-

Vitis vinifera, a widely cultivated grape species within the family Vitaceae, is primarily used in wine production[1]. The skin of these grapes hosts a diverse array of region-specific microbial communities, including a broad spectrum of indigenous yeasts[2]. These yeasts, comprising both Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces species, play essential roles throughout the winemaking process[3−5]. Wine fermentation progresses in a sequential manner, with non-Saccharomyces yeasts predominating during the initial stages. In the later stages, Saccharomyces cerevisiae becomes dominant due to its superior tolerance to ethanol[6].

Beyond their fermentative roles, yeasts have recently gained attention for their potential health-promoting properties, particularly as probiotics[7]. The most studied probiotics are lactic acid bacteria (LAB), such as Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Streptococcus spp., Bacillus spp., and Enterococcus spp., all of which are typically consumed via fermented foods[8−11]. Probiotics are defined as live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit to the host regardless of the site of action or mode of administration[10]. These benefits include enhanced gut barrier function, immune modulation, prevention of gastrointestinal and urogenital infections, and cancer risk reduction[12,13]. According to the regulations of the Food and Drug Administration (USA), probiotic microorganisms must be present in foods at a concentration of at least 106 CFU g−1 to be effective, while freeze-dried supplements typically deliver between 107–1011 CFU g−1 viable microorganisms per day[14,15].

Although most probiotics are bacterial, yeasts have also emerged as promising candidates[14,16−18]. Fernández-Pacheco et al.[16] and Vilela et al.[17] reported that both Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeasts isolated from wine and similar food products display promising probiotic characteristics. For instance, S. cerevisiae strains isolated from tibicos, a traditional Mexican fermented beverage, have demonstrated potential probiotic properties such as acid and bile salt tolerance, auto-aggregation capability, and antioxidant potential[18]. S. cerevisiae is commonly used in baking and brewing[14], whereas S. boulardii, a closely related variety, is the only yeast species widely commercialized as a probiotic[14]. Studies have shown that both Saccharomyces strains can adapt to the host's physiological conditions[14,16−18]. Notably, S. boulardii exhibits key probiotic characteristics such as resistance to gastric acidity, survival at low pH, and optimal growth temperature, contributing to its effectiveness as a probiotic[14]. In addition to their probiotic properties, yeasts are also recognized for their antioxidant activity, which is mainly attributed to the high content of (1→3)-β-D-glucan in the cell wall and antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and catalase[19,20]. Antioxidants help to neutralize free radicals and reduce oxidative stress, thereby playing a crucial role in disease prevention[21].

Given the dual role of yeasts in both fermentation and potential health promotion, the present study aims to evaluate the probiotic and antioxidant potential of Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeast strains isolated from Sri Lankan grape skin and wine samples by Thivijan et al.[4]. The strains used in this study include Hanseniaspora opuntiae J1Y-T1 (NCBI Accession Number: OP143841), H. uvarum JF3-T1N (NCBI Accession Number: PQ169565), Saccharomyces boulardii JSB-T2 (NCBI Accession Number: OR363102), and Starmerella bacillaris WMP4-T4 (NCBI Accession Number: OP890585). While the wine fermentation characteristics of these strains have been previously characterized[4], their health-promoting probiotic properties remain unexplored. By characterizing their functional attributes, this study contributes to the emerging field of functional fermentation microbiology[16,17] and highlights the untapped potential of indigenous yeasts in developing health-promoting foods and beverages.

-

Yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) agar, bile salts (Oxgall), Sodium Chloride (NaCl), Hydrochloric acid (HCl), phenol, Potassium chloride (KCl), Calcium chloride (CaCl2), Sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), α-amylase, lysozyme, and pancreatic enzymes were procured from Sigma Aldrich, UK. All chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade (99.7% purity). All the culture media used here were of microbiological grade and purchased from HiMedia, India.

Microorganisms

-

The Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeast strains identified by Thivijan et al.[4], from the skin of Vitis vinifera L., along with ATCC foodborne pathogen strains used in this study, were obtained from the microbial culture bank of the Faculty of Technology, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka.

Tolerance for various physicochemical conditions

-

For tolerance assays, stock cultures of Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeast strains were streaked onto YPD agar plates and incubated at 30 °C for 24–48 h. To prepare yeast suspensions for the assays, individual colonies were collected after three consecutive streakings and adjusted to McFarland standard 2 using sterile distilled water in test tubes. These suspensions were then inoculated into YPD broth supplemented with various gastrointestinal physicochemical test conditions, as described below. The modified YPD broth inoculated with yeast cultures was incubated at 37 °C for the required duration.

To assess viability, cultures were sampled at specified time intervals, serially diluted, and plated onto YPD agar. The plates were incubated at 30 °C for 24–48 h, after which colony-forming units (CFU mL−1) were determined to evaluate survival rates. Initial and subsequent colony counts were recorded hourly for up to 4 h for pH, bile salt, NaCl, and phenol tolerance assays. All experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility and statistical reliability.

Bile salt tolerance

-

To determine bile salt tolerance, freshly prepared and sterilized YPD broth was supplemented with 0.3% and 0.5% (w/v) bile salts (Oxgall). A volume of 1,000 μL of yeast suspension, adjusted to McFarland standard 2, was inoculated into 10 mL of bile salt-supplemented YPD broth, and the survival rate was calculated accordingly[22].

pH tolerance

-

To determine the pH tolerance, a volume of 1,000 μL of yeast suspension, adjusted to McFarland standard 2, was inoculated into pH-adjusted 10 ml sterilized YPD broth (pH 2.0 and 3.0 using 1 M HCl)[23]. The survival rate was calculated for each strain.

Phenol tolerance

-

To assess phenol tolerance, a volume of 1,000 μL of yeast suspension, adjusted to McFarland standard 2, was inoculated into 10 mL of 0.4% and 0.6 % phenol (w/v) added to sterilized YPD broth[24]. The survival rate was calculated for each strain.

NaCl tolerance

-

To determine NaCl tolerance, a volume of 1,000 μL of yeast suspension, adjusted to McFarland standard 2, was inoculated into 10 mL of sterilized YPD broth supplemented with 3.0 % and 6.0 % NaCl (w/v)[23]. The survival rate was calculated for each strain.

Temperature tolerance

-

Yeast tolerance to different temperatures was evaluated by inoculating 1,000 μL of yeast suspension, adjusted to McFarland standard, into 10 mL of sterilized YPD broth and incubating at 4, 20, 37, 45, and 60 °C for 24 h. The survival rate of each yeast strain was calculated after the incubation time[25].

Tolerance in artificial saliva juice (ASJ)

-

Yeast tolerance to ASJ was determined by inoculating 1 mL of yeast suspension (McFarland standard 2) into 5 mL of ASJ mixture containing 0.62% NaCl, 0.22% KCl, 0.022% CaCl2, 0.12% NaHCO3, 0.30% α-amylase, and 100 ppm lysozyme at pH 6.9. The mixture was then incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 5 min[10]. Viable colony counts were determined before and after incubation using serial dilution. The survival rate of each yeast strain was then calculated based on the viable counts after the incubation period.

Tolerance in simulated gastric juice (SGJ)

-

To assess yeast tolerance to SGJ, a solution containing 0.30% NaCl, 0.11% KCl, 0.015% CaCl2, 0.06% NaHCO3, and 0.30% porcine stomach mucosa pepsin at pH 2.0 was prepared. Yeast suspensions previously incubated in ASJ were transferred into the prepared 5 mL SGJ and incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 120 min[10]. Viable colony counts were then determined using serial dilution to evaluate survival under SGJ. Based on the obtained viable colony counts, the survival rate of each yeast strain was calculated.

