-

Epimedium sagittatum (Sieb. et Zucc.) Maxim. (Berberidaceae), a cornerstone species in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), is highly valued for its bioactive flavonoids, such as epimedins A–C, icariin, and icaritin, which underpin its broad pharmacological applications[1−3]. However, the sustainable cultivation of this medicinal herb is threatened by anthracnose disease[4−6]. Field surveys conducted by our group in October 2023 revealed severe anthracnose outbreaks (incidence > 15%) across major cultivation areas in the Shennongjia Forest District, Hubei Province, with peak disease severity typically observed from May to October. Although anthracnose is increasingly recognized as a destructive constraint on E. sagittatum's productivity in ecologically sensitive biodiversity hotspots like Shennongjia, the precise etiology of these outbreaks remains unresolved. This knowledge gap hinders the development of targeted and effective management strategies.

The genus Colletotrichum includes numerous pathogenic species known for their broad host ranges and high adaptability, causing devastating anthracnose diseases in a wide variety of agricultural and horticultural crops worldwide[7−11]. As one of the most destructive fungal diseases, anthracnose is characterized by symptoms including necrotic lesions, defoliation, and fruit rot. It affects over 3,000 plant species globally, spanning staple crops (e.g., maize and beans), fruit crops (e.g., mango and avocado), and ornamental plants[12,13]. Species within the C. fructicola complex in particular exhibit notable polyphagy and ongoing host expansion. They have been reported to infect economically significant crops such as persimmon and mulberry in China[14,15], and have also emerged as a serious threat to medicinal plants. For instance, Colletotrichum species severely affect Ophiopogon japonicus, causing yield losses of 30%−50% caused by leaf blight and stem dieback, and often inducing secondary infections[16]. Despite the pervasive impact of this pathogen, comprehensive studies to identify the Colletotrichum species infecting E. sagittatum and to elucidate their multifaceted effects, such as metabolic alterations and growth inhibition, are still critically lacking. This gap impedes the development of targeted and effective disease management strategies.

Beyond direct tissue damage, plant diseases often involve complex interactions that extend to metabolic reprogramming of the host and rhizosphere microbiome dynamics[17−22]. Dysbiosis (i.e., the disruption of beneficial microbial communities in the rhizosphere) is increasingly implicated in heightened susceptibility to various pathogens in agricultural systems[23−25]. However, for E. sagittatum, it remains unexplored whether and how foliar pathogens like Colletotrichum spp. induce shifts in the rhizosphere's microbiome, and what subsequent impact these changes have on the production of critical secondary metabolites such as flavonoids. Concurrently, the need for sustainable disease management solutions that are compatible with organic cultivation practices and environmental conservation in sensitive areas like Shennongjia calls for the exploration of effective, plant-derived biocontrol agents.

Therefore, this study aimed to address these critical knowledge gaps through an integrated approach: (1) identifying the causal agent of anthracnose in E. sagittatum from the Shennongjia Forest District using multilocus phylogenetics (ITS2, GAPDH, TUB2, and ACT) and pathogenicity assays; (2) quantifying the impact of infection on key medicinal flavonoids; (3) characterizing the associated shifts in the rhizosphere's microbiome (bacteria and fungi); and (4) evaluating the potential of the plant-derived phenolic compound carvacrol as a sustainable biofungicide. By elucidating the pathogen's identity, linking the host's metabolic response and rhizosphere dysbiosis to disease progression, and identifying a viable biocontrol candidate, this research provides foundational knowledge for the eco-sustainable management of anthracnose in this valuable medicinal plant.

-

The perennial herbaceous species Epimedium sagittatum (Berberidaceae) used in this study was identified by Professor Junbo Gou of Hubei University of Chinese Medicine. A voucher specimen (E. sagittatum 001) has been deposited at the Herbarium of Hubei University of Chinese Medicine. We confirm that no protected species were involved in this study.

On 7 May 2024, symptomatic leaves of E. sagittatum exhibiting chlorosis and necrotic lesions were collected from plantations showing signs of anthracnose in the Shennongjia Forest District, Hubei Province, China (31°45' N, 110°40' E). Representative healthy and diseased plants, including roots with the adhering rhizosphere soil, were transported to the laboratory for analysis. For metabolomic profiling, leaf samples (n = 20 plants per group: healthy vs. diseased) were immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until processing. Rhizosphere soil samples (one per plant, n = 20 per phenotype) were collected from the root zones of the same plants, carefully separated from roots, and stored at 4 °C.

Pathogen isolation and morphological characterization

-

For fungal isolation, fresh symptomatic leaves were subjected to a sequential surface-sterilization protocol, optimized in preliminary tests to ensure efficacy without tissue damage. The process involved (1) rinsing with 0.1% Tween-20 under running tap water; (2) immersion in 75% (v/v) ethanol for 3 min, followed by 0.1% (w/v) HgCl2 for 2 min; and (3) five rinses with sterile distilled water under agitation (200 rpm, 5 min each). The 2-min HgCl2 treatment was selected as it achieved consistent surface sterilization (confirmed by post-sterilization checks on nutrient agar) without visible tissue damage. The sterilized tissues were aseptically cut into 50-mm2 fragments (approximately eight fragments per leaf) and plated on potato dextrose agar (PDA) ( Hope Bio-Technology). the plates were incubated at 28 °C for 72 h in darkness. Hyphal tips from emerging colonies were subcultured three times on fresh PDA to obtain pure isolates. Purified cultures were cryopreserved in 20% glycerol (v/v) at −80 °C using CryoBanker vials (Mast Group) for long-term storage.

Molecular identification and phylogenetic analysis

-

Genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 100 mg of fresh mycelia using the cetrimonium bromide (CTAB) method (Vazyme Biotech Kit) with RNase A treatment (1 h, 37 °C). Partial sequences of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS2) region, along with regions encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), β-tubulin (TUB2), and actin (ACT), were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using specific primers (Supplementary Table S1) under the following PCR conditions: Initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 45 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Each 25-µL PCR reaction contained 12.5 µL Phanta Max Master Mix (Vazyme, China), 1 µL of each primer (10 µM), and 2 µL of template DNA (~50 ng).

The obtained sequencing reads (Fastq format) were processed using a multistep bioinformatic workflow.

(1) Trimming: Adapters and low-quality bases were removed using Trimmomatic v0.36 with a sliding-window approach (window size: 50 bp, quality threshold: 20, minimum read length: 120 bp).

(2) Read merging: Paired-end reads were merged using PEAR v0.9.6 (minimum overlap: 10 bp, maximum mismatch rate: 0.1).

(3) Chimera filtering: Chimeric sequences were identified and removed using VSEARCH v2.7.1 via both reference-based (UCHIME algorithm applied to the UNITE database) and de novo methods.

(4) Denoising: Overlapping reads were assembled and errors were corrected using FLASH v1.2.0. Sequences containing ambiguous bases (N) or those shorter than 200 bp were discarded.

