-

The genus Ocimum, a member of the Lamiaceae family, comprises approximately 30 species, predominantly native to tropical and subtropical regions, though some are cultivated in temperate zones[1,2]. Characterized by their annual herbaceous nature, these plants produce a multitude of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), including species like O. americanum, O. basilicum, O. tenuiflorum, and others[3]. Their VOCs are widely recognized and utilized across various applications, such as culinary, medicinal, and aromatic applications[3,4]. The leaves, whether fresh or dried, impart a distinctive flavor and aroma to a range of culinary applications, from beverages and liqueurs to vinegars, teas, and cheese[5]. Pharmacological studies have demonstrated the antimicrobial and free radical scavenging properties of basil VOCs, with significant variation among varieties and plant parts[6]. Moreover, basil's activity spectrum encompasses a broad range of effects, including analgesic, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, hypoglycemic, hepatoprotective, and numerous other pharmacological activities[7]. Hence, basil is cultivated worldwide for its fragrant properties and economic value. Despite its rich history of breeding and cultivation, the mechanism of essential oil formation remains elusive, and large-scale synthesis poses a challenge.

The herb O. basilicum var. pilosum, as a variety of O. basilicum, is favored in horticulture for its ornamental and aromatic attributes[8]. This plant flourishes in subtropical climates and has a wide distribution across several Chinese provinces, such as Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangxi, Guangdong, and Hainan[9]. Historically, the aerial parts have been noted for their diverse pharmacological properties, including treatments for the common cold and pyrosis, and possessing sedative and detoxifying effects[8]. The VOCs, extracted from leaves, stems, and inflorescences, are currently utilized in the food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries[8−11]. However, there is currently a scarcity of research on the active components of VOCs and their biosynthetic pathways in O. basilicum var. pilosum.

It is well known that plant VOCs are typically categorized into terpenes, fatty acid derivatives, amino acid derivatives, and phenyl/phenylpropanes[12]. Interestingly, basil essential oil can be classified into seven chemotypes based on their compositions: high-linalool, linalool-eugenol, methyl chavicol, methyl chavicol-linalool, methyl eugenol-linalool, methyl cinnamate-linalool, and bergamotene[13]. Prior gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis of sweet basil (O. basilicum) identified linalool, estragole, methyl cinnamate, bicyclosesquiphellandrene, eucalyptol, α-bergamotene, eugenol, γ-cadinene, and germacrene D as the main constituents of VOCs[14]. Moreover, 33 components of basil VOCs have been identified, with linalool being predominant[15]. Studies indicate that the composition and yield of VOCs are significantly influenced by environmental factors, including genetics, climate, cultivation practices, plant varieties, and harvest timing[14−16]. The tropical marine monsoon climate of Hainan Island is certain to exert an impact on the composition of basil VOCs, but no reports are currently available.

Previous de novo transcriptome studies identified 69,117 transcripts in O. sanctum and 130,043 in O. basilicum, revealing several CYP450 and transcription factors (TFs) potentially involved in secondary metabolism[17]. Additionally, 81 terpene synthases (TPS) genes in O. sanctum were classified into six subfamilies: TPS-a, -b, -c, -e, -f, and -g[18]. Transcriptomic analysis in O. basilicum revealed 111,007 transcripts, emphasizing the photoprotective role of anthocyanins[19]. Transcriptome studies of O. basilicum var. pilosum primarily focus on its metabolic response to heat stress[8]. Eugenol-O-methyltransferase transcription levels positively correlated with methyleugenol contents across developmental stages of O. tenuiflorum, possibly involving in the conversion of eugenol to methyleugenol[20]. A drought inducible phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene from O. basilicum was characterized for its role in converting L-phenylalanine to trans-cinnamic acid[21]. Importantly, the completion of the O. basilicum draft genome sequence has unveiled its complex genomic landscape and laid the groundwork for advanced molecular breeding[22]. Current basil research primarily focuses on ingredient analysis, pharmacological activity, and gene mining. However, there is still a paucity of in-depth research on the biosynthetic mechanisms of basil VOCs.

