-

Mycelium-based blocks (MBBs) are emerging as an innovative and environmentally sustainable alternative to traditional composite materials, with significant potential to reduce embodied greenhouse gas emissions[1−3]. As a type of mycelium-based composite (MBC), they are biodegradable, lightweight, and versatile, making them suitable for construction, packaging, medicine, and cosmetics applications while promoting more sustainable industrial practices[4−6].

Mycelium-based blocks (MBBs) are created by cultivating fungal mycelium on lignocellulosic substrates, forming a structural matrix with favorable mechanical, physical, and environmental properties[7,8]. Their growing appeal lies in their ability to transform agricultural and industrial waste into value-added products, aligning with the principles of a circular economy, and contributing to waste reduction[9].

The production of MBBs involves various fungal species, substrates, hybridization techniques, reinforcement strategies, and pressing methods, resulting in myco-composites with diverse physical, mechanical, and functional properties[10,11]. For example, a previous study demonstrated that an MBB composed of P. ostreatus and bamboo residues achieved a compressive strength of 0.14–0.45 MPa[12]. Similarly, another study developed an MBB using P. ostreatus and rubberwood sawdust residues, which exhibited a high modulus of rupture (MOR) ranging from 0.72 to 1.57 MPa[13]. A detailed evaluation of these properties is vital to uncover their potential applications and verify their suitability for targeted uses[14,15].

Agricultural crop residues, including those generated by the timber industry, are abundant and rich in cellulose, making them ideal substrates for fungal growth, mycelium cultivation, and the development of MBC materials[7,16]. Among these, spent coffee grounds (SCGs) are a widely available agricultural byproduct that holds significant value due to their nutrient-rich composition and potential for reuse[17]. SCGs complement sawdust by providing several compounds and a fine texture that enhances fungal colonization and growth[18,19]. The combination of sawdust and SCGs provides a cost-effective and sustainable substrate, addressing waste management challenges while supporting MBM production[20]. Additionally, sawdust and SCGs, as biomass waste, demonstrate the potential of existing recycling technologies and the utilization of forestry and agricultural bio-waste for developing high-value-added products, and SCGs are valued for their nutrient density and fine particulate size, facilitating rapid mycelial colonization, thereby improving material density and structural cohesion[21−23].

Bamboo residues (BRs), often discarded as agricultural waste, present considerable potential as lignocellulosic substrates in mycelium-based composite production[21−23]. Abundant and rich in cellulose, BRs offer excellent mechanical reinforcement, enhancing the compressive strength and structural integrity of mycelium-based blocks (MBBs). These residues are widely available in regions with extensive bamboo cultivation, including Southeast Asia (e.g., Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Myanmar), South Asia (e.g., India, and Bangladesh), East Asia (e.g., China), Africa (e.g., Ethiopia, and Kenya), and Latin America (e.g., Colombia, Brazil, and Ecuador)[24,25]. Renowned for their high tensile strength, durability, and cellulose content, BRs are an effective reinforcement material in bio-composite fabrication[24,25].

Similarly, rice husks (RHs), a byproduct of rice milling, are readily available, lightweight, and rich in silica, contributing positively to the physical and mechanical properties of composite materials[26−29]. As a result of their favorable characteristics, RHs are increasingly employed as eco-friendly materials in green construction. They are commonly used as a partial replacement for cement in infrastructure applications, alongside other industrial by-products such as fly ash, slag, red mud, and bagasse ash, supporting sustainability goals and cost-efficiency in material development[30−32].

In this study, bamboo residues (BRs), rice husks (RHs), and spent coffee grounds (SCGs) were employed as lignocellulosic substrates, both individually (100%) and in binary mixtures (1:1 ratio), for the fabrication of mycelium-based blocks (MBBs) using two distinct fungal species: Pleurotus ostreatus and Trichoderma virens. These fungi, representing the phyla Basidiomycota and Ascomycota respectively, were selected based on their contrasting biological characteristics and functional roles in MBB formation. P. ostreatus forms a dimitic to trimitic hyphal structure, which contributes to enhanced mechanical strength and is known for its efficient lignin degradation. It is adaptable to various lignocellulosic substrates and can be effectively regulated or deactivated during large-scale production[16,20,29,33−35].

Conversely, T. virens is a rapidly growing ascomycete capable of quick substrate colonization, however, it lacks a trimitic hyphal structure, instead forming a porous and hydrophilic network that can reduce water resistance and mechanical integrity in the resulting composites[36,37]. Using these contrasting fungi enables a comparative analysis of binding efficiency, mechanical performance, and substrate interactions, thereby guiding the selection of optimal fungal-substrate combinations for sustainable bio-composite development.

Despite increasing interest in mycelium-based composites (MBCs), there remains a significant knowledge gap concerning the influence of fungal species and substrate type on the physical and mechanical properties of MBBs. Most existing studies have centered on individual fungal strains or a limited range of substrates, providing insufficient comparative data for identifying the most effective pairings.

This research aims to bridge this gap by systematically evaluating the performance of P. ostreatus and T. virens on BRs, SCGs, and RHs, individually and in mixed compositions. The key parameters assessed include density, water absorption, compressive strength, and modulus of rupture. By addressing these critical aspects, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of fungal-substrate interactions and supports the development of sustainable mycelium-based materials as viable alternatives in construction and materials science.

-

A pure culture of Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom) in the form of sawdust spawn was obtained from Aranyik Mushroom House, a commercial mushroom farm located in Nakhon Pathom Province, Thailand (13.7350° N, 100.2780° E). Trichoderma virens, initially identified as a contaminant during the preliminary bio-block fabrication process, was subsequently isolated and classified. The original codes RUTK00021 (P. ostreatus) and RUTK00587 (T. virens) were issued to the two cultures.

Preparation of lignocellulosic substrates

-

Three kinds of lignocellulosic substrates were used in this study: spent coffee grounds (SCGs), bamboo residues (BRs), and rice husks (RHs). The SCGs were sourced from Amazon Café and other local cafés in Bangkok, Thailand. They were thoroughly washed to remove impurities, sieved through a No. 40 mesh (aperture size 0.442 mm), and dried at 80–103 °C until a constant weight was achieved. Bamboo residues (BRs) (Dendrocalamus asper (Schult.) Backer: giant bamboo) were sourced from Prachinburi Province and processed into finer particles with a size range of approximately 0.8–1 mm by grinding through a No. 4 mesh (aperture size 4.75 mm) using a Sliver Crest SC-1589 grinder at the Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Rajamangala University of Technology Krungthep, Bangkok. Rice husks (RHs) were obtained from Nakhon Ratchasima Province with a size range of approximately 5–8 mm. To eliminate microbial contaminants before mixture preparation, the lignocellulosic substrates, and all materials, including SCGs, BRs, and RHs, were sterilized at 121 °C for 30 min to eliminate microbial contaminants. After sterilization, the substrates were cooled and subsequently mixed with feeding and growing substrates to ensure optimal conditions for fungal colonization and growth, following the guidelines outlined by Kohphaisansombat et al.[20].

