-

Selenium is an essential trace non-metallic element for humans and animals, which has physiological regulatory functions, such as antioxidant, immune enhancement, aging delay, and anti-cancer effects[1]. About 80% of selenium in selenium-enriched tea exists in organic forms, which are more readily absorbed and utilized by the human body, thus making it an ideal dietary selenium source[2]. However, soil selenium resources are limited and unevenly distributed, and even in selenium-enriched regions, such as Ankang and Enshi, the selenium content in tea often fails to meet the standard for selenium-enriched tea[3]. To break through this limitation and obtain more selenium-enriched tea products, researchers have explored a variety of selenium-fortification strategies for tea plants, including soil selenium application, foliar selenium fertilizer sprays, and microbial-assisted selenium uptake. As a traditional and effective basic method, the effect of soil application of selenium is affected by a variety of factors, such as soil type, pH, and organic matter content[4]. Foliar spraying of selenium fertilizer, as a more efficient and direct method, can deliver selenium rapidly into the plant aboveground, thus significantly increasing the selenium content in the plant aboveground[5]. Compared with soil application of selenium, foliar application is more effective, can increase the selenium content of tea in a short period, and is more suitable for producing selenium-enriched tea[6]. In recent years, the role of microbial-assisted selenium uptake as an emerging selenium-fortification strategy in plant selenium uptake has attracted much attention. Selenium-reducing bacteria are a group of microorganisms capable of reducing inorganic selenium in soil to elemental selenium, playing a crucial role in the transformation of soil selenium, as well as in the uptake and utilization of selenium by plants[7]. Strains such as Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas spp. can reduce sodium selenite to selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs), which are subsequently widely used for selenium fortification in crops[8]. The endophytic bacterium Herbaspirillum sp. WT00C-Se, isolated from tea plants, has been reported to be able to synthesize SeNPs and actively participate in selenoprotein synthesis in tea plants[9]. However, how to explore beneficial bacteria for further application in practical production has become an urgent challenge to be addressed.

Developing selenium-enriched microbial fertilizers has become a crucial solution to the issues mentioned above. These fertilizers not only retain the comprehensive advantages of traditional microbial fertilizers, such as improving soil structure, enhancing soil fertility, and promoting crop growth, but also achieve efficient selenium utilization by introducing functional strains, thereby opening new avenues for improving crop yield and quality[10]. For instance, a highly selenium-tolerant Enterobacter strain (H1) has been utilized to produce selenium-enriched microbial fertilizers for the cultivation of selenium-enriched agricultural products[11]. Meanwhile, numerous studies have demonstrated the significant effects of selenium-enriched microbial fertilizers in agricultural applications. For example, foliar application of bio-nano-selenium agents significantly increased the total and organic selenium content in rice compared to sodium selenite treatment, while also enhancing yield and quality[12]. Similarly, foliar spraying of Bacillus subtilis (SE201412) nano-selenium agents significantly improved selenium content and the proportion of organic selenium in wheat and rice[13]. Despite these advancements, microbial-assisted selenium supplementation technology in producing selenium-enriched tea remains insufficient.

In this study, a highly efficient selenium-reducing bacterium (Raoultella ornithinolytica S-1, S-1) was screened from selenium-enriched tea garden soil, and an S-1 bio-nano selenium microbial agent (S-1 SeNPs) was prepared. Further research systematically analyzed the effects of this microbial agent on the selenium content, quality indicators, and elemental composition of summer-autumn young tea shoots, aiming to provide new insights into the exploration of selenium-enriched microbial resources and the improvement of the quality of summer-autumn tea.

-

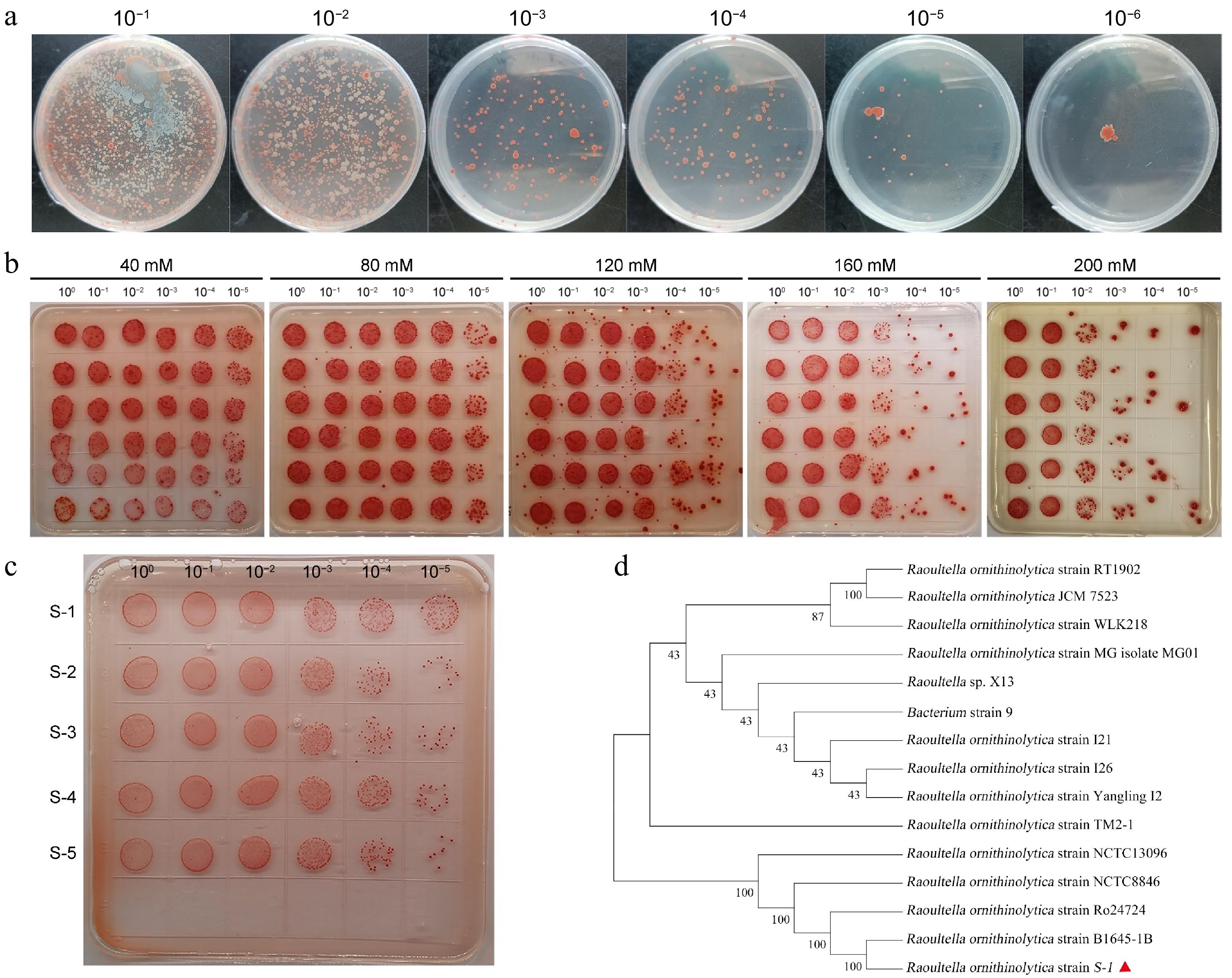

Weigh 10 g of soil sample collected from a selenium-enriched tea garden (32°56' N, 108°70' E, Ankang, Shaanxi, China), and add it to 90 mL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Shake at 30 °C and 200 rpm for 30 min, let stand for 5 min, and then centrifuge at 6,000 g for 8 min. Take the supernatant and perform a gradient dilution from 10−1 to 10−6. Spread 100 μL of each dilution onto LB solid medium containing 1 mM sodium selenite, and incubate at 28 °C for 40 h. Select strains with vigorous growth and conspicuous coloration for preservation.

