-

The G protein-mediated signaling network is a widespread signal perception mechanism in eukaryotes, existing from fungi to humans. It constitutes one of the most complex receptor-effector signaling networks. G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) serve as the origin and central component of G protein signaling networks in animals, forming a large and functionally diverse family. Their hallmark feature is a conserved seven-transmembrane (7TM) domain[1−3]. This domain features an extracellular N-terminus and seven hydrophobic α-helical segments. Each segment is approximately 20−25 amino acids long and is connected by alternating intracellular and extracellular loops, terminating in a cytoplasmic C-terminus. Although GPCR classification schemes continue to evolve[4], traditionally, there are mainly two classification methods[5,6].

The heterotrimeric G protein, localized to the plasma membrane, comprises Gα, Gβ, and Gγ subunits. In the classical paradigm established in animals[7−11], the G protein cycles between active and inactive states governed by the nucleotide bound to the Gα subunit. In the resting state, Gα is GDP-bound and associated with the Gβγ dimer. Upon ligand or signal perception by the plasma membrane-localized GPCR, the GPCR acts as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF). This GEF activity facilitates the exchange of GDP for GTP on Gα, concurrently triggering dissociation of Gα from the Gβγ dimer. The liberated Gα-GTP and Gβγ subunits subsequently interact with distinct downstream effectors to propagate signaling. Gα possesses intrinsic GTPase activity, hydrolyzing bound GTP to GDP. This hydrolysis enables Gα to reassociate with Gβγ, thereby resetting the heterotrimer to its basal GDP-bound, inactive state. Consequently, the GEF activity of the GPCR governs the transition between the activated (GTP-bound) and inactivated (GDP-bound) states of the G protein signaling cycle[12]

However, the search for canonical GPCRs in plants has proven elusive and contentious. Initial bioinformatic analyses revealed a striking absence of clear homologs to animal GPCRs in plant genomes[13,14]. This observation, coupled with evidence suggesting that plant Gα subunits can self-activate without receptor mediation, led to a period of skepticism regarding the very existence of plant GPCRs. Despite this, compelling genetic and physiological evidence has consistently pointed to the involvement of specific membrane proteins in G protein-coupled processes, from hormone signaling to environmental responses. This paradox set the stage for a fundamental reconceptualization of the GPCR paradigm in plants. It is now appreciated that plants possess a suite of 'GPCR-like' receptors which fulfill the core functional role of a GPCR—coupling extracellular signals to heterotrimeric G protein activation—but do so through novel and often unexpected structural forms and mechanistic rules.

Building upon previous research and this conceptual shift, this review undertakes to systematically summarize the canonical and non-canonical structural characteristics and evolution of plant GPCRs, while delving into their signaling mechanisms. This review synthesizes current understanding of how these atypical receptors integrate hormonal and environmental signals to coordinate critical processes such as stress tolerance, immunity, and development. By studying plant hormones and environmental signaling pathways, this work seeks to offer new insights and theoretical support for the field, helping to better understand the biological roles of plant GPCRs.

-

The research path of plant GPCRs has been complicated and debated. Over two decades ago, researchers employed probes based on sequence similarity, leveraging associations between plant Expressed Sequence Tag (EST) sequences and known GPCR sequences, to isolate GCR1 cDNA from an Arabidopsis library for the first time. Notably, GCR1 was observed to possess a 7TM domain[15]. Subsequent studies provided substantial support for GCR1 as a plant GPCR candidate. A seminal investigation in 2004, employing in vitro pull-down assays, co-immunoprecipitation, and split-ubiquitin assays, demonstrated a physical interaction between GCR1 and the Arabidopsis Gα subunit (GPA1)[16]. This study linked GCR1 to abscisic acid (ABA) signaling and drought responses, and it supports GCR1 as a GPCR with functional and biochemical evidence. Additionally, the Ma Ligeng group reported another G protein-coupled receptor functioning as a receptor for the plant hormone ABA[17]. This work identified a novel GPCR in Arabidopsis, named GCR2, and established that GCR2 and Gα cooperatively regulate known ABA responses. Experiments showed that ABA specifically binds to the GCR2 protein, exhibiting characteristics typical of ligand-receptor binding. ABA binding to GCR2 causes the GCR2-Gα protein complex to split, freeing Gα to activate downstream effectors, which confirms GCR2 as an ABA receptor.

However, these findings were critically challenged by Urano & Jones[13], who argued that neither GCR1 nor GCR2 represents a bona fide GPCR. The debate hinges on the core defining criteria of GPCRs and the interpretation of experimental evidence. For GCR1, the central point of contention is its putative GEF activity—the definitive mechanism by which canonical GPCRs activate G proteins. While Pandey & Assmann[16] provided evidence for a physical interaction between GCR1 and GPA1 using in vitro pull-down assays and co-immunoprecipitation, critics argued that these methods demonstrate association but do not directly prove functional GEF activity. Urano & Jones[13] emphasized the lack of direct biochemical evidence, showing that GCR1 catalyzes nucleotide exchange on Gα. Furthermore, they pointed to genetic evidence suggesting GCR1's regulation of seed germination occurs independently of the heterotrimeric G protein, challenging its role within the classical GPCR-G protein coupling paradigm. Regarding GCR2, the controversy was more structural and methodological. The initial identification relied heavily on sequence-based predictions and binding assays. However, subsequent crystallographic analysis provided high-resolution structural data revealing that GCR2 lacks the canonical 7TM topology, and subcellular localization studies showed it was predominantly cytoplasmic—both findings being inconsistent with the defining features of a transmembrane GPCR. This led to its reclassification as a LanC-like protein, not a GPCR. A comparative summary of the key features distinguishing animal GPCRs from plant GPCR-like receptors is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparative analysis of animal GPCRs and plant GPCR-like receptors.

Feature Animal GPCRs Plant GPCR-like receptors Ref. Canonical topology 7TM 7TM or 9TM [13,21] Sequence motifs Conserved DRY, NPxxY / [2,18] Ligand perception Direct, high-affinity binding to single ligands Diverse: direct binding, indirect relay via complexes, mechano-sensing [14,19,21] GEF activity Ligand binding directly activates definitive GEF function Controversial/rare; often complex-dependent (PLS) or absent (GTG, COLD1) [13,14,18,21] G protein regulation Classical cycle: GPCR (GEF) → Gα-GTP → Effectors → GTP hydrolysis Diverse mechanisms: GEF (PLS), GAP (COLD1), GAP antagonism (GTG) [10,21] This rigorous reassessment, while dismissing GCR1 and GCR2 as canonical GPCRs, prompted a fundamental reconceptualization of the field[19]. Recognizing that plant GPCRs operate through distinct coupling mechanisms, research has moved beyond animal-centric criteria toward a more flexible, functionally-oriented framework. Current evidence points to a set of commonly observed characteristics that help define plant GPCR-like receptors[20,21]. These receptors often exhibit a seven- or nine-transmembrane (7TM or 9TM) topology and can perceive diverse stimuli, leading to conformational changes that facilitate direct interaction with G protein subunits. Crucially, this interaction results in the regulation of the G protein's nucleotide state through a range of mechanisms, which may include classical GEF activity, non-canonical GTPase-activating protein (GAP) functions, or other regulatory modes such as GAP antagonism. It is this central role in governing G protein activation, rather than strict adherence to animal GPCR motifs, that provides the most reliable functional basis for distinguishing plant GPCR-like receptors and has reoriented the field toward a more comprehensive exploration of these unique signaling components.

