-

Pteridophytes (ferns) comprise about 10,000 to 12,000 species distributed worldwide[1], which are widely used as ornamental plants due to the beauty of their foliage. The two main qualities that make them delicate and elegant are the fine subdivision of their leaves, called fronds, and their very soft texture[2].

In Argentina, the research projects on Pteridophytes are focused on their biodiversity and conservation, and include objectives such as the updating of their nomenclature and distribution, the elaboration of the Red List of Argentina, and the conservation of rare, endemic or threatened species as well as of other species of systematic, biogeographical or ornamental interest[3].

Recently, a study performed a preliminary characterization of Polystichum plicatum, a fern native to Argentine Patagonia, with a view to its use as cut foliage[4]. However, information on the cultivation of native ferns with ornamental potential for landscape uses, such as potted plants or cut foliage, remains scarce.

Trismeria trifoliata (L.) Diels is a tropical fern, whose distribution extends from Mexico and the Caribbean Islands to the temperate regions of South America and in a wide range of altitude distribution, from sea level to 2000 masl. It grows preferentially in swampy areas with low herbaceous vegetation, river banks and open fields, completely exposed to sunlight and is resistant to long drying periods[5]. In Argentina, T. trifoliata can be found naturally in the northeast, northwest and center of the country[6, 7].

From a botanical point of view, this species is a perennial herb, with a short rhizome, agglomerated or rarely separated fronds (0.5 to 1 m long), and pinnate to bipinnate blades[8,9]. At certain times of the year, it presents fertile fronds with the top of the pinnae somewhat contracted and covered by a farinaceous indument on the dorsal surface. These fertile fronds are usually larger than sterile ones, producing a slight leaf dimorphism. The farinaceous exudates are composed of different types of flavonoids, which, in some specimens, provide a whitish or yellowish coloration. Although not all researchers agree, the phytochemical characteristics of complex flavonoids would effectively serve for taxonomic recognition, a fact that becomes relevant in Pteridophytes because of their high percentage of natural hybridization[6].

Morphological and palynologic studies were conducted on herbarium material of Trismeria sp. to clarify aspects related to its systematic characterization studies[8]. However, to our knowledge, no studies on its anatomical structures in fresh material have yet been published. Obtaining these data would allow building a solid basis for the interpretation of the ecophysiological variables associated with the cultivation of this species, to achieve its domestication for commercial purposes. It would also facilitate the understanding of its post-harvest responses in its introduction as cut foliage, as reported in Rosa × hybrida for cut flower[10].

Thus, the aim of this study was to assess various morpho-anatomical aspects of Trismeria trifoliata, from fresh green material, using plant histology techniques. The results obtained will allow analyzing its behavior in cultivation as well as at post-harvest and its potential use as cut foliage.

-

Trismeria trifoliata specimens were collected in the qom Potae Napocna Navogoh 'La primavera' community, Laguna Blanca, Formosa, Argentina (−25°6' S, −58°16' W) and subsequently grown for one year in a greenhouse belonging to the Chair of Floriculture of the School of Agricultural Sciences of the University of Buenos Aires, located in Buenos Aires city (34°35' S and 58°29' W, 25 masl). The plants were arranged in individual 8-L containers at a rate of one plant per container, with a substrate mixture of peat and perlite in a 1:1 ratio, and grown under aluminized shade mesh (50%). Automated irrigation was applied by means of a drip system with spaghetti tubing (flow rate of 2 L·h−1, one per container, and frequency of 10 min·d−1).

Samples of fresh material were extracted and used to prepare histological preparations at the Botany Laboratory of the Chair of General Botany of the School of Agricultural Sciences of the University of Buenos Aires (Argentina). For the observation of the epidermis, stomata and sporangia, fresh leaves were diaphanized and mounted in gelatin-glycerin[11]. In the case of the cross-sections of the leaf and the leaf rachis, the material was fixed in formaldehyde alcohol acetic solution (FAA) and histological preparations were made following the paraffin inclusion method[12]. Serial cuts of 10−12 mm thick were obtained by the use of a Minot rotary microtome, dyed with double safranin-fast-green coloration and mounted in Canada balsam. Finally, histological preparations were observed with a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Axioplan) and photographed with Zeiss AxioCam ERc 5s software (Jena, Germany).

-

Pteridophytes are a taxonomic group with a high percentage of natural hybridization. On many occasions, this leads to misinterpretations of families, genera and even species. The importance of anatomical and morphological studies were highlighted, especially of leaf anatomy, as a source of new characters for the correct identification of species[13].

