-

The emerging improvements in recent wireless communication technology that have enabled vehicles to communicate with roadway infrastructure, and with each other, are collectively known as connected vehicle (CV) technology[1]. CV technology features low latency, real-time data, high reliability, and high security in a high-mobility environment[1]. It has developed rapidly for its potential to improve the mobility, safety, and environmental impact of traffic systems over the past several years[2−9]. These three challenges, i.e., safety, mobility, and environment, are significant issues faced by modern transportation systems. The impact of these three issues includes significant economic loss, heavy casualties, as well as long-term adverse environmental damage in large urban areas[10].

To tackle these serious problems, urban transportation systems have relied heavily on various proposed urban traffic control systems (UTCSs) over the last few decades[1, 11−16]. Considering the complexity of urban transportation networks and performance dependency on different control types, both the choice and design of proper traffic signal control systems are important. Thus, there is a large body of literature that has investigated developments of the conventional traffic signal control systems, and most of their methods can be categorized into three strategies: fixed-time, actuated, and adaptive control[1, 17].

Within the current practice, fixed-time control systems typically create best-suited timing settings for different times of the day (TOD) determined by the historical traffic data. This method assumes that the traffic demand remains fairly constant during the entire period of a particular timing plan. However, this assumption is seldom valid in realistic scenarios, causing the fixed-time strategy to demonstrate weak control performance[1].

Actuated control systems collect real-time traffic flows from fixed infrastructure-based detectors, e.g., loop detectors, and apply simple logics, including phase calls, green extension, and max out, to change the timing plans. However, these systems have proven to be sub-optimal because the simple logic is based on a set of pre-defined and static parameters[17, 18].

The existing adaptive signal control methods use real-time traffic data to predict future traffic flows and obtain optimal signal timing settings. Subsequent control decisions are based on defined maximal or minimal objective functions[1, 17]. The adaptive signal control (ASC) has been widely applied to urban arterial networks.

Furthermore, to provide smooth traffic flows and reduce the number of stops and delays along an urban corridor or multiple intersections, signal coordination systems have been proposed and implemented by synchronizing traffic signals along a corridor[19].

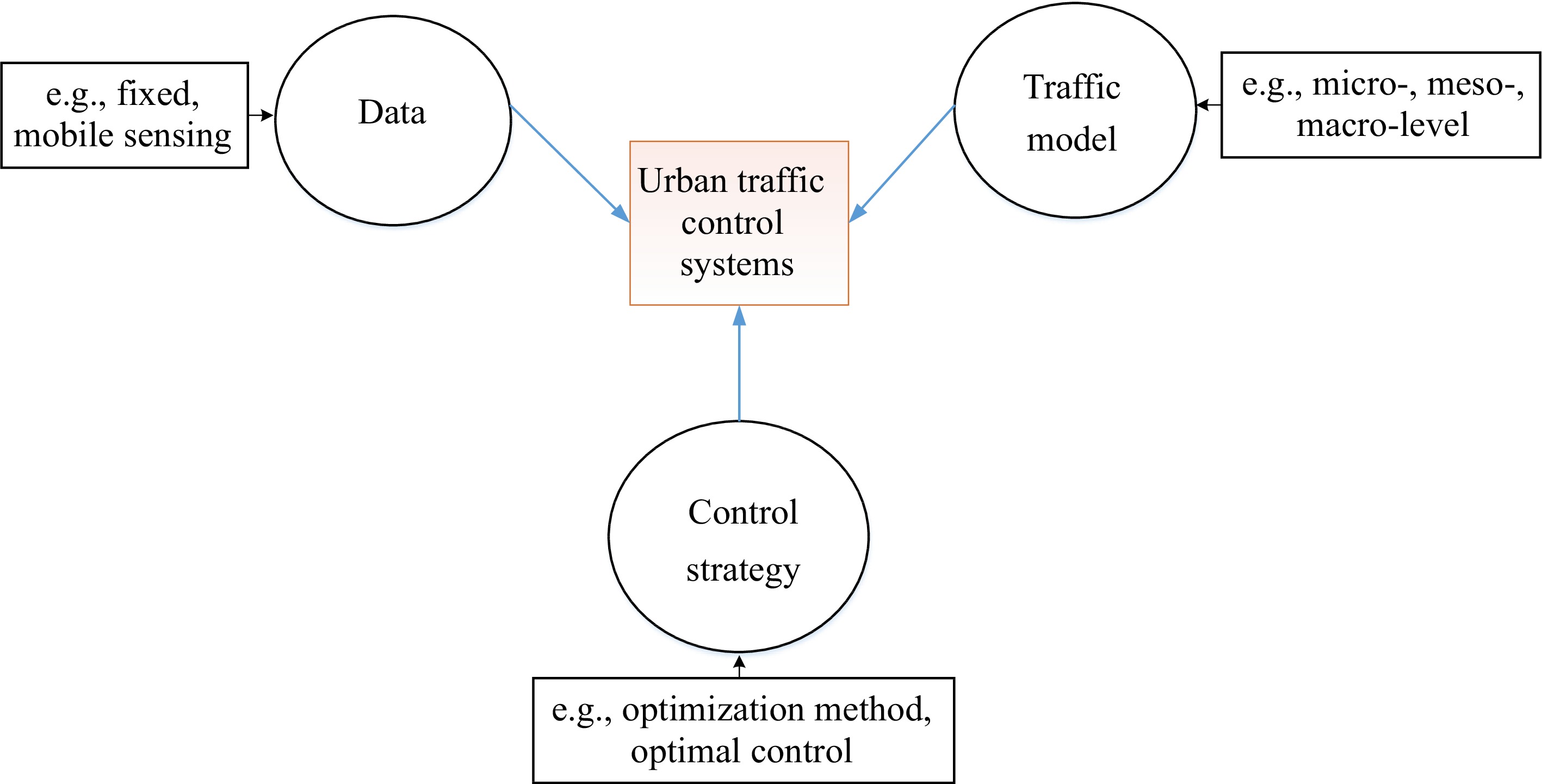

In summary, the existing literature[12−16] examines existing UTCSs that generally consist of three essential components: data, traffic model, and control strategy, graphically represented in Fig. 1 below.

The data describes the spatial and temporal characteristics of the acquired data as input, where usually it includes typical fixed and mobile sensing data. The traffic model depicts the dynamics of traffic on the road links, which include micro-, meso-, and macro-level traffic dynamics. The control strategy utilizes various timing plans to control traffic dynamics, for which standard signal variables include cycle length, split, and offset and the common strategies include optimization-based and optimal control-based methods. Generally, every UTCS includes these three basic components, although not always in some of the early-developed products.

Moreover, since the CV technology features low latency, real-time data, and two-way communication in a high-mobility vehicular environment[1], it further enhances the existing signal control systems[16,17,20−26]. Thus, there are many CV-based adaptive signal control and coordination introduced in the past decade, aimed at further improving the efficiency of UTCSs[16, 17, 20−26]. Also, in general, these CV-based signal control methods can be discussed from the previous three essential components: data, traffic model, and control strategy. Compared with the traditional UTCSs, these CV-based signal control methods feature new data sources and quality, new varying-parametric dynamics, and new optimization and control strategy. The new data source and quality are collected from moving connected vehicles as well as connected infrastructure devices. Next, the micro-level traffic dynamics and corresponding time-varying parameters are more accessible and predictive with the new connected data inputs and the new connectivity technique. Last, for the control strategy, more complex, advanced, and efficient control strategies are presented considering the two-way communication, the rich data inputs, and the predictive dynamics.

