-

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture organization (FAO), postharvest losses of agricultural commodities account for approximately 14% of total production[1]. Pathogenic fungi are a major cause of these losses, affecting the quality, nutritional value, and marketability of stored produce. Aspergillus species, notably A. flavus and A. niger, are significant due to their production of aflatoxins, classified as Group 1 human carcinogens by the International Agency For Research on Cancer (IARC)[2]. Penicillium molds infect fruits, vegetables, grains, and stored products such as apples and citrus fruits, reducing marketability and posing health risks through mycotoxins like ochratoxin A[3]. Botrytis cinerea is a versatile pathogen causing grey mold across multiple crops, including grapes and strawberries[4]. Certain Fusarium species produce harmful mycotoxins, such as deoxynivalenol and fumonisins affecting cereals like wheat and maize[5]. Alternaria species, like A. alternata, induce spoilage and may contaminate crops such as tomatoes and carrots with alternariol[6]. Cladosporium species contribute to crop decay and mycotoxin contamination, leading to further storage losses in cereals and fruits[7]. The use of chemical fungicides, such as Thiophanate-methyl, Prochloraz, Propiconazole, and others, is one of the most effective strategies for controlling postharvest plant pathogenic fungi in storage[8]. However, many of these fungicides raise health concerns. For example, Thiophanate-methyl is classified by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) as a probable human carcinogen (Group C), while Prochloraz and Propiconazole are considered suspected endocrine disruptors and have shown carcinogenic potential in animal studies[9]. Prolonged exposure can cause skin, eye, and respiratory irritation, as well as affect the liver, blood, thyroid, endocrine function, reproductive health, and development. Overuse has also led to resistance in fungal pathogens[10].

Biological control offers an alternative, minimizing risks to human health and the environment[11,12]. Trichoderma spp. are well-known biocontrol agents in plant pathology[13,14], engaging in competitive interactions with pathogenic fungi for resources, thus inhibiting their growth[15]. These fungi can directly attack pathogens by entwining around their hyphae and producing lytic enzymes, such as chitinases, glucanases, and proteases, as well as antifungal metabolites[16]. Key antifungal compounds produced by Trichoderma include harzianic acid, trichodermin, gliotoxin, and others, which have demonstrated significant antifungal activity against various postharvest pathogens[17,18]. All studies have focused on competition and secondary metabolite production during the mature stages of Trichoderma growth. However, no research has explored the interactions during the early stages. Focusing on the spore germination stage may reveal unique metabolite profiles that are absent or undetectable during later stages of growth. This study aimed to identify secondary metabolites produced by T. harzianum, T. virens, and T. atroviride during their spore germination stage using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), and to examine their effects on the germination of 18 postharvest pathogenic fungi, including Alternaria spp., Aspergillus spp., B. cinerea, Cladosporium spp., Fusarium spp., and Penicillium spp. The spore germination stage is a critical phase in fungal life cycles, representing a window for rapid establishment and early competition, which is essential for effective biocontrol.

-

To prepare standardized spore suspensions and characterize germination behavior, three species of the genus Trichoderma (T. atroviride, T. harzianum, T. virens) and 18 post-harvest plant pathogenic fungi were obtained from Gorgan University of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources, Iran (Table 1). The propagation of fungi was carried out on autoclaved potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium (Merck 110130). A mycelial disc (5 mm) from the stock culture was aseptically transferred onto PDA plates (pH 7.0). The plates were then incubated (Memmert IN110plus) at 25 ± 2 °C for three days, with a relative humidity of 60%. All culture and germination experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. The spore suspensions were prepared by scraping spores from actively growing cultures with a sterile loop into sterile distilled water. The suspensions were filtered through sterile 200-mesh gauze to remove mycelial fragments. The suspension was transferred into sterile 15 mL tubes and subjected to centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 20 min. Following centrifugation, the supernatant was carefully removed using a sampler, and the resultant pellet, which contained the spores, was resuspended in sterile potato dextrose broth (PDB) medium (Himedia GM403) by transferring it to new tubes. The final spore concentration was adjusted to 1 × 105 spore/mL, using a hemocytometer. For each fungal species, 100 µL of spore suspension was placed on a sterile glass slide within a petri dish, covered with a sterile coverslip, and incubated at 25 ± 2 °C in continuous darkness. Spore germination tests were conducted in triplicate, and appropriate negative controls (slides without spores and without medium) were included to monitor background effects. Observations of spore germination and size (average of 100 spores) were made at 40× magnification using an Olympus CH20i light microscope, with spore size and germination recorded every 30 min.

Table 1. Spore characteristics of fungal isolates.

