-

Myopia is one of the most common visual disorders among school-aged children in Asia, especially in countries such as China, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea. In the past decade, myopia's prevalence has been continuously increased and has become a major disease affecting health. The number of people suffering from myopia was expected to reach almost 50% by 2050. Due to Coronavirus (COVID-19), the incidence of myopia in Chinese students has increased by 11.7% in the last 6 months[1−3].

There are various interventions currently available to control myopia. Some optimistic results have been proposed, such as Orthokeratology (OK), different dose atropine, soft contact lenses, peripheral defocus modifying spectacle lenses (PDMSL), and rigid gas-permeable contact lenses (RGP). However, these treatment methods need to be improved. For example, keratitis from corneal contact lenses, and side effects of atropine medication, etc. There needs to be a consensus on the prevention and control of myopia.

RLRL (repeated low-level red-light) therapy for myopia control has emerged as an effective therapy. It is a device emitting 650 nm visible red light. Clinical studies have demonstrated RLRL to be effective in reducing myopia progression rates[4,5]. RLRL therapy, compared with single-vision spectacles, was an effective treatment for myopia after a 12-month, multicentre, randomized clinical trial[5]. In addition, some clinical studies have found that PDMSL could also effectively control the progression of myopia. These types of spectacles were designed based on the peripheral retina myopic defocus theory[6−8].

In this study, we will focus on the effect of myopia control between RLRL and PDMSL in children with medium-high myopia (≥ −4.00 D).

-

A randomized, prospective, controlled clinical trial was performed with children with medium to high myopia. From August 2021 to March 2023, this research was conducted at Xinhua Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China. During the study's planning phase, all the investigators and personnel received training on the study's procedures. Children in this study were randomized 1:1 to either RLRL or PDMSL groups. In the RLRL group, the children would wear single-vision spectacles (SVS), (Essilor, France), which were worn for ≥ 12 h a day following a 3 min treatment schedule twice a day. The interval between sessions should be ≥ 4 h. In the PDMSL group, the children wore peripheral defocus modifying spectacle lenses (MyoVision, ZEISS, Germany) daily. PDMSL lenses were worn for ≥ 12 h a day.

The Ethics Committee of Xinhua Hospital Affiliated with Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine approved this study according to the Declaration of Helsinki (Approval XHEC-C-2021-005-2). As outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, a parent or legal guardian provided written informed consent and a child also provided informed consent. This trial has been registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT05184621, Date: 11/01/2022).

Eligibility criteria

-

The participants were school students with moderate to high myopia in both eyes, aged from 8 to 14 years old. Medium to high myopia is defined as cycloplegic spherical equivalent refraction of the more myopic eye of −4.00 or more diopters (D). Any child with astigmatism exceeding 2.00 D, strabismus, amblyopia, any systemic disease, or any other intervention history for myopia therapy were excluded.

Masking and randomization

-

Following eligibility verification and consent, participants were divided in a 1:1 ratio into an experimental group (RLRL plus SVS) or a control group (PDMSL). Two investigators (YJ and LB) allocated treatments. Closed sealed envelopes with randomized numbers were used for drawing lots. A statistician not involved in participant recruitment or data collection generated the random allocation sequence using randomized block methods in SPSS.26 (SPSS Institute).

Intervention

-

In the experimental group, children received RLRL treatment and wore SVS daily. The children in the control group did not, only wearing PDMSL daily. RLRL treatment delivered red light with a wavelength of 650 nanometers through semiconductor laser diodes on a desktop (Eyerising, Suzhou Xuanjia Optoelectronics Technology). China National Medical Products Administration certified the device as class IIa[9]. Five days a week, RLRL treatment was administered twice daily for 3 min, with at least a 4-h interval between sessions.