-

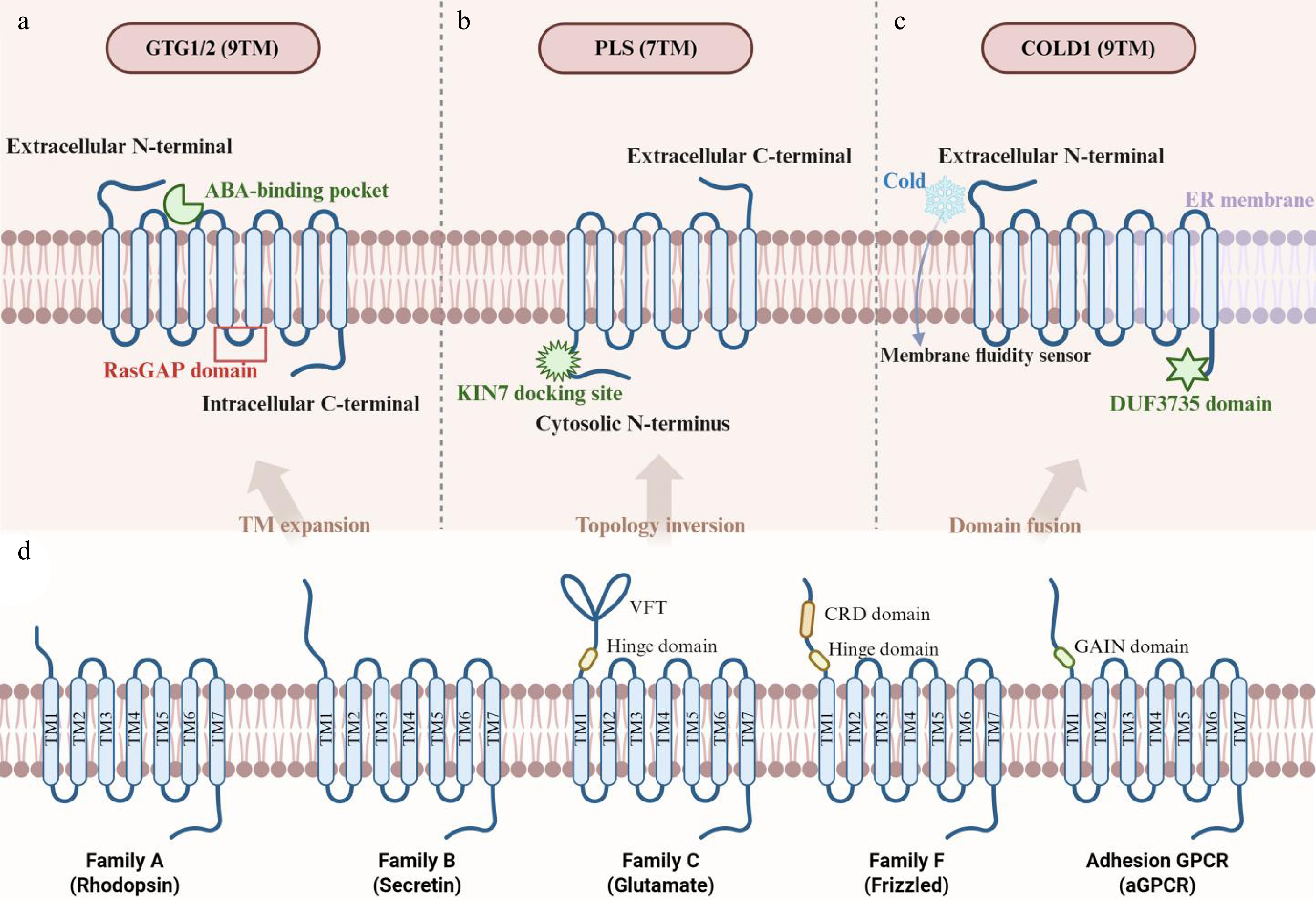

In animals, GPCRs regulate diverse physiological processes through their conserved 7TM structure and functional motifs. However, transmembrane proteins in plants exhibit significant sequence and functional divergence from animal GPCRs (Fig. 1), raising ongoing debate about their classification as true GPCRs.

Figure 1.

Structural diversity of plant GPCR-like receptors compared to animal GPCRs. Protein structures are depicted schematically, highlighting transmembrane topology and key functional domains. The plasma membrane is represented by a light pink band. (a) GTG1/2 (9TM topology): illustrates a 9TM topology with an extracellular N-terminus (N). The third intracellular loop (ICL3) contains a degenerate Ras GTPase-activating protein (GAP) domain, critical for its intrinsic GTPase activity and stereoselective abscisic acid (ABA) binding within the transmembrane core. (b) PLS (7TM topology): depicts a 7TM topology with a distinctive cytosolic N-terminus (N), which interacts with adapter proteins like KIN7. This topology facilitates integration into the PRR-KIN7-PLS complex for pathogen signal perception. (c) COLD1 (9TM topology): shows a 9TM topology localized to the plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum (ER), featuring a distinctive domain of unknown function 3735 (DUF3735) domain of unknown function. This structure is proposed to sense cold-induced changes in membrane fluidity. (d) Canonical animal GPCR (7TM topology): serves as a reference, exemplifying the classical 7TM topology with an extracellular N-terminus, intracellular C-terminus, and conserved motifs for G protein coupling, following the traditional five-class classification system[22].

Atypical seven-transmembrane (7TM) candidates

-

G protein-coupled receptor 1 (GCR1), one of the earliest reported 7TM proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana, displays a predicted 7TM topology highly similar to animal GPCRs, featuring a canonical extracellular N-terminus and intracellular C-terminus configuration[16]. Nevertheless, due to low sequence conservation between plant and animal GPCRs, GCR1 likely lacks conserved motifs typical of animal GPCRs—such as the DRY or NPxxY motifs—which are critical for signal transduction and receptor activation in animals. Although physical interaction between GCR1 and GPA1 was reported, direct evidence for its functional significance, particularly GEF activity characteristic of classical GPCRs, remains controversial[13]. Mildew Locus O (MLO) proteins are located in the plasma membrane and have a 7TM structure, matching the structural feature of GPCRs. This similarity led to initial hypotheses that MLO proteins may function as GPCR or GPCR-like proteins. The primary role of MLO proteins involves modulating plant pathogen defense, particularly in regulating susceptibility to powdery mildew[14].

PAQR-like proteins (progesterone and adiponectin receptor-like proteins) represent another significant member of the plant 7TM protein family. These proteins are homologous to human progesterone and adiponectin receptors (PAQRs) and are highly conserved in both monocotyledonous (e.g., rice) and dicotyledonous (e.g., soybean, Arabidopsis) plants. They confer effective resistance against a variety of pathogens, including Botrytis cinerea, Talaromyces versatilis, and Pseudomonas species. Upon pathogen recognition, pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) relay the signal via the adaptor kinase KIN7 to the membrane-localized PAQR-like sensors (PLSs), forming a critical PRR-KIN7-PLS ternary complex that activates downstream immune responses. In contrast to animal GPCRs, which typically adopt an extracellular N-terminus and intracellular C-terminus topology, PLSs exhibit a distinct membrane topology with an N-terminus facing the cytosol. Despite this structural difference, PLSs functionally mimic animal GPCRs by undergoing allosteric changes that confer GEF activity, promoting GDP-to-GTP exchange on the Gα subunit (GPA1) and thereby modulating PTI responses—a process essential for downstream immune signaling[23]. PLSs lack key conserved motifs like DRY and NPxxY. This matches earlier studies on plant GPCR candidates like GCR1. It suggests that PLSs may have developed plant-specific ways to activate G proteins, possibly through unique structural shapes or interactions with partner proteins like KIN7.

