-

Tea, one of the world's most consumed non-alcoholic beverages, holds significant cultural and economic importance globally. Originating in ancient China, tea cultivation has evolved into a major international industry spanning over 60 countries and regions, with annual production reaching 6.7 million metric tons as of 2022 (FAOSTAT, 2024). Beyond its economic significance, tea is renowned as a rich source of bioactive compounds, including polyphenols, theanine, terpenes, and caffeine, which contribute to its numerous health benefits[1,2]. Recognizing its profound cultural heritage and nutritional value, the United Nations designated May 21st as International Tea Day in 2019.

Despite its prominence, the tea industry faces critical challenges that threaten its sustainability. Quality variability, which is driven by complex interactions between agronomic practices, varietal diversity, harvesting methods, and post-harvest processing, erodes consumer trust and market stability[3−5]. These issues are compounded by climate change, as tea plants exhibit acute sensitivity to temperature fluctuations, droughts, and erratic rainfalls, leading to unpredictable yields and persistent quality decline[6−8]. Concurrently, labor shortages and rising operational costs increasingly strain traditional labor-intensive cultivation practices[9]. Conventional production methods, marked by outdated infrastructure, excessive agrochemical application, and energy-intensive processing, further undermine economic and environmental resilience[10].

Machine learning (ML), a transformative subfield of artificial intelligence (AI), has emerged as a promising solution to these challenges. By analyzing complex, multidimensional datasets and identifying latent patterns, ML enables automation, predictive decision-making, and precision resource management in agriculture[11]. Prior studies have demonstrated ML's efficacy in critical agricultural applications such as pest and disease detection[12,13], yield forecasting[14], resource optimization[15], and environmental monitoring[16], showcasing its potential to modernize farming while promoting sustainability.

Recent reviews have highlighted AI's expanding role in advancing precision agriculture, quality control, and IoT-driven automation in tea industry[17−19]. Computer vision (CV) and spectroscopy integrated with ML have automated tea bud detection and non-destructive quality assessment, while blockchain technologies and IoT platforms have enhanced traceability and real-time monitoring. However, practical guidance on implementing ML in real-world tea industry remains limited.

This review provides a focused examination of ML applications across the tea industry value chain. By synthesizing theoretical frameworks with practical methodologies–from data acquisition and feature engineering to model optimization and deployment–this review equips researchers, industry stakeholders, and practitioners with the essential knowledge to enhance efficiency, sustainability, and quality throughout tea industry systems. Through addressing key implementation challenges including scalability, integration with traditional practices, and resource constraints, this review aims to catalyze the transition from experimental ML frameworks to practical, adaptable agricultural solutions with measurable impacts on productivity and sustainability.

-

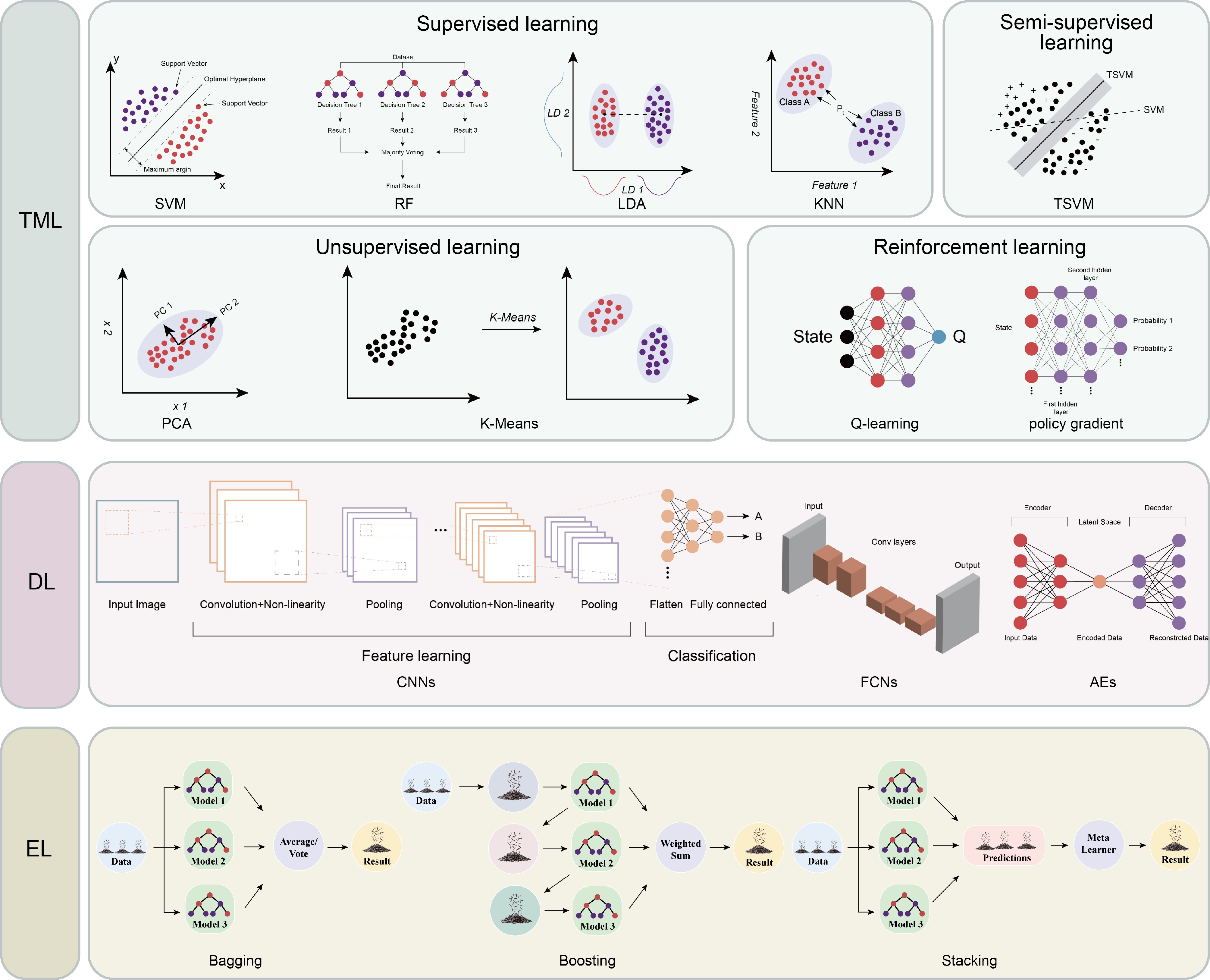

ML in tea research centers on three core methodologies: traditional machine learning (TML), deep learning (DL), and ensemble learning (EL), each addressing distinct challenges across the tea industry chain (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of machine learning (ML) methodologies. Visualization of ML approaches organized into three principal categories: traditional machine learning (TML), deep learning (DL), and ensemble learning (EL). TML encompasses supervised learning (exemplified by SVM, RF, LDA, and KNN), unsupervised learning (featuring PCA and K-Means Clustering), semi-supervised learning (represented by TSVM), and reinforcement learning (depicting Q-learning and policy gradient). DL demonstrates specialized neural network architectures, including CNNs, FCNs, and AEs. EL portrays integration strategies including bagging, boosting, and stacking.