Inoculate the preserved strains into LB liquid medium and culture at 28 °C and 180 rpm until OD600 of 0.8. Dilute the bacterial suspension to 10−5, then spot 2.5 μL onto LB solid medium containing 1−200 mM sodium selenite. Incubate upside down at 28 °C for 48 h, and observe the colony morphological characteristics. Select strains with high selenium tolerance, amplify the 16S rRNA gene, and sequence it according to the method described by Al-Hagar et al.[14], and construct a phylogenetic tree using MEGA 7 software.

Characterization of bio-selenium nanoparticles

-

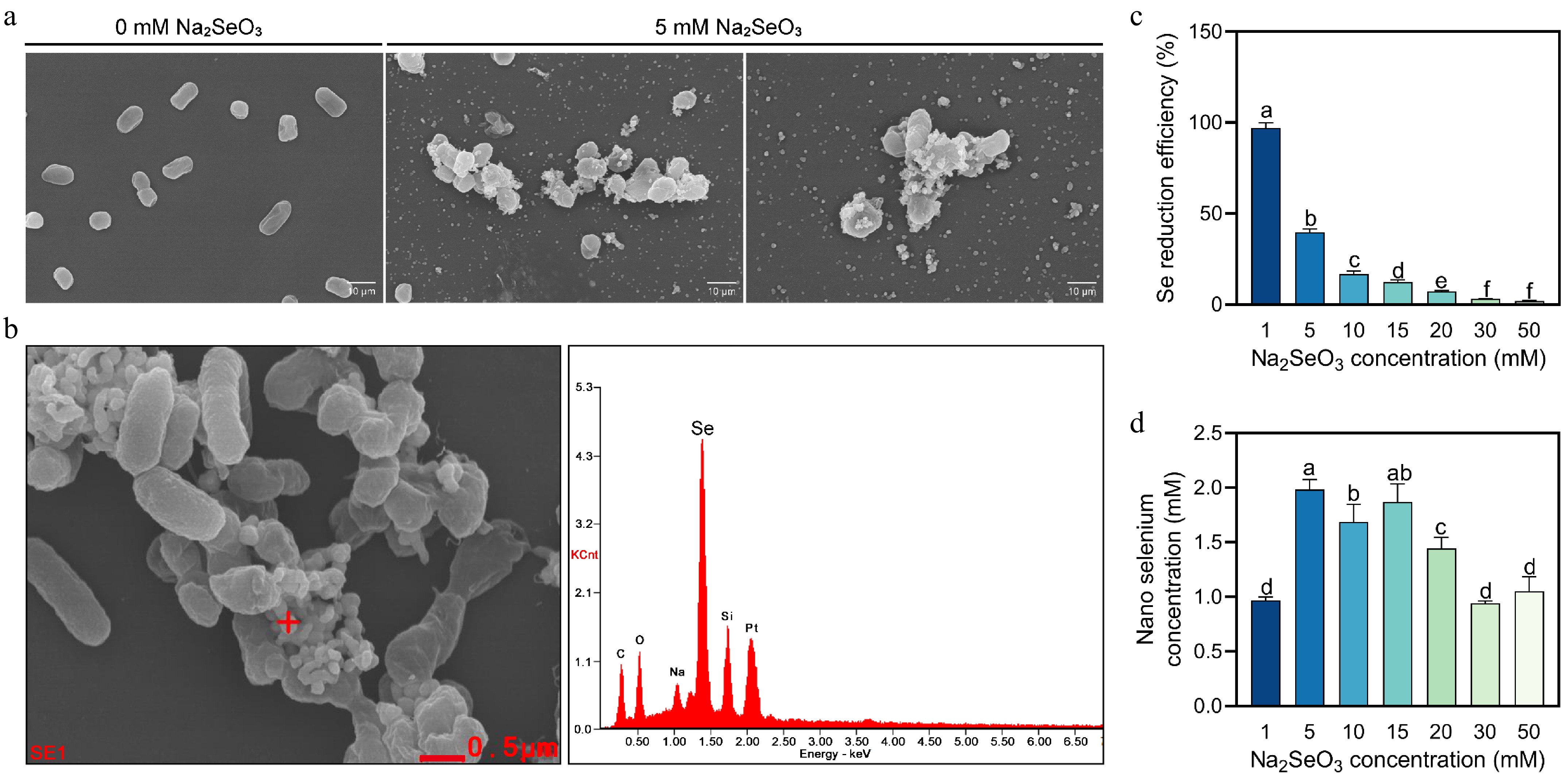

The bacterial suspension with an OD600 of 0.8 was inoculated at 0.1% into LB medium containing 5 mM sodium selenite and a control medium, followed by incubation at 28 °C and 180 rpm for 48 h. After the culture turned red, it was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 8 min, and the pellet was washed three times with saline. The samples were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (4 °C overnight), rinsed with 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.2) two to three times (10 min each), dehydrated with a graded ethanol series (30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100%)[15], treated with isoamyl acetate for 10 min, and dried using CO2 critical point drying. The dried samples were observed using field emission scanning electron microscopy (SU5000, Hitachi, Japan), and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was performed to analyze the spherical nanoparticles.

Analysis of selenium reducing capacity

-

The selenium-reducing capability of the strain was quantified using the Na2S colorimetric method[16]. Single colonies were inoculated into LB medium and cultured at 28 °C and 180 rpm until OD600 reached 0.8. The bacterial suspension was then inoculated at 0.1% into LB medium containing varying concentrations of sodium selenite and cultured under the same conditions for 48 h. After centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 8 min, the pellet was washed three times with distilled water and mixed with 1 M Na2S solution at a 1:2 (v/v) ratio. The mixture was allowed to react for 1 h, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 3 min, and the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 500 nm, using a blank Na2S solution as the control. Three replicates were set up for each concentration. A standard curve was plotted using elemental selenium as the standard, and the content of reduced elemental selenium was calculated. The selenium reduction efficiency (%) was determined using the formula: (Amount of reduced elemental selenium/Amount of selenium in Na2SeO3) × 100%.

