-

Endangered plants often grapple with challenges such as habitat loss, overexploitation, and disease susceptibility, making their conservation a complex task. Plant tissue culture offers a powerful tool in this battle against extinction[1,2]. It allows for the propagation of rare and threatened plant species in controlled environments, enabling the mass production of genetically identical individuals. This not only aids in augmenting dwindling populations but also ensures the preservation of their genetic diversity through the application of an advanced plant tissue culture technique known as cryopreservation[3,4]. Moreover, it provides a means to recover and propagate plants from limited or damaged wild populations, acting as a form of botanical insurance. Plant tissue culture also helps overcome the reproductive barriers that some endangered species face, including low seed viability, self-incompatibility, or complex pollination requirements[5]. Furthermore, it allows for the rescue and preservation of unique and valuable plant traits that might otherwise be lost. Beyond conservation, these techniques play a vital role in research and the development of sustainable cultivation methods for endangered species that have economic, medicinal, or ecological significance[6,7].

Gloriosa superba L., an endangered perennial climber from the Liliaceae family, is native to South-East Asia and Africa, with its significance spanning both ornamental and medicinal applications, primarily attributed to the alkaloid colchicine and its derivatives[8,9]. The soaring global demand for biomass has outstripped supply, driving unsustainable harvesting practices that significantly impede its natural regeneration in the wild[10,11]. This perilous situation has escalated to the point where Gloriosa superba L. faces a high risk of extinction, emphasizing the urgent need for its conservation[11,12]. Compounded by factors such as poor seed germination due to a hard seed coat and seed dormancy, vulnerability to soil microorganisms impacting vegetative propagation via tubers, and ongoing unsustainable harvesting practices, the situation becomes even more precarious[11,13]. Consequently, the exploration of alternative methods, including in vitro propagation, has become paramount for conservation efforts[14]. However, this study advocates for a paradigm shift in the current prevailing practices within the global plant tissue culture community for the conservation of endangered plant species through in vitro propagation methods.

Plant tissue culture techniques play a crucial role in plant regeneration and propagation[2]. Direct organogenesis, one such technique entails the immediate differentiation of shoots, roots, or other plant organs from the chosen explant, omitting the need for an intermediate callus formation. Conversely, indirect organogenesis involves a multi-step process wherein callus tissue serves as an intermediary stage in the regeneration process. Through this method, shoots, roots, or other plant organs differentiate from undifferentiated callus tissue, offering an alternative approach to plant propagation and regeneration. However, developing a multi-explant in vitro regeneration protocol utilizing multiple explant types simultaneously is of paramount importance for plant conservation efforts, as it offers numerous advantages that can significantly impact the field. Traditional conservation studies often employ single explant types, making it challenging to draw comprehensive conclusions and reducing the flexibility to adapt to variable conditions such as biological, physiological, and technical challenges[15]. The implementation of a multi-explant regeneration system transcends these limitations by providing multiple alternatives. This approach not only mitigates the difficulties associated with comparing studies employing just one explant type but also addresses the confounding effects of inter-study variability, enhancing the reliability and robustness of the data gathered. It is a novel concept in the sense that it leverages the versatility of plant tissue culture techniques to tackle the intricacies of plant conservation comprehensively, thus representing a paradigm shift in the field. By promoting multi-explant in vitro plant regeneration methods, future plant conservation programs can benefit from a more holistic and adaptable approach. This, in turn, not only refines the quality of research within a single study but also fosters a deeper understanding of the dynamic response of multiple explants to various experimental factors and plant growth regulator treatment combinations. As a result, this approach should be the new norm in plant conservation studies employing plant tissue culture techniques, ushering in a paradigm shift in plant conservation.

Regardless of the chosen approach, in vitro clonal propagation offers numerous advantages, such as the production of virus-free and true-to-type plant stocks. However, it comes with its share of challenges, including issues like vitrification, phenolic leakage, medium browning, poor explant response, recalcitrance, and contamination, which can impede explant growth and overall tissue culture success[16,17]. The selection of appropriate explants is pivotal in formulating a successful in vitro clonal propagation protocol. The type, age, physiological state, and culture method of the chosen explants play a crucial role in influencing culture initiation and subsequent morphogenetic responses[18,19]. Moreover, factors such as plant material availability, seasonal development (particularly relevant in floral tissues), infection levels, and tissue abundance, especially concerning juvenile tissues, further dictate the selection of suitable explants[20]. In this context, prior studies have successfully demonstrated in vitro regeneration using a wide array of Gloriosa superba L. explants, including nodal segments, axillary buds, root explants, young leaves, stems, pedicels, both dormant and non-dormant corm buds, seeds, tubers, and shoot tips sourced from aerial shoots[14,21−25]. However, these studies predominantly focused on one explant type at a time, often under differing conditions, limiting the possibility of an unbiased comparison.

Through a comprehensive analysis of the existing literature concerning in vitro propagation methods for Gloriosa superba L., it became evident that only a limited number of studies have developed plant regeneration protocols via direct organogenesis, and the choice of explant type has been predominantly restricted to shoot tip explants (Supplementary Table S1). In contrast, there are many in vitro protocols centered around callus formation and indirect organogenesis, primarily driven by the potential of harnessing callus for the production of the valuable secondary metabolite, colchicine, which holds immense pharmaceutical and commercial significance[21,24,26,27]. This has created misconceptions and disparities in the literature, as most studies do not provide clarity regarding the distinction between direct and indirect organogenesis approaches, particularly in the context of Gloriosa superba L. For example, a critical examination of many prior in vitro clonal propagation studies on Gloriosa superba L. reveal instances where indirect organogenesis has been wrongly reported as direct organogenesis, potentially confusing[22,28].

Furthermore, while this study strongly advocates the necessity of implementing multi-explant in vitro propagation strategies for the conservation of endangered plants, indeed, this approach has been applied in the case of Gloriosa superba L. In this case, only three prior studies were identified in the existing literature. However, in all three cases, the multi-explant approaches exclusively focused on indirect organogenesis through callus derived from various explant types often with a limited interpretation and documentation of results concerning shoot initiation, affirming the aforementioned rationale (Supplementary Tables S2−S4). To the best of our knowledge, there is no record of any study presenting a multi-explant in vitro propagation method for the conservation of Gloriosa superba L. through direct organogenesis. The unavailability of such studies is attributable to the prevailing misconceptions surrounding direct and indirect organogenesis in Gloriosa superba L. Ade & Rai[29] conducted a comprehensive study examining the impact of various media types (including Murashige & Skoog[30], Gamborg's B5, Nitsch medium, White's medium, and Chu's N6, each supplemented with Coconut water) on callus growth and the formation of multiple shoots in Gloriosa superba L., utilizing a range of explants such as leaves, non-dormant corm buds, auxiliary buds, nodal portions, and seeds. All experiments in this study used the Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium because their findings showed it to be the best option for this specific plant species. Moreover, this research endeavors to rectify prevailing misinformation surrounding direct organogenesis in Gloriosa superba L. by exemplifying the multi-explant approach for direct organogenesis in Gloriosa superba L.

Therefore, this study aims to establish a robust multi-explant regeneration system that simultaneously utilizes and compares the effect of various types and combinations of plant growth regulators (PGRs) on direct organogenesis from apical shoots, meristems, shoot tips, nodal segments, and non-dormant corm explants of Gloriosa superba L. This approach allows for a fair and impartial comparison of various PGR treatments and explant types for direct organogenesis, facilitating the identification of the most effective process for in vitro clonal propagation for conservation purposes. Additionally, it tackles the issue of inter-study variability, a common challenge when studies rely on fewer than two explant types, in contrast to the five explored in this study. The goal of this inclusive approach is to not only identify the best type of explant and plant growth regulator (PGR) treatment for direct organogenesis but also to address the urgent need for conservation. This new approach is essential for advancing research on plant conservation, ensuring a complete understanding of how different types of explants respond to various PGR treatments, and establishing a standard for a comprehensive evaluation in the important task of conserving endangered plant species like Gloriosa superba L.

-

The plant materials used in this study were collected from the Pachmarhi Biosphere Reserve in Madhya Pradesh, India. Specifically, shoot tips and meristem explants were selected from in vitro cultivated Gloriosa superba L. plants. Additionally, explants such as apical shoots, nodal segments, and non-dormant corms were excised from healthy, mature plants and employed as sources for further experimentation. Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (1962)[30] was employed for the culture media, along with specific supplements and growth regulators. Adenine sulphate (ADS), activated charcoal (AC), 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP), kinetin (KN), thidiazuron (TDZ), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), indole-3-butyric acid (IBA), 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA), and their respective solvents were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (Mumbai, India).

Surface sterilization of explant

-

Nodal segments and non-dormant corm explants underwent a thorough washing process to ensure their cleanliness. Initially, the explants were immersed in Teepol solution (5% v/v) for 20 min, followed by three rinses with double distilled water (DDW). Subsequently, they were washed with Bavistin solution (1% w/v) for 30 min and rinsed three times with DDW. The explants were treated within a laminar flow hood to achieve surface sterilization. They were first exposed to 70% ethanol (v/v) for 20 s, followed by immersion in 0.1% HgCl2 (w/v) for 5 min. Afterward, the explants were rinsed three times with sterile water to remove residual sterilising agents. These sterilized explants were then prepared by cutting them into small segments using sterile scalpel blades before being transferred to the culture media. On the other hand, uncontaminated shoot tips and meristem explants, obtained directly from in vitro grown plants, were considered already clean and required only three rinses with sterile water before culture establishment.

Growth conditions

-

The cultures were carefully maintained on shelves within a dedicated growth room. Two centrally positioned fluorescent bulbs (Philips, India) were installed approximately 25−30 cm above the culture vessels to ensure a photosynthetic photon flux density of 80 μmol·m−2·s−1. The photoperiod was set to 16 h of light and 8 h of darkness. The growth room maintained a consistent temperature range of 25 ± 2 °C during the light period, while it gradually decreased to 5 °C in the dark period. This controlled temperature regime provided optimal conditions for the cultures' growth and development.

In vitro direct organogenesis

-

This study investigated the effect of different types, combinations, and concentrations of plant growth regulators (PGRs) on direct organogenesis in various explants of Gloriosa superba L., involving apical shoots, nodal segments, non-dormant corms, and in vitro shoot tips and meristems.

Nodal segments

-

Nodal explants (3 cm long) that had undergone surface sterilisation were aseptically transferred to culture media containing varying concentrations of plant growth regulators, specifically BAP (0.5−2.5 mg·L−1) and TDZ (0.1−1.0 mg·L−1), as shown in Table 1. The culture medium comprised full-strength MS basal salts with 2% (w/v) sucrose (HiMedia, India), pH of 5.8, solidified using 0.8% (w/v) agar (HiMedia, India). The culture flasks containing 50 ml of basal MS medium were sealed with non-absorbent cotton plugs and autoclaved at 121 °C and 104 kPa pressure for 20 min to maintain sterility. Each treatment consisted of four replications containing nine surface sterilized nodal explants cultured individually in 250 ml flasks. After a six-week incubation period, the cultures were evaluated, and data was recorded on parameters including the number of nodal explants forming shoots, the response rate to the shooting treatment, the time required for shoot induction, the number of new shoots per explant, and the length of the shoots in centimeters.

Table 1. Concentrations and combinations of 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) and thidiazuron (TDZ) evaluated for their efficacy in inducing direct organogenesis in nodal explants of Gloriosa superba L.

Group Treatments PGR combinations (mg·L−1) BAP TDZ T1 (control) 0.0 0.0 1 T2 0.5 0.0 T3 1.0 0.0 T4 1.5 0.0 T5 2.0 0.0 T6 2.5 0.0 2 T7 0.5 0.1 T8 0.5 0.2 T9 1.0 0.2 T10 1.0 0.5 T11 1.5 0.2 T12 1.5 0.5 T13 1.5 1.0 T14 2.0 0.5 T15 2.0 1.0 T16 2.5 0.5 T17 2.5 1.0 Non-dormant corms

-

Non-dormant corm explants (1 cm × 1 cm), having undergone surface sterilization, were aseptically placed onto culture media with varying concentrations of plant growth regulators. Specifically, BAP (0.5−2.5 mg·L−1) in combination with either ADS (1.5 mg·L−1) or AC (10−20 mg·L−1) and KN (0.2−2.5 mg·L−1) in combination with either ADS (1.5 mg·L−1) or AC (10−20 mg·L−1) as indicated in Table 2. The medium consisted of half-strength MS basal salts and vitamins, supplemented with 2% (w/v) sucrose (HiMedia, India). The pH of the medium was adjusted to 5.8, and solidification was achieved by incorporating 0.8% (w/v) agar (HiMedia, India). To maintain aseptic conditions, culture flasks containing 50 ml of basal MS were sealed with non-absorbent cotton plugs and autoclaved at 121 °C and 104 kPa pressure for 20 min. Each treatment included four replications containing nine surface sterilized non-dormant corm explants cultured individually in 250 ml flasks. After a six-week incubation period, the cultures were assessed, and data was collected on parameters such as the number of non-dormant corm explants forming shoots, the response rate to the shooting treatment, the time required for shoot induction, the number of new shoots per explant, and the length of the shoots in centimeters.

Table 2. Concentrations and combinations of 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP), kinetin (KN), activated charcoal (AC), and adenine sulphate (ADS) evaluated for their efficacy in inducing direct organogenesis in non-dormant corm explants of Gloriosa superba L.

