-

Galanthamine (GAL), an isoquinoline alkaloid characterized by a structurally complex and synthetically challenging framework, consists of an aromatic ring, a heterocyclic ring, a cyclohexenol ring, and an azepine ring[1]. GAL is recognized as a well-tolerated and effective symptomatic treatment for Alzheimer's disease (AD). It improves cognitive function and daily living activities in patients with mild to moderate AD, thereby occupying a unique and significant position among anti-AD therapeutics. In recent years, the intensifying aging population has led to a rapid increase in the number of AD patients, posing a significant challenge to the supply of GAL[2]. However, in a wider context, the yield of GAL and its analogues from plant extraction is exceedingly low, approximately 0.05%–0.2% in the bulbs of the Narcissus genus, which falls far short of market demand. Moreover, due to decades of overharvesting of economically valuable species within the Narcissus genus and their low survival rates, these plants now face serious threats in their natural habitats. Therefore, it is imperative to develop alternative methods and sustainable production systems for GAL.

Recent advancements in genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics have provided new insights into the complex organization of biosynthetic pathways. The elucidation of pathways for several well-characterized compounds, such as tripterygium glycosides, oleanolic acid, and paclitaxel, has enabled the potential for their heterologous synthesis[3]. Significant progress has been demonstrated in the heterologous biosynthesis of natural products, with compounds including artemisinin (25 g/L), taxadiene (1 g/L), and tanshinone diene (3.5 g/L) reaching gram-scale production titers in yeast[4]. GAL, valued for its pronounced efficacy against AD, has stimulated substantial research interest in securing its sustainable and renewable supply[5]. Through extensive research, substantial progress has been made in the heterologous synthesis of GAL. Recently, the biosynthetic pathway genes for GAL and its analogues have been elucidated. Concurrently, significant advances have been achieved in its total synthesis, with numerous distinct strategies now established[3]. This review summarizes recent advances in the biosynthesis, total synthesis, and pharmacological activities of GAL and its analogs. It is our expectation that the present consolidation of knowledge on GAL will act as a catalyst for transcending the present limitations in the cognition of galantamine, and for guiding research toward a seminal breakthrough.

-

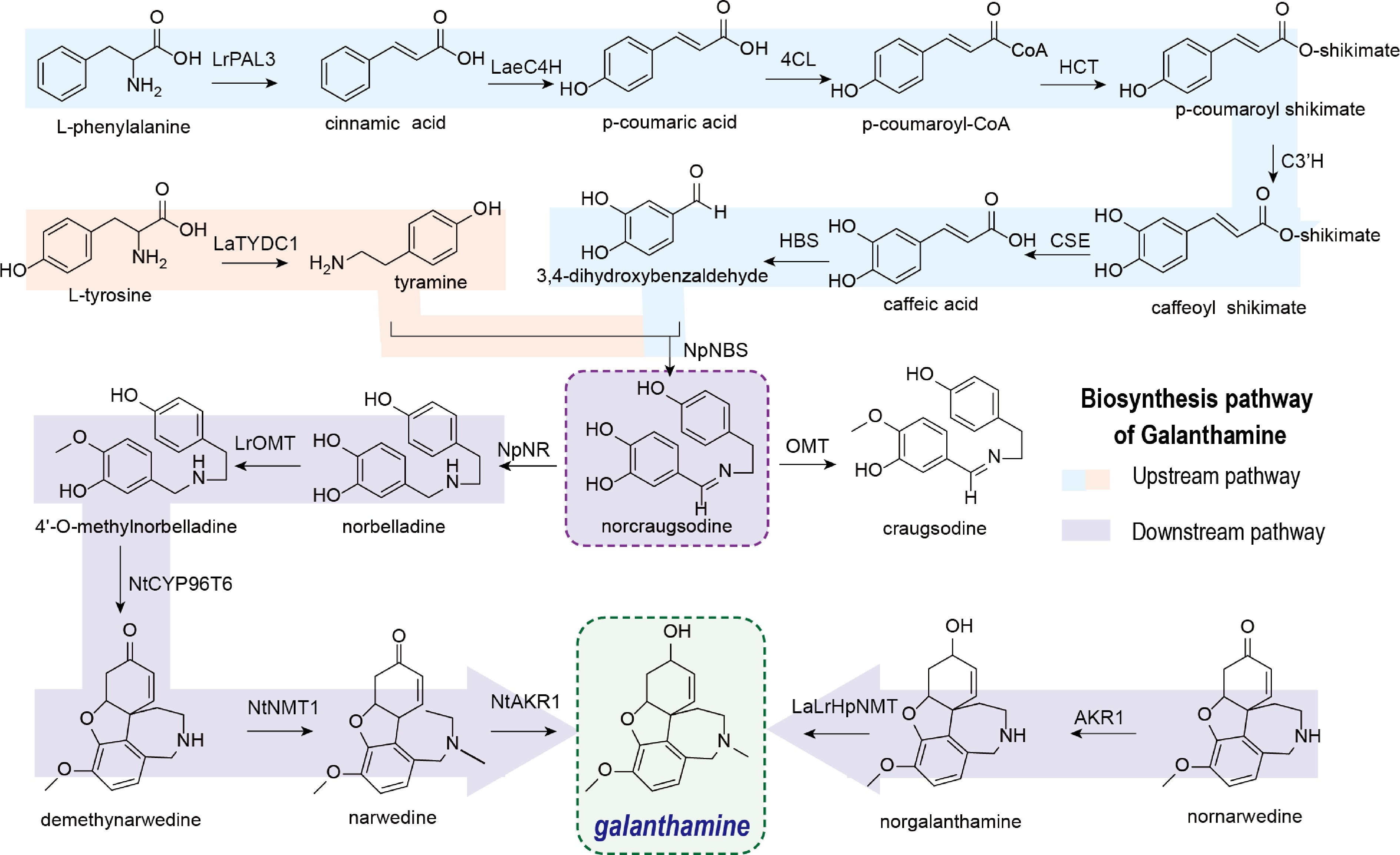

The biosynthetic pathway of GAL is generally divided into two stages. Initially, the key intermediate norbelladine is formed via the condensation of 3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde (3,4-DHBA) (derived from L-phenylalanine), and tyramine (derived from L-tyrosine). Subsequently, norbelladine undergoes enzymatic modifications to yield various Amaryllidaceae alkaloids (AAs), including GAL[6].

Biosynthesis of GAL

-

The upstream biosynthetic pathway of GAL originates from the precursor molecules L-phenylalanine and L-tyrosine, and involves multiple key enzymatic steps[7]. The upstream biosynthetic pathway generates not only norbelladine—an essential intermediate in GAL biosynthesis—but also branch-point metabolites that contribute to the formation of other aromatic amino acid-derived compounds. Consequently, the identification and functional characterization of the enzymes in this pathway are crucial for elucidating the complete GAL biosynthetic machinery and will facilitate the development of heterologous production platforms (Fig. 1)[8].

In the upstream biosynthetic pathway of GAL, tyrosine decarboxylase (TYDC) catalyzes the conversion of L-tyrosine to tyramine. This reaction represents the first committed step in the biosynthesis of quinoline alkaloids[9]. Furthermore, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) catalyzes the deamination of L-phenylalanine to cinnamic acid. This reaction constitutes the first committed step in the phenylpropanoid pathway. Cinnamic acid is then hydroxylated at the 4-position by cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H), a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (CYP73A), to yield p-coumaric acid[7,10,11]. Subsequently, p-coumaric acid is activated to p-coumaroyl-CoA by 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL). p-Coumaroyl-CoA then serves as the substrate for hydroxycinnamoyl transferase (HCT), which catalyzes its conversion to p-coumaroyl shikimate[12]. Subsequently, p-coumaroyl shikimate is hydroxylated by p-coumaroyl ester 3'-hydroxylase (C3'H) to yield caffeoyl shikimate. This intermediate is then hydrolyzed by caffeoyl shikimate esterase (CSE) to produce caffeic acid[13,14]. In a parallel branch of the pathway, 3,4-DHBA and tyramine undergo a condensation reaction catalyzed by noroxomaritidine synthase (NBS), forming norcraugsodine. Finally, norcraugsodine is reduced by noroxomaritidine/norcraugsodine reductase (NR) to yield the key intermediate, norbelladine[7].