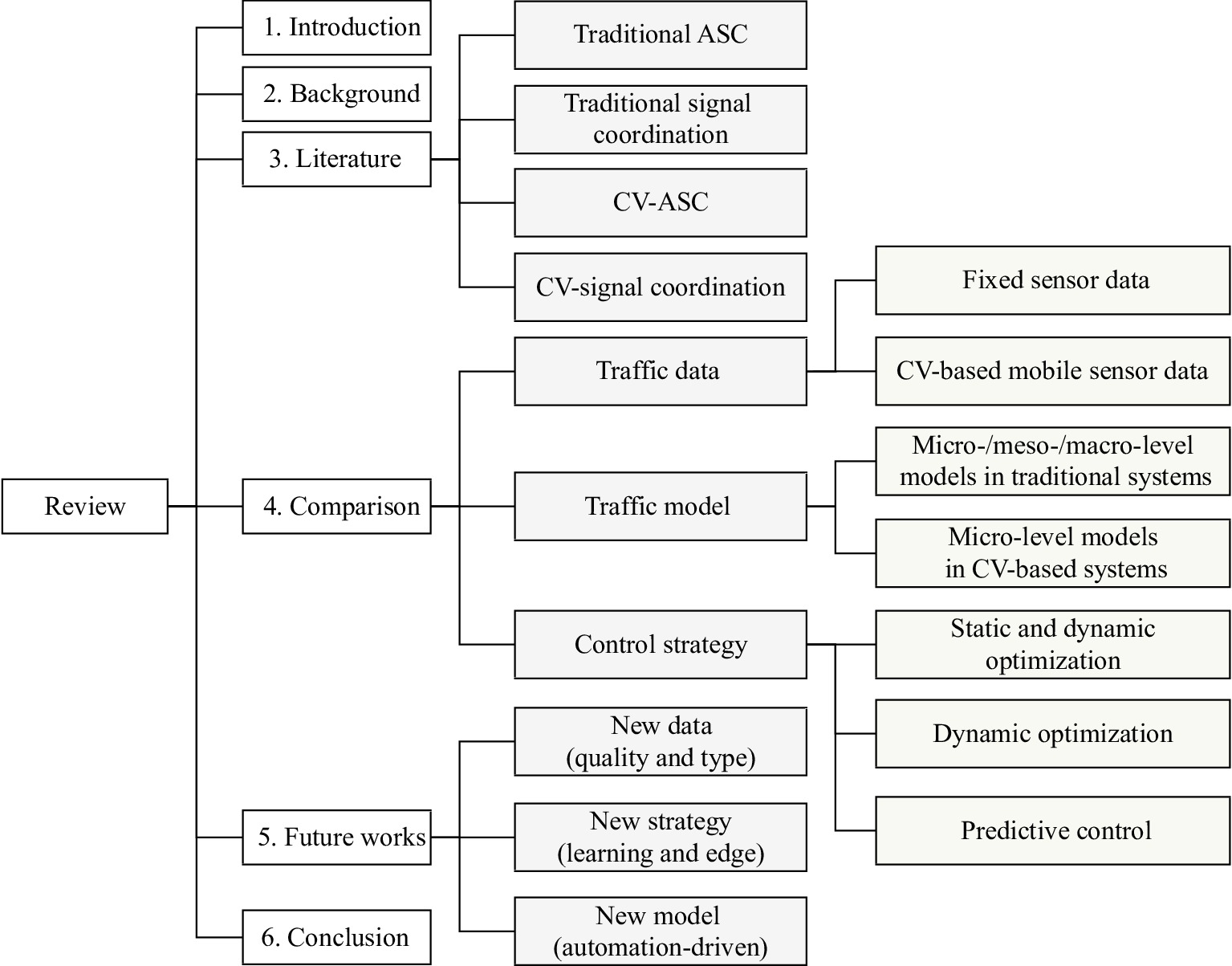

Overall, in this paper, we summarize the typical components and structures of the existing CV-based urban traffic signal control systems and digest several important issues from these three key concepts. These identified issues are explained and discussed in detail. Next, some suggestions for future research directions are provided. Last, the conclusion closes this review. The structure of this review is shown in Fig. 2.

-

Before discussing further details of the three basic UTCS components in the literature review, a brief background of different traffic control technologies is outlined here, thus introducing traditional and widely implemented traffic control systems in current transportation systems, i.e., adaptive signal control and traffic signal coordination. Also, briefly outlined in this section is the emerging CV technology, as well as updates of both enhanced adaptive signal control and coordination in the CV environment.

Connected vehicles

-

CV technology leverages vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) and vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) communications based on dedicated short-range communication (DSRC) or Cellular Vehicle-to-Everything communication (C-V2X)[16,17,20−23], where V2V and V2I communication can be collectively called vehicle-to-everything (V2X) communication. It has been developing rapidly over recent years, improving efficiency, safety, and environmental benefits for traffic systems[2−9].

In addition, CV technology features low latency, real-time data, high reliability, and large security in a fast-mobility condition, which provides a new control dimension in solving the issues of signal control. For example, new real-time CV data, including connectivity indications, signal phase and timings, and vehicle trajectories, all extracted from basic safety messages (BSMs), are providing the potential for significant performance improvements.

Adaptive signal control

-

Conventional traffic signal control systems are classified into three strategies: fixed-time, actuated, and adaptive control[1, 17]. Characteristics of these three signal control systems are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of three conventional signal control systems.

Signal control Data type Traffic prediction Control strategy Fixed-time Historical N/A Pre-defined

timing plansActuated Real-time N/A Simple logics Adaptive Real-time Predictions by

traffic modelsSignal

optimizationsCompared with both fixed-time and actuated signal control systems, the current adaptive signal control system utilizes real-time traffic data to forecast near-future traffic flow conditions. Subsequently, an optimal signal timing setting is obtained to make control decisions based on defined performance-based objective functions. The adaptive traffic control system has been widely applied to urban arterial networks around the world since the 1970s because of its capability to respond to changes in traffic demand.

Different system architectures and algorithms for adaptive traffic control systems have been proposed and implemented during the last several decades. Typical examples of the adaptive signal control systems include SCOOT (Split, Cycle, and Offset Optimization Technique)[27], SCATS (the Sydney Coordinated Adaptive Traffic System)[28], OPAC (Optimization Policies for Adaptive Control)[29], RHODES (Real-time Hierarchical Optimized Distributed Effective System)[30], ACS-lite (Adaptive Control System)[15], and the recent MOTION system[31].

Traffic signal coordination

-

Among various signal control strategies, traffic signal coordination is another significant and widely implemented strategy with enhanced performance measures[19, 32] to improve the mobility of arterial roads. Usually, the coordination system synchronizes traffic signals over the span of a corridor to provide signal progression for the approaching vehicle, thus reducing the number of stops and delays[19]. Since the signal coordination control is recognized to perform better than other control strategies for corridors, a focus on coordination improvement is essential, indeed critical, for current urban transportation systems.

To enhance coordination systems, various methods have been proposed to achieve better performance[19,33,34]. These approaches can be classified into two major types of optimization methodology[19]: (1) Advancement of the quality of progression, like the classical MAXBAND[33], and (2) optimization of a performance index, like the mixed-integer traffic optimization program (MITROP) method[34]. For the former methodology, the objective is to maximize the green bandwidth along a particular arterial roadway. For the latter methodology, different objectives are formulated to minimize performance indices like the number of stops, total delays, average travel times, or a combination thereof.

CV-based adaptive signal control and signal coordination

-

Existing signal control systems are usually based on traffic flow data from fixed location detectors[1, 17, 19]. Due to the rapid advances in the emerging vehicular communication, the CV-based signal control demonstrates significant improvements as compared to existing conventional signal control systems[1, 19, 35, 36]. As a result, many CV-based adaptive signal control methods[1, 35, 37−39] and coordination approaches[19, 32, 40−44], aimed at improving the efficiency of adaptive and coordination systems, have been introduced in the past several years. They can be summarized into several categories: adaptive signal control methods aiming for an isolated signalized intersection, adaptive signal control methods for multiple signalized intersections, and signal coordination for multiple signalized intersections. Typical examples include PAMSCOD (platoon-based arterial multi-modal signal control with online data)[42] and its variants[45], proposed in 2012 and 2014, respectively.

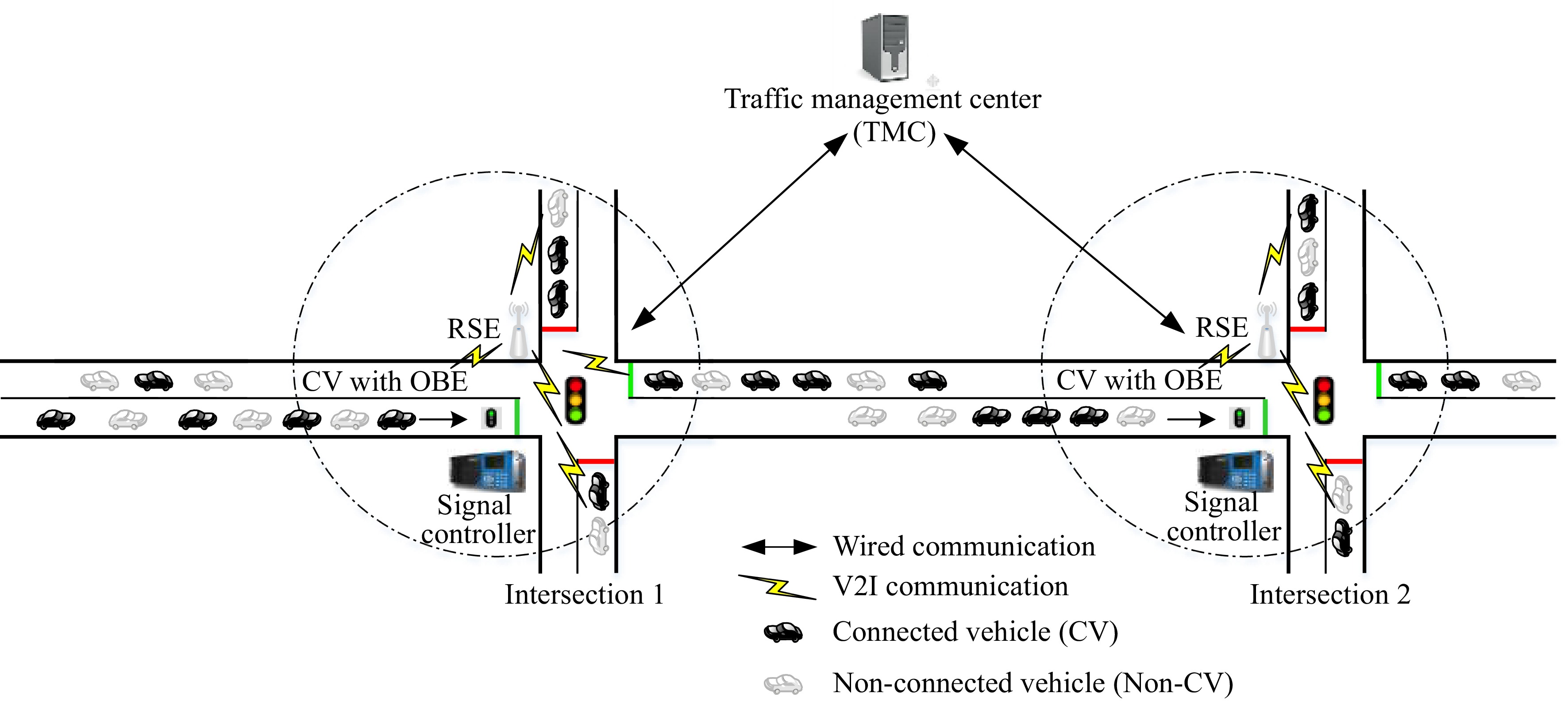

The general definition of a real-time signal control consisting of both adaptive signal control (ASC) and signal coordination in the CV environment is described in Fig. 3. As depicted in Fig. 3, a vehicle platoon approaches a corridor with two signalized intersections and then passes through it. The vehicle platoon might encounter red lights at the signalized intersections and thus experience potential stop delays, thus increasing total travel time significantly. To mitigate stop delays, a CV-based adaptive signal control and coordination framework is deployed as a real-time and, therefore, efficient method.

