-

Pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch.) is a species belonging to the Cucurbitaceae family. Pumpkins and pumpkin byproducts (seeds, leaf, and skin/peel) are widely used as functional foods by people because of their various bioactive compounds, including Selenium (Se)[1]. Se is thought of as an indispensable trace element for human health[2], while it has one of the narrowest ranges between dietary deficiency (< 40 μg·d−1) and toxicity (> 400 μg·d−1)[3]. Plants are the primary source of dietary Se for humans and animals, as they absorb inorganic Se from the soil and convert it into organic forms[4]. Se concentrations in most global soils are low (ranging from 0.01 to 2.0 mg·kg−1, mean ~0.4 mg·kg−1), except in seleniferous soils associated with specific geological features where concentrations can exceed 10 mg·kg–1[4]. Biofortification is a key strategy to alleviate Se deficiency in low-Se regions, while phytoremediation is employed in seleniferous areas to mitigate Se toxicity[4].

While the essentiality of Se for higher plants remains uncertain, it can enhance plant growth, quality, and tolerance to diverse biotic and abiotic stresses[5,6]. Previous studies have reported that Se can enhance the activities of antioxidant enzymes, such as catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD), and superoxide dismutase (SOD), thereby mitigating stress-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation in plants[7−11]. However, at high concentrations, Se becomes phytotoxic and results in Se stress for plant growth, such as damaging plant cells and inhibiting shoot and root growth[8,12−14]. Se toxicity primarily arises from two mechanisms: the misincorporation of Se-amino acids (e.g., selenocysteine [SeCys], selenomethionine [SeMet]) into proteins, leading to malfunctional proteins, and the induction of oxidative stress[4,5,11]. Grant et al.[15] demonstrated an interconnection between glutathione (GSH) depletion and ROS accumulation during Se stress in Arabidopsis. Melatonin (MT), recognized as a scavenger of stress-induced ROS[16], has been shown to alleviate Se stress in grapevines[14].

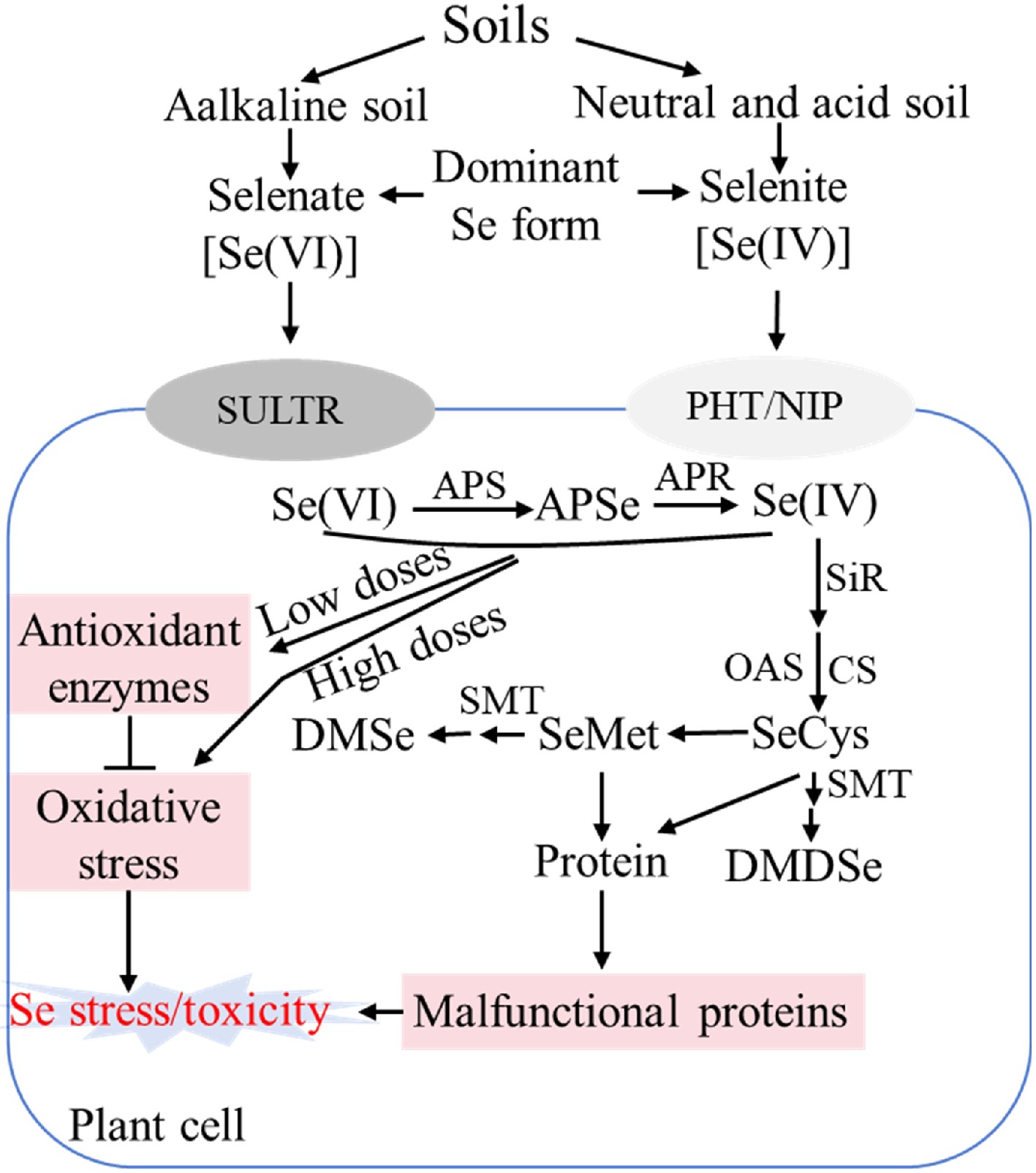

Selenite (Se[IV]) and Selenate (Se[VI]) are the dominant forms of Se available to plants in soil, and Se(IV) dominates in neutral and acidic soils, whereas Se(VI) prevails in alkaline soils[17]. Owing to the high chemical similarity between Se and sulfur (S), both Se(IV) and Se(VI) are assimilated via the S metabolic pathway[4]. Additionally, Se(IV) uptake is primarily mediated by phosphate transporters (PHTs) and nodulin 26-like intrinsic proteins (NIPs), and it is readily converted to SeCys and other organic forms through the S assimilation pathway[17]. Se(VI) is first reduced to Se(IV) by ATP sulfurylase (APS) and APS reductase (APR) in plants; subsequently, Se(IV) is reduced to selenide (H2Se− or Se2−) by sulfite reductase (SiR); Selenide is then incorporated into O-acetylserine (OAS) by cysteine synthase (CS) to form SeCys; SeCys can be further metabolized to other compounds, such as SeMet, by a series of enzymes[17]. The Se assimilation and roles in plants have been briefly summarized and presented in Fig. 1. Lintschinger et al.[18] observed significant interspecific variation in Se absorption rates. Overexpression of genes involved in Se metabolism enhances Se accumulation capacity[19,20]. Thus, it is essential to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of plant Se responses and identify key Se metabolism-related genes, which could facilitate genetic engineering approaches for biofortification and phytoremediation.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram showing selenium assimilation pathway and roles in plants. SULTR: Sulfate transporter; PHT: Phosphate transporter; NIP: Nodulin 26-like intrinsic protein. APS: ATP sulfurylase; APSe: Adenosine phosphoselenate; APR: APS reductase; SiR: Sulfite reductase; CS: Cysteine synthase; OAS: O-acetylserine; SeCys: Selenocysteine; SeMet: selenomethionine. SMT: Selenocysteine methyltransferase; DMSe: non-toxic dimethylselenide; DMDSe: dimethyldiselenide; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; Se: Selenium.

Pumpkin is widely cultivated globally, serving not only as a food source but also as a valuable rootstock for other cucurbit crops[21]. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying selenite uptake and metabolism in pumpkin remain poorly understood. In this study, physiological and transcriptomic analyses were performed to investigate selenite-induced responses in C. moschata, focusing on selenite toxicity, uptake, and metabolism mechanisms in roots. The findings will improve the understanding of Se accumulation and selenite tolerance in pumpkin. The genetic components identified herein provide a theoretical basis for improving selenite toxicity responses in pumpkin seedlings and inform future breeding and cultivation of Se-enriched pumpkin varieties.