Analysis of the growth-promoting ability in S-1

-

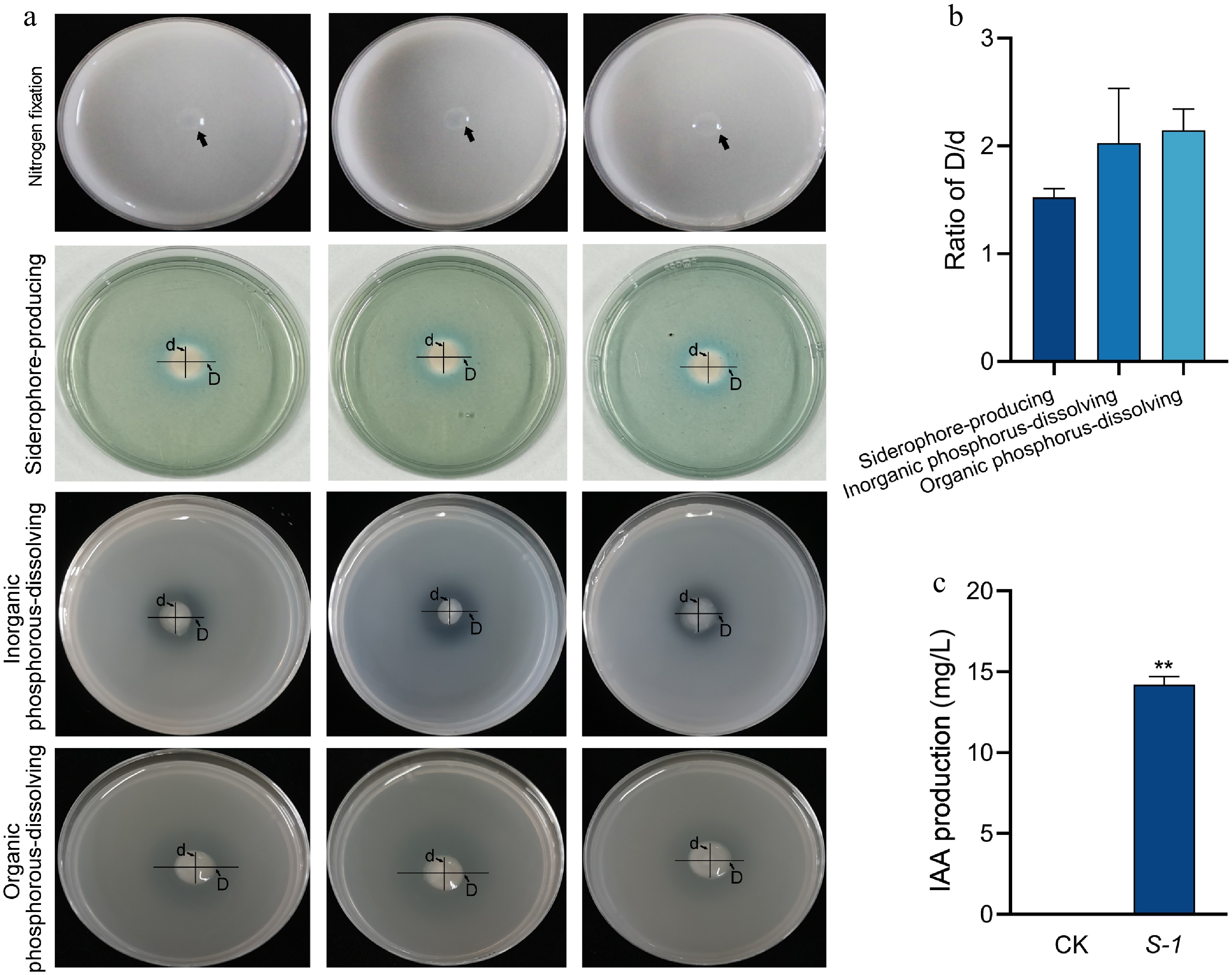

The strain was inoculated at 1% into a nitrogen-containing medium supplemented with 100 mg/L tryptophan and cultured at 28 °C and 180 rpm for 48 h. After centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of Salkowski reagent and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min, using uninoculated medium as the control. The appearance of a red colour indicated the strain's ability to produce IAA, and the OD530 was measured to calculate the concentration based on the IAA standard curve.

To evaluate the strain's nitrogen-fixing, phosphate-solubilising, and siderophore-producing capabilities, the strain was inoculated into LB liquid medium and cultured at 28 °C until OD600 reached 0.8. The bacterial suspension was then spotted onto inorganic phosphorus, organic phosphorus, and CAS solid media, followed by incubation at 28 °C in the dark for 7 d. The ratio of the phosphate-solubilizing halo diameter (D) to the colony diameter (d) (D/d) was used to assess the phosphate-solubilising and siderophore-producing abilities. Simultaneously, the strain was inoculated onto Ashby solid medium and subcultured thrice at 28 °C. Strains exhibiting normal growth were identified as having nitrogen-fixing activity.

Preparation of S-1 SeNPs

-

The S-1 bacterial suspension (OD600 to 0.8) was inoculated at 2%−16% into the initial liquid medium containing five mM sodium selenite (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, and 10 g/L NaCl) and cultured at 28 °C and 180 rpm for 24 h. After centrifugation, the wet weight of the bacterial cells was measured to determine the optimal inoculation amount. The selenium enrichment rate was evaluated under different carbon sources (glucose, sucrose, soluble starch, maltose, lactose, and mannitol, each at 10 g/L), inorganic salts (KCl, MnSO4, CaCl2, and MgSO4 replacing NaCl), and nitrogen source combinations [tryptone; yeast extract and tryptone (1:1); yeast powder and tryptone (1:1); yeast extract and peptone (1:1); beef extract and yeast extract (1:1), each at 15 g replacing the initial nitrogen source], thereby determining the optimal fermentation medium formulation. The selenium enrichment rate was calculated using the formula: Selenium enrichment rate (%) = Total selenium content absorbed by cells (μg/mL)/Amount of selenium added × 100%.

Using the screened optimal inoculation amount and the best fermentation medium, the culture was incubated at 28 °C and 180 rpm for 48 h. After centrifugation, the precipitate was collected, washed three times with 5% monosodium glutamate, and freeze-dried to prepare S-1 SeNPs. Then, 0.1 g of S-1 SeNPs was weighed, dissolved in sterile water, and adjusted to a volume of 10 mL. A 1 mL aliquot was taken and subjected to a 10-fold serial dilution. A 100 μL volume of each dilution was spread onto LB agar plates. After incubation at 28 °C for 16 h, the colonies were counted. The viable bacterial count (CFU/g) was calculated using the formula: Viable bacterial count (CFU/g) = (C/V) × M, where C is the average colony count, V is the volume plated (mL), and M is the dilution factor.

Plant materials and treatments

-

The perennial tea variety 'Shaancha 1' was selected as the experimental material, with seedlings cultivated at the Xixiang Tea Experimental Demonstration Station of Northwest A&F University (23°34' N, 107°15' E, Hanzhong, Shaanxi, China). The experiment commenced on July 20, 2024, involving foliar applications of Na2SeO3 solutions at concentrations of 20 mg/L, 40 mg/L, and 80 mg/L, as well as S-1 SeNPs, with water spray as the control (CK). The second application was conducted 7 d apart, totalling two applications. Each treatment covered an area exceeding 50 m2, with 15 m² designated as one biological replicate. On August 17, healthy young leaves (1−3) and mature leaves (4−6) were collected, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, freeze-dried, and stored at −80 °C for subsequent analysis.

Determination of selenium, fluorine, and partial metal element content

-

Accurately weigh 0.1 g of the sample into a 50 mL polytetrafluoroethylene digestion tube, add 5 mL of pure nitric acid, and perform microwave digestion at 160 °C for 2 h. After digestion, evaporate the acid until 1−2 mL remains, cool, and dilute to 50 mL with ultrapure water. For measurement, mix 3 mL of the digested solution with 50% hydrochloric acid in a 10 mL centrifuge tube, heat in a boiling water bath for more than 30 min, cool, and determine the selenium content in the solution using atomic fluorescence spectrometry (AFS8530, Haiguang, China). The determination of fluorine and other metal elements was conducted according to the method reported by Niu et al.[17].

Determination of major biochemical components in tea fresh leaves

-

The contents of total tea polyphenols, total free amino acids, water extract, and soluble sugars were determined according to previously published methods[18]. The contents of catechin monomers and caffeine were measured using an LC-2030CD HPLC system (Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a reversed-phase column (Agilent C18, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm), as described in the literature[19]. The theanine content was determined using an LC-30A HPLC system (Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a reversed-phase column (Agilent C18 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm), with the HPLC elution conditions and parameter settings as described in the previous method[20].

Statistical analysis

-

All experiments were performed with three replicates. Data were analyzed using SPSS V26.0 software. Duncan's multiple range test was used for one-way analysis of variance (p < 0.05) to assess the significance of differences among treatments, In contrast, Student's t-test was used to evaluate the importance of differences between two samples. Bar graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 9.0 software.

-

As shown in Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S1, bacteria growing on sodium selenite-containing plates exhibited normal growth and red coloration, indicating their potential for high selenium tolerance and reduction capability. Selenium tolerance evaluation results showed that some screened strains maintained robust growth even at a concentration of 160 mM sodium selenite (Fig. 1b). Further screening at a concentration of 200 mM identified five candidate strains with exceptional selenium tolerance. Repeated evaluations at this concentration demonstrated that S-1 exhibited the highest selenium tolerance (Fig. 1c). Phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA sequencing results indicated that it shared high sequence similarity with the strain B1645-1B and was named Raoultella ornithinolytica S-1 (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1.