Tolerance in simulated intestinal juice (SIJ)

-

To determine yeast tolerance to SIJ, a solution containing 0.50% NaCl, 0.06% KCl, 0.03% CaCl2, 0.06% NaHCO3, 0.30% Ox-gall, and 0.10% pancreatic enzymes at pH 7.0 was prepared. Yeast suspensions previously incubated in SGJ were transferred to 5 mL of SIJ and incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 120 min[10]. Colony counts based on serial dilution were used to determine the survival rate under SIJ conditions.

Survival rate

-

To determine the survival rate of each yeast strain during the tolerance assays, colony-forming units (CFU mL−1) were recorded and calculated using the following Eq. (1).

${\mathrm {Survival}}\; {\mathrm{Rate}}\; ({\text{%}}) = \left(\dfrac{\mathrm{N}2}{\mathrm{N}1}\right)\times 100 $ (1) Where, N1 = Initial CFU count before the treatment, N2 = CFU count after the treatment (at specific time intervals).

Cell surface characteristics of yeast strains

-

Overnight cultures of Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeast strains grown in YPD broth were harvested and transferred into 2 mL sterile Eppendorf tubes, then centrifuged (Model Z-216 M, Hermle Labortechnik GmbH, Germany) at 5,000 g-force for 10 min at 25 °C to pellet the cells[10]. The resulting pellets were washed with sterile distilled water to remove any residual media components. Finally, the yeast pellets were resuspended in sterile distilled water to prepare a uniform yeast cell suspension in test tubes, adjusted to a McFarland standard 2, for subsequent analyses.

Cell surface hydrophobicity

-

To evaluate cell surface hydrophobicity, the optical density (OD) of the yeast suspension was adjusted to approximately 0.7 at 600 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS10, Waltham, MA, USA). Then, 3 mL of the prepared yeast suspension was mixed separately with 1 mL of xylene and 1 mL of hexane in a sterile test tube. The mixtures were vortexed at 2,000 rpm for 60 s. After mixing, the samples were incubated undisturbed at 37 °C for 1 h to allow phase separation. Following incubation, the absorbance of the aqueous layers was measured at 600 nm[26]. The hydrophobicity percentage was calculated using the following Eq. (2).

$ {\mathrm{Hydrophobicity}}\; ({\text{%}}) = \dfrac{\mathrm{A}1-\mathrm{A}2}{\mathrm{A}1}\times 100 $ (2) Where, A1: Absorbance of the yeast suspension before adding the hydrocarbon, A2: Absorbance of the aqueous layer after 1 h of incubation with the hydrocarbon.

Auto-aggregation

-

The initial absorbance of prepared yeast suspensions was measured at 600 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS10, Waltham, MA, USA). Afterwards, the yeast suspension was incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured hourly for up to 4 h at 600 nm to check the aggregation over time. The cellular auto-aggregation percentage was calculated using the following Eq. (3)[26].

${\mathrm{ Auto}}{\text-}{\mathrm{aggregation}}\; ({\text{%}}) = \dfrac{\mathrm{A}1-\mathrm{A}2}{\mathrm{A}1}\times 100 $ (3) Where, A1: Initial absorbance of the yeast suspension, A2: Absorbance of the supernatant after each hour of incubation.

Antibacterial properties of yeast strains

-

Selected food pathogens, including Bacillus cereus (ATCC 11778), Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212), Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC 13883), Listeria monocytogenes (ATCC 51776), Proteus vulgaris (ATCC 29905), Salmonella typhi (ATCC 6539), and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923) were used for the assay. The antimicrobial activity of the yeasts was evaluated using the disk diffusion method described by Pavalakumar et al.[10]. All four yeast strain suspensions were prepared to match McFarland standard 2, while pathogen suspensions were adjusted to McFarland standard 0.5. The pathogens were streaked onto Mueller-Hinton agar plates, and sterile discs loaded with 20 µL of yeast suspension were placed on the agar surface. After 48 h of incubation at 30 °C, the diameter of the inhibition zones, including the disc, was measured using a digital Vernier caliper. Ampicillin (100 ppm) was used as the positive control, and distilled water served as the negative control instead of yeast culture.

