-

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine, MT) is a recently discovered phytohormone that affects various physiological aspects in humans, such as sleep, mood, body temperature, endocrine hormone levels and the immune system[1]. Melatonin also plays important roles in plants[2]. As a plant growth regulator (PGR), it regulates vegetative growth and reproduction[3,4]. Furthermore, it can extend the shelf life of fruits and maintain post-harvest fruit quality[5]. Additionally, melatonin is considered an antioxidant, playing a crucial role in scavenging reactive nitrogen and oxygen species (ROS)[6,7]. Its role in conferring tolerance to various biotic and abiotic stresses, including drought[8], high temperatures[9], salinity[10], cold[11], and microbial infections (fungi, bacteria, and viruses)[12], has been extensively studied. In recent research, melatonin has even been employed to reduce pesticide residues[13] and heavy metal accumulation[14]. The biosynthesis of melatonin starts with tryptophan and comprises four consecutive reactions catalyzed by at least six enzymes, including tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH), tryptophan decarboxylase (TDC), tryptophan 5-hydroxylase (T5H), serotonin N-acetyltransferase (SNAT), N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine (ASMT), and caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT)[15]. With the increasing research on melatonin, in recent years, research on the function of COMT genes has become increasingly prominent[16,17]. Research has found that COMT enzymes in Arabidopsis and rice are located in the cytoplasm[18,19], while COMT enzymes in tomatoes are also located in the cytoplasm[20].

The formation and development of pollen in sexually reproducing plants are the foundation for robust fruit setting and development, as well as an important guarantee for production and breeding. There is also some understanding of the transcriptional regulation mechanisms of genes related to anther development and pollen formation in some higher plants[21]. To achieve successful pollination, pollen germination plays an important role[22]. The formation and development of pollen comprises several distinct stages[23]. Pollen grains originate from the microspore mother cells within the anther's pollen sacs. Each microspore mother cell undergoes meiotic division to yield a tetrad of microspores. These microspores are simultaneously released, coalesce into a large vesicle, and then proceed through the first mitotic division (pollen mitosis I, PM I) to produce a bicellular pollen grain composed of a large vegetative cell and a small generative cell. Mature tomato pollen is binucleate, and the generative nucleus undergoes a second mitotic division during pollen tube growth[24,25]. Pollen development is influenced by various factors, including irregularities in the tapetum layer[26,27], alterations in the cytoskeleton[28], abnormal hormone metabolism[29], changes in sugar utilization[26,30], and the presence of reactive oxygen species[31]. Early research into the potential role of melatonin in flowering processes focused on the short-day plant, Chenopodium rubrum. Application of exogenous melatonin before the induction of dark periods was found to suppress flower induction by an average of 40%−50%[32,33]. The study by Shi et al. initially established a direct link between melatonin and floral transition, demonstrating that exogenous melatonin delayed flowering in Arabidopsis[34]. Melatonin levels peak in Datura metel flowers as they reach maturity, protecting their reproductive tissues[35]. The exogenous application of melatonin has been found to confer protective effects on peony flowers under light stress, on cut Anthurium flowers during low-temperature storage, and on tomato high-temperature-induced sterility[36−38]. Melatonin pretreatment (50 μM) significantly improved pollen viability in Plantago ovata under lead (Pb2+) stress[39]. Flowering in apple trees is associated with declining melatonin levels. However, an increase in melatonin within a specific range also led to enhanced flowering[40].

Prior research on the role of melatonin in flower development has primarily involved exogenous melatonin, which may not fully replicate the impacts of endogenous melatonin on flower development[41].

In this study, the impact of the deletion of the key endogenous melatonin biosynthesis gene, SlCOMT1, on pollen development was investigated. This provides a theoretical foundation for the management of tomato flowering and the further enhancement of tomato yield and quality. Additionally, it sheds light on the significant role of melatonin in the maturation process of tomato pollen grains for the first time. This research may offer a new perspective for the study of pollen development in vegetable crops, with tomato pollen as a representative model.

-

The experiments were conducted in the Horticulture Laboratory of the College of Agriculture, Guizhou University (Guiyang, China). The plant materials included the wild-type tomato 'Micro-Tom' (WT) and our research group previously used the CRISPR/Cas9 system to construct a SlCOMT1 gene knockout homozygous mutant material with 'Micro Tom' as the background, denoted as slcomt1[42]. The SlCOMT1 knockout lines were generated using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing. Using the CDS sequence of SlCOMT1 (Solyc03g080180) as a template, to ensure efficient disruption of gene function: a dual-gRNA strategy was employed, with one gRNA targeting the dimerization domain (Target 1) and another targeting the methyltransferase active domain (Target 2) of SlCOMT1 (Solyc03g080180). Two knockout targets were designed. Oligo sequences were generated online from the gRNA target sequences via the website www.biogle.cn. The primers used for the sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Constructs were delivered into tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) via Agrobacterium tumefaciens (EHA105)-mediated leaf disc transformation, following established protocols for tomato genetic transformation. Primary transformants (T0) were selected based on antibiotic resistance, followed by RT-PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing of a 544-bp fragment spanning both target sites to confirm edits. Positive plant material identification primers are listed in Supplementary Table S2. All phenotypic and molecular analyses in this study were performed using homozygous mutants. To ensure genetic stability, T0 plants were self-pollinated to produce T1 segregating populations. T1 progeny were genotyped by PCR amplification of the target region and Sanger sequencing. Individuals carrying identical biallelic mutations at both loci were identified as homozygous. Stable inheritance of the mutations was further confirmed in the T2 generation (100% mutant allele transmission in selected lines). Mutation modes: validated by sequencing, was large-fragment deletions between the two gRNA sites, resulting from NHEJ-mediated repair of dual Cas9-induced DNA breaks. The material used in this experiment was the T2 generation. Seeds were surface-sterilized and germinated, and after whitening, they were sown in a growth chamber with an 18-h light/6-h dark cycle at 25 °C. Once the seedlings reached the three-leaf stage, they were transplanted and managed following standard tomato cultivation practices.