-

The C. moschata used in this study, designated WCO39, was provided by the Chinese Vegetable Germplasm Resources Intermediate Bank, and the experiments were carried out in Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, Henan Province, China. Seeds of WCO39 germinated at 28 °C with shaking at 150 rpm on a shaker, were then sown into hole trays within a growth chamber under the following conditions: photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of 200 μmol·m−2·s−1, 16 h light (25 °C)/8 h dark (20 °C) photoperiod. Five days after sowing, uniform seedlings were transferred to 1 L plastic containers filled with half-strength Hoagland's nutrient solution (pH = 6.0) for 3 d. Seedlings were then divided into six groups and irrigated with solutions containing Na2SeO3 at concentrations of 0 (Se0), 2 (Se2), 10 (Se10), 20 (Se20), 40 (Se40), or 80 (Se80) μM. Each treatment group consisted of twelve seedlings, with three biological replicates. The nutrient solution was renewed every 3 d. A schematic of the seedling culture and treatment procedure is provided in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Melatonin (MT) treatment experiments followed the previous study[22]. Briefly, seedlings at the first true leaf stage were divided into four groups: (1) Control (Se0): normal nutrient solution + foliar spray of water; (2) MT100: normal nutrient solution + foliar spray of 100 μM MT; (3) Se40: nutrient solution containing 40 μM Na2SeO3 + foliar spray of water; (4) Se40MT100: nutrient solution containing 40 μM Na2SeO3 + foliar spray of 100 μM MT. Each group consisted of twelve seedlings, with three biological replicates. Foliar application of 100 μM MT (approximately 5 mL per plant) was performed daily at 18:00.

Physiological analysis

-

Phenotypic analysis for selenite concentration experiments was conducted after 10 d of treatment, and after 13 d for melatonin treatment experiments. Plant height, petiole length, leaf length, and leaf width were measured using a ruler. Hypocotyl diameter was measured using a digital vernier caliper. To determine dry weight (DW), fresh samples were oven-dried at 105 °C for 15 min, followed by drying at 80 °C for 48 h. Both fresh weight (FW) and DW were measured using a microbalance. Chlorophyll was extracted from the second true leaves by homogenization in 80% (v/v) acetone. Absorbance of the extracts was read at 663 and 646 nm using a UV-1800 spectrophotometer[22].

Malondialdehyde (MDA) content and relative electrical conductivity (REC) of the second true leaves were determined as described previously[23]. Superoxide anion (O2·−) accumulation in leaves was visualized via nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) staining[22], by which O2·− was shown as a blue dot because of NBT reduction. Briefly, leaves were immersed in a 0.1% NBT solution (pH = 6.4) containing 10 mM sodium azide. The samples were then incubated in darkness at 28 °C until blue spots appeared. For proper visualization, the chlorophyll in leaves was removed with absolute ethanol.

Determination of Se and S contents

-

To measure the contents of Se and S in the shoots and roots of WCO39 seedlings, the above and below-ground parts were separated and oven-dried at 80 °C for 48 h. The concentrations of total Se and total S were determined according to the Standard Methods GB 5009.93–2010 and GB 5009.268–2016 developed by the Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China. Accordingly, the dried samples were ground into powder and digested with nitric acid overnight, then put in a constant temperature drying oven maintained at 80 °C for 2 h, followed by 120 °C for 2 h, and finally 160 °C for 4 h. The concentrations were examined using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (NexlON®2000 ICP-MS, PerkinElmer Instrument Co., USA).

For the determination of inorganic Se in shoots and roots, the dried samples were added to hydrogen chloride as described by Li et al.[24]. Samples were placed in a constant temperature water bath at 70 °C, shaken for 2 h, filtered through absorbent cotton, boiled in a water bath for 20 min, and then potassium ferricyanide was added. The concentration of inorganic Se was determined by hydride generation atomic fluorescence spectrometry (HG-AFS, AFS820, Beijing Jitian Instrument Co., China).

As described by Li et al.[24], the concentrations of organic Se in shoots and roots were calculated using the formula: Seorganic = Setotal – Seinorganic, in which Seorganic, Setotal, and Seinorganic represented the organic Se concentration, total Se concentration, and inorganic Se concentration, respectively.

RNA-seq

-

The roots of WCO39 seedlings were harvested at 24 h under 40 μM selenite treatment (Se40) and normal conditions (Se0) with three biological replicates each treatment. Total RNA was isolated and prepared from roots as per the previous study[23]. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was performed using the Illumina sequencing platform at Biomarker Tech. Co. (Beijing, China). HISAT2[25] was used to map the clean reads to the C. moschata reference genome[26], and StringTie[27] was applied to assemble the mapped reads. Gene expression levels were quantified using the fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments (FPKM) mapped method. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using DEseq2[28] with a threshold of false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.01 and |log2 FC (fold change)| ≥ 1. Transcripts were annotated using the following databases: NCBI non-redundant protein (NR), Swiss-Prot (a manually annotated, non-redundant protein database), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Gene Ontology (GO), Protein family (Pfam), euKaryotic Ortholog Groups (KOG), Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins (COG), and Evolutionary Genealogy of Genes: Non-supervised Orthologous Groups (eggNOG).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

-

qRT-PCR was used to validate the RNA-seq results. The qualified RNA was transcribed into cDNA using the MonScript™ RTIII All-in-One Mix with dsDNase (Monad, Wuhan, China) based on the manufacturer's instructions. All samples were examined in triplicate. Gene-specific primers were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 software and are listed in Supplementary Table S1. qRT-PCR was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 thermocycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using Super-Real PreMix Plus (SYBR Green) (TIANGEN Biotech Co., Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The expression levels of all target transcripts were normalized to the housekeeping gene actin[29].

-

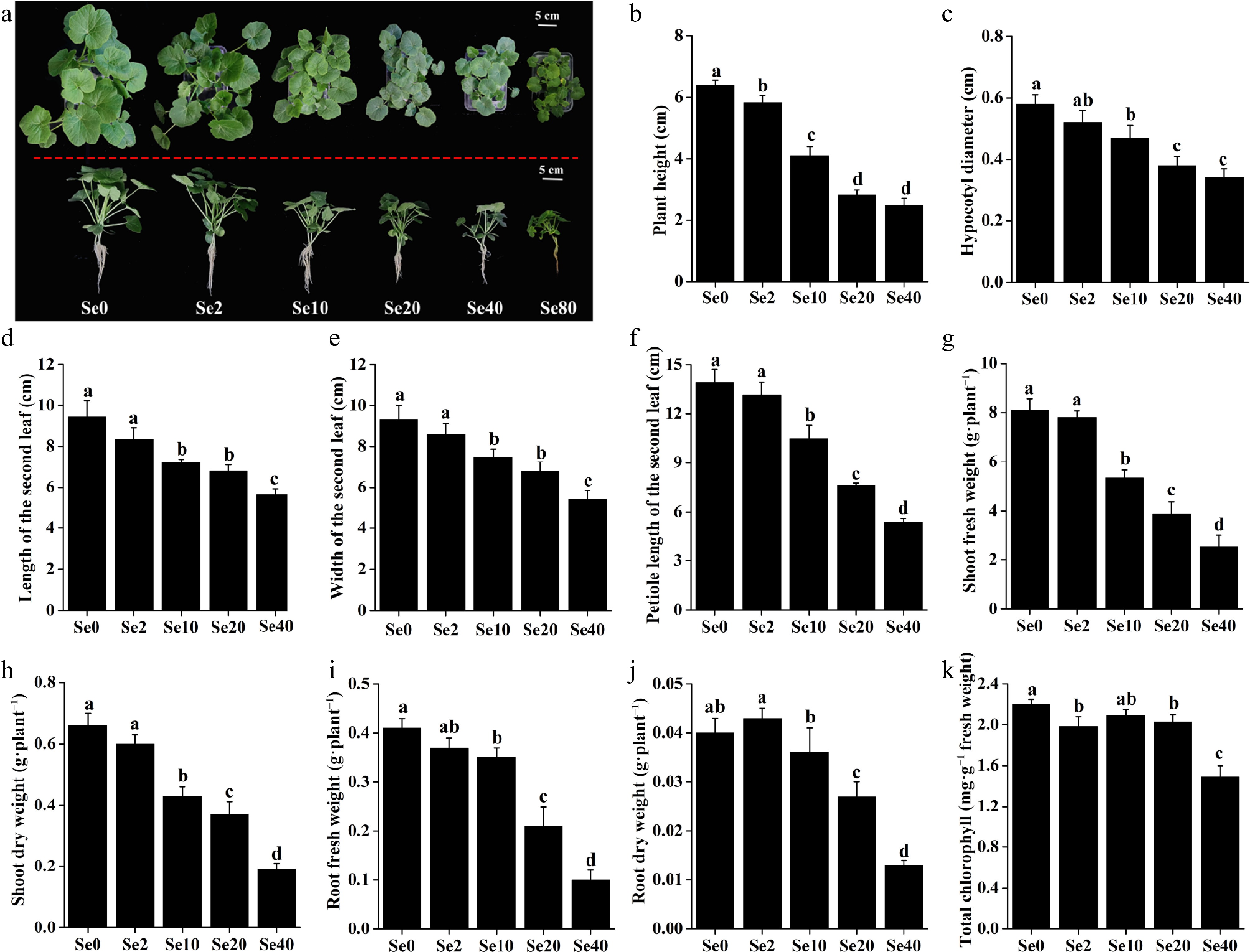

As shown in Fig. 2a, the growth of WCO39 seedlings was significantly affected by different concentrations of selenite. In terms of plant growth phenotype, 2 μM selenite (Se2) significantly decreased the plant height by 8.90% (Fig. 2b), but had no significant effect on the hypocotyl diameter, leaf size, and petiole length compared to the control (0 μM selenite, Se0) (Fig. 2c–f). All these parameters were significantly reduced under the other concentrations of selenite, and the inhibitory effects became more pronounced as the concentration increased. Similarly, the fresh and dry weight of WCO39 seedling shoots and roots were not significantly affected under Se2 treatment, but decreased under higher concentrations of selenite, and the suppression intensified with increasing selenite concentration (Fig. 2g–j).

