-

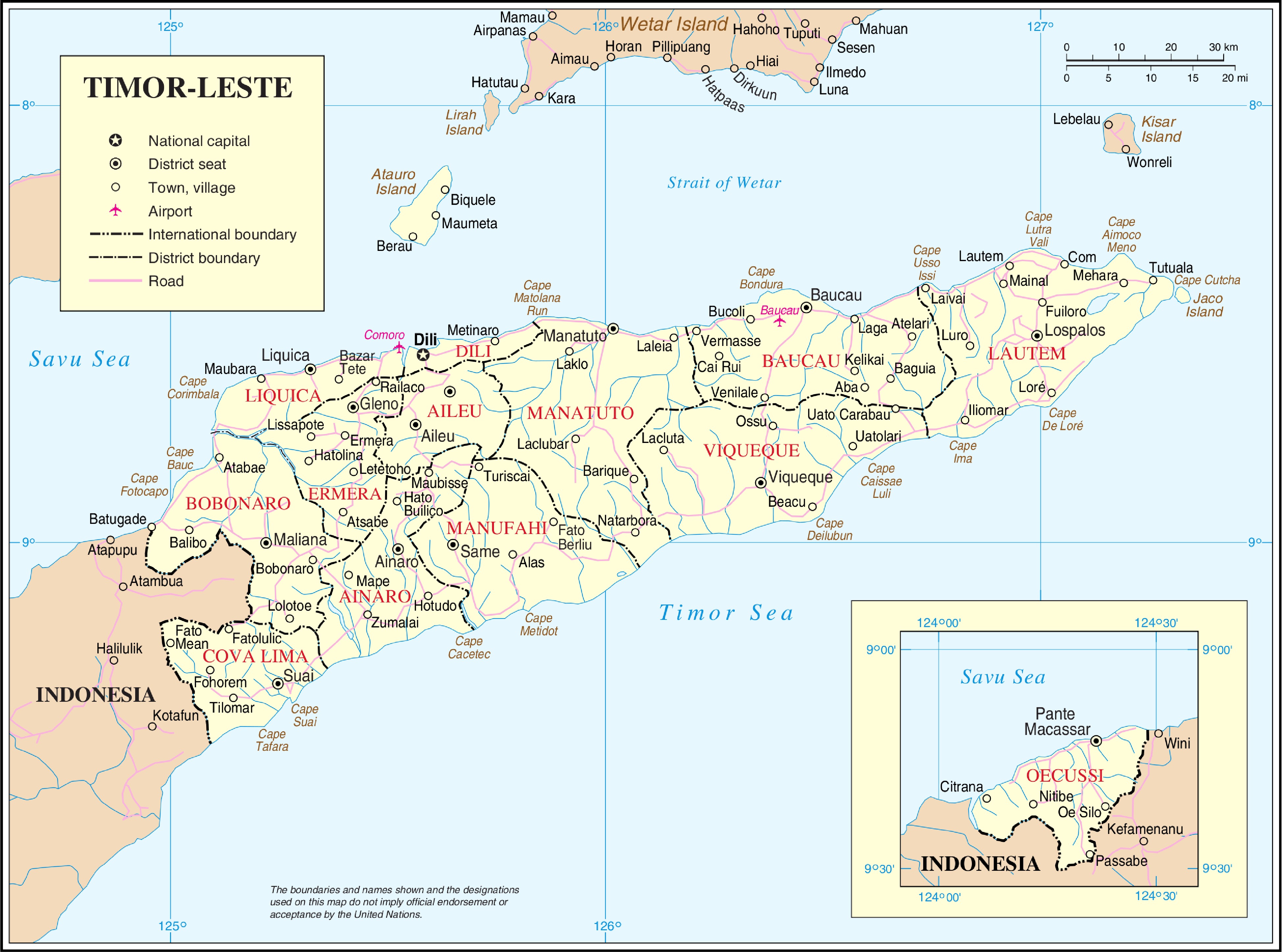

As the youngest of the 11 sovereign nations in Southeast Asia, Timor-Leste celebrated its 20th anniversary of independence in 2022 (Fig. 1). Despite two decades of intensive efforts for economic reconstruction by the local government and international aid agencies, indices of poverty and food insecurity remain high, causing low economic resilience. Food insecurity remains a pressing issue with a 10-year stagnating Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.606, which is well under the global average of 0.737[1]. Similar trends exist in the prevalence of undernourished people (one-third of the actual population, with 49% of children under five estimated to show signs of stunted growth)[2]. Although progress has been made to increase cereal productivity, total production still lies 45% lower than in 2010. This is leading to a decline in food availability in the country[3] and is inevitably crippling Timor-Leste's position as a net food importer. In line with this, the danger of 'hungry seasons'[4] is progressively exacerbated by climate change and its resulting erratic weather patterns that subsequently disrupt traditional crop cycles.

