-

A typical flower comprises four whorls of organs: sepal, petal, stamen, and pistil. Based on the floral quartet model (FQM), the identities of these floral organs are determined by various combinations of the ABCDE-class MADS-box proteins that function in overlapping domains within the flower[1]. The proliferation of the ABCDE genes in modern flowering plants is strongly correlated with the evolution and diversification of floral patterns, as exemplified by the independent duplication of B-class genes that led to petal derivation in the Orchid and Liliaceae families[2].

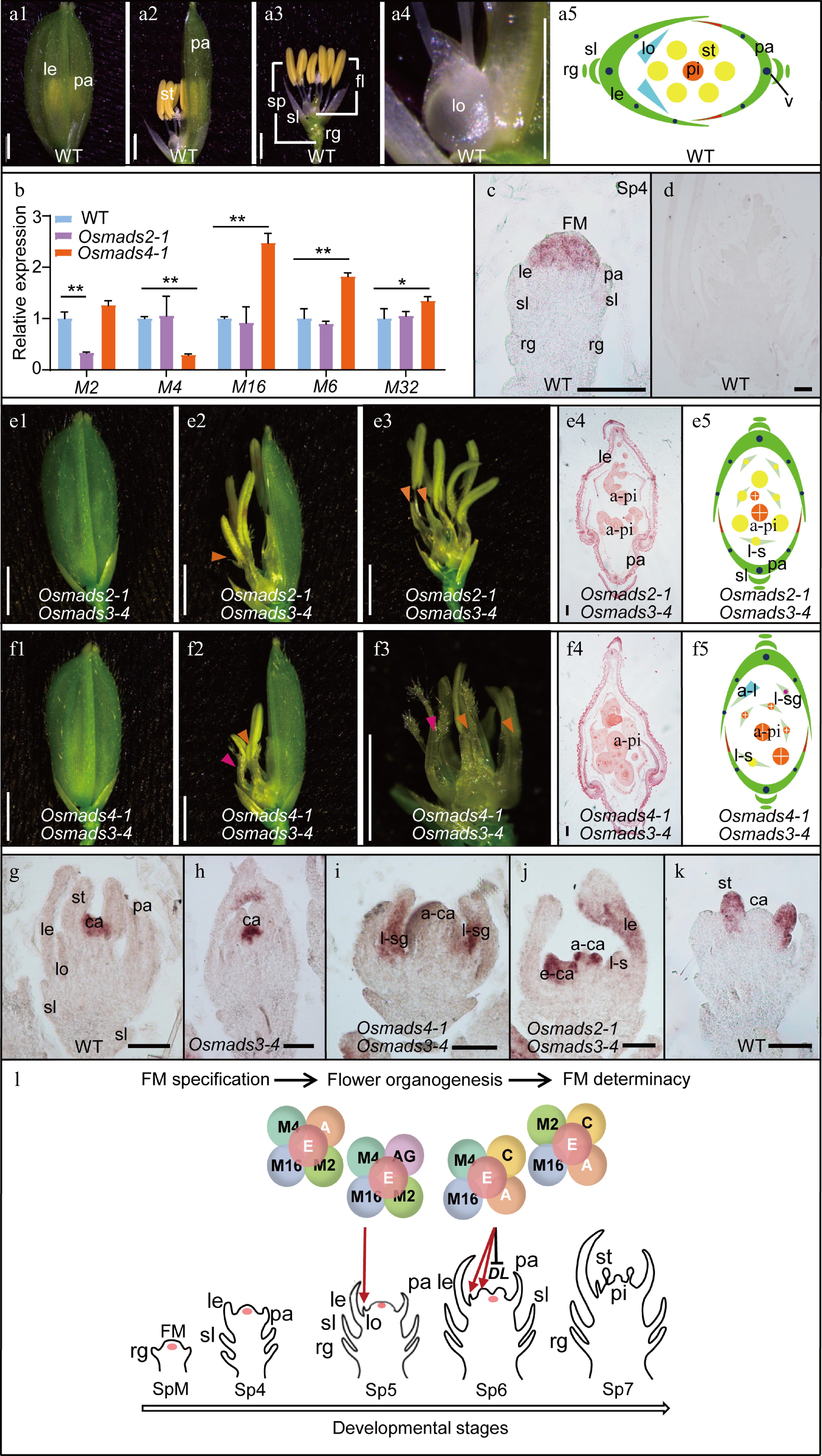

Spikelet, the unique flower structure of grass inflorescence, contains highly specialized non-reproductive organs[3]. In rice for example, each spikelet comprises two pairs of bract-like organs and a floret that consists of lemma and palea in the first whorl, two lodicules that are generally regarded as petal equivalent in the second whorl[4], six stamens in the third whorl, and one pistil in the center whorl (Fig. 1a). OsMADS14, OsMADS15, OsMADS18, and OsMADS20 are A-class genes that regulate palea development. OsMADS2, OsMADS4, and OsMADS16 are B-class genes that act together with the A-class genes to determine lodicule development. OsMADS3 and OsMADS58 are C-class genes that act in combination with the B-class genes to control stamen formation. OsMADS13 and OsMADS21 are D-class genes that function together with the C-class genes to regulate ovule formation and development. OsMADS1, OsMADS5, OsMADS7, OsMADS8, and OsMADS34 are rice SEP-like (E-class) genes, serving as the 'glume' genes that participate in all floral organ development processes by interacting with proteins from the other classes to specify floral organ identity and determinacy[5]. Additionally, OsMADS6 and OsMADS17 are AGAMOUS-LIKE6 (AGL6) homologs with similar function to the E-class proteins, whereby OsMADS6 is known to control floral meristem (FM) and floral determinacies[6]. OsMADS32, an orphan protein in monocotyledonous plants, regulates floral context by interacting with other floral homeotic proteins[7]. However, to what extent the FQM can be applied to the development of the non-reproductive organs in the spikelet is still largely unclear.

Figure 1.