Figure 2.

Effects of different selenite concentrations on the growth of WCO39 seedlings. (a) Phenotypes after 10 d of selenite treatment with different selenite concentrations. The aerial and lateral views of WCO39 seedlings are shown. (b)–(k) Statistical analysis of different growth parameters resulting from different doses of selenite. Different small letters on the bars stand for significant differences at p < 0.05 according to Duncan's multiple scope tests. Se0, Se2, Se10, Se20, Se40, and Se80 represent 0, 2, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μM selenite treatment, respectively.

Se2 and Se20 treatments significantly reduced the content of total chlorophyll in WCO39 seedling leaves by 10% and 7.72%, respectively, compared to the control (Fig. 2k). It is worth noting that Se40 treatment decreased plant height by 61.41%, hypocotyl diameter by 41.38%, leaf length by 40.30%, leaf width by 42.12%, Petiole length by 61.37%, shoot fresh weight by 68.73%, shoot dry weight by 71.21%, root fresh weight by 75.61%, root dry weight by 67.50%, and total chlorophyll content by 32.27%, compared to Se0 treatment (Fig. 2), indicating the serious inhibition of plant growth under Se40 treatment. Moreover, the results showed that plants treated with 80 μM selenite (Se80) exhibited more pronounced symptoms of growth suppression, leaf chlorosis, and root necrosis (Fig. 2a). These results demonstrated the serious toxicity of high selenite concentrations to C. moschata.

Influence of selenite on the physiological parameters in WCO39 seedlings

-

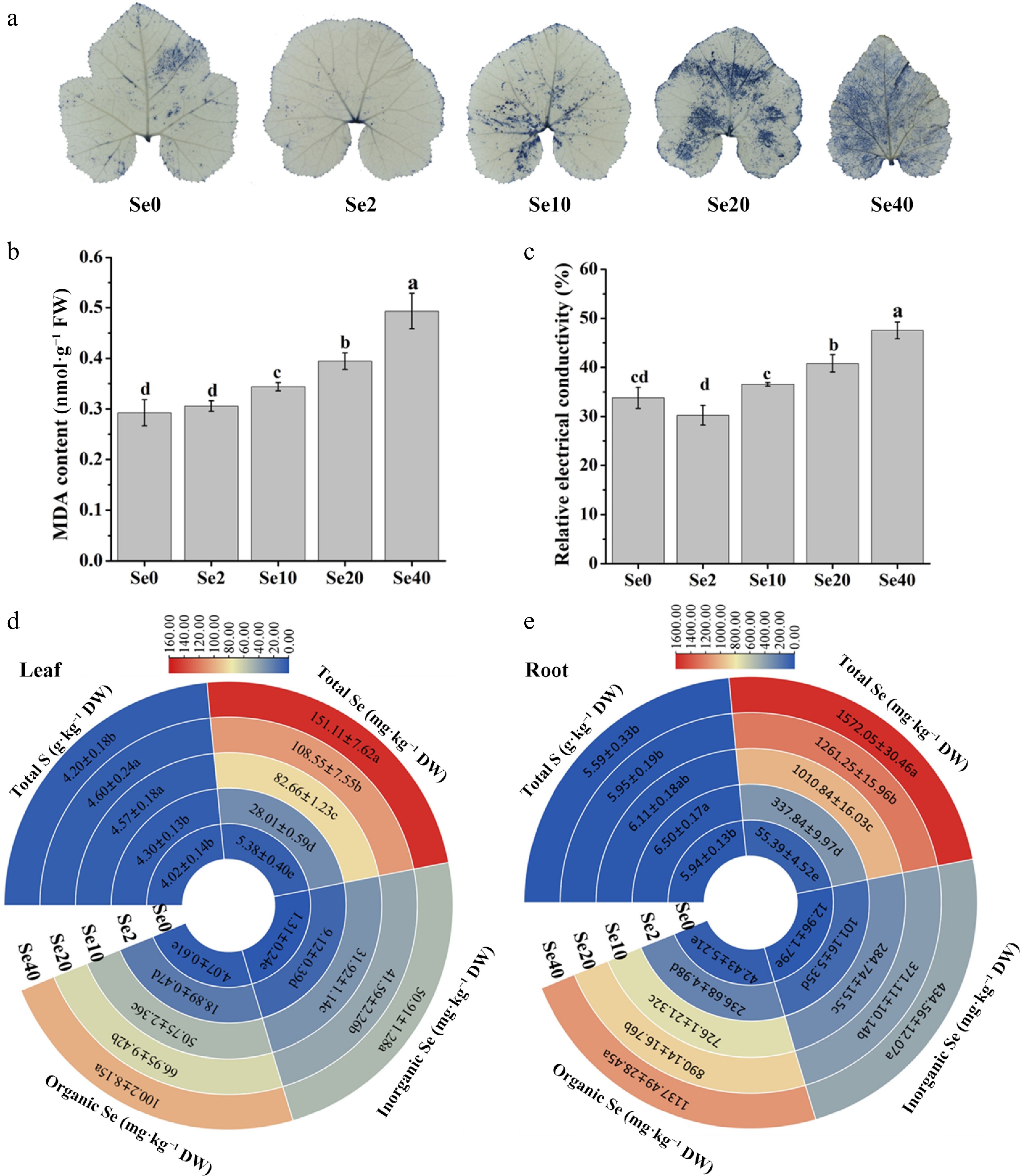

O2·− accumulation in leaves was assessed and visualized by NBT staining (Fig. 3a). Compared to Se0 leaves, the intensity of the navy blue color (reflecting O2·− level) appeared reduced in Se2 leaves, while it was not significant in Se10 leaves. Leaves exposed to 20 and 40 μM selenite exhibited a more pronounced navy blue color compared to other treatments, indicating excessive O2·− accumulation in leaves under high selenite doses.

Figure 3.

Influence of selenite on various physiological parameters in WCO39 seedlings. (a) Accumulation of O2·− in leaves visualized by NBT staining. (b) MDA content. (c) Relative electrical conductivity. (d), (e) Heatmaps showing the content of total S, Se, inorganic Se, and organic Se in leaves and roots, respectively. Se0, Se2, Se10, Se20, Se40, and Se80 represent 0, 2, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μM selenite treatment, respectively. The data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). Different small letters on the bars and heatmaps stand for significant differences at p < 0.05 according to Duncan's multiple scope tests.

MDA content and REC in leaves were measured to assess the effects of selenite on membrane lipid peroxidation and permeability. The results showed that the MDA content and REC in Se2 leaves were similar to Se0, but increased rapidly under higher selenite concentrations (10 and 40 μM) (Figs 2c & 3b). Compared to Se0, Se20 treatment increased MDA levels by approximately 35% and REC by 21%, while Se40 increased MDA by about 69% and REC by 57%. These results indicate that high doses of selenite induce membrane lipid peroxidation and increase membrane permeability in WCO39 leaves.

The effects of selenite treatment on S and Se contents in WCO39 seedlings were also analyzed (Fig. 3d, e). Compared to the control, S content was unaffected by Se2 in leaves, while it was increased slightly in roots. In contrast, both Se10 and Se20 treatments increased S content in leaves but not in roots. However, Se40 almost had no effect on the S contents in both leaves and roots compared with the control. In summary, selenite exerts a complex and tissue-specific influence on S content in C. moschata seedlings.

Total Se, inorganic Se, and organic Se contents in leaves and roots were also determined. As shown in Fig. 3d, e, all three Se fractions increased gradually and significantly with rising selenite concentration. Se accumulation in roots reached approximately 337.84, 1,010.84, 1,261.25, and 1,572.05 mg·kg–1 DW under Se2, Se10, Se20, and Se40, respectively. Corresponding Se levels in leaves were approximately 28.01, 82.66, 108.55, and 151.11 mg·kg–1 DW. Furthermore, the majority of accumulated Se was in organic forms, ranging from 61.40% to 67.44% in shoots and 70.06% to 72.36% in roots across the selenite concentrations tested (2–40 μM). These results indicate that C. moschata readily takes up selenite and converts it to organic Se forms.

