably alleviated the leaf damage, while, inhibition of CsASMT aggravated the leaf damage caused by heat stress compared to WT. For instance, the dry matter weight of WT, OE-CsASMT and Anti-CsASMT plants increased by 44.1%, 58.1%, and 27.3%, respectively, after 5 d heat stress. The variation of leaf area was in accordance with the dry matter weight.

Figure 3.

The effect of CsASMT overexpression and inhibition on the growth of cucumber seedlings under high temperature stress. (a) The phenotype of cucumber seedlings after 5 d of high temperature stress; (b) Dry matter weight; (c) Leaf area. The two-leaf-stage cucumber seedlings were treated at 42/35 °C for 5 d, the samples were taken at 0, 1, 3, and 5 d after high temperature treatment. All values shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3). Lowercase letters a–h indicate that mean values are significantly different among treatments (p < 0.05).

Effects of CsASMT overexpression and inhibition on gas exchange parameter of cucumber under heat stress

-

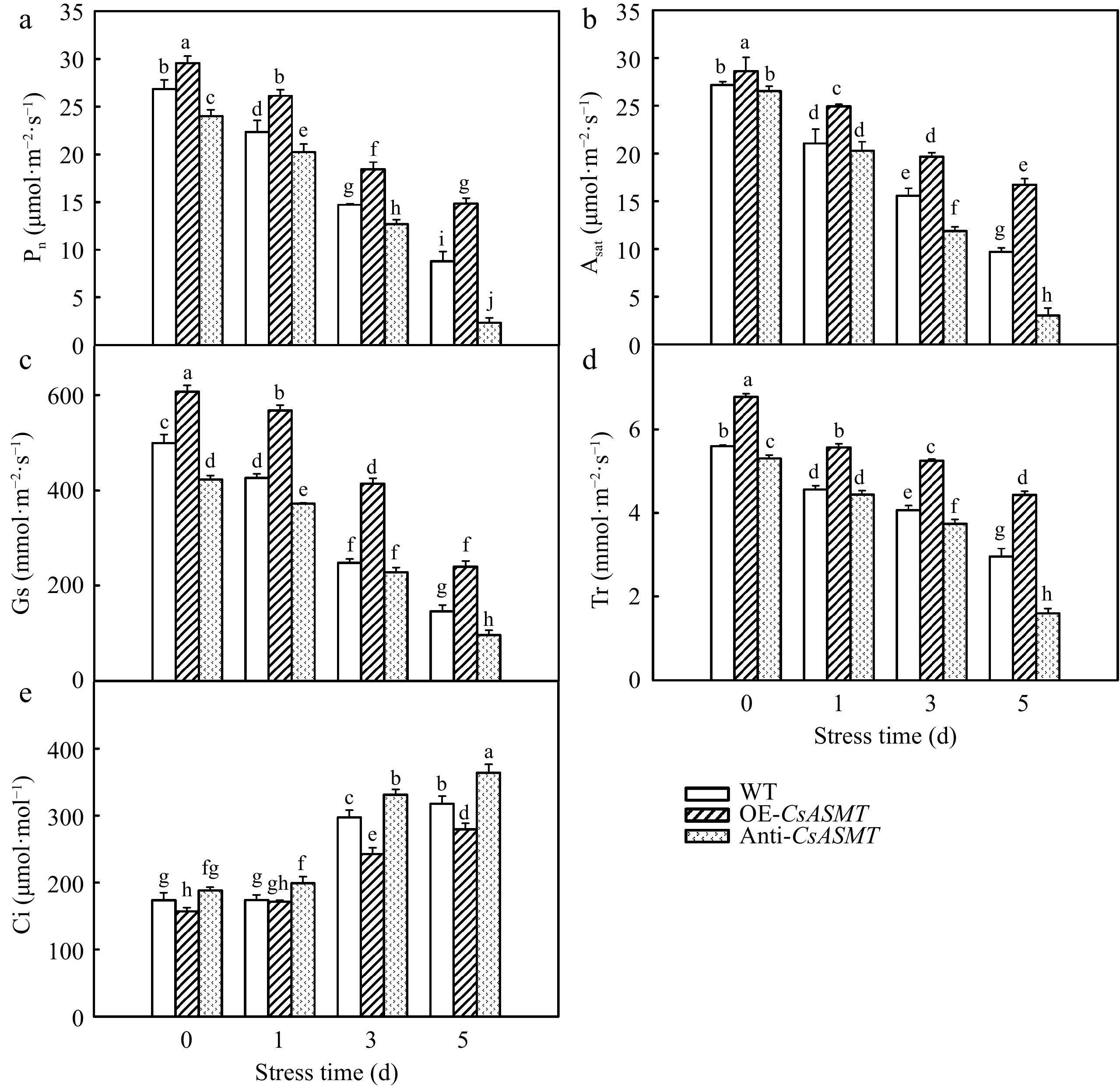

Photosynthesis is the most sensitive physiological process to extreme temperature. To further explore the mechanism of MT on photosynthesis of cucumber seedlings under high temperature stress, the effect of CsASMT overexpression and inhibition on the change of gas exchange parameters under heat stress was studied.

Notably, there was a difference of photosynthesis in WT and CsASMT transgenic cucumber seedlings before high temperature stress, in terms of higher Pn, Asat, Gs, Tr in OE-CsASMT and lower in Anti-CsASMT plants than that in WT (Fig. 4). The Pn, Asat, Gs, and Tr gradually decreased and Ci increased with the extension of high-temperature treatment, implying non-stomatal limitation was the main reason for photosynthesis decline under heat stress. More importantly, we found the overexpression of CsASMT notably alleviated the decline of photosynthesis, while, inhibition of CsASMT aggravated the decline of photosynthesis caused by heat stress compared to the WT. For instance, the Pn of WT, OE-CsASMT, and Anti-CsASMT plants decreased by 67.2%, 49.7%, and 90.2%, respectively, after 5 d heat stress.

