-

Rosa hybrida (rose) is a globally important ornamental plant, renowned for its rich colored petals, which play an irreplaceable role in landscape beautification and economic value[1]. However, petal fading significantly affects the aesthetic and commercial quality of roses. Petal fading is closely associated with the dynamic changes in anthocyanin biosynthesis and degradation[2]. Recent advances in the study of floral color senescence mechanisms have revealed the critical role of the intricate regulatory network between hormonal signaling and pigment metabolism in maintaining floral color and delaying petal senescence[3,4].

Anthocyanins are the key pigments responsible for petal coloration. Their biosynthesis is primarily initiated through the phenylpropanoid pathway, involving a series of enzymatic steps catalyzed by key genes. These include early biosynthetic genes (EBGs) such as chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI), flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H), flavonoid 3'-hydroxylase (F3'H), as well as late biosynthetic genes (LBGs) such as dihydroflavonol-4-reductase (DFR), anthocyanidin synthase (ANS), and anthocyanin glycosyltransferase (UFGT)[5−7]. Among these, CHS serves as a critical node in the early steps of anthocyanin biosynthesis, catalyzing the reaction between p-coumaroyl-CoA and three molecules of malonyl-CoA to produce chalcone, which is the first committed step in the flavonoid and anthocyanin biosynthetic pathways[8,9]. Studies have shown that the expression of CHS is regulated not only by the MYB-bHLH-WD40 complex but also by hormonal signaling[10]. Hormones play a crucial role in petal senescence, with ethylene and abscisic acid (ABA) identified as primary positive regulators, while auxin uniquely delays petal color fading[11,12]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, exogenous indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) treatment significantly suppresses the expression of anthocyanin degradation-related genes, such as PER and POD, thereby delaying petal senescence[13,14]. These findings suggest that auxin delays petal senescence by inhibiting ethylene synthesis, stabilizing anthocyanins, and maintaining vibrant petal color.

It is well established that auxin plays a crucial role in plant cell elongation[15,16], root development[17,18], and fruit ripening[19−21] and is synthesized via both tryptophan-dependent and tryptophan-independent pathways. Studies have shown that the regulatory effects of auxin on anthocyanin biosynthesis exhibit species specificity. For instance, auxin treatment modulates anthocyanin accumulation in Sweet Cherry (Prunus avium L.)[22], apple (Malus domestica)[23], and grape (Vitis vinifera)[10,24]. In peach, auxin upregulates the expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes such as PpCHS, PpDFR, PpF3H, and PpUFGT[25]. These findings suggest that auxin's regulatory function is not only species-dependent but also influenced by interactions with other phytohormones, forming a complex network of synergistic effects[26].

Auxin signaling is mediated through the TIR1/AFB-Aux/IAA-ARF pathway, which regulates plant growth and development via auxin-responsive genes[27]. In recent years, the ARF (Auxin Response Factor) family, as key transcription factors in auxin signaling, has been found to play essential roles in plant development, stress responses, and secondary metabolism[16]. Within a specific concentration range, auxin influences the expression of transcription factors involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis. Furthermore, ARF proteins in the auxin signaling pathway interact with anthocyanin-related transcription factors to modulate the expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes[23,28]. Studies have demonstrated that certain ARFs directly regulate anthocyanin accumulation by binding to the promoters of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes. For example, in grape, VvARF3 interacts with VvFHY3 to suppress its transcriptional activity, thereby antagonizing VvFHY3-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis[10]. In apple, MdARF13 interacts with MdMYB10 to repress the expression of the MdDFR promoter, leading to reduced anthocyanin accumulation. High auxin concentrations further enhance this inhibitory effect by promoting the degradation of MdIAA121 via the 26S proteasome pathway, thereby strengthening MdARF13-mediated suppression of anthocyanin biosynthesis[23]. This mechanism also explains the findings of Ji et al., who observed that anthocyanin accumulation in red-fleshed apple callus is inhibited by high concentrations of 2,4-D or NAA[29].

This study aims to elucidate the molecular mechanism by which RhARF8 regulates rose floral pigmentation through auxin-mediated pathways. Our findings will contribute to a deeper understanding of the hormonal regulation of floral coloration and provide a theoretical foundation for the application of plant hormones in color modulation. Moreover, this research will offer a valuable genetic resource for molecular breeding programs targeting ornamental plants such as roses.

-

The cut roses (Rosa hybrida 'Pink Floyd') used in the experiment were harvested at stage 3 from the greenhouse of the Flower Research Institute, Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Yunnan, China[30]. The outermost two whorls of rose petals were excised into 15 mm discs using a hole puncher. After being rinsed with deionized water, the petal discs were placed on 1% agar (v/v) medium supplemented with different concentrations of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA, 0, 10, 50, 100 μM). The incubation conditions were set at 25 °C with a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod and 60%–70% relative humidity. Each Petri dish contained 50 petal discs for subsequent experimental treatments, and petal discs phenotype was recorded before treatment in Supplementary Fig. S1.

VIGS and overexpression assays

-

The virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) experiment was conducted as previously described[31]. Specific fragments (250–350 bp) of RhARF1 and RhARF8 were amplified via PCR, cloned into the pTRV2 vector, and subsequently introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. The transformed bacteria were cultured in LB medium supplemented with kanamycin (25 μg/mL) and rifampicin (50 μg/mL) at 28 °C on a rotary shaker (200 rpm) for 18 h. After harvesting, the cells were resuspended in infiltration buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 200 mM acetosyringone, and 10 mM MES, pH 5.6) to a final OD600 of approximately 1.0. The TRV1 and TRV2 bacterial suspensions were mixed at an appropriate ratio and used for vacuum infiltration of rose petal discs[32].

The coding sequence (CDS) of RhARF8 was amplified via PCR and cloned into the pSuper1300 overexpression vector. The recombinant pSuper1300 vector and the empty vector were transformed into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101, cultured under identical conditions, and resuspended in infiltration buffer to a final OD600 of approximately 1.0. The bacterial suspensions were incubated on a shaker (28 °C, 200 rpm) for 1 h and then used for vacuum infiltration of rose petal discs. All treated petal discs were analyzed 3 d after VIGS or overexpression treatment for subsequent experimental procedures.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

-

Total RNA was extracted from rose petals using the method described by Wu et al.[33]. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the TransScript One-Step gDNA Removal and HiScript III RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) kit (Vazyme) following the manufacturer's protocol. RT-qPCR was performed on the Step One Plus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using 2 × M5 Hiper SYBR Premix EsTaq (with Tli RNase) (Mei5bio) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RhUBI2 was used as the reference gene for normalization. The primer sequences used for amplification are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Subcellular localization

-

The full-length coding sequence (CDS) of RhARF8 was fused to GFP and inserted into the pSuper vector (pSuper::RhARF8). The nuclear localization marker NF-YA4-mCherry was co-transformed as a reference. The recombinant vector pSuper::RhARF8 and the NF-YA4-mCherry construct were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 and co-infiltrated into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. After 3 d, the infiltrated leaves were observed under a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Olympus, FV3000, Japan) at 488 nm and 561 nm excitation for GFP and mCherry signals, respectively.

