-

Male reproduction in plants is essential for successful seed setting[1]. In flowering plants, male reproductive development occurs in the stamen, comprising of the anther and the filament. The vascular filament connects the anther to the central floral axis and transports water and nutrients, while the anther produces the male gametes (pollen grains). Pollen grain development in model plant species such as Arabidopsis and rice is well understood and has common characteristics[2,3]. The initial round anther primordium comprises three germ layers: L1, L2 and L3. Division of L1 cells generates the epidermis and the stomium, and L3 cells develop into the connective tissue, vascular bundle, and circular cell cluster. L2 cells undergo mitotic divisions and differentiation to form four lobes in each anther. In each lobe, microsporocytes are surrounded by three somatic anther wall layers (endothecium, middle layer and tapetum) and the outer anther epidermis. Microsporocytes are originally encased in the tapetum-derived callose wall that is subsequently degraded by callose degrading enzyme secreted from the tapetum at the initiation of meiosis. During anther development, microsporocytes undergo meiosis to form tetrads containing microspores, which undergo a further two mitotic divisions to become pollen grains[2,4].

As the tapetum degrades through programmed cell death (PCD) during meiosis, it provides critical components for pollen development, including pollen wall formation and accumulation of intracellular starch and lipids[2−9]. Microspores concurrently form primexine that serves as a template for deposition and assembly of sporopollenin precursors. Ultimately, mature pollen grains form an elaborate, three-layered wall comprising the outer exine, the inner intine, and the pollen coat (tryphine), which protects pollen from environmental stress and also function in adhesion and hydration during male-female interaction[1,8−11].

The plant male reproduction process is highly sensitive to various environmental factors such as photoperiod, temperature and humidity, which is typically evidenced by remarkable changes in anther revealed by multiple omics data. An integrated transcriptomic and metabolomics study in anthers of a P/TGMS (Photoperiod-/Thermo-sensitive Genic Male Sterile) rice, found that 706 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in response to temperature changes are involved in metabolic pathways of sugars, lipids and phenylpropanoids; and that more starch, lipid and flavonoid accumulate in fertile anthers compared to sterile ones[12]. In addition, results from proteomic analysis in a TGMS (Thermo-sensitive Genic Male Sterile) line showed that 192 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) are involved in ubiquinone and other terpenoid quinone biosynthesis, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, and other metabolic pathways[13]. These revealed DEGs and DEPs suggest that specific genes can respond to temperature changes, transcriptionally and translationally, resulting in the accumulation of essential materials for anther fertility[12−17].

Another transcriptomic study showed that 11,726 DEGs, in response to long-day and short-day photoperiod, are involved in pathways including transport, carbohydrate and lipid metabolic processes, and signaling pathways, particularly phytohormone signaling[18]. Further WGCNA (Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis) results revealed four photoperiod-related modules[18] in which some characterized TGMS genes including TMS10 (Thermo-Sensitive Genic Male Sterile 10)[19], TMS10L (Thermo-Sensitive Genic Male Sterile 10 Like)[19] and UbL404 (Ubiquitin fusion ribosomal protein L404)[20−22] are interestingly enriched. In addition to these TGMS genes, two PGMS genes: CSA (Carbon Starved Anther)[23−26] and OsUgp1 (UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase1)[27], are identified as two hub genes with a high degree of connectivity and co-relationships with genes in photoperiod-related modules[18]. This result indicates that TGMS and PGMS phenotypes can therefore possess independent, but also common, regulatory mechanisms.

Better understanding of environmentally responsive male fertility in cereal plants is of immense benefit to facilitate rice breeding in an increasingly changeable and unpredictable climate[28]. Hybrid rice, with its significant yield advantage over inbred rice, demonstrates its simpler reproduction and breeding procedure when produced from two-line breeding systems, which demand reliable environment-sensitive male sterile lines. Many genes involved in environmental adaption of plant male reproduction have been characterized (Table 1), including not only P/TGMS and humidity-sensitive GMS (HGMS) genes, but also some reverse P/TGMS genes (fertile at higher temperatures or longer day lengths). These characterized genes not only provide genetic resource for new two-line hybrid systems and crop cultivars with stable seed-setting rate, but also facilitate the understanding of plant-environment interaction during male reproduction. Thus, we summarized the latest mechanisms of several representative P/TGMS genes that control male fertility under different environmental conditions through various mechanisms[19,22,29−32]. Additionally, we introduced the male fertility recovery mechanism in pollen wall defective mutants in order to better understand adaption of male reproductive development to the environment[33−38].

Table 1. Genes involved in environmental adaption of plant male reproduction.

Species Gene name Gene ID Gene product Type of

EGMSPathway Reference Arabidopsis ACOS5 At1g62940 acyl-CoA synthetase 5 P/TGMS Pollen exine formation [36,38] RVMS At4g10950 GDSL lipase P/TGMS Pollen nexine formation [36,38] CalS5 At2g13680 callose synthase 5 P/TGMS Pollen exine patterning [36,38] RPG1/SWEET8 At5g40260 SWEET8 TGMS Pollen nexine formation [34,35,38,

111,112]CYP703A2 At1g01280 cytochrome P450 703A2 P/TGMS Pollen exine formation [36,38] ABCG26 At3g13220 ATP-binding cassette transporter G26 TGMS Pollen exine formation [38] TMS1 At3g08970 HSP40 TGMS Growth of pollen tubes, unfolded protein response [113,114] NPU At3g51610 ATP-dependent helicase/deoxyribonuclease subunit B P/TGMS Pollen primexine

deposition[36] IRE1A IRE1B At2g17520 At5g24360 IRE TGMS Pollen coat formation, unfolded protein response [115] AtSec62 At3g20920 Translocation protein TGMS Protein translocation and

secretion[116] PEAMT At3g18000 S-adenosyl-l-methionine: phosphoethanolamine N-methyltransferase TGMS Signal transduction [117] AtPUB4 At2g23140 E3 ligase TGMS Protein degeneration [118] COI1 LOC9315901 F box protein TGMS Protein degeneration [119] ICE1 At3g26744 MYC-like bHLH

transcriptional activatorHGMS Anther dehiscence, transcriptional regulation [120] MYB33 MYB65 At5g06100 At3g11440 R2R3 MYB transcription

factorTGMS Tapetum PCD, transcriptional regulation [62] CER1 At1g02205 Acyl-CoA synthetase HGMS Pollen coat function [82] CER3 At5g57800 Acyl-CoA synthetase HGMS Pollen coat function [84] CER6/CUT1 At1g68530 Acyl-CoA synthetase HGMS Pollen coat function [89] CER8, LACS4 At2g47240, At4g23850 Acyl-CoA synthetase HGMS Pollen coat function [90] FKP At4g11820 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A Synthase HGMS Pollen coat function [121] Rice UGP1 Os09g0553200 UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase1 TGMS RNA processing [27] TMS5 Os02g0214300 RNase ZS1 TGMS RNA processing [22] TMS10 -TMS10L Os02g0283800-LOC_Os03g49620 LRR-RLK TGMS Signaling transduction [19] TMS9-1/OSMS1 Os09g0449000 PHD finger protein TGMS Protein location and transcriptional regulation [63] AGO1d Os06g0729300 Argonaute protein TGMS PhasiRNAs production [53,54] HMS1-HMS1I Os03g0220100-Os01g0150000 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase 6 very-long-chain enoyl-CoA reductase HGMS Pollen coat function [32] OSOSC12 /OSPTS1 Os08g0223900 Bicyclic triterpene synthase HGMS Pollen coat function [81] OsCER1/ OsGL1-4 Os02g0621300 Acyl-CoA synthetase HGMS Pollen coat function [91] CSA Os01g0274800 R2R3 MYB transcription

factorrPGMS Sugar distribution, transcriptional regulation [23,24] CSA2 Os05g049060 R2R3 MYB transcription

