-

Plant male sterility mainly consists of cytoplasmic male sterility and cytosolic male sterility. Ogura-type male sterile lines are of the cytoplasmic male sterile type and are regulated by cytosol-plasmid gene interactions, and the pollen exhibits complete abortion. Various cytoplasmic male sterility types have been characterized in food crops, such as maize[1], rice[2], wheat[3], and soybean[4], and in cruciferous vegetable crops, such as radish[5], rape[6], and cabbage[7,8]. Due to the wide range of cytoplasmic male sterility types and the fact that it is a maternally inherited trait encoded by mitochondrial genes[9], this type of sterility is easier to maintain, simplifying the hybridization process; thus, it is widely used.

Chinese cabbage is the most representative cruciferous vegetable native to China and is a hybrid of turnip (B. rapa ssp. rapifera) in North China, and bok choy (B. rapa ssp. chinensis) in South China[10]. It has a history dating back 1,500 years and is widely planted in Asia[10,11]. It is rich in nutrients such as vitamin C and dietary fiber[12,13]. Some progress has been made in the identification of nuclear genes related to Ogura CMS cabbage based on the male sterility system using crop hybridization (heterosis); thus, the disease resistance, adaptability, growth, quality, and parent quality are noticeably better than parents[14,15], improving crop yield and quality[16] and land use efficiency, which can reduce global food pressure. Therefore, research on male sterility in Chinese cabbage cytoplasm has a very important application value in Chinese cabbage breeding.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are regulatory molecules unique to eukaryotes, with highly complementary sequences and lengths ranging from 18 to 25 nucleotides. They are usually recognized by complementary pairing with target mRNA bases, thus affecting the normal translation or expression of target mRNAs[17,18]. Some studies have identified miRNAs that affect pollen development through post-transcriptional regulation[19−21]. miRNAs are involved in plant growth and development, and are important factors regulating plant flowering[22,23], through the regulation of downy mildew development affecting anther development, and through the regulation of microspore development affecting pollen fertility[24]. The study of miRNAs on the Ogura CMS is still in its infancy, and it is still necessary to explore relevant information more deeply. In a previous study on the expression function of organ-specific miRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana, a series of specific miRNAs were identified as highly expressed in flowers, including miR860[25]. Some related studies have also shown that miR860 is specifically and highly expressed in the anthers of Chinese cabbage maintainer lines[26]. Previous studies have shown that nuclear CCS1[27] can be used for cytochrome maturation, and its mutation is associated with the cytochrome content, and energy production[28,29]. However, the identification of miRNA and its target genes has been limited in Chinese cabbage; thus, in response to the development of pollen in the Ogura sterile line of Chinese cabbage, miR860 has far-reaching significance.

The CCS1 gene is a novel component of the biosynthesis of coding system II cytochrome c, an essential component of respiration and photosynthetic electron transport, that is critical for plant pollen development. Its C-terminus has a soluble inner lumen structural domain that is essential for the covalent binding of heme in a transient manner by three closely spaced transmembrane structural domains at the N-terminus of the protein bound in the vesicle-like membrane[30]. CCS1 mutations have been associated with increased cytochrome content, respiration, and ATP synthesis, and nuclear CCS1 mutations have been identified through resistance to mitochondrial ATPase inhibitors. Their mutants exhibit increased levels of cytochromes b and c, as well as enhanced respiration and ATP synthesis rates[29,30]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, cytochrome c genes Cytc-1 and Cytc-2 are both specifically expressed, and the TCP structural domain protein-binding element is involved in the specific expression of the Cytc-1 gene in the anthers and meristematic tissues of Arabidopsis thaliana, affecting ATP synthesis and thus the pollen development process[31]. During plant growth and development, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced by different cellular compartments via aerobic metabolic pathways and play a key role in all aspects of plant flowering and reproduction. The reactive oxygen species (ROS) are associated with programmed cell death (PCD) in the chorioallantoic membrane layer[32,33], and the cytotoxicity of Cytc mitochondrial damage and translocation may be reasons for the triggering of PCD, and ROS accumulation contributes to the early onset of PCD under conditions of oxidative stress in plants, regulating pollen development[34]. In studies on the sterility mechanism of rice, delayed cell death in the tapetum layer has been associated with low ROS levels, which decrease cell wall formation, resulting in sterility[35].

The sterility gene of Ogura CMS has been shown to be orf138[36], which is co-transcribed with the encoded mitochondrial gene atp8 to produce proteins that accumulate in the mitochondrial membrane, and create unfavorable conditions for pollen development, thus leading to pollen failure[37,38]. Related studies have identified several mRNAs and miRNAs involved in the regulation of plant male sterility, and miRNAs are closely related to key growth processes, such as plant pollen development. However, there are relatively few studies on gene regulation of Chinese cabbage Ogura CMS fertility, especially miRNAs affecting pollen development, which have rarely been reported. In this study, miRNA, transcriptome, and degradome sequencing were performed in cabbage Ogura CMS and maintainer lines during different periods to identify miRNAs and target genes key for specific expression. miR860 overexpression and silencing vectors were constructed and transformed into Arabidopsis. These results provide a basis for further elucidation of the mechanism by which bra-miR860 affects the onset of male sterility in Chinese cabbage, and for the molecular mechanism of the sterility phenomenon in this species, thus laying a theoretical foundation for genetic seed production in Chinese cabbage.

-

The Ogura CMS sterile line (Tyms) and its maintainer line (Y231-330) of Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis) selected for this study were provided by the Institute of Vegetables, Henan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Zhengzhou, Henan Province, China), and planted in Henan Modern Agricultural Research and Development Base (Yuanyang, Henan Province, China)[26]. The evaluated groups were as follows: early pollen development in the maintainer line (ML1: S07, S08, S09), early pollen development in the Ogura CMS line (CMS1: S10, S11, S12), late pollen development in the maintainer line (ML2: S01, S02, S03), and late pollen development in the Ogura CMS line (CMS2: S04, S05, S06) (Supplementary Table S1).

RNA extraction and library construction

-

Total RNA of the anther samples was extracted using the Trizol method, and gel electrophoresis was used to detect degradation and impurities in the extracted RNA, and determine the purity and concentration of the RNA and the integrity of the proposed RNA. Total RNA samples that passed the test were separated into fragments using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and the small RNAs in the range of 18–30 nt were recovered using gel recovery. The small RNA libraries were obtained using reverse transcriptase, and the libraries that passed the quality test were used in high-throughput sequencing with the HiSeq X-ten platform (Biomark Biotechnology (Beijing, China) Co., Ltd). Raw reads were processed according to the base quality value[39] and nucleotide number to obtain high-quality sequences (clean reads). The clean reads were processed using Bowtie[40] software to obtain the unannotated reads (including miRNAs), and then aligned with the corresponding reference genomes. The screening criteria for differentially expressed microRNAs are as follows: miRNAs with a fold change (FC) ≥ 2, and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 were considered differentially expressed miRNAs (DEmiRNAs).

Construction of the cDNA library and data processing

-

Before library construction, it was determined whether the samples met the qualification requirements to complete the subsequent RNA extraction, sequencing, and data quality control. The Bioconductor software package EdgeR[41] was used to determine differential expression, and Poisson distribution and empirical Bayesian methods were used to reduce the dispersion coefficient among transcripts to improve the reliability of the results. The screening criteria for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) are consistent with those for DEmiRNAs.

Construction of the degradome library and statistics of sequencing results

-

Total RNA was extracted in Chinese cabbage Ogura CMS and maintainer lines during different pollen development periods, and mixed into one sample, in equal amounts, to construct a degradome library. The clustering data were compared with the Rfam database[42] to obtain relevant annotation information, and the unannotated sequences were subjected to degradation site analysis.

STTM-miR860 and OE-miR860 vector construction

-

STTM-miR860[43] and OE-miR860 vectors were constructed by homologous recombination and golden gate seamless cloning. The target fragments did not contain any cleavage site at either end, and the recombinant plasmids of STTM-miR860 and OE-miR860 were digested using EcoRV endonuclease.

qRT-PCR validation of miRNA and mRNA sequencing data

-

The target miRNAs and mRNA were subjected to real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) by adding poly-A at the 3' end to verify the reliability of the miRNA sequencing data. miRNA reverse transcription was performed using the Takara Mir-XmiRNA First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Takara BioTechnology (Dalian, China) Co., Ltd), and TB GreenTM qRT-PCR User Manual Reverse Transcription Kit (Takara BioTechnology (Dalian, China) Co., Ltd). Based on the mRNA sequences, Primer 5.0 was used to design primers for mRNA fluorescence quantitative PCR. GAPDH was screened in our laboratory and used as the internal reference primer. Primer synthesis was performed by Sunya Biotechnology Company (Zhejiang, China). qRT-PCR-associated primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3.

OE-miR860 and STTM-miR860 Arabidopsis thaliana transformation

-

The genetic transformation material used in this study was Arabidopsis A. thaliana (Columbia, 2n), which was provided by the Vegetable Research Institute of Henan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Henan, China). Agrobacterium tumefaciens (GV3101) and Escherichia coli (DH5α) were purchased from the Weidi Biological Company (Shanghai, China); the interference and overexpression vectors were both the pBWA(V)KS-ccDB vector provided by the Biorun Biological Company (Wuhan, China).