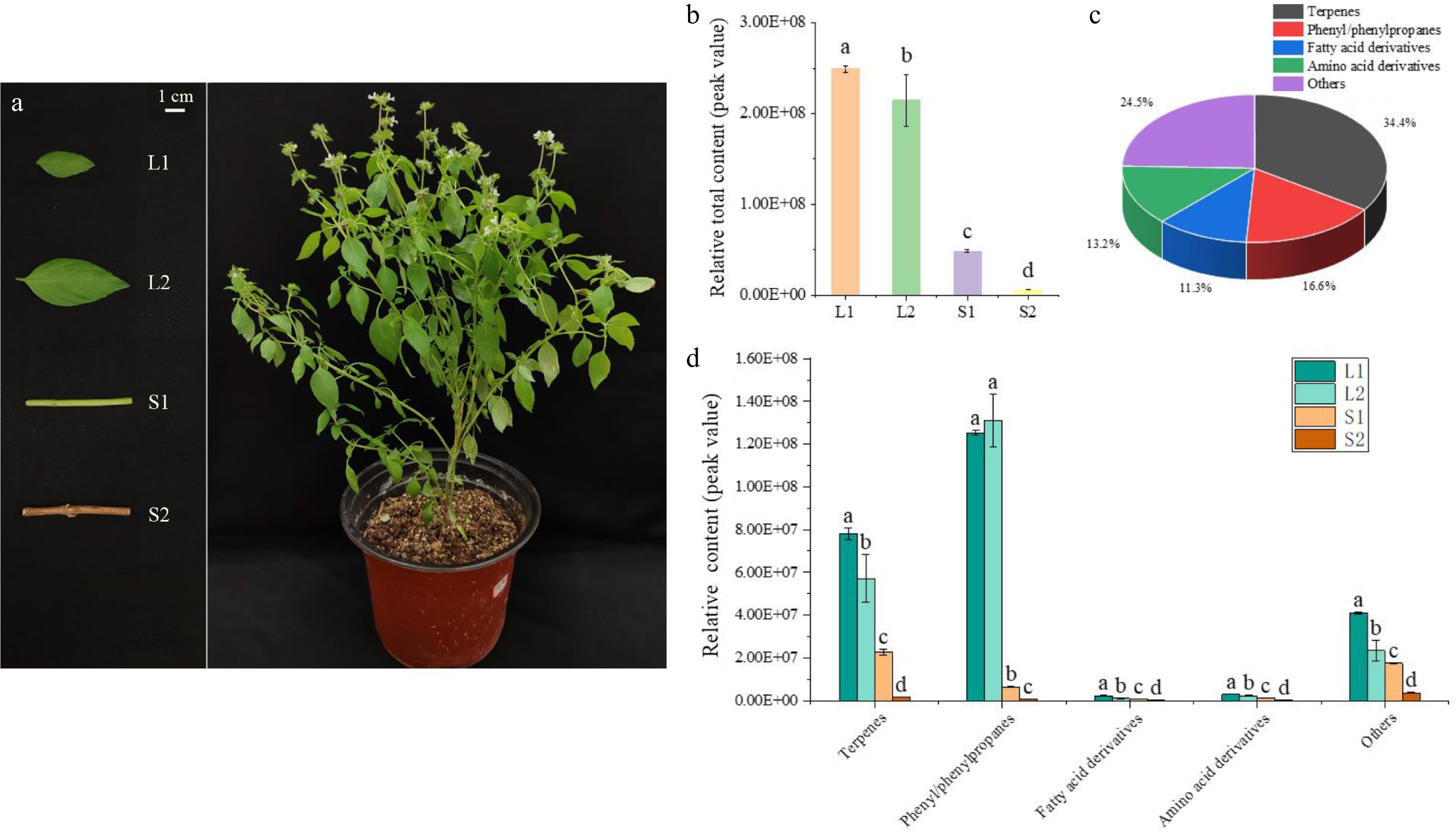

Based on previous investigations indicating that basil VOCs are primarily found in leaves and stems[6,7,16], we selected non-lignified stems (S1), lignified stems (S2), small foliage leaves (L1), and large foliage leaves (L2) as materials. Volatile metabolome analysis was employed to explore the qualitative and quantitative profiles of essential oils in O. basilicum var. pilosum from Hainan Island. Subsequently, transcriptomic sequencing was conducted using Illumina and PacBio technologies. By integrating the genomic data of O. basilicum[22], we excavated new genes and functional annotations and explored the expression of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Moreover, TFs, alternative splicing (AS), and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) were analyzed. Integrating essential oil profiles with gene expression data enabled a deeper understanding of the metabolic pathways and key regulatory factors of basil essential oil. These findings enhance our understanding of the biosynthetic mechanisms of basil essential oil and offer guidelines for improving quality.

-

Basil (O. basilicum var. pilosum) was cultivated at the Agricultural Science Base of Hainan University, located in Haikou City, Hainan Province, China (110°19'23" E, 20°3'25" N). Three-month-old basil plants exhibiting vigorous and uniform growth were selected for analysis. Samples including non-lignified stems (S1), lignified stems (S2), small foliage leaves (L1 at 1 week of age), and large foliage leaves (L2 at 4 weeks of age) were collected from five individual plants and pooled as a single biological replicate. The plant collection process was repeated three times to ensure replicability. The samples were washed with distilled water, dried, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for further analysis.

Determination and analysis of VOCs

-

The VOCs were isolated using headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME) with technical support from Biomarker Technologie (Beijing, China). A 20 mL headspace vial was loaded with 800 mg of sample powder, followed by the addition of 5 mL of boiling distilled water and 10 μL of 2-octanol as the internal standard. Following equilibration at 60 °C for 15 min, the sample was extracted using a 50/30 μm polydimethylsiloxane/divinylbenzene fiber for 30 min at 60 °C. The extract was injected into the GC injector and analyzed at 230 °C for 4 min. The extraction process was repeated three times for consistency.

The analysis utilized a Shimadzu GC2030-QP2020 NX GC-MS system equipped with an Agilent DB-5MS capillary column (30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm, J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA, USA). The specific GC-MS analytical conditions were as follows: in split mode with a 5:1 split ratio and a 3 mL/min front inlet septum purge flow rate. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a column flow rate of 1 mL/min. The oven temperature ramp was programmed to hold at 50 °C for 1 min, then increased at a rate of 8 °C/min to 310 °C, and held for an additional 11.5 min. The front injection temperature was set to 280 °C, and the transfer line temperature was also set to 280 °C. The ion source temperature was 200 °C, and the electron ionization energy was −70 eV. The mass range was set to cover m/z 50-500, and a 7.2-min solvent delay was implemented to ensure complete solvent evaporation before analysis.

Mass spectrometry data processing included peak extraction, baseline correction, deconvolution, peak integration, and peak alignment using ChromaTOF software (Version 4.3x, LECO)[23]. For the qualitative analysis of substances, the LECO-Fiehn Rtx5 database (BioMarkerm, Beijing, China) was employed.

Transcriptome sequencing

-

Total RNA from the plant was extracted using the RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA concentration and purity were determined using the NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE). RNA integrity was evaluated using the Agilent RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit on the Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Library preparation, Illumina sequencing, and Pacific Biosciences sequencing were performed as described in our previous report[24]. The completeness of the full-length transcriptome was evaluated using BUSCO[25]. Clean reads were aligned to the O. basilicum reference genome (CoGe database, genome ID 59011) using Hisat2 version 2.0.4[26]. Subsequently, StringTie version 2.2.1 was utilized to assemble the aligned reads, constructing and identifying known and novel transcripts based on Hisat2 alignment outcomes[27].

Functional annotation

-

Unigenes were annotated using DIAMOND version 2.0.15 against databases such as NR, Swiss-Prot, COG, KOG, and KEGG[28]. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed with InterProScan version 5.34-73.0[29]. The TFs and families were identified using iTAK version 1.7a[30]. The coding potential of transcripts was assessed using four standard methods of protein domain analysis, including Coding Potential Calculator (CPC), Coding-Non-Coding Index (CNCI), Coding Potential Assessment Tool (CPAT), and Protein Family Database (Pfam), to classify them as lncRNA or protein-coding[31]. The AS event identification and comparison were conducted using ASTA-LAVISTA software[32].

Differential expression analysis

-

Gene expression was quantified using the fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) method. Differential expression analysis between two conditions or groups was conducted using the DESeq2 R package version 1.6.3. DESeq2 offers statistical methods to determine differential gene expression from digital gene expression data, employing a negative binomial distribution model. The resulting p-values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate (FDR). Genes identified by DESeq as having an FDR below 0.01 and a fold change (FC) of at least 2 were deemed differentially expressed. Pearson correlation coefficients were utilized for the correlation analysis between gene expressions and volatile contents.

Gene expression analysis

-

Based on sequencing results, Real-time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) was used to verify the key gene expressions. The actin gene was selected as an internal control for data normalization[8]. The RT-qPCR primers were designed using PrimerQuestTM Tool (Supplementary Table S1). The RT-qPCR reaction system was prepared with the MonAmpTM ChemoHS qPCR Mix Kit from Monad (Monad, Guangzhou, China). The RT-qPCR procedure was performed using the Lightcycler 96 instrument from Roche (Roche, Penzberg, Germany). The expression levels were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method.

-

To systematically explore the aroma profiles of basil (O. basilicum var. pilosum) in Hainan Island, the stems and leaves at different developmental stages were selected for volatile metabolome analysis (Fig. 1a). A total of 151 VOCs were identified in basil leaves and stems (Supplementary Table S2). The peak area normalization was used to establish the relative content of each substance in the sample. Significant differences in the relative total content of volatiles were observed that the leaf content (L1 and L2) notably exceeded the stem content (S1 and S2) (Fig. 1b). The L1 exhibited the highest content of volatile compounds, being 1.16, 5.12, and 38.95 times higher than those in L2, S1, and S2, respectively (Fig. 1b). Leaves are the main source of VOCs in O. basilicum var. pilosum.

Figure 1.