Group Treatments PGR combinations (mg·L−1) BAP KN AC (mg·L−1) T1 (control) 0.0 0.0 0.0 1 T2 0.2 − 1.5 T3 0.5 − 1.5 T4 1.0 − 1.5 T5 1.5 − 1.5 T6 2.0 − 1.5 T7 2.5 − 1.5 2 T8 − 0.2 1.5 T9 − 0.5 1.5 T10 − 1.0 1.5 T11 − 1.5 1.5 T12 − 2.0 1.5 T13 − 2.5 1.5 ADS (mg·L−1) 3 T14 0.5 − 10 T15 1.0 − 10 T16 1.5 − 10 T17 0.5 − 20 T18 1.0 − 20 T19 1.5 − 20 4 T20 − 0.5 10 T21 − 1.0 10 T22 − 1.5 10 T23 − 0.5 20 T24 − 1.0 20 T25 − 1.5 20 Shoot tips

-

Uncontaminated in vitro derived shoot tip explants (2 cm long) were aseptically placed onto culture media with varying concentrations of plant growth regulators, namely BAP (0.5−2.5 mg·L−1), TDZ (0.1−1.0 mg·L−1), and ADS (5−10 mg·L−1) as presented in Table 3. The composition of the medium consisted of full-strength MS basal salts with 2% (w/v) sucrose (HiMedia, India), pH adjusted to 5.8, and solidification was achieved by incorporating 0.8% (w/v) agar (HiMedia, India). The culture vessels containing 50 ml of basal MS were sealed using non-absorbent cotton plugs to maintain sterile conditions and subjected to autoclaving at 121 °C under 104 kPa pressure for 20 min. Each treatment included four replications, with each replicate containing nine surface sterilized shoot tip explants cultured individually in 250 ml flasks. Following a six-week incubation period, the cultures were assessed, and data was collected on parameters such as the number of shoot tip explants forming shoots, the response rate to the shooting treatment, the time required for shoot induction, the number of new shoots per explant, and the length of the shoots in centimeters.

Table 3. Concentrations and combinations of 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP), thidiazuron (TDZ), and adenine sulphate (ADS) evaluated for their efficacy in inducing direct organogenesis in shoot tip explants of Gloriosa superba L.

Group Treatments PGR combinations (mg·L−1) BAP TDZ ADS T1 (control) 0.0 0.0 0.0 1 T2 0.5 0.0 5 T3 1.0 0.0 5 T4 1.5 0.0 5 T5 2.0 0.0 5 T6 2.5 0.0 5 2 T7 0.5 0.1 8 T8 0.5 0.2 8 T9 1.0 0.2 8 T10 1.0 0.5 8 T11 1.5 0.2 8 T12 1.5 0.5 8 3 T13 1.5 1.0 10 T14 2.0 0.5 10 T15 2.0 1.0 10 T16 2.5 0.5 10 T17 2.5 1.0 10 Apical shoot and meristem

-

In separate experiments, surface sterilized apical shoots (2 cm long) and uncontaminated in vitro-derived meristem explants (2 cm long) were introduced to culture media with varying concentrations of plant growth regulators. Specifically, BAP (0.5−2.0 mg·L−1), KN (0.5−2.0 mg·L−1), and BAP (0.5−2.0 mg·L−1) in combination with NAA (0.1–0.8 mg·L−1) were utilized, as depicted in Table 4. The composition of the medium consisted of full-strength MS basal salts with 2% (w/v) sucrose (HiMedia, India), pH adjusted to 5.8, and solidification was achieved by incorporating 0.8% (w/v) agar (HiMedia, India). The culture vessels containing 50 ml of basal MS were sealed using non-absorbent cotton plugs to maintain aseptic conditions and autoclaved at 121 °C under 104 kPa pressure for 20 min. Each experiment included four replications containing 12 surface sterilized apical shoot and meristem explants cultured individually in 250 ml flasks. After a six-week incubation period, the cultures were assessed, and data was collected on various parameters, including the count of explants forming shoots, the response rate to the shooting treatment, the time required for shoot induction, the number of new shoots per explant, and the length of the shoots in centimeters.

Table 4. Concentrations and combinations of 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP), kinetin (KN), and 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) evaluated for their efficacy in inducing direct organogenesis in apical shoot and meristem explants of Gloriosa superba L.

Group Treatments PGR combinations (mg·L−1) BAP NAA KN 1 T1 0.5 − − T2 1.0 − − T3 1.5 − − T4 2.0 − − 2 T5 0.5 0.1 − T6 1.0 0.2 − T7 1.5 0.4 − T8 2.0 0.6 − T9 2.5 0.8 − 3 T10 − − 0.5 T11 − − 1.0 T12 − − 1.5 T13 − − 2.0 T14 (control) 0.0 0.0 0.0 In vitro rooting

-

An equivalent number of micro shoots (6–8 cm long) were randomly selected from in vitro cultures of apical shoots, meristems, nodal segments, non-dormant corms, and shoot tip explants. These excised micro shoots were assigned, following a completely randomized design, to culture media containing IBA (0.5–1.5 mg·L−1), IAA (0.5–1.5 mg·L−1), or NAA (0.5–1.5 mg·L−1), as illustrated in Table 5. The medium composition consisted of half-strength MS basal salts with a pH adjusted to 5.8. Solidification was achieved by incorporating 0.8% (w/v) agar (HiMedia, India). The culture flasks were sealed with non-absorbent cotton plugs and autoclaved at 121 °C under 104 kPa pressure for 20 min to maintain aseptic conditions. Each treatment was replicated four times, with each replicate containing 12 uncontaminated micro shoots cultured individually in 250 ml flasks. The cultures were maintained under the same conditions as previously described. After a six-week incubation period, the cultures were assessed, and data was collected on the number of micro shoots developing roots, the response rate to the rooting treatment, the time required for root induction, and the length of the roots in centimeters.

Table 5. Concentrations of indole-3-butyric acid (IBA), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), and 1-naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) evaluated for their efficacy in inducing rooting in micro shoots derived from nodal, non-dormant corm, shoot tip, apical shoot, and meristem explants of Gloriosa superba L.

Treatments ½ MS + Auxins (mg·L−1) IBA T1 0.5 T2 1.0 T3 1.5 IAA T4 0.5 T5 1.0 T6 1.5 NAA T7 0.5 T8 1.0 T9 1.5 T10 (control) 0.0 Ex vitro acclimatisation

-

To prepare for acclimatization, well-developed plantlets were carefully harvested from the rooting medium and thoroughly rinsed with deionized water to eliminate any residual medium. Subsequently, the plantlets were transferred to small polyethene bags, plastic trays, plastic pots, or 7-cm-diameter thermocol cups. The containers were filled with sterile vermiculite and soil mixed in a 1:1 ratio. During the initial acclimatisation stage, the plantlets were placed under a 16-h photoperiod with a photosynthetic photon flux density of 50 μmol m−2s−1 provided by white fluorescent tubes (40 W; Philips, India). Plantlets were covered with polyethene bags with small air holes to maintain high humidity and prevent dehydration. The culture room was kept at a temperature of 25 ± 2 °C. The bags were removed for 1 h each day. For two weeks, the potted plantlets were irrigated every 4 d with 10 ml of half-strength Murashige & Skoog[30] basal salt solution (excluding sucrose and myo-inositol), adjusted to a pH of 5.8.

After the initial acclimatization, the plantlets were transplanted into medium-sized polyethene bags, plastic cups, or thermocol cups containing a mixture of garden soil, sand, and vermiculite in a ratio of 2:1:1 (v/v). These transplanted plantlets were placed in a shade net house (SNH) for two weeks with regular misting using tap water. The relative humidity (RH) was gradually reduced by 50%. Subsequently, the plantlets were transplanted into larger earthen pots with a diameter of 15 cm, filled with a standard mixture of garden soil, sand, and farmyard manure in a ratio of 2:1:1 (v/v). These pots were kept in direct sunlight for ten weeks (i.e., until the 14th week).

Measurements of plant survival, plant height (cm), number of leaves per plant, number of flowers per plant, and number of micro-tubers per plant were recorded two weeks after transplantation in sterilized vermiculite and soil (1:1) in the culture room (CR), two weeks after transplantation in garden soil, sand, and vermiculite (2:1:1) under shade in the net house (USNH), and ten weeks after transplantation in standard garden soil, sand, and farmyard manure (2:1:1) under direct sunlight. Data was collected for 14 weeks following the initiation of micro shoot acclimatisation. Weekly observations were made after the transplantation of micro-plantlets into the aforementioned potting mixtures. Each treatment consisted of four replicates containing 14 micro-plantlets, resulting in 56 micro-plantlets observed per treatment. The survival rate of the regenerated plantlets was calculated using the equation: Survival rate (%) = (Number of surviving regenerated plants / Total number of transplanted regenerated plants) × 100%. The presented data represents the mean values with standard error (SE).

Statistical analysis

-

A completely randomized experimental design was employed for all experiments, where seeds and seedlings were randomly assigned to different treatment groups. In the in vitro shoot multiplication and in vitro rooting experiments, each treatment level was replicated four times, with nine explants and 12 micro shoots in each replicate, respectively. The experiments were repeated twice to ensure the reliability of the results. Data for all parameters were collected after six weeks. The percent response to treatment was calculated as the number of explants or micro shoots that exhibited a positive response divided by the total number of replicates multiplied by 100. The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. If the normality test yielded a non-significant result (p ≥ 0.05), a parametric test (one-way ANOVA at α = 0.05) was utilized to compare the means. Conversely, if the normality test yielded a significant result (p ≤ 0.05), a non-parametric test (Kruskal-Wallis test at α = 0.05) was employed for mean comparisons. Data analysis was performed using R Studio software (version 4.4.0), applying one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Kruskal-Wallis test. Mean separation was conducted using Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) test at α = 0.05. All results were expressed as mean values ± standard error. Different letters in the figures indicated significant differences at the p ≤ 0.05 level.

-

The application of various plant growth regulators at different concentrations significantly affected the in vitro regeneration of shoots from nodal, non-dormant corm, shoot tip, apical shoot, and meristem explants of Gloriosa superba L. During the shoot morphogenesis process, no root formation was observed, and no callus development occurred at the base of the shoots. Additionally, the leaves did not exhibit hyperhydricity (Supplementary Figs S1−S7 illustrate these observations).