TML

-

TML models relationships between input data and target variables through statistical learning, prioritizing interpretability and efficiency with structured datasets[20]. Its modular workflow, involving preprocessing, feature extraction, and classification, encompasses supervised, unsupervised, semi-supervised, and reinforcement learning approaches[21−23].

Supervised learning algorithms dominate tea research applications. Support Vector Machines (SVM) identify optimal hyperplanes to maximize margins between classes in high-dimensional space, making them effective for tea classification[24−27], disease detection[28,29], quality assessment[30], adulteration identification[31], and plantation mapping[32]. Random Forests (RF) combine multiple decision trees (DTs) through bootstrap aggregation, mitigating overfitting while providing feature importance rankings. This approach has been applied to predict tea yields[33], monitor fermentation stages[34], classify tea origins[35]and evaluate hazard risks[36]. Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) projects features onto axes that maximize inter-class variance, simplifying multidimensional chemical profiles[37−39]. K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) classifies samples based on majority votes from their k nearest neighbors, using distance metrics to grade tea quality with small datasets, while Naïve Bayes (NB) assumes feature independence to compute posterior probabilities, enabling rapid tea classification[40−43].

Unsupervised learning extracts patterns from unlabeled data. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) reduces dimensionality by projecting features onto orthogonal axes of maximum variance, resolving multicollinearity in tea spectral and chemical datasets[44,45]. K-Means Clustering partitions data into k groups by minimizing intra-cluster variance, with applications in automated tea leaf harvesting systems[46]. Hierarchical clustering builds nested clusters by iteratively merging or splitting groups, useful for identifying relationships among tea varieties based on chemical profiles[47].

Semi-supervised methods bridge labeled and unlabeled data to address scenarios where annotation is costly or requires expertise[48]. Operating on cluster and manifold assumptions, these methods improve generalization while minimizing labelling efforts. Self-training iteratively labels high-confidence predictions to expand the training set while co-training leverages multiple views of the data to enhance model robustness. Graph-based approaches propagate labels through similarity networks, particularly effective for spectral data classification[49]. Transductive Support Vector Machines (TSVM) extend traditional SVMs by optimizing decision boundaries to maximize margins in low-density regions of both labeled and unlabeled data, maintaining accuracy even when labeled samples are limited[50]. Semi-supervised learning has been combined with image processing to identify tender tea leaves under varying conditions[51], though broader adoption in tea-related tasks remains underexplored.

Reinforcement learning (RL) focuses on training agents to learn optimal decision-making policies by interacting with environments, aiming to maximize cumulative rewards over time[23]. Unlike supervised learning, RL operates on a trial-and-error framework, where agents iteratively refine strategies based on feedback from states and reward signals, which is crucial for applications requiring foresight, such as robotics, resource allocation, and game AI[52]. Recent methodological advancements, including Q-learning for value-based optimization, Monte Carlo techniques for episodic sampling, and policy gradient methods for direct policy updates, have strengthened RL's ability to handle stochastic and partially observable agricultural environments. Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) architectures, which integrate DL networks with RL decision-making (e.g., frameworks like DeepSeek), further enhance scalability and generalization for complex tasks[53]. In tea-harvesting robotics, a modified pointer network trained via the REINFORCE policy gradient (augmented by a critic network baseline) has demonstrated efficiency in solving picking sequence planning[54].

DL

-

DL methods process unstructured data like images and sensor streams through layered neural networks, combining feature design and modeling into unified systems that reduce manual preprocessing[55]. These systems learn patterns directly from raw inputs, addressing complex agricultural challenges such as identifying disease markers on tea leaves or distinguishing cultivars through spectral variations.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), foundational for image-based tasks in tea research, specialize in spatial feature extraction through learnable filters that capture hierarchical patterns in images. These filters detect low-level features in initial layers and progressively build more complex representations in deeper layers. Several landmark CNN architectures have been adapted for tea applications: LeNet established the convolutional-pooling pattern for tea leaf disease detection[56]; ResNet introduced residual connections to mitigate vanishing gradients in deeper networks, enabling superior feature extraction for disease classification[57]; YOLO's unified detection framework improved real-time efficiency for tea bud[58,59] and disease detection[60,61]; and R-CNN enhanced precision in tea pest localization and disease spot identification through region proposal networks[62].

Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) extend CNNs for pixel-level segmentation by replacing fully connected layers with convolutional layers, allowing end-to-end training and dense predictions on arbitrary-sized inputs[63]. This approach has facilitated precise determination of tea plucking points under variable field conditions[64] and supported the development of automated guidance systems for tea plantations[65].

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) process sequential data through feedback connections that maintain internal memory, making them ideal for time-series analysis in agricultural applications[66]. Unlike feedforward networks, RNNs share parameters across time steps while modeling temporal dependencies. In tea research, RNNs have been integrated with CNNs for accurate tea plantation mapping from multi-temporal imagery[67]. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, an advanced RNN variant designed to capture long-term dependencies, have been applied to tea disease detection[68], growth monitoring[69,70], and pest control[71].

Autoencoders (AEs) compress input data into compact latent representations through encoder-decoder structures, proving valuable for dimensionality reduction, anomaly detection, and noise filtering. Variational autoencoders (VAEs), an extension of traditional AEs, introduce probabilistic encoding by learning distributions of latent variables, yielding flexible and generalizable representations of complex data patterns. These architectures have demonstrated effectiveness in recognizing tea diseases[72,73] and differentiating tea clones[74], even under noisy or distorted conditions.

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), such as Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP), are supervised models inspired by biological neural networks, comprising input, hidden, and output layers[11]. Their functionality is determined by activation functions, network structure, and learning algorithms. ANNs have been widely applied to structured data tasks, including authenticating tea origins[5], predicting antioxidant activity from biochemical profiles[75], optimizing tea drying conditions[76], and classifying tea types and grades[77,78].

EL models

-

EL enhances predictive accuracy and robustness by combining multiple algorithms, drawing on their strengths while reducing individual weaknesses. Common EL techniques include bagging (e.g., RF), boosting (e.g., AdaBoost, XGBoost, and LightGBM), and stacking. Bagging reduces variance by aggregating predictions from bootstrapped models, boosting iteratively refines weak learners by focusing on misclassified samples, and stacking integrates heterogeneous models through meta-learners to optimize final prediction[79]. These approaches are particularly effective for both classification and regression tasks, especially when base models exhibit high variance or bias.

In tea research, EL has delivered superior performance across cultivation and production tasks. RF, Bagging, and AdaBoost have outperformed conventional models in estimating daily evapotranspiration rates, a critical metric for irrigation planning in tea plantations[80]. For complex nonlinear problems like carbon flux prediction, hybrid approaches such as the nonlinear ensemble-generalized regression neural network (NLE-GRNN) have significantly improved the prediction accuracy for the net ecosystem exchange[81]. Gradient Boosting (GB) has been effective for the geographic origin authentication of Wuyi rock tea, achieving high accuracy with reduced data complexity by iteratively optimizing feature interactions[5].

