-

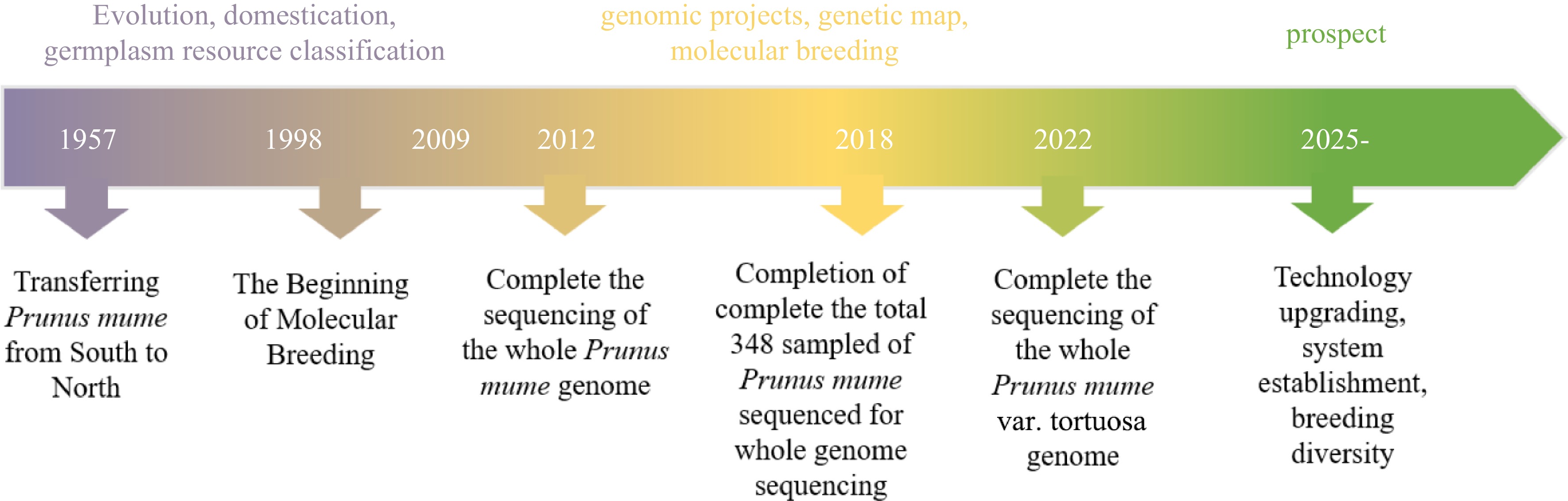

Genomics is a scientific field that encompasses genome mapping, sequencing, and functional analysis of an organism's entire genome. It aims to unravel the complete genetic information encoded in the genome. Plant genomes, in particular, pose significant challenges due to enlarged sizes, complexity resulting from transposable elements, and a long history of genome duplications. The establishment of the Arabidopsis genome sequence in 2,000 has played a vital role in advancing plant genomics and established Arabidopsis as a popular species for fundamental plant research[1]. In recent years, significant advancements have been made in the field of plant genomics, including the development of innovative sequencing technologies and bioinformatic tools, enabling faster, more efficient, and cost-effective genome sequencing and assembly. Currently, approximately 400 plant genomes have been sequenced. This progress has provided a wealth of genetic data for studying plant diversity and has empowered breeders to conduct extensive multidimensional studies in the domains of genetics, genomics, and molecular breeding. These advancements have opened up novel prospects and catalysts for the breeding of various plant species, leading to a revolution in breeding technology.

Prunus mume, also known as Mei, is a classic and renowned flower indigenous to China, ranking among the top ten most famous flowers in the country. It has been cultivated for ornamental purposes and as an important fruit tree for over 3,000 years. The use of P. mume dates back even further, with evidence of their cultivation during the Neolithic period, around 5,000−7,000 years ago[2,3]. The cultivation and evolution of modern Mei varieties have progressed through various stages, including wild Mei, fruiting Mei, flowering Mei, and both flowering and fruiting Mei[4]. Initially, Chinese ancestors began cultivating wild Mei primarily for its edible and medicinal properties. Over time, they also recognized its ornamental value and expanded its cultivation for aesthetic purposes. China plays a crucial role in both the origination and cultivation of plum blossoms, demonstrating its significance as the hub for their genetic diversity and variations. Throughout its long history, Mei populations have undergone continuous evolution and selective breeding[5]. As a result, the vibrant and diverse Mei varieties that we observe today have emerged. These varieties showcase a wide range of colors and characteristics, representing the culmination of centuries of cultivation and selection efforts.

In less than ten years, more than 65 ornamental plants have had their full genomes sequenced, after the completion of the genome sequencing of the first ornamental plant in 2012[6]. The completion of the P. mume genome sequencing has provided a solid platform for other ornamental plants to be studied so that chromosome evolution, genome structure and patterns of genetic variation can be described. A high-quality P. mume genome sequencing has made it possible to identify a number of gene families that regulate desirable and profitable features. Additionally, significant progress has been made in the establishment of fresh genetic mapping projects, the investigation of genome evolution, and the creation of sturdy and dependable molecular markers[7]. The efforts to improve genetic makeup will continue to be greatly impacted by this new information and the resources that are now available.

-

Since 1998, the Mei research team at Beijing Forestry University (China) has been dedicated to studying the mechanisms behind the production of significant traits[8]. By utilizing methods from molecular biology, their research aims to enhance breeding efficiency and establish a solid theoretical foundation for molecular design breeding in Mei. Future targeted and effective breeding techniques would be made possible by the work, which has deepened our understanding of the genetic foundation of desirable traits[8]. The genetic background of Mei has been a challenging aspect to understand given its complicated gene control network, lengthy breeding cycle, and ambiguous genetic composition, and difficulties in studying molecular mechanisms related to traits such as flower fragrance, cold resistance, flower type, and flower bud development, etc. Carrying out whole genomics research is an effective means to break through the research bottleneck. The P. mume Genome Project, launched in 2009, is a collaboration between the National Research Center for Flower Growing Engineering at the Beijing Genome Institute (BGI) and Beijing Forestry University. The wild Mei from Tongmai in Tibet was collected for whole-genome sequencing using the Illumina Genome Analyzer (GA) II method. The wild Mei in this region is highly homozygous due to its closed geographical environment. The final 28.4 Gb clean data was generated by correcting and filtering with 94.7× sequencing depth[6]. Whole genome mapping (WGM) was applied to improve the assembly of the genome. Repetitive sequences, including tandem repeated sequence and interspersed repeated sequence, were extracted from the P. mume genome, with TEs making up 97.9% of these repetitive sequences. The Copia and Gypsy long terminal repeat families were the most abundant TEs in the P. mume genome, aligning with the apple (Malus domestica) genome. The P. mume genome contains 287 small nuclear RNAs, 125 ribosomal RNAs, 209 microRNAs, and 508 transfer RNAs. The Rosaceae family, comprising over 100 genera and 3,000 species, includes fruits, nuts, and ornamental plants with medicinal and ornamental values. Whole-genome sequencing in apple[9], strawberry[10] and Mei[6] , are the foundation for the construction of ancestral chromosomes of Rosaceae and the study of chromosome evolution among Rosaceae. Nine ancestral chromosomes were constructed, with seven strawberry chromosomes produced after 15 fusions and 17 apple chromosomes after one genome replication and five fusions. Eight current chromosomes were created by 11 fusions, whereas its chromosomes 4, 5, and 7 were directly derived from the ancient chromosomes III, VI, and VI, respectively, without undergoing any rearrangement. Special floral scent and early blooming are important properties of Mei. The formation of the distinctive scent of Mei may be explained by the identification of benzyl alcohol acetyltransferase (BEAT) genes that control the production of phenylmethyl acetate, the primary aroma component[6,11]. Six dormancy-associated MADS box (DAM) genes related to dormancy were found to be distributed in tandem and repeated, and six C-repeat binding factors (CBF) gene binding sites were found to be upstream of the DAM gene[6]. Previous research[12] has indicated that the DAM gene and multiple CBF binding sites are significant factors in the early release of dormancy in Mei, making them very sensitive to temperature changes that lead to a short dormancy period and early blooming. These findings are relevant to the investigation of flowering related genes and the molecular mechanism of breaking bud dormancy at low temperature may account for early spring blossoming. Moreover, pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins, which are proteins encoded by plants in response to a variety of stressors, were also identified in P. mume genome. PR10 gene families were significantly and highly expressed in its roots and leaves, as a result, the expansion of the PR10 family may be connected to the plant's reaction to fungus, salinity, and drought in its roots and leaves[13,14]. On the other hand, P. mume genomes were de novo assembled in recent studies, yielding assembly sizes of 241.72 Mb and contig N50 of 3.35 Mb. 31,116 gene models in total were annotated[15]. Recently, the genome sequencing and de novo assembly of P. mume var. tortuosa were performed successfully utilizing Oxford Nanopore technology (ONT). Produced a 237.8 Mb genome assembly that has an anchoring rate of 98.85 when anchored onto eight pseudo chromosomes. In contrast to an earlier draft genome from wild P. mume that had a lower scaffold N50 value (577.82 kb) and contig N50 value (31.77 kb). The recently assembled genome demonstrates substantial enhancements, with a scaffold N50 of 29.4 Mb and a contig N50 of 2.75 Mb[16]. The genome sequencing of Mei and its variants P. mume var. tortuosa has provided a solid framework for exploring the mechanisms that aid in the formation of various essential traits in Mei. The chloroplast genome, as one of the three major genomes in plant cells, is not only small in size compared to the nuclear genome, but it also has relatively independent genetic material chloroplast DNA and a highly conserved genome structure. As a result, the chloroplast genome is frequently regarded as an ideal system for phylogenetic research. In the study of chloroplast genome of Mei, the nuclear and chloroplast genomes of 19 fruit Mei varieties were sequenced[17], and the genetic diversity of fruiting Mei 0.096−0.134 was higher than that of ornamental Mei 2.01 × 10−3. The results showed that natural selection was more advantageous in the domestication process, while ornamental Mei experienced more artificial domestication to meet the needs, resulting in low genetic diversity[17,18]. Besides, mitochondrial genome sequencing can produce more useful SSR molecular markers for the study of species diversity. Currently, the apple[19], strawberry[20], and other species that are similar to Mei were the only ones with pertinent studies on the mitochondrial genomes of Rosaceae; the systematic studies have not been reported in Mei.

