-

Botanically, coffee belongs to the family Rubiaceae and the genus Coffea[1]. Initial studies by de Jussieu named the crop as Jasminum arabicanum in 1713 by studying a sample of the tree that originated from the botanical garden of Amsterdam[2]. Unlike some other tree crops, coffee has the advantage of ubiquity and drives a multibillion dollar global coffee industry[3], supports the economy of several tropical countries and by extension provides livelihoods for more than 100 million coffee farmers and their households[4]. On a global scale, Brazil is the world's largest producer of coffee producing 3,558,000 MT (accounting for around one-third of the world's coffee) followed by Vietnam with a production volume of 1,830,000 MT[5].

The species Coffea has n = 11 as its basic chromosome number, except C. arabica being the only coffee that is polyploid and self-fertile in nature with a chromosome number of 2n = 4x = 44[6]. Other Coffea species such as C. canephora are however diploid (2n = 2x = 22) and self-infertile[6] and need the effort of breeders for commercial production and productivity. As reviewed by Davies et al.[7], the Coffea genus is comprised of 124 species (in cultivation and in the wild). This gives a clear indication that more research needs to be undertaken to develop cultivars that can withstand the test of time particularly amidst changing climate.

Regardless of breeding overtime, progress on developing climate-resilient coffee is at the initial stages, with attention focused on Arabica (C. arabica) and Robusta (C. canephora)[8,9]. These two species are reportedly said to have a well-defined price difference with Arabica having a higher price in the international market[3] probably due to its superior cup quality. On the other hand, Robusta and Liberica, currently have lower prices serving as alternative sources to Arabica. Like C. stenophylla, C. eugenioides is another minor coffee species believed to have excellent flavour and is gradually gaining popularity as a niche market though the seeds are relatively small[10].

In Sierra Leone, cultivated coffee varieties are mainly Robusta and Liberica with Robusta dominating the market probably due to its high yielding quality and the only commercially viable variety. C. liberica can only be found in pockets either in Robusta plantations or in abandoned farmlands. As a result of cyclic price volatility and extreme weather conditions, coffee production has several challenges[7] in Sierra Leone leading to near abandonment of plantations with little or no proper maintenance. This commodity together with cocoa serves as a source of livelihood for thousands of smallhold farmers representing 96% of the country’s agricultural export[11]. Furthermore, SLIEPA[11] reported that in 2011, trade figures revealed that 198,000 MT of cocoa and coffee were exported by Sierra Leone, yielding about USD $400 million. This therefore shows that cocoa and coffee have the potential to become major cash and export crops although production and export as well as quality are still far from pre-war levels, prior to the civil war that raged in Sierra Leone for over 10 years. With the rediscovery of the wild C. stenophylla, efforts are being made by the government of Sierra Leone and funding agencies to promote the domestication of this species as it may serve as a niche market for smallhold farmers.

In terms of climate resilience, C. stenophylla which is endemic to Sierra Leone, Cote D'Ivoire and Guinea stands out amongst the 120 coffee species[12]. Historical references (1834–1929) have indicated that this species has an excellent taste[12] and may be as good as the 'best mocha'[13] and most probably superior to all other discovered coffee species in the world, including C. arabica. However, the age and context have warranted these claims to be caveated and given the fact that sensory praise for this species (universal cupping) has not been undertaken[14]. Additionally, no published sensory information on C. stenophylla has been in existence since the 1920s, probably due to its scarcity in cultivation and rarity in the wild. Ever since its discovery as an edible crop, it has not been in general cultivation since the 1920s[12] and is threatened with extinction in the wild[15] due to agricultural and non-agricultural interventions by humans. Coupled with competition from Robusta coffee whose early progress towards becoming a global commodity coincides with the decline of stenophylla farming[16], poor yield has been given as one of the major reasons why C. stenophylla failed to become established as a major global coffee crop species[16]. Reference to the number of flowers/fruits per node and shoot, C. stenophylla yields are likely to be less than C. arabica and C. canephora, although commercially viable yields are evident[12,14]. For proper management and better exploitation of the available gene pool, knowledge on the pattern and variation for important morpho-agronomic traits is essential[15]. However, phenotypic characterization of the wild C. stenophylla from the hills of Sierra Leone is yet to be undertaken. This study was therefore conducted to assess the extent of genetic variation that exists within collections of wild stenophylla in Sierra Leone. Data were randomly collected on C. stenophylla that were growing in the wild at different locations using the International Plant Genetic Resource Institute (IPGRI)[17] list of descriptors.