Experimental methods

Pollen viability assessment

-

Pollen viability of tomato was assessed using the Fluorescein diacetate (FDA) staining method. A stock solution of FDA was prepared by dissolving FDA (Yuanye Shanghai, S19128) in acetone to a concentration of 2 mg/mL, and it was stored at 4 °C in the dark. A 0.01% working solution was prepared by diluting the stock solution with 0.5 M sucrose. Freshly opened morning flowers were chosen, and a drop of the FDA working solution was applied to a glass slide. By gently tapping the anthers with forceps, the pollen was released into the staining solution. The slide was then placed in a humid chamber at room temperature in the dark for 1 h. Subsequently, it was covered with a coverslip and observed under a fluorescence microscope (Nexcope, NIB600) for examination and photography. The experiment was designated with three repeated zones named slcomt1-1, slcomt1-2, and slcomt1-3. Each group consisted of 12 plants, with three flowers taken from each plant. The data included three biological replicates, and each biological replicate had three technical replicates.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of pollen morphology

-

Freshly opened morning flowers were collected, and pollen was gently tapped from the anthers onto a metal specimen holder coated with double-sided adhesive using forceps. The pollen was evenly distributed on the holder's surface using a toothpick. Subsequently, the samples were gold-sputtered for 5 min in an ion sputter coater (Eiko, IB-5, Japan). The pollen morphology was observed using a scanning electron microscope (Hitachi, S-3400N, Japan). The experiment was designated with three repeated zones named slcomt1-1, slcomt1-2 and slcomt1-3. Each group consisted of 12 plants, with three flowers taken from each plant. The data included three biological replicates, and each biological replicate had three technical replicates.

Floral anatomy observation

-

Open flowers were dissected by separating their petals, stamens, pistils, and sepals using forceps and razor blades. The dissected parts were observed and photographed using a stereomicroscope (Leica, S9i).

In vitro pollen germination assay

-

Freshly opened flowers from the same day were used for the pollen germination assay. Pollen grains were gently tapped onto glass slides using forceps. In a 50 μL pollen germination medium (containing sucrose: 120 g/L, H3BO3: 50 mg/L, Ca(NO3)2·4H2O: 300 mg/L, MgSO4·7H2O: 200 mg/L, KNO3: 100 mg/L; with the addition of agar powder to achieve a final concentration of 0.1%), the pollen grains were evenly dispersed. A coverslip was placed over the pollen, and the prepared slides were put in a Petri dish lined with moist filter paper. The dishes were then incubated at room temperature in the dark. Observations and photographs were taken using a microscope (Leica, icc50w) at 0 and 3 h after incubation. The experiment was designated with three repeated zones named slcomt1-1, slcomt1-2, and slcomt1-3. Each group consisted of 12 plants, with three flowers taken from each plant. The data included three biological replicates, and each biological replicate had three technical replicates.

DAPI staining for pollen microspore development

-

Buds at the uninucleate and binucleate stages were selected. On glass slides, 20 μL of DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining solution (0.1 M Na3PO4 (pH 7.0), 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.4 mg DAPI (Yuanye Shanghai, S19119)) was added. Using forceps, the anthers were gently crushed to evenly disperse the pollen grains in the staining solution. The slides were then placed in a humid chamber at room temperature, protected from light, for 1 h. Afterward, coverslips were added, and the samples were observed and photographed using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Ti-S).

Seed germination potential determination

-

After germinating seeds of both WT and slcomt1 plants, they were placed in culture dishes and subjected to a germination experiment at 28 °C in an incubator. On the fifth day, observations and photographs were taken, with three replicates for each group, comprising 100 seeds per replicate. Germination rates were subsequently calculated.

Determination of endogenous melatonin content

-

For each tissue sample of tomato, 0.3 g was weighed and mixed with 3 mL of phosphate buffer. The mixture was ground into a homogenate on ice and then centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min to collect the supernatant. The concentration of endogenous melatonin was determined in accordance with the instructions of the Plant MTELISA kit (Yuanju, Shanghai, China) using a multi-function microplate reader to measure the absorbance at 450 nm wavelength in the supernatant. The melatonin content in different tissue parts was calculated. Each tissue part had three biological replicates, and each biological replicate had three technical replicates.

RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and fluorescent quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR)

-

Total RNA from tomato anthers was extracted using the DP432 kit (Tiangen, Shanghai, China) following the kit's instructions. The purity and concentration of RNA were assessed through gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry using the B-500 microplate reader (Yuanxi, Shanghai, China). Two microliters of total RNA were reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the KR118 cDNA synthesis kit (Tiangen, Shanghai, China), and the resulting cDNA was stored at −20 °C. Fluorescence quantitative PCR was performed on the FQD1-96A instrument (BIOER, Hangzhou, China) using SYBR-Green dye. The reaction mixture (20 μL) included 2 μL of cDNA template, 10 μL of 2X SYBR-Green MIX, 6.8 μL of RNase-Free ddH2O, 0.6 μL of the forward primer, and 0.6 μL of the reverse primer. The PCR program consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 15 s, with fluorescence signal collection. The melting curve analysis involved a step from 60 °C, held for 30 s, and then raised to 95 °C, increasing by 0.5 °C every 30 s. Each treatment included three biological replicates, and each biological replicate had three technical replicates. The primer sequences used for fluorescence quantitative PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S3. Gene relative quantification was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method[43].

Data analysis

-

The experiment was conducted using a completely randomized design, with random sampling within each group. The experiment was designated with three repeated zones named slcomt1-1, slcomt1-2 and slcomt1-3. Each group consisted of 12 plants. Numerical data were processed using Microsoft Excel 2019. Statistical significance of the results was assessed using SPSS Statistics 23.0, and Duncan's multiple comparison test was employed. Different lowercase letters in the figures indicate significant differences at the (p < 0.05) level. Graphs were created using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 software, and the data in the figures are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