The concatenated sequences of the ITS2, GAPDH, TUB2, and ACT loci were used to assemble novel DNA signatures and construct a phylogenetic tree using MEGA software. Phylogenetic placement was determined by aligning the consensus sequences against NCBI's GenBank using BLASTn. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using three approaches: (1) Bayesian inference in MrBayes v3.2 (2 runs, 10 million generations, sampling every 1,000 generations); (2) maximum likelihood using RAxML v8.2.12 (GTRGAMMA model, 1,000 bootstrap replicates); and (3) maximum parsimony in MEGA v11 (heuristic search with 1,000 bootstrap replicates). Clade support was considered to be robust when the posterior probabilities exceeded 0.95 or the bootstrap values exceeded 70%.

Pathogenicity assays (Koch's postulates)

-

Koch's postulates serve as the gold standard for determining microbial pathogenicity: (1) the suspected pathogen must be present in diseased hosts, (2) it must be isolated and cultured in vitro, (3) it must reproduce the disease when introduced into a healthy host, and (4) it must be re-isolated from the experimentally infected host while the controls remain disease-free[26].

Detached mature E. sagittatum leaves (n = 12 per fungal isolate per trial) were surface-sterilized with 75% ethanol (15 s), wounded using a sterile needle (4 mm × 4 mm area), and inoculated with 5-mm agar plugs containing actively growing mycelia from 7-d-old cultures. Control leaves received sterile PDA plugs. Inoculated samples were incubated at 25 °C under a 12 h light/12 h dark photoperiod for 7 d. Lesion diameters were measured at 24-h intervals. Each trial was conducted independently three times to confirm pathogenicity.

Metabolomic profiling

-

Targeted metabolomic analysis focused on key flavonoids, namely epimedin A, B, and C, icariin and icariin, using certified reference standards (Chengdu Alpha Biotech Co., Ltd., China). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade acetonitrile and analytical-grade methanol were used throughout. Chromatographic separation was performed using an Agilent 1260 system with a C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm) maintained at 30 °C. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B), at a flow rate of 0.8 mL·min−1. The gradient elution was as follows: 25%–26% B (0–5 min), 26%–34% B (5–6 min), 34%–38.5% B (6–11 min), 38.5%–100% B (11–17 min), 100% B (17–20 min), and re-equilibration at 25% B (20–25 min). Detection was performed at 270 nm with an injection volume of 10 µL. Sample preparation involved grinding the leaf tissue to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen. Approximately 0.2 g of powder was extracted with 2 mL of methanol using ultrasonication (power, 480 W; frequency, 50 kHz; duration, 45 min) at room temperature. Extracts were cooled, centrifuged, and filtered through 0.22-µm membranes before analysis. Reference standards (1 mg·mL−1) were dissolved in methanol. All procedures were conducted using precision balances, with corrections for evaporative loss.

Rhizospheric microbiome analysis

-

Rhizosphere soil samples (n = 3 per group) were collected from the root zone (within 10 mm of the roots' surface) of healthy and diseased E. sagittatum plants using sterile spatulas. Samples were immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further processing. Microbial genomic DNA was extracted from the soil samples using the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The V4 region of the 16S rRNA was amplified using the primers 515F and 806R, and libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform with 2 × 250-bp paired-end reads. Raw sequences were processed in QIIME2 (v2023.2). Denoising and amplicon sequence variant (ASV) identification were performed using the DADA2 plugin, with a clustering threshold of 99% similarity. Taxonomic assignment was conducted using a Naive Bayes classifier trained on the SILVA 138 reference database. Microbial alpha diversity (Shannon index) and beta diversity (Bray–Curtis dissimilarity, visualized via principal coordinate analysis [PCA]) were calculated using the phyloseq package (v1.40.0) in R. Taxa that differed in abundance between healthy and diseased groups were identified using ANCOM-BC, with false discovery rate (FDR) correction (adjusted p < 0.05).

Antifungal bioassays of carvacrol and thymol

-

For the mycelial inhibition assay, PDA medium supplemented with carvacrol or thymol (100 μg·mL−1) was inoculated with 5-mm plugs from actively growing fungal cultures[27]. Plates containing 0.1% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) served as negative controls. Radial mycelial growth was measured after 72 h at 28 °C.

In the detached leaf assay, surface-sterilized E. sagittatum leaves were wounded with sterile needles and inoculated with 5-mm fungal plugs. Either carvacrol or thymol (100 μg·mL−1) was applied to the wound sites. Inoculated leaves were incubated under controlled conditions (25 °C, 90% relative humidity), and lesion diameters were recorded daily. The inhibition rate was calculated as

Inhibition (%) = [(Dcontrol − Dtreatment) / Dcontrol] × 100%, where D is the colony's or lesion's diameter (mm).

Statistical analysis

-

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from four biological replicates (n = 4). Statistical significance was assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc test (p < 0.05) in SPSS v26. Heatmaps and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway visualizations were generated using ggplot2 (R v4.1) and KEGG Mapper, respectively.