-

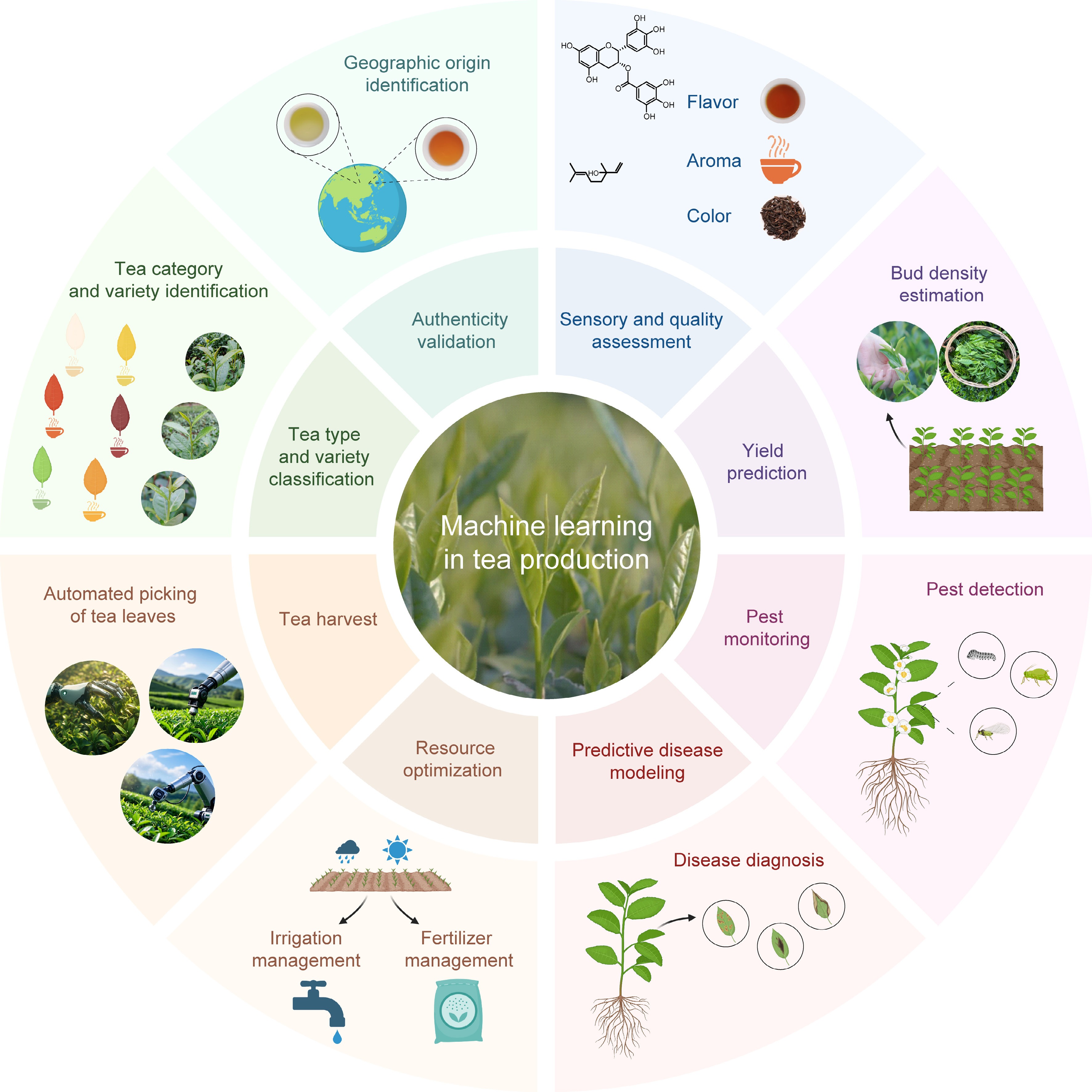

ML integrates seamlessly across the entire tea industry chain, spanning cultivation, processing, and quality control (Fig. 2). In cultivation, ML-powered systems analyze imagining and sensor data to automate disease detection, pest identification, yield forecasting, tea harvest, and resource allocation. For processing and classification, ML streamlines tea categorization by type, variety, and origin, ensuring authenticity and standardization. In quality evaluation, ML models replace subjective assessments with data-driven analyses of sensory traits and chemical profiles, establishing objective metrics for quality assurance.

Figure 2.

ML applications in tea industry systems. This schematic depicts key applications of MLs throughout the tea value chain, including geographic origin authentication, tea variety classification, sensory quality assessment, yield prediction, resource optimization, pest monitoring, disease diagnosis, and automated harvesting.

Tea quality and sensory evaluation

-

The integration of ML with non-invasive spectroscopic and imaging technologies has significantly improved tea quality assessment, enabling rapid, objective, and holistic evaluations that enhance precision in multi-sensory profiling.

Traditional methods for tea color assessment, which rely on human judgment, have been revolutionized by ML-driven approaches. For instance, CV combined with DT AdaBoost algorithms has achieved 98.50% prediction accuracy in color grading of needle-shaped green tea[82]. Similarly, MLP models applied to colorimetric data have improved the reliability of instrumental color assessments for Sichuan Dark Tea[83].

In flavor evaluation, advancements in electronic sensing technologies paired with ML have yielded remarkable results. A multi-task back-propagation neural network (MBPNN) integrated with electronic nose data has attained 99.83% accuracy for organic green tea grading and price prediction, surpassing conventional RF and SVM models[84]. Similarly, ant colony optimization (ACO)-SVM hybrid methods using electronic tongue and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) data have achieved 93.56% accuracy in black tea grading[30]. Research combining electronic nose, tongue, and eye technologies with chemometrics has reported 100% accuracy in tea grade classification and superior prediction of chemical components (R2 > 0.97), with RF models on fused signals outperforming single-sensor approaches[85]. More recently, a multi-modal fusion of CV and NIRS with a temporal convolutional network (TCN) has elevated black tea quality assessment to 98.2% accuracy by synthesizing appearance, chemical, and spectral data[86], underscoring the power of data fusion in quality control.

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) has become essential for tea quality analysis, offering unique insights through simultaneous spectral and spatial feature extraction when combined with ML models. For example, HSI with spectral-texture fusion and LSSVM models has achieved 99.57% accuracy in Dianhong black tea evaluation[87]. The integration of HSI with olfactory visualization systems and SVM has improved green tea classification accuracy to 92%, outperforming single-sensor methods[88]. In a cross-category application, the feature fusion of electronic nose and HS data optimized via XGBoost has demonstrated robust performance (R² = 0.900, RMSE = 1.895) for polyphenol content estimation across black, green, and yellow teas[89]. Collectively, these technological advances establish objective, reproducible analysis systems that complement human expertise while overcoming the limitations of traditional evaluation methods.