Preparation of feeding and growing substrates and fungal mycelia

-

The feeding substrates were supplemented with 2% glutinous rice flour as a carbon source, 1% pumice (porous volcanic rock) as a mineral source, and 8% rice bran as a protein source to promote fungal growth and substrate colonization. The mixtures were evaluated by blending with three different test substrates: bamboo residues (BRs), spent coffee grounds (SCGs), and rice husks (RHs). All substrates were sterilized at 121 °C for 20 min in an autoclave (TOMY; Japan; TOM-SX-700) to eliminate contaminants before use. Following the sterilization process, the feeding substrate was aseptically inoculated with fungal mycelial cultures of Pleurotus ostreatus (Basidiomycota, strain code RUTK00021) and Trichoderma virens (Ascomycota, strain code RUTK00587)[20].

The feeding substrate was then mixed with lignocellulosic substrates (BRs, RHs, and SCGs) for each treatment, using either individual components (100%) or blended at a 1:1 ratio (50%:50% by weight). The prepared mixtures were transferred into the molds fabricated acrylic test block (5 cm × 5 cm × 5 cm) to facilitate easy removal of the final product and subsequent testing of density, water absorption, and compressive strength. Additionally, larger plastic molds (10 cm × 20 cm × 6 cm) were employed for samples designated for flexural strength testing (modulus of rupture). The mixtures were manually pressed within the molds to ensure uniform distribution and were then placed in a growth chamber maintained at room temperature (~27 to 30 °C) with relative humidity between 70% and 80%. The molds were enclosed in semi-permeable polypropylene bags to provide a sterile and humid environment conducive to fungal colonization. The inoculated substrates were incubated in darkness for 21 d to allow the fungal mycelium to colonize the substrate fully. Upon incubation, the blocks were removed from the molds and air-dried to stabilize the material for further testing and characterization[20].

Characterization of physical and mechanical properties

-

Following a 21-d incubation period, the mycelium-based blocks (MBBs) were thermally treated in a convection oven at 70–80 °C for 12 h to terminate fungal activity and inhibit potential reactivation or microbial contamination. Subsequently, the MBBs underwent characterization to evaluate physical and mechanical properties, including the following parameters:

Density

-

The density of the MBBs, produced using either Pleurotus ostreatus (RUTK00021) or Trichoderma virens (RUTK00587), was determined after completing fungal colonization during a 21-d incubation period under dark conditions and the MBBs were treated in a convection oven at 60 °C for 10 h to render it inactive and prevent any risk of reactivation or contamination. Density measurements were performed following ISO 9427:2003 standards[20], which evaluate the density, moisture content, and water absorption properties of wood-based panels. To determine density, the samples were first dried to a constant weight. The mass (M) of each sample was measured using an analytical balance, while the volume (V) was calculated from the physical dimensions of the blocks. The density (D) was then calculated using the formula: D = M/V; where D is density in kg/m3, M is the mass of the specimen in kilograms, and V is the volume in m3. Each treatment group was tested in triplicate to ensure reliability. The average density values and SD were computed and reported for all experimental groups.

Water absorption

-

The MBBs were dried and prepared for water absorption analysis with slight modifications to established procedures[38]. Samples (size 4 cm × 8 cm) were immersed in distilled water maintained at a controlled temperature of 23–25 ± 1 °C, following the standardized testing protocols of ASTM, which determines the water absorption of plastic materials (ASTM D570, 2024). Each specimen was submerged for 24 h, then removed and drained for approximately 5 min to eliminate excess water before weighing. The water absorption (ASTM D570, 2024) was then calculated using the formula: Water Absorption (%) = (Wet weight – Initial weight) × 100 / (Initial weight). To ensure reproducibility, each sample was tested in triplicate, with results averaged and reported as average values with standard deviations (SD). Post-immersion, the blocks were dried at 80 °C for 24 h to restore stability.

Compressive strength

-

The compressive strength of the MBBs was assessed following a 21-d incubation period in darkness, followed by drying. Testing was conducted using a computerized universal testing machine (Universal Testing Machine, MW-MD-200-CE), with minor adaptations to the ASTM C67 standard[39]. The experiments were performed at room temperature (23–25 °C) with a constant loading speed of 0.5 cm/min. The compressive strength (σ) was calculated using the formula[39]: σ = F/A; where: σ = Compressive strength (MPa); F = Maximum load applied to the specimen until failure (N), and A = Cross-sectional area resisting the load (mm²). To ensure the reliability of the results, three specimens from each treatment were tested, and the results were reported as average values with SDs. The compressive strength was recorded in MPa units, providing a standardized measure of the mechanical performance of the MBBs.

Modulus of rupture (flexural strength)

-

The flexural strength, also known as the modulus of rupture (MOR), of the MBBs was assessed using the three-point bending method, following the ASTM C78 standard[40]. Specimens with dimensions of 10 cm × 20 cm × 6 cm were used for the analysis, with a support span length of 15 cm. The load was applied uniformly at a rate not exceeding 1,000 kg/min or with a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min. This setup ensured precise and consistent evaluation of the MBBs' flexural strength under controlled conditions. The MOR was calculated using the following formula[40]: MOR = (3FL) × (0.0980665) / 2bd2; where: F = maximum applied load (kg), L = span length (cm), b = width of the specimen (cm), and d = depth of the specimen (cm). Three specimens from each composition were tested, and average values and SDs were reported to ensure the reliability of the results.

Statistical analysis and correlation analyses

-

Fungal data obtained from myco-blocks were statistically evaluated by ANOVA using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with a significance threshold set at p < 0.01. In parallel, selected physical and mechanical properties were analyzed via ANOVA at a significance level of p < 0.05, followed by Dunnett's T3 post-hoc tests to pinpoint specific group differences. Additionally, correlation analyses were conducted to assess relationships between the physical and mechanical properties, identifying any statistically significant associations. This study used the Pearson correlation coefficient and Spearman's rank correlation coefficient[41,42]. The Pearson correlation coefficient measures the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two continuous variables. It is calculated using the formula in Eqn (1).

