-

Oil crops, such as soybean, peanut, rapeseed, sesame, and flaxseed, are essential sources of edible oils, providing vital fatty acids and serving as a cornerstone of human nutrition. The storage oils in these seeds, primarily in the form of triacylglycerol (TAG), are not only a significant source of calories during seed germination and seedling establishment, but also meet diverse industrial needs, including the production of nylon, lubricants, biodiesel, and cosmetics[1,2]. During the middle and late stages of seed development, TAG, the main storage lipid in seeds, is synthesized on the endoplasmic reticulum through the Kennedy pathway and subsequently stored in lipid droplets (LDs)[3]. LD is a structure consisting of a TAG core enveloped in a monolayer phospholipid membrane, with various attached proteins present on its surface[4]. The accumulation of oil in LDs is fundamentally a process of phase separation, wherein hydrophobic lipids segregate from the aqueous cytosol, facilitated by polar lipids. Following TAG assembly in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), LD formation proceeds through lens formation, budding, growth, and fusion—all of which involve dynamic interactions between polar lipids and membrane systems.

This perspective systematically integrates current knowledge on the molecular mechanisms of LD formation, growth, and fusion in eukaryotic cells, highlighting key regulatory pathways and unresolved questions in the field. By critically evaluating recent advances, this perspective aims to provide a cohesive framework for understanding lipid storage dynamics and its metabolic coordination with other cellular processes. Furthermore, it discusses emerging strategies for manipulating LD traits to improve oil accumulation in crops, pointing to promising avenues for future research in both basic and applied plant lipid biology.