Figure 1.

Political map of Timor-Leste with 13 districts and main urban conglomerations[5].

As expected for small and mountainous islands like Timor, arable land is limited and consists of approximately 10.4% of the total country area or 155,000 hectares[6]. At present, maize (upland and hillsides) and rice (coastal plains and southern flats) are the main staple crops grown in a nearly 3-to-1 and 2-to-1 proportion in terms of area and production, respectively, and primarily for auto-consumption[7−9]. Crop productivity is low, with reports of 1−2 tonnes/ha for rainfed maize[7], and 1.5−3 tonnes/ha for rainfed and irrigated rice[8]. Therefore, Timor-Leste gravely underperforms compared to other small island developing states and low-income food-deficit countries in terms of agricultural productivity expressed as crop output per hectare[10]. With 70% of the population living in rural areas[2] and 60%−80% of households engaged in crop production[10,11], any sound development strategy underlines the need to address the modernization and sustainable intensification of local food production systems[10,12−14].

-

The tumultuous political past of Timor-Leste, which caused a severe lack of infrastructure and social and human capital, has put the country in a state of unreciprocated development[15]. This, in combination with the whimsical weather conditions and their non-volcanic mountainous features – both unfavourable for crop production, has made the agricultural sector of Timor-Leste one of the least developed in the world[10].

Nonetheless, the democratic government of this young nation has set out to address these issues with the support of international aid agencies. It continuously aims to increase the attention given to the agricultural sector, as made clear in the strategic development plan 2011−2030[16], where it embraced the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations[14]. In this plan, attention to improved agricultural land use and natural resource management was underlined as the best way to improve the livelihoods of the rural poor[12]. With this commitment, the government of Timor-Leste has worked to adjust and fine-tune its Agricultural Policy and Strategic Framework towards nutrition-sensitive, climate-smart agriculture and economically viable and sustainable agri-food systems[12]. An integral part of this framework states the need to reorient policy instruments to position 'agriculture as an enterprise' that stimulates the inclusiveness and participation of the rural population, particularly women and youth and public-private community partnerships.

Recognizing the need for a more integrated and tailored approach[13,15,17] has been pivotal in redirecting agricultural mechanization efforts in the country and creating a shift from importing large tractors and governmental service hire schemes to a scale-appropriate approach to sustainably intensifying rainfed farming systems[12]. The Agricultural Mechanization policy of 2018 (yet to be approved) includes phasing out agricultural subsidies of unsustainable heavy tillage equipment and pushing for the adoption of conservation agriculture practices, integrated soil fertility and nutrient management, and reduction of post-harvest losses on the farm. Promoting appropriate farm equipment suitable for specific agro-ecological conditions and diversified systems (e.g., hand tools and small hand tractors with zero-till implements) will address farmers' needs in improving productivity and operation time. Capacity building – on the correct operation of these tools and relevant post-harvest technologies – and targeting smallholder farmers will facilitate reducing labour pressure on women, create employment opportunities for rural youth, and strengthen the establishment of partnerships between public, private, community entities to develop the machine delivery and services value chain.

Traditional upland farming systems are predominantly of a shifting nature where slash-and-burn practices are common[9,14]. With 44% of the country consisting of slopes of over 40%[4,18], limiting deforestation and soil erosion is paramount, especially in flash-flood-prone areas. In addition, the growing population in rural areas reduces the time available for fallow periods and increases the extraction of wood for fuel[4,13,19]. Irrigated paddy rice systems have provided more food security in the southern flatlands, despite water scarcity not allowing more than one cropping cycle per year. Making matters worse, many irrigation canals remain damaged due to a lack of maintenance and repairs after flooding[4,7]. Further, unsustainable and intensive agricultural practices in the two dominant cropping systems are resulting in accelerated rates of natural resource depletion (18.6% of Gross National Income[1]) and environmental degradation. These practices include the inefficient use of farm inputs, lack of knowledge of good farming practices resulting in excessive or intensive land use, inadequate use of farm machinery, and lack of appropriate fertilizer management[12,15,17].

-

FAO's recently finalized the Technical Cooperation Programme, 'Support to Sustainable Agriculture Mechanization in Timor-Leste' (TCP/TIM/3701), worked to operationalize some of the priorities identified under the Agricultural Mechanization Policy of the East-Timorese government by enhancing the capacity of the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries (MAFF) and private sector support services to transfer new and improved production and post-harvest technologies and practices in terms of climate-smart agriculture and sustainable agriculture mechanization.

Main activities under this project involved: stocktaking of currently registered farm machinery; organizing and developing training programs for trainers and farmers on the use, operation and maintenance of scale-appropriate farm machinery (including on-farm production, post-harvest operations, and business and management skills); undertaking a survey and analyzing the information to understand the dynamics and characteristics of existing mechanization service providers and their business models; and supporting the establishment of mechanization service providers in the low- and up-lands.

