-

As temperatures increase, heat stress has become a primary abiotic stress limiting plant growth and development[1]. Heat stress induces a cascade of detrimental physiological effects, including protein denaturation, enzyme inactivation, and membrane lipid peroxidation, disrupting critical metabolic pathways, such as photosynthesis and respiration, and affecting cell membrane permeability, causing electrolyte leakage and water loss[2−4]. In addition, heat stress results in the production of excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can lead to oxidative stress and damage cellular components, including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, further impairing cell function[5].

Plants have evolved a series of physiological and molecular mechanisms to mitigate heat damage and help them adapt to high temperatures[6]. For instance, antioxidant defense pathways, heat stress response pathways, hormone biosynthesis or signaling pathways, as well as transcriptional regulation pathways, play significant roles in the regulation of heat stress responses[7]. The accumulation of non-enzymatic antioxidants like carotenoids and enzymatic antioxidants, such as ascorbate peroxidase (APX), catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD), and superoxide dismutase (SOD), help to clear overproduced ROS and improve the thermotolerance[8]. The enhanced heat tolerance of maize (Zea mays) seedlings was associated with increased expression levels of genes involved in salicylic acid (SA) biosynthesis (PHENYLALANINE AMMONIA-LYASE 1, ZmPAL1; and ISOCHORISMATE SYNTHASE 1, ZmICS1), resulting in elevated endogenous SA levels to scavenge ROS[9]. In addition, transcriptional factors (TFs), such as tryptophan-arginine-lysine-tyrosine (WRKY), myeloblastosis (MYB), NAM, ATAF1/2, and CUC2 (NAC), basic leucine zipper (bZIP), basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH), and heat shock transcription factors (HSFs) have been proven to be closely related to heat tolerance in plants[7,10]. A class HSFA member, HSFA3, enhances thermotolerance including positively regulating expression of HSFA2a in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne)[11]. Overexpression of ZmHSF21 from maize increased POD, SOD, and CAT activities and decreased ROS accumulation in Arabidopsis under heat stress[12]. PlWRKY47 directly binds to the promoter of cytosolic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 2 (PlGAPC2), activates PlGAPC2 expression, inhibits ROS generation, and enhances thermotolerance in herbaceous peony (Paeonia lactiflora)[13]. Similarly, NAC042 is an important NAC TF to regulate thermal memory, and overexpression of NAC042 could induce the expression levels of several HSFs and heat shock proteins (HSPs), thus improving heat tolerance in Arabidopsis[14].

Foliar application of exogenous substances can effectively improve heat tolerance in plants, by maintaining a favorable antioxidative level, membrane stability, and water status[15,16]. Karrikin (KAR), which was initially isolated from smoke from burning plant material, is defined as a kind of novel hormone analog[17]. It has been demonstrated that KAR have a butenolide moiety similar to strigolactone (SL) and have the capacity to promote seed germination, and the subsequent growth and development of seedlings of many plant species under various stress conditions[18−20]. For instance, exogenous application of KAR1 enhanced the germination rate of wheat (Triticum aestivum) seeds under salt stress, and alleviated salt stress damage via maintaining redox and K+/Na+ homeostasis in wheat seedlings[18]. KAR1 can enhance drought tolerance in creeping bentgrass by activating KAR-responsive genes and TFs, promoting proline accumulation and antioxidant capacity, as well as suppressing leaf senescence[20]. KAR1 treatment significantly increased antioxidant enzyme activities, as well as the contents of organic acids and amino acids, and altered the expression of abscisic acid (ABA) signaling genes in oil plant Sapium sebiferum under both drought and salt stress conditions[21]. In addition, KAR1 has been shown to interact with plant hormones, including ABA, SA, cytokinin (CK), gibberellin (GA), auxin (IAA), and ethylene (ETH), to stimulate seed germination and seedling growth under abiotic stresses[21−25]. The KAR receptor KARRIKIN INSENSITIVE2 (KAI2)-mediated signaling positively regulates heat tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana via the activation of HSF-related and HSP-related pathways[26].

Although previous research indicates that KAR1 plays a crucial role in regulating seed germination and abiotic stress tolerance in plants, how KAR1 affects signal transduction, antioxidant defense and stress-responsive gene expression in regulating plant thermotolerance remains largely uncharacterized. Creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera) is an important perennial turfgrass species that is widely used on golf courses, tennis courts, and in landscaping worldwide[27]. However, as a cool-season grass, creeping bentgrass is sensitive to high temperatures, and heat waves during summer months may cause detrimental effects on creeping bentgrass[28]. The purpose of this study is to investigate the effects of the exogenous application of KAR1 on water balance, membrane integrity, antioxidant defense, and expression of stress response and signaling genes under heat stress. This study would be useful in revealing potential KAR1-mediated heat tolerance pathways and provide a solution for mitigating heat damage in creeping bentgrass.

-

Seeds of creeping bentgrass (A. stolonifera cv. 'Penn-A4') were sown in PVC tubes (11 cm in diameter and 25 cm in height) filled with a mixture of potting soil and vermiculite (V:V, 3:1). Plants were established in a growth chamber (XBQH-1, Jinan Xubang, Jinan, Shandong Province, China) for 2 months with 25/20 °C (day/night), 14 h photoperiod, 70% relative humidity, and 650 μmol·m−2·s−1 photosynthetically active radiation. Plants were trimmed weekly to maintain the canopy height at about 3 cm and fertilized once a week with half-strength Hoagland's nutrient solution[29].

KAR1 and stress treatments

-

KAR1 (3-methyl 2H-furo [2,3-c] pyran-2-one) was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, ON, Canada). The KAR1 stock and working solution were prepared according to Shah et al.[21]. For KAR1 treatment, 20 mL of 100 nM KAR1 solution was foliar-sprayed onto the canopy before heat stress and every 5 d during heat stress. The control plants were sprayed with water. The concentration for KAR1 was selected according to the study by Tan et al.[20]. Plants were treated with the following treatments for 20 d: (a) KAR1-treated plants exposed to heat stress (35/30 °C, day/night) (KH), (b) KAR1-treated plants exposed to optimal temperature (25/20 °C, day/night) (KC), (c) water-treated plants exposed to heat stress (CH), and (d) water-treated plants exposed to optimal temperature (CC). Each treatment had four biological replicates.

Determination of relative water content and electrolyte leakage

-

Leaf relative water content (RWC) and electrolyte leakage (EL) were measured at 20 d of heat stress. Leaf RWC was determined using fully expanded leaves, as described by Barrs & Weatherley[30]. Approximately 0.1 g leaf samples were cut and immediately weighed as fresh weight (FW), then immersed in deionized water for 24 h at 4 °C in the dark and immediately weighed as turgid weight (TW). Leaf samples were then dried in an oven at 80 °C for at least 72 h to estimate dry weight (DW). The RWC was calculated following the formula: RWC = (FW − DW)/(TW − DW) × 100%. Leaf EL was determined to indicate cell membrane stability. In brief, about 0.1 g of leaves were placed into centrifuge tubes filled with 35 mL deionized water, and shaken on a shaker at room temperature for 24 h. The initial conductance (Ci) was measured using a conductance meter (Thermo Scientific, Baverly, USA). Leaves were killed by autoclaving at 121 °C for 20 min and then shaken for another 24 h before measuring maximum conductivity (Cmax). EL was calculated as the ratio of Ci to Cmax and expressed as a percentage[31].