-

The purpose of whole genome resequencing (WGR) is to examine genetic variation in Mei with known genome sequences. Sequence alignment allows for the discovery of numerous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), insertion/deletions (InDels), structural variants (SVs), and copy number variations (CNV). These genetic loci information can lay the foundation for population genetics, genome wide association analysis (GWAS) and pan-genome studies. A total of 15 wide individuals and 333 cultivars of Mei as in addition to its most closely related relatives, including Prunus davidiana, Prunus salicina and Prunus sibirica were sampled and sequenced for whole genome sequencing from Wuhan of Hubei Province, Qingdao of Shandong Province, Sichuan Province, Kunming of Yunnan Province, Lijiang of Yunnan Province and Guizhou Province[18]. The Chinese Mei classification system allows for the division of 333 Mei cultivars into 11 cultivar groups, which include Pendulous, Single Flowered, Versicolor, Pink Double, Flavescens, Tortuosa, Green Calyx, Alboplena, Cinnabar Purple, Apricot Mei, and Meiren[4]. After WGR analysis, a total of 1,298,196 SNPs were explored, including 733,292 non-synonymous, 7,313 deletion, 1,117 insertion and 623 structural variants[17]. Utilizing all of the high-quality SNPs observed, phylogenetic relationships among those 351 accessions were created, making use of three more Prunus species for the outgroup. With high confidence, 16 subgroups could be formed from the 348 Mei accessions, with 91.1% of the nodes (318/349) having a bootstrap value greater than 90. Pink Double and Single Flowered exhibit lower linkage disequilibrium (LD) than the natural population, according to linkage disequilibrium analysis results. This is likely due to large introgressions of other species into both of those subpopulations. Mei was divided into True Mei, Apricot Mei and Meiren in accordance with a previous study[2]. The introgression events were analyzed using the three-population F3 test, which showed significant inter-species introgression within the Mei and Prunus species. This resulted in a complicated population structure and analysis of the history of domestication. Genomes of nine Mei and four closely related species like P. sibirica, P. davidiana, P. salicina, and P. persica were sequenced to build a pan-genome. Core genes, 19,135 and 22,499 were sequenced in Mei and Prunus, respectively. There were 3,364 Mei-specific genes in the P. mume genome that were relatively enriched such as flavonoid, phenylpropanoid, stilbenoid, diarylheptanoid and gingerol biosynthesis, along with phenylalanine metabolism, potentially influencing ornamental traits like xylem color, flower color, and floral scent[18]. Evolutionary history of Prunus genus was reconstructed using 13 distinct Prunus accessions with three sequenced closely related species in Rosaceae, and the results showed that P. sibirica may be closer related to Mei than any other Prunus species[18]. It was estimated that 3.8 million years ago (MYA) there was an extinction gap among Mei with other Prunus species, and a 2.2 MYA extinction gap among wild and cultivated Mei. These divergence times significantly precede the projected domestication of cultivated Mei. Furthermore, 129 genomes of Prunus plants, including peach, apricot, and plum, underwent resequencing. By examining the genomes of 79 resequencing Mei varieties[18], the interspecific connectivity of Mei and related species was further ascertained. Numerous naturally occurring and purposely selected locations from interspecific infiltration were discovered, and they had a significant role in the current Mei population's formation[21]. A GWAS method based on logistic regression for 24 Mei traits was established. At the same time, RNA-Seq analysis was done on two typical cultivars 'Wuyuyu' (double red petals, purplish red sepals) and 'Mi Dan Lv' (single white petals, green sepals) was also performed. Based on the examination about the two sets of data mentioned above, the presence of 76 SNPs from different expression genes (DEGs) were found on chromosome Pa4 from 229 kb to 5.57 Mb, which had been linked to petal, stigma, calyx and bud color, accordingly, such as MYB108 (Pm012912, Pa4: 411731-413009), encoding an R2R3 MYB transcription factor, was associated with the anthocyanin metabolism pathway. Moreover, using combined GWAS with quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping[22] , two regions linked with xylem color and filament color on chromosome 3 were localized, including R1 (20601577) controlling xylem color and R2 (444623-3375607) controlling filament color.

-

A genetic linkage mapping depicts the distribution of recombination through a genome from assigning genetic markers within linkage groups and ranking and positioning those markers based on recombination patterns among them. Given their abundance, stability, codominance, efficiency, and ease of automation, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), simple sequence repeats (SSRs), amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLPs), random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD) are important molecular markers which have been widely used for establishing high-density genetic maps. Zhang constructed a F1 generation with multi-petal characters of P. mume and discussed the feasibility of using the 'pseudo-test cross' method to construct a molecular genetic map[22]. Thus, the first genetic map of Mei was produced. Subsequently, based on the development of SSRs, Huang et al. built the framework genetic map by AFLPs and SSRs of Mei using 56 F1 generation of 'Xuemei' × 'Fengpi Gongfen'[23]. A 668.7 cM-long genetic linkage map was constructed with F1 individuals 'Fenban' × 'Kouzi Yudie', by 144 SSR markers. Seventy-one scaffolds comprising approximately 28.1% of the entire assembled P. mume genome were anchored to the genetic map[7]. Soon after, the restriction-site associated DNA sequencing (RAD-seq) method was then used to identify hundreds of thousands of SNPs for 'Fenban' and 'Kouzi Yudie' relying on the Mei reference genome. F1 family of 'Fenban' × 'Kouzi Yudie' was genotyped for SNPs[24]. By adding the selected 1,484 SNPs with the SSR linkage map, a high-density genetic map for P. mume containing a total length of 780.9 cM and eight linkage groups was created. A total of 513 scaffolds with a size of 199 Mb were attached to the genetic map, covering 84.0% of the assembled P. mume genome[24]. Additionally, 84 QTLs affecting stem growth and form, leaf morphology, and leaf anatomy were detected, among which the maximum number of QTLs controlling leaf area and vein number was 35, and the minimum number of QTLs controlling stem diameter was one[25]. The functional mapping framework ('Fenban' 'Kouzi Yudie', 'Liuban' 'Sanlun Yudie', and 'Liuban' 'Huang Lve') incorporates developmental allometry equations to map particular QTLs controlling the development of various phenotypes. These QTLs were integrated into a complex network using evolutionary game theory, and 'pioneering' QTLs (piQTLs) and 'maintaining' QTLs (miQTLs) were detected, which control how shoot height varies with diameter and how shoot diameter varies with height, respectively[26]. Subsequently, another study found that a small region of chromosome 1 (5−15 Mb) has a lot of floral QTLs[27]. Up to now, using 387 individuals developed from Mei cultivar 'Liuban' × 'Fentai Chuizhi'. This genetic linkage map has eight linked groups, including 8,007 genetic markers and the mean marker distance of 0.195 cM. The map's entire length was 1,550.62 cM, or 64.31% of genome. The F1 population yielded 66 QTLs linking 15 plant architecture and significant features connected to flowers. Using the P. mume genome's annotation information, 58 potential candidate genes were examined. Subsequently, the weeping phenotype in Mei was successfully mapped to the genomic regions spanning from 10.54 Mb to 11.68 Mb on chr7. Through this investigation, 10 specific SLAF molecular markers were found to be strongly linked to the weeping trait. Further investigation revealed that nine potential genes were significantly linked to the formation and development of the cell wall, as well as the cellulose synthesis and degradation. Additionally, another set of nine genes predicted to be involved in transcriptional regulation were speculated to play an essential part in the development of the weeping traits observed in Mei[28].