Anthocyanin measurement

-

Anthocyanin content was measured following the method described by Khazaei et al.[34], with slight modifications. Briefly, 2 mL of extraction buffer [1% (v/v) HCl/methanol] was mixed with 0.2 g of fresh tissue (FW). The mixture was incubated at 4 °C for 24 h in the dark to prevent light-induced degradation. After incubation, the sample was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 1 min at 4 °C. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured using a spectrophotometer (Techcomp UV-2600, Kunming, China) at 530 nm (A530) and 657 nm (A657). The relative anthocyanin content was calculated using the following formula: ((A530 – A657) × Dilution factor/mg FW tissue) × 1,000.

Phylogenetic analysis

-

Amino acid sequences were aligned using DNAMAN software to ensure accurate sequence comparisons. Phylogenetic analyses were performed with MEGA-X software. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the maximum likelihood (ML) method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates to assess the reliability of the branching patterns. The Jones‒Taylor‒Thornton (JTT) substitution model was selected for the analysis based on its suitability for protein sequence evolution. Tree visualization and annotation were performed using iTOL (Interactive Tree Of Life) to enhance interpretability.

Y1H assay

-

Promoter fragments of RhCHSa (918 bp), RhCHSc (532 bp), RhCHI (826 bp), RhF3H (615 bp), RhF3'H (557 bp), RhDFR (522 bp), RhANS (2,128 bp), RhGT1 (2,053 bp), and RhUFGT (1,986 bp) were cloned and inserted into the pLacZ vector to generate corresponding promoter-lacZ fusion constructs (e.g., pRhCHSa-LacZ, pRhCHSc-LacZ). The coding sequences (CDSs) of RhARF1 and RhARF8 were cloned into the pJG4-5 vector to create pJG-RhARF1 and pJG-RhARF8, respectively. The recombinant pJG4-5 vectors and pLacZ plasmids containing different promoter fragments were cotransformed into the Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain EGY48 and cultured on synthetic dextrose (SD) media lacking tryptophan (-Trp) and uracil (-Ura). Transformants were subsequently transferred to SD media supplemented with 80 μg/mL X-gal for colorimetric analysis to detect interactions. Primer sequences used in the Y1H assays are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

-

To evaluate the effect of transcription factor RhARF8 on RhCHSa/c promoter activities, a dual-luciferase reporter assay was performed. The firefly luciferase (LUC) gene was fused to the minimal CaMV 35S promoter and a 5 × GAL4 binding site, while the Renilla luciferase (REN) gene, driven by the full 35S promoter, served as a reference. The open reading frame (ORF) of RhARF8 was inserted into the pGreenII62-SK vector, and the promoters of RhCHSa (918 bp) and RhCHSc (532 bp) were cloned into the pGreenII0800-LUC dual-reporter vector[35]. Empty vectors were used as controls. Effector and reporter constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 carrying the pSoup plasmid. Equal volumes of Agrobacterium cultures were mixed and co-infiltrated into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. After 3 d, infiltrated leaves were imaged using a CCD camera to capture luminescence signals.

Relative luciferase activity (RLA) was quantified using ImageJ software by analyzing luminescence intensity in selected regions of interest (ROIs). Data from three biological replicates were averaged, and standard deviations were calculated to present the results. Primer sequences used for the constructs are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

ChIP quantitative PCR (ChIP‒qPCR)

-

ChIP‒qPCR was performed as previously described[36]. Rose petals transiently overexpressing GFP-tagged proteins were crosslinked with 1% (w/v) formaldehyde, and the reaction was quenched by adding glycine to a final concentration of 0.125 M. Crosslinked chromatin was sonicated to generate DNA fragments ranging from 300 to 750 bp. GFP-tagged protein–DNA complexes were immunoprecipitated using GFP-Trap® A magnetic beads (1:1,000 dilution; Chromotek, gtma-20) by overnight incubation at 4 °C. After washing the beads thoroughly, the DNA was eluted and the crosslinks were reversed by incubation at 65 °C for 6 h. The DNA was subsequently purified using a PCR purification kit.

The purified DNA was analyzed by qPCR using specific primers targeting different genomic regions of interest. All reactions were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. Primer sequences used for qPCR are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Statistical analysis

-

All experiments were conducted with at least three biological replicates to ensure data reliability. For comparisons between two groups, statistical significance was assessed using Student's t-test. For comparisons among multiple groups, Duncan's multiple range test was applied. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise specified.