OsMADS2 and OsMADS4 play partially distinct roles in lodicule and stamen specification. (a) Spikelet morphology (a1−a4) and cartoon diagram (a5) of Wild Type (WT). (b) Expression level of the B-class genes (OsMADS2, OsMADS4 and OsMADS16), OsMADS6 and OsMADS32 in the 2-mm inflorescence of WT, Osmads2-1 and Osmads4-1. Results are shown as mean ± SD. Error bars indicate SD for three biological replicates. ** indicates p-values < 0.01, * indicates P-values between 0.05 to 0.01, analyzed by Student-t test. (c), (d) In-situ hybridization analysis of OsMADS4. In the WT, signals for the anti-sense probe were detected in FM (c), whereas no signals for the sense probe were detected (d). Spikelet morphology (1−3), transverse section (4) and cartoon diagram (5) of the (e) Osmads2-1 Osmads3-4 and (f) Osmads4-1 Osmads3-4 double mutants. (g)−(j) In-situ hybridization analysis of DL in WT, Osmads3-4, Osmads4-1 Osmads3-4 and Osmads2-1 Osmads3-4, respectively. (k) In-situ hybridization analysis of OsMADS4 in WT. (l) A working model of the function of OsMADS2 and OsMADS4 in regulating rice flower development. OsMADS2 and OsMADS4 may engage with different protein complexes in specifying lodicule and stamen identity and morphogenesis. To specify lodicule identity, OsMADS2 and OsMADS4 play partially redundant roles in forming a complex with OsMADS16, the A-class proteins, AGL6-like proteins, and/or E-class proteins. OsMADS2 plays an additional role in regulating lodicule morphogenesis. On the other hand, OsMADS4 may form a protein complex with OsMADS16, and C-, A- and E-class proteins to determine stamen identity. OsMADS4 has a specific role in inhibiting the expression of DL in the lodicule and stamen to specify their identity and morphogenesis. Orange arrowheads in (e) and (f) indicate lodicule-stamen mosaic organs; Rose arrowheads in (e) indicate lodicule-stigma mosaic organ. a-ca, abnormal carpel; a-pi, abnormal pistil; e-ca, ectopic carpel; fl, floret; FM, floral meristem; le, lemma; lo, lodicule; l-s, lodicule-stamen mosaic organ; l-sg, lodicule-stigma mosaic organ; pa, palea; pi, pistil; rg, rudimentary glume; sl, sterile lemma; sp, spikelet; st, stamen. Scale bars = 2 mm in a1 to a4, e1 to e3 and f1 to f3; scale bars = 100 μm in e4 and f4; and scale bars = 50 μm in g to k. Red arrows in l indicate positive regulation in flower organ identity specification. The black bar in l indicates negative regulation. A, A-class proteins; AG, AGL6-like proteins; C, C-class protein; E, E-class proteins; SpM, spikelet meristem. M is the abbreviation of OsMADS; DL, DROOPING LEAF. Sp refers to a developmental stage of rice spikelet.