factorPGMS Sugar distribution, transcriptional regulation [26] PMS1 AK242308 lncRNA PGMS lncRNA regulation [29] P/TMS12-1 (PMS3) Os12g0545900 lncRNA, smR5864 P/TGMS lncRNA regulation and smRNA regulation [51,52] OsPDCD5 AY327105 Programmed cell death 5 protein PGMS Tapetum PCD [122] OSMYOXIB Os02g0816900 Myosin XI B PGMS Nutrition transport, protein location [123] OsNP1/OsTMS18 Os10g0524500 Glucose–methanol–choline oxidoreductase TGMS Pollen exine formation [97] ORMDL/tms2 Os07g0452500 Orosomucoid TGMS Sphingolipid homeostasis,PCD [124] OsOAT LOC_Os03g44150 Ornithine δ-aminotransferase rTGMS Cold tolerance [125] HSP60-3B LOC_Os10g32550 Heat Shock Protein60-3B TGMS Starch granule biogenesis, reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels [126] OsTMS15 LOC_Os01g68870 LRR-RLK TGMS Tapetum development [44] OsAL5 LOC_Os05g34640 Alfin like TGMS TMS5 expression [60] Maize TMS5 LOC100285786 RNase ZS1 TGMS mRNA decay [127] DCL5 LOC103643440 Dicer-like 5 TGMS PhasiRNAs production [56] MAGO1, MAGO2 Zm00001d007786, Zm00001d013063 MALE-ASSOCIATED ARGONAUTE TGMS Pre-meiotic phasiRNA pathways [55] INVAN6 Zm00001d015094 Alkaline/neutral invertase TGMS Sugar accumulation, metabolism, and signaling [128] Brassica

napusBnChimera BnRfb naA7.mtHSP70-1-like rTGMS Fatty acid synthesis [99] Barley HvMS1 LOC123121697 PHD finger protein rTGMS Transcriptional regulation [129] Soybean MS3 GLYMA_02G107600 PHD finger protein rPGMS Transcriptional regulation [64] EGMS, environment-sensitive genic male sterility; PGMS, photoperiod-sensitive genic male sterility; rPGMS, reverse photoperiod-sensitive genic male sterility; TGMS, thermo-sensitive genic male sterility; rTGMS, reverse thermo-sensitive genic male sterility; HGMS, humidity-sensitive genic male sterility. -

Receptor-like kinases (RLK) are a large family of membrane proteins that typically contain at least three domains to transduce extracellular signals into cellular responses. The extracellular domain plays a vital role in sensing ligand molecules (secreted peptides or plant hormones); the transmembrane domain directs RLKs to the correct cellular location; while the cellular kinase domain initiates the intracellular signal by phosphorylating a substrate. Although RLK-mediated signaling pathways have been reported in plant male reproductive development[39,40], few of them are involved in response to environment changes.

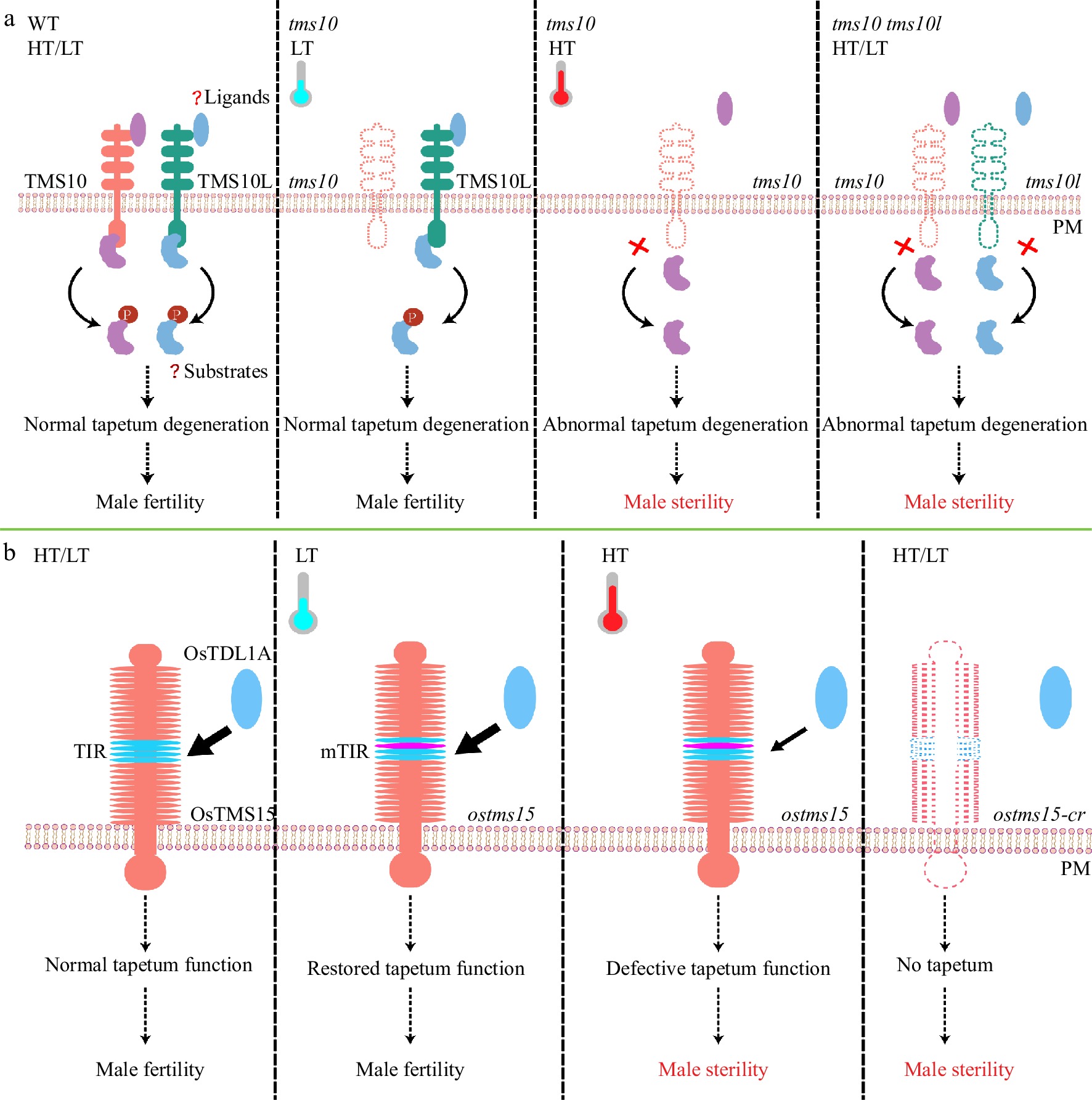

Our previous work reported that two leucine-rich repeat (LRR)-RLKs, TMS10 and TMS10L, redundantly regulate tapetum degeneration and pollen development in response to temperature changes[19]; TMS10 alone mediates male reproduction at HT, while together with TMS10L, TMS10 mediates male reproduction at LT[19] (Fig. 1a). However, how TMS10 and TMS10L function together to control male reproduction at LT remains unknown. Generally, LRR-RLKs form heterodimers between a RLK with short LRRs and a RLK with longer LRRs[39−41], such as CLV1(CLAVATA 1) and CIKs (CLAVATA3 INSENSITIVE RECEPTOR KINASEs)[42]. As TMS10 and TMS10L have only four LRRs, it is plausible that there are unknown RLKs with longer LRRs that could recruit TMS10 and/or TMS10L to form heterodimeric complexes, phosphorylating and magnifying the signals. In addition, the extracellular ligands activating TMS10 and TMS10L remain unknown, as do the downstream key transcription factors (TFs) activated by their signaling pathways. Future efforts to reveal these answers will provide novel insights into how plants buffer adverse temperature effects to sustain male reproduction.