Tea harvest automation

-

The integration of ML into tea harvesting has shifted traditional non-selective mechanical methods toward precision-based selective systems, driven by advancements in intelligent target identification and automation. ML methodologies now underpin three core components of the harvesting pipeline: bud detection, picking point determination, and integrated system optimization, which enhance efficiency and accuracy.

Accurate bud identification forms the foundation of selective harvesting. Recent innovations include an optimized YOLO v3 algorithm achieving over 90% detection accuracy across four distinct morphological categories of tea targets[90]. For real-time classification, a DenseNet-20 based CNN model has attained 96.9% accuracy using augmented real-time datasets (262 images), outperforming SVM (73.1%)[91]. In resource-constrained environments, a K-Means Clustering combining with image morphology processing has attained over 80% recognition accuracy while minimizing computational costs[92].

Precise localization of picking points is critical for minimizing mechanical damage. One approach has integrated YOLO-v3 detection with Fast-SCNN semantic segmentation, skeleton extraction, and minimum bounding rectangle algorithms, achieving 83% accuracy in picking point localization[93]. More advanced approaches have adopted a cascaded Faster R-CNN and FCN framework, improving accuracy to 84.9% through hierarchical stem segmentation[64]. Mask R-CNN has subsequently streamlined this process while delivering comparable robustness in complex environments[94].

Modern systems unify detection, localization, and motion planning into cohesive workflows. A compressed YOLO-v3 network fused with point cloud processing and spatial path planning has demonstrated success rates of 85.16% for bud detection, 78.90% for picking point localization, and 80.23% for motion planning[95]. These integrated systems represent cutting edge ML applications in tea harvesting, achieving precision and efficiency unattainable with conventional methods.

Yield prediction, resource optimization, and growth monitoring

-

ML has become integral to tackling issues in tea cultivation, particularly in yield forecasting, resource management, and plant health tracking. In yield prediction, the XGBoost regressor has delivered higher accuracy with fewer inputs (MAE: 0.0093 t/ha, RMSE: 0.120 t/ha) compared to traditional crop simulation models[96]. In small-scale hillside tea farms, YOLOv5 paired with on-site sampling has analyzed bud density with 29.56% relative error, supporting early management decisions[97]. A spatiotemporal hybrid model (DRS-RF) integrating dragonfly optimization (DR) with support vector regression has reduced prediction errors to 11%[33]. Remote sensing integration has further advanced scalability. Sentinel-2 satellite imagery fused with UAV-derived RGB data has been used to develop season-specific ML models for field-scale yield estimation, achieving reasonable annual accuracy (R2 = 0.47, RMSE = 168.7 kg/acre)[98].

For resource optimization, ML has improved irrigation efficiency. An SVM model enhanced with the Bald Eagle Search algorithm has predicted soil moisture levels with high precision (R2 = 0.9435)[99]. RF-based methods have mapped land suitability to identify optimal cultivation zones[100]. NIRS-HSI combined with optimization algorithms have allowed pixel-level moisture monitoring, enabling targeted irrigation strategies[101].

In growth monitoring, multi-sensor UAV platforms combining LiDAR, multispectral, and RGB data with ML algorithms have demonstrated strong predictive capabilities for key phenotypic parameters. RF models have estimated leaf chlorophyll (R2 = 0.87) and nitrogen contents (R2 = 0.65), whereas SVM has performed well in assessing leaf area index (R2 = 0.90) and plant height (R2 = 0.82)[102]. The Random Forest with Parameter Optimization (RFPO) algorithm, which merges UAV-derived vegetation indices with meteorological data, has mapped spatial variations in leaf dry matter and nitrogen levels (R2 = 0.80 and 0.79, respectively), aiding precision nutrient management[103].

Disease and pest management

-

ML has contributed to more effective disease and pest control in tea cultivation by improving early detection accuracy and guiding targeted treatment strategies. For disease management, CNN-based systems have classified seven common tea diseases with over 90% accuracy[104]. Pooling-based CNNs combined with weighted RF models have raised detection rates to 92.47%[105]. Advanced segmentation techniques like SLIC_SVM have improved the extraction of tea leaf disease saliency maps from complex backgrounds, achieving 95% accuracy in evaluations of precision, recall, and F1-score[106]. Researchers have also expanded focus to severity quantification: VGG16 networks using Retinex enhancement and Faster R-CNN have improved detection precision by 6% and severity grading accuracy by 9% over traditional methods[107]. For occluded leaves in field conditions, ellipse restoration paired with SVM segmentation has reached a mean F1-score of 84%, outperforming standard CNNs[108]. Architectural comparisons have shown DenseNet169 surpassing ResNet50 (95.2%), and VGG16 (90.6%) with 99% accuracy, faster convergence, and lower loss values[109].

In pest management, CNN-based models have identified 14 pest types with 97.75% accuracy, exceeding TML approaches[110]. Faster R-CNN has detected lesions caused by three diseases and four pests at 89.4% accuracy, providing real-time diagnostic support[111]. Feature selection combined with Incremental Backpropagation Learning Network (IBPLN) has achieved perfect classification accuracy (100%) for pest identification[112]. A modified Yolov7-tiny model, enhanced with deformable convolution and dynamic attention mechanisms, has optimized pest detection efficiency (93.23% accuracy) while reducing computational time and costs[113].

Classification of tea categories and cultivars

-

ML has strengthened the classification of tea types and cultivars to ensure product consistency and aid breeding efforts. In tea category classification, fluorescence hyperspectral technology combined with MSC-RF-RFE-SVM models has identified oolong tea varieties with 98.73% accuracy[41]. For cross-category differentiation, NIRS-HSI paired with redundant wavelet transforms and a lightweight CNN (L-CNN) have distinguished black, green, and yellow teas at 98.73% accuracy[114]. A hybrid approach merging spectral and texture features with Lib-SVM has classified five Chinese tea categories at 98.39% accuracy[115].

For cultivar identification, hyperspectral reflectance data from tea plant canopies analyzed with SVM, LDA, and ANNs have differentiated six out of nine tea varieties with 75%−80% accuracy, even under natural field conditions[116]. CNN-based methods like DenseNet201 have achieved 96.38% accuracy in cultivar recognition, rising to 97.81% with optimized training and data augmentation[117].

Tea origin authentication and fraud detection

-

ML integrated with spectroscopy and metabolomics has improved tea traceability and fraud detection. In origin authentication, gas chromatography–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC-TOFMS) analysis of 333 Wuyi rock tea samples has detected geographic origins with over 90% accuracy using an MLP model[5]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy paired with RF and SVM has identified black tea origins at 92.7% and 91.8% accuracy, respectively[118], while NIRS-HSI with PCA-SVM has classified green tea origins at 97.5% accuracy[119].