Data collection

-

The relational ophthalmic examinations were executed at the outset, then 3-month, 6-month, 9-month, and 12-month follow-up visits. Uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) and best corrected visual actity (BCVA) were assessed by optometrists using a logMAR chart (Shenguang, China) at 5 m from the chart. A measurement of axial length (AL) was made using an IOL Master 500 (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Germany). The SER was calculated as the sum of the spherical diopter and half of the cylindrical diopter. An autorefractor (KR8800, Topcon, Japan) measured refraction data at each eye. Cycloplegia was measured at the initial point and at the 6- and 12-month follow-up checks. Participants received 0.5% tropicamide (Jinyao, China) as a cycloplegic agent. The usage method of the cycloplegic agent was as follows: two drops in each eye, for 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20 min. The pupil was then checked. A pupil measuring 6 mm or more was considered cycloplegia. Optometry was carried out after cycloplegia. Scan images and fundus images were obtained with swept-source optical coherence tomography (OCT) (IVUE100, Optovue, USA).

Adverse events

-

All participants were analyzed for safety. The children and their parents were asked to report any side effects at each follow-up appointment. Dizziness, glare, flicker blindness, afterimage time, or vision loss were among the questions. Potential side effects of RLRL were also noted. A senior ophthalmologist at each research site used OCT to examine fundus images for underlying lesions that did not show clinical signs. The data safety monitoring committee determined whether any adverse events were related to treatment.

Statistical analysis

-

The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS .26 (SPSS Institute Inc). Gender differences between the two groups were compared using an χ2 test. A nonparametric statistical method was used if the continuous outcomes were not distributed normally, and the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used in the case that the continuous outcomes were not distributed normally. A P value of 0.05 was deemed statistically significant in all 2-sided tests.

