-

Fungi are a diverse group of microorganisms that inhabit various environments such as soil, water, plant parts (roots, leaves, and fruits), and other food sources and they occupy a large variety of eukaryotic organisms[1−4]. Macrofungi, sometimes referred to as mushrooms, are one recognizable group of fungi, having umbrella-like characteristics. These mushrooms often appear to have stalks, distinct spore-bearing fruiting bodies and are visible to the naked eye[5]. Typically, mushrooms play a vital role in the environment as decomposers and nutrient recyclers[6,7]. Mushrooms are categorically identified as: edible, medicinal, poisonous, and those in a miscellaneous category, whose properties remain unidentified[8].

Mushrooms are ecologically significant species; they often form symbiotic associations crucial in a constantly changing balance in the ecosystem. In the environment, they play roles as decomposers and bioremediators that supply nutrients to other organisms for survival[9]. Admittedly, mushrooms influenced the human population on a large scale since they are vital to economy and health for the past few decades and presently are cultivated for human consumption. Primarily, mushrooms are consumed as food. They are popular delicacies around the world that are prominently part of the human diet including morels, shiitake mushrooms, and chanterelles[10]. Over time, studies revealed that mushrooms contain enormous amounts of nutritional value utilized mainly as a source of food and medicine. They contain compounds such as protein, carbohydrates, minerals, vitamins, unsaturated fatty acids, phenolic compounds, tocopherols, ascorbic acid, and carotenoids. Being considered as having high fiber, low fat and low starch, edible mushrooms have been recognized to be ideal food for diabetes. They are also known to possess promising health beneficial components such as antioxidative, cardiovascular, hypercholesterolemia, antimicrobial, hepato-protective, and anticancer properties[11−14].

Apart from its medicinal properties and uses, macrofungi also play a crucial role as a mycorrhizal member necessary for normal development of plants and trees. In this view, macrofungal diversity is an important forest health indicator. Their diversity, distribution, and interrelationships can serve as measures of habitat quality and the determinants of the changes that occur in a given environment[15]. Loss of macrofungi can imply a negative impact on the abundance of plant species specifically on trees that make up forest ecosystems total biomass[16]. Forests in the Asian regions harbor diverse species of these macrofungi that are naturally growing on different substrates such as soil, leaf litter, decaying plant residues, decomposing logs of trees, and even land pastures particularly during rainy seasons where growth is highly favored by wet substrate condition[17,18]. There are a number of reports on the list and distribution of macrofungi in Asia including The Philippines. The Philippines as a tropical country with a seasonal wet climate has become a favorable habitat for a large number of macrofungal species. Interestingly, only a few macrofungal studies of different provinces where mushrooms inhabit have been conducted including Nueva Ecija[19,20], Isabela[21], Laguna[22,23], Tarlac[12], and the Province of Bukidnon[24]. To date, the Mt. Arayat Protected Landscape (MAPL) remained unexplored. It is a dormant stratovolcano with an aggregated forest area covering 3,715.28 hectares and 1,030 meters highest elevation[25]. Moreover, MAPL has been identified as one of the centers of biodiversity conservation and proclaimed as a protected area since 1997[26]. Despite this status, only limited studies on macrofungal biodiversity have been carried out in the area. Hence, this study was conducted in an attempt to document the first diversity and distribution of macrofungi in MAPL as a significant endeavor toward conservation and preservation of forest resources.

-

Before the start of this research, the proposal was presented to the Protected Area Management Board (PAMB) on February 2023. Permit with No. III-2023-008 (New) was issued in May 2023 by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, San Fernando, Pampanga, The Philippines.

Study site

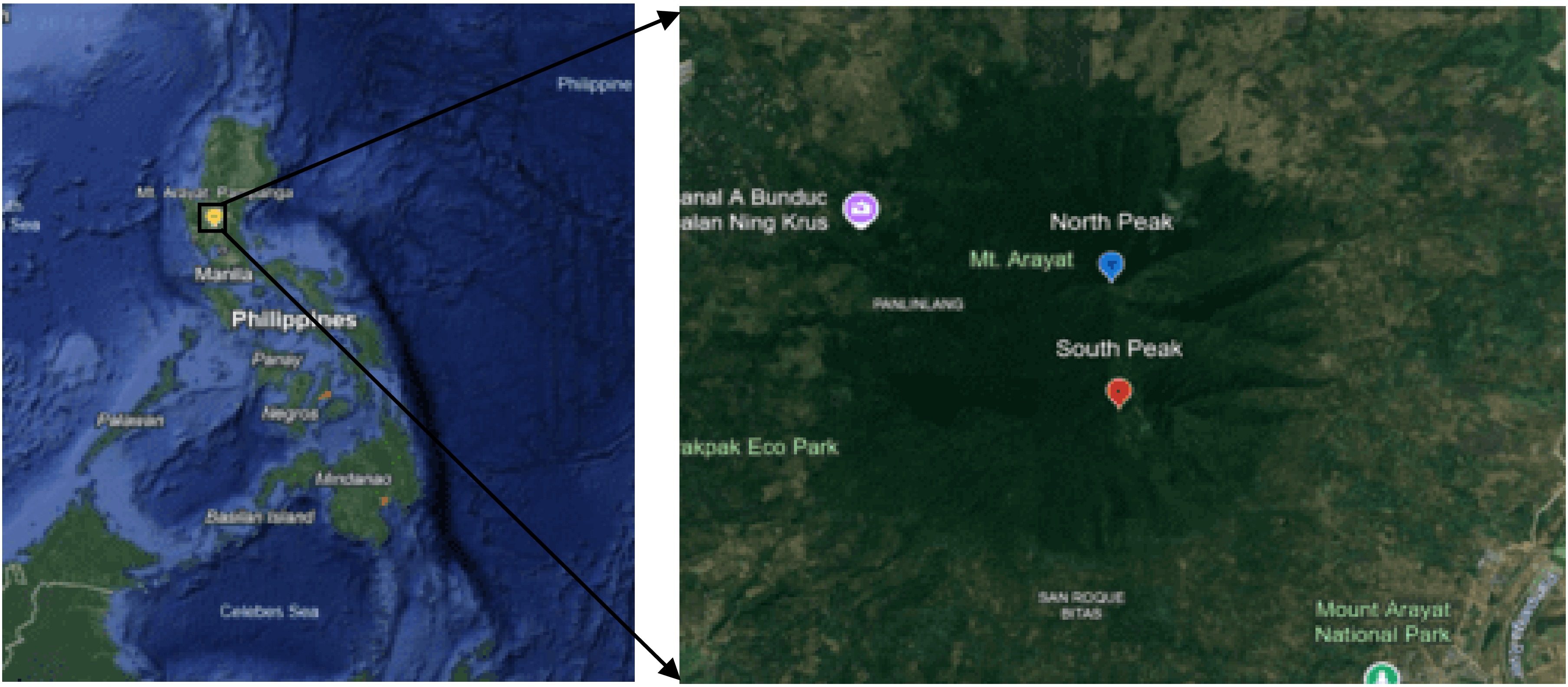

-

The Mt. Arayat Protected Landscape (MAPL) (15°12'00" N/120°43'59" E) popularly known as Mt. Arayat National Park was reclassified as a protected landscape through Republic Act 11684 in April 2022. This remote mountain is situated at the center plain of Luzon with an altitude between 100 and 1,030 meters above sea level (masl). Its topography is rolling to moderately steep at the lower parts and generally steep and rugged at the upper portions. The western part is covered by a circular volcanic crater about 1.2 km in diameter, while the northern rim had collapsed due to soil erosion. The mountain consists of three peaks; the North Peak (15°12'00" N/120°44'00" E) is where the main summit is located with the highest elevation of about 1,030 m via Barangay Ayala, Magalang route, while the South Peak (15°17'35" N/120°76'42" E) is about 984 m via Barangay San Juan Banyo, Arayat route, and the Pinnacle Peak (15°10'60" N/120°43'59" E) is about 786 masl, situated between the North and the South Peaks (Fig. 1). Due to a dangerous ridgeline of the Pinnacle, the North Peak and South Peak were the only designated areas as collection sites. Collection of macrofungal species was conducted along the trail lines due to the steep terrain of the study sites. The Mt. Arayat Protected Landscape falls under climatic type I and has an annual temperature range of 22−31 °C and an annual rainfall range of 284−1,844 mm. Moreover, MAPL is characterized by a moist tropical climate where the maximum rainfall period is from May to October and dry period from November to April[27].