Determination of antioxidant enzyme activities

-

About 0.3 g of fresh leave samples were taken at 20 d of heat stress, frozen immediately with liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for antioxidant enzyme activity analysis. Leaf samples were extracted using an extraction solution (50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 1 mM EDTA) with a pre-chilled mortar and pestle. The extractions were centrifuged for 20 min at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C and the supernatants were used to determine antioxidant enzyme activities. APX activity was determined by measuring the decrease in absorbance at 290 nm for 1 min following the protocol described by Nakano & Assada[32]. The 3 mL reaction mixture contained enzyme extract, 100 mM HAc-NaAc (pH 5.8), 0.003 mM EDTA, 10 mM ascorbic acid, and 5 mM H2O2, which initiated the reaction. The activity of SOD was measured according to the method of Beyer & Fridovich[33] with modifications. The reaction medium was composed of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 195 mM L-methionine, 0.003 mM EDTA, 0.06 mM riboflavin, 1.125 mM nitro-blue tetrazolium, and an appropriate amount of leaf extract in a final volume of 3 mL. The reaction mixture was illuminated under light of 13,000 lux for 15 min and the absorbance was determined at 560 nm. CAT activity was determined by measuring the decline of absorbance at 240 nm for 90 s following the procedure of Maehly & Chance[34]. The absorbances were measured using a spectrophotometer (Ultrospec 2100 pro, Biochrom Ltd., Cambridge, UK). Antioxidant enzyme activities were expressed on the basis of per unit protein, which was quantified using the Bradford method and bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis

-

To investigate the effects of KAR1 on regulating gene expression, transcript levels of genes were evaluated using qRT-PCR. Leaf samples were collected at 24 h of heat stress and optimal temperature. Total RNA was extracted using the E.Z.N.A.® Plant RNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, Georgia 30071, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA was then reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara Bio Inc., Nojihigashi 7-4·38, Kusatsu, Shiga 525-0058, Japan). cDNA was amplified using Tag SYBR® Green qPCR Premix (Yugong Biotech, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) on a Roche Light Cycler480 II thermocycler (Roche Diagnostic, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). The primer sequences used in the present study are shown in Supplementary Table S1[20,35]. The relative expression levels of target genes under different treatments were calculated according to the formula 2−ΔΔCᴛ using AsACTIN as the reference gene[36,37].

Statistical analysis

-

The experiment was arranged as split-plot design with temperature treatments as main plots and KAR1 treatments as sub-plots. All data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS 27 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Significant differences among treatments were tested based on Duncan's multiple range test at p < 0.05.