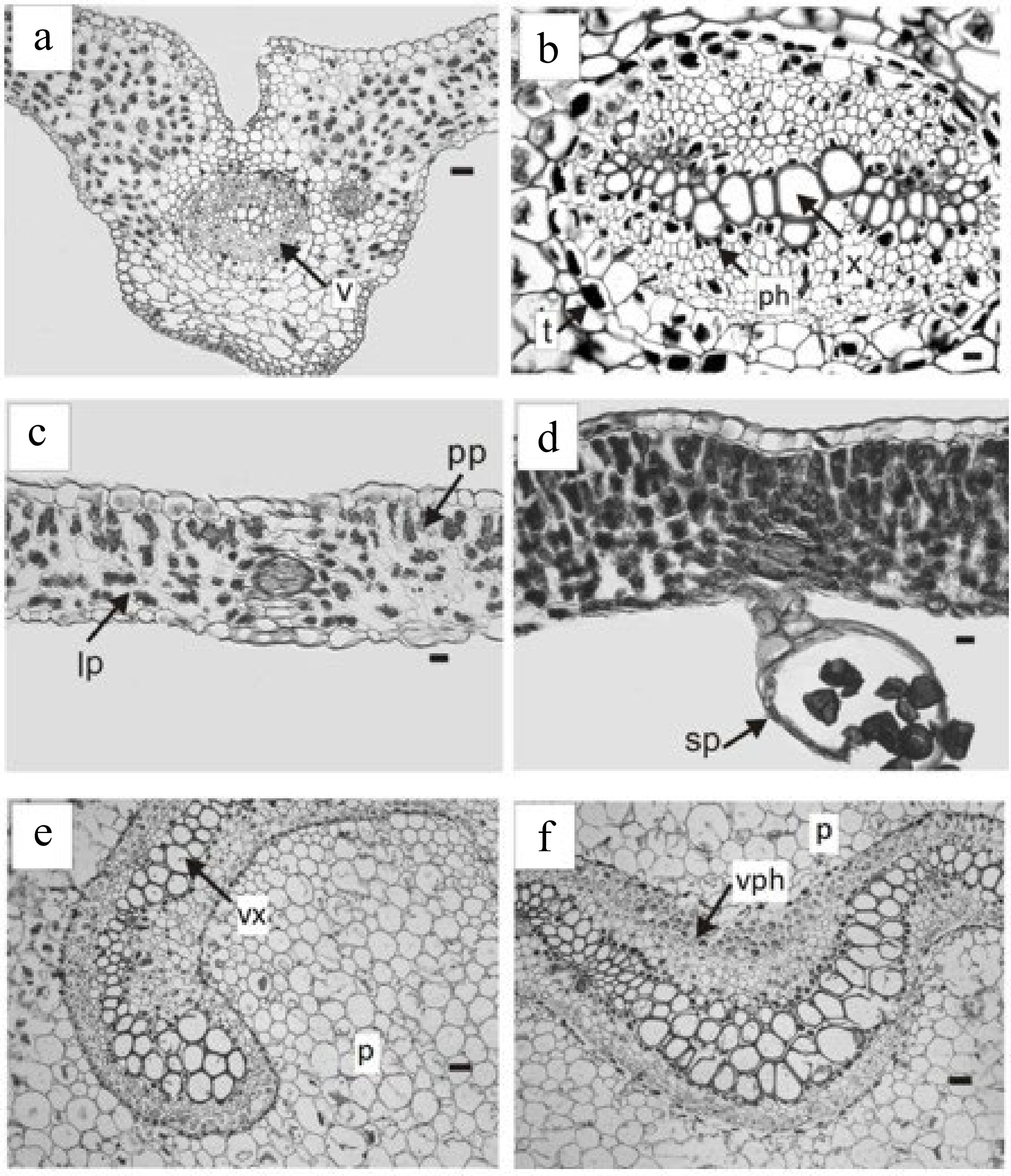

The vascular bundles of the blade have a main nerve and numerous secondary dichotomous ones, with the central nerve locked (Fig. 1a & b) and the secondary ones semi-locked (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

Trismeria trifoliata. (a) Cross-section of the main middle nerve of the central leaflet and (b) detail of the vascular bundle. (c) & (d) cross-sections of the intercostal areas. (d) Detail of the sporangia on the lower face of the leaflet. (e) & (f), cross-sections of the petiole with the phloem and xylem presenting a central curvature. ph, phloem; p, parenchyma; pp, palisade parenchyma; lp, lacunose parenchyma; sp, sporangia; t, tannins; v, vascular bundle; vph, vessel phloem; vx, vessel xylem. Scales: (a), (e), (f) = 180 μm, (b) = 45 μm, (c) & (d) = 100 μm.