-

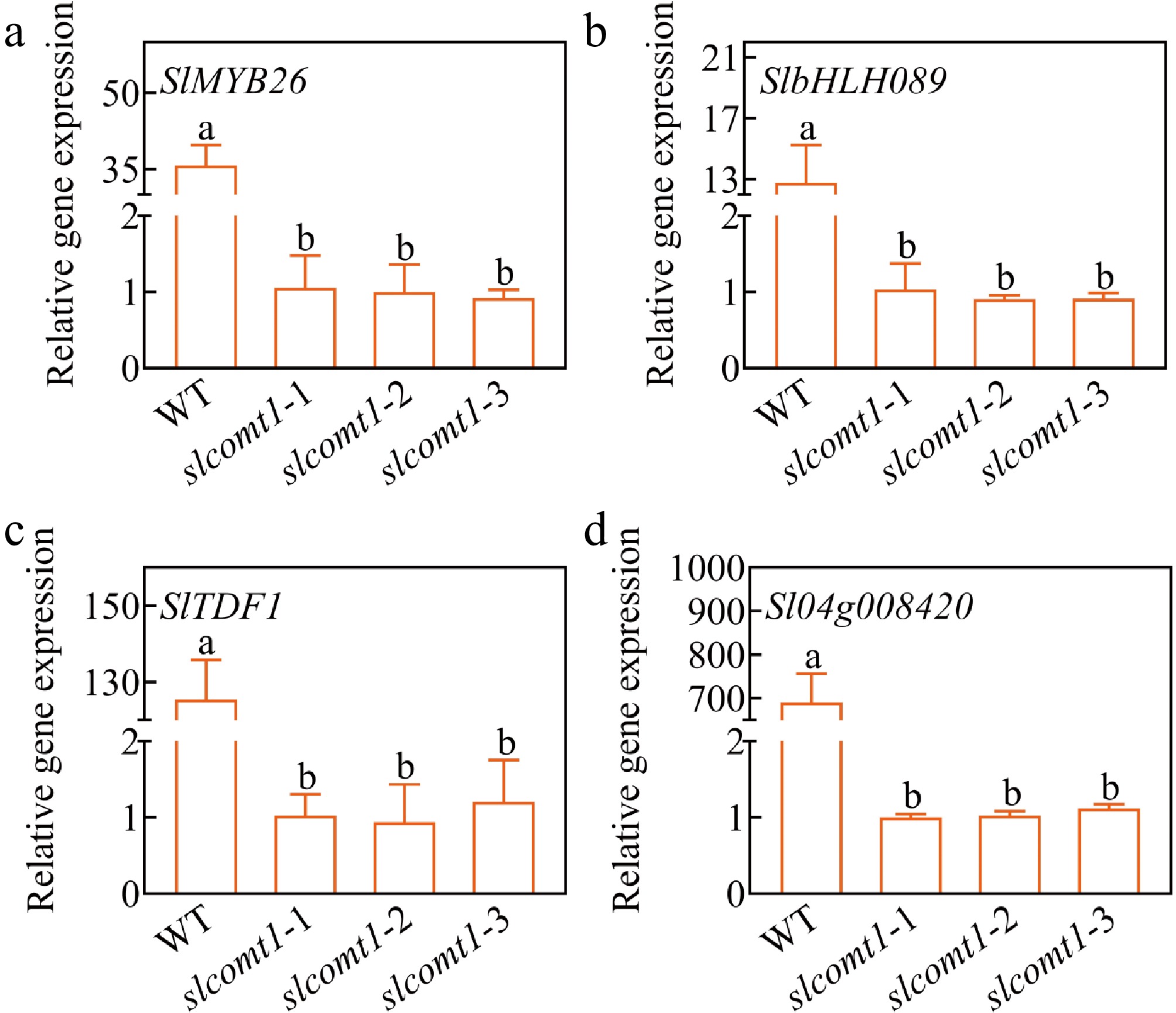

To comprehend the influence of endogenous melatonin on tomato flower development and investigate the function of SlCOMT1, the SlCOMT1 gene was knocked out, thereby suppressing melatonin biosynthesis. qRT-PCR was used to analyze the expression of the SlCOMT1 gene in various tissues of WT plants' flowers during the mature stage. The results are shown in Fig. 1a, SlCOMT1 exhibited expression in various tomato flower tissues, with pronounced expression in the stamens. This expression pattern was mirrored in the endogenous melatonin levels. In comparison to WT tomato plants, the endogenous melatonin content in floral tissues of slcomt1 plants significantly decreased by 66.6%, 42.3%, 52.6%, and 74.5% in the pistils, stamens, petals, and sepals, respectively (Fig. 1b). Subsequently, the floral phenotype was examined using a stereo microscope and observed that WT tomato plants exhibited more vibrant flower color, larger size, longer sepals, petals, and ovaries, and larger anthers densely covered with pollen, in contrast to slcomt1 plants (Fig. 1c). These results collectively indicate that the absence of the SlCOMT1 gene substantially diminishes endogenous melatonin biosynthesis and likely impacts tomato flower development.

Figure 1.

SlCOMT1 gene deletion reduces melatonin accumulation and disrupts floral development in tomato. (a) Relative expression levels of the SlCOMT1 gene in various floral tissues. Pi: pistil, St: stamen, Pe: petal, Se: sepal. WT: wild-type. slcomt1:SlCOMT1 gene deletion plants. (b) Endogenous melatonin content. (c) Floral tissue anatomical observations. Wft: Whole flower top view, Ss: Side sectional view. Plotted values are mean ± standard deviation (n = three biological replicates), separated using Duncan's multiple range test (p < 0.05); means with different lower-case letters represent significant differences.

