-

'Honeycrisp' apples were developed at the University of Minnesota and released in 1991[1]. It is a high-value apple cultivar widely planted across the United States apple production areas and worldwide. Its appeal lies in its distinctively crispy texture and sweet flavor, qualities that are highly prized by consumers. Consequently, growers can command a significantly higher wholesale price for 'Honeycrisp' compared to many other apple cultivars. In 2024, 'Honeycrisp' was number four in production in the United States with 9.8% of the total bushels produced behind 'Gala', 'Red Delicious', and 'Granny Smith' (USApple 2024). This is down from the 2023 data, where it was ranked 3rd and estimated at 28 million bushels[2]. Prices for 'Honeycrisp' were the highest among all cultivars for conventional production (

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ However, despite its market value, 'Honeycrisp' presents several production challenges that can impact profitability[5−8].

One major issue is its tendency for biennial bearing, which can create cash flow problems for farmers in off-years when the trees do not flower[9]. Another significant challenge is its susceptibility to bitter pit, a physiological disorder associated with calcium (Ca) deficiency[10,11]. Reports from packing houses, industry representatives, and fruit extension agents in New York, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Washington suggest that growers lose an average of 15%–25% of their 'Honeycrisp' crop to bitter pit annually, with losses rising to 60%–80% in extreme cases[6].

Rootstock selection is an important step for establishing 'Honeycrisp' orchards. For centuries, the use of rootstocks in apple cultivation was intended to propagate desirable scions through grafting[12]. Later, the discovery of dwarfing and early-bearing characteristics among certain European apple rootstocks[13] revolutionized apple growing by enabling the shift from large, inefficient trees to smaller, high-density configurations which greatly boosted orchard productivity[14]. As the popularity of 'Honeycrisp' rose among North American consumers, researchers and growers sought ways to enhance orchard productivity, disease resilience, and fruit quality for this variety[15].

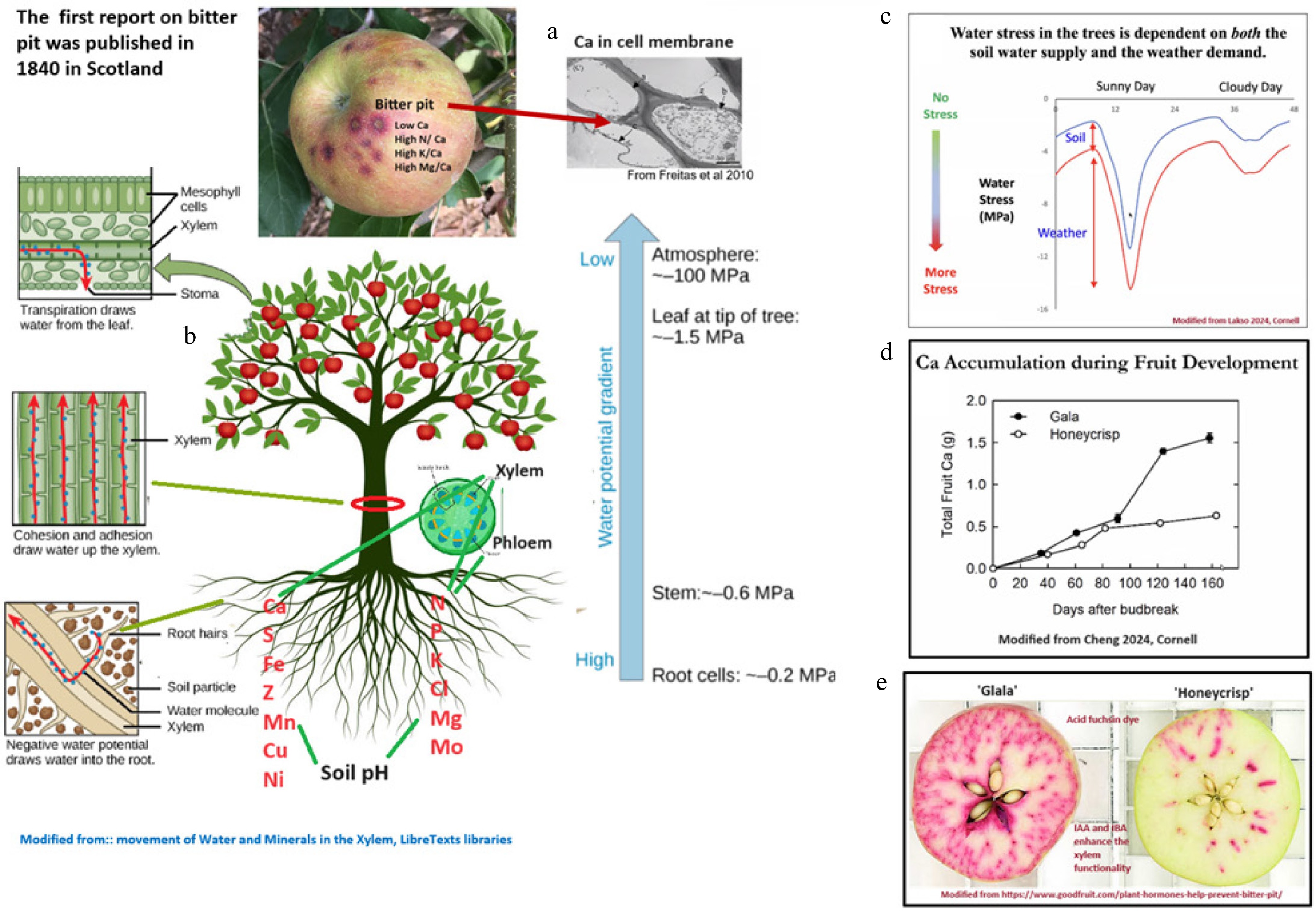

'‘Honeycrisp' is susceptible to a range of physiological disorders during storage and shelf life[8]. Bitter pit is a physiological disorder related to fruit calcium content that can be seen in the field at harvest but also develops during storage[16,17]. Different factors affect the development of the disorder, such as growing season, the orchard block, growing region, crop load, rootstock, fruit maturity, and storage temperature[8,11,18,19]. Cellular partitioning of calcium and cell wall properties have been linked to bitter pit incidence in 'Honeycrisp'[20]. Intercellular calcium (Fig. 1a) contributes to slower cell wall degradation during the ripening process in apple[21]. A recent transcriptomic approach identified candidate genes involved in organ abscission and stress response in tissues affected by bitter pit[22]. Different studies have identified bitter pit QTLs and markers associated with bitter pit[22,23]. Although bitter pit is related to calcium, excessive nutrients such as potassium or nitrogen can increase bitter pit incidence in fruit. 'Honeycrisp' has higher fruit potassium, magnesium, phosphorus, and nitrogen concentrations than other cultivars, which are less susceptible to bitter pit[24]. Since calcium is not phloem mobile, early xylem dysfunction in developing fruit has been suggested as a primary contributor to low calcium content and nutrient imbalance in developing fruitlets in 'Honeycrisp' apple[25,26]. However, more research is needed to clarify the underlying physiological reasons behind differences in cellular traits in 'Honeycrisp' compared to other cultivars[27].

