-

Crabapples (Malus spp.) are native to Asia, Europe, and North America. Crabapple has a long history of cultivation and is recognized as one of China's traditional and renowned ornamental flowers. Its flowers exhibit a wide spectrum of colors, complemented by the vibrant hues of its leaves and fruits, which together provide significant ornamental value and ecological adaptability. Therefore, it has been extensively used in gardening[1,2]. The colors of flowers, leaves, and fruits play an important role in ornamental plants, directly influencing both ornamental and commercial value[3,4]. Crabapple petals, leaves, and fruits display different colors at various stages of development.

The color of plant tissues is determined by the location, proportion, and content of phytochromes within cells[5]. In addition to chlorophyll, which is predominantly found in green tissues, flavonoids and carotenoids are the primary pigments responsible for plant coloration[6]. Flavonoids are important phenolic compounds in plants, which are composed of two aromatic rings connected to a heterocyclic benzopiranon[7,8]. Flavonoids can be categorized into various types based on the attachment position of the aromatic rings and the structure of carbon bonds, including flavonols, flavanones, flavanols, anthocyanins, and isoflavones[9,10]. Among flavonoids, anthocyanins are the most prominent, imparting plants with vibrant red, blue, and purple hues[11]. Flavonols, flavanols, and phenolic acids often act as co-pigments for anthocyanins[12]. Carotenoids, a subclass of terpenoids, are vital pigments that provide yellow and orange hues to plant tissues[13]. For example, the coloration of petals in various Brassica napus is primarily influenced by the types and concentrations of flavonols and anthocyanins[14]. In Rosa hybrida, petals of different colors contain varying fractions of anthocyanins. Fuchsia petal coloration is predominantly attributed to cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside, while orange petals are co-regulated by anthocyanins and carotenoids. In contrast, white petals contain minimal to no anthocyanins[15]. The shift in leaf color in Padus virginiana L. is due to differences in chlorophyll, carotenoid, and anthocyanin content[16]. Similarly, in fruits like Crimson Seedless[17] and Garcinia mangostana[18], the pericarp is rich in anthocyanins and flavonoids, resulting in red or purple hues at maturity.

Crabapple petals, leaves, and fruits contain high levels of secondary metabolites, such as flavonoids. As antioxidants, flavonoids play a crucial role in protecting plants from ultraviolet radiation, microbial infections, and pest damage[19,20]. In addition, these pigmentation substances not only attract insects and birds to spread pollen and seeds, but they also offer health benefits, including antioxidant, anti-aging, anti-cancer, anti-bacterial, and anti-inflammatory effects, along with blood glucose regulation[21−23].

Although studies on the flower, leaf, and fruit colors of crabapple exist, most focus on specific species. There is a notable lack of systematic analyses addressing the mechanisms of coloration across multiple color lines and developmental stages. In this study, 13 ornamental crabapple cultivars were used to determine the composition and content of pigment components in flowers, leaves, and fruits at different stages. Polyphenols were quantitatively analyzed using high performance liquid chromatography coupled with a diode array detector (HPLC-DAD), and the effects of pigment composition on the coloration of crabapple flowers, leaves, and fruits were explored through Pearson correlation analysis. This study provides a theoretical basis for further research on the genetic regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in crabapple, and offers a foundation for the selection and breeding of new crabapple cultivars, as well as for the promotion and application of valuable germplasms.

-

The experimental materials were collected from February to December 2023 at the crabapple resource nursery of Northwest A&F University (Yangling, Shaanxi Province, China). The location of this resource nursery is flat, with consistent soil conditions, fertilization, and growing environment conditions. The experimental materials included M. 'Huangzhenzhu', M. micromalus, M. 'Guifeihong', M. 'Shengdanguo ', M. 'Strawberry Parfait', M. 'Profusion', M. halliana, M. 'Brandywine', M. 'Red Splender', M. 'Radiant', M. 'Shotizam', M. 'Sparkler', and M. 'Royalty', a total of 13 crabapple germplasms (Table 1). The materials were harvested at different developmental stages based on color changes in petals, leaves, and fruits. In this study, the flower development stages of crabapple were divided into five stages, namely, small bud stage (Stage 1, S1), large bud stage (S2), initial flowering stage (S3), full flowering stage (S4), and final flowering stage (S5)[24]. Small bud stage means that the bud is in the early stage of development and the bud is small. In the big bud stage, the buds are all exposed and balloon-shaped. At the initial flowering stage, the petals at the top of the flower are slightly open, and the pistils and stamens are exposed. Flowers are in full bloom at full flowering stage. At the final flowering stage, the flowers begin to wilt and the petals are about to fall off.

Table 1. Germplasm information of tested crabapple.

Code Scientific name N1 M. 'Huangzhenzhu' N2 M. micromalus N3 M. 'Guifeihong' N4 M. 'Shengdanguo' N5 M. 'Strawberry Parfait' N6 M. 'Profusion' N7 M. halliana N8 M. 'Brandywine' N9 M. 'Red Splender' N10 M. 'Radiant' N11 M. 'Shotizam' N12 M. 'Sparkler' N13 M. 'Royalty' According to the different stages of leaf development of crabapple, three stages with obvious leaf color changes were selected[25]. They are leaf-spreading stage (S1), which usually occurs from the end of March to the beginning of April, and one or two spreading leaves appear. In the maturation stage (S2), from the end of April to the beginning of May, the leaves are flat. In the aging stage (S3), the leaves enter the late mature stage, and the autumn leaves turn yellow.

According to the growth and development period of crabapple fruit, it was collected in mid-May, mid-July, and mid-September respectively. Three different stages of crabapple fruit were picked, namely young fruit stage (S1), fruit expansion stage (S2), and mature stage (S3)[26].

During sampling, three individual plants with consistent growth vigor and free from pests and diseases were selected, and three biological replicates were performed. Samples were collected from different parts of each plant, and fresh samples were taken. After weighing 0.1 g, they were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen to ensure the integrity of the samples.

Measurement of color index

-

In this study, the color of crabapple petals, leaves, and fruits was determined using a colorimeter CR-400 (Konica Minolta, Japan) in a well-lit room. The measurement position and angle were kept consistent throughout the process. Ten replications were performed for each sample, and the mean value was calculated to represent the color information. The luminance (L*) value serves as a measure of lightness and darkness, where a larger L* value indicates a brighter color. The chrominance a* value, which ranges from negative to positive, represents the transition from green to red. Similarly, the chrominance b* value, also ranging from negative to positive, signifies the transition from blue to yellow.

Pigment extraction

-

A 0.1 g fresh sample was quickly ground into a powder in liquid nitrogen and then added to a centrifuge tube containing 2.5 mL of methanol for extraction. The extraction conditions were set at 4 °C for 48 h in the dark, during which the extract was inverted every 8 h to ensure adequate extraction of the pigments. Afterward, the extract was centrifuged for 15 min at 4 °C and 6,000 rpm, and the supernatant was collected and stored at 4 °C. Each sample determination included three biological replicates, and three technical replicates.

Determination of total chlorophyll and carotenoids

-

A 0.1 g fresh sample was quickly ground to a powder in liquid nitrogen, then added to a centrifuge tube containing 96% ethanol solution and extracted at 4 °C in the dark for 30 h. Three biological replicates were conducted for all the experiments. The absorbance values of the extracts at 665, 649, and 470 nm were determined using a UV spectrophotometer. The chlorophyll and carotenoid contents were calculated from these values[27]. The calculation formulas are as follows:

$ \mathrm{\rm{C}_a=13.95\times A_{665}-6.88\times A_{649}} $ $ \mathrm{\rm{C}_b=24.96\times A_{649}-7.32\times A_{665}} $ $ \rm{C}\mathrm{_{a+b}=C_a+C_b}=6.63\times\mathrm{A}_{665}+18.08\times\mathrm{A}_{649} $ $ \mathrm{\rm{C}_x=(1,000\times A_{470}-2.05\times C_a-114.8\times C_b)})/245 $ $ \mathrm{\rm{C}hloroplast\; content\; (mg/g\; FW)=(C\times V)/M} $ A470, A649, and A665 are the absorbance of ethanol extract at 470, 649, and 665 nm, respectively. Ca, Cb, Ca+b, and Cx are respectively the concentrations of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoid (mg/L). The V is the constant volume of chloroplast pigment extract (L), and M is the weight of the sample (g). Fresh Weight (FW) refers to the weight of the biological samples in their fresh, hydrated state before freezing.