Recent investigations have led to the identification of key upstream genes involved in the GAL biosynthetic pathway. Consequently, the amino acid sequences of several pivotal enzymes have been cloned from diverse Amaryllidaceae species, and their catalytic functions have been experimentally validated. For example, a 2018 study by Li et al. identified two genes integral to GAL biosynthesis: LrPAL3, which catalyzes the deamination of L-phenylalanine to yield trans-cinnamic acid, and LrC4H, which catalyzes the regioselective para-hydroxylation of trans-cinnamic acid to produce p-coumaric acid[11]. In 2019, Wang et al. demonstrated that LaTYDC1 participates in the biosynthesis of GAL in Lycoris aurea and confirmed its catalytic function in converting tyrosine to tyramine[9]. Recent research by Zhang et al. has advanced the understanding of Amaryllidaceae alkaloid biosynthesis. In a 2020 study, the group employed transcriptomic and differential gene expression analyses to identify seven genes implicated in the GAL biosynthetic pathway. In 2021, Li et al. treated Lycoris longituba with exogenous methyl jasmonate (MeJA) to investigate its effect on GAL biosynthesis. Integrated analysis of transcriptomic and metabolomic data revealed that MeJA upregulates the GAL biosynthetic pathway[15]. In 2024, Karimzadegan et al. utilized the Leucojum aestivum transcriptome to validate four genes implicated in the GAL biosynthetic pathway, including cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H) and coumaroyl ester 3'-hydroxylase (C3'H). Among these, LaeC4H and LaeC3'H exhibit high sequence conservation with their orthologs previously characterized in other species[7]. Similarly, Singh et al. demonstrated that noroxomaritidine synthase (NpNBS) catalyzes the condensation of tyramine and 3,4-DHBA to form norbelladine[16]. In 2022, Tousignant et al. identified a LaNBS protein through transcriptomic analysis of Leucojum aestivum and validated its ability to to catalyze the condensation between 3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde and tyramine to form norcraugsodine. Concurrently, they determined through fluorescent localization that LaNBS resides in the cytoplasm[17]. Although the condensation of tyramine and 3,4-DHBA, catalyzed by noroxomaritidine synthase (NBS), followed by noroxomaritidine/norcraugsodine reductase (NR), yields norbelladine, the reaction efficiency remains low. This limitation is primarily due to the incomplete elucidation of the catalytic mechanisms governing both NBS and NR. In 2023, Majhi et al. demonstrated through subcellular localization studies that both NBS and NR are localized in the cytoplasm and nucleus. Furthermore, co-expression experiments in yeast revealed that NBS and NR exhibit mutual interaction[18]. Combined, NBS and NR catalyze the conversion of tyramine and 3,4-DHBA into norcraugsodine, which is subsequently reduced to produce norbaldine. This two-step enzymatic cascade results in a reaction efficiency that is 12-fold higher than that achieved with NpNBS alone.

The downstream metabolic pathway of galantamine initiates with norbelladine. This intermediate is first methylated by S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent 4'-O-methyltransferase (OMT) to yield 4'-O-methylnorbelladine[19]. Subsequently, 4'-O-methylnorbelladine undergoes oxidative coupling catalyzed by cytochrome P450 enzymes of the CYP96T subfamily. This reaction can proceed via para-para' (p-p'), para-ortho' (p-o'), or ortho-para' (o-p') coupling modes, generating distinct Amaryllidaceae alkaloid skeletons. (Fig. 2)[20]. Among these, pathway p-o' yields demethylnarwedine, a key precursor to GAL. This intermediate is primarily reduced to narwedine by the concerted action of NMT and an aldehyde-ketone reductase (AKR). Alternatively, demethylnarwedine can be first reduced by AKR to form norgalanthamine, which is subsequently methylated by NMT to yield GAL[6].

O-methyltransferases represent one of the most extensively studied classes of tailoring enzymes and play a crucial role in the structural modification of diverse natural products. The enzyme responsible for the 4'-O-methylation step in the GAL biosynthetic pathway was characterized relatively early. In 2014, Kilgore et al. cloned and functionally characterized NpN4OMT from Narcissus pseudonarcissus. Subsequently, Li et al. characterized an ortholog, LrOMT, from Lycoris radiata[19,21]. Cytochromes P450 (P450s) catalyze a diverse array of oxidative reactions and are pivotal in the biosynthesis of numerous complex plant alkaloids. This enzyme superfamily also mediates most of the multi-step transformations in the GAL pathway[22]. A critical reaction involves the oxidative coupling of the key intermediate 4'-O-methylnorbelladine, which is catalyzed by CYP96T subfamily enzymes. This catalysis proceeds via p-p', p-o', or o-p' coupling modes to generate distinct AAs skeletons[6,23]. In 2024, Mehta et al. revealed the biosynthetic pathway of AAs through developmental gradient analysis, demonstrating that NtCYP96T6 catalyzes the para-ortho' coupling of 4'-O-methylnorbelladine and identifies NtNMT1 and NtAKR1 via co-expression analysis as the minimal core gene set for GAL biosynthesis[6]. Although the core biosynthetic pathway of GAL has been largely deciphered, research in this area remains active. For instance, Liu et al. conducted a comparative functional analysis of four distinct CYP96T enzymes in Lycoris aurea, elucidating their specific roles in mediating regioselective C-C phenol coupling reactions[20]. Their findings indicated that LauCYP96T catalyzes distinct regiospecific C-C phenol coupling reactions. In the GAL biosynthetic pathway, cytochrome P450 enzymes (P450s) are essential for these oxidative steps, and their activity is strictly dependent on electrons supplied by a redox partner, cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR). Supporting this, Wu et al. identified three functional CPR isoforms (LrCPRs) in Lycoris radiata and confirmed their electron transfer capability in vitro. This discovery provides critical genetic elements for reconstructing the GAL pathway in a heterologous system[8]. Following the identification of a minimal gene set for GAL biosynthesis by Mehta et al., and subsequent work by Liyanage et al. revealed the existence of alternative biosynthetic routes[6,24]. Their research identified a novel N-methyltransferase and demonstrated that the intermediate nornarwedine can undergo divergent enzymatic processing: (i) reduction by aldo-keto reductase 1 (AKR1) to yield norgalanthamine, followed by methylation by coclaurine-N-methyltransferase (CNMT) to form GAL; or (ii) methylation by the newly identified N-methyltransferase (NMT) to form narwedine, followed by reduction by an AKR to yield GAL. These findings provide significant new insights into the plasticity of GAL biosynthesis. Furthermore, the plant Nicotiana benthamiana possesses a comprehensive cellular machinery—including essential cofactors, subcellular compartments, and chaperone systems—that supports the efficient expression and proper folding of complex plant-derived enzymes, making it a suitable heterologous host for pathway reconstitution studies. In 2025, Lamichhane et al. successfully reconstituted the biosynthetic pathway of AAs in Nicotiana benthamiana via transient expression, enabling the production of multiple AAs, including GAL. Furthermore, they demonstrated that two cytochrome P450 enzymes, LaCYP96T1 and LaCYP96T2, can concurrently catalyze three distinct regio-selective C-C coupling reactions[25]. Despite extensive efforts, the complete heterologous biosynthesis of GAL in yeast has not yet been achieved. These studies elucidated key enzymatic steps and refined the GAL biosynthetic pathway, culminating in its successful heterologous reconstitution. The multidisciplinary approaches developed herein, including metabolic engineering and transient expression, provide a paradigm for elucidating the biosynthesis of other high-value natural products, such as specific alkaloids and lignans. Furthermore, this research establishes a foundational framework for the sustainable biotechnological production and industrial translation of these compounds.