$ r={\sum }_{}^{}({x}_{i}-\underline{x})({y}_{i}-\underline{y})/\sqrt{{\sum }_{}^{}{\left({x}_{i}-\underline{x}\right)}^{2}{\sum }_{}^{}{\left({y}_{i}-\underline{y}\right)}^{2}} $ (1) where, xi and yi are the individual data points for two variables in the correlation analysis. The mean of these variables is x̄ and ȳ, respectively. The Pearson correlation is presented by r, with values near 1 or –1 indicating a strong correlation and near 0 indicating no correlation. The test statistic (t) and the degrees of freedom (df) from the test can be calculated using Eqns (2) and (3), respectively.

$ t=r\sqrt{n-2}/\sqrt{1-{r}^{2}} $ (2) $ df=n-2 $ (3) Where n is the number of observations, using a t-distribution table, the value of p corresponding to the calculated t and df can be determined. The p-value represents the probability of observing the interesting correlation by chance. For instance, if the statistical significance was evaluated at a 95% confidence level, a small p-value (p < 0.05) indicates that the correlation is statistically significant and unlikely to have occurred by chance. When p ≥ 0.05, it suggests that the correlation is not statistically significant. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (ρ) assesses the strength and direction of a monotonic relationship between two variables, regardless of linearity. It is based on the data ranks and calculated using Eqn (4).

$ \rho =1-6{\sum }_{}^{}{d}_{i}^{2}/n({n}^{2}-1) $ (4) where, di is the difference between the ranks of each pair of values, similarly, ρ values close to 1 or –1 signify a strong correlation, and values near 0 indicate no correlation. The value of t for the Spearman's rank correlation coefficient can be calculated by Eqn (5).

$ t=\rho \sqrt{n-2}/\sqrt{1-{\rho }^{2}} $ (5) -

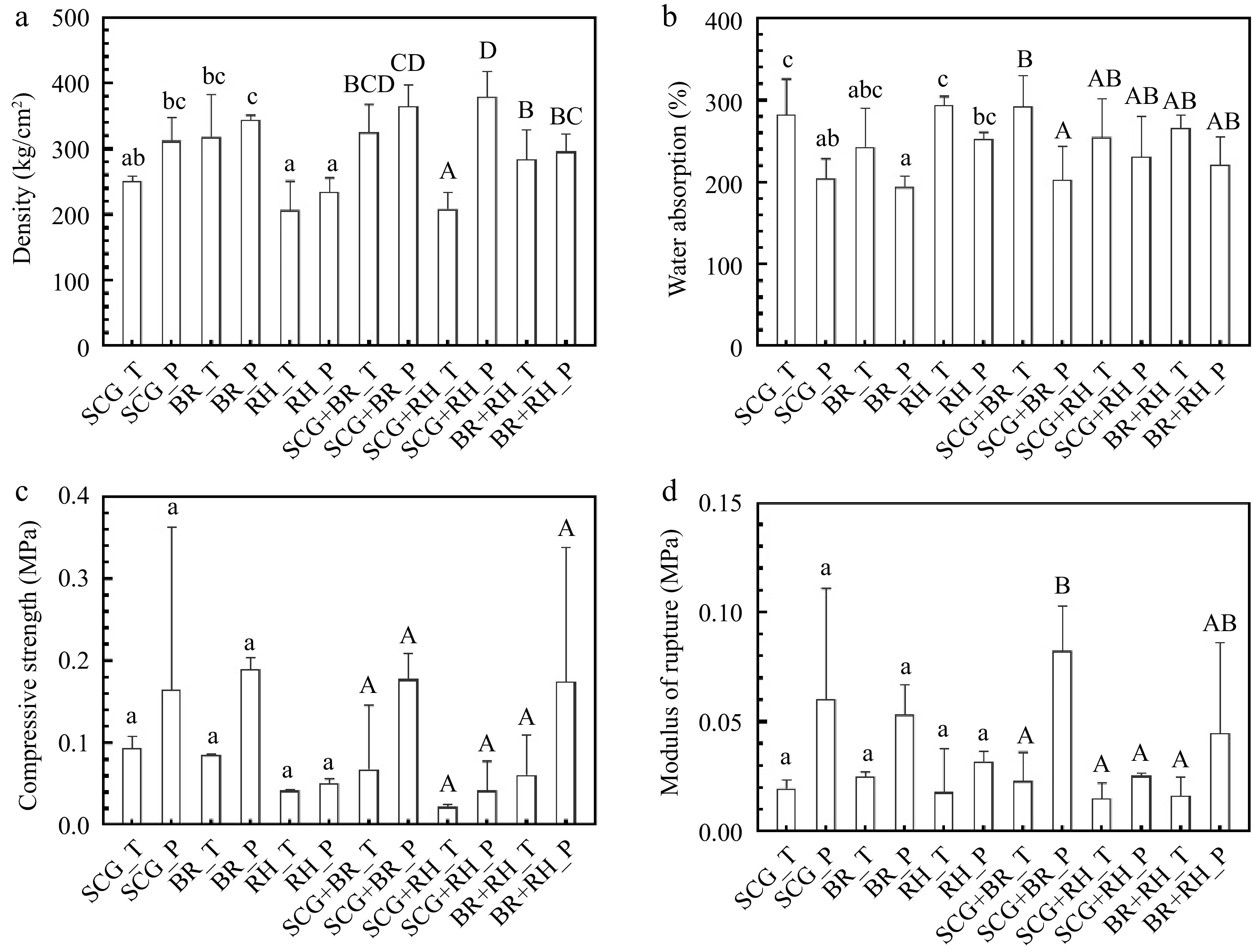

The compressive strength (MPa) of the mycelium-based biocomposites (MBBs) fabricated using Pleurotus ostreatus and Trichoderma virens with bamboo residues (BRs), spent coffee grounds (SCGs), and rice husks (RHs) was evaluated, as presented in Table 1 and illustrated in Figs 1 and 3. These results demonstrate the resistance of the samples to applied force. The highest compressive strength (Fig. 1c) was observed in BRs + P. ostreatus's Mycelium (0.190 MPa), followed by SCGs + BRs + P. ostreatus's Mycelium (0.177 MPa) and RHs + BRs + P. ostreatus MBBs (0.176 MPa). As detailed in Table 1, the average compressive strength of P. ostreatus MBBs derived from single substrates (100%) was 0.1353 MPa, and for 1:1 blended substrates (50%:50%), it was 0.1317 MPa. These values were higher than the corresponding averages for T. virens MBBs, which were 0.0737 MPa for single substrates and 0.0503 MPa for blended substrates. Our findings are consistent with previous research, which emphasizes that the compressive strength of MBBs is influenced by both the fungal species and the substrate type[7,43−45] (Table 2), as well as by other key factors such as fiber orientation and particle size, which influencing compressive behavior[46]. This study specifically observed variations in compressive strength based on different lignocellulosic residues, with most analyses focusing on P. ostreatus mycelium or closely related species within the genus Pleurotus[29,47−49] (Table 2).

