-

Herbaceous peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.) is a prominent traditional plant in China. In recent decades, herbaceous peony has become increasingly popular worldwide as a novel cut flower. However, the short natural florescence of the flower is a serious problem limiting its extensive utilization in the cut-flower industry. Therefore, delaying flower senescence and extending vase life are essential issues in herbaceous peony research. To date, studies on the physiological and biochemical mechanisms of flower aging have primarily concentrated on water metabolism, biomacromolecule metabolism, membrane lipid peroxidation, and changes in antioxidant enzymes, especially endogenous hormones.

Hormones play crucial roles during plant senescence. In flowers sensitive to ethylene, ethylene functions as a regulator of senescence[1]. Abscisic acid (ABA) is involved in the senescence process of flowers[2], while gibberellins (GAs) act as anti-senescence factors[3]. Studies have offered proof of an intricate and sophisticated interplay among phytohormones, an imbalance in phytohormone levels accelerates flower senescence[4,5]. GA and ethylene exhibit an antagonistic relationship[6], whereas ABA may promote senescence by enhancing ethylene synthesis[7,8].

A water deficit in cut stems has a direct relationship with the turgidity of cut flowers and will accelerate senescence. The causes of earlier wilting in cut flowers include a lower ability to close stomata in response to water stress conditions, and physical blockage of xylem vessels[9]. Preservatives may enhance water uptake, resulting in a longer vase life for flowers. Biomacromolecule metabolism encompasses the degradation of sugar, protein, RNA, and DNA. Sugar metabolism is active in senescent cells[10]. The degradation of RNA and DNA is a typical trait during the senescence of floral parts[11,12]. Specific nuclease activities capable of degrading both RNA and DNA have been demonstrated in various flower systems[13,14]. Petal death is marked by decreased membrane permeability, increased oxidative stress, and lowered antioxidative enzyme levels[15]. Malondialdehyde (MDA) is an index of lipid peroxidation. Plants have a distinct antioxidant system that eliminates harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS)[16]. The antioxidant protection system encompasses α-tocopherol, ascorbic acid, glutathione, flavonoids, and phenolic compounds, as well as enzyme systems, including catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and peroxidase (POD)[17].

The lifespan and quality of cut herbaceous peony flowers could be altered by modulating physiological and biochemical changes during senescence. For example, sucrose and glucose could enhance the vase life of cut peonies by enhancing water balance and decreasing sensitivity to ethylene[18]. The quality of herbaceous peony cut flowers could be prolonged by nanosilver treatment. The application of this treatment led to an enhancement in soluble protein content and a decrease in the accumulation of MDA, O2–, H2O2, and other detrimental substances. This was primarily due to the increased activities of protective enzymes, including SOD, CAT, and APX, which effectively eliminates ROS[19]. However, despite these observations, the underlying physiological and biochemical mechanisms of herbaceous peony flower senescence are still not comprehensively understood, and the interrelationships among them are still unclear.

Currently, the main methods for delaying herbaceous peony flower senescence involve using vase solutions such as ethylene inhibitors, preservatives, and antioxidants. Han found that 20 g/L sucrose + 250 mg/L citric acid + 0.04 mmol/L melatonin had a good preservation effect and extended the vase life of cut herbaceous peony flowers[20]. Spraying different formulations of biocide before harvest can delay flower senescence[21]. As molecular biology progresses, several functional genes and transcription factors that regulate herbaceous peony flower senescence have been discovered. The PlSVP gene uniquely repressed flowering time, potentially by suppressing the expression of genes such as FT, AP1, SOC1, and LFY[22]. A MYB transcription factor, PlMYB308, contributed to the senescence of herbaceous peony flowers by mediating the production of ethylene[23]. In the process of synthesizing ABA, PlZFP bound directly to the promoter of PlNCED2, and accelerated herbaceous peony flower senescence[24]. Silencing PlMYB308 or PlZFP using virus-induced gene silencing technology (VIGS) could extend the flower longevity of herbaceous peony. Utilizing modern molecular biology techniques to isolate and conduct functional validation of senescence-related genes, and finding more effective molecular biological methods for delaying flower senescence will be the focus of future research.

The value of herbaceous peony flowers as a commodity primarily hinges on their superior flowering quality and extended vase life. Hence, understanding the physiological and biochemical processes involved in flower senescence, as well as methods to extend their vase life, are crucial areas of postharvest physiological research. In this study, the physiological and biochemical indicators were investigated to clarify their interrelation and function during herbaceous peony flower senescence. Meanwhile, we constructed a new postharvest preservation approach that combines the optimization of VIGS and the use of vase solution to delay herbaceous peony flower senescence. Our results will provide a new insight into the postharvest research of herbaceous peony.

-

Flowers of herbaceous peony growing in the germplasm resource garden of Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University under natural conditions were selected for the present study. Flowers were uniformly harvested during the bud stage. All petal samples, obtained at different stages, were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

The process of flower development and senescence was categorized into five distinct stages (I−V), which were designated the pencil stage (I), partially open stage (II), open stage (III), partially senescent stage (IV), and senescent stage (V). We recorded the visible changes throughout the process of flower development and senescence in Supplementary Fig. S1. Simple flower 'Hangshao' boasts large petals, with neither stamens nor pistils exhibiting petaloidy, and its flower opening and senescence processes are easily distinguishable. Therefore, it is chosen as the cultivar for developing a new postharvest preservation approach.

Measurements of the content of soluble sugar, soluble protein, and MDA in the petals

-

Soluble sugars were extracted using 70% ethanol. The absorbance of the samples was measured in OD at 485 nm. The soluble protein content was determined using the method described by Bradford[25]. The optical density was determined in OD at 595 nm, with the protein reagent serving as the blank reference.