RNA-seq analysis and identification of DEGs

-

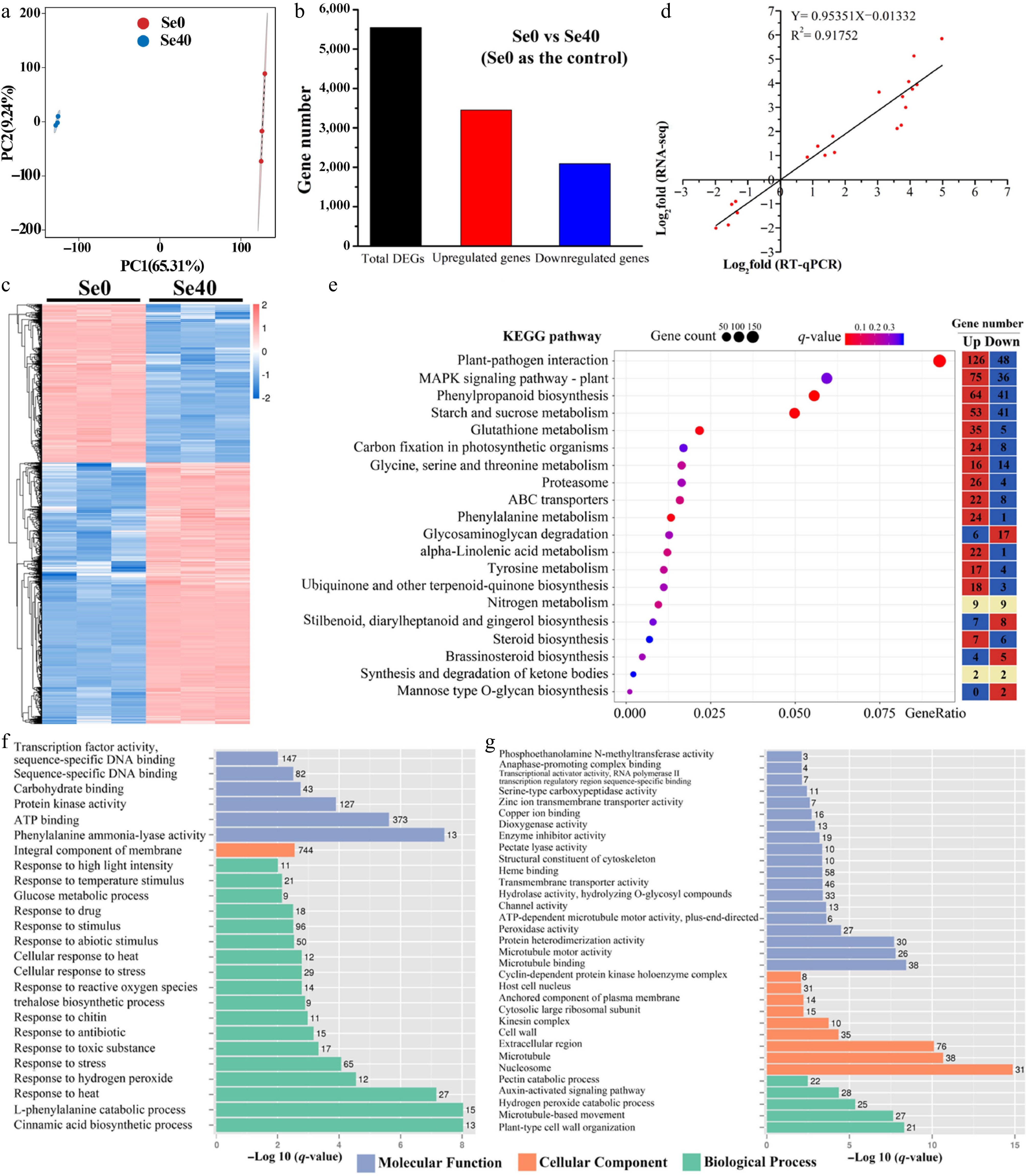

To investigate the transcriptomic responses to selenite stress in WCO39, six cDNA libraries were prepared from three control (Se0-1, Se0-2, Se0-3) and three 40 μM selenite-treated (Se40-1, Se40-2, Se40-3) root samples. Sequencing and mapping results are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. An average of 43,611,804 clean reads per sample was obtained, with Q30 percentages ≥ 93.97%. Approximately 80.90% of clean reads mapped to the C. moschata reference genome, with > 78.40% uniquely mapped and < 2.41% multiply mapped. Pearson's correlation coefficients (R) between biological replicates exceeded 0.99 (Supplementary Fig. S2), and principal component analysis (PCA) revealed a clear separation between control and selenite treatment samples (Fig. 4a), confirming the reliability of the replicates in this study.

Figure 4.

Analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified in Se0 vs Se40 comparison. (a) Principal component analysis (PCA) analysis. (b) Number of DEGs in Se0 vs Se40. (c) Heatmap showing the hierarchical clustering of DEGs. Both the rows and the columns are scaled by normalization. (d) Correlation analysis between the RNA-seq and qRT-PCR results. The abscissa (X-Ais) and ordinate (Y-Ais) quantitatively represent the Log2-transformed fold-change values (Se40/Se0) derived from RNA-seq and qRT-PCR analyses, respectively. (e) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs. The topmost enriched 20 KEGG pathways with the lowest q-values are shown. Gene ratio refers to the ratio of the DEGs to the total number of annotated genes in each pathway. The heatmap on the right side shows the number of upregulated and downregulated genes in each KEGG pathway. (f), (g) GO enrichment analysis of the upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively. The topmost enriched GO terms under the three main GO categories are displayed.

Comparing Se0 vs Se40 (with Se0 as control), the study identified 5,545 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), comprising 3,453 upregulated and 2,092 downregulated genes (Fig. 4b; Supplementary Fig. S3). This predominance of upregulated genes suggests that selenite-responsive genes were largely induced during the early stage of treatment. Hierarchical clustering of all DEGs showed tight grouping of the biological replicates within each treatment group (Fig. 4c). To validate the RNA-seq results, 20 DEGs with high expression levels in at least one group (FPKM > 10), including 15 upregulated and five downregulated genes, were selected for analysis by qRT-PCR. The qRT-PCR results strongly correlated with the RPKM values (R2 = 0.92) (Fig. 4d), confirming the reliability of the identified DEGs.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs revealed their functional roles under selenite stress. The top 20 enriched pathways (smallest q-value) were shown in Fig. 4e. Notably, selenite-induced genes outnumbered inhibited genes in most enriched pathways (14/20), suggesting widespread pathway activation in response to selenite in WC40. These pathways included two related to plant hormone biosynthesis ('alpha-Linolenic acid metabolism' and 'Brassinosteroid biosynthesis'), four associated with stress response and defense ('Starch and sucrose metabolism', 'Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis', 'Glutathione metabolism', and 'MAPK signaling pathway-plant'), and one involved in membrane transport ('ABC transporters').

To further understand the functions of upregulated and downregulated genes, GO enrichment analysis was conducted separately on the 3,453 upregulated genes (Fig. 4f) and 2,092 downregulated genes (Fig. 4g). For the upregulated genes, 18, one and six significantly enriched terms were obtained in biological processes, cellular component and molecular function categories, respectively (Fig. 4f). Within BP, 15 terms were stress-related, including 'response to stress', 'response to toxic substance', 'response to reactive oxygen species', 'cellular response to stress', 'response to abiotic stimulus', and so on. The only enriched CC term was 'integral component of membrane' (744 genes). In MF, 'phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activity' (linked to phenylpropanoid metabolism) was the most enriched term. For the downregulated genes, significant enrichment was found for five BP, nine CC, and 19 MF terms (Fig. 4g). The most enriched BP term was 'plant-type cell wall organization'. One BP term related to ROS ('hydrogen peroxide catabolic process') was also enriched. In CC, downregulated genes were primarily associated with the cell nucleus ('nucleosome' and 'host cell nucleus'). Within MF, 'microtubule binding' was the most enriched term. These results suggest the complexity of selenite response in C. moschata.