Table 1. Summary of the properties of mycelium-based blocks examined in this study, highlighting the average density (kg/cm³), water absorption (%), compressive strength (MPa), and modulus of rupture (MPa). The data encompasses both the mean values and overall results for fungal mycelium cultivated on pure substrates (100%) and 1:1 blended substrate (50% substrate : 50% substrate). The table presents comprehensive measurements of density (kg/cm³), water absorption (%), compressive strength (MPa), and modulus of rupture (MPa).

Mycelium-based blocks/substrates Physical property Mechanical property Density

(kg/m³)Water

absorption (%)Compressive

strength (MPa)Modulus of

rupture (MPa)Individually (100%) mixed with fungal mycelium SCGs + Trichoderma virens 251.27 283.28(3rd) 0.094 0.020 SCGs + Pleurotus ostreatus 312.46 204.55 0.165 0.060(2nd) BRs + T. virens 318.64 243.50 0.085 0.025 BRs + P. ostreatus 344.84(3rd) 194.61Min 0.190Max (1st) 0.053(3rd) RHs + T. virens 206.70Min 294.25Max (1st) 0.042 0.018 RHs + P. ostreatus 234.84 253.11 0.051 0.032 The average data for T. virens mycelium obtained from individually (100%) substrate 258.87 273.68 0.0737 0.021 The average data for P. ostreatus mycelium obtained from individually (100%) substrate 297.38 217.42 0.1353 0.0483 1:1 blend (50% substrate : 50% substrate) combined with fungal mycelium RHs + BRs + T. virens 283.95 265.94 0.061 0.017 RHs + BRs + P. ostreatus 296.00 221.69 0.176(3rd) 0.045 RHs + SCGs + T. virens 209.00 255.28 0.022Min 0.015Min RHs + SCGs + P. ostreatus 379.00Max (1st) 231.80 0.042 0.025 SCGs + BRs + T. virens 325.00 292.58(2nd) 0.068 0.023 SCGs + BRs + P. ostreatus 365.82(2nd) 203.08 0.177(2nd) 0.082Max (1st) The average data for T. virens mycelium obtained from 1:1 blend

(50% substrate : 50% substrate)272.65 271.27 0.0503 0.0183 The average data for P. ostreatus mycelium obtained from 1:1 blend

(50% substrate : 50% substrate)346.94 218.86 0.1317 0.0507 Overall average data for T. virens mycelium obtained from both individually (100%) substrate and 1:1 blend (50% substrate : 50% substrate) 265.76 272.47 0.06 0.0197 Overall average data for P. ostreatus mycelium obtained from both individually (100%) substrate and 1:1 blend (50% substrate:50% substrate) 322.16 218.14 0.1335 0.0495 The results are reported as mean values for each substrate type. Within each column, the minimum values are highlighted in bold, and the maximum values are also denoted in bold. Additionally, the average values and overall averages are both bolded and underlined for emphasis. The rankings of the results in each property are noted as follows: 1st (maximum value) indicates the highest rank, 2nd the second highest, and 3rd the third highest.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for (a) density, (b) water absorption, (c) compressive strength, and (d) modulus of rupture for each determination. The columns with different letters are significantly different under Dunnett's T3 post hoc test at p < 0.05. T: Trichoderma sp., P: Pleurotus ostreatus.

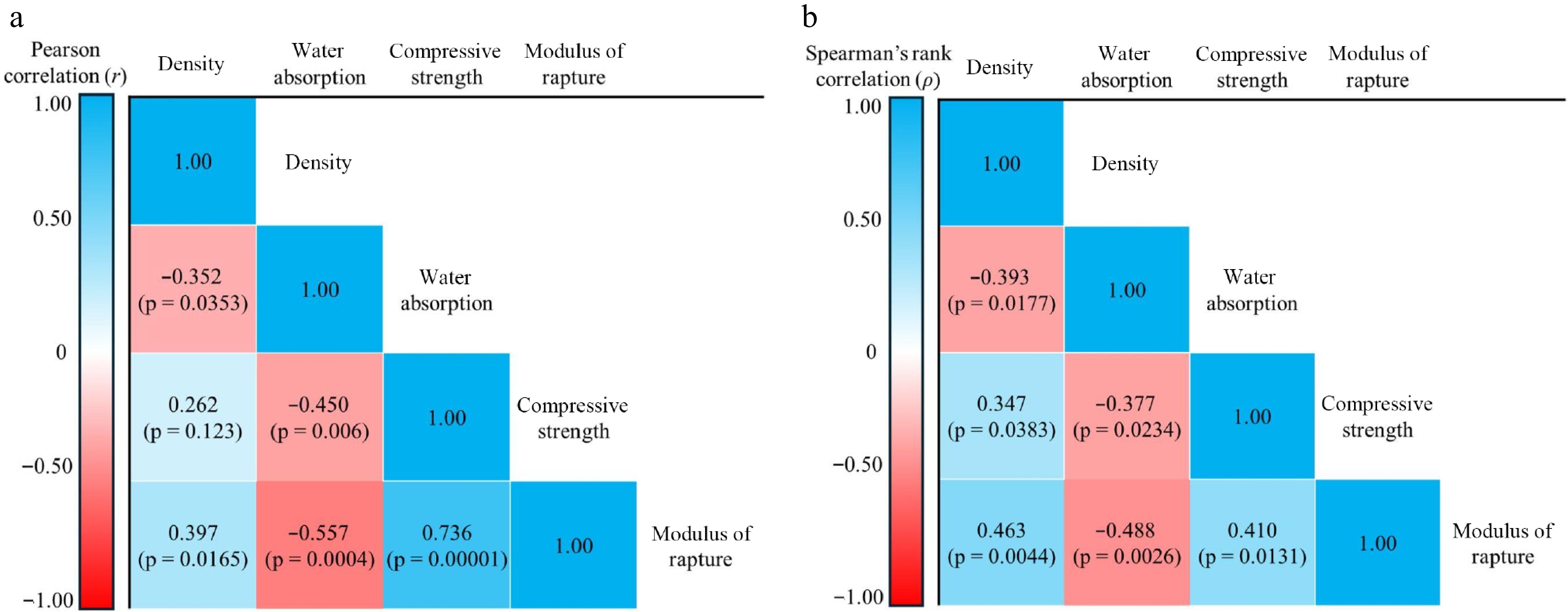

Figure 2.