-

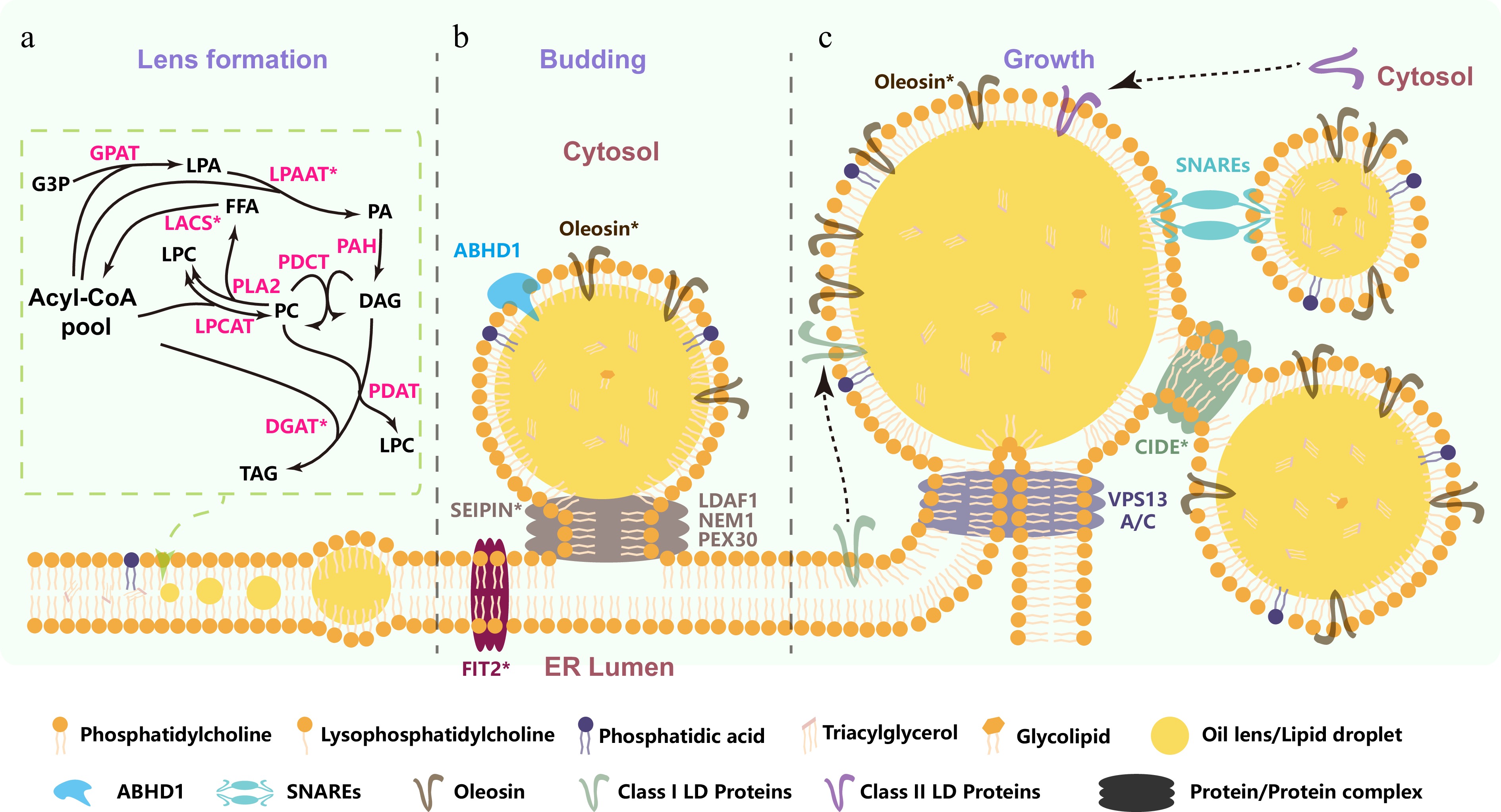

TAG synthesis initiates with fatty acid production in plastids, where the prokaryotic pathway utilizes malonyl-CoA to generate C16- or C18-carbon acyl-ACP pools[5]. Released free fatty acids are activated to acyl-CoA as an acyl donor, transported to the ER[5]. In the ER, TAG is assembled via the Kennedy pathway (Fig. 1a). In this pathway, glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) is first acylated at the sn-1 position by glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase (GPAT), forming lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)[5]. Next, lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase (LPAAT) acylates LPA at the sn-2 position to produce phosphatidic acid (PA), a critical step shared with phospholipid biosynthesis[5]. Phosphatidate phosphatase (PAH) then dephosphorylates PA to generate diacylglycerol (DAG)[5]. TAG synthesis is completed through the rate-limiting acylation of DAG at the sn-3 position, catalyzed either by diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT) using acyl-CoA[5], or by phospholipid:diacylglycerol acyltransferase (PDAT) using phosphatidylcholine (PC) as the acyl donor[5]. Concomitantly, PC serves as as the central hub for acyl editing processes (Fig. 1a): fatty acid desaturation on ER mainly occurs on PC; using acyl-CoA as the acyl donor, lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) is acylated at the sn-2 position by lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase (LPCAT) to form PC; conversely, PC can be deacylated by phospholipase A2 (PLA2) to produce LPC and free fatty acids (FFA), which are subsequently esterified with CoA via LACS[5]. Furthermore, phosphatidylcholine: diacylglycerol cholinephosphotransferase (PDCT) catalyzes the transfer of the phosphocholine headgroup from PC to DAG, facilitating acyl exchange between phospholipids and neutral lipids[5]. As PC serves not only as a fundamental membrane constituent but also as an acyl donor in TAG assembly, acyl editing dynamically adjusts fatty acid composition for both membrane fluidity and TAG profiles.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of TAG biosynthesis and lipid droplet formation. (a) TAG biosynthesis and lens formation: TAG assembly occurs in the ER via the Kennedy pathway (G3P → LPA → PA → DAG → TAG), supplemented by acyl-CoA flux from acyl editing at PC and acyl-transfer from PC via PDAT or PDCT. Newly synthesized TAG aggregate into lens-like structures via phase separation on the leaflets of the ER bilayer. (b) SEIPIN-driven lipid droplet budding: SEIPIN interacts with specific proteins and lipids to drive lipid droplet budding via phase separation and membrane remodeling. (c) LD growth and fusion mechanisms: cytosolic LDs grow via Ostwald ripening and fuse through protein-mediated mechanisms. G3P, sn-3 glycerol 3-phosphate; LPA, lysophosphatidic acid; PA, phosphatidic acid; PC, phosphatidylcholine; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; DAG, 1,2-diacyl-sn-glycerol; FFA, free fatty acids; TAG, triacylglycerol; DGAT, diacylglycerol acyltransferase; GPAT, sn-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase; LACS, long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase; LPAAT, lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase; LPCAT, lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase; PDAT, phospholipid:diacylglycerol acyltransferase; PDCT, phosphatidylcholine:diacylglycerol cholinephosphotransferase; PLA2, phospholipase A2; PAH, phosphatidate phosphatase; FIT2, fat storage-inducing transmembrane protein 2 from mammals; LDAF1, lipid droplet assembly factor 1 from mammals; NEM1, Nuclear Envelope Morphology 1 from mammals; PEX30, Peroxin 30 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae; ABHD1, α/β hydrolase domain-containing protein 1 from Chlamydomonas; VPS13A/C, Vacuolar Protein Sorting-associated Protein 13 A/C from mammals; SNARE, Soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors from mammals; CIDE, Cell Death-Inducing DFFA-like Effector from mammals. Overexpression of asterisk-marked proteins enhances seed oil content.

