-

Tropical rainforests harbor a higher richness of species, housing approximately half of all vascular plant species found worldwide[1]. Plant communities within these forests are highly dependent on their diverse microbiota, including essential components such as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF)[2], which are crucial organisms for maintaining soil structure, decomposition of organic matter, improvement of soil fertility, and nutrient availability[3,4].

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) play an important role in establishing a symbiotic association with plant roots in 80% of terrestrial plant species being ubiquitous in tropical forests[5−8]. This mutualistic relationship benefits the growth and survival of trees by enhancing their rates of water nutrient uptake and offers different effects on their fitness[9−11]; while at ecosystem level contributes to proper functioning, nutrient uptake, and maintenance for forestry systems[7,12,13]. Numerous studies have highlighted the importance of AMF colonization in facilitating nutrient absorption and promoting tree growth[6], improving phosphorus acquisition in tree seedlings[7], and positively influencs nitrogen acquisition[8].

In general, AMFs play an important role in the growth and survival of trees in Andean montane forests[14], particularly in nutrient-poor soils where phosphorus supply is often limited[15]. In this region, the colonization of AMF trees extends the effective root surface area of trees to facilitate the nutrient absorption from the soil, such as phosphorus (P), nitrogen (N), and potassium (K), through their extensive hyphal networks[16,17]. This mutualistic relationship allows trees to adapt to the challenging environmental conditions of Andean montane forests and to remain in nutrient-limited soils. The diversity of AMF in the Andean region depends on the environmental conditions found in the soil of different forest types along different elevational gradients[8]. In addition to altitude, other driving factors such as temperature, precipitation, and pH are key for the establishment, colonization, and permanence of AMF in the rhizosphere of tree species[18,19]. Even though climatic conditions may influence mycorrhization density, one of the principal factors determining the establishment of AMF can be attributed to the soil components, such as the presence of carbon, nitrogen, and flux of low-mobility nutrients such as P, K, calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), copper (Cu), among others[9,20], as well as soil pH, which is an important determinant both for host plants and for the structuring of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi communities, since it promotes the extension of extra-radical mycelia, thus structuring the fungus niche[9].

Despite the importance of these interactions, few studies have assessed the colonization of AMF in tree montane species[18,21]. In the Andes, Cedrela montana is a montane species distributed along the different elevational gradients[22]. Cedrela is a genus known for its highly valuable timber, and have suffered significant genetic degradation in Ecuador due to extensive overharvesting and selective logging. Currently, this species is restricted to the Ecuadorian highlands, specifically within the western and eastern Andean montane regions[22]. Understanding the colonization rates of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) in the roots of Cedrela montana, and how these rates vary along elevational gradients in relation to soil conditions, is crucial for comprehending the ecological role of AMF in the establishment of this tree species in montane forest communities. Additionally, AMF are gaining increasing attention for their potential applications in sustainable reforestation with this tree species.

The aim of this research was to evaluate the effect of elevation and soil chemical conditions on: 1) the AMF spore abundance in the soil; and 2) AMF colonization intensity on the rhizhosphere of C. montana along an elevational gradient.