Correlation analysis of density, water absorption, modulus of rupture, and compressive strength, evaluated using: (a) Pearson correlation, (b) Spearman's rank correlation.

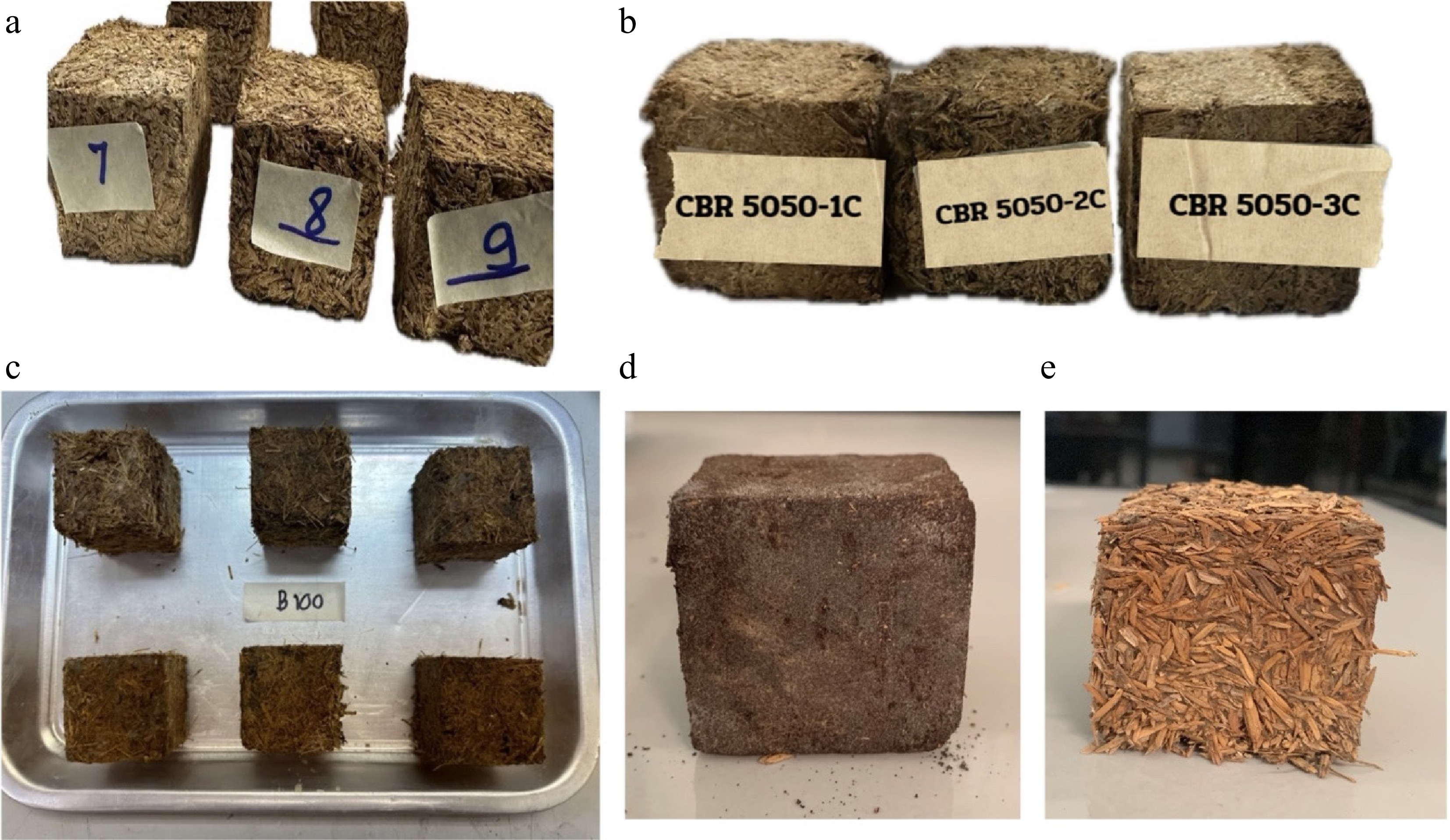

Figure 3.

Visual representation of mycelium-based block samples before testing, during testing, and after failure for modulus of rupture and compressive strength. (a) Test blocks for modulus of rupture prior to testing. (b) Test blocks for compressive strength prior to testing. (c) Samples after failure during modulus of rupture testing. (d) Samples during compressive strength testing.

Table 2. A comparison of the properties of MBBs from this study* with those reported between 2022 and 2024 in selected previous studies. These studies primarily utilized Pleurotus ostreatus mycelium or closely related species within the genus Pleurotus, incorporating substrates such as spent coffee grounds, bamboo residues, sawdust, or rice husks. The comparison evaluates four key parameters: 1) density, 2) water absorption (%), 3) compressive strength, and 4) modulus of rupture, with adaptations from Kohphaisansombat et al.[20].