As hydrophobic molecules, newly synthesized TAG aggregates into lens-like structures via phase separation on the leaflets of the ER bilayer when their concentration reaches a critical threshold (2.8–10.0 mol%)[3]. The formation of these lipid lenses, driven by localized TAG accumulation and ER membrane lipid remodeling, may occur spontaneously[6] or be influenced by factors such as ER membrane surface tension, curvature, and local lipid or protein composition[6−8]. Lipids including neutral diacylglycerol (DAG) and conical polar phospholipids (e.g., PA) cooperatively facilitate TAG nucleation and lipid lens formation by modulating ER membrane curvature and surface tension[9].

LD budding

-

Following lens formation, TAG aggregates exclusively at SEIPIN-enriched ER subdomains[10]. Current studies demonstrate that SEIPIN cooperates with its interacting partners, including lipid droplet assembly factor 1 (LDAF1), Nuclear Envelope Morphology 1 (NEM1), and Peroxin 30 (PEX30), to establish lipid droplet budding sites by driving the aggregation of neutral lipid lens structures at specific ER subdomains, where phase separation and membrane remodeling trigger directional LD formation[6]. This assembly occurs via the growth and budding of neutral lipid lenses into LDs under the action of SEIPIN-containing protein complexes (Fig. 1b), which induce ER bilayer deformation and promote budding toward the cytosolic side[6]. This budding process is modulated by lipid and protein factors. Elevated LPC levels in the ER reduce membrane surface tension, facilitating budding, whereas DAG, phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and PA increase surface tension and inhibit budding[9]. The spatial distribution of lipid species, with PA and DAG accumulating on the lumenal side of the ER membrane, and LPC aggregating on the cytoplasmic side, likely determines the directionality of budding. Moreover, fat storage-inducing transmembrane protein 2 (FIT2), featuring two transmembrane domains and a luminal phosphatase-active domain, converts luminal phospholipids to DAG, increasing cytosolic membrane tension and driving LD budding toward the cytoplasm[8,11]. Recent studies demonstrate that ABHD1 (α/β hydrolase domain-containing protein 1), localized to LD surfaces in Chlamydomonas, promotes LD budding and lipogenesis by hydrolyzing lyso-DGTS (diacylglyceryl-N,N,N-trimethylhomoserine)[12,13]. In vitro enzymatic assays and artificial LD systems confirm that ABHD1 hydrolyzes lyso-DGTS and enhances LD assembly. Furthermore, ABHD1 overexpression elevates LD abundance and increases TAG content, suggesting a potential strategy to modulate LD surface composition and TAG accumulation in plants[12,13].