We utilized the technique outlined by Heath & Packer[26], which involves evaluating the MDA complex in plants. The peak absorbance of the MDA complex was determined in OD at 532 nm, with an additional measurement at 600 nm to adjust for nonspecific turbidity.

Determination of enzyme activities

-

The method outlined by Wissemann & Montgomery[27] was used to determine PPO activity. One unit of PPO activity was characterized by an increase of 0.01 in OD value at 410 nm per minute. The POD activity was assayed using a modified version of the method described by Hassan et al.[28]. The POD activity was measured as the change in OD at 470 nm over 3 min. SOD activity was determined by observing the inhibition of nitro-blue tetrazolium (NBT) photoreduction, following the procedure described by Beyer & Fridovich[29]. One unit of SOD activity was defined as the amount of enzyme needed to inhibit 50% of the NBT reduction, as measured in OD at 560 nm. CAT activity was measured by observing the reduction in absorbance at 240 nm caused by hydrogen peroxide decomposition. The reaction was initiated with the addition of H2O2, and the change in absorbance was recorded after 1 min.

Determination of total antioxidant compounds

-

The collected samples were frozen and dried, and then pulverized and ultrasonically extracted with pure methanol. The phenolic content of various samples was assayed using the Folin and Ciocalteu method[30]. The absorbance in OD at 760 nm was measured using the spectrophotometer. The phenolic content was calculated using a gallic acid equivalents (GAE) calibration curve, and the results were reported as milligrams of GAE per gram of dry weight (mg GAE/g DW).

The flavonoid content of various samples was assayed using the trichloride colorimetric method. The absorbance was measured in OD at 510 nm. The flavonoid content was calculated using a rutin equivalents (RE) calibration curve, and the results were reported as milligrams of RE per gram of dry weight (mg RE/g DW).

Determination of antioxidant activity

-

The DPPH radical scavenging activity was assessed using a modified version of the method described by Brand et al.[31]. Each sample was prepared by mixing 2 mL of phytoextract with 2 mL of DPPH. The samples were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance was then measured in OD at 517 nm. The scavenging activity was calculated using the formula: [(Abs0 − Abs1)/Abs0] × 100%, where Abs0 represents the control absorbance and Abs1 represents the sample absorbance. To assess antioxidant activity, 2 mL of phytoextract was combined with 2 mL of the diluted ABTS solution. The samples were allowed to sit in the dark at room temperature for 8 min before measuring the absorbance at 732 nm. The antioxidant capacity of a sample was evaluated using the FRAP (Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma) assay[32]. 0.2 mL of phytoextract was mixed with 1.8 mL of FRAP reagent and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. The absorbance of the mixture was then measured at 593 nm.

The antioxidant activities of DDPH, ABTS, and FRAP assays were compared using a Trolox calibration curve, and the results were reported on a dry weight basis as Trolox equivalents per 100 g (g TE/100 g DW).

Measurement of endogenous hormone content

-

ABA and GA content was measured using an ELISA kit. The manufacturer's instructions were followed for the extraction, purification, and quantification of ABA and GA content. The detected levels of endogenous phytohormones were statistically analyzed, with the levels calculated using their respective conversion formulas and detection values from the enzyme labeling instrument. Ethylene production was determined following the procedures outlined by Chang et al.[33], where 0.5 g of petals were placed in an airtight tube and incubated at 24 °C for 5 h. Subsequently, 1 mL of gas was injected into the gas chromatograph to measure ethylene production.

Optimization of VIGS technology

-

To select the most suitable VIGS infection method for herbaceous peony cut flowers, we tried the syringe injection method, the vacuum infection method, and the vase solution absorption method, and compared the treatment effect of these three methods. After being infected with these three VIGS treatments, the cut flowers were cleaned with sterile water and refrigerated at 8 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, the flowers were placed in water or vase solution. The growth conditions of these flowers were observed and recorded daily.

Vase solution treatment

-

From 6:00 to 7:00 am, cut flowers were collected from the resource nursery. Flower buds that were slightly loose and in good growth condition were selected, and the stems were trimmed to about 30 cm in length. The cut flowers were immediately inserted into a bucket filled with water and brought back to the laboratory within 30 min. The flower branches were trimmed to a length of about 25 cm with two compound leaves left on, and then inserted into distilled water. The cut flowers were placed at room temperature under scattered light, and their growth conditions were observed and recorded every day.

Statistical analysis

-

The data were analyzed in Microsoft Excel 2010 and reported as the means and the standard deviation of three measurements.

-

We used 25 cultivars with five different colors of herbaceous peony, including red, pink, white, purple and yellow, as our study subject (Supplementary Fig. S1). Since ethylene, ABA, and GA are important hormones regulating flower senescence, we examined their content changes during the five stages described above.