Figure 1.

(a) Bitter pit, calcium deficiency, and calcium in cell membrane modified from de Freitas et al.[21]. (b) Mineral uptake from soil and movement in tree modified from Raven et al.[105]. (c) Stress water deficit on sunny and cloudy day. (d) Calcium accumulation in 'Gala' and 'Honeycrisp' apples during fruit development. (e) Xylem functionality in 'Honeycrisp' and 'Gala' apples modified from Griffith and Lake Ontario Fruit Program CU[106,107].

Extensive work has been done to manage pre and post-harvest bitter pit development, starting from soil and foliar mineral nutrient applications in early and late stages of fruit development[28]. Also, chemical[29] and non-chemical[16] prediction models have been developed to manage the disorder at harvest and during storage and help storage operators and marketers make appropriate marketing decisions[11].

Other disorders of 'Honeycrisp' include soft scald and soggy breakdown, which are low-temperature storage disorders[8]. The mechanism of soft scald development has been studied in relation to pre- and post-harvest factors[30−32]. In addition, protocols have been established to manage soft scald development during storage by conditioning the fruit for 1 week at 10 °C before transferring to 3 °C[33]. Adjustments to storage temperatures can be used to manage warm and chilling temperature disorders that have been investigated[34,35]. While a few studies have targeted soft scald development[30,32], the association between bitter pit and soft scald in relation to environment, rootstocks, mineral nutrients, and hormonal balance has not been studied yet. Omics approaches have been used to understand the etiology of different abiotic stresses, providing potential future gene targets. There have been recent omics approaches to develop predictive tools to improve storage management decisions with the goal of reducing crop losses[36].

The aim of this review article is to examine the challenges and successes associated with planting 'Honeycrisp' apples over the past 34 years. It also explores the cultivar's role as a parent in the development of many emerging apple varieties and its broader impact on sustainable apple production both in the USA and globally.

-

The apple cultivar 'Honeycrisp' has emerged as one of the top-produced and consumer-preferred apples. The apple market (wholesale commodity and direct-to-consumer) can be divided into two eras, with the key event being the release of 'Honeycrisp' in 1991[1]. The genotype was first selected as a seedling in a family row and identified as MN1711 at the University of Minnesota Horticultural Research Center (Excelsior, MN) from a cross made circa 1960 and planted in 1962. At that time, the recorded parentage was 'Honeygold' x 'Macoun', although it took decades to disprove this notation. Although apple trees are highly heterozygous and seedlings often vary phenotypically from their parents, key indicators have been called into question regarding the recorded parents[37]. SSR markers were used to identify 'Keepsake' (mother; 'Frostbite' x 'Northern Spy') as it was extant in the breeding program[38]. Later, SNP markers and associated haplotypes through pedigree analysis fully elucidated the parents as MN1627 (extinct father) and 'Keepsake'[39].

A complete history of 'Honeycrisp' acknowledges that this selection was slated for discard and removal due to poor horticultural performance, specifically winter injury. Fortuitously, David Bedford, who had been newly installed to breed apples, recognized the unfavorable site conditions and limited data, which led him to determine that the selection warranted a second chance. After another decade of evaluation, Luby & Bedford[1] sought and were awarded the plant patent for the variety. Described by Bedford as 'explosively crisp' in a press release in 1991[40], this distinctive characteristic truly revolutionized consumer expectations for a premium apple eating experience. Per capita apple consumption rose from the early 1990s until 2016, which aligned with the growth and expanded production of 'Honeycrisp' (and other branded varieties). However, consumers continued to demand 'Honeycrisp', as evidenced by the price received in the retail market, where it remained the ceiling through 2024, when pricing collapsed due to oversupply in the apple market. Production for 'Honeycrisp' globally includes Australia, Canada, China, Chile, France, Germany, Italy, New Zealand, and South Africa, with additional territories being explored. In Europe, the fruit is licensed under the trademark Honeycrunch®. 'Honeycrisp', like many red-skinned varieties, has produced bud sport mutations with greater red skin coloration favored by commercial producers who prefer a uniform appearance and by consumers who expect the higher red coloration more typical of its production in Minnesota. These novel sports have continued to create opportunities for 'Honeycrisp'.

Breeding goals at the University of Minnesota, and elsewhere, have focused on crisp texture, as this is a differentiating feature in the market and a hallmark of quality, and more importantly, a heritable trait from 'Honeycrisp'. As such, many offspring have become cultivars or important breeding parents because of their ability to retain crispness alleles with flavor, storage, disease resistance, and appearance traits. Despite concerted research to map a 'Honeycrisp' 'crispness' locus[41] or to define the phenotype succinctly (sensory evaluation, cell size, cell wall structure and fraction, crispness retention)[42] or the investigation of related candidate genes[43,44], no DNA test has been developed for routine screening of seedlings with this characteristic.

Sports and offspring

-

Apple producers have long desired improved, red-colored sport mutations for many cultivars (e.g., 'Red Delicious' or 'Gala'), as they are appealing to customers and solve harvest, packing, and marketing challenges. Red color is frequently a visual cue for ripeness to customers. Uniform fruit coloration on individual fruit reduces the complexity of product sorting and display. A uniform red color can lead to homogeneity across distribution territories, which supports brand recognition. In some club varieties, color parameters are dictated in the brand standards. So far, at least seven 'Honeycrisp' sports have been identified and registered, which have demonstrated an improvement in red coloration, such as 'LJ1000' (Royal Red Honeycrisp®), 'BAB 2000' FirestormTM, 'SO 7' ('Roseland RedTM'), and 'MinnB42' (Table 1). These color sports are important in areas where environmental conditions can limit anthocyanin accumulation due to warm nights in autumn. One sport has a distinctly earlier harvest date, allowing producers to deliver 'Honeycrisp' to markets sooner, and is marketed as 'DAS-10' (Premier Honeycrisp). All sport mutations are sold under the 'Honeycrisp' price look-up code (PLU 3283) at retail. The sports may be licensed by the intellectual property owner.

Table 1. 'Honeycrisp' sports.

Variety (trademark) Source Date Origin 'Cameron Select'® Various 2001 WA/USA 'Walden' Whole tree mutation of Honeycrisp 2005 NY/USA 'LJ-1000' (Royal Red Honeycrisp®) Whole tree mutation of Honeycrisp 2011 WA/USA 'BAB2000' (Firestorm®) Whole tree mutation of Honeycrisp 2014 WA/USA 'DAS-10' (Premier Honeycrisp®) Whole tree mutation of Honeycrisp 2014 PA/USA 'Lewis' Limb mutation of Honeycrisp 2015 WA/USA 'MinnB42' Limb mutation of Honeycrisp 2016 MN/USA 'SO 7' (Roseland Red™) Whole tree mutation of Honeycrisp 2021 VA/USA A review of the Fruit and Nut Registry[45−51] identified 35 F1 offspring of 'Honeycrisp' that are in the market (Table 2). This includes targeted, controlled crosses from breeding programs and those using open-pollinated (i.e., 'Honeycrisp') seed. Of course, the University of Minnesota's breeding program has been using 'Honeycrisp' as a parent for the longest (with records confirming its use beginning in 1986). They have advanced to the third generation of seedlings and are using complex pseudo backcross/inbreeding strategies to incorporate 'Honeycrisp' alleles for texture and storage attributes. Notable varieties which have been selected as seedlings include 'CN121' (SugarBee®), 'MAIA1' (EverCrisp®), 'Minneiska' (SweeTango®), 'NY1' (SnapDragon®), and 'WA38' (Cosmic Crisp®).