Figure 4.

The effect of CsASMT overexpression and inhibition on photosynthesis of cucumber seedlings under high temperature stress. (a) Pn; (b) Asat; (c) Gs; (d) Tr; (e) Ci. The two-leaf-stage cucumber seedlings were treated at 42/35 °C for 5 d. All values shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3). Lowercase letters a–j indicate that mean values are significantly different among treatments (p < 0.05).

Effects of CsASMT overexpression and inhibition on Rubisco and RCA activities of cucumber under heat stress

-

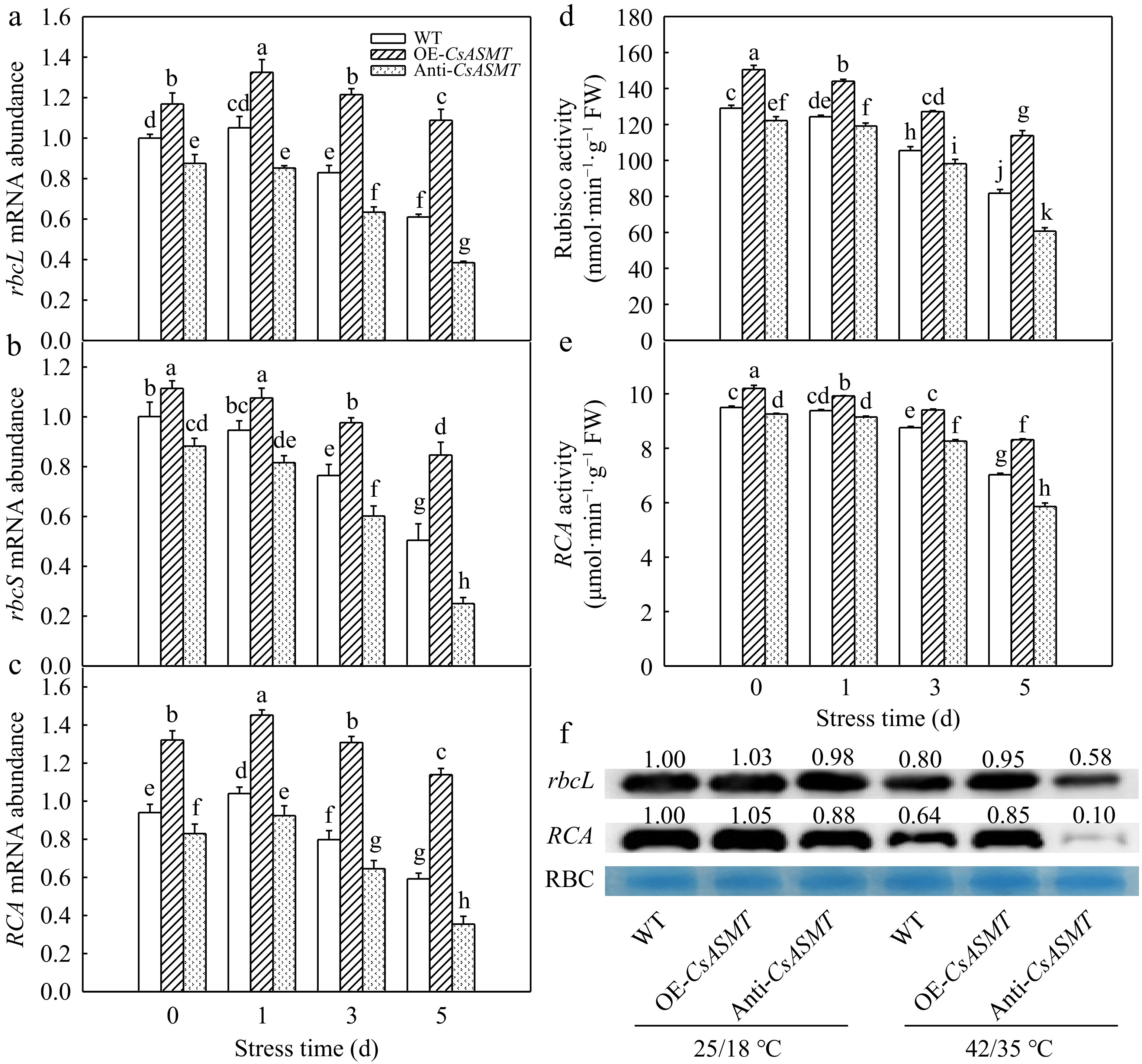

Under normal conditions, CsASMT overexpression significantly increased the Rubisco and RCA activities, which were decreased in Anti-CsASMT plants compared with WT (Fig. 5d, e). Notably, Rubisco and RCA activities declined with prolonged exposure to high temperature, but the overexpression of CsASMT most obviously increased the activities of Rubisco and RCA. The activities of Rubisco and RCA in WT, OE-CsASMT and Anti-CsASMT decreased by 36.7%, 24.3%, 50.3%, and 26.0%, 18.4%, 36.7%, respectively, after 5 d heat stress. Consistent with Rubisco and RCA activities, the overexpression of CsASMT most obviously alleviated the decline of the mRNA expression and protein level of rbcL, rbcS, and RCA in cucumber seedlings caused by heat stress (Fig. 5a−c, f).

Figure 5.

The effect of CsASMT overexpression and inhibition on the activity and expression of photosynthetic enzymes in cucumber seedlings under high temperature stress. (a)–(c) rbcL, rbcS, and RCA mRNA abundance. (d), (e) Activities of Rubisco and RCA. (f) The protein level of rbcL and RCA. The two-leaf-stage cucumber seedlings were treated at 42/35 °C for 5 d, the samples were taken at 0, 1, 3, and 5 d after high temperature treatment. All values shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3). Lowercase letters a–k indicate that mean values are significantly different among samples (p < 0.05).