Screening and identification of strain S-1. (a) Isolation of soil selenium-reducing bacteria. (b) Determination of selenium tolerance screening conditions. (c) Evaluation of selenium resistance in S-1. (d) Phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequence in S-1.

Characterization of S-1 synthetic selenium nanoparticles and evaluation of their growth-promoting ability

-

Scanning electron microscopy results showed a significant accumulation of spherical particles around S-1 under the incubation condition with the addition of 5 mM sodium selenite (Fig. 2a). Further energy spectrum analysis showed that there was a characteristic absorption peak of elemental selenium at 1.37 keV, and these selenium nanoparticles had a particle size of 167.3 ± 27.3 nm (Fig. 2b). In addition, the selenium reduction efficiency reached a maximum efficiency of 97% under 1 mM sodium selenite treatment and showed a decreasing trend with increasing selenium concentration (Fig. 2c). In contrast, the concentration of nanosized selenium showed an increasing and then decreasing trend with the increase of sodium selenite concentration, reaching a peak at 5 mM (Fig. 2d). The plate observation test showed that S-1 could grow normally on Ashby's medium; it produced yellowish and phosphorus-dissolving hyaline circles on CAS medium and phosphate-dissolving medium (Fig. 3a & b), respectively, and it also had a specific IAA-producing ability (Fig. 3c). These results indicate that S-1 not only has the ability to efficiently reduce sodium selenite to red monolithic selenium nanoparticles, but also possesses growth-promoting functions such as nitrogen fixation, phosphorus-dissolving, siderophore-producing capacity and IAA synthesis.

Figure 2.

S-1 Synthesis of bio-nano selenium characterization and selenium reduction capacity analysis. (a) Observation of bio-nano selenium. (b) Characterization of bio-nano selenium. (c), (d) Selenium reduction capacity analysis. Each bar indicates the mean ± SD, and statistical significance (p < 0.05) is indicated by different letters according to Duncan's multiple range test.

Figure 3.

Analysis of the growth-promoting capacity of S-1. (a), (b) Analysis of nitrogen fixation, phosphorus-dissolving, and siderophore-producing capacity. (c) Analysis of IAA production capacity. Each bar indicates the mean ± SD. Asterisks represent statistical significance determined by Student's t-test (** p < 0.01).

Optimization of S-1 SeNPs preparation

-

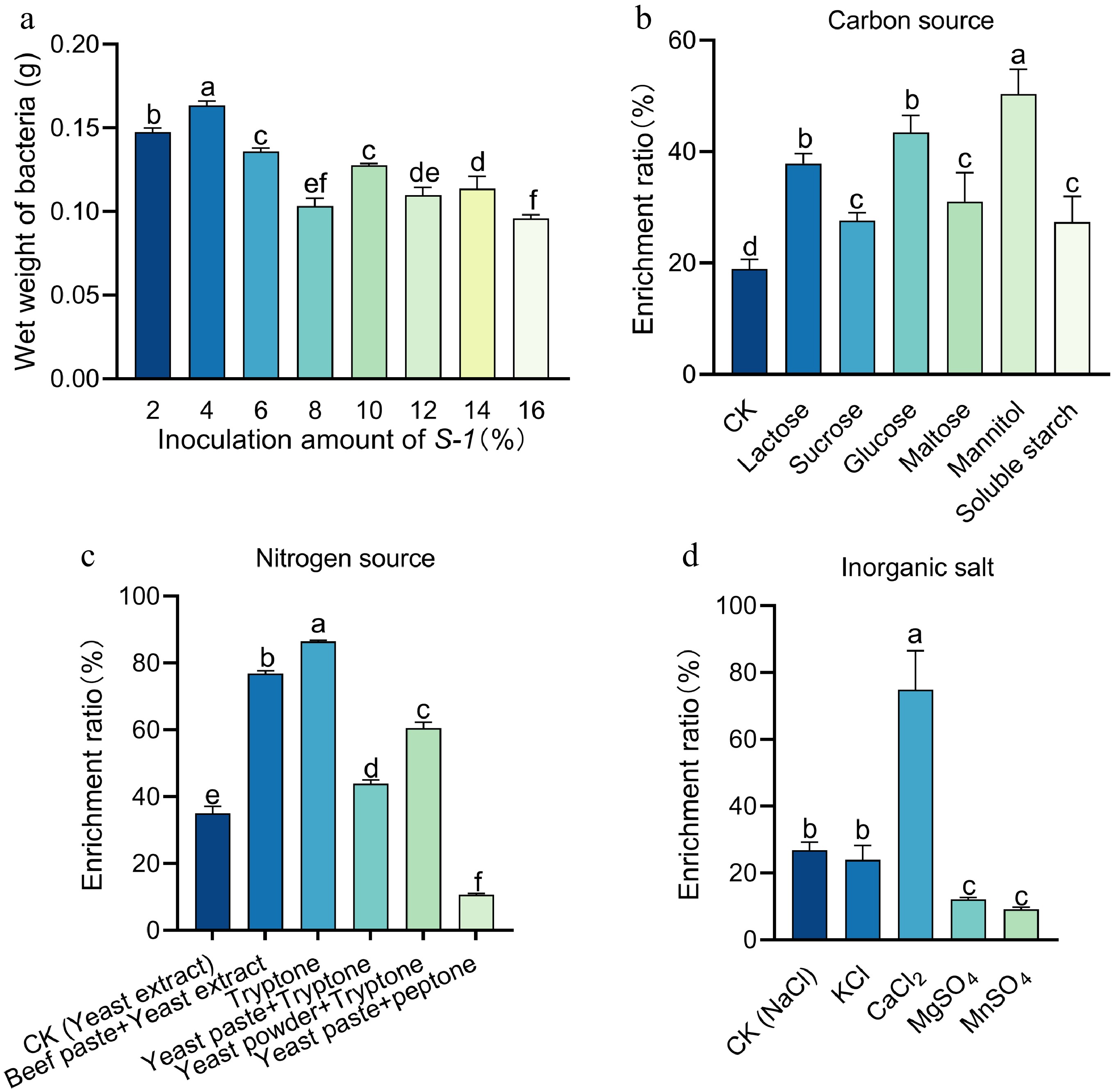

Under different inoculation levels, the wet weight of bacterial showed significant differences, with the highest value achieved at a 4% inoculation level (Fig. 4a). Screening of carbon sources revealed that the selenium enrichment rate under mannitol treatment was significantly higher than that of other carbon sources (Fig. 4b). Nitrogen source screening results indicated that the selenium enrichment rate of S-1 was highest when tryptone was used as the sole nitrogen source (Fig. 4c). Inorganic salt screening results demonstrated that the selenium enrichment rate under calcium chloride treatment was superior to that of other inorganic salts (Fig. 4d). Based on the above experimental results, the optimal conditions were determined to be a sodium selenite concentration of 5 mM, an inoculation level of 4%, and a fermentation medium composed of mannitol (carbon source), tryptone (nitrogen source), and CaCl2 (inorganic salt). Under these optimized conditions, S-1 SeNPs were successfully prepared, with a red nano-selenium content of 50 mg/g and a viable bacterial count of 3.63 × 109/g (Supplementary Fig. S2a & S2b).

Figure 4.

Optimization of the fermentation medium for S-1 SeNPs. (a) Determination of optimal inoculum amount for S-1. (b)−(d) Screening of optimal nitrogen source, carbon source and inorganic salts. Each bar indicates the mean ± SD, and statistical significance (p < 0.05) is indicated by different letters according to Duncan's multiple range test.

