-

Auricularia cornea Ehrenb., a member of Basidiomycota[1], was previously cultivated and reported as A. polytricha (Mont.) Sacc. in almost all related Chinese reports until 2015[2−8]. It is widely distributed in Africa, Asia, Europe, North and South America[9]. This fungus is very important due to its edible value and medicinal properties[10−13]. Auricularia cornea is recognized as one of the seven principal cultivated edible and medicinal mushrooms in China[14−16]. In 2021, China's output of cultivated Auricularia accounted for over 90% of global production, with A. cornea being a predominant cultivated species within the genus[17,18]. The industrial production of edible mushrooms necessitates the establishment of optimal substrate and growth conditions for specific fungal strains[19−22]. These conditions encompass variations in temperature, and pH levels, as well as sources of carbon and nitrogen[23,24]. For example, optimal temperature and nitrogen source selection enhance microbial growth rates and product yields[25]. Furthermore, it is essential to recognize that not only do different fungal strains require distinct cultural conditions, but also that various strains of the same species may exhibit divergent requirements[26,27]. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct an in-depth study on screening optimal solid substrate conditions, which will provide a foundational understanding for the cultivation protocols of A. cornea.

Edible and medicinal mushrooms have high research and commercial value for the biological activity of metabolites rich in high-quality carbohydrates, minerals, proteins, and dietary fiber[28−32]. The pharmacological research showed the diverse pharmacological properties of A. cornea, encompassing its anti-oxidation and anti-inflammation[33−35], antitumor effects, hypolipidemic actions, and analgesic properties[36,37]. This study primarily measured crude polysaccharide, crude fiber, crude fat, and ash. The common amino acid evaluation models comprise four types: the EAO model, the whole egg model, the human milk model, and the FAO/WHO model, among which the FAO/WHO model is the most frequently utilized[38]. So, in this study, we use the FAO/WHO model for evaluation.

Nutritional analysis is key for optimizing mycelium growth. When optimizing mycelium cultivation, selecting proper culture medium and culture conditions like temperature and pH is crucial, as nutritional components directly impact mycelium growth. For example, Anike et al.[39] optimized Lentinus squarrosulus mycelial biomass and exopolysaccharide yield by studying liquid culture conditions and medium composition. Chen[40] studied how different carbon sources, nitrogen sources, and inorganic salts, affect Se-enriched Ganoderma lucidum growth and used response surface analysis to find the optimal nutrient combination. In summary, nutritional analysis underpins the optimization of mycelium growth, and the effectiveness of mycelium growth optimization must be verified through nutritional analysis.

During investigations on macro-fungi in Qixianling National Forest Park of Hainan Province, China, a wild strain of A. cornea was collected and isolated. To evaluate the cultivation potential and nutritional value of this wild strain, the strain was studied in its biological characteristics, cultivation, and nutritional components from the cultured fruit bodies.

-

A wild strain of Auricularia was collected from Qixianling National Forest Park in Hainan (China). The specimen was deposited at the Fungarium of the Institute of Tropical Bioscience and Biotechnology, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences (FCATAS). The macromorphological descriptions were observed on field notes and photos captured in the field[9]. The micromorphological data were obtained from dried specimens observed under an Olympus IX73 inverted fluorescence microscope (Tokyo, Japan) with a 10 × 100 oil immersion objective. The strain stored at 4 °C was inoculated in PDA medium, and cultivated at 25 °C under dark conditions. The mycelium covered the entire surface of the medium for further testing.