-

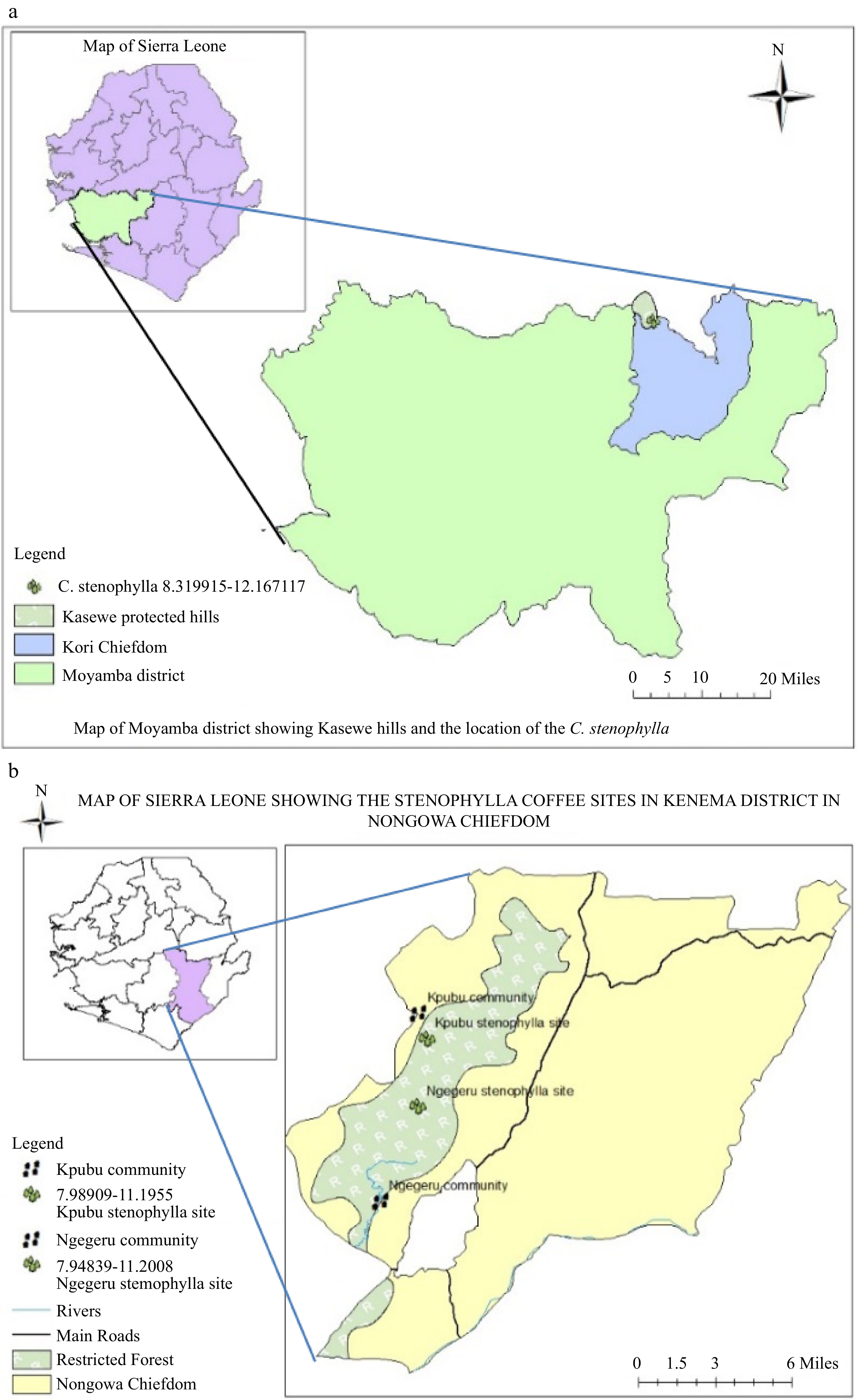

The study was carried out in two key districts (Kenema and Moyamba) in Sierra Leone with notable hills that serve as forest reserves (Fig. 1). Samples from Kenema districts were taken from two communities where C. stenophylla had been discovered in the Kpumbu forest that lies within Latitude 7°59'23.364" N and Longitude –11°11'40.356" W with an altitude of 375 m above sea level and Ngegeru forest which lies within Latitude 7°56'50.634" N and Longitude –11°12'16.818" W with an altitude of 466 m above sea level. Kpumbu and Ngegeru are situated 25 km and 10 km respectively, southwest of Kenema city, the headquarters of the Eastern region. Samples were also taken from the Kasewe hill forest reserve, about 32 km north west of Moyamba town, Southern region to form part of the study site. The Kasewe forest reserve lies within Latitude 8°19'11.694" N and Longitude –12°10'1.62" W with an altitude of 416 m above sea level. The mean annual rainfall of Kambui and Kasewe forest reserves are 2,546 and 2,135 mm respectively, with an average monthly temperature that ranges between 26 and 32 °C from June to October[18]. Both Kasewe and Kambui forests consist of terrain with steep slopes that reach an elevation of between 100–645 m above sea level[19]. Kambui forest has two sections i.e. Kambui north which is about 20,348 ha and Kambui south with land mass of about 880 ha[19]. This study basically focused on Kambui north where the C. stenophylla had been discovered.

Figure 1.

Map of Sierra Leone showing (a) Moyamba and (b) Kenema Districts where C. stenophylla were collected at Kasewe and Kambui hills, respectively.

The vegetation of these reserves is classified as ever-green with six months of continuous rain fall and a complex biodiversity that spans right across the untouched areas. The vegetation in the reserves have been classified as closed consisting of three vegetation types: Albert logged forest (91.0%), farm bush (7.5%) and vine forest (0.7%) as described by Fayiah et al.[19]. Kambui hill forest serves as protection for more than 12 catchments and eight of these catchments currently supply water by gravity to the Kenema City and its environs[20].

Experimental materials

-

A total of 203 C. stenophylla genotypes which included 198 accessions collected from the wild from Kenema and Moyamba districts within notable forest reserves and five standard checks that are maintained at ex-situ field gene bank of the Sierra Leone Agricultural Research Institute (SLARI) at Bambawo substation were used for this study. The study was superimposed on wild C. stenophylla at different stages of growth in varying terrain and standard checks planted in 2021 at SLARI research station.

Experimental design

-

This study was conducted from January to February, 2022 when some seed materials of the wild C. stenophylla were available and the leaves in pretty good shape. Observations were made and samples collected through random selection at each of the aforementioned locations. A total of 173 plants were sampled from the Kambui, while 25 plants were sampled from Kasewe forest reserves and five standard checks at Bambawo substation.

Data collected

-

Data were collected on 13 morphological traits based on coffee descriptors developed by the IPGRI[17] as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Morphological parameters studied and their description as per the IPGRI[17].