Specific name *GAU No. **NCBI No. Germination percentage after 12 h Spore

shapeSpore size (µm) ***Final germination length (µm) End of germination

time (h)Germination speed (μm/h) Length width Trichoderma atroviride 6022 MG807425.1 98.6 ± 0.40 ab Ellipsoidal 3.979 ± 0.059 hijk 4.125 ± 0.057 d 5.968575 8.761 ± 0.092 e 0.681 T. harzianum Ah90 KC576649.1 99.2 ± 0.37 ab Oval 3.177 ± 0.057 ijk 3.152 ± 0.060 e 4.764825 8.884 ± 0.071 e 0.536 T. virens 6011 KP671477.1 99.4 ± 0.40 a Oval 2.626 ± 0.029 k 2.595 ± 0.029 h 3.938745 11.800 ± 0.109 c 0.334 Penicillium implicatum MK-RSB19 OP411018.1 99.0 ± 0.01 ab Oval 2.852 ± 0.043 jk 2.905 ± 0.039 f 4.277535 14.780 ± 0.108 b 0.289 P. italicum MK-RSB20 OP411019.1 99.0 ± 0.45 ab Spherical 4.059 ± 0.055 hijk 4.149 ± 0.059 d 6.088485 14.823 ± 0.100 b 0.411 P. expansum MK-RSB18 OP411020.1 98.6 ± 0.40 ab Spherical 4.088 ± 0.062 hijk 4.084 ± 0.056 d 6.13221 14.823 ± 0.100 b 0.414 P. glabrum MK-RSB26 OP411021.1 99.2 ± 0.37 ab Spherical 2.884 ± 0.044 jk 2.912 ± 0.043 f 4.325355 11.782 ± 0.077 c 0.367 P. digitatum MK-RSB10 OP411022.1 98.8 ± 0.20 ab Spherical 2.824 ± 0.045 jk 2.834 ± 0.042 gf 4.236135 14.784 ± 0.051 b 0.287 Aspergillus niger MK-RSB7 OP411015.1 99.0 ± 0.32 ab Oval 4.317 ± 0.069 hij 4.050 ± 0.060 d 6.476145 10.190 ± 0.054 d 0.636 A. flavus MK-RSB28 OP411016.1 99.0 ± 0.45 ab Spherical 4.364 ± 0.072 hij 4.142 ± 0.059 d 6.54576 10.019 ± 0.207 d 0.653 Botrytis cinerea MK-RSB24 OP411017.1 98.8 ± 0.37 ab Ellipsoidal 7.934 ± 0.106 g 8.161 ± 0.116 b 11.90137 14.804 ± 0.066 b 0.804 Cladosporium cladosporioides pc4 MK765911.1 99.0 ± 0.01 ab Cylindrical 15.536 ± 0.278 e 2.587 ± 0.028 h 23.30463 14.718 ± 0.039 b 1.583 C. ramotenellum AM55 MH259170.1 99.4 ± 0.40 a Oval 12.399 ± 0.132 f 4.112 ± 0.052 d 18.59868 22.099 ± 0.219 a 0.842 C. limoniforme Br15 MH245072.1 98.4 ± 0.24 ab Cylindrical 4.655 ± 0.083 hi 1.802 ± 0.042 j 6.9828 14.790 ± 0.100 b 0.472 C. tenuissimum K15 MH258971.1 99.2 ± 0.49 ab Cylindrical 5.137 ± 0.055 h 2.092 ± 0.055 i 7.70484 14.759 ± 0.077 b 0.522 Fusarium oxysporum 7391 MK790682.1 98.8 ± 0.37 ab Fusiform 8.765 ± 0.198 g 3.141 ± 0.055 e 13.14744 14.717 ± 0.091 b 0.893 F. proliferatum pc91 MK765917.1 99.0 ± 0.32 ab Fusiform 19.703 ± 0.317 d 2.667 ± 0.028 hg 29.55448 14.806 ± 0.066 b 1.996 F. solani pc13 MK765916.1 98.2 ± 0.21 b Fusiform 13.612 ± 0.347 f 4.112 ± 0.059 d 20.41795 14.895 ± 0.049 b 1.371 Alternaria alternata MK-RSB6 OP411012.1 99.2 ± 0.20 ab Obclavate 49.795 ± 1.761 a 8.582 ± 0.199 a 74.69284 11.680 ± 0.049 c 6.395 A. tenuissima MK-RSB4 OP411013.1 99.2 ± 0.23 ab Obclavate 29.929 ± 0.594 c 7.640 ± 0.145 e 44.89369 14.754 ± 0.090 b 3.043 A. arborescens MK-RSB9 OP411014.1 98.6 ± 0.24 ab Obclavate 34.556 ± 0.907 b 7.738 ± 0.145 e 51.83403 14.923 ± 0.077 b 3.473 Replicate 5 100 100 5 Sum of squares 10.133 317496.495 8442.868 855.426 df 20 20 20 20 Mean square 0.507 15874.825 422.143 42.771 F-value 0.917 711.693 645.758 845.531 p-value 0.567 0.0001 0.0001 0.0001 * Accession number of culture collection of agricultural microorganisms at Gorgan University of Agricultural Science and Natural Resources. ** Accession number of National Center for Biotechnology Information. *** One and a half times the spore length was considered as the final germination length and growth of the tube before branching and turning into the mycelia. The lowercase letters indicate groups based on Duncan's multiple range test. Extraction of secondary metabolites

-

According to Siddiquee et al.[19], with slight modifications, each Trichoderma sp. was inoculated into a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 100 mL of sterile PDB medium using 10 mL of spore suspension (105 spores/mL). Three biological replicates (flasks) were prepared per species. The flasks were incubated at 26 ± 2 °C on an orbital shaking incubator (Benchmark B00BUA672E) with an agitation speed of 4 m/s² for 12 h, a duration selected to capture the early spore germination stage, before activating mycelial growth. PDB medium was then filtered through a 400-mesh filter to separate the mycelial and conidial biomass from the culture broth. An equal volume of analytical-grade ethyl acetate (Merck 109623) was added to the filtered PDB medium, and the mixture was incubated for 12 h at 25 ± 2 °C to ensure the inactivation of any remaining fungal components. The ethyl acetate was separated from the medium using a Buchner vacuum filtration funnel. The extracts were then evaporated at 60 °C using a rotary evaporator (Chemglass CG-1334-X64). The resulting extract was immediately diluted in 100 mL of HPLC analytical-grade n-hexane (Merck 104391) and either subjected to GC-MS analysis or stored at −20 °C in a laboratory-grade freezer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) until analysis.

Identification of secondary metabolites

-

The GC-MS analysis was conducted using an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph interfaced with an Agilent 5975C mass spectrometer. The GC-MS system employed electron ionization at 70 eV. A non-polar capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 µm film thickness, DB-5MS or its equivalent) was utilized for chromatographic separation. A new and preconditioned DB-5MS column was used to ensure optimal performance and accuracy. The oven temperature was initially set to 60 °C for 1 min, followed by an increase of 10 °C/min until reaching 300 °C, where it was held for 5 min. The injector operated at 300 °C in splitless mode, and the detector temperature was maintained at 320 °C. Helium (99.99% purity, supplied by Linde Gas) served as the carrier gas, flowing at 1.0 mL/min. The mass spectrometer was set with an ion source temperature of 200 °C, scanning in the range of 35–450 m/z at a rate of 0.50 scans per second. A 3-min solvent delay was applied to avoid solvent-related interference.

The system was calibrated using a standard tuning mixture (PFTBA, perfluorotributylamine, Sigma-Aldrich), following the manufacturer's calibration guidelines. Metabolites were identified by comparing mass spectra against the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) library version 23, with a match probability of ≥ 85%. Retention indices (RI) were calculated using a C8–C40 n-alkane series (Sigma-Aldrich) run under the same conditions, and values were compared with literature data for further confirmation. Only compounds with ≥ 85% library match and consistent retention indices were considered positively identified. The identification was qualitative; no internal standard was used for absolute quantification. However, relative abundance was inferred from peak areas in the total ion chromatogram (TIC). Each sample, including both positive (caffeine) and negative (sterile media) controls, underwent triplicate injections.

Evaluation of the spore inhibition activity of secondary metabolites

-

The extract of each Trichoderma sp. was diluted in sterile PDB medium to achieve a concentration of 200 μg/mL. A sterile glass slide was placed in a sterile petri dish, followed by the addition of 1 mL of prepared PDB medium onto the slide. Subsequently, 100 μL of a post-harvest fungal pathogen spore suspension (105 spores/mL) was added onto the slide. The slide was covered with a sterile coverslip and incubated at 26 ± 2 °C with a relative humidity of 60% under dark conditions for 12 h. Spore germination was defined as the emergence of a visible germ tube that was at least half the diameter of the spore. After incubation, germination was assessed under a light microscope, and the percentage of germinated spores was calculated based on a count of 100 spores per replicate. The percentage of spore germination in PDB medium without secondary metabolites served as the control treatment (Table 1). Each experiment was conducted with five replicates, and the inhibition rate was calculated using the following formula:

$ \mathrm{I}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{h}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{b}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{ }\mathrm{r}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{e}\,\left({\text{%}}\right)=\frac{\mathrm{G}\mathrm{c}-\mathrm{G}\mathrm{t}}{\mathrm{G}\mathrm{c}}\times 100 $ where, Gc is the spore germination percentage in the control treatment, and Gt is the spore germination percentage in the presence of secondary metabolites extracted from Trichoderma species during the spore germination phase.