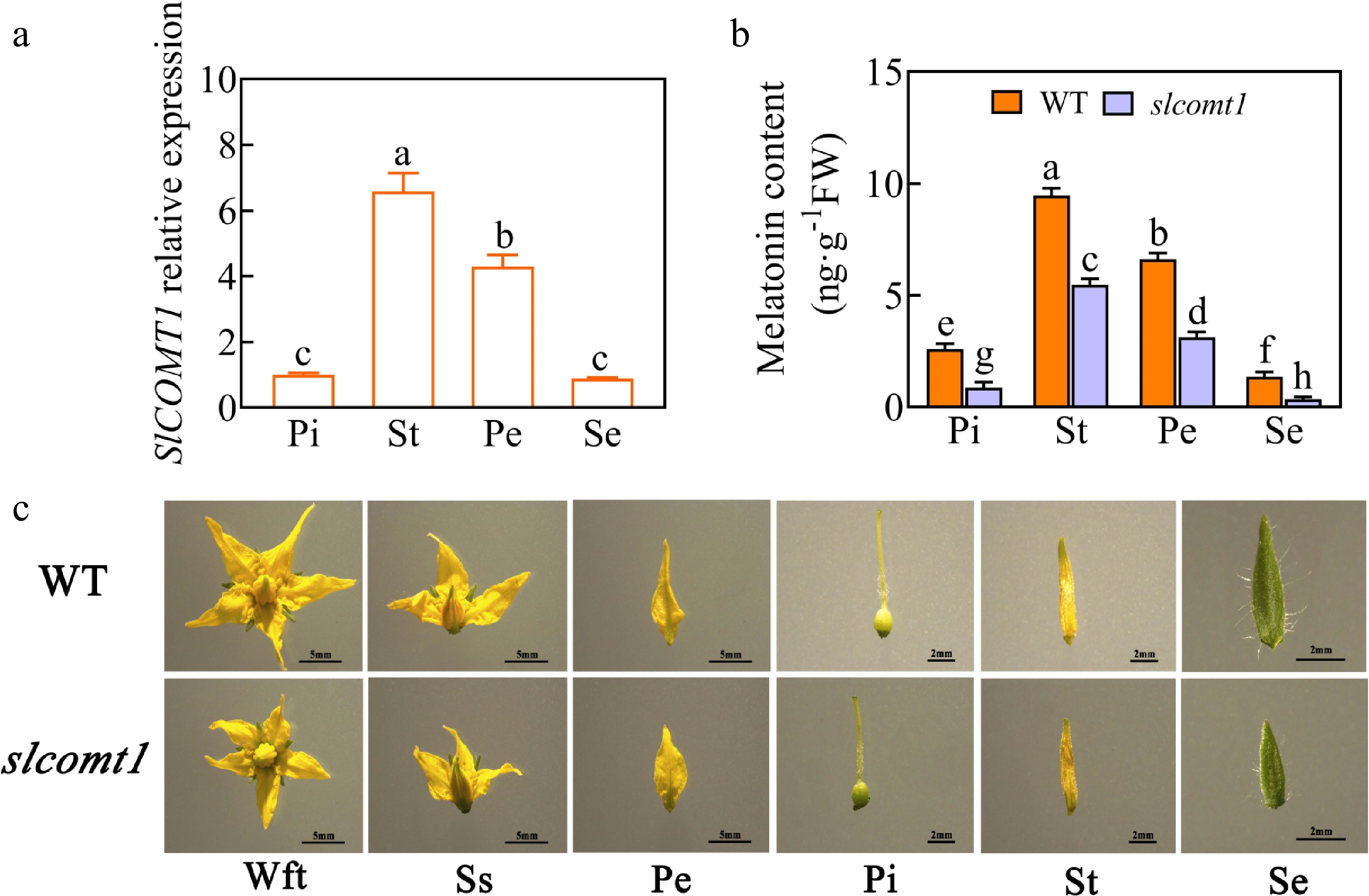

Impact of SlCOMT1 gene deletion on pollen external morphology

-

Examination of mature pollen grains through SEM revealed distinctive characteristics. In WT plants, normal pollen grains displayed an elliptical shape with full morphology, clear and evenly distributed germination furrows, and a normal rate of 93%. Conversely, mature pollen grains from slcomt1 plants exhibited irregular and abnormal shapes with sunken and wrinkled surfaces, presenting an atypical elliptical shape and germination furrows (Fig. 2a). The normal morphology rate of mature pollen grains in slcomt1-1, slcomt1-2, and slcomt1-3 plants decreased by 44%, 35.8%, and 38.1%, respectively, compared to WT plants (Fig. 2b). These observations indicate that the deletion of the SlCOMT1 gene impacts the external morphology of tomato pollen.

Figure 2.

SlCOMT1 gene deletion disrupts pollen morphology. (a) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) reveals aberrant pollen morphology in SlCOMT1 gene deletion. Mature pollen grains from WT and three independent slcomt1 lines (#1−#3). (b) Quantitative impairment of pollen structural integrity. Plotted values are mean ± standard deviation (normal morphology rate calculated from ≥ 200 grains per genotype across, n = three biological replicates), separated using Duncan's multiple range test (p < 0.05); means with different lower-case letters represent significant differences.

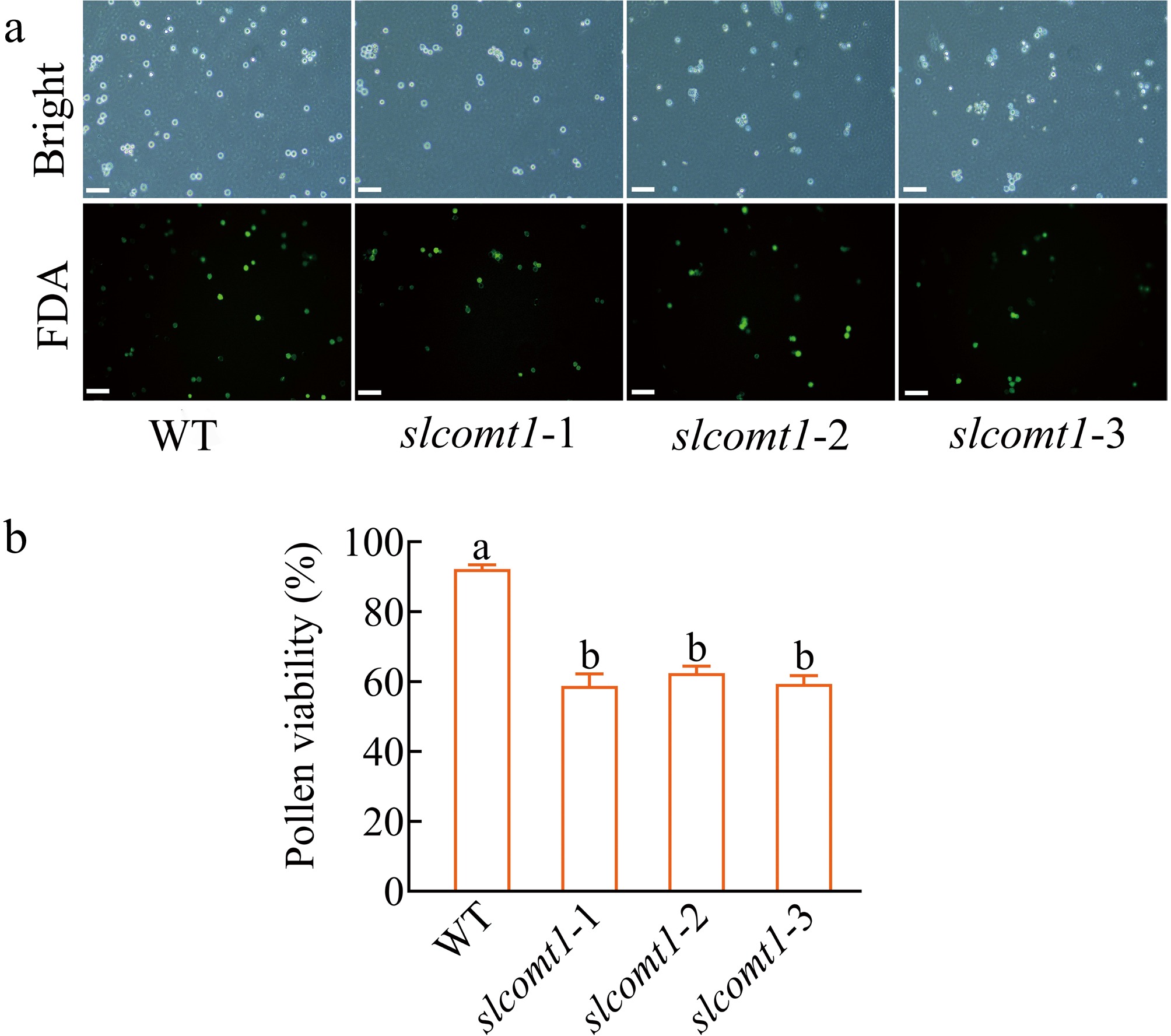

Impact of SlCOMT1 gene deletion on tomato pollen viability

-

To investigate whether SlCOMT1 is involved in the regulation of tomato reproductive development, the pollen viability of materials was compared with slcomt1 plants and WT plants (Fig. 3). FDA staining was used to assess pollen viability, revealing that approximately 92.2% of pollen from WT plants displayed vitality, as indicated by the emission of green fluorescence. In contrast, pollen from slcomt1 plants exhibited weaker green fluorescence, with pollen viability in slcomt1-1, slcomt1-2, and slcomt1-3 plants at 58.8%, 62.4%, and 59.3%, respectively. These values represent a significant reduction of 36.3%, 32.3%, and 35.6% compared to WT plants (Fig. 3b), indicating a substantial decrease in pollen viability in slcomt1 plants. These results suggest that pollen viability in tomato may be regulated by the SlCOMT1 gene.