-

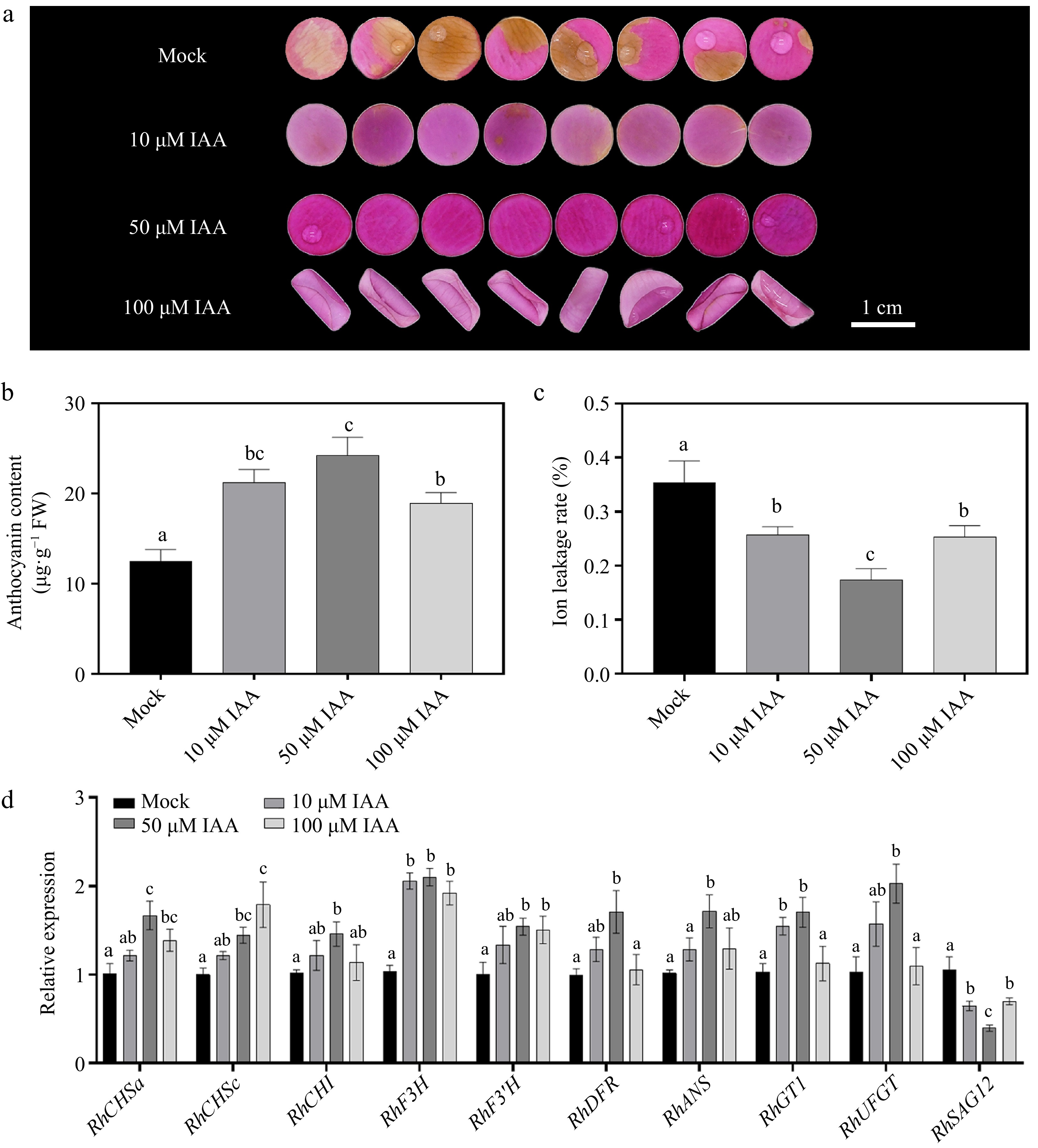

As widely reported, plant hormones such as abscisic acid (ABA) and cytokinins (CK) have been shown to play crucial roles in regulating floral pigmentation[37,38]. However, research on the role of auxin in floral pigmentation remains relatively limited, particularly in rose, where its function has yet to be fully explored. To better understand the impact of auxin on rose petals, we conducted IAA treatment on rose petals. When compared to Mock, 50 μM IAA exhibited the most pronounced effect in repressing color fading after 12 d of treatment, 10 μM IAA showed a slight effect, but 100 μM IAA caused petal rolling (Fig. 1a). We also observed that 50 μM IAA resulted in a highest anthocyanin content and smallest ion leakage rate than other treatments (Fig. 1b, c), further indicating that IAA significantly inhibiting the color fading in rose petals. To explore the effect of IAA on rose petals, we monitored the genes related to anthocyanin biosynthesis and metabolism[39]. As shown in Fig. 1d, the expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes (e.g., RhCHSa/c, RhCHI, RhDFR, RhANS, and RhF3H) was significantly upregulated under 50 μM IAA treatment. Besides, during petal senescence and floral color fading, the expression levels of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes decline significantly, leading to a reduction in anthocyanin content, which is one of the primary causes of petal discoloration[40−42].

Figure 1.

Effects of different concentrations of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) on petal phenotype, anthocyanin accumulation, ion leakage rate, and gene expression 12 d after treatment. (a) Phenotypic changes of petals treated with 0 μM (Mock control), 10 μM, 50 μM, and 100 μM IAA. After 12 d of treatment, petal color fading was significantly delayed with increasing IAA concentration, with 50 μM and 100 μM treatments exhibiting darker pigmentation. (b) Comparison of anthocyanin content under different IAA concentrations. (c) Changes in ion leakage rate under different IAA treatments. (d) Relative expression levels of the anthocyanin b iosynthesis-related genes (RhCHSa, RhCHSc, RhCHI, RhDFR, RhF3H, RhF3'H, RhANS, RhGT1, and RhUFGT) and senescence marker gene RhSAG12 under different IAA concentrations. Data are presented as means ± SE. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

To investigate the relationship between floral pigmentation and senescence in this study, SAG12, the most widely used senescence-associated marker gene[43], was selected for expression analysis. The results showed that IAA treatment significantly suppressed the expression of SAG12, with a progressive decrease observed as IAA concentration increased. Notably, under 50 μM IAA treatment, SAG12 expression reached its lowest level (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1d).

In summary, we demonstrated that auxin indeed enhanced the maintaining of petal color by elevating the anthocyanin content in rose petals.

