-

Globally, conifers are pivotal sources of timber and pulpwood, thus holding immense economic and environmental value. The huge genome, high heterozygosity, prolonged vegetative growth period, and restricted genetic transformation system of conifers[1−5] limit the availability of genetic tools for investigating their developmental regulation, resulting in sluggish research progress. Studies identifying gene function in conifers have relied on heterologous expression in angiosperm model species. Since the initial report of transgenic Populus in 1987[6], significant strides have been made in achieving stable genetic transformation in various forest tree species. Subsequent to this, various genetic transformation systems for conifers have been reported. In 1991, Agrobacterium rhizogenes was employed to infect aseptic seedlings of European larch (Larix decidua Mill.), yielding transgenic plants with stable foreign gene expression[7]. Numerous Agrobacterium strains, leading to tumor development in a variety of coniferous species, have been identified[7, 8]. However, reports of successful regeneration in conifers stably transformed using Agrobacterium[9−13], as well as stable transformation via particle bombardment[14−17], are scarce, primarily due to inadequate regeneration procedures[18]. Recent developments and explorations in transgenic methods have made the mere transfer of DNA into plant cells no longer a limiting factor. Yet, the ability to regenerate complex tissues or organs after DNA transfer remains a major challenge[19]. Additionally, the establishment of genetic transformation systems is ongoing for most coniferous species, with successful transformation limited to a few species, often hindered by issues like low efficiency[20]. Currently, the focus of conifer genetic transformation is on enhancing growth rates, wood properties, pest resistance, stress tolerance, and herbicide resistance[21−27].

This review offers a comprehensive overview of recent advancements in genetic transformation technologies and their applications in conifers. Influencing factors in genetic transformation encompass vector construction (Agrobacterium strain type, promoter types, and target genes), DNA delivery methods (Agrobacterium-mediated, biobombardment, and protoplast transformation), and plant regeneration pathways. We also propose various strategies to advance genetic transformation in conifers, including optimizing transformation protocols, elucidating molecular mechanisms, enhancing tissue culture techniques, overcoming cell wall barriers, exploring genetic variation, employing nanoparticle and non-tissue culture-mediated transformation, utilizing genome editing tools, and encouraging international collaboration.

-

The strains of Agrobacterium utilized in plant genetic transformation are categorized into three types: octopine, nopaline, and agropine (succinamopine), represented by strains LBA4404, GV3101, and EHA101/EHA105, respectively. Agrobacterium strains exhibit differential abilities to transform recipient material (Table 1). Humara et al. documented the transfer and expression of foreign chimeric genes in the cotyledons of Pinus pinea[28]. It was observed that EHA105, containing the plasmid p35SGUSint, demonstrated greater infectivity compared to LBA4404 or C58GV3850, with 49.7% of cotyledons exhibiting diffuse blue staining 7 d post-infection. Similarly, Le et al. employed three strains, EHA105, LBA4404, and GV3101, to facilitate the transformation of white spruce, yet only EHA105 proved effective[29]. In another study testing various A. tumefaciens strains (EHA105, GV3101, and LBA4404), the highest frequency (60%) of transient β-glucuronidase expression in Slash pine embryos was observed with Agrobacterium strain GV3101, yielding over 330 blue spots per embryo[30]. Liu successfully developed a high-efficiency Agrobacterium-mediated transient gene expression system for P. tabuliformis callus using strain GV3101, achieving a peak transient transformation efficiency of 70.1%[31]. Even within the same Agrobacterium strain, the effects vary significantly owing to differences in the structures of the constructed vectors. Grant et al. introduced six distinct plasmids – pMP2482, pTGUS, p4CL, pSLJ1111, pLN27, and pLUG – into A. tumefaciens strain KYRT1 and demonstrated that the pSLJ1111 and p4CL plasmids were markedly more effective than the others[32]. Consequently, trials targeting specific conifer species are essential to ascertain suitable strains for transformation.

Table 1. Plant expression vector construction.

Tree species Plasmids Strains Genes Promoters Ref. Pinus Pinus pinea p35SGUSint EHA105/LBA4404/

C58GV3850uidA 35S [28] Pinus strobus pGIN/pBIV/pBIVSAR/pBINm-gfp5-ER C58pMP90 GUS 35S/2 × 35S [9] pCAMBIA1301 GV3101 GUS 35S [10] Pinus taeda pAD1289/pToK47/pBISN1/pWWS006 LBA4404/GV3101/EHA105 GUS 35S [51] pPCV6NFHygGUSINT GV3101 GUS 35S [52] pGUS3/pSSLa.3 EHA101/EHA105 GUS 35S/RbcS [53] pCAMBIA1301 EHA105 GUS 35S [54] pCAMBIA1301 GV3101/EHA105/LBA4404 GUS 35S [55] pBIGM LBA4404 Mt1D/GutD 35S [22] Pinus radiata pBI121 LBA4404 GUS 35S [56] pGA643 AGL1 GUS 35S [11] pGUL/pKEA EHA105 NPTII/uidA/Bar 35S [57] pMP2482/pTGUS/ p4CL/pSLJ1111/pLN27/pLUG KYRT1 GFP 35S/CoA ligase 1 [32] Pinus pinaster pPCV6NFGUS C58pMP90 GUS 35S [58] pBINUbiGUSint EHA105/AGL1/LBA4404 GUS ubi1 [59] Pinus patula pAHC25 LBA4404 GUS ubiquitin [12] Pinus elliottii pCAMBIA1301 EHA105/GV3101/LBA4404 GUS 35S [30] Pinus massoniana pBI121 EHA105 CslA2 35S [13] Pinus tabuliformis pBI121 GV3101 GUS 35S [31] Larix Larix decidua pRi11325 Rhizogenes strains 11325 Ri plasmid / [7] pCGN1133/pWB139 strains 11325 Bt/aroA 35S [21] hybrid larch pMRKE70Km C58pMP90 NPTII 35S [60] pCAMBIA1301 GV3101 GUS 35S [61] Larix olgensis pCAMBIA1300/pBI121 GV3101 GUS 35S/PtHCA2-1 [35] VB191103 GV3101 LoHDZ2 35S [25] Larix kaempferi Super1300-GFP GV3101 LaCDKB1;2 Super [24] Picea Picea sitchensis MOG23 LBA4404/strain 1065 GUS 35S [62] Picea abies pAD1289/pToK47/pBISN1/pWWS006 LBA4404/GV3101/EHA105 GUS 35S [51] pBIV10 C58/pMP90 GUS 2 × 35S [63] pET-22b LBA4404 Cry3A 35S [23] Picea mariana pBIV10 C58/pMP90 GUS 2 × 35S [63] Picea glauca pBIV10 C58/pMP90 GUS 2 × 35S [63] pBI121 EHA105/GV3101/