In this study, Arabidopsis thaliana was sown and incubated in a light incubator under 16 h of light (22 °C) and 8 h of darkness (18 °C). A. thaliana was infested with Agrobacterium tumefaciens using the floral dip method to expand cultures, and activated by shaking at 28 °C. It was then transferred to a centrifuge tube, centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 10 min, and resuspended in an osmotic solution (containing 5% sucrose, 0.02% SilwetL-77, and 1/4 MS (Murashige and Skoog) nutrient solution with Acetosyringone) to form an Agrobacterium suspension (OD600 = 0.8). The siliques and open flowers of 6-week-old A. thaliana were removed, and the unopened flower buds were removed with forceps. The Arabidopsis seedlings were inverted, and the inflorescences were immersed in the prepared suspension for 20−30 s to fully infest the inflorescences. The infested inflorescences were covered with black plastic film and grown in a dark box for about 24 h. After 24 h, the treated Arabidopsis plants were placed in a light incubator (light 16 h/22 °C, dark 8 h/18 °C) for normal growth. One week later, the plants were again infested, and the infested inflorescences were harvested about 3 weeks later when the pods were ripe.

The DNA of the inflorescences of T1 generation transgenic A. thaliana was extracted and detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the appearance of bands indicated that the vector had been transfected into Arabidopsis thaliana, and the T2 generation transgenic A. thaliana was sown again and used for qRT-PCR experiments, and the seeds of the T2 generation of A. thaliana were obtained, the seed screening continued to be sown and the inflorescences of the T3 generation of transgenic A. thaliana were selected for the subsequent experiments. Plants with bands detected by electrophoresis were used to extract Arabidopsis RNA, and its quality was checked using an RNA Extraction Kit (Takara BioTechnology (Dalian, China) Co., Ltd). Positive seedlings were identified using reverse transcription and fluorescence quantification of the relevant miRNAs and their target genes.

Pollen viability

-

Plant pollen grain viability was determined using Alexander staining[44]. Viable pollen grains stained with Alexander's stain were a distinct purple-red color, while pollen that was not stained had abnormal coloring. Alexander staining used an appropriate amount of Alexander staining solution in a 200-µL EP tube. Mature anthers were removed with tweezers under the stereo microscope (Toup Optoelectronics Technology (Hangzhou, China) Co., Ltd), placed into the centrifuge tube containing Alexander staining solution, and stained for 1 h under light protection. The stained anthers were removed and rinsed with water. They were placed on slides (with an appropriate amount of water added to the surface), adjusted, and covered with coverslips. The anthers were observed and photographed.

Determination of the ATP content and ROS content

-

The ATP content of the anthers of transgenic A. thaliana was determined using a reagent kit (Griswold, Suzhou, China). To determine the active oxygen content, the floral organs, including petals, calyx, and stigma, of transgenic A. thaliana were removed using tweezers, and the anthers were placed in 1.5-mL EP tubes with freshly prepared MES-KCl buffer. The material was completely immersed, and the liquid in the centrifuge tubes was carefully removed with a syringe after continuous immersion for 30 min. H2DCFDA dye was added to the centrifuge tubes to a final concentration of 50 µM for 1 h. The dye was aspirated using a syringe. The samples were rinsed 2 or 3 times with MES-KCl buffer solution and soaked again in the same buffer for 15 min. The samples were removed, placed on slides, prepared (not pressed) with a drop of MES-KCl buffer, viewed, and photographed under the FITC channel of a confocal microscope (LSM880, Zeiss).

-

To investigate the regulation of miRNA on the fertility of Chinese cabbage Ogura CMS, small RNA sequencing libraries were constructed for the anthers of sterile and homozygous maintainer lines at different pollen developmental stages. Three biological replicates were set up for two lines at two different stages. After small RNA sequencing of 12 samples, 143.64 Mb clean reads were obtained, with no less than 10.04 Mb clean reads for each sample and base quality values Q30 ≥ 96.11% (Supplementary Table S4 & S5).

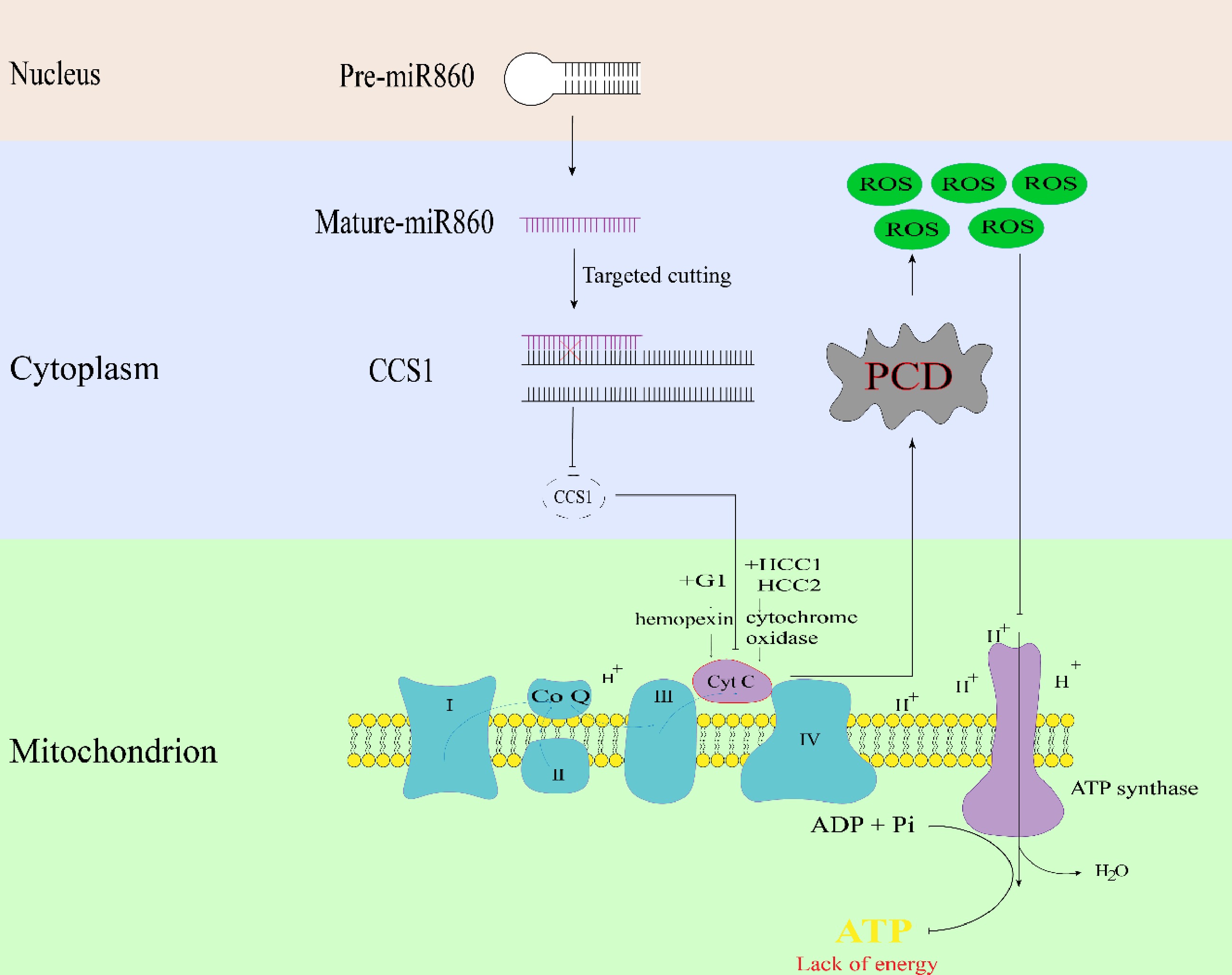

Using the miRBase database, reads from all sterile and homozygous maintainer lines were compared to the Chinese cabbage reference genome. The comparison range was expanded to two bases upstream and five bases downstream of the mature miRNA sequence, and up to one mismatch was allowed. At the early pollen development stage, the maintainer lines contained 87 known and 267 novel miRNAs, while the sterile lines contained 87 known and 265 novel miRNAs. At the late stage, the maintainer lines contained 75 known and 226 novel miRNAs, compared to 82 known and 250 novel miRNAs in the sterile lines (Supplementary Table S6). The lengths of known miRNAs and new miRNAs are shown in Fig. 1a; most miRNAs are of 21 pb. The number of differentially expressed miRNAs between samples was counted and presented in a bar graph (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

Sequencing results of miRNAs in different pollen development periods of Ogura-type cytoplasmic male sterile and maintainer lines of Chinese cabbage. CMS1 refers to the early stage of pollen development in sterile lines, CMS2 refers to late pollen development in sterile lines, ML1 refers to the early development of pollen in the retention line, ML2 refers to the late stage of pollen development in the maintenance line. (a) Length statistics of known miRNAs and new miRNAs. (b) Statistics on the number of differentially expressed miRNAs in Ogura-type cytoplasmic male sterile and maintainer lines of Chinese cabbage during different pollen developmental periods. (c) GO annotation of target mRNAs of differentially expressed miRNAs in two lines of Chinese cabbage during late pollen development (ML2 vs CMS2). (d) KEGG pathway enrichment of target mRNAs of differentially expressed miRNAs in two lines of Chinese cabbage during late pollen development (ML2 vs CMS2).