# Characters and their descriptive values 1 Growth habit: 1 (open), 2 (intermediate), 3 (compact) 2 Stem habit: 1 (stiff), 2 (flexible) 3 Angle of insertion of primaries: 1 (dropping), 2 (horizontal spreading), 3 (semi-erect) 4 Young leaf tip colour:1 (greenish), 2 (green), 3 (brownish), 4 (reddish brown), 5 (bronzy) 5 Leaf shape: 1 (obovate), 2 (ovate), 3 (elliptic), 4 (lanceolate) 6 Leaf apex shape: 1 (round), 2 (obtuse), 3 (acute), 4 (acuminate), 5 (apiculate), 6 (spatulate) 7 Stipule shape: 1 (round), 2 (ovate), 3 (triangular), 4 (deltate), 5 (trapezium) 8 Fruit shape: 1 (round), 2 (obovate), 3 (ovate), 4 (elliptic), 5 (oblong) 9 Fruit colour: 4 (light red), 5 (red), 6 (dark red) 10 Calyx limb persistence: 0 (not persistent), 1 (persistent) 11 Seed shape: 1 (round), 2 (obovate), 3 (ovate), 4 (elliptic), 5 (oblong), 6 (other) 12 Seed uniformity: 1 (uniform), 2 (mixed) 13 Bean size: 1 (small), 2 (medium), 3 (large) Data analysis

Frequency distribution

-

Frequencies of the various 13 morphological traits were computed using Microsoft XL.

Shannon-Weaver diversity index

-

For each morphological trait assessed, the Shannon-Weaver diversity index (H') was computed using the phenotypic frequencies to assess the overall phenotypic diversity. The number of phenotypic classes used in the Shannon-Weaver Diversity index (H') were normalized by the maximum value (log n) in each case as described by Henninck & Zeven[21] and computed as a measure of the diversity of the traits used. For an 'n' class trait, the observed normalized H' was obtained using the formula:

H' = –∑ [ (pi) × ln (pi)]

Where H' = Shannon-Weaver Diversity index,

Pi = the relative abundance of each trait = n1/N

ln (pi) = the natural log of relative abundance = ln (n1/N)

Therefore,

H' = –∑ [(n1/N) ln (n1/N)]

Cluster analysis and principal component analysis

-

To further validate the results obtained from frequency distribution and Shannon-Weaver diversity index, the data were transformed and subjected to cluster analysis for the construction of dendrogram and principal component analysis.

-

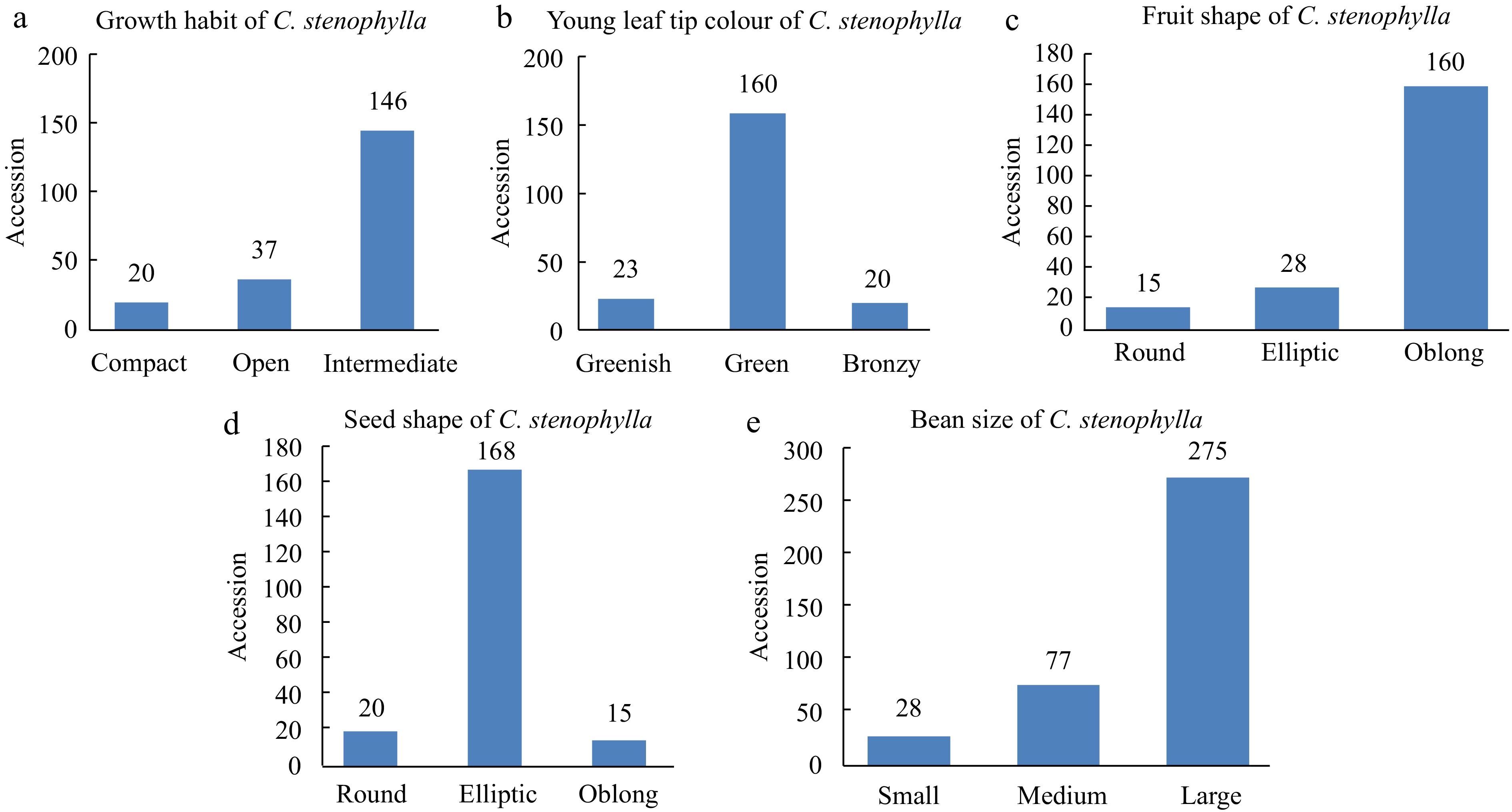

The use of this descriptor unraveled a broad range of morphological variations among C. stenophylla (Fig. 2). For instance, about 72.0% of the sampled plants had intermediate growth habit while only about 10.0% had compact growth habit. This gives an indication that scanning of the Kambui and Kasewe hills for C. stenophylla requires a great deal of effort if more colonies are to be discovered. Similarly, variations existed in flush colour, fruit shape, seed shape and even in bean size. The existence of these variations may be useful in the development of new lines of C. stenophylla.