Auxin responding factor RhARF8 directly binds to the RhCHS promoter

-

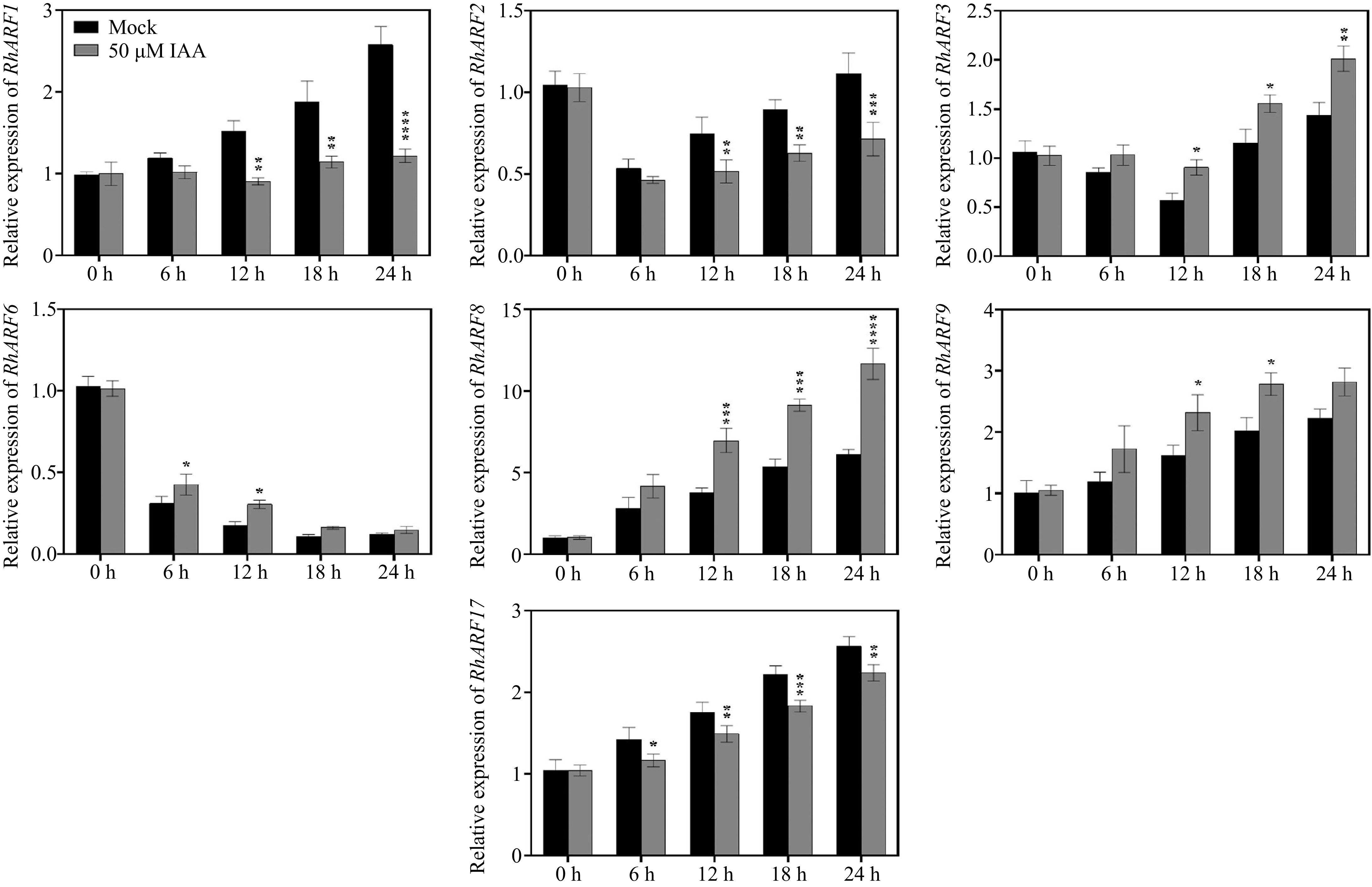

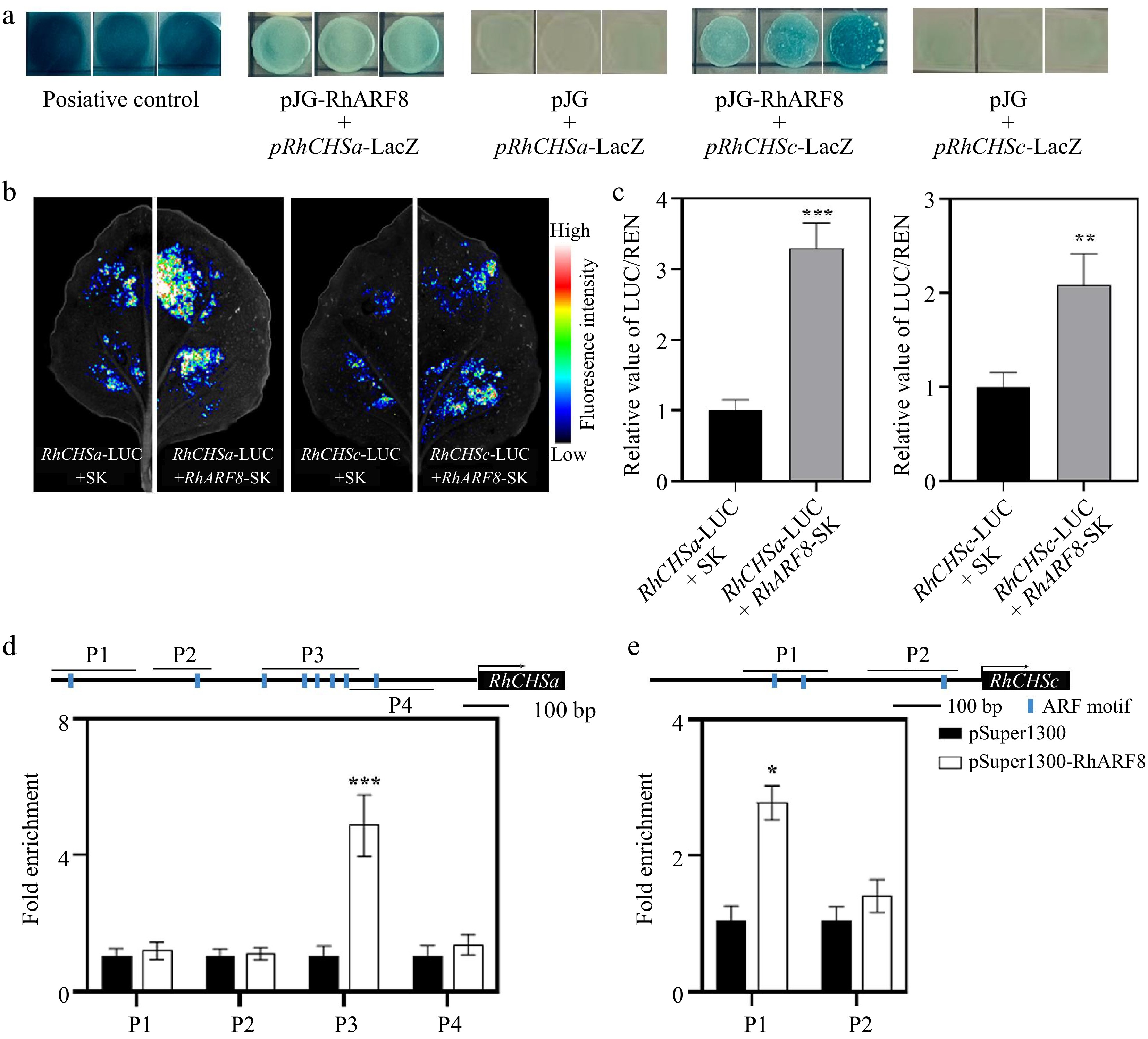

The functions of auxin usually depend on ARFs[44,45]. To better explore the underlying mechanism involved in auxin, we screened the presented high expression levels of seven ARFs in rose petals according to previous transcriptome data[46]. The RT-qPCR revealed that the expression levels of ARF3/6/8/9 was induced by 50 μM IAA treatment after 12 h, while the expression levels of ARF1/2/17 were repressed (Fig. 2). Thus, we cloned the CDS of the above ARF and conducted Y1H to identify the interaction between ARF proteins and anthocyanin-related genes. Notably, RhARF1 and RhARF8 could interact with the RhCHSa/c promoter in yeast, but other ARFs not (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Fig. S2a). Meanwhile, the dual luciferase assay results suggested that RhARF8, but not RhARF1, could activate the RhCHSa/c promoter activity (Fig. 3b, c; Supplementary Fig. S2b). In addition, the ChIP‒qPCR further demonstrated that RhARF8 could bind to the P3 fragment of the RhCHSa promoter and P1 fragment of the RhCHSc promoter (Fig. 3d, e).

Figure 2.

Temporal expression patterns of ARF genes in petals under different IAA treatments. Petals were treated with 50 μM IAA or Mock control, and sampled at 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h to determine the relative expression levels of ARF genes. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared to the Mock control (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001). Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 3).

Figure 3.

RhARF8 directly binds to the promoters of RhCHSa/c and activates their expression in rose petals. (a) Yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assay demonstrating the binding of RhARF8 to the promoters of RhCHSa and RhCHSc. Positive controls (pJG + pRhCHSa-LacZ and pJG + pRhCHSc-LacZ) show LacZ activity, while RhARF8 exhibit promoter-binding specificity. (b) Fluorescence imaging showing luciferase activity driven by the RhCHSa and RhCHSc promoters in the presence or absence of RhARF8 in transient assays. The fluorescence intensity was markedly increased in the presence of RhARF8. (c) Quantification of luciferase activity. RhARF8 significantly activated the RhCHSa and RhCHSc promoters compared to the control (*** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01). (d) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR analysis showing RhARF8 exhibited significant enrichment at the P3 region of RhCHSa (*** p < 0.001). (e) RhARF8 exhibited significant enrichment at the P1 regions of RhCHSc (* p < 0.05). Values represent means ± SD (n = 3).

RhARF8 contributes to anthocyanin biosynthesis and color fading by activating RhCHSa/c promoter activity