Determination of total anthocyanin content (TAC)

-

The method for determining TAC was based on the methanolic hydrochloric acid method[28]. Eight hundred μL of the extract was added to 25 μL of HCl (12 mmol/L), mixed thoroughly, and reacted under light-protected conditions at room temperature for 15 min. The absorbance values of the reaction solution at 530, 620, and 650 nm were determined using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer. A standard curve for TAC was created using cyanidin-3-O-diglucoside, and the results were expressed in (mg/g FW).

Determination of total flavonoid content (TFC)

-

The TFC was determined using an aluminum chloride assay[29]. First, 1.25 mL of ultrapure water and 0.25 mL of the extract were added to a 10 mL centrifuge tube. Then, 75 µL of 5% NaNO2 solution and 0.15 mL of 10% AlCl3 solution were added to the mixture, which was thoroughly mixed. The reaction was allowed to proceed at room temperature for 6 min. Subsequently, 0.5 mL of 1 M NaOH solution and 0.275 mL of ultrapure water were added. Finally, the absorbance value of the reaction solution at 510 nm was determined. A standard curve for TFC was constructed using catechins, and the TFC was expressed in (mg/g FW).

Determination of total polyphenol content (TPC)

-

The TPC was determined by the Folin-Ciocalteu method[30]. Firstly, 0.5 mL of ultrapure water and 0.125 mL of extract solution were added to a 10 mL centrifuge tube, followed by the addition of 0.125 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. The mixture was thoroughly mixed and allowed to react for 6 min at room temperature in the dark. Subsequently, 1.25 mL of 7% Na2CO3 solution and 3 mL of ultrapure water were added, and the mixture was mixed well before being allowed to react for 90 min at room temperature in the dark. Finally, the absorbance of the reaction solution was measured at 760 nm. A standard curve for TPC was prepared using gallic acid, and the TPC was expressed in (mg/g FW).

Analysis of phenolic metabolites

-

HPLC model L-2455 equipped with a diode array detector (Shimadzu, Japan), was used to detect the types and contents of monomeric phenols in the petals, leaves, and fruits of crabapple. A 1 mL sample of methanol extract was taken and filtered through a 0.22 µm filter before being loaded for detection. The instrumental parameters included a Lachrom-C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm), a column temperature of 40 °C, an injection volume of 10.00 µL, and a flow rate of 0.50 mL/min. The mobile phases comprised solution A, which was a 0.04 % formic acid solution, and solution B, which was pure acetonitrile. The gradient elution program was as follows: at 0 min, 5 % B; at 40 min, 40 % B; at 45 min, 100% B; at 55 min, 100 % B; and at 60 min, 100 % B[24]. The content of phenolic compounds was determined by comparing retention times and UV spectral data, and concentrations were calculated using the corresponding standard curve (Supplementary Table S1).

Statistical analysis

-

Three biological and three technical replications were conducted for all the experiments during the determination of pigmentation substances content, and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The raw data were processed and calculated using Excel software and then statistically analyzed and plotted by Origin 2021 and SPSS Statistics 27. Image processing of color variation of flowers, leaves, and fruits of different Crabapple germplasm resources was drawn using Adobe Photoshop 2019.

-

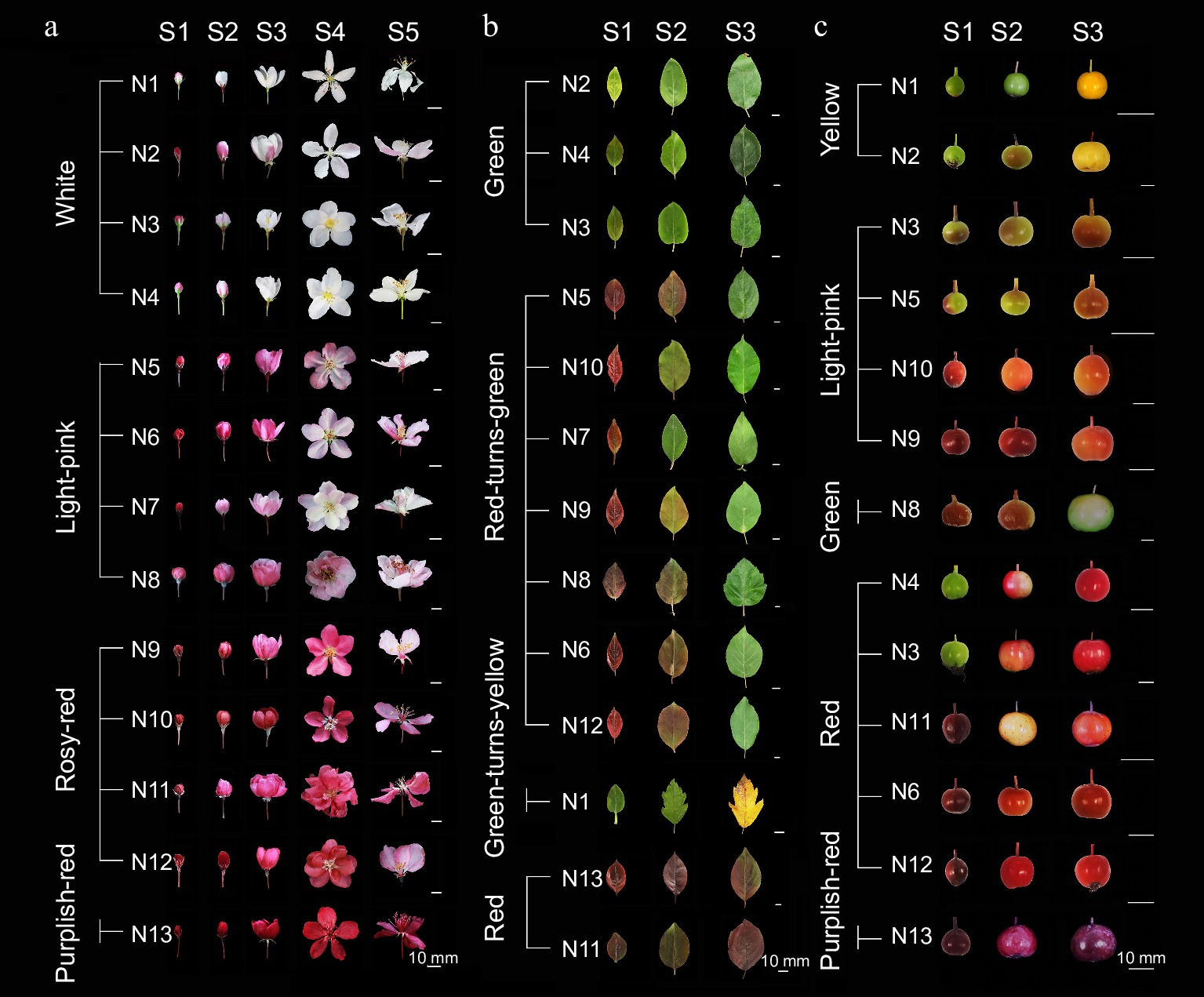

The 13 crabapple cultivars were classified into white, light-pink, rosy-red, and purplish-red lines based on the flower color at various developmental stages (Fig. 1a). At the small bud stage (S1), crabapple petals exhibited red or deep red color. As the flowers grow and develop, their coloration gradually fades. In the white-line crabapples, the petals significantly fade at the large bud stage (S2), with the red color nearly disappearing by the first flowering stage (S3). The light-pink crabapples turn pink at full bloom (S4) and become light pink by the last bloom stage (S5). Rosy-red crabapples fade to pink between S4 and S5. In contrast, the petals of purplish-red crabapples remain purplish-red throughout flower development, showing minimal color change.

Figure 1.

Phenotypic changes of 13 crabapple cultivars during development. (a) S1−S5 petal color change process. (b) S1−S3 leaf color change process. (c) S1−S3 fruit color change process.

Based on the differences in leaf color during development, the 13 crabapple cultivars were classified into green, red, red-turns-green, and green-turns-yellow lines (Fig. 1b). In the green-line, leaves remain green from expansion to maturity (S1−S3). In the red-turns-green-line, the leaves appear purple or red at S1, gradually losing their red coloration as they develop. The rate of this red-turns-green transition varies among cultivars, with leaves becoming entirely green by S3. Leaves in the red-line display varying degrees of purple-red throughout all development stages. In contrast, the green-turns-yellow-line undergoes a distinct transformation, with leaves transitioning fully from green to yellow by S3.