Effects of CsASMT overexpression and inhibition on PSII and PSI photoinhibition of cucumber under heat stress

-

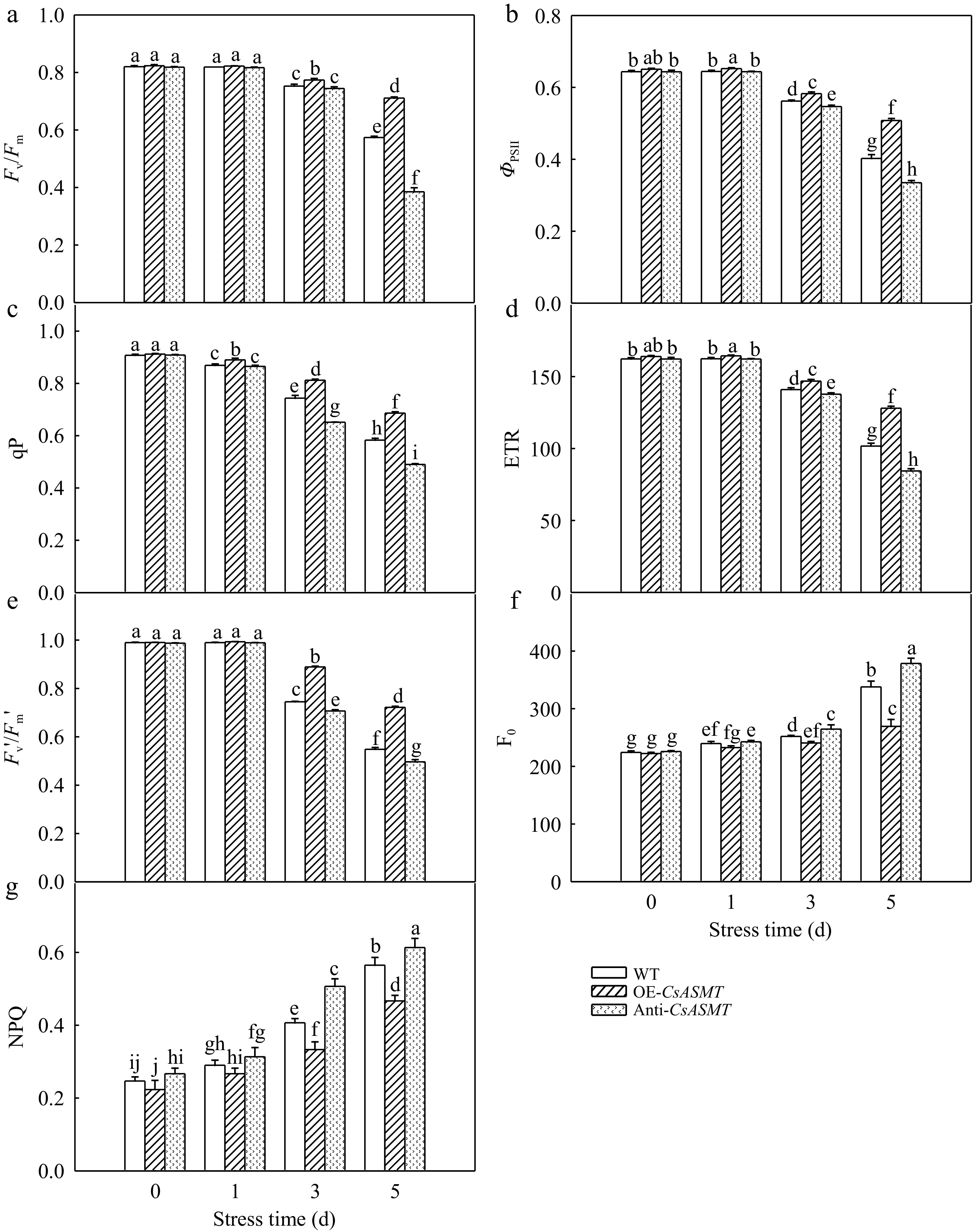

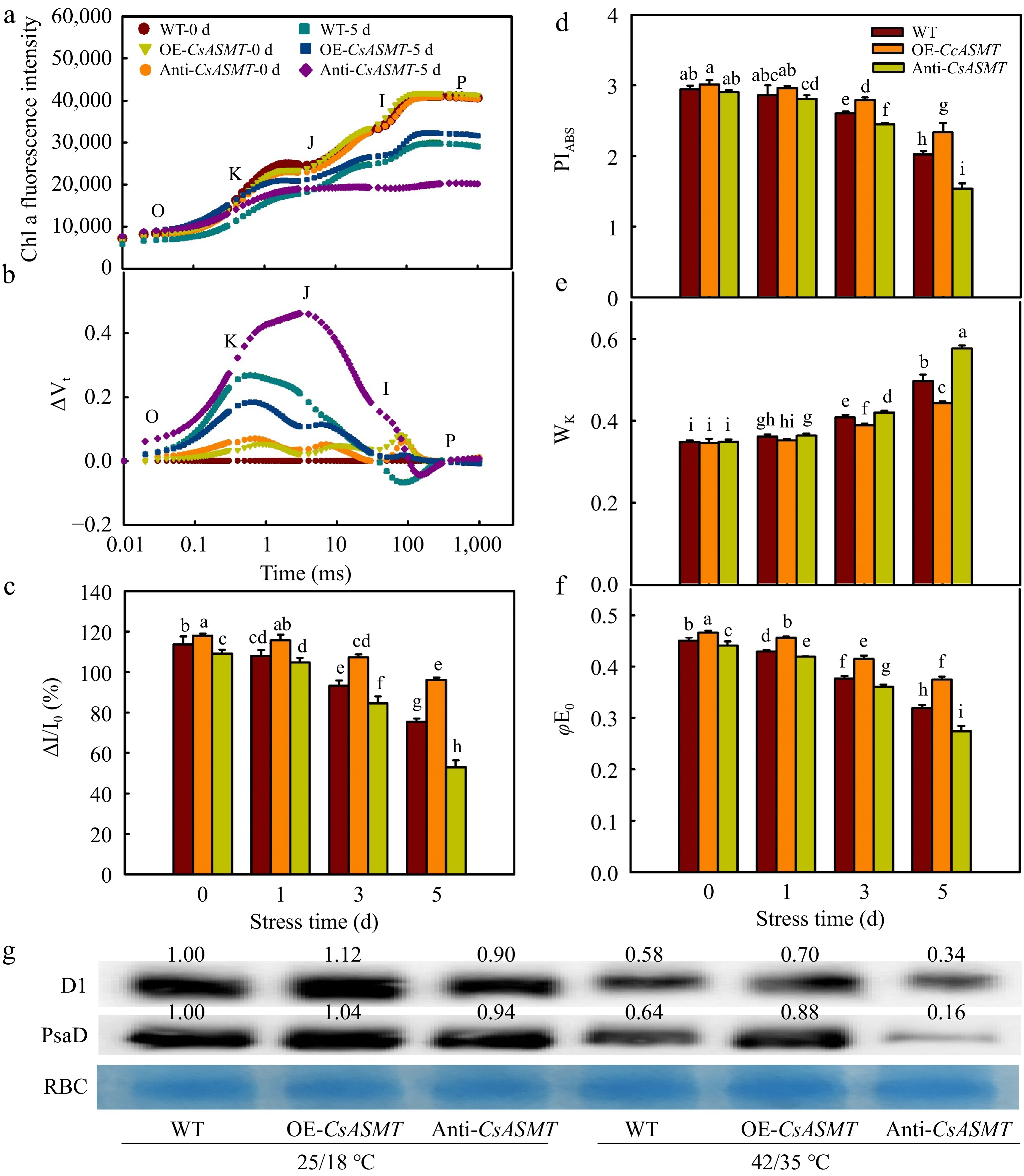

To further study the role of MT on the photosynthesis of cucumber, the change of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters under high-temperature stress were analyzed. Exposure to 42/35 °C for 1 d resulted in no change of Fv/Fm and ΦPSII in all treatments and notably, 5 d resulted in an obvious decrease in Fv/Fm and ΦPSII (Fig. 6a, b). Compared to the WT, the Anti-CsASMT plants showed a 52.9% and 48.0% decrease in Fv/Fm and ΦPSII, whereas overexpression of CsASMT increased Fv/Fm and ΦPSII. Also, heat stress led to a decrease of qP, ETR, Fv'/Fm' and an increase in F0 and NPQ (Fig. 6c−g). Similarly, qP, ETR, Fv'/Fm' were promoted by the overexpression of CsASMT, but inhibited in Anti-CsASMT plants exposed to heat stress for 5 d.

Figure 6.

The effect of CsASMT overexpression and inhibition on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of cucumber seedlings under high temperature stress. (a) Fv/Fm; (b) ΦPSII; (c) qP; (d) ETR; (e) Fv'/Fm'; (f) F0; (g) NPQ. The two-leaf-stage cucumber seedlings were treated at 42/35 °C for 5 d. All values shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3). Lowercase letters a–j indicate that mean values are significantly different among treatments (p < 0.05).

