-

Clean air is a fundamental requirement for human health and well-being and is recognized by the United Nations as a key component of the Sustainable Development Goals[1]. However, air pollution remains a pressing global issue, contributing to significant environmental degradation and adverse health effects. Major sources of air pollution include industrial activities, vehicular emissions, biomass combustion, and fossil fuel-powered generators, which release harmful pollutants such as nitrogen oxides (NOX), sulfur oxides (SOX), carbon monoxide (CO), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and particulate matter (PM)[2,3]. These pollutants degrade air quality and pose severe health risks, including respiratory diseases, cardiovascular disorders, and lung cancer, with an estimated 7 million premature deaths attributed to air pollution annually[4,5]. Developing regions, particularly in Africa, are experiencing rising emissions due to increasing fossil fuel consumption. It is projected that annual SO2 and NOx emissions in Africa will nearly double by 2030, intensifying air pollution-related illnesses[6]. In Nigeria, where unreliable electricity supply has led to widespread dependence on diesel generators, generator emissions significantly contribute to air pollution, climate change, and occupational health risks[7,8]. Given these concerns, continuous air quality monitoring is crucial for assessing pollutant exposure and informing regulatory measures to mitigate environmental and health impacts.

In regions with unstable electricity supply, diesel generators are widely used but contribute significantly to air pollution. In Nigeria, emissions from diesel-powered home generators exceed those from workplaces, trucks, and buses, posing heightened health and environmental risks due to their proximity to residences and extended usage durations[9−11]. Generators supply nearly half of the total energy needs in Nigeria, making them the third-largest source of PM2.5 pollution and a significant health hazard to residents[12−14]. Studies have highlighted severe air pollution at generator sites across Nigeria, with emissions of carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), sulfur oxides (SOₓ), and particulate matter frequently exceeding safe exposure limits. Lawal et al.[15] found that CO emissions from petrol-fired generators peaked at 733 ppm, surpassing the WHO exposure limit of 87 ppm within just 15 min, while Oguntoke & Adeyemi[16] reported extreme pollutant concentrations at generator sites, contributing to widespread respiratory ailments. Furthermore, inefficient generator use in Nigerian households exposes individuals to dangerously high CO levels, with concentrations reaching up to 60 ppm—six times the WHO safety threshold[17]. The issue extends beyond residential and commercial areas to critical infrastructure, as backup diesel generators (BUGs) at mobile telecommunications base stations release significant air pollutants across states such as Lagos, Kano, and Oyo[18]. This heavy reliance on generators extends beyond residential and commercial spaces to agricultural settings, including mushroom farming, where a continuous power supply is essential for maintaining controlled growing conditions.

Due to inconsistent power supply, most mushroom farms depend on generators for power, creating potential risks of pollutant exposure in cultivation environments. In developing countries like Nigeria, where unstable electricity supply affects agricultural production, diesel and petrol generators serve as a primary power source for mushroom farms, ensuring optimal temperature, humidity, and ventilation within controlled environments. Since mushrooms require specific growth conditions, generators often operate continuously to maintain artificial climate control, leading to prolonged pollutant emissions in enclosed farming structures. Studies have shown that generator exhaust releases harmful air pollutants such as CO, NOX, SOX, VOCs, and PM, which can accumulate in indoor spaces with poor ventilation[19]. The prolonged operation of generators near mushroom farms raises concerns about potential contamination of the growing environment, as pollutants settle on substrates or get absorbed into fungal tissues[20−22]. This exposure could affect not only mushroom yield and quality but also pose health risks to consumers due to the bioaccumulation of toxic substances.

Mushrooms have a natural ability to absorb and accumulate environmental pollutants, making them useful bioindicators. While studies have assessed the impact of generator emissions on indoor and outdoor air quality[23,24], limited research has explored their effects on biological systems, particularly fungi, which are known to bioaccumulate environmental pollutants. Although mushrooms have been used as bioindicators of heavy metals, hydrocarbons, and airborne contamination in the environment[25,26], their application in monitoring airborne pollutants from fossil fuel combustion remains largely unexplored. They acquire nutrients from decaying organic matter[27], but in polluted settings, they also take up toxic elements, including lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which can accumulate in their tissues at levels exceeding those found in the surrounding air or soil[28]. This ability makes them valuable for monitoring environmental contamination, but it also raises concerns about food safety when mushrooms are cultivated in polluted environments. Consumers who ingest contaminated mushrooms may unknowingly expose themselves to harmful substances, making it essential to evaluate pollutant levels in mushrooms grown near emission sources such as generators.

Despite the widespread use of generators in agriculture, limited studies have assessed their impact on air quality in mushroom farms. Given that mushrooms are highly susceptible to airborne contaminants due to their bioaccumulative properties, it is essential to understand how prolonged exposure to generator emissions affects both air quality and food safety in controlled cultivation environments. This study aims to evaluate atmospheric pollutant levels in a generator-powered mushroom farm and assess the extent of bioaccumulation in Pleurotus ostreatus, a widely cultivated edible mushroom. By measuring key air pollutants such as CO, NOX, SOX, VOCs, and PM, alongside hydrocarbon accumulation in mushroom tissues, this research seeks to establish a direct link between generator emissions and potential contamination risks. Findings from this study will provide more insights into the environmental and health implications of generator use in food production settings, emphasizing the need for improved ventilation, alternative energy solutions, and regulatory measures to ensure safer agricultural practices.