Effect of plant growth regulators on shoot morphogenesis in nodal explants

Treatment with BAP

-

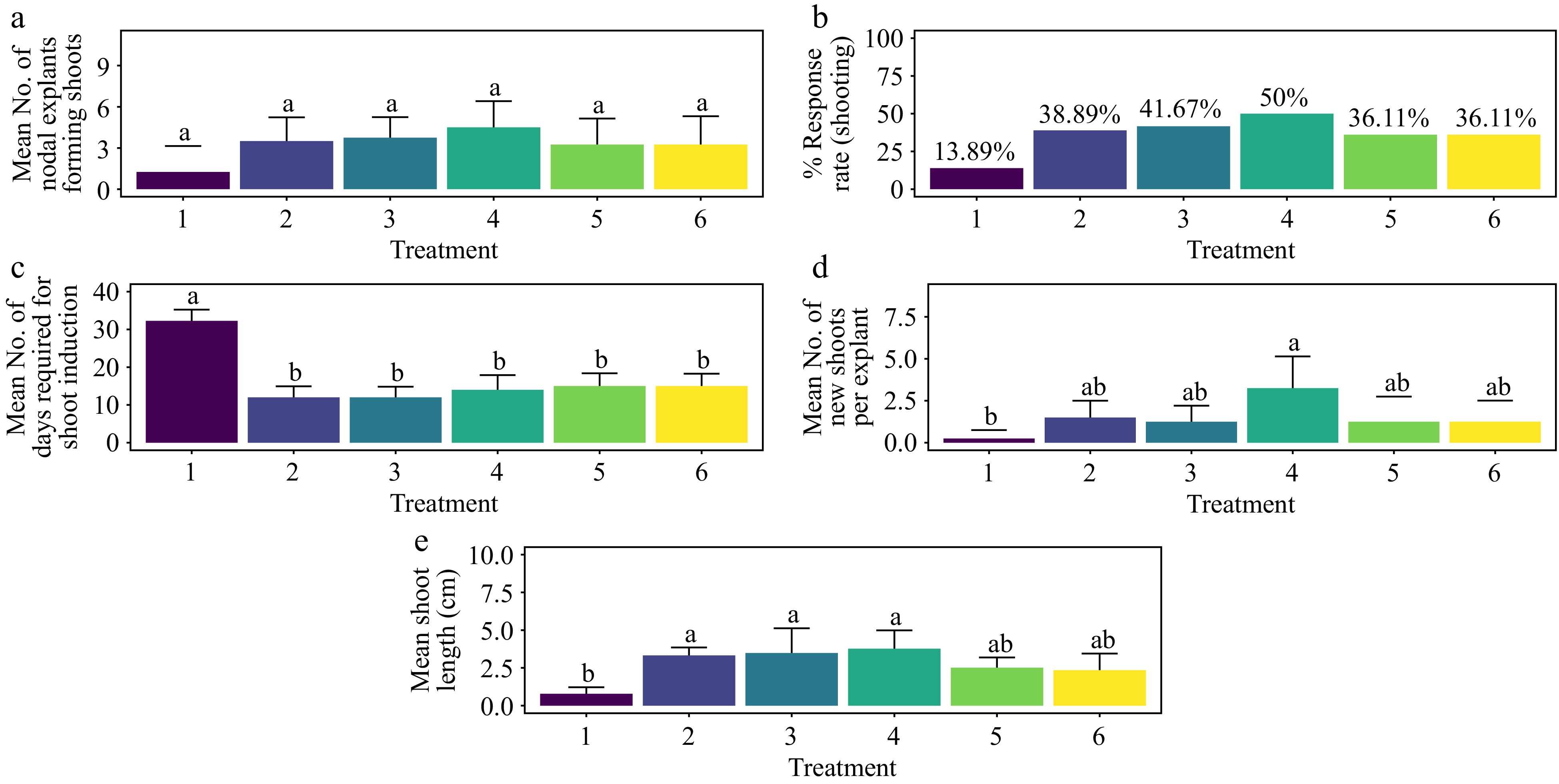

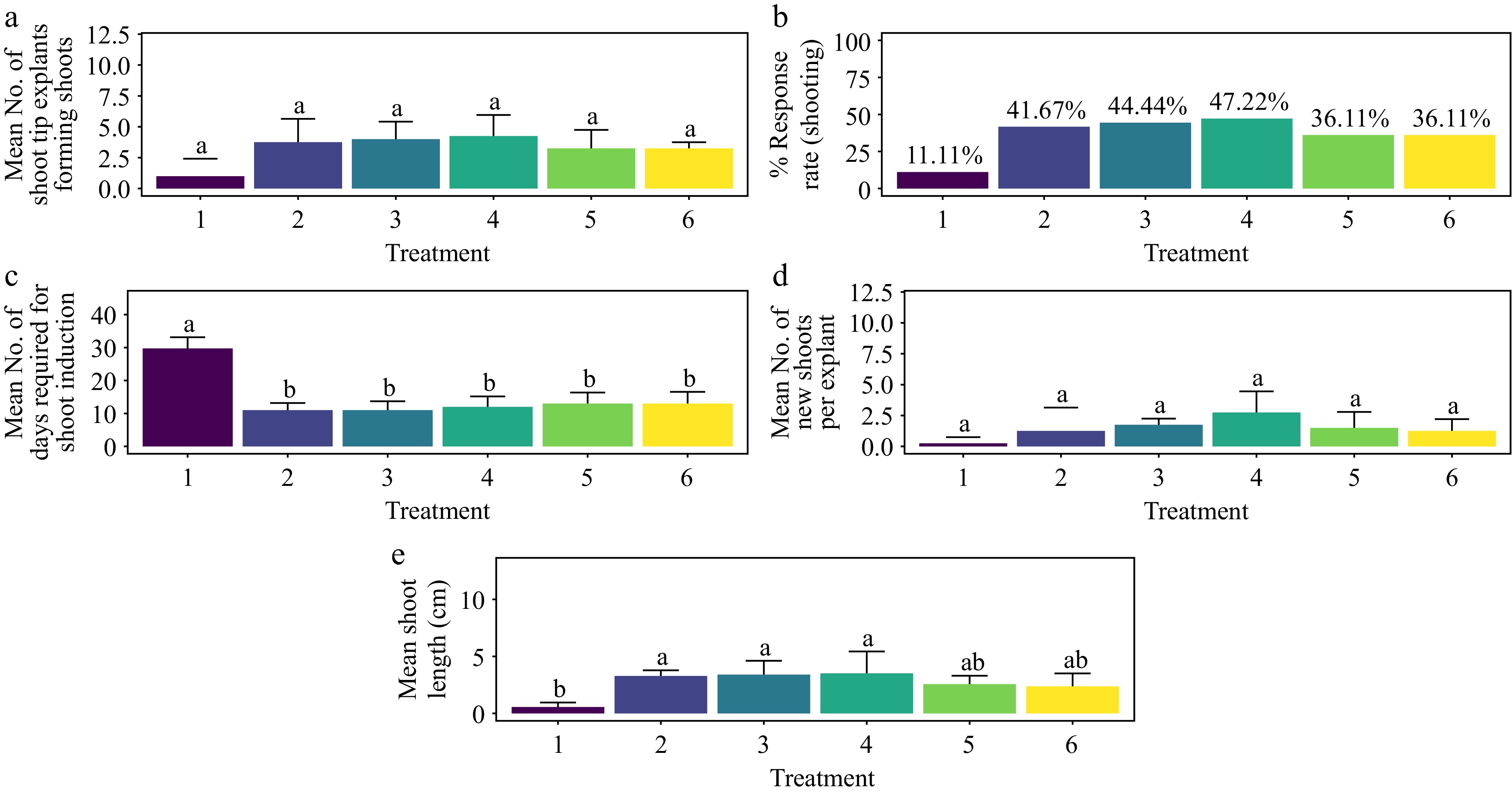

Overall, the concentration of BAP influenced the shoot induction response rate (Fig. 1). The nodal explants treated with 1.5 mg·L−1 of BAP exhibited the highest rate of shoot formation. However, this was not statistically different from the other treatments (Fig. 1b) (p > 0.276). Similar trends were observed in the average number of days required for shoot induction and average shoot length (cm), except for shoot proliferation, where significant differences were noted (Fig. 1e). Treatment with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP achieved the highest shoot response rate (50.0%), followed by 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP (41.7%), 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP (38.9%), and 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP (36.1%) (Fig. 1b). The shortest average time required for shoot formation (12 d) was observed with 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP and 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP, which was significantly shorter than the control (p < 0.03834) but not different from the other treatments (Fig. 1c). Except for the control, there were no significant differences in the average number of shoots per explant among the treatments (p > 0.120). The highest number of shoots per nodal explant (3.25) was recorded for 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP (Fig. 2d). Treatment with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP also resulted in an average shoot length of 3.77 cm. This was significantly longer than what was seen with T5, T6, and the control (Fig. 1e) (p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Effect of PGRs on in vitro morphogenetic response (shoot multiplication) in nodal explant of Gloriosa superba L. (a) Mean nodal explants forming shoots, (b) response rate to shooting treatment, and (c) mean days required for shoot induction, (d) mean of new shoots per explant, and (e) mean shoot length. Treatments were T1: Control (media without PGRs); T2: 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP; T3: 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP; T4: 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP; T5: 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP; T6: 2.5 mg·L−1 BAP. Bars indicate mean ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test at p ≤ 0.05.

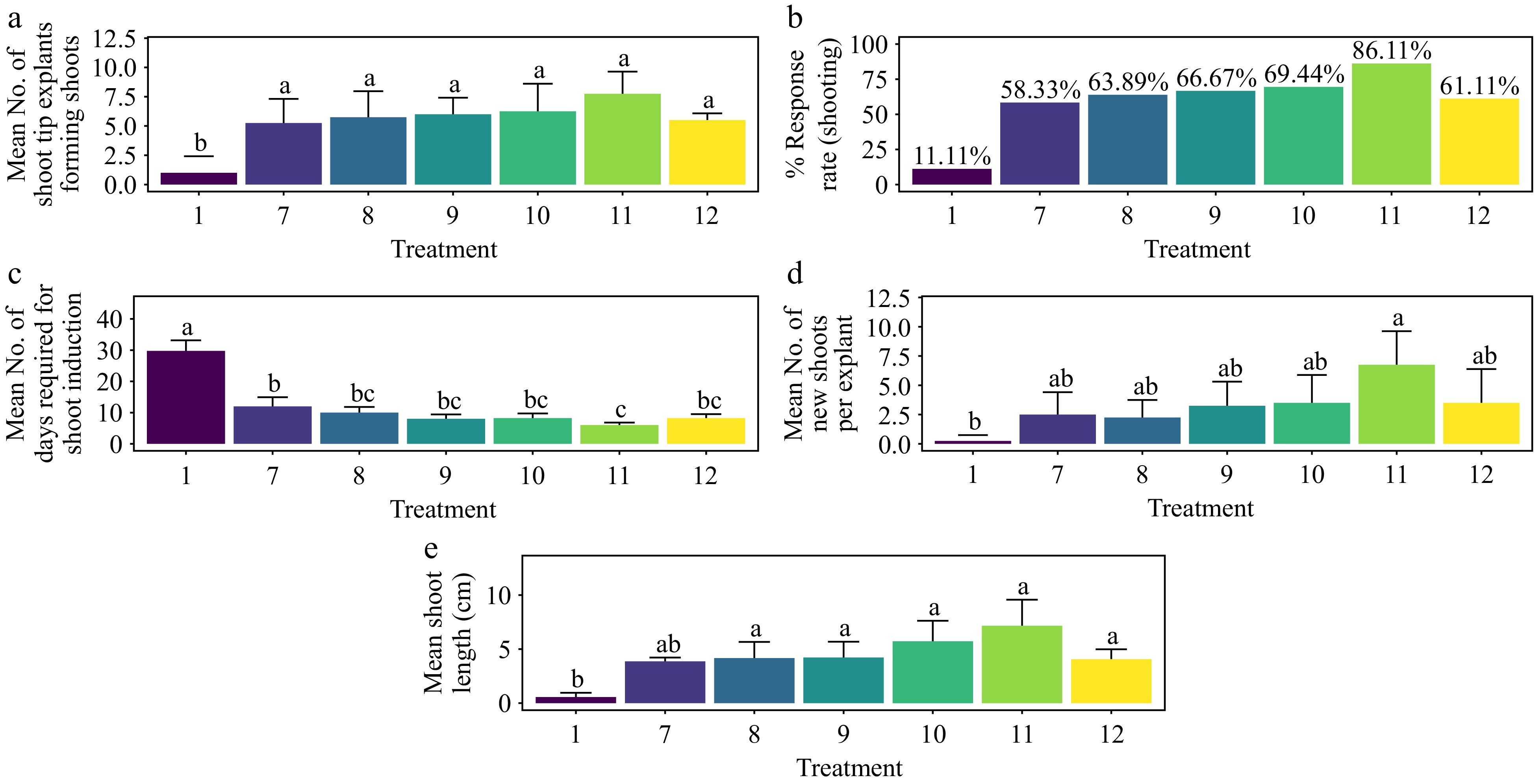

Figure 2.

Effect of PGRs on in vitro morphogenetic response (shoot multiplication) in nodal explant of Gloriosa superba L. (a) Mean nodal explants forming shoots, (b) response rate to shooting treatment, and (c) mean days required for shoot induction, (d) mean of new shoots per explant, and (e) mean shoot length. Treatments were T1: Control (media without PGRs); T7: 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.1 mg·L−1 TDZ; T8: 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.2 mg·L−1 TDZ; T9: 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.2 mg·L-1 TDZ; T10: 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.5 mg·L−1 TDZ; T11: 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.2 mg·L−1 TDZ; T12: 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.5 mg·L−1 TDZ; T13: 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.0 mg·L−1 TDZ; T14: 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.5 mg·L−1 TDZ; T15: 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.0 mg·L−1 TDZ; T16: 2.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.5 mg·L−1 TDZ; T17: 2.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.0 mg·L−1 TDZ. Bars indicate mean ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test at p ≤ 0.05.

Treatment with BAP and TDZ

-

The types and concentrations of cytokinins used significantly influenced the response rate to the shooting treatment (Figs 1 & 2). Treatment of nodal explants with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.2 mg·L−1 TDZ yielded the most rapid and optimal response for shoot formation, showing statistically significant differences compared to all other treatments, including the control (Fig 2a−c) (p < 0.001). After six weeks of incubation, this treatment also resulted in the highest shoot length (biomass) and shoot proliferation (the average number of shoots per explant). While the shoot length was statistically significant, the differences in shoot proliferation were not (Fig 2d & e). The highest shoot response rate, 88.89%, was achieved with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.2 mg·L−1 TDZ, significantly differing from the control and other combinations, including 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP + 1.0 mg·L−1 TDZ, 2.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.5 mg·L−1 TDZ, and 2.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 1.0 mg·L−1 TDZ (Fig. 2b) (p < 0.001). However, no significant differences in shoot proliferation were observed across the treatments (Fig. 2d).

The shortest time to shoot formation (8 d) was observed with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.2 mg·L−1 TDZ, which was significantly different from both the control and 2.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 1.0 mg·L−1 TDZ (Fig. 2c) (p < 0.001). While there was no significant difference in the average number of shoots per explant, the highest number (5.75) was recorded with the 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.2 mg·L−1 TDZ treatment (Fig. 2d) (p > 0.2307). This treatment also exhibited the greatest average shoot length (6.71 cm), which was significantly different from the control and other treatments, including T7, T13, T14, T15, T16, and T17 (Fig. 2e) (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the base of the shoots showed no callus formation, and the leaves showed no signs of hyperhydricity (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Effect of plant growth regulators on shoot morphogenesis in non-dormant corm explants