Field sampling of macrofungi

-

Purposive sampling was used as the collection procedure[12]. Macrofungi were documented in their natural habitat and three transect lines (1,000 m long each) were used to represent the collection sites. Each study site was visited every month from July to December of 2023. Records of temperature, rainfall, and relative humidity during the time of collection were obtained from The Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA). Such data represented the weather conditions of the site investigated. Also, the substrate type and growth habits of macrofungi were documented. Using Global Positioning System (GPS), the location and elevation of the habitat of each macrofungal species were recorded. Macrofungi were photo-documented in their natural habitat before collection. Fruiting bodies were carefully dug in their substrate to prevent damaging the base. The collected specimens were properly labeled, wrapped in wax paper, and placed in a paper bag for identification in the laboratory. Samples of macrofungi were rescued using the tissue-culture method using potato dextrose agar for further analysis[12].

Morphological identification

-

Identification of the collected samples was carried out using morphometric data. Their macro- and microscopic attributes were analyzed for morphological identification. This includes features of the cap, gill, and stalk. Spore color, shape, and size were observed under the microscope. Macrofungal identity was compared to several species listings and taxonomic works and was authenticated by a mycologist[12,28−33].

Data analysis

-

The percentage composition of the macrofungal taxa was computed to assess the occurrence of macrofungal species in two collection sites, six collection months, and three elevation ranges. The formula used is as follows:

$ {\mathrm {Composition}}\;({\text{%}})=\dfrac{\mathrm{Total\;number\;of\;macrofungi\;occurred}}{\mathrm{Total\;number\;of\;macrofungal\;taxa}}\times 100 $ The diversity indices and level of distribution in the two study sites and three elevation ranges were analyzed using PAST 4.03 software. Shannon diversity index (H), Margalef index (R), and evenness (E) were used to calculate diversity, richness, and equality of distribution respectively.

-

The Mt. Arayat Protected Landscape (MAPL) is known to have a diverse climate depending on the height of the landscape. Although some areas are isolated to a certain extent from other territories, its central part comprises accessible agricultural land and grasslands. At higher altitudes, the vegetation becomes denser, and the deciduous forest where mostly dipterocarp trees are prominent is at the top of the mountain. During the collection of the species, the temperature, and relative humidity were recorded between 7:00−8:00 and 13:00 in the natural environment where each macrofungus was obtained. The average temperature during the collection months July to December recorded the lowest at 23 °C and highest at 35 °C. The humidity was high at 85% in the first four months and dropped at 74% in the last two months of investigation. The soil type is clayish with a measured pH value of 5.4−6.7. In this study, the most intense precipitation was observed in July to September with precipitation varying from 275 to 308 mm. On the other hand, December recorded the least precipitation of only 34 mm. This is because the dry season starts towards the latter months of the year. Altogether a total of 224 macrofungi were collected and documented during the six months of sampling.

Grassland was the habitat of most macrofungal species collected. As shown in Table 1, out of 108 collected species, 59 were not edible. The collected macrofungi were mostly solitary, scattered to gregarious and only a few were caespitose. The majority of the mushrooms were wood-rotting inhabiting dead logs, trunks, decaying twigs, and bamboo as their natural substrates. However, some were found growing in soil, termite mounds, and piles of leaf litter. They were also observed to be symbiotic, parasitic, and saprophytic according to the natural habitats they were recorded. Thus, this investigation can lead to further studies to determine the ecological roles of these macrofungi in the biological cycle of this forest.

Table 1. Edibility, growth habits, substrate, and habitat of 108 macrofungal species in MAPL.