-

The study was conducted at the Federal University of Petroleum Resources (FUPRE), Nigeria, focusing on the generator house at the College of Science building. This location was chosen due to its proximity to generator-powered electricity supply and its potential exposure to airborne pollutants. The generator set used in this study had a capacity of 2,500 kVA. The geographical coordinates of the generator house were recorded using Google Maps' Global Positioning System (GPS), and are as follows: latitude: 5°34′2.2″ N, longitude: 5°50′30.4″ E.

Mushroom strains and placement

-

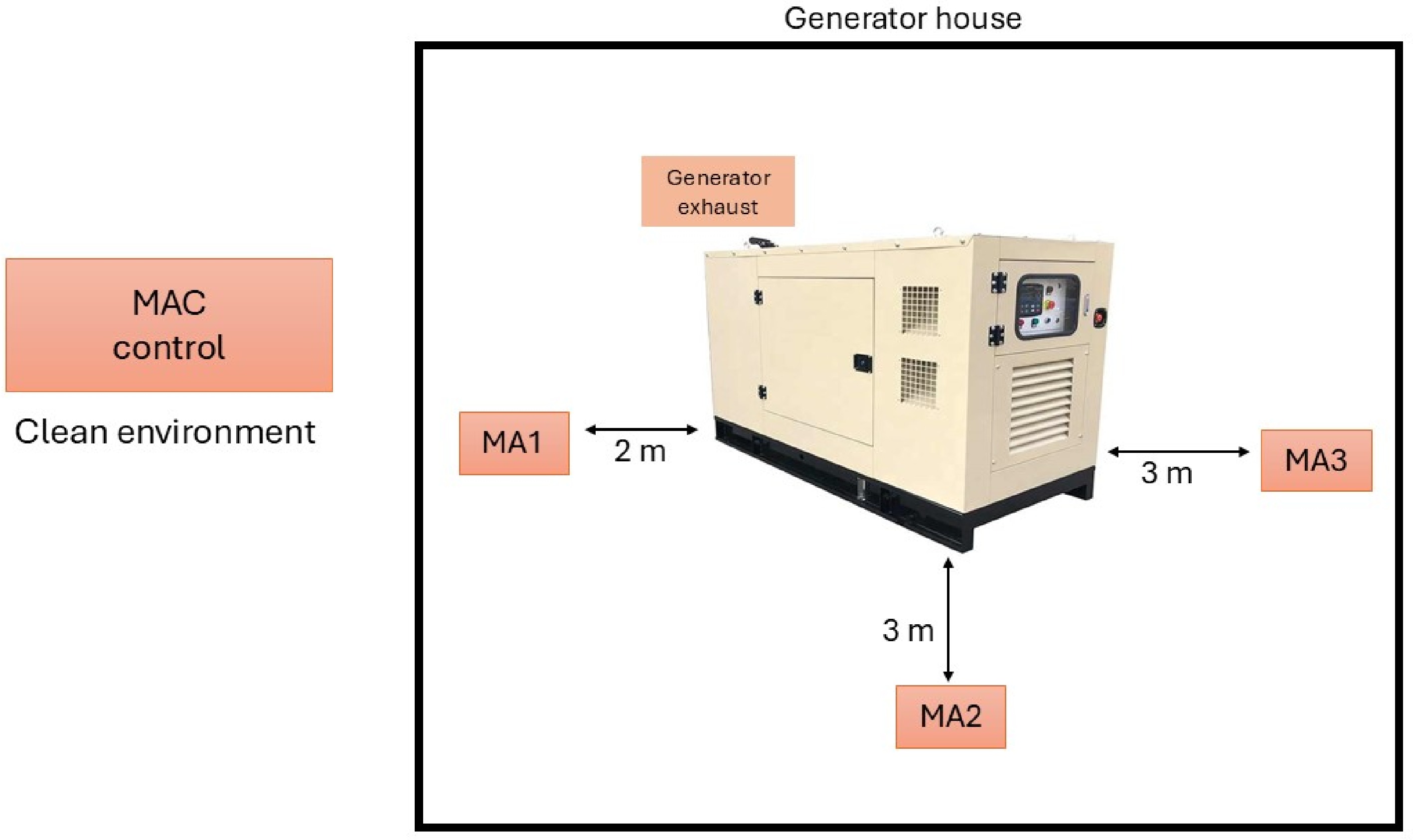

Four Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) were obtained from the African Center for Mushroom Research and Technology Innovation, University of Benin. To prevent contamination during transportation, the mushroom bags remained sealed with their protective coverings (rubber band, paper wrap, cotton wool, and PVC pipe) intact (Fig. 1a). At the experiment site, these coverings were gently removed to expose the fruiting bodies. Three of the mushrooms (labeled MA 1, MA 2, and MA 3) were placed inside a generator house at different distances from the generator exhaust to monitor pollutant exposure. MA 1 was placed 2 m from the exhaust, while MA 2 and MA 3 were placed 3 m away on the opposite end of the room, as shown in Fig. 2. All bags were placed on raised platforms to avoid contact with ground moisture and runoff (Fig. 1b). The fourth mushroom (labeled MAC) served as a control and was kept in a clean, well-ventilated indoor space far from any generator emissions. Each mushroom bag served as a separate biological replicate, and the setup was maintained for 7 d.