Figure 1.

TMS10/TMS10L, OsTMS5 buffer temperature changes to maintain rice male fertility. (a) In WT, TMS10 and TMS10L relay extracellular signals via substrate phosphorylation (P) to safeguard male fertility at high and low temperatures (HT/LT). In the tms10 mutant at HT, TMS10L is poorly expressed and signals cannot be transduced, resulting in abnormal tapetum degradation and male sterility. At LT, however, TMS10L can restore signal transduction to recover male fertility of the tms10 mutant. The tms10 tms10l double mutant is completely sterile at all temperatures. Red crosses indicate loss of function. (b) In WT, OsTMS15, interacting with its ligand OsTDL1A, initiates tapetum development for pollen formation at HT or LT. In the ostms15 mutant with an amino acid substitution in its TIR motif, the interaction between mTIR and OsTDL1A is reduced, leading to defective tapetum function and male sterility at HT. LT can enhance the interaction and restore tapetum function and male fertility of ostms15 mutant. The knockout line ostms15-cr has no tapetum and is completely sterile at both HT and LT conditions. Os, Oryza sativa (rice).

A recent study found that another LRR-RLK protein, OsTMS15, previously known as MSP1[43], is important for tapetum initiation and pollen development in response to temperature changes; and ostms15 is male sterile under HT and fertile under LT. Its sterility under HT is more stable than that of tms5[22], with considerable value for rice breeding[44]. The recovered interaction between mOsTMS15 and its ligand OsTDL1A and slow development under LT compensate for the defective tapetum initiation, further restoring ostms15 fertility (Fig. 1b). Since the TIR motif in the LRR region of OsTMS15/MSP1 interacts with its ligands[43], authors created a number of TGMS lines targeting this region with different base substitutions, facilitating not only mechanistic investigations but also breeding of resilient rice crops.

-

ncRNAs, a family of regulatory RNAs, can recognize specific nucleic sequence to regulate plant growth, development, and environmental responses[45]. They are broadly divided into two categories: long ncRNAs (lncRNAs, > 200 nt), and small ncRNAs (smRNAs, 18–30 nt) that include microRNAs (miRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs)[45,46]. Some components of these ncRNA pathways are sensitive to temperature and photoperiods, enabling plants to adapt to unwelcome temperatures or photoperiods during male production. Transcriptomic and genetic studies have revealed that many ncRNAs are involved in plant male reproduction[47], some of them are sensitive to temperature and photoperiod, which has been reviewed elsewhere[48−50].

These reported RNA processing molecules include one lncRNA LDMAR (Long-Day specific Male-fertility–Associated RNA) and one siRNA Psi-LDMAR that is involved in the methylation of the promoter of LDMAR, both are identified in the rice PGMS mutant Nongken58S[30,51]. The PMS3 locus encoding LDMAR, known as P/TMS12-1 in indica Peiai64S (derived from Nongken58S), also produces smR5864. Interestingly, it confers PGMS in japonica Nongken58S but TGMS in indica Peiai64S[52], however, the exact mechanisms underlying its effect on PGMS and TGMS in a subspecies-dependent manner remain unknown. Another lncRNA, PMS1T, identified also in Nongken58S is responsible for the production of 21nt phasiRNAs[29]. Other components in the phasiRNA pathway that are associated with T/PGMS are rice AGO1d (ARGONAUTEO1d)[53,54], maize MAGO1 and MAGO2[55], and maize DCL5 (DICER-LIKE5)[56] (Table 1).

The above mentioned results indicate that ncRNAs are important for plant responses to thermal/photoperiodical cues and that environmental factors can interact with both genetic and epigenetic elements to regulate plant male reproduction, albeit the fact that the potential target gene or genes of ncRNAs have not been fully identified.

-

RNase Z, the endoribonuclease belonging to the metallo-beta-lactamase family, has been found in all kingdoms of life. Two different forms of RNase Z are present in eukaryotes, the short- and long- form were called as RNase ZS and RNase ZL, respectively; whereas prokaryotes only have RNase ZS. Beyond tRNA maturation, RNase Z are also involved in the maturation of mRNAs that contain tRNA-like structures known as 't-elements'[57−59].

Rice TMS5 is the best characterized RNase ZS1 that associates with TGMS (Table 1); it regulates the mRNA abundance of its substrate UbL40 (Ubiquitin-60S ribosomal protein L40) that are involved in the ubiquitin pathway, in a temperature-dependent manner[22]. Further studies have revealed the regulatory aspects of TMS5 expression, providing new options for the development of novel TGMS rice lines. OsbHLH138 directly binds to the core region in the promoter of TMS5 and activates its expression[21]. Nevertheless, function of OsbHLH138 in male reproduction adapting to changing temperature remains to be fully elucidated. In contrast, OsAL5 (OsAlfin Like 5) directly binds to the 'GTGGAG' element in the promoter of TMS5 and repress its expression; consequently, OsAL5 overexpression plants are male fertile at LT but male sterile at HT[60]. In addition, GATA10 directly binds to the promoter of UbL40 and activates its expression, regulating fertility conversion[20]. These results suggest that the TMS5-UbL40 molecular module represents another important male fertility regulatory mechanism responding to changing temperatures. Identification of additional upstream regulatory genes will advance understanding of this genetic base to facilitate the development of novel TGMS germplasms.

-

Transcription factors play a key role in mediating anther and pollen development in response to environmental cues[2,4,9,61]. Among them, two pairs of MYB and PHD (plant homeodomain) finger proteins play roles in plant male production in a temperature/photoperiod-dependent manner[24,26,62−64]. It is necessary to summarize and update the transcriptional regulation of P/TGMS briefly reviewed previously[48−50].