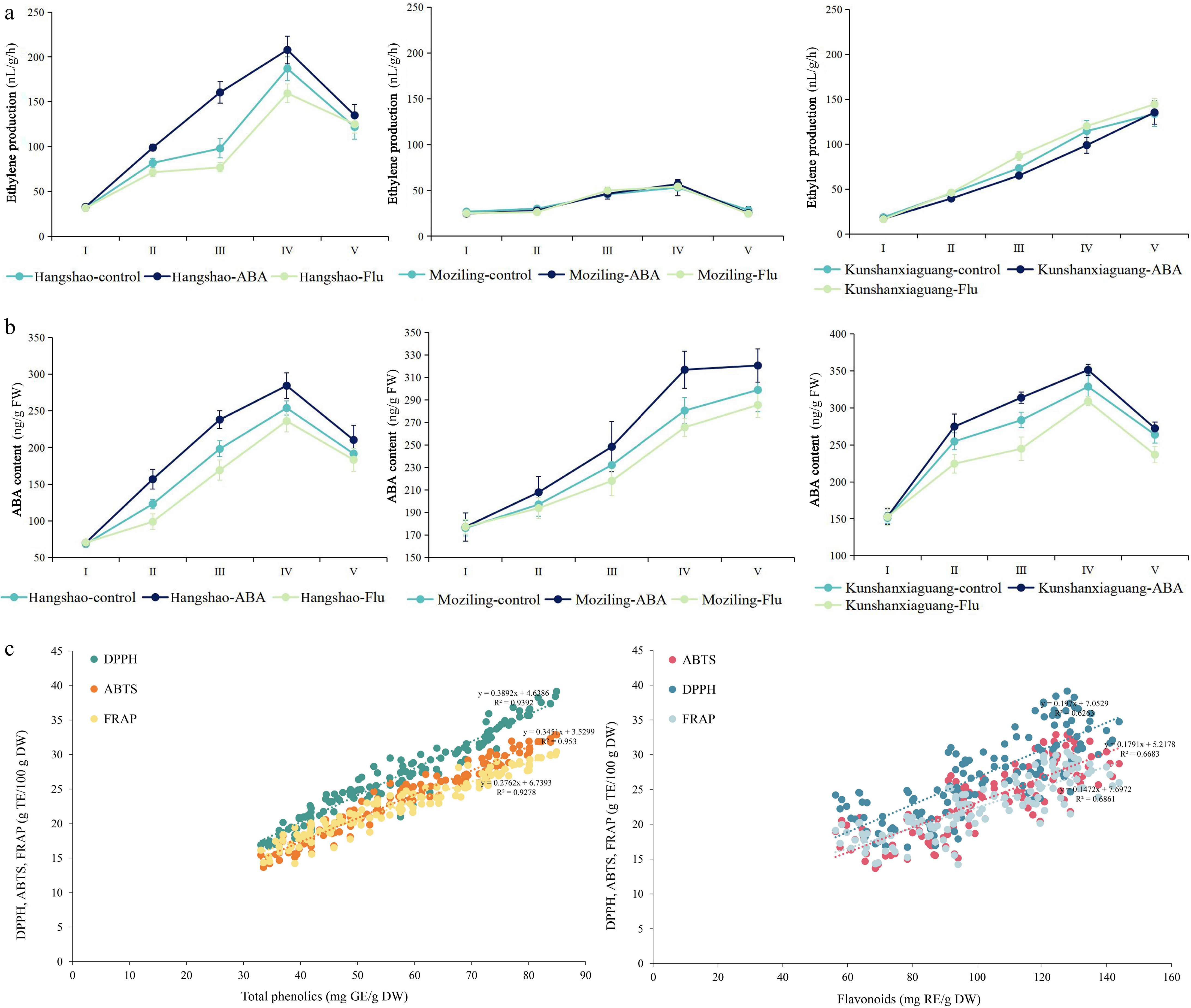

A significant difference could be observed in ethylene production between the different cultivars. According to the ethylene production trend, the 25 cultivars could be classified into three types: the climacteric type, the non climacteric type, and the type with a later stage increase. As shown in Fig. 1a, the climacteric type, whose ethylene production increased gradually during opening, peaked at the full open phase, and then decreased, included 'Hangshao', 'Yellow Crown', 'Coral Charm', 'Hillary', 'Lollipop', 'Canary Brilliants', 'Cora Louise', 'Buckeye Belle', 'Red Charm', 'Lanju', 'Liantai', and 'Duchesse de Nemours'. The non climacteric type, whose ethylene production either decreased or remained at a relatively stable level from opening to senescence, included 'Red Sarah Bernhard', 'Lanfushi', 'Fenfurong', 'Rosea Plena', 'Moziling', 'Cheddar Cheese', 'Sarah Bernhardt', 'Hongfushi', 'Old Faithful', and 'Pietertje Vriend Wagenaar'. The type with the later stage increase, whose ethylene production increased during opening and peaked at senescence, included 'Festiva Maxima', 'Kunshanxiaguang', and 'Gardenia'. The ABA content of these herbaceous peony cultivars exhibited a tendency to increase first and then decrease but still maintained a high level at stage V compared with early stages, except for 'Festiva Maxima', 'Liantai', 'Rosea Plena', 'Moziling', and 'Old Faithful', which showed a continuous increase in ABA content (Fig. 1b). The content of GA3 was high in the early stages and then declined rapidly until stage V, where it reached its lowest level (Fig. 1c). To further understand the role of GA in herbaceous peony flower senescence, we also measured the content of GA1, GA4, and GA7. The content of GA1 and GA4 were high in stages I and II, then declined rapidly until stage V (Supplementary Fig. S2a, b). The content of GA7 remained at a lower level compared to the other three gibberellins, but it also peaked at stage I or stage II (Supplementary Fig. S2c). These results suggested that GA content may negatively correlate with herbaceous peony flower senescence and that ABA content and ethylene production may positively correlate with herbaceous peony flower senescence.

Figure 1.

Changes in content of phytohormone during herbaceous peony senescence. (a) Changes in ethylene production. (b) Changes in ABA content. (c) Changes in GA3 content. Error bars show the SD of the means of three biological replicates.