Figure 3.

SlCOMT1 gene deletion impairs pollen viability. (a) Fluorescein diacetate (FDA) staining reveals reduced metabolic activity in mutant pollen. Pollen from WT and three independent slcomt1 lines (#1−#3) at anthesis. Viable pollen with intact esterase activity fluoresce green. (b) Quantitative loss of pollen viability correlates with fruit set failure. Viability calculated as (fluorescent grains/total grains) × 100%. Bar = 100 μm. Plotted values are mean ± standard deviation (≥ 200 grains scored per genotype across, n = three biological replicates), separated using Duncan's multiple range test (p < 0.05); means with different lower-case letters represent significant differences.

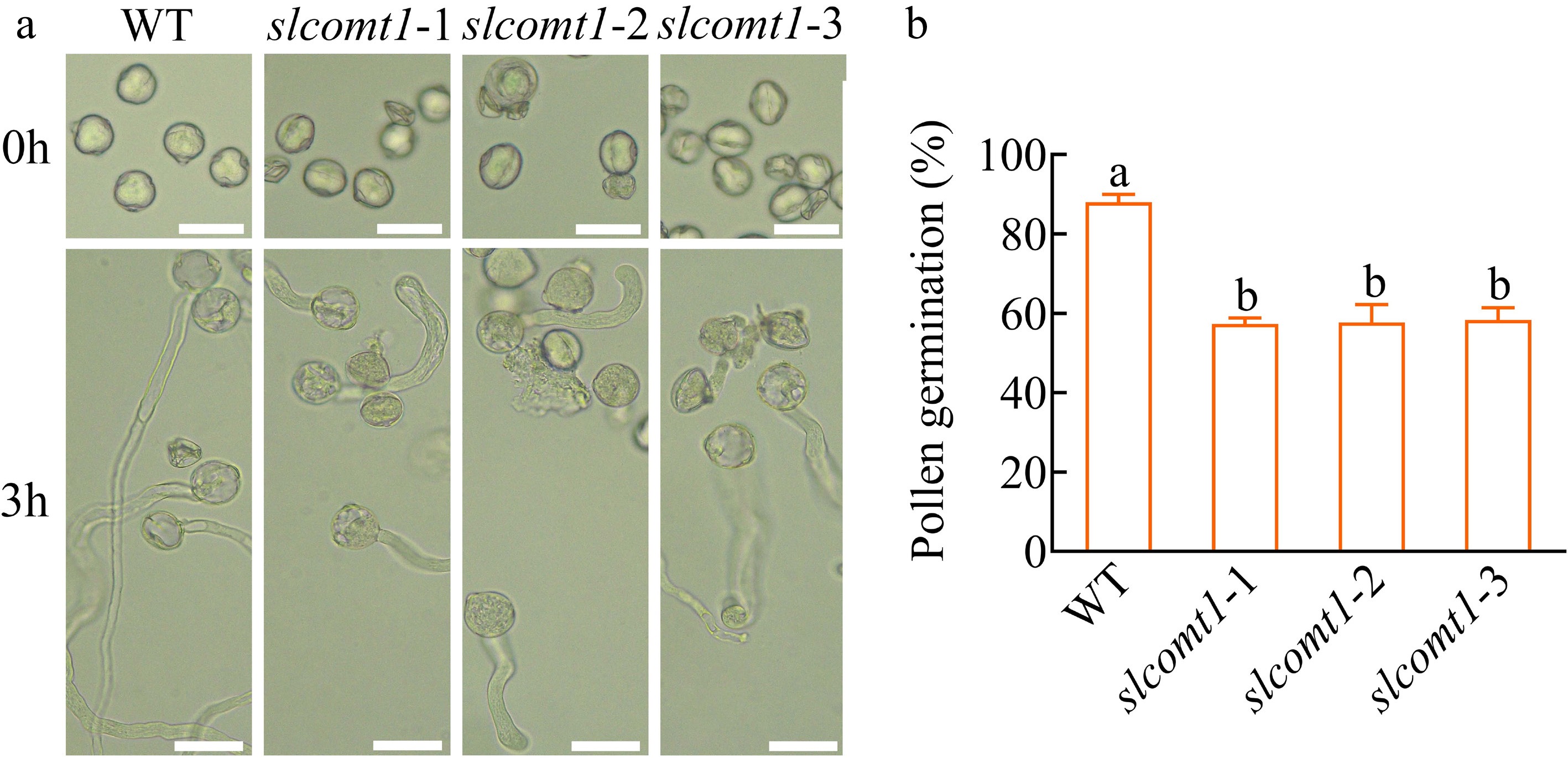

Impact of SlCOMT1 gene deletion on tomato pollen in vitro germination

-

Pollen germination is another critical indicator of pollen activity, and thus, an in vitro germination experiment was conducted on pollen from both WT and slcomt1 plants. The results of the pollen germination test were consistent with those of the pollen viability test. After 3 h of cultivation in the medium, the pollen germination rate of WT plants reached 88%, significantly outpacing that of slcomt1 plants. The pollen from slcomt1-1, slcomt1-2, and slcomt1-3 plants exhibited germination rates of only 57.3%, 57.6%, and 58.3%, respectively (Fig. 4). These findings underscore the pivotal role of the SlCOMT1 gene in the vitality and germination capability of tomato pollen.

Figure 4.

SlCOMT1 gene deletion suppresses in vitro pollen germination. (a) SlCOMT1 gene deletion impairs pollen tube emergence in vitro. Pollen from WT and three independent slcomt1 lines (#1−#3) germinated for 3 h on solid medium. (b) Quantitative defect in pollen germination efficiency. Bar = 50 μm. Plotted values are mean ± standard deviation (≥ 200 grains scored per genotype across, n = three biological replicates), separated using Duncan's multiple range test (p < 0.05); means with different lower-case letters represent significant differences.