-

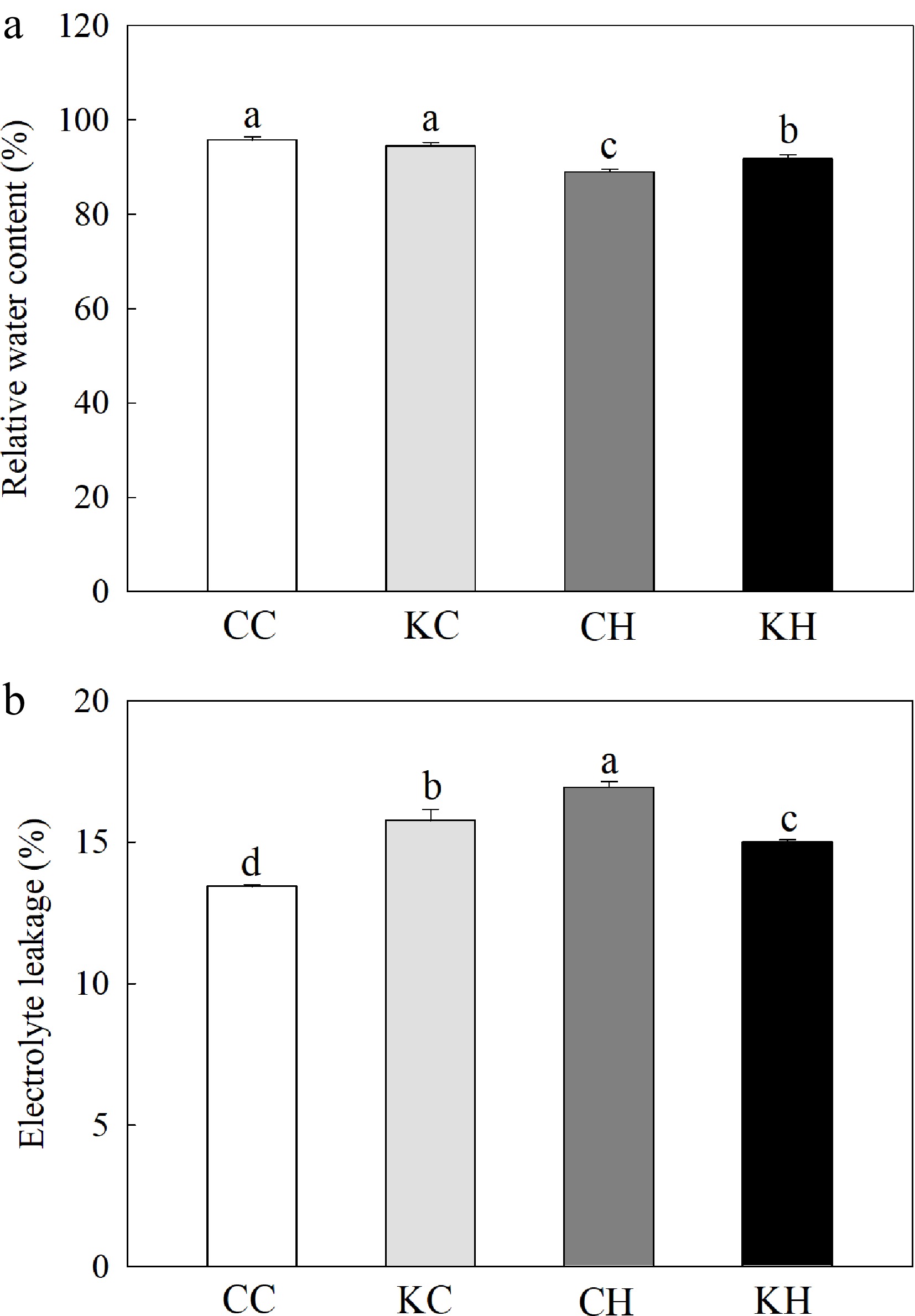

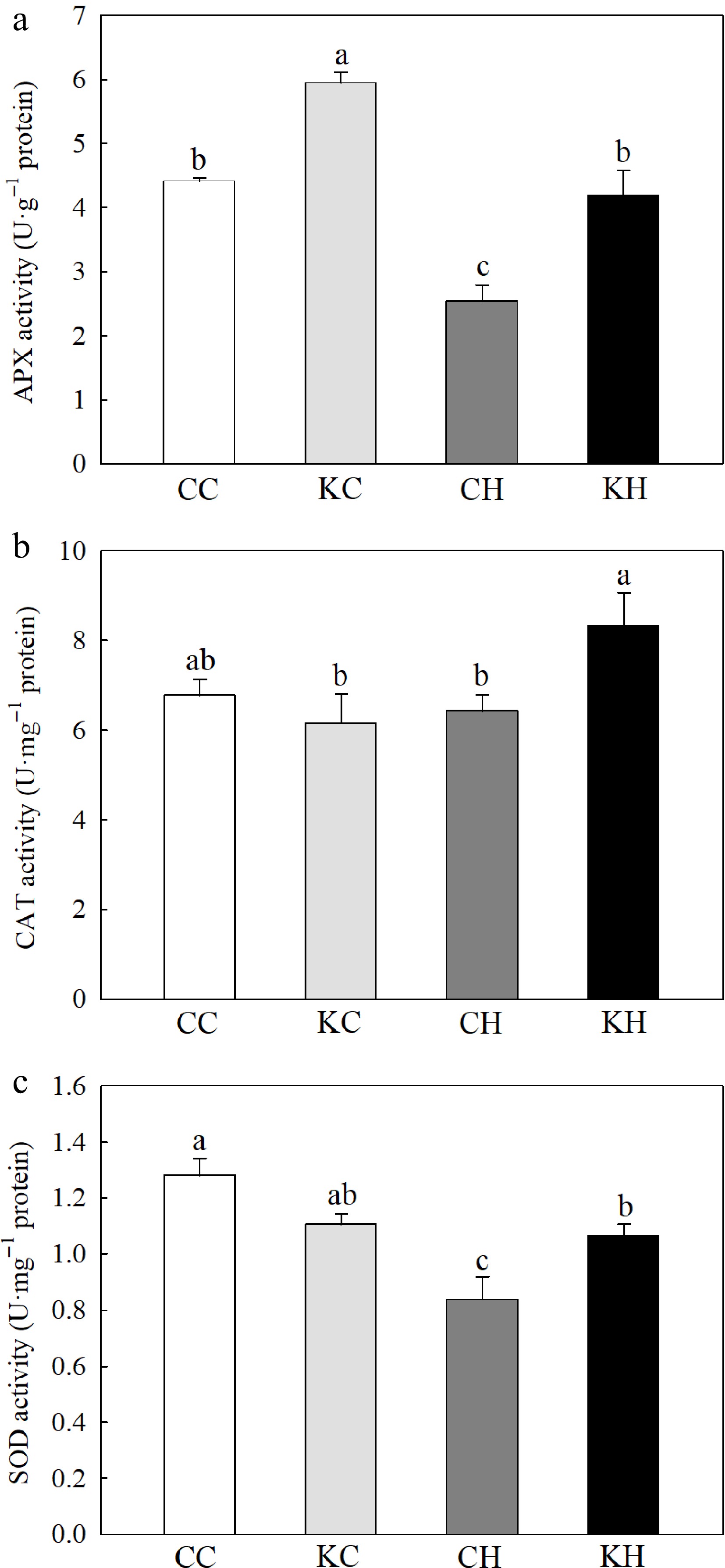

Under optimal temperature, exogenous application of KAR1 had no significant effect on leaf RWC (Fig. 1a). However, KAR1-treated plants had significantly higher (by 3.16%) leaf RWC and 11.44% lower EL than water-treated plants under heat stress (Fig. 1a−b). Heat stress reduced the activities of APX and SOD, while KAR1 treatment significantly increased the activities of APX, CAT, and SOD by 65.63%, 29.69%, and 27.31%, respectively (Fig. 2a−c). Under optimal temperature, no significant differences in the activities of CAT and SOD were found between KAR1-treated and water-treated plants, however, KAR1-treated plants exhibited a 34.69% significantly higher activity of APX compared to water-treated plants (Fig. 2a−c).

Figure 1.

Effects of KAR1 on (a) RWC, and (b) EL in leaves of creeping bentgrass exposed to optimal temperature and heat stress. CC, foliar application of water + optimal temperature; KC, foliar application of 100 nM KAR1 + optimal temperature; CH, foliar application of water + heat stress; KH, foliar application of 100 nM KAR1 + heat stress. Data shown are the mean ± SE of four biological replicates. Bars not sharing a common letter indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 level.

Figure 2.

Effects of KAR1 on (a) APX activity, (b) CAT activity, and (c) SOD activity in leaves of creeping bentgrass exposed to optimal temperature and heat stress. CC, foliar application of water + optimal temperature; KC, foliar application of 100 nM KAR1 + optimal temperature; CH, foliar application of water + heat stress; KH, foliar application of 100 nM KAR1 + heat stress. Data shown are the mean ± SE of four biological replicates. Bars not sharing a common letter indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 level.

Effects of KAR1 on expression levels of antioxidant defense genes under heat stress

-

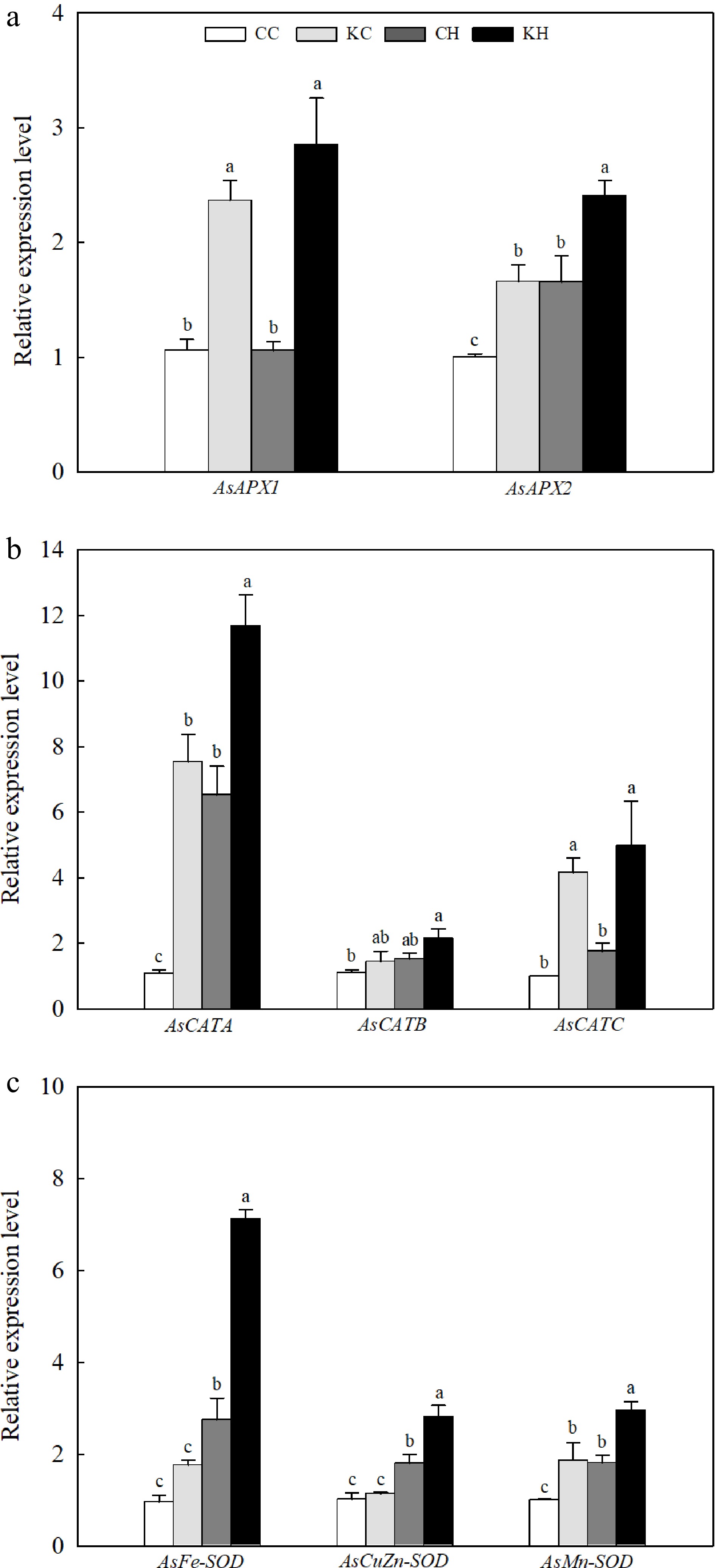

Under optimal temperature, the expression levels of AsAPX1 and AsAPX2 in KAR1-treated plants exhibited a 2.23-fold and 1.66-fold increase, respectively, compared to those treated with water (Fig. 3a). Exogenous application of KAR1 significantly elevated the expression levels of AsAPX1 and AsAPX2 (by 2.70-fold and 1.46-fold) under heat stress (Fig. 3a). Under optimal temperature, KAR1 treatment significantly enhanced the expression levels of AsCATA and AsCATC (by 6.00-fold and 4.16-fold) but had no significant effect on AsCATB (Fig. 3b). Under heat stress, compared with water-treated plants, the expression levels of AsCATA and AsCATC were significantly induced by KAR1 treatment (1.79- and 2.82-fold, respectively) (Fig. 3b). Heat stress significantly increased the expression levels of three SOD-encoding genes (AsFe-SOD, AsCuZn-SOD, and AsMn-SOD), and the expression levels of AsFe-SOD, AsCuZn-SOD, and AsMn-SOD in KAR1-treated plants were significantly higher than those in water-treated plants (Fig. 3c). Under optimal temperature, the expression level of AsMn-SOD was significantly higher in KAR1-treated (1.85-fold) plants after 24 h of heat stress compared to water-treated control (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