-

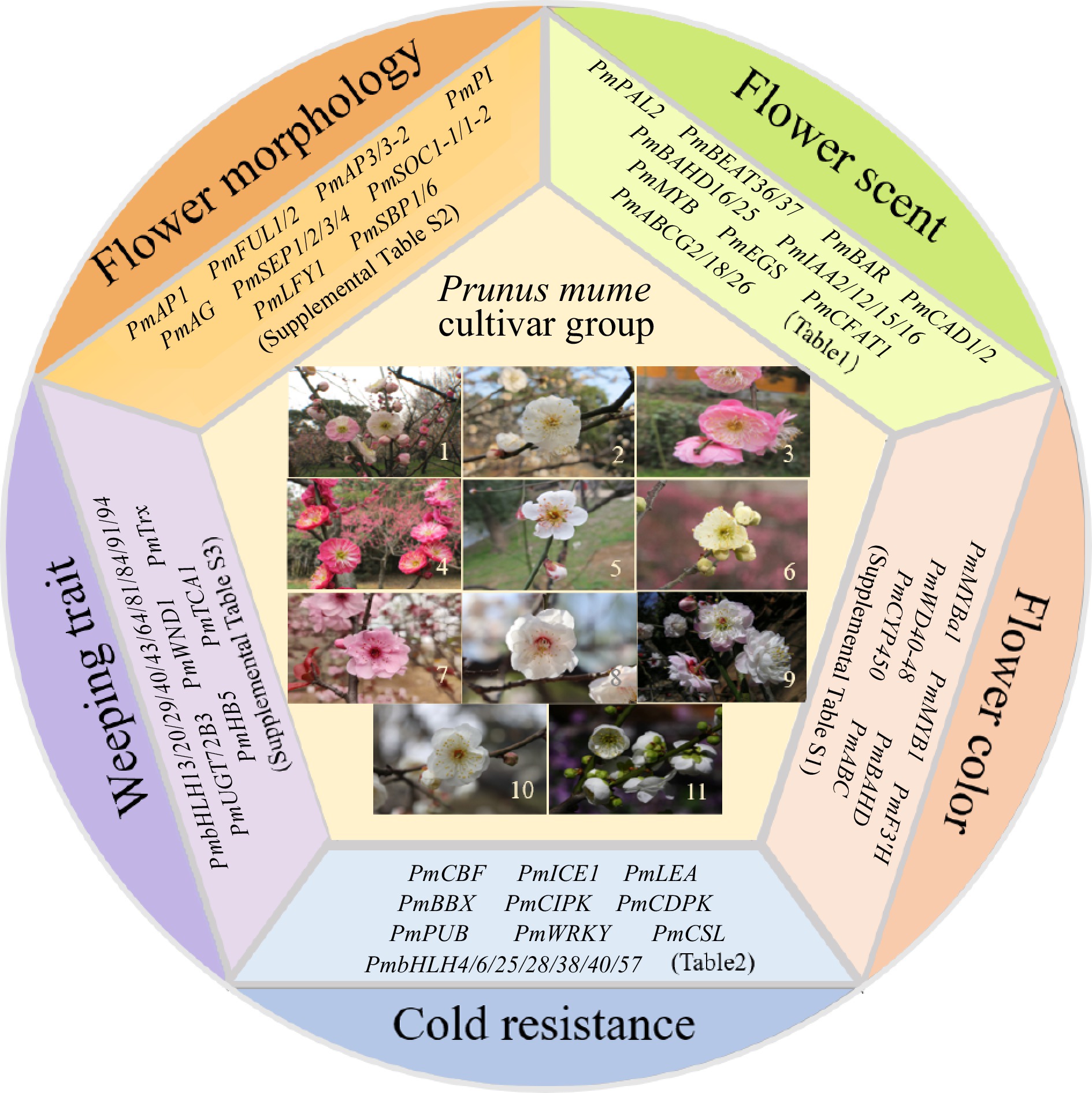

The completion of whole-genome sequencing, resequencing, and the construction of a high-density genetic map for Mei has established a crucial basis for analyzing the genetic regulatory mechanisms underlying important ornamental traits and facilitating molecular marker-assisted breeding. As a result, significant advancements have been made in understanding the genetic mechanisms governing flower scent, color, morphology, weeping traits, and resilience against abiotic stresses in Mei (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Eleven cultivar groups of Mei and representative functional genes in five aspects. 1, Versicolor Group; 2, Dragon Group; 3, Pendent Group; 4, Cinnabar Purple Group; 5, Single Flowered Group; 6, Flavescens Group; 7, Blireiana Group; 8, Apricot Mei Group; 9, Pink Double Group; 10, Alboplena Group; 11, Green Calyx Group.

-

Flower scent is a highly valued quality trait in ornamental plants. In the natural environment, numerous plant species release floral scents to attract a diverse range of animal pollinators, predominantly insects, to facilitate their reproductive cycle. The metabolism of floral scent components, comprising small molecules and volatile chemicals, entails a complex interplay of physiological and biochemical processes. Understanding this intricate mechanism is crucial for unraveling the intricate biology behind floral scents in ornamental plants[29]. With further research on plant secondary metabolism, floral scent components and biosynthesis have been continuously elucidated[30]. Mei stands out among other Prunus species due to its ability to produce strong floral scents. Thus, the study of flower fragrance in Mei has drawn plenty of attention recently. A study conducted in Wakayama Prefecture, Japan, identified 22 components of Mei floral scents through methanol extraction under reflux[31]. However, it was noted that the components extracted by the solvent might not fully reflect the actual aroma components released by Mei. To overcome this limitation, researchers employed headspace solid-phase microextraction combined with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (HS-SPME-GC-MS) to identify the floral scent components of selected Mei cultivates[32], and the results showed that benzaldehyde and benzyl acetate were the key components affecting the aroma intensity of Mei, with their relative contents are 75% and 90.36%, respectively. The relative content of benzyl acetate in P. sibirica was only 0.06%, indicating that benzyl acetate is a characteristic volatile component of Mei. Except for benzaldehyde and benzyl acetate, many unique components, including eugenol, benzyl alcohol, cinnamyl alcohol, cinnamyl acetate were discovered in various Mei cultivars[11,33]. Generally, the different types and contents of compounds released by Mei are the fundamental reasons for the difference in flower scents of Mei cultivars. In one example, benzyl acetate and eugenol made up the majority of the floral volatiles in cultivars with white flowers[34], like 'Fuban Lve', 'Zaohua Lve', 'Subai Taige' and 'Zao Yudie', whereas only 'Fenpi Gongfen', 'Jiangsha Gongfen', and 'Fenhong Zhusha' (pink flowers) synthesized cinnamyl alcohol and cinnamyl acetate. The endogenous extract of the interspecific hybrids in Mei contained less benzyl alcohol, but more benzyl benzoate, which had a competitive inhibition on the production of benzyl acetate, which may result in the difference in characteristic scent between Mei and its interspecific hybrids[33]. The complex biosynthesis of scents compounds from Mei resulted in a wide variety of volatile chemicals with various levels of concentrations. There were notable variations in the endogenous content and volatilization of main components of 'Sanlun Yudie' during the whole flowering stage. In the bud stage, all volatiles were low, and no eugenol was detected. Benzaldehyde had the highest volatility at the end of flowering, benzyl alcohol and benzyl acetate had the highest volatility at full flowering stage, and eugenol had the highest volatility at fading stage. The content of benzaldehyde was the highest at bud stage, benzyl alcohol and eugenol at fading stage, and benzaldehyde acetate at full flowering stage[32]. In addition, previous studies indicated that mostly emit benzenoid chemicals[35]. Subsequent studies further divided the stamens into anthers and filaments and found that filaments primarily emitted benzyl acetate, while anthers primarily released benzaldehyde[36].