Figure 3.

A graphical statement of signal control in a mixed CV environment, with an urban road segment with two adjacent signalized intersections.

In such a CV-based signal control framework, including both adaptive signal control and coordination, the critical real-time data transmission between the CVs and the connected roadside infrastructure, as well as the real-time control strategy, improves traffic control performance to be more flexible and efficient[19]. These data generated from the CV technology can be categorized into two fundamental classes[32]. The first class is the real-time CV data, including trajectories, motion data, and signal priority request data. The second class is the real-time infrastructure-based data providing signal phasing and timing (SPaT), the roadway geometry, and current priority status data. These real-time data offer an opportunity to develop a new generation signal control using these real-time CV data. Thus, the full utilization of this highly valuable data could be further exploited to decrease the total travel time in the CV-based signal control framework.

However, existing works on CV-based adaptive signal control and coordination methods still have outstanding issues[17, 19, 43, 46], and, therefore, the potential of CV technology in this domain warrants further study.

-

This section engages in a comprehensive review of existing urban traffic signal control methods, including the following points:

1. Adaptive signal control,

2. Traffic signal coordination,

3. Connected vehicle-based adaptive signal control,

4. Connected vehicle-based traffic signal coordination,

5. Detailed comparisons and limitation analysis. These analysis are conducted for both the existing traditional (non-CV-) and connected vehicle- (CV-) based signal control systems from three fundamental components. These three components are data, traffic model, and control strategy, previously outlined in Fig. 1.

Adaptive signal control

-

The adaptive signal control uses real-time traffic flow data to predict future traffic flow conditions, then generates an optimal signal timing plan. There have been numerous adaptive signal control systems proposed and developed over the past several decades. From the surveys by Stevanovic et al. and Wang et al.[15, 16], there are more than 20 implemented urban adaptive traffic control systems. Ten of the most widely implemented urban traffic control systems (UTCSs) are reviewed and analyzed in detail in the published NCHRP (National Cooperative Highway Research Program) report[15].

In the following discussion, various ASC systems, including SCOOT[27], SCATS[28], are examined in detail to understand their system architectures and algorithms based on performance indices. Then a summary of these systems is given in a table to distinguish them using several different metrics.

The SCATS[28] utilizes a subsystem consisting of several adjacent intersections that is a centralized signal control system. Each near subsystem can be joined together to build one larger subsystem, or divided to build smaller subsystems. Each intersection of one subsystem is controlled by an actuated signal control system. The changes in the cycle, split, and offset are based on heuristic algorithms without traffic models. The heuristic algorithm chooses one timing plan from several pre-defined timing plans to balance the saturation degree on each traffic approach. Only stop-bar detectors are required to record traffic occupancy and volume data when obtaining the saturation data.

SCOOT[27] utilizes a platoon dispersion model and an online optimization method to obtain a proper real-time signal timing setting, which is a hierarchical traffic control system. The delay minimization is implemented to change the current timing plan, in which three parameters are optimized: split, cycle, and offset. Before adjusting the current signal timing plan, the signal timing is used as a fixed timing plan. Upstream and advanced detectors are required to obtain traffic counts, residual queues, and lower bounds of queues, respectively.

Other UTCSs worth mentioning include the following. OPAC[29] is a real-time signal optimization system based on dynamic programming (DP). The deployed DP-based optimization model minimizes delays over a finite future prediction horizon and can eventually be used for a coordinated network[47].

RHODES[30] is based on a hierarchical framework, where it has both an upper level determining the network flow control and a lower level minimizing the intersection level's performance indices. In the lower level, a rolling horizon scheme-based DP is proposed to achieve performance optimizations[48, 49]. Both stop-bar and advanced detectors are required to predict an arrival table for an intersection-level control at the lower level.

ACS-lite[15] focuses on developing lower maintenance and installation costs and a deployable adaptive signal control system. The ACS-lite system is composed of three algorithms: a time-of-day (TOD) planner, a run-time refiner, and a transition controller[47]. The TOD planner changes the current timing plan for different TODs and is responsive to existing traffic conditions. The run-time refiner determines the optimal time to change one timing plan to another. The transition controller determines the optimal transition strategy during the transition period.

Other recent adaptive signal controls include the MOTION system proposed by Brilon & Wietholt in 2013[31], the FITS system introduced by Jin et al. in 2017[50], and the Deep Learning (DL)-based system proposed by Gao et al. in 2017[51]. The MOTION ASC system[31] possesses typical architecture, and the system itself determines optimal timing plans at the global network level and utilizes the actuated signal control at the local intersection level[50]. The FITS system[50] introduced an intelligent control system based on fuzzy logic to optimize timing plan parameters. The DL-based system[51] proposed a deep reinforcement learning method-based system to automatically distill useful flow features from raw traffic condition data to obtain optimal timing plans. Considering the differences with respect to three key components discussed here, these ASC systems can be summarized into three categories: adjusted control, responsive control, advanced adaptive control[14–16, 52]. This classification is shown in Table 2.

Category Adjusted control Responsive control Advanced adaptive control a Data quality: sensor density level (L) Static sensor data L1 & L1.5, less than one sensor up to one sensor per link L2, one sensor per link up to one per lane L3, two sensors per lane a Responsive to demand variations Slow reactive response based on pre-calculated historical traffic flow Prompt reactive response based on changes in regularly disrupted traffic Very rapid proactive response based on short-term predicted movements a Change frequency in control plan (HZ) Minimum of 15 minutes, usually several times during a rush period, (< 1/900 HZ) Minimum of 5-15 minutes, per several cycles, (< 1/300 HZ) Continuous adjustments are made to all timing parameters, per several seconds (< 1/5 HZ) c Control strategy Pattern matching from pre-stored plans by static optimization Cyclic timing plan generating and matching via static/dynamic optimization Real-time timing adjusting via dynamic optimization and optimal control a,b Generations of UTCSs (G) G1 & G1.5a , e.g., SCATS[28] G2a, e.g., SCOOT[27] G3b , e.g., OPAC[29], RHODES[30],

ACS Lite[53]Coordination included Mostly yes Mostly yes Yes a Adopted from Klein et al.[14] and Stevanovic et al.[15]. b Summarized from Gartner et al.[52] and Wang et al.[16]. c Identified in this report drawn from across a number of studies. As shown in Table 2, all existing UTCSs are divided into the three outlined categories[14−16, 52]. The more advanced the control system, the higher the sensor density level and UTCS generation. At the same time, the responsive change frequency and control strategy are faster, higher, and more comprehensive. A detailed analysis of this is shown in the following sub-chapter 'comparisons and limitations'.

As shown in Table 2, the traffic-adjusted control uses both L1 (Level 1) and L1.5 sensor density levels, which means there is less than one sensor and up to one sensor per link. The responsiveness to demand is a slow reactive response with a minimum of a 15-min change frequency. This kind of control system is categorized as UTCS G1 (Generation 1) and G1.5. A typical, widely implemented example is SCATS.

Second, the traffic responsive control uses L2 sensor density level, which means there is one sensor per link up to one sensor per lane. The responsiveness to demand is prompt and reactive, with a minimum of a 5 to 15-min change frequency. This type of control system is categorized as UTCS G2. A typical example is SCOOT.

Lastly, the advanced adaptive control utilizes L3 sensor density level, which means that there are two sensors per lane. The responsiveness to demand is rapid and proactive, with a several-seconds-level change frequency. This type of control system is categorized as UTCS G3. Typical examples include OPAC, RHODES, and ACS Lite.

However, there are two significant limitations related to data quality and sensor costs because the current ASC systems are mostly utilizing data from infrastructure-based sensors[17, 30] that include video-based and pavement-based loop detectors. First, these infrastructure-based sensors are fixed-location sensors that are only providing the instantaneous individual vehicle data when a vehicle passes over the installation location. There is no spatial vehicle status, such as location, speed, and acceleration, provided by these point sensors. Second, the installation and maintenance costs of these point loop detectors are high. If any detectors are not working correctly, the performance of implemented ASC systems significantly degrades[17, 30]. The additional disadvantages of control strategies are existed. Thus, a significant need to develop new advanced approaches to fix the two limitations is still present.

Traffic signal coordination

-

Among various signal control strategies, traffic signal coordination is another important and widely implemented strategy with enhanced performance[19, 32]. Usually, the coordination system synchronizes traffic signals over the span of a corridor to provide signal progressions for approaching vehicles to reduce the number of stops and delays[19]. Even though the coordination control performs better than other control strategies for corridors, it still needs improvement.

To enhance the performance of the signal coordination, various methods[33, 34, 54−74] are proposed to achieve better performance measures. These approaches are classified into two categories of optimization methodology[19]: advancement of the quality of progression, like the classical MAXBAND[33], and optimization of a performance index, like using the mixed-integer traffic optimization program (MITROP) method[34]. This is shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Classifications of signal coordinations in UTCSs[19].