Effect of S-1 SeNPs on the selenium content of summer-autumn tea fresh leaves

-

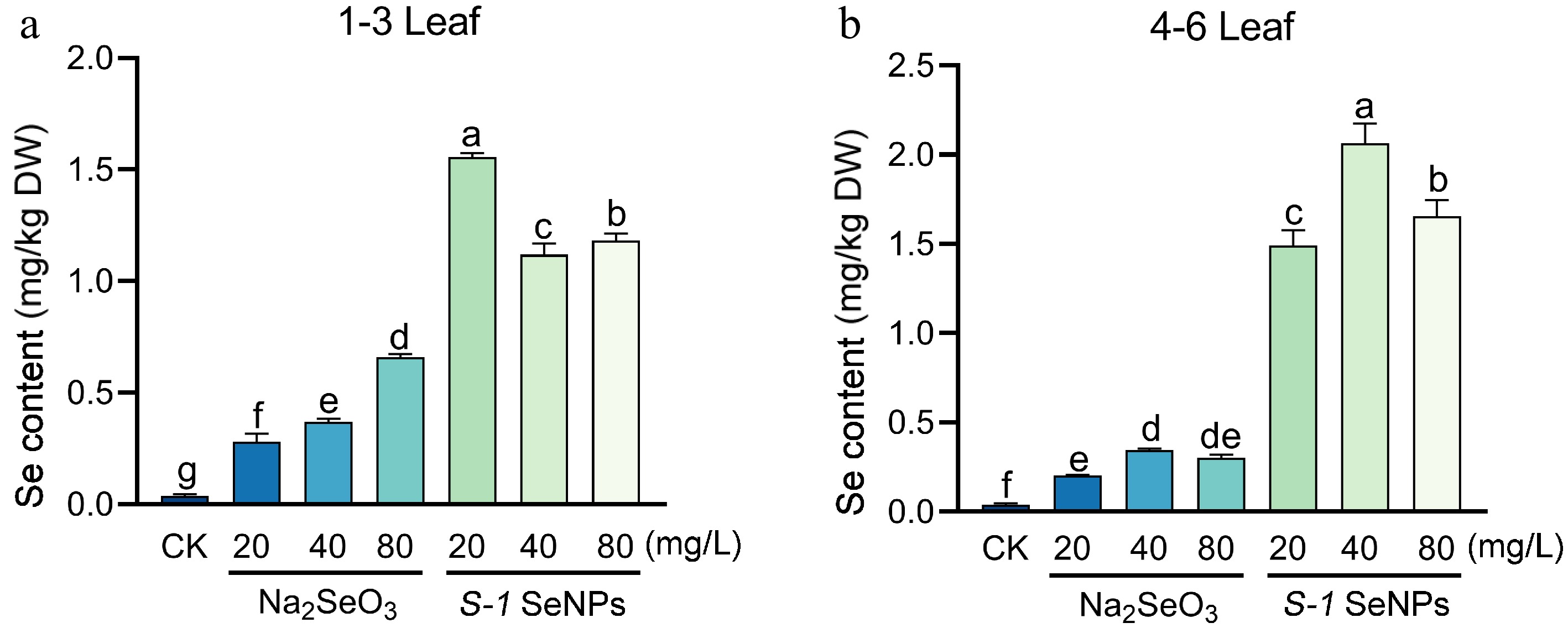

As shown in Fig. 5, the selenium content in both young and mature leaves increased significantly under different selenium treatments compared with the blank control sprayed with water, both exceeding 0.2 mg/kg. In young leaves (1−3 leaves), the selenium content increased significantly with the increase in sprayed Na2SeO3 concentration, reaching the highest value (0.65 mg/kg) at 80 mg/L; and under the same concentration gradient of the S-1 treatment, the selenium content in fresh leaves was elevated by 12.3% (20 mg/L), 18.7% (40 mg/L) and 32.1% (80 mg/L), respectively, compared to Na2SeO3 treatment (Fig. 4a). As shown in Fig. 4b, the trend of selenium accumulation in mature leaves (4−6 leaves) after Na2SeO3 treatment was largely consistent with that in young leaves, but the overall accumulation was reduced; similarly, the selenium enrichment effect of S-1 SeNPs treatment was significantly better than that under Na2SeO3 treatment. The above results indicate that S-1 SeNPs could effectively increase the selenium content of summer-autumn tea fresh leaves, and the selenium enrichment effect is superior to that of Na2SeO3 treatment.

Figure 5.

Selenium content in summer-autumn tea fresh leaves after foliar spraying with S-1 SeNPs and Na2SeO3. (a) Selenium content of summer-autumn tea in young leaves. (b) Selenium content of summer-autumn tea in mature leaves. Each bar indicates the mean ± SD, and statistical significance (p < 0.05) is indicated by different letters according to Duncan's multiple range test.