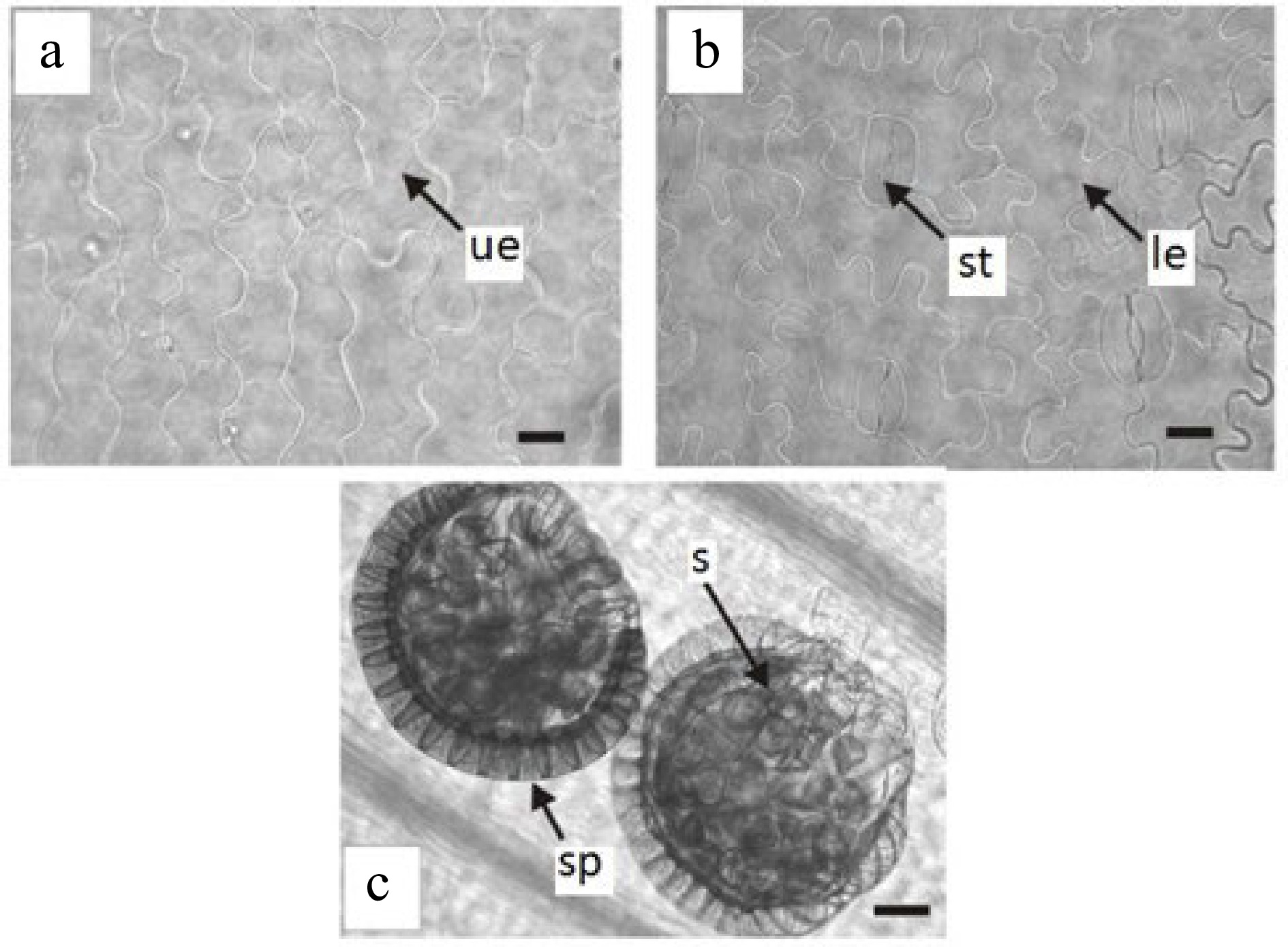

Trismeria trifoliata has a dorsiventral leaf structure and, in some sectors of the leaf wing, it may have subisolateral structure (Fig. 1c & d). The cuticle, which is 1 to 2 mm thick, is smooth to slightly striated. The epidermis has a single layer, which is thicker on the adaxial face than on the abaxial face. The epidermal cells of the upper face of the leaf are elongated with sinuous contours, whereas those of the lower face are shorter and very sinuous (Fig. 2a & b). Stomata are present only on the abaxial face, surrounded by two to three subsidiary cells (Fig. 2b). The palisade parenchyma consists of two to four layers of cells, whereas the lacunar parenchyma consists of three to four layers, and, in some sectors, is replaced by somewhat irregular palisade parenchyma (Fig. 1c & d). The margin of the leaf is crenate-dentate.

Figure 2.

Epidermis in surface view of Trismeria trifoliata. (a) and (b) upper and lower epidermis of the central leaflet, respectively. (c) view of sporangia on the lower face of the central leaflet. le, lower epidermis; s, spores; sp, sporangia; st, stomata; ue, upper epidermis. Scales: (a) and (b) = 45 μm and (c) = 100 μm.

The leaf rachis presents a curved vascular bundle without a protoxylem lacuna (Fig. 1e & f). The arrangement and characteristics of the vascular bundle of the rachis coincide with that observed in previous studies in the leaf petiole[8]. The rachis is crossed by a solenostele, without nerve strands, which opens to originate successive leaf traces. These consist of two vascular strips separated from each other before separating from stelar. However, the origin of the leaf traces appears to depend mainly on the size and degree of the curvature of the vascular system of the rachis[14].

Regarding sporangia, in agreement with previous studies[8,14], these are located on the lower face of the leaf along the main vein, and they are unprotected (Fig. 2c). They are pedunculated and have a vertical ring composed of strongly thickened radial and internal walls and the spores are tetrahedral (Fig. 1d).

The samples studied showed the presence of mucilage-tannin idioblasts (Fig. 1b), sparsely distributed in the mesophyll and with abundant spheroidal druses associated with vascular bundles. According to numerous reports, the presence of mucilage-tannin idioblasts is closely related to physiological responses to drought[15−17].