Plant genomes contain two main lineages of B-class genes, PI/GLO and paleoAP3/DEF, which arose before the emergence of angiosperms. In rice, OsMADS2 and OsMADS4 are paralogs in the PI/GLO family that play the same role as the paleoAP3/DEF ortholog, OsMADS16 (also named as SUPERWOMAN1), in specifying lodicule and stamen[8]. However, previous studies of OsMADS2 and OsMADS4 RNAi plants indicated that these two genes play unequal roles in lodicule morphogenesis[9]. Whether they function differentially in floral meristem (FM) activity and floral organ development remains elusive.

To further distinguish the function between OsMADS2 and OsMADS4, the CRISPR-Cas9 system was used to generate targeted mutations within the two genes to obtain strong mutant alleles. Two mutational events were identified for OsMADS2 : Osmads2-1 has an 'A' insertion and Osmads2-2 has a 'TT' insertion (Supplemental Fig. S1a), both causing a frameshift and premature translational termination of the protein (Supplemental Fig. S1b). Compared with the wild-type (WT) plant, there was no visible abnormal phenotype from the vegetative to the reproductive stage, except that the lodicules were extended during floret development in both alleles (Supplemental Fig. S2), which is consistent with a previous report[9]. For OsMADS4, two types of mutants were obtained: Osmads4-1 has a deletion of 'T' and Osmads4-2 has an insertion of 'T' (Supplemental Fig. S3a), both leading to a frameshift and premature translational termination of the protein as well (Supplemental Fig. S3b). Compared with the WT plant, both Osmads4-1 and Osmads4-2 displayed normal vegetative and reproductive growth and the floret contained normal lodicules and stamens (Supplemental Fig. S5), which is also consistent with the previously reported phenotypes of the OsMADS4 RNAi plant[9].

Double mutants were then generated by crossing Osmads2-1 with Osmads4-1. Abnormal spikelet phenotypes were observed in the double mutant that mimicked Osmads16/spw1-1[5], in which the lodicules were transformed into margin region of palea (mrp)-like organs and stamens into carpel-like organs (Supplemental Fig. S6). Interestingly, enlarged ovaries appeared in the inner whorl of Osmads2-1 Osmads4-1 (Supplemental Fig. S6c). Therefore, the genetic analysis supports results from the previous study that OsMADS2 and OsMADS4 are functionally redundant with an essential role in determining the identities of lodicules and stamens, while OsMADS2 also has a distinct role in lodicule morphogenesis[9]. RT-qPCR analysis of the expression of OsMADS2, OsMADS4 and OsMADS16 in the mutant lines revealed that, although OsMADS2 and OsMADS4 did not seem to impact each other's expression, the expression of OsMADS16 increased significantly in the Osmads4-1 mutant (Fig. 1b; Supplemental Fig. S7), suggesting that OsMADS16 might compensate for the loss of OsMADS4 through transcriptional upregulation.

A previous study showed that OsMADS6 (AGL6-like gene) and OsMADS3 (C-class gene) are also involved in determining floral organ identities and meristem fate[10]. To determine whether these genes interact genetically with OsMADS2 and OsMADS4, double and triple mutants between Osmads6-1, Osmads3-4 and Osmads2-1 and Osmads4-1 were generated. The spikelet of the Osmads2-1 Osmads6-1 double mutant displayed defects in the outer three whorls, and ectopic glume-like organs and lodicule-stamen mosaic structures were present in whorls 2 and 3 (Supplemental Fig. S8a), which mimicked phenotypes of Osmads6-1[10]. Similarly, the Osmads4-1 Osmads6-1 double mutant also contained abnormal spikelet structure, with glume-like structures enclosing the stamen filament, as well as a reduced number of stamens (Supplemental Fig. S8b). Furthermore, Osmads2-1 Osmads4-1 Osmads6-1 triple mutants were made by crossing Osmads2-1 with the Osmads4-1 Omads6-1(+/−) heterozygous double mutant. Homeotic transformation of lodicules and stamens into glume-like organs and abnormal pistils was observed in the triple mutant (Supplemental Fig. S8c), mimicking phenotypes of the spw1-1 Osmads6-1 double mutant except that it lacked the secondary inflorescence inside the spikelet[10]. Taken together, the genetic evidence indicated that OsMADS2 and OsMADS4 are partially redundant with OsMADS6 in specifying lodicule and stamen identities. Unlike OsMADS16/SPW1, OsMADS2 and OsMADS4 may not participate in regulating secondary inflorescence growth and FM determination.