Stocktaking on farm machinery was done by collected data from various sources, although reliable data from before 1997 is extremely difficult to come by, especially when looking at ancillary farm equipment or machinery beyond tractors. Hence, main sources used for this are FAOSTAT data available online, triangulated with published literature given preference to the most detailed reports[2, 17]. Additional information is collected from data reported in previous aligned international aid interventions over the past two decades, as could be found online[20] and from reports provided as reference material by MAFF during project implementation.

The training program was carried out during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic. In total, 16 participants received in-depth training (training of trainers or TOT) on the operation and maintenance of scale-appropriate machinery, enough to be able to support farmer trainings at the district level. The TOT participants included MAFF mechanization staff, private sector sales representatives, and vocational training center's teachers. The project also provided training on business skills for mechanization hire services to 20 civil participants.

Training at the municipality level (Bobonaro, Manufahi, Manatutu, Baucau, Viqueque, Covalima, Lautem, Aileu and Ainaro) reached: 193 (22 women) smallholder farmers trained in the operation and basic maintenance of machinery; 181 (nine women) operators, blacksmiths and metal workshop staff trained in the operation, maintenance and repair of machinery; 170 smallholder farmers trained in business development skills. Additionally, a group of 32 mechanization service providers from four different districts was selected and surveyed to understand the business model under which they operate, using semi-structured interviews.

The project supported nine smallholder farmers to become mechanization service providers. These small businesses provide rice and maize threshing and milling services in their communities for a fee, thereby generating extra income.

Information on inventory and services offered by the agricultural machinery enterprises and farm machinery shops was collected directly by the authors from a representative sample, through shops visits, review of shop catalogues and interviews with shopkeepers.

-

Access to extension services, labour utilization and agricultural mechanization is deemed to increase agricultural productivity[10]. In terms of modernizing farm systems, mechanization is regarded as a driving force for agricultural transformation[21]. Indeed, providing farmers with the right equipment to gain greater control in the production process enables them to mitigate adversity and ensure timely operations despite erratic weather. It allows pathways towards sustainably intensifying their production systems, supporting rural communities to meet the increasing global food demand[22]. Nonetheless, developing nations' attempts to accelerate the shift towards modern intensified systems through large tractor importation schemes that leapfrog the technological farm evolution have mostly failed[23,24], with Timor-Leste being no exception[10,12,15]. Yet, an appropriate choice of farm equipment that is tailored to field sizes, resource endowments and subsequent use of mechanization inputs can have significant effects on agricultural productivity[25,26]. This underlines the necessity of a well-planned and selective mechanization strategy that fits with the multiple objectives of sustainability, rentability and resilience[17,24]. In this sense, it is unsurprising that many of the tractors handed out in the earlier mechanization efforts could not be maintained, as can be seen in Fig. 2, resulting in queues of broken-down tractors in district mechanization centers with no hope of prompt repair[10,12].

Figure 2.

Hangar filled with tractors waiting for repairs (left) and farmers explaining that a pushcart multi-crop thresher he received years ago has been standing there, lacking spare parts to make it functional again (right).

Data on past and present farm machinery availability is difficult to come by, as the political instability and infrastructure loss have greatly hindered stocktaking after 1997. Combining information sourced from the literature and personal communication with government informants, including MAFF and the Secretary of State for Vocational Training and Employment (SEFOPE), has made it possible to sketch the situation (Table 1), but should not be taken at face value as this might wrongfully represent the situation on the ground. Indeed, the data provided offers mostly an insight on government efforts to allocate farm equipment across districts as received through different international aid interventions. The numbers provided to the authors might be unintentionally biased in this sense as the request aimed to gain a specific on ancillary smaller scaled equipment. For available tractors, both two-wheel and four-wheel tractors these numbers might be underestimated, although based on empirical experience on the ground, these numbers seem to fit the overall tendency on type and function of working equipment as found in the areas of intervention. Sales numbers from local distributors were not included, however, neither was a detailed survey of machine ownership carried out or found in literature.

Table 1. Past and actual registered farm machinery relevant to maize and rice production in Timor-Leste.

