-

In intensive and large-scale production of the pig industry, environmental factors play a vital role in the healthy production of pigs. There is growing evidence that heat stress caused by a hot and humid summer can negatively affect boar semen quality and fertility[1,2], resulting in decreased sperm motility, testosterone disturbances, and reduced ejaculation volume[3], which in turn led to economic losses for the pig industry. Animals suffer from heat stress when the ambient temperature rises beyond their thermal comfort zone (18−23 °C)[4]. Studies have shown that spermatogenesis is impaired in large white boar at ambient temperatures above 29 °C[5]. In addition, heat stress leads to downregulating steroid acute regulatory protein (Star) genes and protein in animals, reducing testosterone synthesis[6]. It is well known that testosterone, a steroid hormone, is vital in promoting sperm production and maintaining testicular function[7]. Therefore, it is urgent to solve the problem of impaired semen quality in boars under a heat-stress environment.

Numerous recent studies have demonstrated a strong link between gut microbiota and semen quality. Studies have reported that the quality of sperm in dogs was significantly improved when commensal Lactobacillus spp. was added to their diet[8]. Prenatal exposure to dibutyl phthalate in female rats and transplantation of the fecal microbiota of their male offspring into normal rats caused poor semen quality and testicular damage in the normal rats[9]. Busulfan-induced damage in sperm can be alleviated by transplantation of gut microbiota regulated by alginate oligosaccharide into a mouse model treated with busulfan[10]. Ding et al.[11] transplanted the fecal microbiota of high-fat diet mice into normal diet mice and found that the gut microbiota of normal diet mice was altered, and endotoxemia occurred, resulting in sperm damage. In addition, there is growing evidence that the gut microbiota regulates androgen production and metabolism[12,13].

As a conditionally essential amino acid, L-Arg can alleviate the damage caused to animals by a high-temperature environment[14,15]. Studies have shown that L-Arg can alleviate heat stress-induced gut damage in rats, promote the expression of gut-tight junction proteins, and protect the gut barrier function[16,17]. After L-Arg injection during egg breeding, the chicks increased in Lactobacillus in the cecum. At the same time, the number of Escherichia coli decreased[18]. In mouse models of colitis, supplementation with L-Arg can alleviate inflammation by restoring the presence of Bacteroides and overall microbial diversity[19]. After adding L-Arg to the diet of Qingyuan partridge chickens, Firmicutes, which contains a variety of beneficial bacteria, was increased. In contrast, Proteobacteria, which contained various pathogenic bacteria, was reduced[20]. Thus, L-Arg can effectively regulate the gut microbiota. In addition, studies have shown that L-Arg can also alleviate damage to boar sperm caused by heat stress[21] and increase serum testosterone levels in mice after heat treatment[22]. The gut is a key part of L-Arg metabolism because the gut microbiota and different gut microbiota compositions lead to differences in the body's arginine metabolism[23]. These studies have shown that L-Arg positively affects gut microbiota and semen quality.

In this study, heat-stressed boar was used as a model during hot summer months and the changes in boar semen quality and fecal microbiota were analyzed to explore whether there was a correlation between semen quality and fecal microbiota after adding 0.8% or 1.6% L-Arg to its diet.

-

L-Arg (CAS: 74-79-3; Purity > 99%) and L-Ala (CAS: 56-41-7; Purity > 99%) were purchased from Jiangsu Yanke Biological Engineering Co., Ltd (Jiangsu, China); KCl (CAS: 7447-40-7, Purity > 99.5%) was purchased from Nanjing Maibo Haocheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Nanjing, China).