Besides these well-studied candidates, several other proteins with predicted 7TM structures have been identified in various plant species. The Pisum sativum GPCR-like protein (PsGPCR) exhibits a 7TM domain topology and mediates responses to salt and heat stress, potentially through interactions with pea G protein subunits[24]. PsGPCR shares approximately 50% amino acid sequence identity with Arabidopsis GCR1, with high conservation in the transmembrane domains. Similarly, Lotus japonicus GCR1 (LjGCR1) is predicted to possess a 7TM topology, localizes to the plasma membrane, and features an extracellular N-terminus and an intracellular C-terminus. LjGCR1 perceives symbiotic signaling molecules, regulating nodule formation and playing a critical role in nitrogen fixation[25]. In Arabidopsis, Cand2, a 7TM protein, localizes to the plasma membrane and interacts with the Gα subunit GPA1[26]. Furthermore, TOM1, a putative GPCR identified in cotton, possesses a predicted 7TM structure and is localized to the plasma membrane[27].

Nine-transmembrane (9TM) candidates

-

Certain plant GPCR candidates exhibit expanded transmembrane (TM) topologies that diverge from the canonical 7TM framework. GTG1 and GTG2 are Arabidopsis proteins localized to the plasma membrane with significant sequence and structural homology. While closely related to the human orphan GPCR GPR89, they possess distinct features that differentiate them from classical GPCRs. Predicted to contain nine transmembrane domains (9TMs), this topology distinguishes GTGs from canonical GPCRs and plant 7TM proteins like GCR1 or PAQR-like sensors (PLSs). The additional transmembrane domains may contribute to unique ligand-binding or signaling properties. The N-termini of GTG1 and GTG2 are predicted to reside extracellularly—consistent with traditional GPCRs where the N-terminus typically serves as a ligand-binding domain—while their C-termini are intracellular. The 9TM structure forms four intracellular loops (ICLs) and four extracellular loops (ECLs) connecting the TM helices. Notably, the third intracellular loop is substantially larger and harbors a degenerate Ras GAP domain[28].

COLD1, identified in rice (Oryza sativa) by Ma et al., is a 9TM protein critical for cold tolerance. Its 9TM topology resembles that of GTG1/GTG2 and differs from the classical 7TM architecture of canonical GPCRs. COLD1 is mainly found in the plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum (ER). This suggests it helps connect extracellular cold detection with intracellular signaling pathways. Unlike GTG1/GTG2, which possess GTP-binding GAP domains, COLD1 lacks confirmed GTPase activity. It interacts with the rice Gα subunit RGA1 to regulate cold stress responses[29], mirroring the GTG-GPA1 interaction observed in Arabidopsis.

The COLD family includes COLD1 and its orthologs across plant species. ZmCOLD1 in maize (Zea mays) exhibits a 9TM topology with an extracellular N-terminus and intracellular C-terminus, localizing to the plasma membrane and ER. It contains conserved RAS-GTPase activity, GTP-binding, and domain of unknown function 3735 (DUF3735) domains. ZmCOLD1 regulates plant height, cold stress tolerance, and ABA signaling, likely functioning as a GTPase-accelerating protein rather than possessing intrinsic GTPase activity—distinguishing it from Arabidopsis GTG1/GTG2[30,31]. Similarly, TaCOLD1 and VaCOLD1 were both predicted to be transmembrane proteins with a 9-transmembrane (9TM) structure. TaCOLD1 encodes a transmembrane protein highly homologous to the rice cold-sensitive gene COLD1[32]. VaCOLD1, a newly identified gene in Vitis amurensis Rupr, enhances cold stress tolerance by interacting with the Gα subunit VaGPA1[33].

In addition to the COLD1 family, other 9TM candidates have been proposed. ShGPCR1, a 9TM domain protein from sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum), localizes to the plasma membrane and exhibits upregulated expression under drought, salt, and cold stress[34]. Although reported to harbor GPCR-like features, its putative GTP-binding domain requires further validation.

-

Plant G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) candidates have key roles in sensing hormones, environmental signals, and other ligands. They interact with G protein complexes to start downstream signal transduction. Unlike animal GPCRs, which mainly use single-ligand recognition and GEF activity, plant GPCR candidates show varied perception mechanisms. These include non-standard conformational changes, GTPase acceleration, and multi-ligand integration. The signal perception mechanisms of plant GPCR candidates will be systematically examined below, classified according to their respective signal types. The key characteristics, ligands, and functions of the major plant GPCR candidates discussed herein are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of plant G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) candidates.

GPCR candidate Species Topology Localization Ligand/signal perception G protein interaction Biological functions Ref. GCR1 A. thaliana 7TM Plasma membrane • Blue light (via unknown photoreceptor)

• ABA (controversial)• Interacts with GPA1

• Putative GEF (controversial)• Blue-light-induced Phe synthesis

• Seed germination

• Stress responses (drought, salt)[13,15,16,25] GTG1/GTG2 A. thaliana 9TM Plasma membrane • ABA (stereoselective) • GPA1 binding inhibits GTPase

• Acts as GAP antagonist• Stomatal closure

• Seed dormancy

• Drought response[28] COLD1 (OsCOLD1) O. sativa 9TM PM + ER • Cold stress (via membrane fluidity changes) • GAP for RGA1 • Chilling tolerance [29] PLS A. thaliana, O. sativa, G. max 7TM Plasma membrane • Pathogen signals (via PRR-KIN7)

• Damage signals (eATP, via P2K1)• Induced GEF activity

• Requires KIN7 adaptor• PTI immunity

• Stomatal defense

•Bacterial/fungal resistance

• MAPK activation

• ROS burst[23] PsGPCR P. sativum 7TM Plasma membrane (inferred) • Salt stress

• Heat stress• Interacts with pea Gα • Salinity/heat tolerance [24] LjGCR1 L. japonicus 7TM (inferred) Plasma membrane • Symbiotic nodulation signals • Interacts with G proteins (inferred) • Root nodule formation [25] ShGPCR1 S. officinarum 9TM (predicted) Plasma membrane • Membrane tension changes: Drought, Salt, Cold • Interacts with G proteins (inferred) • Multi-stress tolerance (drought, salt, cold)

• Activates stress-related genes

• Enhances antioxidant enzyme activity[34] Cand2/Cand7 A. thaliana 7TM (inferred) / • Bacterial AHLs (inferred) • Interacts with GPA1 • Rhizosphere communication

• Root development[45] TOM1 Gossypium spp. 7TM Plasma membrane (inferred) • Drought

• Cold• Interacts with GPA1 (inferred) • Drought/cold stress response [27] MLO O. sativa, A. thaliana, H. Vulgare 7TM Plasma membrane • Powdery mildew pathogens • Likely G protein-independent • Powdery mildew susceptibility [14] ZmCOLD1 Z. mays 9TM (predicted) PM + ER • Cold stress

• ABA signaling (inferred)• Interacts with Gα • Plant height regulation

• Chilling tolerance

• ABA responses[30,31] VaCOLD1 V. amurensis 9TM (predicted) PM + ER • Cold stress • Interacts with VaGPA1 • Cold stress tolerance [33] TaCOLD1 T. aestivum 9TM (predicted) PM + ER • Light signals

• Cold stress (inferred)• Interacts with TaGα-7A • Plant height regulation [32] Topology and localization marked with 'predicted' or 'inferred' are based on bioinformatic predictions or indirect evidence, not direct experimental validation. G protein interactions and ligand perceptions labeled as 'inferred' or 'putative' require further biochemical confirmation. Guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) activity for most plant GPCR candidates remains controversial or unconfirmed. ABA perception

-

ABA stands as a central hormone regulating plant stress responses and development[35−37]. Plant GPCR candidates have emerged as key players in ABA perception, complementing the well-established intracellular PYR/PYL/RCAR receptor system[38,39]. The membrane-localized ABA perception through GTG1/2 represents a rapid and context-specific signaling pathway that directly links extracellular ABA availability to intracellular G protein activation.