Volatile compound analysis in developing basil leaves and stems. (a) Basil stems and leaves at various developmental stages selected for volatile compound analysis. (b) Relative content of volatile compounds in basil, comparing stems and leaves. (c) Classification and statistical analysis of volatile compounds. (d) Comparative content of compound groups, including terpenes, phenylpropanes, fatty acid derivatives, amino acid derivatives, and others in basil stems and leaves. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences, while the same letters indicate no significant differences (p < 0.05). One-way analysis of variance and q-test were used for data analysis.

Based on molecular structure, these VOCs were categorized into 52 terpenes (34.4%), 25 phenyl/phenylpropanes (16.6%), 17 fatty acid derivatives (11.3%), 20 amino acid derivatives (13.2%), and 37 others (24.5%) (Fig. 1c). Although terpenoids were the most diverse group, phenyl/phenylpropanes of L1 and L2 had the highest relative content (Fig. 1d). The relative contents of phenyl/phenylpropanes accounted for 50.24% and 52.62% of the total contents in L1 and L2, respectively. These ten most abundant volatiles in content, including methyl cinnamate, anethole, bicyclo[5.2.0]nonane,2-methylene-4,8,8-trimethyl-4-vinyl-, 1,4,7,-cycloundecatriene,1,5,9,9-tetramethyl-,Z,Z,Z-, cis-α-Bergamotene, fenchyl acetate, linalyl acetate, 3-carene, fenchone, and fenchol, constituted over 50% of the total detections in each sample (Supplementary Table S2).

Differential metabolite analysis

-

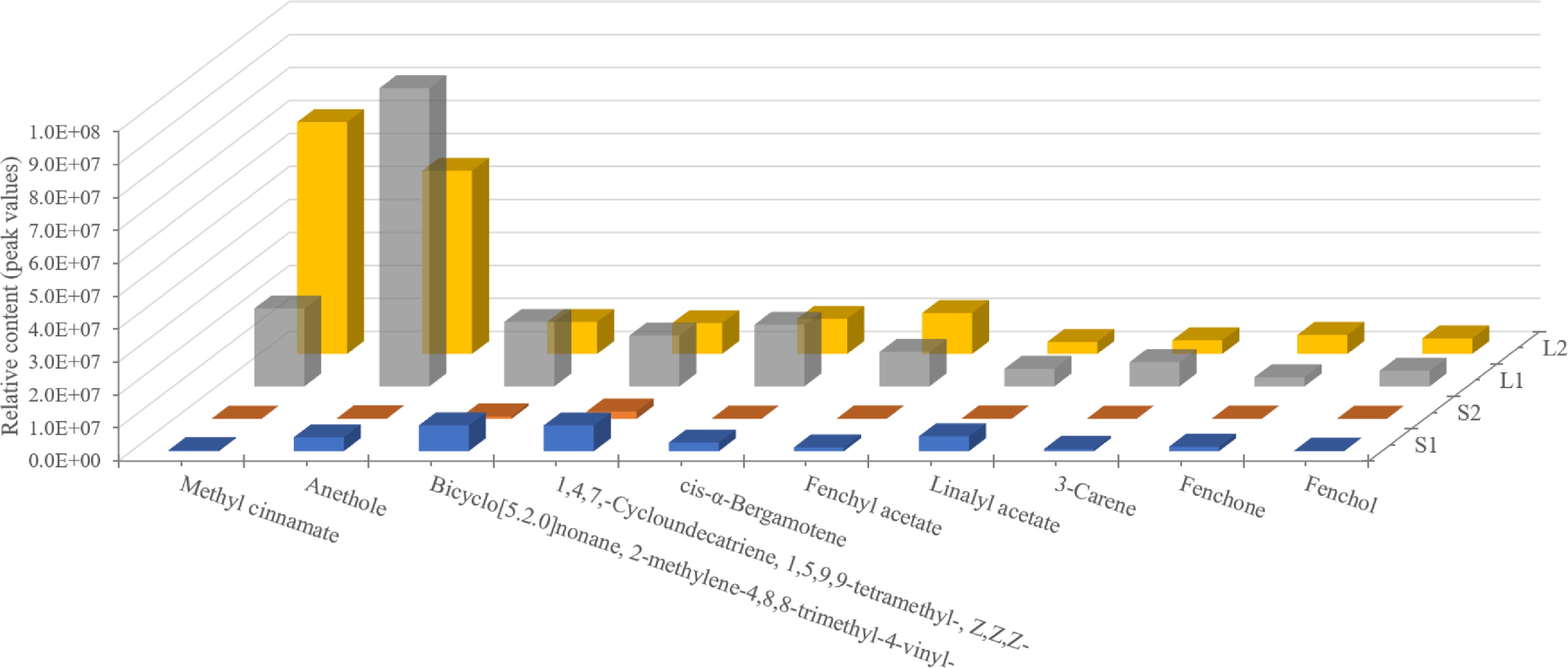

Volatile compounds with a variable importance in projection score of 1 or higher and an FC of 1 or greater were considered significant. Through pairwise comparison, 144 differential metabolites were identified, accounting for 95.36% of the total volatile compounds, suggesting significant differences between groups (Supplementary Fig. S1). The top ten metabolites showed consistent relative content differences, particularly an up-regulation in leaves (Fig. 2). A prominent finding from the analysis was that methyl cinnamate and anethole were predominant in basil essential oil, with the highest concentrations in L2 and L1 tissues, respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The content analysis of the top ten volatile compounds in basil leaves and stems at various developmental stages. Methyl cinnamate and anethole (phenyl/phenylpropanes) are the predominant components of the essential oil.