Effects of S-1 SeNPs on the quality components of summer-autumn tea fresh leaves

-

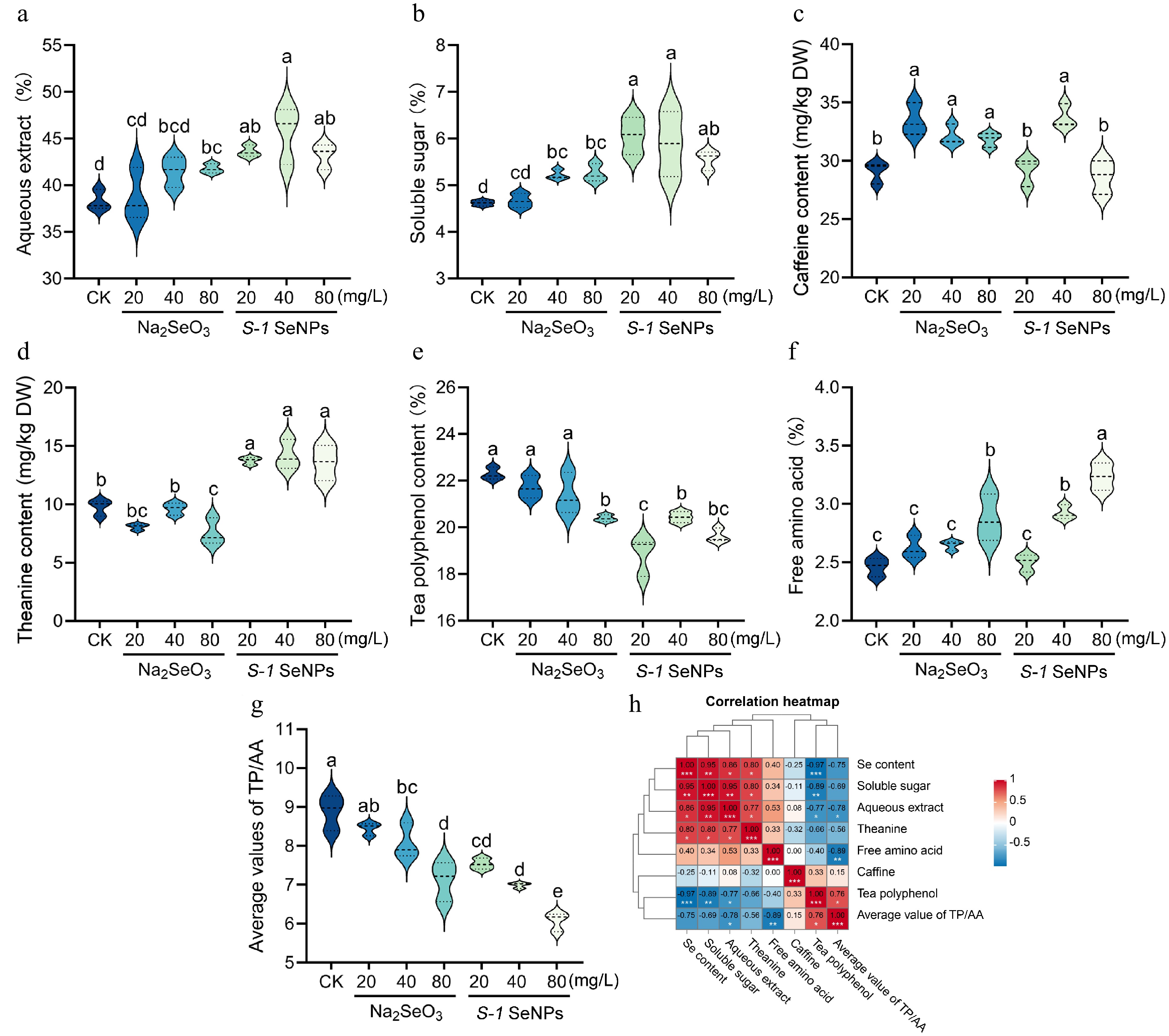

As shown in Fig. 6a, the S-1 SeNPs treatment significantly increased the aqueous extract at all concentrations, with an increase of 18.3%−21.5% over the Na2SeO3 treatment. The analysis of soluble sugar content showed that S-1 SeNPs was significantly better than Na2SeO3 at low and medium concentrations (20 and 40 mg/L), with increases of 30.0% and 12.6%, respectively (Fig. 6b). The results of caffeine content showed that all concentrations of Na2SeO3 significantly promoted its accumulation compared to CK, In comparison, S-1 SeNPs significantly increased caffeine content only at 40 mg/L (Fig. 6c). In terms of amino acid metabolism, S-1 SeNPs treatment significantly increased the theanine and free amino acid content, with free amino acid reaching the peak at 80 mg/L (3.23%), which was 31.3% higher than CK and 12.5% higher than the same concentration of Na2SeO3 treatment (Fig. 6d & e). Notably, the S-1 SeNPs treatment significantly reduced the tea polyphenol content, whereas Na2SeO3 showed inhibitory effect only at 80 mg/L (Fig. 6f). The phenol-ammonia ratio (the ratio of tea polyphenols to free amino acids) decreased with higher selenium concentrations (Fig. 6g). Correlation analysis further confirmed that selenium content was significantly positively correlated with aqueous extract, soluble sugar and theanine, but negatively correlated with tea polyphenols (Fig. 6h). The above results indicate that foliar application of S-1 SeNPs affects the content of major biochemical components in summer-autumn tea fresh leaves, reduces the accumulation of bitter and astringent substances, and increases the levels of sweet and umami compounds, which may help to improve the quality of summer-autumn tea.

Figure 6.

Content of major biochemical components in summer-autumn tea fresh leaves after foliar spraying with S-1 SeNPs. (a)−(f) Content of aqueous extract, soluble sugar, caffeine, theanine, tea polyphenols, and free amino acids. (g) Phenol-ammonia ratio. (h) Heat map of correlation between selenium and major biochemical components. Each bar indicates the mean ± SD, and statistical significance (p < 0.05) is indicated by different letters according to Duncan's multiple range test.

Effect of S-1 SeNPs on catechin fractions of summer-autumn tea fresh leaves

-

As shown in Table 1, there were significant differences in the effects of different selenium treatments on the catechin fractions of young tea leaves. Regarding EGCG content, only the S-1 SeNPs treatments of 20 and 80 mg/L significantly reduced it compared with CK. ECG content was significantly reduced under both the Na2SeO3 treatment of 80 mg/L and the S-1 SeNPs treatments of 40 and 80 mg/L, with a greater reduction observed under the S-1 SeNPs treatment. Notably, CG and C contents were significantly reduced only under S-1 SeNPs treatment, with C content significantly decreased across the range of 20−80 mg/L. GCG content, on the other hand, was significantly increased under the 40 and 80 mg/L S-1 SeNPs treatments. In terms of total catechin content, S-1 SeNPs treatment significantly reduced the total amount in young leaves reaching the lowest value at 80 mg/L, whereas Na2SeO3 treatment did not have a significant effect on the total amount of catechins. Further analysis showed that Na2SeO3 treatment did not significantly affect the ester catechin content, whereas S-1 SeNPs treatments at 20 and 80 mg/L significantly reduced the total ester catechins (Supplementary Fig. S3a). For non-ester catechins, 20 and 40 mg/L Na2SeO3 and 40 and 80 mg/L S-1 SeNPs treatments reduced their total content (Supplementary Fig. S3b). Correlation analysis showed that selenium content was significantly negatively correlated with ester catechins, CG, and C contents, while the negative correlation with EGCG and ECG contents did not reach a significant level (Supplementary Fig. S3c). The above results indicate that S-1 SeNPs can effectively reduce the intensity of catechin accumulation in summer-autumn tea fresh leaves, and their inhibitory effect was significantly stronger than that of Na2SeO3 treatment.

Table 1. Content of catechin fractions in young summer-autumn tea fresh leaves after foliar spraying with S-1 SeNPs (mg/g DW).

Treatment GC EGC C EC EGCG ECG CG GCG Total catechins CK 5.009 ± 0.088b 10.062 ± 0.295b 7.303 ± 0.056a 10.327 ± 0.316a 113.74 ± 2.977a 13.138 ± 0.516b 3.543 ± 0.071ab 0.4 ± 0.025cd 163.521 ± 2.095ab Na2SeO3-20 4.143 ± 0.138d 9.844 ± 0.355b 7.253 ± 0.575a 8.707 ± 0.414b 115.554 ± 3.866a 14.941 ± 0.854a 3.862 ± 0.34a 0.324 ± 0.068d 164.629 ± 2.943a Na2SeO3-40 4.281 ± 0.131d 9.304 ± 0.193cd 7.173 ± 0.495a 8.684 ± 0.091b 112.828 ± 1.187a 14.065 ± 0.415ab 3.269 ± 0.274ab 0.573 ± 0.095bc 160.177 ± 2.438ab Na2SeO3-80 6.282 ± 0.185a 9.693 ± 0.099bc 7.439 ± 0.662a 8.718 ± 0.102b 114.549 ± 1.504a 11.95 ± 0.331c 3.383 ± 0.246ab 0.38 ± 0.024d 162.396 ± 2.358ab S-1 SeNPs-20 4.735 ± 0.187c 10.589 ± 0.306a 5.844 ± 0.388b 10.352 ± 0.634a 105.053 ± 2.736b 13.673 ± 0.389b 3.083 ± 0.182bc 0.423 ± 0.145cd 153.752 ± 4.743cd S-1 SeNPs-40 6.09 ± 0.085a 8.892 ± 0.259d 6.234 ± 0.599b 7.238 ± 0.258c 115.132 ± 3.000a 11.441 ± 0.824c 2.977 ± 0.441bc 0.691 ± 0.095b 158.695 ± 3.395bc S-1 SeNPs-80 3.539 ± 0.165e 9.973 ± 0.123b 5.614 ± 0.585b 8.941 ± 0.742b 106.393 ± 0.865b 10.566 ± 0.285d 2.64 ± 0.47d 1.223 ± 0.153a 148.889 ± 1.306d Statistical significance (p < 0.05) is indicated by a different lower case letter, based on Duncan's multiple range test. Effect of S-1 SeNPs on F, Al, Cd, and other metal elements content of summer-autumn tea fresh leaves

-

As shown in Table 2, selenium treatments significantly inhibited the accumulation of Al, Cd, Fe, and F elements compared to CK, with S-1 SeNPs inhibiting better than Na2SeO3 treatment. Specifically, S-1 SeNPs treatment significantly reduced Al content at all concentrations, whereas Na2SeO3 had no significant effect only at 40 mg/L. Cd and F contents were reduced by 15.3%−22.1% and 12.5%−18.7% more, respectively, with S-1 SeNPs treatment than with the same concentration of Na2SeO3. Meanwhile, selenium treatment promoted the accumulation of copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn) elements, with Cu significantly enriched at 20 and 80 mg/L, and Zn significantly increased only at 80 mg/L. The response pattern of mature leaves was similar to that of young leaves, but with tissue specificity (Table 3). The S-1 SeNPs treatment significantly inhibited the accumulation of Al, Cd, Fe, and F, with the inhibitory effect on Al being particularly prominent (25.6%−31.2% lower than CK). Concurrently, this treatment enhanced Zn accumulation, particularly at 40 and 80 mg/L concentrations. The Cu content was significantly increased only at 20 and 80 mg/L Na2SeO3 treatments, while no significant changes were observed in the other treatment groups. Correlation analyses showed that selenium content was negatively correlated with Al, Cd, Fe, and F, with selenium content in young leaves reaching a significant negative correlation with Cd accumulation (Supplementary Fig. S4a) and selenium content in mature leaves reaching a significant negative correlation with F accumulation (Supplementary Fig. S4b). These results suggest that selenium may regulate the accumulation process of Al, Cd, Fe, and F through the competitive uptake mechanism, and that the inhibitory effect of S-1 SeNPs was better than that of Na2SeO3 treatment.