The GTG1 and GTG2 proteins are key in plant hormone signaling. They act as plasma membrane-localized receptors for ABA, which is a vital regulator of plant responses to environmental stresses. Characterized by a 9TM topology, GTG1 and GTG2 form a high-affinity ABA-binding pocket within their hydrophobic transmembrane core, enabling precise perception of bioactive (±)-ABA while excluding inactive (−)-ABA isomers. This selective binding is key to controlling drought stress responses, seed germination, and stomatal closure, which are important physiological processes regulated by ABA.

The ABA-binding affinity of GTG1/GTG2 is dynamically regulated by their nucleotide-binding states. In the GDP-bound state, the ABA-binding site is exposed, enhancing affinity, whereas the GTP-bound state occludes the binding site, reducing binding efficiency. Mg2+ plays an essential role in GTG1/GTG2 GTPase activity, as demonstrated by EDTA chelation experiments, which show that Mg2+-dependent GTP hydrolysis drives conformational changes critical for ABA perception. Blocking GTPase activity keeps GTG proteins in a shape that cannot bind ABA, highlighting their role as a key hub for ABA-mediated signaling. Through interactions with the Gα subunit GPA1, GTG1/GTG2 activate downstream Ca2+ signaling and ABA-responsive gene expression, thereby orchestrating stomatal closure under drought stress and maintaining seed dormancy[40].

ABA sensitivity analysis by seed germination assays exhibited that ZmCOLD1 was hypersensitive to ABA, indicating its important role in ABA signaling[31]. The VaCOLD1 gene from Vitis amurensis also enhances cold tolerance in Arabidopsis by indirectly regulating ABA-mediated gene expression[33]. These findings emphasize the involvement of COLD1 homologues in ABA signaling across different plant species.

Intracellular ABA receptors, like the PYR/PYL/RCAR family, have been well studied. Membrane-localized ABA receptors have also been identified, showing an additional mode of ABA perception and expanding knowledge of hormone signaling in plants. In contrast, GCR1, another 7TM protein, has limited evidence for direct ABA binding, as radiolabeling assays have not confirmed its role as an ABA receptor[41]. GCR1 might not work on ABA directly. Instead, GCR1 could contribute to ABA signaling in an indirect way, or it might sense other molecules. Additional details regarding the broader roles of GCR1 will be discussed later.

Environmental signal perception

-

The COLD1 gene family encodes transmembrane proteins that primarily perceive cold-induced alterations in membrane fluidity—a physical signal triggered by low temperatures—in monocots (e.g., rice, maize, wheat, wild sugarcane) and dicots (e.g., grape). Experimental evidence indicates that COLD1 knockout mutants exhibit impaired Ca2+ transients at 4 °C, suggesting OsCOLD1's essential role in cold perception, potentially functioning as a Ca2+ channel or regulator thereof[42]. Overexpression of OsCOLD1jap enhances Ca2+ influx and cold tolerance, supporting its direct involvement in cold sensing. TaCOLD1 in wheat (Triticum aestivum) may perceive light signals or membrane fluidity alterations. qRT-PCR data show light-suppressed expression, though cold-specific ligand perception remains understudied. ShGPCR1, classified as an atypical plant GPCR[34], is postulated to activate via physical changes in the membrane lipid microenvironment induced by cold or osmotic stress—independent of classical soluble ligand binding.

GCR1 in Arabidopsis represents a prominent GPCR candidate. Early studies speculated cytokinin perception by GCR1, but subsequent evidence attributed cytokinin responses to unrelated gene mutations, negating its role as a cytokinin receptor. In the blue light signaling pathway, GCR1 has been identified as a critical transduction component in etiolated seedlings grown in darkness. Specific wavelengths of blue light activate upstream photoreceptors, triggering a conformational change in GCR1. This promotes the transition of the G protein α subunit GPA1 to its GTP-bound state. This cascade upregulates PAL1 gene expression, contributing to phenylpropanoid metabolism, and, in conjunction with PD1, leads to phenylalanine accumulation[43]. Genetic evidence confirms that gcr1 mutants completely lack blue-light-induced phenylalanine synthesis, while in vitro assays demonstrate GTP-bound GPA1 enhances PAL1 activity twofold. Notably, this pathway is strictly confined to dark-adapted seedlings and inactive in light-acclimated plants. GCR1 itself lacks photosensory domains, and its upstream receptor remains unidentified. Additionally, Chakraborty et al.[44] demonstrated through transcriptome analysis and experimental validation that gcr1 and gpa1 mutants exhibit increased sensitivity to ABA-related stresses, with single/double mutants showing enhanced stress tolerance vs wild-type. CAND2 and CAND7, plasma membrane-localized 7TM GPCR candidates in Arabidopsis, promote root growth by perceiving bacterially derived N-acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs) in the rhizosphere. CAND2 may function as a GEF through GPA1 interaction, facilitating Gα-GTP formation to activate downstream Ca2+ signaling and hormone-related genes. However, direct AHL binding requires in vitro validation[45]. CAND7 is hypothesized to perceive AHLs analogously based on sequence/structure homology with CAND2, though ligand specificity and signaling mechanisms warrant further study.

Phosphorylation site proteins (PLSs) belong to the plant-specific family of PAQR-like sensors. Within the plant immune signaling network, PLSs function as structurally unique 7TM receptors. Even though they do not have a standard ligand-binding domain, they act as the main centers for transmembrane signal transduction. They connect receptor kinases to downstream parts through protein interaction networks. PLSs cannot autonomously recognize extracellular stimuli such as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or damage signals; instead, PLSs rely on other receptors for signal relay. Their functional implementation depends on a dual-track perception mechanism: their conserved 7TM domains facilitate transmembrane signal transduction, converting extracellular stimuli into intracellular responses. Specifically, (1) PLSs directly bind the kinase domain (KD) of the extracellular ATP receptor P2K1 via their intracellular N-terminal domain, forming a molecular complex to respond to damage signals; and (2) upon recognition of pathogen-derived molecules by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), PLSs undergo induced autophosphorylation.