Variety (trademark) Parentage Date Origin 'Minneiska' (SweeTango®) 'Honeycrisp' × 'Minnewashta' 2008 MN/USA 'New York 1' (SnapDragon®) 'Honeycrisp' × 'NY752' 2011 NY/USA 'WA38' (Cosmic Crisp®) 'Enterprise' × 'Honeycrisp' 2012 WA/USA 'DS 3' (Pazazz®) 'Honeycrisp' O.P. 2013 WI/USA 'DS 22' (Riverbelle®) 'Honeycrisp' O.P. 2013 WI/USA 'CN 121' (SugarBee®) 'Honeycrisp' O.P. 2013 MN/USA 'CN B60' 'Honeycrisp' O.P. 2013 MN/USA 'Regal 13-82' (Juici®) 'Braeburn' × 'Honeycrisp' 2014 WA/USA 'MAIA1' (Evercrisp®) 'Honeycrisp' × 'Fuji' 2014 IN/USA 'DS-41' 'Honeycrisp' O.P. 2014 WI/USA 'CN B110' 'Honeycrisp' O.P. 2014 MN/USA 'MN55' (Rave®) 'Honeycrisp' × 'MonArk' 2016 MN/USA 'R10-45' 'Honeycrisp' × 'Cripps Pink' 2017 WA/USA 'Orléans' 'Empire' × 'Honeycrisp' 2017 Quebec/Canada 'MAIA12' (Summerset®) 'Honeycrisp' × 'Fuji' 2018 OH/USA 'MAIA11' (Rosalee®) 'Honeycrisp' × 'Fuji' 2018 OH/USA 'MAIA7' (Crunch-A-Bunch®) 'Honeycrisp' O.P. 2018 OH/USA 'Howell TC5 WF' 'Honeycrisp' O.P. 2018 WA/USA 'Howell TC4 WF' 'Cripps Pink' × 'Honeycrisp' 2018 WA/USA 'NY56' (Cordera®) 'Honeycrisp' × 'NY65707-19' 2019 NY/USA 'MAIA-T' (Scruffy®) 'Honeycrisp' O.P. 2019 OH/USA 'MAIA-L' (Ludacrisp®) 'Honeycrisp' O.P. 2019 OH/USA 'Honeysuckle Rose #1-6' 'Honeycrisp' × 'Simmons Gala' 2019 IL/USA 'NY73' (Pink Luster®). 'Imperial Gala' × 'Honeycrisp' 2020 NY/USA 'Regal D5-100' (Karma®). 'Huaguan' × 'Honeycrisp' 2020 WA/USA 'Howell TC7' (Lucy™Gem) 'Airlie Red Flesh' × 'Honeycrisp' 2020 WA/USA 'Regal D17-121' Honeycrisp' × Co-op 39 2021 WA/USA 'DS 102' 'Honeycrisp' O.P. 2021 WI/USA 'PremA003' (Posh®) 'Honeycrisp' × 'Sciros' 2021 New Zealand 'MN80' (Triumph®). 'Honeycrisp' × 'Liberty' 2021 MN/USA 'R204' (Kissabel®) 'Honeycrisp' × CR35-1 2022 France 'MAIA-SM' (Sweet Maia®). 'Honeycrisp' × 'Co-op 31' 2022 OH/USA 'D27-16' (Aura®) '8S6923' × 'Honeycrisp' 2022 WA/USA 'Wurtwinning' (Bloss®) 'Honeycrisp' × 'SQ 159' 2022 Netherlands 'WA 64' (Sunflare™) 'Honeycrisp' × 'Cripps Pink' 2023 WA/USA O.P. refers to open-pollinated. European offspring

-

The success of 'Honeycrisp' in the USA has spread internationally, including to Europe, where it has been grown and sold as HoneyCrunch® since the early 2000s. As in the USA, 'Honeycrisp' has become frequently used in breeding programs throughout Europe to develop cultivars with crunchy, juicy flesh and unique tastes for various markets. In addition, many 'Honeycrisp' offspring bred in the USA are now being grown in Europe as well, such as 'Minnieska' (SweeTango®), 'NY1' (SnapDragon®), and 'WA-38' (Cosmic Crisp®), under various licensing programs. During the 2023 season, 62.3% of the total apple trees planted were 'Honeycrisp' offspring in a region of Northern Germany, Niederelbe, up from 52% the year before[52]. Many of these cultivars have been rapidly adopted by industry and introduced as club varieties with significant marketing behind them, including cultivar-specific websites translated into multiple languages. However, research appears to be limited, or very location-specific, with most literature found in regional industry journals and focusing on pre-harvest factors. As such, published scientific literature on postharvest characteristics is lacking for most of these cultivars.

From gatherable knowledge, 'Wurtwinning' (Bloss®, 'Honeycrisp' x 'SQ 159'/MagicStar®/Natyra®) has been planted in Switzerland and green spots have been observed on the fruit. Another new cultivar, 'GS66' (Fraülein®, parents are unknown: suspected to be 'Honeycrisp' x 'Braeburn'), is susceptible to bitter pit and another unique skin pitting disorder named GS66-spot when grown in northern Germany, but initial storage experiments suggested otherwise good storability[53].

Although many new 'Honeycrisp' offspring in Europe show promising storability, the available observations remain preliminary, despite substantial plantings and industry investment. In some cases, physiological disorders and challenging storage have only been discovered after industry investment has begun in earnest. In Norway, production of two cultivars, 'Wursixo' (Eden®) and 'Wuranda' (Fryd®) with 'SQ-159'/MagicStar®/Natyra® x 'Honeycrisp' parentage has started and rapidly increased in recent years, with commercial planting occurring before thorough postharvest studies were conducted[54].

-

Rootstocks are considered an important factor in controlling vegetative growth, fruit development, and fruit mineral nutrient content[7,55,56].

Early evaluations suggested that apple rootstocks might play a more significant role in fruit quality and productivity than initially believed. Certain rootstocks, such as Geneva 935 (G.935) and G.969, demonstrated the ability to produce balanced, productive trees with fewer apples affected by bitter pit[57]. Building on this early data, a multi-state field trial featuring 'Honeycrisp' as the scion was conducted using a diverse set of rootstocks. This trial aimed to identify rootstocks that could mitigate 'Honeycrisp's' tendency for weak growth while maintaining an optimal crop load, an essential factor for fruit quality surpassing nitrogen's role[58].