Analysis of DEGs annotated to putative transporters

-

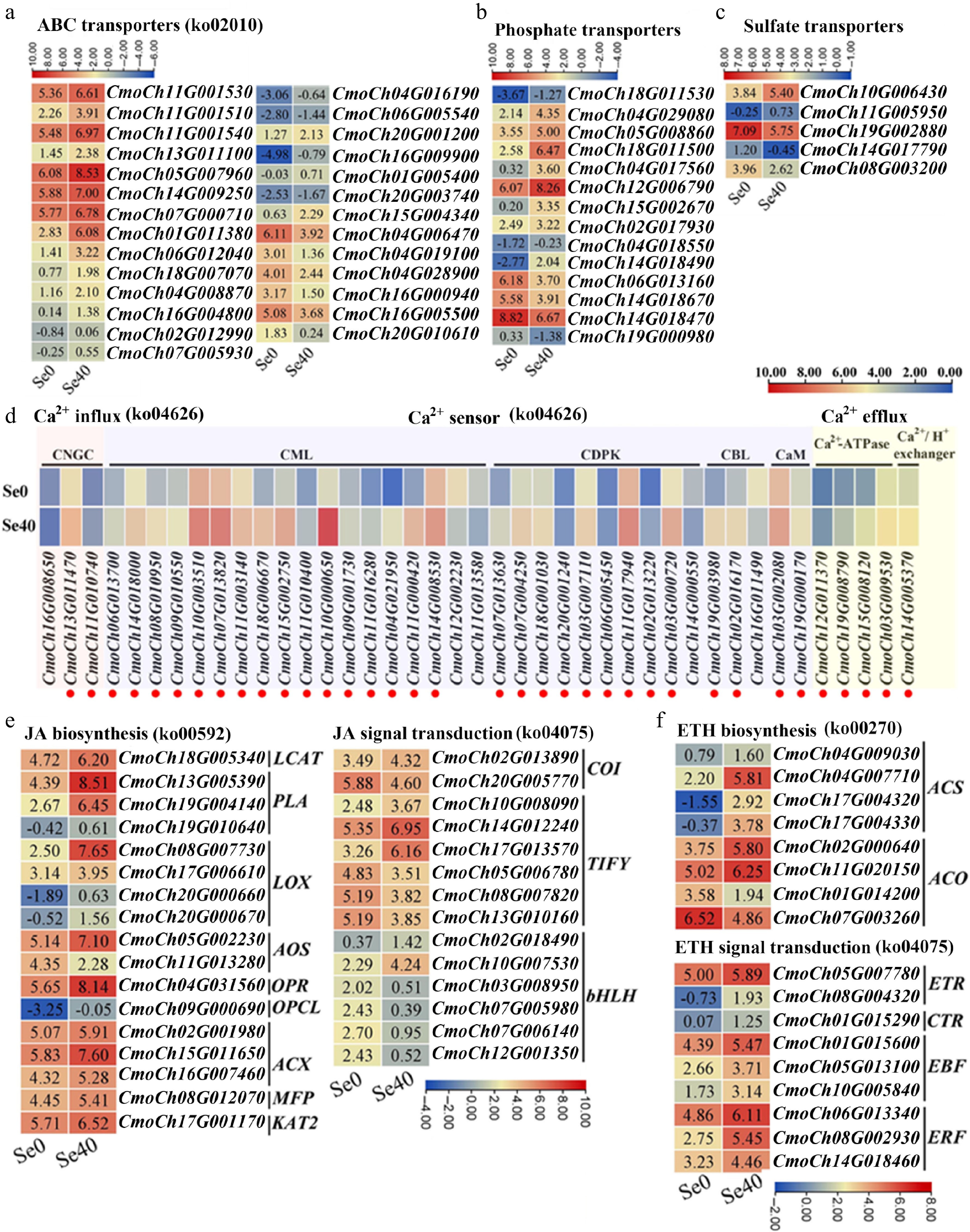

Based on NR database annotations, 162 DEGs were annotated as transporters and classified into 40 functional categories (Supplementary Fig. S4). ABC transporters constituted the largest proportion (about 17%) (Supplementary Fig. S4), with the majority (21/27) being upregulated by selenite treatment. Notably, seven ABC transporters, including CmoCh11G001530, CmoCh11G001510, CmoCh11G001540, CmoCh05G007960, CmoCh14G009250, CmoCh07G000710 and CmoCh01G011380, exhibited both high expression (FPKM > 10) and significant upregulation (> 2-fold) under selenite stress (Fig. 5a; Supplementary Table S3). PHTs, which are reported to be involved in the uptake of selenite in plant roots[30], represented the second largest category (about 9%) (Supplementary Fig. S4), with most (10/14) showing upregulation under selenite treatment (Fig. 5b; Supplementary Table S3). Among them, CmoCh12G006790 showed the highest expression level under selenite treatment, with a 4.56-fold increase compared to the control, and CmoCh18G011500 exhibited the highest fold-change upregulation (14.79-fold) with high expression under selenite treatment. Additionally, two PHTs (CmoCh14G018470 and CmoCh06G013160) were downregulated > 4-fold by selenite treatment.

Figure 5.

Heatmaps showing DEGs involved in several important pathways. (a)–(c) ABC transporters, phosphate transporters, and sulfate transporters, respectively. Upregulated genes are marked in red. (d) Ca2+ influx, sensors, and efflux. CNGC: cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel; CaM, calmodulin; CML: CaM-like protein; CBL: calcineurin B-like protein; CDPK: calcium-dependent protein kinase. (e), (f) DEGs related to the biosynthesis and signal transduction of JA and ETH, respectively. LCAT: lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase; PLA: phospholipas; LOX: lipoxygenase; AOS: allene oxide synthase; OPR: oxophytodienoate reductase; ACX: acyl-coenzyme A oxidase; MFP: multifunctional protein; OPCL: 4-coumarate—CoA ligase; KAT: ketoacyl-CoA thiolase; COI: coronatine-insensitive protein; bHLH: basic helix-loop-helix protein; ACS: 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase; ACO: 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase; ETR: ethylene receptor; CTR: constitutive triple response protein; EBF: EIN3-binding F-box protein; ERF: ethylene-responsive transcription factor. Some pathways have been listed with their corresponding KEGG pathway ID numbers behind them. The Log2 (FPKM) for each gene in different samples is shown in the appropriate grid.

The DEGs encoding sulfate transporters (SULTRs) were also examined due to their implication in selenate transport[30]. Five differentially expressed SULTRs were identified, three of which (CmoCh19G002880, CmoCh14G017790, and CmoCh08G003200) were suppressed by selenite treatment (Fig. 5c; Supplementary Table S3). Notably, CmoCh10G006430 was significantly upregulated (2.95-fold) and highly expressed under selenite treatment.

Analysis of DEGs related to Ca2+ influx, sensor, and efflux

-

As shown in Fig. 5d and Supplementary Table S4, three DEGs were annotated as encoding cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel (CNGC), and two of them showed significant upregulation under selenite stress. Additionally, selenite treatment resulted in differential expression of two calmodulin genes (CaMs), 18 CaM-like protein genes (CMLs), ten calcium-dependent protein kinase genes (CDPKs), and three calcineurin B-like protein genes (CBLs). Among these, the majority (both CaMs, 16 of 18 CMLs, nine of ten CDPKs, and two of three CBLs) exhibited significantly higher expression compared to the control (Fig. 5d; Supplementary Table S4). Notably, four CMLs (CmoCh10G000650, CmoCh04G021950, CmoCh11G00042, CmoCh11G000420) and one CBL (CmoCh19G003980) were upregulated > 10-fold by selenite. Furthermore, the CDPK-encoding gene CmoCh03G000720 displayed about 3.2-fold upregulation (Fig. 5d; Supplementary Table S4). Four DEGs annotated as Ca2+-ATPases and one as a Ca2+/H+ exchanger were also identified, all of which responded positively to selenite treatment (Fig. 5d; Supplementary Table S4). Collectively, these results suggest that selenite activates multiple components of calcium signaling pathways in WCO39 seedlings.

Analysis of DEGs related to biosynthesis and signal transduction of jasmonate and ethylene

-

Seventeen DEGs associated with jasmonate (JA) biosynthesis and 14 DEGs involved in JA signal transduction were identified (Fig. 5e; Supplementary Table S5). Sixteen of the 17 putative JA biosynthesis genes were upregulated by selenite treatment. These included genes encoding: LCAT (CmoCh18G005340), PLA (CmoCh13G005390, CmoCh19G004140, CmoCh19G010640), LOX (CmoCh08G007730, CmoCh17G006610, CmoCh20G000660, CmoCh20G000670), AOS (CmoCh05G002230), OPR (CmoCh04G031560), OPCL (CmoCh09G000690), ACX (CmoCh02G001980, CmoCh15G011650, CmoCh16G007460), MFP (CmoCh08G012070), and KAT (CmoCh17G001170). For the 14 putative JA signal transduction genes, only six were upregulated. These comprised one COI1 (CmoCh02G013890), three TIFYs (CmoCh10G008090, CmoCh14G012240, CmoCh17G013570), and two bHLHs (CmoCh02G018490, CmoCh10G007530), suggesting complex regulation of JA biosynthesis and signaling pathways by selenite treatment.

Additionally, eight DEGs involved in ethylene (ETH) biosynthesis were identified. Most (6/8) were significantly upregulated by selenite treatment, particularly CmoCh04G007710, CmoCh17G004320, CmoCh17G004330, and CmoCh02G000640, exhibiting fold-change increases of about 12.13, 22.10, 17.81, and 4.14, respectively (Fig. 5f; Supplementary Table S5). Nine DEGs involved in ETH signal transduction, encompassing two ETRs, one CTR1-like, three EBFs, and three ERFs, were also identified. All were significantly upregulated in response to selenite treatment (Fig. 5f; Supplementary Table S5), indicating activation of both ETH biosynthesis and signaling pathways in WCO39 seedlings by selenite treatment.

Analysis of DEGs related to Se assimilation and the MAPK signaling pathway

-

Nine DEGs involved in Se assimilation were identified (Table 1; Supplementary Table S6). Seven were significantly upregulated, including genes encoding APS (CmoCh14G017980), APK (CmoCh16G003340), APR (CmoCh06G017430), SO (CmoCh15G000800), GR (CmoCh14G019350), and CS (CmoCh10G011250, CmoCh10G011260). Notably, CmoCh10G011250 showed both the highest upregulation (about 3.08-fold) and the highest expression abundance under selenite treatment, suggesting its importance for Se assimilation in WCO39 roots.

Table 1. List of genes related to selenium assimilation and MAPK cascade.