Identification: sequencing and alignment of ITS sequences of A. cornea

-

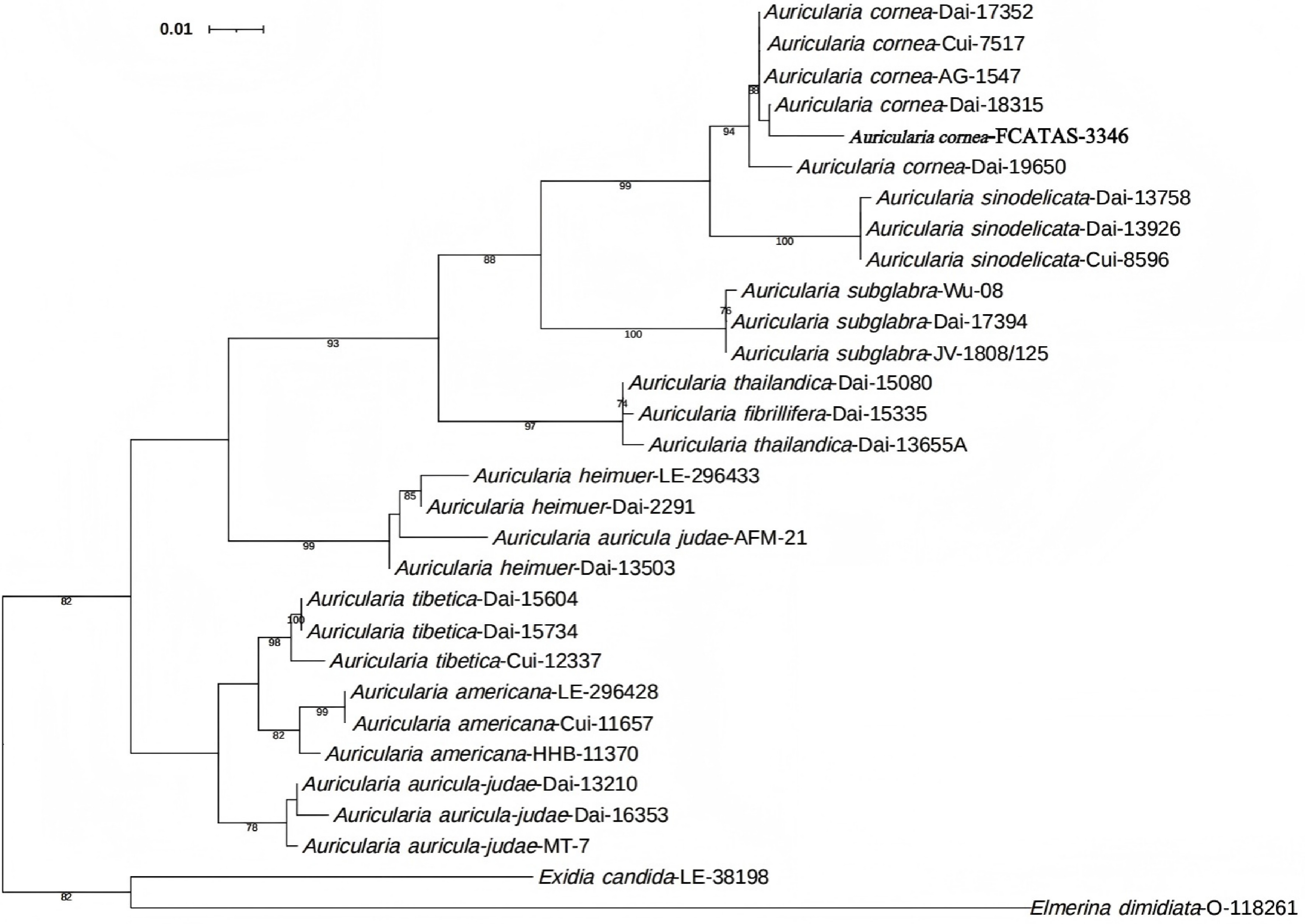

The preliminary identification of the specimen as A. cornea was conducted through morphological analysis of field-collected samples. For molecular verification, genomic DNA was extracted using the CTAB method, followed by amplification and sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region. The ITS primers and methods were selected in accordance with the study by Ma et al.[41]. A phylogenetic tree was subsequently constructed based on the obtained ITS sequences to ascertain its taxonomic position within the genus. The values of BS > 70% are indicated in the phylogenetic tree, and the self-tested sequences are all marked in bold[42].

Biological characteristics experiments of A. cornea

Experimental strain and medium

-

The strain was isolated and purified from the tissue of specimen FCATAS 3346 and stored in the Germplasm Bank of Hainan Tropical Edible and Medicinal Fungi. The PDA medium, carbon-free medium, and nitrogen-free medium were used as follows[41]:

PDA medium: potato (peeled) 200.0 g/L, agar powder 20.0 g/L, glucose 20.0 g/L, peptone 2.0 g/L, KH2PO4 3.0 g/L, MgSO4 1.5 g/L, pH neutral.

Carbon-free medium: agar powder 20.0 g/L, peptone 2.0 g/L, KH2PO4 3.0 g/L, MgSO4 1.5 g/L, pH natural.

Nitrogen-free medium: agar powder 20.0 g/L, glucose 20.0 g/L, KH2PO4 3.0 g/L, MgSO4 1.5 g/L, pH natural.

Single-factor experiment

-

Compared with carbon-free medium, 20 g of glucose, sucrose, starch, lactose, fructose, mannitol, and maltose were added as the carbon source, respectively. Each treatment of different carbon sources was carried out six times. The hyphae blocks (8 mm in diameter) from the activated strain taken using a punch with an inner diameter of 8 mm were inoculated in autoclaved medium, and cultivated at 25 °C under dark conditions. The colony diameter was measured by means of cross experiment, the mycelial growth rate and mycelial growth vigor of the strain were recorded and observed with the first strains completing the Petri dish colonization, following the method of Wang et al.[43].