Statistical analysis

-

A completely randomized design was employed to investigate the impact of each Trichoderma sp. extract on the spore germination rate of postharvest plant pathogenic fungi. The collected data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Shapiro-Wilk test (p < 0.05) was used to assess the normality of data, and Levene's test (p < 0.05) was conducted to confirm the homogeneity of variances. ANOVA was performed using SPSS statistical software (Version 21.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Mean values of the treatments were compared using Duncan's multiple range test at α = 0.05. Graphs were created using Microsoft Excel (Version 2211).

-

Microscopic evaluations revealed that the spore size of the fungi differed in terms of length, width, and shape, as detailed in Table 1. The highest and lowest spore length was recorded for A. alternata (49.795 µm) and T. virens (2.626 µm), respectively. In general, based on Duncan's multiple range test, Trichoderma spp., Penicillium spp., Aspergillus spp., Cladosporium limoniforme, and C. tenuissimum were grouped as fungi with spore lengths smaller than 5.2 µm, and no significant difference was observed among them. Approximately 42.85% of the other fungi exhibited a spore length greater than 7.9 µm. Furthermore, A. alternata had the largest spore width (8.58 µm), while C. tenuissimum had the smallest spore width (2.09 µm).

In terms of the end germination time, defined as the time when the length of the germination tube reaches one and a half times the length of the spore, species-specific differences were observed among the fungi in Table 1. T. atroviride and T. harzianum completed their germination period faster than the other species, taking approximately 8.7 and 8.8 h, respectively. C. cladosporioides exhibited the longest time (22 h) to complete spore germination. Approximately 61.90% of the studied fungi could complete the spore germination period within a time range exceeding 14 h. Only T. virens, P. glabrum and A. alternata completed the spore germination period within a time range of 11 to 12 h, and Duncan's multiple range test indicated a non-significant difference in germination time between these species. Additionally, A. niger and A. flavus exhibited a similar spore germination period, ranging from 10 to 11 h. By dividing the final length of the germination tube by the elapsed time, it was determined that F. proliferatum, C. cladosporioides, and F. solani showed the highest germination speeds, measuring 1.9, 1.5, and 1.3 μm/h, respectively. The lowest germination speed was observed in P. digitatum, with a rate of 0.287 μm/h. Among the Trichoderma species, T. atroviride exhibited the highest speed (0.681 μm/h), followed by T. harzianum (0.536 μm/h), and T. virens (0.334 μm/h).

Inhibitory effects of secondary metabolites on post-harvest pathogenic fungi

-

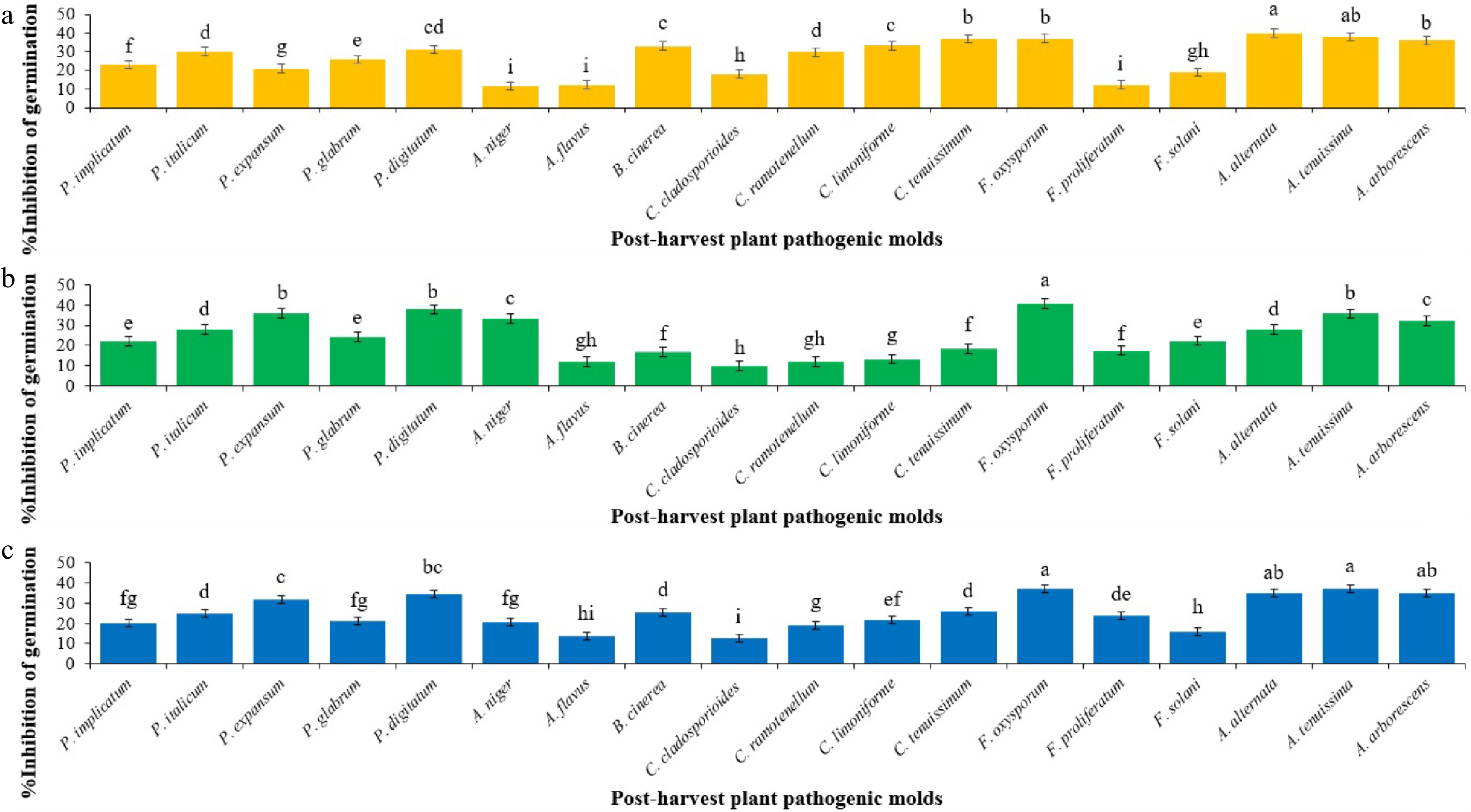

The inhibitory abilities of the secondary metabolites produced by each Trichoderma species varied among the post-harvest plant pathogenic fungi (Fig. 1). This ability displayed a notable distinction even in terms of inhibiting the spore germination of species within the same genus. According to Duncan's multiple range test, the secondary metabolites of T. atroviride displayed the highest inhibitory effect on the spore germination of A. alternata and A. tenuissima, with 39.93% and 37.97%, respectively. No significant difference was observed between them (Fig. 1a). However, according to Duncan's multiple range test, the inhibitory ability of T. atroviride against the spore germination of A. niger, A. flavus, and F. proliferatum was grouped as the least effective treatments, and no significant difference observed between them (Fig. 1a). The secondary metabolites of T. harzianum exhibited the highest inhibitory ability against the spore germination of F. oxysporum, resulting in a reduction of 40.84% (Fig. 1b). On the other hand, the inhibitory capacity of T. harzianum secondary metabolites against the spore germination of A. flavus, C. cladosporioides, and C. ramotenellum reached a minimum level, and Duncan's multiple range test did not indicate a significant difference among them (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, the secondary metabolites of T. virens exhibited the highest inhibitory ability against the spore germination of F. oxysporum, A. alternata, A. tenuissima, and A. arborescens, resulting in reductions of 37.02%, 35.05%, 37.05%, and 35.06%, respectively. No significant difference was observed among these inhibitory effects (Fig. 1c). However, according to Duncan's multiple range test, the inhibitory effect of T. virens secondary metabolites against the spore germination of C. cladosporioides was classified as the least effective when compared to the other post-harvest plant pathogenic fungi (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