-

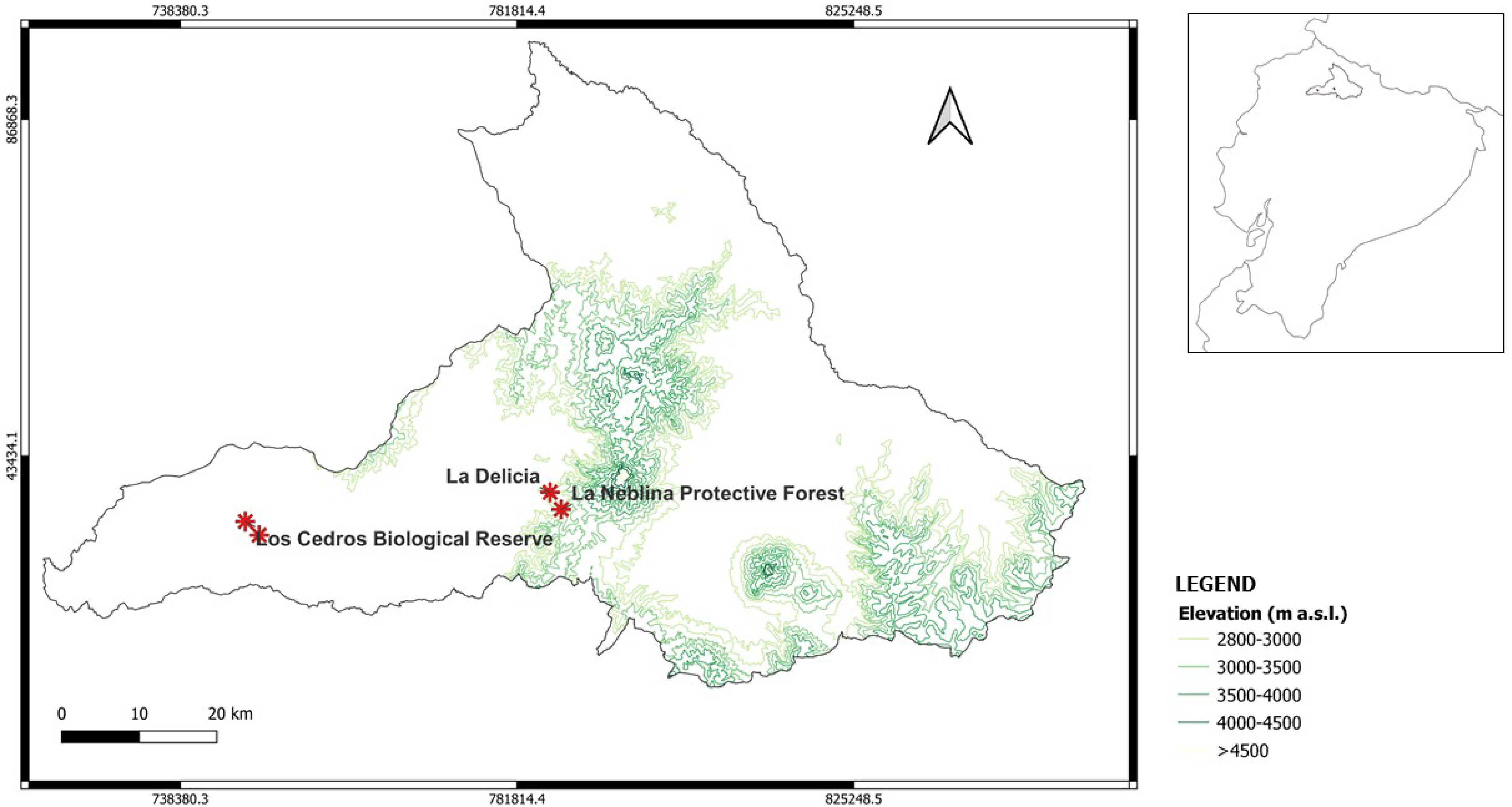

Samples were collected from four localities near the Cotacachi Cayapas National Park, located within the Andean Chocó biogeographic region in Imbabura province, Ecuador. Due to the sporadic distribution of Cedrela montana (cedar) in the wild, three individuals were selected at each sampling elevational point. To enhance the representativeness of the data, the sampling design included collecting samples from three distinct random points around each tree. This approach ensured that our assessment improved the robustness of the sampling of the rhizosphere micro-community. The sampling points were as follows: (i) Los Cedros Biological Reserve (0°18' N, 78°46' W, ~1,500 m a.s.l.; 0°19' N, 78°47' W, ~2,000 m a.s.l.), (ii) La Delicia (0°21' N, 78°26' W, ~2,500 m a.s.l.), and (iii) La Neblina Protective Forest (0°20' N, 78°25' W, ~3,000 m a.s.l.) (Fig. 1). An auger was used to dig a 20 cm deep hole at three equidistant points from each tree. Around each cedar, up to one-meter diameter was left to ease the collection of soil and fine roots. The collected samples were placed in hermetic bags and stored at 4 °C until laboratory analysis.

Figure 1.

Site description of sampling points. Los Cedros Biological Reserve, La Delicia, and La Neblina Protective Forest; around 1,500, 2,000, 2,500, and 3,000 m a.s.l., respectively.

Quantitation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal spores

-

A quantitative analysis of the abundance of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal spores associated with the collected soils was carried out using the sieving and decantation method, in accordance with the International Culture Collection of (Vesicular) Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi of West Virginia University (INVAM) with some modifications. Briefly, 100 g of fresh rhizosphere soil sample were disaggregated in 1:1 of water (weigth/volume) and then decanted. The supernatant was passed through 710, 150, and 45 μm sieves. Retained spores from the 45 μm sieve were suspended in a sucrose solution (60% w/v) and immediately centrifuged at 2,500 rpm for 3 min at 22 °C (SL40R Thermo Scientific). Spores were collected from the supernatant, placed in a Petri dish, and quantified under a stereo microscope (Leica, EZ4). Results were expressed in number of AMF spores per 100 g of sample[23].

