-

Epigenetic traits are heritable phenotypic variations mediated through chromatin modifications rather than modifications to the actual DNA sequence[1]. DNA methylation, histone modifications, non-coding RNAs, etc., collectively modulate chromatin accessibility across genomic regions. These chromatin-based regulatory mechanisms define the classical boundaries of epigenetics, a field that originated from developmental biologists' efforts to explain non-Mendelian inheritance patterns and evolved to encompass diverse biological contexts[2]. Classical Mendelian traits (e.g., pea color, digit number, fruit size) arise from allelic variation caused by DNA sequence mutations[3]. Darwinian evolution, through its emphasis on mutation and natural selection as evolutionary forces, laid the groundwork for classical genetic theory. Non-Mendelian inheritance patterns, including X-chromosome inactivation and paramutation, are allele-specific expression states that are heritable despite unchanged DNA sequences. These epigenetic phenomena produce stable phenotypic outcomes distinct from both classical Mendelian traits and mitochondrial maternal inheritance. Cell division preserves chromatin states that support heritable gene expression patterns and largely preserves epigenetic information with high fidelity; however, DNA replication and cell division furnish crucial opportunities for changes to occur[4]. Epigenetic regulation governs fundamental biological processes, including cell fate determination, stem cell plasticity, organogenesis, ageing, reproductive development, and environmental adaptation. While numerous studies have established the critical role of epigenetic modifications in these processes, the relative contributions of genetic vs epigenetic determinants remain unresolved. Emerging evidence positions epigenetics as a central research paradigm in the post-genomic era, bridging the gap between genotype and phenotype.

-

In prokaryotes, cytosine can undergo methylation at the N4 position (forming 4mC) or the C5 position (5mC), while adenine can be methylated at the N6 position (yielding 6mA). Although genomic methylation levels are relatively low (e.g., in E. coli, ~0.5%–0.8% of cytosines and 1.5%–2% of adenines are methylated), these modifications contribute to gene regulation and host defense mechanisms[5]. In contrast, eukaryotes 5mC predominates, with 6mA restricted to certain unicellular organisms. Notably, 4mC has only recently been identified in eukaryotic sperm maturation[6]. Given the limited distribution and characterization of 4mC and 6mA in eukaryotes, this discussion will focus primarily on 5mC.

5mC was first identified in bacterial DNA in 1925, but its fundamental biological significance remained elusive for decades. The 1980s marked a pivotal decade for DNA methylation research, establishing 5mC as a key regulator of gene expression and revealing its genomic distribution[7]. DNA methylation of cytosine residues is now one of the most well-characterized epigenetic marks associated with heritable gene silencing[8]. 5mC is generated through enzymatic methylation of cytosine residues in DNA, where DNA methyltransferases catalyze the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to the fifth carbon position of the cytosine ring[9].

-

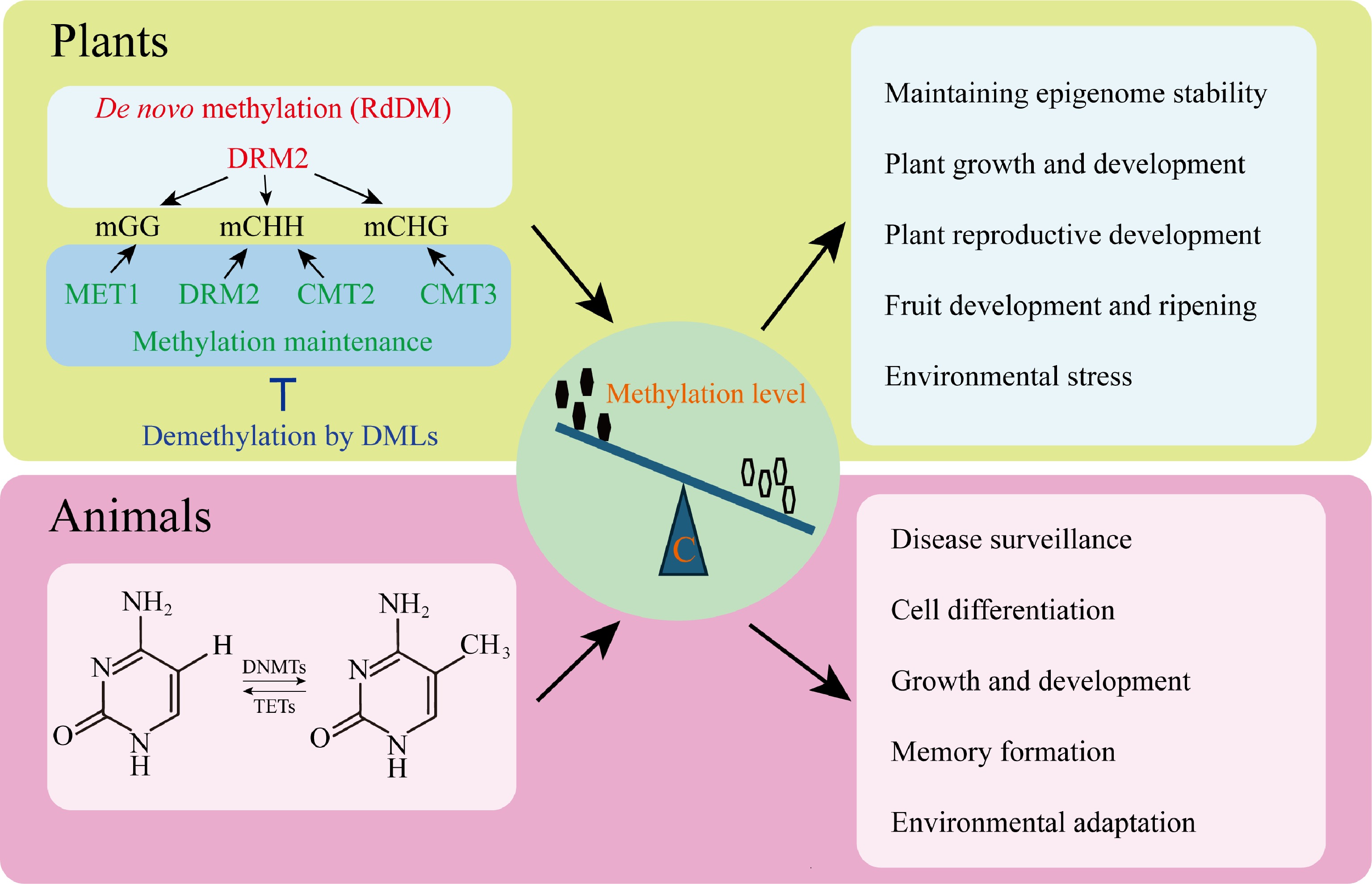

Plants have the most diverse repertoire of epigenetic modifications among eukaryotes, using all the central known regulatory mechanisms to control biological processes. Their genome epigenetic networks are the most complex and versatile. DNA methylation in plant genomes is in CG, CHG, and CHH sequence contexts, with a dynamic balance between maintenance, RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM), and erasure enzymes (Fig. 1)[8].