Figure 2.

Bar graphs showing (a) growth habit, (b) young leaf colour, (c) fruit shape, (d) seed shape and (e) bean size (seeds were collected from 203 sampled genotypes) of C. stenophylla .

Growth habit, nature of stem and angle of insertion of primaries on main stem

-

The result shows considerable variation in growth habit of C. stenophylla in the wild with 71.9%; 18.2% and 9.9% of intermediate, open and compact growth habit that span across the study sites. The wild nature of C. stenophylla justifies the presence of all three growth habits probably due to mutations and inbreeding over the years.

In the same vein, two types of stem nature were observed at all locations with 63.0% of stems being flexible while 37.0% were stiff (Table 2, Fig. 3). This result corroborates the findings of Weldemichael[22] who also reported variations in the growth habit and nature of stem of Ethiopian coffee (C. arabica) accessions. The presence of C. stenophylla with large stem of girth (≥ 20 cm) is an indication that this coffee has been in existence for ages.

Table 2. Percentage of phenotypic class values for 13 morphological traits of 203 C. stenophylla

S/N Phenotypic class % 1 Growth habit Compact 9.9 Open 18.2 Intermediate 71.9 2 Stem habit Stiff 37.0 Flexible 63.0 3 Angle of lateral insertion

of primariesDropping 7.4 Horizontal spreading 59.1 Semi-erect 33.5 4 Young leaf tip colour Greenish 11.3 Green 78.8 Bronzy 9.9 5 Leaf shape Obovate 0.5 Ovate 3.5 Elliptic 6.9 Lanceolate 89.2 6 Leaf apex shape Acute 99.0 Acuminate 1.0 7 Stipulate shape Ovate 3.5 Triangular 87.2 Deltate 9.3 8 Fruit shape Round 7.4 Oblong 78.8 Elliptic 13.8 9 Ripe fruit colour Mauve 100 10 Calyx limb persistence Not Persistent 100 11 Seed shape Round 9.8 Elliptic 82.8 Oblong 7.4 12 Seed uniformity Mixed 100 13 Bean size Small 7.4 Medium 20.2 Large 72.4 Similarly, angle of insertion of primaries of the 203 sampled C. stenophylla showed variations in the following proportions; 59.1%, 33.5% and 7.4% had horizontal spreading, semi-erect and dropping primaries, respectively. The findings of this study on coffee accessions having stiff stem habit is in agreement with the report by Masreshaw[23] although horizontal spreading type of angle of insertion dominates the case of C. stenophylla (Table 2).

Leaf morphology

-

Based on the IPGRI[17] coffee morphological descriptor, the 203 C. stenophylla from the wild were classified into three key groups with respect to young leaf tip colour (Table 2). The result shows that 78.8% of the young leaf tip colour were green while 11.3% were greenish and 9.9% were bronzy (Table 2, Fig. 4). This result indicates that C. stenophylla exhibit variations in the leaf morphology drawn from different locations.

Figure 4.

Progressive stages of development of C. stenophylla. (a) Match-stick stage i.e. 45 d from date of sowing to germination; (b) Butterfly or two leaf stage i.e. 14 d after germination; (c) 28 d after germination; (d) 35 d after germination; (e) 49 d after germination; (f) 58 d after germination; (g) 63 d after germination; (h) 84 d after germination; and (i) 12 months after germination.