Antifungal sensitivity of yeast strains

-

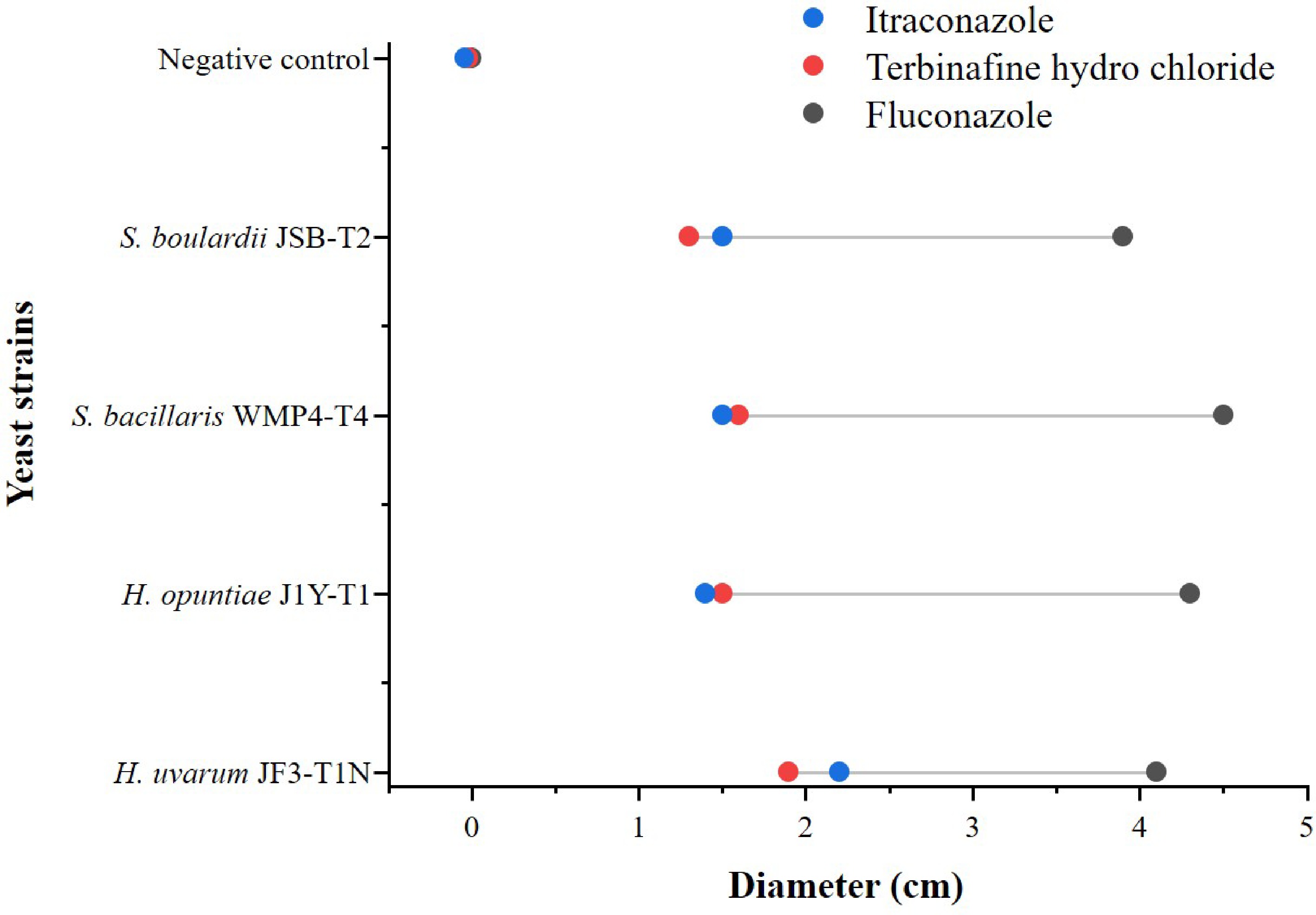

The antifungal activity of the yeast strains was assessed using the disk diffusion method. Three antifungal agents, Itraconazole, Fluconazole, and Terbinafine hydrochloride, were tested at a 100 ppm concentration. Sterilized discs (5 mm diameter) were dipped in prepared antifungal solutions (20 µL for each disc) and then placed on the previously spread yeast suspension (McFarland 2) on YPD agar. Then the plates were incubated aerobically at 30 °C for 48 h. The diameters of the inhibition zones around the antifungal discs were measured using a digital vernier caliper[16].

Antioxidant properties

-

Yeast suspensions were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 g-force for 10 min at 25 °C. The resulting pellets were washed twice with sterile distilled water to remove residual media components. The cell density was then adjusted to the 0.5 McFarland standard. Antioxidant activities were evaluated using four spectrophotometric methods with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS10, Waltham, MA, USA). All assays were conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility and statistical reliability.

ABTS radical scavenging activity

-

A prepared yeast suspension (0.4 mL) was mixed with 3 mL of freshly prepared 2,2'-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) reagent and kept at room temperature (28 °C) in the dark for 6 min. The mixture was then centrifuged at 2,000 g-force for 5 min. The absorbance of the resulting supernatant was measured at 734 nm. A mixture of distilled water and ABTS reagent was used as the control[27]. ABTS scavenging activity was determined using Eq. (4).

${ \mathrm {ABTS\;scavenging\; activity}}\; \left({\text{%}}\right)=\dfrac{\mathrm{Ac}-{\mathrm{As}}}{\mathrm{Ac}}\,\times100 $ (4) where, Ac: Absorbance of control, As: Absorbance of sample.

DPPH radical scavenging activity

-

Equal volumes of yeast suspension (1 mL) and freshly prepared 0.02 mM 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) ethanol reagent (1 mL) were mixed and kept at room temperature (28 °C) in the dark for 30 min. The mixture was then centrifuged at 2,000 g-force for 10 min. After centrifugation, the absorbance of the resulting supernatant was measured at 517 nm. A mixture of distilled water and DPPH ethanol reagent was used as the control, while a mixture of yeast suspension and ethanol served as the blank. DPPH radical scavenging activity was determined using Eq. (5)[28].

$ {\mathrm{DPPH\; scavenging\; activity}}\; ({\text{%}}) = 1-\dfrac{(\mathrm{A}\mathrm{s}-\mathrm{A}\mathrm{b})}{\mathrm{A}\mathrm{c}}\times 100 $ (5) Where, Ab: Absorbance of the blank, Ac: Absorbance of the control, As: Absorbance of the sample.

Total phenolic content

-

To evaluate total phenolic content (TPC), 1 mL of yeast suspension was added to 5 mL of 10% (v/v) Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and kept at room temperature (28 °C) for 5 min. Then, 4 mL of 7.5% (w/v) Na2CO3 solution was added and mixed. The mixture was kept in the dark at room temperature (28 °C) for 1 h. The absorbance was then measured at 765 nm. Gallic acid was used as the standard, and the control was prepared using distilled water and Folin–Ciocalteu reagent[29]. To build the standard curve, different concentrations of gallic acid (0.02, 0.04, 0.06, 0.08, and 0.1 mg·mL−1) were used.

FRAP assay

-

A 100 µL aliquot of yeast solution was mixed with 3 mL of freshly prepared ferric-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) and kept at room temperature (28 °C) in the dark for 6 min. After incubation, the absorbance was measured at 593 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as the standard, and the FRAP reagent alone served as the control. To build the standard curve, different concentrations of ascorbic acid (0.002, 0.008, 0.01, 0.02, and 0.04 mg·mL−1) were used[30].

Statistical analysis

-

Data from the probiotic characterization experiments were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and significant differences were identified using Tukey's post hoc test at a 95% confidence level with IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 software. Heat maps and other graphical representation charts were created using Origin 2025 software.