Crabapple fruit colors are rich and vary during development. Based on the different fruit colors at maturity (S3), the 13 crabapple cultivars were classified into yellow, light-red, green, red, and purplish-red-lines (Figs 1c, 2c). Yellow crabapple fruits exhibit significant color changes at different developmental stages, appearing green at the young fruit stage (S1) and turning yellow by maturity (S3). The light-red and red crabapple fruits show two distinct patterns of color change: from green to red and from purplish red. The purplish-red fruits maintain varying degrees of purple throughout development.

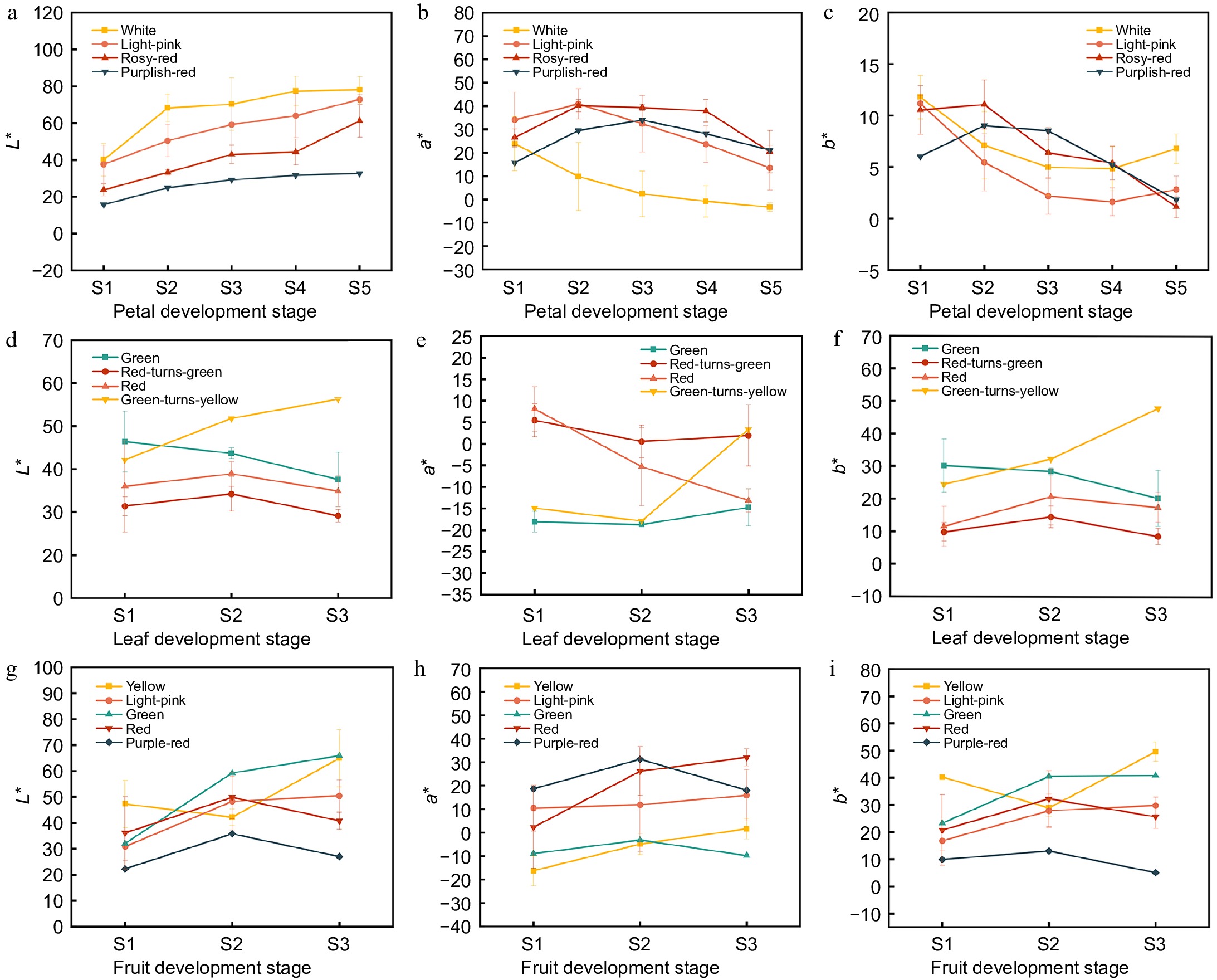

Figure 2.

Color indicator analysis of crabapple development stages. (a) L* values of petals, (b) a* values of petals, (c) b* values of petals, (d) L* values of leaves, (e) a* values of leaves, (f) b* values of leaves, (g) L* values of fruits, (h) a* values of fruits, (i) b* values of fruits.

The color changes in the petals, leaves, and fruits of 13 crabapple cultivars during development were digitally described using the CIE Lab color system (Fig. 2). All L* values showed an increasing trend during petal development. Among these, the white-line exhibited the highest L* values, while the purplish-red-line had the lowest, consistent with the observed changes in flower color. In addition, the a* value of the white crabapple decreased, whereas the a* values of petals in other color lines initially increased before decreasing. As the flowers developed, the b* values for crabapples in different color lines showed varying degrees of decrease. During leaf development, the green-to-yellow-line had the highest L* value, while the red leaf had the lowest. The a* values of the red-to-green-line decreased significantly during development, transitioning from a positive value in spring to a negative value at maturity. The a* and b* values of the green-to-yellow-line increased significantly as the leaves turned yellow in the fall, while the trend of b* changes in other color lines was relatively smooth. During fruit development, the green and yellow-lines exhibited the highest L* values, whereas the purple color line was the lowest. The a* values were significantly higher in the red and purple-lines compared to the yellow and green-lines. Fruits of the yellow-line had the highest b* values during the S3 period, significantly surpassing the other color lines, while the purplish-red-line maintained lower b* values throughout development.