Biosynthesis of GAL analogues

-

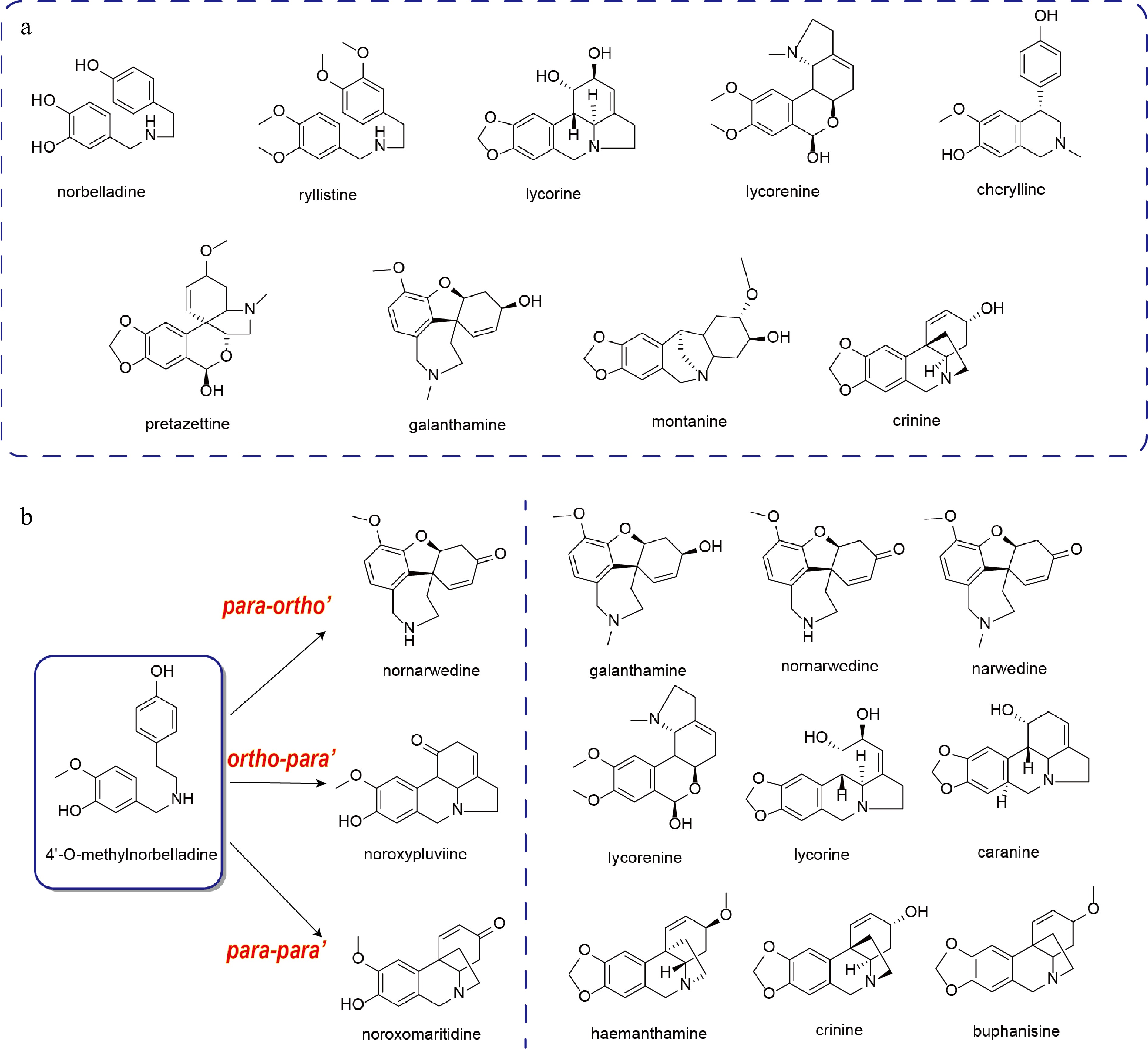

AAs represent a structurally diverse family of natural products, which have garnered significant research interest due to their wide range of pharmacological activities[26]. AAs are systematically classified according to their core biosynthetic precursors, characteristic carbon skeletons, and distinct ring systems. Major structural types within this family include norbelladine-, lycorine-, lycorenine-, cherylline-, pretazettine-, galanthamine-, crinine-, and montanine-type alkaloids (Fig. 2a)[26]. The biosynthetic pathways of AAs share a common route up to the formation of the key intermediate norbelladine. Downstream of norbelladine, the pathway diverges, and distinct AAs, such as GAL, are produced through the action of specific enzymes[27]. Among them, haemanthamine and lycorine have garnered significant research interest due to their pronounced pharmacological activities. Consequently, the biosynthetic pathways of these compounds have been extensively investigated. However, the biosynthetic pathways of many other AAs remain largely uncharacterized and are primarily inferred from structural analogies, thus presenting a significant avenue for future research.