Figure 1.

(a) Pre-exposure sample in original packaging. (b) Experimental sample following exposure within the generator house. Observable changes include the onset of sprouting, discoloration, and the development of potential fungal growth, indicating a response to the environmental conditions. A transparent nylon barrier was employed to capture any potential liquid or particulate matter released during the exposure period.

Figure 2.

Experimental setup for pollutant exposure monitoring using oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus). Three mushroom bags (MA 1 = 2 m; MA 2 and MA 3 = 3 m from the generator) were placed at different corners inside a roofed but open generator house near an operating diesel generator. A fourth bag (MAC) served as a control and was placed in a clean, well-ventilated indoor environment away from generator emissions.

Air quality monitoring

-

Air quality parameters were measured using handheld devices, including the AeroTrack Handheld Particle Counter, which was used to monitor particulate matter (PM10) concentrations, and Portable Gas Samplers, which were employed for monitoring greenhouse gases such as NOx, SOx, CO, H2S, and O3. Meteorological instruments, including sensors for wind speed, temperature, relative humidity, and atmospheric pressure, were also used. These instruments were calibrated a week before use according to manufacturer specifications to ensure the accuracy of measurements. Air quality was measured at both the generator house and the control site, located in a bush area of the Twin Building, 500 m away from the generator house.

Sample collection and preparation

-

Sample collection followed the guidelines established by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA)[29]. However, in this study, black polythene bags were used instead of Teflon containers for collecting mushroom samples after 7 d of exposure. The study duration of 7 d was chosen due to the typical growth cycle of the Pleurotus ostreatus, which takes approximately 5 to 9 d to reach maturity, making it suitable for the analysis of pollutant absorption over this period[30]. The sample collection process involved harvesting the mushrooms after the exposure period, storing them in a refrigerator at < 4 °C until further analysis. The organic extraction of the samples was performed using n-pentane, with an ultrasonic apparatus utilized for optimal recovery of pollutants. The mushroom samples were processed by extracting 10 g of mushroom tissue in 20 mL of n-pentane, followed by three extraction steps using ultrasonic treatment.

Gas chromatography and analysis

-

Gas Chromatography (GC) was used for the analysis of Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons (TPHs) and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) on a Hewlett Packard 5890 Series II-Plus gas chromatograph, equipped with an HP 7673 Autosampler and FID detector. The analysis was carried out using a 30 mm × 0.32 mm DB-5 fused silica capillary column (95% methyl-5% phenylpolysiloxane). The oven temperature was programmed from 40 °C (held for 3 min) to 300 °C at a rate of 15 °C/min. Helium was used as the carrier gas, with a linear velocity of 38 cm/s (15 psig). The detector and injector temperatures were set at 250 and 320 °C, respectively. Sample injection was performed in splitless mode, with the relay open for 20 s. Data analysis was conducted using Agilent Chemstation chromatography software (version 10), and all measurements were carried out in triplicate to ensure reliability and accuracy.

Meteorological and environmental data collection

-

Meteorological data such as wind speed, temperature, relative humidity, and atmospheric pressure were recorded during the study period. These data were used to evaluate the environmental conditions under which the air pollutants were measured. This information is crucial for understanding the dispersion and persistence of pollutants in the environment.

Statistical analysis

-

Data visualization was carried out using GraphPad Prism 10.

-

The purpose of this study was to assess the air quality around a generator house to determine the possible exposure of mushrooms to organic fumes and other atmospheric contaminants. The results obtained from the generator house were compared with those from the control site to identify potential differences in environmental conditions, as shown in Table 1 and Fig. 3. Wind speed was lower in the generator house (0.6 m/s) than in the control site (2.2 m/s). Reduced air circulation in the generator house could contribute to pollutant accumulation, increasing the potential exposure of mushrooms to airborne contaminants. Temperature remained constant at both locations (29.4 °C), indicating that thermal variations did not play a significant role in influencing pollutant dispersion. Similarly, relative humidity values were comparable (74.1% in the control and 73.3% in the generator house), suggesting that humidity levels were not a major factor affecting contaminant presence. Although temperature values appeared constant, the limited ventilation in the generator house may have caused localized heat retention, which could have influenced mushroom physiology. This may help explain the visibly reduced development of fruiting bodies observed in the exposed samples.

Table 1. Comparative air quality parameters at the generator house and control site.