Mean comparisons of the inhibition percentage of spore germination of post-harvest fungi as affected by secondary metabolites from initial spore germination stage of each Trichoderma sp. after 12 h. Values are means of five replicates. (a) The effect of T. atroviride on the inhibition of spore germination (Sum of squares: 7,659.592; df: 17; Mean square: 450.564; F-value: 169.764; p-value: 0.0001). (b) The effect of T. harzianum on the inhibition of spore germination (Sum of squares: 8316.157; df: 17; Mean square: 489.186; F-value: 142.419; p-value: 0.0001). (c) The effect of T. virens on the inhibition of spore germination (Sum of squares: 5410.919; df: 17; Mean square: 318.289; F-value: 86.543; p-value: 0.0001). Bars (standard error) with different letters indicate significant differences (Duncan range test subset for α = 0.05).

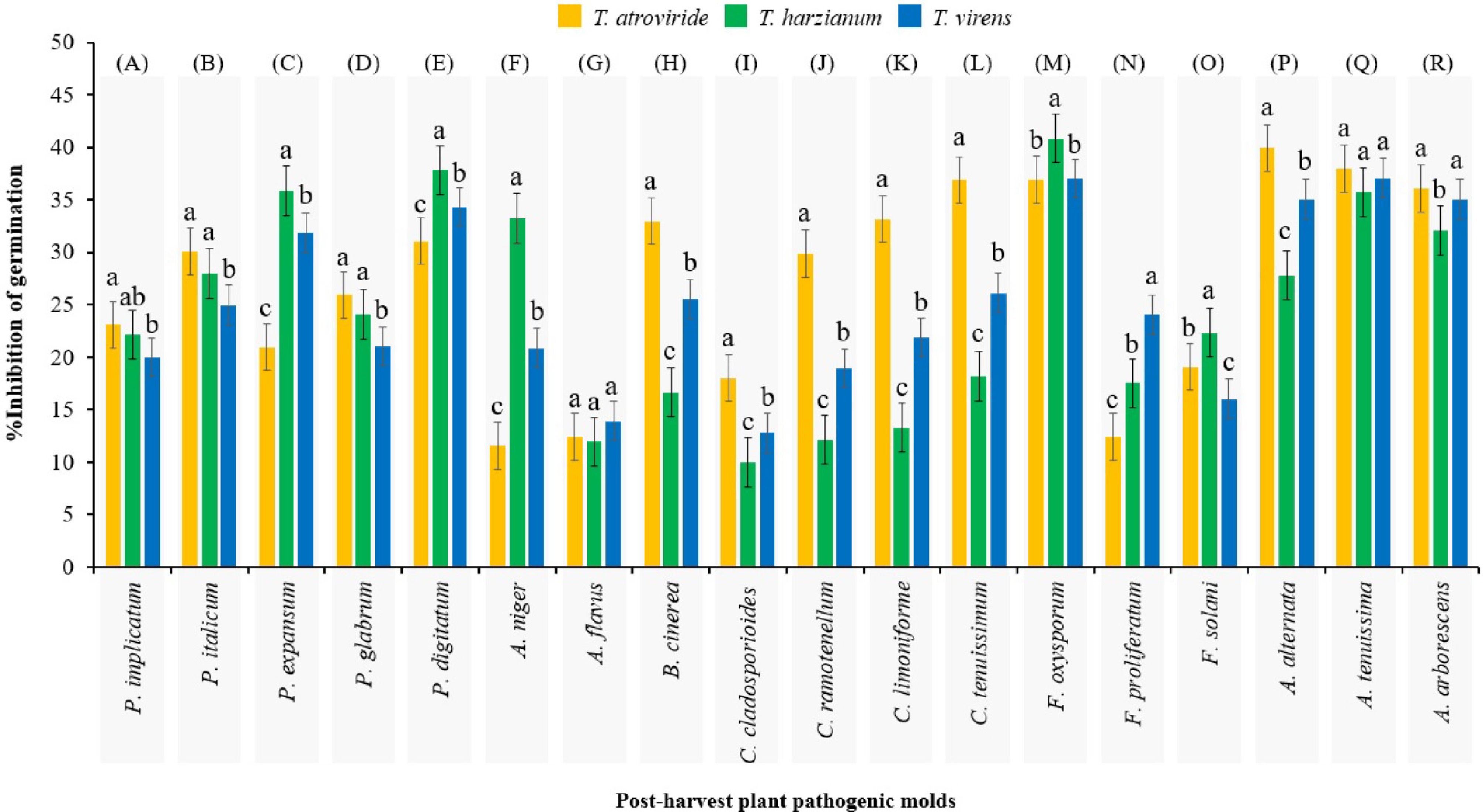

In terms of grouping the inhibitory ability of the secondary metabolites of Trichoderma spp. against spore germination of a post-harvest pathogenic fungus (Fig. 2; Table 2), Duncan's multiple range test did not reveal any significant difference (p > 0.05) in inhibiting A. flavus and A. tenuissima. Secondary metabolites of T. atroviride showed the highest inhibitory ability against spore germination in 50% of the post-harvest plant pathogenic fungi, in comparison to T. virens and T. harzianum. However, T. harzianum revealed highest inhibitory ability against spore germination of P. expansum, P. digitatum, A. niger, F. oxysporum, F. solani, in comparison to T. virens and T. atroviride. Furthermore, secondary metabolites of T. virens only demonstrated the highest inhibitory ability against spore germination of F. proliferatum and A. arborescens, in comparison to T. atroviride and T. harzianum.

Figure 2.

Mean comparisons of the inhibition percentage of spore germination of each post-harvest fungus as affected by secondary metabolites from initial spore germination stage of Trichoderma spp. after 12 h. Values are means of five replicates. Bars (standard error) with different letters indicate significant differences. Sections (A)−(R) are independent experiments that grouped separately by Duncan's range test (subset for α = 0.05), which the results of their analysis of variance are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Results of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for duncan's multiple range test mean comparisons in Fig. 2.