LBA4404GUS 35S [29] pUC19 C58pMP90 WUS/CHAP3A G10 [64] Abies Abies spp. pTS2 AGLO GUS 2 × 35S [65] Abies koreana pBIV10/MP90 C58/pMP90/LBA4404 GUS 2 × 35S [66] Taxus Taxus brevifolia/Taxus baccata / Bo542/C58 / / [8] Chamaecyparis Chamaecyparis obtusa pBin19-sgfp C58/pMP90 GFP 35S [67] Cryptomeria Cryptomeria japonica pIG121-Hm/pUbiP-GFP-Hyg GV3101/pMP90 GFP/GUS 35S/ubiquitin [68] pIG121-Hm GV3101/pMP90 GFP 35S [69] Types of promoters

-

Although a variety of promoters are utilized in angiosperms for the genetic engineering of both monocots and dicots, their use in gymnosperms remains limited (Table 1). The cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter, a prominent constitutive driver of transgene expression, is predominantly utilized in dicots[33]. However, despite their frequent use for gene overexpression, the activity of constitutive CaM35S promoters is notably lower in conifers[34, 35]. Constructs containing the uidA gene, which encodes β-glucuronidase (GUS), or the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene, were introduced into embryogenic tissues to monitor the activities of these protein products over time. Expression levels of the uidA gene were minimal with a 35S-gus intron construct, yet increased twentyfold when using a 35S-35S-AMVgus::nptII construct[9].

Furthermore, although the CaM35S promoter is functional in certain conifers, there remains a lack of efficient promoters capable of high-level, constitutive gene expression that can accommodate multiple transgenes within a single vector. Consequently, there is a need for diverse and robust promoters specifically tailored for gymnosperms, potentially in synergy with CRISPR/Cas-mediated gene editing technology[36]. CmYLCV[37], isolated from Cestrum yellow leaf curling virus—a double-stranded DNA plant pararetrovirus of the Caulimoviridae family—demonstrates heritable, strong, and constitutive activity in both monocot and dicot species. ZmUbi[38], a ubiquitin promoter derived from maize, exhibits high efficiency exclusively in monocot species, including maize[38], wheat[39], sugarcane[40], rice[41, 42], sorghum[43], and others[44]. Utilizing transient expression technology in Chinese fir protoplasts, an in vivo molecular biological investigation compared the activities of Cula11 and Cula08—constitutive expression promoters from Chinese fir—with CaM35S[45, 46], CmYLCV, and ZmUbi, commonly used in plant genetic engineering, revealing that Cula11 and Cula08 exhibited higher activity[36]. Seven constitutive promoters underwent screening via a dual luciferase (LUC) transient expression assay, revealing that PcUbi exhibited the highest activity in Cryptomeria japonica embryogenic tissue and was thus deemed the most suitable promoter for driving SpCas9 expression[47]. The pCAMBIA1300-PtHCA2-1 promoter-GUS binary expression vector, harboring the open reading frame (ORF) of the GUS gene under the control of the poplar high cambial PtHCA2–1 promoter, was subjected to testing, resulting in the observation of tissue-specific expression of the GUS gene in somatic embryos of transgenic larch[35].

Transformed exogenous genes

-

Despite significant progress in transgenic methodologies for conifers, the preponderance of exogenous genes employed thus far are screening marker genes (e.g., uidA, npt II, hpt, GFP, and GUS). Reports of transformations involving target genes that hold genuine potential for practical applications in production are scarce (Table 1). The initial report on the regeneration of transgenic conifer plants, specifically larch, expressing value-added genes involved herbicide and insect resistance genes via Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer[21]. Some research groups have successfully transferred insect and herbicide resistance genes into various conifer species[14−16, 23, 26, 48, 49]. Overexpression of the LoHDZ2 gene in the embryonic tissues of L. olgensis has been suggested to confer enhanced stress resistance[25]. Simultaneously express two genes: mannitol-1-phosphate dehydrogenase (Mt1D) and glucitol-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (GutD) enhanced tolerance to salt stress in transgenic loblolly pine[22]. The overexpression of the LaCDKB1;2 gene in the embryonic tissues of L. kaempferi has been shown to promote cell proliferation and high-quality cotyledon embryo formation during somatic embryogenesis. This provides a foundation for examining the regulatory mechanisms of somatic embryogenesis in larch and for developing new breeding materials[24]. Overexpression of WUSCHEL-related HOMEOBOX 2 (WOX2) during proliferation and maturation of somatic embryos of P. pinaster led to alterations in the quantity and quality of cotyledonary embryos[50]. However, reports of transformation involving target genes that possess genuine potential for practical applications remain limited.