Compared with nitrogen-free medium, 2 g of peptone, yeast extract powder, urea, ammonium nitrate, sodium nitrate, ammonium chloride, and potassium nitrate were added as the nitrogen source, respectively. The methods of cultivation and measurement were the same as above.

The hyphae blocks (8 mm in diameter) from the activated strain were inoculated in autoclaved PDA medium, and cultivated at 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40 °C under dark conditions, respectively. The methods of observation and measurement were the same as above.

The hyphae blocks (8 mm in diameter) from the activated strain were inoculated in autoclaved PDA medium with pH 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, 9.0, and 10.0, and cultivated at 25 °C under dark conditions. The methods of observation and measurement were the same as above.

Orthogonal test

-

The top three in carbon sources, nitrogen sources, pH value, and temperature were selected from the single-factor experiment, and the optimal conditions for the mycelial growth of A. cornea were studied. The L9 (34) four-factor three-level orthogonal test was conducted following the method of Chen et al.[44].

Cultivation

-

Pre-culture spawn medium was composed of corn kernels 99% and gypsum 1%. The hyphae blocks from the activated strain were inoculated in autoclaved spawn medium in 250 mL culture bottles, and cultivated at 25 °C under dark conditions.

Based on previous study (not published), the spawn substrate was composed of 38% hardwood sawdust, 20% corncob, 20% bran, 10% cottonseed hull, 10% corn flour, 1% CaCO3, and 1% gypsum with 60% moisture capacity. The pre-culture spawn was inoculated in autoclaved polyethylene bags (8 cm in width × 10 cm in length × 20 cm in height), and cultivated at 25 °C under dark conditions. The mycelial growth rate and mycelial growth vigor were measured and recorded using the streaking method.

Nutritional analysis

-

The proximate components of the cultivated fruiting bodies, including crude polysaccharide, crude fat, crude fiber, ash, and amino acids, were determined. Crude polysaccharide was determined according to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia[45]. The crude fat was measured following the method of the National Food Safety Standard GB 5009.6-2016. The ash content was determined according to the National Food Safety Standard GB 5009.4-2016. The 17 amino acids (aspartic acid, threonine, serine, glutamic acid, proline, glycine, alanine, valine, methionine, isoleucine, leucine, tyrosine, phenylalanine, lysine, histidine, and arginine) were measured according to the method of GB5009.124-2016. The amino acid score (AAS) adopts the method proposed by Chang & Tricita[46].

$ {\text{AAS}}={\text A}_{\text x}/{\text A}_{\text s} \times 100{\text{%}} $ where, Ax represents the amino acid content of the tested protein; As represents the amino acid content of the WHO/FAO scoring model.

The chemical score (CS) employs the scoring method put forward by FAO[47].

$ {\mathrm{CS}}={\mathrm A}_{ \mathrm{x}} \mathrm{/A}_{ \mathrm{egg}} \times 100{\text{%}} $ where, Ax represents the content of a certain essential amino acid in the protein under test; Aegg is the content of the same amino acids in whole egg white pattern spectrum.

Statistical analysis

-

SPSS 27.01 statistical software was used for data analysis, Graphpad Prism 8.0 and Microsoft Excel software were used for plotting.

-

Basidiomata gelatinous when fresh, fawn to reddish brown, solitary, sessile or substipitate; pileus discoid, up to 9 cm wide and 1–2 mm thick; upper surface densely pilose, light grey-brown when drying; hymenophore surface smooth, buff-yellow when drying. Basidiospores 13.5–17 × 4.5–6 µm, allantoid, hyaline, smooth, thin-walled. It is morphologically similar to the A. cornea previously described by Wu et al.[9].

In the phylogenetic tree, the strain FCATAS 3346 is grouped in the clade of A. cornea with highly supported (Fig 1). Based on morphological observation and ITS sequence analyses, the strain was identified as A. cornea. Its genebank number is PV163959.