Pathogenic post-harvest fungus Analysis section Sum of squares df Mean square F-value p-value Penicillium implicatum (A) 25.479 2 12.740 3.746 0.054 P. italicum (B) 66.173 2 33.087 8.890 0.004 P. expansum (C) 592.420 2 296.210 89.211 0.0001 P. glabrum (D) 61.142 2 30.571 9.339 0.004 P. digitatum (E) 114.723 2 57.361 18.508 0.0001 Aspergillus niger (F) 1,178.349 2 589.174 191.312 0.0001 A. flavus (G) 10.646 2 5.323 1.557 0.250 Botrytis cinerea (H) 666.296 2 333.148 113.961 0.0001 Cladosporium cladosporioides (I) 166.026 2 83.013 26.223 0.0001 C. ramotenellum (J) 800.174 2 400.087 120.219 0.0001 C. limoniforme (K) 993.039 2 496.519 159.835 0.0001 C. tenuissimum (L) 878.684 2 439.342 147.069 0.0001 Fusarium oxysporum (M) 49.905 2 24.952 6.971 0.010 F. proliferatum (N) 341.754 2 170.877 49.327 0.0001 F. solani (O) 98.872 2 49.436 16.515 0.0001 Alternaria alternata (P) 373.321 2 186.660 54.973 0.0001 A. tenuissima (Q) 12.768 2 6.384 2.014 0.176 A. arborescens (R) 43.295 2 21.648 6.818 0.011 Not significant: p-value > 0.05; Significant: p-value < 0.05. GC-MS profiling of secondary metabolites in T. atroviride

-

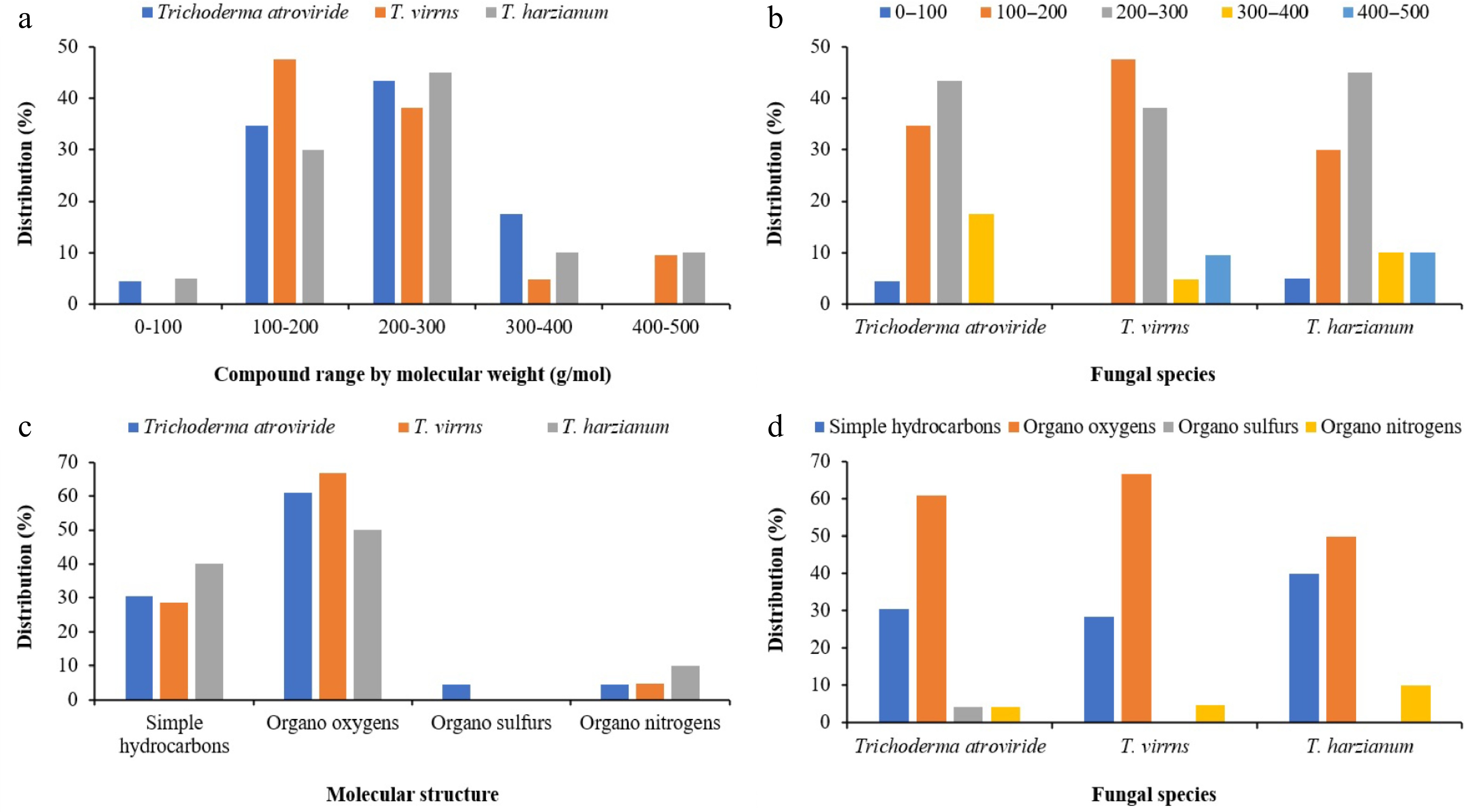

The results of GC-MS analysis revealed the presence of 23 secondary metabolites in the 12-h extract of PDB medium inoculated with T. atroviride spores, as detailed in Table 3 and illustrated in Fig. 3. The molecular weight of these secondary metabolites ranged from 86.134 g/mol (Pentanal) to 390.62 g/mol [1,4-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester]. Secondary metabolites with a weight range between 200 and 300 g/mol exhibited the highest abundance, accounting for 43.47% of the identified metabolites from T. atroviride. Metabolites with a weight range between 100 and 200 g/mol followed, representing a frequency of 34.78%. Only four metabolites, accounting for 17.39% abundance, were detected in the molecular weight range between 300 and 400 g/mol in the 12-h extract of T. atroviride. Metabolites with a molecular weight range below 100 g/mol exhibited the lowest abundance, representing 4.34%. Furthermore, all the metabolites identified in the 12-h extract of T. atroviride was recorded for four chemical classes: simple hydrocarbons, organo-oxygens, organo-sulfurs, and organo-nitrogens. Among the identified metabolites, organo-oxygens and simple hydrocarbons were the most prevalent, accounting for 60.86 and 30.43%, respectively. Organic sulfurs and organo-nitrogens, on the other hand, exhibited the lowest frequency, each accounting for 4.34%. Among the metabolites, 1,4-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester and 2-Hexanone, 5-methyl had the highest (47.78%) and lowest (0.11%) area percentages on the chromatogram graph, respectively.

Table 3. Details of the identified metabolites from initial spore germination stage of Trichoderma atroviride.