-

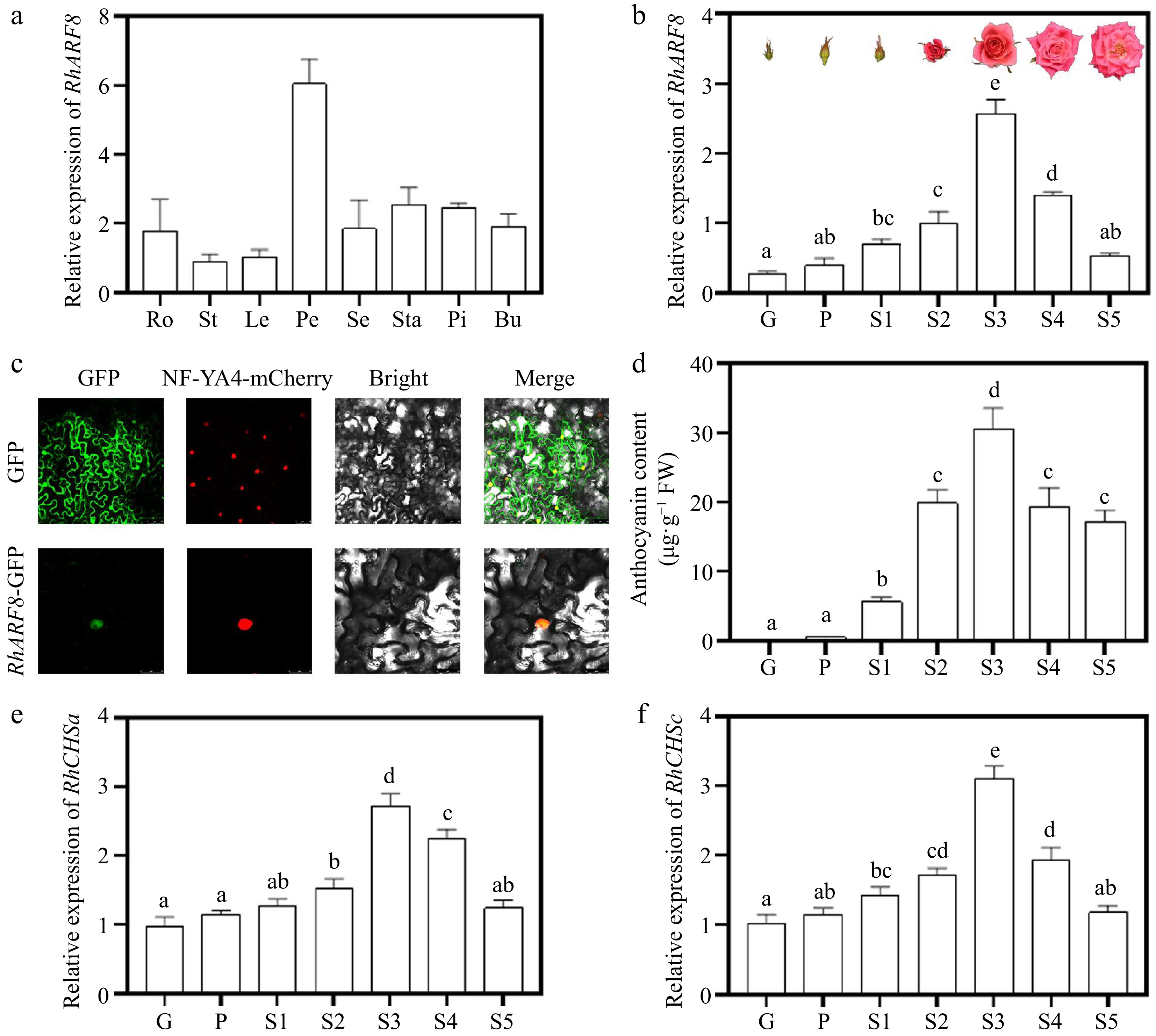

To better understand the characteristics of RhARF8, tissue-specific analysis showed that RhARF8 expression was highest in petals (Fig. 4a) and exhibited an increasing trend from green to stage 3 of flower opening (Fig. 4b), mimicking changes of anthocyanin content during flower opening (Fig. 4c), implying that RhARF8 may be closely related to flower color and anthocyanin content. Subcellular localization revealed that the RhARF8-GFP fusion protein was localized in the nucleus, overlapping with the nuclear marker NF-YA4-mCherry (Fig. 4d). Meanwhile, RT-qPCR further revealed that RhCHSa/c expression levels were positively related to anthocyanin accumulation and RhARF8 during the flower opening (Fig. 4e, f).

Figure 4.

Expression patterns and subcellular localization of RhARF8. (a) Relative expression levels of RhARF8 in different tissues (Ro: root; St: stem; Le: leaf; Pe: petal; Se: sepal; Sta: stamen; Pi: pistil; Bu: bud). (b) Relative expression levels of RhARF8 during flower opening stages (G, P, S1−S5) and phenotypic images of flower opening stages. (c) Subcellular localization of RhARF8 showing nuclear localization. (d) Anthocyanin content during different flower opening stages. (e) Relative expression levels of RhCHSa during flower opening stages. (f) Relative expression levels of RhCHSc during flower opening stages. Data are presented as means ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences between groups (p < 0.05).