Effects of KAR1 on expression of (a) APXs, (b) CATs, and (c) SODs in leaves of creeping bentgrass exposed to optimal temperature and heat stress. CC, foliar application of water + optimal temperature; KC, foliar application of 100 nM KAR1 + optimal temperature; CH, foliar application of water + heat stress; KH, foliar application of 100 nM KAR1 + heat stress. Data shown are the mean ± SE of four biological replicates. Bars not sharing a common letter indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 level.

Effects of KAR1 on expression levels of genes involved in KAR/KL and SL metabolic and signaling pathways under heat stress

-

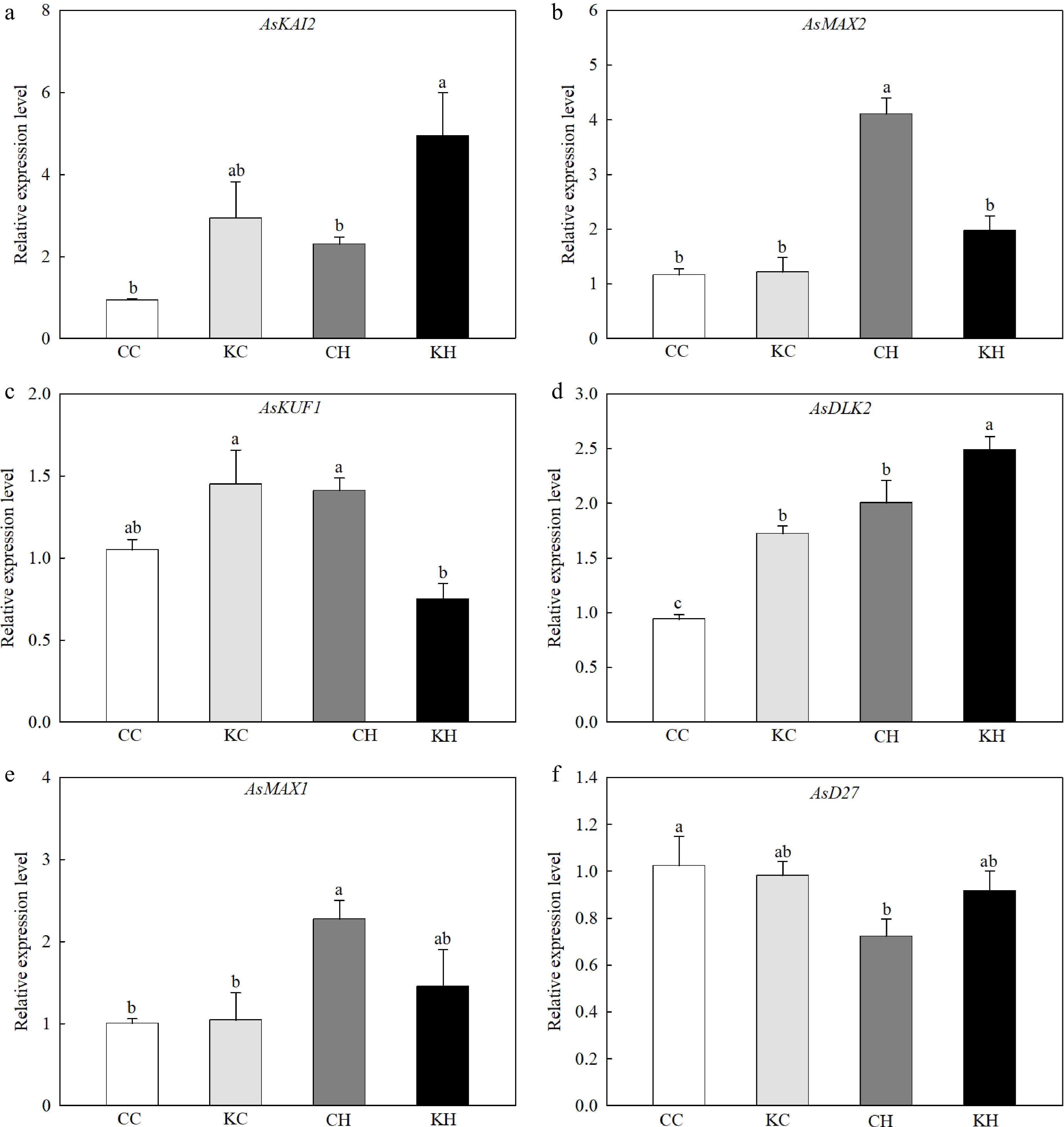

Heat stress significantly increased the transcript levels of KAR/KL signaling transduction genes, such as MORE AXILLARY GROWTH2 (AsMAX2), and DWARF 14-LIKE2 (AsDLK2) (Fig. 4b, d). Exogenous application of KAR1 significantly enhanced the expression levels of KARRIKIN INSENSITIVE2 (AsKAI2) and AsDLK2 (by 2.15-fold and 1.24-fold), and decreased the expression levels of AsMAX2 and KARRIKIN-UP-REGULATED F-BOX1 (AsKUF1) under heat stress (Fig. 4a−d). Heat stress significantly increased the transcript level of the SL biosynthetic gene, AsMAX1, while decreased the transcript levels of the SL biosynthetic gene, AsD27 (Fig. 4e−f). Compared with the water-treated control, the exogenous application of KAR1 enhanced the expression levels of AsD27 and decreased the expression levels of AsMAX1 under heat stress (Fig. 4e−f).

Figure 4.

Effects of KAR1 on expression of (a) AsKAI2, (b) AsMAX2, (c) AsKUF1, (d) AsDLK2, (e) AsMAX1, and (f) AsD27 in leaves of creeping bentgrass exposed to optimal temperature and heat stress. CC, foliar application of water + optimal temperature; KC, foliar application of 100 nM KAR1 + optimal temperature; CH, foliar application of water + heat stress; KH, foliar application of 100 nM KAR1 + heat stress. Data shown are the mean ± SE of four biological replicates. Bars not sharing a common letter indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 level.