Figure 1.

Core regulatory mechanisms of DNA methylation in eukaryotes. Cytosine DNA methylation is self-regulated both during maintenance and de novo in plants. The RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway uses the DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLTRANSFERASE TWO (DRM2) to recruit de novo methylation and METHYLTRANSFERASE1 (MET1) to maintain CG methylation. DNA methylation in plants is maintained by plant-specific CHROMOMETHYLASEs (CMTs), while CHH methylation is maintained by CMTs and DRM2, both independently and in conjunction with RdDM. It is counteracted by DNA demethylases such as REPRESSOR OF SILENCING ONE (ROS1), DEMETER (DME)-LIKE TWO (DML2), and DML3 that activate the expression of genes. The combination of these pathways ensures the stability of epigenetics and controls key biological functions, including plant development, reproduction, fruit development, and ripening, as well as the stress response. The CpG dinucleotides of DNA methylation are mainly confined to animals and regulated by the counteracting activities of DNA METHYLTRANSFERASEs (DNMTs) and ten-eleven translocation (TET) proteins. This control equilibrium supports the process of development, cell differentiation, defense against disease, formation of memory, and adaptation to the environment.

DNA methylation is a core epigenetic process that provides genome stability while also regulating phenotypic plasticity in flora. Recent findings have shown that the DNA demethylase ROS1 (REPRESSOR OF SILENCING1) in Arabidopsis serves as a surveillance factor, averting the increase of aberrant methylation over generations and increasing epigenome stability[10]. Such a regulatory role is significant in the process of sexual reproduction, when the state of differentiation of methylation of sperm and egg cells is reorganized in the zygote to create a balanced epigenetic environment to protect the integrity of the genome[11].

Effects of DNA methylation on the growth and development of plants occur via precise regulation of gene expression. MET1 regulates the CG methylation in Arabidopsis, and its deletion increases regeneration ability, dynamically changing methylation in cellular reprogramming[12]. A wide range of DNA methyltransferases (MET1, DRM1/2, CMT3/2) are disrupted, making non-CG methylation in morphogenesis essential[13]. Likewise, DRM and CMT gene mutations induce sterility and developmental defects in rice, and deletions of both genes in multiple combinations intensify the phenotypes[14]. Natural variation in maize ZMET2 further demonstrates how CHG methylation fine-tunes tissue-specific gene expression, influencing traits such as bract development[15]. Additionally, DEMETER (DME)-mediated demethylation is critical for seed germination and shoot regeneration, illustrating the need for balanced methylation dynamics in developmental transitions[16].

Reproductive development in plants is tightly regulated by DNA methylation. The establishment of a single megaspore mother cell (MMC) depends on a precise methylation-demethylation equilibrium, with deviations leading to aberrant cell fate determination[17]. During pollen development, PEM1 ensures proper exine formation, and its dysfunction disrupts pollen wall architecture, leading to sterility[18]. CHH methylation, particularly enriched at transposable elements in shoot apical meristems, is further amplified in reproductive tissues via RNA-directed DNA methylation, ensuring genome stability during meiosis[19]. In rice, OsRDR2-dependent siRNA accumulation maintains CHH methylation, which in turn regulates stamen development and pollen viability[20]. Beyond reproduction, DNA methylation also modulates fruit ripening, with species-specific trends—hypomethylation accelerates ripening in tomato and strawberry, whereas hypermethylation delays it in sweet orange[21,22].

Importantly, DNA methylation serves as a key mediator of environmental adaptation. Under osmotic stress, there are dynamic methylation changes at drought-responsive gene promoters in wheat, correlating with transcriptional activation[23]. Strikingly, contrasting methylation patterns emerge in stress-tolerant rice cultivars—hypomethylation in drought-resistant Nagina22 vs hypermethylation in salt-tolerant Pokkali—suggesting divergent epigenetic strategies for stress adaptation[24]. Environmental induction of DNA methylation variation can confer stable, stress-independent epigenetic inheritance, enhancing adaptive capacity in plants. Using rice as a model system to study the increase in cold tolerance adaptation during its northward expansion, Song et al. clarified the molecular mechanisms that govern the acquisition and heritable transmission of low-temperature-adaptive traits[25]. High-temperature stress in cotton disrupts methylation patterns, leading to metabolic dysregulation and male sterility[26]. Furthermore, ROS1-mediated demethylation fine-tunes immune responses to bacterial pathogens, linking epigenetic regulation to disease resistance[27].

Most importantly, causative tests show that the process of methylation actively controls phenotypic plasticity and acclimation. As an illustration, the DNMT3a knockout in zebrafish results in developmental thermal plasticity defects, and sequential DNMT3a isoforms have an additive effect on survival and morphology in response to thermal stress[28]. In Arabidopsis, the dynamic induction of hyperosmotic stress memory occurs through the dynamic methylation of key loci, which directly leads to generation-wide adaptive behavior[29]. Recent advances in epigenome editing further support that the information of directed changes in DNA methylation influences the process of memory formation and drought and stress priming[30]. Reviews based on these causative tests indicate the direct contribution of methylation to environmental responsiveness and adaptive plasticity.

The conclusions place DNA methylation as a highly dynamic regulatory layer that incorporates both developmental programming and environmental sensing, which can be of great importance in the development of stress-tolerant crops and evolutionary adaptation (Fig. 1). Future studies need to further decompose the mechanistic interaction between methylation dynamics and phenotypic plasticity in a variety of plant species.

-

Unlike in plants, animal DNA methylation is limited primarily to CpG dinucleotides, except for invertebrates such as nematodes and Drosophila. This methylation pattern is dynamically regulated through the opposing actions of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and demethylases (TETs), rather than the RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway that drives de novo methylation in plants (Fig. 1)[8].