Treatment with BAP and AC

-

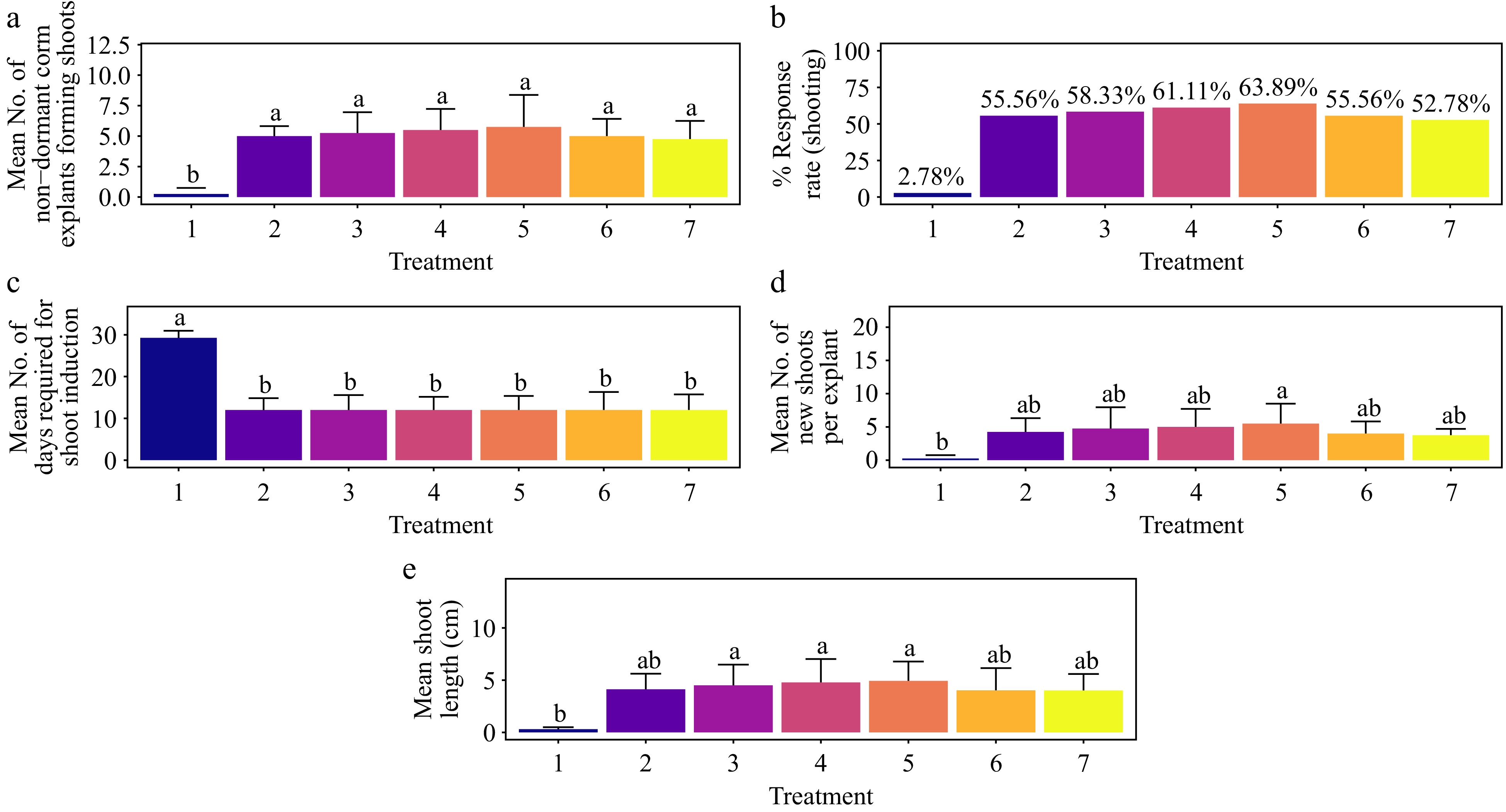

The treatment of 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 1.5 mg·L−1 AC achieved the highest shoot response rate, 63.89%, significantly surpassing the control. This was followed by the treatments with 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP + 1.5 mg·L−1 AC and 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 1.5 mg·L−1 AC, which also differed significantly from the control (Fig. 3a & b). No significant differences in shoot formation were observed among the remaining treatments (Fig. 3a) (p > 0.095). The time required for shoot formation was consistently 12 d across all treatments (p > 0.122), with a statistically significant difference observed only in the control (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3c). The treatment of 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 1.5 mg·L−1 AC also resulted in the highest average number of shoots per explant (5.5), although this did not significantly differ from other treatments except the control (Fig. 3d) (p > 0.066). The second-highest average number of shoots per explant (5.0) was observed with 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP + 1.5 mg·L−1 AC. Regarding shoot length, the highest average of 4.93 cm was recorded with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 1.5 mg·L−1 AC, which did not significantly differ from other treatments except the control (Fig. 3e) (p < 0.020). The treatment of 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP + 1.5 mg·L−1 AC produced the second-highest average shoot length of 4.77 cm. The base of the shoots showed no callus, and the leaves showed no signs of hyperhydricity (Supplementary Figs S2−S4).

Figure 3.

Effect of PGRs on in vitro morphogenetic response (shoot multiplication) in non-dormant corm explant of Gloriosa superba L. (a) Mean non-dormant corm explants forming shoots, (b) response rate to shooting treatment, and (c) mean days required for shoot induction, (d) mean of new shoots per explant, and (e) mean shoot length. Treatments were T1: Control (media without PGRs); T2: 0.2 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.5 mg·L−1 AC; T3: 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.5 mg·L−1 AC; T4: 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.5 mg·L−1 AC; T5: 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.5 mg·L−1 AC; T6: 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.5 mg·L−1 AC; T7: 2.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.5 mg·L−1 AC. Bars indicate mean ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test at p ≤ 0.05.

Treatment with KN and AC

-

The highest shoot response rate of 50.0% was achieved with the treatment of 1.5 mg·L−1 KN + 1.5 mg L−1 AC, followed by 1.0 mg·L−1 KN + 1.5 mg·L−1 AC, and 0.5 mg·L−1 KN + 1.5 mg·L−1 AC (Fig. 4b). Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences in shoot formation among these treatments, except for the control (Fig. 4a) (p < 0.017). The shortest time to shoot formation, averaging 15 d was observed with 1.5 mg·L−1 KN + 1.5 mg·L−1 AC, although this did not differ significantly from other treatments, excluding the control (Fig. 4c) (p < 0.001). The treatment of 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 1.5 mg·L−1 AC resulted in the highest average number of shoots per explant (3.25), which was not significantly different from other treatments, including the control (p > 0.29) (Fig. 4d). The second-highest average number of shoots per explant (3.00) was achieved with 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP + 1.5 mg·L−1 AC. For average shoot length, 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 1.5 mg·L−1 AC yielded the greatest length of 2.52 cm, which did not significantly differ from other treatments, including the control (p > 0.138) (Fig. 4e). The second-highest average shoot length (2.38 cm) was observed with 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP + 1.5 mg·L−1 AC. The base of the shoots showed no callus, and the leaves showed no signs of hyperhydricity (Supplementary Figs S2−S4).

Figure 4.

Effect of PGRs on in vitro morphogenetic response (shoot multiplication) in non-dormant corm explant of Gloriosa superba L. (a) Mean non-dormant corm explants forming shoots, (b) response rate to shooting treatment, and (c) mean days required for shoot induction, (d) mean of new shoots per explant, and (e) mean shoot length. Treatments were T1: Control (media without PGRs); T8: 0.2 mg·L−1 KN, 1.5 mg·L−1 AC; T9: 0.5 mg·L−1 KN, 1.5 mg·L−1 AC; T10: 1.0 mg·L−1 KN, 1.5 mg·L−1 AC; T11: 1.5 mg·L−1 KN, 1.5 mg·L−1 AC; T12: 2.0 mg·L−1 KN, 1.5 mg·L−1 AC; T13: 2.5 mg·L−1 KN, 1.5 mg·L−1 AC. Bars indicate mean ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test at p ≤ 0.05.

Treatment with BAP and ADS

-

The highest shoot response rate of 91.7% was achieved with the treatment of 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 10 mg·L−1 ADS, significantly surpassing the control and other treatments (Fig. 5b) (p < 0.001). This was followed by the combinations of 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 20 mg·L−1 ADS and 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP + 10 mg·L−1 ADS, both of which also showed significant differences compared to the control. The remaining treatments showed no significant differences in shoot formation. The 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 10 mg·L−1 ADS treatment recorded the shortest duration for shoot formation, at 7 d. This duration was significantly shorter compared to the control but not significantly different from other treatments (Fig. 5c) (p < 0.001). The highest average number of shoots per explant was 16.20 with the 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 10 mg·L−1 ADS treatment, which was significantly higher than all other treatments except the control (Fig. 5d) (p < 0.001). The second-highest average number of shoots per explant (15.5) was observed with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 20 mg·L−1 ADS. The maximum average shoot length of 8.62 cm was achieved with the 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 10 mg·L−1 ADS treatment, which was significantly longer than all treatments except the control (Fig. 5e) (p < 0.001). The second-highest average shoot length of 8.44 cm was recorded with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 20 mg·L−1 ADS. The base of the shoots showed no callus, and the leaves showed no signs of hyperhydricity (Supplementary Figs S2−S4).

Figure 5.

Effect of PGRs on in vitro morphogenetic response (shoot multiplication) in non-dormant corm explant of Gloriosa superba L. (a) Mean non-dormant corm explants forming shoots, (b) response rate to shooting treatment, and (c) mean days required for shoot induction, (d) mean of new shoots per explant, and (e) mean shoot length. Treatments were T1: Control (media without PGRs); T14: 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 10 mg·L−1 ADS; T15: 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 10 mg·L−1 ADS; T16: 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 10 mg·L−1 ADS; T17: 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 20 mg·L−1 ADS; T18: 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 20 mg·L−1 ADS; T19: 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 20 mg·L−1 ADS. Bars indicate mean ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test at p ≤ 0.05.

Treatment with KN and ADS

-

The highest shoot response rate of 79.4% was achieved with a combination of 1.5 mg·L−1 KN + 20 mg·L−1 ADS, followed by 1.5 mg·L−1 KN + 10 mg·L−1 ADS, 1.0 mg·L−1 KN + 10 mg·L−1 ADS, and 1.0 mg·L−1 KN + 20 mg·L−1 ADS (Fig. 6b). No significant differences in shoot formation were observed among these treatments, except for the control (Fig. 6a) (p < 0.001). The shortest shoot formation time of 9 d was recorded for the 1.5 mg·L−1 KN + 10 mg·L−1 ADS treatment, which was not significantly different from other treatments except the control (Fig. 6c) (p < 0.001). The highest average number of shoots per explant, 8.25, was also observed with 1.5 mg·L−1 KN + 10 mg·L−1 ADS, with no significant difference from other treatments except the control (Fig. 6d) (p < 0.001). The second-highest average number of shoots per explant, 7.75, was recorded with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 20 mg·L−1 ADS. The highest average shoot length of 6.96 cm was achieved with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 10 mg·L−1 ADS, which did not differ significantly from other treatments except the control (Fig. 6e) (p < 0.001). The second-highest average shoot length of 6.78 cm was observed with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 20 mg·L−1 ADS. The base of the shoots showed no callus, and the leaves showed no signs of hyperhydricity (Supplementary Figs S2−S4).

Figure 6.

Effect of PGRs on in vitro morphogenetic response (shoot multiplication) in non-dormant corm explant of Gloriosa superba L. (a) Mean non-dormant corm explants forming shoots, (b) response rate to shooting treatment, and (c) mean days required for shoot induction, (d) mean of new shoots per explant, and (e) mean shoot length. Treatments were T1: Control (media without PGRs); T20: 0.5 mg·L−1 KN, 10 mg·L−1 ADS; T21: 1.0 mg·L−1 KN, 10 mg·L−1 ADS; T22: 1.5 mg·L−1 KN, 10 mg·L−1 ADS; T23: 0.5 mg·L−1 KN, 20 mg·L−1 ADS; T24: 1.0 mg·L−1 KN, 20 mg·L−1 ADS; T25: 1.5 mg·L−1 KN, 20 mg·L−1 ADS. Bars indicate mean ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test at p ≤ 0.05.

Effect of plant growth regulators on shoot morphogenesis in shoot tip explants

Treatment with BAP and 5 mg L−1 ADS

-

The highest shoot response rate of 47.22% was observed when Murashige and Skoog (MS) media were supplemented with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP and 5 mg·L−1 ADS. This response rate did not significantly differ from other treatments, including the control (Fig. 7a & b) (p > 0.066). The treatments of 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 5 mg·L−1 ADS and 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP + 5 mg·L−1 ADS achieved the shortest average time to shoot morphogenesis, 11 days. Response to these treatments was significantly faster compared to all other treatments except the control (Fig. 7c) (p < 0.001). For the average number of shoots per explant, the treatment with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 5 mg·L−1 ADS yielded the highest average of 2.75 shoots per explant. However, this did not differ significantly from other treatments, including the control (Fig. 7d) (p > 0.197). The longest average shoot length of 3.51 cm was recorded with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 5 mg·L−1 ADS, although this length did not significantly differ from all other treatments except the control (Fig. 7e) (p < 0.001). Adventitious shoots were observed within four weeks of culture, but no root formation was noted. Furthermore, no callus formation was observed at the base of the shoots, and the leaves exhibited no signs of hyperhydricity (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Figure 7.

Effect of PGRs on in vitro morphogenetic response (shoot multiplication) in shoot tip explant of Gloriosa superba L. (a) Mean shoot tip explants forming shoots, (b) response rate to shooting treatment, and (c) days required for shoot induction, (d) mean of new shoots per explant, and (e) mean shoot length. Treatments were T1: Control (media without PGRs); T2: 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 5 mg·L−1 ADS; T3: 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 5 mg·L−1 ADS; T4: 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 5 mg·L−1 ADS; T5: 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 5 mg·L−1 ADS; T6: 2.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 5 mg·L−1 ADS. Bars indicate mean ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test at p ≤ 0.05.

Treatment with BAP, TDZ, and 8 mg L-1 ADS

-

The treatment groups showed significant differences in in vitro shoot formation (p < 0.001). The highest shoot response rate of 86.1% was achieved with MS media supplemented with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.2 mg·L−1 TDZ, and 8 mg L−1 ADS. This treatment showed no significant difference from other treatments except the control (Fig. 8a & b) (p < 0.001). The shortest average duration for shoot morphogenesis, 6 days, was also recorded with the same combination of 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.2 mg·L−1 TDZ, and 8 mg·L−1 ADS, which was significantly faster than both the control and T7 treatments (Fig. 8c) (p < 0.001). Regarding the average number of shoots per explant, the highest number (6.75) was achieved with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.2 mg·L−1 TDZ, and 8 mg·L−1 ADS. This result was significantly different from the control treatment but not from other treatments (Fig. 8d) (p < 0.01). The longest average shoot length of 7.16 cm was also observed with this treatment, again differing significantly from the control but not from other treatments (Fig. 8e) (p < 0.001). Adventitious shoots emerged within four weeks of culture but without root formation. No callus was observed at the base of the shoots, and there was no incidence of leaf hyperhydricity (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Figure 8.