Experimental design

-

The experiment was conducted from July to August 2021 in the boar house of a company in Huaiyin City, Jiangsu Province, China. The barn was cleaned, immunized, and disinfected according to the usual procedure. The barn lights are turned off after eating, allowing the pigs to lie down and rest. The boar house adopts positive pressure ventilation and a single-pen, single-pig management mode. A total of 15 boars of similar day age (large white, about 480 d of age), body condition, and semen quality (Table 1) were selected in this experiment and randomly divided into three groups, with five boars in each group. The experimental boars were given free access to water and fed regularly. They were fed at 9:30 and 16:30 every day, and each feeding was 1.25 kg. The boars were supplemented with 0.0%, 0.8%, or 1.6% L-Arg (w/w). L-Ala was used to maintain the nitrogen balance of each experimental group's diet. The groupings are as follows: Control group (basal diet + 3.2% L-Ala), 0.8% Arg group (basal diet + 0.8% L-Arg + 1.6% L-Ala), 1.6% Arg group (basal diet + 1.6% L-Arg). The experiment lasted four weeks. Semen quality was measured, and semen and fecal samples were collected weekly during the experiment. The boar basal diet is shown in Table 2. During the experiment, temperature and humidity recorders were placed about 2 m from the ground in the boar house's front, middle, rear, left, and right positions. The temperature and relative humidity in the boar house were recorded at 7:00, 11:00, and 17:00 daily.

Table 1. Semen quality of boar by four successive tests before the experiment.

Item Control 0.8% 1.6% Semen volume (mL) 392.40 ± 27.93 382.40 ± 44.72 377.40 ± 21.22 Sperm motility 0.49 ± 0.02 0.54 ± 0.02 0.54 ± 0.04 Sperm density (× 108/mL) 3.30 ± 0.48 3.60 ± 0.44 4.80 ± 0.97 Abnormal sperm rate (%) 28.20 ± 3.45 30.30 ± 2.64 25.20 ± 4.33 Functional sperm (× 108/mL/ejaculate) 658.10 ± 138.99 714.70 ± 88.28 704.80 ± 81.95 Total sperm

(× 108/mL/ejaculate)1326.40 ± 246.99 1319.40 ± 135.01 1346.00 ± 185.60 Sperm motility is indicated by a grading scale (0.0−1.0), the results are expressed as Mean ± SEM. p > 0.05, n = 5. Table 2. Composition and nutrient levels of experimental basic diet (as-dry basis).

Ingredient Percentage Corn 30.58 Wheat 20.00 Barley 30.00 Soybean meal (43%) 6.97 Sunflower meal 5.79 Fish meal 3.00 Calcium hydrogen phosphate 0.58 Limestone 1.51 Sodium chloride 0.28 Lysine sulfate (70%) 0.49 Threonine (98%) 0.06 Tryptophan (25%) 0.02 Choline chloride (60%) 0.12 Premix* (0.6%) 0.60 Total 100.00 Nutrient levels** Digestive energy (kcal/kg) 3162.00 Crude protein 15.50 Crude fat 2.40 Crude fiber 3.80 Neutral detergent fiber 14.26 Ca 0.90 Total phosphorus 0.56 * Premixes are provided for each kilogram of diet: 5000 IU vitamin A; 1000 IU vitamin D3, 48 mg/kg vitamin E; 2.5 mg/kg vitamin K; 4.8 mg/kg vitamin B2; 3.2 mg/kg vitamin B6; 7.5 mg/kg niacin; 88 mg/kg iron (ferrous sulfate); 20 mg/kg copper (copper sulfate); 90 mg/kg zinc (zinc oxide); 0.3 mg/kg selenium (sodium selenite). ** Nutrient levels are calculated values. Scrotal surface temperature measurement

-

Scrotal surface temperature was measured after the boars had stood for at least 15 min and once a week during the experiment. The temperature measuring instrument is a non-contact infrared forehead temperature gun (Lepu lfr20b, China).

Sample collection

-

Semen collection personnel use the hand-held method to collect semen. Before semen collection, the boar's abdomen was cleaned with wet and dry towels to prevent semen contamination. A disposable semen collection bag was placed in the semen collection cup that had been preheated at 37 °C and covered with a layer of sterile filter paper to filter the colloidal substances in the semen. After the semen collection was completed, the semen quality was detected immediately, and 10 mL of semen was collected for subsequent index detection.

The fresh feces of the experimental boars were collected from 7:00−9:00 daily. The feces should not touch the ground as much as possible to prevent the ground or urine from contaminating the feces. If they touched the ground, disposable gloves were used to peel off the outer layer. About 50 g of fecal samples were collected, placed in ziplock bags, and stored at −20 °C for future use.