Equipment Year Foreign aid imports 1997 2020 2000−2001 2021 Tractors 4WT-Medium (40−70 HP) 59 145 50 4WT-Big (70−100 HP) 31 123 5 2WT-(8−12 HP) 276 477 468 Implements Field operations 4WT Combine 12 Moldboard plough 210 Disc harrow 7 Rice transplanter 15 Rotovator 12 Paddy harrow 90 Paddy leveller 30 Grain drill 30 2WT Rice transplanter 19 Power tiller 3 Roller crimper 50 Reaper 150 Postharvest Multicrop thresher 113 100 2 Rice mills 113 408 2 Maize mill 2 Dryer 10 Maize sheller 42 52 Transport Trailer 11 60 Source 2,26 (pers. comm. MAFF & SEFOPE*, 2019) 27 Delivered as part of the TCP *SEFOPE: Secretary of State for Training and Employment in Timor-Leste. Table 1 shows that while the availability of two-wheel tractors doubled, the number of inventoried four-wheel tractors tripled, corroborating the previous administrations' focus on large farming schemes. This increase is seemingly in line with tractorization rates during the Indonesian occupancy, registering on average a growth of eight tractors per year[2]. Nonetheless, at least half of these are standing idle due to a lack of maintenance and unreliable fuel supplies, as mentioned before and reported in the literature. This negligence, including ineffective asset and knowledge management systems and the lack of sense of ownership, might also explain why the many foreign aid importations and subsidized hand-outs reported in the literature[9,10,15] almost go unnoticed here. Table 1 presents information by JICA (2002) on the number of tractors and farm implements bought to support the mobile tractor brigade during the early reconstruction efforts, however the absence of spare parts dealerships and the complete lack of ownership by farmers during this period led to the eventual disuse of the machinery and the dissolution of the mobile brigade[12,27]. Some of those smaller engines and basic implements could be recovered if basic repair services were available, or at least be used as stock for second-hand spare parts in more remote localities.

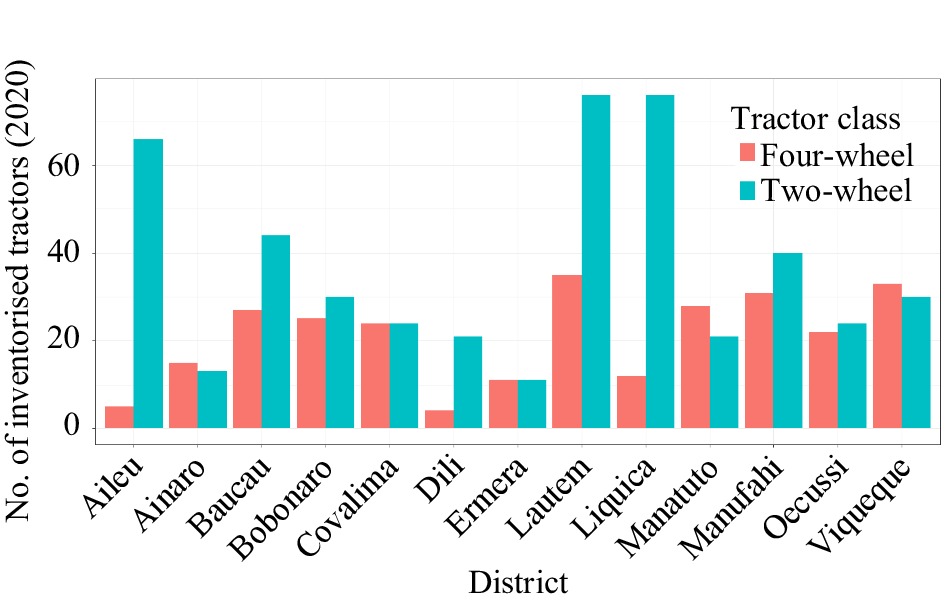

Figure 3 and the TCP/TIM/3701 activities show and confirm that four-wheel tractors are concentrated mainly in the rice-producing areas, including Lautem, Manufahi and Viqueque districts; in contrast, two-wheel tractors are evenly represented in all districts except for Ermera and Ainaro (MAFF, personal communication, 2020).

Figure 3.

Number of four-wheel tractors and two-wheel tractors allocated to MAFF mechanization centres at the district level (MAFF, personal communication, 2020).

While efforts to increase access and availability of tractors did not reach the desired potential due to the circumstances mentioned above, the Agricultural Mechanization Policy (2018) seemed able to pave the path towards private sector engagement in farm machinery supply. In contrast to earlier reports[17,27] on the existence of only a handful of spare parts dealers in Dili with virtually shelved parts in stock, a decade later, many hardware shops can be spotted in the capital city streets that sell small self-propelled post-harvest equipment and mini tillers with a basic set of farm implements (Fig. 4). Some operate in district capitals of more intensive farming areas (Table 2). However, local farm equipment manufacturers and specialized shops with a broader offering of on-farm operation implements remain hard to find, if not absent, as confirmed by one-to-one interviews performed during the TCP/TIM/3701. Only a dozen specialized enterprises could be identified at the national level; mainly early-adopter machine import/distributor companies and boutique shops resulting from successes from past foreign aid and development projects. Repair, maintenance, and service businesses for agricultural equipment are still painstakingly underrepresented.

Figure 4.

Several hardware stores in Dili offer small-scale farm equipment for land preparation and milling.

Table 2. Surveyed agricultural machinery enterprises and farm equipment shops with main activity and available inventory.