Analysis of chlorophyll, carotenoid, and total anthocyanin content

-

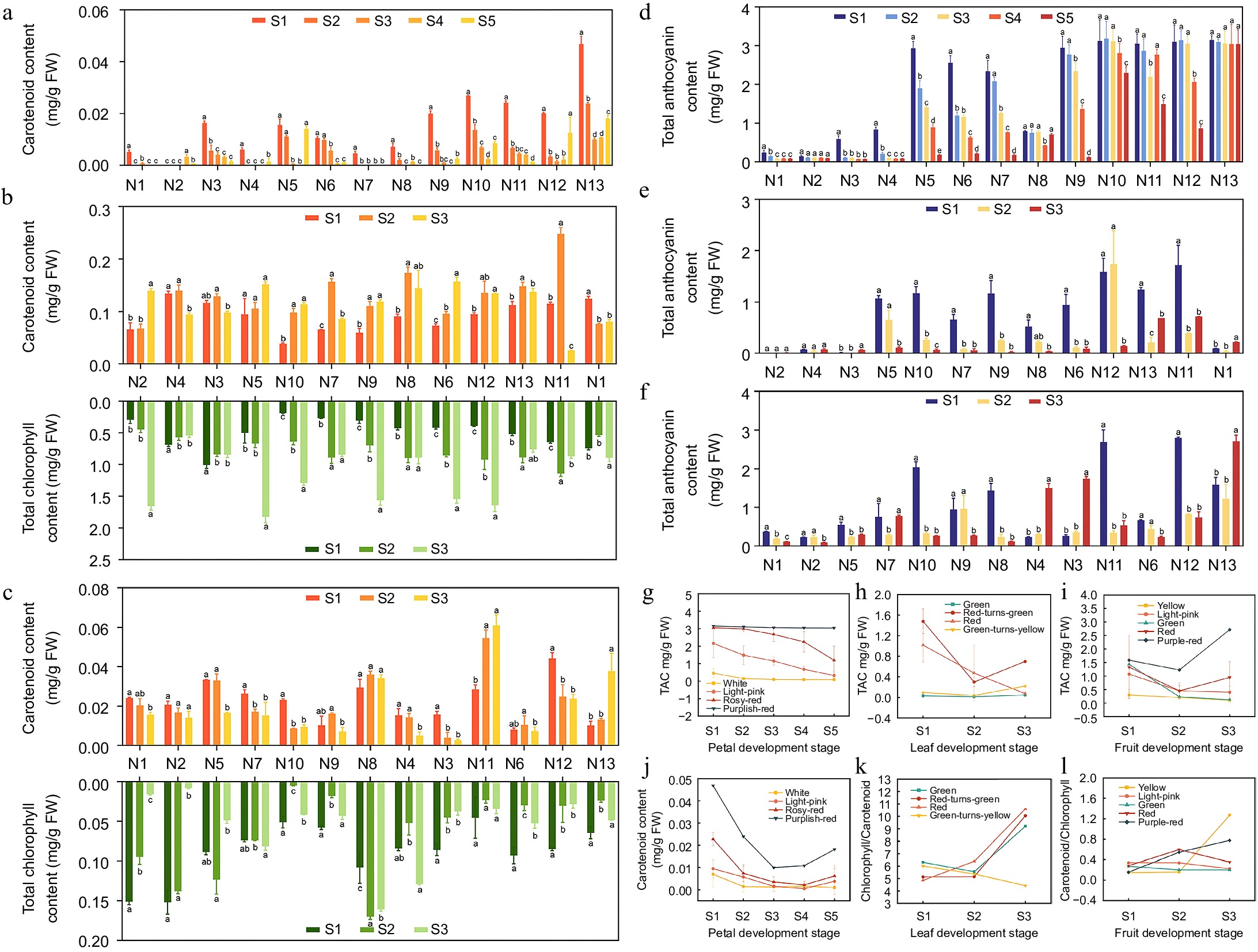

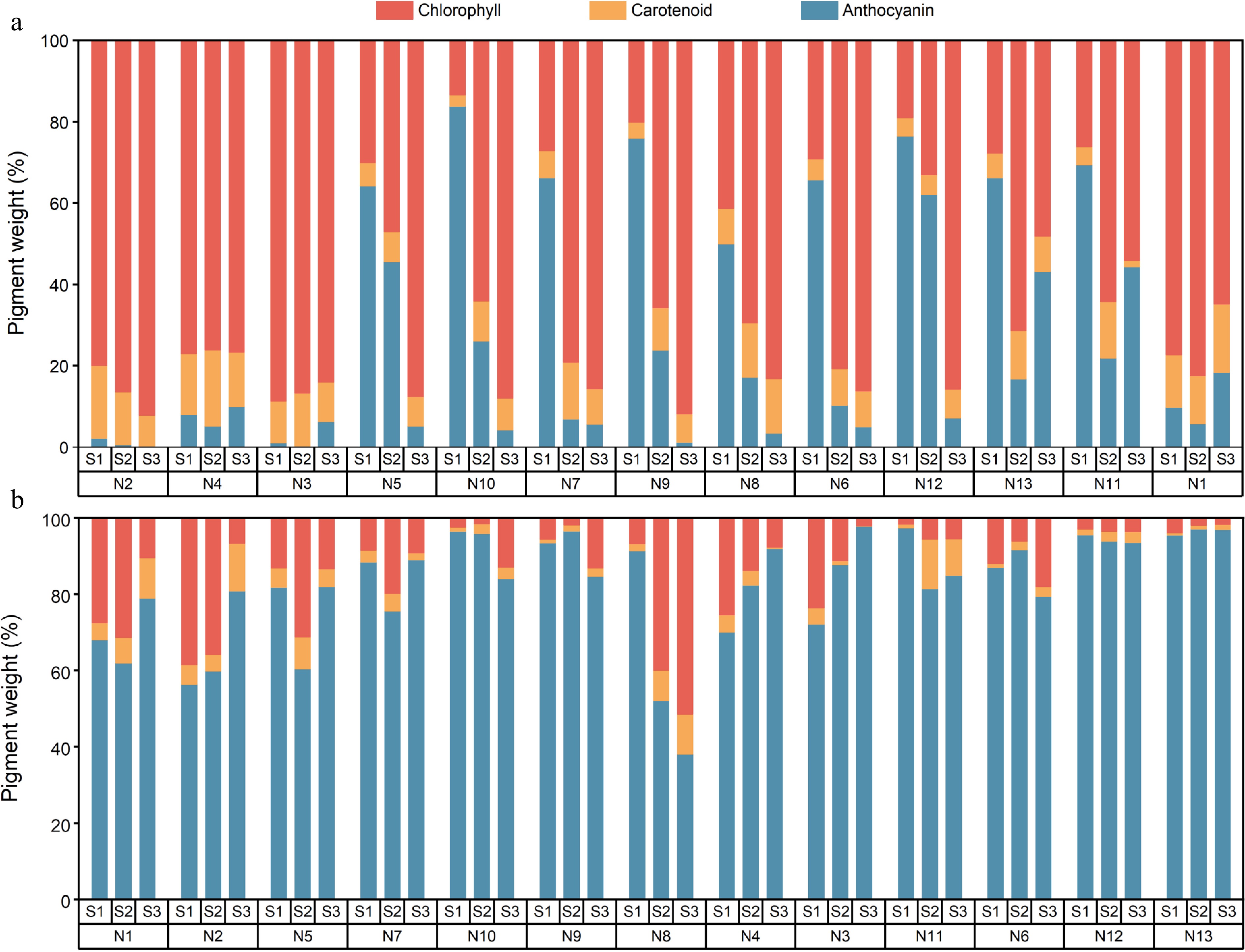

The chlorophyll and carotenoid contents of crabapple petals, leaves, and fruits were measured and analyzed to determine their ratios across different color lines and developmental stages (Fig. 3). The results indicated that the carotenoid content in crabapple petals was lower during the flower development stage, with significant differences among color lines and stages. Specifically, M. 'Royalty' had the highest carotenoid content, ranging from 0.010 to 0.047 mg/g FW, significantly surpassing that of other color lines, while the white-line exhibited the lowest content. Carotenoid levels generally decreased as petals developed, which was consistent with changes in flower color. In leaves, the chlorophyll content varied across the green, red-turns-green, and red-lines, showing different degrees of accumulation during development, while the chlorophyll to carotenoid ratio increased. In contrast, this ratio in the green-to-yellow-line gradually declined with leaf development, becoming significantly lower than in other color lines during the S3 period. During fruit development, the carotenoid to chlorophyll ratio in yellow crabapples increased gradually, peaking in the S3 period and being significantly higher than in other color lines. The green color line had the lowest ratio.

Figure 3.

Content of carotenoid, chlorophyll and anthocyanin in crabapple at different development stages. (a) Carotenoid content of petals. (b) Carotenoid and total chlorophyll of leaves. (c) Carotenoid and total chlorophyll of fruits. (d) Total Anthocyanin Content (TAC) of petals. (e) TAC of leaves. (f) TAC of fruits. (g) TAC trends of petals. (h) TAC trends of leaves. (i) TAC trends of fruits. (j) Carotenoid trends of petals. (k) Carotenoid trends of leaves. (l) Carotenoid trends of petals. Significance markers (a, b, c) in the figure represent the result of pairwise comparisons using the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test at a significance level of p = 0.05.

The TAC in petals, leaves, and fruits of 13 crabapple cultivars was determined, revealing significant differences among distinct color groups and developmental stages. During flower development, the TAC in the petals of M. 'Royalty' was the highest, consistently exceeding 3.039 mg/g FW throughout all developmental stages. The rosy-red, light-pink, and white crabapple petals exhibited a gradual decrease in TAC as the flowers matured. The TAC in the petals of the white-line was the lowest, significantly lower than that of other color lines, such as M. 'Huangzhenzhu', which ranged from 0.090 to 0.241 mg/g FW. In leaf development, the TAC of red-line crabapple leaves was the highest, although it fluctuated considerably. For instance, M. 'Shotizam' showed TAC values ranging from 0.389 to 1.719 mg/g FW. The fluctuation in TAC was caused by the fact that red crabapples are more sensitive to environmental factors such as light and temperature, leading to varying degrees of antigreening. As the leaves developed, the red-turns-green-line crabapple exhibited a significant downward trend in TAC, containing only a small amount of anthocyanins during the S3 period. In contrast, the TAC of the green and green-turns-yellow-line crabapples remained low throughout leaf development. During fruit development, M. 'Royalty' had the highest TAC, ranging from 1.227 to 2.717 mg/g FW. The TAC in yellow fruits remained low at all developmental stages. M. 'Brandywine' showed the highest TAC during the S1 period, but it decreased significantly as the fruit developed, changing color from red to green; by the S3 period, the content was only 0.125 mg/g FW.