Species Edibility Substrate Growth habit Habitat Agaricus campestris edible soil /bamboo leaf litters solitary grassland Agaricus comtulus edible soil solitary grassland Agaricus moelleri not edible soil solitary grassland Agaricus trisulphuratus not edible soil solitary forest Amanita rubescens not edible rotten log gregarious grassland Amanita sp. 1 not edible soil scattered grassland Amanita sp. 2 not edible soil solitary forest Amanita sp. 3 not edible soil scattered grassland Amanita sp. 4 not edible dead log scattered grassland Amanita sp. 5 not edible soil scattered grassland Amanita sp. 6 not edible soil scattered forest Armillaria mellea edible soil gregarious grassland Auricularia auricula-judae edible dead mango stem scattered grassland, forest Auricularia polytricha edible dead trunk scattered forest Auricularia sp. 1 edible dead trunk scattered forest Calocera viscosa not edible soil solitary forest Calvatia sp. edible at young soil solitary grassland Candolleomyces bivelatus edible soil with leaf litters scattered grassland Coltricia sp. not edible dead trunk scattered forest Cookeina sp. not edible rotten log scattered forest Coprinellus disseminatus edible soil gregarious grassland, forest Coprinellus micaceus edible soil gregarious grassland Coprinopsis atramentaria not edible soil solitary forest Coprinus comatus edible at young soil solitary grassland Coprinus sp. 1 not edible soil solitary grassland Cortinarius violaceus edible but not recommended soil solitary forest Cupophyllus pratensis edible but waxy rotten trunk solitary forest Cyathus striatus not edible dead log gregarious grassland Daedaleopsis sp. not edible dead log scattered forest Daldinia concentrica not edible rotten log solitary forest Flammulina sp. 1 edible dead log gregarious grassland Flammulina sp. 2 edible dead log scattered grassland Fomitopsis feei not edible dead log gregarious forest Fomitopsis pinicola not edible dead log gregarious forest Galiella rufa not edible rotten twig gregarious grassland Ganoderma applanatum edible but not palatable dead trunk solitary forest Ganoderma australe edible but not palatable soil solitary forest Ganoderma carnosum edible but not palatable rotten log solitary grassland Ganoderma ellipsoideum edible but not palatable rotten log solitary forest Ganoderma lucidum edible but not palatable soil solitary grassland Ganoderma sp. 1 edible but not palatable rotten trunk solitary forest Ganoderma sp. 2 edible but not palatable rotten log scattered forest Ganoderma sp. 3 edible but not palatable soil solitary forest Gymnopilus lepidotus not edible rotten log scattered grassland Hypholoma sp. not edible soil caespitose forest Laccaria sp. edible soil solitary grassland Lactocollybia subvariicytis edible leaf litters solitary forest Lentinus tigrinus edible rotten acacia trunk gregarious forest Lepiota cristita not edible soil scattered grassland Lepiota sp. 1 not edible soil solitary grassland Leucoagaricus leucothites edible soil solitary forest Leucoagaricus meleagris edible but not palatable soil scattered grassland Leucocoprinus cepistipes not edible soil scattered grassland Leucocoprinus fragilissimus not edible soil solitary grassland Leucopaxillus amareus edible soil gregarious grassland Lycoperdon perlatum edible when young soil scattered grassland Lycoperdon sp. 1 edible when young soil gregarious grassland Marasmiellus candidus not edible rotten tamarind tree scattered grassland, forest Marasmius albogriseus edible soil gregarious grassland Marasmius oreades not edible soil scattered grassland Marasmius rotula edible rotten twig gregarious forest Marasmius sp. 1 not edible rotten log gregarious forest Marasmius sp. 2 not edible soil solitary forest Marasmius sp. 3 not edible leaf litters solitary grassland Microporus affinis not edible rotten twig of mahogany tree scattered grassland, forest Microporus xanthopus not edible dead twig scattered forest Mycena sp.1 not edible soil with leaf litters gregarious grassland, forest Mycena sp. 2 not edible soil gregarious grassland Mycena sp. 3 not edible soil gregarious grassland Oudemansiella canarii edible rotten mango trunk solitary grassland, forest Oudemansiella mucida edible rotten trunk solitary forest Panaeolus antillarum not edible carabao dung scattered grassland Panaeolus cyanescens not edible carabao dung scattered grassland Pluteus cervinus edible soil gregarious grassland Podosypha elegans not edible dead twig solitary forest Polyporus alveolaris edible dead trunk scattered grassland Polyporus hirsutus edible dead twig scattered grassland Polyporus sp. 1 edible dead trunk scattered forest Polyporus sp. 2 edible dead trunk scattered forest Postia caesia edible rotten trunk scattered grassland Psilocybe inversa not edible soil solitary grassland Pycnoporus sanguineus not edible dead log scattered forest Russula adusta edible soil solitary grassland Russula sp. 1 edible dead log scattered grassland Russula sp. 2 edible soil scattered grassland Russula sp. 3 not edible soil solitary grassland Schizophyllum commune edible rotten bamboo wood, dead log of tamarind tree gregarious grassland, forest Scytinopogon sp. edible soil with leaf litters caespitose to gregarious grassland Stereopsis radicans edible soil caespitose forest Stereum inisignitum not edible rotten log gregarious forest Stereum ostrea not edible rotten log gregarious grassland, forest Stereum sp. 1 not edible rotten twig gregarious forest Termitomyces striatus edible soil gregarious forest Tetrapyrgos subcinerea not edible dead twigs and leaf litters gregarious forest Trametes elegans not edible dead bamboo tree solitary grassland Trametes ellipsospora not edible rotten acacia trunk gregarious forest Trametes gibbosa not edible dead log scattered forest Trametes hirsuta not edible dead log solitary grassland, forest Trametes parvispora not edible dead log gregarious forest Trametes pubescens not edible rotten twig solitary forest Trametes sp. 1 not edible dead log gregarious forest Trametes sp. 2 not edible dead mango tree solitary forest Trametes sp. 3 not edible dead tamarind stem scattered forest Trametes sp. 4 not edible dead trunk of mahogany tree gregarious forest Trametes versicolor not edible dead twig scattered grassland Tricholoma sp. edible soil solitary grassland Xylaria schweinitzii not edible dead log scattered grassland, forest Xylaria sp. 1 not edible dead mahogany tree caespitose to gregarious grassland Physical distribution of macrofungi

-

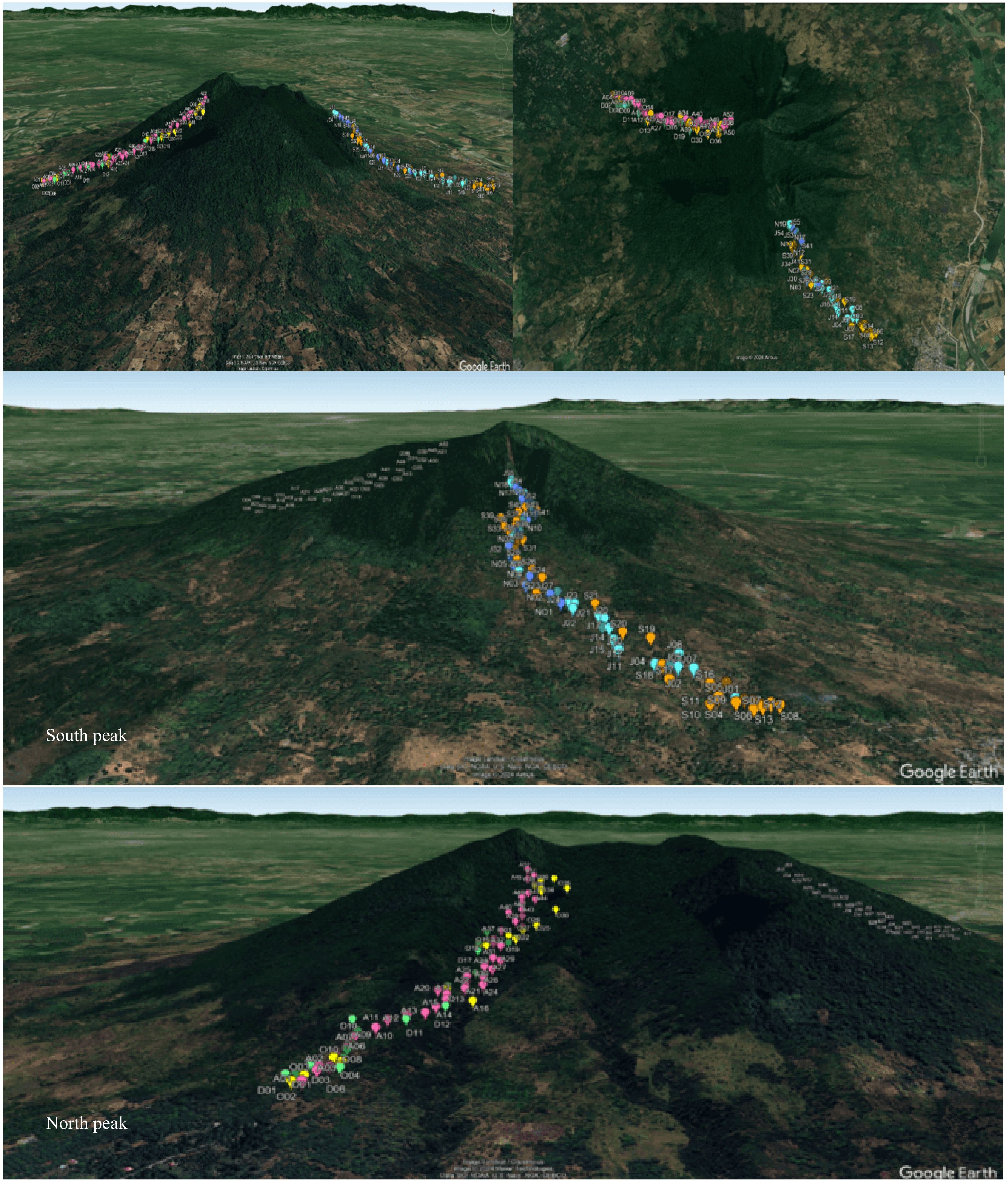

The distribution of different macrofungal species in the two collection areas (Fig. 2) during the collection months, and in three different elevations are shown in Table 2. It can be noted that the South Peak recorded a higher percentage of macrofungal composition at 70.37% while lower macrofungal composition was observed in the North Peak at 52.78%. In the present study, the different macrofungal species in three elevations were documented such as 100−250, 251−500, and 501−750 masl. In general, as shown in Table 2, the macrofungal composition decreased as the elevation increased.