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonization analysis

-

Collected roots from each tree were analyzed using a staining technique for arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi as described below. Frequency and intensity were determined in four replicates for each sample. Therefore, the percentage of roots that showed AMF internal colonization was determined as previously described by Trouvelot[24]. In brief, roots were washed with tap water and kept in 10% KOH for 3 d. Subsequently, the roots were placed in 3% H2O2 for 1 min, washed with tap water, and immersed in 1% HCl for 6 min. Excess HCl was removed, and the roots were stained in 0.05% trypan blue. Finally, the sample with the dye was heated to 100 °C for 5 min. For each tree, ten stained roots of 1 cm in length were placed on six slides with 0.5 mL lactoglycerol and analyzed under a microscope (Olympus, BX53). The results were expressed as the frequency of mycorrhization. The same procedure was used to set up the intensity of mycorrhization. Thus, on each slide, the average percentage of arbuscules, hyphae, and vesicles were quantified[24].

Chemical soil analysis

-

Soil chemical analysis was carried out with reference to the laboratories of the National Institute of Agricultural Research (INIAP) following standard methodologies as: 1) electrometric determination of pH using a pH meter that measures the potential difference between the two electrodes, which is related to the hydrogen ion concentration; 2) Walkley-Black method for soil organic matter (SOM) which oxidizes soil organic carbon with potassium dichromate and sulfuric acid, then titrate the remaining dichromate with ferrous sulfate to estimate SOM; 3) semi-micro-Kjeldahl method for organic nitrogen (N) which determines organic N by digesting a sample with sulfuric acid, converting N to ammonium, this is then distilled and titrated with a standard acid to quantify N content; and 4) atomic absorption spectrophotometry (ASS) for quantitation of P and K by measuring light absorption at specific wavelengths, P is released from the sample through acid digestion, while K is atomized in the AAS flame[25].

Statistical analysis

-

Initially, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed with the predictor variables elevation and all soil chemical parameters to explore their relationships and identify those with less multicollinearity. Based on the results, elevation, N, P, and SOM exhibited the strongest correlations with principal components PC1 and K and pH with PC2 (r < 0.7, Pearson's correlation coefficient). Ca and Mg were not selected because of the high correlation they have with the K element, other studies showed the same pattern[26] (Supplementary Fig. S1, Fig. 1).

Because of its robust and interpretable approach for determine the relationship between variables, given the nature of our data, separate linear regressions were carried out to relate response and predictor variables as follows: 1) spores mean (spore abundance) and elevation; 2) spores mean and SOM, pH, N, P, and K. Likewise, a general linear model was employed to analyze the relationship between the response variables that representing AMF colonization intensity (total frequency, total intensity, arbuscule intensity, vesicle intensity, and hypha intensity), and the predictor variables: SOM, pH, N, P, and K. We evaluated the fulfillment of the four assumptions to use linear regression models: the linearity of residuals, normality, independence, and homoscedasticity. All statistical analyses were performed using software R 3.6.2 for Windows[27].