The C-class gene mutant Osmads3-4 displayed mild homeotic transformation of lodicules and stamens into lodicules-like or lodicule-anther mosaic organs in the spikelet (Supplemental Fig. S9a−c)[11]. In Osmads2-1 Osmads3-4, some lodicules were transformed into lodicule-stamen organs (Fig. 1e; Supplemental Fig. S9d−f), whereas the ectopic expression of the stigma identity gene, DROOPING LEAF (DL), was observed in the ectopic carpels (Fig. 1j). On the other hand, the Osmads4-1 Osmads3-4 double mutant displayed new phenotypes, including the transformation of lodicules into lodicule-stigma or lodicule-stamen mosaic organs (Fig. 1f; Supplemental Fig. S9g, h), and ectopic generation of abnormal carpels in whorl 3 (Fig. 1f; Supplemental Fig. S9g, i). These data suggest that in the absence of OsMADS3 and OsMADS4, OsMADS58 alone cannot fully determine the stamen identity. It is possible that in the Osmads3 Osmads4 double mutant, OsMADS58 together with DL are ectopically expressed in the second whorl to help specify stamen identity.

RT-qPCR analysis showed that the expression of DL increased significantly in the Osmads4-1 single mutant at the floral maturation stage (Supplemental Fig. S10a), which prompted in-situ hybridization to investigate the expression pattern of DL in the mutants. Compared to WT and Osmads3-4 (Fig. 1g, h; Supplemental Fig. S4), ectopic expression of DL was detected in the lodicule-stigma mosaic organs of Osmads4-1 Osmads3-4 (Fig. 1i). The combined data suggests that, while the two rice PI-like proteins, OsMADS2 and OsMADS4, play redundant roles in lodicule and stamen specification, they might form different protein complexes in specifying lodicule and stamen identities. Besides its role in lodicule morphogenesis, OsMADS2 also genetically interacts with OsMADS3 in specifying stamen identity. OsMADS58 may need to form a complex with OsMADS4 to better specify stamen identity, and when only OsMADS2 is available, the formation of OsMADS58-SEP tetramers are favored to determine the carpel identity.

Since the expression of OsMADS16 and DL increased in the Osmads4-1 mutant, we performed RT-qPCR to detect transcript levels for all the MADS-box genes known to be involved in the development of lodicule and other reproductive organs to further understand the role of OsMADS4. Interestingly, expression of the E-class genes OsMADS1, OsMADS5, OsMADS7, OsMADS8 and OsMADS34 (Supplemental Fig. S10b−f), as well as OsMADS32 and OsMADS6, was obviously increased during early spikelet development in Osmads4-1, but not in Osamds2-1 (Fig. 1b; Supplemental Fig. S10g, h). A similar expression pattern was observed for AP1-like genes OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 and OsMADS58 (Supplemental Fig. S10i−k), suggesting that OsMADS4 may have evolved a function in regulating rice floral meristem development. Previous evidence indicated that changes in gene expression and/or protein function might cause functional divergence for duplicated genes[1]. The in-situ hybridization analysis detected OsMADS4 transcripts in the FM at Sp4 and stamen at Sp7, similar to those of OsMADS2[12], but hardly detected signals in the FM at Sp7 (Fig. 1c, k), which is different from a previous report in which the expression of OsMADS4 was detected in carpel primordium[12]. This discrepancy might have been caused by the stage of the analyzed materials, as the floret used in the present study was at early Sp7, whereas the previous report used material at the late Sp7 stage. Together, these results indicate that the spatial-temporal expression of the rice PI-like genes as well as the formation of their protein complexes are key mechanisms that drive their specific functions.