Cells in the tapetum layer of Chinese cabbage were abnormally enlarged and vacuolated from the tetrad stage, which can lead to pollen abortion[45]. One hundred and eighty three miRNAs were differentially expressed between sterile and maintained lines at the late pollen development stage, and GO enrichment analysis showed that the target mRNAs of these differentially expressed miRNAs were enriched in the following: biological processes, including 'multicellular processes', 'reproductive processes', and 'immune system'; in cellular components, including 'plasma membrane', 'membrane-enclosed lumen', and 'immune system'; and molecular functions, including 'electron carrier activity', 'signal transducer activity', and 'structural molecule activity' (Fig. 1c). To further investigate how target genes were involved in metabolism, the target mRNAs of the predicted differentially expressed miRNAs were compared using the KEGG database. The target genes were mainly enriched in the 'Ribosome', 'Amino acid biosynthesis', and 'Plant-pathogen interactions' pathways in both sterile and maintainer lines during the late stage of pollen development (Fig. 1d).

Transcriptome sequencing analysis of maintainer and sterile Chinese cabbage lines

-

Samples were selected in accordance with the miRNA sequencing samples, and the early pollen development samples were anthers with bud lengths ranging from 1.5 to 3.5 mm in sterile and maintainer lines. The late pollen development samples were anthers with bud lengths greater than 5 mm in both lines. Three replicates were set up for both early and late pollen development samples, and after controlling the quality of sequencing data, 138.12 Gb of clean data were obtained. The Q20 value of each sample was above 98%, and the Q30 value was greater than or equal to 95.64% (Supplementary Table S7). Therefore, the sequencing results were reliable. The mapped reads/clean reads were calculated to determine whether the reference genome satisfied the information analysis involved in this study. Sequencing data for the samples were compared with the corresponding reference genomes, and the results showed that the matching efficiency between the reads and reference genomes of each sample was greater than 70%, indicating that the quality of the sequencing read data was effective (Supplementary Table S8).

A total of 22,223 DEGs were identified in this study by setting the multiplicity of differences criterion to a value greater than or equal to 2, and the corresponding false discovery rate criterion to less than 0.05. The total number of DEGs was screened and identified in the two lines during different periods of pollen development. Based on two-dimensional principal component analysis (PCA), which was used to reflect the correlation and independence among the three samples of sterile and maintainer lines at different pollen development periods, the same color among biological replicates indicated duplicate samples (Supplementary Fig. S1). The components existed independently of each other, but the replicate samples were closely clustered, indicating high independence among the samples and a strong correlation among the three replicate values.

The number of DEGs identified between different lines in the same pollen development period, and between different pollen development periods in the same line was determined. A total of 8,052 DEGs were identified in the maintainer and sterile lines during the early stage of pollen development, of which 3,890 were upregulated, and 4,112 were downregulated. In total, 7,852 DEGs were identified in the maintainer and sterile lines during the late stage of pollen development, of which 2,559 were upregulated, and 5,293 were downregulated. There were 15,642 DEGs screened in the maintainer line during early and late pollen development, of which 7,243 and 8,399 genes were up- and down-regulated, respectively. A total of 14,764 differential genes were screened in the sterile line during early and late pollen development, of which 5,948 were upregulated, and 8,816 were downregulated (Supplementary Fig. S1). More DEGs were identified as downregulated than upregulated. The most DEGs were identified in the maintainer and sterile lines during late pollen development, indicating that several genes regulate pollen development, and that these DEGs may lead to pollen failure by affecting a series of physiological and biochemical responses.

Transcriptomic analysis of late-stage pollen development: DEG expression patterns and functional enrichment related to fertility

-

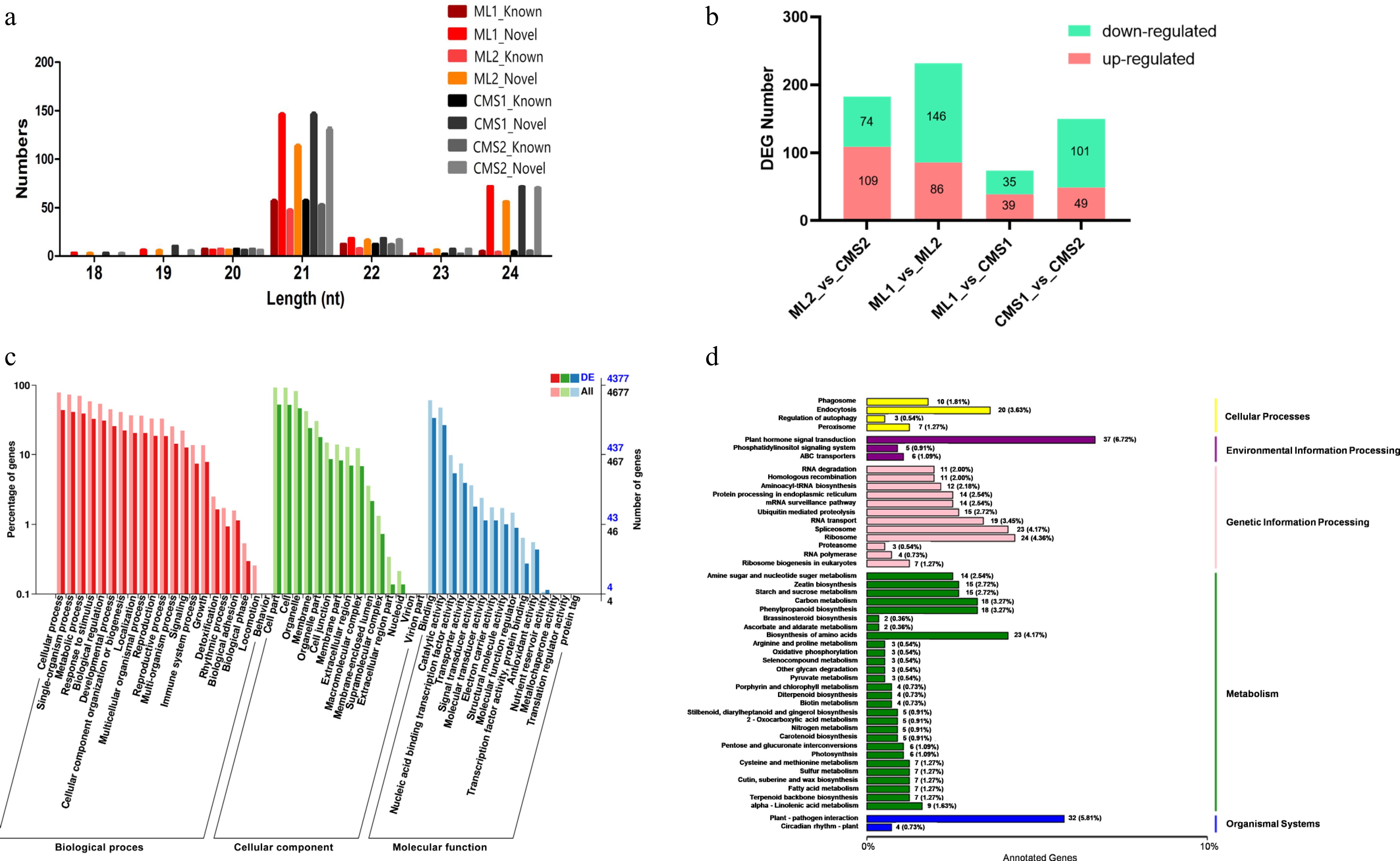

The DEGs that were upregulated in both maintainer and sterile lines during the late stage were visualized in Wayne plots (Fig. 2a). Among them, 3,434 DEGs were co-expressed, and 3,719 and 2,467 DEGs were specifically expressed in the maintainer and sterile lines, respectively. GO enrichment analysis of these DEGs was performed. Co-expressed DEGs were mainly enriched in 'outer wall', 'pollen wall', and 'protein binding' (Fig. 2b). The DEGs in the maintainer lines were mainly enriched in 'plasma membrane', 'pollen tube elongation', and 'abscisic acid signaling pathway' (Fig. 2c). The DEGs in sterile lines were mainly enriched in 'plasma membrane', 'damage response', and 'abscisic acid response' (Fig. 2d). Therefore, pollen fertility may be closely related to the elongation of pollen tubes and the energy required for pollen wall formation. The DEGs that were downregulated in the maintainer and sterile lines during the late stage were visualized using a Wayne diagram (Fig. 2e), and GO enrichment analysis was performed using these DEGs. Among them, 5,429 DEGs were co-expressed, and these co-expressed DEGs were mainly enriched in 'RNA methylation', 'RNA methylase activity', and 'protein methylase activity' (Fig. 2f). There were 2,861 specifically expressed DEGs in the maintainer lines, which were mainly enriched in 'plasma membrane', 'ATP synthesis', and 'proton transport' (Fig. 2g). In sterile lines, there were 3,304 DEGs, which were mainly enriched in 'cell differentiation', 'positive feedback regulation', and 'catalytic activity' (Fig. 2h). The downregulated expression of genes related to ATP synthesis and proton translocation in the sterile line during the late stage of pollen development illustrated the importance of energy for normal pollen development.