-

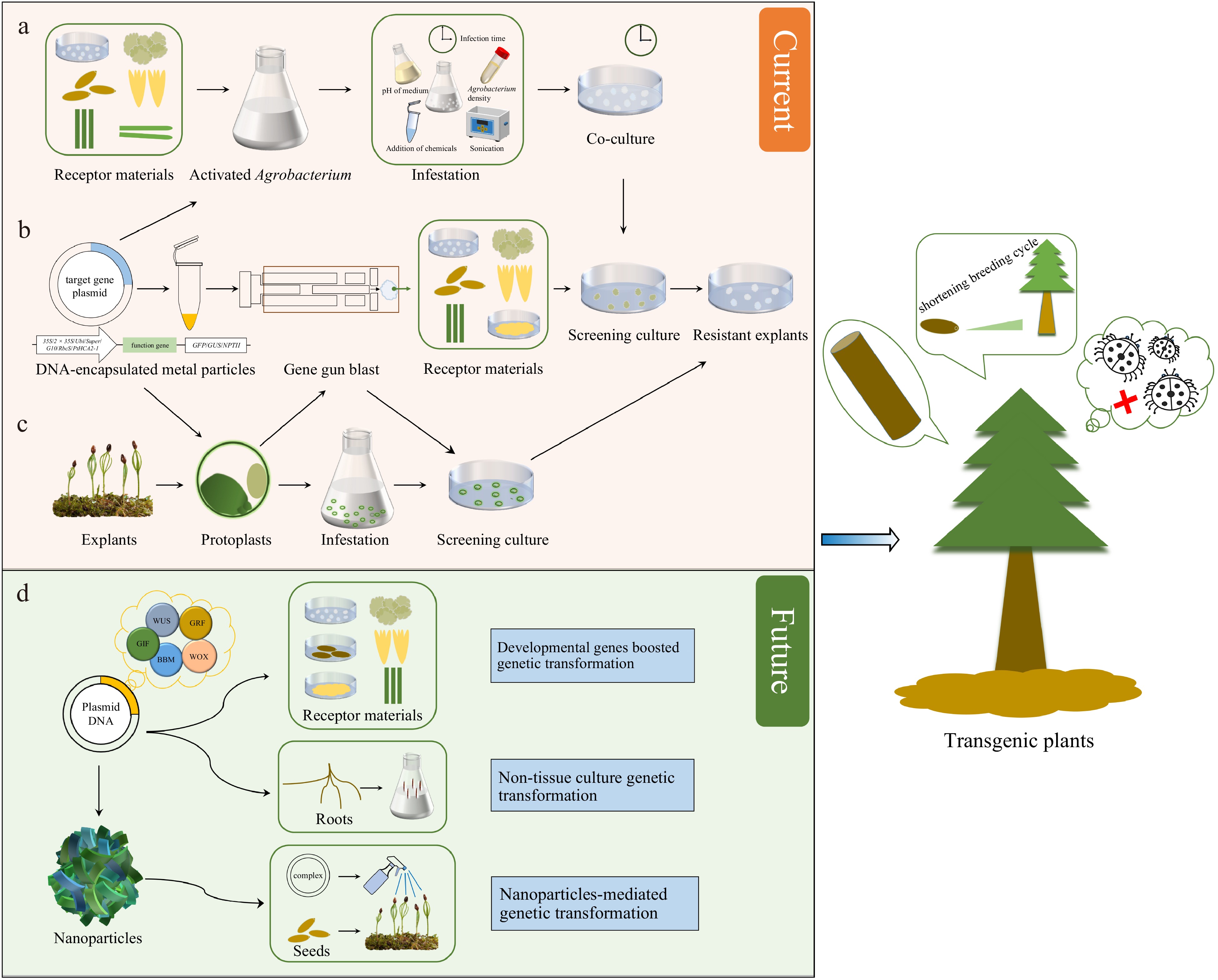

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation represents the most prevalent method for achieving stable genetic transformation. Cell lines generated through this method demonstrate enhanced stability in transgene expression among progeny and reduced instances of transcriptional and posttranscriptional gene silencing[19]. However, this method encompasses several drawbacks, such as bacterial overgrowth and tissue necrosis, arising from adverse co-cultivation conditions, potentially affecting the transformation frequency[19]. Nevertheless, from the standpoint of conversion efficiency, it remains a valuable technology[68]. Since the inaugural report of conifer transformation[7], there have been significant advancements in Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation. In recent years, there has made encouraging progress in the field of genetic transformation of conifers (Fig. 1a & Table 2), resulting in transgenic plants derived from European larch[21], hybrid larch[60, 61], white spruce[29, 63, 64], Norway spruce[23, 51], loblolly pine[20, 52, 53, 55], and radiata pine[11, 32, 56, 57].

Figure 1.

Techniques and prospects for genetic transformation of conifers. (a) Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation. (b) Genetic transformation via biolistic bombardment. (c) Protoplast transformation. (d) Potential strategies for transformation improvement in conifers.

Table 2. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in conifers.