-

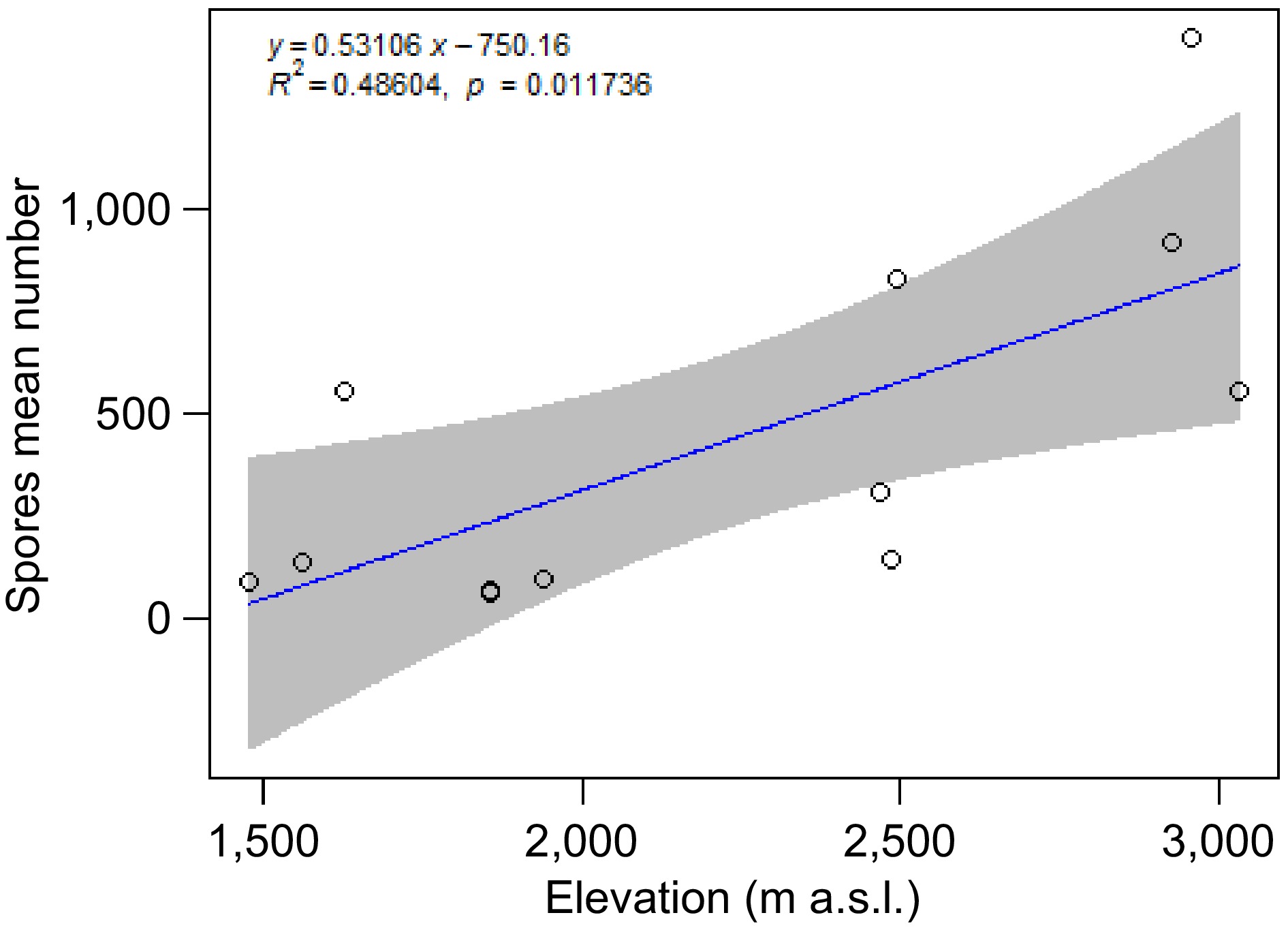

We found a mean of 1,703 spores in 100 g of soil from the rhizosphere of each individual of Cedrela montana sampled along of the elevational gradient. The sampling points with higher number of spores were in the upper mountain > 2,000 spores. Statistically significant correlation was found between spore mean number and elevation. Higher elevations showed an increase in the spore mean number (Table 1, Fig. 2). No statistically significant correlation (p > 0.05) was found between the spore mean number and SOM, N, and P concentrations.

Table 1. Statistical summary of the general linear model results for spore mean number, from the rhizosphere of 12 sampled trees of Cedrela montana, and elevation, SOM, N, K, P, and pH.

Spore mean number R2 E p Elevation 0.486 0.9152 0.0117 * SOM 0.105 −81.34 0.305 N 0.137 12.112 0.237 K 0.591 1140.8 0.004 ** P 0.003 −6.692 0.875 pH 0.678 926.8 0.0001*** R2: proportion of variance explained; E: estimated effect size; p: p-value indicating statistical significance (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Linear regression correlating spore mean number with elevation, from the rhizosphere of Cedrela montana roots. The regression line (blue) shows a positive trend, with the shaded gray area around the line representing the 95% confidence interval (the equation of the regression line is displayed at the top of the graph).