The existence of idioblasts in hypodermic tissue and mesophyll in eight species of Orchids (Oncidium abortivum, Epidendrum excisum, Rodriguezia lehmannii, Hirtzia escobarii, Elleanthus oliganthus, Elleanthus purpureus and Pleurothallis cordifolia) would be related to water accumulation capacity and mechanical support functions that prevent tissue collapse during drought periods[18]. Similar functions have been described in a study of the drought response of epiphytic Orchid species that develop in the dry forests of the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico[17].

Similarly, the presence of mucilage and druses found in photosynthetic tissue from ten taxa of the genus Opuntia, obtained from the dry Chilean mediterranean region, has been interpreted as an adaptation to limited rainfall conditions[19]. It is therefore possible to speculate that the presence of mucilage-tannin idioblasts with druses found in T. trifoliata would be related to their ability to withstand prolonged periods of drought and exposure to full sunlight[6]. Another Pteridaceae, Adiantum petiolatum, which develops naturally in dry soils near rocky areas, also shows idioblasts forming lines on both sides of the leaf ribs, on the upper face of the fronds[20, 21].

In the present study, stomatal density (SD) showed significant differences between juvenile fronds (without spores) and fertile adult fronds (with spores), with mean values of 73.3 and 119.8 stomata·mm−2, respectively. However, the Stomatal Index (SI; number of stomata/number of epidermal cells) presented no significant differences (p < 0.05), resulting in mean values of 0.33 (juvenile fronds) and 0.40 (fertile adult fronds). The SI here found in fertile adult fronds was very similar to that found in specimens of Blechnum chilense, a fern that grows spontaneously in the Puyehue National Park, located in the western foothills of the Andes mountain range in the southern center of Chile[22]. Blechnum chilense can be found in a wide range of light and humidity conditions, from open spaces with high exposure to solar radiation to sites with levels of radiation typical of the understory (< 3 of 5% of canopy opening)[23]. On the other hand, the SD recorded in T. trifoliata was lower and the SI was greater than those found in the fronds of Rumohra adiantiformis (SD = 145 stomata·mm−2; SI = 0.4) in a study performed under similar growing conditions[24].