Control point Generator house SPM (µg/m3) 22 37.5 Noise (dB) 50.3 97.8 Wind speed (m/s) 2.2 0.6 Temperature (°C) 29.4 29.4 Relative humidity (%) 74.1 73.3

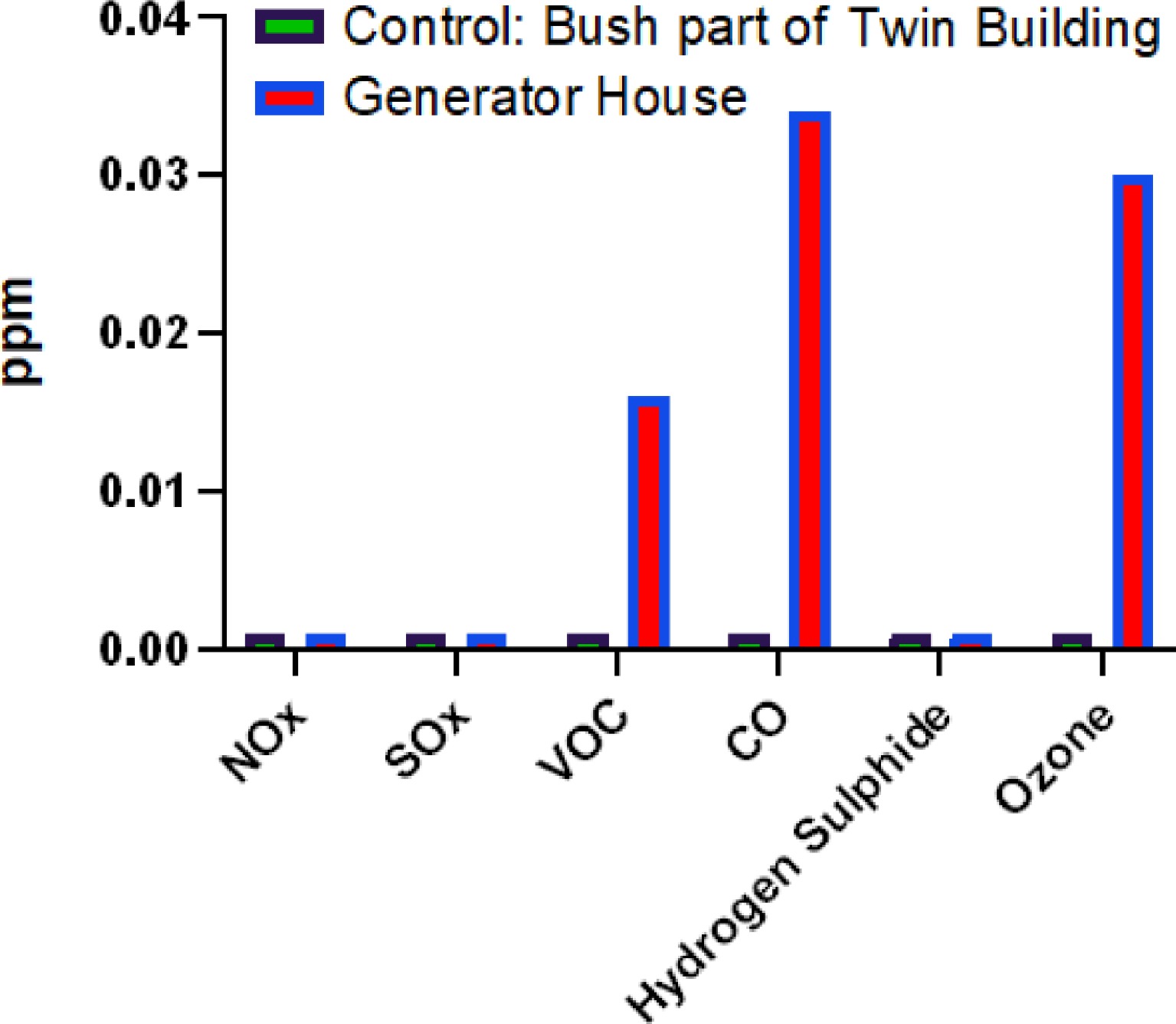

Figure 3.

Air quality parameters measured at the generator house and control site (the control site was a 400-capacity building surrounded by natural vegetation, chosen to contrast with the generator house's pollutant exposure). The values represent pollutant concentrations and environmental conditions to assess the potential exposure of mushrooms to airborne contaminants.

The concentrations of NOx and SOx in both the generator house and control site were below detectable limits (< 0.001 ppm). This suggests that the generator operation did not contribute significantly to the presence of these pollutants in the ambient air at the time of sampling. Given that the Department of Petroleum Resources (DPR) limit for NOx is 0.07 ppm and the Federal Ministry of Environment (FMENV) range is 0.04–0.06 ppm, the recorded values indicate compliance with regulatory standards. VOC levels were higher in the generator house (0.016 ppm) compared to the control site (< 0.001 ppm). Although this concentration is well below the World Health Organization (WHO) indoor guideline value of 0.6 ppm for total VOCs[31], its presence suggests that generator emissions may be a source of VOC pollution, which is known to arise from incomplete fuel combustion. Prolonged or repeated exposure to VOCs, even at low levels, can contribute to irritation, respiratory symptoms, and the formation of secondary pollutants[32,33].