Category Adjusted control Responsive control Advanced adaptive control a Data quality: sensor density level (L) Same as Table 2 a Responsive to demand variations a Change frequency in control plan c Control strategy a,b Generations of UTCSs (G) Specific control strategy for Coordination Advancement of the quality of progression,

e.g., classical MAXBAND[33] and recent AMBAND[68]Optimization of a performance index,

e.g., MITROP[34]Regarding the first class, improving the quality of progression, many optimization methods have been tried to maximize green bandwidth[33,55−68]. Little et al. proposed several mixed integer linear programming (MILP)-based models to synchronize traffic signals for maximizing the bandwidth along a corridor; these proposed methods were called the MAXBAND series[33, 55,56]. Many extensions of the MAXBAND were then proposed considering more traffic variables and phenomena. Two classes that showed significant improvement are MULTIBAND[57−62] and PASSER series[63–67]. The MULTIBAND series was designed by Gartner et al.[57–62] to introduce the variable bandwidth progression considering dynamic changes in traffic volumes[19], while the PASSER series (progression analysis and signal system evaluation routine) proposed by Messer, Chang, and Chaudhary[63–67] further considered a phase sequence optimization method and a queue clearance method for the bandwidth maximization via heuristic algorithms. Recently, an asymmetrical multi-BAND (AMBAND) model proposed by Zhang et al. extended the MULTIBAND to achieve a broader bandwidth by relaxing the requirement of the symmetrical progression band[68].

Regarding the second category, optimization of a performance index, various algorithms have been proposed to improve one or more performance measures[34, 54, 69−74]. These performance indices include delay, travel time, number of stops, and their combinations. Several examples of these methods are described below in order to illustrate their effectiveness.

Early on, Gartner et al. developed the mixed integer traffic optimization program (MITROP) to minimize the platoon's average delays using a proposed platoon flow model and link performance function. The optimal offset values are determined by a piece-wise linear approximation of the platoon delay model[34]. Then, the faster computation was achieved by Köhler et al. using an extended, simplified formulation of the original model[69]. Hu & Liu recently developed an improved offset optimization method to minimize total delays using high-resolution loop detector data[70]. Also, an individual vehicle travel times data-based method was presented by Shoup & Bullock to achieve optimal offset settings using vehicle re-identification equipment[71]. Furthermore, a weighted combination function of the number of stops and the delay is used by several widely recognized signal optimization tools to obtain optimal coordination plans[19,72, 74,54].

However, since existing coordination systems are mostly based on fixed-location-based detectors and sensors, these sensors have two limitations related to data quality and sensor costs[19]. Also, the limitations of traffic prediction models and control strategies are given in the following sections. Thus, improving signal coordination is crucial.

Connected vehicle-based adaptive signal control

-

Most of the existing ASC systems rely on traffic conditions from fixed-location-based detectors[1, 17, 19]. Because of rapid advancements in emerging vehicular communication, CV-based signal control demonstrates significant improvements over existing conventional signal control systems[1, 19, 35, 36]. As already highlighted, CV technology features low latency, real-time data, high reliability, and large security in a fast-mobility condition, thereby providing a new perspective to solve the issues of signal controls. The real-time data includes connectivity indication, transmitted SPaT data, and vehicle status data extracted from the BSM and other data. Thus, by utilizing the CV-based data, traffic signal control strategies are more dynamically reactive to real-time fluctuations and changes in traffic conditions.

Various CV-based adaptive signal control approaches have been proposed, and they are divided into two types regarding their applied scopes: one type applies to a single isolated signalized intersection, and the other type applies to multiple signalized intersections.

In terms of methods aimed at an isolated signalized intersection, they[1,36,75−93] are categorized into different types according to their different performance indices. These performance indices include delay, queue length, waiting time, travel time, or a combination of them. This is shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Summary of the objective functions in the existing CV-based ASCs applied to both the isolated intersection and multiple intersections.

Author, year Objective functions+ Delay1 Queue length2 Waiting time3 Stop4 Travel time5 Type Gradinescu et al.[75] in 2007 Average delay 1 Chou et al.[76] in 2012 Vehicle and

Passenger delayStops * Nafi and Khan[77] in 2012 Average waiting time 3 Chang and Park[78] in 2013 Queue length Junction waiting time * Ahmane et al.[79] in 2013 Queue length 2 Cai et al.[80] in 2013 Travel time 5 Pandit et al.[81] in 2013 Delay 1 Lee et al.[82] in 2013 Cumulative

Travel time5 Kari et al.[83] in 2014 Travel delay 1 Guler et al.[36] in 2014 Total delay Stops * Tiaprasert et al.[84] in 2015 Queue length 2 Feng et al.[1] in 2015 Vehicle delay Queue length 1 Younes and Boukerche[85] in 2016 Delay 1 Feng et al.[32] in 2016 Vehicle delay 1 Islam et al.[88] in 2017 Queue length 2 Liu et al.[39] in 2017 Average waiting time 3 Cheng et al.[86] in 2017 Average waiting time 3 Feng et al.[87] in 2018 Total delay 1 Ban et al.[89] in 2018 Delay 1 Al Islam et al.[90] in 2020 Average delay Total travel time * Li et al.[91, 92] in 2021 Delay 1 Mo et al.[93] in 2022 Average delay 1 + Index type: 1 delay, 2 queue length, 3 waiting time, 4 stop, 5 travel time, * combination. For the delay index, which is the focus, Gradinescu et al. in 2007[75] proposed an ASC based on an optimization model to decrease the average delay. Pandit et al. in 2013[81] proposed an ASC based on the oldest arrival algorithm to minimize delays. Kari et al. in 2014[83] developed an agent-based online ASC to minimize travel delays via the arrival time prediction. Younes & Boukerche in 2016[85] presented a new ASC to minimize delays. Feng et al. in 2015[1] proposed an ASC using an enhanced controlled optimization of phases (COP) algorithm and an Estimation of Location and Speed (ELVS) method of unequipped vehicles to minimize vehicle delays. Feng et al. in 2018[87] presented a real-time detector-free CV-ASC to optimize total delays. Ban et al. in 2018[89] developed a new ASC method to reduce delays. Li et al. in 2021[91, 92] proposed a predictive model to investigate the ASC and signal coordination performances under low penetration conditions to minimize the delays. Mo et al. in 2022[93] developed a decentralized reinforcement learning-based signal control to optimize the average delays.

For the queue length index, Ahmane et al. in 2013[79] presented an ASC to minimize queue lengths. Tiaprasert et al. in 2015[84] presented a queue length estimation-based ASC to minimize queue lengths for both saturated and under-saturated conditions. Islam & Hajbabaie in 2017[88] proposed a distributed optimization method with a modified MILP for minimizing the queue lengths.

For the waiting time index, Nafi & Khan in 2012[77] introduced an ASC to minimize average waiting time. Liu et al.[39] developed reinforcement learning-based ASC systems. Cheng et al. in 2017[86] developed a Fuzzy group-based ASC to minimize average waiting time.

For the travel time index, Cai et al. in 2013[80] developed a travel-time-based ASC using approximate dynamic programming (ADP) to reduce travel times. Lee et al. in 2013[82] presented a cumulative travel-time-based ASC to minimize cumulative travel times.

For the combination index, which is the second key point, Chou et al. in 2012[76] presented a passenger feeling-based ASC to minimize passenger delays, as well as vehicle delays and stops. Chang & Park in 2013[78] proposed an ASC to reduce junction waiting times and queue lengths. Guler et al. in 2014[36] proposed an ASC based on a discharging sequence to decrease the total delay and number of stops. Al Islam et al.[90] in 2020 developed a real-time distributed framework for adjacent signal controllers.

Regarding proposed methods applied to multiple signalized intersections, they are described as follows[35,37,94]: In 2013, Goodall et al.[35] proposed a predictive microscopic simulation algorithm (PMSA) for the ASC. The algorithm obtains vehicle status data from CVs and inputs them into a microscopic-level simulation model to forecast near-future traffic flows. Then, a rolling horizon scheme with a 15 s interval was deployed to optimize a combination of several performance indices, such as delays, stops, and accelerations. The status of unequipped vehicles was estimated based on the status of the CV[94]. Considering the high computational costs of parallel simulations for the prediction process, this method cannot be used in real-time conditions[1]. Also, the performance degraded in undersaturated conditions. In 2013, Maslekar et al.[37] presented a clustering algorithm to obtain optimal cycle lengths, green intervals, and other parameters by estimating the density of approaching vehicles. A modified Webster's model was deployed to calculate cycle length. Simulations presented that the proposed method reduced the average waiting times and the number of stops. Also, though several research projects evaluated their models in both under-saturated and saturated traffic conditions in a CV environment[35, 42, 84], their performances could significantly decrease in both under-saturated and saturated conditions. To address saturated conditions, Christofa et al. (2013)[95] proposed queue spillback detection based on CV data then mitigated the queue spillbacks. In 2011, Venkatanarayana et al.[38] presented a signal control method using location and speed in the CV environment. The control strategy detected the real-time queue length at the downstream to responsively change splits at the upstream intersection. However, the method was only evaluated in a simple network.

Also, the use of recent machine learning and agent techniques to develop ASC for multiple intersections was demonstrated by Xiang & Chen in 2016[96]. Xiang at el. presented a multi-agent-based ASC. The intersection was modeled as an agent and was modeled by a Markov decision process. The signal control was optimized based on vehicle status, actions, and other parameters. However, this method did not consider the offset optimization in the CV environment, thus decreasing the effectiveness. Liu et al.[39] and Yang et al. in 2017[97] developed reinforcement learning-based ASC systems to obtain optimal timing plans. However, both systems still require a proper coordination to run along a corridor.