CSA, CSA2 and PGMS

-

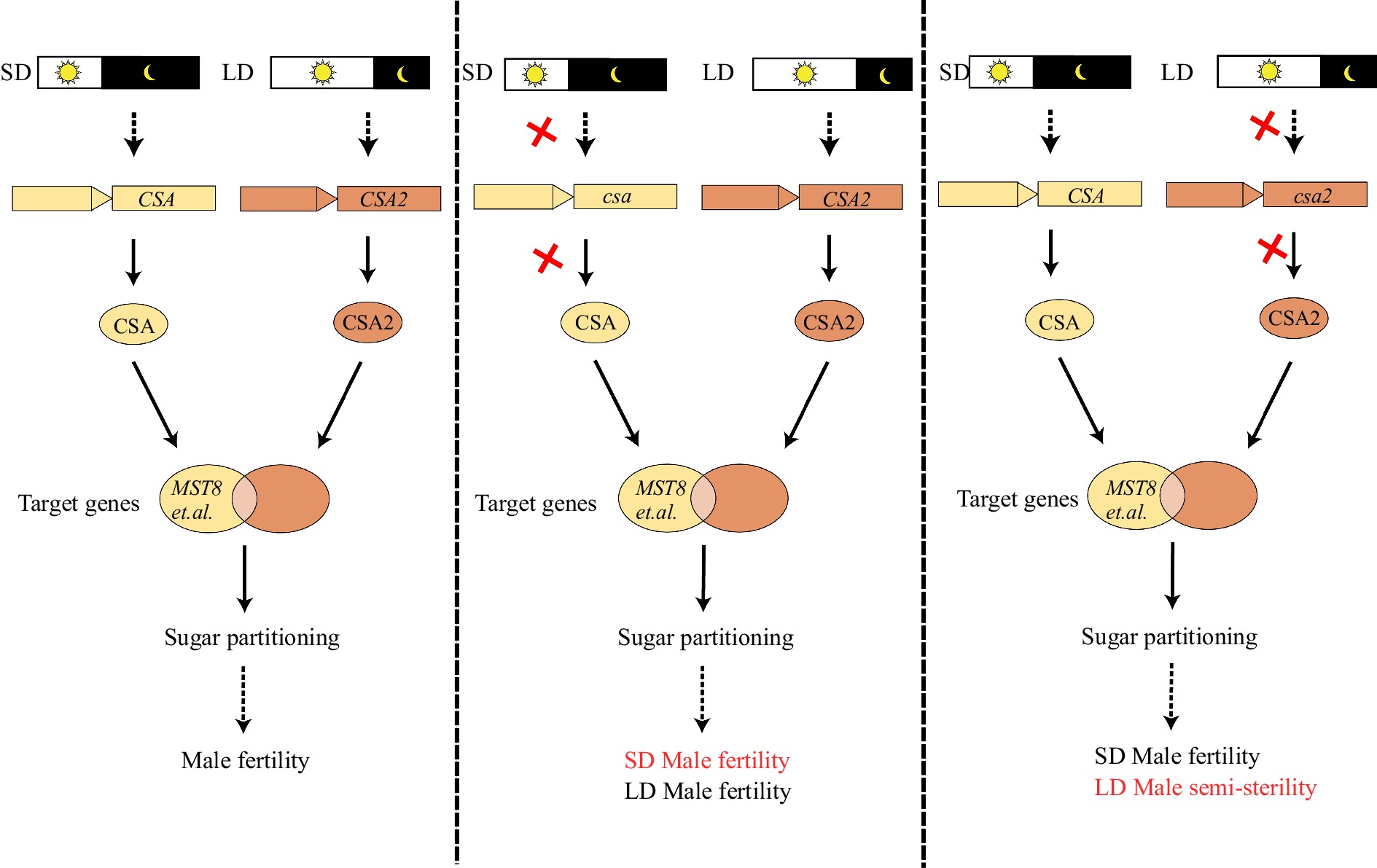

In rice, two R2R3-MYB TFs — CSA and its homolog CSA2 — are involved in male reproduction in response to photoperiod. CSA was first reported to be involved in PGMS in rice 10 years ago[24]; csa mutant is male fertile under LD conditions (13.5−14 h) and male sterile under SD conditions (11.5−12 h). Two years ago, CSA2 was also found to be involved in PGMS in rice[26]; the csa2 mutant shows the reverse response, being male fertile under SD conditions and semi-sterile under LD conditions. Furthermore, the csa csa2 double mutant displays an additive phenotype, being male sterile under SD conditions and semi-sterile under LD conditions[26]. Interestingly, CSA and CSA2 are preferentially expressed under SD and LD conditions, respectively, and both mutants exhibit altered sugar metabolism and transport pathways, indicating that CSA and CSA2 regulate male fertility via modulating sugar participating from the source tissue to sink tissue in response to different photoperiods.

Notably, differential expression of CSA and CAS2 in response to photoperiod is driven by their promoters, as CSA2 expressed from the CSA promoter restores csa fertility, while CSA expressed from the CSA2 promoter does not[26]. Transcriptome analysis found that these two TFs control adaption of plant male reproduction to photoperiod by regulating expression of both conserved and different downstream genes involved in sugar metabolism and transport[25,26]. Under SD conditions, CSA expression is highly induced to regulate downstream genes including MST8 (Monosaccharide Transporter 8), and to promote sugar partitioning to anthers[23,24]; under LD conditions, CSA2 plays a similar but weaker role[18,23−26] (Fig. 2). Our recent studies indicated that under SD conditions, CSA influences male reproduction via acting on a series of genes directly or indirectly associated with sugar partitioning and cell wall development[25], and that under LD conditions, CSA homologs, including CSA2, exert similar functions but with both common and distinct target genes[26]. Currently, it is still challenging to establish the specific regulatory relationships between CSA and CSA2, so are their downstream genes. Mining both upstream regulatory and downstream target genes of CSA and CSA2 would benefit efforts to elucidate PGMS mechanisms and uncover new PGMS genes. In addition, while promoters clearly play a key role in photoperiod response, other regulatory mechanisms and target genes involving in the adaptation to photoperiod remain to be explored.

Figure 2.

CSA and CSA2 are a pair of R2R3 MYB transcription factors in rice mediating male fertility adaptation to photoperiod. CSA is a key regulator under short-day (SD) conditions while CSA2 a major regulator under long-day (LD) conditions, both influencing sugar partitioning to the anther. In the csa mutant under SD, downstream target genes, including MST8, are not activated, leading to defective sugar partitioning and male sterility; under LD conditions, CSA2 can restore fertility of the csa mutant. In the csa2 mutant under LD, the loss of CSA2 function reduces activation of downstream target genes, leading to male semi-sterility; while CSA works under SD to restore male fertility. Red crosses indicate loss of function.

MYB33, MYB65 and TGMS

-

In Arabidopsis, MYB33 and MYB65, are miR159-regulated genes that redundantly facilitate anther development in response to temperature and light intensity changes. Neither myb33 nor myb65 mutant shows phenotypes, while myb33 myb65 double mutant is male sterile under low light intensity (LLI, ~80 μmol·m−2·s−1) and HT (21 °C), which can be restored by either high light intensity (HLI, 330 μmol·m−2·s−1) or LT (16 °C)[62]. In rice, GAMYB, their orthologue gene, acts upstream of TDR (Tapetum Degeneration Retardation), in parallel with UDT1 (Undeveloped Tapetum 1), to regulate rice early anther development, which is conserved also in Arabidopsis. However, the mutant of rice GAMYB is male sterile, which is different from myb33 myb65[65]. While the miR159 target sequence restricts the expression of MYB33 in the anther, MYB33 and MYB65 can be induced by gibberellins (GAs) in seeds for nutrient secretion and the progression of PCD in the aleurone during germination[66,67]. Whether the fertility conversion of myb33 myb65 is related to the similar process in tapetum remains unknown.

Since LT and HLI can restore the fertility of myb33 myb65 double mutant with increased soluble sugar levels in plants[62], and both CSA and CSA2 control fertility-sterility conversion via modulating sugar participating[25,26], it will be interesting to explore whether these regulators act via common downstream genes involving in sugar metabolism and transport or whether myb33 myb65, csa and csa2 can be rescued by a common mechanism.

PHD finger proteins and P/TGMS

-

PHD (plant homeodomain) finger proteins are TFs with important roles in plant male reproduction[68,69]. These TFs contain a PHD domain, and some also have LXXLL motifs (L, leucine; X, any amino acid) implicated in protein–protein interactions mediating transcriptional activation/repression and subcellular localization[69,70].