-

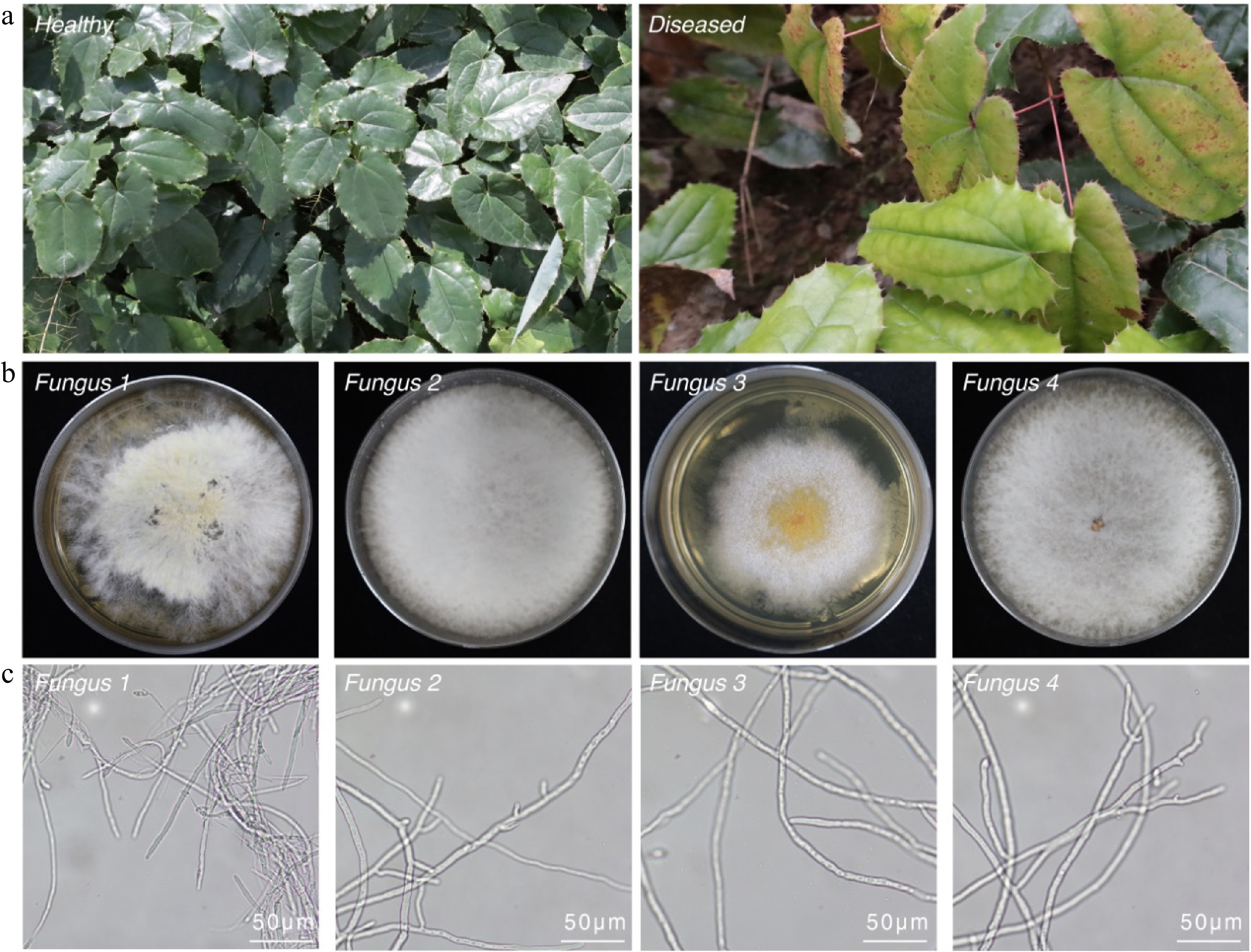

In 2023, widespread foliar chlorosis was observed across a 2,000-acre E. sagittatum plantation in the Shennongjia Forest District, Hubei Province. Disease incidence exceeded 15% in over 15 surveyed plots (50 plants per plot; Supplementary Fig. S1). The initial symptoms appeared as chlorotic halos along the leaf margins, which progressively developed into necrotic brown lesions bearing distinct black microsclerotia (Fig. 1a). These symptoms were consistent with anthracnose as previously reported in Epimedium species from Guizhou Province[28]. The Guizhou cases reported early symptoms of small, light brown to brown circular spots on the leaves' centers or margins. These lesions later expanded into circular, elliptical, or irregular shapes, often displaying concentric rings, with the centers turning grayish-white or grayish-brown and the margins becoming dark brown surrounded by yellowish halos. The symptoms' similarity suggests a possible association with anthracnose.

Figure 1.

Disease symptoms and morphological characterization of Colletotrichum anthracnose in Epimedium sagittatum. (a) Comparative field observations of healthy and anthracnose-infected Epimedium leaves demonstrating characteristic necrotic lesions with distinct chlorotic halos. (b) Morphological features of fungal colonies isolated from infected tissues following 7-d incubation on PDA at 28 °C, showing concentric growth patterns. (c) Microscopic characterization of hyphal structures using brightfield microscopy. Scale bars: 50 μm.

To identify the causal agent, symptomatic and asymptomatic leaf tissues (n = 20 per phenotype) were collected for pathogen isolation. Following surface sterilization (75% ethanol and 0.1% HgCl2), 30 diseased leaves were cultured on PDA at 28 °C for 72 h. Four distinct fungal strains were consistently isolated. Colonies initially exhibited white, cottony mycelia that developed gray-centered pigmentation by Day 7 (Fig. 1b). Microscopic examination of isolates of Fungus 1 to Fungus 4 revealed hyaline, septate hyphae. No characteristic conidia or conidiogenous structures were observed in all isolates at this stage, which is consistent with some hyphomycete fungi under culture conditions.

To further characterize these isolates, partial sequences of ITS2, GAPDH, β-TUB2, and ACT from Fungus 1–Fungus 4 were amplified by PCR using the primers listed in Supplementary Table S1. Successful amplification was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis (Supplementary Fig. S2). Sequencing and BLAST analysis of the ITS2, GAPDH, β-TUB2, and ACT regions revealed that the four isolates represented distinct taxonomic groups. Fungus 2 and Fungus 4 shared 100% sequence identity across all loci, indicating they are conspecific. In contrast, pairwise sequence similarities between Fungus 1 and the other isolates were remarkably low (31.27%−57.28%; Supplementary Table S2), suggesting they belong to different genera. Phylogenetic analysis confirmed these assignments. Notably, Fungus 2 and Fungus 4 shared 100% sequence identity, suggesting they are conspecific, whereas Fungus 1, Fungus 2, and Fungus 3 represented distinct taxa (Supplementary Fig. S2, Supplementary Table S2). To validate these assignments, a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Tamura three-parameter model, with Geobacillus as the outgroup and various Colletotrichum species as ingroups. Phylogenetic inference confirmed the taxonomic identities: Fungus 1 clustered with Diaporthe sp. strain CFCC 54189, Fungus 2 and Fungus 4 clustered with reference strains of Colletotrichum fructicola, and Fungus 3 formed a distinct clade with Colletotrichum sp. KJ-2024b (Fig. 2). These findings reveal a diversity of fungal taxa associated with symptomatic Epimedium leaves, with Colletotrichum (Fungus 2, Fungus 3, and Fungus 4) being the most prevalent.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of Colletotrichum isolates based on a concatenated alignment of the ITS2, GAPDH, TUB2, and ACT genes' regions. The maximum likelihood tree shows bootstrap support values of >30% at the nodes. Reference sequences were obtained from NCBI's GenBank. Isolates characterized in this study are highlighted in red.