Biological characteristics of A. cornea

-

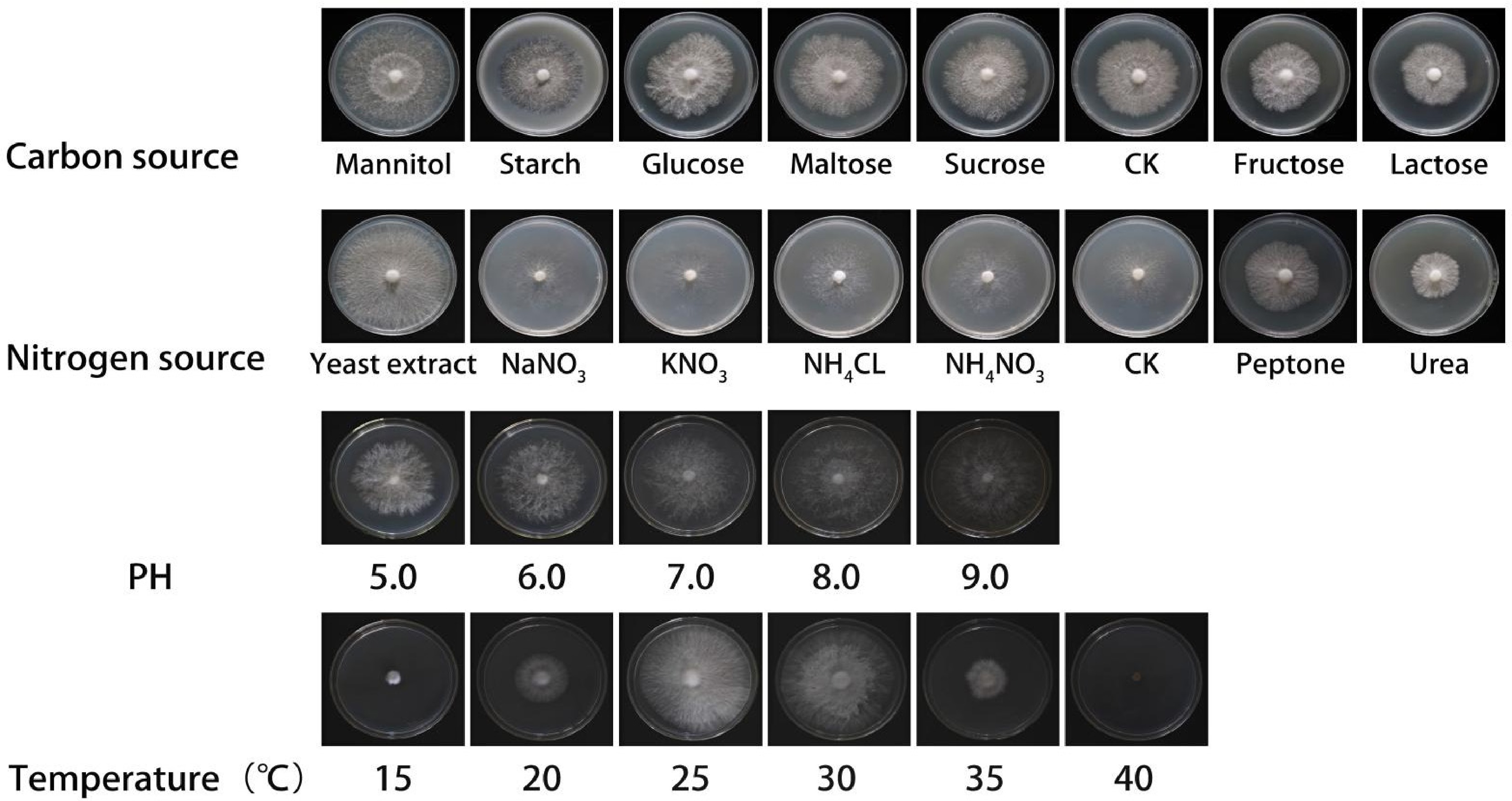

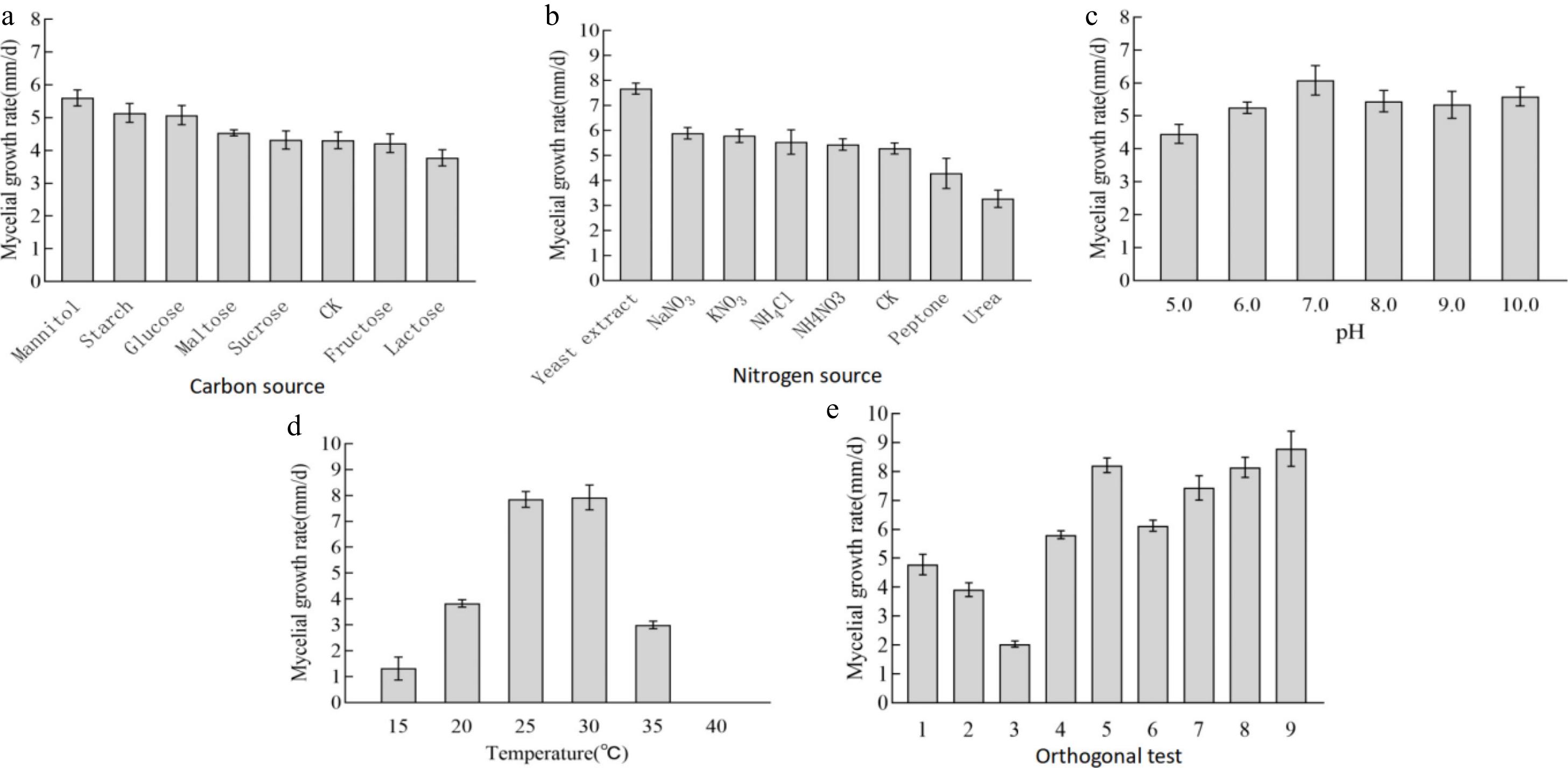

The mycelial growth rate demonstrated significant variation across different carbon sources (p < 0.05; Figs 2a, 3 & Table 1). Among the carbon sources tested, the mycelial growth rate was highest in mannitol (5.60 ± 0.10 mm/d), followed by starch, glucose, maltose, and sucrose. Compared to these, the mycelial growth rates in the control group, fructose, and lactose were lower. Consequently, mannitol was identified as the optimal carbon source for the mycelial growth of A. cornea.

Figure 2.

Mycelial growth rate under single factor and orthogonal conditions. (a) Carbon source; (b) nitrogen source; (c) pH; (d) temperature; (e) orthogonal test.

Table 1. Effects of different single factor conditions on mycelial growth.

Condition Factor Mycelial growth

rate (mm/d)Mycelial

growth vigorCarbon source Mannitol 5.60 ± 0.10 a ++++ Starch 5.14 ± 0.12 b +++ Glucose 5.08 ± 0.12 b +++ Maltose 4.54 ± 0.04 c +++ Sucrose 4.32 ± 0.11 c +++ CK 4.31 ± 0.10 c +++ Nitrogen source Fructose 4.22 ± 0.16 c +++ Lactose 3.78 ± 0.10 d ++ Yeast extract powder 7.68 ± 0.09 a ++++ NaNO3 5.89 ± 0.09 b +++ KNO3 