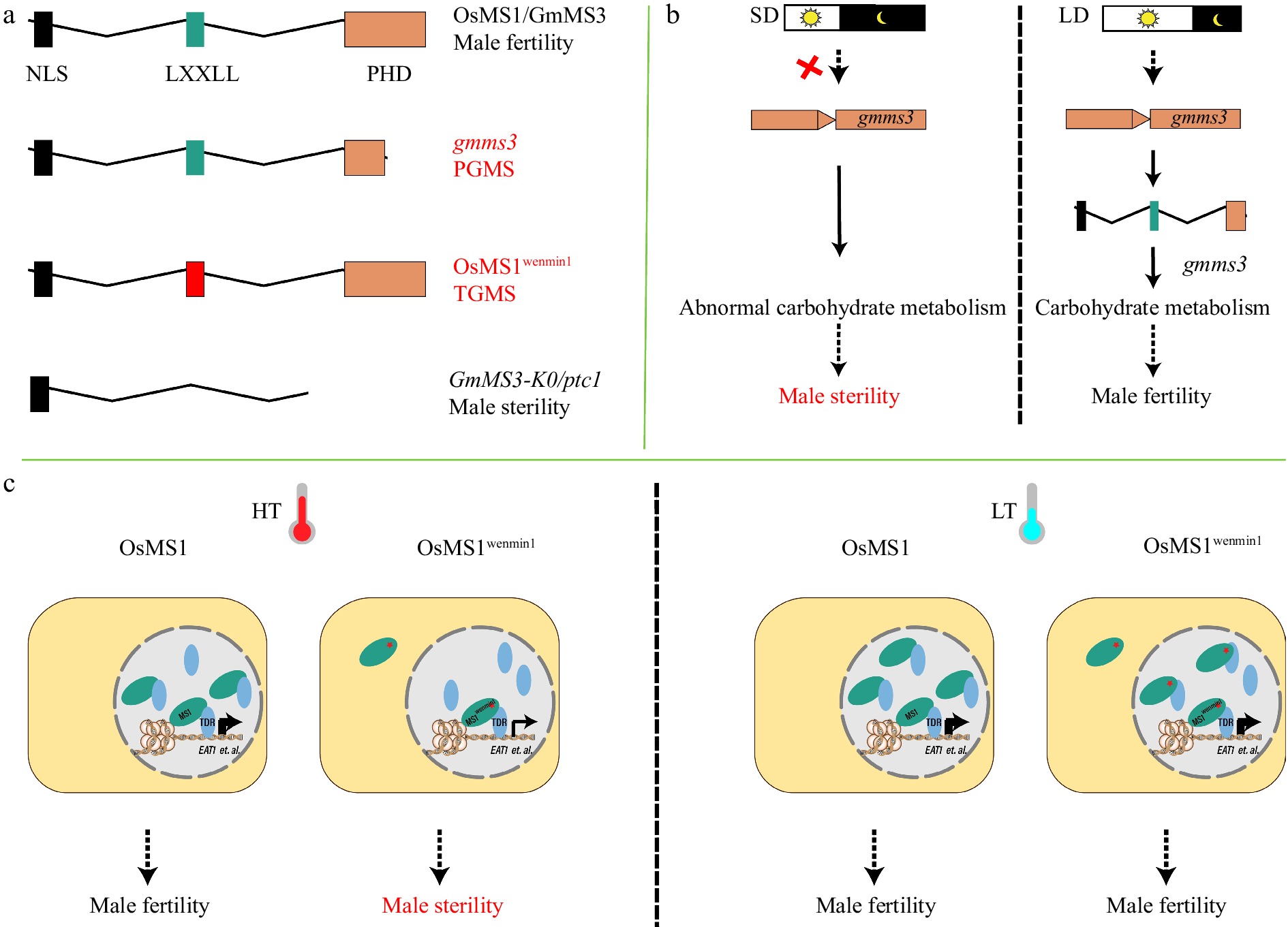

A recent study in rice found that the allelic mutation in the LXXLL motif of a PHD finger protein MS1 (Male Sterile 1), MS1wenmin1, confers TGMS. Ambient temperature regulates the abundance of MS1 and MS1wenmin1, and HT (> 27 °C) leads to more reduction of MS1wenmin1 than MS1 in the nuclei, resulting in male sterility[63]. Furthermore, both MS1 and MS1wenmin1 interact with TDR, enhancing the binding of TDR to the promoter of EAT1(ETERNAL TAPETUM 1) and activate EAT1 expression, in a temperature-dependent manner[63,71−74]. Thus, MS1 controls fertility-sterility conversion in response to temperature fluctuation via changing its nucleus localization and abundance[63,75] (Fig. 3a, c). However, not all allelic mutations in rice MS1 are associated with TGMS. For example, two allelic mutants of MS1 in rice, ptc1 and osms1, lacking the PHD domain and the LXXLL motif, are completely male sterile independent of temperature or photoperiod conditions[75,76]. So are mutants of MS1 orthologs in Arabidopsis, barley and maize, with ms1 proteins lacking PHD or additional domains[77−80].

Figure 3.

PHD finger proteins OsMS1 and GmMS3 affect temperature- or photoperiod-sensitive adaption of plant male reproduction in rice and soybean, respectively. (a) Schematic showing domains of plant homeodomain (PHD) finger proteins. Truncation of PHD in gmms3 leads to PGMS in soybean. The L301P substitution in the OsMS1wenmin1 LXXLL (L, leucine; X, any amino acid) motif leads to TGMS in rice. Deletion of the LXXLL and PHD domains in OsMS1/GmMS3 leads to complete male sterility. (b) Short-day (SD) conditions do not induce the expression of gmms3, leading to abnormal carbohydrate metabolism in anthers and male sterility. Long-day (LD) conditions is sufficient to activate gmms3 and restore male fertility. Red crosses indicate loss of function. (c) At high temperature (HT), OsMS1wenmin1 is expressed at low levels and distributed across both cytoplasm and nucleus, so nuclear concentration is insufficient to activate target genes, e.g., EAT1, leading to male sterility. At low temperature (LT), OsMS1wenmin1 is expressed at higher levels and concentrated appropriately in the nucleus to restore male fertility. Os, Oryza sativa (rice); Gm, Glycine max (soybean); NLS, nuclear localization signal.

Notably, a mutation of the soybean MS1 ortholog, ms3, confers PGMS, being male sterile under SD conditions (< 13.5 h) but fertile under LD conditions (> 15.75 h). The ms3 mutation occurs in the PHD domain, resulting in its partial deletion. Although comparative transcriptomic analysis reveals differential expression of genes related to carbohydrate metabolic process and glycosyltransferase activity between WT and ms3 under both SD conditions and LD conditions[64], the mechanism underlying the control of MS3-mediated PGMS remains largely unknown (Fig. 3a, b). In contrast, the full deletion of the PHD domain in MS3, causes temperature- or photoperiod- independent complete male sterility[64]. Therefore, both the LXXLL motif and PHD domain in PHD transcription factors are important for environmental sensitive male reproduction, as both rice MS1wenmin1 and soybean ms3 proteins retain partial function under permissive conditions[63,64,75]. However, how these domains function in the response to P/TGMS and how to use them for generating new P/TGMS lines warrants future investigations. Generating weak allele in these domains of MS1 and their orthologues in crop plants will give rise to useful TGMS germplasms for crop breeding as observed in ostms15[44] and MS1wenmin1[63].