LD growth and fusion

-

Cytosolic LDs grow into larger, more stable structures via Ostwald ripening (Fig. 1c), optimizing lipid storage efficiency[6]. Inter-droplet neutral lipid transfer is mediated by Cell Death-Inducing DFFA-like Effector (CIDE) family proteins[14], while Vacuolar Protein Sorting-associated Protein 13 A/C (VPS13A/C) facilitates neutral lipid transport from the ER to LDs[15]. LD growth further requires phospholipid monolayer remodeling, driving the trafficking of phospholipid synthesis-associated proteins. Cytosolic LDs connect to the ER via membrane bridges that mediate protein transport. Soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors (SNAREs) are not only essential structural components of membrane fusion machinery, as demonstrated in inter-organelle bridge formation[16], but also implicated in LD formation through putative regulatory interactions. However, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying their different roles in these distinct cellular processes remain to be fully elucidated.

LDs turn out to contain a set of proteins, which appear to target LDs either from the ER or from the cytosol. Class I LD proteins—defined by ER-to-LD trafficking—include representative members such as glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 4 (GPAT4), ancient ubiquitous protein 1 (AUP1), diacylglycerol acyltransferase 2 (DGAT2), and acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 3 (ACSL3)[4]. These proteins utilize ER-derived membrane bridges for translocation to lipid droplets and primarily function in lipid synthesis[4]. In plants, as the most abundant Class I LD proteins on LD surfaces, oleosin and caleosin both play critical roles in LD formation and integrity[17]. In contrast, Class II LD proteins (e.g., CIDEs) represent cytoplasmic-originating proteins that directly target lipid droplets via amphipathic helices or post-translational modifications, thereby bypassing ER-dependent pathways[14]. Critically, CIDE-C/FSP27 specifically promotes LD fusion by localizing to LD-LD contact sites, where its CIDE-C-terminal domain facilitates neutral lipid transfer between droplets[18].

-

Oil crops serve as a primary source of edible oils in human diets, providing essential fatty acids and critical nutritional components. Increasing oil content in oilseeds remains a major challenge for agricultural scientists and bioengineers. Current strategies primarily focus on overexpressing key regulators in the triacylglycerol (TAG) assembly pathway[19]. Notably, LPAAT overexpression in rapeseed, a key enzyme in phospholipid metabolism, elevates oil content by 25%–29% (Tropaeolum majus LPAAT) or 38.9%–49.4% (Brassica napus LPAAT) increase in oil content, significantly outperforming other carbon flux regulators. In contrast, overexpression trials of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase), LACS, DGAT1, and Wrinkled 1 (WRI1) yielded more moderate increases (ranging from 5%–16.9%)[19−22]. Critically, lipidomic analysis revealed that polar lipids, particularly lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), contributed most significantly to lipid accumulation in the endosperm of monocotyledonous oats and wheat[23]. These findings underscore the critical role of polar lipid metabolism in oil accumulation.

Enhancement of LD formation overcomes bottlenecks in oil accumulation

-

Emerging evidence demonstrates that overexpressing LD-associated protein significantly enhances seed oil content (Table 1). In Arabidopsis, overexpression of the native SEPIN gene increases seed oil content by 10%[24]. Heterologous expression of mouse CIDEs and FIT2 individually enhances seed oil content by over 10%[18,25,26], while co-expression of oleosin with mouse DGAT2 boosts oil accumulation by 20%[27]. These transgenic approaches reveal TAG packaging into nascent LDs as a key rate-limiting step in oil accumulation. Importantly, LD-associated proteins exhibit substantial bioengineering potential by redirecting carbon storage toward lipid production without requiring enhanced carbon flux. Moreover, emerging evidence supports that LD-associated proteins not only enhance seed oil biogenesis but also mitigate TAG accumulation suppression induced by non-canonical fatty acids (e.g., hydroxylated fatty acids)[28,29]. These findings suggest that efficient TAG sequestration into LDs synergizes with enhanced biosynthesis for oilseed improvement.