CO levels were higher in the generator house (0.034 ppm) than in the control site (< 0.001 ppm), although well below the regulatory limits set by DPR (10 ppm) and FMENV (10 ppm). This concentration is also significantly lower than the WHO 8-h guideline of 10 ppm[34]. Nevertheless, its elevated presence in a semi-confined space such as a generator house raises concern over cumulative exposure risks for humans and the potential physiological stress on exposed organisms[35]. The elevated CO levels indicate incomplete combustion in the generator, which is a common source of air pollution in confined or semi-confined environments. H2S was below detectable limits in both locations, suggesting no significant release of this gas from the generator house. However, ozone levels were considerably higher in the generator house (0.03 ppm) compared to the control site (< 0.001 ppm). This increase could be attributed to photochemical reactions involving VOCs, which can lead to ozone formation in environments with sufficient light exposure. Although the concentration is below the WHO 8-h exposure guideline of 0.05 ppm[36], the presence of ozone in a confined setting is noteworthy. Ozone is a reactive oxidative pollutant formed via photochemical reactions involving VOCs and nitrogen oxides. It is known to affect both respiratory health and plant/microbial physiology by inducing oxidative stress[37]. In this context, it may have contributed to observed morphological changes in the exposed mushrooms.

SPM levels were higher in the generator house (37.5 µg/m3) than in the control site (22 µg/m3). While both values remain within the permissible limits set by DPR (90 µg/m3) and FMENV (250 µg/m3), the increased particulate concentration in the generator house suggests the presence of combustion-generated aerosols, which could be absorbed by mushrooms. The noise level in the generator house was recorded at 77.8 dB, significantly higher than in the control site (50.3 dB) but within the regulatory range of 80–100 dB set by DPR and the 90 dB limit set by FMENV. This difference highlights the impact of generator operations on noise pollution, which could influence the physiological responses of mushrooms growing in the area. The air quality in this study was similar to that recorded by Ohadugha et al.[17] which reported high carbon monoxide (CO) levels from household generator use in Minna, Nigeria. While our study recorded CO levels of 0.034 ppm in the generator house, the authors found significantly higher concentrations, reaching 60 ppm—well above the WHO limit of 10 ppm. This highlights the impact of generator emissions on air quality, though the Minna study focused on indoor household exposure, whereas this research examined pollutant accumulation in mushrooms. The elevated levels of VOCs, CO, O3, and SPM in the generator house suggest a higher potential for mushroom exposure to airborne contaminants.