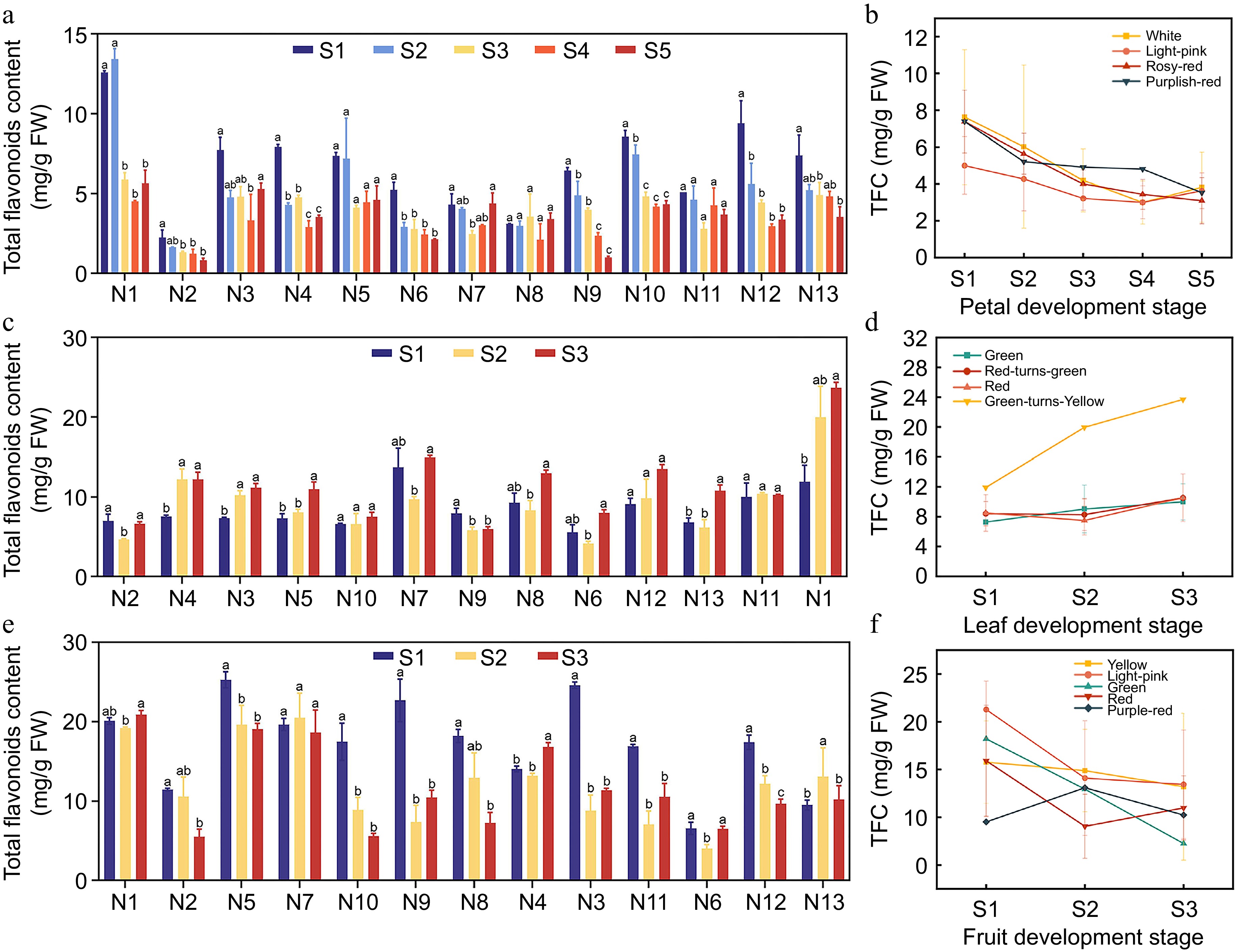

The analysis of pigmentation substances in crabapple revealed significant differences among cultivars (Fig. 4). Anthocyanins are the predominant pigments in crabapple petals, while carotenoids account for less than 4%. In the red-turns-green crabapple leaves, the S1 stage had the largest proportion of anthocyanins. As leaves turned green, anthocyanin levels decreased, and chlorophyll became the dominant pigment. In M. 'Huangzhenzhu', the proportion of carotenoids increased as the leaves turned yellow. Fruits exhibited the highest percentage of anthocyanins, exceeding 50% in all cultivars except M. 'Brandywine', with M. 'Royalty' having the highest percentage during fruit development, surpassing 90%. As fruits transitioned from green to yellow, carotenoid levels rose, while chlorophyll decreased. In contrast, as M. 'Brandywine' fruits changed from red to green, chlorophyll and carotenoids increased significantly, leading to a decrease in anthocyanins. The results indicate that the anthocyanin content is the primary reason for the red coloration of crabapple petals, leaves, and fruits, while variations in the proportions of anthocyanins, chlorophyll, and carotenoids can influence the color of crabapples.

Figure 4.

Content ratio of anthocyanin, chlorophyll, and carotenoid in crabapple. (a) Leaf, (b) fruit.