Name Type District Main activities/inventory Hero International Hardware Dili Farm equipment, domestic appliances and general retailer 2WT and mini-tiller and accessories, post-harvest mills, shellers and threshers Pt. Global Brother Hardware Dili Farm machinery and mechanical hardware store 2WT and mini-tiller and accessories, post-harvest mills, shellers and threshers Loja Marbella Hardware Dili Farm machinery and mechanical hardware store 2WT and mini-tiller and accessories, post-harvest millers, shellers and threshers Vinod Patel Construction Dili Home improvement: construction and gardening 2WT and mini-tiller and accessories, horticulture focused (USAID Avansa) Always Construction Construction Dili Construction materials and spare parts importer 2WT and mini-tiller and accessories, post-harvest mills, shellers and threshers KMANEK Agrikultura Boutique Dili Supplier for horticultural farm equipment and seeds (USAID Avansa) Limited availability of 2WT and mini-tiller, horticulture focused Boaventura Boutique Dili Vegetable seeds and agrochemicals 2WT with thresher and water pump but only under tender agreements ACELDA Distributor and

repair servicesBaucau Import of Agricultural machinery and equipment distributor 4WT, 2WT and mini-tiller and, to lesser extent, accessories Costa Motor Distributor and Hire services Baucau Farm machinery, equipment and spare parts shop 2WT and mini-tiller and accessories, post-harvest millers, shellers and threshers Longping High-Tech Distributor Manatutu Import of farm machinery, mainly in support of Chinese aid[15]

Rice Combine Harvesters, transplanters and seed drillsCladotia FU Hire services Dili Local hire services under production contracts with farmers 4WT with seeders and combine harvesters Bendix Service Maintenance Dili Car and tractor maintenance, farm hire services and mechanical workshop 4WT, 2WT and mini-tiler and, to lesser extent, accessories The survey for agriculture mechanization service providers that aimed to identify the providers' business models[28] revealed a highly informal and unarticulated form of entrepreneurship. Following[29], most service providers fell under the Model I category of individual farmer service providers who, after attending to their own agricultural mechanization needs, attend to the needs of other surrounding farmers and clients. All but a few respondents showed a clear business orientation. Confusion was demonstrated when reporting on operation costs without connection to the quantity and nature of delivered services. The survey and overall results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Main building blocks of the surveyed agriculture mechanization service providers during the TCP/TIM/3701.

Key partnerships ● Spare parts reseller and repair workshop

● Public scheme to provide the needed financingKey activities In-house maintenance Key resources ● Only one low-capacity machine for each service

● Operator(s)

● Shelter and tools to protect and maintain the machineryValue proposition Mechanization hire services:

● Maize and rice processing

● 2WD-powered tillage services (land preparation)Customer relationships ● Neighbouring farmers

● Family membersCustomer segments Small-scale farmers (less than 2 hectares of land) Delivery channels ● Word of mouth

● Processing at service provider‘s place on-demand

● Booking of the land preparation services directly with the MSPCost structure ● Main variable costs: fuel, maintenance, repairs

● Main fixed costs: operator salaryRevenue stream ● Service charged per hectare or per kg

● Likely not the main source of revenue -

The Agricultural Mechanization policy focuses on simple hand tools and small-scale motorized equipment like two-wheel tractors and their implements. It provides an opportunity to correct the mistakes of previous attempts to develop and mechanize the agricultural sector by providing modern and affordable solutions for many smallholder farmers[22,30]. Now, with a more established presence of hardware stores offering imported Chinese and Indonesian small-scale farm equipment, the scene is set to start bringing in a more comprehensive set of tools to mechanize rainfed productions systems in the country[31−33]. Nonetheless, many challenges still lie ahead as this requires a coordinated and integrated approach and a corresponding well-considered capacity building and investment plan throughout the agricultural commodity value chains.

First, the shift away from the one-size-fits-all approach where large tractors were imported to work in irrigated rice systems and build on economy of scale means that close attention should be given to the production conditions in small, dispersed fields of rainfed areas that typically range from 0.25 to 1 ha in size[7,9,10]. Sustainably intensifying these farmlands presents a steep learning curve and requires sustained technical assistance, capacity building and targeted or selective investments in order to generate systemic change and break through the risk aversion of many farmers in the long run[17,23,22]. Indeed, beyond the technocratic shift of decision-makers of the East-Timorese administration, attention must be given to long-term planning, consensus-building between governmental bodies and coherent policy implementation[34]. This includes thinking in terms of functional agri-food systems with proper regularizations for international and domestic trade of agricultural commodities[12], revising land tenure laws[7,10], and mobilizing subsidies schemes in the sector. Adequate import facilities for farm inputs and agricultural machines and capacity building of public officers and farm advisory professionals must be organized accordingly. This includes installing proper knowledge management systems that support the timely exchange of accurate information of agricultural research in response to farmers' needs[12,15,33,35]. To achieve sustainable mechanization in particular, intensive participatory approaches that empower farmers as a driver for change in response to early successes are needed[17,36], in combination with machinery demand creation and tailored business model development to stimulate rural entrepreneurship[21,29,31,37,38].