Figure 2.

Distribution of 224 collected macrofungi in two collection sites (South and North Peak), in six collection months July to December (labelled as J, A, S, O, N, and D).

Table 2. Distribution of 108 collected macrofungi in two collection sites, six collections months, and three elevation ranges.

Macrofungi Collection site Collection month Elevation (masl) Site A (S) Site B (N) Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec 100−250 251−500 501−750 Agaricus campestris ▪ • • • ◆ Agaricus comtulus ▪ • • ◆ Agaricus moelleri ▪ • ◆ Agaricus trisulphuratus ▪ • • ◆ Amanita rubescens ▪ ▪ • • ◆ Amanita sp. 1 ▪ • • ◆ Amanita sp. 2 ▪ • ◆ Amanita sp. 3 ▪ • • • ◆ Amanita sp. 4 ▪ • ◆ Amanita sp. 5 ▪ • ◆ Amanita sp. 6 ▪ • • • ◆ Armillaria mellea ▪ • ◆ Auricularia auricula-judae ▪ ▪ • • ◆ ◆ Auricularia polytricha ▪ • • ◆ Auricularia sp. 1 ▪ • ◆ Calocera viscosa ▪ • ◆ Calvatia sp. ▪ • • ◆ Candolleomyces bivelatus ▪ • ◆ Coltricia sp. ▪ • ◆ Cookeina sp. ▪ • ◆ Coprinellus disseminatus ▪ ▪ • • • ◆ ◆ Coprinellus micaceus ▪ • ◆ Coprinopsis atramentaria ▪ • ◆ Coprinus comatus ▪ ▪ • • • ◆ ◆ Coprinus sp. 1 ▪ • • • ◆ Cortinarius violaceus ▪ • ◆ Cuphophyllus pratensis ▪ • ◆ Cyathus striatus ▪ • ◆ Daedaleopsis sp. ▪ ▪ • • ◆ Daldinia concentrica ▪ ▪ • • ◆ Flammulina sp. 1 ▪ • ◆ Flammulina sp. 2 ▪ • ◆ Fomitopsis pinicola ▪ ▪ • • ◆ Fomitopsis feei ▪ • ◆ Galiella rufa ▪ • ◆ Ganoderma applanatum ▪ ▪ • • • • • • ◆ ◆ Ganoderma australe ▪ • • • ◆ ◆ Ganoderma carnosum ▪ ▪ • • • • ◆ ◆ Ganoderma ellipsoideum ▪ • ◆ Ganoderma lucidum ▪ ▪ • • • • • • ◆ ◆ Ganoderma sp. 1 ▪ • • • • • • ◆ ◆ Ganoderma sp. 2 ▪ • • • ◆ ◆ Ganoderma sp. 3 ▪ • • • ◆ Gymnopilus lepidotus ▪ • ◆ Hypholoma sp. ▪ • ◆ Laccaria sp. ▪ • ◆ Lactocollybia subvariicytis ▪ • ◆ Lentinus tigrinus ▪ • ◆ Lepiota cristita ▪ • • ◆ Lepiota sp. 1 ▪ • ◆ Leucoagaricus leucothites ▪ • ◆ Leucoagaricus meleagris ▪ ▪ • • ◆ Leucocoprinus cepistipes ▪ • ◆ Leucocoprinus fragilissimus ▪ ▪ • • ◆ Leucopaxillus amareus ▪ • ◆ Lycoperdon perlatum ▪ ▪ • • • ◆ Lycoperdon sp. 1 ▪ • ◆ Marasmiellus candidus ▪ ▪ • • • ◆ ◆ Marasmius albogriseus ▪ • ◆ Marasmius oreades ▪ • ◆ Marasmius rotula ▪ • • ◆ Marasmius sp. 1 ▪ • • • ◆ Marasmius sp. 2 ▪ • ◆ Marasmius sp. 3 ▪ • ◆ ◆ Microporus affinis ▪ ▪ • • • • • • ◆ ◆ Microporus xanthopus ▪ ▪ • • • • • • ◆ ◆ Mycena sp. 1 ▪ ▪ • • • ◆ ◆ Mycena sp. 2 ▪ • • ◆ Mycena sp. 3 ▪ • • ◆ Oudemansiella canarii ▪ ▪ • • ◆ ◆ Oudemansiella mucida ▪ • ◆ Panaeolus antillarum ▪ • ◆ Panaeolus cyanescens ▪ • ◆ Pluteus cervinus ▪ • ◆ Podoscypha elegans ▪ ▪ • • ◆ ◆ Polyporus alveolaris ▪ • • ◆ Polyporus hirsutus ▪ • • • • ◆ Polyporus sp. 1 ▪ • • ◆ Polyporus sp. 2 ▪ • ◆ Postia caesia ▪ ▪ • • ◆ Psilocybe inversa ▪ • ◆ Pycnoporus sanguineus ▪ • ◆ Russula adusta ▪ • ◆ Russula sp. 1 ▪ • ◆ Russula sp. 2 ▪ • ◆ Russula sp. 3 ▪ • • ◆ Schizophyllum commune ▪ ▪ • • • • • • ◆ ◆ ◆ Scytinopogon sp. ▪ • ◆ Stereopsis radicans ▪ • ◆ Stereum ostrea ▪ ▪ • • • • • ◆ ◆ Stereum insignitum ▪ • • • • ◆ Stereum sp. 1 ▪ • ◆ Termitomyces striatus ▪ • ◆ Tetrapyrgos subcinerea ▪ • ◆ Trametes elegans ▪ • • ◆ Trametes ellipsospora ▪ ▪ • • • • • • ◆ ◆ ◆ Trametes gibbosa ▪ • • ◆ Trametes hirsuta ▪ • • • • • ◆ ◆ Trametes parvispora ▪ ▪ • • • • • • ◆ ◆ Trametes pubescens ▪ • • ◆ ◆ Trametes versicolor ▪ ▪ • • • • • • ◆ ◆ ◆ Trametes sp. 1 ▪ • ◆ Trametes sp. 2 ▪ • • • ◆ Trametes sp. 3 ▪ • • • • • • ◆ Trametes sp. 4 ▪ • ◆ Tricholoma sp. ▪ • ◆ Xylaria schweinitzii ▪ • • ◆ ◆ Xylaria sp. 1 ▪ • ◆ Total 76 57 56 48 55 31 21 17 61 47 28 Composition (%) 70.37 52.78 51.85 44.44 50.93 28.7 19.44 15.74 56.48 43.52 25.93 Composition (%) = (Total number of macrofungi occurred/Total number of macrofungal taxa) × 100; (▪•◆) = present. Abundance of macrofungi

-

After the field collection and documentation of the physical characteristics of the study sites and the distribution of macrofungi based on the different criteria used, the collected specimens were processed and morphologically identified, and a checklist of the collected macrofungi was prepared.