The mean length of stomata showed no significant differences between juvenile and fertile adult fronds, with values of 38.8 and 36.3 µm respectively[25], suggested that the stomatal size would be internally regulated and thus depend mainly on the species. The SD and SI, on the other hand, are adjusted by the detection of environmental signals, such as light and CO2, in both expanded and newly formed leaves[26]. Therefore, considering that, in the present study, the environmental variables were homogeneous, the SD and SI values found in juvenile and adult juvenile fronds of T. trifoliata are consistent. However, plants of the same species grown in the sun or shade could adjust their stomatal characteristics accordingly[22].

In the shade, plants maintain very low gas exchange rates to minimize water loss when light does not allow high C gains[27]. In ferns adapted to different lighting environments, differences in gas exchange properties could be partially explained by the structural characteristics of the leaves, especially by the frequency and size of stomata[22].

The difficulty of ferns to achieve efficient control of leaf hydraulic conductance and stomatal closure would be due to the characteristics of the evolutionary past of ferns[28−30], especially when compared with Angiosperms[31, 32]. Thus, both stomatal density and stomatal size can be key traits in controlling the leaf physiology of ferns, in which stomatal closure is not effectively achieved[22].

Also, the proportion of stomata in relation to the number of epidermal cells, measured through the SI, allows having a notion of the regulation of the gas exchange at the leaf level[33] and reflects the relative investment in stomata by each epidermal cell on a given leaf[34], under a given growth condition. A higher SI and stomach size could lead to higher rates of gas exchange[33−35] given the larger surface available per unit of leaf area[22].

In ferns adapted to different lighting environments, as is the case of T. trifoliata, the gas exchange properties could be partially explained by the structural characteristics of its leaves, especially by the frequency and size of stomata[22]. Thus, these morpho-anatomical parameters are critical aspects to consider when it is desired to evaluate the potential C gains of a species that is being considered as a commercial crop, as well as when it is necessary to evaluate the impact of these parameters on both the post-harvest survival of foliage and the preservation of its ornamental characteristics.

In addition, having a more precise detail of the leaf morpho-anatomy provides essential information for the systematic characterization of a species under cultivation, a fact especially important in plants with high rates of natural hybridization, such as T. trifoliata.

The results of the present study lay the foundations for future research for the clarification of biochemical and physiological issues to assess the introduction of T. trifoliata as a commercial crop of native plants intended for ornamental foliage.

This work was supported by UBACyT project and GET QOM project.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2023 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

González M, Díaz G, Mantese A, Mascarini L, Lorenzo GA. 2023. Morpho-anatomical features of the fronds of the native fern Trismeria trifoliata for use as ornamental foliage. Technology in Horticulture 3:18 doi: 10.48130/TIH-2023-0018

Morpho-anatomical features of the fronds of the native fern Trismeria trifoliata for use as ornamental foliage

- Received: 25 May 2023

- Accepted: 17 July 2023

- Published online: 08 October 2023

Abstract: Trismeria trifoliata is a perennial fern native to Argentina, which has a short rhizome, agglomerated fronds, pinnate or bipinnate blades with radiated arrangement, leaf dimorphism, and great ornamental potential. The aim of the present study was to assess various morpho-anatomical aspects of T. trifoliata, using plant histology techniques to deliver information about cultivation and postharvest and its potential use as cut foliage. Plants were collected from natural areas and cultivated in a greenhouse, in individual 8-L containers, with drip irrigation. Preparations of leaves and rachis were made from extracted fresh material and then observed under a fluorescence microscope. The morpho-anatomical features of primary interest included the presence of mucilage-tannin idioblasts, sparsely distributed in the mesophyll and with abundant spheroidal druses associated with vascular bundles. The presence of these idioblasts is closely related to physiological responses to drought. Stomatal density showed significant differences between juvenile fronds (without spores) and fertile adult fronds (with spores), with mean values of 73.3 and 119.8 stomata·mm−2, respectively. This may explain the difference in behavior of these fronds post-harvest and define the harvest point. Knowledge on the leaf morpho-anatomy of a species under cultivation is essential for its systematic characterization, especially important in plants with high rates of natural hybridization, as T. trifoliata. This study constitutes a contribution for future research aimed to clarify biochemical and physiological aspects of T. trifoliata and thus evaluate its introduction as a commercial crop intended as cut foliage and/or as an ornamental plant.

-

Key words:

- Indigenous plant /

- Morphology /

- Cutting green /

- Pteridophyte.