PLSs directly interact with the kinase domain of the extracellular ATP receptor P2K1, assembling a molecular complex responsive to damage signals. In plant damage and immune responses, extracellular ATP (eATP) acts as a key danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMP). The core mechanism of eATP recognition and transduction centers on the receptor kinase P2K1. When plant cells experience mechanical damage or pathogen attack, intracellular ATP is released into the extracellular milieu. Elevated eATP concentrations trigger conformational changes in the ligand-binding domain of P2K1[46]. Activated P2K1 then initiates early defense responses through its intracellular kinase domain (KD). Crucially, this study identifies PLSs as direct downstream effectors of P2K1. The N-terminal cytoplasmic domain of PLSs specifically binds P2K1-KD, forming a stable P2K1-PLSs signaling complex. Under eATP stimulation, alterations in the phosphorylation status of P2K1 induce allosteric activation of PLSs. At the same time, the kinase KIN7 acts as a key adaptor. It directly binds to phosphorylated PRRs and also connects with PLSs using its kinase domain (KD). This forms a PRR-KIN7-PLS ternary complex. Following upstream signal perception, PLSs undergo conformational rearrangement. This activates their intrinsic GEF activity, catalyzing GDP/GTP exchange on the Gα subunit (GPA1). The activated G protein rapidly dissociates into GTP-bound Gα (Gα-GTP) and the Gβγ dimer, triggering a triple defense cascade comprising mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphorylation pathways, reactive oxygen species (ROS) burst, and stomatal closure defense[23].

Perception of additional ligands

-

In addition to well-studied plant GPCR candidates, several less-explored but significant proteins contribute to the diverse ligand perception in plants. PsGPCR, a 7TM protein in Pisum sativum, perceives salt and heat stress signals, coordinating with phospholipase C to regulate stress responses. Similarly, LjGCR1 in Lotus japonicus, also featuring a 7TM topology, senses symbiotic nodulation signals to promote root nodule formation and nitrogen fixation. MLO proteins, characterized by a 7TM-like structure, are thought to modulate susceptibility to powdery mildew through a G protein-independent pathway, diverging from canonical GPCRs.

Plant GPCR candidates exhibit remarkable mechanistic diversity in signal perception, contrasting with the single-ligand GEF paradigm of animal GPCRs. Multiligand integration capacity represents a hallmark feature: GTG1/GTG2 integrates ABA with potential environmental cues. While PLSs catalyze GDP/GTP exchange on GPA1 through GEF activity—resembling animal GPCR mechanisms—this process strictly depends on the PRR-KIN7-PLS complex. By contrast, animal GPCRs typically target single ligands, whereas plant GPCRs integrate multiple environmental signals. This capacity for multiligand sensing enables plants to adapt to complex ecological niches. It therefore demonstrates an expanded functional repertoire for GPCRs and elucidates a key molecular mechanism for environmental adaptation.

-

In plant cell signaling, the core paradigm involves extracellular signal perception by 7TM receptors and subsequent activation of heterotrimeric G proteins (comprising Gα, Gβ, and Gγ subunits). Unlike the standard 'rigid trimer dissociation' model common in animal systems, where ligand binding triggers receptor conformational changes and Gαβγ separation, plant GPCRs or their functional equivalents show high plasticity and diverse mechanisms (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparative analysis of animal and plant G protein-coupled receptors.

Feature Animal GPCRs Plant GPCR candidates Ref. Canonical topology • 7TM domains

• Extracellular N-terminus

• Intracellular C-terminus

• Conserved across speciesDiverse architectures:

• 7TM (GCR1, PLS, PsGPCR, LjGCR1, Cand2, TOM1)

• 9TM (GTG1/2, COLD1,ZmCOLD1, ShGPCR1)

• Atypical orientation: Cytosolic N-terminus (PLS)[12,18,19,21,23−25,31,34] Sequence homology High conservation

• DRY motif

• NPxxY motifLow/no homology

• Absence of DRY/NPxxY motifs

• Limited similarity to animal GPCRs[2,18] Ligand perception Single-ligand focused

• Hormones, neurotransmitters

• Direct binding via N-terminusMultiligand integration

• GTG1/2: ABA + environmental cues

• PLS: Pathogens + damage signals via PRR-KIN7 complex

• ShGPCR1: Cold/salt/osmotic stress via membrane tension[14,22,23,28,34] Binding mechanisms Direct ligand binding

• Stereospecific pockets

• Ligand-induced conformational changesDiverse mechanisms:

• Hydrophobic pockets (GTG1/2)

• Membrane fluidity sensing (COLD1, ShGPCR1)

• Indirect relay (PLS: requires PRR/KIN7)

• GTP-state modulation (GTG1/2: GDP-bound state enhances ABA affinity)[14,19,23,28,29,34] GEF activity Definitive GEF function

• Catalyzes GDP→GTP exchange on Gα

• Triggers Gαβγ dissociationControversial/atypical:

• PLS: Induced GEF activity in PRR-KIN7 complex

• GCR1: Putative GEF (no direct evidence)

• Absent in GTG/COLD families[12,18,19,23,28,29] G protein regulation Classical cycle:

1. GPCR-GEF activates Gα

2. Gα-GTP dissociates from Gβγ

3. GTP hydrolysis resets systemDiverse mechanisms:

• GAP activity (COLD1: accelerates GTP hydrolysis)

• GTPase antagonism (GTG1/2: GPA1 inhibits GTPase)

• Direct effector modulation (Gβγ regulates Ca2+ channels independently)

• Kinase-dependent (PLS: requires P2K1/KIN7 phosphorylation)[14,21,28,29] Key domains • Ligand-binding domains

• G-protein coupling domainsNovel domains:

• RasGAP domain (GTG1/2)

• DUF3735 (ZmCOLD1)

• GTP-binding domains (ShGPCR1, GTG1/2)[14,19,28,33,34] Subcellular localization Plasma membrane Dual localization:

• Plasma membrane + ER (COLD1, ZmCOLD1)

• Plasma membrane mostly (others)[13,21,28,29,33] Signaling cascades • cAMP/PKA

• Ca2+ mobilization

• MAPK activationPlant-specific pathways:

• Ca2+ signaling hubs (COLD1, ShGPCR1)

• MAPK immunity cascade (PLS)

• Transcriptional networks (GCR1, GTG1/2)[13,19,21,23,28,34,42] Evolutionary innovations Conserved 7TM architecture Structural innovations:

• 9TM topology (GTG/COLD families)

• Cytosolic N-terminus (PLS)

• Functional domain fusion (COLD1: ER localization + Ca2+ regulation)

• Mechanosensing (ShGPCR1: membrane tension transduction)[19,21,23,28,29,34] Controversies Well-established paradigm Ongoing debates:

• Existence of bona fide GPCRs in plants

• GCR1/GCR2 classification (GCR2 reclassified as LanC-like protein)

• GPA1 self-activation vs. GPCR-dependence[2,17,18] The primary function of plant receptors is to regulate the nucleotide state of the Gα subunit, switching between an inactive GDP-bound state and an active GTP-bound state. Specifically, upon ligand recognition, these receptors primarily act as GEF, catalyzing GDP release from the Gα subunit and facilitating GTP binding. GTP-bound Gα typically dissociates from the Gβγ dimer, enabling both components to independently activate downstream effectors, ultimately eliciting specific physiological responses. The following section delineates the G protein activation modes of key plant GPCR candidates.