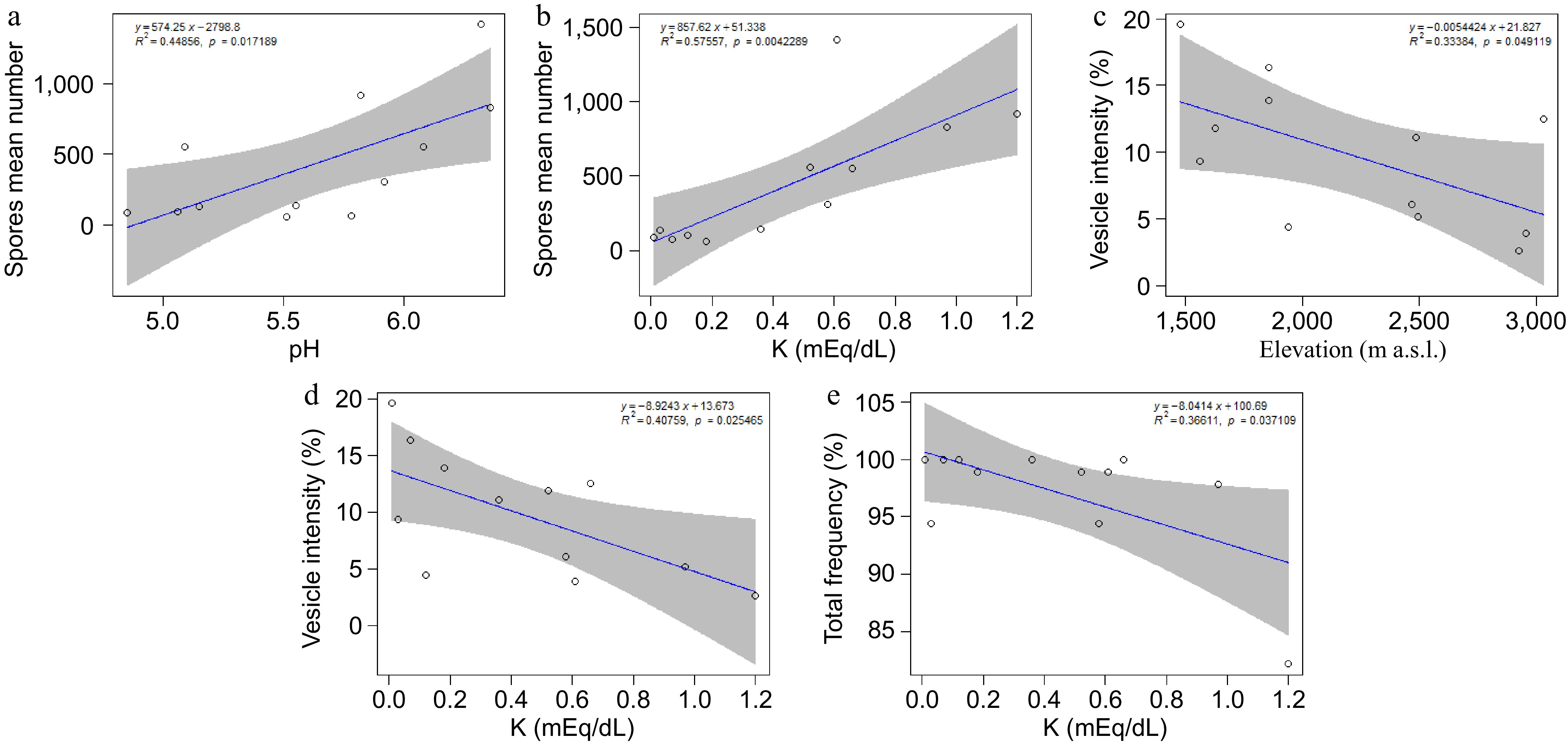

There was a positive significant linear correlation between spore mean number and pH (p < 0.001), showing an increase in the number of spores at pH values around 6−7 in the rhizosphere soil of each tree in comparison to lower pH values (Table 1, Fig. 3a). Similar significant positive linear correlation was found between spore mean number and soil K concentration (Table 1, Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Linear regressions with positive trends: (a) spore mean number with pH, and (b) spore mean number with K. Negative trends are observed for (c) vesicle intensity with elevation, (d) vesicle intensity with K, and (e) total frequency with K, from the rhizosphere of Cedrela montana. Regression lines (blue) are shown with shaded gray areas representing 95% confidence intervals (the equation of the regression line is displayed at the top of the graph).

AMF colonization intensity

-

There was a negative significant correlation between vesicle intensity and elevation (Table 2, Fig. 3c), and between vesicle intensity and K concentration (Table 2, Fig. 3d). Lower values of soil altitude or K concentration were associated with high values of the vesicle intensity in Cedrela montana roots. Also, the total frequency of mycorrhization showed a negative significant correlation with soil K, the percentage of the total frequency of mycorrhization increased in conditions of lower K concentration (Table 2, Fig. 3e). Total intensity, arbuscule intensity, and hypha intensity did not show significant evidence with any predictor variables (Table 2).

Table 2. Statistical summary of the general linear model results for total frequency, total intensity, arbuscule intensity, vesicle intensity, and hypha intensity from the rhizosphere of 12 sampled trees of Cedrela montana, and elevation (Ele), SOM, N, K, P, and pH.