At first, this means that extensionists and locally engaged agents must be trained to embrace scale-appropriate farm machinery and re-educated on climate-smart agronomic practices, such as conservation agriculture, integrated farm input/crop management, post-harvest handling and adequate market linkages. As such, policymakers, farm development assistants and smallholder farmers themselves will need to start seeing agriculture as a business and shift their subsistence paradigm into a small commercial enterprise where costs and benefits must be accounted for. Indeed, these insights are essential to guide decisions and balance the shift in resource allocation upon investing in new farm equipment[39]. This knowledge gap, which is likely a legacy of the highly subsidized farm inputs strategy of the past decade, became particularly apparent during the training of farmers and MAFF machine operators undertaken in the TCP/TIM/3701. During the training, it was clear that participants struggled when discussing machine calibrations and field efficiency or fuel consumption calculations. It has been proven in the past that in order to retire from traditional farming systems such as the detrimental slash-and-burn, sustainable intensification strategies such as minimal tillage, crop rotations, cover cropping and surface cover retention, integrated fertilizer management[10,40], and yield-enhancing technologies including improved seeds[41] have to be considered together with mechanization as a basket of technology options[42].

For agricultural mechanization to be sustainable, the agronomic limitations of a country's fragile micro-climates must be understood, and work must be done to overcome the economic constraints of acquiring innovative scale-appropriate equipment[24,31]. Innovative financial services and ownership models must be designed and evaluated in pair with the socio-economic context of each community where poverty indices are high, non-commercial farming prevails, and traditional land law is still in place[29,43]. Business models in the form of leasing schemes between farmers and private sector providers or joint ventures between machine importers/manufacturers and professional service providers are nowadays often suggested to diminish dependency on subsidy schemes[17,29,38,44−46]. Certainly, professionalizing specialized farm machinery hire services could address multiple aspects of the problems in Timor-Leste; it can stimulate rural entrepreneurship and the concept of agro-businesses, unburden smallholder farmers in terms of having to make a risky upfront investment, and kindle the much-needed sense of ownership of the farm equipment as a production asset[31,47,48].

Finally, the underdeveloped state of the national infrastructure of Timor-Leste might be another significant limiting factor to increasing its agricultural productivity[7,13]. Failure to maintain the national roads network may cause a problem in propelling agricultural mechanization. Rural access index (RAI) estimates for 2015 indicate a 40% increase (since 2001) of people living at a distance beyond 2 km from an all-weather good condition road[49], and 65% of farmers with market participation must walk 6 km on average to access these roads[10]. Limited transnational food transportation, inadequate grain storage facilities[12,50] and poor national telecommunications systems that hinder timely access to market information erode the options for farmers to commercialize their produce at competitive prices either in local or regional markets. Setting up a solid spare parts value chain and last-mile delivery system for recommended farm machinery will also have to overcome these issues for the mechanization policy and its implementation to become successful.

Opportunities

-

Despite the adversities, the East-Timorese government's eagerness and openness to adjust plans and adopt new perspectives bring about opportunities to overcome the many challenges the agricultural sector faces. With adequate support and consistent institutional training and investment in the development of human capital, government officials and extensionists can play a pivotal role in bringing about change[10,17], even though the publicly organized tractor hire schemes of the past, either via mobile brigades or MAFF mechanization centres (MCC), failed. As mentioned, this was mainly related to its inherent subsidized nature that does not consider the cost of machine depreciation and maintenance or scale-appropriate solutions. Nonetheless, the MCCs currently represents the focal point of available talent and expertise in the operation and maintenance of more specialized farm machinery and provide a physical space to organize training and demonstrations in close vicinity of rural farming communities in each district. In this sense, MCCs can have a double role: to make ongoing mechanization efforts more sustainable, namely in the promotion of scale-appropriate mechanization throughout the cropping cycle -from land preparation to (post) harvesting-, and to create awareness of the efficient use of farm inputs, including fuel, seed, agrochemicals (e.g. fertilizer, pesticides), land and time. Instead of maintaining a fleet of unusable large tractors, some centers could be converted into demonstration sites where field experiments are conducted to show farmers the correct use of different scale-appropriate farm tools that facilitate the implementation of climate-smart farming practices and serve as a local reference and a broker of positive change[51]. Following this, the MCCs can be set up as an innovation platform taking advantage of the skillset of local staff. However, care must be taken to allow input and guidance from key stakeholders like local farmers and farmer associations to guide research or experiment priorities[52,53]. MCC operators that participated in the training course of the TCP/TIM/3701 showed to be quite knowledgeable in the mechanical aspect of tractors maintenance but unanimously expressed that the time-consuming nature and complex logistics of attending work on farmers' fields put an unmanageable strain on available resources. Operating as a research station or living labs in a more controlled environment or at scale down to manage a limited amount of farmer fields could resolve this issue without losing the social capital[52,54].