Tree species Acceptor materials Co-culture time OD600nm Results Ref. Pinus Pinus pinea Cotyledons 3 d 1 Cotyledons forming buds [28] Pinus strobus Embryogenic tissues 2 d 0.6 Regenerated plant [9] Mature zygotic embryos 12 h 0.8−1.0 Regenerated plant [10] Pinus taeda Embryogenic tissues 2 d 1 Transient expression [51] Mature zygotic embryos 3−5 d / Regenerated plant [52] Shoot apex 7 d / Transgenic plants [53] Mature zygotic embryos 3−5 d 0.8−1.0 Transgenic plants [54] Mature zygotic embryos 3−5 d 0.8−1.0 Transgenic plants [55] Mature zygotic embryos 3−5 d 0.5−1.0 Improve salt tolerance [22] Pinus radiata Embryogenic tissues 1 d 0.6 Stable transformation [56] Cotyledons 5−60 min OD550nm = 0.4 Transgenic plants [11] Embryogenic tissues 5 d OD550nm = 0.5−0.8 Transgenic plants [57] Micropropagated shoot 3 d OD550nm = 0.35−0.4 Transgenic plants [32] Pinus pinaster Embryogenic tissues 36 h 0.6 Transgenic plants [58] Embryogenic tissues 3 d 0.3 Transgenic plants [59] Pinus patula Embryogenic tissues 2 d 0.5−0.75 Transgenic tissues [12] Pinus elliottii Mature zygotic embryos 3 d 0.9 Transgenic plants [30] Pinus massoniana Mature zygotic embryos 3 d 0.5 Transgenic plants [13] Pinus tabuliformis Callus/hypocotyls/Needles 3 d 0.8 Transient expression [31] Larix Larix decidua Hypocotyls 2−3 d / Regenerated plant [7] Hypocotyls 4 d / Regenerated plant [21] hybrid larch Embryogenic tissues 2 d 0.3 Regenerated plant [60] Embryogenic tissues 2 d 0.5 Regenerated plant [61] Larix olgensis Embryogenic tissues 3 d 0.6 Transgenic plants [35] Embryogenic tissues 2 d 0.5 Enhance stress resistance [25] Larix kaempferi Embryogenic tissues 2 d 0.1 Promotes cell proliferation [24] Picea Picea sitchensis Embryogenic cell lines 3 d 0.8−1.1 Stable transformation [62] Picea abies Embryogenic tissues 2 d 1 Transient expression [51] Embryogenic tissues 2 d 0.6 Transgenic plants [63] Embryogenic tissues 2 d / Transgenic plants [23] Picea mariana Embryogenic tissues 2 d 0.6 Transgenic plants [63] Picea glauca Embryogenic tissues 2 d 0.6 Transgenic plants [63] Embryogenic tissues 2 d 1 Transgenic plants [29] Embryogenic tissues / / Transgenic plants [64] Abies Abies spp. Embryogenic tissues 2 d 0.6 Transgenic plants [65] Abies koreana Embryogenic tissues 3 d 0.6 Transgenic plants [66] Taxus Taxus brevifolia/Taxus baccata Shoot segments 3 d / Gall formation [8] Chamaecyparis Chamaecyparis obtusa Embryogenic tissues 2 d 0.3 Transgenic plants [67] Cryptomeria Cryptomeria japonica Embryogenic tissues 2 d 0.15 Enhance transformation [68] Embryogenic tissues 2 d 0.2−0.6 Transgenic plants [69] Although Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer is extensively employed in numerous biotechnology laboratories, its large-scale application in conifer transformation is hindered by challenges in propagating explant material, selection inefficiencies, and low transformation rates[51]. Wenck et al. explored co-cultivation conditions and various disarmed Agrobacterium strains to enhance transformation efficiency. They discovered that incorporating additional virulence genes, such as a constitutively active virG or extra copies of virG and virB from pTiBo542, amplified the transformation efficiency of Norway spruce by 1000-fold relative to initial experiments, which exhibited minimal or nonexistent transient expression[51]. Tang examined the influence of additional virulence (vir) genes in A. tumefaciens and the impact of sonication on the transformation efficiency of loblolly pine[54]. Utilizing plasmids with supplementary vir genes and sonication significantly enhanced the transfer efficiency, affecting not only transient expression but also the recovery of hygromycin-resistant lines. In their studies on Agrobacterium-mediated hybrid larch transformation, Levee et al. observed one to two transformation events per 100 cocultured masses[60]. Introducing 100 µM of coniferyl alcohol led to an increase in yield. Other studies demonstrated that sonication[10, 30] and the addition of chemicals, including okadaic acid, trifluoperazine, acetosyringone, thidiazuron, and others[10, 30, 35, 66, 70], significantly enhanced the transformation efficiency of conifers and further advanced the transformation system. Additionally, several groups have illustrated that cold treatment of Agrobacterium can augment transformation efficiency[13].

Transformation frequencies depend on species, genotype, and post-cultivation protocol. In a study involving three species, Picea mariana was transformed at the highest frequency, followed by P. glauca and P. abies[63]. Furthermore, for all the species, transgenic plants were regenerated using modified protocols for somatic embryo maturation and germination. Le et al. devised an efficient method for the reproducible transformation of embryogenic white spruce tissue using A. tumefaciens-mediated gene transfer[29]. A shoot-based, genotype-independent transformation method employing A. tumefaciens facilitated plant recovery and enabled the transformation of elite germplasm[53]. Shoots from 4- to 6-week-old seedlings and adventitious shoots from cultures were inoculated with A. tumefaciens, underwent selection, and were subsequently regenerated. Micropropagated shoot explants from P. radiate have successfully been employed to produce stable transgenic plants via A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation[32]. It is crucial during the transformation process to inhibit and prevent contamination caused by excessive Agrobacterium growth. In the A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation of P. pinea cotyledons, a high cotyledon mortality rate occurs, possibly related to the plant's hypersensitive response to bacterial infection[28]. For conifers, non-toxic antibiotics to plant cells, like cefotaxime sodium (Cef) or timentin, are frequently incorporated into the medium. Also, in the post-transformation selection medium, selecting transformants is crucial for obtaining transgenic plants. If tissues are initially cultivated for 10 d on a medium with timentin (400 mg·L–1) to avert bacterial overgrowth, the recovery of kanamycin-resistant tissues is enhanced before applying selection pressure[29]. An evaluation of three antibiotics was conducted to assess their effectiveness in eliminating A. tumefaciens during the genetic transformation of loblolly pine using mature zygotic embryos[55]. Exposing the cultures to 350 mg·L–1 of carbenicillin, Cef, and timentin for a duration of up to 6 weeks failed to eliminate Agrobacterium; however, increasing the concentration to 500 mg·L–1 successfully eradicated the bacterium from co-cultured zygotic embryos[55].

Identifying the optimal combination of infection time and concentration is crucial for successful conifer transgenesis during genetic transformation experiments. Generally, the bacterial solution concentration for infecting conifers is maintained at an OD600 of 0.3–0.8. Elevating the Agrobacterium concentration and extending the infection duration can result in excessive bacterial proliferation and hypersensitive necrosis of explants, thereby diminishing transformation efficiency[28]. Conversely, employing a low-density Agrobacterium suspension and a brief infection period often results in weak infectivity, which similarly reduces transformation efficiency[13]. Moreover, the infection duration influences T-DNA transfer and, consequently, the efficiency of genetic transformation. The infection duration, typically less than 30 min, varies depending on the explant type and the physiological status of the conifer species. However, both the concentration and infection duration of the bacterial solution must be tailored to the condition, type, and environmental factors of the explants, necessitating further research.