According to differences with respect to the three components, the existing CV-ASC systems are classified in Table 5.

Category CV-based basic ASC CV-based advanced ASC a, c Data quality: sensor density level (L)

and market penetration rate (Pcv)Mobile sensor data L4a, Pcv = 100%,

i.e., 100 % market penetration rateL3.5c & L4a, Pcv < 100% & Pcv = 100%,

i.e., both non-full and full market penetration rateEach connected vehicle (CV) regularly reports its location, speed, and possibly its destinationa b Responsive to demand variations Very rapid proactive response based on short-term traffic predictions b Change frequency in control plan (HZ) Continuous adjustments, per several seconds to per second (< 1 HZ) c Control Strategy Real-time timing adjustment via static optimization, dynamic optimization, and optimal control c Generations of UTCSs (G) G4c, e.g., work by Gradinescu et al.[75] G4.5c , e.g., PAMSCOD[42] and detector-free ASC[ 87] a Adopted from Klein et al.[14], Stevanovic et al. [15]. b Summarized from Gartner et al. [52], and Wang et al. [16]. c Identified in this report. As shown in Table 5, the first significant difference of CV-based ASC as compared to previous traditional ASC systems is the emergence of mobile sensor data introduced by CV technology. The second difference is that the CV-ASC has a higher change frequency (i.e., less than 1 HZ) in the control plan because of recently developed control strategies. This higher change frequency gives the CV-ASC systems faster response times to the demand variations.

According to the differences in the data types, i.e., different market penetration rates, these existing CV-based ASC systems are classified into two types: 1) basic CV-ASC, and 2) advanced CV-ASC. The basic CV-ASC system can only work in 100% market penetration rate conditions, while the advanced CV-ASC system can perform well in both partial and full market penetration rate conditions. However, a significant issue is that the real-time ASC performance degrades in low market penetration conditions. In addition, there are limitations to the prediction models and control strategies, as given in the following sections.

Connected Vehicle-based traffic signal coordination

-

The limitations caused by the infrastructure-based detectors[19], coupled with the substantial benefits of CV technology, have prompted the rapid development of both the CV-based ASC and CV-based signal coordination.

Several recent CV-based coordination approaches[19,32, 40-43, 46, 98, 99] have been introduced, aimed at improving the efficiency of the coordination systems. These approaches are briefly outlined in Table 6 by author, country/region, and institution.

Table 6. Summary of the CV-based advanced signal coordination systems’ research teams and outputs.

Author, year Country/

regionInstitution He et al.[42] in 2012 USA University of Arizona C.M. Day et al.[40] in 2016 USA Purdue University Li et al.[41] in 2016 USA Purdue University Feng et al.[32] in 2016 USA University of Arizona Beak et al.[19] in 2017 USA University of Arizona,

University of MichiganC.M. Day et al.[98] in 2017 USA Purdue University Remias et al.[46] in 2018 USA Purdue University Zheng et al.[99] in 2018 USA,

ChinaUniversity of Michigan,

Didi Chuxing LLCMo et al.[93] in 2022 USA Columbia University Further, these proposed approaches can be classified into two types, offline 'detector-free' offset optimization and online priority-based coordination, shown in Table 7.

Category CV-based advanced signal coordination systems a, c Data quality: sensor density level (L) and

market penetration rate (Pcv)Mobile sensor data L3.5c & L4a, Pcv < 100% & Pcv = 100%, i.e., both non-full and full market penetration rate b Responsive to demand variations Slow reactive response based on

historic traffic flowsRapid proactive response based on short-term predicted movements b Change frequency in control plan (HZ) Minimum of 15 min−3 h,

(< 1/900 HZ)Continuous adjustments, usually per cycle

(< 1/100 HZ)Minimum Pcv_min 0.1% for per 3 hrs change, 5% for

per 15 mins change25% for per cycle change Specific control strategy of coordination offline offset method,

e.g., detector-free method [98,40,41,46]online priority-based method,

e.g., adaptive coordination method[19,32,42]c Generations of UTCSs (G) UTCS G4.5c a Adopted from Klein et al.[14], Stevanovic et al. [15]. b Summarized from Gartner et al.[52], and Wang et al.[16]. c Identified in this report. As shown in Table 7, the first type is the so-called offline 'detector-free' offset optimization originated from Day et al.[98, 40, 41, 46]. These researchers presented detector-free offset optimization studies, where CV data-based trajectories were used to generate 'virtual detections'. Then, arrival profiles created by virtual detections were used to obtain signal offset optimization for signal coordination. Later, an extension model of this method was proposed to better determine coordination plans under low penetration rate conditions[43] by integrating similar historical automated vehicle location data. In 2018, Zheng et al.[99] proposed a method to utilize CV-based trajectory data to assess signal coordination quality, thus optimizing the traffic signals. However, the current detector-free methods are not capable of real-time signal coordination control use[100], which means they do not feature CVs' real-time data.

The second type is an online priority-based method, which is shown in Table 7. This method has a higher frequency response to demand variations but requires a high market penetration, i.e., Pcv_min = 25%. Feng et al. evaluated an online coordination with fixed offset values in a CV environment, where the coordination was integrated with an adaptive control algorithm in a high penetration rate situation[32]. The model was then extended to optimize offsets along a corridor using a CV-based corridor-level optimization[19]. However, the optimal common cycle length was determined offline by average flow data, which degenerates optimal effectiveness. Also, He et al. tested a platoon-based arterial signal control using the CV technology that included the dynamic signal coordination for both under-saturated and saturated traffic conditions[42]. Within their method, they tried to obtain a multi-modal dynamical progression for significant platoons by considering existing queue delays. In addition, Li et al. investigated a platoon-based bicyclic coordination diagram (Bi-PCD) for offset optimization in a CV environment[101]. However, CV penetration rates significantly influence the positive performances of those CV-based algorithms discussed above, which presents a challenge[19, 32, 42]. The prediction results are sensitive to market penetration rates because variations are largely yielded in low penetration rate conditions[19, 42].

Consequently, one problem is that the real-time coordination performance degrades with incomplete information in low market penetration conditions. In other words, achieving progressive improvements in online CV-based coordination methods with higher response frequencies in lower penetration rate conditions is critical. Also, the limitations of prediction models and control strategies are given in the following section.

-

In this section, we present some comparisons and limitations for these existing methods reviewed in the previous contents. As was shown in Fig. 1, there are three basic components in the existing traditional (non-CV-) and CV-based (CV-) ASC and coordination systems: 1) data quality, 2) traffic model, and 3) control strategy.

Several of the previous tables are put together now to clarify significant differences among different non-CV- and CV-based ASC and signal coordination systems. The summarized tables are shown in Tables 8 & 9.

Table 8. Fine classifications of traditional (non-CV-based) and CV-based ASC*.

Category Non-CV-based

Adjusted controlNon-CV-based

Responsive controlNon-CV-based

Advanced adaptive controlCV-based

Basic ASCCV-based

Advanced ASCa Data quality: sensor density level (L) Static sensor data Mobile sensor data L1 & L1.5, less than

one sensor up to one sensor per linkL2, one sensor per link up to one per lane L3, two sensors per lane L4a, Pcv = 100%, i.e., 100% market penetration rate L3.5c & L4a, Pcv < 100% & Pcv = 100%, i.e., both non-full and full market penetration rate a Responsive to demand variations Slow reactive

response based on

pre-calculated historical traffic flowPrompt reactive response based on changes in regularly disrupted traffic Very rapid proactive response based on short-term predicted movements Very rapid proactive response based on short-term traffic predictions a Change frequency in control plan

(HZ)Minimum of 15 min, usually several times during a rush period,

(< 1/900 HZ)Minimum of 5−15 min, per several cycles,

(< 1/300 HZ)continuous adjustments are made to all timing parameters, per several seconds

(< 1/5 HZ)Continuous adjustments, per several seconds to per second (< 1 HZ) c Control strategy Pattern matching from pre-stored plans by static optimization Cyclic timing plan generating and matching via static/dynamic optimization real-time

timing adjustment via dynamic optimization and optimal controlReal-time timing adjustment via static optimization, dynamic optimization, and optimal control a,b Generations of UTCSs (G) G1 & G1.5a,

e.g., SCATS[28]G2a, e.g., SCOOT[27] G3b, e.g., OPAC[29], RHODES[ 30],

ACS Lite[53]G4c, e.g., the work by Gradinescu et al.[75] G4.5c, e.g., PAMSCOD[42] and detector-free ASC[87] Coordination included Mostly yes Mostly yes Yes Mostly yes Mostly yes Traffic model Microscopic/ macroscopic/ mesoscopic models Mostly microscopic models * Summarized from previous Tables 2 & 5, where further details of the above notations are available. Table 9. Fine classifications of traditional (non-CV-based) and CV-based signal coordination*.