Pathogenicity test

-

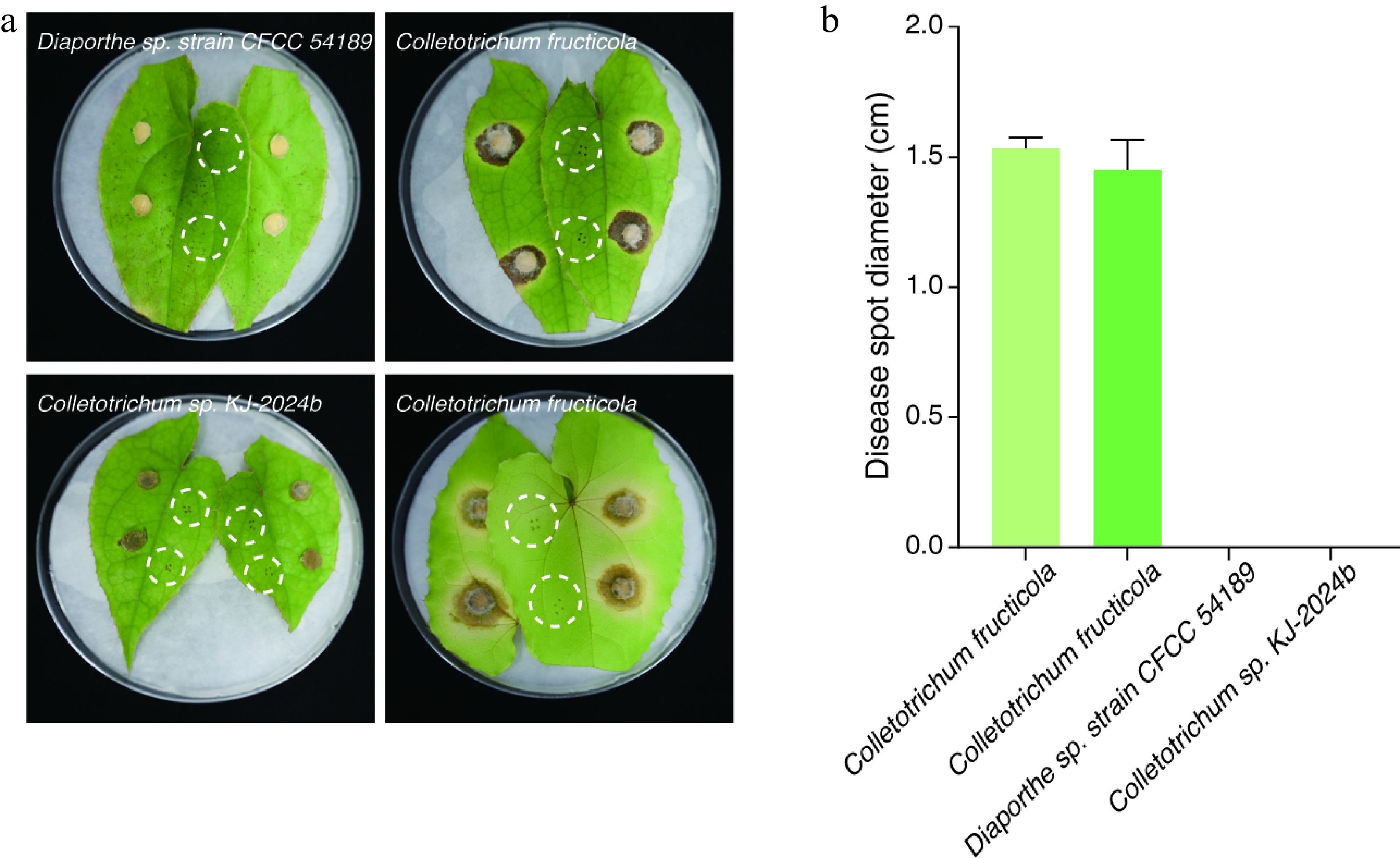

To test these criteria, the pathogenic potential of the four fungal isolates (Fungus 1–Fungus 4) was assessed.

Detached, surface-sterilized E. sagittatum leaves (n = 36 per fungal isolate) were inoculated by injecting 20 µL of a conidial suspension (1 × 106 spores mL−1) into needle-punctured sites. Control leaves were injected with sterile distilled water. All samples were incubated at 25 °C and 80% relative humidity under a 12-h light/dark cycle for 7 d. Strikingly, 100% of the leaves inoculated with Fungus 2 and Fungus 4 developed chlorosis (36/36 leaves), with disease progression closely resembling field symptoms (Fig. 3a). In contrast, no visible symptoms were observed in the leaves inoculated with Fungus 1, Fungus 3, or the negative control (Fig. 3a). Quantitative lesion analysis showed that the C. fructicola strains Fungus 2 (15.3 ± 2 mm) and Fungus 4 (14.5 ± 4.5 mm) induced significant necrosis; in contrast, Diaporthe sp. strain CFCC 54189 (Fungus 1) and Colletotrichum sp. KJ-2024b (Fungus 3) produced no detectable lesions (Fig. 3b). The re-isolated fungi from symptomatic tissues were confirmed to be C. fructicola on the basis of their morphology and molecular analysis (Supplementary Fig. S3), thereby fulfilling Koch's postulates. These findings conclusively demonstrate that C. fructicola (Fungus 2 and Fungus 4) are the primary causal agents of chlorosis in E. sagittatum.

Figure 3.

Assessment of the pathogenicity endophytic fungi on Epimedium sagittatum foliage. Disease symptoms became evident on E. sagittatum leaves at 7 dpi under controlled in vitro conditions. (a) Differential leaf responses to fungal inoculation: C. fructicola (Fungus 2 and Fungus 4), Diaporthe sp. strain CFCC 54189 (Fungus 1), and Colletotrichum sp. KJ-2024b (Fungus 3). White dashed circles demarcate uninoculated control leaves. (b) Quantitative analysis of lesion development revealed significant necrosis induction by C. fructicola strains Fungus 2 (mean lesion diameter: 15.3 ± 2 mm) and Fungus 4 (14.5 ± 4.5 mm), whereas Diaporthe sp. strain CFCC 54189 (Fungus 1) and Colletotrichum sp. KJ-2024b (Fungus 3) exhibited no detectable pathogenic activity. Vertical bars indicate the mean lesion diameter with standard deviation error margins.