Based on genome-wide analysis and RNA sequencing, a substantial number of flower scent-related genes have been discovered (Table 1). A comparison of gene expression differences between the two flowering periods (developed bud and squaring flower) of the 'Sanlun Yudie' revealed 6,954 DEGs and 595 transcriptional regulators included (TFs) of 76 TF families. Under the influence of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), the essential protein in the synthesis of phenylpropane and the benzene ring, phenylalanine produces trans-cinnamic acid[37]. The P. mume genome contained three PmPALs, and PmPAL2 might contribute to synthetic aroma compounds[38]. P450 proteins were found to be particularly abundant during Mei's blooming stage, and two P450 genes were prominently shown in the DEGs that were upregulated[38]. The short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDR) family was closely related with the formation of benzyl alcohol. A total of 147 SDR genes were identified in P. mume genome, and nine candidate genes were significantly expressed in flowers[38,39], suggesting that they might be associated with the synthesis of benzaldehyde and benzyl alcohol in Mei. The MYB family gathered the most 50 TF, followed by 42 basic helix loop-helix (bHLH), and 35 NAC. A total of 36 TFs specifically expressed in flowers were dispersed over 18 TF families[40], including six MYB-related, six MYB, three NAC, and so on. The MYB family was found during the synthesis of flower scent. At present, four MYB TFs (MYB1/2/3/4) from Mei have been identified and described, and the expression levels of three of them increased with the blooming of flowers[18]. In addition, yeast two-hybrid (Y2HGold) and bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays verified that the metabolism regulation processes involved in floral scents, which affected the expression of downstream genes like 3-deoxy-7-phosphoheptulonate synthase (PmDAHPS), arogenate dehydratases (PmADT), PmPAL, CoA ligase/acyl activating enzyme (PmCNL/AAE). Fourty four PmBEATs genes were found in the P. mume genome[11]. PmBEAT34/36/37 were highly expressed in flowers and their highest expression was observed at the blooming stage. Mei flower cell ability to synthesize benzyl acetate could be influenced by the expression levels of PmBEAT36/37. PmBEAT34/3/37 all had benzyl alcohol acetyltransferase activity in vitro[11]. Coniferyl alcohol acetyltransferase (CFAT) is a crucial substrate for the synthesis of eugenol, which catalyzes the conversion of coniferyl alcohol into coniferyl acetate. The 90 PmBAHD (including 44 PmBEAT family) genes were screened from the whole genome and phylogenetically divided into five major groups. PmBAHD67-69 might have a role in the metabolism of floral scents[41]. Two CFAT genes (PmCFAT1 and PmCFAT2) were cloned, and bioinformatics analysis and expression profiling suggest that PmCFAT1 may be crucial for eugenol biosynthesis but not PmCFAT2[34]. DNA methylation is a frequent epigenetic modification and differentially methylated genes (DMGs) were shown to have essential functions in controlling the floral fragrance production of Mei, for instance PmCFAT1a/1c, PmBEAT36/37, PmPAAS3, PmBAR8/9/10, and PmCNL1/3/5/6/14/17/20[11,32,34,42]. O-methyltransferase (PmOMT) may regulate the formation of methyl eugenol and is highly expressed in flower organs in Mei. Three eugenol synthase genes were cloned by RT-PCR from the blooming flowers of 'Sanlun Yudie', named PmEGSI/PmEGS2/PmEGS3 (eugenol synthase genes), respectively. The most significantly expressed PmEGS2 was introduced into petunia (Petunia hybrida 'W115'), which proved that PmEGS2 gene plays a role in the eugenol pathway and participates in eugenol biosynthesis and metabolism[43]. One hundred and thirty ATP-binding cassette (ABC) genes have been found in Mei, classified into eight subfamilies, including 55 PmABCG genes, which were specifically expressed in the flowers[44]. Volatilization of benzaldehyde and benzyl alcohol was substantially connected with PmABCG2/18/26, but negatively correlated with phenylmethyl acetate, and volatilization of benzyl acetate was highly correlated with PmABCG9/13/23. Besides, the study found that PmIAA2/12/15/16 was also involved in the synthesis of benzyl acetate and cinnamyl acetate[45]. These genes, exhibiting high expression levels in various floral organ parts, are believed to have a significant impact on the transmembrane transport of floral components[44]. Through transcriptome analysis and enzyme activity assays, it was demonstrated that PmCAD1 (cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase) was identified as having a crucial part in the biosynthesis of cinnamyl alcohol in vitro. These findings shed light on the specific enzymatic pathway responsible for the production of this aromatic compound in Mei[46].

Table 1. Functional validation information of flower scent.

Flower scent Gene ID Function description Validation methods Reference PmPAL2 Pm030127 Involved in phenylpropanoids/

benzenoids biosynthesisHS-SPME-GC-MS Methods [32] PmBEAT36/37 Pm011009/Pm011010 Performs a key part in the biosynthesis

of benzyl acetateBioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, plasmid construction, subcellular localization, enzyme activity analysis, GC-MS analysis [11] PmBAR Pm012335/Pm013777/

Pm013782Performs a key part in the biosynthesis

of benzyl acetate, as the key genes responsible for BAR activityIntegrative metabolite, enzyme activity, and transcriptome analysis, plasmid construction, qPCR validation [42] PmBAHD16/25 Pm010996/Pm011009 Plays an important role in promoting

the production of benzyl acetateGC-MS analysis, bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern and WGCNA analysis, validation of transgenic Arabidopsis plants [41] PmIAA2/12/15/16 Pm003529/Pm013416/

Pm013597/Pm020225Involved in the synthesis of benzyl

acetate and cinnamyl acetateBioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis [45] PmMYB Pm015692/Pm021211/

Pm025253Engaged in floral fragrance metabolic control via influencing the expression

of downstream genesGC-MS analysis, bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, subcellular localization, vector construction [18] PmEGS Pm012360 Involved in eugenol biosynthesis Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, subcellular localization [43] PmCFAT1 Pm030674 Involved in floral scent metabolism GC-MS analysis, bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, subcellular localization [34] PmABCG2/18/26 Pm001070/Pm022014/

Pm029602Positively linked with benzaldehyde and benzyl alcohol volatilization rates Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, GC-MS analysis of volatile components [44] PmABCG9/13/23 Pm011453/Pm012323/

Pm026080Positively linked with benzaldehyde and benzyl alcohol volatilization rates Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, GC-MS analysis of volatile components [44] PmCAD1/2 Pm021215/Pm021214 Play roles in cinnamyl alcohol synthesis GC-MS analysis, bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR, vector construction [46] -

The color of a flower is a crucial factor that contributes to its ornamental value. In the case of the Prunus species, including Mei, the flowers exhibit a range of colors, primarily purplish-red, pink, pure white, greenish-white, yellowish, and compound colors[47]. The flower color phenotypes of the petals of several varieties of Mei at different developmental stages were determined using colorimetric and chromameter measurements, it was found that the brightness and chromaticity of the flower color of different varieties of Prunus were mainly affected by the value of a*. As the flower color deepened from white to purplish-red, the value of a* (hue) gradually increased. According to the significance of the relationship between the flower color parameter brightness L* and the chromaticity c* and the chromaticity a*, this was related to the anthocyanin content of Mei blossoms, and anthocyanidin glycosides are the key components of flowers that exhibit colors such as pink, red, purple and blue. The main pigments of Mei safflower were determined as anthocyanins and flavonoids by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)[48]. The main components of anthocyanin glycosides in the red line of Mei were Cy3GRh, Pn3GRh, and cornflower-3-O-glucoside (Cy3G), and only the white line did not contain any anthocyanin glycosides, which were colorless or flavonoids determining the white color[18].