Category Non-CV-based

Adjusted controlNon-CV-based

Responsive controlNon-CV-based

Advanced adaptive controlCV-based

Advanced signal coordination systemsa Data quality: sensor density level (L) Static sensor data Mobile sensor data L1 & L1.5, L2, L3, L3.5c & L4a, Pcv < 100% & Pcv = 100%, i.e., both non-full and full market penetration rate a Responsive to demand

variationsSame as Table 8 Slow reactive response based on historical traffic flows Rapid, proactive response based on short-term predicted movements a Change frequency in control plan

(HZ)Minimum of 15 min−3h,

(< 1/900 HZ)Continuous adjustments,

usually per cycle

(< 1/100 HZ)c Minimum Pcv_min 0.1% for per 3 hrs change,

5% for per 15 mins change25% for per cycle change a,b Generations of UTCSs (G) G4.5c , Specific control strategy for Coordination Advancement of quality of progression,

e.g., classical MAXBAND[33] and recent AMBAND[68]Optimization of a performance index,

e.g., MITROP[34]Offline offset method, e.g., detector-free

method[98,40,41,46]Online priority-based method,

e.g., adaptive coordination method[19,32,42]Traffic model Microscopic/ macroscopic/ mesoscopic models Mostly microscopic models * Summarized from previous Tables 3 & 7, where further details of the above notations are available. Some rough descriptions of these existing systems from the three perspectives are given. After that, a detailed limitation analysis is presented.

There are several preliminary observations from these two tables. First, a data paradigm shift appears; the mobile sensor data almost replaces the traditional static sensor data. Also, new issues related to data quality emerge in the data paradigm shift when switching to the new mobile sensor data basis.

Second, the control strategies feature fewer delays and better real-time and efficient response performance over time, but they are becoming more complex. For example, the most advanced control methods are always adopted in the most recent CV-based signal control systems.

Lastly, various traffic models are widely used in both traditional ASC and signal coordination systems. These models include different major micro-/meso-/macroscopic models. On the other hand, traffic models included in the emerging CV-based ASC and signal coordination systems are mostly dependent on microscopic models.

The above discussions are summary descriptions of the existing systems from three perspectives: data, traffic model, and control strategy. A further detailed comparison and limitation analysis of them is given in the following sections.

Traffic data

Static (fixed) sensor data

-

As shown in Tables 8 & 9, the traditional ASC and signal coordination systems are based on fixed location-based detectors with different sensor density levels[17, 30]. These fixed location-based sensors include video-based and pavement-based loop detectors. They generate static sensor data, including occupancy, flow data, and speed profiles.

However, there are several limitations to traditional fixed detector-based static sensor data related to data quality and sensor costs. First, these sensors are fixed-location detectors that only give instantaneous individual vehicle data when a vehicle passes through the installation location. There is no direct spatial vehicle data provided by these point sensors, such as location, speed, and acceleration.

Second, the installation and maintenance costs of these sensors are significantly high. These high installation and maintenance costs make re-installations and functional operations of detectors inefficient. Thus, if any detectors are operating inefficiently or incorrectly, the performance of the implemented urban signal control systems can significantly degrade to low levels[17, 30]. Additionally, proactive information, like signal priority request commands, cannot be integrated into the static sensor data. This limitation can incur additional device installation and maintenance costs when implementing a priority-based traffic control, like transit priority control.

Mobile (CV-based) sensor data

-

CV technology features low latency, real-time data, high reliability, and high security in a high-mobility environment. Each CV regularly broadcasts its position, speed, and possible destination. Thus, when compared to the static sensor's data quality and costs, it avoids the previous two limitations by its advantages of real-time spatial motion reports and low installation and maintenance costs. More importantly, CV technology enables a vehicle to acquire SPaT data from signal controllers and issue a signal priority request to signal controllers, something beyond the capability of fixed sensors.

However, during the initial implementation stage of CV technology, not every vehicle is a CV. Consequently, the initial stage is characterized by a low market penetration rate situation that possesses two major drawbacks.

First, during the initial deployment stage, there are limited numbers of CVs on the road generating limited amounts of CV data. Consequently, the limited CV data volume degrades the performance of the CV-based signal control system[19, 43,102,103].

Second, there are large numbers of non-CVs on the road at the same time. They are not connected, and their motion information is missing. This lack of non-CV data creates uncertainties for performance quality as well as large fluctuations and disturbances within the road traffic, thereby increasing computation complexity when obtaining optimal timings[17]. In addition, the high frequency of data exchange also increases data disturbances and fluctuations, thus adding to the complexity of the CV environment.

A summary of the above comparisons and limitations is given in Table 10.

Table 10. Summary of the data comparisons and limitations for both the static and mobile sensor data.

Data Type Spatial-temporal

property of traffic dataCost* Extra proactive data Pros/

ConsStatic sensor data Instantaneous data at fixed location High No Cons Mobile sensor (CV) data Full penetration Complete spatial and temporal CV data, high frequency of data exchange Low Yes, e.g., priority request data Pros Low penetration Limited CV data Cons Large missing of non-CV data * Usually considering the installation and maintenance cost. As shown in Table 10, the mobile sensor data outperforms the traditional static sensor data in three respects: 1) spatial-temporal property, 2) cost, and 3) the capability to provide extra proactive data. However, it still has two issues in low penetration conditions, which are the limited CV data and the missing non-CV data. These two issues need to be resolved in order to provide better control performance. Additionally, an exploration of the new method is also needed to utilize the extra proactive data fully.

CV-based signal control systems in low penetration rate conditions

-

Low penetration conditions cause two critical issues: 1) the limitations on CV data and 2) missing non-CV data. Some current research works aiming to solve these issues in the CV environment are discussed below.

(a) Limited CV data. Most of the existing CV-based ASC and signal coordination methods do not design unique methods to overcome this issue. Thus, these widely accepted practical studies can only perform well with sufficient CVs, i.e., when the penetration rate is above a minimum penetration rate. Results of different minimum penetration rates (Pcv_min) are identified in many studies[40, 87, 94]. There are few studies[19, 40, 41, 46, 87, 98] that worked at solving this problem. From 2016 to 2018, Day et al.[98, 40, 41, 46] proposed a detector-free coordination series based on historical limited CV data. However, their work was not implemented in real-time conditions. In 2017, Beak et al.[19] tested a stop-bar detector-assisted method to achieve adaptive coordination. In 2018, Feng et al.[87] presented a real-time detector-free CV-ASC using a probabilistic estimation model based on both a prior arrival distribution assumption and historical CV data.

In 2020, Islam et al.[90] developed a real-time distributed signal coordination framework by exchanging information between adjacent signal controllers. In this framework, non-CV trajectories are estimated by car-following concepts based on both loop and CV data. Also, the spatial vehicle distributions over the road segment are estimated by temporal CV data. In 2021, Li et al.[91, 92] proposed a probabilistic single-vehicle-based predictive model to investigate the signal coordination performances under low penetration conditions. In 2022, Mo et al.[93] developed a decentralized reinforcement learning-based signal control for signalized intersections. Both non-CV and CV data are used for offline training in low penetration conditions, while only CV data are utilized in the real-time signal control. Recently, in 2022, Zhang et al.[104] also presented a hybrid offline-online signal control strategy. In this framework, an offline signal parameter optimization is developed first, followed by an online deep recurrent Q-learning (DRQN) signal optimization. Specifically, a Bayesian deduction is utilized to estimate the traffic volumes.

Thus, there is no applied method to solve this issue in low (around 10%) and ultra-low (around 5%) penetration conditions when considering real-time.

(b) Missing non-CV data. Similar to the concern of limited CV data, most of the existing CV-based ASC and signal coordination systems do not design specific methods to overcome this issue. A few researchers[1, 94] have tried methods that estimate the status of unequipped vehicles. In 2014, Goodall et al.[94] utilized a micro-simulation-based method to estimate non-CV locations, but it could not be applied in real-time. In 2015, Feng et al.[1] extended Goodall's method by proposing an estimation algorithm of the vehicle location and speed (EVLS) based on Wiedemann's model. However, Wiedemann's model still needs further extensions, and there is no field validation for this proposed method.

A summary of the existing methods for these two issues are shown in Table 11.

Table 11. Summary of studies targeting the low-penetration issue for urban signals.

Low penetration

rate issueLimited CV data issue Missing of non-CV data issue CV

applicationsMin Pcv Proposed methods Goodall et al.[94] in 2014 n/a Micro-simulation-based estimation

of the non-CV positionCV-ASC 10%−25% Feng et al.[1] in 2015 n/a EVLS algorithm CV-ASC 25%−50% Day et al.[98, 40, 41, 46] from

2016 to 2018Historical limited CV data-based aggregation n/a detector-free coordination 5%,

15 mins

changeBeak et al.[19] in 2017 Stop-bar detector-assisted method n/a adaptive coordination 25% Feng et al.[87] in 2018 Probabilistic model based on both prior arrival distribution and historical CV data n/a CV-ASC 10% Al Islam et al.[90 ] in 2020 Spatial vehicle distribution estimation by CVs vehicle trajectories via both the loop and CV data CV-ASC and coordination 0%, 10% Li et al.[91, 92] in 2021 Vehicle-triggered platoon dispersion n/a CV-based coordination 5%, 10% Mo et al.[93] in 2022 Decentralized learning method n/a CV-ASC 10% Zhang et al.[104] in 2022 Bayesian deduction n/a CV-ASC 5%, 10% In conclusion, the existing studies that are aiming at solving two issues in low penetration rate conditions have their drawbacks. Thus, research on this topic is still needed.

Traffic model

-

As shown in Tables 8 & 9, the second observation is that various traffic models are used in the traditional ASC and signal coordination systems. These models include different micro-/meso-/macroscopic models.

However, models included in the emerging CV-based ASC and signal coordination systems are based mostly on microscopic models. The following content gives a brief review of existing traditional and CV-based signal control systems.

Microscopic models

-

Microscopic models describe details of various components' behaviour that makeup moving traffic streams on the road[105−107]. These components include vehicles, roadside controllers, static detectors, road geometry, and so on. The most widely used microscopic models are various car-following models and lane-change models.