Fungal taxa Substrate Density (kg/m3) Water absorption (%) Compression strength (Mpa) Modulus of

rupture (Mpa)Material properties# P. ostreatus and T. virens Bamboo residues, spent coffee grounds, rice husks 206.70−379.00 194.61−294.25 0.022−0.190 0.015−0.082 This study* P. ostreatus Spent coffee grounds, sawdust, pineapple fibres 280.00−360.00 99.96−114.30 1.65−2.92 0.20−0.48 Kohphaisansombat et al.[20] Lentinus sajor-caju, Ganoderma fornicatum, G. williamsianum, Trametes coccinea and Schizophyllum commune Bamboo, sawdust, corn pericarp 212.31−282.09 104.89−224.08 0.4−0.952 N/A Aiduang et al.[86] P. ostreatus Rubber wood sawdust N/A 122.39−134.15 N/A 0.72−1.57 Shakir et al.[13] P. sajor-caju Brewer's spent grains (fresh and dried) mixed with banana leaves 242.00 64.16−105.60 0.015−0.04 N/A do Nascimento Deschamps et al.[87] G. lucidum Spent coffee grounds, coffee chaff, sawdust, cereal waste 79.00−551.00 N/A 0.834−3.354 N/A Becze et al.[19] P. ostreatus Coffee silver, skin flakes N/A N/A 0.06−0.40 N/A Bonga et al.[88] Lentinus sajor-caju Corn husk, sawdust, paper waste 251.15−322.73 123.46−197.15 0.749−1.315 0.018−0.412 Teeraphantuvat et al.[85] P. ostreatus Bamboo fibers N/A N/A 0.05−0.25 N/A Gan et al.[50] P. ostreatus Rice husk, sawdust N/A 85.46−243.45 0.011−0.265 N/A Mbabali et al.[59] P. ostreatus Bamboo N/A N/A 0.14−0.45 N/A Soh et al.[12] P. florida Rice husk N/A 15.00−23.00 8.00−18.80 N/A Fahmy et al.[89] P. florida and P. citrinopileatus Rice husk, sawdust, sugarcane bagasse, teak leaves N/A 32.00−273.00 N/A N/A Majib et al.[90] P. ostreatus Rice husk, sawdust, sugarcane bagasse N/A N/A 0.277−1.350 N/A Nashiruddin et al.[55] L. squarrosulus and

L. polychrousCoconut husk, rice husk, rice straw N/A 229.08−609.00 0.46−0.54 N/A Ly & Jitjak[38] P. ostreatus Coffee husk, bagasse, sawdust 292.35−334.11 58.96−68.07 0.283−0.60533 N/A Alemu et al.[63] P. ostreatus Sawdust, rice husk, bagasse N/A N/A 0.08−12.37 N/A Sihombing et al.[29] N/A = Not Applicable or Not Available = information is currently unavailable or has not been provided. # Note: from minimum to maximum data or average overall study. The superior compressive strength of Pleurotus ostreatus MBBs compared to Trichoderma virens MBBs can be attributed to its denser and more robust mycelial network, better substrate integration, higher biomass yield, and stronger interaction with lignocellulosic substrates, particularly BRs[12,50]. The results from Pearson and Spearman's rank models in Fig. 2 also depict a low but positive correlation between density and compressive strength. Although the former model yielded an insignificant correlation at an R-value of 0.262, the latter showed a statistically significant correlation (p < 0.05) with the value ρ of 0.347. Due to its trimitic hyphal architecture and capacity to produce hydrophobic bio-adhesive compounds, Pleurotus ostreatus exhibits enhanced flexural strength relative to the monomitic species Trichoderma virens. This structural advantage contributes to the improved resistance of P. ostreatus-based composites against compressive loads[16,44].

In Table 1, the modulus of rupture (MOR) of Pleurotus ostreatus MBBs also surpassed that of Trichoderma virens derived MBBs, for both single substrates (100%) and 1:1 blended substrate (50%:50%). For instance, the average MOR for P. ostreatus MBBs from single substrates was 0.0483 MPa, compared to 0.021 MPa for T. virens MBBs (Table 1). The highest MOR (Fig. 1d) was recorded in MBBs produced from SCGs + BRs + P. ostreatus MBBs (0.082 MPa), followed by SCGs + P. ostreatus MBBs (0.060 MPa) and BRs + P. ostreatus MBBs (0.053 MPa). These MOR values fall within the range reported in previous studies, which spans from 0.018 to 1.57 MPa (Table 2). Notably, positive correlations were observed between the modulus of rupture and compressive strength, demonstrating consistent trends in mechanical performance across the samples (Figs 2 & 3). In fact, with an r of 0.737 (Fig. 2a), the Pearson model highly correlates the relationship between compressive strength and MOR (statistically significant at a p-value of 0.01). On the other hand, Spearman's rank correlation may underestimate the correlation (Fig. 2b) of these factors with ρ of 0.410. This might be due to the model being more suitable for monotonic data. Both statistical models also yielded a slight positive correlation between density and MOR.

Table 1 presents the overall mean compressive strength of P. ostreatus mycelium-based composites, derived from single (100%) substrates and a 1:1 substrate blend (50:50), 218.14 MPa. In contrast, the corresponding overall mean value for T. virens composites was 272.47 MPa. The water absorption behavior of mycelium-based biocomposites (MBBs) is governed by both the intrinsic properties of the substrates and the structural characteristics of the fungal species employed. As demonstrated in Fig. 1b and Table 1, variations in water absorption capacity can be attributed primarily to the hygroscopic nature of lignocellulosic substrates, which inherently differ in their porosity, fiber composition, and surface chemistry. Substrates with higher cellulose and hemicellulose content typically exhibit greater affinity for moisture, thereby contributing to increased water uptake in the resulting composites[51−53].

Furthermore, the fungal species used in fabrication plays a critical role in modulating water absorption. The Pleurotus ostreatus, characterized by its trimitic hyphal system, tends to produce a denser and more compact mycelial matrix, possibly limiting water permeability. In contrast, Trichoderma virens, possessing a monomitic hyphal system, often result in a looser, less interwoven structure that can facilitate higher water ingress. The extent of mycelial infiltration and bonding with the substrate matrix also influences moisture retention, as denser hyphal networks can occlude capillary pores and reduce water penetration.

The highest water absorption was observed in RHs + T. virens MBBs (294.25%), while the lowest was recorded for BRs + P. ostreatus MBBs (194.61%). Notably, those made with T. virens MBBs exhibited significantly higher average water absorption rates than composites made with P. ostreatus MBBs, indicating a greater tendency for water uptake in MBBs formed with T. virens (Fig. 1b, Tables 1 & 2).

Composites made with T. virens demonstrated significantly higher water absorption rates, likely due to the more open and porous structure formed by its monomitic hyphal system. This loose hyphal network increases capillary pathways, facilitating greater water uptake. Additionally, the cell wall composition of T. virens may contain more hydrophilic components, contributing to its higher affinity for moisture. In contrast, P. ostreatus, with its denser trimitic hyphal structure, forms more compact composites that limit water penetration. These differences underscore the influence of fungal morphology and composition on moisture retention behavior in MBBs. Additionally, the interaction between T. virens and RHs resulted in the highest recorded water absorption rate of 294.25%, highlighting its capacity to enhance the moisture-retentive properties of hygroscopic materials[54]. Furthermore, T. virens lacks the dense mycelial networks characteristic relative to mushroom-based fungi like P. ostreatus, which restrict water uptake[55]. This structural distinction likely contributes to the higher overall water absorption observed in composites containing T. virens.