Changes in physiological indicators related to membrane permeability during herbaceous peony senescence

-

To investigate the degree of membrane permeability and membrane lipid peroxidation and related physiological indices, we measured the activities of SOD, CAT, POD, and PPO, as well as the MDA content. Furthermore, we used electrolyte leakage to represent membrane permeability. As shown in Fig. 2a, at stage I, the activities of SOD, CAT, POD, and PPO in a few cultivars were higher than those at the next stage. However, on the whole, both POD and PPO activities increased in the first four stages and then decreased significantly in stage V. SOD and CAT activities rose to a maximum at stage III and declined significantly at stage IV, except for a persistent decrease in the activity of individual cultivars and a high activity of individual species at stage I. PPO and POD activities decline later than SOD and CAT activities possibly because ROS inhibit enzymes associated with phenols slightly. These results indicated that SOD, CAT, POD, and PPO played some roles in protecting cells. The MDA content and membrane permeability in all cultivars exhibited a significant increase with the senescence progression, and the highest MDA content and membrane permeability were observed at stage V. This result demonstrated that the integrity of the herbaceous peony cytomembrane structure was gradually destroyed with floral senescence.

Figure 2.

Longevity of different cultivars of herbaceous peony flowers and their changes in physiological indicators during herbaceous peony senescence. (a) Changes in POD, PPO, SOD, CAT activity, MDA content, and membrance permeability. (b) Changes in soluble sugar content. (c) Changes in soluble protein content. (d) Changes in water balance. (e) Longevity of different herbaceous peony cultivars. (f) Changes in total phenolic and flavonoid content and activity of three antioxidants. Error bars show the SD of the means of three biological replicates.

Taken together, these results suggest that both cytomembrane permeability and cytomembrane lipid peroxidation become more severe with herbaceous peony senescence and that antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, POD, and PPO) play a role in protecting cells.

Changes in the content of soluble sugars during herbaceous peony senescence

-

Soluble sugars serve as vital osmolytes in numerous plants, safeguarding cells from oxidative harm. We speculated that changes in soluble sugar content may affect herbaceous peony senescence. Indeed, we found that the soluble sugar content of 23 cultivars, which included 12 climacteric type cultivars and 10 non climacteric type cultivars, first increased and then decreased (Fig. 2b) during the five stages. Furthermore, in all climacteric type cultivars, the soluble sugar content increased during the first three stages, peaked at stage III, and then decreased during the last two stages. In most non climacteric type cultivars, the content of soluble sugar increased during the early four stages, reaching its highest at stage IV, and then decreased at stage V. Only two cultivars, 'Cheddar Cheese' and 'Pietertje Vriend Wagenaar', had the same changes as climacteric type cultivars. In addition, we noticed that the climacteric type had a lower average soluble sugar content than the non climacteric type throughout the senescence period. The later decline in soluble sugars in the non climacteric type cultivars compared with the climacteric type cultivars may explain this observation. These results suggested that the change in soluble sugar content was related to the type of response of cultivars to ethylene.

Longevity of different herbaceous peony flower cultivars and changes in soluble protein content and water balance

-

From stage I to stage V, we recorded the vase life of herbaceous peonies and measured their soluble protein content as well as the water balance. The concentration of soluble proteins in all cultivars increased as the development and senescence progressed and then gradually declined during senescence (Fig. 2c). The water balance declined in the early days, followed by a slight increase. It is positive at first bloom when water uptake was greater than water loss, and negative after bloom when water loss was greater than water uptake (Fig. 2d). The vase life of the cut flowers is shown in Fig. 2e. Interestingly, the relationship observed is that cultivars with a later point of water balance reaching zero tend to have a longer vase life.

Changes in the total phenolic and flavonoid content and activities of the three antioxidants

-

As phenolic compounds and flavonoids are part of the antioxidant protection system and are extremely abundant in herbaceous peonies, we determined their content throughout the development and senescence stages. In addition, DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP activities were measured to assess the antioxidant capacity. As shown in Fig. 2f, different flower cultivars exhibited diverse ranges of antioxidant capacities, phenolic content, and flavonoid content. Among them, the red and purple cultivars have the highest content of total phenolics and flavonoids, the strongest DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activities, and the strongest cupric reducing capacity, with the yellow, pink, and white cultivars following behind. We hypothesized that the ability of the herbaceous peony to resist scavenging free radicals is related to the content of total phenols and flavonoids, which in turn is related to the color shade of the flowers.

The total phenolic content of those flowers decreased gradually from stage I to stage V; whereas the flavonoid content increased gradually, with the exception of a few cultivars. Three antioxidative activities (DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP) were observed to increase with flower development and senescence (Fig. 2f). These results suggested that, in herbaceous peonies, the phenolics participate in the antioxidant process, while the flavonoids may not be the main contributors. As the flowers underwent senescence, the total phenolic content decreased, and the antioxidant capacity decreased. Instead, most flavonoids may be unaffected by POD, as their content increases.

The optimization of VIGS and the use of vase solution can extend herbaceous peony flower longevity