Structural genes and transcription factors like MYB, bHLH, and WD40, which may compose the MYB-bHLH-WD40 (MBW) protein complex and participate in the biosynthesis of secondary compounds such as anthocyanins, are typically responsible for controlling the expression of anthocyanin synthesis genes[49]. Among them, MYB is a crucial gene regulating floral color. It affects the expression of structural genes PAL, CHS (chalcone synthetase), F3'5'H (flavonoid-3',5'-hydroxylase), and ANR relevant to flower color and encourages the accumulation of anthocyanins and flavonoids[50]. Major anthocyanin synthesis-related genes were isolated and characterized in the P. mume genome (Supplemental Table S1), and those validated included transcription factors such as PmMYB and PmWD40-48[22,51,52], which are involved in anthocyanin synthesis, and structural genes such as PmF3'H and PmUFGT3 (flavonoid glycosyltransferase), which contribute to red pigment formation[18,48,53]. In addition, the structural genes PmDFR (dihydroflavonol reductase) and PmANS (anthocyanin synthase) may be target genes for the transcription factor PmMYBa1[22]. Similarly, flavonoid and anthocyanin content were found to be the main cause of stem color differences in the study of xylem color traits[54]. In addition, Pm009966, Pm011003 (PmBAHD), Pm011258, Pm017164, Pm019289, Pm020893, Pm025210 (PmCYP450), Pm000414, Pm001802, Pm004453, were identified in the differently methylated regions of red and white petals of Mei, Pm020721, Pm027780, Pm013365 (PmABC), and 13 DEGs as key candidate genes[39].

-

The morphology of flowers serves as one of the fundamental criteria for classifying different varieties of Mei. The development and morphology of floral organs are intricate processes influenced by various factors and their interactions. The diverse range of floral organ morphology and number in Mei has resulted in the emergence of distinct varieties characterized by features such as monopetalous (single-petaled), double-petalous (double-petaled), prolification (abnormal proliferation), flying petalous (petals with an upward orientation), multiple sepals, multiple pistils, and more[2]. To gain a thorough grasp of the molecular regulatory systems underlying flower morphology in Mei, researchers have conducted studies involving microRNA (miRNA) identification, target gene analysis, expression profiling, and functional characterization (Supplemental Table S2). These investigations have expanded our knowledge beyond the post-transcriptional level, shedding light on the intricate processes governing Mei flower development[55]. Through Gene Ontology (GO) analysis, researchers have identified several key microRNAs and their potential target genes involved in regulating various processes related to Mei flower development. Transcription factors, such as those belonging to the GRAS/HAM and Auxin response factors (ARF) families, have been identified as important targets of microRNAs in Mei flower development and played crucial roles in regulating gene expression and coordinating various aspects of flower development, including organ formation, patterning, and differentiation. Additionally, metabolism-associated genes, such as β-glucosidase, acyltransferase, α-1,4 glucan phosphorylase L isoform, and pyruvate dehydrogenase E1, have been identified as targets of miRNAs in Mei flower development. These participate in various metabolic pathways, including carbohydrate metabolism, lipid metabolism, and energy production, which are essential for supporting flower growth and development. The GO analysis of miRNA-regulated genes in Mei flower development provides valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying these processes. By understanding the roles of specific microRNAs and their target genes, researchers can further elucidate the complex regulatory networks that govern flower development in Mei and potentially manipulate these pathways to improve desired traits in cultivated varieties[56,57]. Among them, the transcription factor GARS identified a total of 46 genes in Mei validation of the subfamily DELLA (regulating GA signaling) revealed that PmDELLA is involved in the gibberellin signaling pathway controlling the breaking of dormancy and germination of seeds in Mei[55]. Exogenous gibberellin treated 'Mingxiao Fenghou' branches released from dormancy after 20 d with more than 50% sprouting rate, and the treated branches released from dormancy 31 d earlier than the natural dormancy. Based on the ABCDE model, MADS-box genes involved in flower structure formation were identified and categorized in the P. mume genome. The genes that fulfill the function of class A genes are subfamily Apetala1/Fruitfull (AP1/FUL) of three members (PmAP1, PmFUL1, and PmFUL2)[58]. Class B genes contain the subfamily Apetala1/Pistillata (AP3/PI), with PmAP3 playing a role in gynoecium development, and PmPI and PmAP3-2 in petal and stamen development. Class C genes (PmMADS15/PmAG) are associated with stamens and gynoecium, and class D genes (PmMADS03) are associated with gynoecium[58−60]. PmSEP2 (sepallata) and PmSEP3 are associated with petals, stamens, and pistils, and PmSEP1 and PmSEP4 control sepals, suggesting a function for their E-class genes. Besides, two SOC1 (suppressor of overexpression)-like genes (PmSOC1-1 and PmSOC1-2), and one LFY (LEAFY)-like gene (PmLFY1), as well as the SVP (short vegetative phase) gene (PmSVP1), were also involved in flower organ morphology[61−63]. It has been found that the miR156-PmSBP1-PmSOC1s pathway was discovered to be involved in the controlled blooming[64]. In addition, Y2HGold confirmed that there are protein-protein interactions between different classifications in the MADS-box genes of the P. mume genome[18,65]. Twenty candidate genes, including the hub genes PmAP1-1 and PmAG-2, for the Mei double flower trait were screened out in a study comparing the morphological differences between the floral organs of single and double flower cultivars. Interestingly, Mei's double flower feature frequently coexisted with petaloidal stamens, multiple carpels, and an increase in the overall number of floral organs[66]. The recently created molecular markers can be utilized to identify double bloom of Mei early on and set the stage for future advancements in the breeding effectiveness of double flower of Mei[67].

-

The weeping trait is a distinctive tree-like structure found in woody plants, where lateral branches naturally droop and grow downward. In weeping varieties of Mei, the branches and trunks exhibit a drooping form, adorned with naturally decorated, colorful flowers. With their elegant tree shape, these varieties have significant value and significance in both floral display and as ornamental trees for tourism and horticultural applications. The candidate region for weeping in Mei was identified as 1.14 Mb by QTL, containing 159 predicted genes. The development of SLAF-seq (Specific-locus amplified fragment sequencing) markers was conducted using the F1 population of the hybrid offspring between 'Six Petals' and 'Pink Terrace weeping'. Through QTL fine mapping, the candidate genes for the weeping trait of Mei were localized to the 10.54 to 11.68 Mb region on chr7 of Mei. Furthermore, 18 candidate genes likely related to the control of the weeping trait (Supplemental Table S3) were further screened[26]. Lignin biosynthesis can affect fiber development and thus lead to differences in stress wood structure, and the lignin content of the proximal surface of weeping Mei branches was higher than that of the distal surface, in contrast to that of straight Mei[68]. Nine genes involved in cell wall formation and development and lignin synthesis, selected from them, including cellulose synthase CSL family members Pm024150 and Pm024152, dextranase Pm024254, which contributes an essential part in cell wall alteration, Pm024195, and Pm024255, which are participate in cell wall formation and assembly, as well as those present in secondary cell wall biosynthesis in the growth factor metabolic pathway is positively regulated by the factor growth hormone-inducible protein 5NG4-like (Pm024277)[69]. Related genes whose lignin biosynthesis can regulate tissue secondary cell wall lignification include, Pm024136, which may be involved in xylan metabolism, cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase 1 (Pm024278), Pm024136, and the NAC family gene NAC conserved domain protein 43 (Pm024260)[70]. Among them, Pm024260 has been shown to be linked to the development of secondary cell walls in Mei branches[71]. Furthermore, it was found that the TAC1 (Tiller Angle Control 1) gene was involved in the regulation of branching or tillering angle of plants, PmTAC1 (Pm018391) possessed the typical structural domains of the IGT family, with the highest expression in the stems and the content was much higher in the annual weeping branches than that in the straight branching varieties, and there were differences in the proximal and distal axes of the two kinds of branches. The sequence of the coding region of PmTAC1 showed no differences between the two kinds of branches, but the promoter had sequence differences[72].