DNA methylation serves as a critical epigenetic regulator linking environmental exposures to disease susceptibility. Dietary factors, including folic acid, vitamin B12, and vitamin D, modulate cancer risk by altering DNA methylation patterns through effects on methyltransferase activity, methyl donor availability, and oxidative stress[31]. Clinically, hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes such as RASSF1A in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients not only provides early diagnostic biomarkers but also enables monitoring of treatment response and recurrence[32]. Beyond cancer, aberrant methylation contributes to neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, where C9orf72 promoter hypermethylation drives toxic protein accumulation[33], and to endocrine disorders such as polycystic ovary syndrome, with CYP19A1 promoter methylation reducing aromatase activity in granulosa cells[34].

It is becoming increasingly evident that DNA methylation plays a role in the pathophysiology of various diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disorders.[35]. As it provides transcriptional control, changes in the state of methylation impair cellular self-regulation and promote the course of the disease[35]. Notably, these epigenetic marks are reversible, and they may be treated in the form of therapy. Massive reprogramming of methylation instructions is a hallmark of cancer. Global hypomethylation and hypermethylation of anarthinogenes can facilitate genomic instability and oncogene and tumor suppressor gene expression[36]. The reversibility of these epigenetic processes has given rise to epigenetic therapies of the DNA methylation machinery[36]. In addition to nuclear DNA, abnormal methylation in the mitochondrial genome has also been reported in both animal models and human tissue with cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, and obesity, among others[35]. Although the specific mechanisms are under investigation, mitochondrial methylation is considered to negatively affect the functioning of mitochondria, thereby increasing the extent of metabolic malfunction and disease pathogenesis[35]. Considering the pivotal role that mitochondria play in energy homeostasis and apoptosis, additional study of mitochondrial epigenetics may be a way to better understand and treat complex diseases.

Developmental regulation by DNA methylation is equally significant. During cellular differentiation, DNMT3A and DNMT3B establish lineage-specific methylation patterns to guide embryonic stem cells toward distinct fates[37]. Neural stem cells maintain unique methylation signatures, distinguishing them from differentiated astrocytes[38]. The MBD2/3-Tip60 complex exemplifies how methyl-CpG binding proteins integrate methylation signals with chromatin remodeling to control gene expression[39]. Embryonic lethality in Zmym2 knockout mice underscores the necessity of methylation-dependent silencing of germline genes during development[40].

Remarkably, DNA methylation dynamics extend to diverse physiological processes. In neuroscience, memory formation involves coordinated methylation and demethylation of thousands of hippocampal genes[41]. Social insects such as honeybees demonstrate methylation's role in caste determination, where royal jelly-induced Dnmt1 hypomethylation activates queen-specific pathways[42]. Comparative epigenomics can identify species-specific patterns of ageing, as in the case of short-lived bats, which have age-dependent accumulation of methylation that is not observed in long-lived species, providing information on longevity[43]. Environmental responses are also remarkable: a long-term cold environment causes the brown adipose tissue methylome to control thermogenesis. In species whose sex determination is dependent on the environment, the temperature-dependent kinetics of Dmrt1 methylation are regulated by the mechanism[44]. These results highlight the significance of genotype-environment-phenotype interactions, particularly in terms of DNA methylation, which have significant implications for disease mechanisms, developmental biology, and evolutionary adaptation. Future research, potentially involving the dissection of context-specific methylation processes, is essential to translate these findings into therapeutic and diagnostic benefits.

-

Histone methylation, one of the major post-translational modifications that takes place at the lysine and arginine sites of DNA-bound histones, is one of the basic regulatory mechanisms in the organization of chromatin in eukaryotes. This modification occurs primarily at the N-terminal tails of histones H3 and H4, where histone methyltransferases (HMTs) add methyl groups of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to valine amino acid residues[45]. Recent studies have defined histones as exceptionally dynamic proteins that undergo various forms of modification, including methylation, acetylation, and phosphorylation, which work together to coordinate major nuclear functions. One such modification is lysine methylation (mono-, di-, and trimethylation) that forms a complex epigenetic code by which transcriptional activity of euchromatin or silencing of heterochromatin is determined[46]. Methylation of histone H3 is dynamically maintained through the opposing actions of lysine methyltransferases (KMTs) and demethylases (KDMs), which precisely control the addition or removal of methyl groups at specific residues. KMTs contain a highly conserved SET catalytic domain, whereas KDMs are classified into two major families: lysine-specific demethylases (LSDs) and Jumonji C (JmjC) domain-containing demethylases (JHDMs). Both KMTs and KDMs have precise substrate specificity, targeting distinct lysine residues and methylation states on histone tails. Consequently, each enzyme exerts unique regulatory effects on chromatin structure and transcriptional activity, contributing to diverse biological functions. This review brings together current understanding of how H3 lysine methylation governs gene expression patterns, maintains genomic integrity, and contributes to cellular differentiation programs, while highlighting its implications for both normal physiology and disease states.