-

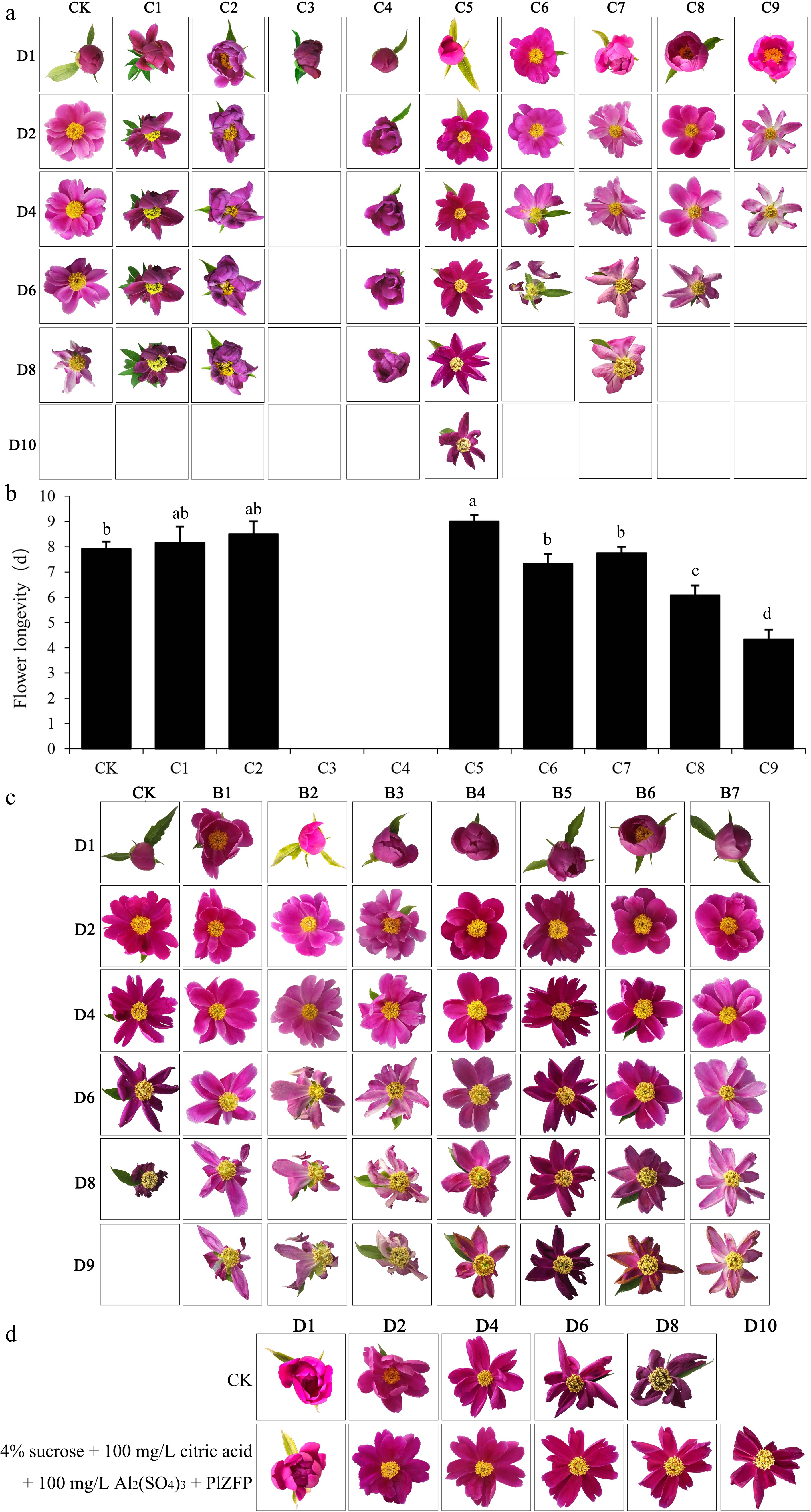

Our previous studies have shown that silencing the senescence-related transcription factor PlZFP by VIGS can delay flower senescence in herbaceous peony[24]. In this study, we used the syringe injection method, the vacuum injection method, and the vase solution absorption method to optimize VIGS technology, and the operation process is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. The optimization process of VIGS technology.

Number Method Process C1 The syringe injection method 0.25 mL of the VIGS bacterial solution was injected into the cut flower from the bottom of the bud using a syringe. C2 0.5 mL of the VIGS bacterial solution was injected into the cut flower from the bottom of the bud using a syringe. C3 1.0 mL of the VIGS bacterial solution was injected into the cut flower from the bottom of the bud using a syringe. C4 The vacuum infection method When the bud was relatively hard and the petals were tightly closed, the entire bud was immersed into the VIGS bacterial solution for 10 min, under a vacuum at 0.7 atm. C5 When the bud was relatively soft and the petals were loose, the entire bud was immersed into the VIGS bacterial solution for 10 min, under a vacuum at 0.7 atm. C6 When the bud was open, revealing the stamens and pistils, the entire bud was immersed into the VIGS bacterial solution for 10 min, under a vacuum at 0.7 atm. C7 The vase solution absorption method The cut flowers were inserted into the VIGS bacterial solution with an OD value of 0.25 for 24 h. C8 The cut flowers were inserted into the VIGS bacterial solution with an OD value of 0.5 for 24 h. C9 The cut flowers were inserted into the VIGS bacterial solution with an OD value of 1.0 for 24 h. Figure 3a, b presents the calculated flower longevity and phenotypic changes after different VIGS injections. The syringe injection method affected the growth of petals and shortened the flower longevity. For the vacuum infection method, a lower concentration of bacterial solution had no obvious effect on delaying flower senescence, while a higher concentration blocked the vascular bundles and reduced the flower longevity. For the vacuum infection method, when the bud was relatively hard and the petals were tightly closed, the flowers could not open after vacuum infection; when the bud was open, revealing the stamens and pistils, the petals fell off easily after vacuum infection; when the bud was relatively soft and the petals loose, this method had the best effect, extending flower longevity by about 1 d. QRT–PCR was used to detect gene expression in cut flowers on the fourth day after treatment. Comparing the CK (without the VIGS treatment) and C5 flowers, the PlZFP gene transcript was downregulated in the PlZFP-silenced flowers (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 3.