Table 2. Content of some elements in young summer-autumn tea fresh leaves after foliar spraying with S-1 SeNPs (mg/kg DW).

Organization Treatment Al Cd Fe Cu Zn F 1−3 Leaf CK 407.609 ± 5.923a 0.128 ± 0.008a 99.057 ± 4.47a 6.022 ± 0.061c 32.425 ± 0.294bc 104.725 ± 3.03a Na2SeO3-20 375.568 ± 12.834b 0.124 ± 0.011a 78.859 ± 11.469bc 7.347 ± 0.104b 32.97 ± 2.084abc 99.491 ± 2.924a Na2SeO3-40 397.657 ± 21.568ab 0.109 ± 0.002b 71.116 ± 4.626cde 6.171 ± 0.171c 33.295 ± 3.386abc 77.664 ± 5.176b Na2SeO3-80 381.622 ± 3.717b 0.103 ± 0.002bc 88.794 ± 7.481ab 7.559 ± 0.145b 38.573 ± 2.712a 78.465 ± 8.538b S-1 SeNPs-20 350.993 ± 22.579c 0.097 ± 0.005c 74.169 ± 7.182cd 7.61 ± 0.145b 36.302 ± 3.15ab 76.088 ± 6.065b S-1 SeNPs-40 266.612 ± 4.941d 0.073 ± 0.006d 61.699 ± 7.701de 6.131 ± 0.367c 30.044 ± 4.754c 60.784 ± 2.947c S-1 SeNPs-80 241.625 ± 4.768e 0.063 ± 0.001d 58.133 ± 4.864e 8.292 ± 0.545a 38.392 ± 2.791a 74.666 ± 5.04b Statistical significance (p < 0.05) is indicated by a different lower case letter, based on Duncan's multiple range test. Table 3. Content of some elements in mature summer-autumn tea fresh leaves after foliar spraying with S-1 SeNPs (mg/kg DW).

Organization Treatment Al Cd Fe Cu Zn F 4−6 Leaf CK 2095.842 ± 112.689a 0.179 ± 0.007a 116.171 ± 2.917a 5.59 ± 0.195c 19.157 ± 1.205b 574.049 ± 24.699a Na2SeO3-20 1453.677 ± 50.696c 0.149 ± 0.009b 82.675 ± 4.345b 6.347 ± 0.117b 23.649 ± 2.844ab 560.489 ± 32.39ab Na2SeO3-40 1701.189 ± 27.697b 0.114 ± 0.003cd 69.753 ± 5.489d 5.262 ± 0.164bc 18.895 ± 1.956b 508.938 ± 7.363c Na2SeO3-80 2023.124 ± 75.592a 0.118 ± 0.012c 85.331 ± 4.176b 7.628 ± 0.494a 19.205 ± 3.683b 529.286 ± 22.752bc S-1 SeNPs-20 1237.24 ± 6.856d 0.114 ± 0.001cd 79.404 ± 2.669bc 5.725 ± 0.321bcd 23.092 ± 2.864ab 397.916 ± 18.117e S-1 SeNPs-40 1283.071 ± 11.484d 0.103 ± 0.004d 73.599 ± 1.643cd 6.164 ± 0.279bc 24.537 ± 2.785a 459.837 ± 13.397d S-1 SeNPs-80 1286.445 ± 42.1d 0.113 ± 0.005cd 84.427 ± 1.015b 5.927 ± 0.723bcd 27.342 ± 2.607a 404.02 ± 17.577e Statistical significance (p < 0.05) is indicated by a different lower case letter, based on Duncan's multiple range test. -

Screening and utilization of selenium-reducing bacteria, a class of microorganisms that can reduce inorganic compounds to selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs), is important for the synthesis of SeNPs and agricultural applications. Whereas the screening of selenium-reducing bacteria is usually exposed to high concentrations of selenium, this approach demonstrates the selenium enrichment efficiency of the bacteria, and exhibits their production of SeNPs[21]. It has been shown that strains such as Enterobacter cloacae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa can tolerate 20 mM sodium selenite and synthesise SeNPs[22], whereas Alcaligenes faecalis Se03 tolerates selenium concentrations up to 120 mM[23]. In this study, we isolated a selenium-tolerant strain, S-1, with a selenium tolerance of 200 mM, which not only efficiently reduced sodium selenite to generate SeNPs but also possessed growth-promoting functions, such as nitrogen fixation, phosphorus-dissolving, siderophore-producing capacity and secretion of IAA. Along with the successful isolation of selenium-reducing bacteria, how to efficiently utilise them to prepare selenium-enriched microbial agents for further use in practical agricultural production has become a key problem to be solved. Therefore, many studies have been carried out to further obtain selenium-enriched microbial agents by tapping the suitable growth of selenium-enriched microorganisms and optimizing the fermentation conditions. For example, Huang et al. successfully prepared a selenium-enriched microbial agent by exploring the optimal temperature and pH for the fermentation of a highly selenium-tolerant strain (Providencia rettgeri HF16-A)[24]. Similarly, Ning et al. successfully prepared a highly efficient selenium-enriched microbial agent (SeK) by investigating the inoculation amount of yeast (Kluyveromyces marxianus YG-4)[25], the optimal selenium concentration, and fermentation conditions. In this study, an efficient synthesis process for S-1 SeNPs was established by systematically optimizing the inoculum volume (4%), sodium selenite concentration (5 mM), carbon and nitrogen sources (mannitol and tryptone), and inorganic salt (calcium chloride). The results provide technical support for the development of new microbial agents with both selenium fortification and plant growth promotion functions, laying the foundation for further verification of their synergistic effects on crop selenium accumulation and quality enhancement under field conditions.

Selenium can be absorbed by plant roots and leaves to enrich selenium in different organs, and the specific mode of application depends on the organs available to the plant[26]. As a typical leaf-used cash crop, tea plants achieve selenium enrichment in leaves and the production of selenium-enriched tea more economically and effectively through foliar selenium application[27]. However, inorganic selenium (e.g., sodium selenite and sodium selenate) remains the primary selenium source in agriculture, despite its low bioavailability and high ecotoxicity[28]. In contrast, SeNPs exhibit higher plant uptake efficiency and lower environmental risks by their nanoscale particle size and surface effect[29]. For example, the selenium content in pomegranate leaves after nano-selenium spraying was significantly higher than that after sodium selenate treatment at the same concentration[30]. Here, we found that the selenium content in both young and mature tea leaves was significantly higher after foliar spraying of S-1 SeNPs compared to Na2SeO3 treatment (both exceeding 1 mg/kg), confirming the significant advantage of S-1 SeNPs in selenium enrichment in tea plants, which is beneficial for enhancing the economic value of tea.