Based on their morphological characteristics, the 224 macrofungal collections were morphologically identified as belonging to two phyla, four classes, 12 orders, 36 families, 53 genera, and 108 species (Table 3). However, the Agaricales order has two incertae sedis fungal genera which means they have not been assigned to a family. Out of 108 species, 70 were identified morphologically up to the species level. The majority of the 103 macrofungal species belong to the phylum Basidiomycota and five species were classified under Ascomycota. Among Basidiomycota, the Agaricaceae and Polyporaceae registered the highest number of genera. Moreover, the genera of Trametes (11), Ganoderma (8), Amanita (7), and Marasmius (6) listed the most number of species. Species of Ganoderma applanatum, G. lucidum, Microporus affinis, Schizophyllum commune, and several species of Trametes were the most dominant species found during the collection months. Schizophyullum commune, Trametes ellipsospora, and T. versicolor were the only species that occurred in all elevation levels.

Table 3. Taxonomic classification of the 108 macrofungal species discovered in MAPL.

Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species Ascomycota Pezizomycetes Pezizales Sarcoscyphaceae Cookeina Cookeina sp. Sarcosomataceae Galiella G. rufa Sordariomycetes Xylariales Xylariaceae Xylaria X. schweinitzii; Xylaria sp. 1 Hypoxylaceae Daldinia D. concentrica Basidiomycota Agaricomycetes Agaricales Agaricaceae Agaricus A. campestris; A. comtulus; A. moelleri;

A. trisulphuratusCoprinus C. comatus; Coprinus sp. 1 Lepiota L. cristita; Lepiota sp. 1 Leucoagaricus L. leucothites; L. meleagris Leucocoprinus L. cepistipes; L. fragilissimus Amanitaceae Amanita A. rubescens; Amanita sp. 1; Amanita sp. 2; Amanita sp. 3; Amanita sp. 4; Amanita sp. 5; Amanita sp. 6 Cortinariaceae Cortinarius C. violaceus Hydnangiaceae Laccaria Laccaria sp. Hygrophoraceae Cuphophyllus C. pratensis Hymenogastraceae Gymnopilus G. lepidotus Psilocybe P. inversa Lycoperdaceae Calvatia Calvatia sp. Lycoperdon L. perlatum; Lycoperdon sp. 1 Lyophyllaceae Termitomyces T. striatus Marasmiaceae Marasmius Marasmius albogriseus; M. oreades; M. rotula; Marasmius sp. 1; Marasmius sp. 2; Marasmius sp. 3 Tetrapyrgos T. subcinerea Mycenaceae Mycena Mycena sp. 1; Mycena sp. 2; Mycena sp. 3 Omphalotaceae Marasmiellus M. candidus Physalacriaceae Armillaria A. mellea Flammulina Flammulina sp. 1; Flammulina sp. 2 Oudemansiella O. canarii; O. mucida Pluteaceae Pluteus P. cervinus Psathyrellaceae Candolleomyces C. bivelatus Coprinellus C. disseminatus; C. micaceus Coprinopsis C. atramentaria Schizophyllaceae Schizophyllum S. commune Strophariaceae Hypholoma Hypholoma sp. Tricholomataceae Leucopaxillus Leucopaxillus amareus Tricholoma Tricholoma sp. Incertae sedis Panaeolus P. antillarum; P. cyanescens Lactocollybia L. subvariicytis Auriculariales Auriculariaceae Auricularia A. auricula-judae; A. polytricha; Auricularia sp. 1 Boletales Boletaceae Pycnoporus P. sanguineus Geastrales Geastraceae Cyathus C. striatus Hymenochaetales Hymenochaetaceae Coltricia Coltricia sp. Polypolares Dacryobolaceae Postia P. caesia Fomitopsidaceae Fomitopsis F. pinicola; F. feei Ganodermataceae Ganoderma G. applanatum; G. australe; G. carnosum;

G. ellipsoideum; G. lucidum; Ganoderma sp. 1; Ganoderma sp. 2; Ganoderma sp. 3Podoscyphaceae Podoscypha P. elegans Polyporaceae Daedaleopsis Daedaleopsis sp. Lentinus L. tigrinus Microporus M. affinis; M. xanthopus Polyporus P. alveolaris; P. hirsutus; Polyporus sp. 1;

Polyporus sp. 2Trametes T. elegans; T. ellipsospora; T. gibbosa; T. hirsuta; T. parvispora; T. pubescens; T. versicolor; Trametes sp. 1; Trametes sp. 2; Trametes sp. 3; Trametes sp. 4 Russulales Russulaceae Russula R. adusta; Russula sp. 1; Russula sp. 2; Russula sp. 3 Stereaceae Stereum S. ostrea; S. insignitum; Stereum sp. 1 Stereopsidales Stereopsidaceae Stereopsis S. radicans Trechispolares Hydnodontaceae Scytinopogon Scytinopogon sp. Dacrymycetes Dacrymycetales Dacrymycetaceae Calocera C. viscosa Diversity and distribution of macrofungi