Transcriptome analysis

-

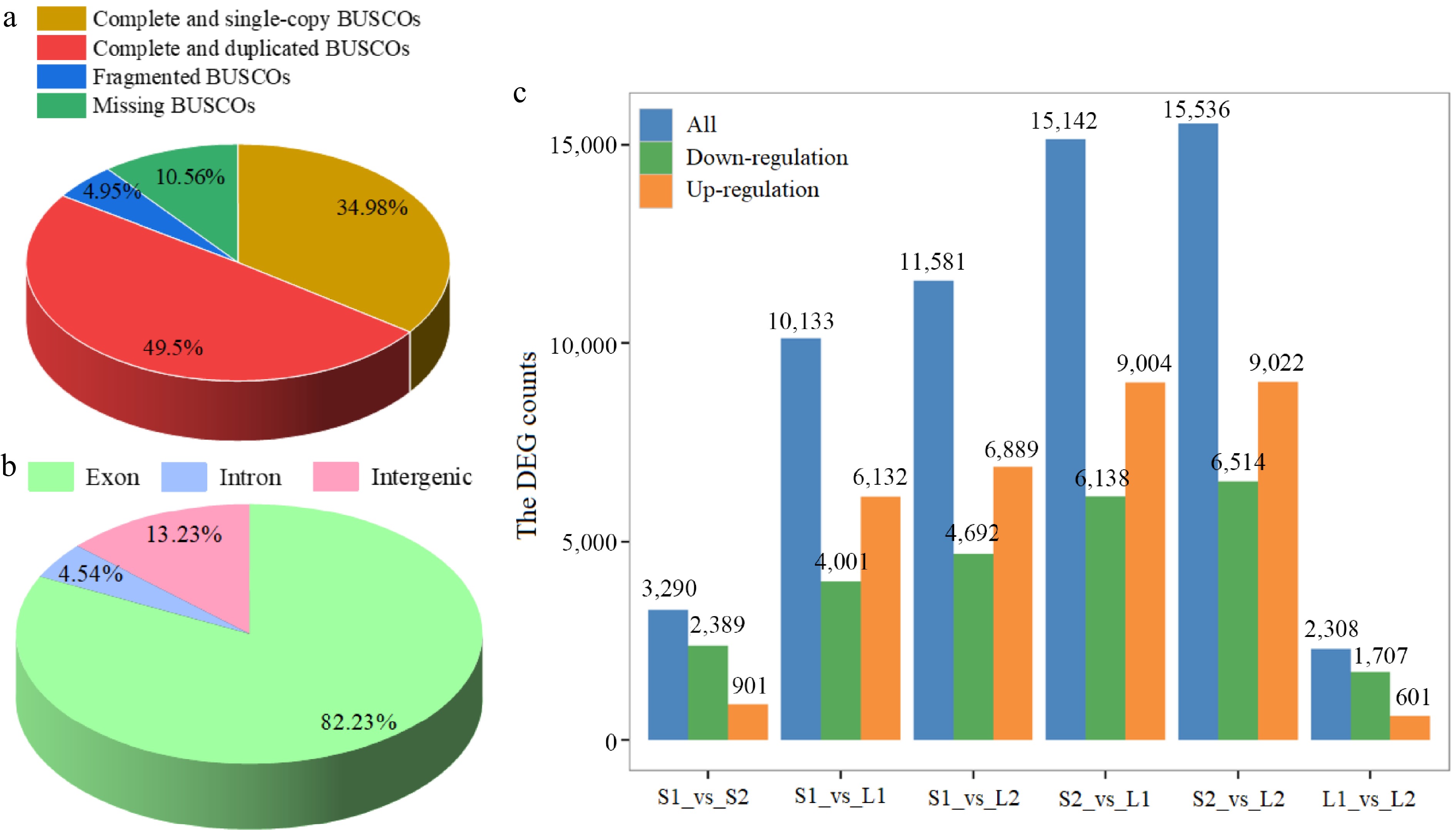

For transcriptomic analysis of O. basilicum var. pilosum, the raw data generated from Illumina and PacBio sequencing were stored in the Genome Sequence Archive of the National Genomics Data, with accessions CRA013854 and CRA013868, respectively. A total of 405,393 circular consensus reads were obtained, including 326,179 full-length non-chimeric sequences (FLNC). The FLNC reads were clustered to obtain consensus sequences that were then polished to obtain a total of 147,361 high-quality consensus sequences. After calibration and de-redundancy with high-quality consensus sequences, a total of 79,867 unique transcript sequences were obtained.

Additionally, quality assessment using the BUSCO tool indicated that complete sequences constituted 84.48% of the conserved core eukaryotic genes (Fig. 3a). Based on the basil genome data[22], the high-quality clean reads were mapped to the reference genome. According to the statistics of the comparison results, the comparison efficiency between reads of each sample and reference genome ranged from 83.42% to 84.17% (Supplementary Table S3). Furthermore, 82.23% of the reads mapped to exonic regions of the genome, 4.54% to intronic regions, and 13.23% to intergenic regions (Fig. 3b). A total of 7,843 novel genes were identified, and 3,495 genes were annotated by comparing against public databases (Supplementary Table S4).

Figure 3.

Statistical analysis of transcriptome data. (a) BUSCO tool quality assessment categorized proportions as complete and single-copy (dark yellow), complete and duplicated (red), fragmented (blue), and missing (green). (b) Distribution of reads across various genome regions. (c) Differential expression analysis. Normalization and differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2.

Subsequently, gene expression levels were standardized to FPKM. The screening criteria for DEGs were an FC of at least 2 and an FDR below 0.01. The S2_vs_L2 comparison exhibited the highest number of DEGs, with 6,514 down-regulated and 9,022 up-regulated genes, while the L1_vs_L2 comparison had the fewest, with 1,707 down-regulated and 601 up-regulated genes (Fig. 3c). A total of 20,405 DEGs were identified with significant differences in at least one group (Supplementary Table S5).