Genetic transformation via biolistic bombardment

-

Particle bombardment, also known as biolistics, serves as an alternative method for plant genetic transformation, circumventing the limitations associated with Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation[71]. This method is not limited by biological constraints and is applicable to a broad spectrum of plant species. However, in the context of conifer transformation frequency, biolistic techniques are generally regarded as less effective than Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation[68]. Foreign genes have successfully been expressed in all tested conifer tissues via particle bombardment, encompassing embryos, seedlings, xylem, pollen, needles, buds, cell suspension cultures, embryogenic callus, cell aggregate cultures, and roots (Fig. 1b & Table 3). While most of these attempts yielded only transient expression, they have offered insightful information about the factors influencing gene expression in various tissues capable of regeneration[20]. GFP introduction into conifer tissues has been achieved through microprojectile bombardment, with transient expression subsequently observed[72]. The CaMV35S promoter facilitated GUS gene expression in loblolly pine tissues[73]. Microprojectile bombardment proves to be an effective technique for assaying transient gene expression in pine, and it harbors potential for generating transgenic pine plants. Using high-velocity microprojectiles, plasmid DNA with the GUS gene, under the control of the CaMV35S promoter, has been introduced into cultured Douglas fir cotyledons[74]. Additionally, the particle gun technique has been employed to transform a variety of receptor materials in different tree species, including callus and pollen of larch[75, 76], Chir pine[16], and Norway spruce[14, 77−80]. Particle bombardment has been applied to Lodgepole pine, yellow cypress, western hemlock, jack pine, and black spruce pollen to achieve transient GUS gene expression, demonstrating the method's viability for pollen transformation[81]. Furthermore, particle bombardment has facilitated the testing of transient expression of heterologous promoters in organized tissues and angiosperm promoters in gymnosperms[82]. Comparative analyses have been conducted on the initiation strengths of transient expression for eight distinct promoter sequences, based on the relative levels of GUS expression[76].

Table 3. Biolistic bombardment genetic transformation in conifers.

Tree species Acceptor materials Plasmids Promoters Genes Results Ref. Pinus Pinus taeda Cotyledons pBI221 35S GUS Transient expression [73] Pinus radiata Suspension cells pBI221 35S GUS Transient expression [87] Embryogenic tissues pCW103/pCWI22 2 × 35S gusA Transient expression [88] Cotyledons pBI121/pCGUΔl/

pAIGusN/pActl-D35S/UbBI/Adhl/Actl gusA Transient expression [89] Embryogenic tissues pRC101/pCW122 35S/Emu uidA Transgenic plants [83] Embryogenic tissues pAHC25/pCW122 maize ubiquitin/35S GUS/Bar Transgenic plants [14] Calli pCW122/pCADsense 35S npt II/Cad Transgenic calli [90] Embryogenic tissues pMYC3425/pAW16/

pCW132/pRN2Emu/ubi Cry1Ac Transgenic plants [15] Pinus concorta/Pinus banksiana Mature pollen pBM113Kp/pRT99GUS/

pAct1-D/pGA98435S/rice actin GUS Transient expression [81] Pinus sylvestris Calli/Vegetative buds/

Suspension cellspBI221 35S GUS Transient expression [91] Pollen pBI221/pRT99/pBI410/

pBI426/pBM11335S/EmP/UbB1 GUS Transient expression [79 ] Pinus strobus Embryonal masses p35S-GFP/mGFP4 35S GFP Transient expression [72] Pinus aristata/Pinus griffithii/Pinus monticola Pollen tubes pBI221 35S GUS Transient expression [92] Pinus patula Embryogenic tissues pAHC25 35S Bar/GUS Somatic embryos [48] Pinus nigra Embryogenic tissues pCW122 2 × 35S GUS Somatic embryos [86] Pinus roxbughii Mature zygotic embryos pAHC25 maize ubiquitin Bar/GUS Transgenic plants [16] Picea Picea glauca Zygotic embryos/Seedlings/

embryogenic calluspUC19 35S GUS Transient expression [82] Somatic embryos pBI426 35S GUS Stable transformation [93] Somatic embryos pTVBT41100 35S GUS/Bt Transgenic plants [49] Embryonal masses p35S-GFP/mGFP4 35S GFP Transient expression [72] Embryogenic tissues pKUB/pBI426 maize ubiquitin/35S cry1Ab Transgenic plants [26] Picea mariana Embryogenic tissues pRT99GUS/pBM113Kp 35S GUS Transient expression [94] Embryogenic tissues pRT99GUS/pGUSInt/

pMON990935S/Em protein of wheat/Rbcs/NOS/

Actin/ArabinGUS Transient expression [76] Mature pollen pBM113Kp/pRT99GUS/

pAct1-D/pGA98435S/rice actin GUS Transient expression [81] Embryonal masses pRT99GUS/pBI426 35S GUS Transgenic plants [84] Pollen/Embryonal masses/ Somatic embryos p35S-GFP/mGFP4 35S GFP Transient expression [72] Mature somatic embryos pBI221.23 35S GUS Transgenic plants [17] Picea abies Somatic embryo pRT99gus 35S GUS Stable transformation [77] Embryogenic tissues pRT99gus/pJIT65/