However, there are several limitations to microscopic simulation models[105−107]. First, the microscopic modeling of large participated components like vehicles introduces a large computational cost when simulating large arterial networks. The second is that the digital coding of the road surface network incurs substantial complexity and financial cost. Third, there is limited availability of the real-time control plans from modern controllers when requiring complete information. In particular, there is a lack of SPaT data dynamic descriptions. Last, it is challenging to obtain details of the fluctuations and disturbances from the surrounding traffic demands and traffic streams.

Mesoscopic models

-

Mesoscopic models are usually identified to fill the gap between high-level aggregations of macroscopic models and high-level disaggregations of microscopic models and work at an intermediate level of detail[105–107]. Typically, these popular mesoscopic models are classified into three types[105−107]. The first type is the queuing approach for both freeways and signalized arterial roads. In this method, the queuing theory is introduced to model interaction between arrival patterns and signal status. The second form is the cellular automata-based method. In this method, the road is discretized into cells that each vehicle can occupy based on specific rules. The last alternative groups individual vehicles into packets or cells. The packet or cell controls the aggregate individual vehicles.

However, due to high-level aggregated representations of traffic streams and road geometry in these mesoscopic models, dynamic behaviour of facilities cannot be accurately analyzed or replicated[105–107]. Mainly, it lacks dynamic descriptions of the SPaT data. Also, large participating components like vehicles introduce huge computational costs when simulating big arterial networks.

Macroscopic models

-

There are various macroscopic models that describe the moving traffic stream at a high level of aggregation as traffic flow[105−107]. Macroscopic models are a widely used strategy within many UTCSs. Various typical UTCSs[15, 108−110] that applied different macroscopic traffic models from 1960s to 2010s are shown in the following Table 12. These macroscopic models can be classified into three generalized as well as typical types: dispersion-and-store model (DSM), cell transmission model (CTM), and store-and-forward model (SFM).

Table 12. Summary of traditional UTCSs applied different traffic models.

Decade Typical UTCSs Dataa Global optimization formulation

and/or solution algorithmTraffic model 1960s TRANSYT in UK in 1968 Loop data Domain-constrained optimization DSM model[15] 1970s SCATS in Australia in 1979 SL, Loop data Strategic and tactical control Flow-delay profiles[15] SCOOT in UK in 1979 US, Loop data Domain-constrained optimization Flow-occupancy profiles, DSM model[15] DYPIC in UK in 1974 [108] US, Loop data Backward dynamic programming[108],

Rolling horizon approachDSM model 1980s -1990s OPAC in US in 1983[15] MB & SL, Loop data Complete enumeration / exhaustive enumeration[111, 112],

Rolling horizon

approachDSM model[15] RHODES in US in 1992[ 15] MB & SL, Loop data Dynamic programming[111, 112], Rolling horizon approach[30] DSM model[15] UTOPIA /SPOT in Italy in 1985[15] US & SL, Loop data Online dynamic optimization and off-line optimization[108] , Rolling horizon approach[113] DSM model PRODYN in France in 1984[108] US, Loop data Forward dynamic programming[111, 112] ,

Rolling horizon approach[109]DSM model 2000s ACS-lite in US in 2003[15] US, Loop data Domain-constrained optimization, three

levels of optimization methodologyDSM model 2010s Aboudolas et al. in 2010[109] AL, Loop data Quadratic programming, Rolling horizon approach SFM model Liu & Qiu in 2016[110] US & SL, Loop data Multi-objective optimization problem and

an evolutionary algorithmExtended SFM model Hao et al. in 2018[114, 115] US, Loop data Model predictive control-based method integrating optimizations CTM model Han et al. in 2018[116] n/a Linear quadratic model predictive control Extended CTM model Lu et al. in 2019[117] n/a Explicit model predictive control SFM model Pedroso and Batista in 2021[118] US Decentralized and decentralized-decoupled traffic-responsive urban control Decentralized SFM Souza et al. in 2022[119] Loop data, Historical data Integrating signal control and routing Multi-commodity SFM a SL = stop-line, MB = mid-block, US = upstream, AL = arbitrary location, adopted from Stevanovic et al. [15] and Aboudolas et al.[109]. (a) Dispersion-and-store model (DSM)[73,120, 121]. The DSM, originally proposed by Pacey et al. in 1956 and Robertson in 1969[73,120−123], is an empirical observation mimicking both the platoon dispersion behaviour during a green signal and platoon storage during a red signal. Usually, two forms are used for this modeling: a normal distribution form and a geometric distribution form. The geometric distribution form is also called Robertson's Platoon Dispersion Model (RPDM) and has been widely incorporated in many UTCSs, e.g., SCOOT[120, 121]. However, the DSM cannot model real-time precise complex queue formulation and dissipation since the road segment between any two adjacent intersections is considered as one link. In addition, its adaptiveness to traffic fluctuations is difficult to calibrate[124].

(b) Cell transmission model (CTM). The CTM proposed by Daganzo in 1994[125] discretized the continuum of Lighthill & Witham's kinematic model (LWR) into multiple cells. In this case, the road network is represented by many small cells. One cell's vehicle dynamics are based on a transition process between two consecutive cells. In 2018, Hao et al. extended the CTM to an extended urban cell transmission model (UCTM) to obtain the average travel delays of the vehicles in the upstream approaches of each intersection[114, 115]. However, the major disadvantage of CTM is that the fine discretization of the arterial network requires substantial computational complexity and sensor density. A shortage of sensors and limited computational capability significantly degrade the performance of CTM-based control methods[124].

(c) Store-and-forward model (SFM). Gazis et al. originated the SFM model in 1965, which was extended by Aboudolas et al. in 2009 to model traffic dynamics in congested arterials[112]. Similar to CTM, vehicles in the SFM model are either stored within the current link in the red signal or forwarded to the next link in the green signal. The link dynamic is given by the conservation law. The most significant characteristic of the SFM is that the discrete time step Tk is equal to cycle length C, i.e., Tk = C[124]. This leads the model to describe a continuous (uninterrupted) average outflow from each link outside of the consideration for a queuing formulation or for dissipation due to a green-red switching mechanism[112]. In other words, SFM has difficulty modeling real-time accurate complex queue formulations and dissipations, similar to the disadvantage of the DSM. This model only provides an efficient representation of the dynamics in congested networks.

In conclusion, the dynamics of facilities are not accurately analyzed and replicated[106, 107, 126], similar to the disadvantages of mesoscopic models with the high-level aggregated representation of the traffic streams and road geometry. For example, macroscopic models lack dynamic descriptions of the SPaT data. Also, DSM, CTM, and SFM have the difficulty with modeling real-time accurate complex queue formulations and dissipations. In other words, there is a problematic level of performance degradation because of queuing uncertainties.

Hybrid models

-

The hybrid models that combine the advantages of two or more levels of the individual models, emerge as possible solutions[127]. There are two major types: mesoscopic–microscopic models and macroscopic-microscopic models[107, 128]. Usually, researchers aim to integrate the strengths of macroscopic or mesoscopic models (better modeling of large networks and easier calibrations) with microscopic models (greater details and modeling control strategies capability)[107, 128]. However, all of these studies are based on simulations that have extraordinary computational complexity. Consequently, existing research studies[107, 127, 128] are only suitable for offline verification and evaluation of different ITS and signal strategies rather than for real-time signal control use.

Models in CV-based ASC and coordination systems

-

Most of the existing CV-based ASC[1,36, 75−87] and signal coordination[19,32, 40−43, 46, 98] systems depend on microscopic models. Thus, they suffer the problems described above in the sub-chapter 'microscopic models'. One major issue is that performances degrade because of a shortage of sensors and computational capability.

There are not many works utilizing the mesoscopic models and macroscopic models for the CV-based ASC and signal coordination. Zhang et al. in 2022[129] demonstrate a distributed queueing model to improve the signal control performances in an edge computing environment. Chen & Qui in 2021[130] implement the CTM with dynamic routing plans for a distributed signal control in an edge computing environment. Souza et al. in 2022[119] propose a multi-commodity SFM utilizing a destination-based turning rate to improve signal control performances. Yao et al. from 2019 to 2020[131−134] proposed a real-time dynamic dispersion model in a CV environment, where travel time, vehicle speed, vehicle location, or their combination is utilized. Li et al. in 2021[92] proposed a predictive dispersion model to investigate signal coordination performances under low penetration conditions in a CV environment.

To the best of our knowledge, none of the existing CV-based ASC and signal control systems are based on hybrid models. Thus, they cannot benefit from the advantages of the hybrid models.

Control strategy

-

The second observation, as summarized in Tables 8 & 9, is that the control strategies feature fewer delays, and better real-time and more efficient response performance over time whilst, at the same time, are becoming more complex. The responsiveness to demand has upgraded from a slow reactive response to rapid proactive response. The change frequency of the control plan is evaluated to around 1 HZ for traditional advanced ASC and CV-based advanced ASC. As for the CV-based signal coordination, the offset is quickly adjusted at per cycle level.

What is apparent is that these adopted control strategies are becoming more complex over time. In this study, these control strategies are divided into three types: (1) static optimization-based basic control strategy[135], (2) dynamic optimization-based intermediate control strategy[135], and (3) model predictive control (MPC)-based advanced control strategy[136].

Static optimization

-

A static optimization-based basic method refers to a method where a signal control system achieves an optimal timing plan by solving a static optimization problem. The word 'static' used in the term 'static optimization' means that objective functions and constraints are time-independent, where they are focusing on the current time step. Most of the existing methods[15] utilizing static optimization omit the term 'static'. However, this thesis uses the term 'static optimization' to clarify and claim the time-independent characteristics of these methods. Usually, mathematical programming, e.g., linear programming (LP), mixed integer linear programming, is used for solving this static optimization.