Effects of KAR1 on expression levels of genes involved in ABA and SA metabolic and signaling pathways under heat stress

-

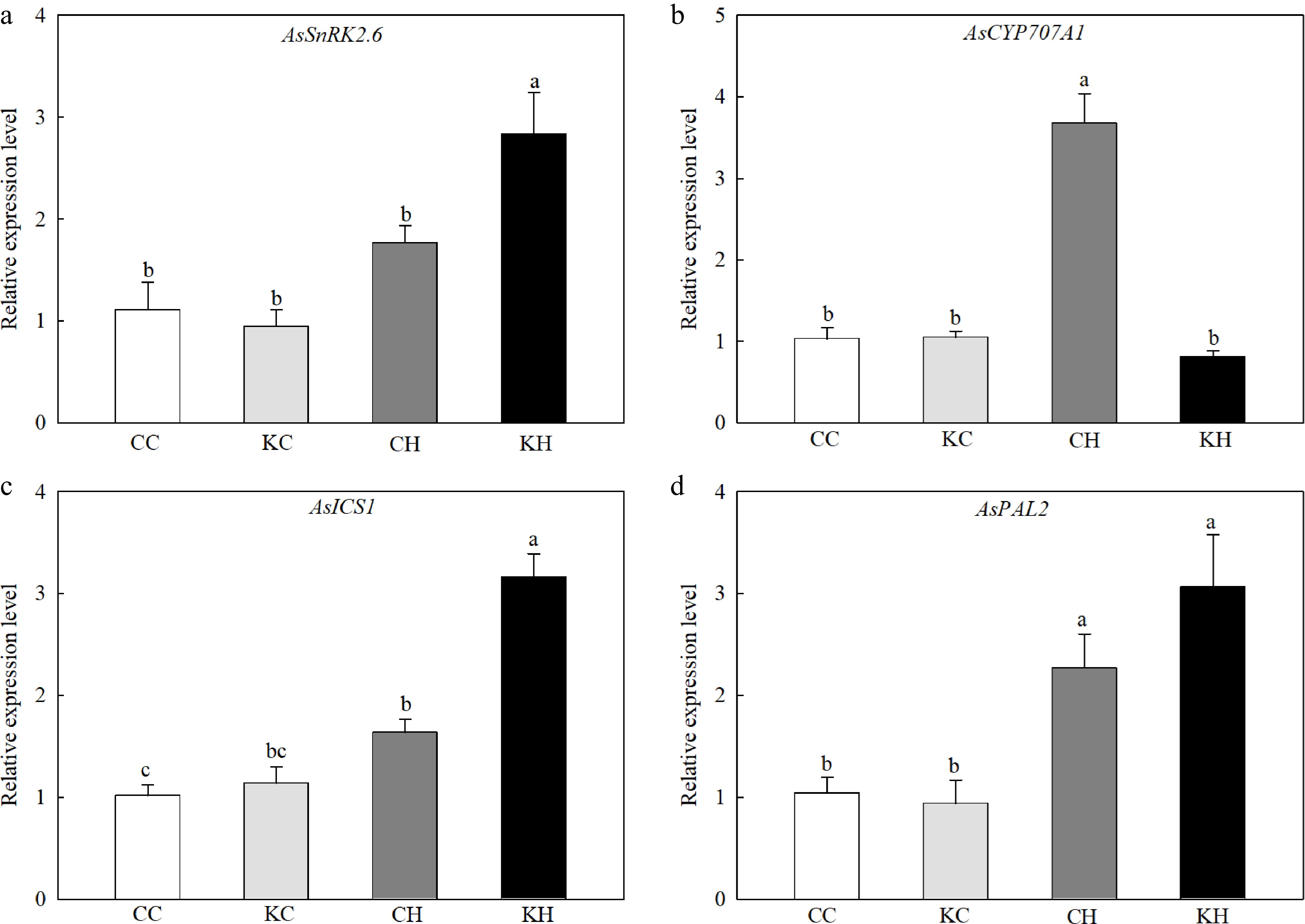

Plants under heat stress exhibited a significant increase in the transcript levels of the ABA catabolism-related gene, CYTOCHROME P450 707A 1 (AsCYP707A1) (Fig. 5b). Exogenous application of KAR1 significantly increased the expression level of the ABA signaling gene, SNF1-RELATED PROTEIN KINASE2.6 (AsSnRK2.6, 1.61-fold) while decreased the expression level of AsCYP707A1) under heat stress (Fig. 5a−b). Heat stress significantly induced the expression levels of two genes involved in SA biosynthesis, AsICS1 and AsPAL2, while exogenous application of KAR1 resulted in a significant increase in the expression level of AsICS1 (1.93-fold) under heat stress (Fig. 5c).

Figure 5.

Effects of KAR1 on expression of (a) AsSnRK2.6, (b) AsCYP707A1, (c) AsICS1, and (d) AsPAL2 in leaves of creeping bentgrass exposed to optimal temperature and heat stress. CC, foliar application of water + optimal temperature; KC, foliar application of 100 nM KAR1 + optimal temperature; CH, foliar application of water + heat stress; KH, foliar application of 100 nM KAR1 + heat stress. Data shown are the mean ± SE of four biological replicates. Bars not sharing a common letter indicate significant differences at p < 0.05 level.

Effects of KAR1 on expression levels of TFs under heat stress

-

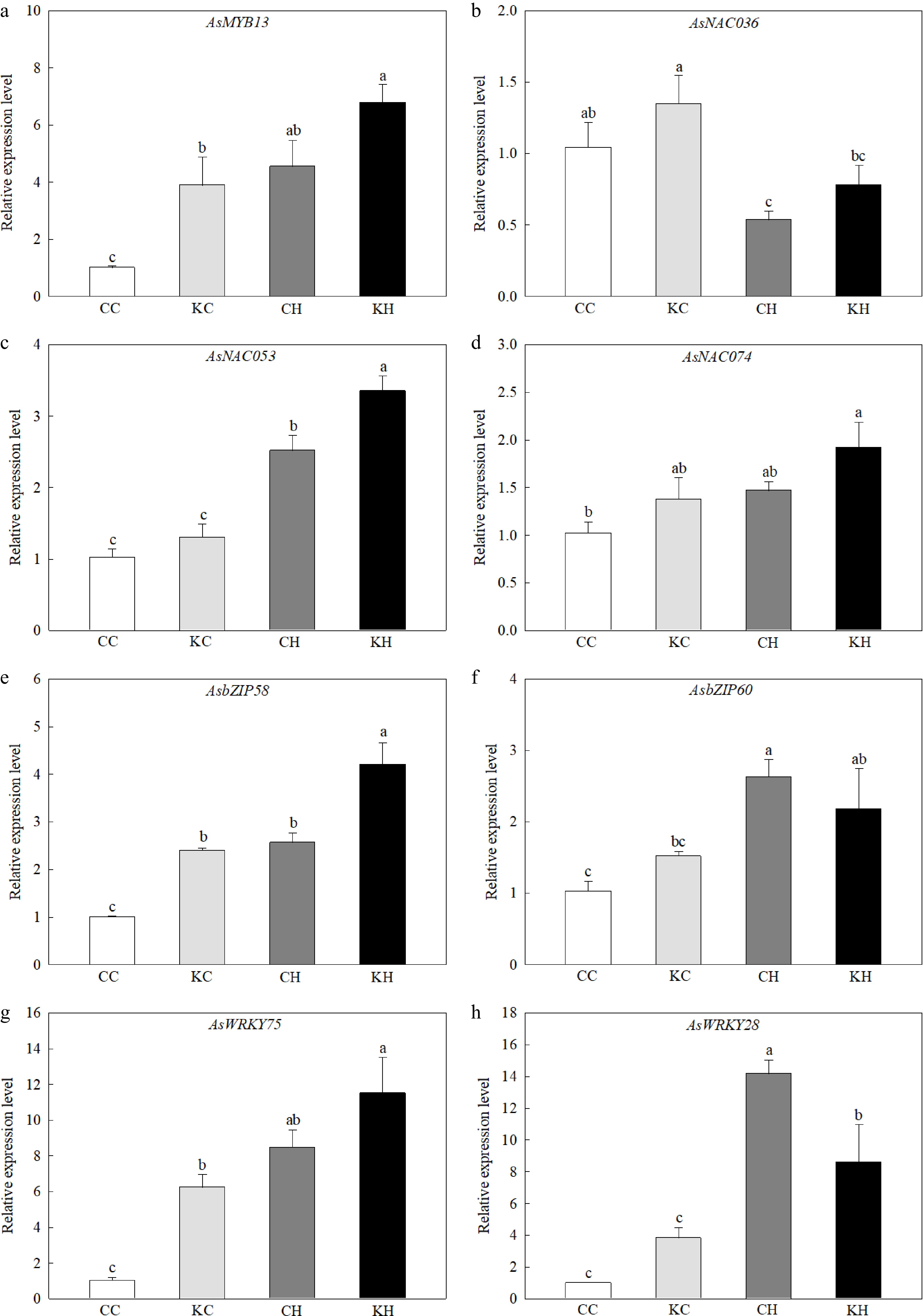

Heat stress significantly increased the expression levels of AsMYB13, AsNAC053, AsbZIP58, AsbZIP60, AsWRKY75, and AsWRKY28 (Fig. 6a, c, e−h). Foliar application of KAR1 significantly increased the expression levels of AsNAC053 and AsbZIP58 (by 1.33-fold and 1.64-fold, respectively), and decreased the expression level of AsWRKY28 (0.61-fold) under heat stress (Fig. 6c, e, h). Under optimal temperature, KAR1-treated plants had significantly higher expression level of AsMYB13, AsbZIP58, and AsWRKY75 (by 3.87-fold, 2.40-fold, and 6.07-fold, respectively) (Fig. 6a, e, g).