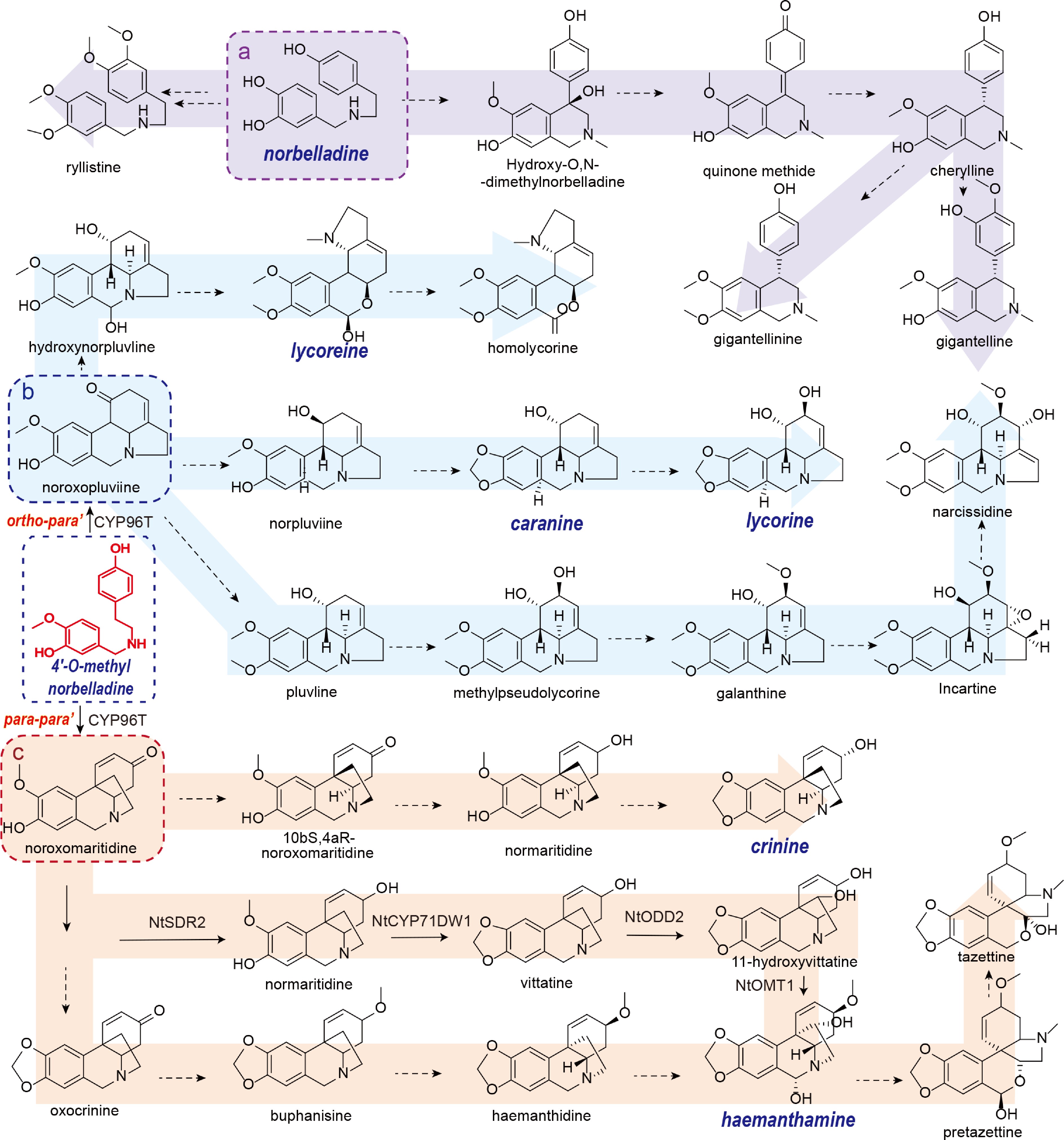

In contrast to other AAs that derive from 4'-O-methylnorbelladine, cherylline-type AAs, such as gigantelline, cherylline, and gigantellinine (isolated from Crinum jagus), are biosynthesized from the earlier pathway intermediate norbelladine[28]. Cherylline is a 4-aryltetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloid. Its skeletal structure is proposed to originate from the hydroxylation of the C11 position of norbelladine, followed by bisphenol cyclization. Owing to their structural similarity, gigantelline and gigantellinine are hypothesized to be derivatives of cherylline. Gigantelline may arise from cherylline via O-methylation of the para-substituted phenolic hydroxyl group and subsequent ortho-hydroxylation. Conversely, gigantellinine may be synthesized from cherylline through methylation at the C7 position[28]. However, the enzymatic machinery responsible for these transformations remains uncharacterized (Fig. 3).

With the exception of the structurally distinct cherylline-type alkaloids, all other AAs are classified as norbelladine-type derivatives[29,30]. The carbon skeletons of pharmacologically significant natural products such as GAL, haemanthamine, and lycorine are each formed through distinct regiospecific C-C coupling reactions of the common precursor, 4'-O-methylnorbelladine[31]. Such C-C coupling reactions represent crucial transformations in specialized metabolism, notably in the biosynthesis of alkaloids, lignans, and lignin[32]. These reactions typically exhibit high regioselectivity and stereoselectivity, properties frequently conferred by cytochrome P450 enzymes. Notably, several CYP96T subfamily enzymes mediating these coupling reactions in AAs have been characterized. These P450s catalyze the conversion of the key intermediate 4'-O-methylnorbelladine into diverse AAs scaffolds via o-p', p-p', or p-o' coupling modes[20,23]. The specific skeletal architecture is determined by the mode of covalent bond formation between the A-ring (C6-C1 unit) and the C-ring (C6-C2 unit). Consequently, CYP96T enzymes function as pivotal gatekeepers, directing metabolic flux from a common intermediate toward distinct structural classes of natural products.

Through the catalytic action of the key enzyme CYP96T, the key intermediate diverges into distinct AAs. Specifically, p-o' coupling yields nornarwedine, a precursor to GAL and lycoramine; o-p' coupling produces norpluviine, which serves as a precursor to lycorine and lycoreine; and p-p' coupling leads to noroxomaritidine, a precursor to crinine and haemanthamine (Fig. 2b)[6].

GAL, a signature Amaryllidaceae alkaloid, is characterized by a distinctive diphenylfuran core containing two chiral centers. Its established biosynthetic pathway originates from the precursor 4'-O-methylnorbelladine. This precursor undergoes para-ortho' phenolic coupling to form demethylnarwedine, which is subsequently methylated by the enzyme N-methyltransferase (NMT) to yield narwedine. The final biosynthetic step involves the NADPH-dependent reduction of the ketone group in narwedine to a secondary alcohol, resulting in the formation of GAL. An alternative proposed pathway suggests that O-dimethylnorbelladine may serve as a substrate. This compound can undergo para-ortho' coupling to form narwedine directly, thereby bypassing the NMT-catalyzed methylation step. Based on structural analogies, narwedine is reductively converted to GAL. Alternatively, narwedine may also be a metabolic branch point, potentially undergoing N-demethylation to form nornarwedine or serving as a precursor to other natural products[33]. Nornarwedine undergoes reduction of its carboxyl group to a primary alcohol, yielding norgalanthamine. This intermediate is then a substrate for two divergent pathways: it can be N-methylated by the enzyme N-methyltransferase (NMT) to form GAL, or it can be converted to lycoramine. Subsequent modifications of GAL include the O-demethylation of the methoxy group at the C9 position to a hydroxyl group, forming sanguinine, and the N-methylation of the group at the C3 position to form childanthine[28]. However, this biosynthetic pathway remains putative, as it has been inferred primarily from structural analogies to known compounds, and the key enzyme catalyzing its central reaction has not yet been identified.

Ortho–para' coupling can yield alkaloids possessing lycorine-type and homolycorine-type frameworks AAs[29,30]. Kirby & Tiwari[34] utilized an isotope labeling technique to examine the biosynthetic conversion of 4'-O-methylnorbelladine into lycorine and lycorenine in Amaryllidaceae plants[35]. Their findings indicated that 4'-O-methylnorbelladine is first converted to the intermediate noroxopluviine, which is then reduced to norpluviine[29]. Subsequently, a methylenedioxy bridge forms between the hydroxyl and methoxyl moieties, yielding caranine. Lycorine is ultimately produced through hydroxylation of caranine. In addition to lycorine-type alkaloids containing a pyrrolophenanthridine core, ortho–para' coupling can also give rise to pluviine[36,37]. Ortho-hydroxylation of pluviine yields methylpseudolycorine, and methoxylation of this hydroxyl group subsequently leads to galanthine. Incartine was first isolated from L. incarnata by Renard-Nozaki et al.[38], who identified it as a key biosynthetic intermediate in the formation of galanthine. Subsequent reduction at C11 of incarnatine introduces a double bond, concomitant with cleavage of the oxygen-containing ring to afford narcissidine. The homolycorine-type framework is biosynthesized via C6-hydroxylation of noroxopluviine, yielding hydroxynorpluviine, which subsequently serves as a biosynthetic precursor for various downstream alkaloids[29] (Fig. 3).

The para–para' phenolic coupling reaction gives rise to crinine-, narciclasine-, tazettine-, and montanine-type AAs. These structural classes constitute the most diverse category of AAs and have substantially enriched the structural diversity of the AAs family. Biosynthesis of these four AA types proceeds through the common intermediate noroxomaritidine[6,29]. The crinine pathway, for instance, involves (10bS,4aR)-noroxomaritidine and (10bS,4aR)-normaritidine as key intermediates. This route requires the formation of a methylenedioxy bridge while retaining a hydroxyl group. Alternatively, noroxomaritidine can be converted to haemanthamine, which possesses a methylenedioxy bridge. Haemanthamine is then transformed via haemanthidine to ultimately yield tazettine[23,39]. This finding leads to the question of whether formation or reduction of the methylenedioxy bridge occurs first. Using isotope labeling, Feinstein & Wildman identified 11-hydroxyvittatine as a key intermediate in the biosynthesis of montanine[40]. An alternative pathway diverges from normaritidine to form vittatine, which is then hydroxylated to yield 11-hydroxyvittatine. This intermediate is subsequently converted into pancracine, and finally to montanine[35,41]. It should be noted, however, that the pathways described above have been inferred primarily from chemical structural similarities, and the key enzymes responsible for these catalytic steps remain to be identified (Fig. 3).