To further confirm the effect of CsASMT overexpression and inhibition on PSII under high-temperature stress, an O-J-I-P curve of cucumber seedlings was observed. The data showed that the morphology of the O-J-I-P curve of cucumber leaves changed significantly in terms of a decrease in the I and P points after 5 d of high-temperature stress. Then, we standardized the O-J phase and found that Wk increased notably, the Wk of WT, OE-CsASMT, and Anti-CsASMT plants increased by 42.7%, 27.8%, and 65.2% respectively at 5 d after heat stress, implying that CsASMT overexpression decreased the damage to OEC induced by high-temperature stress (Fig. 7a–c, e). High temperature stress also caused a decline in ΔI/I0, φE0, and PIABS. Meanwhile, the protein levels of D1 and PsaD were significantly decreased under heat stress, and the overexpression of CsASMT delayed the decrease of these protein levels.

Figure 7.

The effect of CsASMT overexpression and inhibition on the activities of PSII and PSI in cucumber seedlings under high temperature stress. (a) Chl a fluorescence intensity; (b) ΔVt; (c) ΔI/I0; (d) PIABS; (e) Wk; (f) φEo; (g) The protein level of D1 and PsaD. The two-leaf-stage cucumber seedlings were treated at 42/35 °C for 5 d, the samples for protein level analysis were taken at 0, 1, 3, and 5 d after high temperature treatment. All values shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3). Lowercase letters a–i indicate that mean values are significantly different among samples (p < 0.05).