Peak no. Metabolite Time Area % Area Molecular formula Molecular weight (g/mol) % Match against NIST* CAS** registration no. 1 Pentanal 11.086 808690 0.8 C5H10O 86.134 78 110-62-3 2 2-Hexanone, 5-methyl 11.164 108673 0.11 C7H14O 114.185 78 110-12-3 3 Tridecane 14.64 13189397 12.97 C13H28 184.36 74 629-50-5 4 Dodecane 18.537 1456396 1.43 C12H26 170.34 94 112-40-3 5 Sulfurous acid, 2-propyl tridecyl ester 25.308 3418750 3.36 C19H40O3S 348.59 95 309-12-4 6 4-Methylcyclohexanol 27.42 2268233 2.23 C7H14O 114.19 82 589-91-3 7 4-Methylheptane-3,5-dione 27.918 1917646 1.89 C8H14O2 142.2 77 1187-04-8 8 5-Tridecanone 28.136 328445 0.32 C13H26O 198.34 76 30692-16-1 9 Lauric acid 28.281 492818 0.48 C12H24O2 200.32 83 143-07-7 10 Margaric acid 28.38 702940 0.69 C17H34O2 270.46 82 506-12-7 11 Pentane, 1-butoxy 28.427 254993 0.25 C9H20O 144.26 88 18636-66-3 12 Cytidine 28.551 429770 0.42 C9H13N3O5 243.22 76 65-46-3 13 1,5-anhydro-arabino-furanose 28.748 1292085 1.27 C5H6O3 114.1 77 51246-91-4 14 Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl) 28.878 3820885 3.76 C14H22O 206.33 96 96-76-4 15 Hexadecane 31.306 2198992 2.16 C16H34 226.44 96 544-76-3 16 1,1-Bis(p-tolyl)ethane 34.347 1348729 1.33 C20H22 262.39 91 98211-18-9 17 Octadecane 36.703 917085 0.9 C18H38 254.51 97 593-45-3 18 Palmitic acid, methyl ester 39.873 3225855 3.17 C17H34O2 270.46 99 112-39-0 19 Benzenepropanoic acid, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-hydroxy-, methyl ester 40.278 6285759 6.18 C23H36O3 360.53 99 6386-38-5 20 Palmitic acid 40.822 6825347 6.71 C16H32O2 256.42 99 57-10-3 21 Eicosane 41.603 859015 0.84 C20H42 282.56 94 112-95-8 22 Tetracosane 46.085 946504 0.93 C24H50 338.65 90 646-31-1 23 1,4-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester 53.106 48578756 47.78 C24H38O4 390.62 91 6422-86-2 * National Institute of Standards and Technology (version 23). ** Chemical Abstracts Service.

Figure 3.

Clustered column charts illustrating the distribution percentages of various metabolites across Trichoderma spp. extracts based on GC-MS analysis. (a) and (b) represent the distribution percentages categorized by molecular weight. (c) and (d) display the distribution percentages classified by molecular structure.

Metabolite characterization of T. virens through GC-MS analysis

-

The quantity of secondary metabolites detected in the 12-h extract derived from PDB medium inoculated with T. virens spores was 9.52% lower compared to those found in T. atroviride, as detailed in Table 4 and illustrated in Fig. 3. GC-MS analysis revealed a total of 21 distinct secondary metabolites present in the extract of germinated T. virens spores. Among these compounds, 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester, demonstrated the highest chromatographic area percentage at 71.94%, whereas 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol exhibited the minimal relative abundance, registering only 0.02%. Notably, none of the metabolites identified within the 12-h T. virens extract possessed molecular weights below 100 g/mol. The most prevalent class of secondary metabolites fell within the molecular weight range of 100 to 200 g/mol, constituting 47.61% of the total detected compounds. This was followed by metabolites with molecular weights ranging from 200 to 300 g/mol, which represented the second most abundant category. Conversely, compounds with molecular masses between 300 to 400 g/mol and 400 to 500 g/mol were comparatively scarce, comprising 9.52% and 4.78%, respectively. Among the metabolites characterized, 2-methyloctacosane exhibited the greatest molecular weight at 408.8 g/mol, while Propene, 1,1'-oxybis was the lightest, at 100.16 g/mol. Interestingly, no organo-sulfur compounds were detected in the extract. The chemical class of organo-oxygen compounds dominated the profile, accounting for 66.66% of the metabolites identified, followed by simple hydrocarbons which constituted 28.57%. Only a single metabolite belonging to the organo-nitrogen class was present within the 12-h T. virens extract.

Table 4. Details of the identified metabolites from initial spore germination stage of Trichoderma virens.

Peak no. Metabolite Time Area % Area Molecular formula Molecular weight (g/mol) % Match against NIST* CAS**

registration no.1 2-Hexanone, 5-methyl 11.045 1308158 0.73 C7H14O 114.19 80 110-12-3 2 Propene, 1,1'-oxybis 11.081 140978 0.08 C6H12O 100.16 78 4696-29-1 3 5-Methyluracil 14.666 14678214 8.19 C5H6N2O2 126.11 80 65-71-4 4 Dodecane 18.532 1324048 0.74 C12H26 170.34 94 112-40-3 5 Tetradecane 25.303 3020121 1.68 C14H30 198.41 94 629-59-4 6 d-Lyxo-d-manno-nononic-1,4-lactone 27.322 559198 0.31 C9H16O9 268.22 72 3080-49-7 7 5-Tridecanone 27.467 515994 0.29 C13H26O 198.34 74 30692-16-1 8 1,5-anhydro-arabino-furanose 27.591 402534 0.22 C5H6O3 114.1 83 51246-91-4 9 Undecanoic acid 28.38 706513 0.39 C11H22O2 186.29 87 112-37-8 10 Pentane, 1-butoxy 28.458 106359 0.06 C9H20O 144.26 83 18636-66-3 11 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol 28.51 37983 0.02 C14H22O 206.32 83 96-76-4 12 Decanoic acid 28.878 4084001 2.28 C10H20O2 172.26 96 112-37-8 13 Hexadecane 31.306 2051964 1.14 C16H34 226.44 96 544-76-3 14 1,1-Bis(p-tolyl)ethane 34.347 1583496 0.88 C16H18 210.31 90 98211-18-9 15 Octadecane 36.703 762932 0.43 C18H38 254.51 95 593-45-3 16 Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester 39.868 2090101 1.17 C17H34O2 270.45 98 112-39-0 17 Benzenepropanoic acid, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-hydroxy-, methyl ester 40.278 6308220 3.52 C14H20O3 236.31 99 6386-38-5 18 Palmitic acid 40.796 2276043 1.27 C16H32O2 256.42 99 57-10-3 19 2-methyloctacosane 46.084 838744 0.47 C29H60 408.8 90 1560-98-1 20 1,4-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester 53.138 128988610 71.94 C24H38O4 390.62 91 422-86-2 21 Phthalic acid, di(2-propylphenyl) ester 56.669 7520123 4.19 C26H26O4 402.5 94 98661-89-0 * National Institute of Standards and Technology (version 23). ** Chemical Abstracts Service. Characterization of secondary metabolites from T. harzianum extract

-

According to the data presented in Table 5 and Fig. 3, the quantity of secondary metabolites detected during the initial spore germination phase of T. harzianum was 15% and 5% lower than that observed in T. atroviride and T. virens, respectively. Nonetheless, the molecular weight distribution of the metabolites identified in T. harzianum exhibited greater heterogeneity compared to the other two species. Overall, GC-MS analysis revealed the presence of 20 secondary metabolites in the 12-h extract of PDB medium inoculated with T. harzianum spores. Among these, only Cyclopentanol was characterized by a molecular weight below 100 g/mol. The most prevalent metabolites fell within the 200 to 300 g/mol and 100 to 200 g/mol weight intervals, constituting approximately 45% and 30% of the total compounds identified, respectively. Metabolites with molecular weights ranging from 300 to 400 g/mol and 400 to 500 g/mol were equally represented, each comprising 10% of the total profile. The heaviest compound identified was 2-methyloctacosane, with a molecular mass of 408.8 g/mol. On the chromatographic profile, 1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester accounted for the greatest relative abundance (49.48%), whereas Cyclopentanol was the least abundant, registering only 0.11%. Chemically, organo-oxygen compounds dominated the metabolite spectrum at 50%, followed closely by simple hydrocarbons at 40%. Notably, organo-sulfur compounds were absent from the metabolite profile of T. harzianum at this stage, while organo-nitrogen compounds were detected at a comparatively lower frequency of 10%.