Figure 6.

Effects of KAR1 on expression of (a) AsMYB13, (b) AsNAC036, (c) AsNAC053, (d) AsNAC074, (e) AsbZIP58, (f) AsbZIP60, (g) AsWRKY75, and (h) AsWRKY28 in leaves of creeping bentgrass exposed to optimal temperature and heat stress. CC, foliar application of water + optimal temperature; KC, foliar application of 100 nM KAR1 + optimal temperature; CH, foliar application of water + heat stress; KH, foliar application of 100 nM KAR1 + heat stress. Data shown are the mean ± SE of four biological replicates. Bars not sharing a common letter indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Effects of KAR1 on expression levels of HSFs and HSPs under heat stress

-

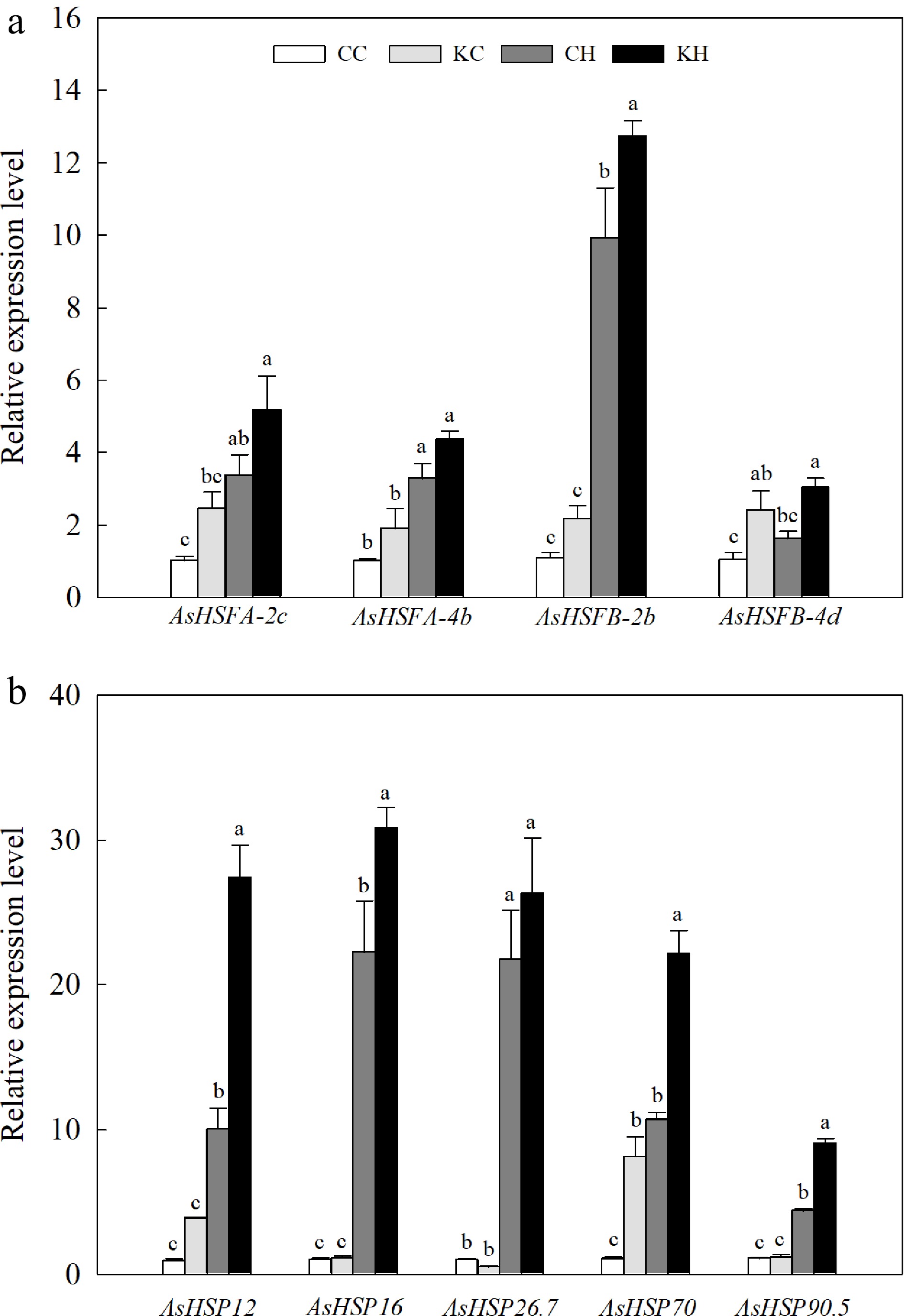

Heat stress significantly increased the expression levels of three HSFs (AsHSFA-2c, AsHSFA-4b, and AsHSFB-2b) and five HSPs (AsHSP12, AsHSP16, AsHSP26.7, AsHSP70, and AsHSP90.5). KAR1-treated plants exhibited significant higher transcription levels of AsHSFB-2b (1.28-fold), AsHSFB-4d (1.87-fold), as well as four HSPs (AsHSP12, 2.73-fold; AsHSP16, 1.39-fold; AsHSP70, 2.07-fold, and AsHSP90.5, 2.06-fold) under heat stress (Fig. 7a, b). Under optimal temperature, application of KAR1 induced the expression levels of AsHSFB-4d and AsHSP70 by 2.32-fold and 7.55-fold, compared to water-treated control, respectively (Fig. 7a, b).

Figure 7.

Effects of KAR1 on expression levels of (a) HSFs and (b) HSPs in leaves of creeping bentgrass exposed to optimal temperature and heat stress. CC, foliar application of water + optimal temperature; KC, foliar application of 100 nM KAR1 + optimal temperature; CH, foliar application of water + heat stress; KH, foliar application of 100 nM KAR1 + heat stress. Data shown are the mean ± SE of four biological replicates. Bars not sharing a common letter indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

-

Heat stress adversely affects plant physiological functions by disrupting normal metabolic processes, inducing excessive ROS accumulation, and causing severe damage to cell membranes, which can ultimately lead to plant death[38]. The results of the present study demonstrated that exogenous application of KAR1 could effectively alleviate heat stress-induced water loss and cell membrane damage in creeping bentgrass, suggesting a positive regulatory effect of KAR1 on water homeostasis and membrane integrity under heat stress. Furthermore, qRT-PCR analysis showed that KAR1-enhanced thermotolerance was associated with transcriptional regulation of multiple pathways, including those involved in antioxidant defense, phytohormone biosynthesis and signaling, key TFs, and heat stress responses.