In addition to the fungal species used, the water absorption ability of MBBs in this study was likely influenced by the cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content of each substrate, as previously reported[54,56,57]. Rice husks demonstrated intermediate water absorption properties with their silica-rich outer layer and moderate cellulose content[58,59]. The presence of silica may create a microstructure conducive to water retention, particularly when combined with T. virens, which appears to enhance water uptake. This observation emphasizes the significant role of substrate composition in determining the water absorption performance of MBBs. The interaction between T. virens mycelium and the specific chemical and structural properties of rice husks likely contributes to their synergistic effect on water absorption, providing insights into tailoring MBB properties through substrate selection for desired applications.

The density values of the MBBs obtained in this study are presented in Fig. 1a and Table 1. The measured density values ranged from 198.84 to 340.31 kg/m³. The highest density was observed in MBBs produced from a combination of RHs + SCGs + P. ostreatus MBBs (379.00 kg/m³), followed by SCGs + BRs + P. ostreatus MBBs, and BRs + P. ostreatus MBBs, with values of 365.82 and 344.84 kg/m³, respectively. As shown in Table 1, the average and overall average density data for P. ostreatus MBBs, derived from both single substrates (100%) and blended substrates (50%:50%), were higher than the corresponding averages for T. virens MBBs under the same conditions. This indicates that P. ostreatus mycelium generally produces denser MBBs, reflecting its superior binding and structural properties.

Our study observed an inverse relationship between water absorption capacity and density, where water absorption decreased as the degree of density increased. This is confirmed by the negative r (Fig. 2a) and ρ (Fig. 2b), with both values being statistically significant at a p-value of 0.05. This finding aligns closely with the results of several previous studies, which similarly reported that higher-density MBBs exhibited reduced water absorption capacity due to their compact structure[60−62]. This study also aligns with previous research, which emphasizes that the density values of MBBs, particularly those utilizing P. ostreatus MBBs, fall within a similar range. For example, Kohphaisansombat et al.[20] reported comparable density values in MBBs made with P. ostreatus combined with SCGs, sawdust, and pineapple fibers, while Alemu et al.[63] observed similar results using P. ostreatus with coffee husks, bagasse, and sawdust, as presented in Table 2.

Mycelium-based blocks hold great promise as sustainable materials; however, certain limitations, including water resistance, contamination, inconsistent growth, inadequate moisture levels, unsuitable pH, and improper substrate preparation, require further research and optimization[44,53,64]. A notable concern is the elevated water absorption observed in specific substrate blends, particularly RH-based MBBs combined with T. virens mycelium. Unlike the robust mycelial networks formed by mushroom-based fungi, T. virens exhibits weaker structural properties, which can compromise the integrity and durability of composites in humid environments.

Hyphal binding, driven by the growth and intertwining of fungal hyphae within lignocellulosic substrates, is crucial in forming mycelium-based blocks (MBBs). Hyphae penetrate and colonize substrates by secreting enzymes and bio-adhesive compounds, establishing strong inter-particle bonds and forming a robust structural matrix essential for composite integrity and durability[6,65]. Specifically, Pleurotus ostreatus, characterized by a dimitic or trimitic hyphal system, develops dense, compact networks that substantially enhance mechanical strength and limit water permeability[66]. In contrast, Trichoderma virens, possessing a monomitic hyphal structure, produce more porous and hydrophilic composites, influencing mechanical performance and moisture retention[67]. Understanding these distinct hyphal binding mechanisms informs optimal selection of fungal species and substrates, crucially advancing the development of sustainable, high-performance mycelium-based materials (Fig. 4).

Future research should focus on refining substrate formulations and exploring functional additives to improve water resistance, fire retardancy, and mechanical performance. Mitigation strategies may include the application of bio-based hydrophobic coatings and modifications to substrate composition, such as incorporating hydrophobic additives such as beeswax or coconut oil additions[68,69], and lignin/tannin/ZnONP composite coatings[70]. These approaches aim to enhance water resistance without compromising the eco-friendly attributes of the blocks.

The adaptability of MBBs enables customization of their properties to meet specific application needs by selecting appropriate substrates. For instance, bamboo residue-reinforced MBCs, combined with mushroom mycelium and recognized for their exceptional compressive strength, are ideal for applications requiring enhanced durability[50,71−73].

Scaling up the production of MBBs using P. ostreatus mycelium presents additional challenges, particularly in maintaining uniformity in material properties and optimizing growth conditions for consistent mycelial colonization[74]. Furthermore, utilizing MBBs as load-bearing structural elements in architecture highlight opportunities and directions for future research, mainly through digital methods[75]. Comprehensive physical and chemical characterization, as well as the incorporation of reinforcements or the development of multi-component (e.g., triple or higher) composite systems, could further enhance the functionality of MBBs[73,76]. Long-term durability studies under diverse environmental conditions are also essential for their broader adoption, such as fracture behavior and toughening mechanisms[77], and their long-term commercial success and applicability[78]. A multidisciplinary approach combining genetic engineering, mutagenesis, experimental evolution, computational modeling, and AI-driven machine learning for predicting material functions can effectively address strain development challenges in established and emerging industries, including low yields, suboptimal feedstock adaptation, and downstream purification inefficiencies[79,80].

To unlock the full potential of MBBs, investigations should include their thermal and acoustic insulation properties, alongside the life cycle assessments[72,81−83] to quantify their environmental advantages over traditional materials. Incorporating recycled industrial byproducts, such as paper waste or seashells, represents a promising avenue for improving sustainability and material performance[84,85]. By addressing these challenges and opportunities, MBBs can be advanced into a versatile, environmentally sustainable alternative for various construction and industrial applications. In the case of MBBs, those formed with T. virens exhibited distinct structural characteristics but demonstrated lower mechanical properties than P. ostreatus. Previous studies have identified T. asperellum as having a monomitic mycelial structure, with findings indicating that MBCs derived from this species were hydrophobic and mechanically robust, particularly when cultivated on rapeseed cake[62]. Certain Trichoderma species have also shown promise in bio-based self-healing concrete applications, further supporting their potential role in sustainable material development[91,92]. Although Trichoderma is commonly recognized as an air-contaminating agent during production, it also plays a dual role in material formation and potential bio-deterioration, necessitating a careful balance in optimizing its use in MBCs[93,94]. Furthermore, its integration with non-lignocellulosic materials such as concrete presents an opportunity to mitigate degradation while enhancing self-healing properties, offering promising applications in sustainable construction materials[91,92,94].