Identification of transcription factors

-

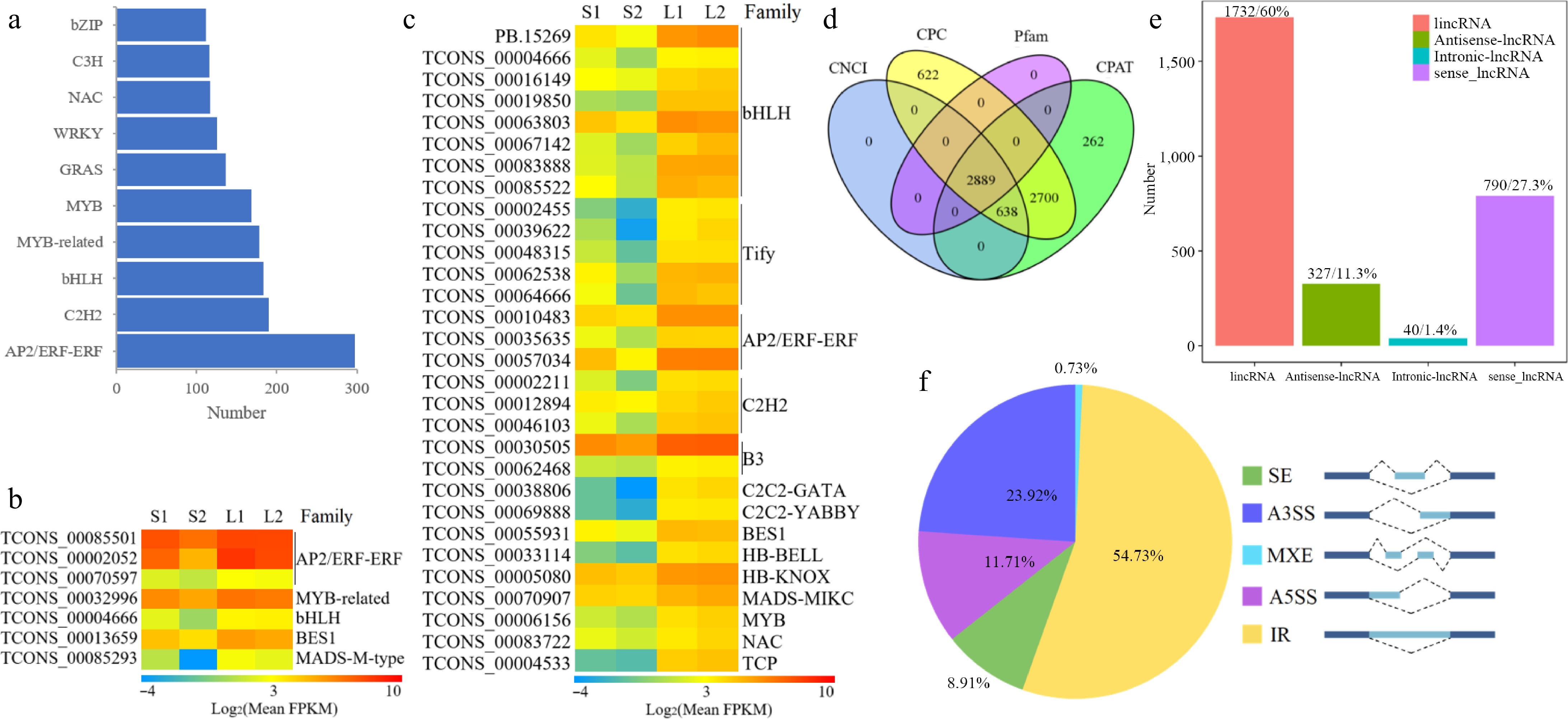

Utilizing iTAK software, a total of 3,129 TFs were identified to code 4,102 transcripts, which could be divided into 67 families (Supplementary Table S6). The three largest families are AP2/EREBP with 297 members, C2H2 with 190 members, and bHLH with 183 members (Fig. 4a). A total of 919 transcripts from basil TF families exhibited differential expression (Supplementary Table S7). Notably, the expression levels of seven TFs showed a very strong positive correlation (r ≥ 0.9) with anethole content, including TCONS_00085501, TCONS_00002052, and TCONS_00070597 from the AP2/ERF family, and one each from MYB-related (TCONS_00032996), bHLH (TCONS_00004666), BES1 (TCONS_00013659), and MADS-M-type (TCONS_00085293) families (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, the expression of 30 TF genes demonstrated an extremely strong positive correlation (r ≥ 0.9) with the content of methyl cinnamate, including eight bHLH members (PB.15269, TCONS_00004666, TCONS_00016149, and others), five Tify members (TCONS_00002455, TCONS_00039622, TCONS_00048315, and others), three AP2/ERF members (TCONS_00010483, TCONS_00035635, and TCONS_00057034), three C2H2 members (TCONS_00002211, TCONS_00012894, and TCONS_00046103), and so forth (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4.

Transcriptomic structure analysis in O. basilicum var. pilosum. (a) Ranking and distribution of the top ten TF families. (b), (c) Heatmaps of TFs with extremely positive correlations to anethole and methyl cinnamate content, respectively. The FPKM data were log2 transformed with a pseudocount (FPKM + 0.01). Red indicates the highest value, green the lowest, and yellow the median on the heatmap. (d) A Venn diagram displaying the lncRNA outcomes of four screening methods. (e) Classification of lncRNAs based on their genomic locations. (f) Statistical overview of AS events. A3SS: Alternative 3' Splice Site; A5SS: Alternative 5' Splice Site; MXE: Mutually Exclusive Exon; IR: Intron Retention; SE: Skipped Exon.

LncRNA identification and alternative splicing

-

The lncRNAs are RNA molecules that do not encode proteins. Coding potential is thus a key criterion for classifying transcripts as lncRNAs. A total of 2,889 lncRNA transcripts were identified through the integration of results from four prediction tools: CNCI, CPC, Pfam, and CPAT (Fig. 4d). Leveraging the known reference genome, these lncRNAs were categorized into four types: 1,732 long intergenic non-coding RNAs (lincRNAs), 327 antisense lncRNAs, 40 intronic lncRNAs, and 790 sense lncRNAs (Fig. 4e). We predicted potential target genes of lncRNAs based on two interaction modes with mRNAs. Firstly, lncRNAs can regulate nearby gene expression, leading us to identify 33,405 cis-target DEGs within 100 kb upstream and downstream of lncRNAs (Supplementary Table S8). The second interaction mode involves base-pairing complementarity between lncRNAs and mRNAs. We predicted that 1,636 lncRNAs target 17,767 genes through complementary sequences (Supplementary Table S9).

A total of 10,427 AS events were identified using Astalavista software (Supplementary Table S10). The classification and statistics categorized the AS events into five types. Intron retention (IR) was the most prevalent, accounting for 5,707 events (54.73%), followed by alternative 3' splice site (A3SS, 2,494 events for 23.92%), alternative 5' splice site (A5SS, 1,221 events for 11.71%), skipped exon (SE, 929 events for 8.91%), and mutually exclusive exon (MXE, 76 events for 0.73%) (Fig. 4f).