To counteract the negative impact of excessive ROS induced by stress, plants rely on antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD, APX, and CAT to scavenge ROS and reduce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)[39]. SOD is particularly important as it serves as the first line of defense against oxidative stress by converting O2·− into O2 and H2O2[39−41]. APX then further reduces H2O2 to H2O to decrease its toxicity for the cell[39−41]. In this study, high-temperature stress reduced SOD and APX activities in creeping bentgrass, while foliar application of KAR1 significantly increased the activities of both SOD and APX. Shah et al.[21] also found that KAR1 could enhance the activities of SOD and APX in Sapium sebiferum plants under salt and osmotic stresses. In addition, exogenous KAR1 induced significantly enhanced expression levels of antioxidant enzyme encoding genes including AsAPX1, AsAPX2, AsCATA, AsCATB, AsCATC, AsFe-SOD, AsCuZn-SOD, and AsMn-SOD under heat stress (Fig. 3). This suggested that KAR1-regulated antioxidant defense could contribute to improved heat tolerance in creeping bentgrass.

Previous studies have shown that KAR/KL signal transduction is critical for plant growth and survival under abiotic stress[20,42]. Signal transduction via KAI2 required the binding of an F-box protein known as MAX2 to facilitate the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of members of the SUPPRESSOR OF MAX2-LIKE (SMXL) protein family, including SMAX1 and SMAX2[23]. Up-regulated KAI2 expression activates a positive response mechanism under salt stress, whereas reduced KAI2 function results in pronounced growth abnormalities in kai2-mutant plants[42]. DLK2 and KUF1 are commonly used as transcriptional indicators for KAR/KL signaling as their expressions respond strongly to KAR treatment or the distruction of core KAR/KL signaling components[43]. DLK2, a KAI2 paralog, exhibits transcriptional up-regulation in response to SLs[44]. KUF1 is considered to hinder the conversion of KAR1 into a functional ligand for KAI2 and the biosynthesis of KAR/KL[45]. In the present study, foliar application of KAR1 significantly increased the transcript levels of AsKAI2 and AsDLK2 and decreased the transcript levels of AsKUF1 under heat stress (Fig. 4a, c, d), which was consistent with previous research that KAR1 may promote the heat tolerance of creeping bentgrass by activating KAR/KL signaling pathway[20,21].

Phytohormones, such as ABA, SL, SA, JA, and ETH, are actively involved in plant response to heat stress[46]. Previous studies have shown that KAR-regulated plant growth and development under salt/drought stress was related to phytohormonal biosynthesis, catabolism, and signaling pathways[25,42]. In the present study, exogenous application of KAR1 increased the expression levels of AsD27 while decreasing the expression levels of AsMAX1 and AsMAX2 in heat-stressed plants (Fig. 4b, e, f), suggesting an interaction between KAR/KL and SL signaling under heat stress in creeping bentgrass.

The KAR/KL signal transduction pathway has been demonstrated to enhance ABA sensitivity through multiple regulatory mechanisms, including the modulation of key genes involved in ABA biosynthesis and signal transduction pathways[17,21]. In the present study, KAR1 treatment significantly elevated the expression of the ABA signaling gene AsSnRK2.6 and decreased the expression of the ABA catabolic gene AsCYP707A1 (Fig. 5a−b), indicating that KAR1 might inhibit ABA catabolism, leading to accumulated ABA, and promote ABA signaling to enhance heat tolerance in creeping bentgrass. SA is also a hormone that plays a crucial role in promoting plant heat tolerance[47]. ICS is a key enzyme in SA synthesis, and the salicylic acid induction deficient 2-1 (sid2-1) mutant of Arabidopsis, which lacks functional ICS1, accumulated higher levels of ROS under heat stress compared to WT plants[48]. In this study, exogenous KAR1 significantly increased the expression of the SA biosynthesis gene (AsICS1) (Fig. 5c), suggesting that KAR1 application may activate SA biosynthesis and affect heat tolerance in creeping bentgrass.

TFs are classified into various families, including MYB, NAC, WRKY, and bZIP, which have been extensively documented to play critical roles in regulating plant growth, development, and stress responses[49]. NAC TF is one of the largest families of plant-specific TFs that have been shown to regulate seed and embryo development, shoot apical meristem formation, cell division, and leaf senescence[50]. In addition, many NAC genes are involved in plant responses to abiotic stresses, such as drought, salinity, cold, and heat stresses[50]. For instance, overexpression of ZmNAC074 increased antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD and CAT) and proline content, while decreasing ROS accumulation and malondialdehyde content, conferring enhanced heat tolerance in Arabidopsis[51]. WRKY TFs may have similar functions and play a key role in plant growth, development, and biotic and abiotic stresses in different plant species[52]. Several WRKY members, including WRKY25, WRKY26, WRKY40, and WRKY70, showed increased expression under heat stress, and overexpression of LlWRKY22 increased heat tolerance in Lilium longiflorum[53]. Similarly, studies in model species such as Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa have shown that bZIP family members play essential roles in plant responses to abiotic stresses[54]. For instance, OsZIP58 and TaZIP60 have been demonstrated to regulate thermotolerance in plants[54,55]. In this study, exogenous application of KAR1 up-regulated the expression of three NAC TFs (AsNAC036, AsNAC053 and AsNAC074), AsMYB13, AsbZIP58, and AsWRKY75 under heat stress, which indicated a positive association of specific TFs with KAR1-enhanced heat tolerance in creeping bentgrass.

HSPs function as molecular chaperones to facilitate the repair of denatured/misfolded proteins, which are significantly induced by heat stress[56]. For instance, overexpression ZjHsp70 has been shown to enhance heat tolerance in Arabidopsis, as evidenced by reduced malondialdehyde content and increased antioxidant enzyme activities[57]. HSFs are crucial components of the transcriptional regulatory networks that control the transcription of heat-HSPs[58]. In potato (Solanum tuberosum), StHsfB5 functions as a coactivator that enhances heat resistance by directly stimulating the expression of HSPs, including sHsp17.6, sHsp21, sHsp22.7, and Hsp80[59]. In addition, previous research has shown that HSFA family members serve as primary regulators of plant thermotolerance[56,59]. For instance, in Arabidopsis, AtHSFA6b acts as a downstream regulator of the ABA-mediated stress response and positively regulates Arabidopsis heat tolerance[60]. Furthermore, transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) plants overexpressing FaHSFA2a exhibited significantly reduced cell membrane damage and leaf senescence under heat stress[56]. In this study, foliar application of KAR1 significantly upregulated the expression levels of HSFs (AsHSFB-2b and AsHSFB-4d) and HSPs (AsHSP12, AsHSP16, AsHSP70, and AsHSP90.5) in creeping bentgrass under heat stress (Fig. 6), suggesting that KAR1 application may enhance thermotolerance through a regulatory mechanism involving specific HSFs, which subsequently activate the transcription of downstream HSPs, thereby facilitating the maintenance of protein homeostasis and cellular functions under heat stress.