-

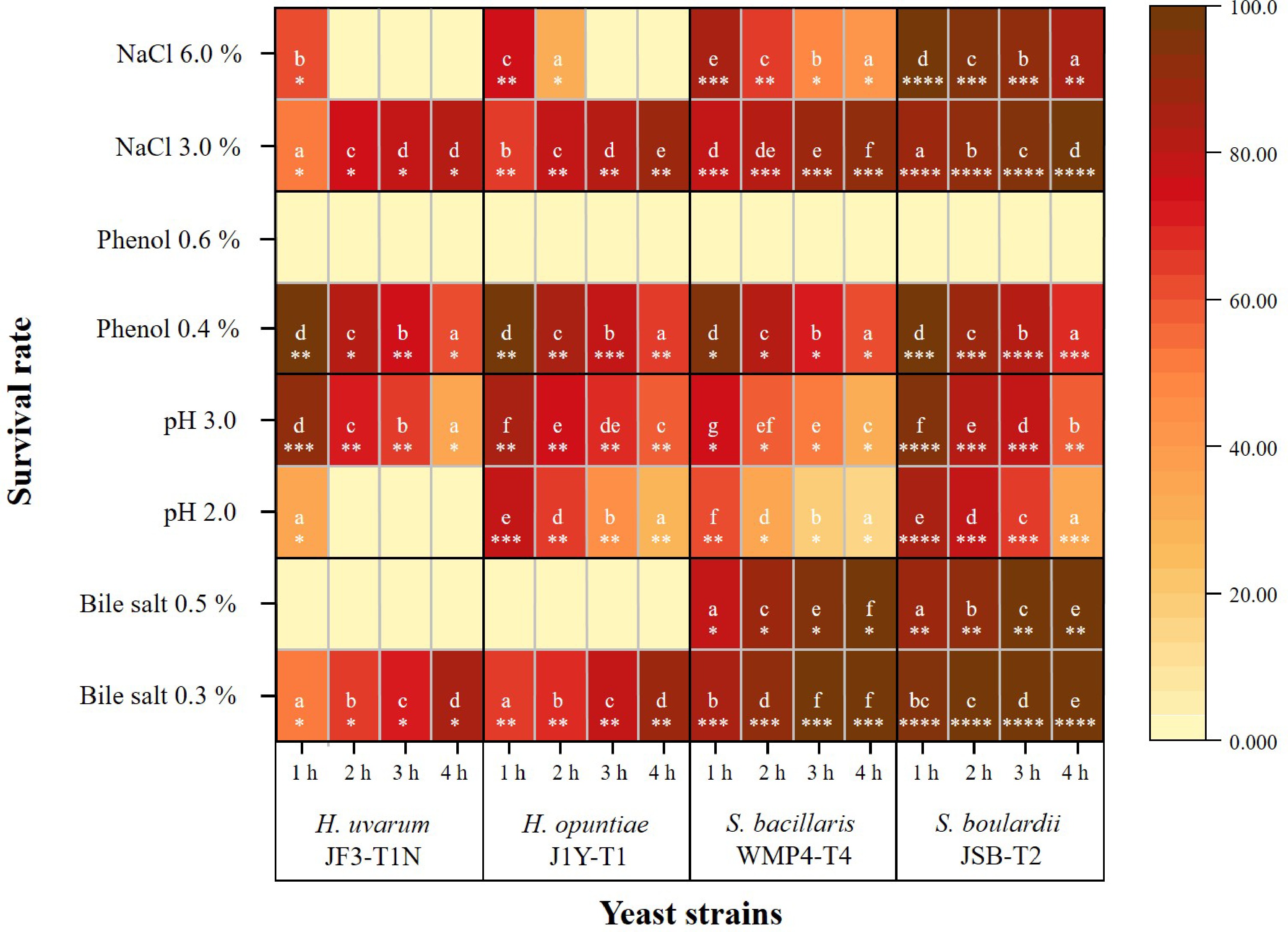

The selected Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeast strains demonstrated significant survival under the tested gastrointestinal conditions. At a bile salt concentration of 0.3% (Fig. 1), all strains exhibited increased survival rates over the 4 h period. S. boulardii JSB-T2 showed the highest tolerance, with survival nearing 100%, indicating not only strong resistance but also potential proliferation under bile salt stress. S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 also demonstrated high survival, reaching 99.17% ± 0.74% after 4 h. Although H. uvarum JF3-T1N showed the lowest tolerance at 0.3% bile salts, its survival still increased to 86.09% ± 0.94% by the fourth hour.

Figure 1.

Heatmap of the survival rates of selected yeast strains under various in vitro gastrointestinal conditions (including different concentrations of bile salts, pH levels, phenol, and NaCl). Color intensity ranges from light yellow (low survival) to dark brown (high survival). Distinct alphabetical letters indicate statistically significant differences within a strain across different concentrations or treatment levels over a 1–4 h period. The different counts of asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant differences between strains exposed to the same condition at a given time point, based on a 95% confidence level.

At a higher bile salt concentration (0.5%), a notable reduction in survival was observed across all strains compared to 0.3%, with significant differences in strain-specific tolerance. S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 and S. boulardii JSB-T2 displayed strong resistance at both concentrations. In contrast, H. uvarum JF3-T1N and H. opuntiae J1Y-T1 exhibited complete growth inhibition under 0.5% bile salts, with no viable cells detected throughout the assay.

Compared to their overall pH tolerance, the selected strains showed significant differences in survival under acidic conditions over time (p < 0.05; Fig. 1). All strains exhibited a marked reduction in survival at pH 2.0 compared to pH 3.0. Among the tested strains, S. boulardii JSB-T2 demonstrated the highest acid tolerance, maintaining survival rates of 94.56% ± 0.84% at pH 3.0 and 84.17% ± 1.65% at pH 2.0 after 1 h, substantially outperforming the non-Saccharomyces yeasts.

In contrast, S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 showed the lowest acid tolerance at pH 3.0, with viability decreasing from 75.65% ± 0.59% to 31.76% ± 0.6% over 4 h. At pH 2.0, all strains experienced further viability loss over time. Notably, H. uvarum JF3-T1N exhibited the lowest tolerance, with complete loss of viability (0% survival rate) after just 1 h at pH 2.0. Despite these differences, a general time-dependent decline in survival was observed across all strains under acidic conditions.

Phenol tolerance at 0.4% also varied significantly among strains (p < 0.05; Fig. 1). After 1 h of exposure, all strains maintained relatively high survival. S. boulardii JSB-T2 showed the highest survival (98.51% ± 0.28%), followed by H. opuntiae J1Y-T1 and H. uvarum JF3-T1N, each with approximately 97% survival. S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 exhibited the lowest survival at this time point. By the fourth hour, survival declined across all strains, though S. boulardii JSB-T2 remained the most tolerant (68.39% ± 1.96%). In contrast, H. uvarum JF3-T1N and S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 had the lowest survival rates, around 61%. None of the strains survived at the higher phenol concentration of 0.6%.

At 3.0% NaCl, statistical analysis revealed significant differences (p < 0.05) in survival among strains over time (Fig. 1). A general increase in survival was observed. S. boulardii JSB-T2 had the highest survival, rising from 87.38% ± 0.34% at 1 h to 97.27% ± 0.09% at 4 h. Among the non-Saccharomyces strains, H. uvarum JF3-T1N showed the lowest survival (52.56% ± 0.62% to 81.47% ± 0.03%), while S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 exhibited the highest tolerance, and H. opuntiae J1Y-T1 showed intermediate resistance.

At a higher NaCl concentration (6.0%), all strains exhibited a decline in survival over time. Despite the increased osmotic stress, S. boulardii JSB-T2 maintained high tolerance, with survival decreasing from 98.60% ± 0.21% at 1 h to 85.02% ± 0.99% at 4 h. Among the non-Saccharomyces strains, S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 again showed the highest salt tolerance, while H. uvarum JF3-T1N remained the least tolerant.