During the summer-autumn tea growing season, persistent high-intensity light radiation influences the carbon-nitrogen metabolic network in young tea shoots, significantly enhancing carbon metabolism. This is specifically manifested as a marked increase in tea polyphenol content and a significant decrease in free amino acid content, resulting in a more bitter and astringent taste in the tea broth, reduced quality, and a significantly lower purchase price compared to spring tea, leading to low comprehensive utilization rates[31]. Additionally, the higher maturity of summer-autumn tea leaves makes them prone to accumulating heavy metal elements such as fluorine, aluminum, and cadmium[32−34], particularly in dark tea made from more mature fresh leaves[35]. Thus, summer-autumn tea faces dual challenges of quality and safety issues. Current measures to improve the quality of summer-autumn tea primarily focus on agronomic practices, processing optimization and biofortification[28,36,37], with a central focus on balancing carbon-nitrogen metabolism and reducing the phenol-to-ammonia ratio to enhance tea flavor and quality. In recent years, exogenous selenium application has emerged as a novel agronomic strategy, not only increasing free amino acid content and reducing tea polyphenol content in young shoots, thereby promoting nitrogen metabolism and significantly lowering the phenol-to-ammonia ratio to effectively improve tea quality[38], but also reducing the content of heavy metals such as fluorine, cadmium, chromium, and lead in tea, thereby enhancing tea safety[39]. In this study, foliar spraying of S-1 SeNPs and Na2SeO3 led to significant changes in metabolites. Specifically, the content of aqueous extracts and soluble sugars increased, while tea polyphenol content decreased, and total free amino acids significantly increased, with S-1 SeNPs showing more pronounced effects compared to sodium selenite. Notably, the phenol-to-ammonia ratio in young leaves significantly decreased after treatment with different concentrations of S-1 SeNPs, reducing bitterness and astringency while enhancing freshness, thereby effectively improving tea quality.

Furthermore, S-1 SeNPs spraying resulted in a significant decrease in catechin content, an increase in caffeine content, and a significant increase in theanine content, consistent with the findings of Huang et al.[40]. Moreover, we found that foliar spraying of S-1 SeNPs and sodium selenite effectively inhibited the accumulation of Al, Cd, and F in tea leaves. However, their regulatory effects exhibited tissue-specific and dose-dependent characteristics. Comparative analysis showed that, at the same selenium application level, S-1 SeNPs had a significantly better synergistic regulatory effect on these three elements than sodium selenite. Selenium's role in plants not only manifests as an antagonistic effect on harmful elements but also involves complex bidirectional regulation of essential trace elements, through competition for transporter channels or modulation of metal-chelating protein expression. This study showed that sodium selenite treatment (20 and 40 mg/L) significantly reduced Fe content in young leaves, while the 80 mg/L treatment had no significant effect on Fe content.

In contrast, S-1 SeNPs treatment significantly reduced Fe accumulation in young leaves at all concentrations. In mature leaves, sodium selenite treatment (20 and 80 mg/L) significantly increased Cu accumulation, while S-1 SeNPs treatment had no significant effect on Cu content. Although different selenium sources differentially regulated Zn content in young leaves, a significant enhancement of Zn content was observed only in mature leaves treated with S-1 SeNPs. These results corroborate the 'diversity of selenium effects hypothesis' proposed by Gui et al.[41], indicating that the regulatory efficacy of selenium is related to its chemical form, application method, dose, and the diversity of plant species. The above results demonstrate that foliar spraying of S-1 SeNPs significantly promotes selenium enrichment in summer-autumn tea, increases free amino acid and theanine content, inhibits the accumulation of tea polyphenols and catechins, reduces the phenol-to-ammonia ratio, and effectively hinders the accumulation of Al, F, and Cd, achieving a synergistic improvement in the quality and safety of summer-autumn tea. This discovery provides an innovative solution to overcome the bottleneck in the high-value utilisation of summer-autumn tea resources and to develop high-value-added selenium-enriched summer-autumn tea products.

-

Here, a highly selenium-tolerant strain, Raoultella ornithinolytica S-1, was isolated from selenium-enriched tea garden soil. This strain not only efficiently reduced sodium selenite to generate SeNPs but also possessed growth-promoting functions. Furthermore, we developed a bio-nano selenium microbial agent with the following preparation parameters: mannitol as the carbon source, tryptone as the nitrogen source, calcium chloride as the inorganic salt, a sodium selenite concentration of 5 mM, and an inoculation volume of 4%. Field trial results demonstrated that foliar spraying of S-1 SeNPs not only significantly increased the selenium content in summer-autumn tea fresh leaves but also reduced the accumulation of bitter and astringent substances, such as tea polyphenols and catechins, while increasing the content of sweet and umami compounds, such as soluble sugars, theanine, and free amino acids. Additionally, it synergistically reduced the levels of Al, Cd, and F, achieving a synergistic optimization of the quality and safety of summer-autumn tea. The development of this selenium-enriched microbial agent not only expands the application scope of selenium-enriched microorganisms but also provides new insights for the efficient utilisation of summer-autumn tea resources.

This research was supported by the research and developmentprogram of China Se-enriched industry research institute (Grant No. 2024FXZX-01), the Key Research and Development Program ofShaanxi (Grant No. 2024NC-ZDCYL-04-07 and 2025NC-YBXM-240) and the China Agricul-tural Research System of the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry ofAgriculture and Rural Affairs (CARS-19).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: experiments conception and design: Wang W, He B, Liang Y; conducting the experiments: Yang H, Liu J, Gong S, Zhan K; data analysis: Yang H, Liu J, Hao S, Zhou W; manuscript writing: Yang H, Hao S, Qi Y; manuscript reviewing: Wang W, Yu Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Hongbin Yang, Jixian Liu

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Phenotypic characteristics of S-1 in LB medium with and without sodium selenite.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Preparation of S-1 SeNPs.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Content of ester catechin and non-ester catechin in fresh summer-autumn tea leaves after foliar spraying with S-1 SeNPs.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Correlation of aluminium, cadmium, iron, copper, zinc and selenium in fresh summer-autumn tea leaves after foliar spraying with S-1 SeNPs.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yang H, Liu J, Hao S, Zhou W, Zhan K, et al. 2025. Preparation of S-1 bio-nano selenium microbial agent and its effect on improving the quality of summer-autumn young tea shoots. Beverage Plant Research 5: e032 doi: 10.48130/bpr-0025-0019

Preparation of S-1 bio-nano selenium microbial agent and its effect on improving the quality of summer-autumn young tea shoots

- Received: 24 March 2025

- Revised: 25 April 2025

- Accepted: 06 May 2025

- Published online: 22 October 2025

Abstract: Selenium-enriched tea is highly valued for its nutritional and health benefits due to its rich selenium content and various bioactive compounds, such as tea polyphenols, theanine, and catechins. However, the limited availability of selenium resources in soil significantly impedes the development of the selenium-enriched tea industry. Selenium-reducing bacteria, as functional microorganisms capable of efficiently converting inorganic selenium into selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs), play a crucial role in selenium enrichment and stabilization processes in tea plants. In this study, a highly selenium-tolerant strain, Raoultella ornithinolytica S-1, was successfully isolated, demonstrating an exceptional tolerance to sodium selenite concentrations of up to 200 mM. This strain not only efficiently reduces sodium selenite to SeNPs, but also exhibits multiple growth-promoting functions, including nitrogen fixation, phosphorus solubilization, siderophore production, and IAA synthesis. Furthermore, the S-1 bio-nano selenium microbial agent was successfully prepared using mannitol as the carbon source, tryptone as the nitrogen source, and calcium chloride as the inorganic salt at 5 mM sodium selenite and 4% inoculum. Foliar spraying of the microbial agent significantly increased selenium content in the summer-autumn tea fresh leaves, enhancing the levels of refreshing taste compounds, such as soluble sugars, theanine, and other free amino acids. Concurrently, it reduced the content of bitter substances (tea polyphenols and catechins) and harmful elements (aluminium, cadmium, and fluorine), thereby improving the quality and safety of the summer-autumn tea. This study expands the application of selenium-enriched microorganisms and provides an innovative solution for the development of selenium-enriched tea.

-

Key words:

- Selenium-enriched tea /

- Selenium-reducing bacteria /

- Bio-nano selenium /

- Summer-autumn tea /

- Tea quality