Metabolic response to Colletotrichum infection

-

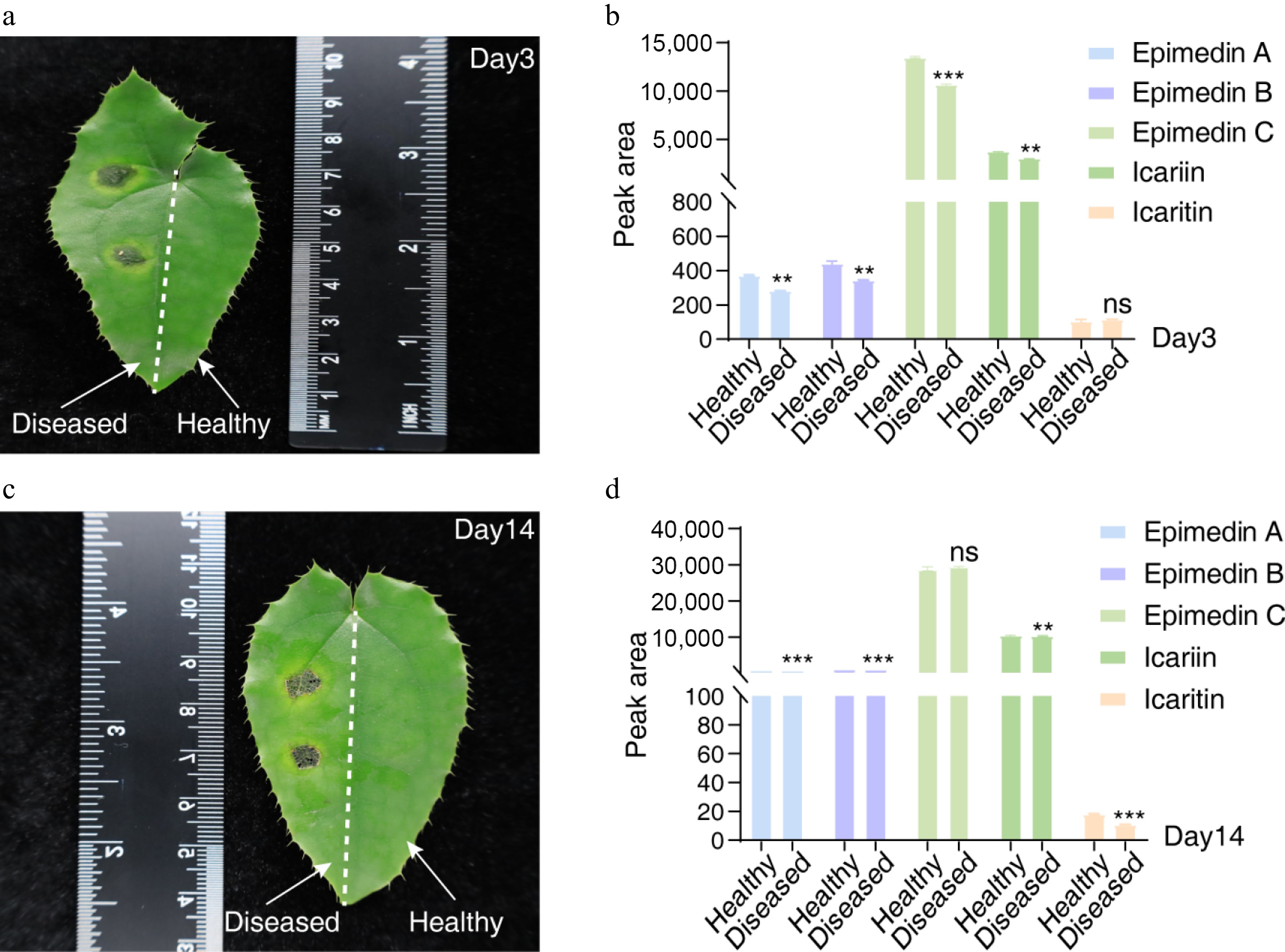

To investigate the host's metabolic alterations in response to Colletotrichum infection, leaves of E. sagittatum were inoculated with the highly virulent isolate C. fructicola (Fungus 2). The levels of five representative flavonoids (epimedin A, epimedin B, epimedin C, icariin, and icaritin) were quantified by HPLC at 3 and 14 days post-inoculation (dpi) (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S3). In pathogen-infected leaves at 3 dpi, significant reductions (p < 0.01) were observed in epimedin A (decreased by 23.85%), epimedin B (decreased by 22.05%), epimedin C (decreased by 20.87%), and icariin (decreased by 19.04%) compared with healthy controls, where icaritin levels remained unchanged (Fig. 4a, b). By 14 dpi, icaritin content showed a marked decline (39.79%, p < 0.01). Though still statistically significant (p < 0.01), the levels of epimedin A, epimedin B, and icariin showed only minor further decreases (4.52%, 3.45%, and 1.49%, respectively). (Fig. 4c, d). Interestingly, epimedin C levels remained stable at 14 dpi, suggesting a plateau effect after the initial suppression (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

Dynamic profiling of flavonoid metabolites in Epimedium sagittatum during Colletotrichum fructicola infection. (a, c) Representative HPLC chromatograms depicting characteristic flavonoid profiles in healthy (control) and pathogen-infected leaves at 3 and 14 dpi, respectively. (b, d) Quantitative analysis of major flavonoid metabolites normalized to the control levels. Data represent the mean ± SD (n = 5 biological replicates). Statistical significance was determined by Student's t-test (**, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ns, p > 0.05 not significant).

This progressive flavonoid depletion was strongly correlated with disease severity (p < 0.01), suggesting that C. fructicola infection disrupts the biosynthesis of these critical medicinal compounds. The sustained suppression of these bioactive metabolites indicates systemic metabolic reprogramming in Epimedium, possibly as an adaptive defense response to fungal invasion.