For adulteration detection, fluorescence hyperspectral imaging combined with an SVM model has identified Tieguanyin tea adulterated with lower-grade Benshan tea, achieving 100% accuracy for pure samples and 94.27% accuracy in mixed batches using SNV-RF-SVM[120]. Spectrophotometry coupled with neural network modeling has detected the banned additive carmine in black tea with 100% accuracy, closely matching HPLC results (R² > 0.97)[121]. A smartphone-based micro-NIRS device with SVM has classified adulterated green tea at 97.47% accuracy, while an SVR model has quantified contaminants like sugar and glutinous rice flour[122].

-

The development of ML pipelines offers a structured approach to transforming raw data into actionable insights within the tea industry, addressing critical tasks such as yield prediction, quality assessment, and pest detection. This section provides comprehensive guidelines for developing effective ML pipelines, using tea leaf disease detection as an illustrative case study while emphasizing adaptable principles applicable to diverse tea-related applications.

Guidelines for developing ML pipelines

-

Automatic Machine Learning (AutoML), pioneered by organizations such as Google and prominent academic institutions, simplifies the adoption of ML by automating essential tasks including data preprocessing, feature selection, and hyperparameter optimization[123,124]. This automation benefits practitioners across experience levels by enhancing accessibility and operational efficiency. Complementary technologies such as MobileNetV2[125] and multi-scale feature extraction methodologies[126] further streamline computational requirements while preserving model accuracy.

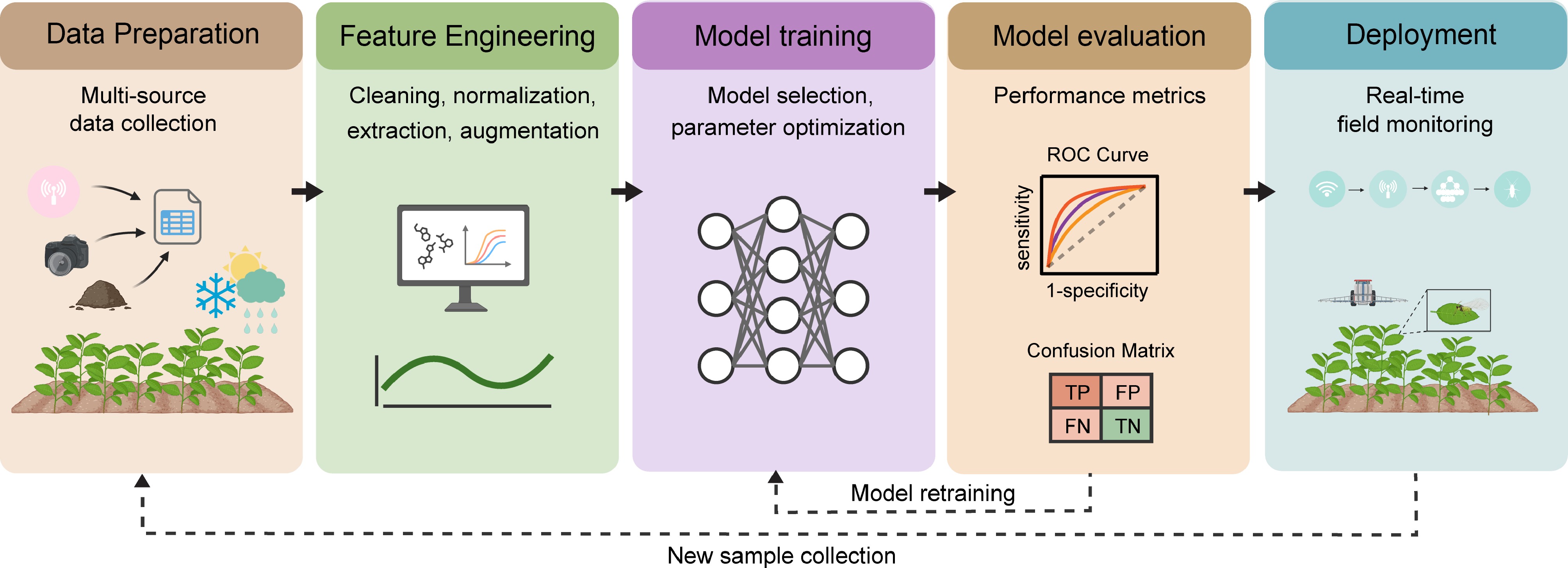

A well-structured ML pipeline typically encompasses four fundamental stages: data preparation and feature engineering, model training and optimization, model evaluation, and deployment. Figure 3 illustrates these sequential stages from initial data collection through to operational deployment, while Table 1 summarizes the key components, their specific relevance to tea applications, and commonly employed tools and techniques to guide implementation.

Figure 3.

Structured workflow of ML pipeline implementation for tea-specific applications. Systematic representation of the end-to-end ML pipeline encompassing sequential stages: multimodal data acquisition and preprocessing, domain-specific feature engineering, model architecture selection and hyperparameter optimization, comprehensive performance evaluation, and deployment with edge computing integration. The pipeline incorporates feedback mechanisms for continuous model refinement based on operational data and evolving environmental conditions.

Table 1. Key components of an ML pipeline for tea-related tasks.

Stage Description Relevance to tea tasks Example tools/techniques Data preparation and feature engineering Data integration, preprocessing

(e.g., scaling, normalization), augmentation, feature extraction, and selectionIntegrates diverse tea-specific data: leaf images, NIR/hyperspectral scans, soil parameters, and weather metrics, and electronic tongue/nose readings. Augmentation simulates field conditions to improve model robustness. H2O-AutoML, PCA, mutual information, recursive feature elimination, image rotation/brightness adjustment Model training and optimization Model selection, hyperparameter optimization, iterative refinement Optimizes models for tea-specific tasks: disease detection, quality grading, yield prediction, and fermentation monitoring. Balances accuracy with computational efficiency for field deployment. Bayesian optimization, evolutionary algorithms, MobileNetV2, CNNs for disease detection, RNNs for fermentation monitoring Model evaluation Performance metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, R² and RMSE), cross-validation, error

analysisValidates model reliability across different tea varieties, regions, and seasonal conditions. Identifies specific error patterns in tea-related predictions and classifications. K-fold cross-validation, confusion matrix analysis, performance comparison tools, learning curve visualization Deployment Architecture optimization, model compression, edge computing implementation, IoT integration Enables field-level applications: real-time disease detection, harvest optimization, and processing monitoring through lightweight models on portable devices and sensor networks. NAS, AutoML for Model Compression (AMC), MobileNetV2, edge-AI frameworks, IoT sensor integration for tea estate monitoring Data preparation and feature engineering

-

Robust data preparation constitutes the foundation for developing reliable ML models. Platforms such as H2O-AutoML automate critical preprocessing procedures, including data normalization, scaling, and outlier management, ensuring consistency across heterogeneous datasets. In tea-related applications, diverse data sources such as leaf imagery, soil quality parameters, and meteorological variables can be integrated to create comprehensive datasets for modeling complex relationships.