Annotation of candidate regions for the weeping trait identified nine genes which affect gene expression at the transcriptional or post-transcriptional levels. Among them, the 26s proteasome (Pm024160) plays a part in the balance between cell elongation and cell differentiation during branch development. The transcription factor 22 protein NIN like Protein7 (NLP7) plays a part in the regulation of nitrate assimilation and signaling processes. The transcription factor bHLH155 (Pm024214) is involved in root development[73]. The transcriptional activator of the growth regulator 8 (Pm024257), which controls cell elongation in meristematic tissues. RPB1 (Pm024270/Pm024271/Pm024275/Pm024123), a DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit, all of which are regulatory genes that can cause differential expression of downstream gene regulatory networks[28]. In addition, branch development and plant architecture are regulated by the plant HD-Zip III transcription factor, which is a key transcription factor controlling the meristematic tissue's formation and maintenance. The results of transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana GUS tissue staining revealed that PmHB5 gene was primarily expressed in meristematic tissues, vascular tissues, and other parts of the plant where cell growth and differentiation were active, and it was hypothesized that it had an impact in the regulation of cell differentiation and branch lignification in stems of Mei[74].

The external factors that altered the angle of inclination of Mei branches were in turn, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), phototropic growth, and gibberellic acid (GA3). The weeping phenotypic traits of Mei were mostly linked to the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway, the phytohormone signaling pathway, and the pathway of starch and sucrose metabolism. In the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway, PER-like genes involved in the process of peroxidase action are associated with vertical traits and exogenous GA3, and such genes are also key genes affecting the weeping traits[75]. Vertical traits also have candidate genes associated with key enzyme activities. Marker437413 (Pm024200), which is involved in auxin transport and metabolism, has been shown to promote cell elongation by ethylene, and thus may be involved in cell elongation due to the candidate genes Pm024219, a serine/threonine protein kinase, with no lysine kinase (WNK8), and Pm024247, encoding a chytridiomycin-like protease[76].

RNA sequencing and comparison of DEGs in straight and weeping Mei's bud and stem tissues were used to identify genes associated with IAA (Pm013243, Pm005112, Pm007046, Pm020838, Pm024306, Pm03020, Pm012502, Pm021243, Pm005182), GA (Pm004966, Pm010085, Pm011672, Pm01992, Pm011163) and some key genes related to lignin (Pm012986, Pm027089, Pm027248)[77]. Combined with QTL analysis, the 9.69-10.65 Mb region on chromosome 7 where the five QTLs associated with weeping traits were located was deemed a highly dependable region linked to weeping traits. Two significant markers markker313919 (Pa7:11324965) and markker437413 (Pa7:11037771) associated with the core SNP (Pa7_11182911) for weeping trait were found based on GWAS and QTL[78]. The main QTL was localized in the 11.03−11.32 Mb interval, also located on chr7. In addition, it was found that the two regions localized to chr7 strongly interacted with each other[78]. Finally, the gene closest to the core SNP was identified as Pm024213, which was found to be highly up-regulated and specifically expressed in weeping by GWAS analysis from 39 candidate genes[18]. In addition, Pm024213 contains a Trx structural domain that may regulate weeping traits via growth hormone-mediated gravity-sensing or light-responsive processes[78].

-

One of the key things limiting Mei cultivars from being bred and promoted at the moment is abiotic stress. The majority of the abiotic stresses that Mei encountered were related to freezing, although research has also been done on how Mei responded to stress from salt, drought, and hot temperatures. As a result, understanding the mechanism underlying abiotic stress is essential to boosting breeding efficiency going forward.

-

Mei originated in southwest China and the Yangtze River basin, is a subtropical tree species. However, in the northern region of China, low temperature has seriously limited the growth of Mei, and few varieties can be applied. The selection and breeding of cold-resistant cultivars of Mei has been an important direction of breeding. Over the years, the cultivation of cold-resistant cultivars mainly focused on the conventional breeding methods such as introduction and domestication, distant cross breeding[5]. Since the 1950s, Chen et al.[2] cultivated a group of cold-resistant of Mei cultivars, such as 'Fenghou', 'Danfenghou' and 'Meimei', by using the introduction and domestication experiments in northern China, and successively carried out regional experiments of different cultivars in Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Shanxi, Qinghai and Gansu[2,79]. Zhang[5] bred cold-resistant cultivars of Mei such as 'Yanxing' and 'Huahudie', through distant crossbreeding with strong cold resistance Mei relatives, which can withstand low temperatures from −35°C to −25°C. Subsequently, a series of cold-resistant cultivars such as 'Yutaizhaoshui', 'Songchun', 'Zhongshanxing' and 'Shantaobai' were selected and bred through several decades of selection, domestication, cross breeding and distant crossing etc. Most of these cultivars are Apricot Mei Group, which laid the material foundation for the concept of 'Transferring Mei from South to North'. Chen et al.[79] used Apricot Mei Group and Mei cultivars to breed a cold resistant cultivar 'Xiangruibai' with the characteristic scent of Mei, which achieved an enormous advance in cold-resistant fragrant flower breeding of Mei. It is worth mentioning that the broad field cultivation region occupied by Mei has spread 2,000 km from the Yangtze River Basin through many years of multi-point comparative experiments.

The comparison of physiological changes of Mei can analyze the difference of cold resistance of different cultivars. The cold resistance of 38 Mei cultivars was analyzed, and it turned out this the cold hardiness of apricot Mei series is higher than that of true Mei series[80]. Similarly, the physiological indexes of Mei growing in different dimensions and seasons were analyzed, and it was found that the 'Yanapricot' cultivar had the strongest cold resistance[39].

With the conclusion of Mei's entire gene sequencing, it is now possible to investigate resistance genes and establish the groundwork for Mei molecular breeding. A vital phase in the upper life cycle of plants, dormancy is an adaptive reaction that allows plants to withstand harsh environments, like cold temperatures[81]. The reaction to cold stress and dormancy was modeled molecularly[82] using the interaction between PmDAM and PmCBF. It was discovered that low temperatures triggered the production of PmCBF, and the build-up of CBF encouraged the development of PmDAM, causing flower buds to go into dormancy[82]. Candidate TFs and target genes that can control Mei dormancy by adjusting endogenous hormone content in response to environmental cues were effectively screened in the coexpression network of genes linked to flower bud dormancy[83]. Among them, ABRE binding factor PmABF2, PmABF4, and PmSVP changed Abscisic acid (ABA) content to govern bud dormancy[83]. Furthermore, it was shown that PmSOC1-2, which interacts with PmDAM, regulates floral bud dormancy via ABA regulation[84]. At present, the research on the molecular mechanism of Mei blossom cold resistance mainly focuses on CBF (C-repeat binding factors), ICE1 (Inducer of CBF expression1), ERF (ethylene responsive transcription factor), LEA, DAM, WRKY and other gene families[7,82,85−87]. Cold stress, which includes chilling (cold temperatures of above 0 °C) and freezing (below 0 °C) stress, is a significant factor limiting plant growth, development, and geographical distribution[88]. Cold acclimation is a protective strategy promoting plant tolerance and resistance to cold stress that is controlled through both CBF-dependent and CBF-independent pathways[89]. Six PmCBFs genes were cloned from Mei, and all of them have been shown to be triggered by cold stress, and the function of transgenic plants was verified[90]. CBF and DAM are the key genes in Mei that respond to cold and dormancy respectively, and the possible interrelationships surrounding the CBF and DAM genes, as cold acclimation and dormancy are closely linked. In particular, the interaction among PmCBFs with PmDAM reveals the molecular mechanism behind cold-response pathway and dormancy regulation in Mei growth[82]. ICE1, a member of the bHLH transcription factor family, might activate AtCBF3 and AtCOR genes in reaction to low temperature[85,91]. Overexpression of PmICE1 increased cold resistance in Arabidopsis compared with control[92]. Meanwhile, other bHLH transcription factors may influence cold tolerance of Mei. There were 95 PmbHLH genes found in the P. mume entire genome, which were grouped into 23 subfamilies. Through investigation of transcriptome and qRT-PCR data, PmbHLH4/6/25/28/38/40/57 was discovered playing a major part in resisting low-temperature stress[93,94]. The overexpression of PmBBX32 gene reduced the damage to Arabidopsis and may improve transgenic plant cold resistance by increasing antioxidant enzyme activity and proline content[95]. Validation of transgenic tobacco showed that overexpression of PmPUB1, PmPUB3 (Plant U-Box E3 ligases) and PmWRKY18 genes increased cold resistance[87,96]. A total of 30 late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) genes were identified on a genome-wide level using the Hidden Markov Model (HMM), four (PmLEA10/19/20/29) of these genes were involved in plant responses to cold[86]. In addition, PmWRKY18 and PmLEA8/19/20 were induced to be expressed by Atco exogenous ABA and may be involved in ABA-dependent cold signaling regulatory pathways[86,87]. Freezing tolerance genes have been discovered in Mei by RNA-seq and ATAC-seq (assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing) analysis. Cold-shock protein CS120-like (PmCSL) expression also considerably significantly up-regulated, meanwhile the chromatin opening of PmCSL was markedly increased[97]. The freezing resistance of transgenic Arabidopsis plants was markedly enhanced by overexpressing PmCSL. Afterward, a large number of genes associated with cold resistance were found in P. mume genome, like 13 HDACs (histone deacetylases)[98], 49 bZIP (basic leucine zipper) transcription factors[99], 113 NAC transcription factor genes[100], 17 SWEET (sugars will eventually be exported transporter)[101], 58 WRKYs[87,102], 16 CIPKs (serine/threonine protein kinase)[103], 11 MAP kinases (mitogen-activated protein kinase, MPKs) and seven MAPK kinases (MKKs)[104], and Table 2 contains additional functional genes and information[105−109]. Gene structures, phylogenetic relationships, cis-acting elements, and expression patterns in reactions to cold treatment were all intensively investigated in order to obtain insights into the mechanisms underlying cold response in woody plants. These investigations have significantly enhanced our comprehension of the roles of gene families involved in cold tolerance. By elucidating the genetic basis of cold response, these studies have provided valuable information for the development of molecular breeding programs in woody plants.