Effects of MT on CEF in cucumber under heat stress

-

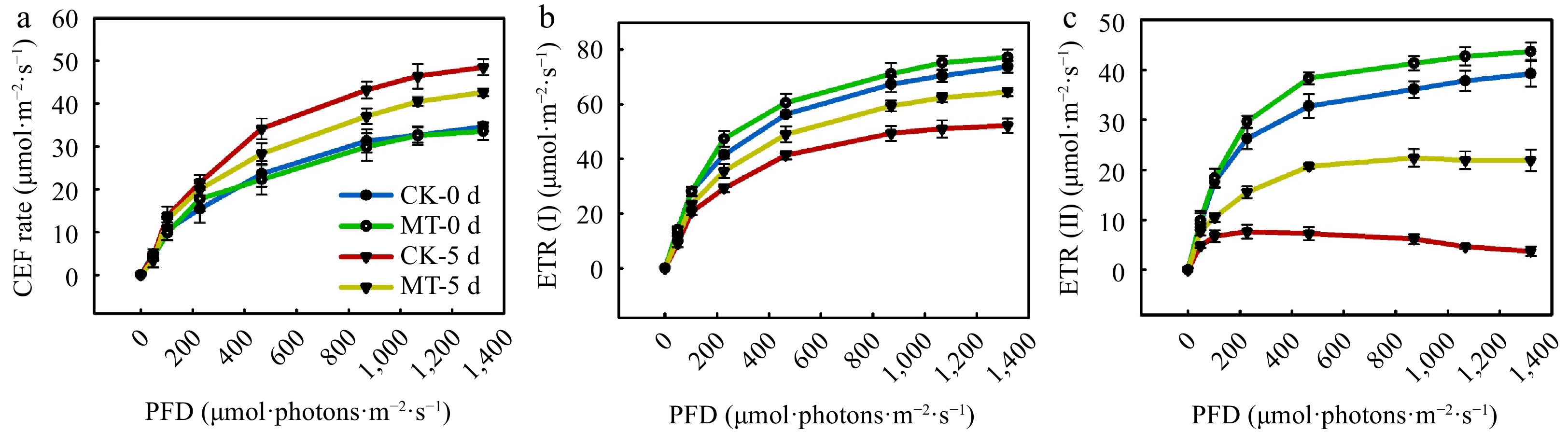

Cyclic electron flow (CEF), calculated with the difference value between ETR(I) and ETR(II), is one important pathway to protect photosynthesis under abiotic stress, As shown in Fig. 8, the CEF, ETR(I), and ETR(II) gradually increased with advancing PFD and no significant differences of CEF, ETR(I), and ETR(II) were observed between MT and the control treatment under normal condition. Moreover, we found exposure to 42 °C for 5 d caused the obvious increase of CEF and decrease of ETR(I) and ETR(II). Notably, the CEF of seedlings pretreated with MT and sprayed with water increased by 22.1% and 37.6%, and ETR(II) decreased by 56.7% and 83.6%, respectively, at 5 d after heat stress, but there was no difference of ETR(I) in MT and control treatments.

Figure 8.

The effect of MT on CEF in cucumber seedlings under high temperature stress. (a) CEF rate; (b) ETR (I); (c) ETR (II). The two-leaf-stage cucumber seedlings were treated at 42/35 °C after 5 d. All values shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3).

Effects of MT on photosynthesis of Anti-CsPGR5 cucumber seedlings under heat stress

-

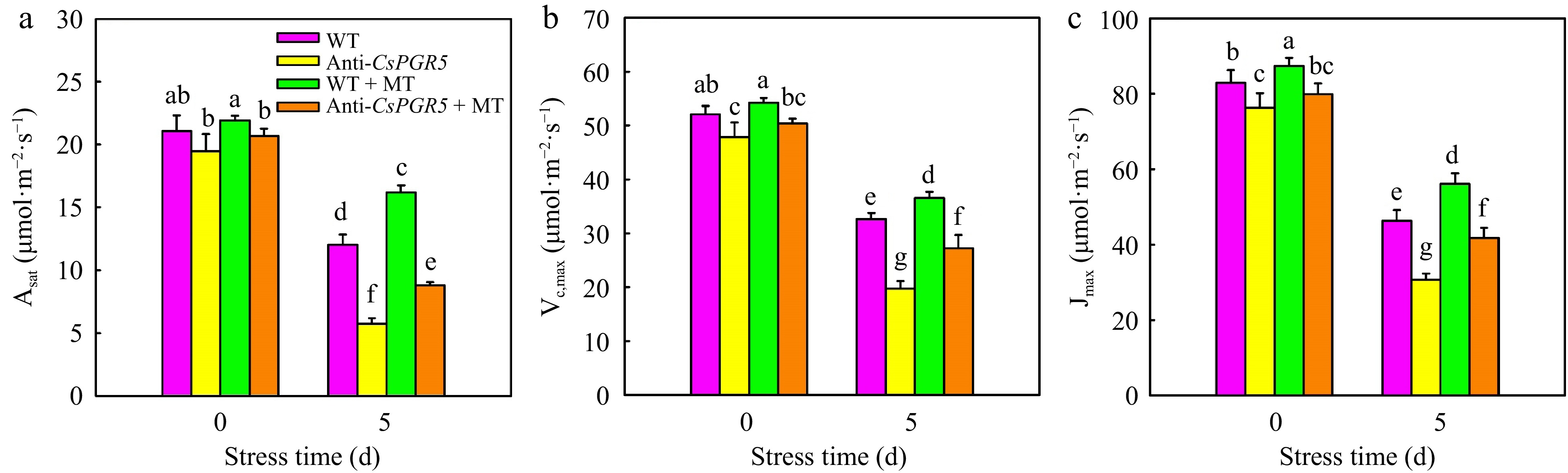

As is known, CEF includes PGR5 (proton gradient regulation 5)/PGRL1 (proton gradient regulation like1) and NAD(P)H dehydrogenase complex (NDH) pathways and PGR5 is usually considered to be the main circular electron transport pathway in C3 plants[37]. Thus, to verify whether PGR5 participates in the regulation of MT on photoprotection under heat stress, PGR5 antisense transgenic cucumber plants were obtained by agrobacterium-mediated method. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S2, the relative expression of PGR5 in transgenic cucumber plants was notably lower than the WT plants. CsPGR5 suppression significantly decreased Pn in cucumber with MT pretreatment and untreated. Moreover, heat stress resulted in the decline of Pn, Gs, Tr, and increase of Ci in all cucumber seedlings. Notably, the application of MT mitigated the decline of Pn, whereas, the Pn in Anti-CsPRG5 was still lower than that in WT seedlings (Fig. 9). In addition, the variation of Asat, Vc,max, and Jmax were in accordance with the Pn (Fig. 10).

Figure 9.