In Arabidopsis, the B-class genes regulate FM maintenance and termination in an AG-dependent manner, as the AG/SEP-AG/SEP complex can switch to the AG/SEP-AP3/PI quartets under the ectopic expression of AP3/PI proteins[13]. Extra mrp-like glumes and lodicule-stigma mosaic organs grew in the Osmads4-1 Osmads3-4 (Fig. 1f), spw1-1 Osmads3-4 and spw1-1 Osmads58 double mutants[5], suggesting that rice B genes also play a conserved role in maintaining the size of FM. Therefore, the B-class proteins may be key regulators that determine stage-specific protein quartet complex formation during flower development, both at the transcription and protein levels. Exploring the specificities of different protein quartets at various stages of flower development would help us discern the spatial-temporal regulatory networks in FM maintenance and termination.

Similar to the present observation with Osmads3 spw1-1, a previous study also observed lodicule-stigma mosaic organs in the spw1-1 Osmads58 double mutants[8]. It is therefore speculated that OsMADS4, OsMADS16, OsMADS3, and OsMADS58, together with E-class and AGL6-like proteins, might form different complexes in specifying lodicule, stamen, and pistil identities (Fig. 1l). Additional in vivo protein interaction data are needed in the future to support the concept of a 'complex transition' that occurs in different whorls. Our observation, along with the ectopic expression of the leaf- and stigma-specific gene DL, in the lodicule of the Osmads4-1 Osmads3-4 mutants, suggests that rice lodicule is a bracteopetal organ derived from a modified leaf, rather than an andropetal stamen-derived organ. In this case, duplication of rice B-class genes may have contributed to the diversification of petal-like organs in grasses, just like in eudicot. To test this hypothesis, it will be important to elucidate in the future whether and how the OsMADS4-OsMADS3 complex represses the expression of DL.

HTML

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yuan Z, Wang L; project supervision: Yuan Z; Osmads2 and Osmads4 CRISPR lines generation: Li QL; analysis and interpretation of results (experiments): Yuan Z, Wang L; draft manuscript preparation and revision: Wang L, Yuan Z, Hu JP. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data used in this work are publicly available.

This paper is dedicated to the late Prof. Dabing Zhang, who provided unwavering support to this project until his tragic passing in June 2023. We would like to acknowledge funds from the Natural Science Foundation of China (32170322, 31671260), China-Germany Mobility Program (M-0141), Special Funds for Construction of Innovative Provinces in Hunan Province (2021NK1002), China Innovative Research Team, Ministry of Education, the Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities (111 Project, B14016), and the SMC Morningstar Young Scholarship of Shanghai Jiao Tong University to Z.Y.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplemental Fig. S1 OsMADS2 mutant alleles (a) Schematic diagram of OsMADS2 gene structure. Grey boxes represent 5’UTR and 3’UTR, black boxes represent exons, and thick black lines represent introns. The black arrowhead indicates the sgRNA target site, Osmads2-1 and Osmads2-2 had “A” and “TT” insertion in the OsMADS2 coding sequence, respectively. The underlined letters indicate protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), Red letters indicate mutation types. (b) The sequencing results showing mutation information of Osmads2-1 and Osmads2-2, compared to that in wild type. Red arrows indicate mutation site.

- Supplemental Fig. S2 Phenotypic analysis of spikelet morphology in Osmads2-1 and Osmads2-2 (a) and (b) Spikelet of Osmads2-1 (a1-a4) and Osmads2-2 (b1-b4). Pink arrowheads in a2, a4, b1 and b4 indicate extended lodicules; elo, extended lodicule; le, lemma; lo, lodicule; pa, palea; pi, pistil; st, stamen. Scale bars, 2 mm.

- Supplemental Fig. S3 OsMADS4 mutant alleles (a) Schematic diagram of the OsMADS4 gene. Grey boxes represent 5’UTR and 3’UTR, black boxes represent exons, and thick black lines represent introns. The black arrowhead indicates the mutation target site, Osmads4-1 and Osmads4-2 contain a T deletion and a T insertion, respectively, in the OsMADS4 coding sequence. (b) Sequencing results of the target site of wild type, Osmads4-1 and Osmads4-2.

- Supplemental Fig. S4 The in-situ hybridization sense control of DL DL is the abbreviation of DROOPING LEAF; Scale bars, 50 μm.