Table 5. Details of the identified metabolites from initial spore germination stage of Trichoderma harzianum.

Peak no. Metabolite Time Area % Area Molecular formula Molecular weight (g/mol) % Match against NIST* CAS** registration no. 1 2,4-Diamino-6-hydroxypyrimidine 14.614 3064400 3.39 C4H6N4O 126.12 64 56-06-4 2 Dodecane 18.532 1314498 1.45 C12H26 170.34 95 112-40-3 3 Tetradecane 25.303 2574175 2.84 C14H30 198.41 94 629-59-4 4 2-Vinyl-9-[beta-d-ribofuranosyl]hypoxanthine 27.446 2051010 2.27 C12H14N4O5 294.26 77 110851-56-4 5 5-Tridecanone 27.524 209944 0.23 C13H26O 198.34 75 30692-16-1 6 1,5-anhydro-arabino-furanose 27.737 473868 0.52 C5H6O3 114.1 72 51246-91-4 7 Itaconic acid 27.788 85858 0.09 C5H6O4 130.09 85 97-65-4 8 Cyclopentanol 27.892 96554 0.11 C5H10O 86.1323 87 96-41-3 9 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol 28.878 1984097 2.19 C14H22O 206.32 96 96-76-4 10 Hexadecane 31.306 1866061 2.06 C16H34 226.44 98 544-76-3 11 1,1-Bis(p-tolyl)ethane 34.347 1533054 1.69 C16H18 210.31 91 98211-18-9 12 Octadecane 36.697 1005421 1.11 C18H38 254.51 96 593-45-3 13 Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester 39.873 2703467 2.99 C17H34O2 270.45 98 112-39-0 14 Benzenepropanoic acid, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-hydroxy-, methyl ester 40.277 6624034 7.32 C14H20O3 236.31 99 6386-38-5 15 Palmitic acid 40.802 2434738 2.69 C16H32O2 256.42 99 57-10-3 16 Icosane 41.606 2069726 2.29 C20H42 282.54 97 112-95-8 17 2-methyloctacosane 46.089 1568284 1.73 C29H60 408.8 98 1560-98-1 18 Heneicosane, 11-(1-ethylpropyl) 50.214 846188 0.94 C26H54 366.7 87 55282-11-6 19 Phthalic acid, di(2-propylpentyl) ester 53.088 13204422 14.59 C26H26O4 402.5 91 998661-89-0 20 1,4-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-ethylhexyl) ester 56.684 44774953 49.48 C24H38O4 390.62 94 6422-86-2 * National Institute of Standards and Technology (version 23). ** Chemical Abstracts Service. -

The results demonstrate that the secondary metabolites derived from the initial spore germination stage of Trichoderma spp. actively inhibit the spore germination of all post-harvest plant pathogenic fungi. On average, T. atroviride, T. harzianum, and T. virens exhibited inhibitory activities of 27%, 24%, and 25%, respectively, against spore germination of 18 post-harvest fungal pathogens. According to the literature, secondary metabolites derived from the mycelial growth stage of Trichoderma spp. have shown efficacy against Penicillium spp.[18,20], Aspergillus spp.[14,15,20], B. cinerea[20−22], Cladosporium spp.[20,23], Fusarium spp.[15,20,24−26], and Alternaria spp.[27,28]. Although these studies, in line with our findings, highlight the significant bioactivity of Trichoderma spp. metabolites, none have investigated the compounds produced specifically during the spore germination stage.

This study provides the first evidence that spore germination metabolites of Trichoderma spp. serve as key competitive factors in the environment, enabling rapid niche colonization and suppression of competing spores before hyphal establishment, thereby positioning Trichoderma spp. as early ecological dominants in microhabitats. GC-MS analysis identified 39 secondary metabolites produced by T. harzianum, T. virens, and T. atroviride during this early developmental stage. Of these, 30.76% were unique to T. atroviride, while 12.82% and 15.38% were specifically produced by T. virens and T. harzianum, respectively. Additionally, 23.07% of the compounds were shared across all three species. Another 12.82% were common to T. virens and T. harzianum, whereas only 5.12% were shared between T. atroviride and T. virens. These early-stage Trichoderma metabolites show potential for biocontrol, particularly in postharvest settings where fungal spores are present but mycelial growth hasn't begun.

Diversity of initial spore germination stage metabolites of Trichoderma spp.

-

Several metabolites identified in this study have previously demonstrated antimicrobial activity during the mycelial growth stage of Trichoderma spp. For example, we exclusively detected lauric acid in T. atroviride, a compound that has also been reported during the mycelial stage of T. atroviride, T. harzianum, and T. asperellum[29−31]. Studies have confirmed that monolaurin, a derivative of lauric acid, inhibits various fungal species, including Candida albicans[32] and Trichophyton rubrum[33]. Researchers attribute this antifungal activity to monolaurin's ability to disrupt fungal lipid membranes, leading to cell lysis and death[34]. We also identified palmitic acid, methyl ester exclusively from T. atroviride, which belongs to the class of fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs). Studies have shown that FAMEs derived from vegetable oils exhibit antifungal activity against pathogens such as Paracoccidioides spp., C. glabrata, C. krusei, and C. parapsilosis[35]. Additionally, FAMEs extracted from Sesuvium portulacastrum leaves have demonstrated antimicrobial effects against both bacterial and fungal human pathogens[36]. The production of palmitic acid and its methyl ester has also been observed during the mycelial stage of T. longibrachiatum and T. reesei[37,38]. Palmitic acid was also detected in all Trichoderma species examined in this study. In vitro experiments have revealed that palmitic acid effectively inhibits C. tropicalis and its biofilm formation, a critical factor in fungal pathogenicity[39]. Previous research has reported the biosynthesis of palmitic acid during the mycelial phase of T. virens and T. harzianum[16].

We identified undecanoic acid exclusively during the spore germination stage of T. virens. However, prior studies have reported this metabolite during the mycelial stage of T. harzianum, T. koningii, T. koningiopsis, and T. asperellum[31,40−42]. Rossi et al.[43] highlighted undecanoic acid's potential as a therapeutic antifungal agent. Similarly, the study of Lee et al.[44] demonstrated its ability to interfere with fungal communication and exert antibiofilm and anti-virulence effects against C. albicans. Moreover, Avrahami & Shai[45] explained that conjugating undecanoic acid with amino acid-containing antimicrobial peptides enhanced their antifungal activity. Although earlier studies have identified decanoic acid during the mycelial stage of T. viride, T. koningii, T. koningiopsis, T. reesei, and T. virens[40,46−48], we detected it only during the spore germination stage of T. virens.