Table 2. Functional validation information of cold resistance.

Cold resistance Gene ID Function description Validation Methods Reference PmCBF1/2/3/4/5/6 Pm023769/Pm023772/

Pm023773/Pm023775/

Pm023777/Pm027913/Key TF that responses to cold signal qRT-PCR, gene cloning and Yeast 2 Hybrid assays, BiFC assays, promoter cloning and Yeast 1 Hybrid assays [82] PmICE1 − PmCBF express levels are increased in response to a low temperature signal Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, subcellular localization, vector construction, Arabidopsis transformation, and low-temperature stress experiments [92] PmLEA10/29 Pm026684/Pm006114 Besponse to cold stress Gene expression analysis, Tobacco transformation and stress tolerance analysis, Relative Water Content (RWC), protein assay and analysis, statistical approach for MDA and REL [86] PmLEA19/20 Pm020945/Pm021811 Response to cold stress; participate in ABA-dependent pathway Gene expression analysis, Tobacco transformation and stress tolerance analysis, Relative Water Content (RWC), protein assay and analysis, statistical approach for MDA and REL [86] PmRS Pm027594/Pm025896 Diminish the negative effects of cold Gene cloning, expression pattern analysis, subcellular localization, transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana, cold resistance analysis, transformation of Mei [107] PmBBX32 Pm013051 Diminish the negative effects of cold Expression pattern analysis, transformed Arabidopsis thaliana, low-temperature stress treatment, physiological index determination [95] PmCIPK5/6/13 Pm001690/Pm018300/

Pm008498Modulating the stress response to cold Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, qRT-PCR [103] PmNAC11/20/23/40/

42/48/57/59/60/61/

66/82/85/86/107Pm001403/Pm005783/ Pm006470/Pm011234/

Pm011603/Pm012630/

Pm015876/Pm017550/

Pm018292/Pm018442/

Pm019659/Pm024558/

Pm025184/Pm025307/

Pm025184/Pm025307/

Pm028721Involved in the cold-stress response Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, qRT-PCR [100] PmbHLH4/6/25/28/ 38/40/57 Pm002111/Pm002283/

Pm008898/Pm016406/ Pm018355/Pm023237Play a critical part in the resistance to low temperature stress Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, qRT-PCR [93,94] PmPUB1/3 Pm006753/Pm009248 Play a significant part in the regulatory network connected to low temperature stress Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, qRT-PCR, overexpression of tobacco, low-temperature treatment, physiological index measurement [87] PmWRKY18 Pm005698 Play a significant part in the regulatory network connected to low temperature stress, sensitive to ABA treatment Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, qRT-PCR, overexpression of tobacco, low-temperature treatment, physiological index measurement [87] PmWRKY57 LOC103321497 Function in improving cold tolerance of plants Cloning and sequence analysis, subcellular localization, transformation of A. thaliana, determination of plant physiological index, expression analysis of genes [102] PmSOD3 Pm003436 Had important regulatory roles in cold acclimation process Physiological index determination, section observation, tissue browning, ion leakage rate, infrared thermal imaging technology, and freeze thaw detection sensors [109] PmPOD2/19 Pm000967/Pm022119 Had important regulatory roles in cold acclimation process Physiological index determination, section observation, tissue browning, ion leakage rate, infrared thermal imaging technology, and freeze thaw detection sensors [109] PmNCED3/8/9 Pm005153/Pm011164/

Pm016267Significant role in the plant's response to cold stress Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, qRT-PCR [108] PmCSL − Significantly improved the freezing tolerance of transgenic plants Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, ATAC sequencing, gene cloning and gene expression analysis, plant transformation and low temperature treatment [97] PmHDAC1/6/14 Pm020717/Pm024325/

Pm012683Significantly respond to cold stress Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, qRT-PCR [98] PmbZIP 12/31/36/41/48 Pm005288/Pm020080/

Pm021804/Pm025001/

Pm029028Responses to low-temperature stress Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, qRT-PCR [99] PmSWEET1/12/13/14 Pm007697/Pm022696/

Pm024167/Pm024554Responses to cold stress Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, qRT-PCR [101] PmCDPK14 Pm026757 Play an essential role in resisting low temperature stress Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, qRT-PCR, compare between two genomes of Mei [105] PmMAPK3/5/6/20 Pm000966/Pm023935/

Pm027774/Pm014593Significantly respond to cold stress Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, qRT-PCR, compare between two genome databases of Mei [104] PmMAPKK2/3/6 Pm027015/Pm015648/

Pm027289Significantly respond to cold stress Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, qRT-PCR, compare between two genome databases of Mei [104] PmRCI2s Pm027750/Pm003262/

Pm003263Significantly induced by low temperature Bioinformatics analysis, expression pattern analysis, qRT-PCR [106] -