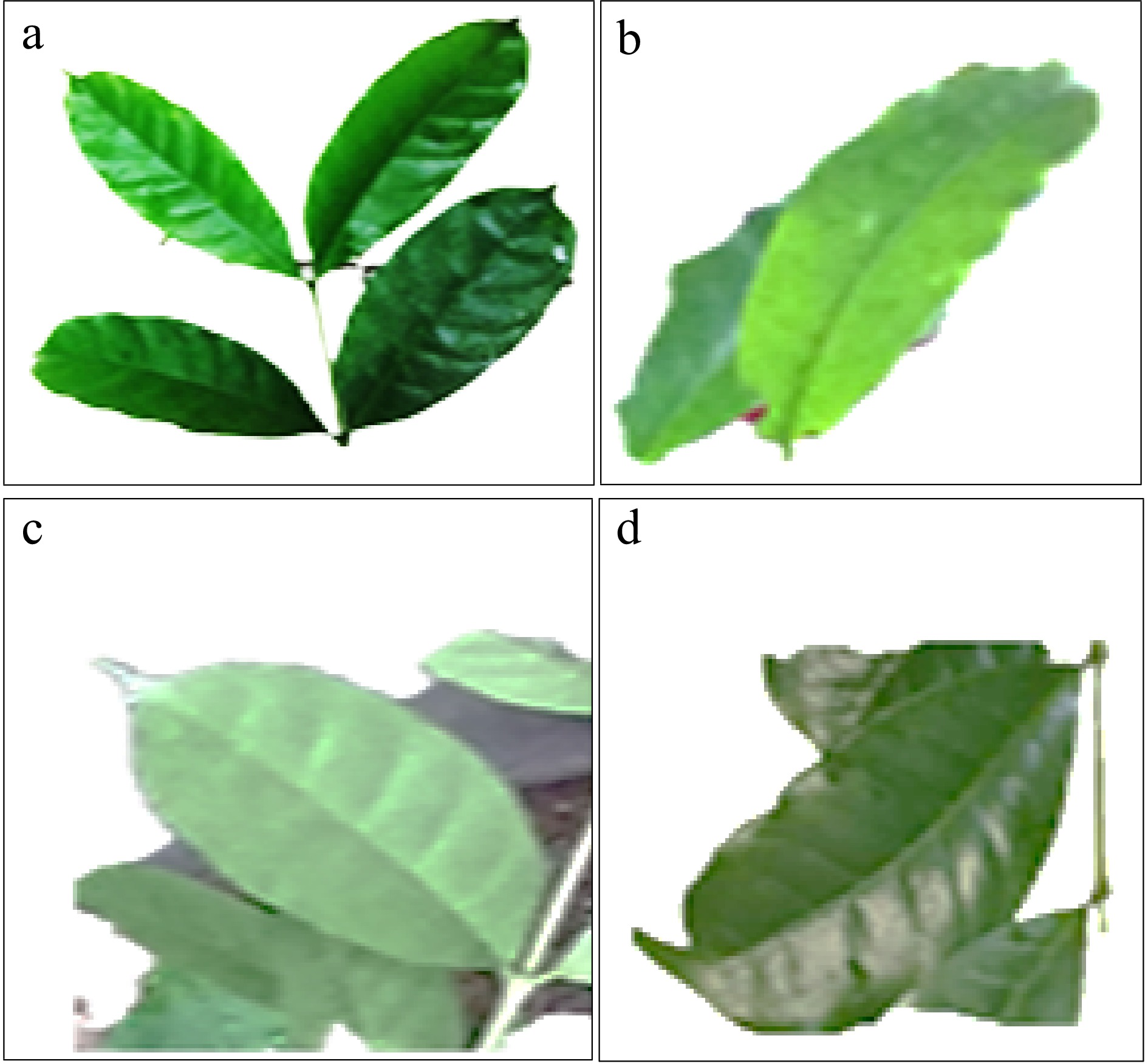

Unlike C. arabica, where its leaf shape is dominated by elliptic type of shape[22], the leaf shape of C. stenophylla is dominated by lanceolate shape (89.2%). Few of the trees of C. stenophylla had elliptic, ovate and obovate shapes in the following proportions; 6.9%, 3.5% and 0.5% respectively (Fig. 5). From a population of 203 trees, the majority of the trees (99.0%) had acute leaf apex shape while the remaining 1.0% had acuminate tip shape. The findings of this study however do not support the outcome of previous studies[22,24] who reported that the majority of coffee accessions are made up of acuminate type of leaf tip shape. In line with the findings of this study with regards to leaf shape and leaf apex shape, other reasearchers reported the existence of variabilities in leaf morphology of coffee[25,27].

Figure 5.

Leaf shape of Coffea stenophylla showing (a) lanceolate, (b) elliptic, (c) ovate and (d) obovate types.

Morphological characteristics of C. stenophylla fruit

-

Like other coffee species, the colour of immature C. stenophylla is green. However, the mature or ripe fruit colour of C. stenophylla did not fall within the phenotypic class of light red, red and dark red as stated in the International Plant Genetic Resource Institutes[17] list of coffee descriptors, giving an indication that the C. stenophylla is a rare species of coffee that had not been explored or noticed as at that time. According to the results of this study, the colour of C. stenophylla is mauve (100%) at maturity and becomes blackened when overripe (Table 2). In this reporting period, the distinct mauve colour may be true only for C. stenophylla when it is ripe (Fig. 6). This result contradicts the findings of others[22,24] who found three distinct fruit colour of coffee using the International Plant Genetic Resource Institutes[17] descriptor.

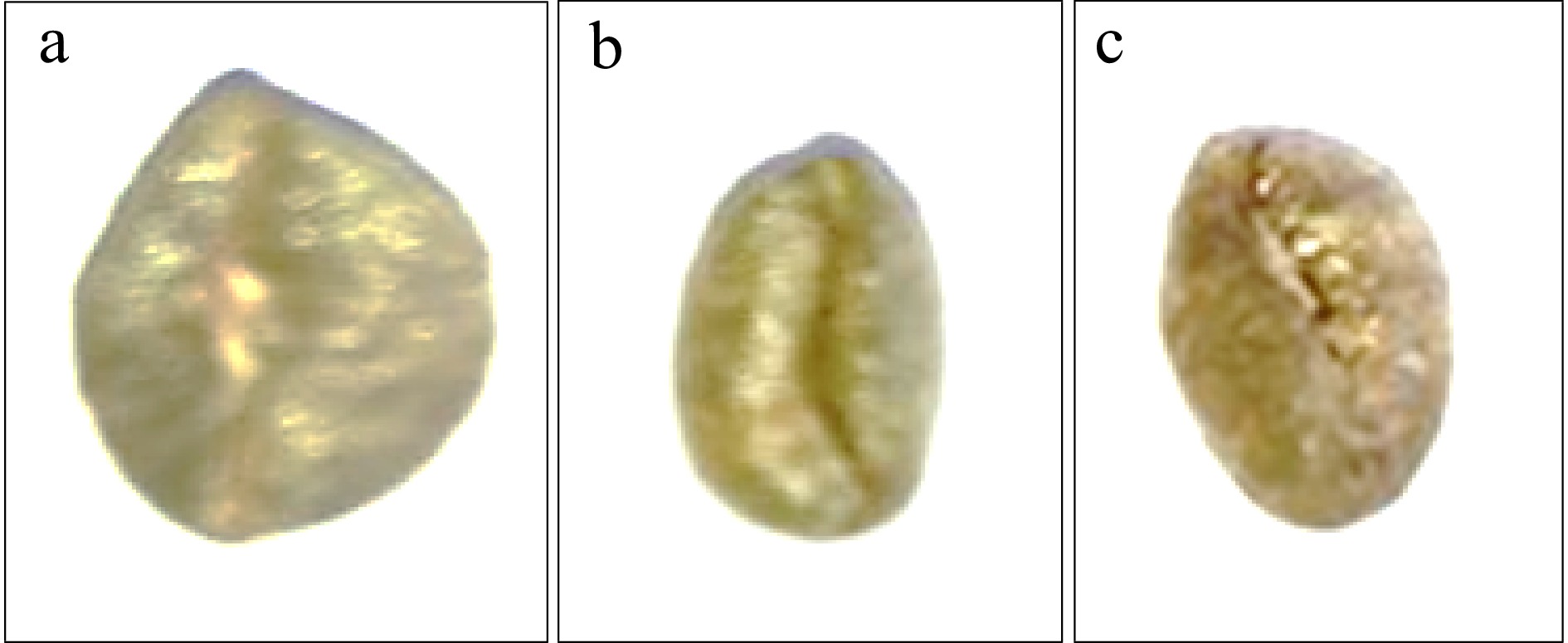

Figure 6.