Gene ID Gene description Gene synonym Se0_FPKM Se40_FPKM log2 (fold change) CmoCh01G020230 ATP sulfurylase 2 CmoAPS 2.86 0.85 −1.47 CmoCh14G017980 ATP sulfurylase 1 2.80 4.96 1.09 CmoCh16G003340 Adenylyl-sulfate kinase 3 CmoAPK 2.13 5.31 1.58 CmoCh06G017430 5'-adenylylsulfate reductase 5 CmoAPR 22.22 40.04 1.12 CmoCh15G000800 Sulfite oxidase CmoSO 10.46 25.85 1.58 CmoCh11G008630 Sulfite reductase CmoSiR 38.88 14.97 –1.10 CmoCh10G011250 Cysteine synthase CmoCS 37.43 115.32 1.90 CmoCh10G011260 Cysteine synthase 1.69 3.08 1.14 CmoCh14G019350 Glutathione reductase CmoGR 17.50 44.68 1.63 CmoCh01G005840 Mitogen-activated protein kinase 3 CmoMAPK 92.46 207.21 1.44 CmoCh04G000390 Mitogen-activated protein kinase 9 21.45 38.13 1.10 CmoCh18G000490 Mitogen-activated protein kinase 9 3.04 6.83 1.44 CmoCh13G010340 Mitogen-activated protein kinase 9 0.38 1.98 2.67 CmoCh12G013530 Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 CmoMAPKK 13.07 25.41 1.23 CmoCh07G007160 Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 17 CmoMAPKKK 4.45 12.19 1.73 CmoCh19G009390 Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 17 0.51 1.21 1.51 CmoCh01G011670 Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 18 19.82 4.70 –1.80 CmoCh02G001800 Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 18 0.20 1.29 2.87 CmoCh15G007330 Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1 8.21 19.54 1.52 CmoCh17G002450 Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7.65 1.68 –1.91 The false discovery rate (FDR) values for all genes are less than 0.001. Additionally, 11 DEGs associated with the MAPK cascade were regulated by selenite treatment (Table 1; Supplementary Table S6). These included four CmoMAPKs (CmoCh01G005840, CmoCh04G000390, CmoCh18G000490, CmoCh13G010340), one CmoMAPKK (CmoCh12G013530), and six CmoMAPKKKs (CmoCh07G007160, CmoCh19G009390, CmoCh01G011670, CmoCh02G001800, CmoCh15G007330, CmoCh17G002450). All four CmoMAPKs were upregulated, especially CmoCh01G005840, which exhibited the highest fold-change increase (about 2.24-fold) and the highest expression abundance under selenite treatment. Expression of the CmoMAPKK was increased about 2-fold by selenite treatment. Most CmoMAPKKKs (4/6) were significantly upregulated, particularly CmoCh07G007160 and CmoCh15G007330, with fold-change increases of about 2.73 and 2.38, respectively.

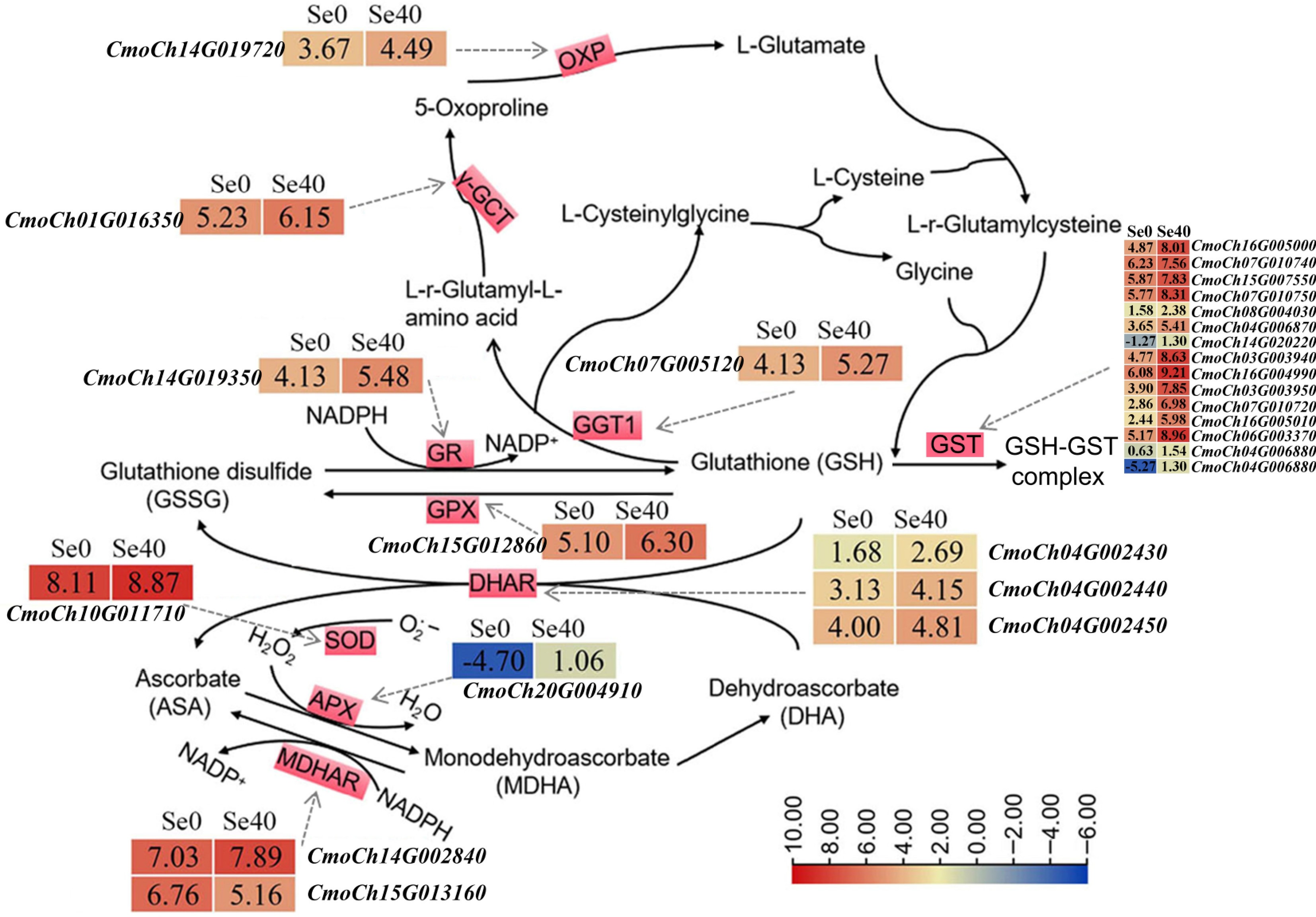

Analysis of DEGs related to the GSH cycle, ASA-GSH cycle

-

Three DEGs (CmoCh07G005120, CmoCh01G016350, and CmoCh14G019720) involved in the glutathione (GSH) cycle were significantly upregulated by selenite treatment (Fig. 6; Supplementary Table S7). Nine genes associated with the ascorbate (ASA)-GSH cycle also responded to selenite treatment. Eight of these (excluding CmoCh15G0113160) were significantly upregulated, including genes encoding: GR (CmoCh14G019350), GPX (CmoCh15G012860), MDHAR (CmoCh14G002840), APX (CmoCh20G004910), Cu/Zn-SOD (CmoCh10G011710) and DHAR (CmoCh04G002430, CmoCh04G002440, and CmoCh04G002450) (Fig. 6; Supplementary Table S7). Additionally, 14 glutathione S-transferase (GST)-encoding DEGs were significantly upregulated by selenite treatment. Eight of them exhibited particularly strong induction, including CmoCh16G005000 (8.80-fold), CmoCh07G010750 (5.80-fold), CmoCh03G003940 (14.58-fold), CmoCh16G004990 (8.80-fold), CmoCh03G003950 (15.46-fold), CmoCh07G010720 (17.32-fold), CmoCh16G005010 (11.59-fold), and CmoCh06G003370 (13.90-fold). These results revealed the activation of both glutathione and ASA-GSH cycles in C. moschata seedlings under 40 μM selenite treatment.

Figure 6.

DEGs related to GSH and ASA-GSH cycles. The solid arrows indicate the substrates and products of the metabolic reaction. The dotted arrows represent the enzymes encoded by the corresponding DEGs identified in Se0 vs Se40 (Se0 as the control). The heatmaps represent the corresponding expression levels of DEGs, and the Log2 (FPKM) for each gene is shown in the appropriate grid.