Dc8gus/pBMI13Kp35S/2 × 35S/

Act1-D/Dc8GUS Transient expression [80] Pollen pBI221/pRT99/pBI410/

pBI426/pBM11335S/EmP/UbB1 GUS Transient expression [79] Embryogenic tissues pCW122 35S GUS Transgenic plants [95] Embryogenic tissues pAHC25 maize ubiquitin Bar Transgenic plants [78] Embryogenic tissues pAHC25/pCW122 maize ubiquitin/35S GUS/Bar Transgenic plants [14] Embryogenic tissues pAHC25 maize ubiquitin CCR Transgenic plants [27] Larix Larix × eurolepis Embryogenic tissues pRT99GUS/pGUSInt/

pMON990935S/Em protein of wheat/Rbcs/NOS/

Actin/ArabinGUS Transient expression [76] Larix laricina Embryonal masses pBI426/pRT99gus/

pRT66gus/pRT55gus35S/2 × 35S GUS Transient expression [75] Larix gmelinii Zygotic embryos pUC-GHG/pBI221-HPT 35S GUS/GFP Transgenic plants [34] Pseudotsuga Pseudotsuga menziesii Cotyledons pTVBTGUS 35S GUS Transient expression [74] Chamaecyparis Chamaecyparis nootkatensis Mature pollen pBM113Kp/pRT99GUS/

pAct1-D/pGA98435S/rice actin GUS Transient expression [81] Tsuga Tsuga heterophylla Mature pollen pBM113Kp/pRT99GUS/

pAct1-D/pGA98435S/rice actin GUS Transient expression [81] Abies Abies nordmanniana Embryogenic tissues pCW122 35S GUS Transgenic plants [85] Particle bombardment-mediated transformation is capable of regenerating whole plants. In P. glauca plants, the stable expression of an exogenous gene marked the first successful creation of transgenic plants using the particle gun method[49]. Walter et al. used a particle gun to bombard four embryonic cell lines of P. radiate, resulting in over 150 transgenic plants from 20 transformation experiments[83]. Analyses using Southern and Northern blotting confirmed the integration of the target gene into the genome. Particle bombardment facilitated the stable genetic transformation of P. mariana in two target tissues: mature cotyledonary somatic embryos and suspensions from embryonal masses, employing the Biolistic PDS-1000/He device[84]. The expression of the GUS gene in needles of regenerated seedlings demonstrates the potential for sustained transgene expression in spruce[17]. Using biolistic transformation, stable genetic transformation has been accomplished in embryogenic cultures of Abies nordmanniana, leading to the regeneration of transgenic plants[85]. A biolistic approach has successfully achieved stable transformation in embryogenic tissues of P. nigra Arn., specifically cell line E104[86]. Given its versatility and broad applicability, particle bombardment is anticipated to continue as a primary method in genetic transformation.

Particle bombardment possesses significant potential for producing transgenic conifer plants. A key objective in tree breeding involves reducing lignin content or modifying its composition, which would aid in delignification during pulping processes. When the antisense construct of the cinnamoyl CoA reductase (CCR) gene was introduced into Norway spruce, a significant reduction in the total lignin content of dry wood was observed compared to controls[27]. Lachance et al. conducted a study on the accumulation of crylAb protein in embryogenic tissues, somatic seedling needles, and 5-year-old field-grown needles of white spruce[26]. Insect feeding trials, both in the laboratory and the field, indicated that multiple transgenic spruce lines proved lethal to spruce budworm larvae. Through biolistic transformation of embryogenic tissue, transgenic radiata pine plants harboring the Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) toxin gene, cry1Ac, were successfully produced[15]. Ongoing research is being conducted on functional genes utilizing this technology[14, 16, 78].

Protoplast transformation

-

Protoplast technology enables various unique approaches to the genetic improvement of plants[96]. Protoplast transient expression assays serve as versatile tools in genomics, transcriptomics, metabolic, and epigenetic studies[97]. Coupling protoplast transient expression experiments with high-resolution imaging enables simple, rapid, and efficient analysis and characterisation of gene functions and regulatory networks. This includes protein subcellular localisation, protein-protein interactions, transcriptional regulatory networks, and gene responses to external cues[98−100]. Reporter genes commonly used, like LUC and GUS, are employed to assess gene activity in conifer protoplasts[87]. P. glauca protoplasts were transformed with the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter gene through electroporation[101]. Fir and pine protoplasts were successfully transformed with the LUC gene through electroporation, with gene expression enhanced by the addition of polyethylene glycol (PEG) to the mixture[102]. Developments in methods for transient gene expression have been made for protoplasts of black spruce and jack pine[103]. In electroporated protoplasts of P. glauca, P. mariana, and P. banksiana, the activity levels of exogenous genes depend on the promoter, electroporation conditions, and the targeted cell line[104]. A new transient transformation system for Chinese fir protoplasts has been established, achieving cell wall regeneration and protoplast division. This method serves as a reference for conducting functional studies on Chinese fir-related genes[105]. However, the challenges in establishing protoplast regeneration systems in conifers mean that protoplast-based genetic transformation studies primarily focus on transient gene expression and the investigation of gene function and expression regulation (Fig. 1c).

-

Establishing an effective and stable regeneration system is crucial for rapidly expanding conifer populations for seedling production and successful heritage transformation. A range of plant materials, each with unique advantages, serves as transformation receptors for conifers. These include zygotic embryos, hypocotyls, embryonic tissues, somatic embryos, protoplasts, stem tips, and pollen[7, 10, 13, 31, 51, 53, 81, 101]. Embryonic tissues have been the focus of extensive research as receptors in numerous studies[9, 27, 35, 51, 57, 58, 85]. Additionally, Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation using mature zygotic embryos as explants has been successfully implemented in P. taeda[22, 52, 54, 55], P. elliottii[30], and P. massoniana[13]. Cotyledons and hypocotyls are identified as suitable explants for genetic transformation[7, 11, 21, 28]. Currently, embryonic tissue of conifers is predominantly used as recipient material through the somatic embryogenesis pathway to obtain stably-transformed regenerated plants (Tables 2 & 3).

A primary challenge in the genetic transformation of coniferous trees involves plant regeneration[106]. This challenge arises primarily from the unique biological properties and regeneration mechanisms of conifers. Tissue culture in conifers proves more challenging than in other plants. This is attributed to the cells of conifers, especially those from mature trees, which have a lower capacity for differentiation and regeneration[107]. The tissue culture process entails inducing cells or tissues from the parent plant to develop into new plants under controlled conditions, a process notably less efficient in conifers. Furthermore, during tissue culture, particularly over extended periods, the genetic stability of conifers may be affected. Cell division and differentiation, occurring during tissue culture, may introduce genetic mutations; additionally, genome doubling, leading to the formation of polyploids, can also occur. Consequently, even if plant regeneration is successful, the resultant plants may exhibit genetic variations, potentially posing challenges in subsequent applications and research[19, 106]. The regeneration of conifer tissue is notably sensitive to the balance of plant hormones and other culture conditions. Different species of conifers often require specific combinations of hormones and culture environments, thereby complicating the identification of a universal method applicable to all types[108]. Conifers generally exhibit a long regeneration process, which implies that the entire process from tissue culture to mature plant consumes a considerable amount of time, acting as a limiting factor in research and application. Variations in regeneration capabilities among different species of conifers are notable.