The antifungal mechanism of decanoic acid is believed to involve membrane disruption, causing cellular leakage and fungal cell death[49]. Itaconic acid was uniquely detected in T. harzianum in this research, whereas previous studies have reported its presence during the mycelial stage of T. reesei[50]. Itaconic acid has been found to exert anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects[51]. Multiple studies have explored itaconic acid's antimicrobial roles in macrophages and its function as an endogenous antimicrobial metabolite[52]. A study reported the antibacterial activities of hexadecanoic acid methyl ester against multidrug-resistant bacteria[53]. We also identified hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester similar from T. virens and T. harzianum, which is commonly referred to as methyl palmitate and has been isolated from the mycelial stage of T. pseudokoningii[17,20]. Differences in metabolite profiles between germination and mycelial stages suggest that Trichoderma probably regulates secondary metabolism in a phase-specific manner, likely influenced by environmental and developmental signals, an area worth further study.

Metabolites without an antifungal background

-

Several metabolites identified during the initial spore germination stage of Trichoderma spp. in this study, as well as those reported during the mycelial phase in previous investigations, have not been shown to possess direct antifungal activity. For example, we exclusively detected tridecane in T. atroviride during spore germination, although Siddiquee et al.[19] previously reported it during the mycelial stage of the same species. Similarly, we identified dodecane during the spore germination stage of all Trichoderma spp., while earlier studies have documented its presence only during the mycelial phase of T. harzianum[29]. Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl), was detected exclusively in T. atroviride in our current analysis, whereas Mulatu et al.[54] found this compound in the mycelial stage of T. asperellum and T. longibrachiatum. Although we identified hexadecane in T. atroviride, T. harzianum, and T. asperellum, previous literature has confirmed its occurrence only in the mycelial stage of T. harzianum[55]. In alignment with our findings, the literature also confirms that octadecane appears commonly in both spore germination and mycelial stages of T. atroviride, T. harzianum, and T. virens[56,57].

We exclusively identified eicosane during the spore germination stage of T. atroviride, while earlier studies reported this compound only in the mycelial phase of T. harzianum[58]. Furthermore, literature findings indicate that tetradecane occurs during the mycelial stage of T. biocontroller, T. harzianum, T. viride, T. asperellum, and T. virens[59−61]. However, we detected it during the spore germination stage of T. virens and T. harzianum. Both phthalic acid, di(2-propylphenyl) ester and 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol were identified in the spore germination stage of T. virens and T. harzianum in this study. In contrast, previous reports have described phthalic acid, di(2-propylphenyl) ester only during the mycelial stage of T. pinnatum[62], and 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol from T. asperellum[63]. Consistent with our results, the literature also confirms the presence of 2,4-diamino-6-hydroxypyrimidine in both the spore germination and mycelial phases of T. harzianum[64]. Importantly, 56.41% of the metabolites identified in this study have not been previously reported in any Trichoderma species. However, the study is limited to extracellular compounds and spore germination assays. Future research should explore metabolite synergy, molecular regulation, broader pathogen targets, and real-world efficacy.

-

These findings elucidate the crucial role of these metabolites in mediating the initial competitive interactions of Trichoderma spp. with other fungi, thereby enhancing their dominance in the environment. By unraveling the ecological significance of these metabolites in Trichoderma interactions with other organisms and the surrounding environment, our study contributes to a deeper understanding of microbial ecology and secondary metabolite biology. Importantly, these insights also have practical implications for postharvest disease management. The early production of antifungal metabolites suggests that Trichoderma spp. can be strategically employed to suppress pathogenic fungi during vulnerable postharvest stages. Understanding the timing and profile of metabolite release may inform the development of more effective biocontrol formulations, enabling targeted application to reduce spoilage and losses in storage and supply chains.

This study was an intra-academic research project of Gorgan University of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Kamran Rahnama. The authors thank for Dr. Kevin David Hyde (Professor at Center of Excellence in Fungal Research, Mae Fah Luang University) for valuable scientific advice during this research project. This work was financially supported by Gorgan University of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources (Grant No. 00-45-666).

-

This research did not involve any studies with human participants, and no ethical approval was required according to the institutional and national regulations.

-

All authors contributed to the study's conception and design. Kamran Rahnama contributed to conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing – review and editing. Nima Akbari Oghaz contributed to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, software, validation, visualization, and writing of the original draft. Nooshin Drakhshan contributed to conceptualization, data curation, investigation, validation, visualization, writing – review and editing. Ruvishika Shehali Jayawardena contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, validation, visualization, writing – review and editing. All participating authors read, commented, and approved the current version of the manuscript.

-

Raw data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The genome sequences and related information of utilized fungi in this research project are available online at the GenBank Nucleotide database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Rahnama K, Oghaz NA, Derakhshan N, Jayawardena RS. 2025. Antifungal metabolite profiling and inhibition assessment of Trichoderma-derived compounds during initial spore germination stage against postharvest pathogens. Studies in Fungi 10: e015 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0015

Antifungal metabolite profiling and inhibition assessment of Trichoderma-derived compounds during initial spore germination stage against postharvest pathogens

- Received: 30 January 2025

- Revised: 30 June 2025

- Accepted: 01 July 2025

- Published online: 08 August 2025

Abstract: The objective of this study was to identify antifungal secondary metabolites produced during the early spore germination stage of Trichoderma harzianum, T. virens, and T. atroviride and evaluate their inhibitory effects on spore germination for 18 postharvest fungal species including Alternaria, Aspergillus, Botrytis cinerea, Cladosporium, Fusarium, and Penicillium on PDA medium supplemented with 200 μg/mL of secondary metabolites derived from each Trichoderma species. Secondary metabolites were extracted with ethyl acetate, diluted in n-hexane, and identified by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) using a non-polar column and NIST23 library matching (≥ 85%). In comparation with control (p ≤ 0.05), T. atroviride showed the highest inhibition of spore germination in A. alternata (39.93%), and A. tenuissima (37.97%). T. harzianum was most effective against F. oxysporum (40.84%); and T. virens inhibited F. oxysporum (37.02%), A. alternata (35.05%), A. tenuissima (37.05%), and A. arborescens (35.06%). Among 39 identified metabolites, 30.76%, 12.82%, and 15.38% originated from T. atroviride, T. virens, and T. harzianum, respectively. Furthermore, 23.07% were common to all three species. Additionally, 12.82% of the compounds were shared between T. virens and T. harzianum, while only 5.12% were shared between T. atroviride and T. virens. Several antifungal metabolites, including lauric acid, palmitic acid methyl ester, undecanoic acid, decanoic acid, itaconic acid, and hexadecanoic acid methyl ester, were identified during the initial spore germination stage of Trichoderma spp. The antifungal metabolites identified likely contribute to the ecological competitiveness of Trichoderma in the natural environment and underscore their potential in suppressing plant pathogens in agriculture.

-

Key words:

- Germination speed /

- Spore characterizations /

- Biological control /

- Ecology of fungi