Phenotypic statistics and flower longevity of cut flowers after different treatment. (a) Phenotypic statistics of cut flowers after different VIGS treatment. (b) Flower longevity after different VIGS treatment. Different letters indicate significant differences at the p ≤ 0.05 level by Duncan test. (c) Phenotypic statistics of cut flowers after different vase solutions treatment. (d) Phenotypic statistics of cut flowers after vase solutions and VIGS treatment. Error bars show the SD of the means of three biological replicates.

We also studied the effect of vase solutions on extending flower longevity (Fig. 3c). The results indicated that all formulas of vase solution had the effect of delaying flower senescence. Among them, 4% sucrose +100 mg/L citric acid +100 mg/L Al2(SO4)3 had the best effect, and the longevity of the cut flowers was increased by 23% compared with the control (Table 2). The concentration of every single component and the effect of the vase solutions are shown in Supplementary Tables S1−S4.

Table 2. Effect of vase solutions on senescence of cut herbaceous peony flowers.

No. Formulas of vase solutions Opening days (d) Blooming days (d) Vase life (d) CK Water 2.17 ± 0.14b 3.42 ± 0.38b 7.92 ± 0.58c B1 4% sucrose + 100 mg/L citric acid 2.08 ± 0.29b 4.08 ± 0.14a 9.33 ± 0.14b B2 4% sucrose + 100 mg/L Al2(SO4)3 2.42 ± 0.29ab 4.17 ± 0.14a 9.50 ± 0.43ab B3 4% sucrose + 200 mg/L 8-HQS 2.33 ± 0.14ab 4.00 ± 0.25ab 9.25 ± 0.25b B4 4% sucrose + 100 mg/L citric acid + 100 mg/L Al2(SO4)3 2.58 ± 0.29a 4.17 ± 0.14a 9.75 ± 0.25a B5 4% sucrose + 100 mg/L citric acid + 200 mg/L 8-HQS 2.42 ± 0.14ab 4.08 ± 0.38a 9.33 ± 0.38ab B6 4% sucrose + 100 mg/L Al2(SO4)3 + 200 mg/L 8-HQS 2.50 ± 0.25ab 4.00 ± 0.25ab 9.58 ± 0.14ab B7 4% sucrose + 100 mg/L citric acid + 100 mg/L Al2(SO4)3 + 200 mg/L 8-HQS 2.50 ± 0.25a 4.08 ± 0.14a 9.67 ± 0.38ab Different letters indicate significant differences using one-way ANOVA test at p < 0.05. Since both VIGS technology and vase solutions can effectively prolong the longevity of flowers, we combined them to develop a new postharvest preservation approach to extend flower longevity. The effect of vase solutions and VIGS treatment on extending flower longevity is shown in Fig. 3d. This new approach can extend the longevity of herbaceous peony flowers by 30% (Table 3).

Table 3. Effect of vase solutions and VIGS on senescence of cut herbaceous peony flowers.

Treatment Opening days (d) Blooming days (d) Vase life (d) CK 2.25 ± 0.25a 3.25 ± 0.25b 8.08 ± 0.38c 4% sucrose + 100 mg/L citric acid + 100 mg/LAl2(SO4)3 + PlZFP 2.17 ± 0.29a 4.58 ± 0.14a 10.67 ± 0.29a Different letters indicate significant differences using one-way ANOVA test at p < 0.05. -

Ethylene plays a crucial role as a plant hormone in the senescence process of flowers. As is the case in fruit, flowers can be categorized as being climacteric or non climacteric[34]. In some flowers, there may not be just two types. For example, according to the laws of respiration and ethylene production during flower senescence, roses were classified into three types: the climacteric type, the non climacteric type, and the increasing during the later stage type[35,36]. In a study by Jia et al., 13 cultivars of tree-peony were categorized into three groups similar to the above, according to significant differences in ethylene production. In our study, there were also significant differences in ethylene production during the senescence of different herbaceous peony cultivars[37]. The 25 herbaceous peony cultivars could be classified into three types: the climacteric type, the non climacteric type, and the type with the later stage increase, similar to the rose and tree peony.

ABA may play a role in triggering ethylene biosynthesis in the climacteric type of herbaceous peony

-

In cut carnations, a climacteric type flower, ABA accumulation precedes ethylene accumulation during senescence[38]. Moreover, Ying & Chen suggested that ethylene directly caused petal wilting, while ABA indirectly caused flower senescence by influencing ethylene production[39]. In a study by Onoue et al., the release of ethylene was accelerated by treating cut carnations with exogenous ABA[40]. These results suggest that ABA may play a role in inducing ethylene production during natural senescence in carnations. In our study, we detected changes in the content of ethylene, ABA, and GA3 during the five stages from flowering to senescence. There was no significant correlation between ABA content and ethylene content in these 25 herbaceous peony cultivars. However, we observed that in these 25 herbaceous peony cultivars, the accumulation of ABA preceded that of ethylene, and the peak of ABA content also preceded the peak of ethylene production, except in 'Rosea Plena'. We then chose 'Hangshao' (the climacteric type), 'Moziling' (the non climacteric type), and 'Gardenia' (the type that increases during the later stage) for hormone treatment. We found that after exogenous ABA treatment in 'Hangshao', the production of endogenous ethylene and ABA was higher than that in untreated controls; in 'Moziling', the endogenous ABA content was higher than that in untreated controls, but the production of endogenous ethylene was similar to that in untreated controls; and in 'Gardenia', the endogenous ABA content was higher than that in untreated controls, but the production of endogenous ethylene was slightly lower than that in untreated controls. After fluridone (Flu: an inhibitor of ABA) treatment, in 'Hangshao', the production of endogenous ethylene and ABA was lower than that in untreated controls; in 'Moziling' and 'Gardenia', the endogenous ABA content was lower than that in untreated controls, but the production of endogenous ethylene was similar to that in untreated controls (Fig. 4a, b). Based on these results, we hypothesized that ABA accumulation might play a role in triggering ethylene biosynthesis in the climacteric type of herbaceous peony cultivars but has no effect in the non climacteric type and the type that increases during the later stage.