-

This study highlights the promising potential of mycelium-based blocks (MBBs) fabricated with Pleurotus ostreatus as sustainable and eco-friendly alternatives for non-load-bearing construction applications. By utilizing lignocellulosic residues—specifically bamboo residues (BRs), spent coffee grounds (SCGs), and rice husks (RHs)—as substrates, MBBs demonstrated superior mechanical and physical performance compared to those produced with Trichoderma virens. The optimal combination of BRs and P. ostreatus mycelium achieved the highest compressive strength, while a mixture of RHs and SCGs with P. ostreatus resulted in the highest material density. Conversely, blocks produced with T. virens exhibited greater water absorption, particularly in RH-based composites, reflecting the hygroscopic nature of its mycelial structure.

These findings underscore the advantages of P. ostreatus as a high-performance myco-binder, attributed to its dense, well-structured hyphal network and strong binding efficiency. Moreover, the study demonstrates that substrate composition is critical in shaping key material properties such as density, water absorption, and compressive strength. Overall, the results affirm the viability of MBBs as sustainable alternatives to conventional materials, supporting circular economy principles and reducing dependence on non-renewable resources. Future research should aim to optimize fabrication parameters further, improve durability, and expand potential applications of MBBs across various bio-based industries.

Figure 4.

Visual depiction of selected mycelium-based blocks developed using Trichoderma virens. (a) Dried blocks composed of 50% spent coffee grounds (SCGs) and 50% bamboo residues (BRs). (b) Dried blocks cultivated from a mixed substrate of 50% SCGs and 50% rice husks (RHs). (c) Dried blocks made entirely from bamboo residues (100% BRs). (d) Dried blocks produced solely from spent coffee grounds (100% SCGs). (e) Dried blocks fabricated entirely from rice husks (100% RHs).

This research was funded by the Budget Bureau and NSTDA under project code PG2400015, as well as the Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) through the Fundamental Fund: FF68 (P2451576). Nattawut Boonyuen sincerely acknowledges BIOTEC-NSTDA (Project Nos P2450748, P2451951, and P2451576) for their partial financial support of the manuscript. This research also received partial funding from the Faculty of Environment and Resource Studies, Mahidol University (SeedGrant No. 01-2567), and from Grant No. RGNS 65-157, provided by the Office of the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research, and Innovation (OPS MHESI) and TSRI. Yuwei Hu would like to acknowledge the Department of Science and Technology of Yunnan, China (Grant No: 202303AP14000). Apai Benchaphong expresses deep gratitude to the Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Rajamangala University of Technology Krungthep, for their support, as well as to colleagues and students: Jirakrit Thongpenee, Thanakrit Saengphan, Thanaphongphan Bunpong, Natthicha Kinburan, Paornrat Pluemsoot, Pornpan Jutawantana, Chatchai Sangdee, Thanabat Boonmeejew, and Aeksin Nakpradit, for their valuable contributions. The authors also appreciate the editorial team and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions, which significantly improved the manuscript.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: validation: Benchaphong A, Phanthuwongpakdee J, Chuaseeharonnachai C, Koedrith P, Dueramae S, Thongraksa A, Hu Y, Wattanavichean N, Boonyuen N; supervision, conceptualization: Benchaphong A, Boonyuen N; methodology: Phanthuwongpakdee J, Kwantong P, Nuankaew S, Somrithipol S; formal analysis, data curation: Phanthuwongpakdee J, Boonyuen N; resources: Kwantong P, Nuankaew S, Chuaseeharonnachai C; writing - original draft preparation, review & editing: Koedrith P, Boonyuen N, Wattanavichean N; formal analysis, project administration: Boonyuen N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

The data supporting this study's findings are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Benchaphong A, Phanthuwongpakdee J, Kwantong P, Nuankaew S, Chuaseeharonnachai C, et al. 2025. Assessing mycelium-based blocks utilizing Pleurotus ostreatus versus Trichoderma virens: material characterization and substrate ratios of bamboo residues, spent coffee grounds, and rice husks. Studies in Fungi 10: e007 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0007

Assessing mycelium-based blocks utilizing Pleurotus ostreatus versus Trichoderma virens: material characterization and substrate ratios of bamboo residues, spent coffee grounds, and rice husks

- Received: 05 January 2025

- Revised: 12 March 2025

- Accepted: 09 April 2025

- Published online: 21 May 2025

Abstract: Mycelium-based blocks (MBBs) represent an innovative and eco-friendly approach to composite material design, combining fungal mycelium with lignocellulosic biomass to produce sustainable, rapidly regenerating materials with intrinsic hydrophobic properties. This study investigates the fabrication and characterization of MBBs using Pleurotus ostreatus (Basidiomycota) as the mycelial binding agent and compares its performance with Trichoderma virens (Ascomycota), a non-mushroom mycelial alternative. The performance of both fungal species was assessed using three lignocellulosic substrates: bamboo residues (BRs), spent coffee grounds (SCGs), and rice husks (RHs). Substrates were evaluated individually (100% BRs, SCGs, or RHs) and in binary mixtures at a 50:50 ratio (BRs:SCGs, BRs:RHs, and SCGs:RHs). The physical and mechanical properties—including density, water absorption, compressive strength, and modulus of rupture—were systematically evaluated. Results demonstrated that MBBs composed of BRs and P. ostreatus mycelium achieved the highest average compressive strength (0.190 MPa), outperforming T. virens-based blocks and other MBB formulations. Additionally, blocks incorporating RHs, SCGs, and P. ostreatus exhibited the highest density, reaching 379 kg/m³. In contrast, RH-based blocks with T. virens mycelium showed the highest water absorption, at 294.25%. Overall, MBBs utilizing P. ostreatus mycelium outperformed those with T. virens in key metrics such as density, compressive strength, and modulus of rupture, though water absorption was a notable exception. These findings underscore the potential of MBBs—particularly those incorporating SCGs, BRs, and RHs—as sustainable, non-load-bearing construction materials. Their reduced reliance on conventional resources highlights their promise as eco-friendly alternatives for sustainable applications.