Analysis of TFC

-

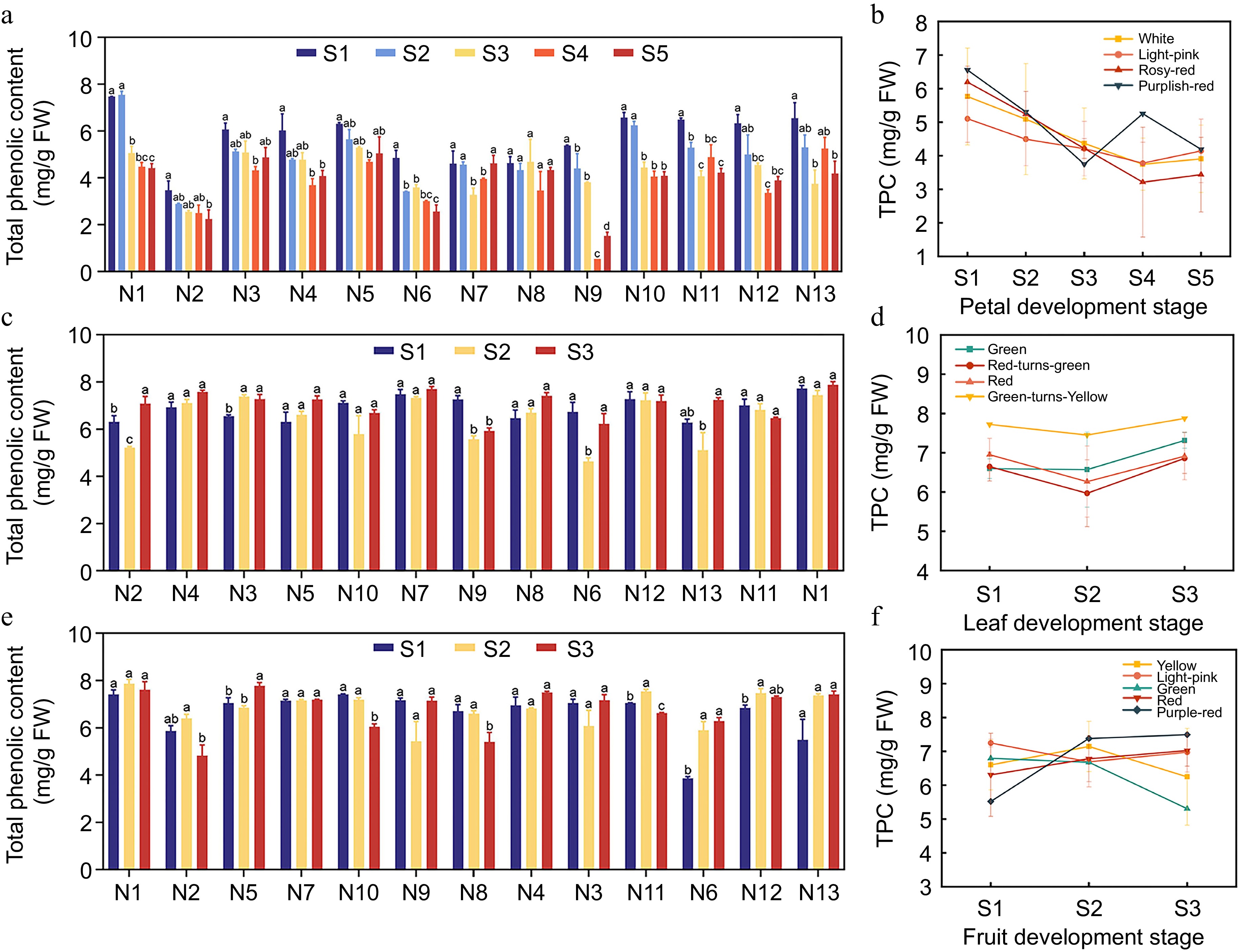

As crabapple flowers changed color, the TFC in petals gradually decreased (Fig. 5a). However, the differences among the various color lines were not significant. Among the 13 crabapple cultivars, Huangzhenzhu cv. had the highest TFC in petals during the S2 period, at 13.422 mg/g FW, while M. micromalus had the lowest TFC at the S5 period, with only 0.826 mg/g FW. During the leaf developmental stage, the TFC of Huangzhenzhu cv. showed a significant increasing trend, peaking at 23.695 mg/g FW in the S3 period (Fig. 5c). The TFC in the leaves of other color lines also showed a slight increase during the development stage, but the differences among the various lines were not significant. In fruit development, Huangzhenzhu cv. maintained a high TFC, reaching a maximum of 20.888 mg/g FW in the S3 period (Fig. 5e). Except for Royalty cv. and Shengdanguo cv., the TFC of all other cultivars was lower than at S1 during the S3 period. These results indicate that Huangzhenzhu cv. is rich in total flavonoids, suggesting that TFC can serve as an indicator of the developmental stage of crabapple to some extent.

Figure 5.

Total Flavonoid Content (TFC) in different crabapple germplasm. (a) TFC in various petal development stages. (b) Trends of TFC in petal development. (c) TFC in different leaf development stages. (d) Trends of TFC in leaf development. (e) TFC in various fruit development stages. (f) Trends of TFC in fruit development. Significance markers (a, b, c) in the figure represent the result of pairwise comparisons using the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test at a significance level of p = 0.05.

Analysis of TPC

-

The determination of TPC in the petals, leaves, and fruits of 13 crabapple cultivars revealed that the highest TPC in petals occurred during the S1 of flower development, significantly exceeding that of the S5 (Fig. 6). In general, the TPC in most cultivars decreased gradually throughout flower development. During leaf development, most cultivars exhibited a trend of decreasing TPC initially, followed by an increase. Notably, the TPC of M. 'Huangzhenzhu' was slightly higher than that of the other cultivars. In the fruit development stage, M. 'Huangzhenzhu' displayed the lowest TPC at the S1, measuring 3.862 mg/g FW. Conversely, it had the highest TPC at the S2, reaching 7.884 mg/g FW. Overall, the results indicate that M. 'Huangzhenzhu' is rich in total polyphenols across its petals, leaves, and fruits. However, the differences in TPC among the various color lines were not significant.

Figure 6.

Total Poiyphenol Content (TPC) in different crabapple germplasm. (a) TPC in various petal development stages. (b) Trends of TPC in petal development. (c) TPC in different leaf development stages. (d) Trends of TPC in leaf development. (e) TPC in various fruit development stages. (f) Trends of TPC in fruit development. Significance markers (a, b, c) in the figure represent the result of pairwise comparisons using the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test at a significance level of p = 0.05.

Analysis of phenolic metabolites

-

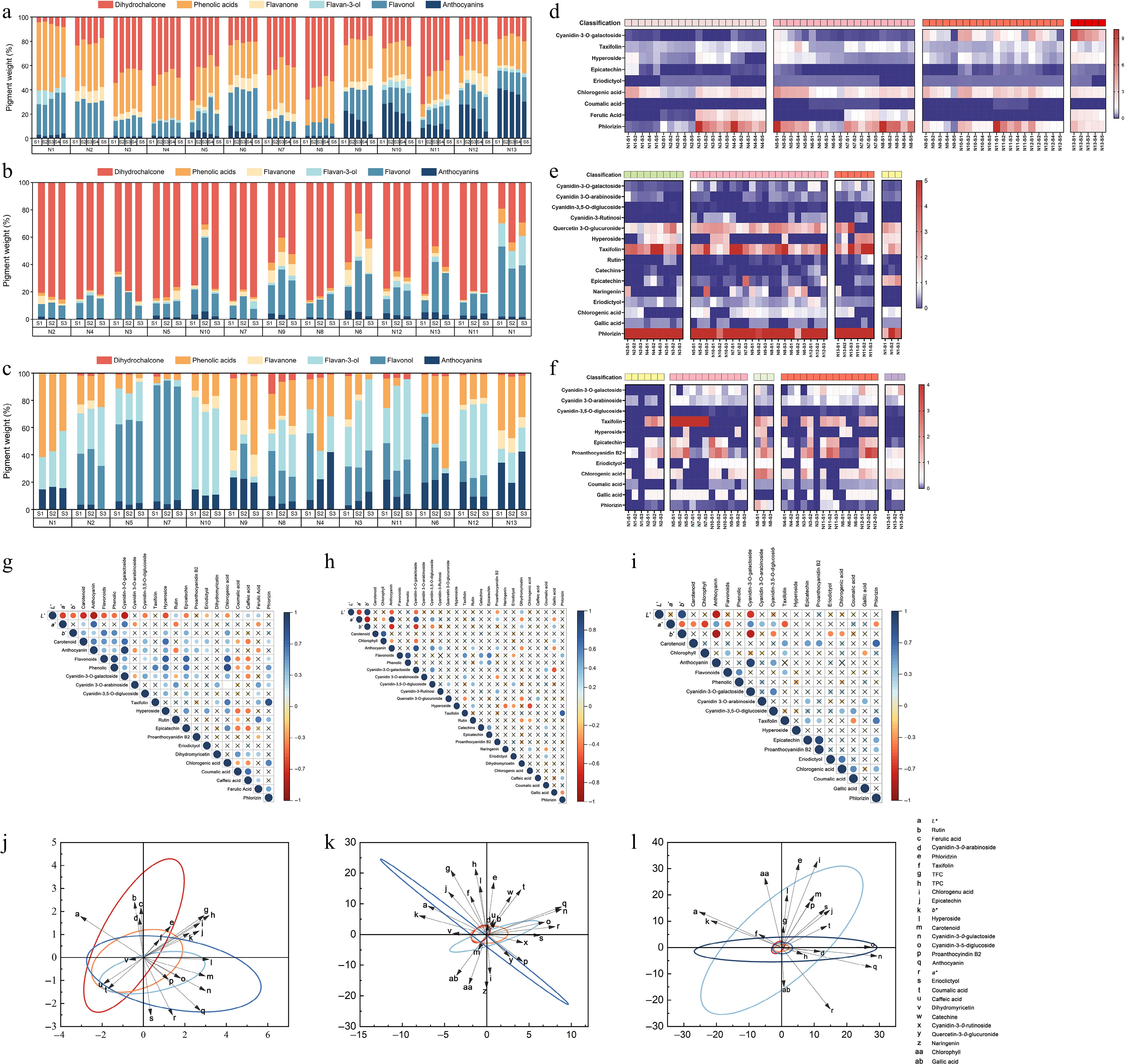

Phenolics in the petals, leaves, and fruits of 13 crabapple germplasm were separated and quantified using HPLC-DAD. A total of 20 phenolic compounds of six classes were analyzed and identified (Fig. 7). These included anthocyanins, flavonols, flavanols, flavanones, phenolic acids, and dihydrochalcone.

Figure 7.

Correlation analysis of phenol content and pigment content in crabapple. (a) Proportion of phenolic substances in petal. (b) Proportion of phenolic substances in leaf. (c) Proportion of phenolic substances in fruit. (d) Phenolic substances in petal development. (e) Phenolic substances in leaf development. (f) Phenolic substances in fruit development. (g) Petals correlation analysis. (h) Leaves correlation analysis. (i) Fruits correlation analysis. (j) Petals PCA. (k) Leaves PCA. (l) Fruits PCA.