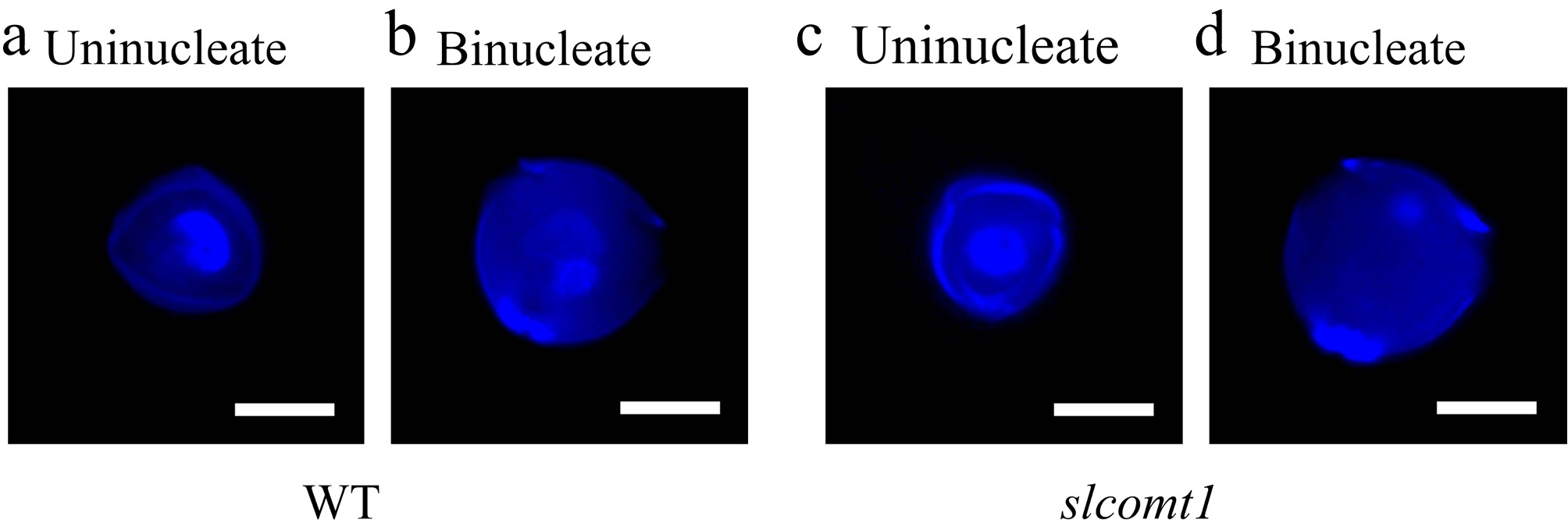

Impact of SlCOMT1 gene deletion on microspore nucleus development in tomato plants

-

DAPI staining was used to examine the nuclear development of microspores in both WT and slcomt1 plants during the uninucleate and binucleate stages. The results revealed that during the uninucleate stage, the nuclear development of microspores in both slcomt1 and WT plants appeared normal. However, at the binucleate stage, pollen grains of WT plants contained a normal vegetative nucleus and a generative nucleus. In contrast, many pollen cells at the binucleate stage in slcomt1 plants exhibited abnormality, either with incomplete binucleate pollen development or possessed only a single nucleus (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

SlCOMT1 gene deletion disrupts nuclear division during microspore transition from uninucleate to binucleate stage. (a), (b) Normal nuclear progression in WT microspores. DAPI staining of WT microspores. (c), (d) Aberrant nuclear behavior in slcomt1 mutants. Bar = 10 μm.