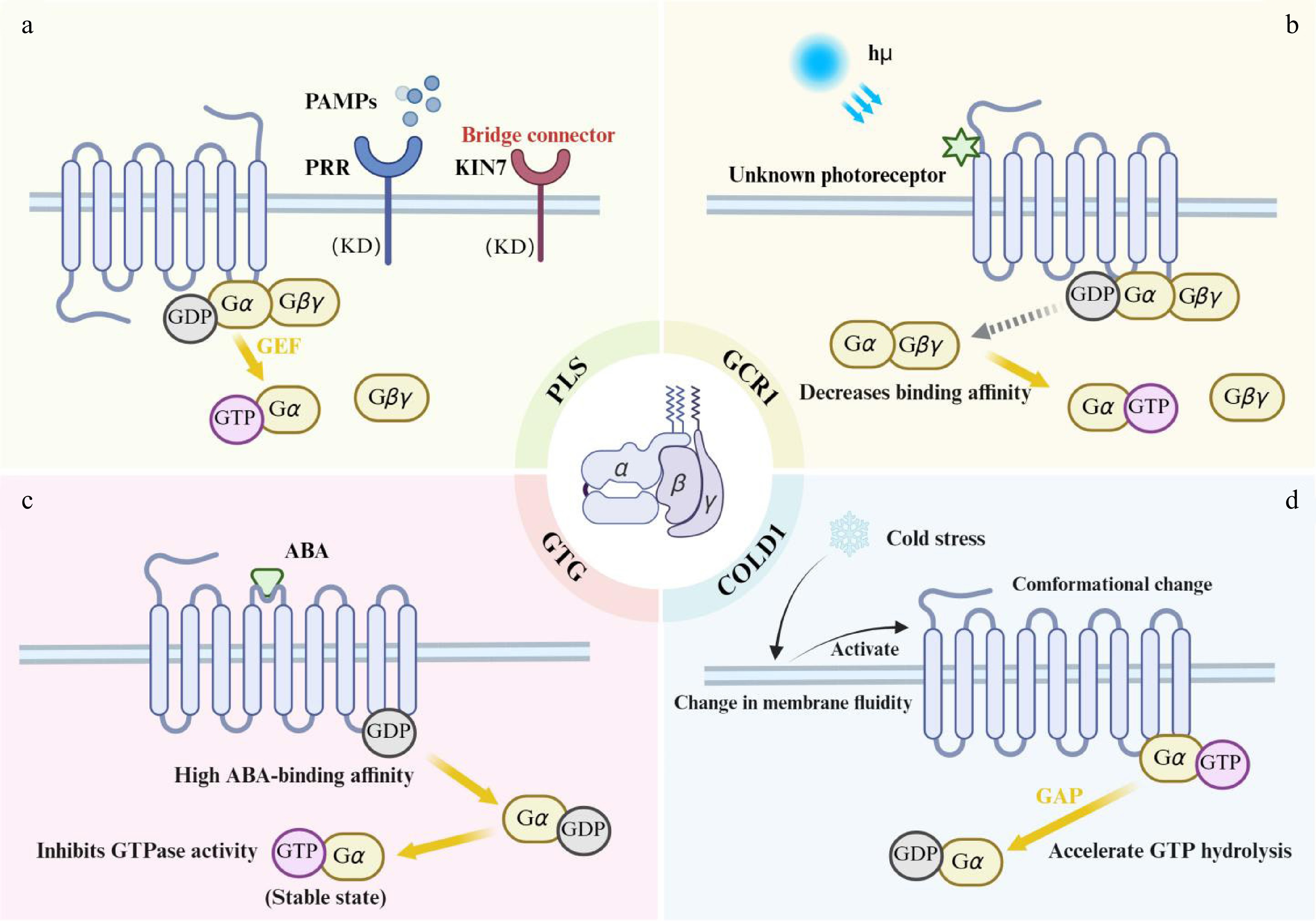

PLSs, representing plant-specific GPCR-like proteins, employ a dual-track mechanism for pathogen signal perception: an indirect pathway mediated by the adaptor kinase KIN7, bridging pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), and a direct pathway wherein PLSs' intracellular domain interacts with the cytosolic domain of the extracellular ATP receptor P2K1. Regardless of the pathway, ligand binding induces conformational changes in PLSs that confer classical GEF activity: direct binding to GDP-bound Gα promotes GDP release and GTP binding, triggering dissociation of GTP-bound Gα from Gβγ[47]. GCR1 directly perceives signals such as blue light or ABA[43]. Its activation mechanism involves non-canonical GEF functionality: GCR1's intracellular domain binds the GDP-bound state of GPA1. Conformational changes in GCR1 reduce Gα's affinity for GDP, facilitating GDP release. Acting as a GEF, GCR1 accelerates GTP binding to Gα's nucleotide-binding pocket. GTP binding triggers a conformational change in the Gα subunit. This breaks the Gα-Gβγ connection and causes the heterotrimer to separate.

Unlike the mechanism of GCR1, which directly promotes GTP binding, members of the GTG protein family operate through a fundamentally distinct regulatory logic. GTG itself functions both as an ABA receptor and possesses intrinsic GTPase activity, representing a mechanism divergent from the aforementioned receptors. Crucially, GTG protein exhibits higher affinity for ABA in its GDP-bound state. When GPA1 binds to GDP-bound GTG, it does not activate GEF activity but rather inhibits the intrinsic GTPase activity of GTG, thereby acting as a GAP antagonist. This inhibition keeps GTG in its active, GTP-bound state. This creates a unique ABA signaling pathway that works in the opposite way of the standard GEF pathway, because it stabilizes the Gα-GTP state instead of promoting its dissociation. Cold stress activates the rice COLD1 protein by altering plasma membrane fluidity. COLD1 has been identified as a GAP that significantly accelerates the GTP hydrolysis rate of the rice Gα subunit RGA1. ShGPCR1, which responds to multiple stresses including drought, salt, and cold, potentially interacts with G proteins via its GTP-binding domain to activate downstream signaling. However, direct experimental evidence confirming physical interaction between ShGPCR1 and specific G protein subunits, or its capacity to directly regulate GTP/GDP exchange, is currently lacking.