-

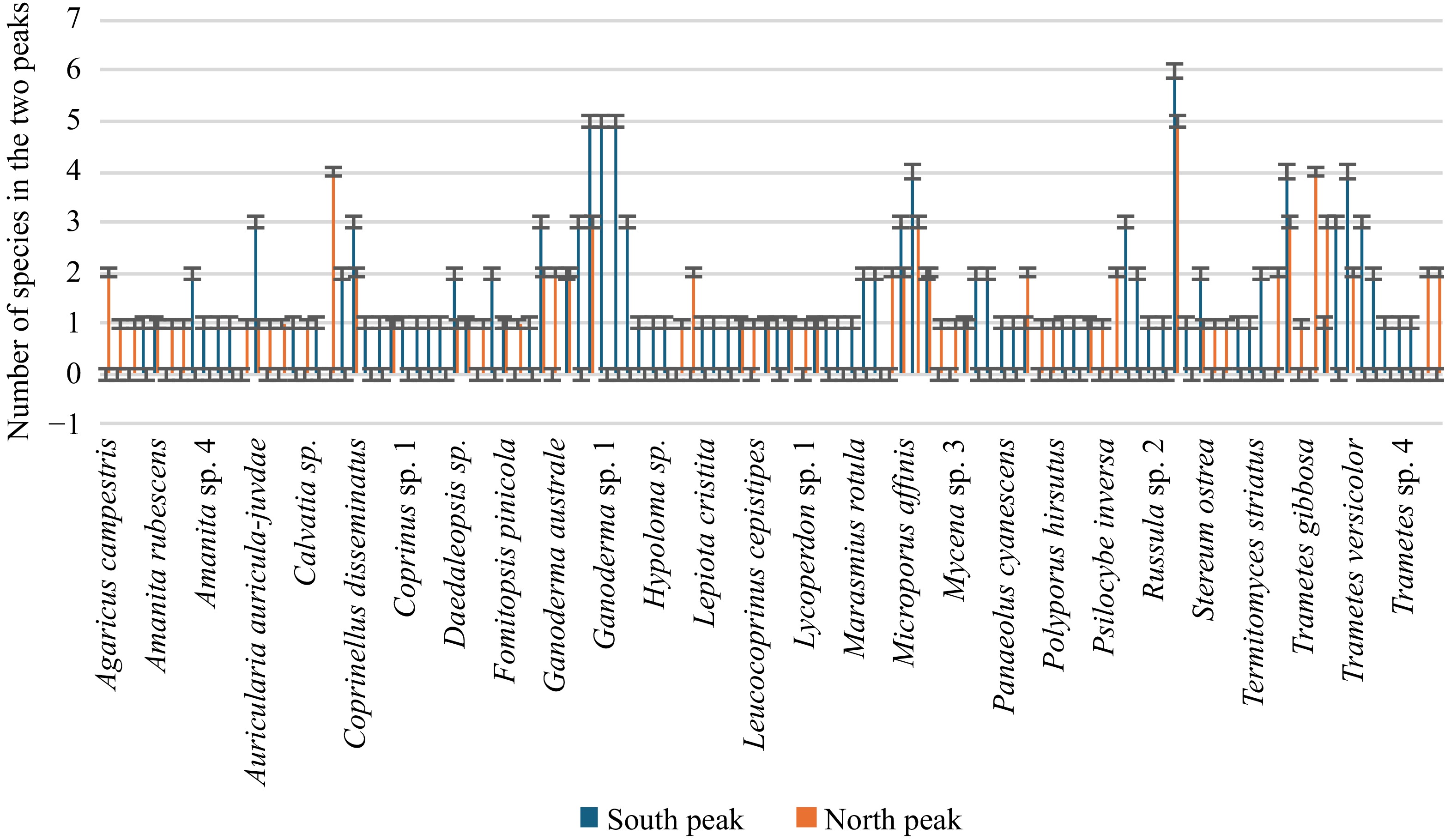

There were 224 collections of macrofungi found in the two collection sites of Mt. Arayat Protected Landscape (MAPL) where 135 species reside in the South Peak and 89 in the North Peak (Fig 3). The macrofungal diversity, richness, and evenness in MAPL were calculated based on Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index (H), Margalef (R), and Evenness (E) respectively to provide representation of species diversity along with rarity and commonness of their distribution in the investigated sites. As revealed in Table 4, the computed Shannon Index in the two collection sites was very high. However, the South Peak, (H) = 4.16, obtained slightly higher diversity than the North Peak, (H) = 3.892. This result indicates that the South Peak reflects a potentially well-abundant species due to a more balanced and favorable resource conditions of its microhabitats. On the other hand, Margalef indices of the two peaks revealed high species richness. A slight difference was noted in their richness composition as South Peak obtained (R) = 15.49 compared to the North Peak (R) = 12.25. The results also implied an equitable distribution of macrofungal species in the two collection sites of South Peak (E) = 0.8322 and North Peak = 0.875. The similarity index value of Sorensen obtained a value of 0.366 indicating a moderate level of overlap in species between the two collection sites.

Figure 3.

Observed species diversity in the South Peak and North Peak of the Mt. Arayat Protected Landscape.

Table 4. Species diversity and similarity index in the two peaks of the Mt. Arayat Protected Landscape.

Collection site No. of taxa Shannon

index (H)Margalef (R) Evenness (E) South Peak 135 4.16 15.49 0.8322 North Peak 89 3.892 12.25 0.875 Sorensen similarity index South Peak vs

North Peak0.366 As shown in Table 5, the diversity, richness, and evenness of macrofungi in MAPL along elevation gradients were also calculated. The highest diversity of species was recorded in the lowest elevation of 100−250 masl with the following results (H) = 4.066, (R) = 13.8, and (E) = 0.9113. On the other hand, the highest elevation of 501−750 masl has the lowest species diversity among the three elevation ranges as shown in Fig. 4. This suggests that the rich community of macrofungi in a lower elevation can be attributed to several factors such as microclimatic conditions temperature, humidity, and rainfall, and type of vegetation, for optimum growth and development. The lowest elevation, 100−250 masl also shows the highest Margalef index of 13.80, confirming its greater species richness relative to the number of individuals suggesting a decrease in species richness as the elevation increases.

Table 5. Species diversity and similarity index of different elevation ranges in the Mt. Arayat Protected Landscape.

Elevation ranges (masl) No. of taxa Shannon index (H) Margalef (R) Evenness (E) 100–250 96 4.066 13.80 0.9113 251–500 82 3.696 10.21 0.8761 501–750 46 3.120 6.53 0.8711 Sorensen similarity index 251–500 vs 100–250 0.36 251–500 vs 501–750 0.197 501–750 vs 100–250 0.141

Figure 4.

Observed species diversity in different elevations: 100−250 masl, 251−500 masl, and 501−750 masl of the Mt. Arayat Protected Landscape.

The evenness values relative to the three elevations showed that 100−250 masl has the highest evenness value of 0.9113 which indicates a relatively more even distribution of individuals across species. The evenness decreased slightly at 251−500 masl with a value of 0.8761 but remained similar at 501−750 masl with a value of 0.8711. Sorensen similarity index among the three studied elevations revealed that the 251−500 masl vs 100−250 masl = 0.36 indicates a relatively moderate similarity in the macrofungal species present in between these elevations. Moreover, in a higher elevation, shared species were rarely observed specifically between 251−500 and 501−750 masl. Similar results were found between 100−250 and 501−750 masl. Some of the identified species are shown in Fig. 5.

-

Understanding the diversity and distribution of macrofungal species is important to determine their ecological characteristics and functioning[34]. Thus, the results of this study are valuable data that shows distinct macrofungal taxa. Out of 224 collections, 108 species were identified morphologically up to the genus level, and 70 species were identified up to the species level. The species composition of the two peaks in Mt. Arayat Protected Landscape (MAPL) is dominated by phylum Basidiomycota (103) while Ascomycota (5) as the least, more so, with order Agaricales, family Agaricaceae and the order Polyporales, family Polyporaceae. The high composition of Basiodiomycota is highly attributed to the profound availability of leaf litter and weathered wood in the soil. The dominance of this phylum is supported by similar results documented in Palau Sibu[35], Bicol University Kalikasan Forest[36], Mount Isarog National Park[30], UITM Forest Reserve, and Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia[37]. In this investigation, 53 macrofungal genera were identified, among which the more species-rich were Amanita, Ganoderma, and Trametes.

The habitat of MAPL is composed mostly of wood-rotting macrofungi growing favorably on fallen logs, trunks, branches, and decaying logs and twigs. While others emerge in soil and a few on piles of leaf litter and animal dung. With this, macrofungal species exhibit various growth strengths in response to the availability of substrates mostly in a grassy type of habitat than the forest area. They are decomposers, indeed, their existence in MAPL is ecologically important specifically in the soil nutrient cycle. Thorough investigation of their roles as saprophytes or mycorrhiza in the forest area of MAPL is necessary to elucidate their ecological functions. Aside from their biological roles in the ecosystem, the edibility of macrofungi is also a key for human survival. Macrofungi are utilized as a nutraceutical source, for food and medicinal purposes. Although some species are edible, there are some that are not recommended for consumption as they contain toxic and hallucinogenic compounds such as Panaeolus antillarum but may contain valuable mycochemicals[38]. In this regard, their value in the pharmaceutical industry must be analyzed as potential sources of pharmacological inputs.