Following a pathway that stimulates rural entrepreneurship and smallholder agribusinesses will also provide an entry point for the scaling of sustainable mechanization[29]. Farmers that understand better the 'finance of the farm' will be able to make informed investment trade-offs between the choices of new sustainable intensification technologies and will support the development of specialized smallholder farm hire services. Indeed, breaking away from the more informal farmer-led service provider models, which are less conducive to scaling, and setting up local entrepreneur machine services providers will enable subsistence farmers to take advantage of modern and scale-appropriate machinery at a manageable cost instead of having to make the often-impossible purchase of their own machine[29,31,44]. In fact, despite the seemingly below-par RAI, rural road density is significantly higher in Timor-Leste compared to other mountainous countries, like Nepal and Lao People's Democratic Republic[49], favouring the manoeuvring of smaller farm equipment in rural communities. Similar to Nepal or Bangladesh, using two-wheel tractors with small trailers attached could enhance rural mobility, facilitating the transport of produce to local markets and hauling farm inputs to homestead[55,56].

Additionally, fee-for-service businesses can give a place for the 17,000+ youth entering the labour force annually[7], especially as the growing rural population will only put more pressure on the already sparse land if all were to become farmers. Technical training of younger generations will have to be considered a priority to achieve this. More so, vocational training curriculums that focus heavily on sustainable farming principles, farm economics and business administration, including rural supply chain management and mechanics, should become the norm to avoid future generations repeating past mistakes and achieve the government's goal under the Agricultural Mechanization Policy[12]. The expansion of mobile networks and digital tools can also attract youth as data curators or knowledge managers and support the professionalization of a range of extension and farm advisory services[57]. These could encompass client acquisition and planning of farm machinery service delivery[44,58,59].

In many family farms in the developing world, women tend to perform high-drudgery agricultural tasks, including land preparation, transplanting, weeding and post-harvest activities, like shelling and threshing grains[60−62]. At the same time, women in these rural households decide on family consumption expenditures[63] and are likely to invest more of their earnings in the family's well-being, including health and nutrition[63]. The role of women in rural economies is, therefore, essential in terms of food security[64,65]. With this in mind and based on the promising results from the Hindu Kush Himalayan region (with similar socio-technical constraints as Timor-Leste) where development interventions empowered women as agri-entrepreneurs offering custom hire services of farm machinery[62,66−68], it becomes clear that women are a force to be reckoned with to ensure sustainable mechanization. Since women play a central and complementary role in decision-making on and off the farm, actively involving them in the process of creating awareness of sustainable farm mechanization at the community level and designing machine packages around women's tasks on the farm, to avoid the risk of increasing womens burdens due to the unforeseen shift in work distribution in the household is essential to make progress[60,63,68−70]. Moreover, mechanizing post-harvest activities and food processing can provide interesting value-adding entry points in Timor-Leste. This would align with the revisited Agricultural Policy and Strategic Framework that aims to stimulate local agri-food value chains and farmer-market participation. At least for this, hardware stores are currently prepared to manage an increased demand for threshers, mills and other small food processing appliances.

-

Achieving sustainable agricultural mechanization in developing nations is already a complex task, making the challenge more defying for a young democratic republic like Timor-Leste situated on a remote, small, mountainous island in the Asian Pacific. Nonetheless, being a country struggling with a high incidence of food insecurity and rural poverty, the considerable benefits of farm mechanization cannot be ignored in the urgent need to uplift one of the least developed agricultural sectors in the world.

In the early aftermath of a promising change of direction for agricultural development made by the East-Timorese administration and at the end of a technical cooperation programme of FAO to support the initial implementation of the government's Agricultural Mechanization Policy, the work at hand aims to present the current state of agricultural mechanization in the country as well as an overview of the main causing factor leading to this situation. More so, in retrospect of the 20-year effort of economic reconstruction that shows a slow recovery from severe political instability, this work attempts to compile and present all relevant, albeit limited, information on the topic and serve as a reference point for future actions to enhance the sustainability of agricultural mechanization efforts and, with it, ensure positive change in agricultural productivity.