Seed shapes of Coffea stenophylla showing (a) oblong, (b) elliptic and (c) slightly rounded.

Based on the results, there were considerable variabilities in terms of fruit shape with 78.8% being oblong, 13.8% being elliptic and 7.4% being type. The present results partly contradict the findings of others[22,23] who had reported lager proportion of roundish fruit shape and red fruit color among coffee accessions collected from Yayu forest of Ethiopia. Unlike the C. arabica whose calyx limb were observed to be persistent[22], the calyx limb of C. stenophylla however, were observed not to be persistent (100%) which is an indication that there is no variability in terms of the persistence of calyx.

The majority of the seeds of C. stenophylla collected were elliptic (82.8%) in shape while the remaining 9.8% and 7.4%, respectively, were roundish and oblong in shape. Although Weldemichael[22] reported fruit shapes of coffee to be mainly oblong and of two distinct classes, the results of this study proved otherwise with three distinct morphological seed shapes indicating higher variability in seed shape of C. stenophylla.

Minor variation was observed in the uniformity of coffee seeds with the largest proportion (90.6%) being uniform while a small proportion of it were mixed (9.4%) which is in agreement with others[22−24]. Similarly, the bean size of C. stenophylla were classified into three distinct groups with 72.4% of the beans being large with average length of 13 cm and average width of 8 cm; 20.2% of medium size with average length of 10 cm and average width of 6 cm while 7.4% being of smaller size with average length of 7 cm and average width of 3 cm. This result disagrees with the findings of others[25−27] who reported higher proportion of medium sized coffee beans among C. canephora genotypes indicating that C. stenophylla with such bean sizes and better cup quality is a special and different type of coffee with huge investment potential.

Shannon-Weaver diversity index

-

The Shannon-Weaver diversity index (H') was used to estimate the phenotypic diversity of the 13 morphological characters and the maximum value was normalized in each case (Table 3). By estimation and interpretation of the results, low (H') (nearer to zero than to one) indicates a low level of diversity and unevenness in the distribution and vice versa[21].

Table 3. Estimates of Shannon-Weaver diversity index (H') for 13 morphological traits of 203 C. stenophylla.

Phenotypic character Shannon-Weaver diversity index (H') Growth habit 0.78 Stem habit 0.66 Angle of insertion 0.87 Young leaf colour 0.66 Leaf shape 0.43 Leaf apex shape 0.06 Stipule shape 0.46 Fruit shape 0.65 Fruit colour 0 Calyx limb persistence 0 Seed shape 0.58 Seed Uniformity 0.31 Bean size 0.75 Following the computation of the H', the results clearly indicates large variations among the 203 C. stenophylla samples for the observed 13 morphological traits which ranges from 0 for both fruit colour and calyx limb persistence to 0.87 for angle of insertion of primary branches on the main stem. This result is partly in agreement with that obtained by Weldemichael[22] who reported large variabilities (H' = 1.08) for angle of insertion of primary branches on the main stem of coffee.

Among the 13 morphological traits assessed, angle of insertion of primary branches on main stem (H' = 0.87), growth habit (H' = 0.78), bean size (H' = 0.75), young leaf colour (H' = 0.66), stem habit (H' = 0.66) and fruit shape (H' = 0.65) exhibited high level of diversity and evenness while seed shape (H' = 0.58), stipulate shape (H' = 0.46), leaf shape (H' = 0.43) and seed uniformity (H' = 0.31) showed medium diversity. Leaf apex shape (H' = 0.06) and calyx limb persistence (H' = 0) showed virtually no diversity (Table 3). Variabilities (high H') have been reported by Yigzaw[28] in C. arabica for nine morphological traits, which partly corroborate with this study in terms of angle of insertion of primaries on main stem, young leaf colour, stem habit and growth habit but low H' for stipule shape, seed uniformity and seed shape. Although Yigzaw[28] reported low variability for bean size, this study found high H' = 0.75 but low H’ for leaf shape and leaf apex shape probably due to varying species, sample sizes and geographical differences. Contrasting results have been obtained for diversity among coffee accessions by some researchers[25]. High level of diversity (H' > 0.5) was reported by Olika[25] for growth habit, stipule shape, branching habit, angle of insertion of primaries, fruit shape and stem habit, but later contradicted the findings by reporting high level of diversity for leaf shape and leaf apex shape, and low level of diversity (H’ < 0.5) for young leaf colour and seed shape. The results obtained by various authors could be attributed to either differences in environmental factors or genetic diversity of coffee species.

Principal component and cluster analysis of phenotypic diversity of C. stenophylla collected from the wild

-

Improvement of parental lines require the effective and efficient utilization of available germplasm pool and has always served as the prerequisite in coffee breeding programs. Therefore, the phenotypic traits must be correctly assessed and categorized based on either individual or group performance. To further evaluate the phenotypic diversity of the 203 samples of C. stenophylla, the data were subjected to principal component analysis (PCA) and cluster analysis (CA). The average relationship and Euclidean distance were used in the hierarchical cluster analysis for the samples under investigation.