-

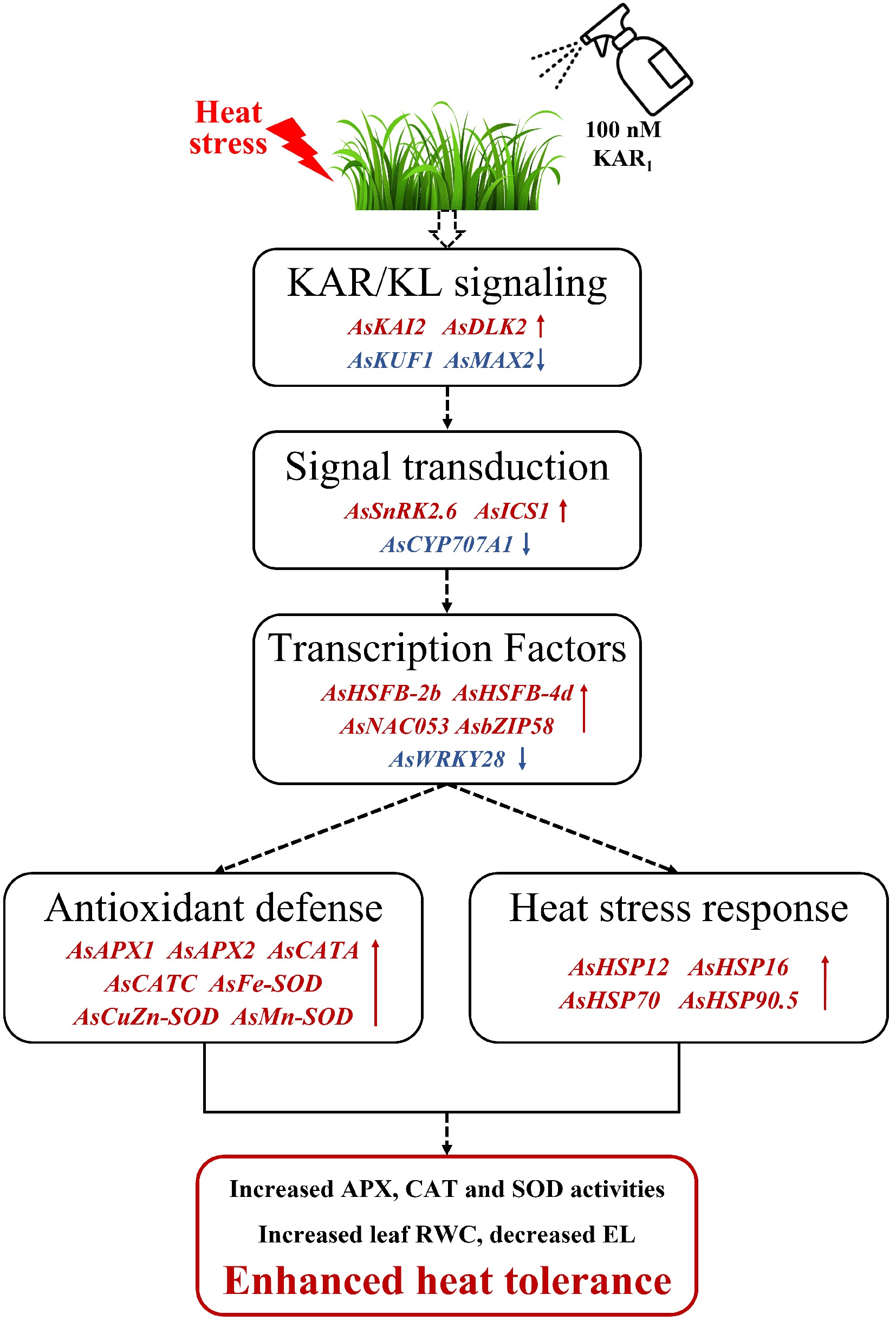

Heat stress significantly reduced in leaf RWC and increased electrolyte leakage in creeping bentgrass. Exogenous application of 100 nM KAR1 effectively mitigated heat-induced stress damage, as demonstrated by improved maintenance of water balance and membrane stability, along with enhanced antioxidant enzyme activities. KAR1-mediated thermotolerance was associated with the regulation of key genes involved in multiple physiological pathways, including heat stress response, antioxidant defense, phytohormone biosynthesis, and signaling, as well as KAR/KL signaling and TFs (Fig. 8). These findings suggested that KAR1 might serve as an effective bioregulator for enhancing heat tolerance of cool-season turfgrass, providing a new perspective for cool-season lawn maintenance under high-temperature conditions.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram illustrating the mechanism of KAR1 enhances the heat tolerance of creeping bentgrass. Under heat stress, foliar application of KAR1 up-regulated the expression of KAR/KL signal transduction genes (AsKAI2, AsDLK2), hormone biosynthesis and signaling genes (AsSnRK2.6, AsICS1), transcription factors (AsHSFB-2b, AsHSFB-4d, AsNAC053, AsbZIP58), antioxidant defense genes (AsAPX1, AsAPX2, AsCATA, AsCATC, AsFe-SOD, AsCuZn-SOD, AsMn-SOD), and heat shock proteins (AsHSP12, AsHSP16, AsHSP70, AsHSP90.5), while down-regulated the expression of KAR/KL signal transduction genes (AsMAX2, AsKUF1), phytohormone catabolism gene (AsCYP707A1), and transcription factor (AsWRKY28), resulting in enhanced heat tolerance (increased leaf RWC, decreased EL, and increased activities of APX, CAT and SOD) of creeping bentgrass.

This research was supported by Jiangsu Funding Program for Excellent Postdoctoral Talent to Zhenzhen Tan (2024ZB830) and the Central Finance Forestry Science and Technology Promotion Demonstration Funding Project (Su [2023] TG1).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhang X, Yang Z, Tan Z; data collection: Wang Y, Han Y, Zhu M, Li X; analysis and interpretation of results: Wang Y, Tan Z, Zhang X; draft manuscript preparation: Wang Y; manuscript revision: Zhang X, Tan Z, Yang Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Yiting Wang, Zhenzhen Tan

- Supplementary Table S1 Primer sequences used in qRT-PCR analysis.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang Y, Tan Z, Han Y, Zhu M, Li X, et al. 2025. Foliar application of Karrikin1 enhanced heat tolerance of creeping bentgrass by activating antioxidant defense, signaling transduction, and stress responsive pathways. Grass Research 5: e016 doi: 10.48130/grares-0025-0013

Foliar application of Karrikin1 enhanced heat tolerance of creeping bentgrass by activating antioxidant defense, signaling transduction, and stress responsive pathways

- Received: 10 January 2025

- Revised: 23 March 2025

- Accepted: 21 April 2025

- Published online: 04 June 2025

Abstract: Karrikin (KAR), a recently identified plant growth regulator, functions in seed germination, seedling development, and abiotic stress adaptation. Despite its recognized biological functions, the regulatory role and underlying mechanisms of KAR in mediating heat tolerance of turfgrass remain largely unknown. In the present study, creeping bentgrass plants were treated with or without KAR1 (100 nM) and subjected to two temperature treatments (25/20 and 35/30 °C, day/night) for 20 d. Physiological parameters, antioxidant enzyme activities, as well as expression levels of genes involved in stress signaling and heat stress responses were analyzed. The results showed that heat stress caused negative effects on creeping bentgrass, including leaf water loss and membrane lipid peroxidation. Exogenous application of KAR1 alleviated heat-induced damage on creeping bentgrass, resulting in improved leaf relative water content, decreased leaf electrolyte leakage, and increased antioxidant enzyme activities (including ascorbate peroxidase, catalase, and superoxide dismutase). In addition, KAR1 treatment up-regulated the expression of KAR/KAI2-Ligand signal transduction genes (AsKAI2, AsDLK2), phytohormone biosynthesis and signaling genes (AsSnRK2.6, AsICS1), transcription factors (AsNAC053, AsbZIP58, AsHSFB-2b, AsHSFB-4d), antioxidant defense genes (AsAPX1, AsAPX2, AsCATA, AsCATC, AsFe-SOD, AsCuZn-SOD, AsMn-SOD), and heat shock proteins (AsHSP12, AsHSP16, AsHSP70, AsHSP90.5) under heat stress. These results suggested that KAR1 might act as an effective agent to enhance the heat tolerance of creeping bentgrass, which provides a new perspective on cool-season lawn maintenance.

-

Key words:

- Karrikin1 /

- Creeping bentgrass /

- Heat tolerance /

- Antioxidant defense /

- Stress signaling