Figure 2.

Functional enrichment analysis of late-stage differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Chinese cabbage Ogura CMS and maintainer lines. (a) Venn diagram quantifying upregulated DEGs: co-expressed and line-specific. (b) GO enrichment of co-expressed upregulated DEGs. (c) GO enrichment of maintainer line-specific upregulated DEGs. (d) GO enrichment of Ogura CMS line-specific upregulated DEGs. (e) Venn diagram quantifying downregulated DEGs: co-expressed and line-specific. (f) GO enrichment of co-expressed downregulated DEGs. (g) GO enrichment of maintainer line-specific downregulated DEGs. (h) GO enrichment of Ogura CMS line-specific downregulated DEGs.

Quality control analysis of degradome sequencing data

-

To identify the target genes of miRNAs obtained from miRNA sequencing, anther samples of Chinese cabbage Ogura CMS lines and their isotype maintainer lines from different pollen development periods were mixed, and a degradome library was constructed and sequenced at a later stage, yielding a total of 19.00 M clean tags. The original tags obtained from sequencing were tested for quality. After quality control, clean tags and cluster tags were obtained, both of which were 47 nt in length, resulting in 18,995,289 clean data (Supplementary Table S9). The cluster tags were compared with the Rfam database to obtain the taxonomic annotation information of non-coding RNAs (Supplementary Table S10).

Using known miRNAs, predicted miRNAs from small RNA analysis, and transcript sequence information of genes of the corresponding species, the genes were analyzed by degradome sequencing to detect degradation sites. A total of 90 genes that were degraded, were detected, of which miR860 targeted and sheared Bra014184 (CCS1) at the 853 bp site, as shown in the T-plot (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Integrated transcriptome and small RNA analysis identifies candidate miRNA-mRNA regulatory networks underlying pollen fertility regulation

-

Relative differentially expressed miRNAs from miRNA, and degradome sequencing of the Chinese cabbage Ogura CMS line and its homozygous maintainer lines during different pollen developmental periods, were jointly analyzed with DEGs identified using transcriptome sequencing. Research has found that miR158, miR159, miR5654, miR860, miR9569, novel_mir_354, novel_mir_403, novel_mir_448, novel_mir_51, and novel_mir_95, these miRNAs and their target genes exhibit differential expression (Supplementary Table S11). The NR annotations for these genes included sucrose transporter protein, growth hormone response factor, cytochrome c biosynthesis protein, cysteine protease, bet v I allergen family proteins, MYB-associated proteins, and adenosine triphosphate-binding and H+-ATPase. Genes related to pollen development were considered candidate miRNAs and target genes for the study.