5.78 ± 0.11 bc +++ NH4Cl 5.54 ± 0.20 bcd +++ NH4NO3 5.44 ± 0.09 cd +++ CK 5.28 ± 0.09 d +++ Peptone 4.28 ± 0.25 e +++ Urea 3.27 ± 0.14 f ++ pH 5.0 4.46 ± 0.12 c +++ 6.0 5.25 ± 0.07 b +++ 7.0 6.08 ± 0.18 a ++++ 8.0 5.45 ± 0.13 b +++ 9.0 5.34 ± 0.16 b +++ 10.0 5.59 ± 0.12 b +++ Temperature (°C) 15 1.32 ± 0.18 d + 20 3.83 ± 0.06 b ++ 25 7.85 ± 0.12 a +++ 30 7.93 ± 0.20 a ++++ 35 3.00 ± 0.06 c ++ 40 0 e − −, no growth; +, very weak growth; ++, weak growth; +++, vigorous growth; ++++, very vigorous growth. Different lowercase and uppercase letters in the same column represent significant differences (p < 0.05). The same below. In the nitrogen source experiment (Figs 2b, 3 & Table 1), yeast extract powder was the most effective in promoting mycelial growth of A. cornea, followed by sodium nitrate, potassium nitrate, ammonium chloride, ammonium nitrate, peptone, and urea. Among them, the mycelial growth vigor showed dense, white, and strong in organic nitrogen sources, but relatively sparse, and weak in inorganic nitrogen sources. In yeast extract medium, the mycelial growth rate is fastest, white, and dense. Therefore, yeast extract powder is selected as the most suitable nitrogen source for mycelial growth.