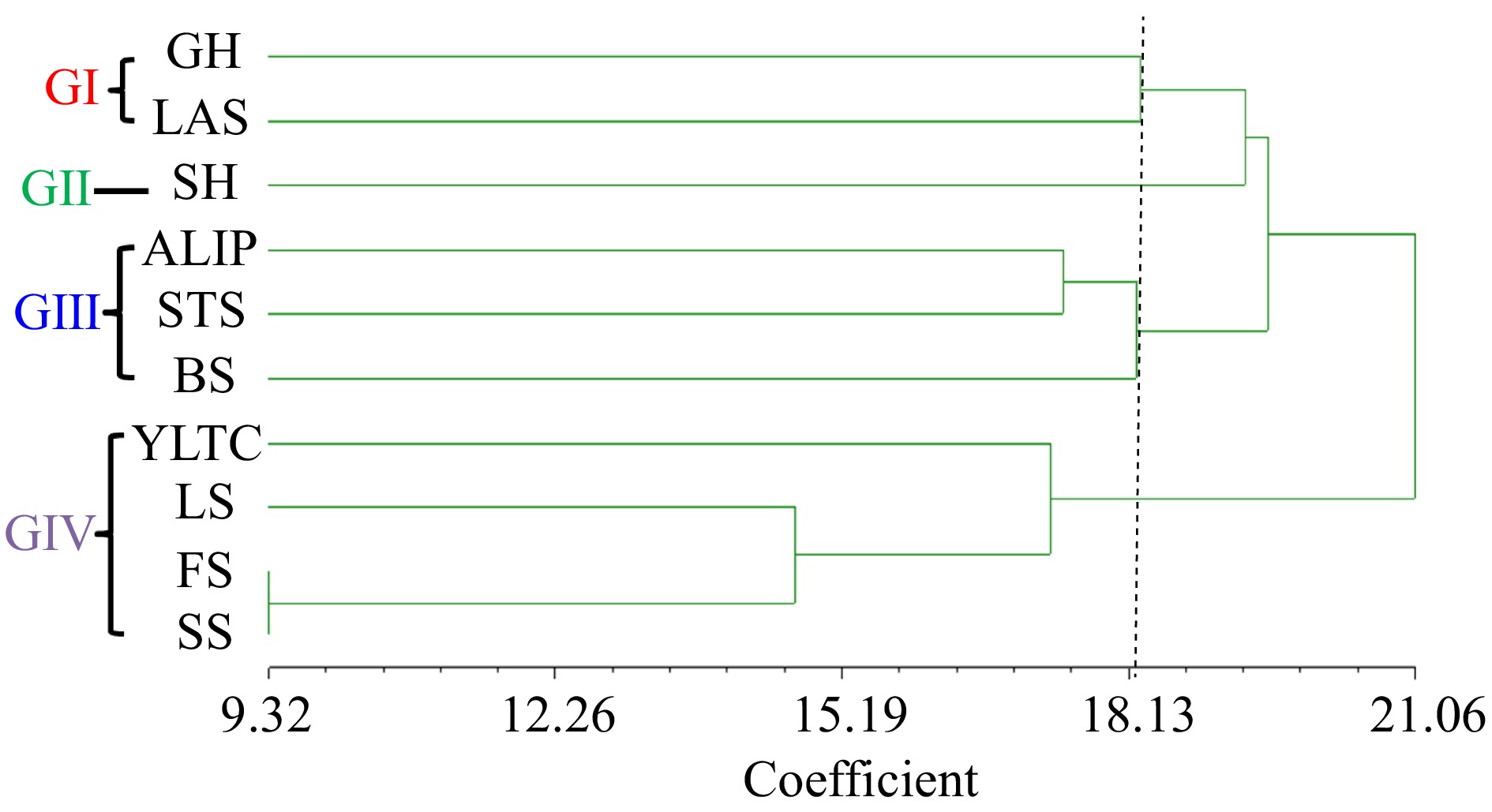

The unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) dendrogram was formed based on the 13 morphological parameters under study. The wild C. stenophylla were clustered into four major groups at 18.13 coefficient level (Fig. 7), which showed morphologically distinct variations among traits. The analysis revealed that cluster I unified two parent subclusters (growth habit and leaf apex shape) while cluster II had one subcluster (stem habit). On the other hand, clusters III and IV each showed three subclusters (angle of lateral insertion of primaries, stipule shape and bean size); (young leaf tip colour, leaf shape and fruit character), respectively.

Figure 7.

Dendrogram of traits of C. stenophylla collected from Kasewe and Kambui forest reserves. GH = Growth Habit, SH = Stem Habit, ALIP = Angle of Lateral Insertion of Primaries, LS = Leaf Shape, YLTC = Young Leaf Tip Colour, LAS = Leaf Apex Shape, STS = Stipule Shape, FS = Fruit Shape, CLP = Calyx Limb Persistence, SS = Seed Shape, SU = Seed Uniformity, BS = Bean Size.