-

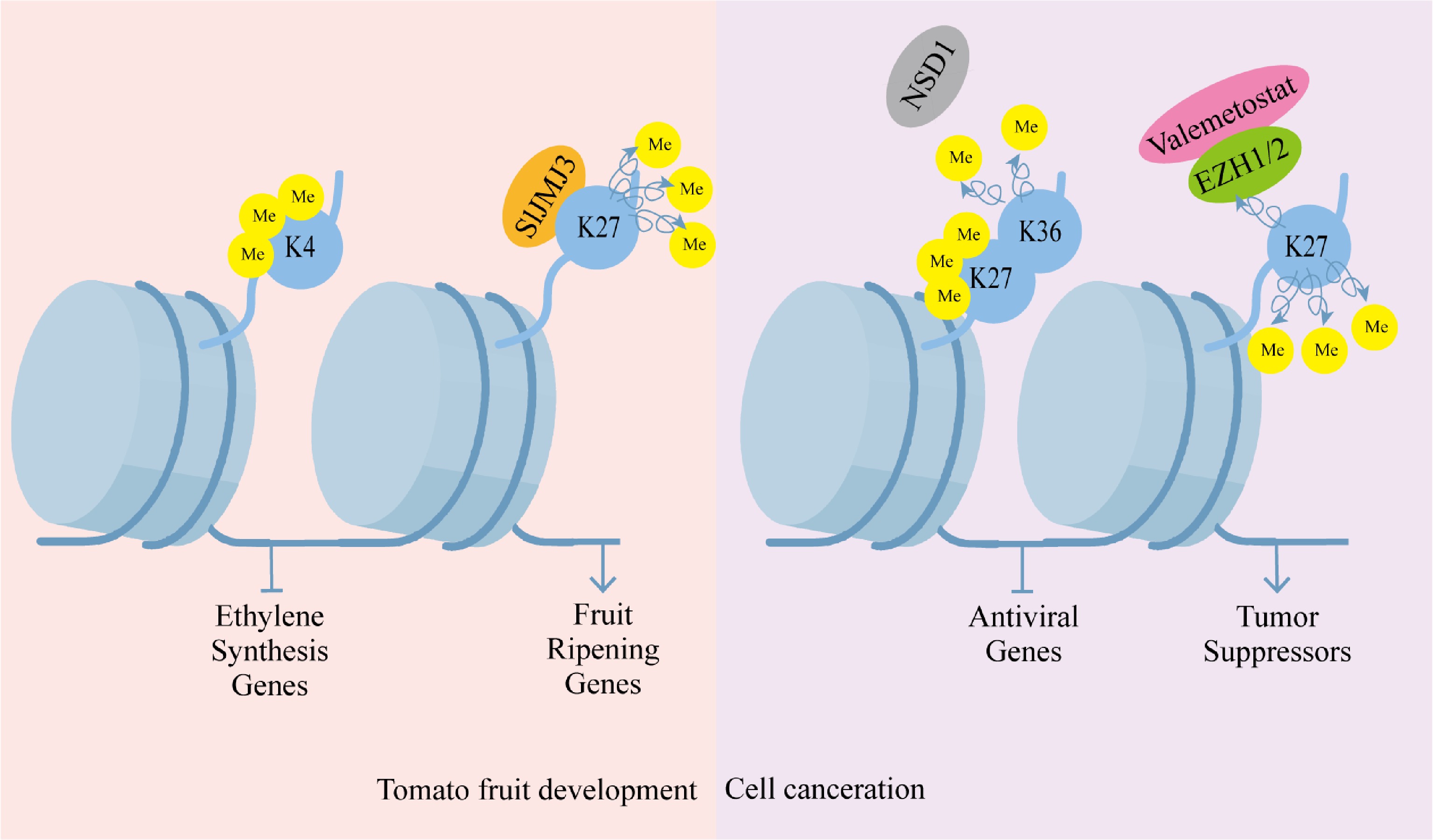

Histone methylation is a critical epigenetic mechanism coordinating plant developmental programs and stress responses. In rice, the RLB (RICE LATERAL BRANCH) protein directs lateral branch development through PRC2-mediated deposition of H3K27me3 marks at the OsCKX4 locus, demonstrating how specific histone modifications regulate morphological patterning[47]. Similarly, the methylation readers MRG1 and MRG2 integrate photoperiodic signals with chromatin states by recognizing H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 modifications at the FT locus (FLOWERING LOCUS T) promoter, thereby controlling flowering time[48]. During fruit development, dynamic shifts in H3K9ac and H3K4me3 correlate with ethylene synthesis gene repression, while the SlJMJ3 demethylase promotes ripening by erasing H3K27me3 from ripening-related genes. These developmental processes are further modulated by H3K36 methylation, which maintains transcriptional homeostasis by marking transcriptionally resistant genes (Fig. 2)[49], and by senescence-associated increases in H3K4me3 and H3K9me2 during leaf ageing[50].

Figure 2.

Histone methylation regulation pattern. Histone methylation regulation is crucial in plant development. Histone H3 lysine four trimethylation (H3K4me3) is linked to the silencing of ethylene biosynthesis genes during tomato fruit ripening, and the histone demethylase Jumonji C domain-containing protein three (SlJMJ3) facilitates ripening by deposing the ethylene biosynthesis-related genes of H3K27me3. It is also crucial in the progression of diseases in humans. Pathological progression of cancer is characterized by aberrant histone methylation in cancer cells, and dysregulated activities of histone methyltransferases are often linked to carcinogenic transformation. Silencing of antiviral genes is caused by the loss of H3K36me2, accompanied by a counterbalancing increase in H3K27me3. Valemetostat or pharmacological inhibition of the enhancer of zeste homologs EZH1/2 reinstates tumor suppressor gene functionality by inhibiting the repression of H3K27me3.

The plasticity of histone methylation is equally crucial for environmental adaptation. In Arabidopsis, H3K4 methyltransferases SDG25 and ATX1 sustain H3K4me3 marks during heat stress recovery, ensuring persistent expression of heat-responsive genes[51]. Thermal adaptation involves chromatin state modulation, with elevated H3K4me3 under high temperatures promoting open chromatin and gene activation[52]. Comparative epigenomic analyses reveal cultivar-specific methylation patterns: salt-tolerant rice maintains elevated levels of the activating histone modification H3K4me3 and reduced levels of the repressive histone modification H3K27me3 at stress-responsive loci (e.g., OsBZ8), whereas salt-sensitive rice varieties exhibit the opposite pattern[53]. Jasmonic acid signaling similarly intersects with histone modification through HDA6-mediated changes in H3K27me3 distribution, influencing secondary metabolism and stress response pathways[54]. The histone demethylase IBM1 is an example of direct environmental sensing, where it is triggered by light stress triggers to remove repressive H3K9 methylation from photoprotective genes, preventing anthocyanin overaccumulation[55].

These findings collectively position histone methylation as a dynamic interface between developmental programming and environmental perception, offering novel strategies for crop improvement through epigenetic engineering. Further study on the spatial-temporal specificity of such changes will be important for using the potential of these changes in agriculture.

-

Epigenetic regulation is a complex process that is not limited to DNA methylation and histone methylation, but also includes multiple histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) and non-coding RNAs, which interact in a complex manner to regulate gene expression and chromatin dynamics in plants and animals. Histone acetylation is one of the PTMs that deprotonate the positive charges in the lysine residues and provide a more relaxed chromatin structure, which promotes transcriptional activation and adaptation to environmental stress[56]. One example is histone acetyltransferases (HATs), which are necessary in plants to control the stress response and cell cycle, as well as transcription and DNA repair in animals[57].