The growth rate of mycelium exhibited variations across different pH media (Figs 2c, 3 & Table 1), though the differences were not statistically significant. Specifically, the mycelial growth rate was highest at pH 7.0, followed by pH 10.0, and pH 8.0. The mycelial growth appeared dense and white, with no significant differences observed among the treatments. After a comprehensive evaluation, pH 7.0 was determined to be the optimal pH for mycelial growth.

The temperature tests indicated that the mycelium can grow on PDA medium from 15 to 35 °C (Figs 2d, 3 & Table 1), and the growth had almost ceased at 40 °C. Among them, under the temperature of 30 °C, the growth rate of mycelium is the fastest, and mycelia is very white, strong, and dense. However, when the temperature was lower than 20 °C, and higher than 35 °C, the mycelial growth rate was sharply reduced. Therefore, 30 °C is selected as the optimal temperature for the growth of the mycelium.

Based on the results of the single-factor tests (Tables 2, 3), a four-factor and three-level orthogonal test was conducted. The mycelium of the strain can grow under all sets of test conditions, but at different growth rates. Based on the calculated magnitude of the extreme difference R, the degree of influence of the four factors on the mycelium from high to low was temperature (4.540) > pH (2.267) > nitrogen source (1.100) > carbon source (0.460), in which the mean values of the temperature were in the descending order of K3 > K2 > K1, the carbon source in the descending order of K1 > K3 > K2, the nitrogen source in the descending order of K2 > K1 > K3, and the mean values of pH were ranked from large to small as K1 > K2 > K3. The optimal combination was mannitol 1.0 g/L, yeast extract powder 0.3 g/L, pH 7.0, and 30 °C. ANOVA analysis was performed on the above results, and all four factors had a highly significant effect on the growth of the mycelium (p < 0.01).

Table 2. Orthogonal test results of A. cornea.

Test no. Factor Mycelial growth rate (mm/d) Temperature

(°C)Mannitol

(g/L)Yeast extract

(g/L)pH 1 20 1.0 0.1 7.0 4.79 ± 0.14 e 2 20 3.0 0.3 8.0 3.91 ± 0.10 f 3 20 2.0 0.5 9.0 2.04 ± 0.05 g 4 25 3.0 0.1 9.0 5.81 ± 0.06 d 5 25 2.0 0.3 7.0 8.21 ± 0.10 b 6 25 1.0 0.5 8.0 6.13 ± 0.08 d 7 30 2.0 0.1 8.0 7.43 ± 0.17 c 8 30 1.0 0.3 9.0 8.14 ± 0.14 b 9 30 3.0 0.5 7.0 8.79 ± 0.25 a S1 10.74 19.06 18.03 22.79 S2 20.15 17.68 20.26 17.47 S3 24.36 18.51 16.96 15.99 K1 3.580 6.353 6.010 7.597 K2 6.717 5.893 6.753 5.823 K3 8.120 6.170 5.653 5.330 R 4.540 0.460 1.100 2.267 S: standard deviation; K: kurtosis; R: range. Different lowercase and uppercase letters in the same column represent significant differences (p < 0.05). Table 3. Variance analysis of orthogonal tests.

Source Type III sum

of squaresdf Mean square F value Significance Model 244.368 8 30.546 279.369 0 Intercept 2036.406 1 2036.406 18624.653 0 Temperature 194.793 2 97.396 890.773 0 Carbon source 11.496 2 5.748 52.57 0 Nitrogen source 1.931 2 0.965 8.83 0.001 pH 36.148 2 18.074 165.303 0 Error 4.92 45 0.109 Total 2285.694 54 Corrected total 249.288 53 Model coefficient of determination R2 = 0.980, adjusted coefficient of determination R2 = 0.977. Cultivation results

-

After 2–3 d, the mycelium began to germinate, and filled the colonization of corn kernels of the culture bottle in 9–10 d. The strain completed the colonization of the sawdust substrate of the polyethylene bag in 65–70 d, and presented an average daily growth rate of 0.28 ± 0.02 cm/d (M = 10) , and the mycelium grows white and dense. When the mycelium showed full colonization in the sawdust substrate cultivation bag, several circular pores were made over the surface of both sides of the cultivation bag (approximately 4 cm apart) under natural room temperature (24–30 °C), and a relative humidity of 85%–90%. After 7–14 d, primordia emerged from the pores on the bags, and high humidity was maintained by misting devices until the fruiting bodies matured (Fig. 4).