Table 1. Protein candidates to enhance plant oil content,

Stage Protein Function Plant oil content enhancement Ref. TAG assembly and lens Formation GPAT G3P to LPA using acyl-CoA-derived acyl / LPAAT LPA to PA using acyl-CoA-derived acyl Yes [20] PAH PA to DAG / DGAT1 DAG to TAG using acyl-CoA-derived acyl Yes [22] PDAT1 DAG to TAG using PC-derived acyl No [5] LACS FFA to FA-CoA Yes [21] PLA2 PC to LPC and FFA / LPCAT LPC to PC using acyl-CoA-derived acyl / PDCT Transfer of the headgroup from PC to DAG / LD budding FIT2 Converts luminal phospholipids to DAG, driving LD

budding toward the cytoplasmYes [25] SEIPIN Drive lipid phase separation, triggering LD nucleation Yes [24] LDAF Member of SEIPIN Complex / LDAP Member of SEIPIN Complex No [34] NEM1 Member of SEIPIN Complex / PEX30 Member of SEIPIN Complex / LDIP Member of SEIPIN Complex / LD growth and fusion VPS13A/C Facilitate neutral lipid transport from the ER to LDs / SNAREs Facilitate LD membrane fusion machinery, enabling

inter-organelle bridges/ CIDEs Mediate TAG transfer between LDs Yes [18,26] Crucially, LD-associated proteins bypass metabolic bottlenecks inherent in conventional approaches that target upstream fatty acid synthesis, which often face trade-offs with growth due to carbon substrate competition. Instead, these proteins directly enhance TAG sequestration, mitigating conflicts between specialized fatty acid production (e.g., industrially valuable hydroxylated fatty acids) and bulk oil accumulation[28,29]. This strategy not only increases storage capacity but also counteracts TAG suppression caused by non-canonical fatty acids, reinforcing LD biogenesis as a complementary and scalable approach for oilseed improvement.

-

In plants, TAG accumulation involves encapsulating neutral lipids within a monolayer phospholipid membrane embedded with proteins. LD biogenesis—including formation, budding, and growth—is regulated by two primary factors: membrane phospholipid composition and LD-associated proteins.

Rewiring phospholipid metabolism: a synergistic lever for oil accumulation

-

Phospholipids play a crucial role in LD synthesis and oil accumulation through three primary mechanisms. (1) Substrate provision: PA serves as a DAG precursor, while PC supplies acyl groups for the final step of TAG biosynthesis[5]. (2) Structural modulation: As major constituents of ER and LD membranes, phospholipid abundance and composition directly influence LD formation and expansion, where insufficient phospholipid levels elevate interfacial tension (also known as surface tension) and consequently inhibit TAG storage[4]. (3) Membrane remodeling: LPC/PC imbalances induce membrane curvature changes that promote LD budding[7,8]. Notably, PA has been shown to activate the enzyme DGAT1 and consequently enhance TAG synthesis[30], while the fatty acid composition of PC exerts dual regulatory control—indirectly by membrane fluidity-mediated LD biogenesis regulation, and directly by determining storage lipid composition. Given these multifaceted regulatory roles in LD biogenesis, strategic phospholipid metabolic engineering presents greater potential for improving oil content than carbon flux manipulation alone.

Rational phospholipid metabolic engineering optimizes LD phospholipid composition to enhance neutral lipid sequestration capacity. The PC/PE-dominated monolayer surrounding the neutral lipid core critically determines LD stability, dynamics, and organelle interactions. Recent studies implicate phospholipid metabolism in controlling LD size, abundance, and stability, e.g., glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 4 (GPAT4) synthesizes phospholipids essential for LD biogenesis[31]. Targeted engineering of GPAT4 and related enzymes in the phospholipid biosynthetic machinery may alter the phospholipid composition of LDs, thereby influencing neutral lipid sequestration and controlling phase transition behavior critical for TAG core nucleation and stabilization. Additionally, the incorporation of specific unsaturated phospholipids enhances membrane fluidity, facilitating greater neutral lipid storage. This is particularly relevant during stress responses, where LDs sequester cytotoxic free fatty acids from membrane degradation. Optimized phospholipid profiles also improve inter-organelle lipid transfer efficiency, ultimately boosting cellular lipid storage capacity. This approach holds significant biotechnological promise for enhancing oil content in seeds and other plant tissues for biofuel and high-value lipid production.