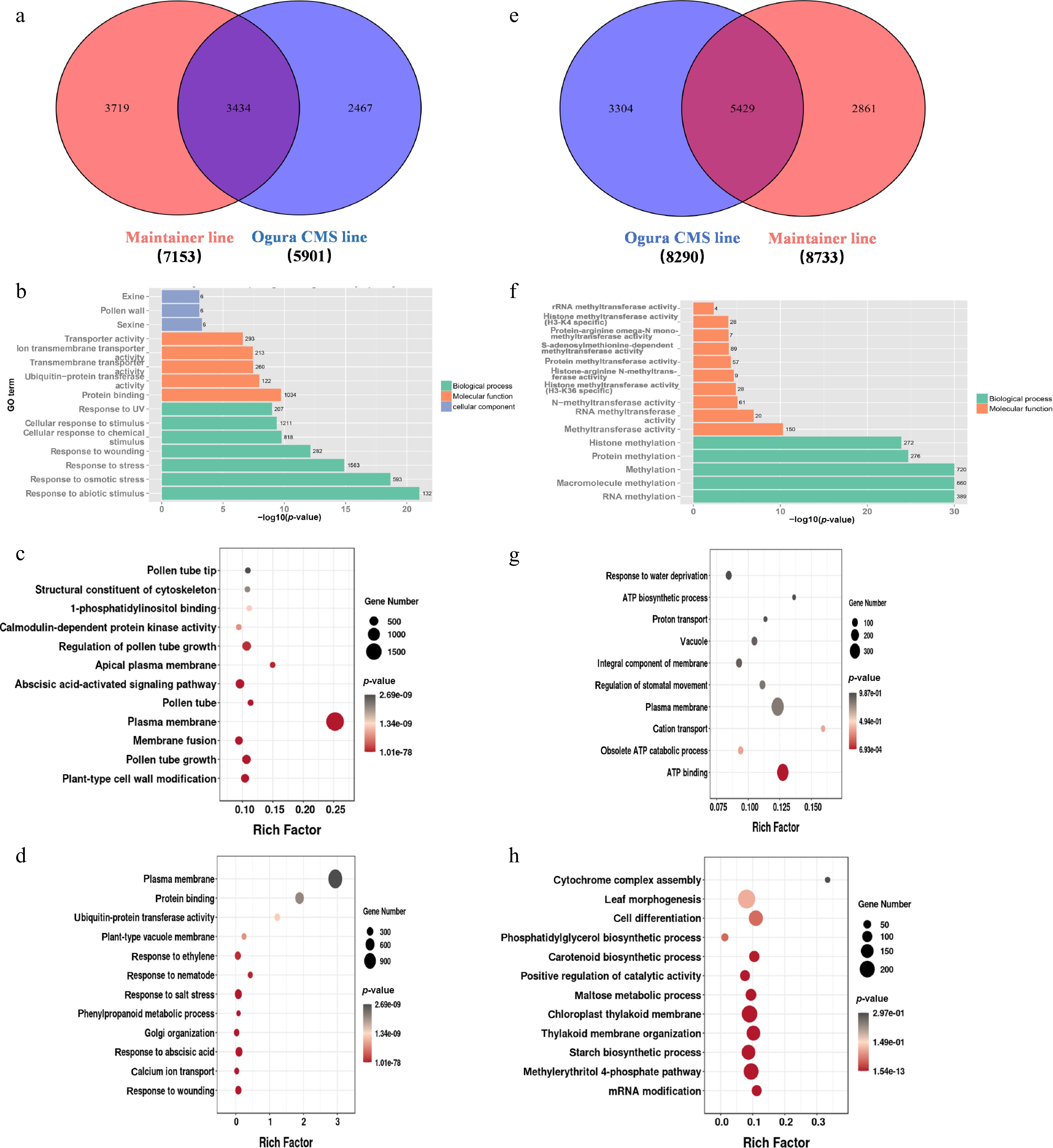

BrCCS1-dependent cytochrome c release triggers PCD in Ogura CMS pollen abortion

-

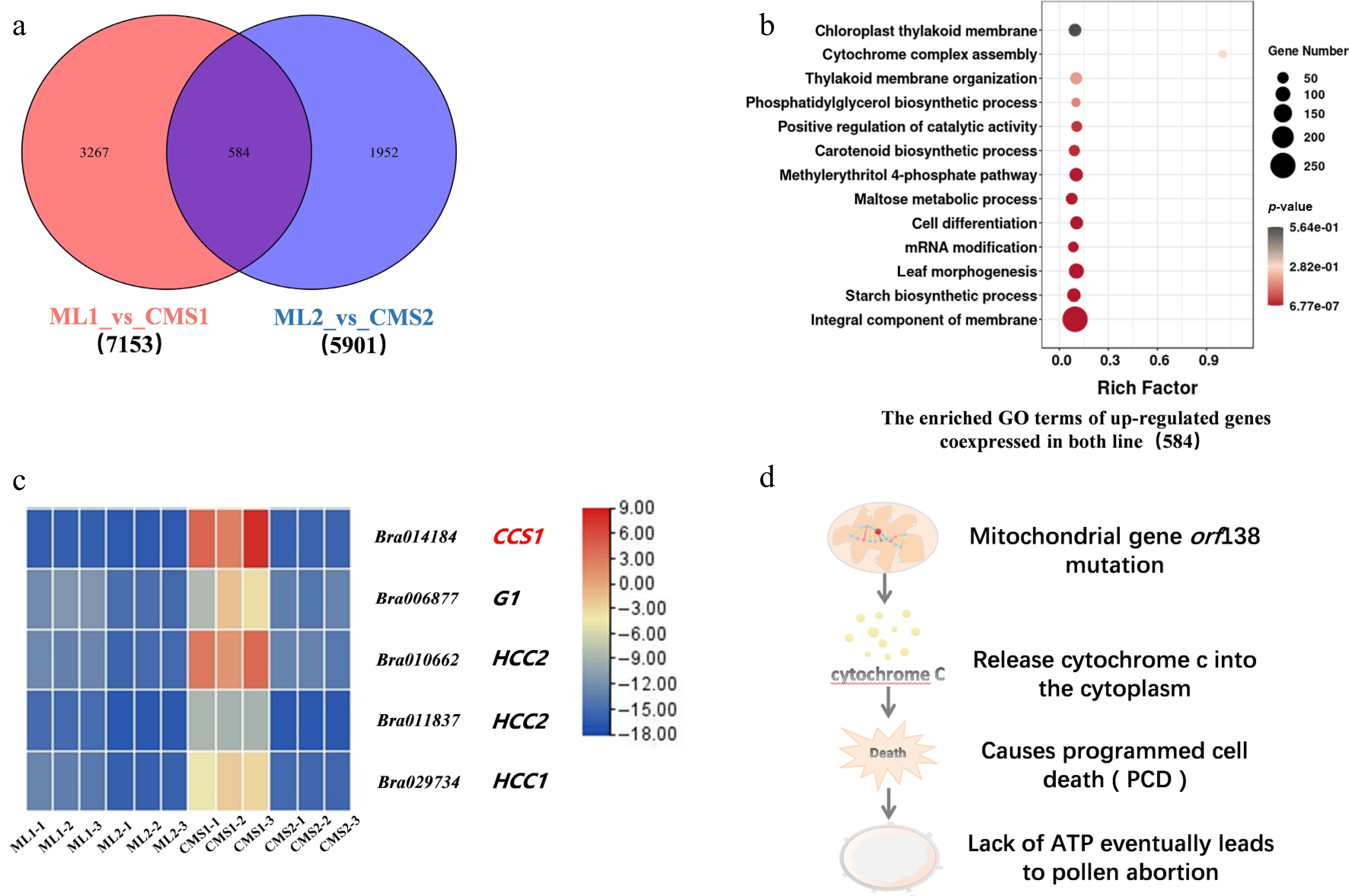

This study was based on sequencing data from the miRNA, transcriptome, and degradome libraries of the Chinese cabbage Ogura CMS line and its isoform maintainer line (NCBI; CNGBdb). Screening of the upregulated genes in the maintainer and sterile lines of Chinese cabbage during the two periods revealed that 584 genes were co-expressed, and 3,267 and 1,952 genes were specifically expressed in the two lines during the early and late stages of pollen development, respectively (Fig. 3a). GO functional enrichment analysis of the differentially expressed mRNAs showed that the co-expressed genes were mainly enriched in 'synthesis and assembly of cytochromes', 'membrane components', and 'positive feedback regulation of catalytic activity' (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Intergroup comparison of upregulated differential gene expression between Chinese cabbage Ogura CMS and maintainer lines. (a) Number of differentially expressed genes specifically expressed and co-expressed between the two groups. (b) GO enrichment analysis of co-expressed upregulated genes between the two groups. (c) Heatmap of cytochrome c-related differential genes in the Chinese cabbage Ogura CMS and maintainer lines. (d) Predictive analysis of the signaling pathway of the downstream cytochrome c response to the mitochondrial mutation.

Further statistical analysis of genes involved in cytochrome synthesis and assembly identified significant upregulation of the BrCCS1 gene in the CMS line specifically during early pollen development development (Fig. 3c). BrCCS1 encodes a cytochrome c biosynthetic protein implicated in cytochrome c formation and mitochondrial function. It facilitates the maturation of cytochrome c through heme-binding. Additionally, genes promoting cytochrome c oxidase synthesis (HCC1, HCC2) were also noted. Significantly, concomitant upregulation of genes associated with Programmed Cell Death (PCD) was observed in the CMS line during early development, suggesting a potential regulatory link between cytochrome c dynamics, and PCD activation.

It was hypothesized that the mitochondrial gene orf138 mutation caused pollen abortion. The mitochondrial gene orf138 mutation in the Chinese cabbage Ogura CMS line caused the upregulation of cytochrome c-related genes encoded by the nucleus, and after cytochrome c was secreted from the mitochondrion into the cytoplasm, it triggered PCD, leading to a lack of energy. This may lead to content degradation and ultimately to pollen abortion (Fig. 3d). Therefore, the present data strongly implicate the cytochrome c synthesis-related gene BrCCS1 as playing a critical role in the anther developmental defects underlying Ogura CMS sterility in Chinese cabbage.

Sequence characterization, target validation, and negative regulation of miR860 on BrCCS1

-

The mature and precursor sequences of miR860 were retrieved from the miRBase database (Supplementary Table S12). Chromosomal localization analysis revealed that pre-miR860 resides on chromosome A06, while its target gene BrCCS1 is located on chromosome A08. The secondary structure of the pre-miR860 was predicted using RNAfold, with the mature sequence position indicated by a red line. Base conservation analysis of the miR860 mature sequence via Weblogo WebLogo demonstrated the highest conservation at the 20th position, followed by the 3rd position. To further confirm the targeting relationship, psRNATarget and psRobot software identified a cleavage site for miR860 at position 853 bp of the CCS1 transcript validating their interaction (Supplementary Fig. S3).

To investigate the negative regulatory role of miR860 on BrCCS1, qRT-PCR was performed on pollen samples from Ogura CMS sterile and maintainer lines of Chinese cabbage across different developmental stages (Supplementary Fig. S4). miR860 expression peaked in the maintainer line but was lowest in the sterile line during late pollen development. Conversely, BrCCS1 expression was suppressed in the maintainer line and significantly increased during pollen development in the sterile line. This inverse expression pattern confirms that miR860 negatively regulates BrCCS1.

To validate sequencing reliability, one known miRNA (miR158a), and two novel miRNAs (novel_miR_95, novel_miR_354) were analyzed by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. S4). Their expression levels were consistent with the sequencing data. Similarly, six differentially expressed genes (DEGs), including genes involved in ATP synthesis and cytochrome c synthesis pathways, exhibited qRT-PCR expression trends concordant with transcriptome sequencing results (Supplementary Fig. S4). Collectively, these data confirm the high reliability of both the miRNA and transcriptome sequencing datasets.

Identification of STTM-miR860 and OE-miR860 transgene-positive seedlings and their qRT-PCR analysis

-

The fragment sizes of the recombinant plasmid were as expected (Supplementary Fig. S5). The structures of STTM-miR860 and OE-miR860 vectors are shown in Supplementary Fig. S6. The constructed vectors were subjected to colony PCR, the results are the same as those shown in Supplementary Fig. S7.

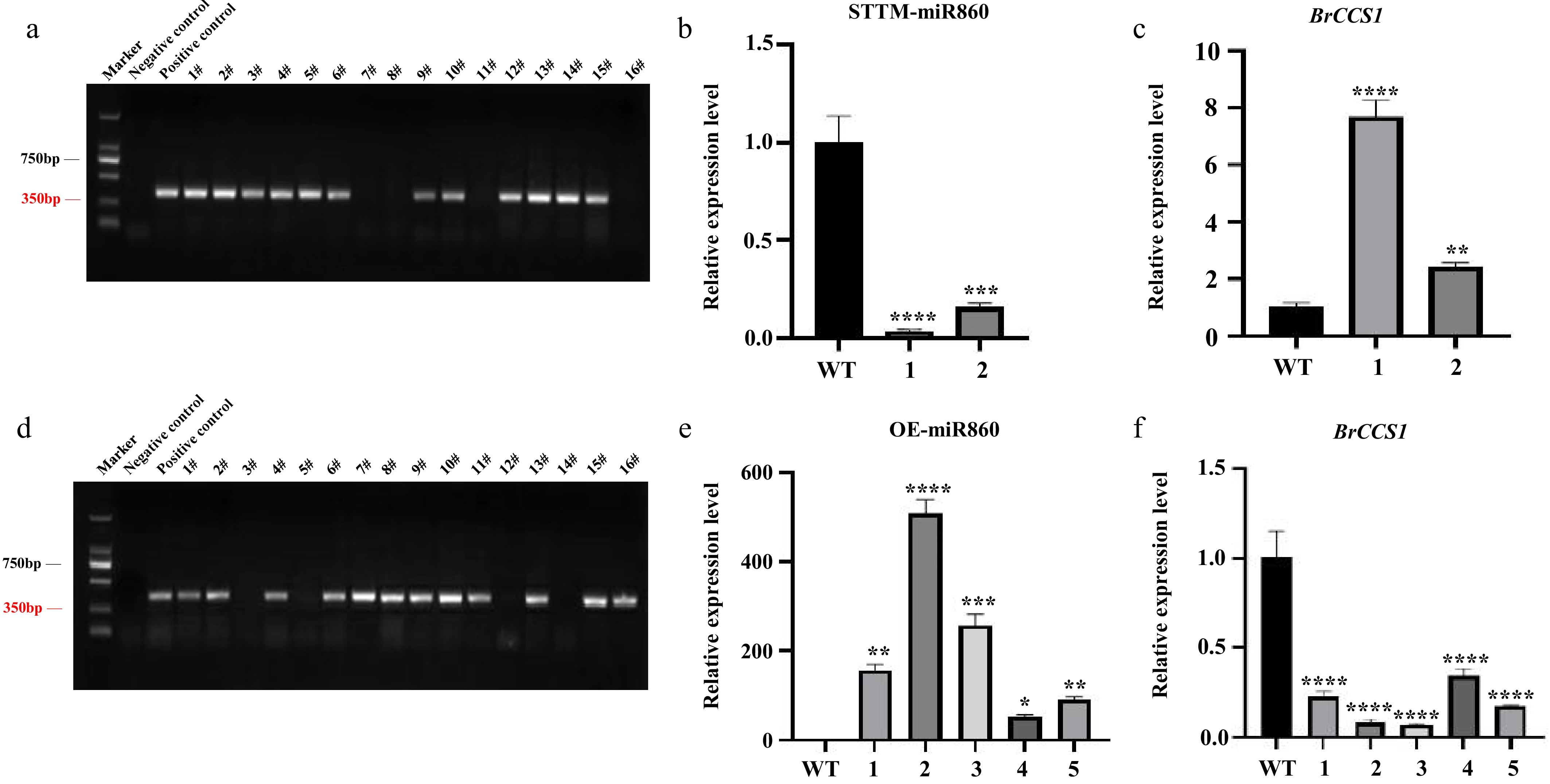

Positive seedlings were initially identified by PCR amplification of their antibiotic sequence fragments, and the presence of bands indicated that the vector was successfully transferred into the plants (Fig. 4a, d). RNA was extracted after 6 weeks, and the expression of miR860 and its target gene BrCCS1 was quantified using fluorescence after designing primers for miR860 expression detection. miR860 expression was significantly reduced in STTM-miR860 transgenic plants compared to wild-type plants (Fig. 4b), while the expression of its target gene BrCCS1 was significantly increased (Fig. 4c). The qRT-PCR results of OE-miR860 transgenic plants contrasted with the former (Fig. 4e, f). Plants with highly significant differences in the expression of the corresponding fluorescence were quantified. miR860 and its target gene BrCCS1 were selected in transgenic Arabidopsis, and the positive transgenic Arabidopsis plants STTM-miR860 and OE-miR860 were identified.