Nutritional composition analysis

-

The nutritional composition of the fruiting body produced is shown in Table 4. The main nutrient components (%) of the fruiting body were crude polysaccharide 2.93, crude fat 2.3, crude fiber 15.5, and ash 2.8. The amino acid components (%) of the fruiting body were total amino acids (TAA) 3.70, total essential amino acids (EAA) 1.34, and total medicinal amino acids (MAA) 1.56.

Table 4. Nutritional composition of A. cornea (%).

Ingredient FS3346 Ingredient FS3346 Phe 0.17 Ser 0.17 Met 0.03 Asp 0.46 Lys 0.12 His 0.08 Leu 0.32 EAA 1.34 Thr 0.23 NEAA 2.35 Val 0.29 TAA 3.7 Ile 0.18 MAA 1.56 Cys 0.02 UAA 1.63 Ala 0.42 SAA 1.35 Pro 0.36 BAA 1.36 Gly 0.05 Crude fat 2.3 Glu 0.41 Crude fiber 15.5 Arg 0.29 Ash 2.8 Tyr 0.09 Crude polysaccharides 2.93 EAA: essential amino acids; NEAA: non essential amino acids; TAA: total amino acids; MAA: medicinal amino acids; UAA: Umami amino acids; SAA: Sweet amino acids; BAA: Bitter amino acids. The chemical score takes the lowest amino acid as the chemical score of the protein and predicts the first limiting amino acid[48,49]. From Table 5, under the comparison of the two patterns, the restricted amino acids of the A. cornea are Met + Cys. In terms of amino acid scoring, the contents of Ile, Thr, and Val are higher than those in the FAO/WHO pattern, among which Thr is also higher than that in the whole egg pattern. The chemical score is lower than that of the whole egg white pattern spectrum.

Table 5. Comparison of amino acid scores of proteins and chemical scores of proteins in A. cornea.

Amino acid FAO/WHO

pattern spectrumWhole egg white

pattern spectrumAAS CS ILe 4% 6.6% 4.5% 2.72% Leu 7% 8.8% 4.57% 3.64% Lys 5.5% 6.4% 2.18% 1.87% Met + Cys 3.5% 5.5% 1.42% 0.91% Phe + Tyr 6% 10% 4.33% 2.60% Thr 4% 5.1% 5.75% 4.51% Val 5% 7.3% 5.8% 3.97% AAS: chemical score; CS: chemical score. -

There are about 1,020 species of edible mushrooms and 692 species of medicinal mushrooms that occur in China[50], and can be used as a natural source of food and medicine. However, there are only approximately 100 species that have been domesticated[51−53]. This study carried out isolation and identification on a wild strain of A. cornea, and evaluated the in vitro growth characteristics and nutritional components of mycelia and fruiting bodies, which could provide a theoretical basis for the development and utilization of the edible and medicinal fungi of Auricularia. Furthermore, optimizing mycelial growth conditions directly enhances the nutritional value of edible mushrooms. Systematic studies on nutrient and environmental effects, along with medium optimization, significantly boost yield and quality. This supports industry sustainability and provides healthier and safer food options[54−56]. The environmental factors and nutrient sources are regarded to be of utmost significance and influence on the mycelial growth and fruit-body formation. According to single-factor and orthogonal tests, the optimal culture conditions for the strain FCATAS 3346 of A. cornea were shown to be mannitol 1.0 g/L and yeast extract powder 0.3 g/L at pH 7.0 and 30 °C in the present study. Previous researchers have shown that A. cornea strains can effectively utilize broad carbon sources, including monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides, and different strains of A. cornea had different optimal carbon sources, covering sucrose, glucose, soluble starch, and dextrin powder[57−60]. In this study, the optimal carbon source for the mycelium of A. cornea was mannitol, further confirming the wide and diverse utilization of carbon sources by A. cornea. The difference in the carbon utilization may be due to the different locations of the strains, such as growth environment and vegetation, which in turn affect the metabolic level of the mycelium and lead to changes in their preference for carbon sources. Although there are differences in carbon source utilization, most wild strains of A. cornea and some mushroom mycelia exhibit consistency in nitrogen source preference, with organic nitrogen[61−64], which is consistent with the optimal nitrogen source of yeast extract powder for A. cornea mycelium in this study. This may be attributed to the fact that yeast extract powder, as an organic nitrogen source, is better than inorganic ones in mycelial growth for containing vitamins, microelements, and other nutritional compositions[65,66]. In addition, previous studies on A. cornea mycelium, the optimal pH and temperature for the mycelial growth were generally between 7.0–9.0 and 25–30 °C, which is consistent with this study, which was 7.0 and 30 °C, respectively. This strain grows faster in high temperatures and slower in low temperatures, which may be related to the higher daily average temperature of the locality of the strain in Hainan. Normally, the strains of tropical mushroom species grow rapidly at 25 °C or higher temperatures, and they can be carried out in the development of the edible mushroom industry in tropical areas.