Semen quality analysis

-

Analysis was performed using computer-assisted sperm analysis (CASA) and specific analysis software (Magavision, Magapor, Zaragoza, Spain) to assess sperm motility, abnormal rate, and density. Sperm motility was observed under a microscope. The collected semen was placed in a constant temperature water bath at 37 °C, and 50 µL semen samples were taken and placed on a glass slide pre-warmed at 37 °C, covered with a covered glass, and observed under a microscope. Five microscopic fields were randomly taken from each sample to record sperm motility. One hundred µL of semen sample was added to 900 µL 6% potassium chloride solution to dilute and mix. Ten µL of the mixture was taken, placed on a pre-warmed slide glass at 37 °C, and covered with a cover glass. Five microscopic fields were randomly selected to record sperm density and deformity rate. Total sperm count and effective sperm count were calculated using the formula: Total sperm count = Semen volume × Sperm density; Effective sperm number = Semen volume × Sperm density × Sperm motility[14].

Semen antioxidant and damage detection

-

After centrifugation of semen samples at 1,000× g, seminal plasma was stored in 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes for future use. After gently washing the sperm twice with phosphate buffer, the sperm was stored in a 200 μL EP tube. Total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC, A015-2-1, CV = 1.2%), total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD, A001-3-2, CV = 5.50%), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-PX, A005-1-2, CV = 3.56%), and catalase (CAT, A007-1-1, CV = 1.7%) were measured. Malondialdehyde (MDA, A003-1-2, CV = 2.3%) content is measured as an indicator of sperm damage. Sperm samples were lysed and homogenized by RIPA lysis buffer, centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 15 min, and the supernatant collected for MDA detection. The seminal plasma and sperm detection indicators were measured by kits purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China), and the test operation process was carried out strictly following the instructions.

Detection of testosterone in feces

-

0.75 g of sample was placed into a 10 mL centrifuge tube, 5 mL of 90% methanol solution added, shaken for 1 min, placed in a 60 °C water bath for 20 min, and centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was taken and stored at −20 °C for future use. Testosterone was measured using a porcine testosterone ELISA kit (H090-1-1, Jian Chen, Nanjing, China), and the specific operation steps were carried out according to the instructions.

16S rRNA gene sequencing

-

According to the gene sequencing procedure, total genomic DNA was extracted from all fecal samples to check its purity, concentration, and integrity (methods: NanoDrop2000 and agarose gel electrophoresis). Then the V3-V4 hypervariable region was amplified with primers 338F (5'-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3'), 806R (5'-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3'). Twenty seven cycles were performed at an annealing temperature of 55 °C. The sample result code is A after the pre-test, indicating that the target band size of the PCR product is correct, the concentration is appropriate, and subsequent tests can be carried out. After the pre-experiment, the formal PCR experiment was carried out using TransGen AP221-02: TransStart Fastpfu DNA Polymerase, 20 μL reaction system. PCR machine: ABI GeneAmp® model 9700. Sequences with 97% similarity were clustered into the same operational taxonomic units (OTUs). The α diversity indices, including observed species, ACE, Chao, Shannon, and Sobs indices, were calculated using QIIME (Version 1.9.1) to analyze the complexity of species diversity for each sample. The β diversity was analyzed through principal coordinates analysis (PCoA), non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS), partial least squares discriminant analysis, and hierarchical clustering tree to visualize differences in species complexity among samples. The PCR products were used for library construction, and then second-generation sequencing was carried out on the gene sequencing platform of Shanghai Meiji Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). All sequencing data were submitted to the NCBI database, accession number PRJNA937596. The sequencing data were all analyzed on the Shanghai Meiji Biotechnology Co., Ltd website.

Data statistics and analysis

-

After collating the data using GraphPad Prism 8.0, the effects of L-Arg levels, time points, and their interactions were analyzed by Two-way ANOVA analysis. Data results are expressed as mean ± SEM, with p < 0.05 indicating a significant difference and p < 0.01 indicating a very significant difference. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to quantify the degree of linear relationship between variables. The results with a p-value < 0.05 were defined as significantly different.