Rhizospheric microbiome dysbiosis

-

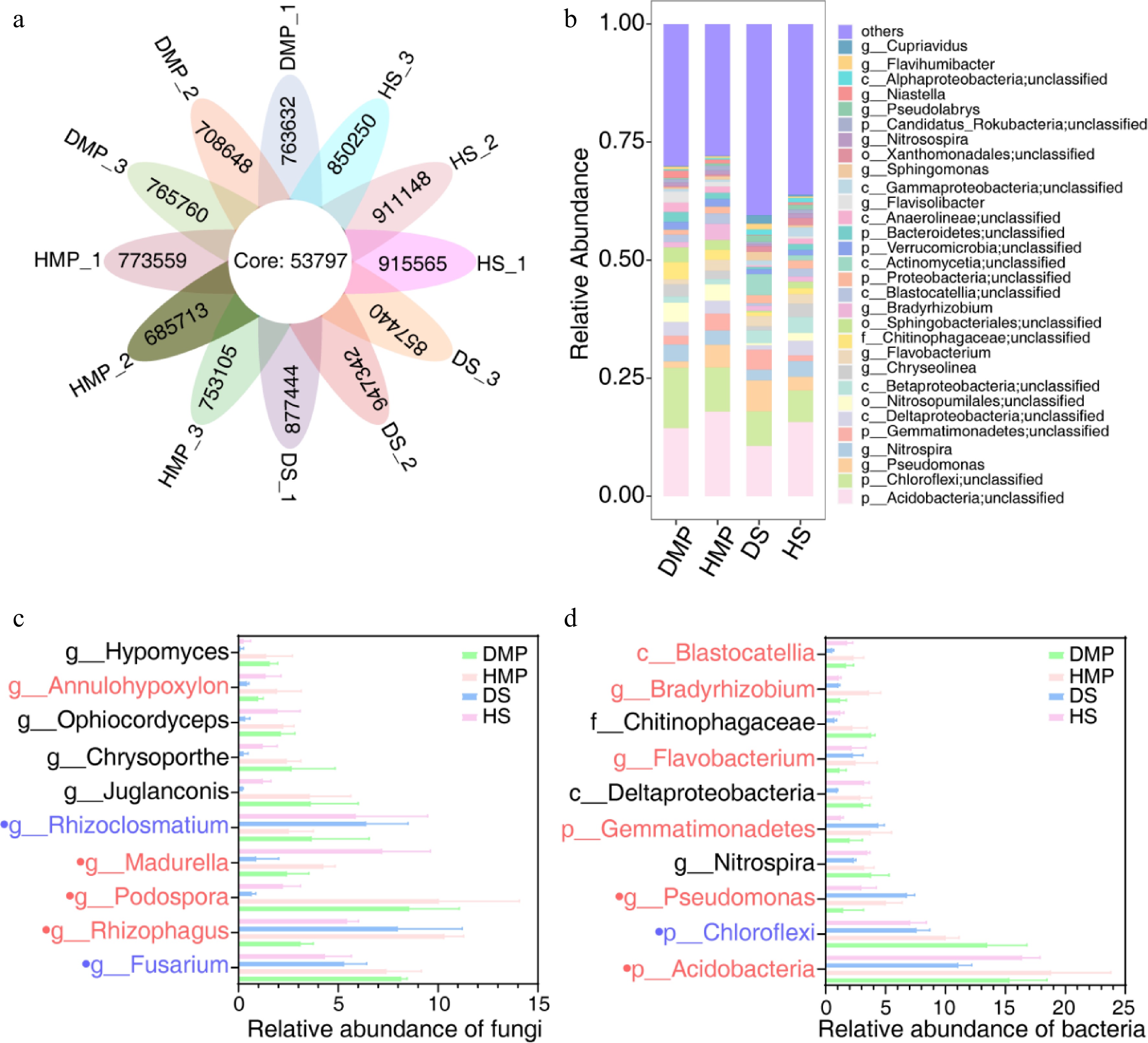

Emerging evidence indicates that rhizospheric microbiome dysbiosis, defined as the disruption of the balance between beneficial and pathogenic taxa, can influence plants' nutrient uptake, stress tolerance, and disease susceptibility[29,30]. To explore the relationship between the incidence of anthracnose and microbial community shifts in Epimedium rhizosphere soils, 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing was conducted on soil samples collected from healthy and mature plants (HMP), diseased and mature plants (DMP), healthy seedlings (HS), and diseased seedlings (DS). Sequencing yielded 1,048,570 high-quality reads (Fig. 5a). After filtering low-abundance zero-radius operational taxonomic units (zOTUs) and rarefaction, 2,839 bacterial and 247 fungal zOTUs were retained for analysis (Supplementary Tables S4–S7). PCA of sequencing data revealed distinct clustering patterns in the rhizospheric microbiomes of healthy versus anthracnose-infected E. sagittatum plants, indicating structural divergence (Supplementary Fig. S4). Significant taxonomic restructuring at the phylum level (FDR < 0.05) was observed between the DMP and HMP groups, as well as between the DS and HS groups (Fig. 5b−d). Rhizoclosmatium, Fusarium, and Chloroflexi, previously linked to plant disease pathogenesis[31−33], were identified; these taxa may promote pathogens' growth and infection through mechanisms such as toxin secretion or nutrient competition. In contrast, Rhizophagus, a beneficial fungus known to promote iron sequestration via siderophore production and to suppress pathogens, was markedly reduced. Family-level analysis corroborated these findings, showing increased relative abundances of putative pathogenic fungal taxa (e.g., Rhizoclosmatium and Fusarium) and bacterial taxa (e.g., Chloroflexi) in diseased samples. Conversely, notable decreases were observed in putative beneficial fungal taxa (e.g., Annulohypoxylon, Madurella, Podospora, and Rhizophagus) and bacterial taxa (e.g., Blastocatellia, Bradyrhizobium, and Flavobacterium, Gemmatimonadetes, Pseudomonas, and Acidobacteria) (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Tables S6, S7).

Figure 5.

Rhizosphere microbiome dysbiosis in diseased Epimedium sagittatum. (a) Relative abundance of bacterial and fungal taxa at the phylum level in healthy (control) and diseased rhizospheres. DMP, diseased and mature plants; HMP, healthy and mature plants; DS, diseased seedlings; HS, healthy seedlings. Significant shifts (FDR < 0.05) are highlighted in stacked bar charts. (b) Heatmap illustrating the differential abundance of dominant microbial families. Red and blue gradients indicate increased and decreased abundance in diseased soils, respectively. (c, d) Fold-change analysis of key taxa, including Rhizophagus (beneficial) and Fusarium (pathogenic). Red represents putative beneficial taxa, blue represents putative pathogenic taxa, and black represents putative amphoteric taxa. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3).

Notably, Colletotrichum, the causal genus of the foliar anthracnose, was not among the dominant taxa in the rhizosphere of diseased plants. However, stringent reanalysis (FDR < 0.00001) detected trace levels of Colletotrichum in both groups, with a significantly higher abundance in healthy soils (p = 0.003, a 1.71-fold difference) (Supplementary Table S4). These results suggest that dysbiosis of the rhizosphere may predispose plants to anthracnose by weakening microbial defenses rather than through direct pathogen enrichment, indicating a complex interplay among hosts, microbiota, and pathogens.