Significant progress was made in 2024 with the elucidation of the core biosynthetic pathways for GAL and haemanthamine. Heterologous co-expression of NtCYP96T1, NtSDR2, NtCYP71DW1, Nt2OGD, and 4OMN in tobacco led to the production of haemanthamine. Similarly, co-expression of NtCYP96T6, NtNMT1, and NtAKR1 resulted in the synthesis of GAL. These findings have elucidated key steps and filled crucial gaps in the biosynthetic pathways of AAs[6].

-

The molecular structure of GAL is characterized by a fused tetracyclic ring system and three stereocenters, which collectively pose significant challenges for its total synthesis. Key obstacles include: (1) the construction and assembly of cyclohexanol, heterocyclic, aromatic, and pyrazole rings into the tetracyclic framework; (2) the establishment and stereoselective incorporation of quaternary carbon centers within the polycyclic architecture; and (3) the controlled introduction of chiral stereocenters[1].

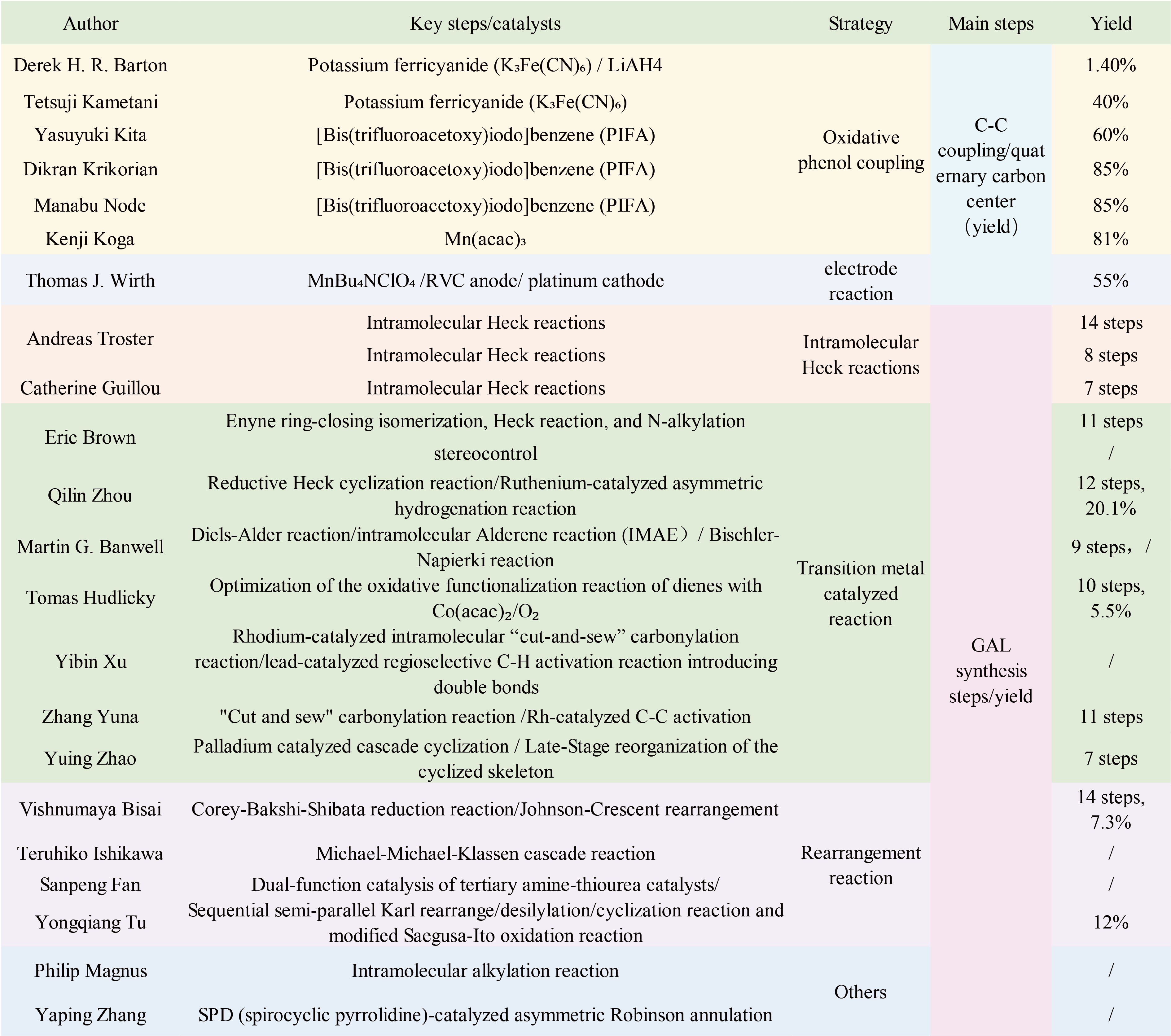

Significant progress has been made in the total synthesis of GAL in recent years. Numerous studies have been devoted to the synthesis of GAL and its analogues, leading to the development of dozens of distinct synthesis routes. Representative strategies employed in these efforts mainly involve transition metal-catalyzed reactions, rearrangement reactions, and alkylation reactions[1] (Fig. 4).

In the biosynthesis pathway of GAL, ortho–para' phenol coupling constitutes a crucial step, which has attracted considerable research interest in its mechanistic and synthesis aspects[42]. Barton was the first to recognize that the biosynthesis of GAL analogs originates from the key precursor 4'-O-methylnorbelladine. The pathway proceeds via ortho–para' phenol coupling of this precursor to form the core C-C bond, concurrently generating a quaternary carbon center and a pyrazoline ring. Subsequent reduction of the ketone group followed by N-methylation of the amino group affords GAL[43]. To construct the core skeleton, a biomimetic strategy was employed, involving an intramolecular oxidative coupling reaction of 4'-O-methylnorbelladine analogues using potassium ferricyanide (K3Fe(CN)6) as an oxidant. This key step efficiently generated the pyrazole ring system, which serves as a pivotal synthesis intermediate for GAL.