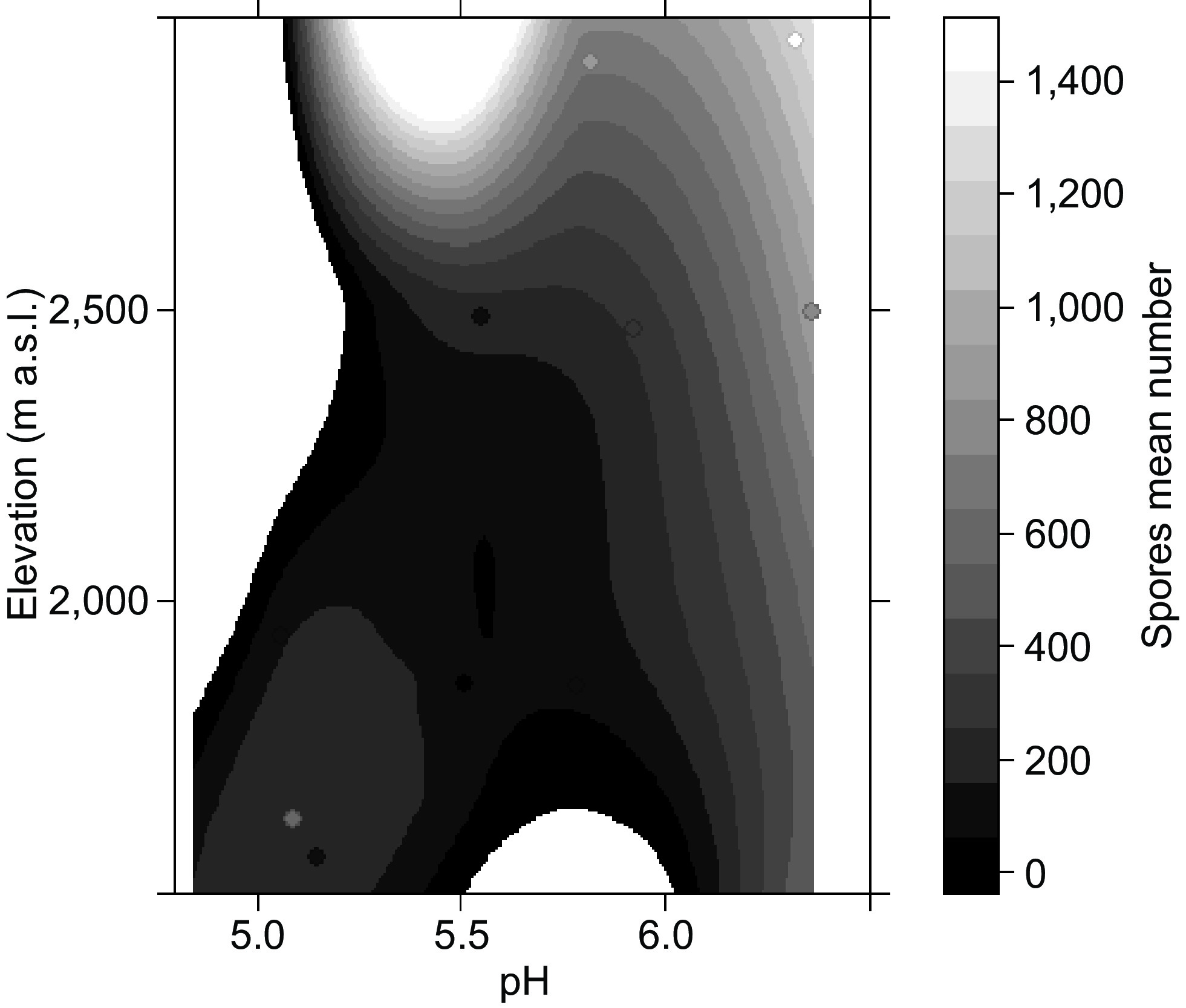

Total frequency Total intensity Arbuscule intensity Vesicle intensity Hypha intensity R2 E p R2 E p R2 E p R2 E p R2 E p Ele 0.117 −0.003 0.277 0.069 −0.003 0.412 0.085 −0.0003 0.358 0.341 −0.007 0.046* 0.008 −0.001 0.782 SOM 0.11 0.747 0.292 0.041 −0.468 0.526 0.001 0.003 0.940 0.060 −0.581 0.441 0.046 −0.523 0.500 N 0.024 −0.041 0.658 0.024 −0.047 0.625 0.003 −0.001 0.851 0.070 −0.082 0.403 0.009 −0.030 0.762 K 0.366 −8.041 0.037* 0.243 −6.713 0.103 0.253 −0.433 0.095 0.407 −8.924 0.025* 0.136 −5.293 0.237 P 0.041 0.239 0.527 0.308 0.211 0.585 0.022 −0.011 0.641 0.022 0.186 0.641 0.046 0.272 0.503 pH 0.021 −1.477 0.649 0.014 −1.224 0.714 0.172 −0.271 0.179 0.208 −4.840 0.136 0.002 0.500 0.887 R2: proportion of variance explained; E: estimated effect size; p: p-value indicating statistical significance (* p < 0.05). The interactions between elevation with pH and spores mean number showed that the abundance of spores tends to increase in the rhizosphere of trees located in highlands at pH values of 6−7 (R2: 0.7315, E: 1.021, p: 0.0345, Fig. 4). While the significant interaction between elevation with P with abundance of spores showed that the highest of number of spores was found in the rhizosphere of trees of C. montana at lower elevations with low P concentrations (R2: 0.6561, E: −9.761e-02, p: 0.089, Table 1).

-

Our results show that along elevational gradients in Andean regions, there is a significant relationship between the altitudinal variation and both the abundance of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi spores and their colonization intensity on the rhizosphere of Cedrela montana.

This correlation appears to be influenced by the prevailing chemical properties of the soil where individuals of this forest species are established. The presence of a higher number of AMF spores in 100 g of soil from C. montana may be due to the environmental characteristics of montane forests, such as high rainfall, low annual temperature variations, and high plant community diversity[8]. In these regions, despite prior research highlighting a negative correlation between the abundance of arbuscular mycorrhizal spores and elevation[19,21,28–30], other works have reported non-significant relationships between these variables[31]. Furthermore, some investigations have found no clear altitudinal pattern in AMF spore distribution in tropical montane forests[8]. These inconsistencies have been attributed to the high variability of microclimatic conditions and soil properties across elevations, which significantly influence AMF diversity[8,32].

Our research reveals a significant pattern with an increase in the average number of mycorrhizal spores in the rhizosphere soil of C. montana with the increasing elevational gradient. This trend may reflect a greater dependence of this forest species on AMF at higher elevations. In these environments, plants face greater environmental stress, including lower temperatures and reduced nutrient availability, which limits the capacity of their roots to acquire nutrients independently. As a result, they rely more heavily on mycorrhizal structures to access nutrients with lower mobility, such as phosphorus[17,20]. Generally, tropical and subtropical trees are highly dependent on mycorrhizal symbiosis due to the low phosphorus availability in soils[16,33]. AMF colonization in tree species of Andean montane forests improved phosphorus acquisition, a vital nutrient that frequently limits plant growth in poor soils in nutrients, such as those found at higher elevations[34].