The effect of CsPGR5 inhibition on the gas exchange parameters of cucumber seedlings under high temperature stress. (a) Pn; (b) Gs; (c) Tr; (d) Ci. The two-leaf-stage cucumber seedlings were treated at 42/35 °C for 5 d. All values shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3). Lowercase letters a–g indicate that mean values are significantly different among samples (p < 0.05).

Figure 10.

The effect of CsPGR5 inhibition on Asat, Vc,max, Jmax of cucumber seedlings under high temperature stress. (a) Asat; (b) Vc,max; (c) Jmax. The two-leaf-stage cucumber seedlings were treated at 42/35 °C for 5 d. All values shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3). Lowercase letters a–g indicate that mean values are significantly different among samples (p < 0.05).

Effects of MT on photoinhibition of Anti-CsPGR5 cucumber seedlings under heat stress

-

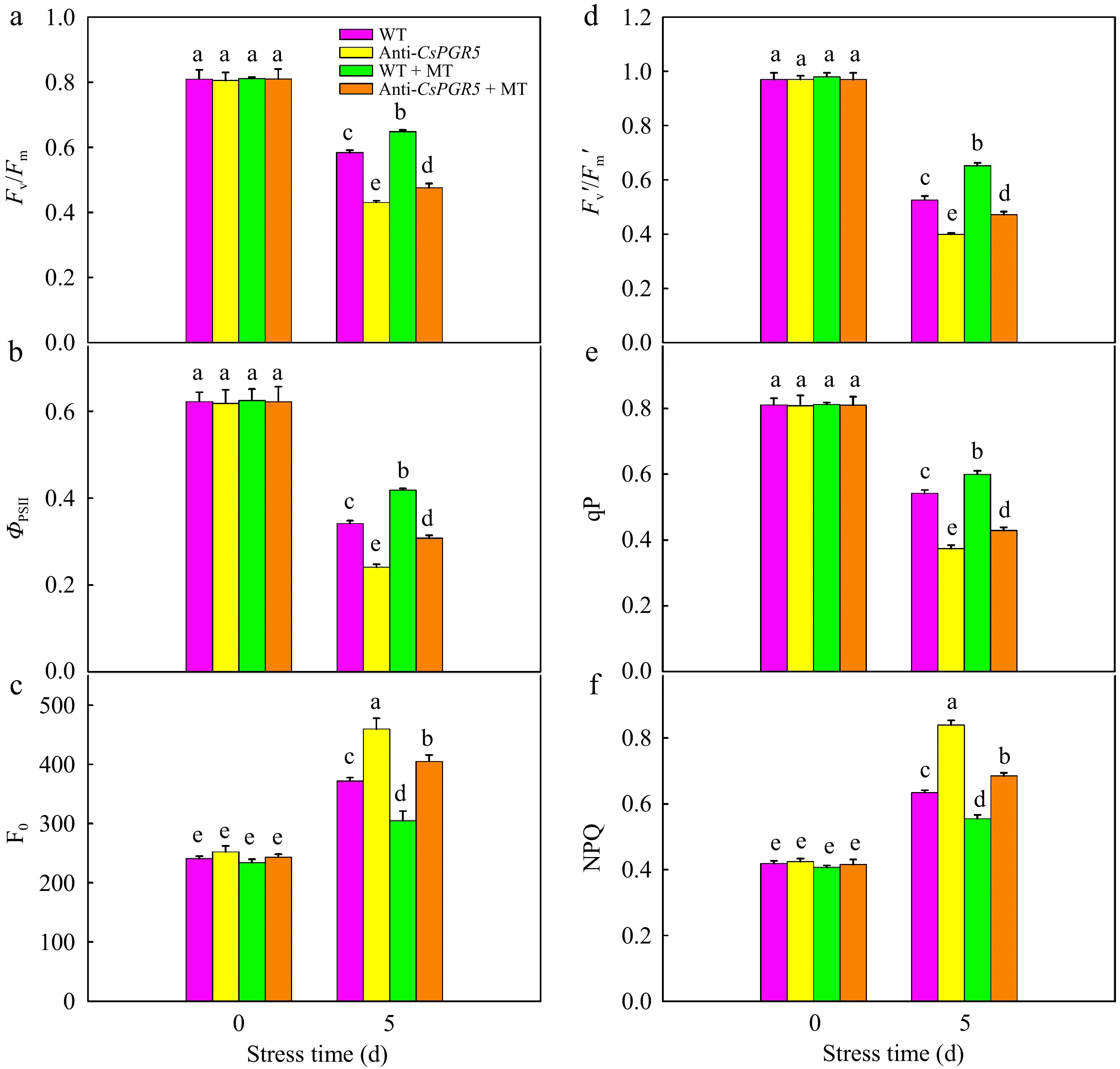

Further studies showed that no significant difference in Fv/Fm, ΦPSII, Fo, Fv'/Fm', qP, and NPQ were observed between WT and Anti-CsPRG5 under normal temperature. After exposed to 42 °C for 5d, Fv/Fm, ΦPSII, Fv'/Fm', and qP decreased, whereas, Fo and NPQ increased in cucumber seedlings in all the treatments. Notably, the inhibition of CsPRG5 aggravated the decline of Fv/Fm, ΦPSII, Fv'/Fm', and qP, compared with the WT (Fig. 11), implying CsPRG5 inhibition expression exacerbated the PSII photoinhibition under heat stress. It was also noticed that the application of MT promoted the photoprotection under heat stress, as indicated by the higher Fv/Fm, ΦPSII, Fv'/Fm', and qP and lower Fo and NPQ than those in seedlings without MT. However, compared to WT + MT, seedlings in Anti-CsPRG5 + MT treatment, showed lower Fv/Fm, ΦPSII, Fv'/Fm', qP, and higher Fo and NPQ. These results indicated that PGR5-mediated CEF played a vital role in the photoprotection induced by MT in cucumber under heat stress.