The trials revealed that diverse rootstocks significantly influence leaf and fruit nutrient concentrations, particularly critical ratios like potassium-calcium (K/Ca), magnesium-calcium (Mg/Ca), and nitrogen-calcium (N/Ca), which are closely tied to bitter pit development. This nutrient effect, observed during the establishment phase[59], was confirmed in subsequent multi-year, multi-location studies[60−62]. Inherently low calcium transport capacity in 'Honeycrisp' amplifies rootstocks' impact, emphasizing the importance of nutrient uptake and transport as key objectives in breeding programs[60,63].

Furthermore, rootstocks affect soil pH interactions, phytohormone levels, stress tolerance, tree architecture, and graft union strength. For example, G.41 produces weaker unions while G.214 forms stronger ones[64]. Overall, rootstock choice profoundly influences productivity, disease resilience, fruit quality, and orchard profitability. Options include G.214, G.935, G.969, B.10, and G.890 optimal for vigor, productivity, and nutrient balance.

Donahue et al.[65] suggested that bitter pit performance of a rootstock should be a major consideration when choosing a rootstock for a new 'Honeycrisp' orchard. Islam et al.[20] reported that B.10 rootstock had lower bitter pit incidence at harvest and during storage compared with other rootstocks, and was associated with higher Ca and lower Mg concentrations as well as the water-insoluble pectin fractions in 'Honeycrisp' fruit compared with those from trees grafted on G.41 and V.6 (Vineland series) rootstocks. Others have found that rootstocks have a significant impact on the Ca, K, and K/Ca ratio in the scion tissues, and the K/Ca in the fruit was tightly correlated with bitter pit incidence[66].

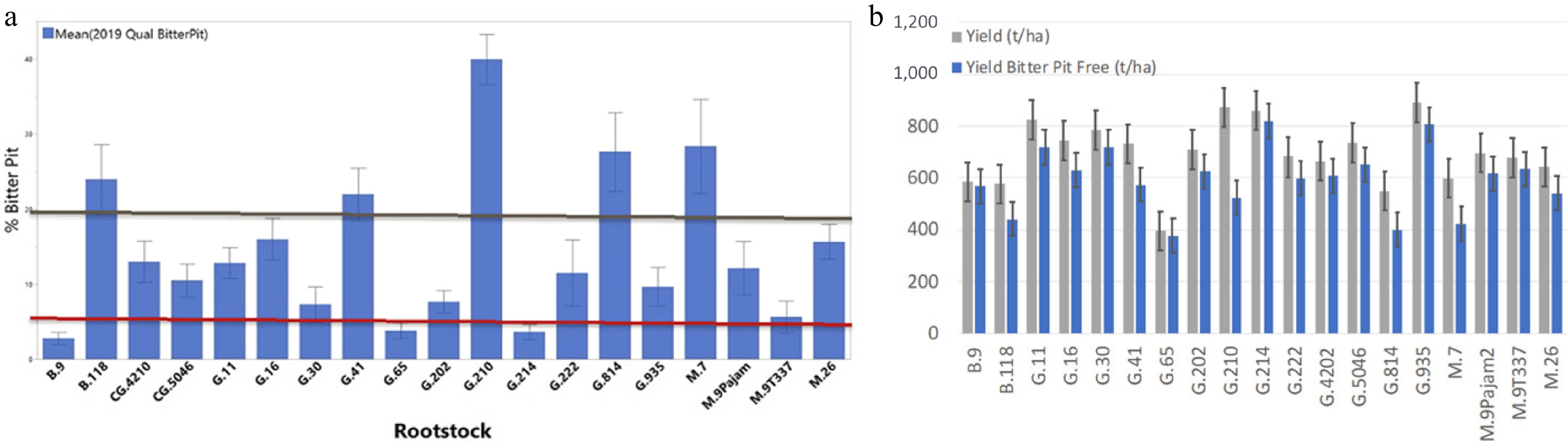

Previous research[66−69] investigated the influence of rootstocks on the mineral nutrient profile and bitter pit incidence in 'Honeycrisp' apples. Certain rootstocks result in higher potassium (K) and nitrogen (N) levels in fruit, while the ratio of K/Ca or N/Ca is elevated in some rootstocks. Rootstocks vary in their efficiency in taking up K and N, which influences fruit quality and bitter pit occurrence, with some rootstocks leading to higher incidences of bitter pit in the fruit (Fig. 2)[6,70]. Four long-term field trials conducted in Geneva, NY, measured total yield, bitter pit incidence, and crop value across various rootstocks. Rootstocks such as B.9 showed lower K uptake and had lower bitter pit incidence but lower yields. Rootstocks like G.41 and G.11 exhibited higher K uptake and greater vigor, resulting in higher yields but more bitter pit in certain years[71]. G.214, with similar vigor to G.41 but lower K uptake, resulted in low bitter pit risk. Results showed that rootstocks like B.9, B.10, G.969, and G.214 consistently had lower bitter pit incidences. A negative correlation was observed between calcium concentration and bitter pit, while a positive correlation existed between K/Ca ratio and bitter pit. Rootstocks that consistently had low bitter pit also had higher calcium levels and/or lower K/Ca ratios[72]. The cause of differences in K and N uptake efficiency remains unclear but is likely related to rootstock vigor and root system size. In selecting a rootstock for 'Honeycrisp,' the incidence of bitter pit is only part of the equation; total cumulative yield and crop value must also be considered[55,73]. Robinson et al.[6] found that B.9 had low bitter pit incidence but also lower cumulative yield, making other rootstocks more economically viable. Matching rootstocks to scion variety in a 'designer rootstock' approach can help optimize fruit size and reduce bitter pit incidence. Rootstocks with high K uptake, like G.11 and G.41, are ideal for small-fruit cultivars such as 'Gala', while rootstocks with low K uptake, like G.214 and G.969, are better for bitter pit-sensitive cultivars like 'Honeycrisp'[6].

Figure 2.

(a) Bitter pit incidence of various rootstocks on mature 'Honeycrisp' trees at Geneva, NY, in 2019. B.9, G.65, and G.214 had low bitter pit incidence (< 5%) while B.118, G.41, G.210, G.814, and M.7 had high bitter pit incidence (> 20%). (b) Total yield and yield of bitter pit-free fruit of 'Honeycrisp' on 19 rootstocks over 16 years at Geneva, NY, USA. Modified from Robinson et al.[6].

'Honeycrisp' is known to have low vigor, which, when grown in organic systems, requires additional attention. If 'Honeycrisp' is grown on a dwarfing rootstock under organic production, poor weed control can lead to reduced growth and low crop yields[74]. Several Geneva® series rootstocks, especially G.890, have been shown to have greater productivity under organic management, and should be used for organic 'Honeycrisp' plantings[75].