Effect of PGRs on in vitro morphogenetic response (shoot multiplication) in shoot tip explant of Gloriosa superba L. (a) Mean shoot tip explants forming shoots, (b) response rate to shooting treatment, and (c) days required for shoot induction, (d) mean of new shoots per explant, and (e) mean shoot length. Treatments were T1: Control (media without PGRs); T7: 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.1 mg·L−1 TDZ, 8 mg·L−1 ADS; T8: 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.2 mg·L−1 TDZ, 8 mg·L−1 ADS; T9: 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.2 mg·L−1 TDZ, 8 mg·L−1 ADS; T10: 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.5 mg·L−1 TDZ, 8 mg·L−1 ADS; T11: 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.2 mg·L−1 TDZ, 8 mg·L−1 ADS; T12: 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.5 mg·L−1 TDZ, 8 mg·L−1 ADS. Bars indicate mean ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test at p ≤ 0.05.

Treatment with BAP, TDZ, and 10 mg·L−1 ADS

-

The highest shoot response rate, reaching 58.33%, was observed when the Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium was supplemented with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.0 mg·L−1 TDZ, and 10 mg·L−1 ADS. This response rate was significantly greater than that of the control (Fig. 9a & b) (p < 0.001). Additionally, the shortest average time for shoot morphogenesis, 12 d, was recorded under the same treatment conditions (1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.0 mg·L−1 TDZ, 10 mg·L−1 ADS), which was significantly faster compared to the control (Fig. 9c) (p < 0.001). Regarding the average number of shoots per explant, the treatment of 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.0 mg·L−1 TDZ, and 10 mg·L−1 ADS resulted in the highest average number of shoots (3.75). This result was significantly higher than that of the control, though not significantly different from other treatments (Fig. 9d) (p < 0.01). The longest shoots (7.16 cm) were achieved with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.0 mg·L−1 TDZ, and 10 mg·L−1 ADS for average shoot length. This length was significantly greater than that of the control but not significantly different from other treatments (Fig. 9e) (p < 0.001). Adventitious shoots were observed within four weeks of culture; however, root formation was not noted. No callus formation occurred at the base of the shoots, and the leaves exhibited no signs of hyperhydricity (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Figure 9.

Effect of PGRs on in vitro morphogenetic response (shoot multiplication) in shoot tip explant of Gloriosa superba L. (a) Mean shoot tip explants forming shoots, (b) response rate to shooting treatment, and (c) days required for shoot induction, (d) mean of new shoots per explant, and (e) mean shoot length. Treatments were T1: Control (media without PGRs); T13: 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.0 mg·L−1 TDZ, 10 mg·L−1 ADS; T14: 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.5 mg·L−1 TDZ, 10 mg·L−1 ADS; T15: 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.0 mg·L−1 TDZ, 10 mg·L−1 ADS; T16: 2.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.5 mg·L−1 TDZ, 10 mg·L−1 ADS; T17: 2.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 1.0 mg·L−1 TDZ, 10 mg·L−1 ADS. Bars indicate mean ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test at p ≤ 0.05.

Effect of plant growth regulators on shoot morphogenesis in apical shoot explants

Treatment with BAP

-

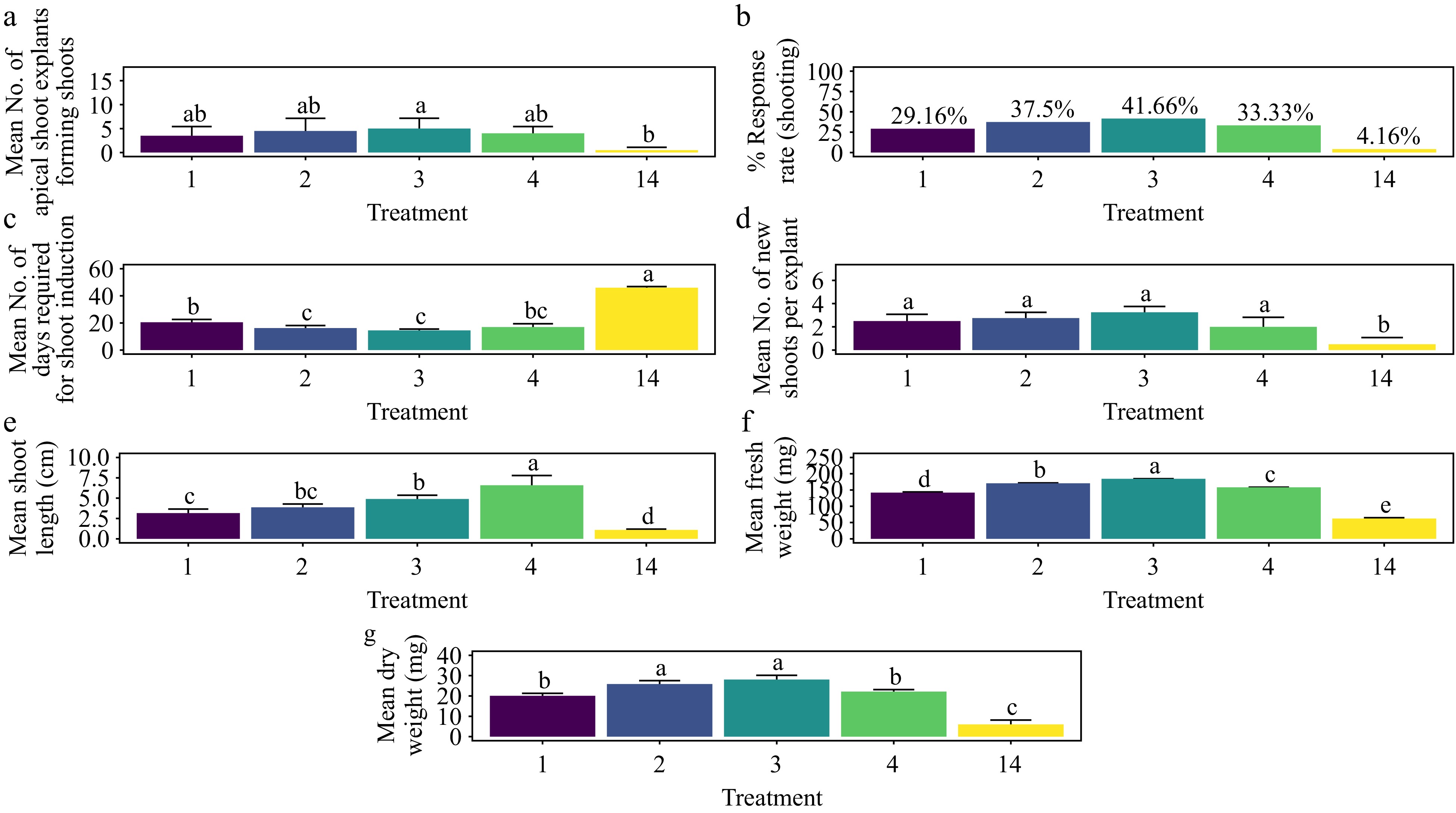

The treatment with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP demonstrated the highest rate of shoot morphogenesis, achieving a response rate of 41.7%. This rate was statistically comparable to all other treatments except the control (Fig. 10a & b) (p < 0.01). Additionally, 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP resulted in the fastest average shoot formation time of 14.5 d, which was significantly shorter than that observed with 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP (T1) and the control (Fig. 10c) (p < 0.001). The treatment also produced the highest average number of shoots per explant (3.25), with results not significantly different from other treatments except the control (Fig. 10d) (p < 0.001). For shoot length, the treatment with 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP yielded the longest average shoot length of 6.57 cm, significantly surpassing that of 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP (T1) and the control (Fig. 10e) (p < 0.001). In terms of shoot biomass, 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP also led to the highest average fresh weight (184 mg) and dry weight (28.0 mg). These results were significantly greater than those of the control and all other treatments, except for 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP (T2), which produced the second-highest fresh weight (171 mg) and dry weight (25.8 mg) (Fig. 10f & g) (p < 0.001). The base of the shoots showed no callus formation and the leaves showed no signs of hyperhydricity (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Figure 10.

Effect of PGRs on in vitro morphogenetic response (shoot multiplication) in apical shoot explant of Gloriosa superba L. (a) Mean apical shoot bud explants forming shoots, (b) response rate to shooting treatment, and (c) days required for shoot induction, (d) mean of new shoots per explant, (e) mean shoot length, (f) mean fresh weight of shoots, and (g) mean dry weight of shoots. Treatments were T1: 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP; T2: 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP; T3: 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP; T4: 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP; T14: Control (media without PGRs). Bars indicate mean ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test at p ≤ 0.05.

Treatment with BAP and NAA

-

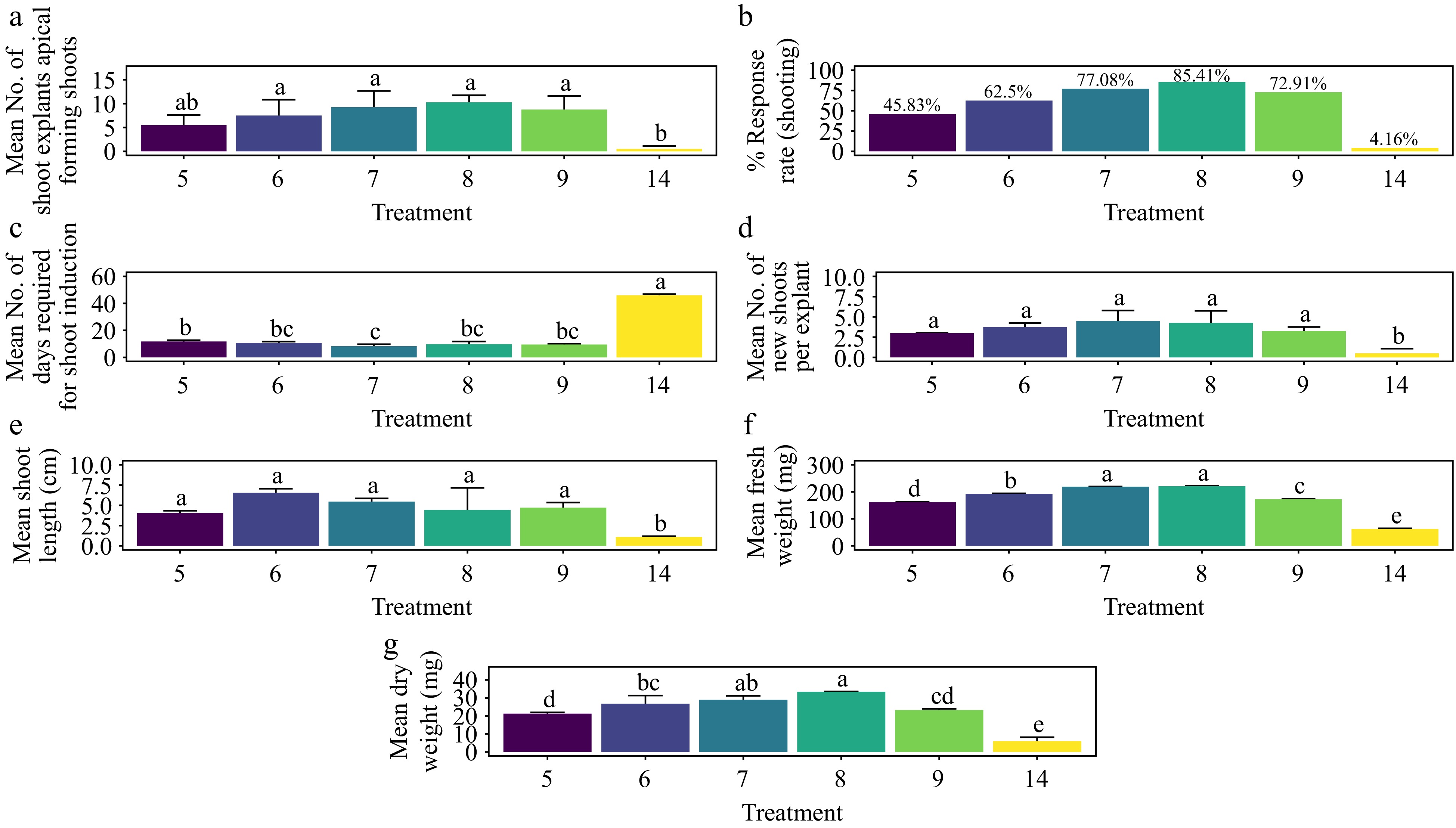

The treatment with 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.6 mg·L−1 NAA yielded the highest shoot morphogenesis response rate at 85.4%, which was statistically indistinguishable from other treatments except for the control (Fig. 11a & b) (p < 0.001). The fastest average shoot formation time of 8.25 days was achieved with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.4 mg·L−1 NAA, significantly different from the control and the 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.1 mg·L−1 NAA treatment (Fig. 11c) (p < 0.001). The highest average number of shoots per explant, at 4.5, was also observed with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.4 mg·L−1 NAA, with no significant difference from other treatments except the control (Fig. 11d) (p < 0.001). The longest average shoot length of 6.54 cm was recorded with 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.2 mg·L−1 NAA, which was comparable to other treatments, excluding the control (Fig. 11e) (p < 0.001). In terms of shoot biomass, the 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.6 mg·L−1 NAA treatment achieved the highest average fresh weight (220 mg) and average dry weight (33.4 mg), significantly outperforming all other treatments except for 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.4 mg·L−1 NAA, which had the second-highest results (219 mg fresh weight and 28.9 mg dry weight) (Fig. 11f & g) (p < 0.001). The base of the shoots showed no callus formation, and the leaves showed no signs of hyperhydricity (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Figure 11.