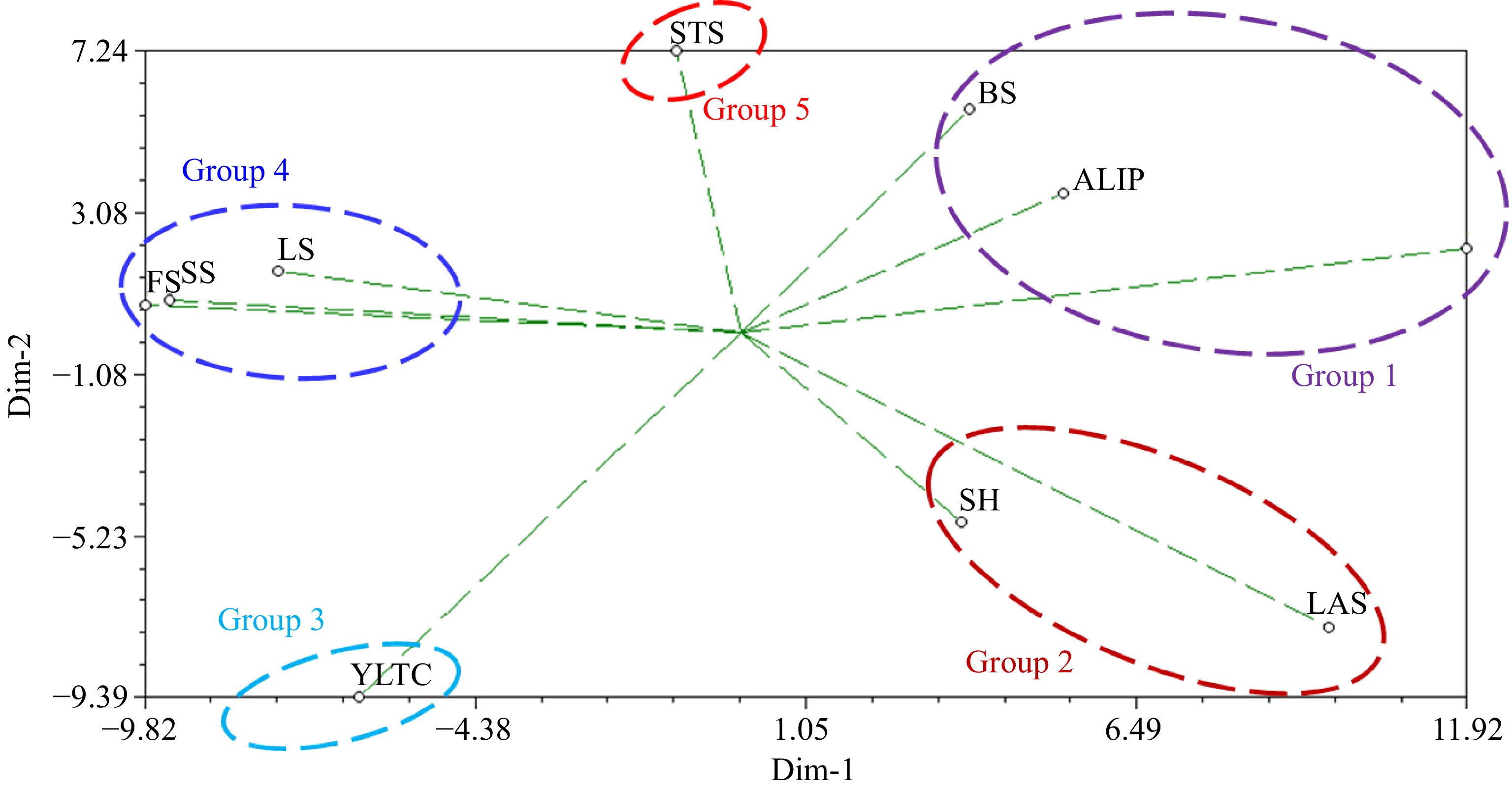

As a way of validating the cluster analysis, a two-dimensional plot of principal integral component analysis which gives an indication of parental origins of C. stenophylla, was constructed and showed five groups based on the levels of phenotypic diversity. Young leaf tip colour and leaf apex shape emerged as the preferable traits that distinguishes C. stenophylla from other coffee species (Fig. 8). Angle of lateral insertion of primaries, bean size and growth habit were categorized as one group probably due to environmental effects on wild C. stenophylla.

Figure 8.

Two-dimensional plot of principal integral component analysis showing parental origins of C. stenophylla. GH = Growth Habit, SH = Stem Habit, ALIP = Angle of Lateral Insertion of Primaries, LS = Leaf Shape, YLTC = Young Leaf Tip Colour, LAS = Leaf Apex Shape, STS = Stipule Shape, FS = Fruit Shape, CLP = Calyx Limb Persistence, SS = Seed Shape, SU = Seed Uniformity, BS = Bean Size.

-

This study unraveled the existence of phenotypic diversity among the C. stenophylla from Kpumbu, Ngegeru and Kasewe using 13 morphological characters that were put forward by the International Plant Genetic Resource Institute[17]. This shows that coffee improvement programs for this special type of coffee could result in domestication from the wild, hybridization and selection of high yielding materials. In conclusion, the observed variabilities should be exploited in order to develop hybrids based on the desired traits particularly improvement in the yield of C. stenophylla. It is also essential that the morphological characteristics observed be confirmed through genetic fingerprinting.

The authors acknowledge the Director General of the Sierra Leone Agricultural Research Institute (SLARI), the minister and deputy minister of Agriculture and Forestry, Drs. Abubakarr Karim and Theresa Tenneh Dick, respectively for their immense support towards this study. Furthermore, we acknowledge the effort of Dr. Senesie Swaray, Messrs. Momoh Lahai, Alie Sartie, Emmanuel Lasimoh, Titus J. Musa, John Sandy, Lamin Massaquoi and Dauda Mattia who in one way another made this work a success.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2023 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Lahai PM, Aikpokpodion PO, Lahai MT, Bah MA, Gboku MLG. 2023. Phenotypic diversity of wild Sierra Leonean coffee (Coffea stenophylla) collected from Kenema and Moyamba districts. Beverage Plant Research 3:12 doi: 10.48130/BPR-2023-0012

Phenotypic diversity of wild Sierra Leonean coffee (Coffea stenophylla) collected from Kenema and Moyamba districts

- Received: 29 November 2022

- Revised: 26 April 2023

- Accepted: 06 May 2023

- Published online: 29 May 2023

Abstract: Coffee is a major cash and export crop in Sierra Leone and is mainly cultivated in southern and eastern provinces. Kenema, Kailahun, Moyamba, Bo, Pujehun and Kono are major coffee growing districts in the country. This study looks at the extent of phenotypic diversity of the rare and wild Coffea stenophylla in Kenema and Moyamba districts. The Shannon-Weaver diversity index (H') revealed variations among the samples for the observed 13 morphological traits which ranges from 0 for both fruit colour and calyx limb persistence to 0.87 for angle of insertion of primary branches on the main stem. Among the 13 morphological traits assessed, angle of insertion of primary branches on main stem (0.87), growth habit (0.78), bean size (0.75), young leaf colour (0.66), stem habit (0.66) and fruit shape (0.65) exhibited high level of diversity while seed shape (0.58), stipule shape (0.46), leaf shape (0.43), seed uniformity (0.31) and leaf apex shape (0.06) showed low levels of diversity. This is the first report of phenotypic diversity of C. stenophylla in Sierra Leone and the study thus unraveled existence of diversity among samples. It is recommended that these observed variabilities be exploited in order to develop better accessions that are high yielding yet maintain the same taste. Additionally, genetic fingerprinting needs to be applied to provide a complementary assessment of the observed phenotypic diversity.

-

Key words:

- Phenotypic /

- Diversity /

- Traits /

- Stenophylla and Accessions.