Cyanidin-3-O-galactoside, cyanidin-3-O-arabinoside, and cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside were detected in the petals, leaves, and fruits of crabapple. Among these, cyanidin-3-O-galactoside was the primary anthocyanin substance in the petals, leaves, and fruits of crabapple. Its content varied significantly across different color lines. In M. 'Royalty' petals, the cyanidin-3-O-galactoside content was notably higher, ranging from 2.757 to 8.313 mg/g. In contrast, cyanidin-3-O-galactoside content was much lower in the white crabapple petals. The red-line crabapple leaves cyanidin-3-O-galactoside content during development, ranging from 0.500−0.946 mg/g. When the leaves of crabapple turned from red to green, the content of cyanidin-3-O-galactoside decreased significantly. Among the fruits, the purplish-red-line of M. 'Royalty' exhibited the highest cyanidin-3-O-galactoside content, maintaining a high level throughout development, ranging from 0.410 to 1.590 mg/g. In contrast, the green-line of M. 'Brandywine' had a relatively low cyanidin-3-O-galactoside content during the S3 stage, at only 0.105 mg/g. While cyanidin-3-O-arabinoside, cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside, and cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside were detected in some samples, the concentrations of these compounds did not change with development or color transitions. These results suggest that cyanidin-3-O-galactoside is the main color-presenting substance in crabapple.

Many flavonol compounds, including taxifolin, hyperoside, and rutin, were detected in the petals, leaves, and fruits of crabapple. Additionally, quercetin-3-O-glucuronide was found in the leaves. Rutin was the least abundant and was detected in only a few samples. In the petals, the contents of taxifolin and hyperoside gradually decreased during flower development in most germplasm, with no significant differences observed between the different color lines. In the leaves, quercetin-3-O-glucuronide and hyperoside exhibited similar trends, while taxifolin levels steadily increased during leaf development. In the fruits, hyperoside and taxifolin were detected in only some samples, with the highest concentration of taxifolin found in the fruits of M. halliana, ranging from 7.546 to 10.424 mg/g.

Flavanols in crabapple petals, leaves, and fruits also include catechins, epicatechins, and proanthocyanin B2. Of these, catechins were detected only in the leaves. In the petals, the content of epicatechins was significantly lower during the S5 period compared to the S1 period. M. 'Royalty' exhibited the highest epicatechin content of 0.457 mg/g in the S1 period. Proanthocyanin B2 was detected only in M. 'Radiant'. In the leaves, the content of epicatechins was higher, while catechin content was the lowest. The highest epicatechin content of 2.835 mg/g was found in M. 'Huangzhenzhu' during the S3 period. Both epicatechin and proanthocyanin B2 were detected in most crabapple fruits. The content of epicatechin was lower in the ripening stage compared to the young fruit stage, while proanthocyanin B2 generally showed a pattern of increasing and then decreasing during development.

Eriodictyol and dihydromyricetin were the flavanones detected in the petals at low concentrations. No significant differences in the content of eriodictyol were observed among the different color lines and developmental stages. In contrast, dihydromyricetin was detected only at low levels in the petals of M. 'Guifeihong', M. 'Sparkler', and M. halliana. The three flavanones detected in the leaves of crabapple include naringenin, eriodictyol, and dihydromyricetin. Of these, dihydromyricetin was present only in M. micromalus. Additionally, only one flavanone, eriodictyol, was detected in the fruit, with its concentration showing little variation across cultivars and developmental stages.

Crabapple petals, leaves, and fruits are rich in phenolic acids. A total of five types of phenolic acids were detected, including chlorogenic acid, coumalic acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, and gallic acid. Among these, chlorogenic acid was the predominant phenolic acid, exhibiting the highest concentration. In petals, the concentration of chlorogenic acid decreased gradually as the flowers developed. Among the 13 crabapple cultivars, M. 'Strawberry Parfait' exhibited the highest chlorogenic acid content during the S1 period, with a value of 5.492 mg/g. Coumalic acid, caffeic acid, and ferulic acid were detected only in a limited number of species. In most crabapple cultivars, chlorogenic acid content increased with leaf development. In contrast, the chlorogenic acid content in fruits decreased over time, with M. 'Brandywine' showing the highest levels, ranging from 1.612 to 2.638 mg/g. Changes in the concentrations of coumalic acid, caffeic acid, and gallic acid were not significant in the flowers, leaves, or fruits of the crabapple species studied.

In addition to the substances mentioned above, a substantial amount of phloridzin was detected using HPLC-DAD. The phloridzin content decreased significantly as petals developed. Among the cultivars, M. 'Strawberry Parfait' exhibited the highest phloridzin content during the S1 stage of petal development, measuring 23.745 mg/g. The phloridzin content in the leaves of different crabapple cultivars varied significantly. Notably, M. 'Guifeihong' had a higher phloridzin content during the S3 stage, ranging from 14.243 to 56.999 mg/g, whereas M. 'Huangzhenzhu' exhibited a lower content, ranging from 2.148 to 7.919 mg/g. The phloridzin content in most of the fruits decreased progressively with development; however, it remained significantly lower than that in the crabapple petals and leaves.

The phenolic substance content in the petals, leaves, and fruits of crabapple was further analyzed (Fig. 7). The results revealed significant differences in the phenolic content across different color lines. In the petals, the highest percentage of anthocyanins was found in the purplish-red color of crabapple, followed by the rosy-red and light-red, with the lowest percentage observed in the white. Additionally, the anthocyanin content decreased gradually as the flowers developed. The proportion of flavonols was relatively high in the white crabapple petals, while the percentages of flavanones and flavonols were comparatively lower. Except for M. 'Royalty', phenolic acids and phloridzin made up a large proportion of the petals, with their combined percentage exceeding 50%, making them the predominant phenolic substances. In the leaves, the percentage of anthocyanins remained relatively stable in the red-line, while in the red-turns-green-line, the anthocyanin content decreased as the leaves transitioned to green. The leaves of M. 'Huangzhenzhu' contained relatively high levels of phenolic acids, flavonols, and flavanols. In contrast, phloridzin was the main phenolic substance in the leaves of other lines. In the fruits, M. 'Royalty' exhibited the highest percentage of anthocyanins compared to other color lines. A significant increase in anthocyanin content was observed when M. 'Guifeihong' and M. 'Shengdanguo' fruits transitioned from green to red. Similarly, the proportion of flavanols increased when the fruits of M. 'Huangzhenzhu' and M. micromalus changed from green to yellow. While the proportions of phloridzin and flavanones were relatively low, the combined percentages of phenolic acids, flavonols, and flavanols exceeded 60%, making them the predominant phenolic substances in the fruits.

Correlation analysis

-

To further investigate the factors influencing the coloration of flowers, leaves, and fruits, a correlation analysis was performed between color values and pigment contents (Fig. 7). The results indicated that L*, which characterizes the degree of petal brightness, was significantly negatively correlated with a*, b*, carotenoids, total anthocyanins, total flavonoids, total polyphenols, cyanidin-3-O-galactoside, cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside, and hyperoside, with the strongest correlation observed with total anthocyanins (−0.83, p < 0.001). The a* values were significantly and positively correlated with total anthocyanins, cyanidin-3-O-galactoside, and eriodictyol. Total anthocyanins showed significant positive correlations with total flavonoids, total polyphenols, cyanidin-3-O-galactoside, cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside, hyperoside, procyanidin B2, and eriodictyol, with the highest correlation found with cyanidin-3-O-galactoside at 0.74 (p < 0.001). In leaves, L* was significantly positively correlated with b* (0.93, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with a*, total anthocyanins, cyanidin-3-O-galactoside, and procyanidin B2, with the highest correlation with a* (0.64, p < 0.001). The a* values were significantly and positively correlated with total anthocyanins, cyanidin-3-O-galactoside, and cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside. Chlorophyll content was significantly and positively correlated with carotenoids. Total anthocyanins also showed significant positive correlations with cyanidin-3-O-galactoside, cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside, and cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside. In fruits, L* values were significantly positively correlated with b* (0.86, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with total anthocyanins and cyanidin-3-O-galactoside. The a* values were significantly positively correlated with total anthocyanins, cyanidin-3-O-galactoside, cyanidin-3-O-arabinoside, and cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside with the highest correlation observed with cyanidin-3-O-galactoside (0.54, p < 0.001). Total anthocyanins content showed a significant positive correlation with cyanidin-3-O-galactoside and cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside, with the highest correlation found with cyanidin-3-O-galactoside (0.91, p < 0.001).

Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that the petals of the purplish-red group are concentrated in the fourth quadrant and are strongly associated with anthocyanins and specific phenolic compounds, suggesting that these pigments play a key role in the coloration of crabapple petals (Fig. 7). The dataset for red-turns-green crabapple resembles that of green crabapple but is slightly skewed toward the first quadrant, implying that even low levels of anthocyanins contribute to the red coloration of the leaves. The coloring substances in M. 'Huangzhenzhu' are predominantly carotenoids, with anthocyanins and other phenolic compounds exerting only a minor influence on its coloration. The fruits of M. 'Brandywine' contain higher levels of chlorophyll and carotenoids compared to other color groups. This distribution indicates that chlorophyll is the main pigment substance influencing the green color of the fruits.