Figure 4.

Ethylene production and ABA content in 'Hangshao', 'Moziling', and 'Kunshanxiaguang' after ABA and Flu treatment, and scatter diagram of the antioxidant activity with total phenolics/flavonoids. (a) Changes in ethylene production during 'Hangshao', 'Moziling', and 'Kunshanxiaguang' senescence after ABA and Flu treatment. (b) Changes in ABA content during 'Hangshao', 'Moziling', and 'Kunshanxiaguang' senescence after ABA and Flu treatment. (c) Scatter diagram of the antioxidant activity with total phenolics and total flavonoids.

Total phenolics were highly involved in antioxidant activity, but flavonoids were partly involved

-

Total phenols are considered a crucial marker for evaluating antioxidant content in tissues, often reported to rise initially during senescence to mitigate oxidative stress[41,42]. In the present experiment, an increase in the content of total phenols before flower senescence was observed, which further supported the above concept. Subsequently, the content of total phenols decreased as the peonies underwent senescence. The decrease in content might be due to the accumulation of ROS, which in turn inhibited the total phenolic content. The changes in antioxidant activity had the same tendency as the total phenolic content, which indicates that there is a high correlation between them. However, flavonoids exhibited a contrary change, and no correlation with antioxidant activity was observed. Past research indicates that as rose petals senesce, flavonoid, and anthocyanin levels rise, leading to the development of a deep blue shade in the petals[6]. Although not as noticeable as in roses, peony petals also turn slightly blue with age. It is possible, therefore, that flavonoids are more related to color change than to antioxidant activity. We have plotted scatter diagrams to show the relationship between total phenols and antioxidant activity, as well as the relationship between flavonoids and antioxidant activity. Based on analyzing the scatter diagram of the antioxidant activity with total phenolics/flavonoids (Fig. 4c), we supposed that total phenolics were highly involved in antioxidant activity, but flavonoids partly participated.

ABA and ethylene may influence the accumulation of soluble sugar and protein

-

During photosynthesis, sugar serves as a primary product of carbon and energy, playing a crucial role in plants. The longevity of flowers is linked to their sugar content. In typical cases, flowers with higher sugar content tend to have a longer vase life, while those with lower sugar content have a shorter one[43]. The application of external sugar can effectively postpone the visible indicators of senescence in many cut flowers[44]. In many ethylene-sensitive flowers, sugar often interferes with ethylene biosynthesis and signaling during postharvest development[45−48]. Furthermore, ABA promoted the biosynthesis of sugar in plants under abiotic stress conditions[49]. The transcription factor MdAREB2, which responds to ABA, directly enhances the expression of genes related to amylase and sugar transport, promoting the accumulation of soluble sugars[50]. Proteins are also important in plant growth and development. As mentioned in the essay by Gurmani et al., ABA was the most effective at increasing the level of soluble protein. These results show that there is a correlation between soluble sugar or protein content, and ABA or ethylene[51].

In our study, we found that the changes in protein and soluble sugar content were similar to those seen with ABA content. In the climacteric type, ABA content first increased and then decreased. Similarly, the protein and soluble sugar contents rose at early stages and peaked when the flower was completely opened and then fell. In both the non climacteric type and the type with increases during the later stage, the ABA content increased and remained at a high level. The soluble sugar and protein content also remained at a high level, only decreasing in the final stage. We noticed from Fig. 5 that soluble sugar and protein content were significantly and positively correlated with ABA content. Thus, we speculated that soluble sugar and protein accumulation were induced by ABA. At the beginning of flowering, and with a low concentration of ABA, ABA may induce the accumulation of soluble sugar and protein. As flowers continue to senesce, the soluble sugar and protein contents gradually increase. When the ABA content reaches its peak, a high concentration of ABA may inhibit the production of soluble sugar and protein, causing the soluble sugar and protein contents to fall.

The changes in soluble sugar and protein contents were also related to the type of response of cultivars to ethylene. The climacteric type cultivars had a lower average soluble sugar and protein content than the non climacteric type cultivars throughout the senescence period, and the decrease in soluble sugar and protein in the climacteric type occurred earlier than in the non climacteric type. We predict that soluble sugar and protein content may influence the type of response of cultivars to ethylene and that high sugar and protein contents may cause non climacteric ethylene response. However, very little was found in the literature on the relationship between soluble sugar and protein content and the type of response to ethylene, and there is a need for further research to determine their correlation.

The optimization of VIGS and the use of vase solutions constitute a novel and effective postharvest preservation approach