The distribution of macrofungi in natural habitats in MAPL could be influenced by several environmental factors such as vegetation, altitude, and climatic conditions (humidity, rainfall, and temperature). Higher diversity indices were recorded in the South Peak as computed by the Shannon and Margalef indices. The two collection sites shared moderately similar macrofungal species based on the calculated Sorensen similarity index. They also revealed an almost similar evenness of distribution patterns. These results conform to the idea that the abundance of macrofungi is related to the abundance of vegetation in a given environment. Sufficiency in diversity suggests the forest health condition of MAPL. Consequently, a minimal difference in macrofungal diversity of the collection sites observed relies considerably on a few factors. The total species richness can be determined by different vegetation types[39]. In a study of forest types in Ireland, the coniferous forest was found significantly higher in macrofungal diversity than a deciduous forest[40]. Thus, the composition of macrofungal communities can be predicted by the type of dominant tree species. However, this result opposes the macrofungal diversity analysis in Carpathians, Slovakia where higher species richness was noted in the deciduous forest than in a coniferous forest[41]. In MAPL, both study sites obtained high diversity indices due to the similarity of vegetation type and both are confined in a not-so-distant climatic zone. Although the South Peak has a slightly abundant macrofungal composition compared to the North Peak, the difference can be attributed to the fact that the South Peak's forest cover is lusher. Since the North Peak has a wider rim, the area is utilized mainly for agricultural farming of vegetables. During the fieldwork, charcoal-making and fragmented slash-and-burns were also evident. The North Peak is also converted into a pilgrimage site and is used as a trail and campsite to the summit by mountain enthusiasts. More likely, it is utilized as a recreational site. These conditions disturb the natural ecological balance which results in fewer occurrences of macrofungi.

Macrofungal species across elevations and amount of precipitation

-

Elevation or altitude is defined as the height of a certain place above the sea. This factor can considerably influence the diversity and distribution of macrofungal species in their natural substrates. As shown in Table 2, the elevation of 100−250 masl registered the highest macrofungal composition (56.48%) while the lowest macrofungal composition was observed in 501−750 (25.93%). The observed variation could be due to the presence of trees and types of vegetation in the lower elevation. Shannon and Margalef diversity indices were observed highest in the lowest elevation of 100−250 masl and lowest at 501−750 masl. The evenness of distribution was highly uniform in all elevations. In terms of similarity with shared species, the Sorensen similarity index results showed moderate similarity between the 100−250 and 251−500 masl study sites. Some of the identified species of macrofungi were commonly distributed in these two elevations, such as Auricularia auricula-judae, Coprinellus disseminatus, Ganoderma carnossum, G. lucidum, Microporus affinis, Mycena sp., and several species of Trametes. The saprophytic nature of these mushrooms is favorably enhanced due to the presence of leaf litter, decaying logs and twigs, which increased soil quality. Low similarity of species was shared by 100−250 masl vs 501−750 masl. The differences in diversity could be due to several factors such as soil type, climate, vegetation, and agricultural practices[42]. Previous studies suggest that the diversity of macrofungal species and elevation are closely related[43]. The findings of the present study are consistent with earlier findings that macrofungal diversity increases as elevation tends to decrease. A previous study disclosed that the macrofungal diversity was higher in regions with low and medium elevation compared to those with high elevation[44]. In Byeonsanbando National Park, Korea, there was a relative decrease in the composition of species at elevations of 0−400 m[45]. Similarly, macrofungal species collected in Mount Cameroon Region, Africa decreased as altitude increased[44]. A significant difference was also observed in the trend of the macrofungal species diversity in the Shaluli Mountains in the Tibetan Plataeu where there was an increasing diversity in moderate heights and decreasing diversity in higher elevations.

These results, however, are contrary to the documented data in Mount Maculot, Cuenca, Batangas, The Philippines where more species were found in higher elevations 696−869 masl compared to lower elevations of 348−695 masl[28]. Out of 92 collected species, 89% were found in higher forested areas while 26% were found inhabiting the lower grassland area. The lowest elevation of Mt. Maculot has been converted into agricultural lands. Additionally, low composition in the lower elevation is due to a portion of rocky substrate since Mt. Maculot is a well-known trail for hikers seeing the famous Mt. Taal. This also collaborates recorded data in Sitio Canding, San Clemente, Tarlac, The Philippines where lower macrofungal composition is found in higher altitudes[12]. This reason is mainly attributed to the disturbed habitat of a less-elevated site, such as the minimal presence of trees and conversion of lands into agricultural activities. This scenario minimizes the presence of suitable substrates that limit macrofungal dispersion and proliferation. Climatic conditions such as temperature, relative humidity, and rainfall are important factors that can influence the distribution and growth of macrofungi. Variations in the temperature could be a result of an elevation change.

It is commonly known that temperature decreases as the elevation increases. Temperature and humidity are essential factors that can influence the distribution and growth of macrofungi in MAPL. Generally, macrofungi require a temperature of 25−35 °C for mycelial growth and fruiting body production. During the collection periods, there was no remarkable difference in the temperature ranging from 23−35 °C. Although there was no significant change in temperature during the entire course, there was a significant decrease in the amount of rainfall in the latter collection months of November and December. This significantly affected the aggressive fructification of macrofungi. Studies suggest that mycelial growth and density of macrofungi is high at an optimum temperature of 16 to 36 °C. Elevated average soil temperature causes sensitivity of fruiting body formation thus, delaying the opportunity of fungal proliferation[46−49]. A minimal increase of 1 °C corresponds with a one-week fructification delay in mushroom development, thus temperature is a limiting factor[50]. Presumably, the macrofungal composition in MAPL is considerably high and remains unaffected despite changes in zonal temperature in every collection month. The documented temperature during the collection months in different elevations still provided optimal fruiting formation. Relative humidity was high during July to October ranging from 80% to 85% while in November and December dropped to 74%. This phenomenon was caused by the amount of moisture that tends to decrease during the latter period of collection[12]. The municipality of Arayat, Pampanga is regarded as climate Type I, where the amount of rainfall is high July to September. In terms of the collection period, July (51.85%), recorded the highest percentage of macrofungal composition and the lowest in December at 15.74%. This difference in the findings could be attributed to the amount of rainfall during the periods of collection and its effect on decomposition. This is contributory to the slightly acidic property of soil where macrofungi were found. The highest amount of rainfall was recorded in July (753 mm) while the lowest amount of rainfall was recorded in December (34 mm). It is a common observation that several days after heavy rainfall, different species of mushrooms are aggressively growing in their natural habitats. A greater number of species can be found at a suitable temperature with high amounts of rainfall that provides optimum macrofungal development[37,51]. Similarly, higher composition of mushrooms were collected in the rainy month of August compared to a drier month of October in Sitio Canding, San Clemente, Tarlac, The Philippines[12]. This is supported further by diversity and biological characteristics of macrofungi in Bajaur Hindu Kush range in Pakistan. Further, more macrofungi bloomed in July to September and gradually diminished in December and January when the climate turned colder and drier[52]. During these times, the availability of damp woods and moist environments impeded macrofungal growth success. Hence, the amount of moisture in a substrate played a key role in the emergence of macrofungal composition. High amounts of rainfall in MAPL in July provided sufficient amounts of water in the soil and other substrates. The low amount of rainfall in December caused a drop in temperature and humidity. For this instance, temperature, humidity, and rainfall are important climatic considerations in macrofungal growth[53]. Thus, the diversity of macrofungal species is greatly affected by an emerging environmental condition and can impart variation in occurrences across seasons. From this, a better understanding can be drawn of the practical production technology and conservation of wild macrofungi.