Antifungal activity of carvacrol and thymol

-

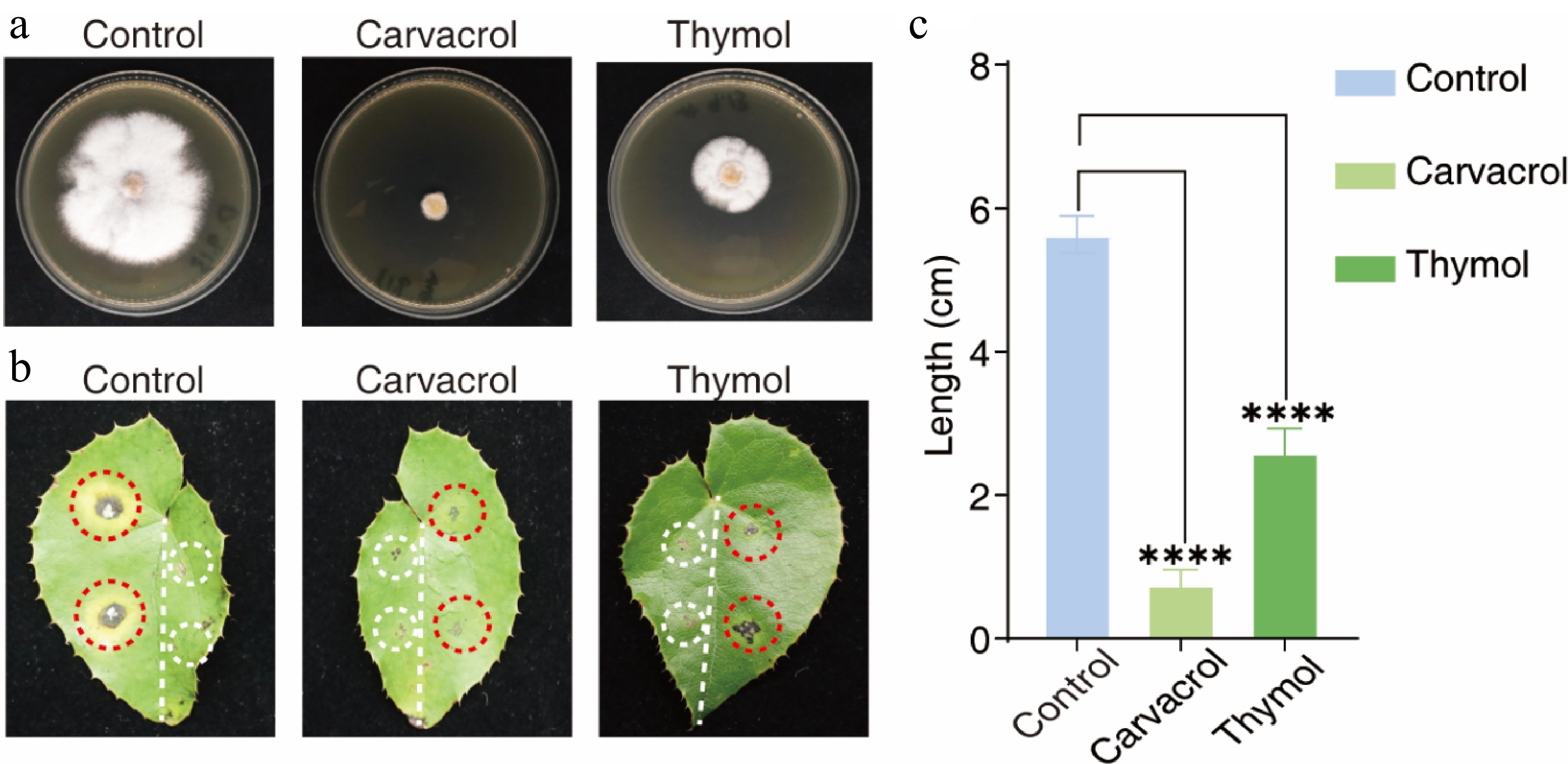

After identifying C. fructicola as the primary causal agent of anthracnose, we evaluated potential control measures to mitigate the widespread foliar chlorosis observed in E. sagittatum plantations. Two plant-derived antifungal compounds, namely carvacrol (a phenolic abundant in aromatic medicinal herbs) and thymol (a monoterpene found in thyme and citrus), were selected on the basis of their reported broad-spectrum antifungal activities[34−36]. To assess their efficacy against C. fructicola, mycelial growth inhibition assays were conducted. The mycelial growth inhibition assays showed that at 100 μg·mL−1, carvacrol and thymol significantly inhibited the growth of C. fructicola by 86.7% and 54.4%, respectively, compared with the untreated control (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Table S8). Both compounds exhibited statistically significant antifungal activity (p < 0.001), with carvacrol demonstrating superior efficacy (p < 0.0001).

Figure 6.

Antifungal efficacy of carvacrol and thymol against Colletotrichum fructicola in detached leaf assays. (a) In vitro mycelial inhibition assay demonstrating the antifungal activity of carvacrol or thymol (100 μg·mL−1) against C. fructicola. (b) Comparison of disease phenotypes: Untreated controls developed characteristic anthracnose lesions (light gray necrotic centers bordered by gray-brown margins) by 10 dpi (left panel, red circles). Carvacrol- or thymol-treated specimens (right panel, red circles) showed complete or intermediate suppression of hyphal proliferation and lesion formation. Control pinhole (white circles): Mechanically drilled aperture showing no detectable growth of fungal hyphae under standard culture conditions. (c) Quantitative lesion analysis: Carvacrol treatment achieved 86.7% efficacy (****, p < 0.0001) by restricting the lesions' diameter to 0.75 cm, significantly lower than the untreated controls (5.63 cm). Thymol demonstrated intermediate inhibitory capacity with a 54.4% reduction in diameter (2.60 cm) (****, p < 0.0001). Data represent the mean ± SD from triplicate experiments (n = 3 biological replicates with three leaves each). Statistical significance determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test.

To validate these findings in planta, detached E. sagittatum leaves were pretreated with 500 μL of 100 μg·mL−1 carvacrol or thymol, followed by inoculation with C. fructicola. The lesions' diameters were measured at 10 dpi. Carvacrol significantly reduced the lesion's size to 2.1 ± 0.4 mm, compared with 12.7 ± 1.1 mm in the untreated controls (p < 0.001; 84% efficacy) (Fig. 6b). Thymol conferred moderate protection, reducing lesion size by 48%. In control leaves, typical anthracnose symptoms (light gray necrotic centers with darkened margins) developed within 10 d, whereas carvacrol-treated leaves showed minimal lesion expansion and no visible hyphal growth or lesion coalescence (Fig. 6b). These results highlight the dual protective and therapeutic efficacy of carvacrol and thymol against C. fructicola, with carvacrol in particular emerging as a promising sustainable alternative to conventional fungicides for managing anthracnose in Epimedium cultivation.

This study identified C. fructicola as the causative agent of anthracnose in E. sagittatum, marking its first reported occurrence in Chinese medicinal plant systems. Concurrently, dysbiosis of the rhizosphere's microbiome, characterized by the depletion of beneficial taxa and the enrichment of opportunistic pathogens, emerges as a critical factor exacerbating disease susceptibility. We further demonstrate that carvacrol, a naturally occurring phenolic compound, exhibits potent antifungal activity against C. fructicola (86.7% inhibition). These findings deepen our molecular understanding of Colletotrichum–host–microbiome dynamics and support the integration of phytochemical-based and microbiome-targeted approaches for sustainable disease management.

-

This study provides a comprehensive investigation of C. fructicola-induced anthracnose in E. sagittatum, integrating pathogen identification, metabolic reprogramming of the host, the rhizospheric microbiome's dynamics, and sustainable antifungal strategies. These findings advance our understanding of plant–pathogen interactions in medicinal herbs and offer actionable insights for ecologically sustainable disease management.

The observed incidence of anthracnose (~15%) in Epimedium aligns with prior reports of C. fructicola's polyphagy in Chinese crops (e.g., persimmon, mulberry)[15,26,27], indicating adaptive host expansion into medicinal plants[28]. The pathogen's dimorphic colony morphology (white to gray) and rapid symptom development (≤ 7 dpi) reflect conserved virulence strategies within the C. fructicola species complex[14,15], underscoring the need for region-specific monitoring and early intervention.

Although dysbiosis of the rhizosphere's microbiome is linked to disease susceptibility in agricultural systems[29,37,38], our work elucidates its mechanistic role in the progression of anthracnose for a medicinal plant. Crucially, we demonstrate that foliar anthracnose (mediated by C. fructicola) induces rhizosphere-specific dysbiosis, contrasting with staple crop models, where soilborne pathogens drive microbial shifts[39]. This dysbiosis is characterized by two key phenomena:

(1) Depletion of plant-beneficial consortia: Significant reductions in nitrogen-fixing bacteria (e.g., Bradyrhizobium) and antifungal taxa (e.g., Pseudomonas), impairing nutrient acquisition and phytoalexin synthesis[40]. Concurrent declines in beneficial fungi (Rhizophagus, Annulohypoxylon) further disrupt iron sequestration and pathogen antagonism.