-

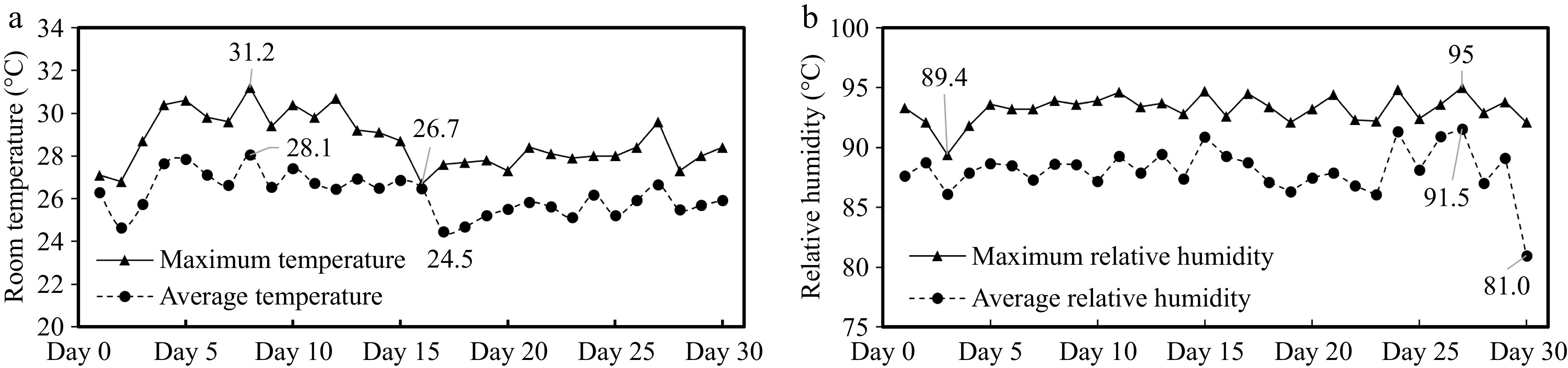

During the experimental period, the maximum temperature in the boar house was in the range of 26.7 to 31.2 °C, and the average daily temperature in the boar house was in the range of 24.5 to 28.1 °C (Fig. 1a). The maximum relative humidity was in the range of 89.4% to 95%. Moreover, the average relative humidity was 81% to 91.5% (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

Analysis of temperature and humidity change in the boar room. (a) Room temperature. (b) Relative humidity.

Changes in scrotal surface temperature

-

Adding 0.8% and 1.6% L-Arg to the diet did not affect the scrotal surface temperature of the experimental boars (Table 3).

Table 3. Analysis of scrotal surface temperature changes.

Control 0.8% L-Arg 1.6% L-Arg Week 1 32.45 ± 0.25 32.18 ± 0.35 31.64 ± 0.28 Week 2 30.45 ± 0.31 30.14 ± 0.39 29.82 ± 0.38 Week 3 31.86 ± 0.36 31.94 ± 0.34 31.28 ± 0.39 Week 4 31.05 ± 0.29 30.50 ± 0.22 30.65 ± 0.22 Scrotal surface temperature, °C, the results are expressed as Mean ± SEM. n = 5. Changes in boar semen quality after dietary arginine supplementation