Synergistic roles of LD-associated proteins in oil accumulation engineering

-

Despite the established significance of LD-associated proteins, only a limited subset of plant LD biogenesis factors has been identified, including oleosin, caleosin, LD-associated protein (LDAP), ABHD1, SEPIN, and SEPIN-interacting proteins (e.g., LDAF, LDAP-interacting protein [LDIP], and VAP27-1). However, overexpression of these proteins does not universally enhance oil content. Overexpression of Arabidopsis OLEOSINs, B. napus OLEOSINs, or Carthamus tinctorius OLEOSINs in Arabidopsis fails to significantly increase seed oil content[32,33]. Caleosin overexpression elevates triacylglycerol (TAG) levels in BY2 cells and Arabidopsis seedlings/leaves but not in seeds[17]. Additionally, LDAP overexpression—while promoting LD synthesis in vegetative tissues—does not alter seed oil content[34]. Thus, although oleosin, caleosin, and LDAP are essential for LD formation, their individual overexpression confers no measurable oil-boosting effects, excluding them as standalone candidates for seed oil metabolic engineering. The limitations of these known proteins necessitate the discovery of novel LD-associated components to expand engineering targets for enhanced lipid accumulation.

State-of-the-art proteomic platforms, particularly high-precision Orbitrap-based mass spectrometry (MS) systems, now facilitate the detection of low-abundance proteins and enable precise quantification across subcellular compartments. Building upon foundational methodologies such as proteomics and interactome mapping, current research emphasizes leveraging advanced implementations of these techniques for deeper mechanistic insights and enhanced engineering capabilities. Significant progress now moves far beyond basic cataloging, as exemplified by high-resolution proteomic profiling using tandem mass tag (TMT)[35], achieving exceptional quantitative depth across specific seed tissues under diverse developmental and stress conditions. Crucially, advances in interactome mapping, such as the integration of in vivo crosslinking with affinity purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS), now allow precise capture of transient and weak interactions on dynamic LD surfaces, revealing elusive regulators of budding and fusion. Furthermore, proximity-dependent biotinylation techniques (e.g., TurboID) optimized for plants offer spatially resolved mapping of LD interaction networks with organelles such as the ER and peroxisomes, providing mechanistic insights into lipid channeling[36]. Integrative structural proteomics, employing hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) and cryo-electron tomography, offers high-resolution views of conformational changes in complexes like the SEIPIN oligomer, linking structure directly to function in lipid packaging[37,38].

Research on LD-associated proteins need not be confined to studies in plants and closely related species; findings from phylogenetically distant species can also be leveraged for improving oil content through plant genetic engineering. Evolutionary conservation analyses through cross-species comparisons have uncovered fundamental principles of LD biology. For instance, the SEIPIN complex, essential for LD initiation, demonstrates remarkable functional conservation from yeast to plants, though plant-specific isoforms exhibit tissue-dependent regulation of LD morphology[24]. Interactome studies have further elucidated the molecular machinery, identifying critical SEIPIN partners like LDAP3 and LDIP that coordinate LD assembly[39]. These findings collectively establish a framework for identifying genetic engineering targets to modulate lipid accumulation. To identify evolutionarily conserved engineering targets, cross-species interactome frameworks are emerging, merging co-fractionation mass spectrometry with deep-learning-powered interaction prediction tools (e.g., AlphaFold-Multimer)[40]. This facilitates translating the Arabidopsis LDAP3-LDIP-SEIPIN interactome network to oilseed crops to pinpoint conserved complex stoichiometry for modulating LD traits.