Reconstructing the biosynthetic pathway of methyl cinnamate and anethole

-

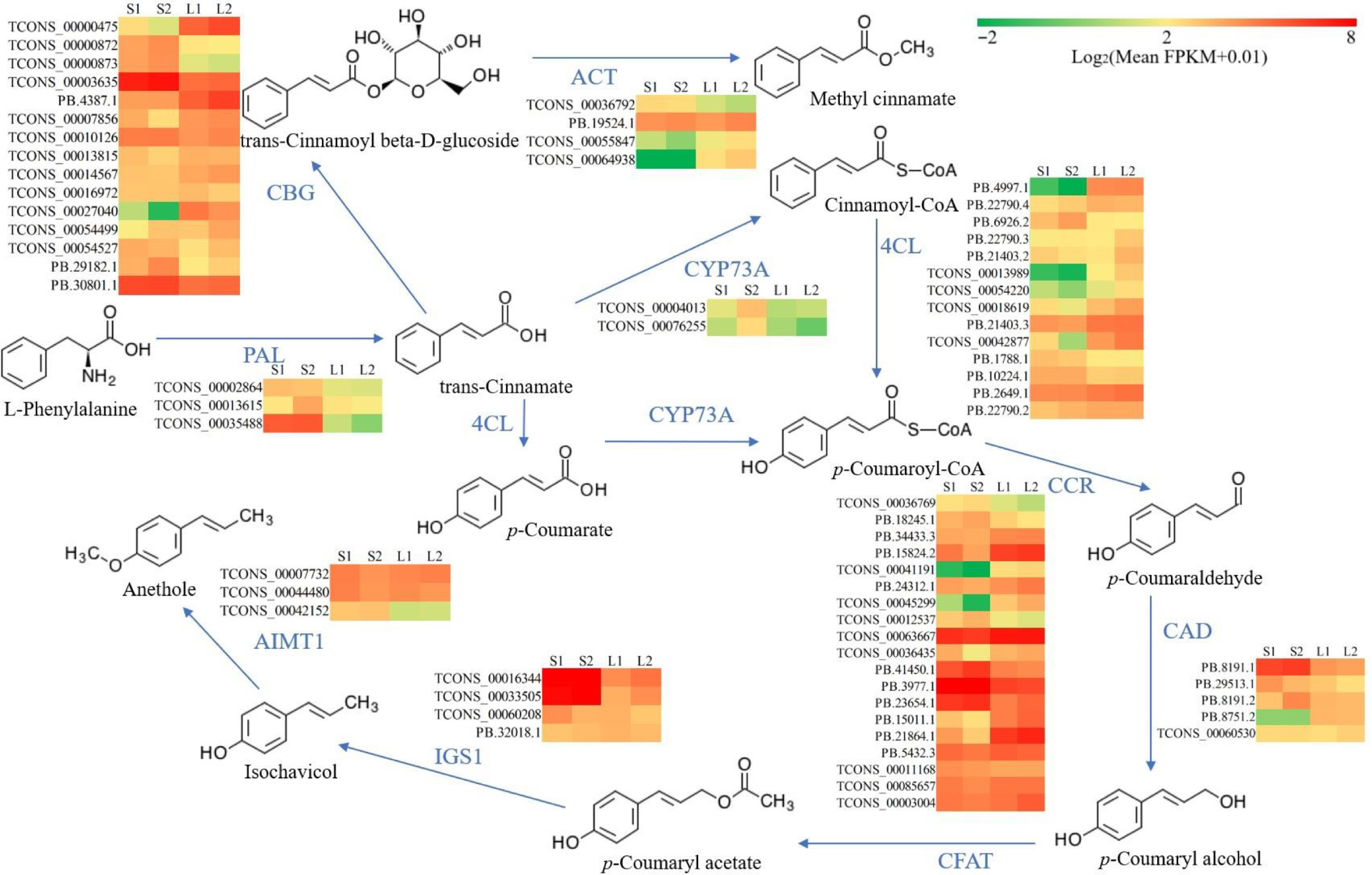

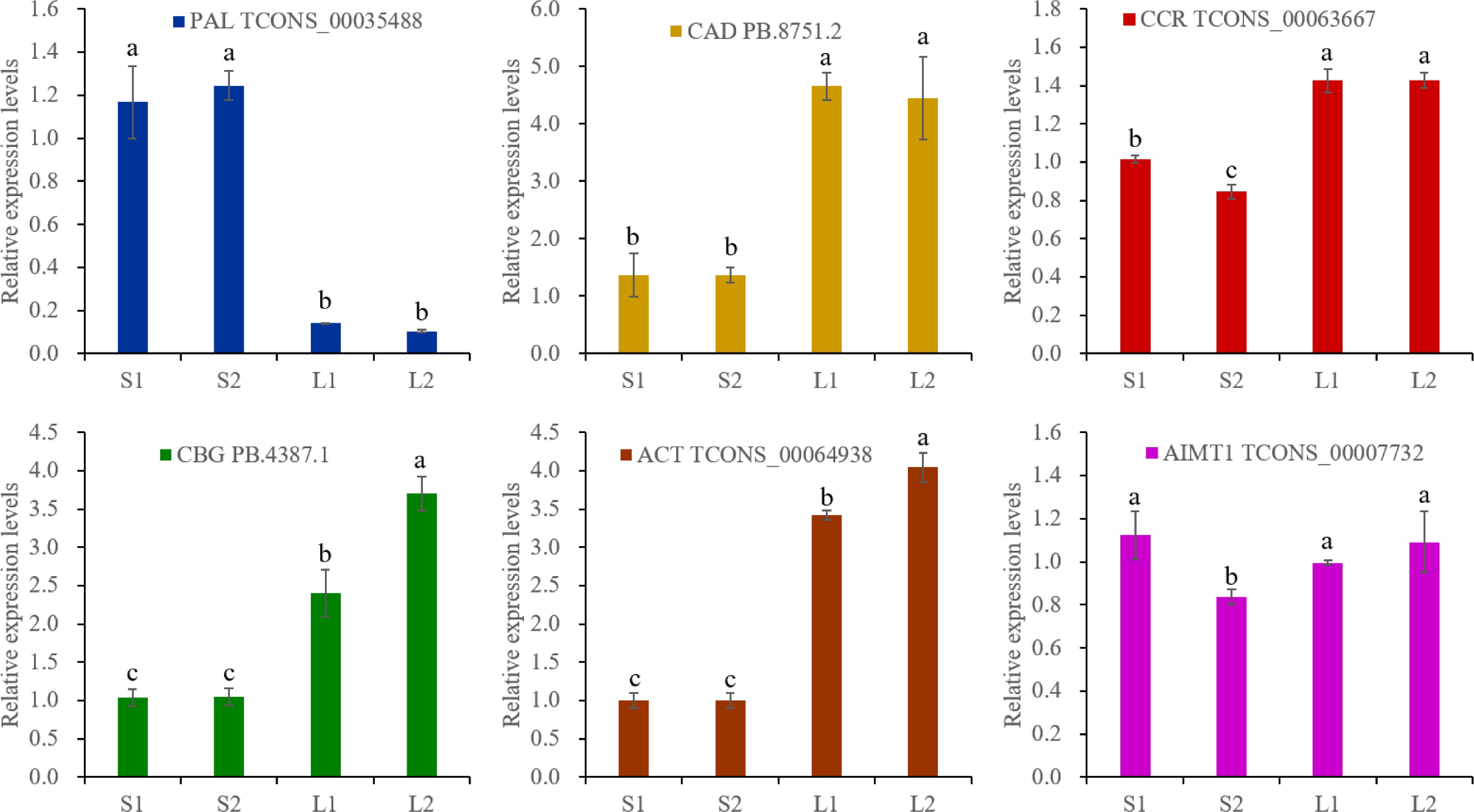

The predominant VOCs in O. basilicum var. pilosum from Hainan Island are methyl cinnamate and anethole, both phenylpropanoid derivatives. Based on functional annotation results, the biosynthetic pathways for methyl cinnamate and anethole were reconstructed (Fig. 5). The phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) enzyme catalyzes the initial step of the phenylpropanoid pathway, initiating phenolic biosynthesis. A total of 16 PAL genes were annotated, and differential expression analysis indicated that three PAL genes (TCONS_00002864, TCONS_00013615, and TCONS_00035488) showed significantly higher expression levels in stems, especially in lignified stem (Figs 5 & 6; Supplementary Table S11). For the biosynthetic pathway of methyl cinnamate, 88 cinnamate beta-D-glucosyltransferase (CBG), and 75 alcohol O-cinnamoyltransferase (ACT) genes were identified (Supplementary Table S11). The majority of these pathway genes exhibited low expression levels (FPKM ≤ 2), yet 15 CBG and four ACT genes were identified as DEGs (Fig. 5; Supplementary Table S11). Notably, the expression levels of two CBG (TCONS_00000475 and PB.4387.1) and two ACT (TCONS_00055847 and TCONS_00064938) displayed a strong positive correlation with methyl cinnamate content (r ≥ 0.9) (Figs 5 & 6). These four genes are likely to play key roles in the biosynthesis of methyl cinnamate.

Figure 5.

Reconstruction of the biosynthetic pathway for methyl cinnamate and anethole. Color coding in the pathway indicates relative expression levels, with red for the highest FPKM values, green for moderate levels, and yellow for median values. 4CL, 4-coumarate--CoA ligase; ACT, alcohol O-cinnamoyltransferase; AIMT1, trans-anol O-methyltransferase; CAD, cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase; CBG, cinnamate beta-D-glucosyltransferase; CCR, cinnamoyl-CoA reductase; CFAT, coniferyl alcohol acyltransferase; CYP73A, trans-cinnamate 4-monooxygenase; PAL, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase; IGS1, isoeugenol synthase.