-

Crabapples exhibit a wide range of flower, leaf, and fruit colors, making them valuable ornamental species in gardening. In this study, the pigment composition and content of crabapple were determined and analyzed. The results showed that the color change was mainly regulated by anthocyanins, chlorophyll, and carotenoids. Anthocyanin is the main chromogenic substance in petals, and the purple-red-line has higher anthocyanin and carotenoid than the white-line. In the process of petal development, the L* value of each color line showed an upward trend, and there was a significant negative correlation between the L* value and anthocyanins and carotenoids, indicating that with the maturity of flowers, the petals became brighter and the pigments gradually degraded. Similar findings have been reported in studies on flower color in Lilium[24], Rosa hybrida[15], Hibiscus syriacus[31], and Chimonanthus praecox[32]. In the leaves of crabapple, red-line has higher anthocyanin content than other color varieties. With the leaves turning green, anthocyanin content decreased significantly, while chlorophyll and carotenoid content increased, and chlorophyll became the main pigment. This is consistent with the research results of Wallibai et al.[25]. In autumn, the color of leaves turns yellow, and the ratio of carotenoid to chlorophyll in leaves increases. Similarly, the same results were obtained in the study of yellow-leafed plants such as Ginkgo biloba[33], Koelreuteria paniculata[34], and Plantycladus orientalis[35]. Further correlation analysis showed that anthocyanin content was positively correlated with a* value, indicating that the higher anthocyanin content, the deeper the red degree. There is a significant positive correlation between chlorophyll and carotenoids, which reflects their synergistic function in photosynthesis. Altering the ratio of chlorophyll and carotenoids promotes a change in peel color from green to yellow in Pyrus spp.[36], Mangifera indica[37], and Citrus sinensis[38]. The peel of M. pumila[39], Vitis vinifera[40], and Punica granatum[41] show a red or purple color when ripening due to the abundance of anthocyanin. In this study, anthocyanins were the predominant pigments in all color lines of crabapple fruits except for the green-line. In yellow fruits, the percentage of carotenoids increased significantly. During the transition from red to green, chlorophyll and carotenoids accumulated progressively, while the total anthocyanin content decreased significantly.

Crabapple is rich in phenolic compounds. Among them, cyanidin -3-O-galactoside is the main anthocyanin in petals, leaves, and fruits. The change trend of its content is positively correlated with a* value, which indicates that the substance plays a key role in the color development of red-line, which is consistent with the report of Han MeiLing[42]. In petals, the content of total anthocyanin was positively correlated with hyperoside and eriodictyol. At the same time, the proportion of flavonols and flavanols in white-line petals is relatively high, which indicates that these substances have synergistic effects in petal color formation. A high proportion of flavanols and flavanones were also detected in yellow leaves and fruits, which further indicated that flavonols and flavanols, as co-pigments of anthocyanins, participated in the coloration. Similar results were also obtained in studies on Fragaria × ananassa[43], Vitis vinifera[44], M. pumila[45], and Alpinia oblongifolia[46].

In addition, other phenolic compounds were detected in crabapple. These include phloridzin, chlorogenic acid, hyperoside, taxifolin, quercetin-3-O-glucuronide, epicatechin, and catechin. Among these, phloridzin was particularly abundant, especially in the leaves. The phloridzin content of M. halliana during leaf development can reach 66.764 mg/g. Phlorizin has many important medical and health functions, such as lowering blood sugar, improving memory, resisting oxidation, and cancer, and has a wide application prospect in the development of new pharmaceuticals and natural health food[47−49]. Meanwhile, chlorogenic acid was detected in crabapple petals, leaves, and fruits. Chlorogenic acid is an important phenolic acid in plants with various functions such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-apoptosis, which is widely used in clinical medicine[50]. A large amount of quercetin-3-O-glucuronide was also detected in crabapple leaves, but the content was low or not detected in petals and fruits. This indicates that the accumulation of the substance content is tissue-differentiated in crabapple. In Rosa hybrida petals, flavonols are primarily composed of quercetin derivatives, with quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside and quercetin-7-O-rhamnoside being the dominant types[51]. Several studies have demonstrated that quercetin and its derivatives have strong physiological activities such as antioxidant activity, anticancer, antiaging, and prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases[52,53]. Similarly, other phenolics such as hyperoside, taxifolin, and epicatechin have antibacterial, antiviral, and other health functions[54].

-

In this study, the pigment composition and content of flowers, leaves, and fruits of different cultivars of crabapple were determined and analyzed, and the key factors of crabapple coloring were revealed. The results show that anthocyanins, chlorophyll, and carotenoids are the key pigments for the color of flowers, leaves, and fruits of crabapple. HPLC-DAD analysis showed that there were six phenolic compounds in crabapple, including anthocyanins, flavonols, flavanols, flavanones, phenolic acids, and dihydrochalcone. Among them, cyanidin-3-O-galactoside is the main anthocyanin, and it is the main substance that gives red to crabapple. Anthocyanin content is high in dark-colored cultivars, flavonols, and flavanols, as co-pigments, play an auxiliary role in color development. In addition, the study also detected that there are a lot of other phenolic compounds in crabapple, such as phlorizin, chlorogenic acid, hyperoside, taxifolin, quercetin-3-O-glucuronide, epicatechin, and catechin, which are not only related to color development, but also have potential antioxidant activity. This study reveals the reasons for the coloration of crabapples of different color lines and provides scientific references for accelerating the selection of good cultivars and enriching the application of garden plants. It also provides a basis for a deeper understanding of the potential of crabapple as a source of natural antioxidants.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171862), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32471951), and by the Chinese Universities Scientific Fund (2452023085).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: all authors contributed to the study conception and design; materials preparation: An H, Duan Y, Liu S, Li H; data collection and analysis: An H, Duan Y, Xu Y, Qian C, Wang Y; writing first draft of the manuscript: An H; all authors commented on draft manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files, further requires are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Hong An, Yu Duan

- Supplementary Table S1 The standard curve for phenolic compound contents.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

An H, Duan Y, Liu S, Xu Y, Qian C, et al. 2025. Analysis of pigment composition and color dynamics of crabapple. Ornamental Plant Research 5: e029 doi: 10.48130/opr-0025-0025

Analysis of pigment composition and color dynamics of crabapple

- Received: 30 November 2024

- Revised: 16 March 2025

- Accepted: 30 April 2025

- Published online: 22 July 2025

Abstract: Crabapple is an important ornamental tree species. This study analyzed 13 crabapple cultivars, examining pigment composition and content across different stages of development. According to the phenotypic and CIE Lab color system, different crabapple cultivars were clustered and analyzed, and the flower, leaf, and fruit colors of crabapple were divided into different lines. High performance liquid chromatography coupled with a diode array detector (HPLC-DAD) analysis showed that cyanidin-3-O-galactoside was the main anthocyanin in crabapple, with higher levels in the deep-red-line variety. Additionally, the petals of the purplish-red-line crabapple were found to contain higher levels of anthocyanins and carotenoids. The red-line leaves of crabapple exhibit high anthocyanin content, which gradually decreases as the leaves turn green. The ratio of carotenoids to chlorophyll was relatively high in yellow leaves. In fruits, the red-line crabapple exhibits the highest percentage of anthocyanins, which are the primary pigment substances. As the fruit changed from red to green, chlorophyll and carotenoids gradually accumulated, while anthocyanin content decreased. In yellow-line fruits, the percentage of carotenoids was relatively high. The results indicated that the color change in crabapple was driven by shifts in the relative proportions of these three pigments. Particularly, the ratio of flavonols was relatively high in the white-line crabapple petals. The ratio of flavanols to flavanones was higher in yellow leaves and fruits. This suggests that flavonols and flavanols act as co-pigments of anthocyanins, enhancing color presentation. Furthermore, crabapple is rich in phenolic compounds, including phloridzin, chlorogenic acid, hyperoside, taxifolin, and epicatechin.

-

Key words:

- Crabapple /

- Anthocyanins /

- Chlorophyll /

- Carotenoids /

- Phenolic /

- Coloration