-

Soil management challenges have been the subject of extensive research over many years, with the findings meticulously documented and shared[76,77]. Soil acidity, with pH below 5.5, impacts 'Honeycrisp' apple productivity, resulting from precipitation-driven leaching, replacing essential cations like potassium and calcium with hydrogen and aluminum, especially in regions where rainfall exceeds evapotranspiration[78]. Preplant soil preparation for 'Honeycrisp' apple orchards focuses on soil pH[69,79], calcium (Ca) content, potassium (K) content, and organic matter. Optimal soil targets are a pH of 7.2, 6,000 kg/ha of Ca, 300 kg/ha of K, and 2%–3% organic matter[6]. Soils high in K or organic matter, > 500 kg/ha K and > 4% organic matter, are difficult to manage for low bitter pit incidence[6]. In the Western US, soils are often high in K, while some Eastern US soils are too rich in organic matter, creating challenges for successful 'Honeycrisp' growth. Differences in solubility and mobility of soil potassium and their availability to plants are explained[80]. To address low Ca and pH in Eastern US soils, intensive liming before planting is recommended, followed by bi-annual lime applications post-planting. Honeycrisp requires higher Ca levels than other cultivars, with at least 6,000 kg/ha of Ca in the top 30 cm. Soil pH should be raised to 7.2, a level shown to promote low bitter pit incidence and strong tree growth[69]. For soil amendments, calcitic lime (CaCO3) is preferred over dolomitic lime or gypsum, as dolomitic lime adds magnesium[81], which can increase bitter pit, while gypsum is a source of less soluble Ca[6].

Annual fertilization standards

-

Current annual fertilization standards of 'Honeycrisp' in NY State are based on leaf nutrient values[82]. Leaf samples should be collected earlier than for other varieties, as 'Honeycrisp' stops shoot growth earlier, affecting leaf nutrient concentrations[83]. The recommended leaf N concentration is 2.0% of dry weight, similar to 'McIntosh'. For blocks with less than 2.0% N, apply 40–50 kg of N/ha, while blocks with 2.0%–2.25% should receive 20 kg/ha. No N should be applied if leaf N exceeds 2.25%[6]. Fertilization should occur early in the growing season, with split applications at bud break and petal fall[84]. Post-harvest foliar N can be applied for low vigor trees, particularly for those with leaf N under 2%. Potassium fertilization for 'Honeycrisp' is more cautious than for other varieties due to its tendency to develop bitter pit at high K levels. Cheng and Miranda Sazo[82] found that 'Honeycrisp' has a lower K requirement than 'Gala'. Thus, the optimal leaf K range for 'Honeycrisp' is 1.0%–1.1%, lower than varieties like 'Gala' or 'Empire'. If leaf K is below 1.0%, apply 60–80 kg K2O/ha; for levels between 1.0% and 1.3%, apply 30–50 kg K2O/ha. No K should be applied if leaf K exceeds 1.3%[6].

Calcium is managed through preplant calcitic lime applications and bi-annual lime applications post-planting. 'Honeycrisp' requires higher leaf Ca (1.5%–2.0%) than other cultivars, so soil and leaf Ca levels should be monitored regularly. Fruit peel sap analysis in early July is also recommended to assess nutrient balance, particularly the K/Ca ratio. If the K/Ca ratio exceeds 25, growers should reduce K applications and increase foliar Ca sprays. If the ratio is below 25, the recommendation is to apply 40–50 kg K2O/ha for optimal fruit size and quality[6].

Crop load management

-

Crop load is crucial for determining yield, fruit size, and the incidence of bitter pit in 'Honeycrisp' apples[85]. It is also linked to biennial bearing, making its management critical for consistent annual production[86]. Low crop load can increase bitter pit, while high crop load often leads to biennial bearing. During an 'on-year', when there is often a heavy crop load, without thinning, fruit size is lower, ripening is delayed, and fruit color development is poor[62]. Flower bud formation occurs during the previous growing season[87]. When fruit is thinned early during fruit development, it has a substantial effect on competing fruits and shoots. Thus, achieving an optimal crop load each year is essential for minimizing bitter pit and ensuring annual yields[88]. Crop load is managed through pruning, chemical thinning, and hand thinning[89].

Precision pruning is the first step in crop load management[90]. Research indicates that when flower bud load is too high, chemical thinning alone may not reduce crop load sufficiently[91]. Pruning should focus on removing enough flower buds to allow chemical thinning to achieve the target fruit number. It is suggested to count floral buds and leave around 80% more buds than the target as insurance against frost or poor set[92].

Precision chemical thinning is essential for preventing biennial bearing and ensuring fruit quality[88]. Early thinning at bloom and petal fall is critical because fertilized flowers produce gibberellin (GA), which inhibits flower bud formation for the next year[93]. However, Elsysy & Hirst[94] show that seeds do not play a direct role in regulating flower formation. By thinning blossoms and fruitlets early, seed number and GA concentration are reduced, promoting flower formation for the next season. Two bloom sprays of ammonium thiosulfate or lime sulfur plus oil, followed by naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) + carbaryl spray at petal fall, help control crop load. If pruning has been effective, this thinning strategy should yield a crop close to the target, requiring minimal hand thinning. Overcropped trees can suffer from poor fruit quality, including reduced color, delayed maturity, and decreased fruit dry matter[58,88]. If biennial bearing occurs due to improper thinning or frost, strategies like deficit irrigation and delayed hand thinning can help manage oversized fruit.

The biennial fruit-bearing nature of 'Honeycrisp' is particularly difficult for organic producers because the main plant bioregulators used for fruitlet thinning are unavailable due to being synthetically manufactured[95]. This leaves growers with fewer sprayable options, most of which rely on caustic materials to either disrupt fertilization during flowering or cause a transient but severe phytotoxic stress on the entire tree that results in fruitlet abortion[96]. Liquid lime sulfur (calcium polysulfide) is the most common material used for thinning under organic production, but it can result in fruit peel russeting that devalues the fruit in wholesale markets[97]. Other caustic materials, such as salts, biofungicides, and solvents, have been trialed with limited success[98,99]. A gibberellin product (ProVide; Valent BioSciences, LLC) has been formulated for use in organic production. Some research has shown that gibberellins can be applied in the off-year of a biennial bearing cycle to encourage flower bud formation and minimize low yields during the off-year[100]. However, a heavy crop load will likely overwhelm the effects of exogenously applied gibberellins, so it must be done in coordination with other crop load management approaches[101].

Return bloom management

-

To overcome biennial flowering, growers have traditionally applied four summer sprays of either 10 μL/L NAA or 473 mL Ethephon (Ethrel®), typically applied starting on June 21 (under NY conditions), when fruits are 35 mm in diameter. While this program has worked well for other biennial varieties, it has proven less reliable for 'Honeycrisp'[102]. Recent research suggests two key reasons for this inconsistency:

1. Timing of flower initiation: Flower initiation for 'Honeycrisp' occurs much earlier than other cultivars, beginning around 30 d after bloom, with peak initiation between 45 and 55 d. The traditional spray timing often misses this critical period. Thus, initiating the summer sprays earlier, closer to the flower initiation period in mid to late June, could improve consistency (Francescatto et al., unpublished data)[9].