Figure 11.

The effect of CsPGR5 inhibition on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of cucumber seedlings under high temperature stress. (a) Fv/Fm; (b) ΦPSII; (c) F0; (d) Fv'/Fm'; (e) qP; (f) NPQ. The two-leaf-stage cucumber seedlings were treated at 42/35 °C for 5 d. All values shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3). Lowercase letters a–e indicate that mean values are significantly different among samples (p < 0.05).

-

Previous studies have shown that MT could alleviate the damage to plants caused by abiotic stresses, including heat, chilling, salt, and drought[9,38−40]. Among all abiotic stress, heat stress is the main limiting factor for the growth and productivity of plants cultivated in the summer season. It was demonstrated that the application of MT promoted the thermotolerance of plants via upregulating antioxidant ability and the transcripts of heat-responsive genes[9,23]. It is well known that one of the significant symptoms of heat injury is the decline of photosynthesis. In this paper, it is found that cucumber seedlings showed dried and yellow leaves, higher EL, and heat injury index as well as lower Pn, Asat and Fv/Fm, ΦPSII after 5 d 42 °C heat stress. However, applying melatonin notably alleviated the heat damage to cucumber seedlings and the 100 μmol·L−1 melatonin was the optimum application concentration, which was consistent with the results of Jahan et al.[24]. Despite the available studies on the positive effects of melatonin on improving heat tolerance, a large body of which are principally based on the pharmacological approaches, such as the spraying or root-irrigation of exogenous melatonin. Here, transgenic cucumber plants with CsASMT overexpression or suppression were obtained, which can promote or suppress melatonin biosynthesis in cucumber plants. Jalal et al.[41] reported that the silencing of ASMT/COMT in tomato resulted in a drastic reduction of endogenous melatonin content and then aggravated the oxidative stress damage induced by high-temperature stress. Similarly, it was discovered that CsASMT overexpression increased endogenous MT content and suppression decreased endogenous MT content compared to WT plants. Moreover, compared with WT, OE-CsASMT plants showed higher heat stress tolerance in terms of the normal growth phenotype and higher dry matter, while, Anti-CsASMT plants showed opposite data.

As is known, photosynthesis includes light and dark reaction stage, and the photosynthetic rate is either limited by Calvin cycle, in terms of photosynthetic enzyme activity and expression, such as ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), or limited by electron transport in chloroplast, in terms of PSII and PSI activities[42−44]. The present data showed that heat stress notably caused the decline of Pn and Gs in all cucumber seedlings and the decrease of Pn and Gs accompanied with the increase of Ci in both the transgenic and WT cucumber plants, implying the decline of photosynthesis was caused mainly by non-stomatal factors, which was in accordance with our previous studies[6]. Zhang et al.[45] reported that MT significantly alleviated the decrease of plant growth, leaf chlorophyll content, photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm) and net photosynthesis rate of perennial ryegrass caused by heat stress. Meanwhile, the higher photosynthetic pigment content, Vcmax, Jmax, the Rubisco and RCA activities as well as electron transport efficiency were observed in tomato plants pre-treated with MT[24]. In agreement with this, the Pn and Asat in OE-CsASMT plants with higher endogenous MT content were higher than those in WT cucumber plants in this study, which may be related to the increased activities, gene and protein expression of Rubisco and RCA in OE-CsASMT plants under heat stress. Moreover, OE-CsASMT plants showed higher ΦPSII, Fv/Fm, Fv'/Fm', qP, ETR, and lower F0, NPQ compared with the WT, however, the change of the above parameters was opposite in Anti-CsASMT plants. The D1 protein of PSII is the most attacked site under various abiotic stresses, the repair of which is the main mechanism to alleviate the PSII photoinhibition[46]. Here, it was found that heat stress led to an obvious degradation of D1 protein, the level of which was higher in OE-CsASMT plants and lower in Anti-CsASMT plants than WT. These results indicated that the overexpression of CsASMT promoted the heat dissipation and repair of D1 to relieve the PSII inhibition under heat stress. In addition, chlorophyll a fluorescence transient analysis is usually used to evaluate the damage of the PSII donor side and acceptor side, which were both damaged by heat stress[47]. In this study, it was found that the CsASMT overexpression maintained the electrons transfer of PSII reaction center, in terms of lower Wk, which reflected the OEC damage at the PSII donor side[48], and φEo, which is reflected in the PSII acceptor side[49]. Heat stress also results in the photoinhibition of PSI, which occurred mainly because of the accumulation of photosynthetic reducing power NADPH caused by the blocking of photosynthetic dark reaction[50]. In this study, it was determined that CsASMT overexpression positively mitigated PSI photoinhibition under heat stress, evidenced by higher ΔI/I0 in OE-CsASMT plants and lower ΔI/I0 in Anti-CsASMT plants and it was probably because CsASMT overexpression promoted the utilization of NADPH through enzyme-mediated photosynthetic dark reaction, which further decreased the accumulation of ROS at the PSI terminal. Under abiotic stresses, cyclic electron transport (CEF) around PSI is another important photoprotection mechanism for plants, which contains PGR5/PGRL1-CEF and NDH-CEF, could increase the repair of PSII light damage[51,52], and PGR5 was reported to be the main pathway[53]. Here, it was found that heat stress resulted in the decline of ETR (I) and ETR (II) and increase of CEF. Compared to the control, the application of MT notably increased the ETR (II) and decreased the CEF. Moreover, the suppression of CsPGR5 in cucumber seedlings obviously aggravated the decrease of Fv/Fm, ΦPSII, Fv'/Fm', and qP caused by heat stress, which further led to the decline of photosynthesis, compared to WT, implying PGR5-dependent CEF was another important mechanism of MT in the regulation of photosynthesis under heat stress.