In summary, although the genetic transformation and regeneration of coniferous trees are theoretically feasible, their practical implementation is fraught with several challenges, most notably in tissue culture efficiency, genetic stability maintenance, and adaptation to different species' characteristics[109]. Addressing these challenges necessitates in-depth research and substantial technological innovation.

-

Despite the numerous promising success cases mentioned, it must be acknowledged that genetic transformation continues to pose a significant challenge for most conifer researchers. To date, none of these methods have proven universally applicable across multiple species or varied genotypes. Consequently, while a method may appear promising, it often remains confined to successful implementation under specific laboratory conditions, lacking widespread applicability. Significant progress is still required to develop a universal model for conifers that is as straightforward, efficient, and reproducible as those established for angiosperm model species.

Complex biology

-

Conifers possess distinct and complex biological characteristics, setting them apart from commonly utilized genetic engineering plants like Arabidopsis or tobacco. Their prolonged generation times, expansive genomes, and elaborate reproductive processes contribute to the challenges in working with them[1, 2, 4].

Low transformation efficiency

-

Despite the establishment of transformation protocols, the efficiency of integrating foreign genes into the conifer genome frequently remains low[54, 63]. Consequently, only a minor fraction of transformed cells effectively express the introduced gene, posing significant challenges in producing stable and predictable genetically modified organisms.

Species variability

-

Various conifer species exhibit unique biological traits and varying responses to transformation techniques. A technique effective in one conifer species might not yield similar results in another, necessitating tailored optimization for each species.

Genetic complexity

-

The size and complexity of conifer genomes pose challenges in the introduction and expression of foreign genes. A thorough understanding of the regulatory elements and mechanisms within conifer genomes is crucial for genetic engineering success[3−5]. However, such knowledge is typically less comprehensive than that available for model plant species.

Tissue culture challenges

-

Conifers often require specialized tissue culture techniques for regeneration and propagation. Developing suitable tissue culture methods for conifers, particularly those compatible with genetic transformation, is a significant hurdle. Studies have indicated that the induction rate of embryogenic tissues from immature seeds in conifers is influenced by both the genotype and the embryonic developmental stage[110, 111].

Phenolic compounds

-

Conifers, like many plants, contain high levels of phenolic compounds, such as lignins and polyphenols[112, 113]. These compounds may exert inhibitory effects on the enzymes used in the genetic transformation process. Phenolic compounds are known to contribute to oxidative stress, DNA degradation, and may interfere with the integration of foreign genes into the plant genome.

Secondary metabolites

-

Conifers produce a diverse array of secondary metabolites, including terpenoids and flavonoids, which can potentially affect the success of genetic transformation. These compounds can exhibit toxic effects on the transformed cells or may interfere with the activity of introduced genes.

Cell wall composition

-

The cell walls of conifers are notably complex and rigid, serving to provide structural support to the plant. However, this complexity may impede the delivery of foreign DNA into plant cells. Efficient transformation frequently necessitates overcoming these barriers to ensure that the introduced genetic material successfully reaches the nucleus of the target cells[114, 115].

Genetic variation

-

The presence of genetic variation within conifer populations may influence the success of genetic transformation. Individuals within a species often exhibit varying responses to transformation protocols, and optimizing these protocols for broader applicability presents a significant challenge.

Addressing these biochemical factors typically necessitates the development of specialized techniques and treatments within the genetic transformation process. For instance, researchers might utilize tissue culture conditions designed to mitigate the effects of phenolic compounds, or employ specialized methods to enhance the delivery of foreign DNA through the cell wall.

Comprehending the biochemical makeup of conifers and customizing transformation methods to suit their unique characteristics is an active area of research. Advances in biotechnology, encompassing the development of more robust transformation protocols and the elucidation of genes involved in stress responses, may play a pivotal role in surmounting these biochemical barriers in the future.

-

Addressing the challenges associated with the genetic transformation of conifers necessitates a comprehensive approach that integrates advancements across multiple key domains (Fig. 1d). The following delineates potential strategies and focal areas.

Optimization of transformation protocols

-

It is imperative for researchers to persist in refining and optimizing transformation protocols tailored to various conifer species. This encompasses enhancing the efficiency of introducing foreign genes into conifer cells and developing uniform methods applicable across diverse species. The utilization of developmental genes may prove beneficial in promoting transformation. These genes, capable of acting through diverse developmental mechanisms to enhance the regeneration of transgenic cells, have seen extensive use in model plants to stimulate embryogenesis and, in some instances, organogenesis[116−118]. In summary, the overexpression of regeneration-regulating transcription factors, including BBM, WUS2, WOX5, GRF4, and GIF1, could enhance genetic transformation in conifers characterized by low regeneration efficiency, substantial transformation difficulty, and genotype limitation.

Understanding molecular mechanisms

-

Gaining a deeper understanding of the molecular and biochemical processes in conifers is essential. This necessitates research into the regulation of gene expression, understanding the role of secondary metabolites, and comprehending the response of conifers to stress conditions. This knowledge is crucial in informing the development of transformation methods that are synergistic with the unique biology of conifers.