Figure 4.

Identification of transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. (a), (d) PCR identification of T1 generation STTM-miR860 and OE-miR860 transgenic Arabidopsis. (b), (c) qRT-PCR results of miR860 and its target gene BrCCS1 in the T2 generation of STTM-miR860 transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. (e,) (f) qRT-PCR results of miR860 and its target gene BrCCS1 in the T2 generation of OE-miR860 transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. One-way ANOVA using multiple tests (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001).

Functional validation of miR860 in pollen viability and ATP synthesis using transgenic Arabidopsis models

-

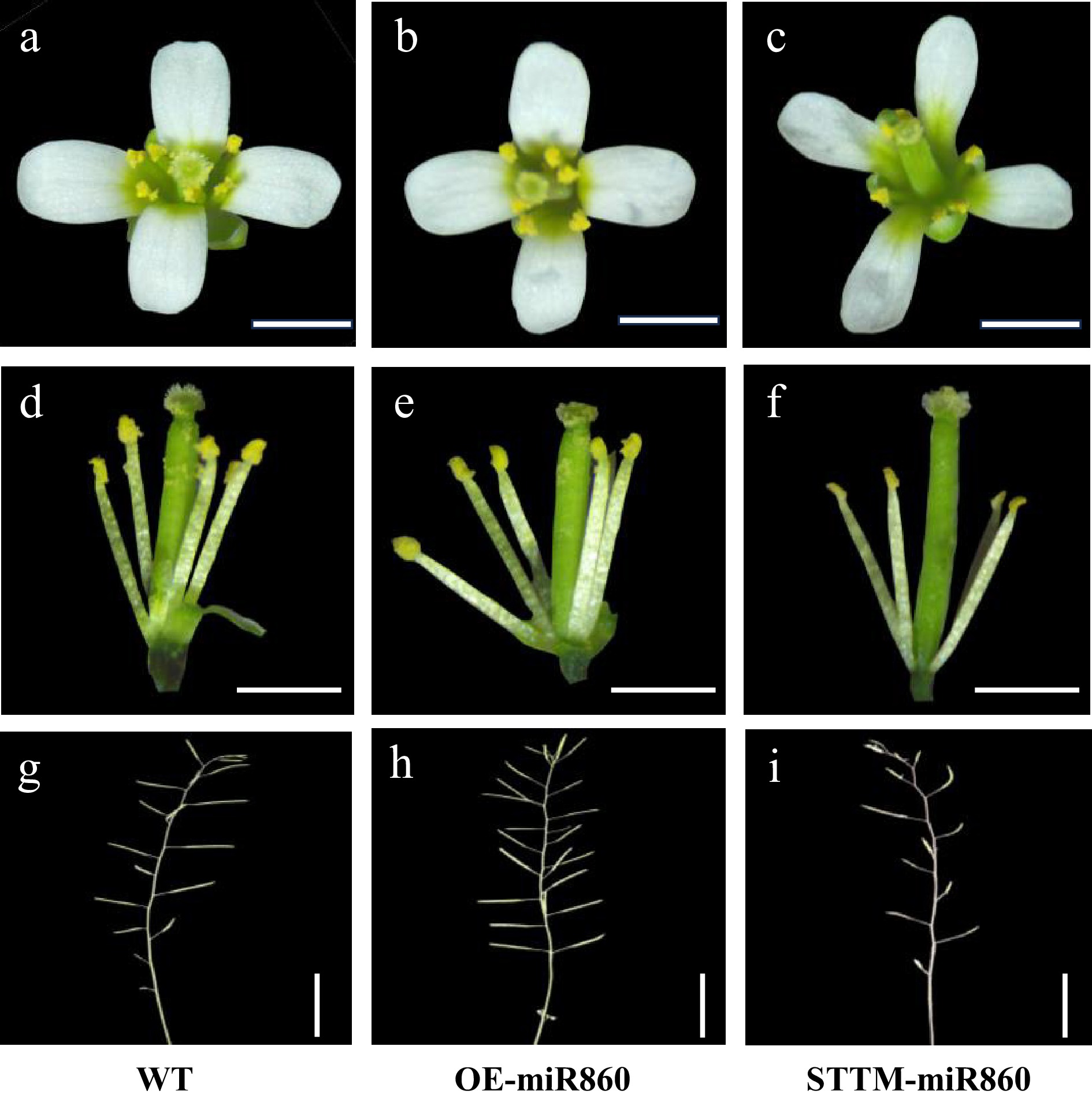

miR860 affects plant pollen fertility to a certain extent by influencing plant physiological and biochemical processes and regulating corresponding molecular mechanisms. Observing the inflorescences of the three materials, we found that wild-type Arabidopsis and OE-miR860 transgenic Arabidopsis had more pollen dispersal during the anthesis stage, whereas STTM-miR860 transgenic Arabidopsis had significantly less pollen dispersal compared with the wild-type (Fig. 5a−c). The anthers of STTM-miR860 transgenic A. thaliana were observed after removing the petals with tweezers, which was consistent with the above characteristics (Fig. 5d−f). The siliques of STTM-miR860 transgenic A. thaliana were smaller than those of the wild type at maturity and appeared shriveled and not full (Fig. 5g, i), while the siliques of OE-miR860 transgenic and wild-type A. thaliana were fuller (Fig. 5h).

Figure 5.

Observation of the phenotypic characteristics of the wild type and miR860 mutant of T3. (a)–(c) Observation of wild-type and miR860 mutant inflorescences. (d)–(f) Observation of anthers and stigmas at anthesis of the wild type and miR860 mutants. (g), (h) Observation of wild-type and miR860 mutant siliques. Scale bars = (a)–(f) 0.5 mm, (g)–(i) 1 cm.