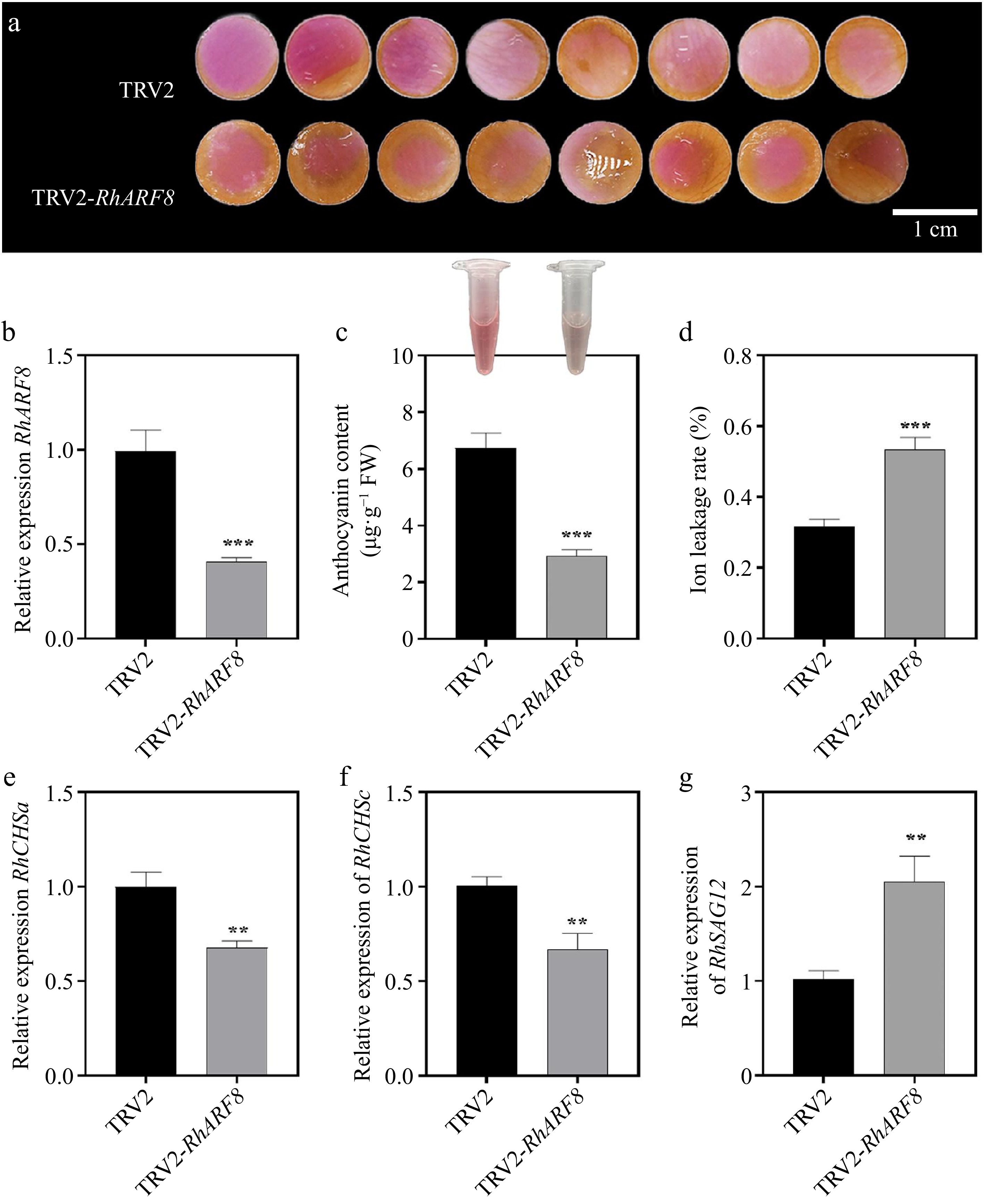

To validate the role of RhARF8 involved in rose color fading, we conducted the virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) assay and found that RhARF8 knockdown resulted in an accelerated fading process with lower anthocyanin level and higher ion leakage rate compared to the TRV control (Fig. 5a−d), which was opposite to the results of IAA treatment. Meanwhile, we observed that the silencing of RhARF8 led to a significant decrease of RhCHSa/c expression (Fig. 5e, f). Moreover, the expression of RhSAG12 was lower in RhARF8-silenced petals than TRV control (Fig. 5g). In addition, there was no significant difference in color fading between RhARF1 silencing and TRV (Supplementary Fig. S2c). Taken together, we revealed that auxin-mediated the RhARF8-RhCHSa/c module contributes to color fading in rose petals by regulating the anthocyanin biosynthesis.

Figure 5.

Effects of RhARF8 silencing on anthocyanin metabolism and rose petal pigmentation. (a) Petal color changes in TRV2 control and TRV2-RhARF8-treated groups. (b) Relative expression levels of RhARF8. (c) Anthocyanin content. (d) Ion leakage rate. (e) Expression levels of the key anthocyanin biosynthetic gene RhCHSa. (f) Expression levels of the key anthocyanin biosynthetic gene RhCHSc. (g) Expression levels of the senescence marker gene RhSAG12 ( *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05). Data are presented as means ± SE.