-

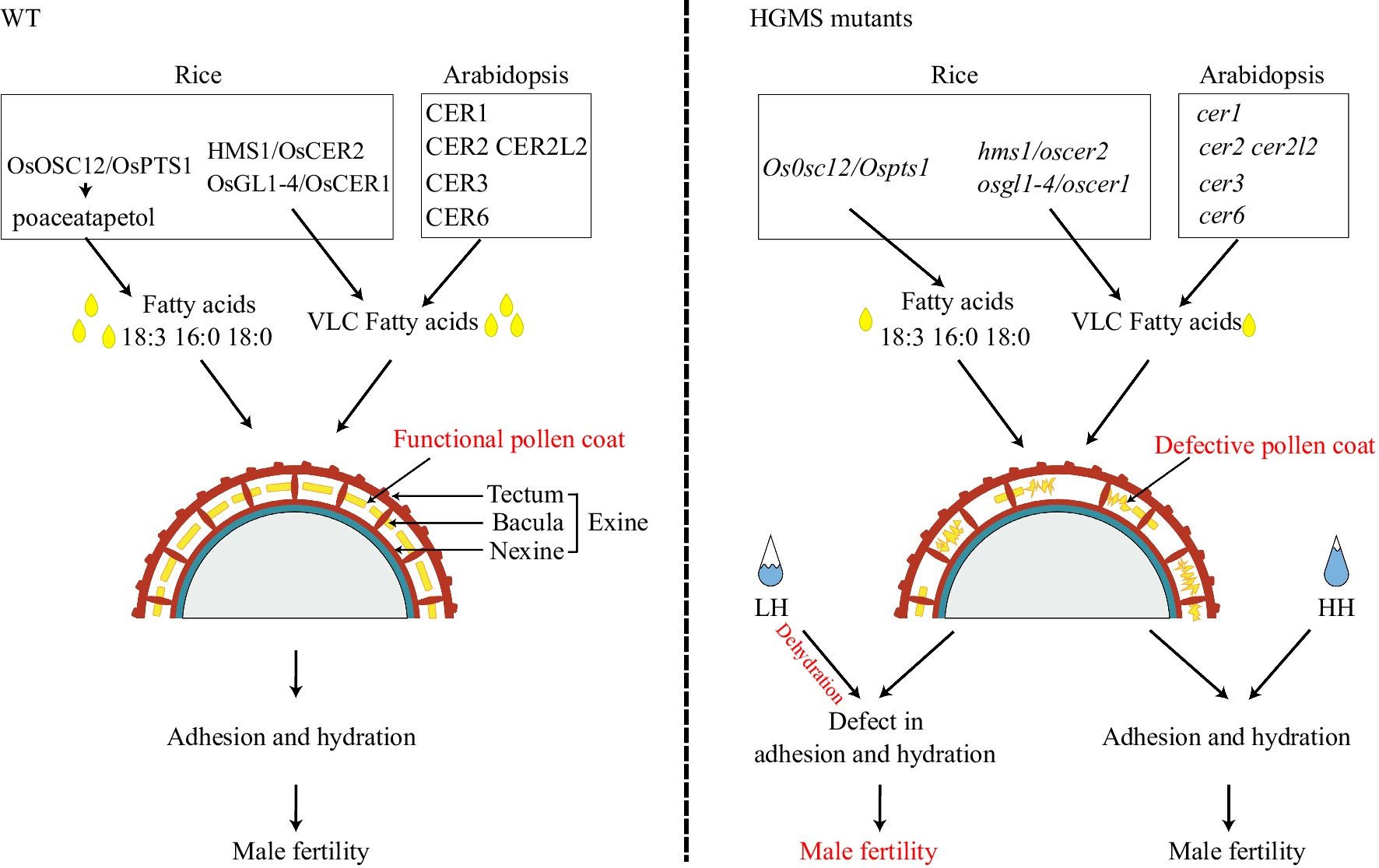

The tapetum provides materials for pollen development and maturation. After degeneration, tapetal lipid and protein remnants are positioned in exine cavities to form the pollen coat, also called the tryphine and pollenkitt, which is essential for communication between male and female organs, facilitates pollination and fertilization, and has recently been shown to play a role in adaptation to humidity.

In rice, the first reported HGMS mutant was ososc12[81]. OsOSC12/OsPTS1 encodes a bicyclic triterpene synthase, catalyzing production of the bicyclic triterpene poaceatapetol that assists deposition of long-chain fatty acids in the pollen coat through esterification. The ososc12 mutant pollen coat has reduced levels of long-chain fatty acids, sterols, and several triterpene esters, and increased levels of three major phytosterols, which leads to unsuccessful adhesion and hydration, i.e., male sterility, at low humidity conditions (LH, relative humidity [RH] < 60%). Fertility is restored at high humidity (HH, RH > 80%), clearly demonstrating that pollen coat is important for pollen adhesion and hydration at LH conditions[81].

In Arabidopsis, CER (eceriferum; Latin, 'without wax') genes play an important role in forming pollen coat by mediating very-long-chain (VLC) fatty acid biosynthesis. Mutations in many CER genes confer HGMS, being male sterile under dry conditions, but fertile at HH (RH > 90%). CER1 belongs to the fatty acid hydroxylase superfamily, which promotes the conversion of stem wax C30 aldehydes to C29 alkanes. The cer1 mutant has a defective pollen coat and is male sterile at LH (30% < RH < 40%)[82]. CER2 and CER2L2 are BAHD acyltransferases required for VLC fatty acid synthesis, and the cer2 cer2l2 double mutant is HGMS. CER2 and CER2L2 interact with CER6 (3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase) in the endothecium to modulate biosynthesis of VLC fatty acid (> 28 °C) in pollen coat[83]. CER3, another fatty acid hydroxylase, reduces VLC acyl-CoA to aldehydes, which are converted into VLC alkanes by CER1. Both the cer3 and cer6 mutants are male sterile in dry conditions (RH 50–70%), restored at HH[83−89]. In addition, CER8 and LACS4 are long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases (LACSs); the cer8 lacs4 double mutant is HGMS due to significant reductions of lipids in the pollen coat[90].

In rice, OsGL1-4/OsCER1 is the ortholog of Arabidopsis CER1 and the osgl1-4/oscer1 mutant is HGMS[91−93]. Pollens of osgl1-4 mutant are viable, but display defective hydration under normal conditions (30%−60% RH), restored at high humidity (RH > 80%). OsGL1-4/OsCER1 knockout likely affects VLC alkane metabolism and alters the lipid composition of pollen coat, causing defective pollen adhesion, hydration, and germination[91−93]. HMS1/OsCER2 encodes a 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase that catalyzes biosynthesis of the C26 and C28 VLC fatty acids. The pollen coat of the HGMS hms1 mutant contains reduced levels of VLC fatty acids, which disrupts pollen water retention[32,94]. Notably, seed-setting of hms1 mutants increase from 0% to 72% when RH increases from 45% to 75%[32,94].

Thus far, characterized genes associated with HGMS are involved in wax production or deposition, particularly VLC fatty acids[32,81,91−93,95,96] (Fig. 4). Mutation of these genes compromises pollen coat composition, with adverse effects on pollen hydration, leading to male sterility under low humidity conditions. Exploring new components and causal genes in pollen coat metabolism will facilitate discovery and identification of HGMS regulatory elements to prepare two-line hybrid system with excellent adaptations to drought.

Figure 4.

Pollen coat composition affects fertility at low humidity in rice and Arabidopsis OsOCS12/OsPTS1 influences long-chain fatty acid transport, and OSGL1-4/OsCER1, HMS1/OsCER2, and AtCER1, AtCER2, AtCER2L2, AtCER3, AtCER6 play roles in VLC fatty acid biosynthesis. Mutation in these genes (singly or in pairs) compromises pollen coat composition to reduce adhesion and hydration under low humidity (LH). At, Arabidopsis thaliana; HH, high humidity; VLC, very long chain.