Effect of PGRs on in vitro morphogenetic response (shoot multiplication) in apical shoot explant of Gloriosa superba L. (a) Mean apical shoot bud explants forming shoots, (b) response rate to shooting treatment, and (c) days required for shoot induction, (d) mean of new shoots per explant, (e) mean shoot length, (f) mean fresh weight of shoots, and (g) mean dry weight of shoots. Treatments were T5: 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.1 mg·L−1 NAA; T6: 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.2 mg·L−1 NAA; T7: 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.4 mg·L−1 NAA; T8: 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.6 mg·L−1 NAA; T9: 2.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.8 mg·L−1 NAA; T14: Control (media without PGRs). Bars indicate mean ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test at p ≤ 0.05.

Treatment with KN

-

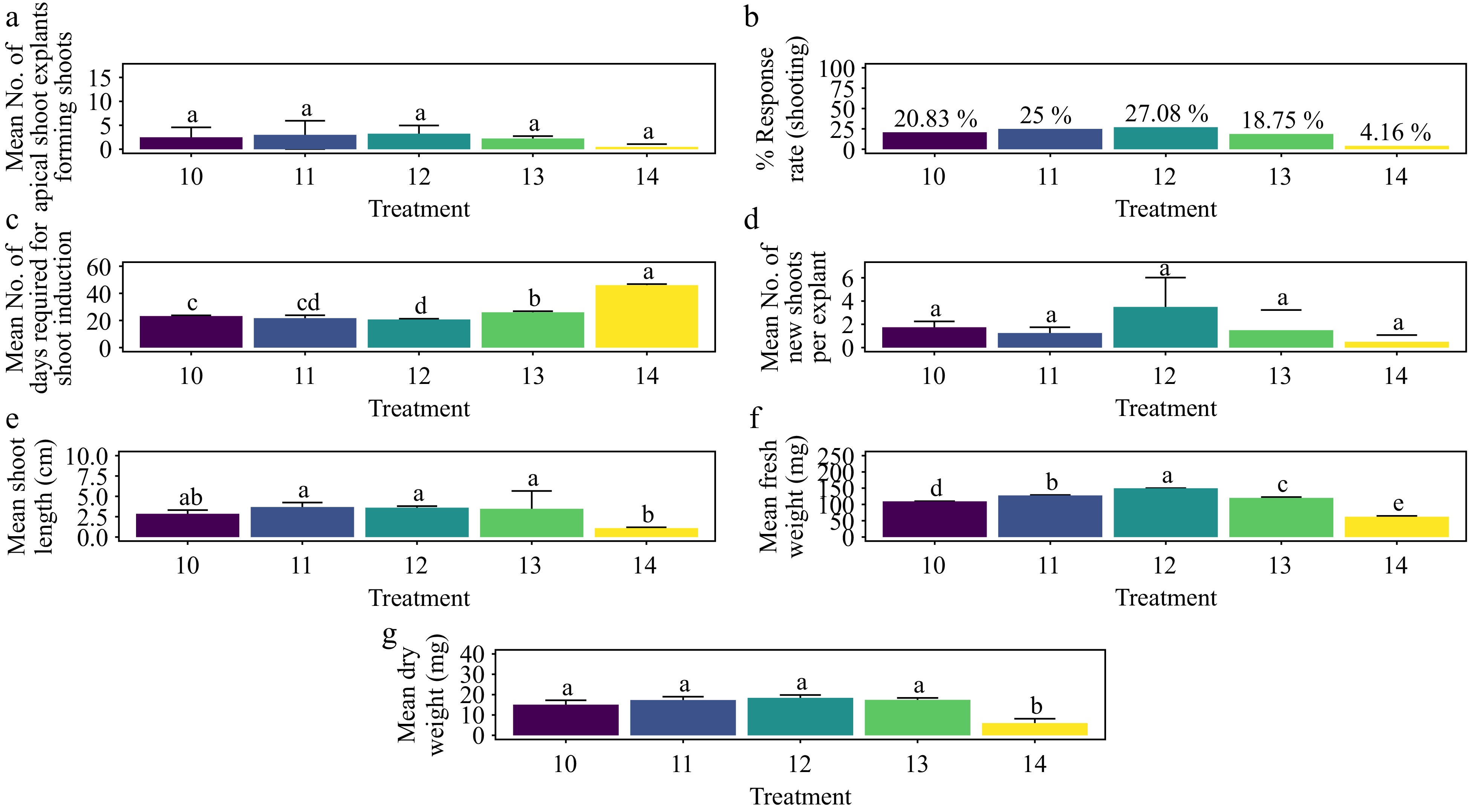

The treatment with 1.5 mg·L−1 KN yielded the highest shoot morphogenesis response rate of 27.08%, a result that was not significantly different from other treatments, including the control (Fig. 12a & b) (p > 0.276). This treatment also achieved the shortest average shoot formation time of 20.80 days, which was significantly faster compared to all treatments except T11 (1.0 mg·L−1 KN) (Fig. 12c) (p < 0.001). The highest average number of shoots per explant, 3.5, was recorded with 1.5 mg·L−1 KN, showing no significant difference from other treatments, including the control (Fig. 12d) (p > 0.0939). The treatment of 1.0 mg·L−1 KN resulted in the longest average shoot length of 3.68 cm, which was significantly different from the control but not from other treatments (Fig. 12e) (p < 0.01). In terms of shoot biomass, 1.5 mg·L−1 KN produced the highest average fresh weight (150 mg) and average dry weight (18.4 mg). These weights were significantly different from those of other treatments, except for dry weight, where the difference was not significant compared to all treatments except the control (Fig. 12f & g) (p < 0.001). The base of the shoots showed no callus formation, and the leaves showed no signs of hyperhydricity (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Figure 12.

Effect of PGRs on in vitro morphogenetic response (shoot multiplication) in apical shoot explant of Gloriosa superba L. (a) Mean apical shoot bud explants forming shoots, (b) response rate to shooting treatment, and (c) days required for shoot induction, (d) mean of new shoots per explant, (e) mean shoot length, (f) mean fresh weight of shoots, and (g) mean dry weight of shoots. Treatments were T10: 0.5 mg·L−1 KN; T11: 1.0 mg·L−1 KN; T12: 1.5 mg·L−1 KN; T13: 2.0 mg·L−1 KN; T14: Control (media without PGRs). Bars indicate mean ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test at p ≤ 0.05.

Effect of plant growth regulators on shoot morphogenesis in meristem explants

Treatment with BAP

-

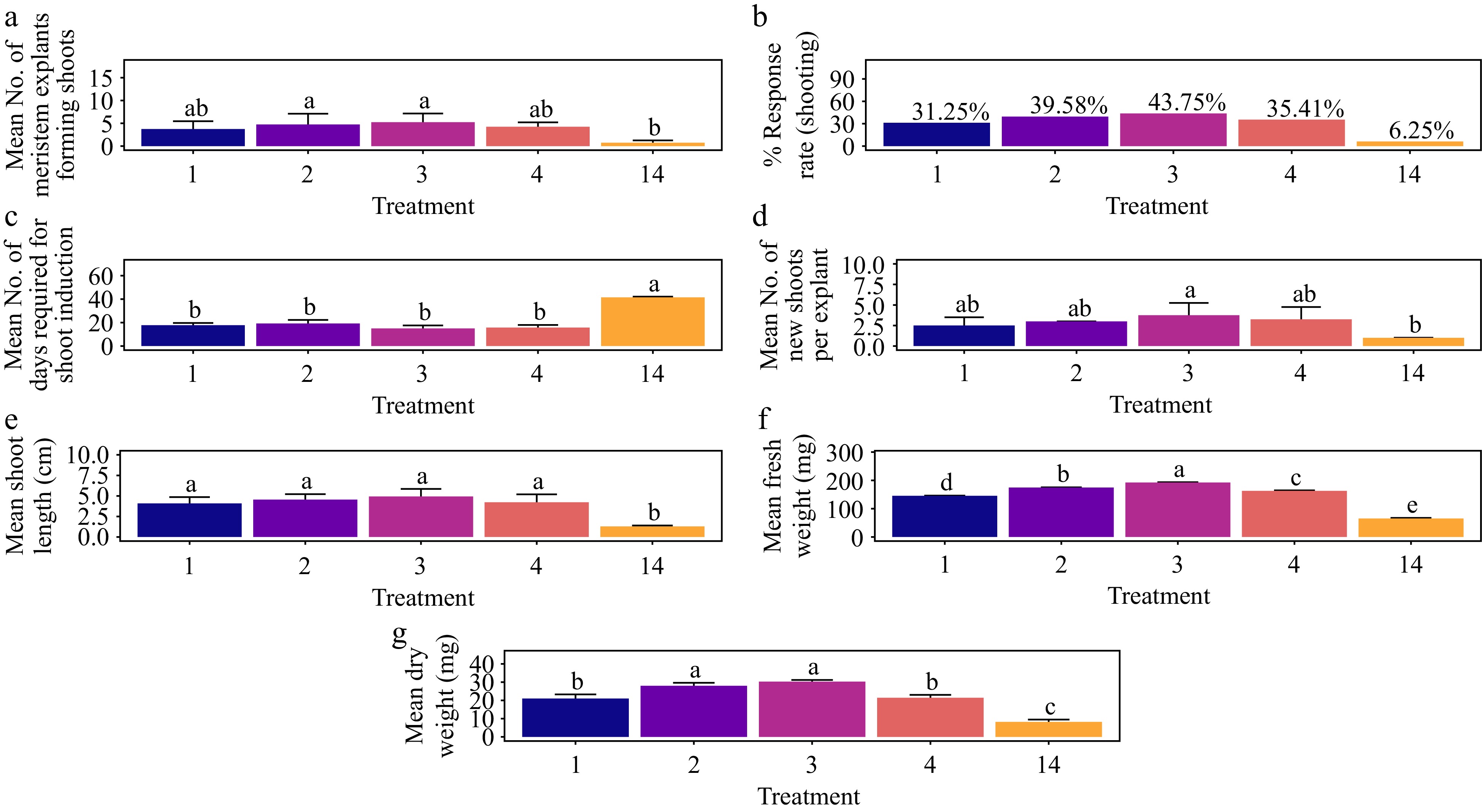

Treatment with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP yielded the highest shoot response rate at 43.8%, which was significantly greater than the control (p < 0.01), although not significantly different from other treatments (Fig. 13a & b). This concentration also resulted in the shortest average shoot induction time of 15 d, which was significantly shorter compared to the control (p < 0.001) but not significantly different from other treatments (Fig. 13c). The number of shoots per explant showed no significant differences among treatments, except for the control (p < 0.001). The treatment with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP produced the highest average number of shoots per explant (3.75), followed by T4 with 3.25 shoots per explant (Fig. 13d). Similarly, shoot length did not significantly vary among treatments other than the control (p < 0.001). The longest average shoot length was observed with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP (4.93 cm), followed by T2 (4.56 cm), T4 (4.22 cm), and T1 (4.09 cm) (Fig. 13e). Regarding shoot biomass, the 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP treatment resulted in the highest average fresh weight (192 mg) and dry weight (30.3 mg) of shoots. This treatment significantly differed from all others in fresh weight, and while the difference in dry weight was significant for all treatments, it was not significant when compared to T2 (1.0 mg·L−1 BAP) (Fig. 13f & g) (p < 0.001). Adventitious shoots were observed within four weeks of culture, although no root formation occurred. Additionally, no callus formation was noted at the base of shoots, and leaves did not exhibit hyperhydricity (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Figure 13.

Effect of PGRs on in vitro morphogenetic response (shoot multiplication) in meristem explant of Gloriosa superba L. (a) Mean meristem explants forming shoots, (b) response rate to shooting treatment, and (c) days required for shoot induction, (d) mean of new shoots per explant, (e) mean shoot length, (f) mean fresh weight of shoots, and (g) mean dry weight of shoots. Treatments were T1: 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP; T2: 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP; T3: 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP; T4: 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP; T14: Control (media without PGRs). Bars indicate mean ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test at p ≤ 0.05.