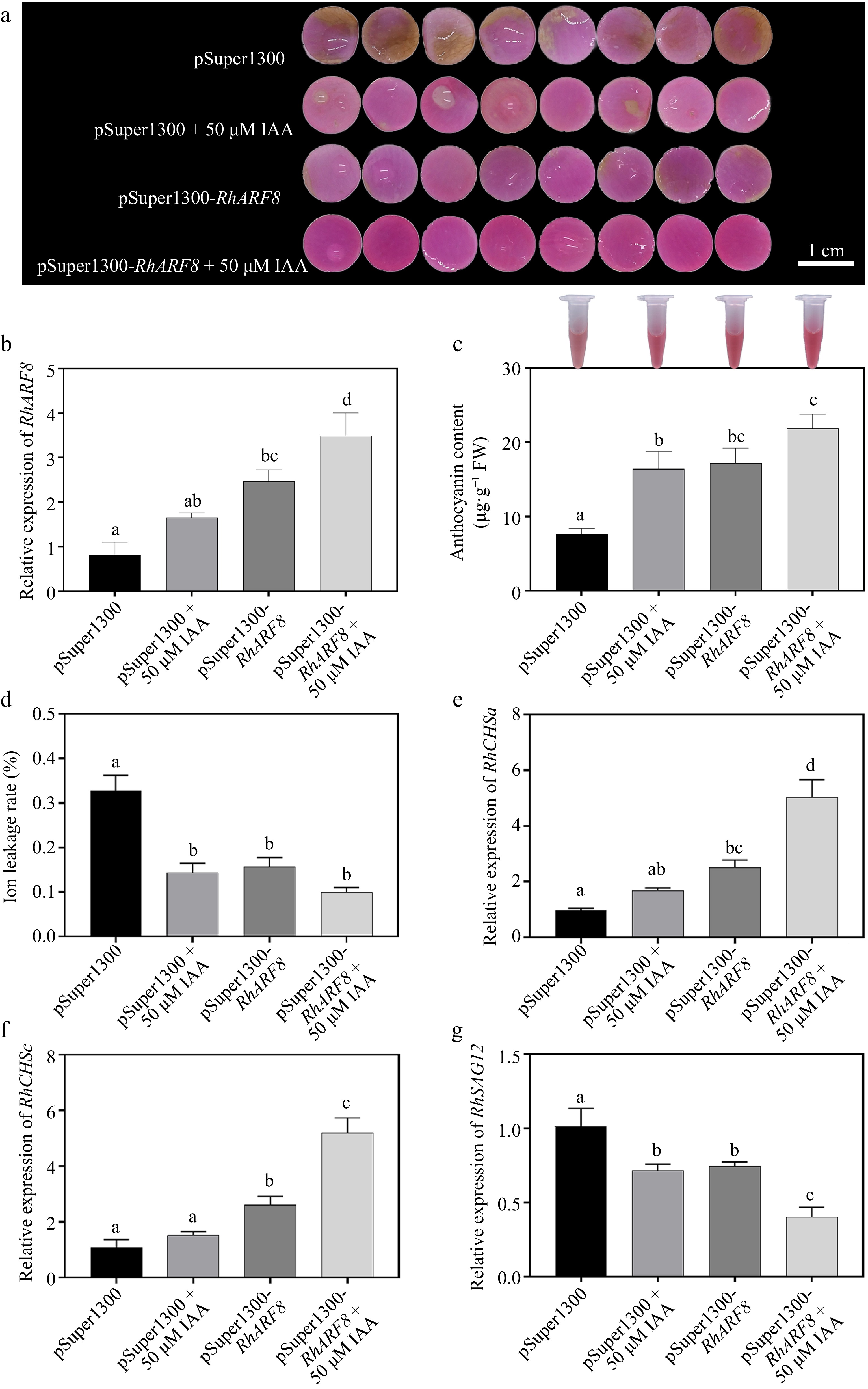

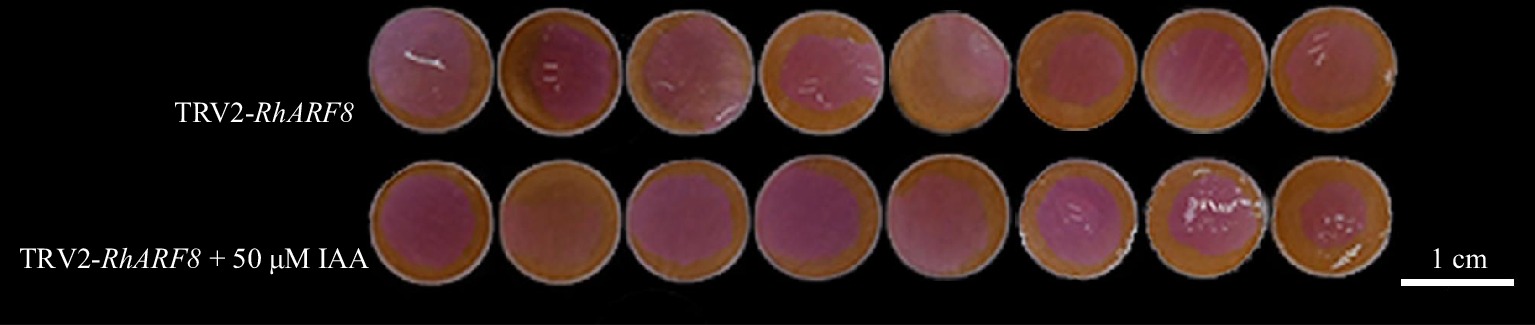

To further investigate the synergistic effects of RhARF8 and IAA signaling in anthocyanin metabolism regulation, we designed four treatments: pSuper1300 empty vector, IAA treatment (pSuper1300 + 50 μM IAA), RhARF8 overexpression (pSuper1300-RhARF8), and RhARF8 overexpression combined with IAA treatment (pSuper1300-RhARF8 + 50 μM IAA). The results showed that RhARF8 significantly delayed color fading in rose petals in comparison to pSuper1300 control (Fig. 6a). Meanwhile, RhARF8 overexpression combined with IAA displayed more resistance against color fading than RhARF8 overexpression or IAA treatment only, accompanying with higher RhARF8 expression levels and anthocyanin content, lower relative ion leakage rate (Fig. 6a−d). In addition, RT-qPCR further showed that the RhARF8 overexpression induced increasing expression of RhCHSa/c and decreasing expression of RhSAG12 (Fig. 6e−g). Besides, we further conducted IAA treatment on TRV2-RhARF8 and found that there was no significant difference between IAA treatment on TRV2-RhARF8 and TRV2-RhARF8 control (Fig. 7). Taken together, our results demonstrated that auxin modulated the anthocyanin biosynthesis and color fading in rose petals by depending on RhARF8.

Figure 6.

Synergistic effects of IAA and RhARF8 on anthocyanin metabolism and related physiological processes in roses. (a) Petal color changes under different treatments: pSuper1300 empty vector, IAA treatment (pSuper1300 + 50 μM IAA), RhARF8 overexpression (pSuper1300-RhARF8), and RhARF8 overexpression combined with IAA treatment(pSuper1300-RhARF8 + 50 μM IAA). (b) Relative expression levels of RhARF8. (c) Anthocyanin content. (d) Ion leakage rate. (e) Expression levels of key anthocyanin biosynthetic genes RhCHSa. (f) Expression levels of key anthocyanin biosynthetic genes RhCHSc. (g) Expression levels of the senescence marker gene RhSAG12. Data are presented as means ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences between groups (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Synergistic effects of IAA and RhARF8 silencing in roses. Petal color changes under different treatments: RhARF8 silencing (TRV2-RhARF8), and RhARF8 silencing combined with IAA treatment (TRV2-RhARF8 + 50 μM IAA).

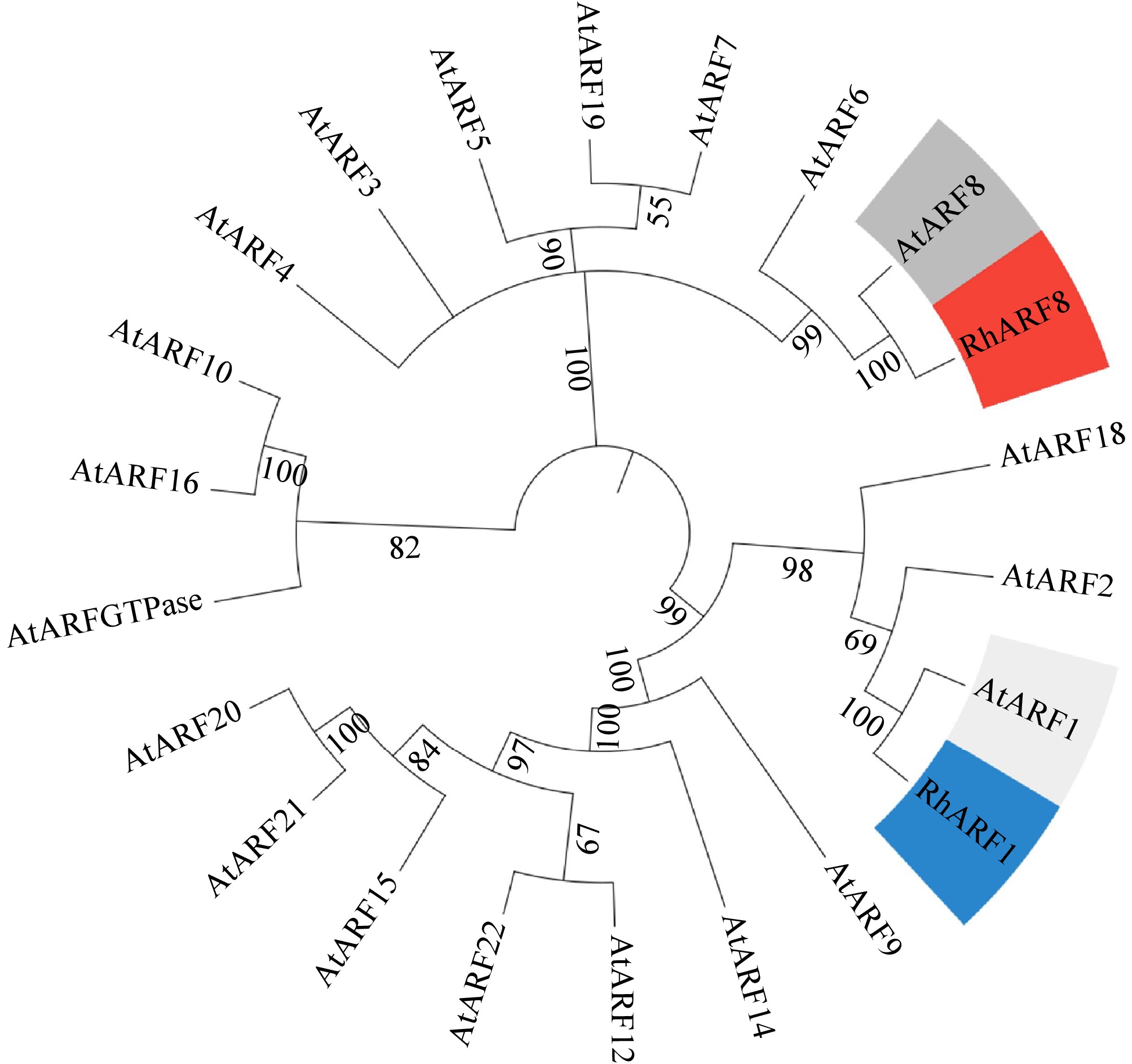

Phylogenetic analysis further underscored the functional specificity of RhARF8. A phylogenetic tree based on full-length amino acid sequences showed that RhARF8 clustered closely with AtARF8 from Arabidopsis thaliana within the same clade, suggesting a conserved role in auxin signaling and specific biological processes. In contrast, RhARF1 is grouped into a separate clade with AtARF1 (Fig. 8), implying its involvement in distinct biological functions, such as basal cellular processes or stress responses. This evolutionary divergence highlights the pivotal role of RhARF8 in anthocyanin metabolism and petal pigmentation, while RhARF1 likely plays a relatively minor role in these processes.

Figure 8.

Phylogenetic analysis of RhARF8 and RhARF1. Phylogenetic tree based on full-length amino acid sequences showing that RhARF8 and RhARF1 cluster into distinct clades with AtARF8 and AtARF1 from Arabidopsis thaliana, highlighting their functional specificity and evolutionary divergence.

In summary, the spatiotemporal expression and nuclear localization of RhARF8, its strong correlation with anthocyanin accumulation, and its evolutionary specificity collectively establish it as a pivotal regulator of anthocyanin metabolism in rose petals.