Kametani et al. research group investigated synthesis routes to GAL. They observed that substituting amines with lactams and blocking the para position of phenols with bromides markedly enhanced the yield of phenolic coupling products[44]. Later, Arisawa et al. identified [bis(trifluoroacetoxy)iodo]benzene (PIFA) as an effective oxidant for promoting the diphenol coupling reaction[45]. Subsequently, Krikorian et al. employed PIFA to convert amides into tetrahydro derivatives and construct quaternary carbon centers, achieving a yield of 60%[46]. In 2001, Node et al. reported a method for synthesizing GAL using symmetric N-formamide as the substrate[47]. Following this, Koga's group accomplished the asymmetric synthesis of (±)-GAL: using five equivalents of Mn(acac)3 in acetonitrile, a quaternary carbon center was generated in 81% yield and further elaborated into GAL[1]. More recently, Xiong et al. developed a synthesis of (–)-GAL via an anodic aryl–aryl coupling reaction[48]. This approach began with the synthesis of methyl D-tyrosine and methyl gallate, followed by a six-step catalytic sequence to afford a key intermediate. Subsequent electrolysis using 0.1 MnBu4NClO4 as the electrolyte, a reticulated vitreous carbon (RVC) anode and a platinum cathode yielded the product containing the quaternary carbon center. After optimization, a yield of 55% was attained. The intramolecular Heck reaction is widely employed for the construction of quaternary carbon centers. Tröst et al. reported a pioneering total synthesis of GAL that did not rely on phenolic coupling reactions[49]. They constructed the key chiral quaternary center with high enantioselectivity via an intramolecular Heck reaction followed by a palladium-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation (AAA), completing the total synthesis of GAL in 14 steps[39]. However, this route was lengthy and afforded low overall yield. Subsequent optimization reduced the number of steps to eight[50]. Later, the Guillou group achieved a total synthesis of GAL in seven steps using an intramolecular Heck reaction as a key transformation[51]. Together, these three synthesis approaches established a foundational framework for subsequent total syntheses of GAL. In 2007, Satcharoen et al. reported the first stereoselective total synthesis of GAL[52]. This route employed commercially available isovanillin as the starting material and constructed the GAL skeleton via Mitsunobu aryl etherification. Key steps included enyne ring-closing metathesis, a Heck reaction, and N-alkylation to assemble the tetracyclic ring system in just 11 linear steps. Fifteen years later, the same group reported a second-generation asymmetric synthesis that achieved excellent stereocontrol in the production of (–)-GAL[53]. In 2012, Chen and colleagues completed a 12-step total synthesis, affording GAL in 20.1% overall yield[54]. Their strategy featured the construction of a benzylic quaternary carbon center via a palladium-catalyzed intramolecular reductive Heck cyclization and employed dynamic kinetic resolution (DKR) in a ruthenium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation. In 2015, Nugent et al. developed a novel total synthesis of GAL[55]. Their approach involved the preparation of the aromatic ring through a Diels–Alder reaction, construction of the heterocycle and the associated quaternary center via a palladium-catalyzed intramolecular Alder-ene (IMAE) reaction, and formation of the seven-membered ring using a modified Bischler–Napieralski reaction, culminating in a six-step synthesis of GAL[56].

Additionally, Endoma-Arias & Hudlicky developed a ten-step chemoenzymatic synthesis of GAL starting from ethyl phenylacetate, achieving an overall yield of 5.5%[57]. A key advantage of this approach is the streamlined conversion of diene to narwedine via an improved oxidative functionalization reaction using Co(acac)2/O2. Xue & Dong proposed a novel strategy for the total synthesis of both GAL and lycorine[58]. This concise route features a Rh-catalyzed intramolecular 'cut-and-sew' carbonylation to construct the tetracyclic skeleton, followed by a Pb-catalyzed regioselective C–H activation to introduce the requisite double bonds.

Zhang et al. accomplished an 11-step total synthesis of GAL, which incorporates a gram-scale Rh-catalyzed C–C activation via a 'cut-and-sew' carbonylation, and a late-stage Pd-catalyzed dehydrogenation through C–H activation[59]. This work represents the first example in natural product synthesis where transition metal-catalyzed C–C activation and C–H activation are strategically integrated. Chang et al. reported an efficient formal total synthesis involving a two-stage process: an early-stage palladium-catalyzed carbonylative cascade cyclization and a DDQ-mediated regioselective intramolecular oxidative lactamization to assemble the tetracyclic skeleton; and a late-stage BF3·OEt2-promoted selective rearrangement of the bridged system to afford both GAL and lycorine[60]. Majumder et al. achieved the asymmetric total synthesis of the dihydrobenzofuran core of GAL[50]. Their approach utilizes a novel catalytic enantioselective Corey–Bakshi–Shibata (CBS) reduction to convert α-bromoketones into chiral secondary alcohols, followed by a Johnson–Claisen rearrangement to transfer the stereochemistry to an all-carbon quaternary center, yielding GAL in 14 steps. with 7.3% overall yield. Ishikawa et al. developed an efficient route to GAL intermediate 4,4-disubstituted cyclohexane-1,3-diones via a Michael–Michael–Claisen cascade reaction[61]. This method employs aromatic or aliphatic substituents to construct the quaternary carbon center through classical enolate alkylation. Chen et al. accomplished the asymmetric synthesis of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids via a Michael addition between α-cyano ketones and acrylates catalyzed by a bifunctional tertiary amine–thiourea catalyst[59]. The Tu teams synthesized GAL in 12% overall yield by introducing a specific allylic alcohol architecture and core framework through a sequential semipinacol rearrangement/desilylation/cyclization process and a modified Saegusa–Ito oxidation[39, 62]. Magnus et al. generated GAL via intramolecular alkylation of phenolic analogs[63]. Jiang et al. achieved the synthesis of GAL through an SPD (spirocyclic pyrrolidine)-catalyzed asymmetric Robinson annulation, highlighting the utility of SPD catalysts in constructing quaternary carbon centers and offering an alternative strategy for synthesizing other GAL-type alkaloids[64].