- Supplemental Fig. S5 Phenotypic analysis of spikelet development in Osmads4-1 and Osmads4-2 (a) and (b) Spikelet of osmads4-1 (a1-a4) and osmads4-2 (b1-b4) single mutant. ca, carpel; le, lemma; lo, lodicule; pa, palea; pi, pistil; st, stamen. Scale bars, 2 mm.

- Supplemental Fig. S6 Phenotypic analysis of spikelet morphology in Osmads2-1Osmads4-1 double mutant. (a) Spikelet of Osmads2-1 Osmads4-1.(b) Spikelet of Osmads2-1 Osmads4-1 after the removal of lemma. (c) Spikelet of Osmads2-1 Osmads4-1 after both lemma and palea were removed. Blue arrowheads indicate glume-like structure organs; red arrowhead indicate abnormal-pistils; yellow arrowheads indicate enlarged ovaries. a-pi, abnormal-pistil. eno, enlarged ovary; gll, glume-like structure; le, lemma; lo, lodicule; pa, palea. Scale bars, 2 mm.

- Supplemental Fig. S7 Expression analysis of B-class genes in WT and mutants. (a) OsMADS2 expression pattern in the inflorescence of WT and Osmads4-1. (b) RT-qPCR analysis of OsMADS4 in WT and Osmads2-1. (c) RT-qPCR analysis of OsMADS4 in WT, Osmads2-1 and Osmads4-1. Total RNA was isolated from 3-mm and 5-7-mm young inflorescence of WT, Osmads2-1 and Osmads4-1. Data are shown as mean± sd, Error bars indicate SD for three biological replicates. ** indicates P-values < 0.01 and * indicates P-values between 0.05 and 0.01, analyzed by the Student-t test.

- Supplemental Fig. S8 Phenotypic characterization of the spikelet in the Osmads2-1 Osmads6-1, Osmads4-1 Osmads6-1 and Osmads2-1 Osmads4-1 Osmads6-1 mutants (a) to (c) Spikelet morphology (1-4) and schematic diagram (5) of Osmads2-1 Osmads6-1 (a), Osmads4-1 Osmads6-1 (b) and Osmads2-1 Osmads4-1 Osmads6-1 (c). Aqua blue arrowheads indicate glume-like structures; Orange arrowheads indicate lodicule-stamen mosaic organs; Light yellow arrowheads indicate abnormal pistils. a-pi, abnormal pistil; bop, body of palea; fl, floret; gll, glume like organ; le, lemma; lo, lodicule; l-s, lodicule-stamen mosaic organ; mrp, margin region of palea; pa, palea; rg, rudimentary glume; sl, sterile lemma; sp, spikelet; v, vascular bundles. All scale bars are 2 mm.

- Supplemental Fig. S9 Phenotypic analysis of the spikelet in the Osmads2-1 Osmads3-4 and Osmads4-1 Osmads3-4 double mutants. (a)to (c) Spikelet morphology of Osmads3-4. (d) to (f) Spikelet morphology of Osmads2-1 Osmads3-4. (g) to (i) Spikelet morphology of Osmads4-1 Osmads3-4. Orange arrowheads indicate lodicule-stamen mosaic organ; Yellow arrowheads indicate abnormal pistil; Rose arrowheads indicate lodicule-stigma mosaic organ. le, lemma; lo, lodicule; l-p, lodicule-pistil mosaic organ; l-s, lodicule-stamen mosaic organ; pa, palea; pi, pistil; st, stamen. Scale bars, 2 mm.

- Supplemental Fig. 10 Expression analysis of DL and some MADS-box genes in WT and mutants. (a) Expression level of DL in WT, Osmads2-1 and Osmads4-1. (b) to (f) Expression levels of class-E genes (OsMADS1, OsMADS5, OsMADS7, OsMADS8 and OsMADS34) (b, c, d, e and f, respectively) in WT and the Osmads2-1 and Osmads4-1 mutants. (g) and (h) Expression level of OsMADS32 and OsMADS6 in WT and the Osmads2-1 and Osmads4-1 mutants.

- Supplemental Table S1 Primers used in this study.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| Wang L, Li QL, Hu JP, Yuan Z. 2024. Neofunctionalization of B-class genes in regulating rice flower development. Seed Biology 3:e013 doi: 10.48130/seedbio-0024-0012 |