TPH accumulation in mushrooms

-

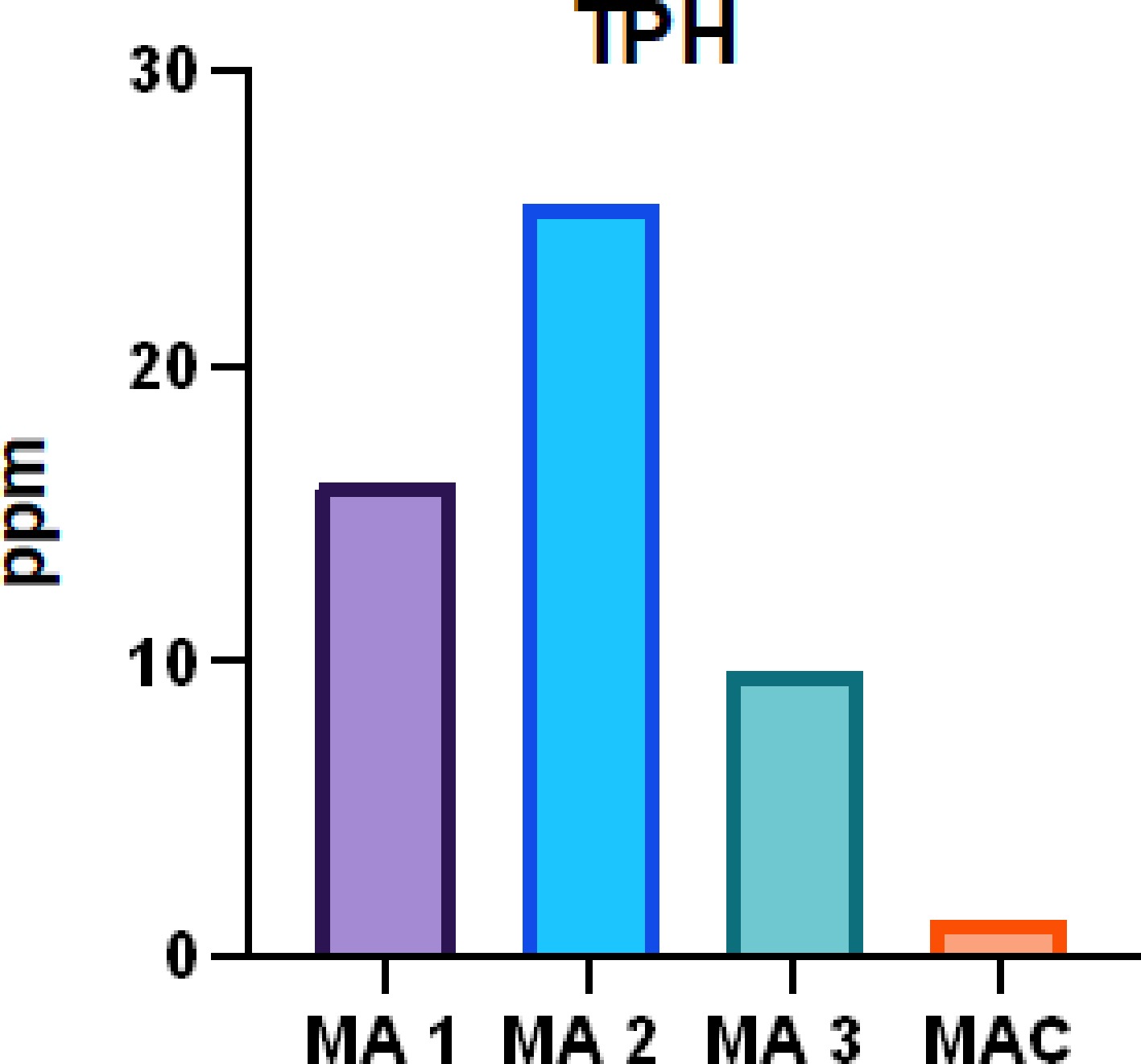

The results indicate that mushrooms placed in proximity to the generator house absorbed varying levels of TPH, as shown in Fig. 4. The highest concentration of TPH (25.509 ppm) was recorded in MA 2 (3 m), followed by MA 1 (2 m) with 16.085 ppm, and MA 3 (3 m) with 9.703 ppm. The control mushroom (MAC), placed outside the generator house, exhibited the lowest concentration (1.214 ppm), suggesting minimal exposure to petroleum-based pollutants in the ambient environment.

Figure 4.

Concentrations of TPH in mushrooms placed at different distances (MA 1: 2 m; MA 2 and MA 3: both 3 m) within the generator house and the control mushroom (MAC). The values indicate the extent of hydrocarbon absorption, highlighting the influence of pollutant dispersion and airflow patterns.

The differences in TPH accumulation among the mushrooms can be attributed to air circulation patterns and pollutant dispersion within the generator house. Wind speed in the generator house was significantly lower (0.6 m/s) compared to the control site (2.2 m/s), indicating restricted air movement. The low wind speed may have led to localized accumulation of hydrocarbons, with variations in concentration depending on specific placement within the confined space. The higher TPH concentration in MA 2 (3 m) compared to MA 1 (2 m) suggests that certain positions within the generator house may have experienced higher pollutant deposition, potentially influenced by airflow turbulence, pollutant settling, and structural barriers. The relatively lower TPH level in MA 3 (3 m) compared to MA 2 indicates that airflow and pollutant dispersion were not uniform, possibly due to uneven ventilation or proximity to emission sources.

The presence of TPH in all mushrooms within the generator house supports the hypothesis that mushrooms can absorb and accumulate airborne hydrocarbons from petroleum combustion sources. Given that volatile and semi-volatile hydrocarbons can adhere to particulate matter, the elevated Suspended Particulate Matter (SPM) levels (37.5 µg/m3 in the generator house vs 22 µg/m3 at the control site) further suggest that airborne particulates may serve as a vector for hydrocarbon transport and deposition onto mushroom surfaces. While mushrooms have been shown to accumulate PAHs from soils[38−40], little is known about the uptake from air pollution. The results from the present study indicate the potential of uptake from air sources.