Quick reversible histone phosphorylation rearrangement is associated with cell cycle management, DNA harm reaction, and expression regulation, forming dynamic histone marks that attract the recruitment of particularly impactful proteins[58]. This alteration allows a quick reaction to cellular signals. A delicate equilibrium between the activity of ubiquitin ligase and deubiquitinase regulates transcriptional activation and silencing, repair of damaged chromatin and DNA, as well as monoubiquitination of the histones H2A and H2B[59]. Sumoylation is another ubiquitin-like modification that plays a role in transcriptional repression and compaction of the chromatin and usually affects other epigenetic pathways[60].

The non-coding RNA (ncRNA) includes siRNAs, miRNAs, and lncRNAs, which are guides and scaffolds that organize the structure of the DNA methylations and histone modifications and control the stability of the genome, silencing of transposons, and expression of the genes[61]. In plants, ncRNAs have been identified as important in stress, whereas they control developmental timing and cell differentiation in animals[62]. These epigenetic processes interrelate and crosstalk to generate different, dynamic, and context-dependent chromatin states that are necessary during development, environmental adaptation, and the pathogenesis of diseases.

-

Histone methylation patterns are tightly regulated as one of the basic epigenetic processes that control cellular differentiation and tissue homeostasis. In the case of mammalian germ cells, ageing causes a significant reorganization of repressive marks: H3K9me3 reduces and H3K27me2/3 increases with age in tests on old mice[63]. These dynamics could be altered by nutritional inputs such as folic acid, which is shown by the increase of H3K4me3 at loci of spermatogenesis genes that promote sperm production[64]. Equally, H3K4 methylation keeps the mitochondria active and preserves cellular quality by controlling the dynamics of organelles in oocytes via transcriptional regulation[65]. This direction of development is highly spatiotemporally controlled, as seen in H3K36me2 deposition mediated by NSD1 to organize cortical layer specification during brain development[66]. Similarly, histone methylation has a role in craniofacial morphogenesis for the stability between activating (H3K4me3) and repressing (H3K9me3) marks regulated by Prdm3/16, and in cardiac regeneration, which requires the removal of H3K27me3 at proliferative genes by HMGA1[67].

Histone methylation plasticity is also involved in tissue repair mechanisms. Mechanical forces reshape the epidermal epigenome through EZH2-mediated H3K27me3 accumulation that suppresses YAP target genes and modulates stem cell proliferation[68]. In dental and intestinal stem cells, dynamic H3K4 and H3K27 methylation states guide lineage commitment, with H3K36me3 emerging as a critical regulator of cellular plasticity during regeneration[69]. All these findings emphasise the significance of histone methylation as a tool for integrating developmental signalling with environmental signalling and pathological stimulation so that cellular phenotyping mechanisms may be regulated. New opportunities for using epigenetic therapies in regenerative medicine, cancer, and inflammatory diseases are driven by the emerging value of these mechanisms. Future studies that establish cell-type-specific signatures of methylation will play a significant role in creating accurate epigenetic interventions.

-

A role of epigenetic changes is to maintain the initial level of Casein Kinase Two (CK2) and monitor changes in its residual levels when an external stimulus activates CK2 expression. CK2 is a serine/threonine protein kinase that is well conserved in eukaryotes and is involved in various cellular roles, including regulation of gene expression, chromatin structure, and DNA methylation patterns[70]. CK2 also contributes generally to the epigenetic surroundings through the regulation of enzyme activities that mediate DNA methylation and histone modification via phosphorylation, thereby influencing gene expression, chromatin dynamics, and cellular adaptation mechanisms, conserved in plants and animals. CK2 activity coincides with its role in controlling epigenetic status by post-translational modifications, not just of DNA[70]. DNA methylation and histone modification are key processes of epigenetics found in both plants and animals, regulating gene expression, transposon silencing, genome health, and chromatin dynamics. However, there are both conserved and lineage-specific characteristics. All organisms use DNMT1 to engineer maintenance methylation and DNMT3A/3B to engineer de novo establishment. However, plants employ MET1 (a homolog of DNMT1) to engineer maintenance methylation along with CMT3 and DRM1/2, as well as the additional RNA-directed epigenetic pathway, RdDM, to confer more flexibility targeting repeats and transposons[71]. Modifications of histone proteins, such as acetylation and methylation, are equally important in both domains of chromatin accessibility and transcriptional regulation. As an illustration, active gene transcription is associated with the presence of H3K4me3, whereas transcriptional repression involves H3K27me3, which is catalyzed by the Polycomb Repressive Complex two (PRC2) in plants and animals. However, animal cells contain PRC2 components (EZH2) while plants do not contain EZH2 and instead have functionally equivalent homologs in the form of CURLY LEAF, indicating that chromatin regulation has evolved independently in the eukaryotes[72]. In plants, histone methyltransferases can regulate the upkeep of DNA methylation, whereas in animals, histone modifications often work by drawing DNA methyltransferase complexes to a particular locus[73]. Epigenetic reprogramming is another feature that is conserved, even though the dynamics vary vastly within lineages. During germline specification and early embryogenesis in animals, genome-wide demethylation and histone remodeling are critical in restoring pluripotency and totipotency states[74].

These results demonstrate that, although the basic epigenetic patterns of DNA methylation and histone modification remain conserved between plants and animals, being descended from a particular lineage, the specificities of enzymatic repertoires, regulatory routes, and contexts of development impose unique gene regulation patterns and adaptability.

-

Epigenetic modification of DNA and histone is an evolutionary process that is preserved in plants and animals. It influences gene silencing, suppression of transposons, stabilization of the genome, chromatin establishment, and expression[71]. Environmental factors can also dictate DNA methylation in both kingdoms[75]. The makes differ: in mammals, the primary targets of methylation include CpG dinucleotides, whereas in plants, both CpG and CpHpG/CpHpH contexts are targets as well, and the pathway of methylation directed by RNA is probably exclusively used in regionally silenced chromatin in animals[71]. Similarly, plants and animals also depend on DNA methyltransferases to either set up or sustain methylation, but the enzymes used are different[76]. Both groups have histone modifications, including acetylation and methylation. The two groups demonstrate a mark of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3, although animals have access to the Polycomb protein EZH2, which is lacking in plants. The groups also differ in their response to histone variants and the regulation of modification[77]. In both systems, DNA modification and histone adjustments affect one another to sustain efficient epigenetic conditions, but the proteins and mechanisms of each crosstalk differ. Epigenetic reprogramming in both plants and animals involves the erasure and replenishment of marks across development.