-

Oils, functioning as hydrophobic storage molecules, achieve phase separation from hydrophilic cytoplasmic components during their biosynthesis and storage processes. The development and enlargement of the LD membrane constitute critical steps in LD biogenesis, requiring coordinated contributions from both LD-associated proteins and phospholipids. This intricate interplay between structural assembly and dynamic regulation provides a molecular toolkit for engineering lipid droplet biogenesis in crops.

Proteins governing LD biogenesis and dynamics have emerged as pivotal tools for enhancing oil content in oilseed crops, offering unique advantages over traditional metabolic engineering approaches. Central to their utility is their ability to directly target the rate-limiting step of TAG sequestration into nascent LDs. Unlike upstream metabolic engineering strategies that compete for carbon substrates and face growth trade-offs, LD-associated proteins enhance TAG storage efficiency by directly optimizing lipid droplet biogenesis, thereby decoupling specialized fatty acid production from bulk oil accumulation. The cross-species functionality of LD proteins broadens their applicability. Animal-derived proteins like CIDEs and FIT2 function effectively in plants, highlighting evolutionary conservation of LD biogenesis mechanisms. This compatibility enables rapid translation of findings across biological systems. Additionally, LD proteins such as LDAP enable oil engineering in non-seed tissues (e.g., leaves or stems), opening avenues for whole-plant lipid production—a potential game-changer for biofuel feedstocks.

Elucidating the molecular mechanisms governing LD biogenesis establishes a transformative framework for oilseed crop improvement, integrating three synergistic engineering dimensions: amplifying substrate flux through enhanced fatty acid biosynthesis, refining TAG assembly efficiency via enzyme optimization, and dynamically regulating LD membrane architecture via phospholipid remodeling. This systems-level strategy transcends conventional approaches by synchronously addressing metabolic bottlenecks in substrate supply, catalytic capacity, and storage compartmentalization. Such multidimensional engineering creates a self-reinforcing metabolic circuit that pushes carbon flux into storage lipids while expanding LD storage potential, thereby achieving yield maximization without compromising cellular homeostasis. Crucially, this paradigm shift from isolated pathway manipulation to holistic network reprogramming redefines oilseed bioengineering, positioning LD-centric strategies as both a mechanistic probe and a scalable solution for sustainable crop enhancement.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 32400256 and 32170593), the Guangdong Provincial Pearl River Talent Plan (Grant No. 2019QN01N108), and the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant Nos 2020B1515020007, 2023A1515011810, and 2025A1515011168).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Du C, Gao C, Zhang Z; draft manuscript preparation: Du C, Gao C, Zhang Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Du C, Gao C, Zhang Z. 2025. Optimizing lipid droplet dynamics for enhanced triacylglycerol storage in oilseed crops. Seed Biology 4: e014 doi: 10.48130/seedbio-0025-0014

Optimizing lipid droplet dynamics for enhanced triacylglycerol storage in oilseed crops

- Received: 14 April 2025

- Revised: 11 July 2025

- Accepted: 08 August 2025

- Published online: 02 September 2025

Abstract: Oilseeds serve as critical sources of both edible oils and industrial raw materials. Triacylglycerol (TAG), the predominant storage lipid in oilseeds, is synthesized during seed development and subsequently stored within specialized organelles called lipid droplets (LDs). These LDs are formed through phase separation at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, where a core of neutral lipids becomes encapsulated by a phospholipid monolayer embedded with various proteins. The processes of LD formation, budding, and growth are regulated by both lipid composition and associated protein factors. Recent studies have revealed that LD formation acts as a rate-limiting step for oil accumulation in developing seeds. This discovery presents promising opportunities for genetic engineering approaches aimed at enhancing oil content in oilseeds through the targeted regulation of LD biogenesis. Future research efforts will focus on optimizing lipid metabolism and LD formation dynamics using advanced proteomic profiling and interactome mapping techniques. These advancements may establish novel strategies for improving oilseed crops to meet growing demands in both nutritional and industrial applications.

-

Key words:

- Lipid droplets /

- Oilseed crops /

- Oil content /

- Bioengineering