-

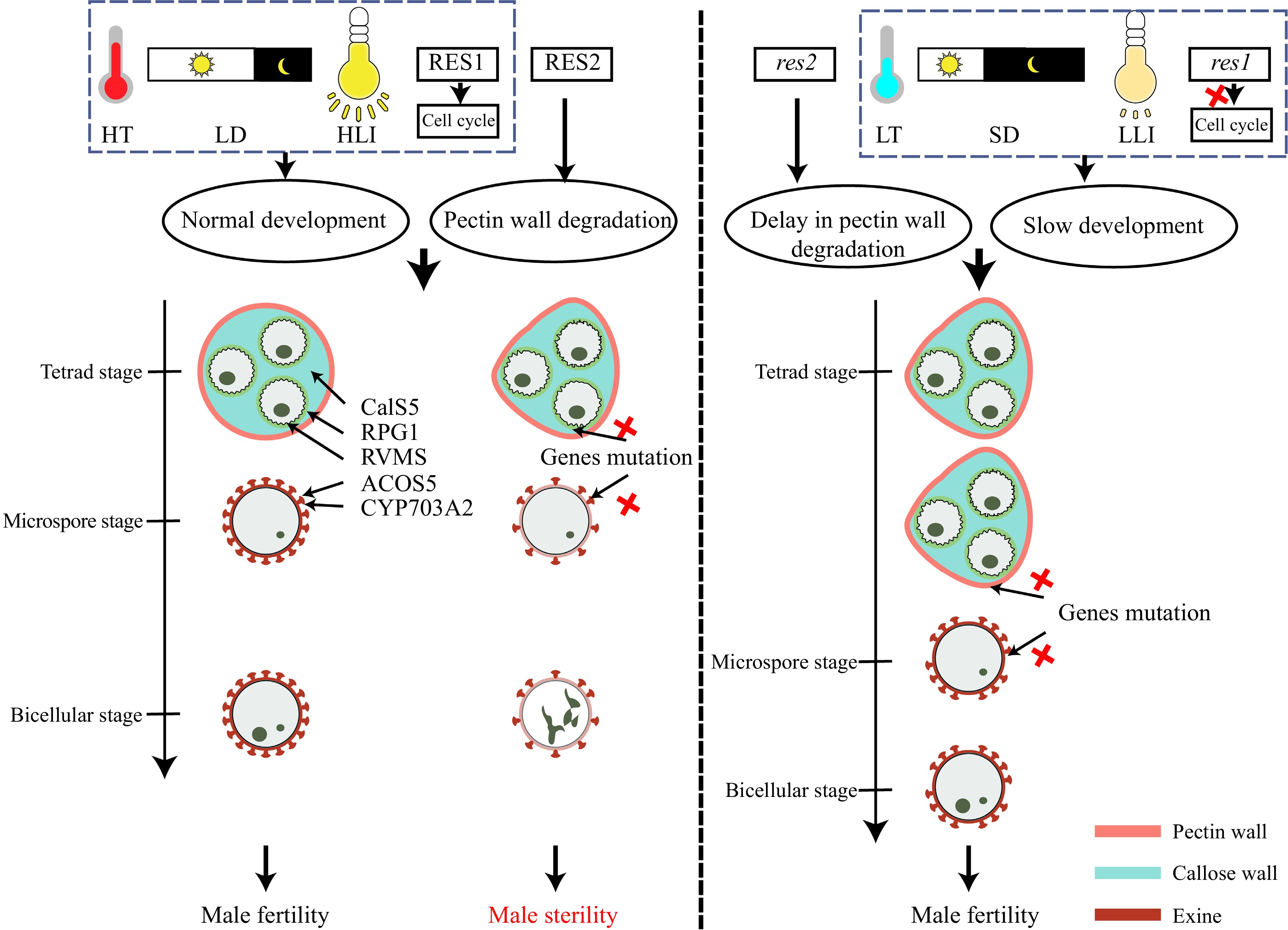

Mechanisms underlying sterility–fertility conversion in P/TGMS and HGMS lines are of great interest to plant scientists, and it is attractive to figure out whether there is a common mechanism behind it or not. Recent studies have observed that slow development may be a general mechanism of sterility–fertility conversion in P/TGMS lines. This theory claims that low temperature, low light intensity and short-day photoperiod can slow anther development to allow formation of functional pollens in P/TGMS lines[33−38].

The first evidence comes from a TGMS mutant rvms (reversible male sterile) that is male sterile at HT (24 °C) but fertile at LT (17 °C). Interestingly, the double mutant res1 rvms is male fertile at HT. RES1 encodes a CDKA;1 (A-type Cyclin-Dependent Kinase;1) that is required for cell division in male gametogenesis, and res1 is a weak allele that slows male meiosis and microgametogenesis at 24 °C. This effect is consistent with the effect of LT on pollen development, suggesting that slow pollen development restores rvms fertility. This hypothesis is further confirmed by the fact that higher expression of KRP2 (KIP-Related Protein 2), a CDKA; 1 inhibitor, in transgenic rvms partly restores fertility; while crossing rvms with chlm-4, a slow-growth mutant, also rescues rvms sterility[38]. Other TGMS mutants involved in pollen wall patterning (cals5 (callose synthase 5) and rpg1 (ruptured pollen grains 1)), sporopollenin biosynthesis (acos5 (acyl-CoA synthetase 5) and cyp703a2 (cytochrome p450 703a2)), and sporopollenin transportation (abcg26, atp binding cassette g26) are all fertile at HT when crossed with res1[33−38], indicating that slow pollen development is a general mechanism for restoring fertility in Arabidopsis TGMS mutants. But is this mechanism applicable to PGMS? The cals5-2 mutant provides a good answer to this question. cals5-2 was isolated as a TGMS mutant, fertile at LT[38]. Recent studies have also identified it as a PGMS mutant, sterile under LD (16 h) but fertile under SD (8 h) conditions. Furthermore, low light intensity can also restore its fertility[36]. SD conditions and low light intensity could also restore fertility in other classically TGMS lines (acos5, cyp703a2, npu, rpg1 and rvms)[36], demonstrating that slow pollen development is a common mechanism for sterility–fertility conversion in P/TGMS lines, through acting on multiple genetic and biochemical pathways for development of functional pollen.

It is interesting to understand why slow pollen development can restore the fertility of P/TGMS lines. Permissive conditions relieve the requirement for an intact sexine (acos5 and cyp703a2), normal callose wall and primexine formation (npu-2 and cals5-2), and integral plasma membrane formation (rvms), allowing successful development of functional pollen[36]. Other studies show that slow development allows redundant genes to restore the fertility of Arabidopsis TGMS lines, such as rpg1[35]. rpg1 is defective in primexine, which can be partially restored under slow growth conditions through activity of the homologous, and partially redundant, RPG2 gene; fertility recovery of the rpg1 rpg2 double mutant at LT is significantly reduced compared with that of rpg1. Gene redundancy can therefore play important roles in fertility restoration of TGMS lines[35], but its prevalence in other TGMS or PGMS lines remains unresolved. The latest results from other restorers of rvms provide novel insights into the sterility–fertility conversion in P/TMGS lines. res2, a mutation in QRT3 (QUARTET 3) that encodes a polygalacturonase, shows delayed degradation of the tetrad pectin wall, and can restore fertility in rvms and other known P/TGMS lines, including acos5-2, cyp703a2, abcg26-1, cals5-6, rpg1, and rvms-2; delayed pectin wall degradation is thus also a general mechanism for fertility restoration in P/TGMS lines[33]. res3, with a point mutation in UPEX1 (UNEVEN PATTERN OF EXINE 1), shows delayed tetrad callose wall degradation, and can restore fertility of a TGMS mutation defective in nexine formation (rvms–2)[34] and other P/TGMS lines with pollen wall defects. Delayed callose degradation appears to provide extra protection during pollen development, allowing P/TGMS microspores to develop into functional pollen[33,34] (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Slow development and delay in pectin wall degradation can restore fertility in Arabidopsis pollen wall mutants. Low-temperature (LT), short-day (SD), low-light intensity (LLI), and the res1 mutation can slow development of pollen to recover male fertility in Arabidopsis lines defective in pollen wall formation. The res2 mutation delays pectin wall degradation, providing extra protection for developing pollen in pollen-defective mutants. Red crosses indicate loss of function.

These mechanisms found in Arabidopsis are likely conserved in other plants. In rice, OsTMS18/OsNP1 encodes a glucose-methanol-choline (GMC) oxidoreductase, in which a point mutation (Gly to Ser) produces the TGMS ostms18 mutant, male sterile with aborted pollen at HT, while fertile with a flawed but functional pollen wall at LT[97]. Mutants of its Arabidopsis orthologs are fertile at LT but semi-sterile with significantly reduced fertility at HT (28 °C)[97]. ostms15 is a weak allelic mutant of MSP1, containing an amnio acid substitution in its TIR motif that leads to reduced interaction with the ligand OsTDL1A. Unlike the knockout mutant ostms15-cr, the weak allelic mutant can produce defective tapetum at HT, which can be compensated by enhanced interaction with OsTDL1A and slow development at LT[44] (Fig. 1b). In wheat, SCULP1 (SKS clade universal in pollen), a clade of the multicopper oxidase family, is required for p-coumaroylation of sporopollenin and exine integrity; overexpression of SCULP1 can restore exine integrity and male fertility of TGMS wheat line BS366[98]. Since rice, wheat, and Arabidopsis have distinct growth conditions, light and temperature preferences, and different requirements for sterility–fertility conversion, permissive environments for these two species may provide different levels of protection for microspore development at LT.