-

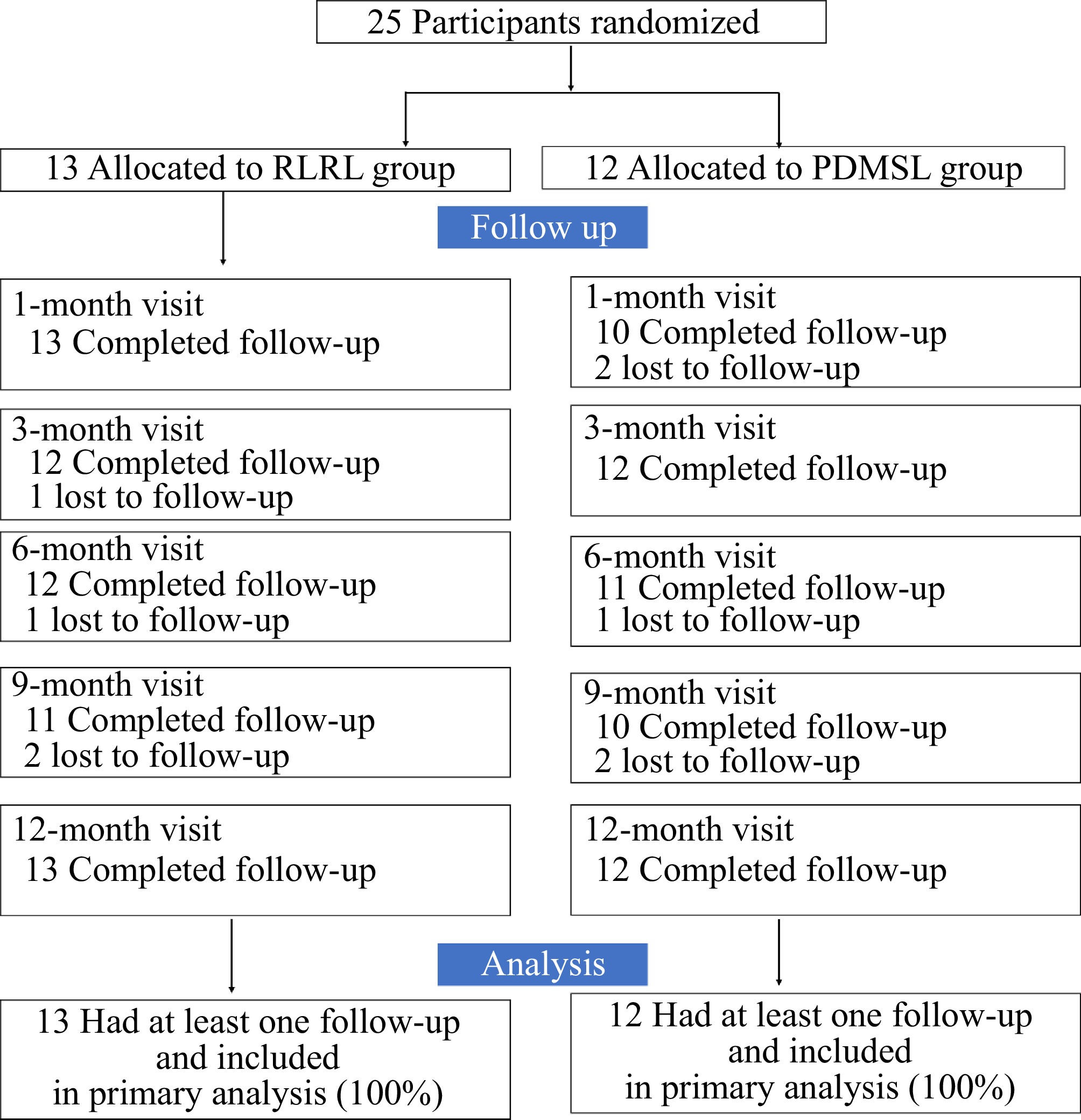

The trial involved 25 children: 25 (mean [SD] age, 10.48 [1.87] years, 16 boys [64%]). There were 13 children (mean [SD] age, 10.54 [2.03] years, nine boys [69.2%]) in the experimental group and 12 children (mean [SD] age, 10.42 [1.78] years, seven boys [58.3%]) in the control group. Children's enrollment, intervention, baseline examination, and follow-ups after 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month are shown in Fig. 1. All children had completed the follow-up. However, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, some children missed follow-up at certain points.

Figure 1.

Study design and flow diagram of the randomized, controlled clinical trial. RLRL = repeated low-level red-light. PDMSL = peripheral defocus modifying spectacle lenses.

Characteristics of the baseline

-

RLRL and PDMSL groups had similar mean standard deviations of age and the proportion (%) of children who were male (10.54 [2.03] years vs 10.42 [1.78] years; male sex, 69.2% vs 58.3%). According to Table 1, baseline SER and AL did not differ significantly between the two groups.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study participants.

Characteristics RLRL (n = 13) PDMSL (n = 12) p value Age (years) 0.88 Mean ± SD 10.54 ± 2.03 10.41 ± 1.78 Median (IQR) 10.54 (8−14) 10.41 (8−13) Sex Male 9 (69.23%) 7 (58.33%) 0.88 Female 4 (30.77%) 5 (41.67%) SER (D) Mean ± SD −5.36 ± 1.32 −4.73 ± 1.08 0.07 Median (IQR) −5.50 (−4.25 to −6.50) −4.50 (−4.31 to −5.00) AL (mm) Mean ± SD 25.74 ± 0.88 25.59 ± 0.91 0.55 Median (IQR) 25.58 (25.14 to 26.03) 25.53 (24.78 to 26.27) All patients were randomly assigned. Al = axial length; D = dipoter; IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation; SER = spherical equivalent refraction. Outcomes