To enhance generalization capabilities and reduce overfitting, data augmentation strategies such as brightness modulation, geometric transformations, and controlled noise introduction can be implemented. These techniques effectively simulate the variations frequently encountered in field conditions. For instance, in tea leaf disease detection systems, such augmentation ensures consistent model performance across varying illumination conditions and orientation differences.

Feature engineering remains equally critical for model performance and interpretability. AutoML platforms frequently automate feature extraction using methods such as feature importance scoring and PCA. For tea quality assessment, characteristics including leaf coloration, texture patterns, and biochemical compositions are commonly emphasized. Advanced feature selection methods like mutual information analysis and recursive feature elimination effectively reduce data redundancy while preserving the most informative attributes[127,128].

Model training and optimization

-

The model training phase involves the selection and refinement of algorithms to achieve optimal performance while mitigating overfitting risks. AutoML platforms streamline this process through automated model selection and hyperparameter tuning, minimizing both manual intervention and error potential. In tea-related applications, training objectives may include detecting subtle quality variations in premium tea leaves, differentiating rare cultivars, or achieving accelerated inference speeds for real-time monitoring systems.

To improve model generalization and reduce overfitting, practitioners should implement strategies such as regularization techniques (e.g., dropout and L2 regularization), early stopping protocols, and utilization of sufficiently diverse training datasets[129,130]. Incorporating variations across multiple tea cultivars, developmental stages, and environmental conditions can strengthen model robustness. Additionally, advanced hyperparameter optimization approaches, including Bayesian optimization and evolutionary algorithms, can further refine model performance. Bayesian optimization predicts optimal hyperparameters using probabilistic models, making it particularly suitable for complex, high-dimensional parameter spaces[131]. Evolutionary algorithms iteratively refine configurations by simulating natural selection processes, balancing exploration of diverse model structures with exploitation of promising solutions, thereby improving both performance metrics and generalization capabilities[132].

Model evaluation

-

Comprehensive model evaluation is essential for assessing reliability and generalization potential. AutoML platforms typically implement k-fold cross-validation, a methodical technique that systematically partitions the data into multiple subsets to evaluate model performance across diverse conditions. For classification tasks such as disease identification or quality categorization, key performance metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score provide a quantitative assessment of model efficacy. Visualization tools like confusion matrices offer insights into misclassification patterns, such as differentiating healthy leaves from early-stage disease manifestations. For regression-based applications prevalent in tea research, such as yield prediction, biochemical content estimation, and continuous quality assessment, traditional evaluation metrics like coefficient of determination (R2) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) are particularly valuable. R2 quantifies the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from independent variables, providing insights into model fit quality, while RMSE measures the average magnitude of prediction errors in the original variable's units, offering practical interpretability for agricultural stakeholders. There metrics are especially relevant when predicting continuous variables such as tea yield quantities, antioxidant levels, or precise flavor compound concentrations. Furthermore, many AutoML frameworks support comparative performance analysis across multiple models using these diverse evaluation criteria, allowing practitioners to select optimal solutions based on application-specific requirements.

Deployment-ready solutions

-

Effective deployment ensures that trained models operate efficiently in real-world environments. AutoML tools facilitate this transition by automating architecture selection, model compression, and hardware optimization. While certain platforms support advanced functionalities such as Neural Architecture Search (NAS) for complex optimization scenarios, most emphasize balancing model accuracy with resource efficiency to address practical constraints[133]. These platforms enable the deployment of high-performing models for field applications such as monitoring tea plantations using resource-constrained edge devices. Techniques including reinforcement learning and evolutionary algorithms embedded within AutoML frameworks assist in discovering efficient architectures while reducing computational demands. Automated pruning methodologies, such as AutoML for Model Compression (AMC), further optimize performance by reducing model complexity without significant accuracy degradation[134].

Case study: ML pipelines for tea plant disease detection

-

To demonstrate the practical implementation of an ML pipeline, we present a case study on tea plant disease detection[135]. A diverse image dataset of tea leaves was collected under varying environmental conditions using mobile imaging devices. Preprocessing procedures included standardized image resizing, normalization, and data augmentation (e.g., brightness adjustment and rotation) to enhance model robustness.

The dataset was split into training and validation subsets in a 7:3 ratio to ensure a balanced evaluation. Feature engineering techniques focused on extracting multi-scale texture patterns and morphological characteristics. The Coordinate Attention mechanism was implemented to emphasize disease-specific regions, while Multi-branch Parallel Convolution modules expanded the receptive field of the network, improving generalization across varying disease severities. The MobileNetV2 architecture, refined through NAS and optimized using AMC, achieved a classification accuracy of 96.12% across five common tea leaf diseases. This approach surpassed previous methods by balancing computational efficiency with model accuracy. Further improvements could include expanding the dataset to cover a broader spectrum of leaf conditions, incorporating supplementary data sources such as soil health parameters, and implementing periodic model retraining to adapt to evolving agricultural environments. Additionally, integrating explainable AI techniques would improve model interpretability for agricultural practitioners, potentially accelerating adoption in commercial tea industry settings.

-

The integration of ML in the tea industry presents significant innovation opportunities despite challenges posed by seasonal variability, quality differentiation, and geographic diversity. Addressing these challenges is crucial for maximizing ML potential in cultivation, processing, and quality assessment.

Data quality, availability, and resource constraints

-

ML applications in tea industry require high-quality datasets to model critical processes such as leaf growth, disease progression, fermentation stages, and quality assessment. However, fragmented cultivation practices often yield inconsistent data. Smallholder farms frequently lack infrastructure to collect comprehensive data on critical variables such as soil health, pest outbreaks, or yield trends, undermining model accuracy.

Several approaches can address these constraints. Advanced preprocessing techniques can manage missing or inconsistent data by transforming raw inputs into more reliable features. Domain-specific knowledge helps bridge gaps and generates novel features that accurately reflect seasonal variations and regional differences in tea industry systems. Additionally, cost-effective tools like smartphone imaging systems and portable NIR spectrometers offer practical approaches for localized data acquisition. For instance, handheld NIR devices have been deployed to correlate spectral patterns with flavor compounds in tea, directly linking field-based data collection to quantifiable quality outcomes[136,137].

In addition to enhancing data collection methods, lightweight ML models optimize performance in resource-constrained environments. I-MobileNetV2 designed for tea disease identification is a prime example. By incorporating Coordinate Attention mechanisms and Multi-branch Parallel Convolution algorithms, this model has achieved a 40% reduction in computational complexity while maintaining 96.12% accuracy[135]. Similarly, lightweight CNNs with knowledge distillation have shown promise for quality control during black tea fermentation[138]. These optimized models provide an effective balance between computational efficiency and predictive performance, making them well-suited for environments with limited computational resources.

Cloud platforms and open-source tools enhance data processing capabilities. A Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) cloud system utilizing CNNs has enabled real-time tea disease prediction, allowing farmers to upload plant images for rapid analysis[139]. This capacity for real-time analysis helps address challenges posed by fluctuating weather conditions and emergent pest outbreaks, allowing for timely decision-making and more effective disease management protocols.