-

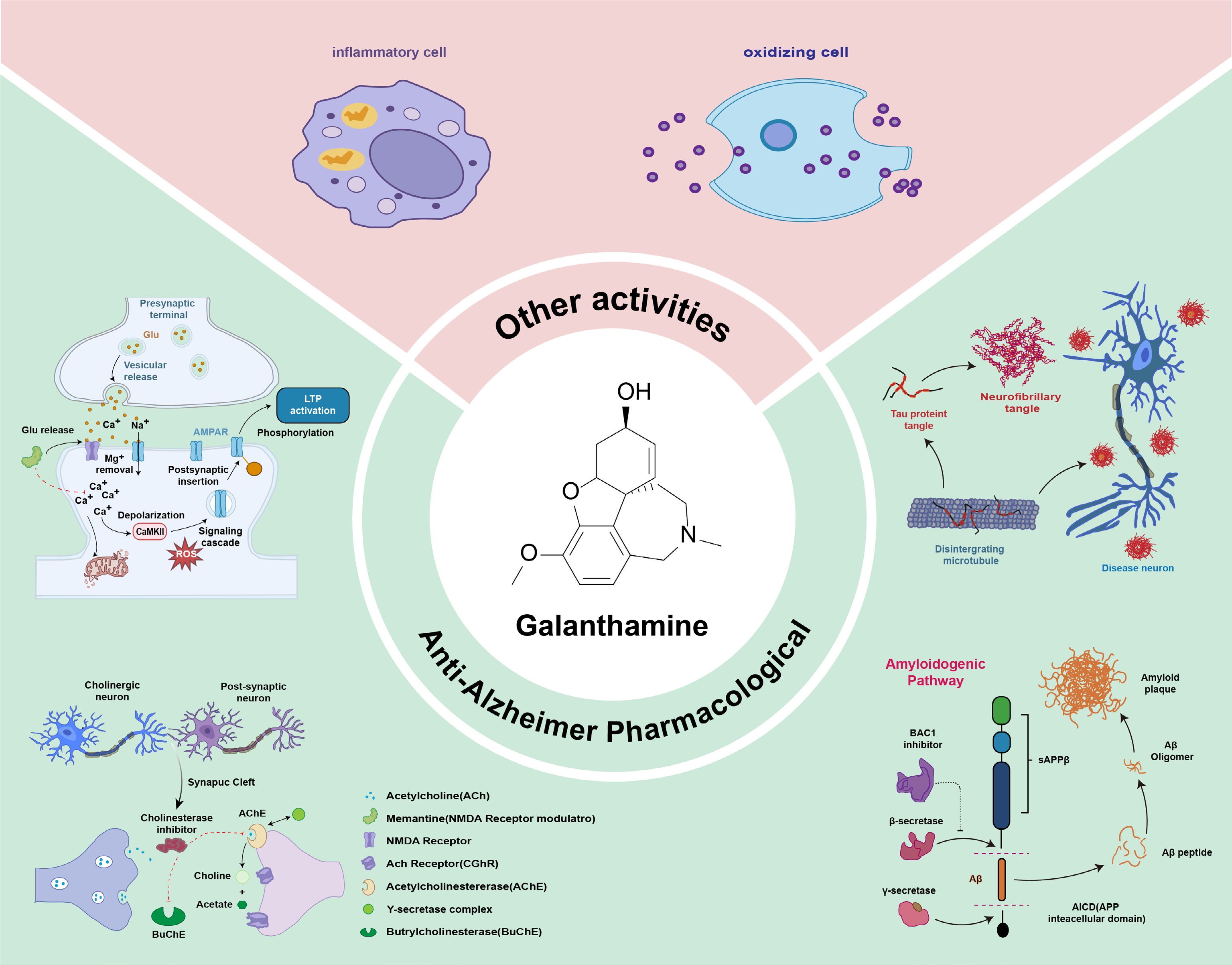

As a unique member of the Amaryllidaceae alkaloids, GAL exhibits diverse pharmacological activities, such as antioxidant, antibacterial, and immunomodulatory effects. It also demonstrates considerable advantages in the treatment of AD, including well-established therapeutic efficacy, mild side effects, and a more potent central cholinesterase inhibitory activity compared to other AD medications[1]. Consequently, GAL has emerged as one of the first-line therapeutic agents for AD[65]. Additionally, GAL is employed in the treatment of various conditions, including angle-closure glaucoma, myasthenia gravis, post-polio syndrome, peritonitis, and postoperative intestinal muscle paralysis. It also acts as an inhibitor of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) release[66].

The development of GAL analogues into clinically applicable therapeutics has progressed more slowly than that of GAL itself. However, the increasing burden of human diseases, coupled with the limited availability of effective therapies, has prompted the reevaluation of several previously overlooked natural compounds as promising sources of drug candidates[66]. This review focuses on the pharmacological activities of GAL and its analogs to facilitate the development of novel clinical therapies. Herein, recent advances in the pharmacological activities of galantamine and its analogs are reviewed. The goal is to pinpoint compounds with significant potential and to offer a valuable resource for future studies (Fig. 5).

Anti-Alzheimer effect

-

The molecular mechanisms through which GAL exerts its anti-Alzheimer's disease effects are multifaceted. Primary mechanisms include: enhancing acetylcholine (ACh) activity, inhibiting acetylcholinesterase (AChE), allosterically modulating nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), regulating neurotransmitter release, reducing β-amyloid (Aβ) deposition, and conferring neuroprotection via anti-apoptotic effects[67−69]. These mechanisms counter three hallmark pathological features observed in Alzheimer's disease brains: amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and the loss of cholinergic neurons. GAL is a specific, competitive, and reversible cholinesterase inhibitor. It binds competitively to acetylcholinesterase (AChE) in the synaptic cleft, thereby effectively blocking acetylcholine (ACh) degradation[70]. In addition to inhibiting AChE, GAL acts as an allosteric potentiating ligand of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), modulating their activity. By preventing ACh hydrolysis, GAL increases the concentration of ACh in the synaptic cleft. Furthermore, GAL binds to allosteric sites on both presynaptic and postsynaptic nAChRs of cholinergic neurons, enhancing nicotinic neurotransmission. While binding of GAL alone to presynaptic nAChRs produces limited effects[71], co-binding with ACh significantly amplifies the nAChR response. Thus, GAL enhances cholinergic signaling by increasing the probability of nAChR channel opening and reducing receptor desensitization[67]. Moreover, through competitive inhibition of AChE, the primary enzyme responsible for ACh breakdown, GAL prolongs the availability of ACh in cholinergic synapses[72]. This inhibition slows ACh metabolism, resulting in elevated synaptic ACh levels.

β-Amyloid (Aβ) deposition and neurofibrillary tangles—resulting from aberrant hyperphosphorylation of microtubule-associated tau protein—constitute key pathological hallmarks of AD [73,74]. GAL mitigates Aβ-induced neuronal damage by inhibiting the activation of the calpain-I/calcineurin pathway and the phosphorylation of the pro-apoptotic protein Bad. Furthermore, GAL may confer neuroprotection against Aβ40-induced injury via modulation of calpain–calcineurin signaling and Bad phosphorylation, a process potentially mediated by α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7 nAChRs). Additionally, GAL ameliorates cognitive function through suppression of TNF-α and IL-6 expression, reduction of Aβ deposition, and inhibition of astrocyte activation[67, 75]. Collectively, these mechanisms support the role of GAL as a neuroprotective agent counteracting Aβ-related pathology.

Hyperphosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau, which leads to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles, represents another key pathological hallmark of AD. Studies indicate that microtubule affinity-regulating kinase 4 (MARK4) plays a critical role in this process. Specifically, MARK4 phosphorylates tau at the Ser262 residue, prompting its dissociation from microtubules and facilitating further phosphorylation by other kinases, thereby accelerating AD pathogenesis. GAL inhibits MARK4 activity, thus attenuating aberrant tau hyperphosphorylation, and slowing the progression of Alzheimer's pathology[76].

Pharmacological effects of derivatives

-

AAs, a class of isoquinoline alkaloids, are widely recognized for their therapeutic potential. In addition to their putative endogenous role in plant defense against pathogens, AAs exhibit diverse biological activities relevant to human health[26]. As a large family of natural compounds, AAs demonstrate broad pharmacological properties, including antiviral, antibacterial, and neuroprotective effects. Recently, numerous novel AAs with potent pharmacological activities have been identified[66].

Lycorine, a biologically active isoquinoline alkaloid isolated from the bulbs of Lycoris radiata, has been reported to exhibit non-nucleoside RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) inhibitory activity[77]. It demonstrated potent anti-proliferative effects against HL-60 myeloid leukemia cells (IC50 = 0.6 μM)[78]. In gastric cancer, lycorine inhibits cell proliferation and resensitizes drug-resistant cells. Mechanistically, it upregulates the ubiquitin E3 ligase FBXW7 and downregulates the anti-apoptotic protein MCL1, thereby reducing MCL1 protein stability. This leads to S-phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in gastric cancer cells[79]. The anti-tumor efficacy of lycorine is significantly enhanced when combined with the BCL2 inhibitor HA14-1. Furthermore, lycorine demonstrates notable multidrug resistance (MDR) reversal activity in human ovarian adenocarcinoma cells (HOC)[80]. Beyond its oncological applications, lycorine exhibits potent, non-nucleoside direct antiviral effects against emerging coronaviruses by specifically inhibiting viral RdRp. It also possesses broad pharmacological activities, including antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor effects. Its neuroprotective capacity, comparable to that of GAL, enables it to counter Aβ-induced damage. Notably, lycorine exhibits a stronger binding affinity to Aβ40 than GAL, effectively interfering with Aβ40 aggregation. This provides a mechanistic explanation for its superior efficacy over GAL in protecting the brain from Aβ-induced neurotoxicity[81].

Lycorine, 11-hydroxyvittatine, haemanthamine, and hippeastrine have been reported to exhibit anti-influenza A virus activity by inhibiting the nuclear export of viral ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes following viral entry[82,83]. Notably, lycorine, and haemanthamine demonstrate significant inhibitory activity against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)[84]. The newly identified styrene alkaloid 2 [(+)-1-hydroxy-angustamine] exhibits potent cytotoxicity against meningioma, astrocytoma, and CHG-5 cell lines. Furthermore, lycorine and its analogues show therapeutic efficacy against both chemotherapy-sensitive and drug-resistant variants of human ovarian adenocarcinoma cells[81, 85]. Hippeastrine hydrobromide represents a highly promising therapeutic candidate for Zika virus (ZIKV) infection, as it potently suppresses ZIKV replication and eliminates the virus from infected human pluripotent stem cell-derived cortical neural progenitor cells (hNPCs)[86].