Regarding the nutrient composition of A. cornea cultivated in this study, the crude polysaccharide values found (2.93%) were higher than that obtained by Ye et al.[67] but lower than those obtained by Ye et al. [68], which found 3.83% to 10.14% of crude polysaccharide, respectively. Fungal polysaccharides are one of the important active ingredients making mushrooms useful for a wide range of applications in the pharmaceutical, healthcare, and food industries[69,70]. Amino acid score (AAS), also known as protein chemical score, is a widely used method for evaluating the nutritional value of food proteins. It mainly assesses whether a particular amino acid meets the WHO/FAO standards[71,72]. The protein quality of A. cornea is limited by the content of Met and Cys, which necessitates targeted supplementation or combination with other protein sources. The levels of threonine (Thr), isoleucine (Ile), and valine (Val) are higher than the FAO/WHO, indicating that the amino acid composition of this food is closer to the ideal requirement ratio of essential amino acids for the human body. However, its chemical score is lower than that of the whole egg model. These limitations could potentially be addressed by altering the cultivation materials to enhance their amino acid profile.

This study has perfected the growth conditions of wild A. cornea and successfully cultivated fruiting bodies, while also measuring their nutritional components and amino acid content. Hainan tropical rainforests with complex topography and diverse vegetation are endowed with abundant macrofungal resources[73], but the number of cultivated species is relatively limited. Future experiments could focus on screening the cultivation formulas to obtain high-yielding and high-quality strains of A. cornea. This study provides realistic and reliable data support for the development and research of tropical A. cornea and has positive and progressive significance. We will conduct an in-depth study on the growth and development processes of A. cornea at the genetic level, aiming to elucidate the genetic differences and their impact on growth characteristics between tropical and non-tropical regions.

This study was supported by the Hainan Institute of National Park and Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund (ZKYF2023RDYL01, KY-24ZK02), and Yazhou Bay Scientific and Technological Project for Trained Talents of Sanya City (SCKJ-JYRC-2023-74).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Sun JF, Gao Y, Ma HX, Zhu AH; data collection: Ma HX, Qu Z, Wang JF, Liu S; analysis and interpretation of results: Sun JF, Zhu AH, Gao Y; draft manuscript preparation: Sun JF, Zhu AH, Ma HX, Gao Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data generated and analyzed during this study are available in this article. DNA sequence data are available in the GenBank database, and the accession number is PV163959.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Jing-Fang Sun, An-Hong Zhu

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Sun JF, Zhu AH, Gao Y, Qu Z, Liu S, et al. 2025. Identification, biological characteristics, and nutritional analysis of a wild Auricularia cornea. Studies in Fungi 10: e014 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0013

Identification, biological characteristics, and nutritional analysis of a wild Auricularia cornea

- Received: 18 April 2025

- Revised: 14 June 2025

- Accepted: 18 June 2025

- Published online: 30 July 2025

Abstract: A wild strain FCATAS 3346 of Auricularia collected from Qixianling National Forest Park of Hainan Province (China) was isolated in this study. The strain was identified as A. cornea based on a combination of morphological characteristics and internal transcribed spacer sequence (ITS) analyses. To develop and utilize this wild resource, single-factor and orthogonal tests were conducted to investigate the effects of various factors on the mycelial growth of the strain under solid culture conditions. Additionally, cultivation and nutritional composition analysis were conducted. The results showed that the most suitable conditions for mycelial growth of the strain were mannitol 1.0 g/L, yeast extract powder 0.3 g/L, pH 7.0, and a temperature of 30 °C. The optimal substrate formula is sawdust 38%, corncob 20%, bran 20%, cottonseed hull 10%, corn flour 10%, CaCO3 1%, gypsum 1%, and mature fruiting bodies were obtained. Crude polysaccharide content of the fruiting bodies was 2.93%, crude fiber 15.5%, crude fat 2.3%, and ash 2.8%. The restricted amino acids of the fruiting bodies are methionine and cysteine. This study successfully cultivated a wild strain and provide a reference for the exploration and utilization of Auricularia resources in Hainan tropical rainforest and the breeding of new varieties.

-

Key words:

- Amino acid evaluation /

- Auricularia cornea /

- Edible mushroom /

- Cultivation /

- Optimal conditions