This static optimization-based basic control strategy is used in various traditional adjusted control and responsive control systems, e.g., SCATS. Furthermore, if no other feedback control methods (e.g., rolling horizon method[109]) are added, the static optimization-based method is an open-loop system without a feedforward control. Consequently, it causes these control systems to have slow reactive responses with a slow change frequency to demand variations. This means that these systems are readily affected by traffic demand fluctuations and traffic stream disturbances.

Thus, the static optimization-based method has limited capability to optimize timing plans in high-dynamic conditions. The control performance is significantly affected by traffic demand fluctuations and traffic stream disturbances.

Dynamic optimization

-

Compared to the basic control strategy using 'static optimization', 'dynamic optimization' is widely used in the intermediate control strategy and is a method whereby the decision variables of constraints involve sequences of decisions over time or multiple periods[135]. In other words, it has a dynamic model, i.e., traffic model, as a constraint to describe traffic dynamics, whereby the traffic model can be either a microscopic, a mesoscopic, or a macroscopic model. The deployed traffic model predicts the future status of the traffic system. Usually, this type of control system is labeled as a model-based control.

Without adding other feedback control strategies (e.g., rolling horizon method[109]), this dynamic optimization causes the intermediate control strategy to be an open-loop system with a feedforward control. Thus, this intermediate control strategy performs better than the basic control strategy since it has a prior feedforward control and is adopted in most responsive control systems and advanced adaptive control systems, as shown in Tables 8 & 9. Typical examples include SCOOT[27], MOTION[31], BALANCE[15], ACS Lite[53], MOVE[15], OPAC[15], RHODES[15], UTOPIA[15], PYODYN[15], DYPIC[15], and Aboudolas et al.[109] amongst others.

In order to solve dynamic optimization problems, there are several proposed methods: (a) dynamic programming (DP), (b) rolling horizon approach, and (c) other intelligent approaches.

(a) Dynamic programming (DP). Dynamic programming is a technique that can be used for solving many optimization issues over time (i.e., dynamic optimization)[124, 135]. In most applications, DP breaks the original large-scale and complex problem into a series of small, solvable problems by Bellman's equation. DP has been used in some signal control systems, including OPAC V1[15] and studies by Caceres et al.[137−140]. However, the DP method has problems to overcome for the real-time control[108]. In detail, the DP method requires complete future information for the optimization horizon, which is very hard to achieve in the real-time operation since the upstream sensor may only provide 5-10 s future vehicle arrival data.

(b) Rolling horizon approach. The rolling horizon approach refers to a 'rolling planning horizon' that has a rolling mechanism with a planning horizon consisting of Kp time intervals[108, 124]. The planning horizon has two portions: a head portion with first KH time intervals and a remaining tail portion with next ( Kp − KH ) time intervals. The traffic status is updated by measured data during the head portion and predicted by traffic models during the tail portion. The dynamic optimization is then solved during the whole planning horizon with the measured and predicted traffic status. Thus, a sequence of optimal control actions (e.g., split, offset) over the whole planning horizon is obtained. In practice, only the first optimal control action[108, 124] or a sequence of control actions over the head portion[111] is implemented. After that, a rolling mechanism is applied, in which the planning horizon moves forward into the future by one rolling period, and the above routine is repeated. Moreover, the rolling horizon approach introduces a feedback loop that further increases the system's performance. Various traditional UTCSs[15,108−110] that have applied the rolling horizon approach are shown in Table 13.

Table 13. Summary of traditional UTCSs using the rolling horizon approach.

Typical UTCSs Dataa Rolling horizon approach Global optimization formulation and/or solution algorithm OPAC[15] MB & SL, Loop data Yes[15] Complete enumeration (CE) / exhaustive enumeration[111, 112] RHODES[15] MB & SL, Loop data Yes[30] Dynamic programming[ 111, 112] UTOPIA/SPOT[15] US & SL, Loop data Yes[113] Online dynamic optimization and off-line optimization[ 108] PRODYN[108] US, Loop data Yes[109] Forward dynamic programming[111, 112] DYPIC[ 108] US, Loop data Yes[ 108] Backward dynamic programming[ 108] Aboudolas et al.[109] in 2010 AL, Loop data Yes Quadratic programming Liu & Qiu[110] in 2016 US & SL, Loop data Yes Multi-objective optimization problem and an evolutionary algorithm Hao et al.[114, 115] in 2018 US, Loop data Yes MPC-based method integrating optimizations, CTM model Jamshidnejad et al.[141] in 2018 Loop data Yes Sustainable model-predictive control, S-model Han et al.[116] in 2018 Loop data Yes LQ-MPC, extended CTM, corridor Lu et al.[117] in 2019 Loop data Yes Explicit model predictive control (EMPC), SFM model Pedroso & Batista[118] in 2021 Loop data One-step Decentralized and decentralized-decoupled traffic-responsive urban control, Decentralized SFM Souza et al.[119] in 2022 Loop data Yes Integrating signal control and routing, Multi-commodity SFM a SL = stop-line, MB = mid-block, US = upstream, AL = arbitrary location, adopted from Stevanovic et al. [15] and Aboudolas et al. [109]. However, there is a concern that the rolling horizon approach does not always abide by the optimality principle if the parameter design (e.g., length of the projection horizon) is not well devised[124]. The concern is that the rolling horizon approach causes a disadvantage where it degrades its performance in highly dynamic environments, especially in CV environments.

(c) Intelligent approaches. Intelligent approaches use other models that usually are not traffic models to update timing plans. There are several typical examples: the Fuzzy logic-based system like Jin et al. in 2017[50], the deep learning (DL)-based system like Gao et al. in 2017[51], the reinforcement learning (RL) technique like Mo et al.[93] in 2022, and the distributed signal control using the emerging edge computing technique like Chen et al.[142] in 2022. This is shown in Table 14.

Table 14. Summary of UTCSs using modern intelligent approaches.

Typical works Platforma Intelligent strategy Control features Jin et al.[50] in 2017 Embedded device Fuzzy-based A fuzzy group-based approach, machine-to-machine connectivity Gao et al.[51] in 2017 Centralized structure Deep reinforcement learning-based Convolutional neural network for automatic feature crafting, experience replay and target network for stability Wu et al.[143] in 2019 Edge computing Deep reinforcement learning-based Distributed reinforcement learning Zhou et al.[144] in 2021 Hierarchical structure Deep reinforcement learning-based Multi-agent training with rich CV data, hierarchical control Zhang et al.[145] in 2021 Edge computing Deep reinforcement learning-based Multi-agent actor-critic control, value decomposition, a cooperative scheme Wu et al.[146] in 2022, Edge computing Deep reinforcement learning-based Game theory-aided reinforcement learning Wang et al.[147] in 2022 Edge computing Deep reinforcement learning-based Social features and connections Mo et al.[93] in 2022 Decentralized Deep reinforcement learning-based Asymmetric advantage actor-critic, non-CV, and CV data for offline training, CV data for online control Chen et al.[142] in 2022 Edge, distributed Distributed dynamic route-based Distributed backpressure principle, dynamic route control However, for these Intelligent approaches, like either a deep learning-based or a reinforcement learning-based method, the sophisticated learning structure for the low penetration conditions is still missing[93]. In addition, the detailing mechanisms of raw CV data types and amounts, and their real-time controlling capabilities for either centralized or distributed signal control are still remaining unclear[93].

Model predictive control (MPC)

-

A special advanced model-based control strategy called model predictive control (MPC) is considered in this section[113, 136]. MPC is the most widely accepted modern control strategy to offer a compromise between optimality and computation speed[136]. Generally speaking, MPC-based traffic control utilizes both a traffic model and the current traffic state to predict the dynamic evolution of traffic states, then applied to obtain optimal signals. An MPC controller includes several basic components, including a state estimation module, a state evolution model, and an optimization module[113], with further details of MPC outlined by Kouvaritakis & Cannon[136]. It is widely recognized that MPC can further decrease the adverse effects of traffic disturbances[148].

Traffic controls that explicitly use MPC were originally proposed by Bellemans in 2003[149] and Hegyi et al. in 2005[150] for both ramp metering (RM) and the variable speed limit (VSL) studies on freeways. In recent years, Hegyi et al.[113, 151], Papageorgiou et al.[148, 152], and Wang et al.[153−156] further summarized, extended, and validated the MPC-based RM and VSL studies on freeways. Studies that focus on traffic signal controls that explicitly employ MPC focus on congested arterial networks include Dotoli et al.[157], Aboudolas et al.[112], Lin et al.[158], Liu & Qiu[124, 159], and Baldi et al.[160]. Only few works explored performance in non-congested arterials[114, 115] .

There are other traffic control systems[15,108] that use similar schemes, shown in Table 13. These systems also obtain optimal signals by applying predictions and models, but they are not formulated and implemented explicitly to the MPC structure correspondingly[113]. Thus, these systems cannot feature the benefits of MPC without simultaneously solving their problems.

Although MPC shows good performance ability in RM and VSL control on freeways and signal control on congested arterials, several concerns arise concerning its capability on non-congested arterials. First, the traffic dynamic and signal mechanism are more involved in under-saturated arterials without a simplified traffic model, causing a lack of computational tractability. Second, the performance of traffic control systems can degrade from unpredictable demand variations and traffic disturbances on the road when using an open-loop prediction model of the MPC. The reason for the open-loop structure is that the nominal future demand and signal control variables are still functions of time.

Control strategies in the CV environment

-