(2) Enrichment in pathobiome taxa: Increased abundances of acid-tolerant Acidobacteria and pathogenic genera (Fusarium, Rhizoclosmatium), creating a self-reinforcing cycle of host vulnerability via toxin secretion and nutrient competition[31−33]. Our metabolomic analysis was performed on infected detached leaves, revealing a significant depletion of key flavonoids. Although this provides insights into local leaf defense responses, we recognize that the rhizosphere's metabolome is a crucial regulator of the microbiome assembly[41]. It is plausible that the systemic effects of foliar infection extend to the roots, altering the composition of root exudates. The observed sharp decrease in flavonoids such as epimedin A–C and icariin in the leaves may indicate a disruption in carbon allocation or a diversion of defense resources, potentially simplifying the carbon niche available in the rhizosphere. This shift could explain the dysbiosis we observed in the root microbiome, particularly the depletion of beneficial taxa like Pseudomonas and Bradyrhizobium, which are known to utilize flavonoid signals[42]. Concurrently, the enrichment of opportunistic pathogens such as Fusarium and Rhizoclosmatium might reflect their competitive advantage in a metabolically stressed environment. Future studies that directly correlate foliar infection dynamics with simultaneous rhizosphere metabolome profiling are needed to validate these cross-compartment interactions and elucidate the precise chemical cues driving these microbial community shifts. Notably, this dysbiosis precedes the pathogens' dominance in the rhizosphere, with Colletotrichum's abundance paradoxically being lower in diseased versus healthy soils (p = 0.003). This indicates that destabilization of the microbiome, not direct pathogen invasion, predisposes E. sagittatum to anthracnose, challenging established fruit crop paradigms[40].

Given the profound metabolic disruption in the host (flavonoid depletion) and microbiome dysfunction, we evaluated plant-derived antifungals for sustainable control. The superior efficacy (86.7% growth inhibition) of carvacrol over thymol can be attributed to its enhanced membrane permeability and to its potential role in inducing systemic resistance in the host plant, a mechanism that warrants further investigation[27]. In planta validation confirmed carvacrol's protective effect (84% lesion reduction), supporting its use as a biofungicide for organic Epimedium production. However, field deployment faces limitations because of its rapid photodegradation and volatility. Future research should (1) develop nanoencapsulated carvacrol formulations to improve environmental stability and enable its controlled release and (2) evaluate restoration of the microbiome with bioinoculants (e.g., Bradyrhizobium, Pseudomonas, Rhizophagus, and Annulohypoxylon) to synergistically rebuild the plants' defenses.

This work was supported by the Hubei Provincial Science and Technology Plan for 2024 (Grant Nos 2024BBB091 and 2024BCA002), the Wuhan City Targeted Science and Technology Support Project (Grant No. 2025071104010373), the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (NATCM) Special TCM Science and Technology Research Project (Grant No. GZY-KJS-2025-005), the Key Project of Scientific and Technological Research Foundation of Hubei University of Chinese Medicine (Grant No. 2023ZDXM007), and the Open Fund of the Key Laboratory of the National Medical Products Administration (Hubei Province) (Grant No. 2023HBKFZ002).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study design: Gou J, Wu Y; experiment operation: Liu Y, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Quan W; data collection, supervision, and guidance: Hu K, Wang T; study guidance: Hu Z, Liu Y, Li C; draft manuscript preparation: Gou J, Liu Y, Wu Y, Wang B, Shi Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Yu Liu, Yingmei Wu

- Supplementary Table S1 Oligonucleotide primers targeting the fungal ITS2, GAPDH, TUB2, and ACT regions in this study.

- Supplementary Table S2 Comparative analysis of nucleotide sequence similarity among the four amplified fungal ITS2, GAPDH, TUB2 and ACT regions.

- Supplementary Table S3 Dynamic profiling of key flavonoids during Colletotrichum fructicola pathogenesis.

- Supplementary Table S4 Relative abundance of fungal.

- Supplementary Table S5 Relative abundance of bacterial.

- Supplementary Table S6 Top 10 most abundant phylum-level fungal taxa in healthy (control) versus diseased rhizosphere soils.

- Supplementary Table S7 Top 10 most abundant phylum-level bacteria taxa in healthy (control) versus diseased rhizosphere soils.

- Supplementary Table S8 Quantitative evaluation of carvacrol and thymol inhibitory effects on Colletotrichum fructicola growth and lesion development using in vitro PDA plate assays.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Symptomatology and morphological characterization of leaf chlorosis in cultivated Epimedium sagittatum populations from Shennongjia Forest District, Hubei Province, China.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Electrophoretic results of ITS2, TUB2, GAPDH, ACT region amplification in four Fungal isolates.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Pathogen re-isolation from symptomatic tissues coupled with light microscopic analysis (scale bars = 50 μm).

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Principal component analysis (PCA) of rhizosphere microbiome communities in healthy and anthracnose-infected.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu Y, Wu Y, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Quan W, et al. 2026. Colletotrichum fructicola-induced anthracnose in Epimedium sagittatum: pathogenesis, metabolic reprogramming, microbiome dysbiosis, and biofungicide control with carvacrol. Medicinal Plant Biology 5: e003 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0025-0041

Colletotrichum fructicola-induced anthracnose in Epimedium sagittatum: pathogenesis, metabolic reprogramming, microbiome dysbiosis, and biofungicide control with carvacrol

- Received: 06 June 2025

- Revised: 03 November 2025

- Accepted: 05 November 2025

- Published online: 21 January 2026

Abstract: Anthracnose is an emerging threat to Epimedium sagittatum, a cornerstone species in traditional Chinese medicine; however, its etiology in biodiversity hotspots remains unresolved. In this study, we comprehensively identified the anthracnose pathogens affecting E. sagittatum in China's Shennongjia Forest District. Through a combination of multi-locus phylogenetic analyses (based on ITS2, GAPDH, TUB2, and ACT sequences) and pathogenicity assays, we identified Colletotrichum fructicola as the primary causal agent. Beyond pathogen identification, we found that infection triggers a sharp decline in key flavonoids (epimedin A, B, and C; icariin; and icaritin). Concurrent rhizosphere microbiome profiling revealed a shift toward dysbiosis, characterized by the depletion of beneficial taxa (e.g., Annulohypoxylon, Rhizophagus, Bradyrhizobium, and Pseudomonas) and an enrichment of opportunistic ones (e.g., Rhizoclosmatium, Fusarium, and Coccidioides). Strikingly, in detached leaf assays, the plant-derived phenolic compound carvacrol inhibited the growth of C. fructicola by 86.7%. Together, our findings not only identify a pathogen of concern but also delineate a disease progression pathway primarily driven by metabolic reprogramming of the host (flavonoid depletion) and concomitant rhizosphere dysbiosis. We also propose carvacrol as a potent biocontrol agent. This work addresses critical knowledge gaps in medicinal plant pathology and proposes an eco-sustainable strategy for managing anthracnose.

-

Key words:

- Epimedium sagittatum /

- Anthracnose /

- Colletotrichum fructicola /

- Carvacrol /

- Sustainable control