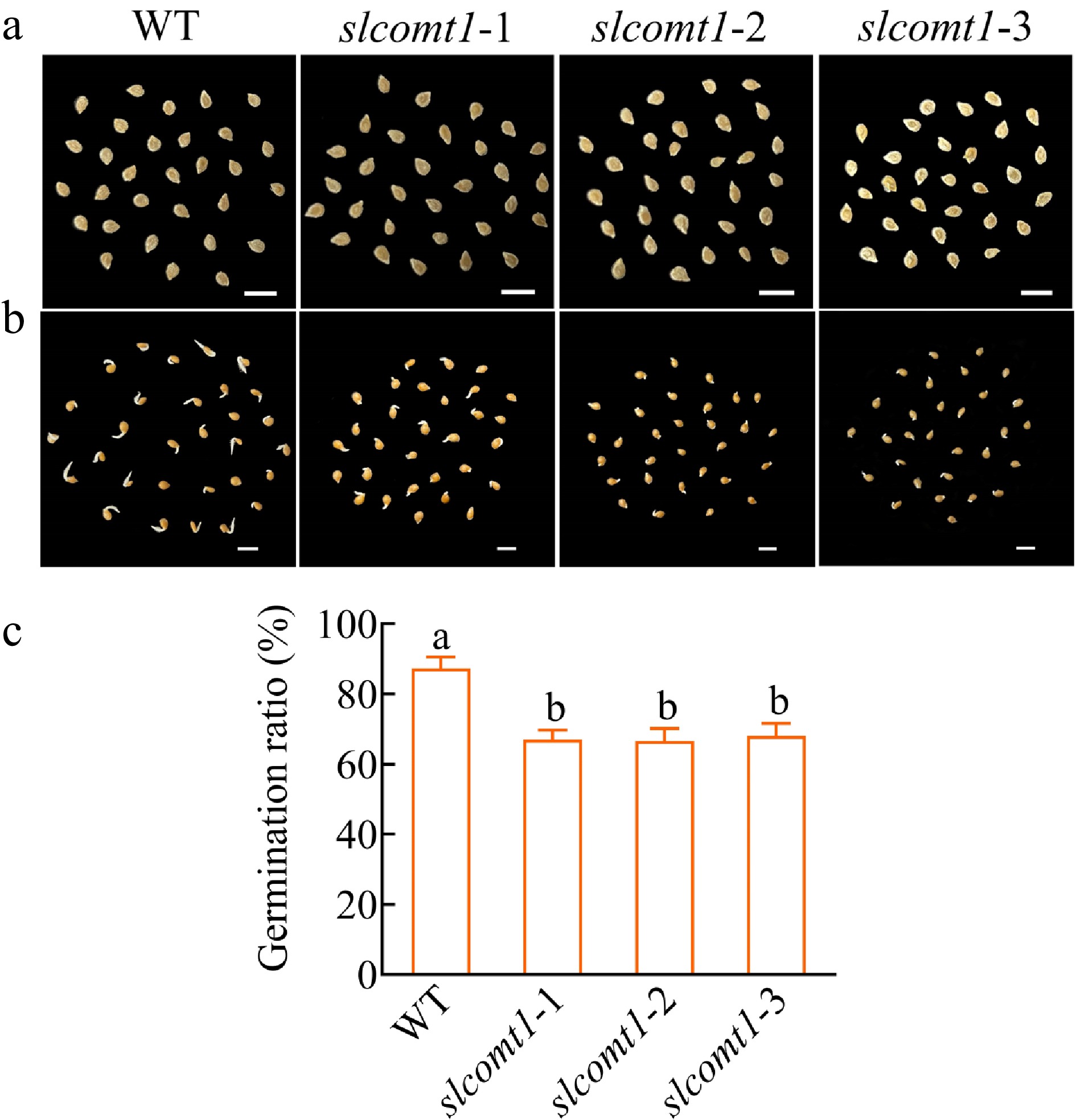

Impact of SlCOMT1 gene deletion on tomato seed germination

-

To preliminarily investigate the influence of SlCOMT1 on tomato seeds, seeds of the germination status and germination rate were examined on the fifth day. While there were no discernible differences in seed appearance (Fig. 6a), on the fifth day of germination, it became evident that the germination potential of seeds from WT plants was better than that of slcomt1 plants, WT plant seeds exhibited higher germination rates and longer embryonic roots compared to slcomt1 plant seeds (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, the seed germination rates of plants slcomt1-1, slcomt1-2, and slcomt1-3 were 67%, 66.7%, and 68%, which were significantly lower than those of WT plants (Fig. 6c). These results suggest that SlCOMT1 may play a role in regulating seed germination, potentially impacting the germination process.

Figure 6.

SlCOMT1 gene deletion impairs seed germination. (a) Phenotype of seeds from WT and three independent slcomt1 lines (#1−#3). (b) Delayed radicle emergence in SlCOMT1 gene deletion during germination. Seeds stratified and germinated on filter paper. Day 5 phenotypes. (c) SlCOMT1 gene deletion reduces seed germination rate. Bar = 5 mm. Plotted values are mean ± standard deviation (n = three biological replicates), separated using Duncan's multiple range test (p < 0.05); means with different lower-case letters represent significant differences.

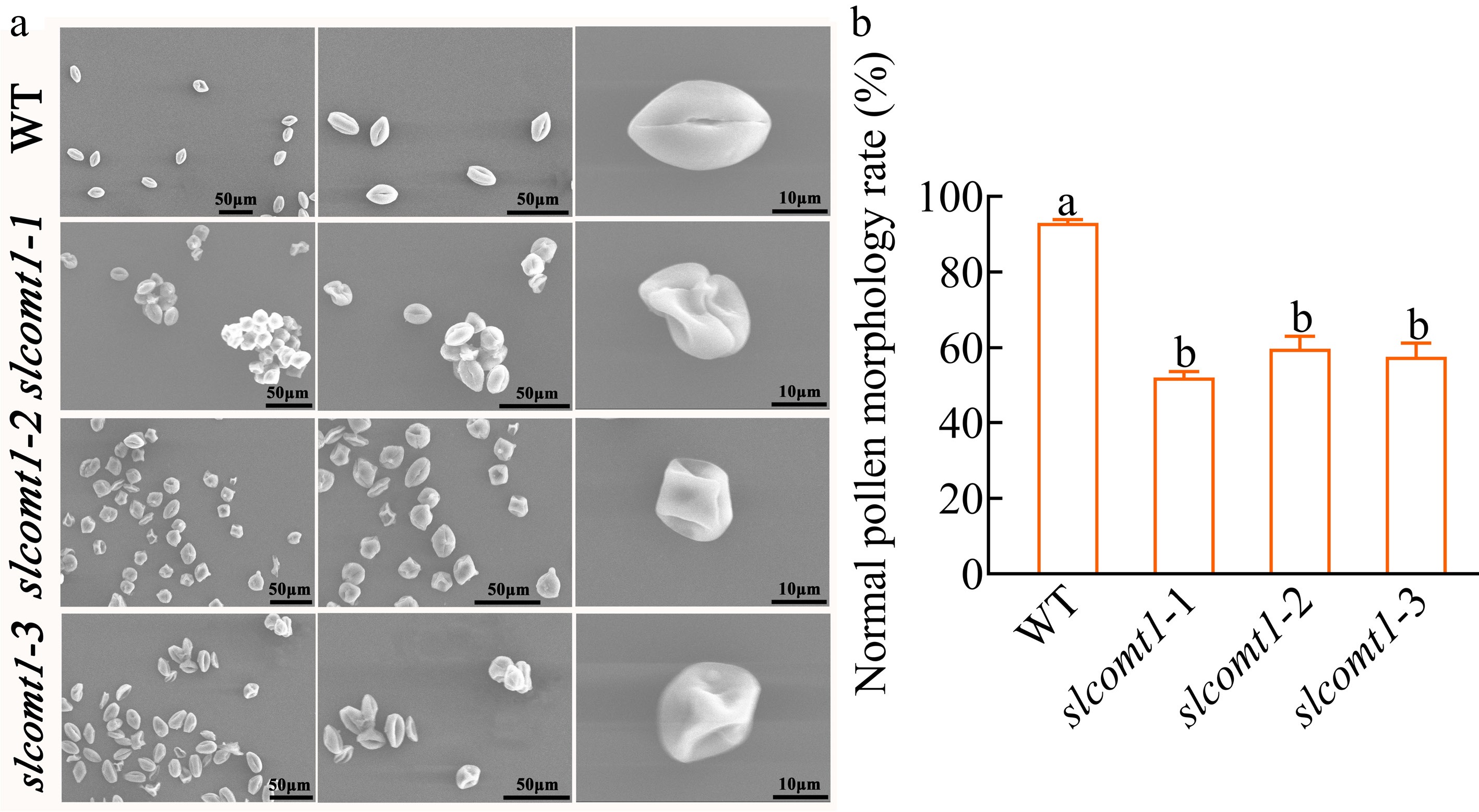

Expression analysis of pollen development-related genes

-

To investigate whether the regulatory role of SlCOMT1 in the degradation of the tapetum layer operates through transcriptional control of specific genes in the tapetum layer or the anther, Actin (Solyc04g011500) was used as an internal reference gene, and the transcription levels of three Arabidopsis homologous genes examined in mature tomato flowers, they are respectively: SlMYB26 (Solyc03g121740); SlTDF1 (Solyc03g113530); SlbHLH089 (Solyc08g062780), transcription levels of one rice homologous genes in mature tomato flowers, PTC1 like, Slyc04g008420. The results revealed that the expression of these genes was significantly suppressed to varying degrees in slcomt1 plants (Fig. 7).

-

Caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT) is a crucial enzyme involved in melatonin synthesis, impacting the melatonin content within tomato plants[44]. The present experiments have demonstrated that the SlCOMT1 gene is expressed in tomato flower tissues, with maximal abundance observed in the stamens. Additionally, the silencing of the SlCOMT1 single gene significantly reduces endogenous melatonin levels (Fig. 1). These results are consistent with those of Ahmmed et al., who found that silencing the single SlCOMT1 gene led to a substantial reduction in endogenous melatonin content[45].