Dihydro-narciclasine analogues and trans-dihydrolycoricidine inhibit the replication of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1). Among these, the dihydro-narciclasine analogue featuring a single C7-OH substitution on ring A demonstrates particularly potent activity. Both compounds activate the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 signaling pathway, the integrated stress response (ISR) and its associated networks, as well as autophagy and sirtuin-1 signaling pathways. 7-Deoxy-trans-dihydrocucurbitacin reduces β-amyloid (Aβ) production by lowering amyloid precursor protein (APP) levels and delaying APP maturation. Montanine exhibits cytotoxic properties and induces apoptosis in MOLT-4 cells through caspase activation, mitochondrial depolarization, and Annexin V/PI double staining. As montanine concentration increases, protein levels of phosphorylated Chk1 (Ser345) are upregulated in these cells[87].

Bufanidine, bufamide, and bisindole-type alkaloids display affinity for the serotonin transporter, suggesting potential applications for treating depression and anxiety disorders[88]. Certain crinine-type alkaloids exert antitumor effects primarily by inhibiting tumor proliferation and inducing apoptosis[89]. Specifically, buphanidine inhibits glioblastoma cell proliferation by inducing cellular quiescence, indicating that crinine-type alkaloids may represent potential therapeutics for apoptosis-resistant cancers such as glioblastoma[90]. Haemanthamine and lycorine exhibit potent activity against both trypomastigote and amastigote forms of T. cruzi, as well as against amastigotes and promastigotes of L. infantum[84]. 7-Methoxy-O-methyllycorine shows promising activity against T. cruzi trypomastigotes and L. infantum amastigotes.

A new homolycorine-type alkaloid, designated 2α-methoxy-6-O-ethyloduline, was isolated from Lycoris radiata (Amaryllidaceae family) and was found to exhibit weak antiviral activity against influenza A viruses[91,92]. Separately, pretazettine alkaloids, characterized by a benzopyrano[3,4-c]indole ring system, demonstrate therapeutic efficacy against subcutaneously implanted Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC), a representative tumor model. Pretazettine inhibits lung metastasis and prolongs survival in this model[91]. Jonquailine, a novel pretazettine-type alkaloid, exhibits significant antiproliferative effects against glioblastoma, melanoma, uterine sarcoma, and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines. Notably, it acts synergistically with paclitaxel to inhibit the proliferation of drug-resistant lung cancer cells. Furthermore, its anticancer activity, which is substantial and a major focus of current research, is also associated with its known inhibition of viral reverse transcriptases and anti-leukemic properties. A critical structural determinant for this activity is C-8 hydroxylation, which appears to be independent of lactone stereochemistry and acetalization status[93].

Narciclasine-type alkaloids, which feature a lycoricidine ring system, can reverse damage to renal tubular epithelial cells by inhibiting NF-κB signaling pathway activation, thereby suppressing fibroblast proliferation and activation[94,95]. Narciclasine, 7-deoxynarciclasine, and narciclasine-4-O-β-D-xylopyranoside, isolated from Hymenocallis littoralis, exhibit antiparasitic activity[96]. Narciclasine demonstrates potent anti-proliferative effects in various cancer cells by inducing G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Furthermore, it has shown antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties in multiple disease models[97]. Mechanistic studies indicate that narciclasine maintains cell survival in a dose-dependent manner by inhibiting lipid peroxidation (as assessed by BODIPY™ 581/591 C11 staining) and preserving intracellular glutathione levels. Additionally, narciclasine ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction by inhibiting ferroptosis through BNIP3-mediated mitophagy and maintaining mitochondrial integrity, thereby attenuating sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction. These findings underscore the potential therapeutic value of narciclasine for the treatment of sepsis-associated cardiac injury[96].

In recent years, growing interest in Amaryllidaceae alkaloids has led to the identification of an expanding array of compounds within this family. The continued isolation of novel alkaloids and the characterization of their broad pharmacological activities now underscore the need to consolidate existing research findings to establish a robust foundation for future clinical translation.

-

GAL is a first-line pharmacological treatment for AD, valued for its favorable efficacy and safety profile. Its therapeutic mechanisms are multifactorial: (i) it functions as a reversible and competitive acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, thereby increasing the concentration of acetylcholine in the brain; (ii) it allosterically modulates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors to enhance neurotransmitter release; (iii) it demonstrates neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic properties; and (iv) it inhibits the aggregation of amyloid-β peptides. GAL demonstrates high activity in brain regions with significant cholinergic deficits, such as the postsynaptic region. Its favorable pharmacokinetic profile, including low protein binding and lack of interactions with food or concomitant medications, contributes to its excellent tolerability and low incidence of adverse effects. Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in February 2003 for mild-to-moderate AD, galantamine represents an important therapeutic option for the management of this condition. Originally, GAL was extracted primarily from Amaryllidaceae plants, including Narcissus spp. and Leucojum aestivum (summer snowflake). However, its isolation from natural sources is inefficient due to exceedingly low abundance (typically ~0.1% by dry weight). Consequently, plant extraction is insufficient to meet substantial market demand. This limitation has motivated researchers worldwide to develop in vitro synthesis routes to GAL, aiming to establish efficient and scalable production methods. The evolution of GAL total synthesis strategies reflects progress in modern organic synthesis. Reviewing these efforts provides a valuable platform to examine the interplay between target-oriented synthesis and methodological innovation. GAL will likely continue to serve as a testing ground and a source of inspiration for developing novel synthesis strategies.

The total synthesis of GAL has been successfully established in vitro. Following decades of research, numerous synthesis routes to GAL and its analogs have been developed. Furthermore, the biosynthesis pathway of GAL has been elucidated, facilitating its heterologous production. This review summarizes recent advances in both the chemical synthesis and biosynthesis of GAL. Finally, the current challenges in GAL research are discussed, and potential avenues for future investigation suggested.

This review was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC3404900, 2020YFA0908000), the ability establishment of sustainable use for valuable Chinese medicine resources (2060302), Fundamental Research Funds for Central Public Welfare Research Institutes (ZZXT202008, ZZ14-YQ-046), and Scientific and Technological Innovation Project of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (CI2021B014).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Tong Y, Huang L, Kang L, Wang Y; data collection: Kang L, Wang Y, Li Y; analysis and interpretation of results: Kang L, Wang Y, Shen S; draft manuscript preparation: Kang L, Wang Y, Duan Z, Chen K, Jia Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Kang L, Wang Y, Chen K, Duan Z, Li Y, et al. 2026. Biosynthesis, total synthesis, and pharmacological activities of galanthamine and its analogues. Medicinal Plant Biology 5: e004 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0025-0038

Biosynthesis, total synthesis, and pharmacological activities of galanthamine and its analogues

- Received: 16 April 2025

- Revised: 24 October 2025

- Accepted: 29 October 2025

- Published online: 30 January 2026

Abstract: Galanthamine (GAL), an isoquinoline alkaloid characterized by a unique tetracyclic skeleton bearing three chiral centers, is a potent and selective acetylcholinesterase inhibitor with established therapeutic significance. Extensive pharmacological and clinical investigations over decades have conclusively demonstrated its efficacy and favorable safety profile as an anti-Alzheimer's agent. While the yield of GAL obtained from plant sources remains insufficient to meet current demands, recent advances in both biosynthesis and chemical synthesis offer promising avenues to overcome these supply constraints. This review systematically summarizes and evaluates recent progress in three central domains: (1) elucidation and engineering of biosynthetic pathways; (2) novel strategies for the total synthesis of GAL; and (3) pharmacological profiles of GAL and its structural analogues. By synthesizing knowledge across these disciplines, this work aims to identify persistent gaps in current understanding and highlight emerging opportunities for future research. Particular focus is given to the mechanistic insights into GAL biosynthesis, which may inform the design of high-efficiency microbial or enzymatic production platforms capable of supporting the growing clinical demand for this valuable plant-derived therapeutic.

-

Key words:

- Synthesis /

- Pharmacology /

- Galanthamine /

- Biosynthesis