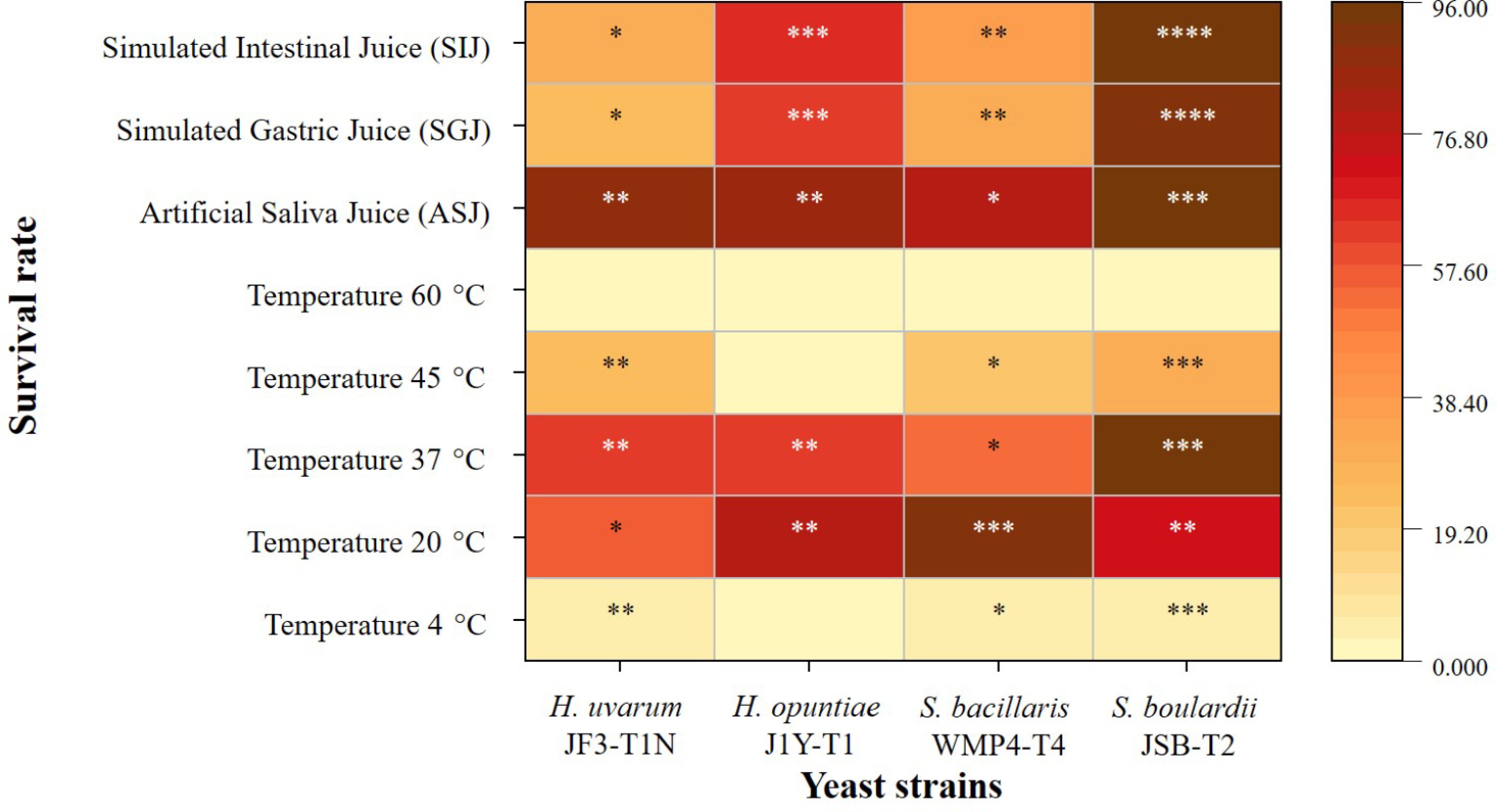

When comparing the thermal tolerance of Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeast strains across various temperatures, significant differences in survival rates were observed among the strains (p < 0.05; Fig. 2). The highest survival was recorded at 37 °C, where S. boulardii JSB-T2 exhibited the greatest viability at 94.67% ± 0.89%, while S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 showed a comparatively lower survival rate of 52.64% ± 0.29%.

Figure 2.

Heatmap of the survival rates of selected yeast strains under various temperatures and simulated gastrointestinal conditions. Color intensity ranges from light yellow (low survival) to dark brown (high survival). The different counts of asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant differences between strains exposed to the same condition at a given time point, based on a 95% confidence level.

At the lowest temperature tested (4 °C), all strains demonstrated reduced viability. S. boulardii JSB-T2 again had the highest survival at 6.03% ± 0.28%, followed by H. uvarum JF3-T1N at 5.22% ± 0.54%. H. opuntiae J1Y-T1 exhibited no viability at this temperature. At 20 °C, representing ambient conditions, all strains showed improved survival compared to 4 °C. Specifically, S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 achieved the highest survival rate at 91.03% ± 0.82%, while H. uvarum JF3-T1N had the lowest.

At 45 °C, S. boulardii JSB-T2 once again demonstrated the highest thermal tolerance, followed by H. uvarum JF3-T1N and S. bacillaris WMP4-T4. However, H. opuntiae J1Y-T1 was inhibited at this elevated temperature. At 60 °C, none of the yeast strains survived.

Figure 2 also highlights significant differences (p < 0.05) among the yeast strains under simulated gastrointestinal conditions. All tested strains displayed high viability in ASJ, indicating strong resistance to the initial oral digestive environment. S. boulardii JSB-T2 showed the highest survival rate (94.10% ± 1.07%), while S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 exhibited the lowest (78.95% ± 0.98%), suggesting strain-specific differences in lysozyme tolerance.

Exposure to SGJ led to a significant reduction in viability across all strains (p < 0.05), reflecting differential tolerance to gastric stress. Nonetheless, S. boulardii JSB-T2 maintained the highest survival (89.89% ± 1.09%), demonstrating strong acid and pepsin resistance.

Under SIJ conditions, which mimic the enzymatic environment of the small intestine, survival rates slightly increased relative to SGJ. S. boulardii JSB-T2 again showed the highest viability (85.95% ± 0.86%), while H. uvarum JF3-T1N recorded the lowest. Among the non-Saccharomyces strains, H. opuntiae J1Y-T1 exhibited the highest survival in both SGJ and SIJ conditions (62%–65%), followed by S. bacillaris WMP4-T4.

Despite a general reduction in viability under SGJ and SIJ conditions, all yeast strains survived to varying extents in the tested gastrointestinal juices, highlighting their potential probiotic capabilities.

Cell surface characteristics of yeast strains

-

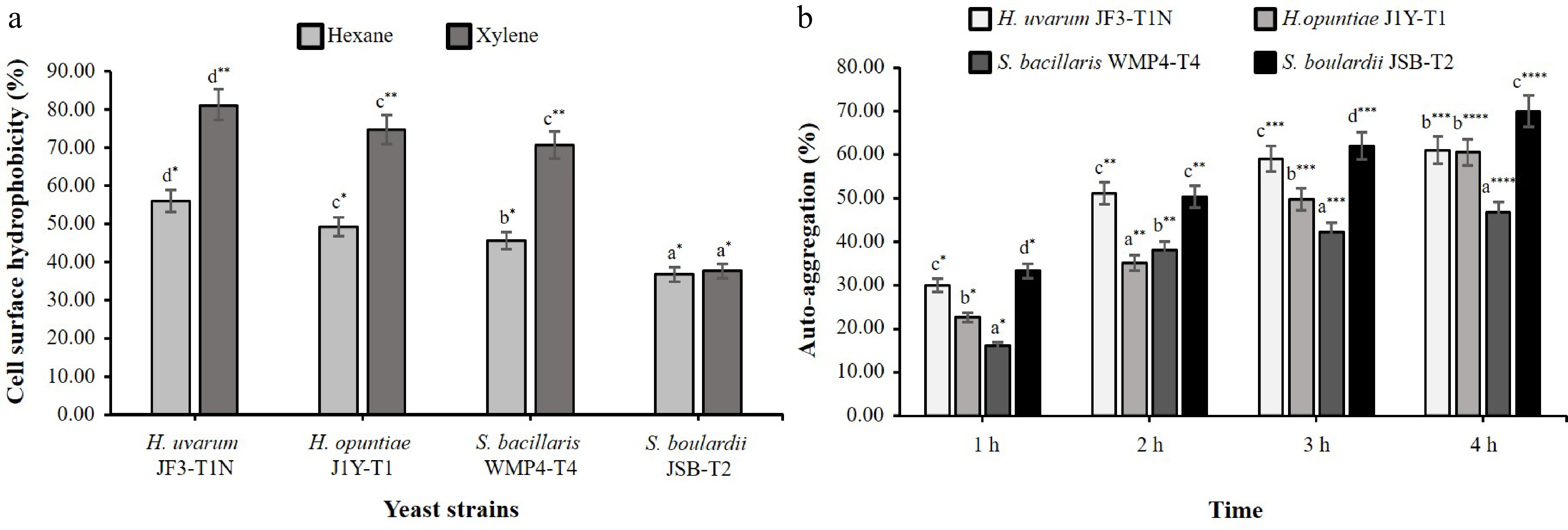

Figure 3a illustrates that H. uvarum JF3-T1N exhibited the highest hydrophobicity in both hexane and xylene assays, with values of 56.05% ± 2.23% and 81.21% ± 4.71%, respectively, indicating a strong capacity to interact with hydrophobic substrates. In contrast, H. opuntiae J1Y-T1 and S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 displayed moderate hydrophobicity, while S. boulardii JSB-T2 demonstrated the lowest levels of hydrophobic interaction. Notably, all strains showed significantly higher hydrophobicity in xylene compared to hexane.

Figure 3.

Cell surface characteristics of selected yeast strains. (a) Hydrophobicity with different organic solvents. (b) Auto-aggregation ability over a 1–4 h period. Different alphabetical letters indicate statistically significant differences between strains and different counts of asterisks (*) denote significant differences between tested conditions within the same strain at a 95% confidence interval.