A multifactorial explanation for the relationship between soil conditions and the distribution of AMF spores along elevational gradients may involve several drivers, including soil pH, and soil fertility[19]. In fact, in our study, the highest mycorrhizal spores count was found at pH around 6.0 at 3,000 m a.s.l. in comparison to the values found at lower elevations (pH < 5.5). Previous works have described how this edaphic parameter may influence the mycorrhizal colonization and abundance of these fungi[15,35]. According to Ma et al.[36], the soil pH is a key predictor of the global distribution of AMF abundance. This relationship may be linked to the availability of inorganic phosphorus, which is most accessible at a soil pH of around 6.5. At both lower and higher pH levels, inorganic phosphorus availability is restricted. Additionally, localized changes in rhizosphere pH can further influence the accessibility of these phosphorus sources[17]. Moreover, soil pH is a critical factor due to its essential role in promoting the extension of AMF extra-radical mycelia[9].

Additionally, soil nutrient composition influences the establishment of the association between mycorrhizal fungi and the plant species[37,38], as well as the development of the fungal structures and colonization intensity on C. montana roots. We found a significant correlation between potassium concentration and the presence of higher vesicle numbers in the rhizosphere of C. montana in lowlands. These findings suggest that vesicles may serve as important reserve structures for potassium in the rhizosphere of this forest species in such environments. Vesicles are resting organs[17] capable of accumulating organic compounds and elements such as phosphorus, calcium, sulfur, silicon, and potassium[39]. In lowlands, possibly the typical higher nutrient competition and faster decomposition rates may limit the immediate availability of nutrients. Under these conditions, arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi can absorb non-mobile nutrients from the soil and rapidly translocate them to plants, helping to overcome nutrient depletion in the rhizosphere caused by root uptake[17]. A significant correlation between the concentration of potassium and the colonization intensity could also be attributed to factors such as the type of rock from which the soil that originated, the climatic conditions of the region[40], and the rate of geochemical turnover along the altitudinal gradients[41]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the association between arbuscular mycorrhizae fungi and roots of herbaceous species, shrubs, and trees favor their development[7,42]. This beneficial relationship is particularly promising for reforestation efforts where adopting a differentiated approach using nursery seedlings colonized with AMF adapted to specific edaphic conditions could promote improved plant growth along altitudinal gradients. Such a strategy offers a valuable alternative for maintaining the native mountain flora of the Andes, contributing to ecosystem resilience and biodiversity conservation. Our results may also reflect the successional stage of the forest where Cedrela montana trees were sampled. In addition to soil conditions and environmental factors, this stage is likely crucial in understanding ecosystem functionality. Initial forest species often exhibit lower mycorrhizal dependency compared to late-successional species, which require more efficient nutrient cycling mechanisms facilitated by AMF[32].