In rapeseed (Brassica napus), the male-sterility TGMS Lembke (MSL) and 9012AB lines have been extensively used in hybrid breeding in Europe and China, respectively. These lines share many similarities in defective pollen development and abnormal tapetum degradation; importantly, heat shock restores fertility in both lines, which share not only the same restorer gene BnaC9-Tic40 but also the same male sterility gene BnChimera. BnChimera can interact with BnaC9-Tic40 directly, which restores fertility at HT by suppressing expression of anther and pollen developmental genes. In this case, two wrongs make a right; repressing gene expression slows pollen development, providing time for affected plastids to produce enough lipid molecules for pollen wall development[99]. Uniquely, slow development in this case is brought about by HT rather than LT[33,34,36,38,99].

In summary, sterility–fertility conversion in P/TGMS lines can be affected by temperature, light intensity, and photoperiod. Low temperature, low light intensity, and short day generally slow plant development, generating defective but functional pollen to restore fertility. While slow development mechanisms underlying sterility–fertility conversion of P/TGMS lines in Arabidopsis have been extensively studied, relatively little is known in rice and rapeseed, and even less for other species. More work is required to validate the general mechanism and reveal novel specific mechanisms, considering environmental requirements that differ for each species; and to extend these insights into restoration of the more recently discovered HGMS lines.

-

Plant hormones are key regulators of plant development, including male reproduction[18,100,101]. Few studies have focused on the roles of plant hormones in sterility–fertility conversion, although genes involved in plant hormone biosynthesis and transduction are known to be differentially expressed in EGMS lines, and can be used to generate unique hormone-sensitive GMS lines[102−104].

In rice, an early study in PGMS line (Nongken58S) clearly established the relationship between endogenous phytohormones and male fertility. Deficiency of IAA (indole-3-acetic acid) at early developmental stages, reduction of GAs at late developmental stages, and decrease in ABA (abscisic acid) lead to male sterility of Nongkeng58S under LD conditions[105]. Recently, a study found that jasmonic acid (JA) is a pivotal regulator for fertility conversion in both PGMS and TGMS rice lines. Exogenous spraying of JA analog on Nongken58S and D52S (a rPGMS line) partially restores male fertility, indicating that JA is but not the sole hormone in the fertility conversion[103].

In wheat, LT and/or SD at the critical period (from the pollen mother cell meiotic stage to the early mononucleate stage of microsporogenesis) induce sterility[102]. Conversely, HT and/or LD conditions at the critical period induce fertility by reversing levels of these hormones in anthers. By adjusting the sowing date, environmental conditions for inducing sterility/fertility in P/TGMS wheat can be easily created; alternatively, exogenous application of hormones at the critical period can also affect fertility[102]. However, the exact molecular mechanisms behind hormonal involvement in sterility–fertility conversion in P/TGMS lines remain unresolved.

-

Climate change, with the associated warmer temperatures and more frequent extreme climate events, is creating increasingly adverse environmental conditions for plant growth, impairing development and reproduction that can result in crop failures[106−108]. Male reproduction is particularly vulnerable to temperature and humidity aberrations. Therefore, understanding mechanisms that control adaptations of plant male reproductive development to environmental cues is of fundamental importance for sustaining agriculture and food security.

Plants have evolved various molecular switches to adapt to changing environments, several of which have been uncovered in model plants, including Arabidopsis and rice. These molecular switches, such as TMS10/TMS10L and CSA/CSA2, regulate fertility conversion via different mechanisms in response to environmental conditions[32,81,84−86,88,91,93,95]. Slow development appears to be a common mechanism to rescue fertility in P/TGMS lines, which allows mutant lines to generate defective but functional pollens in permissive temperature or daylength conditions[33,34,36,38,99]. While this mechanism is conserved in Arabidopsis, rice and rapeseed, broader application to other agricultural crops remains to be validated. Nevertheless, the mechanism underlying fertility conversion for HGMS is not yet clear. Apparently, it is different from P/TGMS, in HGMS, only the pollen coat is affected. But it must be some connection between HGMS and P/TGMS, because lipidic molecules are important components of anther wall, pollen wall and pollen coat, although P/TGMS is also related to cell wall components such as callose, pectin[33,34]. Elucidating the exact lipid molecules and genes/pathways involved will be helpful to explore mechanisms of HGMS. We believe that with the discovery and identification of further relevant molecular switches, we will better understand the processes and underlying genetic and/or biochemical bases for environmental adaption of plant male reproduction.

All EGMS lines mentioned in this review are from natural or induced mutants in cultivated plant species; the revealed molecular modules thus reflect the consequence of domestication and artificial selection at the single gene level. While detecting the fertility variations between a mutant and its wild type is generally straightforward, identifying the underlying genetic basis is quite difficult. Although whole genome sequencing-based genomics and pangenomics studies have paved the way for high throughput identification of causal genomic or structural variations for important traits[109], such approaches have never been used to identify genetic mechanisms underlying natural variations in male reproduction in response to environment, nor to mine genes underlying EGMS in wild varieties lost during domestication and improvement[110]. Outputs from such studies would greatly advance our understanding of plant male reproduction adaptation mechanisms. In addition, critical transition points responding to environmental factors differ significantly depending on species and cultivars, these points are vital for accurately determination of genetic bases of EGMS. Critical transition points need to be defined case by case in the future to establish helpful platform for mining novel EGMS lines and elucidating underlying mechanisms, distinguishing and obtaining pure PGMS and/or TGMS lines.

Although some EGMS genes have been well characterized, few germplasms are applicable in hybrid seed production as many genes have side effects, creating a desperate need to identify new useful lines. Considering the growing complexity of environmental factors, a successful strategy may involve combining P/TGMS and HGMS mutations to build environmental resilience and increase utility of identified genes.

Authors are grateful to late Prof. Dabing Zhang for his initiating, encouraging and supervising this manuscript. We will always remember him as our esteemed mentor, colleague, and friend. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32130006 and 31970803), Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory Project (B21HJ8104), Jiangsu Provincial Key R&D Programme (BE2021323), Australian Research Council Discovery Project grants (DP210100956 and DP230102476), Australian Research Council Training Centre for Accelerated Future Crop Development (IC210100047), Australian Research Council Linkage (LP210301062), the China Innovative Research Team (Ministry of Education) and the Programme of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities (111 Project, B14016) to Prof. Dabing Zhang.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Dabing Zhang is the Editorial Board member of Seed Biology who was blinded from reviewing or making decisions on the manuscript. The article was subject to the journal's standard procedures, with peer-review handled independently of this Editorial Board member and his research groups.

- Copyright: © 2023 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu D, Shi J, Liang W, Zhang D. 2023. Molecular mechanisms underlying plant environment-sensitive genic male sterility and fertility restoration. Seed Biology 2:13 doi: 10.48130/SeedBio-2023-0013

Molecular mechanisms underlying plant environment-sensitive genic male sterility and fertility restoration

- Received: 11 April 2023

- Accepted: 26 July 2023

- Published online: 16 August 2023

Abstract: Male reproduction, an essential and vulnerable process in the plant life cycle, is easily disrupted by changes in surrounding environmental factors such as temperature, photoperiod, or humidity. Plants have evolved multiple mechanisms to buffer adverse environmental effects; understanding these mechanisms is crucial to increase crop resilience to a changing climate, and to provide new breeding tools for hybrid seed production. Here, we review the latest research progress in molecular mechanisms underlying plant environment-sensitive genic male sterility and fertility restoration, covering both genetic and epigenetic aspects, and summarize the common molecular mechanisms underlying fertility conversion, using knowledge obtained from photoperiod/thermo-sensitive genic male sterility (P/TGMS) mutants. This review aims to better understand male fertility adaptation in response to environmental factors, with a focus on future applications for two-line hybrid breeding.