In the auto-aggregation assay (Fig. 3b), the percentage of auto-aggregation increased significantly across all strains over the 4 h incubation period (p < 0.05). S. boulardii JSB-T2 exhibited the highest auto-aggregation capacity at 70.04% ± 4.26%. H. uvarum JF3-T1N and H. opuntiae J1Y-T1 showed moderate auto-aggregation levels, while S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 had the lowest aggregation capacity.

Antibacterial activity

-

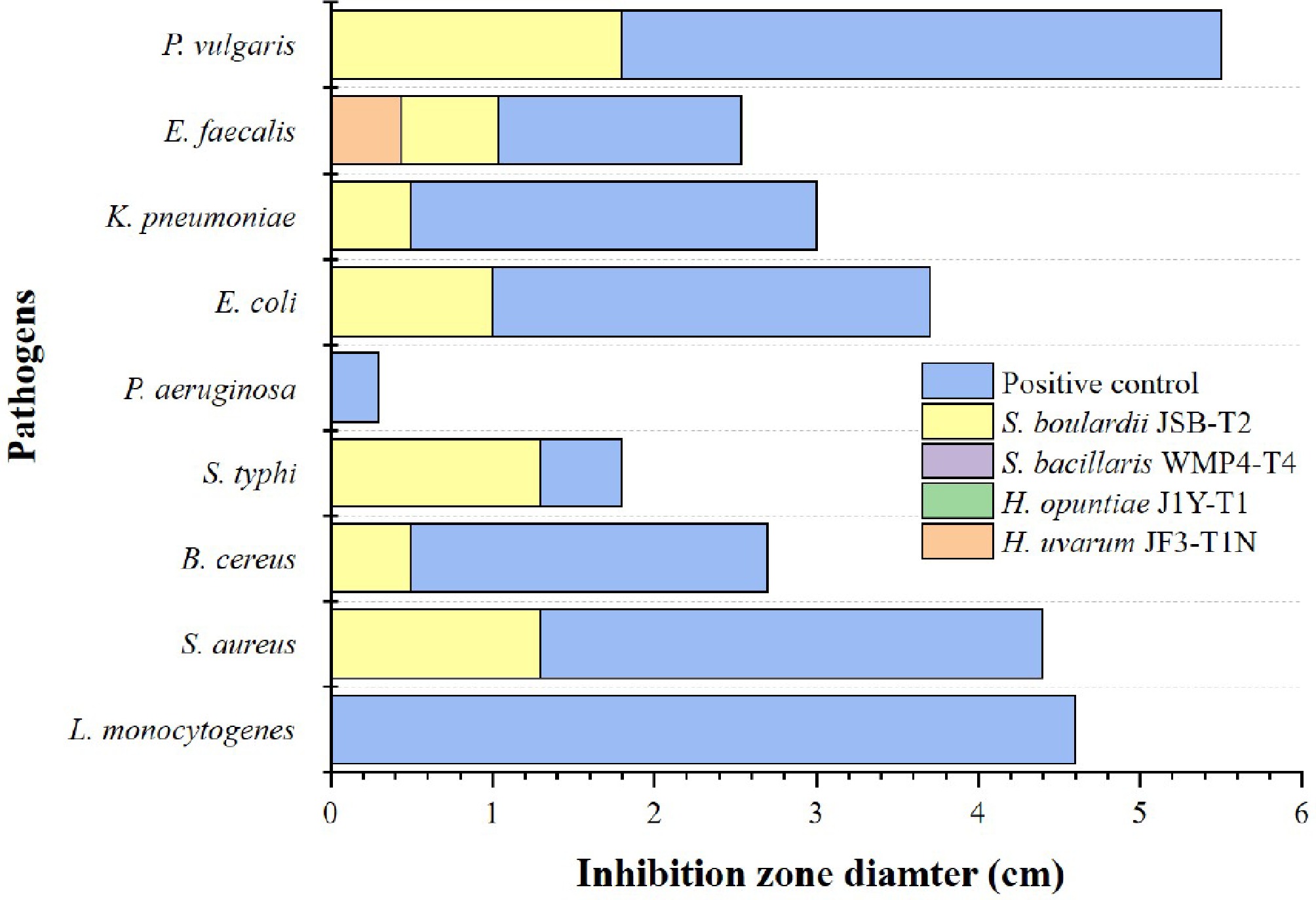

In comparing the antibacterial activity of Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeast strains, only S. boulardii JSB-T2 exhibited significant inhibitory effects, whereas S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 and H. opuntiae J1Y-T1 showed no activity against any of the tested pathogens (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Antibacterial activity of selected yeast strains against different foodborne pathogens. Different colours indicate the tested yeast strains. Ampicillin was used as the positive control.

S. boulardii JSB-T2 demonstrated significant antibacterial activity (p < 0.05) against S. aureus, B. cereus, S. typhi, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, E. faecalis, and P. vulgaris. Among these, the largest inhibition zone was observed against P. vulgaris (1.87 ± 0.33 cm), while the smallest zones were recorded for B. cereus and K. pneumoniae (0.50 ± 0.33 cm). In contrast, among the non-Saccharomyces strains, only H. uvarum JF3-T1N exhibited inhibitory activity, which was limited to the pathogen E. faecalis. None of the tested yeast strains exhibited antibacterial effects against L. monocytogenes or P. aeruginosa.

Antifungal sensitivity

-

Susceptibility to the three selected antifungal agents, as shown in Fig. 5, varied significantly among the tested yeast strains (p < 0.05). Fluconazole demonstrated the strongest inhibitory effect across all strains, indicating a general susceptibility. Among them, S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 exhibited the highest sensitivity to this antifungal agent.

Figure 5.

Antifungal sensitivity of selected yeast strains. Different colours indicate different antifungal agents.

With terbinafine hydrochloride, S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 again showed the greatest susceptibility, followed by H. uvarum JF3-T1N. However, with itraconazole, H. uvarum JF3-T1N displayed the highest susceptibility, while H. opuntiae J1Y-T1 exhibited the greatest resistance among the tested strains. Therefore, although the tested yeast strains showed a mixed response to the selected antifungal agents, they were generally more susceptible than resistant.