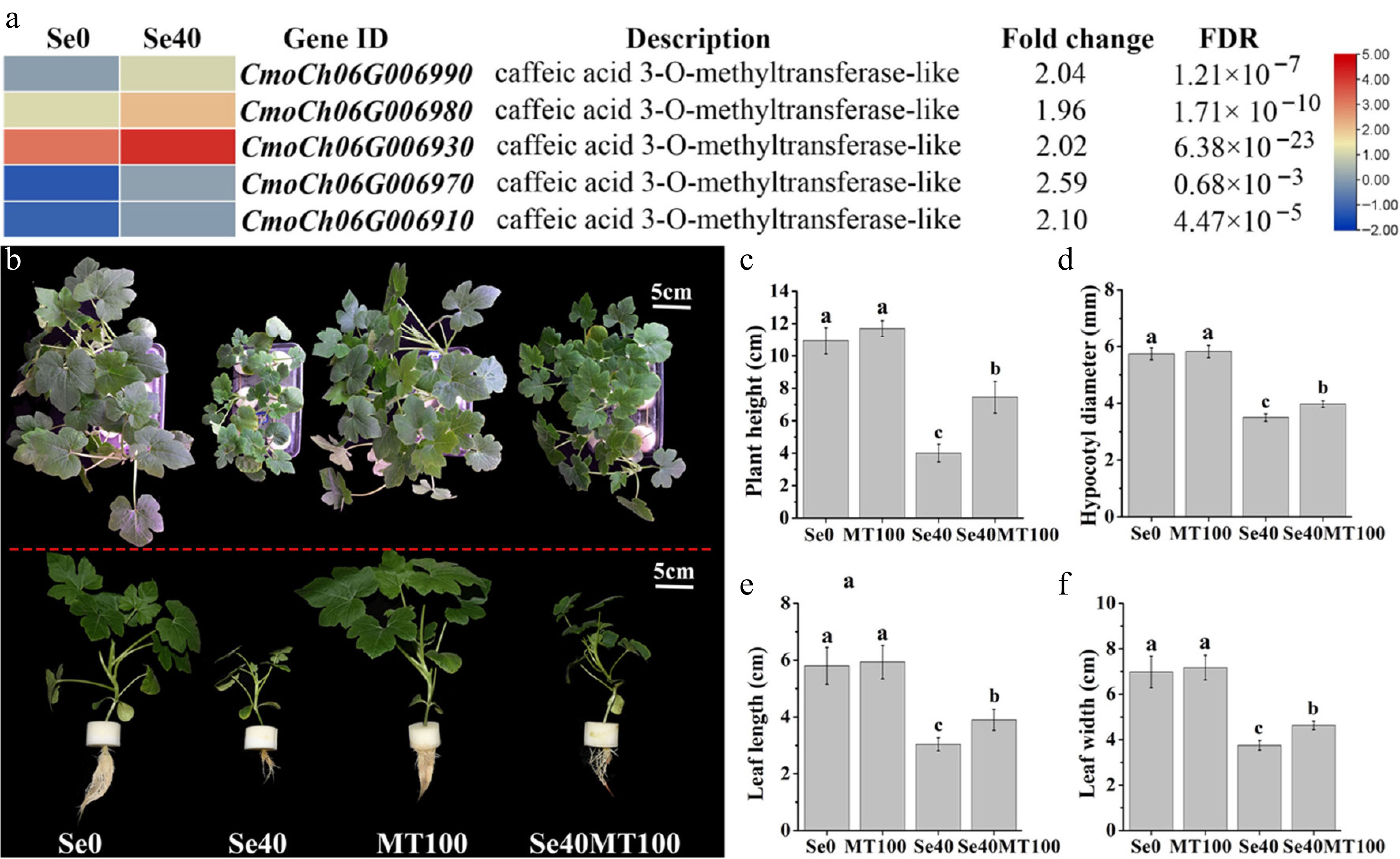

Analysis of DEGs related to melatonin biosynthesis and the influence of exogenous melatonin treatment on selenite stress

-

Caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase (COMT) catalyzes the final step of MT biosynthesis in Arabidopsis, converting N-acetylserotonin to MT[31]. Five COMT-encoding DEGs significantly upregulated by selenite treatment were identified (Fig. 7a; Supplementary Table S8), meaning selenite activates COMT expression in C. moschata seedlings.

Figure 7.

Analysis of DEGs involved in melatonin biosynthesis and the influence of exogenous melatonin treatment on selenite stress. (a) Heatmap showing DEGs annotated to encoding caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase. The Log2 (FPKM) for each gene is used to generate this heatmap. (b) Phenotypes of WCO39 seedlings under different treatments. (c)–(f) Statistical analysis of different growth indicators. Se0 represents normal seedlings; Se40 represents seedlings irrigated with 40 µM selenite; MT100 represents seedlings grown in normal culture with foliar application of 100 µM melatonin; Se40MT100 represents seedlings treated with 40 µM selenite and also sprayed with 100 µM melatonin. The data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). Different small letters on the bars stand for significant differences at p < 0.05 according to Duncan's multiple scope tests.

Given melatonin's established roles in abiotic stress resistance[16], the effect on selenite-stressed seedlings was examined. The MT-treated group (Se40MT100) showed significantly improved growth versus selenite-only controls (Se40) (Fig. 7b–f). This mitigation of selenite toxicity was evident by increased plant height, hypocotyl diameter, and leaf area (Fig. 7c–f), indicating melatonin's protective role against selenite stress in C. moschata seedlings.

-

In plants, Se has been reported to be beneficial for growth and biomass accumulation at low concentrations, but toxic at higher levels, leading to growth retardation, reduced biomass, chlorosis, and ultimately plant death[5,7,11]. To date, the effects of Se on pumpkin growth have not been reported. In this study, C. moschata seedlings were treated with different concentrations of selenite, a dominant bioavailable form of Se in soil[17]. Results indicated that 2 μM selenite had only a slight effect on C. moschata seedling growth. However, moderate concentrations (10–20 μM) significantly retarded growth and increased S content in shoots, consistent with previous studies in cucumber[32] and Arabidopsis[33]. High selenite concentrations impaired growth and physiology in C. moschata: 40 µM significantly inhibited growth and reduced chlorophyll content, while 80 µM induced severe phytotoxicity, characterized by leaf chlorosis and root necrosis. Similarly, cucumber exhibited significant phytotoxic effects at selenite concentrations exceeding 20 µM[32]. These results show a dose-dependent toxic effect on C. moschata under selenite treatment and underscore the need to identify optimal Se concentrations for cucurbit crops during biofortification.

Selenite absorbed by roots is rapidly converted to organic forms within roots, with limited translocation to shoots[34]. Se accumulation occurs predominantly in organic forms, as observed in rice[35]. Similarly, the results showed that organic Se levels in both leaves and roots were significantly higher than inorganic Se levels across selenite treatments, with the majority of Se accumulating in roots. Furthermore, Se content in both shoots and roots of C. moschata seedlings exhibited a dose-dependent response to selenite. Transportation of selenite across the root plasma membrane is mainly mediated by PHTs[17]. In rice, overexpression of OsPHT2 increased selenite uptake, while mutants exhibited decreased uptake[36], confirming the importance of PHTs for selenite absorption in plants. In this study, several PHTs were highly upregulated in response to selenite treatment, likely facilitating selenite uptake in C. moschata. Inostroza-Blancheteau et al.[37] and Cao et al.[38] reported that SULTRs can be activated by selenite in plant roots. In this study, two significantly upregulated SULTRs belonging to the SULTR3;5 subfamily in C. moschata were identified. According to previous studies, SULTR3;5 colocalizes with SULTR2;1 in plant root xylem[39], and SULTR2;1 facilitates sulfate and selenate translocation from roots to shoots[17]. This suggests that high expression of SULTR3;5 in C. moschata roots may contribute to selenite translocation to shoots. Furthermore, these findings support a role for ABC transporters in Se accumulation[12,40], as numerous ABC transporter genes were differentially expressed, with the majority significantly upregulated by selenite treatment.

Due to the high chemical similarity between Se and S, Se typically enters the S metabolic pathway in plants, forming various Se compounds[17]. Sulfite oxidase (SO) catalyzes the oxidation of sulfite to sulfate in plants[41]. It was found that the SO gene CmoCh15G000800 was significantly upregulated by selenite treatment, which should contribute to the oxidation of selenite in C. moschata roots. This hypothesis is further supported by the significant upregulation of genes encoding APS, APK, and APR, which are involved in selenate reduction to selenite in plants[17]. Several studies report that selenite can be non-enzymatically reduced to selenide by GSH in plants, and glutathione reductase (GR) plays a key role in this pathway[17]. This study identified one GR-encoding gene, CmoCh14G019350, whose expression was greatly upregulated by selenite treatment in C. moschata. CS exhibits a higher affinity for selenide than sulfide and catalyzes its conversion to SeCys[7]. Two CS genes were significantly upregulated, implying their importance for SeCys synthesis in C. moschata.

Calcium (Ca2+) is a ubiquitous second messenger that plays critical roles in plant responses to abiotic stresses[42]. The results revealed that selenite stress significantly upregulated CNGC-encoding genes. CNGCs act as 'on' components of Ca2+ signaling, mediating stress-induced Ca2+ influx[42], suggesting that selenite induces Ca2+ uptake and activates Ca2+ signaling in C. moschata. As expected, numerous genes encoding calcium sensors, including CaMs, CMLs, CDPKs, and CBLs[43], showed altered expression under selenite treatment, with most being upregulated. However, Rao et al.[12] observed the downregulation of CDPKs under selenate treatment in Cardamine violifolia. These contrasting results may stem from differences in plant species, Se forms (selenite vs selenate), concentration, or treatment duration. It is reported that Ca2+ signaling induces respiratory burst oxidase homolog (RBOH)-mediated ROS production, which further promotes Ca2+ influx by activating calcium-permeable ion channels[44]. In this study, two upregulated RBOHs were identified, both of which exhibited significantly higher expression under both control and selenite treatment conditions, implying their activation by Ca2+ signaling during selenite exposure in C. moschata. This observation aligns with reports that selenium acts as a pro-oxidant, generating ROS at high concentrations in plants[7]. Ca2+-ATPase and Ca2+/H+ exchangers are mainly membrane proteins responsible for Ca2+ efflux to maintain cellular Ca2+ homeostasis under abiotic stresses[42,45]. The study found three Ca2+-ATPase genes and two Ca2+/H+ exchanger genes significantly upregulated in selenite-treated C. moschata. This enhanced efflux activity suggests excessive Ca2+ accumulation occurs under selenite stress. Collectively, these DEGs related to Ca2+ influx, sensing, and efflux reflected that Ca2+ signaling should be involved in plant response to selenite treatment.