miR860 regulates pollen viability and ATP homeostasis in Arabidopsis

-

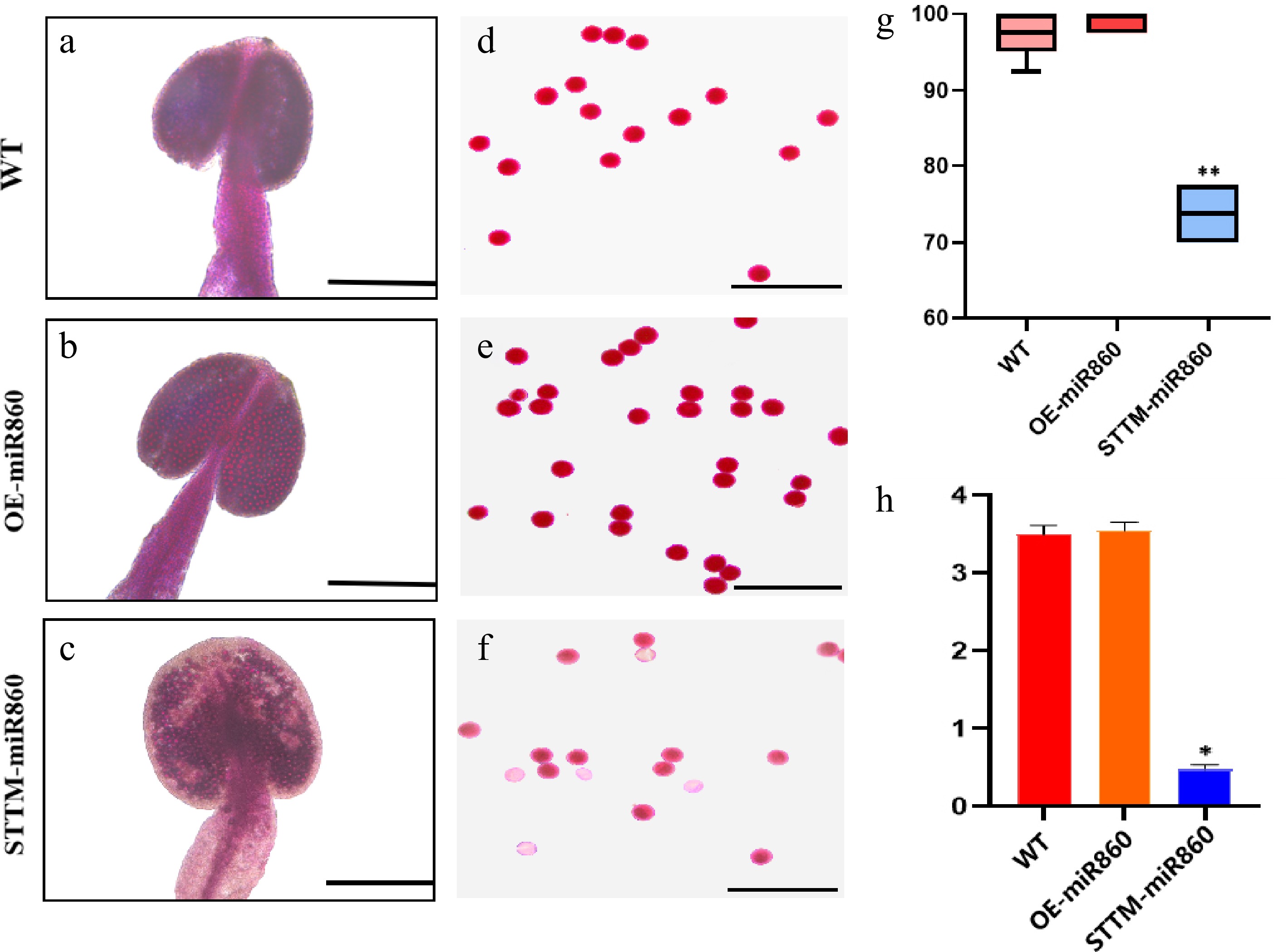

To characterize the pollen viability of STTM860 and OE-miR860 Arabidopsis mutants vs that of wild-type Arabidopsis, the anthers of the three materials were stained and observed in this study using Alexander's staining solution. The entire anthers of wild-type and OE-miR860 transgenic Arabidopsis were stained purple-red, indicating that they were filled with viable pollen grains (Fig. 6a, b). Piecewise staining revealed that both pollen grains were stained with purple-red color and a full ellipsoid shape (Fig. 6d, e). Wild-type and OE-miR860 transgenic A. thaliana had extremely high pollen grain stainability (Fig. 6g). In contrast, STTM-miR860 transgenic A. thaliana showed some pollen that was inactive and transparent compared with the wild type, and some inactive pollen grains could not be stained a purple-red color (Fig. 6c, f). The rate of pollen grain staining was significantly reduced (Fig. 6g). The anther ATP content of the three materials was determined. Wild-type and OE-miR860 transgenic A. thaliana had a higher anther ATP content (more than 3 µmol/g), while STTM-miR860 transgenic A. thaliana had a significantly lower anther ATP content compared with wild-type and OE-miR860 transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. These findings suggest that miR860 affects pollen fertility by influencing ATP synthesis. The downregulation of miR860 expression causes pollen inactivity or the inability to form normal, full ellipsoidal pollen grains, decreasing plant fertility.

Figure 6.

Identification of pollen viability and determination of ATP content in the wild type and miR860 mutants. (a)–(c) Alexander rectification staining of anthers. Scale bar = 200 μm. (d)–(f) Alexander staining of pollen grains. Scale bar = 100 μm. (g) Stainability statistics (%). (h) ATP content determination (µmol/g). One-way ANOVA using multiple tests (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01).

Anther ultrastructure and ROS accumulation analysis reveals miR860-dependent pollen abortion mechanisms

-

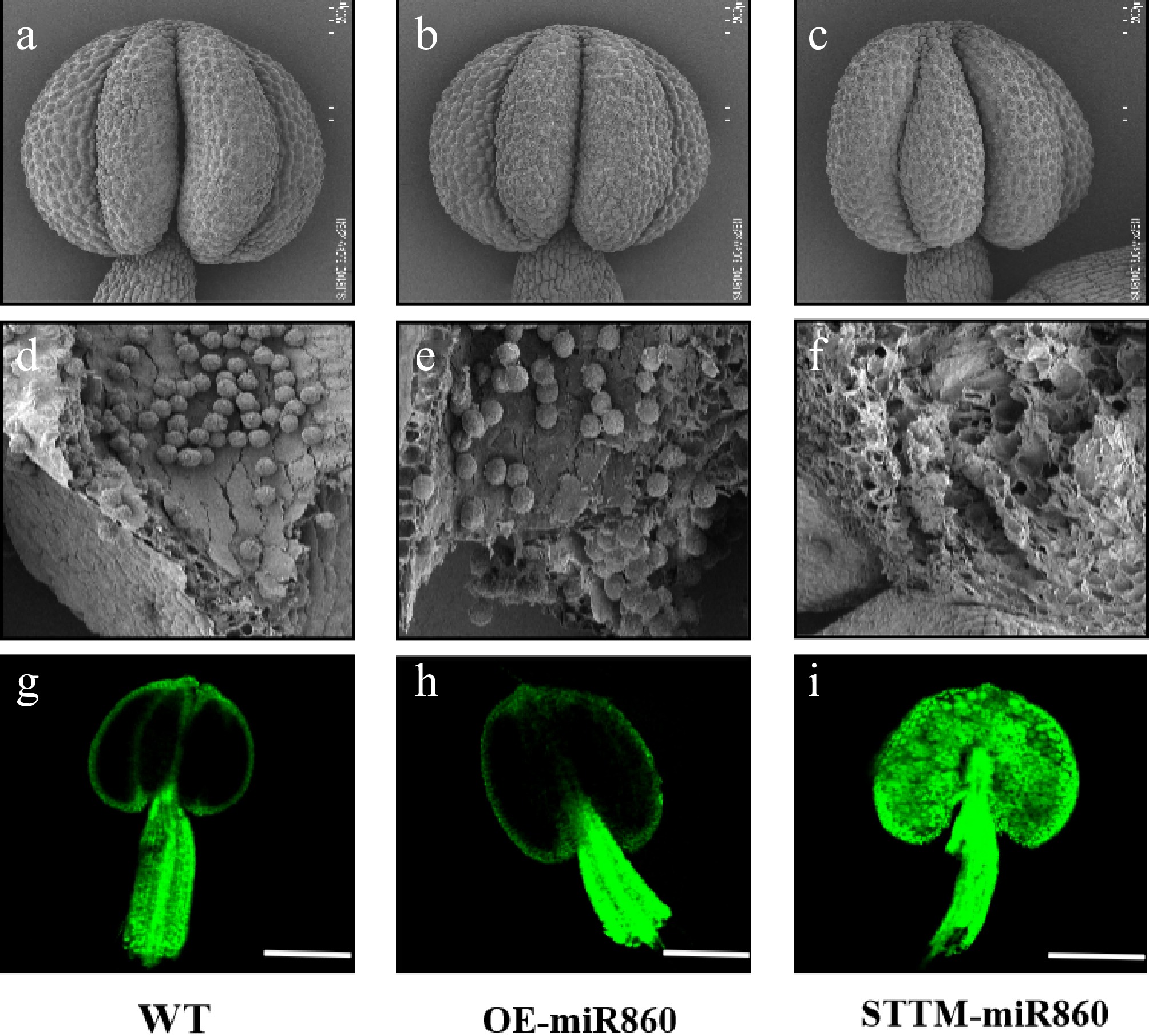

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of anthers and pollen grains from wild-type (WT), OE-miR860, and STTM-miR860 transgenic Arabidopsis lines revealed no significant morphological differences in anthers at the flowering stage; anther size and structure were comparable across all genotypes (Fig. 7a, c). Wild-type and OE-miR860 transgenic Arabidopsis had a large number of full pollen grains inside the anthers (Fig. 7d, e), and STTM-miR860 transgenic Arabidopsis showed empty chambers inside the anthers with fewer viable pollen grains (Fig. 7f). By detecting reactive oxygen species (ROS) in anthers, the results showed that ROS accumulation was significantly reduced in WT and OE-miR860 plants (Fig. 7g, h). Conversely, STTM-miR860 anthers displayed substantially elevated ROS levels (Fig. 7i). In summary, OE-miR860 transgenic Arabidopsis anthers developed normally with full pollen grains and almost no ROS accumulation, whereas STTM-miR860 transgenic Arabidopsis anthers had almost no normal pollen grains in the inner part of the anthers. Therefore, we hypothesized that ROS accumulation in the inner part of the anthers was toxic and led to the reduction of pollen fertility.

Figure 7.

Ultrastructural scanning electron microscopy observation and identification of reactive oxygen species in wild-type and miR860 mutant anthers. (a)–(c) Wild-type and miR860 mutant anthers at the unopened stage. (d), (e) Wild-type and OE-miR860 anthers with normal full pollen grains. (f) STTM-miR860 mature anthers at the unopened stage, locally enlarged to show empty chambers. Scale bars: (a)–(c) 200 μm, (d)–(f) 50 μm. (g)–(i) Confocal microscopy observation of reactive oxygen staining. Scale bar = 200 μm.