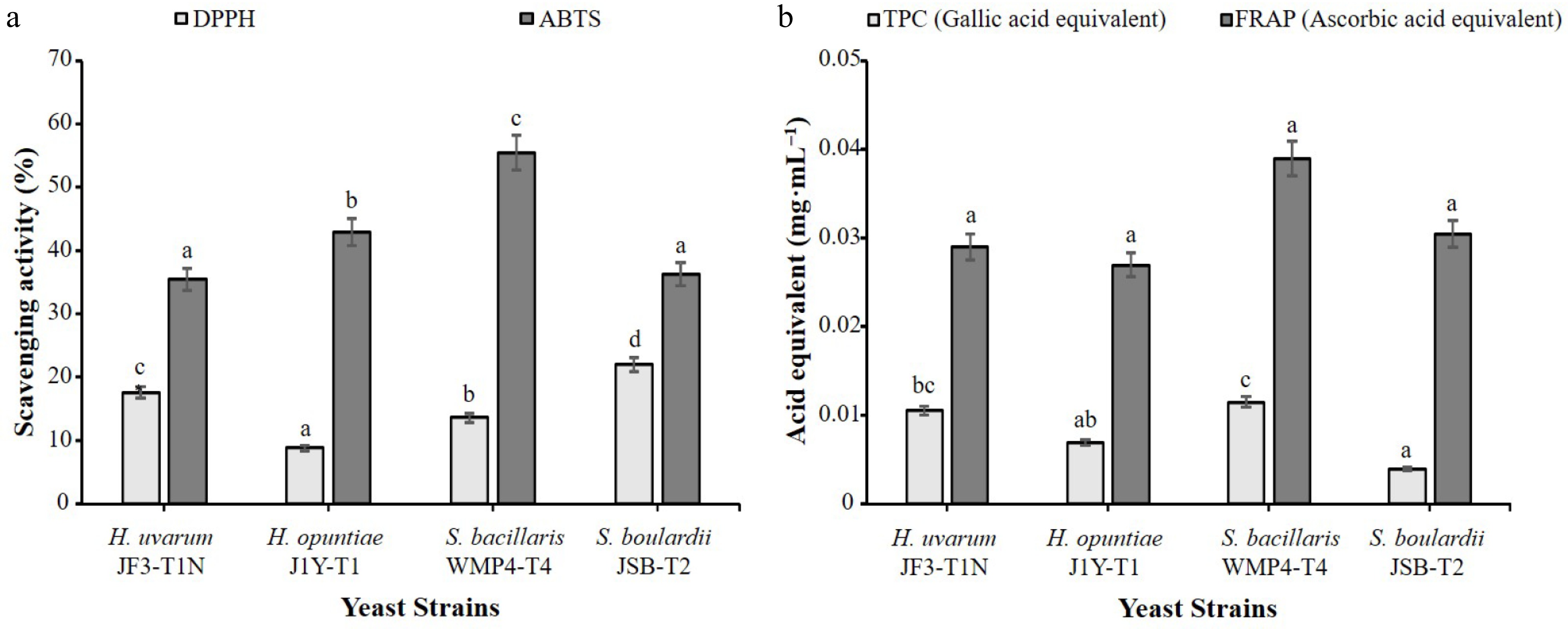

Antioxidant activity

-

Figure 6 illustrates the antioxidant properties of selected Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeast strains. According to the obtained results, significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed in their ABTS radical scavenging activity. S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 exhibited the highest ABTS scavenging activity (55.49% ± 0.32%), followed by H. opuntiae J1Y-T1 (42.92% ± 0.15%), while H. uvarum JF3-T1N showed the lowest activity. In the DPPH radical scavenging assay (Fig. 6a), S. boulardii JSB-T2 showed the highest activity (22.02% ± 0.41%), followed by H. uvarum JF3-T1N, whereas H. opuntiae J1Y-T1 exhibited the lowest activity.

Figure 6.

Antioxidant properties of selected yeast strains. (a) Free radical scavenging activity shown as the percentage of scavenging in DPPH and ABTS assays. (b) Antioxidant capacity expressed as ascorbic acid equivalents in the FRAP assay and gallic acid equivalents in the TPC assay. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Different alphabetical letters indicate statistically significant differences among strains at a 95% confidence interval for the specific test.

As depicted in Fig. 6b, significant differences in TPC were observed among the strains (p < 0.05). S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 recorded the highest TPC (0.0115 ± 0.0005 mg·mL−1), followed by H. uvarum JF3-T1N (0.0105 ± 0.0016 mg·mL−1), while H. opuntiae J1Y-T1 and S. boulardii JSB-T2 showed lower TPC values. Although S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 also demonstrated the highest FRAP value (0.039 ± 0.001 mg·mL−1), followed by S. boulardii JSB-T2 (0.031 ± 0.001 mg·mL−1), the differences in FRAP values among all strains were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

-

The current study presents a comprehensive evaluation of the probiotic potential of selected Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeast strains by assessing their tolerance to various physicochemical stresses, simulated gastrointestinal conditions, cell surface properties, antimicrobial and antifungal activity, as well as antioxidant potential.

Strain and time-dependent responses were consistently observed across tolerance assays, cell surface characterizations, and antioxidant evaluations. All tested strains demonstrated the ability to withstand physiological bile concentrations of approximately 0.3%, commonly found in the human small intestine[31], suggesting their basic capacity to survive gastrointestinal transit. However, differences in bile salt tolerance at elevated concentrations revealed strain-specific variability. S. boulardii JSB-T2 and S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 exhibited high tolerance even at 0.5% bile salt, indicating superior adaptability under bile stress and supporting their candidacy as promising probiotics. In contrast, H. uvarum JF3-T1N and H. opuntiae J1Y-T1 were completely inhibited at 0.5%, underscoring their limited potential where higher bile resistance is essential.

Low pH tolerance is critical for surviving gastric transit, given that stomach pH ranges from 1.0 (fasting) to 4.5 (postprandial) and exposure can last up to 3 h[10]. As supported by previous studies[32], acidic conditions impair glucose uptake and ethanol production in yeasts. Despite this, S. boulardii JSB-T2 demonstrated high survival at low pH, emphasizing its acid tolerance and aligning with findings from earlier reports advocating the use of acid-resistant yeasts for probiotic and functional food applications[33,34]. Contrastingly, according to Menezes et al.[20], Saccharomyces spp. and non-Saccharomyces strains such as Hanseniaspora spp. both showed similarly high tolerance to low pH and bile salts.

The phenol tolerance assay indicated that while all strains could survive 0.4% phenol, 0.6% was toxic. Phenol, a by-product of amino acid degradation in the gut, can inhibit DNA synthesis and cell proliferation in yeast[35,36]. S. boulardii JSB-T2 again showed superior phenol resistance, a critical feature for survival in the gut environment.

In the NaCl tolerance assay, all strains demonstrated increasing tolerance up to 3% NaCl, suggesting adaptive responses to moderate osmotic pressure, with potential applications in food fermentation[26,37]. At 6.0% NaCl, viability declined significantly, likely due to cellular dehydration and metabolic disruption[38,39]. This limits their application in high-salt food matrices.

Temperature tolerance testing revealed that all strains showed the highest viability at 37 °C, human body temperature, highlighting their suitability for gastrointestinal environments. However, none of the strains survived at 60 °C, reflecting the upper thermal limit due to irreversible protein denaturation[40]. Notably, S. boulardii JSB-T2 exhibited the broadest thermal tolerance, maintaining viability across cold (4 °C), ambient (20 and 37 °C), and elevated (45 °C) temperatures. This thermal adaptability supports its potential inclusion in a wide range of food matrices, including refrigerated and processed products. Bustos et al. similarly emphasized the importance of thermal stability in selecting functional probiotic strains; however, yeast generally exhibits lower thermal stability compared to probiotic bacterial strains[41].

The ability of these strains to withstand enzymatic and acidic environments supports their survivability during gastrointestinal transit, a key requirement for probiotic functionality[26]. Under simulated gastrointestinal conditions, all yeast strains exhibited differential survival across ASJ, SGJ, and SIJ. High survival in ASJ suggests lysozyme resistance, a crucial factor for oral-phase probiotic survival due to lysozyme's antimicrobial properties[42]. Viability decreased upon exposure to SGJ, primarily due to acidic pH and enzymatic stress, particularly among non-Saccharomyces strains[16,31]. However, survival improved slightly in SIJ, likely due to the more neutral pH of the intestinal environment[10]. Even though the three tested non-Saccharomyces strains exhibited comparable tolerance, S. boulardii JSB-T2 demonstrated a consistent ability to endure harsh gastrointestinal conditions with a high survival rate, highlighting its promising probiotic potential. Similarly, Pais et al.[14] reported that S. boulardii exhibited excellent tolerance to simulated gastrointestinal conditions by maintaining a survival rate of over 75%.