Treatment with BAP and NAA

-

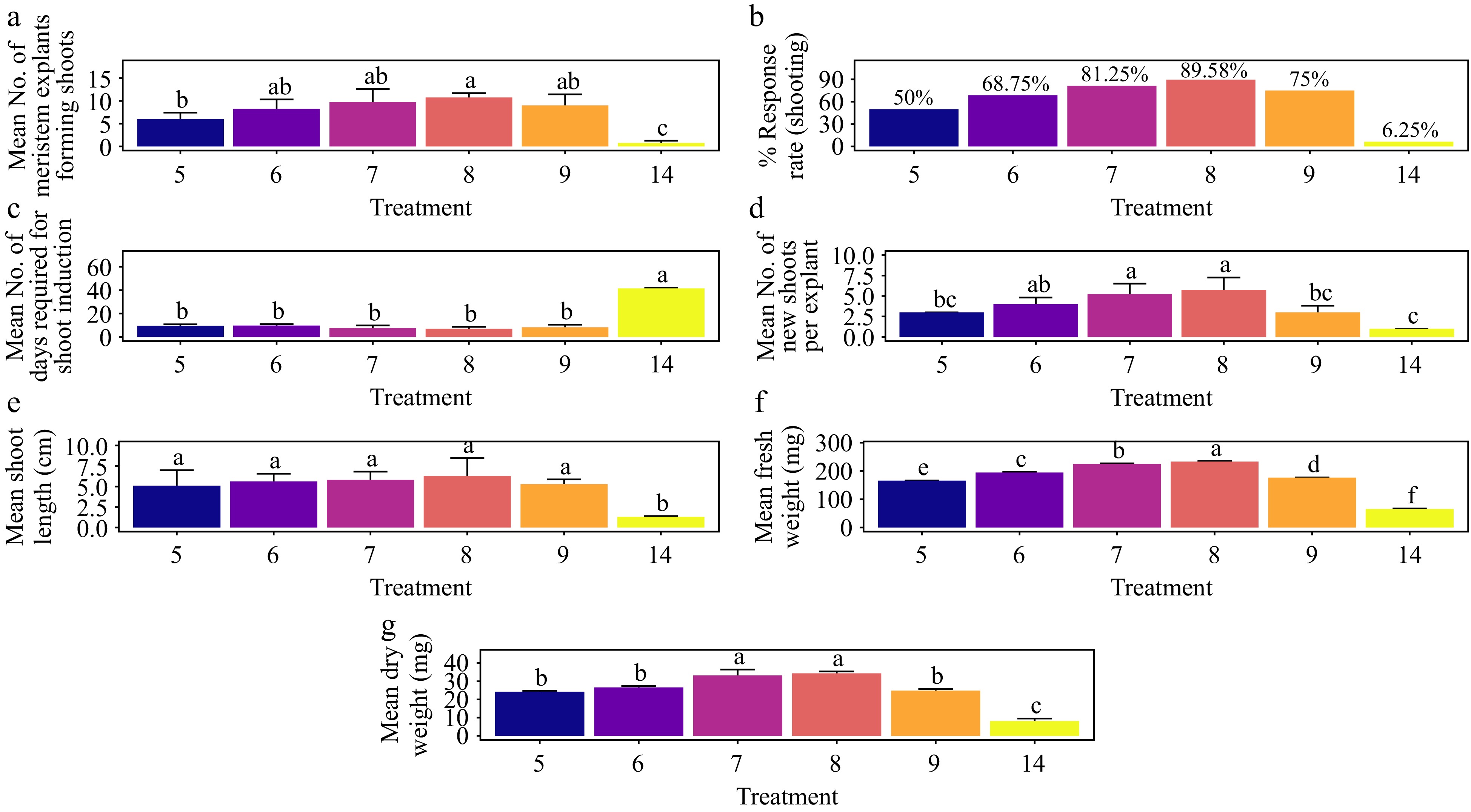

Treatment with 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.6 mg·L−1 NAA yielded the highest shoot response rate at 89.58%. This result was significantly greater compared to all other treatments except for T5 and the control (p < 0.001) (Fig. 14a & b). Additionally, this treatment resulted in the shortest average shoot induction time of 7 d, significantly differing from all treatments except the control (p < 0.001) (Fig. 14c). The highest average number of shoots per explant was also observed with 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.6 mg L−1 NAA, averaging 5.75 shoots per explant, followed by T7 with 5.25 shoots per explant (Fig. 14d). Most treatments showed no significant differences in the average number of shoots per explant, except for T5 (3), T9 (3), and the control (p < 0.001). Regarding shoot length, the treatment of 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.6 mg·L−1 NAA produced the longest average shoot length of 6.31 cm, surpassing T7 (5.82 cm), T6 (5.63 cm), and T9 (5.29 cm) (Fig. 14e). Shoot length did not significantly vary among treatments except for the control, where the differences were statistically significant (p < 0.001). For shoot biomass, 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.6 mg·L−1 NAA resulted in the highest average fresh weight (233 mg) and average dry weight (34.3 mg) of shoots. The fresh weight was significantly different from all other treatments, while the dry weight was significantly different from all treatments, including the control, except for T7 (1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.4 mg·L−1 NAA) (p < 0.001) (Fig. 14f & g). Adventitious shoots were noted within four weeks of culture, although no root formation occurred. The base of the shoots showed no callus, and the leaves showed no signs of hyperhydricity (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Figure 14.

Effect of PGRs on in vitro morphogenetic response (shoot multiplication) in meristem explant of Gloriosa superba L. (a) Mean meristem explants forming shoots, (b) response rate to shooting treatment, and (c) days required for shoot induction, (d) mean of new shoots per explant, (e) mean shoot length, (f) mean fresh weight of shoots, and (g) mean dry weight of shoots. Treatments are T5: 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.1 mg·L−1 NAA; T6: 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.2 mg·L−1 NAA; T7: 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.4 mg·L−1 NAA; T8: 2.0 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.6 mg·L−1 NAA; T9: 2.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.8 mg·L−1 NAA; T14: Control (media without PGRs). Bars indicate mean ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test at p ≤ 0.05.

Treatment with KN

-

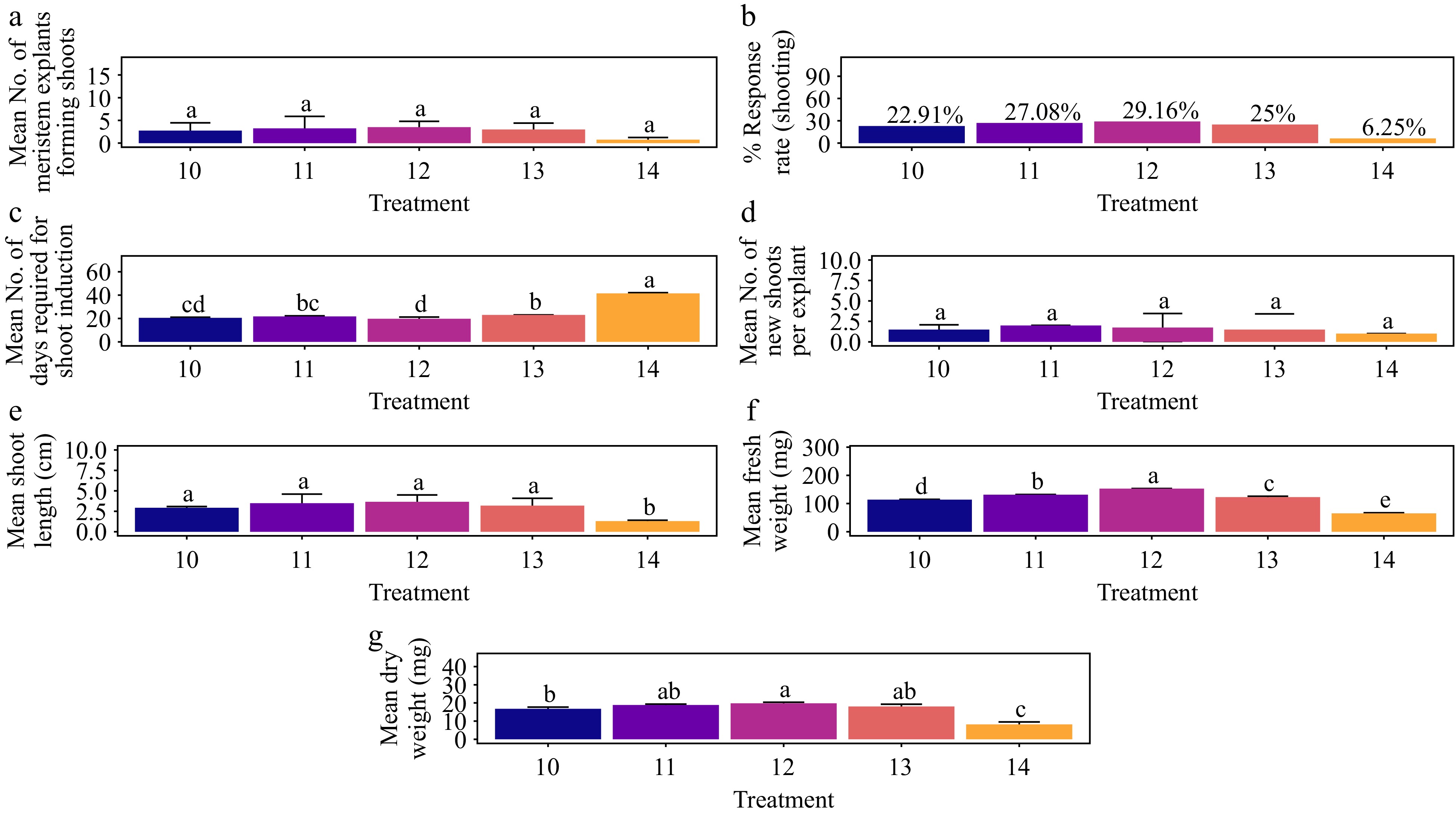

The treatment with 1.5 mg·L−1 KN achieved the highest shoot response rate at 29.16%, which was not significantly different from other treatments, including the control (p > 0.191) (Fig. 15a & b). This treatment also resulted in the shortest average shoot induction time of 19.8 days, significantly differing from all other treatments except for T10 (20.5 d) (p < 0.001) (Fig. 15c). The average number of shoots per explant did not show significant variation among the treatments (p > 0.807). However, the highest average number of shoots per explant (1.75) was observed with 1.5 mg·L−1 KN, followed by T13 and T10, both with 1.50 shoots per explant (Fig. 15d). Shoot length did not significantly vary among most treatments, except for the control (p < 0.001). The treatment with 1.5 mg·L−1 KN produced the longest average shoot length at 3.66 cm, followed by T11 (3.49 cm), T13 (3.19 cm), and T10 (2.92 cm) (Fig. 15e). In terms of shoot biomass, the 1.5 mg L-1 KN treatment resulted in shoots with the highest average fresh weight (153 mg) and dry weight (19.8 mg). This treatment significantly differed from all others in fresh weight, and in dry weight, it was significantly different from all treatments, including the control, except for T11 (1.0 mg·L−1 KN) and T13 (2.0 mg·L−1 KN) (Fig. 15f & g) (p < 0.001). Adventitious shoots were observed within four weeks of culture, although no rooting was noted. Additionally, no callus was observed at the base of the shoots, and the leaves did not exhibit hyperhydricity (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Figure 15.

Effect of PGRs on in vitro morphogenetic response (shoot multiplication) in meristem explant of Gloriosa superba L. (a) Mean meristem explants forming shoots, (b) response rate to shooting treatment, and (c) days required for shoot induction, (d) mean of new shoots per explant, (e) mean shoot length, (f) mean fresh weight of shoots, and (g) mean dry weight of shoots. Treatments were T10: 0.5 mg·L−1 KN; T11: 1.0 mg·L−1 KN; T12: 1.5 mg·L−1 KN; T13: 2.0 mg·L−1 KN; T14: Control (media without PGRs). Bars indicate mean ± SE. Different letters indicate significant differences by Tukey's test at p ≤ 0.05.

Effects of plant growth regulators on in vitro morphogenetic response to rooting of micro shoots

-

In all rooting experiments, roots were observed in all randomly selected shoots from various explants (Supplementary Fig. S12). The response of root formation varied depending on the type and concentration of auxin incorporated into the medium (Supplementary Fig. S8b). The highest rooting response rate (81.3%) was recorded at 1.0 mg·L−1 IBA, significantly differing from the control treatment, followed by 1.0 mg·L−1 IAA (72.9%), 1.5 mg·L−1 IBA (68.8%), and 1.0 mg·L−1 NAA (66.7%) (Supplementary Fig. S8a) (p < 0.001).

Treatment with 1.0 mg·L−1 IBA exhibited the shortest average root induction time (8 days), significantly differing from T7, T8, T9, T10, and the control (Supplementary Fig. S8c) (p < 0.001). The most extended average root length (4.64 cm) was achieved with 1.0 mg·L−1 IBA, followed by T5 (3.98 cm) and T1 (3.49 cm), which did not differ significantly from the other treatments except T4, T6, T7, T9 and the control (Supplementary Fig. S8d) (p < 0.001). Regardless of the explant source of the in vitro micro shoots, it was observed that 1.0 mg·L−1 IBA consistently yielded the best results (Supplementary Fig. S9b).

Ex vitro acclimatisation

-

The plantlets were successfully transferred ex vitro onto a substrate of sterilized vermiculite soil in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio. They were grown in a culture room for 14 d, followed by an additional 14 d under shade in a net house. During this period, the acclimatization rate reached 100%. However, by the fourth week, the survival rate dropped to 95% (Supplementary Fig. S10a). Subsequently, the plantlets were transferred to a substrate consisting of garden soil mixed with sand and vermiculite in a 2:1:1 (v/v) ratio. Over the next ten weeks, while exposed to direct sunlight, the survival rate further decreased to 60% (Supplementary Fig. S10a) meanwhile all surviving plants exhibited average plant height (146 cm), number of leaves per plant (12.9), flowering (3.14), and micro-tuber production (2.76), indicating significant differences (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. S10b−S10e & S11a−S11h).

-

The findings of this study on Gloriosa superba L. highlight the impact of the type, concentration, and combinations of plant growth regulators on various explant types, as well as their unique responses to in vitro culture conditions. All examined explants—apical shoot, meristem, nodal segment, non-dormant corm, and shoot tip—demonstrated responses to the tissue culture conditions employed. This study reaffirmed the well-established correlation between the auxin-to-cytokinin ratio in the medium and its impact on shoot morphogenesis, demonstrating that a higher cytokinin-to-auxin ratio favors shoot morphogenesis[26,32]. Furthermore, measuring shoot growth proved to be a critical metric for evaluating explant responsiveness. This provided valuable insights into the growth-promoting effects induced by specific media modifications, including the application of plant growth regulators (PGRs).

Effects of PGRs on shoot morphogenesis of nodal explants

-

6-Benzylaminopurine (BAP) is a first-generation cytokinin and a broad-spectrum plant growth regulator that plays a critical role in influencing plant growth and development. BAP promotes cell division, inhibits chlorophyll degradation, enhances amino acid content, and delays leaf senescence. Additionally, BAP can be used to artificially modify morphogenesis, improve resistance to environmental stressors, enhance photosynthetic efficiency, and regulate flowering, fruit, and seed production[33]. On the other hand, Thidiazuron (TDZ; N-phenyl-1,2,3-thiadiazole-5-yl urea) is a potent plant growth regulator widely used in tissue culture and micropropagation. When added to media such as Murashige and Skoog medium, TDZ can significantly promote or accelerate plant organogenesis, particularly shoot regeneration and overall plant regeneration. Originally developed as a defoliant, TDZ is a phenylurea compound with cytokinin-like activity. Notably, TDZ exhibits the unique capability to mimic both auxin and cytokinin effects on the growth and differentiation of cultured explants, despite being structurally distinct from both auxins and purine-based cytokinins by possessing two functional groups, phenyl, and thiadiazole[34].