-

The SoNAC72-SoMYB44/SobHLH130 module directly binds to the promoter of SoUFGT1 in lilac (Syringa oblata), where SoMYB44 upregulates the expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes, thereby regulating anthocyanin synthesis and floral color fading[47]. In rose (Rosa chinensis), RcMYB1 positively regulates the expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes and anthocyanin accumulation[39]. In contrast, ARFs in apple (Malus domestica) and grape (Vitis vinifera) negatively regulate the expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes, leading to reduced anthocyanin content[10,23]. These findings align with the results of this study, which demonstrate that RhARF8 positively regulates anthocyanin biosynthetic gene expression, and influences petal color retention. In red-fleshed apple callus, anthocyanin accumulation is inhibited by high concentrations of α-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA)[29]. Conversely, in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings, exogenous indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) treatment upregulates the expression of structural genes (e.g., CHS, CHI, and F3′H) and regulatory genes (e.g., TTG1, PAP1, and MYB12) involved in the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway[28], suggesting that auxin promotes anthocyanin biosynthesis within a specific concentration range. In this study, treatment with 50 μM IAA was more effective than other concentrations in delaying petal fading in rose.

Our results indicate that RhARF8 significantly upregulates the expression of key genes in the anthocyanin metabolic pathway, including RhCHSa, RhCHSc, RhDFR, and RhANS (Supplementary Fig. S3). Promoter-binding assays further confirmed that RhARF8 directly binds to the promoter regions of these genes and enhances their promoter activities (Fig. 3). This finding is consistent with previous studies on Nicotiana tabacum, where NtARF8 was shown to regulate anthocyanin metabolism[48]. In tobacco, a functional ARF8 is essential for anthocyanin accumulation and floral pigmentation, as silencing ARF8 expression weakens ANS and DFR expression while reducing the role of TTG2 in anthocyanin biosynthesis[48]. Although ARFs have been implicated in anthocyanin metabolism regulation in various plant species[10,23], their specific function in rose, particularly in petal color fading, remains largely unexplored. Moreover, IAA treatment significantly elevated RhARF8 expression levels (Fig. 2), underscoring the critical role of IAA signaling in anthocyanin metabolism. This result aligns with previous findings demonstrating that IAA promotes secondary metabolic pathways by enhancing ARF factor activity[10,22,23].

For the first time, this study establishes the crucial role of RhARF8 in delaying petal senescence and preventing color fading. IAA treatment and RhARF8 overexpression significantly reduced petal ion leakage (Fig. 6), enhanced membrane stability, and downregulated the expression of the senescence-associated gene SAG12. These results suggest that IAA signaling, through RhARF8, effectively suppresses cellular senescence. Additionally, IAA signaling mitigates reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation and enhances antioxidant enzyme activity, further delaying petal senescence[49−51]. Auxin also inhibits petal fading and senescence-induced abscission by regulating sucrose transport. The interplay between IAA signaling and other phytohormones, such as ethylene and abscisic acid (ABA), plays a pivotal role in senescence regulation[11,12]. This study systematically elucidates the dynamic role of IAA and RhARF8 in maintaining petal integrity and delaying senescence, offering novel insights into hormonal signaling networks.

Comparative analysis revealed significant functional divergence between RhARF8 and RhARF1 in anthocyanin metabolism and petal senescence regulation (Supplementary Fig. S2). Although RhARF1 can bind to anthocyanin biosynthetic gene promoters, its transcriptional activation capacity is limited, and its silencing does not significantly affect petal color or anthocyanin content. In contrast, RhARF8 exhibits strong transcriptional activation ability, and its silencing markedly reduces petal anthocyanin content and color stability. This functional divergence is further supported by phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 8), suggesting that RhARF8 has undergone evolutionary specialization to become a key factor in the IAA signaling regulatory network.

The findings of this study provide valuable insights for improving ornamental plant coloration and extending floral longevity. Exogenous IAA treatment or genetic engineering strategies to enhance RhARF8 expression could effectively increase anthocyanin content, delay petal senescence, and improve floral color stability. Future studies should further explore the dynamic regulation of RhARF8 by varying IAA concentrations and investigate its interactions with other hormonal signals, such as ethylene and ABA, to optimize breeding strategies.

-

In summary, our study identifies an auxin signaling factor, RhARF8, that acts as a key regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis in roses petals via regulating the anthocyanin biosynthesis genes RhCHSa/c. These findings provide a theoretical basis for improving rose petal color traits through breeding or genetic engineering.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32202530), Yunnan Province Agricultural Joint Project (Grant No. 202401BD070001-016/100), Talent Introduction and Training Project of Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Grant No. 2024RCYP-09), and Fundamental Research Project (Grant No. 202401CF070046), Xingdian Talent support program (2023-0457/2019-135) and Yunnan Technology Innovation Center of Flower Technique. We sincerely thank Professor Guoren He from the college of Life Sciences, Shanghai Normal University for his support. We also appreciate his generosity in providing the vectors containing promoters of genes related to anthocyanin biosynthesis.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jing W, Tang K; data collection: Ma X, Li D, Cai J, Wang D, Yang S, Li Q; Zhang Q, Peng R; analysis and interpretation of results: Ma X, Qiu X, Tang K, Wang D, Yan H, Jian H, Wang Q, Wang L; draft manuscript preparation: Ma X, Jing W. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 List of primers used in this study.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Phenotype of Rose Petals Before Treatment in the Petal Disc Assay.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Effects of RhARF1 silencing on anthocyanin metabolism and rose petal pi gmentation.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Effects of RhARF8 overexpression and IAA co-treatment on the relative expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes in rose petals.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ma X, Li D, Cai J, Yang S, Wang D, et al. 2025. Auxin response factor, RhARF8 contributes to rose flower color fading via regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis by directly activating RhCHSa/c promoter activity. Ornamental Plant Research 5: e021 doi: 10.48130/opr-0025-0019

Auxin response factor, RhARF8 contributes to rose flower color fading via regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis by directly activating RhCHSa/c promoter activity

- Received: 07 March 2025

- Revised: 03 April 2025

- Accepted: 07 April 2025

- Published online: 16 May 2025

Abstract: Petal color is one of the most important agricultural traits in rose plants. However, the relationship between petal coloration and hormones remain largely unknown. Our research revealed that auxin (IAA) is essential for anthocyanin biosynthesis and the prevention of color fading in rose petals. Meanwhile, RhARF1/8 expression levels were significantly induced by IAA treatment. Yeast one-hybrid (Y1H), dual-luciferase assays, and chromatin immunoprecipitation of quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) demonstrated that RhARF8 could bind to promoters of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes RhCHSa/c (specifically the P3 fragment of the RhCHSa promoter and the P1 fragment of the RhCHSc promoter) and activates their promoter activities, whereas RhARF1 could not. In addition, silencing or overexpression of RhARF8 showed that IAA prolonged petal color retention and delayed petal senescence by mediating the RhARF8 expression. In conclusion, our study identifies an auxin signaling factor, RhARF8, which acts as a key regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis in rose petals via regulating the anthocyanin biosynthesis genes RhCHSa/c. These findings provide a theoretical basis for improving rose petal color traits through breeding or genetic engineering.

-

Key words:

- Rose petal /

- Anthocyanin /

- Auxin /

- RhARF8 /

- RhCHSa/c