Moreover, strategic partnerships with technology providers can improve access to specialized tools and expertise. These collaborative arrangements enable the selection and implementation of data collection and processing systems specifically tailored to the tea sector, ensuring that smallholder operations can adopt appropriate technologies despite resource limitations. Such partnerships also provide ongoing technical support in data analysis, model deployment, and troubleshooting, thus overcoming technological barriers commonly faced by smallholder producers.

Finally, pre-trained models offer practical solutions for smallholder agricultural operations by allowing fine-tuning with smaller, region-specific datasets. These models, initially trained on large, diverse datasets, such as CNNs for disease detection or sensor data analysis frameworks, require substantially less data to adapt to local conditions. This approach reduces the need for extensive data collection, accelerates ML implementation, and eases the burden on smallholder producers.

Security and privacy concerns

-

Digitization of plantation data underpins ML applications but introduces risks to sensitive information like proprietary processing techniques and blending formulas. As such, robust security measures are essential to protect data integrity and maintain privacy.

To address these risks, privacy-preserving technologies including data encryption protocols and secure access controls should be implemented[140,141]. Multi-factor authentication and role-based access systems can restrict data access to authorized personnel. Furthermore, industry-specific data-sharing protocols, such as secure cloud-based platforms, can enable collaborative research without compromising proprietary information.

Human-machine collaboration and transparency

-

The tea industry's historical reliance on traditional knowledge and artisanal expertise can create resistance to ML adoption. Agricultural producers may distrust ML-generated predictions that contradict their experiential knowledge, while professional tasters and quality graders might perceive ML-based quality assessments as lacking the nuanced sensory discrimination essential for tea evaluation.

To foster effective human-machine collaboration, ML systems should be designed to augment rather than replace human expertise[142]. User-centric interfaces that seamlessly integrate ML-derived insights into existing operational workflows can bridge the gap between traditional practices and technological innovation. Customized training programs are equally crucial for building trust, demonstrating how ML complements rather than supplants traditional methodologies. For example, ML algorithms can analyze historical yield data in conjunction with farmers' observational records to deliver more accurate and context-aware recommendations.

Transparency in ML model development and operation is equally important for improving stakeholder acceptance. Explainable AI techniques that clearly articulate how models arrive at specific decisions can boost trust in automated systems[143]. For instance, a crop disease prediction model could provide clear visualizations of affected plant regions and explicit explanations of the factors driving its diagnosis. Clear communication of both the capabilities and limitations of ML systems in accessible language will build confidence and encourage widespread adoption across the industry.

Academic and industrial integration

-

The effective implementation of ML technologies hinges on bridging the persistent gap between academic research initiatives and industrial practice. Limited collaboration between academic institutions and industry stakeholders frequently results in technological solutions that inadequately address the practical challenges faced by tea producers. Furthermore, the absence of comprehensive interdisciplinary training programs has created a significant shortage of professionals possessing expertise in both ML methodologies and tea industry.

Strengthening collaborative partnerships between universities, research institutions, and commercial tea producers is therefore essential. Integrated research initiatives should specifically focus on addressing industry-relevant challenges, such as developing ML models to assess the impact of climate change on yields or predicting optimal blending ratios for consistent flavor. Additionally, interdisciplinary educational curricula that integrate ML with agricultural science principles can better prepare future professionals to tackle these challenges. For example, specialized training programs combining ML techniques with sensory evaluation methods commonly used in tea quality assessment could facilitate the development of tools that align more precisely with industry requirements.

-

The tea industry is undergoing a profound transformation driven by increasingly complex demands for efficiency, quality consistency, and sustainability across global production systems. ML has emerged as a pivotal tool for addressing multifaceted challenges within the sector, from optimizing cultivation and processing workflows to facilitating non-destructive quality assessment. By harnessing comprehensive data-driven insights, ML models have demonstrably contributed to smarter cultivation practices, improved quality control, and refined sensory profiling of diverse tea products. Despite these advances, substantial implementation barriers persist, including prohibitive initial investment costs, infrastructure limitations particularly in developing regions, and a critical shortage of professionals with interdisciplinary expertise. Overcoming these systematic obstacles will necessitate sustained collaborative initiatives among academic researchers, industry stakeholders, and technology developers to create contextually appropriate solutions.