-

The current preservation technology for extending the vase life of flowers primarily relies on chemical preservation. Chemical preservation prolongs vase life by regulating the physiological and metabolic processes of cut flowers after harvesting using chemical reagents. The main components utilized in chemical preservation encompass water, inorganic salts, sugars, organic acids, bactericides, and hormones. Sugar is one of the common components in cut flower vase solutions, serving as the source of nutrition and energy for postharvest cut flowers. Treatment with sucrose boosted the accumulation of hexoses in floral buds and elevated the activity of cell wall invertase in the perianth[52]. In this study, the optimal sucrose concentration for 'Hangshao' was 4%. Sucrose can readily lead to the proliferation of microorganisms, which may impede the water absorption of flower stems. This could explain why the vase life of flowers treated with 6% and 8% sucrose concentrations was shorter than that of those treated with the 4% sucrose concentration. To prevent the proliferation of microorganisms caused by sucrose, we employed a combination of sucrose and bactericides. The vase solution containing 4% sucrose + 200 mg/L 8-HQS had a better preservation effect than either 4% sucrose or 200 mg/L 8-HQS alone. Inorganic salts can enhance the osmotic potential of the vase solution, thereby maintaining the water balance of cut flowers. The vase life and postharvest qualities of Dianthus 'Carnation' held in the vase solution containing inorganic salts were superior to those of the control[53]. In our study, 100 mg/L Al2(SO4)3 demonstrated the optimal preservative effect. Organic acids can function as antioxidants, radical scavengers, and ethylene inhibitors[54]. We found that 100 mg/L of citric acid was the most suitable concentration for 'Hangshao', as higher concentrations shortened the vase life of the cut flowers. Endogenous hormones affect the vase life of cut flowers[55]. Our previous research revealed that the transcription factor PlZFP mediates the interactions of ABA with GA and ethylene during the senescence of herbaceous peony flowers[24]. Silencing PlZFP by VIGS can simultaneously alter the content of GA, ABA, and ethylene in 'Hangshao'. In this study, we optimized the VIGS technology to silence PlZFP in 'Hangshao' cut flowers. Compared with traditional chemical reagents, the molecular biology technology VIGS offers advantages such as simplicity in operation, lower cost, safety, environmental friendliness, and effective preservation. This study integrates the optimization of VIGS and the use of vase solutions, establishing a novel and effective postharvest preservation approach to extend the flower longevity of herbaceous peony.

-

In our study, according to the production trends of ethylene, herbaceous peony cultivars could be classified into three types: the climacteric type, the non climacteric type, and the increases during the later stage type. Herbaceous peony may have a dual senescence mechanism. In the climacteric type, ABA plays a role in triggering ethylene biosynthesis and induces the accumulation of soluble sugar and protein. Thus, the ethylene-ABA interaction may play a crucial role in the senescence of climacteric peonies. In the non climacteric and the increases during the later stage type, ethylene remained at a low level, and ABA-induced the accumulation of soluble sugar and protein. ABA may act as a decisive player in the senescence of these two types of herbaceous peonies. In addition, total phenolics were highly involved in antioxidant activity, while flavonoids partially participated. The activities of PPO, POD, SOD, and CAT, as well as membrane permeability are related to the degree of senescence but not to the type of cut herbaceous peony flowers. According to the above conclusion, we constructed a new postharvest preservation approach that combines the optimization of VIGS and the use of a vase solution. The new approach can extend the flower longevity of herbaceous peony to 1.3 times its original lifespan.

This study was funded by Shaanxi Key Research and Development Plan Project (Grant No. 2020ZDLNY01-04). We are grateful to Meiling Wang for kindly helping us finish our experiment.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: experiments design: Ji X, Zeng D, Zhang Y; experiments performing: Ji X, Li K; research conception: Ji X, Sun D, Niu L; data analysis: Ji X, Sun D; manuscripts writing: Ji X; manuscript commenting and approving: Zhang Y; project coordinating: Niu L. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Xiaotong Ji, Kangkang Li

- Supplementary Table S1 Effect of sugar on senescence of cut herbaceous peony flowers.

- Supplementary Table S2 Effect of organic acid on senescence of cut herbaceous peony flowers.

- Supplementary Table S3 Effect of inorganic salt on senescence of cut herbaceous peony flowers.

- Supplementary Table S4 Effect of bactericide on senescence of cut herbaceous peony flowers.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Phenotype of different cultivars of herbaceous peony during flower senescence.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Changes in content of gibberellins during herbaceous peony senescence. (a) Changes in GA1 content. (b) Changes in GA4 content. (c) Changes in GA7 content. Error bars show the SD of the means of three biological replicates.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Silencing efficiency of VIGS determined by qRT-PCR.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ji X, Li K, Sun D, Niu L, Zeng D, et al. 2025. Physiological and biochemical changes during flower senescence of herbaceous peony and a new postharvest approach for extending flower longevity. Ornamental Plant Research 5: e022 doi: 10.48130/opr-0025-0020

Physiological and biochemical changes during flower senescence of herbaceous peony and a new postharvest approach for extending flower longevity

- Received: 08 December 2024

- Revised: 03 February 2025

- Accepted: 12 February 2025

- Published online: 04 June 2025

Abstract: The herbaceous peony is a significant cut-flower plant cultivated worldwide. However, the in-depth understanding of herbaceous peony flower senescence is scarce, and the short natural florescence substantially restricts its industrial development. In this study, we investigated the physiological and biochemical responses of 25 different cultivars of herbaceous peony during flower senescence and developed a new postharvest preservation approach to extend flower longevity. We found that herbaceous peony can be divided into three types based on the pattern of ethylene production: the climacteric type, the non climacteric type, and the type with a later-stage increase. In the climacteric type, abscisic acid (ABA) may play a role in triggering ethylene biosynthesis, while in the other two types, ABA had no direct correlation with ethylene biosynthesis. The soluble sugar and protein content were positively correlated with the ABA content. Moreover, total phenolics were highly involved in antioxidant activity, while flavonoids were partially involved. The activities of PPO, POD, SOD, CAT, the MDA content, and the membrane permeability were related to the degree of senescence. We found that silencing senescence-associated transcription factors with virus-induced gene silencing technology (VIGS) and using a vase solution can both extend herbaceous peony flower longevity. Therefore, we construct a new postharvest preservation approach that combines the optimization of VIGS and the use of the vase solution. The new approach can extend the flower longevity of herbaceous peony upto 1.3 times its original lifespan. Our results provide new insights into delaying herbaceous peony flower senescence.