Cell surface hydrophobicity and auto-aggregation are essential for intestinal colonization and adhesion. H. uvarum JF3-T1N showed the highest hydrophobicity, suggesting a strong potential for epithelial binding[26,43]. Also, S. boulardii JSB-T2 exhibited the highest auto-aggregation, which could be beneficial for biofilm formation and the competitive exclusion of pathogens[10,43]. Similarly, Menezes et al.[20] stated that aggregation and adhesion properties were higher in Saccharomyces strains than in non-Saccharomyces strains such as Hanseniaspora spp. These surface properties highlight the ability of these yeasts to adhere to the gut and intestinal cells, thereby supporting host-microbiota balance and limiting pathogen colonization[44,45].

The antimicrobial evaluation revealed that only S. boulardii JSB-T2 exhibited broad-spectrum antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens. This effect may be due to the production of organic acids, polyamines, proteases, and other bioactive compounds known to be secreted by probiotic yeasts[46,47]. Such antimicrobial properties further strengthen its potential use as a functional probiotic strain.

Antifungal susceptibility testing using fluconazole, terbinafine hydrochloride, and itraconazole revealed varying levels of sensitivity among the strains. Fluconazole exhibited the most consistent inhibitory effect across all strains, with S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 being the most susceptible. S. boulardii JSB-T2 displayed lower susceptibility, especially to fluconazole and terbinafine hydrochloride, indicating a moderate degree of resistance. These findings emphasize the need to evaluate antifungal resistance profiles before clinical or therapeutic use of yeast-based probiotics[48,49]. Therefore, while the yeast strains exhibited a mixed response to the antifungal agents, they were generally more susceptible, particularly to fluconazole, highlighting their safety for potential use in food or pharmaceutical applications.

The antioxidant capacity of the strains was also explored using ABTS, DPPH, TPC, and FRAP assays. Both ABTS and DPPH assays assess radical scavenging activity through electron donation[16,50]. S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 exhibited the highest ABTS activity, as well as the highest TPC and FRAP values, while S. boulardii JSB-T2 showed superior DPPH scavenging activity. These results indicate that S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 possesses the greatest phenolic content and reducing power. The antioxidant effects observed are likely attributed to the production of phenolics, organic acids, and other radical-scavenging metabolites during yeast fermentation[51,52]. The higher antioxidant potential of S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 aligns with previous findings that non-Saccharomyces strains typically possess greater phenolic content and associated antioxidant activity[51]. Overall, all the yeast strains showed potential for probiotic application.

-

The comprehensive characterization of probiotic properties in Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeast strains, particularly S. boulardii JSB-T2 and S. bacillaris WMP4-T4, underscores their potential for application in functional foods and probiotic formulations. Their demonstrated tolerance to gastrointestinal stress, along with notable antimicrobial and antioxidant capacities, supports their use in fermented food products and dietary supplements. Future research should prioritize in vivo validation of these strains using animal models to confirm their health-promoting effects. Genomic and metabolomic profiling is also recommended to identify the molecular mechanisms and bioactive compounds underlying their probiotic traits. Additionally, evaluating their performance in real food matrices and under industrial processing conditions will be critical to establishing their viability and effectiveness as food-grade probiotic candidates.

-

The present study aims to evaluate the probiotic potential and functional characteristics of selected Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeast strains through a comprehensive set of in vitro assays. S. boulardii JSB-T2 consistently demonstrated superior tolerance to harsh gastrointestinal conditions, compared to the tested non-Saccharomyces yeast strains: H. opuntiae J1Y-T1, H. uvarum JF3-T1N, and S. bacillaris WMP4-T4. S. boulardii JSB-T2 exhibited high resilience to low pH, bile salts, phenol, NaCl, and temperature variations, highlighting its excellent probiotic nature. Notably, S. boulardii JSB-T2 also showed strong antibacterial activity against multiple foodborne pathogens, while S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 demonstrated the highest antioxidant activity, as indicated by its ABTS radical scavenging capacity and total phenolic content. All strains exhibited varying degrees of adherence-related traits, such as cell surface hydrophobicity and auto-aggregation, which are critical for colonization and persistence in the gastrointestinal tract. Furthermore, their tolerance to simulated saliva, gastric, and intestinal fluids confirmed their survivability through the human digestive system. Overall, the findings support the potential application of these yeast strains, particularly Saccharomyces sp. S. boulardii JSB-T2, which showed greater promise as a probiotic candidate compared to the tested non-Saccharomyces strains. Its functional attributes make it suitable for use in food and health-related applications. However, further in vivo validation and safety assessments are recommended to confirm its efficacy and potential for commercial use.

-

The present study did not include any experiments involving humans or animals.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Undugoda LJS; data collection: Weerabaddhanage AM, Pavalakumar D; analysis and interpretation of results: Weerabaddhanage AM, Pavalakumar D, Edirisingha IP, Gunathunga CJ, Sathivel T; draft manuscript preparation: Weerabaddhanage AM, Pavalakumar D, Edirisingha IP, Gunathunga CJ, Sathivel T, Undugoda LJS, Thambugala KM. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors would like to acknowledge the Department of Bio-systems Technology, Faculty of Technology, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka, for their assistance in carrying out this research.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Weerabaddhanage AM, Pavalakumar D, Edirisingha IP, Gunathunga CJ, Thivijan S, et al. 2025. Characterization of probiotic and antioxidant properties in Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeasts isolated from Sri Lankan grape wine fermentation. Studies in Fungi 10: e020 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0020

Characterization of probiotic and antioxidant properties in Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeasts isolated from Sri Lankan grape wine fermentation

- Received: 02 June 2025

- Revised: 11 July 2025

- Accepted: 10 August 2025

- Published online: 26 September 2025

Abstract: Grape skins harbor diverse microorganisms, including Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces yeasts, which play key roles in fermentation and enhance the sensory qualities of wine. This study aims to evaluate the probiotic and antioxidant properties of yeast strains isolated from Sri Lankan grapes, namely Hanseniaspora opuntiae J1Y-T1, Hanseniaspora uvarum JF3-T1N, Saccharomyces boulardii JSB-T2, and Starmerella bacillaris WMP4-T4. The probiotic potential was assessed by evaluating their tolerance to different levels of pH, bile salts, NaCl, phenol, and temperature, and viability under simulated gastrointestinal conditions. Antioxidant activity was assessed using ABTS and DPPH radical scavenging assays, ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), and total phenolic content (TPC) assays. Accordingly, S. boulardii JSB-T2 exhibited the highest tolerance to acidic pH, bile salts, NaCl, phenol, and temperature variations. It also remained highly viable in artificial saliva, simulated gastric and intestinal juices, maintaining survival rates of 94.10% ± 1.07%, 89.89% ± 1.09%, and 85.95% ± 0.86%, respectively. All strains exhibited strong cell surface hydrophobicity and auto-aggregation, which enable colonization in the gut. Notably, S. boulardii JSB-T2 demonstrated strong antibacterial activity against foodborne pathogens and showed a moderate level of tolerance to antifungal agents compared to other strains. Antioxidant analyses revealed that all tested yeast strains possess significant antioxidant properties. In particular, S. bacillaris WMP4-T4 showed the highest antioxidant potential in the TPC and ABTS assays, while S. boulardii JSB-T2 displayed the strongest activity in the DPPH assay. Overall, the Saccharomyces strain (S. boulardii JSB-T2) demonstrated comparatively stronger probiotic characteristics than the non-Saccharomyces strains, highlighting its greater potential for functional food and pharmaceutical applications.