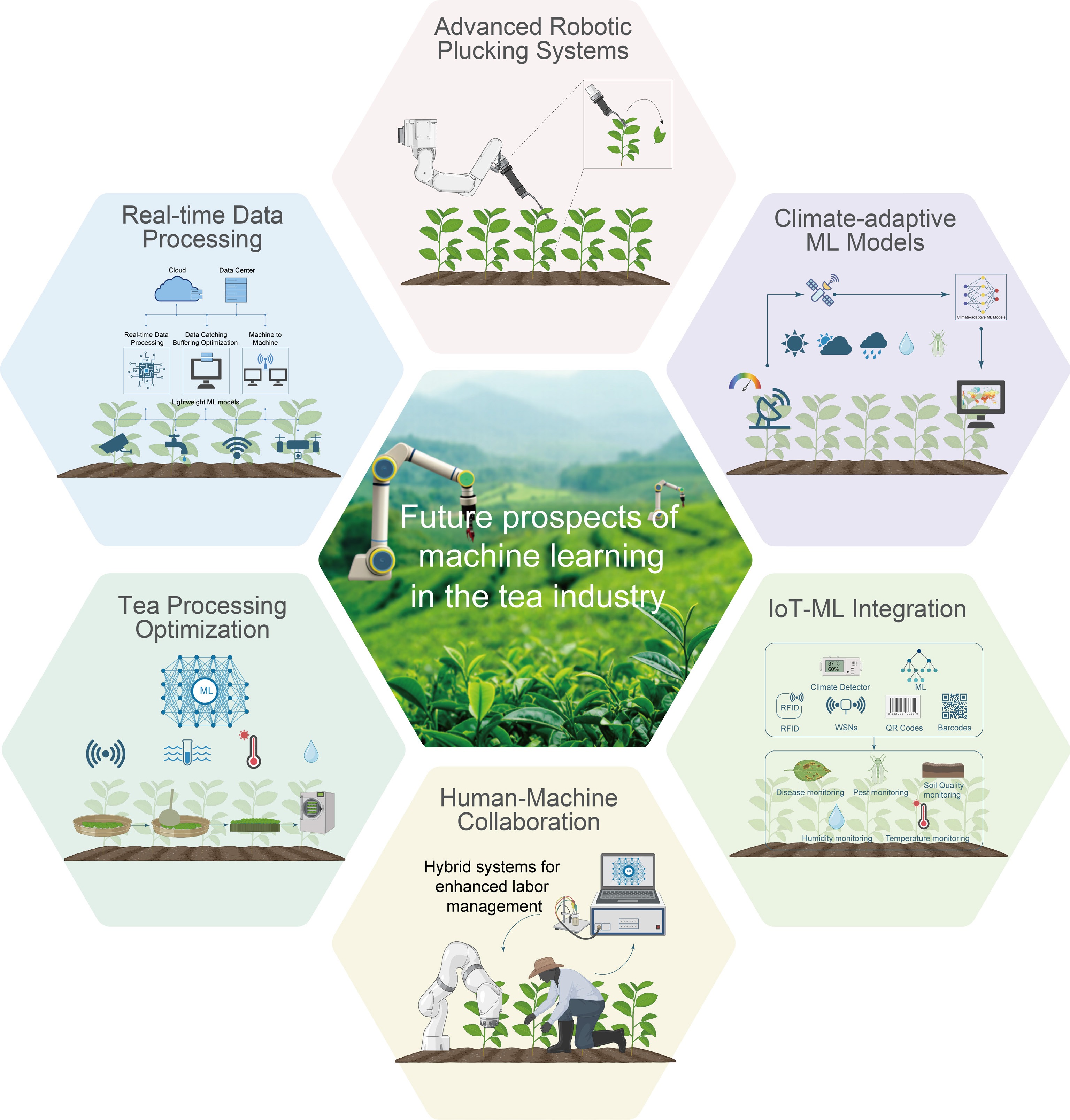

Looking forward, several promising research trajectories hold significant potential for further advancing the integration of ML technologies throughout the tea value chain (Fig. 4):

Figure 4.

Future prospects of ML applications in tea industry. Key future ML applications in tea industry include robotic plucking, real-time data processing, climate-adaptive models, processing optimization, IoT integration, and human-machine collaboration.

(1) Advanced robotic plucking systems with sophisticated ML integration. Future research initiatives should prioritize the development of advanced ML algorithms for autonomous harvesting systems capable of highly selective plucking operations. These next-generation systems must effectively account for complex variables including leaf maturity indices, environmental heterogeneity, and variable canopy architectures while simultaneously optimizing precision in leaf selection and minimizing mechanical damage to delicate tea shoots. Particular emphasis should be placed on developing adaptive learning capabilities that can accommodate diverse cultivars and production contexts.

(2) Real-time data processing through edge computing and ML integration. The strategic convergence of edge computing technologies with lightweight ML models presents opportunities for improving decision-making processes at the plantation level. Research priorities should focus on optimizing resource-efficient ML architectures that can effectively process multimodal sensor data on-site, enabling real-time interventions across critical domains including precision irrigation management, early-stage pest and disease detection, and dynamic resource allocation based on spatiotemporal needs.

(3) Climate-adaptive ML models for resource efficiency and environmental sustainability. Developing sophisticated ML models capable of integrating diverse data streams, including high-resolution climate data, multispectral satellite imagery, and field-level measurements can support advanced predictive capabilities for weather pattern forecasting, resource optimization, and comprehensive soil health management. These integrated models could substantially contribute to climate adaptation strategies, such as precision water management, targeted pest control, and optimized soil nutrient management while reducing environmental impacts through minimized carbon emissions and water consumption.

(4) Optimization of tea processing through ML-driven monitoring systems. The application of ML methodologies in tea processing operations offers considerable potential for enhancing product consistency and quality attributes. Research endeavors should concentrate on developing real-time monitoring systems that use multiparametric sensors and advanced ML algorithms to assess critical processing parameters such as leaf moisture dynamics, oxidation kinetics, fermentation progression, and precise drying conditions. Such systems would ensure consistent product quality across production batches while potentially identifying novel processing optimizations not apparent through traditional methods.

(5) IoT-ML integration for holistic estate management. With the accelerating adoption of IoT technologies on tea estates, establishing standardized protocols for integrating diverse IoT devices with specialized ML models becomes increasingly essential. Such integrated systems can enable continuous monitoring of environmental conditions, soil health, and operational factors, thereby optimizing agricultural practices and promoting evidence-based sustainable estate management decisions aligned with certification requirements.

(6) Human-machine collaboration frameworks for labor optimization. As persistent labor shortages continue to impact the tea industry, particularly in traditional production regions, ML can assist in managing human resources more effectively. Research should explore hybrid systems that synergistically combine ML capabilities with human expertise, offering real-time guidance, predictive analytical insights, and task optimization recommendations, particularly for manual tasks such as selective harvesting and critical processing stages requiring sensory evaluation.

In conclusion, ML technologies present substantial opportunities for enhancing productivity, product quality, and sustainability within the tea industry. Targeted interdisciplinary research focusing on autonomous harvesting systems, real-time analytical capabilities, climate adaptation strategies, processing optimization methodologies, comprehensive IoT integration frameworks, and human-machine collaborative systems is essential for unlocking the full transformative potential of ML applications in this sector. Sustained collaborative partnerships among academia, industry, and technology developers will remain critical to ensuring successful implementation, continuous improvement, and widespread adoption of these innovations across diverse production settings.

The research was funded by the State Key Laboratory of Ecological Pest Control for Fujian and Taiwan Crops (SKL2023002) and the Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (FAFU) Construction Project for Technological Innovation and Service System of Tea Industry Chain (K1520005A02).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization and writing: Gao F, Wang S, Yu X; figure and table modification: Gao F, Wang S, Yu X; review and editing: Gao F, Wang S, Yu X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Fuquan Gao, Shuyan Wang

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Gao F, Wang S, Yu X. 2025. Machine learning in tea industry: data-driven approaches for quality and sustainability. Beverage Plant Research 5: e030 doi: 10.48130/bpr-0025-0016

Machine learning in tea industry: data-driven approaches for quality and sustainability

- Received: 06 January 2025

- Revised: 12 March 2025

- Accepted: 14 April 2025

- Published online: 17 October 2025

Abstract: Tea holds significant cultural, economic, and nutritional value globally, yet the industry faces persistent challenges including quality inconsistency, climate change impacts, labor shortages, and inefficient conventional production methods. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful solution to address these challenges through data-driven decision-making, automation, and resource optimization across the entire production chain. This review systematically examines ML applications throughout tea industry, from cultivation and harvesting to processing and quality assessment. We analyze the development of comprehensive ML pipelines encompassing data acquisition, feature engineering, model development, optimization, evaluation, and deployment. Key technological advancements include automated monitoring systems for enhanced productivity, non-destructive spectroscopic and imaging techniques for improved quality assessment, and precision resource management for sustainable production. Despite its transformative potential, widespread ML adoption faces implementation barriers, including limited data availability, scalability issues, and integration with established practices. To overcome these barriers, we highlight strategic approaches such as advanced preprocessing techniques and domain-specific feature engineering to mitigate data limitations, resource-efficient ML architectures tailored for constrained environments, and user-centered interfaces that effectively bridge computational insights with traditional expertise. By synthesizing theoretical frameworks with practical implementation strategies, this review provides researchers, industry stakeholders, and practitioners with essential knowledge to advance sustainable and efficient tea industry through targeted ML integration.