For any policy change to be effectively implemented, parallel investment and coordinated actions are needed at first, as well as assuring continuity in governance and leadership priorities and development agendas that align with private sector interests[34]. For this, a comprehensive and broad-spectrum overview of challenges and opportunities is given, with necessary reflections on experiences from other countries in similar conditions and lessons learned from mechanization initiatives globally. Conclusively, and after thoroughly exploring the facts, it appears that scale-appropriate mechanization can offer a series of viable solutions to the problems encountered when packaged in the suitable socio-technical bundles and with innovative approaches[71]. The lack of attention to this resulted in a situation often found in developing African countries, where many imported farm equipment lies broken down in outdated public-led farm mechanization and extension centers. In Timor-Leste, progress has been made to stimulate retail stores in the main urban conglomerations that offer small land preparation and post-harvest equipment. Still, retailers that supply spare parts and enterprises that deliver maintenance or on-farm machinery services remain underdeveloped. Market participation in selling irregular produce surpluses and food processing businesses also remain largely informal and have limited added value. The failure to maintain, let alone revitalize national infrastructure, is at least partly why these are lagging.

There is a clear need to reorient key government dependencies, where the MAFF mechanization centers could play a critical role in changing the subsidy-and-subsistence farming paradigm into small rural enterprises that understand the need for precision application of farm inputs and the role of context-specific tools as essential production assets. Setting up living labs in coordination with the reform of vocational training curricula around climate-smart, sustainable intensification principles and farm economics are needed to complement these centers and assure the future development of qualitative and effective professional farm advisory and extension services.

While the latter can complement this, thought should simultaneously be put into the design and development of business and finance models around farm mechanization, where on-farm and post-harvest service provision can create much-needed job opportunities for the fast-growing East-Timorese rural youth and reduce the pressure on land and labour availability, especially for women. The application of digital farming tools should also be considered from this perspective. Also, the dense rural road network can create opportunities for travelling service providers and rural transportation businesses using small, motorized equipment.

Recognizing the role of women in rural communities and the household expenditure decision-making process is essential to reach a scaled impact on farm mechanization. This role underlines the need for intensive and inclusive farmer participation in the rollout of targeted mechanization solutions. Finally, traditional land laws, import facilities and tariffs, and business registration systems must be adjusted accordingly, in addition to elaborating adequate financial inclusion strategies and aligned private sector investment.

Much work is yet to be done. But if the East-Timorese people collectively succeed in addressing these highly intermixed challenges, their strategy could well serve as a roadmap for smallholder farmers and developing nations elsewhere in the world.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Van Loon J; data collection: Van Loon J, Flores Rojas M; analysis and interpretation of results: Van Loon J; draft manuscript preparation: Van Loon J, Flores Rojas M. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to subsets of presented data being derived from internal communications with East-Timorese government officials and FAO consultants, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

This work was developed building on the findings of the FAO-funded Technical Cooperation Programme 'Support to Sustainable Agriculture Mechanization in Timor-Leste (TCP/TIM/3701)' and was made possible with the support of the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries (MAFF) of Timor-Leste. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the donors or collaborators. The authors extend their gratitude to Raphy Favre, Paula Lopes da Cruz, Alcino Sarmento, Mathieu Faujas, Paolo Correia, CNEFP and Simão Tito Barreto, Scott Justice and Maria Odete do C. Guterres, Ina Maza Villalobos and other colleagues that provided additional insights and data.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

VAN LOON J, FLORES ROJAS M. 2024. Sustainable agricultural mechanization in Timor-Leste: status, challenges and further action. Circular Agricultural Systems 4: e008 doi: 10.48130/cas-0024-0006

Sustainable agricultural mechanization in Timor-Leste: status, challenges and further action

- Received: 04 November 2023

- Revised: 13 December 2023

- Accepted: 09 February 2024

- Published online: 17 April 2024

Abstract: Despite many efforts over two decades of independence, Timor-Leste's cereal production and agricultural productivity have decreased dramatically, reflected by high food insecurity and rural poverty. This paper analyses the country's current agricultural mechanization efforts to guide future actions that aim to stimulate growth through sustainable mechanization. We combined information from scientific publications, governmental and international cooperation communications, and data collected during field missions to assess the situation. Our study provides recommendations to reverse a failed tractorization campaign and presents a comprehensive overview of a strategy, in alignment with a proposed and renewed national agricultural mechanization policy, that would enable the modernization and sustainable intensification of current food production systems in a nutrition-sensitive, climate-smart, economically viable, and gender-inclusive fashion. The recommendations suggest a focus on scale-appropriate solutions that respond to upland smallholder farmers' capacities and consider good rural transport options, with the first steps to redirect the situation already taken through a technical cooperation program between FAO and the Ministry of Agriculture. Beyond this, a reform of the current government mechanization hire schemes is needed: integrated approaches, as found from business model analyses and training exercises during field missions, are needed, that entail context-specific solutions for targeted rural communities, with special attention given to participatory extension, inclusive co-validation of technologies, and private sector-led business model development around mechanization service delivery. Finally, the authors hope the presented way forward can serve as a roadmap for smallholder farmers and developing nations in similar conditions elsewhere in the world.