Figure 6.

RT-qPCR analysis. The actin gene was selected as an reference gene. The expression levels were calculated by 2−ΔΔCᴛ. Different lowercase letters represent significant differences, and the same lowercase letters represent no significant differences (p < 0.05). One-way analysis of variance and q-test were used for data analysis.

The trans-cinnamate 4-monooxygenase (CYP73A), 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL), cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), and cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD) enzymes catalyze the conversion of trans-cinnamate to p-coumaryl alcohol (Fig. 5). A total of 17 CYP73A, 88 4CL, 91 CCR, and 16 CAD genes were annotated (Supplementary Table S11). Differential expression analysis revealed that two CYP73A genes (TCONS_00004013 and TCONS_00076255) were DEGs with elevated expression in lignified stems (Fig. 5; Supplementary Table S11). Additionally, the DEGs of 14 4CL, 19 CCR, and five CAD exhibited diverse expression patterns (Fig. 5; Supplementary Table S11). It was worth noting that the expressions of two 4CL genes (PB.4997.1 and PB.21403.3) correlated positively (0.8 ≤ r < 0.9) with anethole content, and one CCR (TCONS_00063667) and one CAD (PB.8751.2) showed a strong positive correlation (r ≥ 0.9) (Supplementary Table S11).

Anethole biosynthesis initiates with the acetylation of p-coumaryl alcohol, a pathway branch of phenylpropanoids. Functional annotation identified six coniferyl alcohol acyltransferase (CFAT), 24 isoeugenol synthase (IGS1), and 12 trans-anol O-methyltransferase (AIMT1) genes in O. basilicum var. pilosum (Supplementary Table S11). Unexpectedly, all CFAT genes displayed extremely low/no expression (Supplementary Table S11). Despite identifying four IGS1 and three AIMT1 genes as DEGs, no gene expression correlated positively with anethole content (Fig. 5; Supplementary Table S11).

-

Basil, a globally popular culinary herb, is highly versatile and rich in aromatic and bioactive compounds[33]. The VOCs contribute to the plant's distinctive aroma and its pharmacological properties. However, there is a scarcity of reports detailing the aroma profiles of the VOCs in O. basilicum var. pilosum. As a variety of O. basilicum, this basil thrives in tropical and subtropical climates, establishing it as a prominent aromatic crop in these regions[8]. Its essential oil is traditionally utilized in folk medicine for treating diverse ailments[9]. Despite its aromatic qualities and economic value, the complex mechanisms underlying the biosynthesis of its essential oils are not well understood. Understanding these processes is essential for both optimizing the yield and quality of basil oil and for exploiting its medicinal potential in developing new pharmaceutical and nutraceutical products.

Existing literature primarily investigates the VOCs from the aerial parts of basil[7]. Consequently, stems and leaves at various developmental stages were selected for volatile metabolome analysis. Basil leaves, as expected, are a primary source of essential oils (Fig. 1b)[34,35]. Despite terpenes and phenylpropanes being identified as the primary VOCs in all basil (O. basilicum) plants, the types and contents of their main VOCs exhibited significant differences[3,8,9]. Methylchavicol and methyleugenol dominated in O. basilicum from the Western Ghats of North West Karnataka[35], whereas linalool, p-allylanisole, geraniol, 1,8-cineole, neryl acetate, and trans-α-bergamotene were predominant in O. basilicum from the Muscat Governorate, Sultanate of Oman[36]. Iranian O. basilicum (Charmahal va Bakhtiari Province) showed linalool and methylchavicol as major constituents among 65 components[37]. As for O. basilicum var. pilosum from Shandong Province, China, the main VOCs were linalool and methyl cinnamate[9]. However, a higher relative percentage of phenyl/phenylpropanes was observed in O. basilicum var. pilosum from Hainan Province, China (Fig. 1d). Methyl cinnamate and anethole are recognized as the primary aroma components (Fig. 2). Notably, all compared accessions belong to the O. basilicum species complex, ensuring taxonomic comparability while highlighting intraspecific variation. Variability in basil VOCs is attributed to factors such as geographical origin, environmental conditions, and genetics[4,13]. Thus, investigating the biosynthetic mechanism of methyl cinnamate and anethole in O. basilicum var. thyrsiflora from Hainan Island is essential.

Previous studies on basil transcriptomes primarily utilized second-generation sequencing technology[8,17,19,38]. However, second-generation sequencing technology has a notable limitation in read length. The assembly of short reads resulted in full-length transcripts with relatively low quality[39]. Third-generation sequencing technology addresses the limitations of short-read sequencing by producing full-length sequences from single molecules[40]. The combination of second- and third-generation sequencing technologies identified 79,867 high-quality transcripts, providing a robust dataset for characterizing key genes in essential oil biosynthesis. Furthermore, the high sequence mapping coverage (84.48% as assessed by BUSCO analysis) indicates the satisfactory quality of the full-length transcripts obtained through SMRT sequencing in this study. Although the genome sequencing of O. basilicum var. thyrsiflora remains incomplete, the genome data of O. basilicum (a closely related species) is available in the CoGe database[22]. Approximately 82.23% of the reads were mapped to exonic regions (Fig. 3b), indicating that the reference genome is relatively comprehensive. However, there are still 13.23% of the reads mapped to intergenic regions (Fig. 3b). Additionally, 4.45% of reads mapped to intron regions may result from alternative pre-mRNA splicing, particularly intron retention (IR) events 4.45% of reads mapped to intron regions may be attributed to alternative pre-mRNA splicing, particularly IR events[41]. To further investigate gene functions in O. basilicum var. thyrsiflora, whole genome sequencing is essential.

It is well established that TFs play a crucial role in regulating phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. For instance, the NtERF13a gene from AP2/ERF-ERF family in Nicotiana tabacum is known to enhance the synthesis of phenylpropanoid compounds[42]. Correlation analysis indicated that three genes from the AP2/ERF family may participate in the biosynthetic regulation of methyl cinnamate and anethole (Fig. 4b & c). Importantly, MYBs are pivotal in regulating the synthesis of phenylpropanoid-derived compounds in plants[43]. TCONS_00006156 and TCONS_00032996 were identified as potentially involved in regulating the biosynthesis of methyl cinnamate and anethole, respectively (Fig. 4b & c). Interestingly, the expression of eight bHLH members and five Tify members showed an extremely strong positive correlation with the content of methyl cinnamate (Fig. 4c). In Litsea cubeba, a high-monoterpene aromatic plant, transient overexpression of LcbHLH78 significantly increased geraniol and linalool production, highlighting its direct impact on terpenoid accumulation[44]. Moreover, bHLHs often interact with other transcriptional regulators, such as MYBs and WD-repeat proteins, to form combinatorial networks that fine-tune pathway-specific gene expression[45]. The Tify transcription factor family is central to jasmonate signaling, which regulates secondary metabolite production under stress conditions. The Tify proteins interact with bHLH regulators (e.g., MYC2) to repress or activate jasmonate-responsive genes, thereby indirectly influencing alkaloid and terpenoid biosynthesis[46]. However, detailed mechanistic insights into TF roles in the VOC metabolism of O. basilicum var. thyrsiflora remain limited and require further research.