PAH accumulation in mushrooms

-

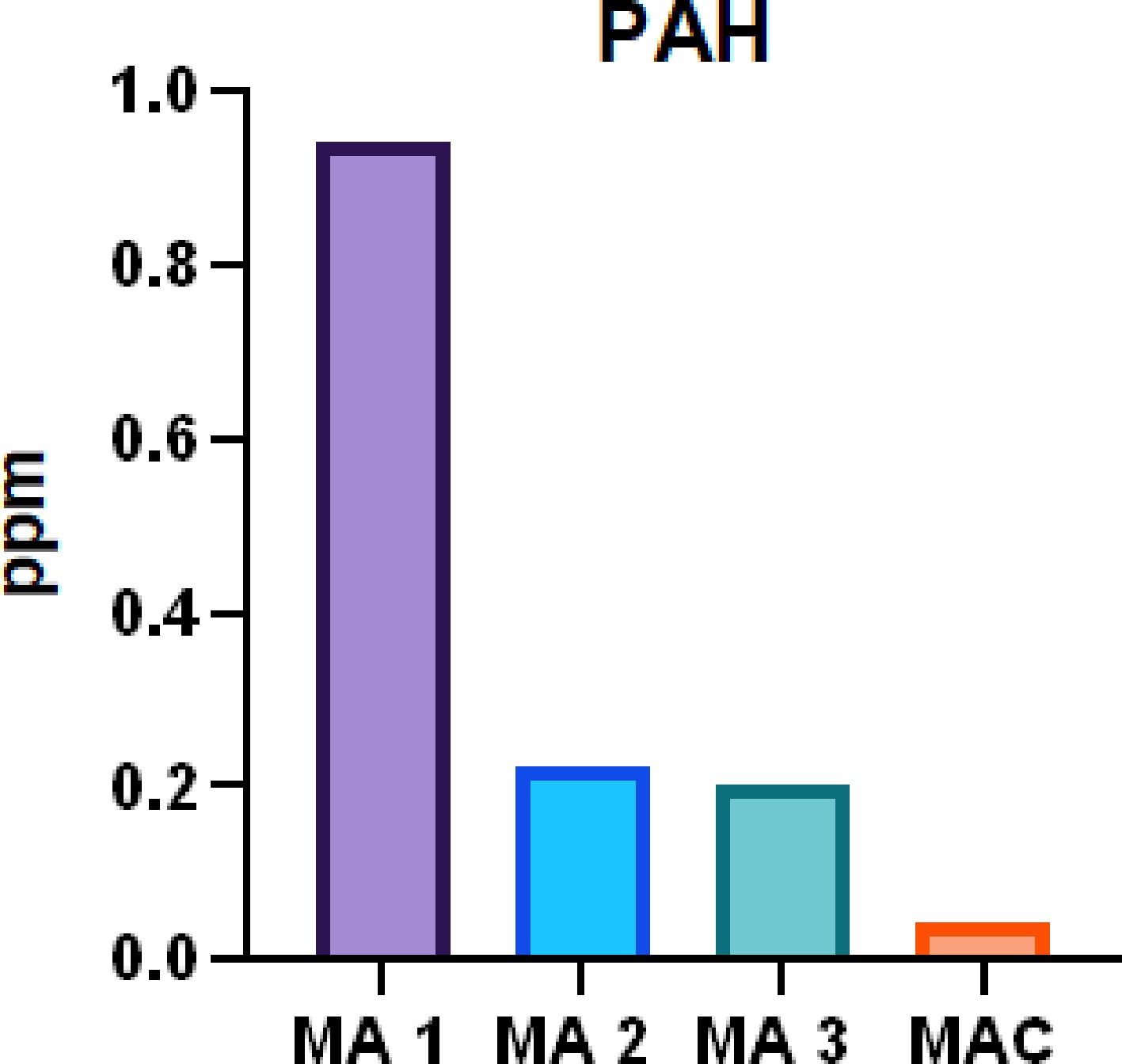

Airborne pollutants generated from fossil fuel combustion, including petroleum hydrocarbons and PAHs, pose significant environmental and health risks. Among these pollutants, PAHs are persistent organic compounds known for their potential carcinogenic and mutagenic effects. In this study, we examined the accumulation of PAHs in mushrooms positioned at different distances within a generator house to assess their ability to absorb and retain these airborne contaminants. The results are presented in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

PAH in mushrooms placed at different distances within the generator house and a control site.

The concentrations of PAHs in mushrooms within the generator house varied, indicating differential exposure and absorption. The highest total PAH concentration was recorded in MA 1 (2 m) at 0.94 ppm, followed by MA 3 (3 m) at 0.20 ppm and MA 2 (3 m) at 0.16 ppm. MAC exhibited a lower PAH concentration of 0.22 ppm, suggesting limited exposure to combustion-derived contaminants. Among the individual PAH compounds detected, naphthalene, benzo(a)pyrene, and fluoranthene were prominent, with marked differences in their concentrations across the sampled mushrooms. Naphthalene was highest in the control mushroom (0.12 ppm) and MA 1 (0.11 ppm), indicating its volatility and potential dispersion in both polluted and less-polluted environments. The detection of benzo(a)pyrene, a well-known carcinogenic PAH, in MA 1 (0.03 ppm) and MA 2 (0.02 ppm) suggests a significant accumulation of combustion byproducts in mushrooms closest to the generator emissions. Additionally, benzo(b)fluoranthene was highest in MA 2 (0.02 ppm), while fluoranthene was detected only in the control mushroom (0.01 ppm), highlighting variations in PAH deposition and uptake.

The increased PAH concentrations in mushrooms placed near the generator house suggest that combustion-derived pollutants accumulate in fungal tissues, potentially posing risks for human consumption. The variation in PAH profiles among the mushrooms could be attributed to differences in volatility, deposition rates, and airflow patterns within the generator house. The lower wind speed (0.6 m/s) recorded in the generator house compared to the control site (2.2 m/s) likely facilitated pollutant accumulation, reducing dispersion and enhancing PAH retention in nearby mushroom gills. Research by Igbiri et al.[41] demonstrated that mushrooms exposed to vehicular emissions accumulated significant levels of PAHs, particularly low-molecular-weight compounds such as naphthalene and anthracene, raising concerns about their suitability for consumption. The current study aligns with these findings, emphasizing the role of mushrooms as bioindicators of air pollution. However, the variations observed in PAH distribution indicate the need for further investigation into the factors influencing pollutant uptake, including fungal species, environmental conditions, and pollutant sources.