-

In this study, the anthers of the Chinese cabbage Ogura CMS line and its isotype maintainer line during different pollen development stages were used as experimental materials. sRNA, degradome, and transcriptome sequencing were performed, and the sequencing data were analyzed for quality control and high confidence. A total of 87 known miRNAs were identified, and 265 new miRNAs were predicted by miRNA sequencing. Most of the known miRNAs and newly predicted miRNAs were 21 nt in length. There were 183 differentially expressed miRNAs between the sterile and maintainer lines during late pollen development, and GO enrichment analysis showed that the target mRNAs of these differentially expressed miRNAs were enriched in biological processes, such as multicellular bioprocesses, reproduction, and the immune system, which is in line with a previous study[46].

Based on the transcriptome sequencing analysis, 6,580 and 5,771 differentially expressed mRNAs were identified in the maintainer and sterile lines, respectively, during the early and late stages of pollen development. A total of 2,861 genes were specifically expressed in the maintainer line, and they were mainly enriched in the plasma membrane, ATP synthesis, and proton translocation. There were 3,304 genes specifically expressed in the sterile line, and they were mainly enriched in cell differentiation, positive feedback regulation, and catalytic activity, suggesting that most of the target genes were related to plant growth, development, and metabolic activities, in line with the results of a previous study[47]. The downregulated expression of genes related to ATP synthesis and proton translocation during late pollen development in sterile lines indicates the importance of energy metabolism for normal pollen development. Cytochrome c synthesis-related genes were significantly upregulated in the Chinese cabbage Ogura CMS line during early anther development. Statistical analysis of the expression of the related genes showed that CCS1 was highly expressed in the sterile lines and less expressed in the maintainer lines, showing significant differences.

Pollen abortion may be caused by a lack of viable pollen grains. The present study showed that changes in miR860 expression affected pollen development, consistent with the results of a previous study[48]. Pollen fertility may be affected by the ROS and ATP contents in anthers[49]. Pollen development in plants is a complex metabolic process that requires large amounts of energy[50], and the results of this study demonstrated that changes in ROS and ATP levels in miR860 mutant material result from miR860 negatively regulating the expression of its target gene (BrCCS1). In studies related to male sterility in rice, a ROS burst[51,52] in anthers has been shown to disrupt redox processes, causing abnormalities in sugar and lipid metabolism and loss of the chorioallantoic zymosome, ultimately resulting in sterility. CCS1 is a component encoding the biosynthesis of system II cytochrome c, which is an important part of the electron transport chain and which affects energy formation. Over-synthesizing cytochrome c and releasing it into the cytoplasm results in the inability of chorionic villous cells to complete PCD in a timely manner and to accumulate ROS, resulting in the inability to produce normal pollen grains, which affects pollen development[29,27,50].

Based on the results of the above studies, a pattern of pollen abortion triggered by mutations in the mitochondrial gene orf138 was explored (Fig. 8). Mutations in the mitochondrial gene orf138, which regulates the expression level of miR860, negatively regulate the upregulation of cytochrome c synthesis-related gene CCS1, accelerating the downstream synthesis of excess cytochrome c released into the cytoplasm, resulting in the early onset of PCD of the tapetum layer, which leads to the accumulation of large quantities of ROS, blocking the synthesis of downstream ATP, and the lack of energy, resulting in the prevention of normal pollen wall formation, ultimately leading to pollen exhaustion. In conclusion, this model elucidates the mechanism of bra-miR860 in cytoplasmic male sterility, provides new insights into the mechanism of cytoplasmic male sterility in this species, further lays a theoretical foundation for the study of sterile lines in Chinese cabbage and provides new ideas for hybrid seed production and other practical applications.

-

In this study, we sequenced miRNAs, the transcriptome, and the degradome in sterile and maintainer lines of Chinese cabbage during different periods of pollen development and identified miR860 and the target gene BrCCS1, which were specifically expressed in the two lines during different periods of pollen development. miR860 silencing and overexpression vectors were constructed, and Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis was used to obtain positive seedlings of transgenic plants. Functional verification of miR860 associated with pollen fertility in the Ogura CMS line of Chinese cabbage was carried out using mutant phenotyping, pollen viability characterization, and measurement of ATP and ROS. The mitochondrial gene orf138 mutation negatively regulates the expression of miR860, and the cytochrome c synthesis-related gene BrCCS1 is upregulated. This accelerates the downstream cytochrome c over-synthesis and release into the cytoplasm, resulting in premature PCD in the tapetum layer, causing high ROS accumulation, blocking downstream ATP synthesis and preventing the normal pollen wall formation, which ultimately results in pollen abortion due to the lack of energy. In this study, the function of miR860 in regulating male sterility in the Ogura-type cytoplasm of Chinese cabbage from morphological observations, cytological observations, histological analyses, and related physiological experiments was elucidated. However, the mechanism by which miR860 regulates ATP synthesis of its target gene BrCCS1 to regulate pollen fertility in plants needs to be further investigated.

-

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. The transcriptome data can be found here: National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) BioProject database under Accession No. PRJNA657160. The miRNAs and degradome data can be found here: China National GeneBank DataBase (CNGBdb) under Accession Nos CNP0006167 and CNP0006176.

This work was supported by the Joint Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U24A20417); Zhongyuan Sci-Tech Innovation Leading Talents (244200510041); China Agricultural Research System (CARS-25-G15); Innovation Team of Henan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2025TD06). We thank Ms. Yuanlin Zhang, School of Agricultural Sciences, Zhengzhou University, for the pre-experiment and data collection for the improvement of this manuscript.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception: Yuan Y, Zhang X; experiments design: Wei F, Wei X; performing experiments and data analysis: Yang S, Su H; qRT-PCR and phenotype identification: Zhang W, Zhao Y, Tian B; draft manuscript preparation: Wei X, Xiong S; manuscript revision and finalization: Wei X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Anther Sample Information Sheet.

- Supplementary Table S2 Sequences of qRT-PCR primers for related miRNAs.

- Supplementary Table S3 Sequences of qRT-PCR primers for related mRNAs.

- Supplementary Table S4 Evaluation statistics of sample sequencing data.

- Supplementary Table S5 Statistical results of alignment information with reference genome sequence.

- Supplementary Table S6 miRNA sequencing results of different pollen development periods in Ogura-type cytoplasmic male sterile and maintained lines of Chinese cabbage.

- Supplementary Table S7 Anther sample sequencing data evaluation statistics (two lines).

- Supplementary Table S8 The sequence alignment results of the sample sequence data with the reference genome.

- Supplementary Table S9 Degradome sequencing analysis results.

- Supplementary Table S10 RNA alignment Rfam results statistics.

- Supplementary Table S11 Differentially expressed miRNAs targeting differentially expressed mRNAs during different developmental periods in pollen of Ogura CMS and maintained lines of cabbage.

- Supplementary Table S12 The information of miR860.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Analysis of transcriptome sequencing results.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 miR860 shears the target gene Bra014184 (CCS1) at position 853.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Information related to miR860 and its target genes.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 qRT-PCR validation of miRNAs and related mRNAs.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 Recombinant plasmid verification gel electrophoresis.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 Schematic diagram of carrier construction.

- Supplementary Fig. S7 Colony PCR gel electrophoresis.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wei X, Xiong S, Zhao Y, Zhang W, Yang S, et al. 2025. bra-miR860 targets the BrCCS1 gene to positively regulate programmed cell death linked to ROS in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Vegetable Research 5: e043 doi: 10.48130/vegres-0025-0038

bra-miR860 targets the BrCCS1 gene to positively regulate programmed cell death linked to ROS in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis)

- Received: 13 June 2025

- Revised: 25 August 2025

- Accepted: 08 September 2025

- Published online: 13 November 2025

Abstract: Cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS), particularly the Ogura type characterized by complete pollen abortion, is a key mechanism for hybrid seed production. While the mitochondrial gene orf138 is known as the sterility factor in Ogura CMS, its precise molecular mechanism remains unclear, and the role of microRNAs (miRNAs) in Ogura CMS Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis) are understudied. To elucidate miRNA involvement, the Ogura CMS line (Tyms) and its homozygous maintainer line (Y231-330) were utilized. Integrated analysis of miRNA, transcriptome, and degradome sequencing data (validated by rigorous quality control) revealed 2,861 genes specifically expressed in the maintainer line. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment highlighted their roles in 'plasma membrane', 'ATP synthesis', and 'proton transport', underscoring the critical importance of energy metabolism for normal pollen development. Functional validation was performed by constructing bra-miR860 overexpression, and short tandem target mimic (STTM) vectors for transformation in Arabidopsis thaliana, followed by phenotypic and physiological analysis. This study delineates a molecular pathway linking the mitochondrial orf138 mutation to pollen abortion: orf138 mutation downregulates bra-miR860, leading to the upregulation of its target gene BrCCS1 (Cytochrome c biogenesis). Consequently, cytochrome c is over-synthesized, leaks from mitochondria into the cytosol, and triggers premature programmed cell death (PCD) in tapetal cells. This PCD is accompanied by reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, resulting in energy deficiency, cellular content degradation, and ultimately, the failure to produce viable pollen. The present findings elucidate the molecular mechanism of orf138-induced sterility and provide a novel theoretical foundation for utilizing Ogura CMS in Chinese cabbage hybrid seed production.

-

Key words:

- Chinese cabbage /

- Ogura cytoplasmic male sterility /

- bra-miR860 /

- BrCCS1 gene /

- Reactive oxygen species