-

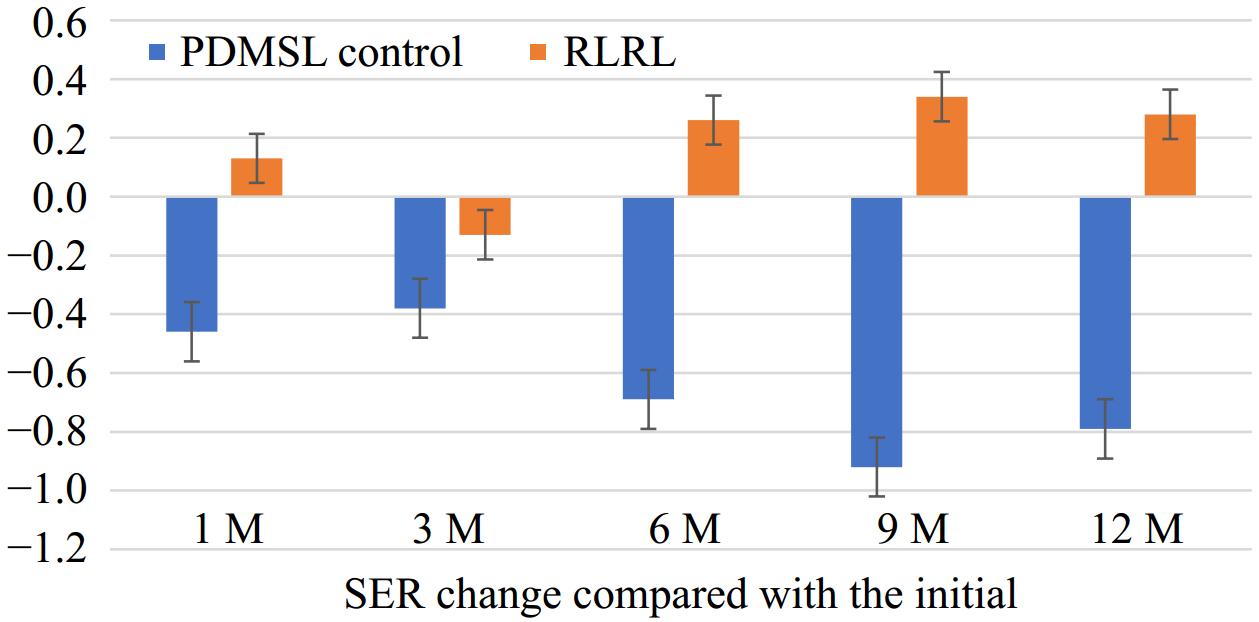

Figure 2 shows the SER change between every follow-up visit and the initial time. SER change was 0.13 ± 0.34D in 1-month, −0.13 ± 0.50D in 3-month, 0.26 ± 0.39D in 6-month, 0.34 ± 0.51D in 9-month, 0.28 ± 0.50D in 12-month, in RLRL group. And in the PDMSL group, SER change was −0.46 ± 0.41D in 1-month, −0.38 ± 0.41D in 3-month, −0.69 ± 0.39D in 6-month, −0.93 ± 0.44D in 9-month, −0.79 ± 0.48D in 12-month. Among them, there was a significant difference in 6-month, 9-month, and 12-month between the two groups.

Figure 2.

SER change compared with the initial time. SER = spherical equivalent refraction. D = diopter.

The mean SER change after 12 months was −0.79 D (95% CI, −1.35 to −0.59) in the PDMSL group, and 0.28 D (95% CI, 0.08 to 0.48) in the RLRL group. The mean SER difference between PDMSL and RLRL groups after 12 months was −1.07 D (95% CI, −1.35 to −0.79; p < 0.001).