Se toxicity primarily stems from ROS-mediated oxidative stress in plants[7]. The results revealed excessive O2·− accumulation in leaves of WCO39 seedlings treated with high selenite doses (> 20 μM). GSH serves as a crucial non-enzymatic antioxidant for ROS detoxification and redox signaling[46]. Elevated GSH levels in Se-tolerant plants and their depletion-linked ROS accumulation[15] underscore GSH's importance in Se stress adaptation. GGT, GCT, and OXP enzymes are involved in GSH degradation in plants[47]. Thus, significantly elevated expressions of GGT, GCT, and OXP genes in response to selenite imply enhanced GSH metabolism under selenite stress in C. moschata. The ascorbate-glutathione (AsA-GSH) pathway has been well documented in ROS scavenging[48]. Upregulation of GR, GPX, DHAR, APX, and MDHAR genes under selenite treatment indicates that the AsA-GSH cycle should contribute to protecting cells from oxidative damage under selenite stress in C. moschata. Notably, all 14 GST-encoding DEGs responded positively to selenite. Similar upregulation of GSTs was reported in tea roots under selenite treatment[40]. Since GSTs catalyze GSH conjugation to electrophilic substrates, mitigating oxidative burst[49], GST-mediated metabolism likely contributes to the survival of C. moschata from high concentration selenite stress.

The MAPK cascade—comprising MAPKKK, MAPKK, and MAPK components—is a conserved signaling pathway regulating plant adaptation to environmental stresses, and it can be activated by abiotic stress-induced Ca2+ and ROS signals[50,51]. In Arabidopsis, MAPKs promote ETH biosynthesis by phosphorylating ACS (the rate-limiting enzyme of ETH biosynthesis) and upregulating ACS expression[52,53]. Suppression of MAPKs resulted in decreased expression of JA biosynthesis and signaling genes[54,55]. Hoewyk et al.[33] reported reduced Se tolerance in ETH/JA-response-deficient Arabidopsis mutants. While Se regulates ROS-mediated MAPK pathways in mammals[56], the relationship between Se and the MAPK cascade in plants remains poorly characterized. Here, selenite treatment significantly elevated expressions of both MAPK cascade genes and ETH/JA biosynthesis/signaling genes, suggesting MAPK cascade-mediated regulation of ETH and JA pathways contributes to selenite toxicity responses in C. moschata.

Melatonin (MT) alleviates ROS-mediated oxidative stress in plants[57]. Several studies reveal the relationships between Se stress and MT. For example, Se exposure induces MT synthesis-related genes in tomato[58]. Exogenous MT enhances grape growth under Se stress[14]. These results revealed that selenite treatment significantly upregulated multiple COMTs in C. moschata. The enzymes encoded by COMTs catalyze the conversion of N-acetylserotonin to MT, a pivotal step in MT biosynthesis[31]. Exogenous MT application alleviated selenite-induced growth inhibition in C. moschata seedlings, suggesting that COMT-mediated MT synthesis contributes to C. moschata's selenite stress response.

-

The narrow threshold between Se bioavailability and phytotoxicity complicates agricultural applications. Understanding Se effects on Cucurbita moschata seedlings is essential, as this species serves both as a health food and a rootstock for other cucurbits. Treatment with different selenite concentrations revealed that selenite induced dose-dependent Se accumulation in both C. moschata shoots and roots. It was also found that high selenite concentrations (> 40 μM) induced severe O2·− accumulation, growth arrest, and visible toxicity symptoms (leaf chlorosis, root necrosis) during C. moschata seedling growth. Notably, transcriptome analysis indicated that 40 μM selenite could induce expressions of several MT biosynthesis genes, and exogenous MT application alleviated growth inhibition under selenite stress, demonstrating the role of MT in selenite stress amelioration. Besides, many genes related to Ca2+ signaling, ETH and JA signaling, antioxidant defense systems, MAPK cascades, transporters related to selenite absorption, and selenite assimilation genes were activated by selenite treatment, suggesting their involvement in selenite response in C. moschata seedlings. Collectively, these findings advance the understanding of selenite response mechanisms in cucurbits, providing genetic targets and molecular insights for breeding Se-enriched pumpkin varieties with enhanced stress resilience.

This research was supported by Henan Provincial Science and Technology Key Project (Grant No. 232102110232), and Henan Provincial Natural Science Foundation General Program (Grant No. 242300421322). The authors express their special gratitude to all the funding sources for the financial assistance.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wang Y, Sun S, Zhu L; data collection: Wang Y, Wang L, Liu W, Wang J; analysis and interpretation of results: Wang Y, Zhang T, Li Y, Mushtaq N; draft manuscript preparation: Wang Y, Mushtaq N, with contributions from Li Y, Zhu L, Yang L. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

RNA-seq data for this study are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) repository, Bioproject: PRJNA1091146.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Henan Zhongwei Chunyu Plant Nutrition Co., Ltd. had no any involvement in the study.

- Supplementary Table S1 Primers used for RT-qPCR in this study.

- Supplementary Table S2 Quality assessment of the 6 sample transcriptome data.

- Supplementary Table S3 Partial list of the differentially expressed transporters in Se0 vs Se40. Se0 and Se40 represents 0 and 40 μM selenite treatment, respectively. FDR and FC represents the false discovery rate (the adjusted p-value) and fold change, respectively.

- Supplementary Table S4 List of the differentially expressed genes involved in Ca2+ influx, sensor and efflux.

- Supplementary Table S5 List of the differentially expressed genes related to the biosynthesis and signal transduction of JA and ETH.

- Supplementary Table S6 List of the differentially expressed genes involved in Selenium assimilation and MAPK signaling pathway.

- Supplementary Table S7 List of the differentially expressed genes involved in glutathione cycle or ascorbate-glutathione cycle.

- Supplementary Table S8 List of the differentially expressed genes involved in melatonin biosynthesis.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Flow chart of WCO39 seedling culture in this study.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Pearson's correlation coefficients (R) between the three biological replicates of each sample.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Se0 vs Se40. Horizontal axis means Log2(fold change) value, and vertical axis means the level of significance with false discovery rate (FDR). |log2 FC (fold change)| ≥ 1 and FDR < 0.01 were used as thresholds for significantly up- or down-regulated genes.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Pie Graph showing the DEGs in Se0 vs Se40 annotated as different transporters in NR database. The proportions of different transporters were presented.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang Y, Wang L, Mushtaq N, Liu W, Zhang T, et al. 2025. Physiological and transcriptomic insights into selenite-induced stress responses in Cucurbita moschata seedlings. Vegetable Research 5: e032 doi: 10.48130/vegres-0025-0026

Physiological and transcriptomic insights into selenite-induced stress responses in Cucurbita moschata seedlings

- Received: 01 May 2025

- Revised: 26 June 2025

- Accepted: 14 July 2025

- Published online: 12 September 2025

Abstract: Selenium (Se)-enriched plants constitute important dietary sources of Se for human nutrition, and selenite is one of the dominant forms of Se available to plants in soil. However, the threshold between beneficial and phytotoxic selenite levels in soil remains narrow, posing challenges for plant growth. This study investigated the effects of selenite concentrations (2–80 μM) on growth parameters and Se accumulation in Cucurbita moschata seedlings. The findings showed significant stress effects under all except 2 μM selenite treatments, and demonstrated a dose-dependent toxic effect and Se accumulation in both shoots and roots. Concentrations exceeding 40 μM not only induced elevated superoxide radical (O2·−) accumulation but also caused significant growth inhibition and visible toxicity symptoms, and these adverse effects were significantly mitigated by exogenous melatonin application, so 40 μM selenite treatment was selected for RNA-seq. Transcriptomic analysis revealed the activation of a suite of defense mechanisms in roots under selenite stress, encompassing Ca2+ signaling, ethylene and jasmonate signaling, antioxidant defense systems, the MAPK cascade, and melatonin synthesis. Furthermore, the study identified candidate genes potentially involved in Se uptake and metabolism, including genes encoding phosphate and sulfate transporters, adenosine triphosphate sulfurylase, adenosine phosphosulfate kinase, adenosine phosphosulfate reductase, sulfite reductase, glutathione reductase, and cysteine synthases. These findings enhance understanding of the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying Se accumulation and tolerance to Se toxicity in C. moschata and provide genetic targets and a theoretical foundation for breeding Se-enriched pumpkin varieties with enhanced stress resilience.

-

Key words:

- Pumpkin /

- Selenite /

- Toxicity /

- Physiology /

- Transcriptome /

- Melatonin