2. Gibberellin (GA) load: When the number of fruit and seeds is high, the resulting high gibberellin production can inhibit flower initiation[103], counteracting the flower-promoting effects of NAA or Ethrel®. In years with fewer fruit or seeds per fruit, the sprays are more effective, as the GA load is lower.

To address these issues, researchers recommend precision pruning to limit the initial flower bud load to no more than 1.8 times the target fruit number. This helps avoid excessive GA levels and supports flower bud initiation. Additionally, bloom thinning and petal fall thinning should be done early to reduce fruit numbers, ensuring that flower initiation is not hindered by high GA levels. In recent trials, starting Ethrel®sprays earlier, at the 16 mm fruit size stage, has shown better results for return bloom than the traditional timing of starting the sprays at 35 mm fruit size. Four sprays at 10-d intervals, starting at 150 µL/L and escalating to 300 µL/L, have been effective in promoting bloom in the 'on' year. However, this approach requires careful control of fruit numbers and seed load to avoid excessive GA. Ethrel® should only be applied when temperatures are below 26 °C to minimize the risk of unintentional thinning[6].

Irrigation management to manage growth and nutrition partitioning

-

The uptake of calcium (Ca), potassium (K), and magnesium (Mg) by apple trees is influenced by soil moisture levels. In dry soils, the uptake of these cations is limited, leading to deficiencies, such as K leaf deficiency in August, even if soil K levels are adequate. Conversely, excessively wet, waterlogged soils hinder root function and nutrient uptake. K can be transported through both the xylem and phloem, while Ca is only transported in the xylem, requiring water movement into the fruit to prevent issues like bitter pit (Fig. 1b). Early in the season, fruitlets transpire through stomates, facilitating greater water and Ca movement. However, as stomata become non-functional later in the season, this transport is reduced. Research indicates that increased water supply during the season can improve fruit size and red color but negatively affect fruit firmness, soluble solids, and increase bitter pit and rot incidence[104]. Bitter pit is particularly influenced by water stress during early season (near petal fall) and mid-season (early July) (Fig. 1c), with more stress leading to higher bitter pit after storage. The condition is worsened by low crop loads. Water deficits from July 3–17 result in high bitter pit incidence, while adequate water supply and higher crop loads reduce it. Excessive water, on the other hand, decreases root function and Ca uptake, worsening bitter pit.

Deficit irrigation (DI) can be used as a tool to limit fruit growth and control bitter pit in 'Honeycrisp'[108]. Deficit irrigation imposes predetermined periods of soil or plant water deficit to improve fruit quality, decrease vigor, or conserve water[109]. With 'Honeycrisp', reduced water supply in the last half of the season helps reduce K uptake and reduces bitter pit incidence. Dry climates with little to no rainfall are more successful at maintaining good DI because growing environments with higher rainfall lose their ability to control water supply.

To prevent bitter pit in 'Honeycrisp', irrigation should begin early in the season (May–June) and continue through July to ensure adequate Ca uptake, and only through June in hotter, irrigated environments in the Western US. However, irrigation should be suspended after August 1 to prevent excessive K uptake, which worsens the K/Ca ratio and leads to bitter pit. Under conditions that will promote large fruit and in irrigated, hot environments, deficit irrigation should start earlier, closer to July 1[108]. Deficit irrigation during fruit cell expansion in the later season can reduce bitter pit incidence, although conditions such as rainfall remain uncontrollable. Proper early nutrient uptake is essential for reducing bitter pit. Deficit irrigation is a valuable tool to use when crop loads are low or when bitter pit risk is high in orchards with higher vigor.

Foliar Ca sprays to manage bitter pit

-

Foliar calcium (Ca) sprays can slightly increase fruit Ca levels, typically by around 10%, but this is usually insufficient to fully address Ca deficiencies, since calcium is immobile in the phloem. The effectiveness of calcium sprays relies on fruit contact to increase overall fruit calcium content[110]. When proper soil Ca levels and adequate irrigation are maintained, foliar sprays can significantly reduce bitter pit. The most effective Ca sprays are applied during the second half of the season, after xylem dysfunction in the fruit limits Ca movement into the fruit (Fig. 1e). There are many different commercial calcium sprays. More commonly, calcium can be sprayed as calcium nitrate (Ca[NO3]2)[111], calcium carbonate (CaCO3)[112], or calcium chloride (CaCl2)[28,113]. Calcium chloride is the most widely used calcium spray because it is the least expensive and most effective spray available[114,115]. Although calcium sprays have been shown to be effective, the amount of calcium absorbed and the effect of weather or development on the absorption efficiency are less understood. Kalcsits et al.[110] reported that calcium spray adhesion was greater during early development for 'Honeycrisp'. The decrease in spray adhesion and increase in fruit surface area as fruit development progressed provided the conditions for a consistent amount of calcium spray to adhere to each fruit throughout the growing season. Their results demonstrated that frequent calcium sprays are required to increase fruit calcium concentrations. The current recommendations for 'Honeycrisp' include eight to ten cover sprays of calcium chloride (CaCl2), compared to five to six sprays for other bitter pit-prone varieties. Various Ca products, such as STOPIT™ (calcium chloride), Sysstem©-CAL (calcium phosphite), Cell Power© Calcium Platinum (calcium nitrate), and Ele-Max© Calcium FL (calcium carbonate), were tested over three years[6]. STOPIT™ showed the best results in reducing bitter pit, both at harvest and after storage, outperforming other products. Based on these trials and other studies, CaCl2 is considered the most effective spray form[28,116]. A total of 10–13 kg/ha of Ca per season is recommended in high-density orchards; this may also vary depending on soil composition and leaf mineral analysis. However, CaCl2 can cause fruit damage if sprayed too early (before mid-June), so it should only be applied once fruit reaches 30 mm in size. Sysstem©-CAL, on the other hand, has been found safe for early-season sprays without causing fruit injury.

-

The link between low calcium content in fruit and an increased risk of bitter pit has long been established, and foliar applications of calcium products have been shown to reduce the development of bitter pit in susceptible cultivars (Fig. 1d)[117], including 'Honeycrisp'[28]. These relationships have also led to the development of prediction models for various cultivars. While some models focus solely on calcium, most incorporate other minerals, such as magnesium, potassium, and nitrogen, into their predictions[118,119]. Bitter pit incidence is related to high ratios of Mg/Ca in 'Fuji' apples[120], Mg + K+ N/Ca in 'Honeycrisp' apples[16], Mg + K/Ca in 'Cox Orange Pippin'[121] and 'Granny Smith' apples[21], and Mg/Ca and K/Ca in 'Catarina' apples[122]. However, regression coefficients vary across studies, ranging from as low as 0.4 to as high as 0.9[16,123,124]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that hormone concentrations and their interactions play a pivotal role in regulating xylem dysfunction, which is closely associated with the nutrient imbalances commonly observed in bitter pit[26].