The biosynthesis of both methyl cinnamate and anethole begins with L-phenylalanine, originating from the phenylalanine biosynthesis pathway. The PAL catalyzes the initial step in the phenylpropanoid pathway, converting L-phenylalanine to trans-cinnamate[47]. Hydroxylation and methylation of trans-cinnamate result in coumaric acid and related phenylpropane acids, which are reduced to form monolignols, the precursors for lignin biosynthesis when their CoA-activated carboxyl groups are involved[48]. Notably, all DEGs associated with PAL and CYP73A showed high expression levels in stems (Fig. 5). This could be attributed to the higher lignin content in stems compared to leaves, as lignin biosynthesis is generally more critical than volatile compound biosynthesis in plants. The high expression levels of related genes, such as those from the 4CL, CCR, and CAD families, in basil stems, are thus explained (Fig. 5). Additionally, some members of the 4CL, CCR, and CAD gene families exhibited high expression levels in basil leaves as well. Variations in expression patterns among members of the same gene families across different tissues may correspond to functional differences[49]. Genes with high expression levels in leaves merit further scrutiny.

In the biosynthesis of methyl cinnamate, trans-cinnamate is initially glycosylated to form trans-cinnamoyl beta-D-glucoside, followed by the substitution of the glycosyl group with a methyl group[50]. The CBG and ACT genes belong to glycosylase and methylase family, respectively. It is well established that both glycosylase and methylase families have numerous members capable of modifying diverse substrates. Consequently, the diversity in their expression patterns can be attributed to functional diversity. Importantly, TCONS_00000475 and PB.4387.1 of the CBG family and TCONS_00055847 and TCONS_00064938 of the ACT family were found to be correlated with the biosynthesis of methyl cinnamate. Further functional in vitro and in vivo studies are required to investigate these associations more thoroughly. Regrettably, although potential genes involved in anethole biosynthesis were identified, correlation analysis showed no association with anethole accumulation. In particular, all CFAT genes, encoding the key enzyme for the first step in the specific pathway of anethole biosynthesis[51], showed extremely low/no expression both in stems and leaves (Supplementary Table S8). Further exploration is essential to identify the key genes and elucidate their roles in anethole biosynthesis.

-

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of the volatile metabolome and transcriptome of O. basilicum var. pilosum, revealing intricate details of the biosynthetic pathways for its aromatic compounds. A total of 151 volatile compounds were identified, predominantly terpenes and phenyl/phenylpropanes. The discovery of 7,843 novel genes and the in-depth examination of 20,405 DEGs lay the foundation for subsequent analysis. Furthermore, the identification of TFs, lncRNAs, and AS events introduce an additional layer of complexity into the regulatory network governing the biosynthesis of aromatic compounds. The correlation analysis successfully captured key genes for the biosynthesis of aromatic compounds, including methyl cinnamate and anethole. This study significantly advances our understanding of the biosynthetic pathways in O. basilicum var. pilosum and provides valuable insights for the development of strategies to enhance the quality and yield of aromatic compounds.

This research was funded by the Collaborative Innovation Center Project of Hainan University (Grant No. XTCX2022STC03), and the Hainan University Research Project (Grant No. KYQD(ZR)-22056).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Niu J; validation, Yi A, Wang Z; formal analysis: Ou Q, You H; investigation: Ou Q, You H; data curation: Xie Q, Gao L; writing - original draft preparation: Ou Q, You H; visualization: Yi A, Wang Z; supervision: Wang J, Niu J; funding acquisition: Wang J, Niu J; writing - review and editing: Niu J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Genome Sequence Archive of National Genomics Data (Access Nos CRA013854 and CRA013868).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Qiongjian Ou, Huiyan You

- Supplementary Table S1 The primers for RT-qPCR.

- Supplementary Table S2 Detection of volatile metabolites from leaves and stems of O. basilicum var. pilosum.

- Supplementary Table S3 The sequencing information of samples and statistics of comparison between sample and reference genome.

- Supplementary Table S4 The annotation results of new genes.

- Supplementary Table S5 Differential expression results per gene.

- Supplementary Table S6 The family annotation of candidate transcription factors.

- Supplementary Table S7 The differential expression of candidate transcription factors.

- Supplementary Table S8 The prediction of target genes of lncRNAs based on physical location.

- Supplementary Table S9 The prediction of target genes of lncRNAs based on complementary sequences.

- Supplementary Table S10 Variable splicing analysis.

- Supplementary Table S11 All the genes involved in the biosynthesis pathway of methyl cinnamate and anethole.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Heatmap of all the differential metabolites.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ou Q, You H, Yi A, Wang ZH, Xie Q, et al. 2025. Metabolome and transcriptome revealed the biosynthesis pathway of aromatic compounds in Ocimum basilicum var. pilosum. Ornamental Plant Research 5: e025 doi: 10.48130/opr-0025-0024

Metabolome and transcriptome revealed the biosynthesis pathway of aromatic compounds in Ocimum basilicum var. pilosum

- Received: 29 August 2024

- Revised: 25 March 2025

- Accepted: 08 April 2025

- Published online: 13 June 2025

Abstract: The aromatic plant Ocimum basilicum var. pilosum, a Lamiaceae family member, is renowned for volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which have diverse applications in the culinary, medicinal, and aromatic industries. Despite its high economic and aromatic value, the biosynthetic pathway of VOCs is not well understood. This study employed metabolomic and transcriptomic approaches to explore the biosynthesis of VOCs in O. basilicum var. pilosum. Volatile metabolome analysis identified 151 compounds, with leaves serving as the primary source of VOCs. Phenylpropanes were identified as the major components, accounting for approximately 50% of the total VOC content in leaves, with methyl cinnamate and anethole being the predominant constituents. Illumina and PacBio sequencing identified 7,843 novel genes and 20,405 differentially expressed genes. Correlation analyses indicated that several transcription factors, including AP2/ERF-ERF, bHLH, and MYB families, are involved in the biosynthesis of methyl cinnamate and anethole. Additionally, the study identified 2,889 long non-coding RNAs and 10,427 instances of alternative splicing. Importantly, the biosynthetic pathways for methyl cinnamate and anethole were reconstructed. Two CBG genes (TCONS_00000475 and PB.4387.1) and two ACT genes (TCONS_00055847 and TCONS_00064938) were found to correlate with methyl cinnamate biosynthesis, whereas no gene expression showed a positive correlation with anethole content. This study elucidates the metabolic pathways and regulatory mechanisms underlying the biosynthesis of aromatic compounds in O. basilicum var. pilosum. The findings provide a foundation for enhancing the quality and yield of essential oils, offering valuable insights into the molecular breeding and cultivation strategies of aromatic plants.

-

Key words:

- Aromatic compound /

- Ocimum basilicum var. pilosum /

- Metabolome /

- Transcriptome /

- Phenylpropanoid