-

DNA methylation and histone methylation play an important role in the regulation of gene expression. However, they do not function in isolation, but are interrelated and interact with each other, forming a complex and delicate epigenetic regulatory network.

-

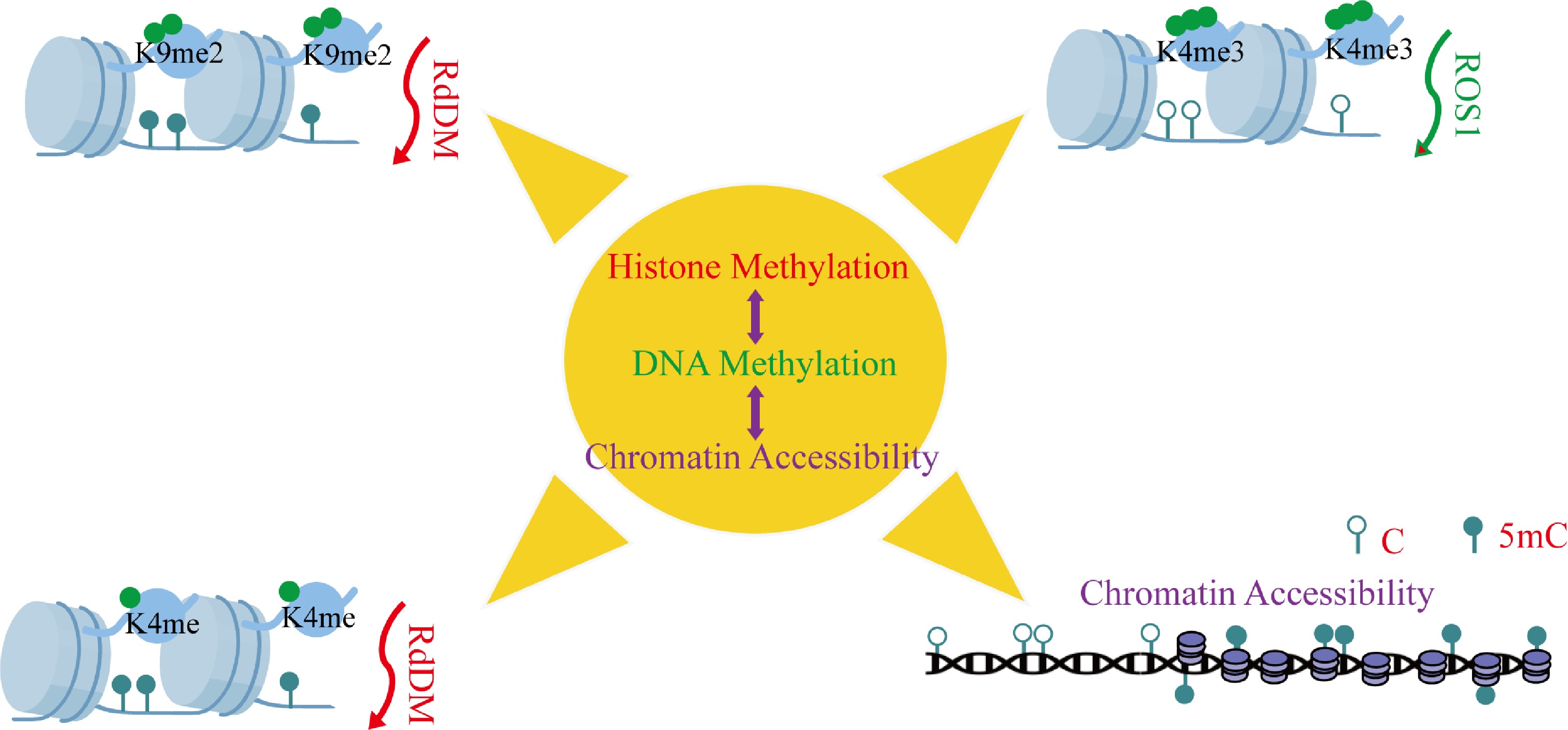

DNA methylation and histone modifications form an integrated epigenetic network that orchestrates plant development through sophisticated crosstalk mechanisms. During Arabidopsis embryogenesis, siRNA-guided asymmetric DNA methylation is spatially and temporally coordinated with H3K9me2 deposition, revealing developmentally programmed crosstalk between these epigenetic regulatory layers (Fig. 3)[78]. Similarly, the methyltransferase RDM15 recognizes H3K4me1-marked chromatin to recruit RNA polymerase V, establishing a feedback loop that fine-tunes locus-specific DNA methylation patterns and modulates transcriptional activity (Fig. 3)[79]. This coordination extends to cellular reprogramming events, as demonstrated in peach leaf callus formation, where concurrent DNA hypomethylation and H3K27me3 demethylation activate phytohormone pathways to induce pluripotency (Fig. 4)[80]. The functional redundancy of Arabidopsis Trithorax 1–5 (ATX1-5) underscores this integration, with their mutation phenocopying both DNA demethylation and RdDM pathway defects, revealing unexpected overlaps in these epigenetic regulatory networks[81]. A striking example of coordinated regulation occurs during tomato fruit ripening, where SlJMJ7 demethylase simultaneously erases H3K4me3 marks and inhibits DNA demethylase (SlDML2) activity to control ripening genes (Fig. 4) precisely[82]. DNA demethylation mediated by SlDML2 controls the accessibility of chromatin, which represses or activates the activity of critical ripening transcriptional factors (Fig. 3)[83]. These results demonstrate that DNA methylation and all other epigenetic modifications are a complex control nexus that governs the development and maturation of fruits. It is also worth noting that DNA methylation can be a handy molecular switch controlling developmental transitions in fruit ripening.

Figure 3.

Synergistic regulation between DNA methylation and histone modifications. This depicts the synergetic control between histone modifications and DNA methylation. These essential interactions are: (i) RdDM-mediated small RNA-dependent de novo DNA methylation, (ii) H3K9me2 deposition and H3K4me establishment, (iii) H3K4me3-mediated hiring of DNA demethylases, and (iv) enrichment of histone modifications by DNA methylation. Abbreviations: 5mC, 5-methylcytosine; C, cytosine.