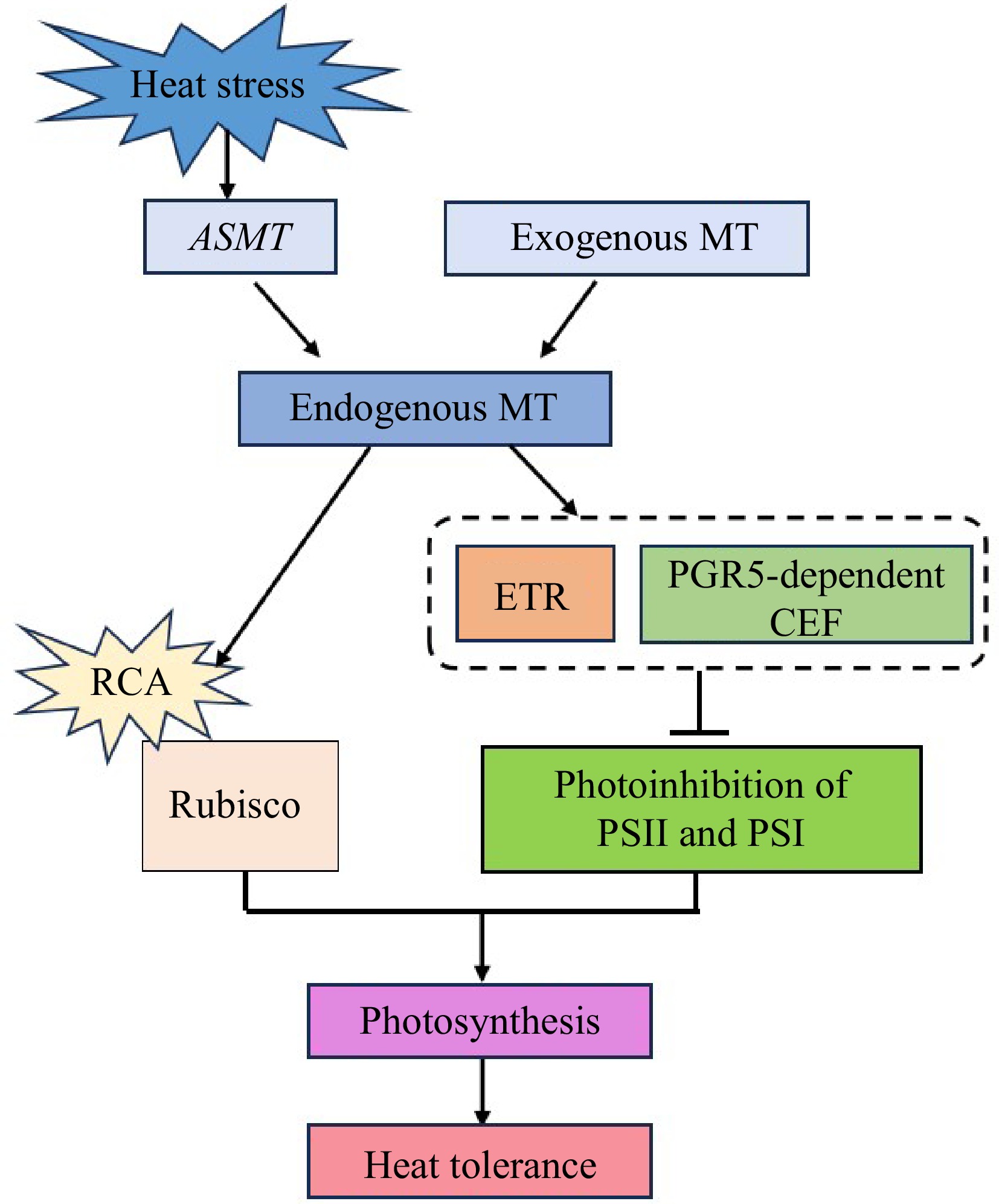

-

In summary, the application of exogenous MT or overexpression of CsASMT can improve endogenous MT content, promote heat tolerance of cucumber seedlings through the regulation of photosynthesis, via promoting the photosynthetic carbon assimilation capacity, maintaining the linear electron transport, and increasing PGR5-dependent CEF to alleviate the photoinhibition of PSII and PSI under heat stress (Fig. 12).

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFD1000800); the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2023MC183); the Special Fund of Modern Agriculture Industrial Technology System of Shandong Province in China (SDAIT-05-10).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study design and manuscript revision: Bi H, Ai X; experiment performing, data analysis and draft manuscript preparation: Jiang T; experiment assisting: Feng Y, Zhao M, Meng L, Li J, Zhang X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 The primer sequences of qRT-PCR

- Supplementary Fig. S1 The effect of CsASMT overexpression and inhibition on MT content and CsASMT mRNA abundance. (a) MT content; (b) CsASMT mRNA abundance. All values shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3). Lowercase letters a–c indicate that mean values are significantly different among samples (p < 0.05).

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Genetic transformation and identification of cucumber. (a−e) Cucumber genetic transformation tissue culture process; (f) PCR verification of T0 generation transgenic plants; (g) expression of CsPGR5 gene in T0 transgenic plants. All values shown are the mean ± SD (n = 3). Lowercase letters a–c indicate that mean values are significantly different among samples (p < 0.05).

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang T, Feng Y, Zhao M, Meng L, Li J, et al. 2024. Regulation mechanism of melatonin on photosynthesis of cucumber under high temperature stress. Vegetable Research 4: e037 doi: 10.48130/vegres-0024-0037

Regulation mechanism of melatonin on photosynthesis of cucumber under high temperature stress

- Received: 26 May 2024

- Revised: 29 September 2024

- Accepted: 11 October 2024

- Published online: 11 December 2024

Abstract:

-

Key words:

- Melatonin /

- CsASMT /

- Photosynthesis /

- Photoinhibition /

- Cyclic electron flow /

- Heat stress /

- Cucumber