At present, a great deal of research has revealed that abiotic stress affects woody plants at many phases of their growth and development, such as seed germination, growth, flowering, and fruiting[110]. Drought stress was one of the main abiotic factors that Mei had to deal with; as a result, the plants became shorter and had fewer leaves[111,112]. Salt stress mostly reduced germination rate and altered bloom yield and branch length[113]. By subjecting annual branches of Mei to drought treatment, drought-responsive functional proteins PmCCD1/4/8 (carotenoidcleavage dioxygenase)[114] and PmLEA10/29[86], as well as PmTPS2/6 (Trehalose-6-phosphate synthase)[115] involved in trehalose synthesis, were discovered. By treating cultivars with varying degrees of drought tolerance, the important genes N-acetyl-serotonin methyltransferase (PmASMT1) and tryptophan 5- hydroxylase (PmT5H1), which were highly responsive to the melatonin production pathway were also found, and the corresponding physiological indices were ascertained by creating overexpressed plants[112]. Furthermore, a multitude of transcription factors that respond to drought were found, including PmbZIP5/29/35, PmbHLH35, PmWRKY2-1/2-2, PmZAT12 (zinc finger of arabidopsis thaliana12), and PmTALE1/3/6/13 (three amino acid loop extension)[116−120]. The genes PmbZIP, PmbHLH, PmWRKY, PmLEA, and PmCIPK that were previously found to be involved in freezing stress are also implicated in drought stress, indicating that several of the functional genes mentioned above respond to more than one abiotic stress. PmCCD1/4/8, PmZAT12, PmTALE1/3/6/13, and PmbZIP5/29/35 was also responsive to salt stress found in drought stress[99,114,116,119,120]. It is possible to identify and confirm the essential genes PmCIPK21, PmbHLH35, PmMYB, and PmNF-YA2/YB3 during salt stress by monitoring changes in physiological markers, such as Superoxide dismutase (SOD) and malondialdehyde (MDA)[117,121]. Apart from investigating the mechanism of salt stress on Mei using different bioinformation techniques, it was discovered that grafting could enhance salt resistance in practical breeding[122]. Grafted seedlings have the ability to greatly boost leaf photosynthesis in comparison to self-rooted seedlings. Furthermore, the majority of studies on temperature extremes have concentrated on low-temperature stresses. Nevertheless, when it comes to high temperature stress, it is discovered that high temperature has an impact on both the duration of the watching period and the overall viewing effect. Presently, PmHSP17.9 of the heat hormone protein (HSP) has been successfully screened and cloned[123], and its role in high heat has been successfully established through changes in physiological indexes following abiotic stress treatment.

Although the aforementioned genes for heat, drought, salt, and cold tolerance have been identified (Supplemental Table S4), and the corresponding genes have been obtained through preliminary cloning, the molecular mechanisms underlying resistance to abiotic stress remain unclear, and there is currently no ideal genetic transformation system. Furthermore, further research is required to understand how different stress factors interact with one another.

-

Mei, as a woody plant with a lengthy cultivation history, holds not only high ornamental value but also a unique cultural significance among many ornamental plants due to its special flowering season. The trees are naturally distributed and cultivated mainly in the Yangtze River basin and the regions south of the Yangtze River in China. 'Trekking in the snow in search of Mei' is a distinctive garden landscape in the Jiangnan region[79]. After decades of continuous research and practice, the number of Mei varieties has exceeded 450, classified into 11 species groups[4]. Several varieties of Mei can be grown in the open air in the Yellow River basin and areas north of it in China. Although some progress has been made in Mei breeding, the existing varieties can no longer meet the demands of today's horticultural market.

Currently, in terms of ornamental traits, Mei varieties with excellent cold resistance often lack noticeable floral fragrance. Weeping varieties and the Tortuous Dragon group are commonly planted in field settings. The long-term goal of Mei breeding is to cultivate new varieties with diverse floral styles, distinctive floral fragrances, colorful flowers, and strong cold resistance[124]. Thus, improving the ornamental quality while breeding Mei germplasm that is drought-resistant, cold-resistant, salt-resistant, heavy metal-resistant, moisture-resistant, and waterlogging-resistant will be another important research direction in ornamental plant breeding. Hybrid breeding, selective breeding, and bud mutation breeding are the main methods employed in breeding Mei. However, the limitations of traditional methods are gradually becoming apparent due to technological advancements and the high heterosis of Mei. Therefore, adopting new technologies to breed new high-quality varieties is also a long-term goal that needs to be pursued (Fig. 2).

Establishing a genetic transformation system for Mei

-

Mei resources have irreplaceable ornamental and humanistic values in the process of human social development. Tissue culture research of woody plants enables asexual reproduction of forest trees and preservation of excellent germplasm resources, providing a foundation for establishing a genetic transformation system. Mei currently needs to establish a set of perfect expression system, and utilize the efficient genetic transformation system to further clarify the function of specific genes. Several previous studies have documented transient transformation of Mei protoplasts and genetic transformation systems for immature or mature cotyledons[125,126]. These transformation systems serve as references for optimizing experimental settings and improving the efficiency of genetic transformation. However, compared to functional validation of other woody plants, Mei is currently limited to model plants or even herbaceous model plants. In recent years, the gene editing technologies led by CRISPR/Cas have been developing rapidly, and the successful establishment of plant genetic transformation systems is a necessary prerequisite for the application of such technology, highlighting the evident importance of establishing a transformation system.

New technical approach to Mei

-

Given the rapid advancement of genomics and its application in the expansion of new Mei varieties, analyses at multiple levels such as signal transduction, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, etc., have gradually revealed the mechanisms underlying the important ornamental characteristics of Mei. However, these studies have been limited to model plants and some crop species, with relatively few studies conducted on woody plants. With the third generation of improved single-molecule sequencing technology (e.g., HiFi reads (high-fidelity reads)) and high-C aided assembly technologies, coupled with the decreasing cost of gene sequencing, genomic studies on various species of Mei have become feasible. In addition, there is still a long-term challenge in terms of the lack of sufficient mutational resources for molecular cloning, functional characterization, and annotation of genes responsive to adversity stress in Mei[127]. In recent years, the combined application of IGS and CRISPR/Cas9 technologies has provided broad prospects for future functional analysis in Mei[128]. This technology has been researched and applied in this plant regarding stress tolerance, regulation of flowering time, and alteration of tree shape. However, since Mei has not yet established a complete system of regeneration by histoculture and a stable system of genetic transformation, it is not possible to utilize biotechnology such as gene editing to carry out genetic improvement. Therefore, it is necessary to develop and improve the genetic transformation system of Mei in order to expand the scope of application of the CRISPR/Cas system. In the future, we will enhance the quantity and quality of the genome, jointly resequencing the transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome for multi-omics analysis, and construct a gene regulatory network to fully understand the regulation and interaction between different genes. This will help us comprehend the molecular mechanisms underlying the growth, development, and formation of important traits in Mei. Subsequently, relying on the mature genetic transformation system and the application of new technologies such as CRISPR/Cas9, we will continue to breed new varieties with ornamental traits and excellent resistance of Mei. Continued advancements in these techniques are expected to further propel Mei research and contribute to the sustainable utilization of Mei resources.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: visualization: Fan D, Wen Z, Liu X; methodology: Miao R; writing – review & editing and formal analysis: Sun L; writing – original draft: Fan D, Miao R, Lv W, Meng J, Cheng T, Zhang Q. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

This study was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (QNTD202306); Forestry and Grassland Science and Technology Innovation Youth Top Talent Project of China (No. 2020132608) and Beijing High-Precision Discipline Project, Discipline of Ecological Environment of Urban and Rural Human Settlements.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Lidan Sun is the Editorial Board member of Ornamental Plant Research who was blinded from reviewing or making decisions on the manuscript. The article was subject to the journal's standard procedures, with peer-review handled independently of this Editorial Board member and the research groups.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Dongqing Fan, Runtian Miao

- Supplemental Table S1 Functional validation information of Flower color.

- Supplemental Table S2 Functional validation information of Flower morphology.

- Supplemental Table S3 Functional validation information of Weeping traits.

- Supplemental Table S4 Functional validation information of other resistance.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Fan D, Miao R, Lv W, Wen Z, Meng J, et al. 2024. Prunus mume genome research: current status and prospects. Ornamental Plant Research 4: e006 doi: 10.48130/opr-0024-0004

Prunus mume genome research: current status and prospects

- Received: 25 October 2023

- Revised: 02 January 2024

- Accepted: 05 January 2024

- Published online: 04 March 2024

Abstract: Mei (Prunus mume) is an excellent garden tree highly praised in China, possessing both ornamental and cultural values. Breeding Mei with distinctive characteristics and high resistance has become a long-term goal to meet the visual and spiritual demands in the new era. With the rapid development of biotechnology, researchers have successively completed the whole genome sequence and resequencing of Mei, and continue to employ advanced techniques to investigate the formation mechanisms of important ornamental traits and stress resistance traits in Mei. Thus, the groundwork has been established for achieving the breeding objectives. In this article, we provide an overview of the development and expansion of genome projects over the past decade, including whole-genome sequencing, resequencing, and genetic mapping. We further present a concise summary of the research progress made in understanding major ornamental traits and cold resistance traits. These accomplishments hold great promise for significantly enhancing the efficiency of Mei and further realizing breeding goals.

-

Key words:

- Genome mapping /

- Resequencing /

- Functional genomics /

- Mei /

- Breeding