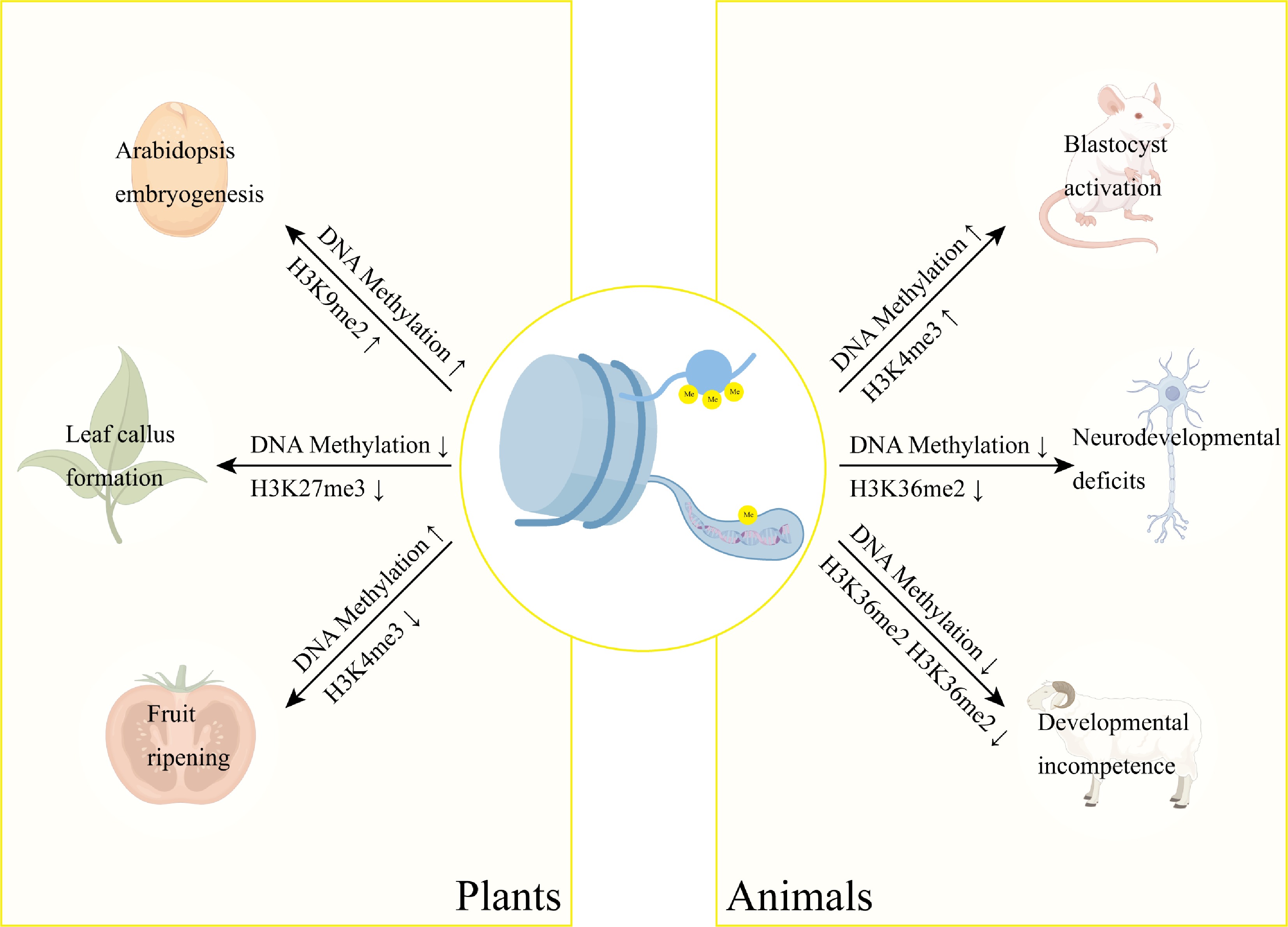

Figure 4.

Interplay between DNA methylation and histone methylation in developmental regulation. DNA methylation and histone methylation function synergistically in gene regulation. These epigenetic modifications form an integrated regulatory network controlling key developmental processes across species, including Arabidopsis embryogenesis, peach somatic embryogenesis, and tomato fruit ripening. Notably, their coordinated action is equally essential in mammalian systems, regulating mouse oocyte activation, neural development, and somatic cell reprogramming in cloned goats.

These modifications create network connections that form dynamic regulatory loops, simplifying gene expression. H3K4me3 DNA demethylases include ROS1, which forms a positive feedback loop to allow the target genes' transcriptional amplification to stabilize when there is a change in development[84]. This crosstalk is two-way in maize; the RdDM pathway does not merely control the expression of genes by the process of DNA methylation, but also their histone modification at the location of B1[85]. The mechanisms of this integration have been studied in the case of ROS1, which is the C-terminal domain of the protein involved in communication with histone H3 to identify the regions of the chromatin that are demethylated[86]. Another example of coordination is DNA methylation suppressing the formation of repressive methylation H4K20me3 to sustain rDNA transcription during stressful events[87].

These mechanisms converge at the responses of the environment through the multi-protein complexes, which change the two epigenetic marks simultaneously. SHH2 is a maize RdDM protein that identifies the H3K9me1 via its SAWADEE domain, through which the setting up of histone modification readers is connected with DNA methylation[88]. In Arabidopsis, thermos-morphogenesis mediates the APOLO-VIM1-LHP1 complex, which co-regulates auxin synthesis by modulating the dynamics of DNA methylation and the histone modification H3K27me3.[89]. One of the principles of epigenetics that has been determined is the communicative role of the chromatin structure, which is regulated by histone modifications and DNA methylation. Recent studies have given additional mechanistic understanding of the action of these changes concerning genomic stability and gene expression conditions, which have implications for adaptation and crop improvement in plant designs.

-

Two layers of epigenetics, DNA and histone methylation, regulate gene silence, chromatin structure, and genome stability. The transient reconfiguration of DNA methylation states alongside the redistribution of the location of H3K4me3 and H3K9me3 marks occurs during blastocyst activation, creating an epigenetic landscape regulating cell fate determination and establishing the successful implantation of the embryo (Fig. 4)[90]. This developmental reprogramming exemplifies the sophisticated crosstalk between epigenetic systems, further demonstrated in Neurospora crassa, where HP1 mediates the recruitment of DIM-2 methyltransferase to H3K9me3-enriched heterochromatin, establishing a self-reinforcing epigenetic cycle[91]. The reciprocity of these modifications is equally evident in plants, where the SRA domain of SUVH5 interprets DNA methylation signals to direct H3K9 methylation via its SET domain, maintaining transcriptional silencing through coordinated chromatin compaction[92].