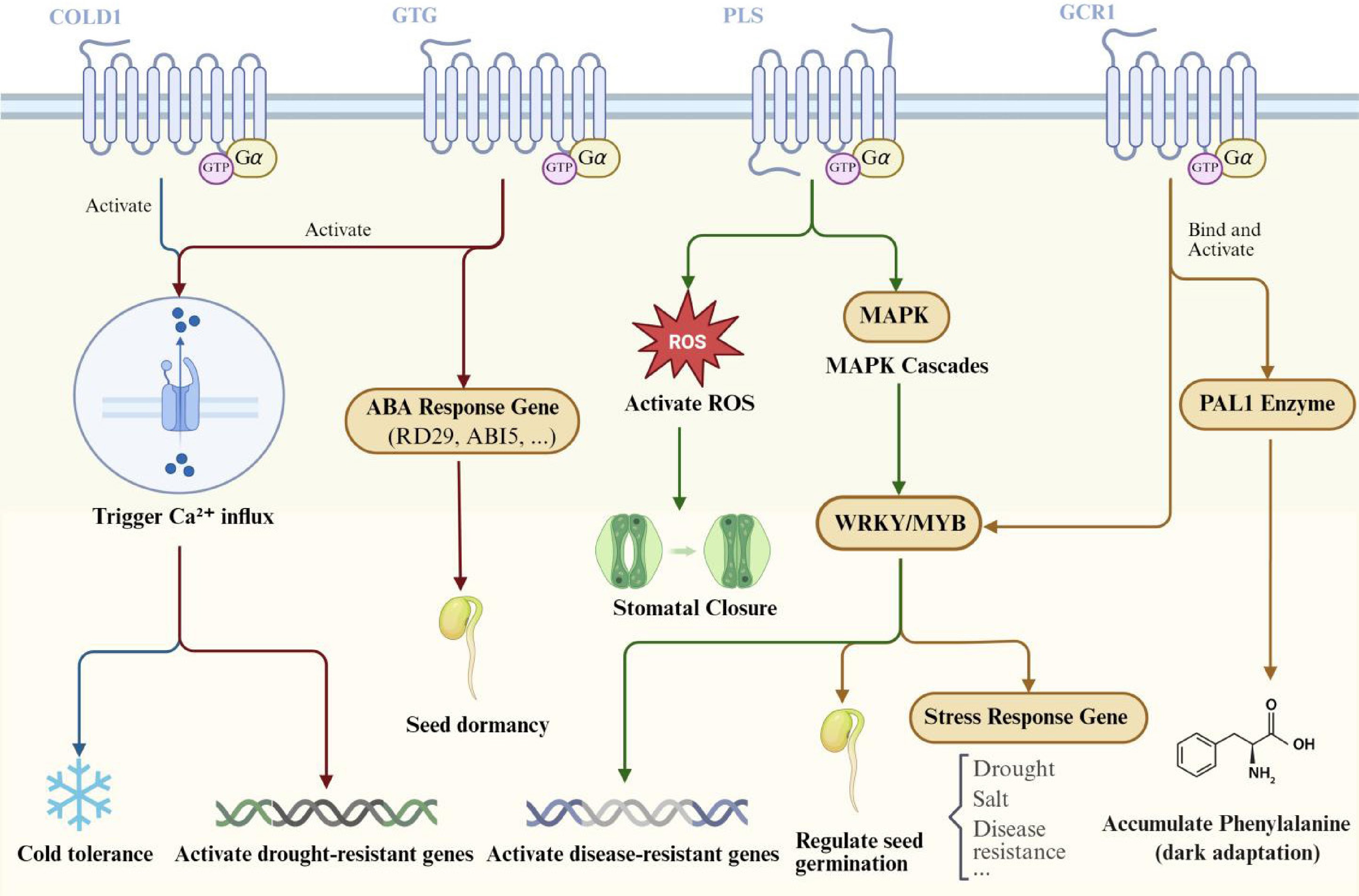

The receptor systems that control plant G protein signaling have evolved a very distinct structure compared to those in animals, and this is the result of adaptive evolution. Plant G protein regulation encompasses not only canonical GEF pathways but also evolved mechanisms involving GAP antagonism and direct GAP activity (Fig. 2). In plants, the activation of heterotrimeric G proteins by GPCR-like proteins after sensing external signals is not the end, but rather the start of complex signaling cascades. These pathways then regulate multi-layered effector networks, which include calcium signaling hubs, MAPK cascade amplification systems, and transcription factor regulatory networks. Ultimately, these networks coordinate key physiological functions that allow plants to respond to environmental stresses and control growth and development. (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

G protein regulatory mechanisms of plant atypical GPCRs. (a) PLS (PAQR-like sensor): pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are perceived by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). This leads to the formation of a PRR-KIN7-PLS ternary complex, which activates the guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) activity of PLS. Activated PLS catalyzes GDP/GTP exchange on the Gα subunit. (b) GCR1: blue light activates GCR1 via an unidentified photoreceptor. The intracellular domain of activated GCR1 binds to GDP-bound Gα, reducing Gα's affinity for GDP and promoting GDP release. (c) GTG1/2: ABA binds stereoselectively to the high-affinity GDP-bound state of GTG. This triggers GPA1 binding, which inhibits the GTPase activity of GTG, thereby stabilizing the GTP-bound GTG state. (d) COLD1: cold stress increases membrane lipid rigidity, inducing a conformational change in COLD1. Acting as a GAP, COLD1 binds to GTP-bound Gα and accelerates GTP hydrolysis, rapidly generating GDP-bound Gα.

Figure 3.

Plant GPCR signaling pathways and their roles in environmental adaptation and developmental regulation. This schematic model delineates the downstream signaling pathways and associated physiological functions mediated by plant GPCRs, as detailed in the main text. COLD1-mediated cold sensing: cold stress induces membrane rigidification, leading to COLD1 activation. COLD1 functions as a GAP for RGA1 (Gα), accelerating GTP hydrolysis. This activation subsequently triggers Ca2+ influx, ultimately enhancing chilling tolerance. GTG1/2-mediated ABA Signaling: ABA binding to the GDP-bound state of GTG1/2 recruits GPA1 (Gα) and inhibits its GTPase activity, thereby stabilizing the active GTG-GTP state. This pathway regulates two primary outputs: (1) activation of plasma membrane Ca2+ channels and induction of drought-tolerance gene expression, and (2) activation of ABA-responsive genes to promote seed dormancy. PLS-mediated Immunity: Upon perception of pathogens by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) or damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) receptors, the adaptor protein KIN7 is activated, initiating the PLS signaling pathway. PLS exhibits guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) activity towards GPA1 (Gα), promoting GDP/GTP exchange. The activated G protein triggers a defense cascade comprising: a reactive oxygen species (ROS) burst, promotion of stomatal closure, and activation of a MAPK cascade, which in turn activates WRKY transcription factors to induce disease-resistance gene expression. GCR1-mediated Signaling: Activated by an unidentified blue light photoreceptor, GCR1 facilitates GTP loading of GPA1 (Gα). This process directly stimulates phenylalanine ammonia-lyase 1 (PAL1) enzyme activity, promoting phenylalanine synthesis. In parallel, the activated G protein regulates transcription factors such as WRKY to modulate seed germination and stress-responsive gene expression.

Calcium ion signaling hubs

-

Under cold stress, COLD1 functions as a GAP. Through physical interaction, COLD1 accelerates GTP hydrolysis by Gα (RGA1), thereby activating downstream signaling pathways. This process triggers the opening of Ca2+ channels, mediating extracellular Ca2+ influx. This leads to a rapid increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and the generation of a specific signal, consequently enhancing plant cold tolerance[48]. Under drought/salt stress, ShGPCR1 significantly elevates intracellular Ca2+ concentration via a GTP-dependent pathway. This activates the expression of osmoprotective genes such as LEA and DHY, thereby enhancing stress tolerance[49]. Although the specific details of its Ca2+ signaling pathway remain incompletely defined, it is hypothesized that this receptor, localized to the plasma membrane, induces Ca2+ influx, subsequently initiating downstream stress responses. Notably, plant G protein signaling exhibits a unique regulatory dimension: the Gβγ dimer can directly modulate calcium channels independently of Gα. For instance, the COLD1-Gβγ complex can directly act on calcium channels, altering their conformation and modulating Ca2+ influx. This mechanism stands in marked contrast to the strict control of animal Gβγ activity by Gα.

MAPK cascade signal amplifier

-

In plant immune responses, PLS modulates immune signaling by activating heterotrimeric G proteins. The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade represents one of the key signaling pathways downstream of PLS. Studies show that pls mutants have much lower MAPK phosphorylation levels after they are induced by different immune elicitors. For instance, MAPK phosphorylation is markedly impaired in pls single and multiple mutants compared to wild-type plants after treatment with ATP, flg22, or chitin. Further genetic evidence reveals that the immune function of PLSs relies on the G protein α subunit GPA1. Overexpression of GPA1 enhances PAMP-induced MAPK activation; however, this enhancement is suppressed in pls mutants. The GEF activity of PLS, after it activates GPA1, affects downstream MAPK activation. Upon ligand activation, PLS promotes GTP loading of GPA1 via its GEF activity, thereby activating the MAPK signaling pathway. This activation mechanism is crucial for plant defense against diverse pathogens.