Macrofungal diversity and conservation

-

The presence of trees in an area is correlated with the abundance and diversity of macrofungi[54]. Since the emergence of macrofungal communities considerably relies on the integrity of their natural habitat, the effect of physical factors can greatly influence the loss of diversity. Several studies reported that well-conserved forests are correlated with a high proportionality of macrofungi present therein[55,56]. The large gap of macrofungal collections between two phyla in MAPL suggests inadequacy of the appropriate substrates of Ascomycota and that greater number of decomposing macrofungi suggests a minimal disturbance[57]. Ectomycorrhizal fungi act as nutritional support that acts as a stress buffer to native plants, thus the conservation of forests is vital for these macrofungi[58]. Common disturbances in the forest are anthropogenic. The disturbed condition of Mt. Isarog, Camarines Sur is mainly due to denuded canopies caused by natural disasters and man-made activities[30]. The amount of canopies greatly affected the humidity and moisture of the forest floors which resulted in minimal growth of mycoflora. The moist environment of a forest habitat contributes to the richness and diversity of its macrofungal species[59]. The loss of trees exposes the forest floors resulting in drier and warmer conditions thus, limiting growth potential. The recognition of MAPL as one of the known tourist spots in the province of Pampanga is one common forest disturbance. Despite its status as a protected landscape, a huge part of this landscape has long been exposed to disturbances such as charcoal-making, slash-and-burns, and expanded land utilization for agricultural activities[60]. Hence, a subject for protection and sustainability. Altogether, the undisturbed condition of the forest is contributory to its diverse macrofungal distribution. A diverse macrofungal ecosystem is a good indicator of how healthy a forest is. The overwhelming abundance of macrofungi in MAPL still provides evidence of its condition. However, this study was conducted in a limited span of duration which covered only part of the total diversity of MAPL, and is therefore not an adequate reference to safely declare its general quality. Long-term surveys of the trend in distribution patterns, extensive soil and macrofungi profiling should be carried out in the process to better understand the MAPL macrofungal assemblage.

In the intention to provide basic information, and to extend the knowledge about the study, out of 70 identified species, 22 were listed as newly recorded macrofungi in The Philippines, namely: Amanita rubescens, Armillaria mellea, Candolleomyces bivelatus, Cortinarius violaceus, Cuphophyllus pretensis, Ganoderma carnosum, G. ellipsoideum, Lactocollybia subviriicytis, Leucoagaricus leucothites, Leucopaxyllus amareus, Marasmiellus candidus, Marasmius albogriseus, Oudumansiella mucida, Pluteus cervinus, Podoscypha elegans, Postia caesia, Psilocybe inversa, Russula adusta, Stereopsis radicans, Tetrapyrgos subcinerea, and Trametes parvispora. To date, no taxonomic data has been reported about these species. In this regard, molecular identification of these macrofungi is necessary to confirm their identity and to verify their inclusion as new species record of The Philippine's macrofungi.

The team who worked on this study attempted to rescue the collected wild macrofungal species through tissue culture techniques to preserve the cell lines for future biotechnological discoveries. In this present study, the following eight macrofungal species were successfully cultured in potato dextrose agar medium to rescue the mycelia, including, Cyathus striatus, Fomitopsis feei, Ganoderma carnosum, G. lucidum, Lentinus tigrinus, Oudumansiella canarii, Pycnoporus sanguineus, and Xylaria schweinitzii. These valuable macrofungi can be further analyzed as valuable sources of food and medicine. Thus, important mycochemical components can be elucidated for the investigation of their potential as nutraceuticals.

-

This current study is the first to document the macrofungal diversity and distribution in the Mt. Arayat Protected Landscape, of The Philippines. The diversity and richness of macrofungi were high in the South Peak. The elevation of vegetation type, availability of tree species, climatic factors, and anthropogenic disturbances were the main factors affecting the distribution patterns. These results suggest significant information on the diversity of macrofungal communities in MAPL leading to the conservation of the forest landscape as a valuable source of macrofungal resources. The short-term assessment of the abundance and distribution patterns provided a more profound understanding of the total macrofungal ecology of the forest. Therefore, constant and long-term monitoring of macrofungal species combined with high-throughput soil analysis is necessary to determine the diversity and distribution patterns. Further ethnomycological investigations should also be encouraged to document local and Indigenous knowledge of macrofungi for valuable species and exploration of their natural wealth.

-

The author confirms contribution to the paper as follows: study concept and design: Bustillos RG, Dulay RMR, Kalaw SP, Reyes RG; data collection: Bustillos RG; analysis and interpretation of results: Bustillos RG; Draft manuscript preparation: Bustillos RG Dulay RMR, Kalaw SP, Reyes RG. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to proprietary considerations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors sincerely thank Nueva Ecija University of Science and Technology, San Isidro Campus, San Isidro and Center for Tropical Mushroom Research and Development, Central Luzon State University, Science City of Muñoz, Nueva Ecija, Philippines for the assistance. Also, the Protected Area Management Board, Pampanga and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources III for the provisions of this study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Bustillos RG, Dulay RMR, Kalaw SP, Reyes RG. 2024. Diversity of macrofungi along elevation gradients in Mt. Arayat Protected Landscape, Arayat, Pampanga, The Philippines. Studies in Fungi 9: e017 doi: 10.48130/sif-0024-0017

Diversity of macrofungi along elevation gradients in Mt. Arayat Protected Landscape, Arayat, Pampanga, The Philippines

- Received: 31 July 2024

- Revised: 10 November 2024

- Accepted: 13 December 2024

- Published online: 27 December 2024

Abstract: The present study was carried out to document the diversity and distribution of macrofungi in Mt. Arayat Protected Landscape (MAPL), (Pampanga, The Philippines). Purposive sampling was conducted monthly from July to December of 2023 from the baseline (100−750 masl) in South Peak and North Peak collection sites. A total of 224 macrofungi which belong to two phyla, four classes, 12 orders, 36 families, 53 genera, and 108 species were documented. Out of 108 species, 70 were identified at the species level. Most of the documented taxa belong to the phylum Basidiomycota, wherein class Agaricales recorded the highest number of species, followed by Polyporales. The South Peak recorded a higher percentage macrofungal composition of 70.37% than the North Peak with 52.78%. The distribution of macrofungi in the two collection sites was statistically analyzed based on Shannon diversity index (H) Margalef index (R) and evenness (E) revealed higher in the South Peak with 4.16 (H) and 15.49 (R), respectively. Evenness was almost uniform in both collection sites. Sorensen similarity index of 0.366 indicated a moderate level of shared species between the two collection sites. Regarding elevation, the highest number of macrofungal composition was found at 100−250 masl (56.48%), comprised mainly of grass and trees. The lowest number of macrofungal composition was found at 501−750 masl (25.93%), dominated mostly by canopies. The distribution of macrofungi was also higher in 100−250 masl, (H) = 4.066 and (R) = 13.8. The three elevations obtained almost an even distribution. Similarity of shared species was moderately high between 100−250 masl vs 251−500 masl and relatively low between 100−250 masl vs 750 masl. Most macrofungi were found as non-edible and growing solitarily on dead logs and twigs trunks of trees, bamboo, and rotten stumps. Climatic factors such as temperature, humidity, and rainfall, and human-made disturbances affected macrofungal abundance and distribution. The composition was high during the rainy month of July (51.85%) and low in the drier month of December (15.74%). Species of Ganoderma, Microporus, Schizophyllum, and Trametes were commonly found in both collection sites, during the collection months, and at three different elevations (100−250 masl, 251−500 masl, and 501−750 masl). Twenty-two macrofungi were identified and considered as newly recorded species in the Philippines and eight species were successfully tissue-cultured in the laboratory. This high diversity of species observed in MAPL was intricately linked to the functioning of its forest ecosystem which could be a promising source of medicinal macrofungi. Thus, the conservation and sustainability of the forest is deemed necessary.

-

Key words:

- Mt. Arayat Protected Landscape /

- Wild macrofungi /

- Diversity /

- Distribution /

- Elevations