The functional integration of these epigenetic systems extends to regulatory networks involving non-coding RNAs. microRNA-152-3p exemplifies this regulation, functioning as a molecular switch that inversely modulates SETDB1-dependent H3K9me3 deposition and DNMT1-mediated DNA methylation[93]. Similarly, in neuronal systems, NSD1-mediated H3K36 methylation patterns guide DNMT3A activity, with disruption of this axis recapitulating the neurodevelopmental deficits seen in DNMT3A disorder models[94]. Such epigenetic coordination proves particularly critical during reproductive development, as evidenced in cloned goat embryos with concurrent dysregulation of 5-methylcytosine, H3K4me3, and H3K9me3 during zygotic genome activation, aberrations that likely underlie their developmental incompetence (Fig. 4)[95]. The germline further illustrates this interplay, where the PWWP domain of DNMT3A interprets H3K36me2/3 marks to establish sex-specific methylation patterns while H3K4me3 counterbalances DNA methylation to regulate spermatogenic gene expression[96].

Pathological disruption of this epigenetic dialogue is seen across disease states. The H3.3G34R mutation destabilizes the H3K36me2-DNMT3A axis, redistributing DNA methylation from intergenic regions to CpG islands and driving neurodevelopmental collapse[97]. Adult T-cell leukemia also relies on the interaction between DNA methylation and H3K27me3, as the combination of DNMT and EZH2 inhibition is more effective[98]. Even a metabolic pathology such as diabetic retinopathy uses this mechanism, where Suv39H1-produced H3K9me3 scaffolds DNMT1 binding to the Rac1 promoter to form a pathogenic epigenetic circuit[99]. These data point to the therapeutic relevance of the interdependence between histone and DNA systems of methylation in a vast range of disease contexts.

-

The interrelation between DNA methylation and histone methylation is one of the most critical epigenetic regulatory axes; its dysregulation disrupts the organization of gene expression patterns, normal development, and disease pathogenesis. The interaction between these two systems of epigenetics is bidirectional: DNA methylation may cause the recruitment of a chromatin-modifying complex, capable of altering histone methylation patterns, and histone methylation patterns may recruit DNA methyltransferases to their genomic targets. The interdependence between DNA methylation and histone modifications contributes to regulating transcription programs that govern cell differentiation and tissue development. This interplay—encompassing their interdependence and interaction—further modulates the transcriptional regulation of these biological processes. It achieves a very high degree of spatiotemporal control of gene expression, directionally regulated, as compared to active demethylation of DNA in animals, which is generally a more widespread and less specific process for obtaining epigenetic and developmental reprogramming. It is also worth noting that their collective action creates strong epigenetic conditions that either modify or repress the expression of genes in a particular developmental situation, depending on environmental signaling. In addition to physiological processes, a deviant pattern of this epigenetic mark is associated with the etiology of diseases, particularly cancer. Malignant transformation is prone to take advantage of such an epigenetic interaction, and the two systems deregulate simultaneously, producing oncogenic patterns of gene expression. The combination of DNA and histone methylation creates an integrated platform of epigenetic axes involved in mediating development, and environmental and disease resilience in eukaryotes.

Their dynamic interactions, however, are too complex to study comprehensively when they happen, and we have no critical insight into how they are coordinated when complex biological events occur. Single-cell multi-omics methods and sophisticated live-cell imaging methods should be able to address these limitations by simultaneously monitoring these modification systems with spatial and time resolution. Three areas for future investigation are: (i) the creation of new tools to identify the transient intermediates in their interaction networks, (ii) the creation of more physiologically relevant model systems that reflect the complexity of epigenetic regulation in vivo, and (iii) the systematic mapping of the hierarchical relationships and stress-responsive dynamics of these interactions across different developmental and growth stages will not only shed light on key principles of epigenetic regulation, but also open new therapeutic avenues for diseases associated with epigenetic dysregulation—including those linked to agricultural breeding practices.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32270367 to QN) and the Office of Education of Anhui Province for Distinguished Young Scholars (Grant No. 2022AH020061 to QN).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: draft manuscript preparation: Liu X, Niu Q; literature review: Lang Z, Niu Q, Liu X, Nisa KU, Kong W; manuscript editing: Lang Z, Niu Q, Liu X, Nisa KU, Kong W. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Xinqin Liu, Khair Ul Nisa

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu X, Nisa KU, Kong W, Lang Z, Niu Q. 2025. DNA methylation and histone modifications: conserved, divergent, and synergistic epigenetic regulation across plants and animals. Epigenetics Insights 18: e015 doi: 10.48130/epi-0025-0014

DNA methylation and histone modifications: conserved, divergent, and synergistic epigenetic regulation across plants and animals

- Received: 12 July 2025

- Revised: 01 November 2025

- Accepted: 05 November 2025

- Published online: 17 December 2025

Abstract: DNA methylation and histone modifications are two fundamental epigenetic markers that play pivotal roles in regulating gene expression and maintaining genomic stability in both plant and animal kingdoms. These conserved epigenetic mechanisms are critical in mediating responses to various biotic and abiotic stresses, while simultaneously orchestrating developmental processes and other essential biological functions. This review explores the conserved and divergent regulatory mechanisms of DNA methylation and histone modifications in plants and animals, their synergistic roles in reproductive development, growth regulation, and stress adaptation, as well as the dynamic crosstalk between these epigenetic modifications. This review highlights emerging evidence of the cooperative integration of these epigenetic mechanisms within gene regulatory networks, offering new insights into how they shape phenotypic plasticity. By synthesizing current knowledge across model systems, this review advances the mechanistic understanding of the regulation while providing a conceptual framework for future research in epigenetic breeding, stress resilience engineering, and evolutionary developmental biology. These perspectives pave the way for epigenetics-driven strategies to enhance agricultural productivity and biomedical applications.

-

Key words:

- DNA methylation /

- Histone modification /

- Plants and animals /

- Epigenetic regulation