In addition to mineral-based methods, several non-mineral techniques for predicting bitter pit have been developed. These include treatments with magnesium salts, such as vacuum infiltration with MgCl2 in 'Braeburn' apples, which predicts bitter pit incidence after storage[125]. Ethylene treatments accelerate ripening through methods such as ethephon dipping or acetylene gas fumigation[126,127]. A passive method, where fruit is stored at warm temperatures to allow bitter pit development before harvest, has also been shown to reliably predict bitter pit in 'Golden Smoothee' apple[124].

A variety of methods have been developed to predict and manage pre- and post-harvest bitter pit in 'Honeycrisp' apples, including:

Shoot length and N/Ca ratios

-

The method relies on correlating the average of current season terminal shoot length, with moderate branch angles, measured using five terminal shoots per tree from 20 trees per orchard after terminal bud set, with the fruit peel N/Ca ratio taken 3 weeks before the anticipated harvest from the same 20 trees (60 apples per orchard in total) to predict bitter pit development during cold storage. The results show that bitter pit development consistently increases with higher N/Ca ratios and longer shoot lengths[16]. However, in a different study, the model underestimated the incidence of bitter pit[19].

Peel sap analysis method

-

Assessing bitter pit risk early in the growing season is crucial for timely mitigation, which reduces the fruit disorder at harvest and during storage. Current methods predict bitter pit risk shortly before harvest, limiting the ability to implement preventive measures. The peel sap analysis method measures K/Ca and N/Ca ratios from fruitlet peel sap. This method, conducted around 2 months after bloom, involves freezing the fruit peel at −80 °C to lyse the cells and then squeezing it to extract the juice. It is quicker, simpler, and more environmentally friendly compared to others. The K/Ca ratio helps categorize orchards into low, medium, or high-risk groups, while the N/Ca ratio provides similar categorizations. These results are available by mid-July, allowing growers to take action to reduce bitter pit risk. Mitigation strategies include increasing calcium sprays, avoiding certain growth regulators, reducing nitrogen and potassium applications, and increasing soil pH with lime[6]. This early prediction system offers a valuable tool for effectively managing bitter pit risk.

Passive method

-

The passive method, which involves collecting 100 fruits 3 weeks before the anticipated harvest and storing them at room temperature, has consistently produced reliable results across different orchards, regions, and successive years under New York and Pennsylvania conditions. Its simplicity makes it a powerful and dependable tool that growers and storage operators can easily use to predict the occurrence of bitter pit in 'Honeycrisp' apples during storage[11].

-

Sprayable formulas of 1-methycyclopropene (1-MCP) commercialized as Harvista™ and aminoethoxyvinylglycine (AVG) commercialized as ReTain® are plant growth regulators (PGRs) that inhibit ethylene action or biosynthesis to delay fruit drop and maturity. While effective for harvest management, these PGRs can worsen bitter pit development in susceptible orchards. Research shows that applying 1-MCP before harvest increases bitter pit, leather blotch, core browning, and CO2 injury. However, preharvest 1-MCP reduces senescent breakdown and wrinkled skin, signs of advanced maturity, and helps prevent soft scald during storage at 0.5 °C[18]. For fruit with a high K/Ca ratio from the peel sap analysis method, it is recommended to avoid using preharvest AVG or 1-MCP to prevent aggravating bitter pit[6].

Postharvest application of 1-MCP at the commercial rate can sometimes reduce greasiness. Still, it significantly increases the risk of leather blotch in fruit susceptible to bitter pit and that has also been treated with preharvest 1-MCP. Although the leather blotch is not fully understood, the effects of 1-MCP suggest that it may be linked to inhibited fruit ripening. Additionally, postharvest 1-MCP treatment has been shown to increase the incidence of internal carbon dioxide (CO2) injury in treated fruit. However, 1-MCP has no effect on fruit firmness in 'Honeycrisp'. Various studies have shown that changes in fruit firmness in 'Honeycrisp' apples are minimal, likely due to low polygalacturonase activity[128] associated with high turgor and cell wall integrity[27].

-

Color is a key factor influencing the harvest timing of 'Honeycrisp' apples, and anthocyanin accumulation in fruit peel follows the blush and stripe patterns[129]. Spot picking is performed two to four times during the harvest window, depending on the orchard, regional conditions, and preharvest treatments. Internal ethylene concentrations (IEC), starch indices (measured on a 1–8 scale), firmness, and soluble solids content (SSC) did not exhibit consistent changes over the 3-week harvest period. Additionally, 'Honeycrisp' apples are susceptible to stem punctures, with incidences reaching up to 18.5%. This susceptibility is unaffected by the timing of the harvest[130]. Harvest time has a strong impact on fruit susceptibility to physiological disorder development during storage[130]. Early harvest of 'Honeycrisp' apples may lead to the development of bitter pit, superficial scald, core browning, and internal CO2 injury[34,130,131]. Conversely, late harvest increases the fruit's susceptibility to soft scald, soggy breakdown, and flesh browning[8].

-

The increased production of 'Honeycrisp' apples has created a demand for extending their storability beyond 9 months[132]. Although fruit firmness decline can be low in air storage[128], various reports have indicated that fruit flavor often declines under commercial air storage conditions[133].