Micropropagation through nodal explant culture is widely recognized as an efficient method for rapid clonal propagation, minimizing harm to the parent plant[31]. In this study, nodal explants were cultured on MS media supplemented with two distinct plant growth regulator treatments: one with varying concentrations of BAP alone and the other with a combination of BAP and TDZ. The nodal explants exhibited a favorable response to shoot morphogenesis, particularly with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP. This concentration was identified as optimal for both shoot proliferation and elongation, though it initiated shoot morphogenesis at a slightly slower rate compared to lower concentrations, such as 0.5 and 1.0 mg·L−1 BAP (Fig. 1). The superior performance of 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP in promoting shoot development suggests it is the most effective concentration for this genotype, balancing both the quantity and quality of shoot formation. These findings establish 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP as the optimal concentration for inducing shoot morphogenesis in the nodal explants of Gloriosa superba L.

Combining 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP with 0.2 mg·L−1 TDZ significantly enhanced the response of nodal explants to treatment (Fig. 2). This specific combination yielded the most optimal outcomes, resulting in the highest response rate of nodal explants to shoot induction, the shortest time required for shoot bud formation, and the most pronounced effects on shoot elongation and proliferation. These findings underscore the importance of the interaction between plant growth regulators and their concentrations in influencing shoot induction. The results indicate that the combination of BAP and TDZ is more effective at promoting shoot induction than BAP alone. This observation is consistent with previous research, which reported a synergistic effect of BAP and TDZ (each at 1.0 mg·L−1) on shoot proliferation in shoot tip explants of Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench[35]. Moreover, the current study suggests that TDZ accelerates the morphogenic response of nodal explants, though its effectiveness diminishes at concentrations above 0.2 mg·L−1 (Fig. 2).

A study on Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni observed similar results, identifying 1.25 mg·L−1 BAP as the optimal concentration for shoot induction from root explants and 0.5 mg·L−1 TDZ as the optimal concentration for the same explants. Additionally, when testing the synergistic effects of BAP and TDZ, the study found that a combination of 1.25 mg·L−1 BAP and 0.5 mg·L−1 TDZ yielded the highest shoot induction efficacy at 89.5% ± 0.707%. Deviations from these optimal concentrations, whether higher or lower, resulted in a significant decrease in shoot induction efficacy[36].

The results of this study reveal that even when using the optimal concentration of 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP (Fig. 1), the addition of higher concentrations of TDZ above 0.2 mg·L−1 led to a marked decrease in the response rate of nodal explants to shoot morphogenesis. Furthermore, BAP concentrations ranging from 2.0 mg·L−1 to 2.5 mg·L−1 exacerbated this decline in shoot morphogenesis (Fig. 2). These findings suggest that increasing TDZ concentration beyond 0.2 mg·L−1 exerts an inhibitory effect on shoot morphogenesis, indicating that TDZ has a limited range within which it synergistically enhances BAP activity.

This observation aligns with previous studies that reported lower synergistic interactions between TDZ and NAA compared to BAP and NAA[37]. Notably, the impact of varying concentrations of BAP and TDZ extended beyond shoot response frequency, affecting the duration of induction, shoot proliferation, and shoot length in a consistent manner (Fig. 2). These results suggest that the interaction between BAP and TDZ influences all aspects of the organogenic process in nodal explants, highlighting the complex dynamics of their combined effects.

In this experiment, the effect of TDZ alone on shoot morphogenesis in nodal explants of Gloriosa superba L. was not evaluated. However, TDZ alone is effective for shoot induction in various woody plant species[38]. Studies, for example, have demonstrated that TDZ outperforms BAP in promoting shoot induction in Musa spp. shoot tip explants, highlighting its superior efficacy compared to BAP[39]. Similarly, studies have reported that TDZ outperforms BAP in promoting shoot induction in the nodal segments of Camellia sinensis[37]. These findings suggest that TDZ has a strong potential for enhancing shoot morphogenesis across different plant species.

Effects of PGRs on shoot morphogenesis of non-dormant corm explants

-

Activated charcoal (AC) is composed of carbon arranged in a quasi-graphitic structure and is characterized by its small particle size, porosity, and tastelessness. The removal of non-carbon impurities and the oxidation of its surface distinguish AC from elementary carbon, creating a network of fine pores with an exceptionally large surface area and volume. This unique structure endows AC with high adsorption capacity, making it a valuable tool in plant tissue culture[40].

In plant tissue culture, AC is commonly added to both liquid and semi-solid media to enhance cell growth and development. Several factors contribute to its effectiveness: it adsorbs inhibitory substances from the culture medium reduces phenolic oxidation and brown exudate accumulation adjusts the medium's pH to optimal levels for morphogenesis, and creates a darkened environment that mimics soil conditions[41]. Although the impact of AC on plant growth regulator (PGR) uptake remains unclear, some researchers suggest that AC may gradually release adsorbed nutrients and PGRs, as well as substances inherently present in AC that promote plant growth. Additionally, AC aids in the removal of growth-inhibitory chemicals like 5-hydroxymethylfurfural, a product of sucrose dehydration during autoclaving[40].

Kinetin, or 6-Furfuryl-aminopurine, is a cytokinin growth regulator of plants. When used in plant tissue culture media, it can induce callus formation and tissue regeneration from callus. Kinetin has also been shown to be effective at inducing shoot formation in various plant species. For instance, a prior study that compared various cytokinins including BAP, KN, TDZ, and Zeatin each at a concentration ranging from 0 to 3 mg·L−1 reported that KN was the most effective for inducing shoots from nodal explants of cucumber. The maximum rate of regeneration, shoot proliferation per explant, and longest shoots were obtained on MS medium fortified with 1 mg·L−1 KN[42].

Adenine, particularly in the form of adenine sulfate (ADS), is commonly used as an additive in plant cell culture. ADS significantly stimulates cell growth and enhances shoot formation[43]. It acts synergistically with other plant growth regulators (PGRs) and either serves as a precursor for cytokinin synthesis or boosts the biosynthesis of natural cytokinins. Additionally, cells more readily assimilate ADS as an alternative nitrogen source compared to inorganic nitrogen sources. ADS's role is particularly notable in the mass multiplication of in vitro regenerants, where it effectively functions as a plant growth regulator. Its beneficial effects are often observed when used in conjunction with cytokinins, such as BAP. Various plant species consistently highlight the stimulatory impact of ADS on shoot multiplication[44].

In this study, non-dormant corm explants of Gloriosa superba L. were cultured on MS medium supplemented with varying concentrations of BAP or KN, ranging from 0 to 2.5 mg·L−1, in combination with either 1.5 mg·L−1 AC or 10 or 20 mg·L−1 ADS (Table 2). The results indicate that 1.5 mg·L−1 was the optimal concentration for both BAP and KN when used in conjunction with 1.5 mg·L−1 AC (Figs 3 & 4). Notably, BAP demonstrated a higher response rate for shoot induction in non-dormant corm explants compared to KN, suggesting that BAP is more effective than KN in promoting shoot formation in Gloriosa superba L. This finding aligns with previous research showing that BAP is superior to KN for shoot multiplication in Indigofera zollingeriana Miq[45]. However, studies involving cucumber have reported contrasting results, showing that KN was more effective than BAP for shoot induction[42]. These discrepancies highlight that the relative efficacy of BAP and KN can vary significantly across different plant species, emphasizing the need for species-specific optimization of cytokinin applications.

Significantly enhanced outcomes in response rate, induction duration, shoot proliferation, and shoot elongation were observed when the optimal concentration of either BAP or KN was combined with ADS (Figs 5 & 6). Notably, the combination of ADS with BAP consistently outperformed the combination with KN across all measured parameters, indicating that BAP exhibits superior synergistic effects with ADS compared to KN. This finding aligns with a previous study on Gloriosa superba L. corms, which reported more effective shoot multiplication when cultures were supplemented with BAP and ADS in MS medium compared to those with BAP alone[24].

In contrast to AC, which primarily functions to maintain pH and mimic soil conditions, ADS significantly enhanced the effects of both BAP and KN. This underscores the pronounced impact of ADS on all measured parameters. Although AC may have had a beneficial effect on shoot morphogenesis, this effect cannot be definitively proven due to the absence of a positive control using BAP alone at an optimal concentration of 1.5 mg·L−1. Thus, while AC's role in improving shoot morphogenesis cannot be ruled out, its effects appear limited relative to the enhanced outcomes achieved with ADS.

Effects of PGRs on shoot morphogenesis of shoot tip explants

-

Shoot tips are the most widely utilized method for micropropagation in commercial production due to their numerous advantages. Compared to alternative micropropagation techniques, shoot cultures offer several distinct benefits: (1) they achieve reliable and consistent multiplication rates after culture stabilization; (2) they exhibit reduced susceptibility to genetic variation, ensuring uniformity across propagated plants; and (3) they facilitate the clonal propagation of periclinal chimeras, preserving desired traits and enhancing production efficiency[46,47]. This study evaluated the efficacy of BAP combined with ADS, as well as BAP combined with TDZ and ADS, for inducing shoot morphogenic responses in shoot tip explants of Gloriosa superba L. This investigation assessed the synergistic effect of each type of combination on shoot regeneration and development.

For non-dormant corm explants, the combination of 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP with 10 mg L−1 ADS yielded the highest response rate of 91.7%, outperforming all other treatments. In contrast, the shoot tip explants treated with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP and 5 mg·L−1 ADS exhibited a lower response rate of 47.2%, which fell short of expectations (Figs 5 & 7). These findings support the conclusion that 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP is the optimal concentration for inducing shoot morphogenesis, as it consistently produced the highest response rates across different treatments. The lower response observed with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP and 5 mg·L−1 ADS suggests that the concentration of ADS was insufficient to fully enhance the effects of BAP. Conversely, the superior response rate with non-dormant corm explants at 10 mg·L−1 ADS implies that this concentration might offer a better synergistic effect with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP. Therefore, it is plausible that a higher concentration of ADS could also improve the efficacy of BAP in shoot tip explants.

Although this study did not explore the effect of varying concentrations of ADS beyond 8 mg·L−1, the combination of optimal BAP and TDZ concentrations with 8 mg·L−1 ADS yielded the most effective shoot morphogenesis in shoot tip explants of Gloriosa superba L. (Fig. 8). Notably, this combination also resulted in the shortest shoot induction period of 6 d, the shortest observed among all explant types (Fig. 9c). These findings suggest that 0.2 mg·L−1 TDZ synergistically enhanced the effect of 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP and 8 mg·L−1 ADS, thereby optimizing shoot morphogenesis in shoot tip explants.

It is possible that increasing the ADS concentration to 10 mg·L−1 might have further improved the results, though this was not tested in the present study. Furthermore, higher concentrations of BAP and TDZ than the optimal levels of 1.5 and 0.2 mg·L−1, respectively, were found to decrease the effectiveness of shoot morphogenesis, even with the optimal ADS concentration of 10 mg·L−1 (Fig. 9). This supports the conclusion that 0.2 mg·L−1 TDZ is the optimal concentration for promoting shoot morphogenesis in Gloriosa superba L., consistent with findings for nodal explants in this study.

Previous studies have demonstrated that TDZ exhibits a strong synergistic effect with BAP at lower concentrations, resulting in an optimal shoot response from node explants of Quercus rubra L.[48]. In contrast, other research has shown that while lower TDZ concentrations are effective in stimulating axillary shoot proliferation across various woody plants, higher concentrations of TDZ can lead to the formation of both axillary and adventitious shoots in Fraxinus pennsylvanica Marsh.[49]. This discrepancy highlights the varying responses of different species to TDZ concentration, emphasizing the need for species-specific optimization in plant tissue culture protocols.

Effects of PGRs on shoot morphogenesis of apical shoot and meristem explants

-

The apical shoot comprises the shoot apical meristem and the young, developing tissues that arise from it. It represents the growing tip of a shoot, where elongation primarily occurs. Shoot apical meristems are crucial for plant development as they generate essential structures such as leaves, stems, axillary meristems, and roots[50]. The efficiency of plant regeneration is highly dependent on the precise regulation of shoot apical meristem growth and density[51]. This regulation is critical not only for normal developmental processes but also as a key adaptive mechanism, enabling plants to respond to environmental changes and recover from injuries.

Consistent with findings from other explants in this study, both 1.5 mg·L−1 of BAP and 1.5 mg·L−1 of KN were identified as optimal cytokinin concentrations for inducing shoot morphogenesis in apical shoot and meristem explants of Gloriosa superba L. (Supplementary Figs S4, S8−S10). Additionally, BAP consistently outperformed KN across all evaluated parameters, reinforcing its superior efficacy in promoting shoot development (Supplementary Figs S4, S8−S10).

Treatment with 2.0 mg L−1 BAP combined with 0.6 mg·L−1 NAA produced the highest shoot response rates for apical shoot and meristem explants, at 85.41% and 89.58%, respectively. Treatments with 1.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.4 mg·L−1 NAA and 2.5 mg·L−1 BAP + 0.8 mg·L−1 NAA followed suit (Figs 11 & 14). These results indicate that meristem explants exhibit higher responsiveness compared to apical shoot explants (Supplementary Table S5). In both types of explants, the observed synergy between BAP and NAA appears to have a positive influence on shoot morphogenesis.