Transcriptional factor network regulation

-

Following perception of blue light, hormones, or stress signals, GCR1 interacts with the heterotrimeric G protein α subunit GPA1, promoting GDP/GTP exchange. This leads to G protein dissociation into GTP-bound Gα and the Gβγ dimer. The activated G protein subunits subsequently regulate downstream effectors. The GCR1/GPA1 signal controls the expression of genes that respond to blue light, stress (like cold, heat, salt, or drought), and hormones. It does this by activating transcription factors like WRKY, MYB, bHLH, and C2H2. This regulatory network mediates processes including seed germination and stomatal movement[50]. In ABA responses, GTG1/2 triggers downstream transcriptional reprogramming through conformation-dependent ABA perception and interaction with GPA1, thereby enhancing stress tolerance.

-

The evolution of plant GPCR research represents a paradigm shift in our understanding, transforming the apparent 'disappearance' of the canonical animal-type 7TM receptors from plants from a theoretical challenge into a recognition of remarkable evolutionary adaptation[51]. Rather than simply losing the canonical GPCR paradigm, plants have evolved sensory networks of greater complexity through multiple innovative strategies: transmembrane topology remodeling, as exemplified by the 9TM structure of GTGs forming a specialized ABA-binding pocket; functional domain fusion, illustrated by COLD1's ER localization coupled with calcium signaling regulation; and the subversion of canonical signaling logic, evident in PLSs that rely on the adapter KIN7 to interface with immune receptors. This evolutionary innovation is likely driven by the sessile nature of plants, which necessitates the precise translation of diverse environmental cues into molecular decisions.

These sophisticated signaling mechanisms not only reveal fundamental biological principles but also offer compelling prospects for biotechnological applications. For instance, the inducible, complex-dependent nature of the PRR-KIN7-PLS module provides a blueprint for engineering synthetic immune receptors capable of conferring broad-spectrum disease resistance. Similarly, the unique nucleotide-sensing property and ABA perception mechanism of GTG1/2 present a target for fine-tuning ABA signaling dynamics, offering a potential strategy for enhancing drought tolerance in crops without compromising yield. Furthermore, the mechanosensory functions of receptors like COLD1 and ShGPCR1, which directly translate physical membrane properties into calcium-mediated signaling, could be harnessed to develop smart crops that preemptively activate tailored stress responses upon perceiving specific environmental changes such as cold or soil drying. The conservation of these core mechanisms across species underscores their fundamental role and enhances the translatability of engineering strategies from model systems to agriculturally important crops, opening new avenues for developing climate-resilient agriculture.

Perhaps the most significant gap in current research concerns the boundaries of signaling pathway conservation across species. The striking finding that human adiponectin receptor AdipoR1 can functionally compensate for immune defects in Arabidopsis pls mutants suggests that core regulatory logic within the PAQR family has been conserved over hundreds of millions of years of evolution. This implies the existence of universal molecular interfaces within nature's signal transduction systems, offering novel paradigms for engineering stress-resistant crops. Furthermore, the mechanosensory module of sugarcane ShGPCR1 holds particular promise. Its 9TM domain functions as an intrinsic 'biomechanical sensor', directly transducing membrane tension changes into calcium signal activation. By fusing these structural domains with stress-sensing modules from other plant species, it may be possible to engineer synthetic receptors that integrate multiple environmental signals. Such receptors could simultaneously detect and initiate coordinated responses to diverse stresses, providing a robust tool for developing crops with enhanced resilience.

Looking forward, unraveling the enduring mysteries of plant GPCR activation and their dynamics in living tissues will require harnessing a suite of emerging technologies. A deeper functional dissection calls for advanced CRISPR-mediated genome editing strategies that go beyond simple gene knockouts, enabling the creation of precise allelic series and targeted edits in regulatory elements to fine-tune signaling outputs. To directly address long-standing debates over GEF/GAP activities, the field would greatly benefit from the development of FRET/FLIM-based biosensors that can visually track G protein activation dynamics in real time within living plants. Furthermore, a definitive mechanistic understanding at the atomic scale will likely come from the application of cryo-electron microscopy, capable of resolving the intricate structures of these atypical receptors in complex with their G protein partners. The integration of these multidisciplinary approaches—spanning genetics, live-cell imaging, and structural biology—will be essential to transition the field from observational discovery to predictive modeling and the rational engineering of plant stress resilience, paving the way for transformative applications.

This paves the way for a comprehensive understanding of plant GPCR signaling—from molecular mechanisms to physiological functions, and from evolutionary innovations to crop improvement. A new era, driven by interdisciplinary technologies, is dawning, promising profound transformations for both fundamental plant biology and sustainable agriculture.

This work is financially supported by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. LR24C200004), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 32272776, 32572643), Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 2025C01093), Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST (Grant No. 2022QNRC001).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: literature collection: Zhu Q; draft manuscript preparation: Zhu Q; manuscript revision: El-Yazied AA, Ibrahim MFM, Luo Z, Xu Y; supervision: El-Yazied AA, Ibrahim MFM, Luo Z, Xu Y; material retrieval: Zhang H, Wang J, Liang B, Li Y, Ma X, Gu W, Wang S, Nian J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets are generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

Although authors Huawei Zhang, Benlei Liang, and Yanping Li are employees of Hefei Midea Refrigerator Co., Ltd; author Jiahua Wang is an employee of Ningbo Fotile Kitchen Ware Co., Ltd; authors Xiangyan Ma and Weizhi Gu are employees of Xinjiang SF Express Co., Ltd; author Shikui Wang is an employee of CIMC Cold Chain Research Institute Co., Ltd; and author Junlai Nian is an employee of Qingdao CIMC Special Reefer Co., Ltd, the work presented in this article constitutes independent academic research, unrelated to the commercial interests of these companies. The authors affirm that no financial or contractual agreements between the companies and the authors or their institutions have influenced the design, outcomes, or reporting of this study.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Chongqing University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu Q, Luo Z, El-Yazied AA, Ibrahim MFM, Zhang H, et al. 2025. Hormones perception and signaling transduction by plant GPCR-like receptors. Plant Hormones 1: e027 doi: 10.48130/ph-0025-0027

Hormones perception and signaling transduction by plant GPCR-like receptors

- Received: 27 August 2025

- Revised: 15 October 2025

- Accepted: 30 October 2025

- Published online: 15 December 2025

Abstract: Plant G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) exhibit unique structural and functional traits that diverge from the canonical animal GPCR paradigm. This review synthesizes current understanding of plant GPCRs, focusing on their atypical seven-transmembrane (7TM) and nine-transmembrane (9TM) architectures and diverse signaling mechanisms. Unlike animal GPCRs, plant candidates such as GCR1, GTG1/2, and COLD1 show low sequence homology and lack conserved motifs, yet mediate critical hormone and environmental signaling. GCR1, with a 7TM topology, potentially regulates blue-light via non-canonical interactions with Gα subunit GPA1, although its guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) activity remains debated. GTG1/2, featuring 9TM structures, form high-affinity abscisic acid (ABA)-binding pockets, modulating drought and seed germination through Mg2+-dependent GTPase activity. COLD1 perceives cold-induced membrane fluidity changes, accelerating Gα GTP hydrolysis to trigger Ca2+ signaling. PAQR-like sensors (PLSs) integrate pathogen signals via the PRR-KIN7-PLS complex, activating mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades and immunity. Plant GPCRs' multiligand perception adapts them to complex environments, contrasting with animal GPCRs' single-ligand focus. Additionally, the central role of ABA perception through atypical GPCRs such as GTG1/2, is emphasized, which not only redefines hormone receptor paradigms but also bridges hormone signaling with environmental stress responses.