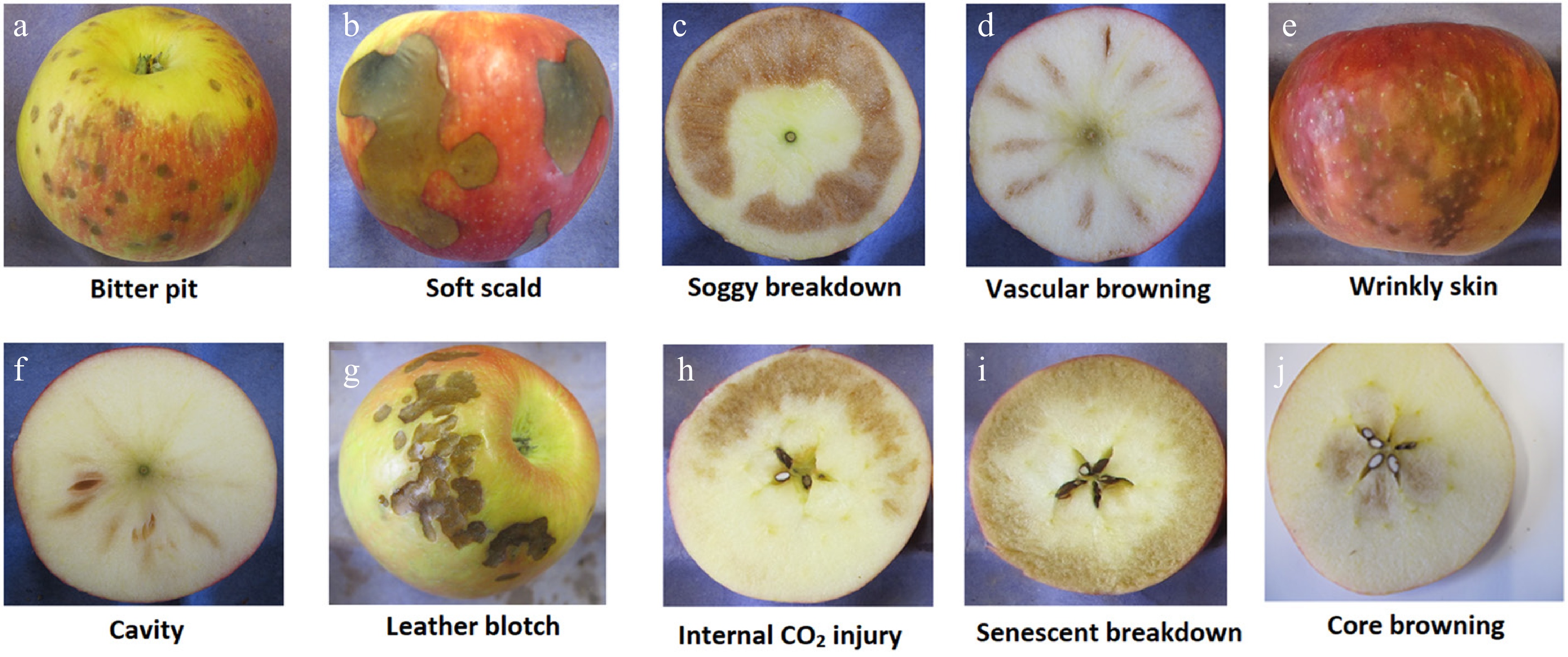

'Honeycrisp' apples are prone to numerous physiological disorders (Fig. 3), and several factors impact fruit quality during storage, including storage temperature, growing region, harvest timing, and storage regime[8,34,131]. Traditionally, 'Honeycrisp' apples have been stored at 3 °C following 1 week of conditioning at 10 °C to mitigate the risk of low-temperature storage disorders, such as soft scald and soggy breakdown. However, this method can increase the likelihood of bitter pit development in fruit in susceptible orchards[8]. Utilizing prediction models for bitter pit incidence provides valuable guidance for managing storage and marketing strategies[11]. It is not currently recommended to store 'Honeycrisp' apples at temperatures close to 0 °C[34]. Various studies have explored storage strategies based on the fruit's susceptibility to temperature-related disorders, such as bitter pit and soft scald. Bitter pit typically develops during the first month of storage, while soft scald begins after 1 month and continues throughout the storage period. A negative correlation between the development of soft scald and bitter pit has been observed over several years and across different regions[8]. However, attempts to manage storage disorders based on these interactions have not been successful[34]. According to preharvest bitter pit prediction models, fruit with a high likelihood of developing bitter pit was stored at 0.5 °C for varying durations before being transferred to 3 °C to address both disorders. The results showed inconsistent outcomes across years and orchard blocks. In one year, a linear increase in vascular browning susceptibility was observed with prolonged storage at 0.5 °C before transferring fruit to 3 °C[34].

Figure 3.

Physiological disorder development in 'Honeycrisp' apples during storage. (a) Bitter pit, (b) soft scald, (c) soggy breakdown, (d) vascular browning, (e) wrinkly skin, (f) cavity, (g) leather blotch, (h) internal CO2 injury, (i) senescent breakdown, and (j) core browning. Modified from Al Shoffe et al.[18].

Controlled atmosphere (CA) and dynamic controlled atmosphere (DCA) storage systems have recently been employed to store 'Honeycrisp' apples for over 9 months while maintaining fruit quality, flavor, and consumer preference[132−135]. However, the cultivar remains susceptible to internal CO2 injury[131,133]. In North America, the apple industry has historically mitigated CO2 injury through treatments such as dipping, drenching, or fumigation with the antioxidant diphenylamine (DPA)[136]. Since DPA is banned in Europe and for organically grown apples, and may eventually be restricted for conventionally grown apples in the USA, the industry must prepare alternative strategies[137].

One approach for mitigating internal CO2 injury involves delaying the start of CA and DCA storage by 4 weeks. During this period, fruit may be conditioned at 10 °C for 1 week, depending on the preharvest bitter pit prediction model. If the predicted bitter pit risk is high, conditioning is not recommended. After 1 week, the fruit is transferred to 3 °C, and 1 µL/L of 1-MCP is applied 24 h later. The fruit remains at 3 °C for 3 weeks before transitioning to CA or DCA storage[131,132].

For 'Honeycrisp' offspring and sports, there appears to be a recurring trend of releasing new cultivars before completing large-scale postharvest evaluations. This is concerning given the need to understand optimal storage practices, particularly when the parent cultivar, like 'Honeycrisp', is prone to physiological disorders. To ensure a comprehensive understanding of both growth and storage characteristics, multi-year storage trials should be incorporated into the final stages of cultivar testing before commercialization.

-

To optimize 'Honeycrisp' apple production, the apple industry should implement strategies to mitigate biennial bearing, bitter pit, and other physiological disorder losses, including careful nutrient management and storage protocols. Selecting the right rootstocks and implementing high-density planting configurations can enhance orchard productivity. Ongoing research into physiological traits and omics approaches may further refine best practices. Since the release of the 'Honeycrisp' apple in 1991, an analysis of the Google Scholar database indicates that approximately 34% of published papers on Malus domestica specifically reference 'Honeycrisp' compared with other cultivars. Given the high market value of 'Honeycrisp' and its offspring as high-value emerging cultivars, in both conventional and organic production, continued investment in predictive models and sustainable management practices will be key to maintaining profitability. Addressing production challenges through integrated techniques will ensure long-term success for growers while supporting the cultivar's role in shaping the future of apple cultivation.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Al Shoffe Y; data organization: Al Shoffe Y; literature search: Al Shoffe Y, Robinson T, Fazio G, Follett E, Clark M, Luby J, Bedford D, Kalcsits L, Peck G; manuscript drafting/revision: Al Shoffe Y, Robinson T, Fazio G, Follett E, Clark M, Luby J, Bedford D, Kalcsits L, Peck G. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Journal of Fruit Research for covering the Article Processing Charges.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Al Shoffe Y, Robinson T, Fazio G, Follett E, Clark M, et al. 2025. 'Honeycrisp': the challenge of the apple crisp revolution. Fruit Research 5: e039 doi: 10.48130/frures-0025-0030

'Honeycrisp': the challenge of the apple crisp revolution

- Received: 20 June 2025

- Revised: 02 September 2025

- Accepted: 05 September 2025

- Published online: 01 November 2025

Abstract: 'Honeycrisp' apples are a crisp cultivar known for their unique texture and flavor. This cultivar is considered revolutionary in the world of crispy apples due to its high value and strong consumer preference. Many new cultivars have recently been developed using 'Honeycrisp' as a parent. However, growing, producing, storing, and marketing 'Honeycrisp' apples present significant challenges. A holistic approach to 'Honeycrisp' production will be discussed, covering aspects such as soil health, rootstocks, orchard management, environmental factors, physiological disorder development, storage protocols, and marketing strategies for sustainable production.

-

Key words:

- Apple (Malus × domestica) /

- Breeding /

- Rootstock /

- Soil health /

- Orchard management /

- Harvest management /

- Fruit quality /

- Storability /

- Shelf life /

- Sustainability