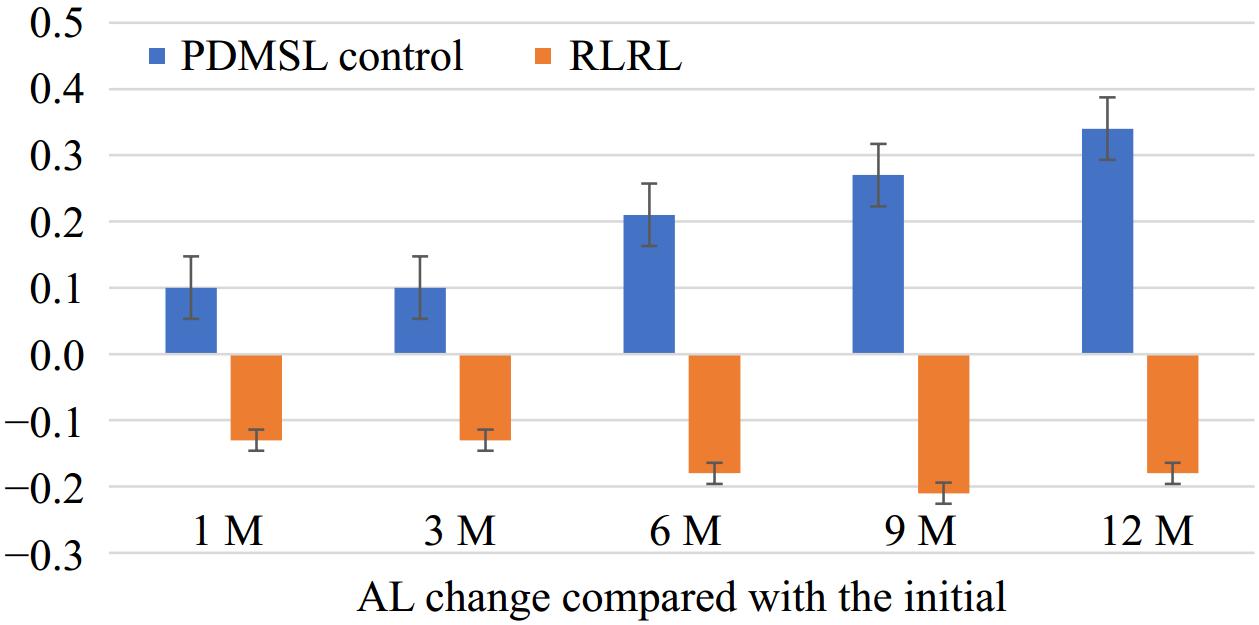

Figure 3 shows the AL change between every follow-up visit and the initial time. In the RLRL group, AL change was −0.13 ± 0.93 mm at1-month, −0.13 ± 0.11 mm at 3-month, −0.18 ± 0.13 mm at 6-month, −0.21 ± 0.16 mm at 9-month, and −0.18 ± 0.17 mm at 12-month. In the PDMSL group, AL change was 0.10 ± 0.23 mm at 1-month, 0.09 ± 0.01 mm at 3-month, 0.21 ± 0.09 mm at 6-month, 0.27 ± 0.14 mm at 9-month, and 0.34 ± 0.13 mm at 12-month respectively. Among them, there were significant differences at 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month between the two groups (p < 0.001).

The mean AL change at 12 months was 0.34 mm (95% CI, 0.29 to 0.40 mm) in the PDMSL group and −0.18 mm (95% CI, −0.25 to −0.11 mm) in the RLRL group. Thus, the mean difference in AL change between the two groups at the 12-month follow-up was 0.52 mm (95% CI, 0.44 to 0.61 mm; p < 0.001).

Adverse events

-

No structural damage was detected in RLRL or PDMSL based on swept-source OCT images.

-

This study was among the earliest clinical trials investigating myopia control among children with medium to high myopia. The results of this randomized, controlled clinical trial indicated that RLRL therapy was superior to PDMSL in controlling AL and SER of myopic children. It was therefore considered that RLRL therapy was more effective than PDMSL in controlling myopia.

Repeated low-level red light effects on spherical equivalent refraction

-

In Fig. 2, we found a decrease in diopter relative to the initial time in the RLRL group. However in the PDMSL group, the diopter still increased by months. In the RLRL group, SER change was 0.28 ± 0.50D at 12-month. In the PDMSL group, the SER change was 0.79 ± 0.48D at 12-month. This suggested that during the one year follow-up visit, the participants' refraction was effectively controlled after using RLRL therapy.

Axial length shortening

-

Figure 3 shows that the AL was shortening in the RLRL group compared with the initial time. The shortening of AL was most noticeable during the 9-month visit. While at the 12-month visit, AL returned to the baseline level. However, the results also indicated that the growth of myopia has been controlled or retarded by using RLRL treatment. Previous studies on RLRL therapy have also observed this phenomenon[2−6,9,10]. However the cellular and molecular mechanisms of red light need to be clarified. Some experimental myopia research suggested the AL progression could lead to thinning of the choroid membrane and slower blood flow. This affected the supply to the retina and subsequent hypoxia[11,12]. When AL slowed down, this situation would be improved. Thus, maybe it was a part of the pathway in RLRL treatment. In addition, some research had found that 660 nm of red light could be regulated by HIF-1 α, the expression of which could promote the expression of scleral fibroblasts. RLRL could control the progression of myopia through another pathway[13,14].

Some studies have also reported comparisons of the efficacy of RLRL with other treatments for myopia control. A retrospective study on Orthokeratology and RLRL suggested that RLRL demonstrated slightly superior efficacy in controlling myopia progression in children compared with orthokeratology lenses[15].