The presence of TPH in all mushrooms within the generator house supports the hypothesis that mushrooms can absorb and accumulate airborne hydrocarbons from petroleum combustion sources. Given that volatile and semi-volatile hydrocarbons can adhere to particulate matter, the elevated Suspended Particulate Matter (SPM) levels (37.5 µg/m3 in the generator house vs 22 µg/m3 at the control site) further suggest that airborne particulates may serve as a vector for hydrocarbon transport and deposition onto mushroom surfaces. While mushrooms have been shown to accumulate PAHs from soils[42−45], little is known about the uptake from air pollution. However, Pleurotus ostreatus is known for its high metabolic versatility and the secretion of extracellular enzymes such as laccases and peroxidases, which allow it to degrade and absorb complex organic compounds, including hydrocarbons[46−48]. These enzymes enable the breakdown of aromatic rings found in petroleum-based pollutants, facilitating their bioaccumulation within fungal tissues. The porous surface of the mushroom's fruiting body and its high surface-area-to-volume ratio increase its ability to capture airborne pollutants through direct contact or diffusion. The results from the present study indicate the potential of uptake from air sources.

-

Air pollution from generator emissions poses significant environmental and health risks, particularly in enclosed spaces where pollutants can accumulate. This study assessed air quality within a generator house at FUPRE using both hand-held devices and mushrooms as bioindicators. Key findings indicate that volatile organic compounds VOCs, CO, O3, and SPM were elevated in the generator house compared to the control site, suggesting that generator emissions contribute to localized air pollution. Mushrooms placed within the generator house exhibited significant accumulation of TPHs and PAHs, confirming their ability to absorb airborne pollutants. Interestingly, TPH concentrations were highest in mushrooms placed 2-3 m from the generator exhaust, indicating that pollutant dispersion within the generator house is influenced by airflow dynamics. These findings have important implications for air quality monitoring in confined spaces, particularly in environments where generators are a primary source of power. The study highlights the potential for mushrooms to serve as bioindicators of air pollution, providing a cost-effective and environmentally sustainable method for assessing exposure to combustion-related contaminants. Furthermore, the results indicates the need for improved ventilation and emission control measures to mitigate pollutant accumulation in generator houses. However, the study has some limitations. The short exposure duration (7 d) may not fully capture long-term pollutant accumulation trends in mushrooms. Additionally, variations in airflow and pollutant dispersion within the generator house could have influenced pollutant deposition patterns. Future research should explore longer exposure periods, different fungal species, potential health implications of contaminated mushroom consumption, and the impact of seasonal variations on pollutant bioaccumulation. The findings reinforce the need for continued air quality monitoring in environments reliant on generator power and support the use of bioindicators in pollution assessment. Investigating the influence of seasonal climatic variables such as temperature, humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation will also be valuable, as these factors directly affect pollutant dispersion, photochemical reactions (e.g., ozone formation), and fungal physiology. These expanded approaches will help assess the consistency and reliability of bioaccumulation patterns under varying environmental conditions.

-

This study did not involve human or animal subjects, and as such, ethical approval was not required.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Ogunkeyede AO; research design: Ogunkeyede AO, Isukuru EJ; data interpretation: Ogunkeyede AO, Isukuru EJ; sample collection, data analysis, writing – original draft: Isukuru EJ; writing – review & editing: Ogunkeyede AO, Bankole AO, Bosah AE, Kikanme KN, Isukuru EJ; laboratory analysis and data collection: Bosah AE. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

We wish to thank Professor John Okhuoya, Director, African Centre for Mushroom Research and Technology Innovation, University of Benin, for his guidance on the use of mushrooms for the study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ogunkeyede AO, Bankole AO, Bosah AE, Kikanme Kenneth N., Isukuru EJ. 2025. Preliminary assessment of atmospheric pollutant bioaccumulation in mushrooms exposed to generator emissions. Studies in Fungi 10: e016 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0017

Preliminary assessment of atmospheric pollutant bioaccumulation in mushrooms exposed to generator emissions

- Received: 03 April 2025

- Revised: 30 June 2025

- Accepted: 09 July 2025

- Published online: 21 August 2025

Abstract: Air pollution from fossil fuel combustion poses environmental and health risks, particularly in energy-deficient regions where generator use is prevalent. This study assessed air quality in a generator house at the Federal University of Petroleum Resources (FUPRE) using handheld air monitoring devices and the Pleurotus ostreatus mushroom as a bioindicator. Air quality parameters, including NOx, SOx, CO, H2S, O3, and VOCs, were measured using portable monitors, alongside meteorological factors. After seven days, Gas Chromatography-Flame Ionization Detection (GC-FID) was used to analyze the accumulation of TPH and PAH in the mushrooms. Results showed elevated VOCs (0.016 ppm), CO (0.034 ppm), O3 (0.03 ppm), and suspended particulate matter (37.5 µg/m3) around the generator house, while NOx, SOx, and H2S were below detectable limits. Hydrocarbon bioaccumulation was highest in mushrooms placed 2 and 3 m from the generator exhaust (TPH: 25.509 ppm; PAHs: significant benzo(a)pyrene levels), decreasing with distance. These findings demonstrate Pleurotus ostreatus as a viable bioindicator for airborne pollutants and indicate the need for improved ventilation in generator houses to reduce occupational exposure risks. Future studies should investigate long-term pollutant effects, seasonal variations in air pollutants, and responses of other fungal species to enhance environmental monitoring.