The process of pollen development encompasses both meiosis (from microsporocyte to tetrad), mitosis (from unicellular pollen to bicellular pollen), and diverse morphological changes such as timely formation and degradation of the tapetum, pollen wall construction, formation and fusion of vesicles, and the establishment of germination furrows. The present study reveals that SlCOMT1 influences the vitality, in vitro germination, and external morphology of tomato pollen. The pollen from slcomt1 plants exhibited significantly lower vitality and in vitro germination rates compared to WT plants (Figs 3 and 4). Many pollen grains from slcomt1 plants displayed irregular and uneven surfaces with abnormal germination furrows (Fig. 2). Some microspores in slcomt1 plants were unable to produce normal bicellular pollen grains during mitosis (Fig. 5). Given melatonin's dual roles in development and stress tolerance[46], the observed pollen defects in slcomt1 may be exacerbated under environmental challenges. In addition, anther development and pollen fertility are also regulated by other genes. For example, previous studies[47] have found that SlPIF4 in tomato can negatively regulate the cold tolerance of anthers by directly acting on the tapetum regulatory module. Under low temperature conditions, it promotes the abnormal activation of the SlDYT1–SlTDF1 pathway, which in turn leads to tapetum dysfunction and pollen abortion. However, knockout of SlPIF4 can block this process and improve the cold tolerance of pollen. This indicates that different genes may play roles through different mechanisms in tomato anther development and function maintenance, further highlighting the necessity of in-depth exploration of related gene regulatory networks. While this study focuses on baseline conditions, future work should assess SlCOMT1's role in stress-resilient pollen development.

Seed germination is a crucial phase in the reproductive cycle of higher plants. It initiates with the emergence of the radicle through the seed coat, marking the beginning of seed germination. Throughout the process of seed germination, it is subject to regulation by an array of enzymes, cell wall proteins, and genes. Previous studies have also indicated that melatonin, as a plant growth regulator, can promote seed germination. Low concentrations of melatonin are conducive to germination, whereas high concentrations may not stimulate germination and might even inhibit it[48−50]. In the present study, the single-gene knockout of SlCOMT1 resulted in a reduced germination potential of tomato seeds on the fifth day (Fig. 6). Seed germination involves the intricate participation of numerous genes, and the precise interactions between SlCOMT1 and its interacting proteins affecting seed germination and overall germination rate and emergence of tomato seeds in the later stage remain to be elucidated, warranting further investigation for all of them.

Tomato pollen development shares similarities with that of Arabidopsis and rice[51,52]. SlMYB26, Sl03g059200, and SlbHLH089 are homologous to key genes in the Arabidopsis pollen wall regulatory network, including AtMYB26, TDF1, and AMS. Moreover, Sl04g008420 corresponds to PTC1, a transcription factor responsible for regulating pollen wall development in rice[53]. These transcription factors affect tapetum development and, therefore, microspore development. In the present study, the expression of these genes was downregulated in slcomt1 plants (Fig. 7).

Therefore, it is inferred that SlCOMT1 positively regulates a conserved core transcription factor network (including homologous genes such as SlMYB26 and SlbHLH089) by maintaining sufficient endogenous melatonin levels. This network is responsible for coordinating tapetum development and degradation, the precise construction of the pollen wall, and the mitotic progression of microspores. Consequently, melatonin deficiency caused by the loss of SlCOMT1 disrupts this transcriptional network, leading to abnormal tapetum function, pollen wall defects, and arrested microspore development. This ultimately manifests as deformed pollen, loss of viability, and failure to germinate. Pollen development is an intricate process[54], and the specific mechanistic details require further investigation. The integration of antioxidant defense and developmental signaling positions SlCOMT1 as a key node ensuring pollen fitness under fluctuating environments—a trait critical for crop breeding.

-

This study reveals that SlCOMT1 is highly expressed in tomato stamens. Knocking out the key melatonin biosynthesis gene SlCOMT1 results in reduced endogenous melatonin levels. Pollen grains exhibit partial deformities and adhesions, along with significantly decreased viability and germination rates. Additionally, incomplete binucleate pollen development (or retention of a single nucleus) is observed. Furthermore, seed germination potential on the fifth day is markedly lower than in WT plants, and the expression of pollen development-related genes is suppressed.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31760594, 32260754), Guizhou Provincial Basic Research Program (Natural Science) (No. Qiankehe Foundation ZK [2025] Surface 651), and the Platform construction project of Engineering Research Center for Protected Vegetable Crops in Higher Learning Institutions of Guizhou Province (Qian Jiao Ji [2022] No. 040).

-

The authors confirms their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xu W, He Z; data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, methodology, draft manuscript preparation: He Z; project administration, supervision, funding acquisition, writing − review and editing: Xu W; software: Song L, Wen C, Cheng Q; validation: Xu W, Song L, Wen C, Cheng Q. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 sgRNA target sequence primers.

- Supplementary Table S2 Positive plant material identification primers.

- Supplementary Table S3 qPCR sequences of tomato pollen development related genes and SlCOMT1.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

He Z, Song L, Wen C, Cheng Q, Xu W. 2025. Endogenous melatonin gene SlCOMT1 involved in pollen development in tomato. Vegetable Research 5: e041 doi: 10.48130/vegres-0025-0035

Endogenous melatonin gene SlCOMT1 involved in pollen development in tomato

- Received: 09 June 2025

- Revised: 14 July 2025

- Accepted: 13 August 2025

- Published online: 03 November 2025

Abstract: Anther development in plants involves the precise regulation of numerous genes. This study delves into the role of endogenous melatonin in tomato anther development, utilizing tomato plants with a knockout of the key melatonin biosynthesis gene SlCOMT1 (slcomt1). The research revealed that SlCOMT1 is highly expressed in the anthers, and slcomt1 plants exhibited significantly reduced pollen viability and germination compared to WT plants, with reductions of approximately 34.7% and 34.3%, respectively. Notably, pollen from slcomt1 plants displayed anomalies, including partial deformities and adhesion. In addition, the germination status of slcomt1 seeds on the fifth day was lower compared to that of WT plants, and the expression of pollen development-related genes in slcomt1 plants was significantly inhibited to varying degrees. This study underscores the pivotal role of endogenous melatonin in tomato anther development, paving the way for deeper investigations into the biological function of SlCOMT1. These findings hold great promise for shedding light on further research and applications of melatonin in the agricultural field.

-

Key words:

- Tomato /

- Melatonin /

- SlCOMT1 /

- Pollen development /

- Pollen viability