A single-masked, single-center, randomized controlled trial to compare the treatment efficacy between RLRL therapy and 0.01% atropine eye drops for myopia control also pointed out that RLRL was more effective for controlling AL and myopia progression over 12 months of use compared with 0.01% atropine eye drops[16].

Safety

-

The China National Medical Products Administration approved the RLRL device used. In our study, no participant withdrew due to the inability to adapt to red light exposure. There were no reports of fundus structural damage during OCT examination. There was a case of retinal damage incurred in RLRL use[17]. A child with high myopia experienced a decline in vision accompanied by a disruption in the ellipsoid zone after 5 months of RLRL use. Although the child's vision recovered after discontinuing the use, this case underscores the importance of rigorous monitoring for adverse effects. Regular ophthalmic examinations must be conducted during RLRL treatment.

Study limitations

-

Several limitations should be noted in this study. Firstly, the study only lasted 12 months. There was insufficient data to determine the full effect of myopia control on myopia. Secondly, this study's sample size was relatively small (25 sample total, 13 samples in the RLRL group, 12 samples in the control group). Thirdly, the COVID-19 lockdown overlapped with the clinical trial. Screen-based learning online may have accelerated children's myopia progression, and that may have affected both groups equally.

-

According to the study, RLRL therapy was effective in controlling myopia compared to PDMSL therapy. A well-tolerated RLRL therapy was not associated with any adverse effects. For further confirmation of the findings, long-term clinical follow-up and an understanding of the mechanism of red-light controlling myopia are needed.

-

This study upheld the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Ethics Committees of Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine approved the study protocol (approval XHEC-D-2023-126). The guardians of the participants provided written informed consent, and the children provided verbal consent.

This study was funded by Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province of China (2023J011581), Huaxia Scientific Research Funding (HXKY202304D003/HXKY202305D004), and Specialized Key Discipline Construction Projects of the 14th Five-Year Plan in Chancheng District, Foshan City.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: data collection, analysis, draft manuscript preparation: Yu J, Li B, Li X; data curation and database management: Yu J, Zhang C; study designe: Zhu H, Zhao P; manuscript revision and study supervision: Dong L, Cen J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Jun Yu, Bin Li, Xiangbo Li

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published byMaximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This articleis an open access article distributed under Creative CommonsAttribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yu J, Li B, Li X, Dong L, Cen J, et al. 2025. Efficacy comparison between repeated low-level red-light therapy and peripheral defocus spectacles to slow the progression of medium to high myopia in Chinese children. Visual Neuroscience 42: e002 doi: 10.48130/vns-0025-0001

Efficacy comparison between repeated low-level red-light therapy and peripheral defocus spectacles to slow the progression of medium to high myopia in Chinese children

- Received: 06 November 2024

- Revised: 19 January 2025

- Accepted: 21 January 2025

- Published online: 14 February 2025

Abstract: Repeated low-level red-light therapy (RLRL) has recently emerged as a new type of treatment to control myopia. In our study, we aim to compare the effects of RLRL and peripheral defocus modifying spectacle (PDMSL) in Medium-High myopia. This study is a randomized controlled trial. The participants were 25 children with ≥ −4.00 diopters (D) of myopia. Groups of intervention (RLRL) and control (PDMSL) were assigned 1:1. In the RLRL group, the participant would use the device and wore single-vision spectacles daily. In the control group, the participant wore PDMSL daily. The axial length, spherical equivalent refractions, and other ophthalmic examinations were measured at baseline, one, three, six, nine, and 12 months. There were 13 children in the RLRL group, and 12 children in the PDMSL group. Spherical equivalent refraction change was 0.28 ± 0.50D and −0.79 ± 0.48D at 12 months, in both groups, respectively. There was significant difference (p < 0.001). Axial length change was −0.18 ± 0.17 mm and 0.34 ± 0.13 mm at 12 months in both groups, respectively. There was significant difference (p < 0.001). There were no adverse events reported that were related to the treatment. RLRL was more effective in myopia control. RLRL could be well tolerated, with few adverse effects related to the treatment.

-

Key words:

- Repeated low-level red-light /

- Myopia /

- Spherical equivalent /

- Axial length