The parameters assessed in this research may be instrumental in the development of reforestation programs using this native Andean tree. Seedlings of C. montana colonized with arbuscular mycorrhizae offer a promising alternative for population recovery and can be effectively integrated into silviculture programs. The symbiotic relationship between plants and AMF could be leveraged for reforestation efforts to enhance plant development and resilience in degraded habitats, as well as to recover populations of species such as cedar, which have been illegally logged.

It is important to mention that future studies should include larger sample sizes to improve the generalizability and statistical power of the results, thereby enhancing the robustness of the findings. Improving sampling efforts is essential to ensure that the data accurately represents the full range of ecological variations, leading to more reliable conclusions.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Sandoya-Sánchez V, Ascencio-Lino T, Gudiño-Gomezjurado ME, Perez-Cárdenas M; funding acquisition, project administration, initial analyses, results validation: Sandoya-Sánchez V; writing - draft manuscript preparation: Sandoya-Sánchez V, Ascencio-Lino T, Perez-Cárdenas M, Gudiño-Gomezjurado ME; writing - review & editing: Sandoya-Sánchez V, Perez-Cárdenas M; field and lab research conducted: Sandoya-Sánchez V, Gudiño-Gomezjurado ME; methodology development: Gudiño-Gomezjurado ME; data curation, laboratory analyses: Ascencio-Lino T. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

We extend our gratitude to Corporación Ecuatoriana para el Desarrollo de la Investigación y Academia (CEDIA) for their financial support through the CEPRA XIII-2019-03 fund. We also acknowledge the national authorities for granting permits to conduct research in Ecuadorian areas under Scientific Research Authorization No. 023-2019-IC-FLO-DNB/MA. No potential competing interest was reported by the author(s).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 (a) PCA showing the relationship between predictor; (b) exploratory graphs of the correlation and dispersion matrix between predictor variables (elevation, N, P, K, Ca, Mg, pH, and MO), and a bar graph as a representation of the distribution of each variable taken from the PCA.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Sandoya-Sánchez V, Ascencio-Lino T, Gudiño-Gomezjurado M, Perez-Cárdenas M. 2025. Influence of elevation and soil conditions on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonization in the rhizosphere of Cedrela montana. Studies in Fungi 10: e006 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0005

Influence of elevation and soil conditions on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonization in the rhizosphere of Cedrela montana

- Received: 29 September 2024

- Revised: 28 February 2025

- Accepted: 07 March 2025

- Published online: 13 May 2025

Abstract: Soil and fine root samples were collected from C. montana individuals at different elevations to study the abundance of AMF and their driving factors. AMF spore abundance was measured using the sieving and decantation method, while root analysis was performed using a staining technique. Soil chemical properties (pH, SOM, N, P, and K) were analyzed. Data analysis included independent linear regressions to assess the effect of elevation on spore abundance, intensity, and frequency of mycorrhization. Additional regressions were conducted to assess the effect of SOM, pH, P, and K concentrations on spore abundance. Finally, linear models were used to evaluate the influence of soil properties and elevation on AMF spore abundance. A significant positive correlation was found between AMF spore abundance and elevation. Positive correlations were observed between AMF spore abundance and pH, as well as between AMF spore abundance and K concentration. Conversely, the total frequency of mycorrhization showed a negative correlation with K concentration. Interactions indicated that spore abundance increases in the rhizosphere of trees at high elevations with pH values of 6−7. In conclusion, AMF spore abundance in C. montana roots is associated with elevation and soil physical-chemical conditions in the Andean montane forest. Key soil characteristics influencing spore abundance include pH and K concentration. The composition of soil nutrients regulates AMF-root associations, particularly with K concentration along the elevation gradient.

-

Key words:

- Altitude /

- Andean forest /

- Endomycorrhizal colonization /

- Forest tree /

- Soil chemical conditions