Tissue culture advances

-

The improvement of tissue culture techniques, crucial for supporting the regeneration and propagation of conifer plants, is vital. The development of protocols for efficient plant regeneration from transformed cells can significantly bolster the success of genetic transformation. Conversely, most prevailing methods for plant genome modification entail regenerating plants from genetically modified cells in tissue culture, a process that is technically challenging, costly, time-consuming, and limited to a narrow range of plant species or genotypes[119]. Cao et al. outlined a notably straightforward cut–dip–budding (CDB) delivery system, which includes inoculating explants with A. rhizogenes, subsequently generating transformed roots that yield transformed buds through root suckering[120]. The advancement of methods that circumvent laborious procedures, such as tissue culture, and facilitate obtaining transgenic and gene-edited plants, marks a significant breakthrough in conifer research.

Overcoming cell wall barriers

-

Exploring strategies to overcome the challenges presented by the complex cell walls of conifers is imperative. This could involve employing enzymes or other agents to facilitate the penetration of foreign DNA into plant cells. In the realm of conifer biotechnology, the initial protoplast extraction in P. contorta laid the foundation for the establishment of a transient transformation system in conifers[121].

Understanding genetic variation

-

Recognizing and addressing genetic variation within conifer species is critical. Customizing transformation protocols to accommodate the diverse genetic backgrounds of individuals within a species can lead to broader success in genetic transformation[122].

Application of advanced biotechnologies

-

The utilization of cutting-edge biotechnological tools, notably CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, can offer more precise control over the modification of conifer genomes. These advanced technologies have the potential to overcome several challenges associated with traditional genetic transformation methods. Genome editing represents a powerful technology for functional genomic research and trait improvement. Cui et al. successfully achieved knockout of the DXS1 gene in white spruce (P. glauca) employing the conifer-specific CRISPR/Cas9 toolbox[123]. Recently, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis has been demonstrated in radiata pine[124], Japanese cedar[47], and Chinese fir[36], underscoring its feasibility in conifers. This represents a potent genome editing system of significant importance for gene function studies and the genetic improvement of plant traits, likely to make substantial contributions to the development of molecular breeding in conifers.

Nanoparticle-mediated genetic transformation

-

In future research endeavors, the use of nanomaterials for genetic modification promises to expand the scope of plant molecular research, particularly for conifers, which currently lack efficient systems for regeneration and stable genetic transformation. Nanocarriers are characterized by their large surface area, facilitating efficient gene loading, alongside high biocompatibility to safeguard the loaded genes, coupled with low toxicity and enhanced safety[125, 126]. Consequently, nanoparticles hold the potential to be utilized in developing transgenic technologies for conifer regeneration without dependency on tissue culture, potentially overcoming the technical challenges in genetic transformation of recalcitrant plant genotypes. Conversely, the exploration of stable and targeted nanocarrier-mediated gene editing technologies offers the prospect of achieving genetic improvements in conifers.

Ecological considerations

-

Considering the ecological significance of conifers, comprehensive risk assessments and detailed ecological studies should accompany all attempts at genetic modification. Comprehending the potential environmental impact and addressing public concerns are imperative for the responsible and sustainable deployment of genetically modified conifers.

International collaboration

-

Given the global distribution of conifers, international collaboration among researchers, institutions, and regulatory bodies is essential to foster the sharing of knowledge, resources, and expertise. Such collaborative efforts can significantly accelerate progress and enhance the effectiveness in addressing challenges.

Sustained research and ongoing technological advancements, in conjunction with a holistic and interdisciplinary approach, are crucial to unlocking the full potential of genetic transformation in conifers, while simultaneously ensuring the responsible and ethical application of these technologies.

-

Many reports have documented the successful expression of exogenous genes in conifers using Agrobacterium-mediated, particle bombardment-mediated, and protoplast-based genetic transformation methods. However, the genetic transformation of conifers faces several challenges, including low transformation efficiency, high dependence on recipient genotypes, difficulties in plant regeneration. Overall, the genetic transformation of conifers remains heavily reliant on extensive experience and sophisticated technical skills, rendering its widespread application challenging for most conifer researchers. Overcoming these challenges will usher in a new era of productivity and quality in forestry. Several potential strategies have been proposed to improve conifer transformation, including the optimization of transformation protocols, understanding molecular mechanisms, improving tissue culture techniques, overcoming cell wall barriers, understanding genetic variation, employing nanoparticle- and non-tissue culture-mediated genetic transformation, utilizing genome editing tools, fostering international collaboration, and more. In conclusion, with the ongoing development of molecular biotechnology and enhancement of various regeneration and transformation systems, research on the genetic transformation of conifer species is poised for continued progress and broader applicability.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhao J, Niu S, Zhang J; draft manuscript preparation: Zhao H; Figure creation: Zhao H. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFD2200102), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32371834), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32271836), the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFD2200104).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Shihui Niu is the Editorial Board member of Forestry Research who was blinded from reviewing or making decisions on the manuscript. The article was subject to the journal's standard procedures, with peer-review handled independently of this Editorial Board member and the research groups.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao H, Zhang J, Zhao J, Niu S. 2024. Genetic transformation in conifers: current status and future prospects. Forestry Research 4: e010 doi: 10.48130/forres-0024-0007

Genetic transformation in conifers: current status and future prospects

- Received: 11 December 2023

- Revised: 30 January 2024

- Accepted: 28 February 2024

- Published online: 21 March 2024

Abstract: Genetic transformation has been a cornerstone in plant molecular biology research and molecular design breeding, facilitating innovative approaches for the genetic improvement of trees with long breeding cycles. Despite the profound ecological and economic significance of conifers in global forestry, the application of genetic transformation in this group has been fraught with challenges. Nevertheless, genetic transformation has achieved notable advances in certain conifer species, while these advances are confined to specific genotypes, they offer valuable insights for technological breakthroughs in other species. This review offers an in-depth examination of the progress achieved in the genetic transformation of conifers. This discussion encompasses various factors, including expression vector construction, gene-delivery methods, and regeneration systems. Additionally, the hurdles encountered in the pursuit of a universal model for conifer transformation are discussed, along with the proposal of potential strategies for future developments. This comprehensive overview seeks to stimulate further research and innovation in this crucial field of forest biotechnology.

-

Key words:

- Conifer /

- Genetic transformation /

- Regeneration /

- Prospects