-

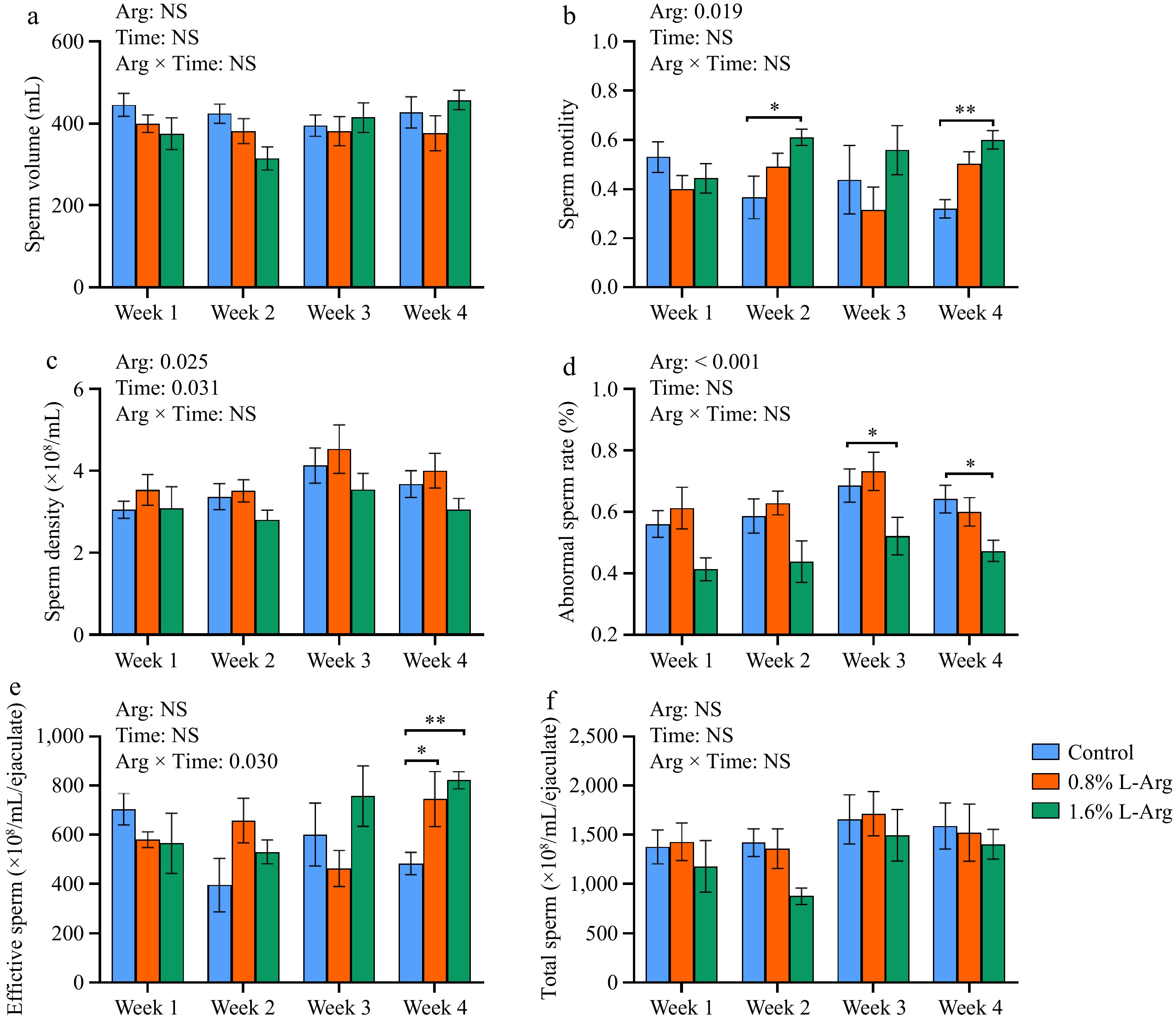

Adding L-Arg had different effects on sperm motility, abnormal sperm rate, effective sperm count, and total sperm count. In terms of semen volume, there was no significant difference between the three groups (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2a). In terms of sperm motility, the sperm motility of the 1.6% group was significantly higher than that of the control group at both Week 2 and Week 4 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2b). In terms of sperm density, there was no significant difference between the three groups (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2c). The abnormal sperm rate of the 1.6% group was significantly lower than that of the control group at both Week 3 and Week 4 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2d). The effective sperm of the 0.8% and 1.6% groups was significantly higher than that in the control group at Week 4 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2e). In terms of total sperm, there was no significant difference between the 0.8% and 1.6% groups compared to the control group (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2f). There is an interaction of Arg × Time in the effective sperm (p = 0.03).

Figure 2.

Effect of dietary L-Arg supplementation on boar semen quality. (a) Semen volume. (b) Sperm motility. (c) Sperm density. (d) Abnormal sperm rate. (e) Effective sperm. (f) Total sperm. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01.

Antioxidant indicators of semen

-

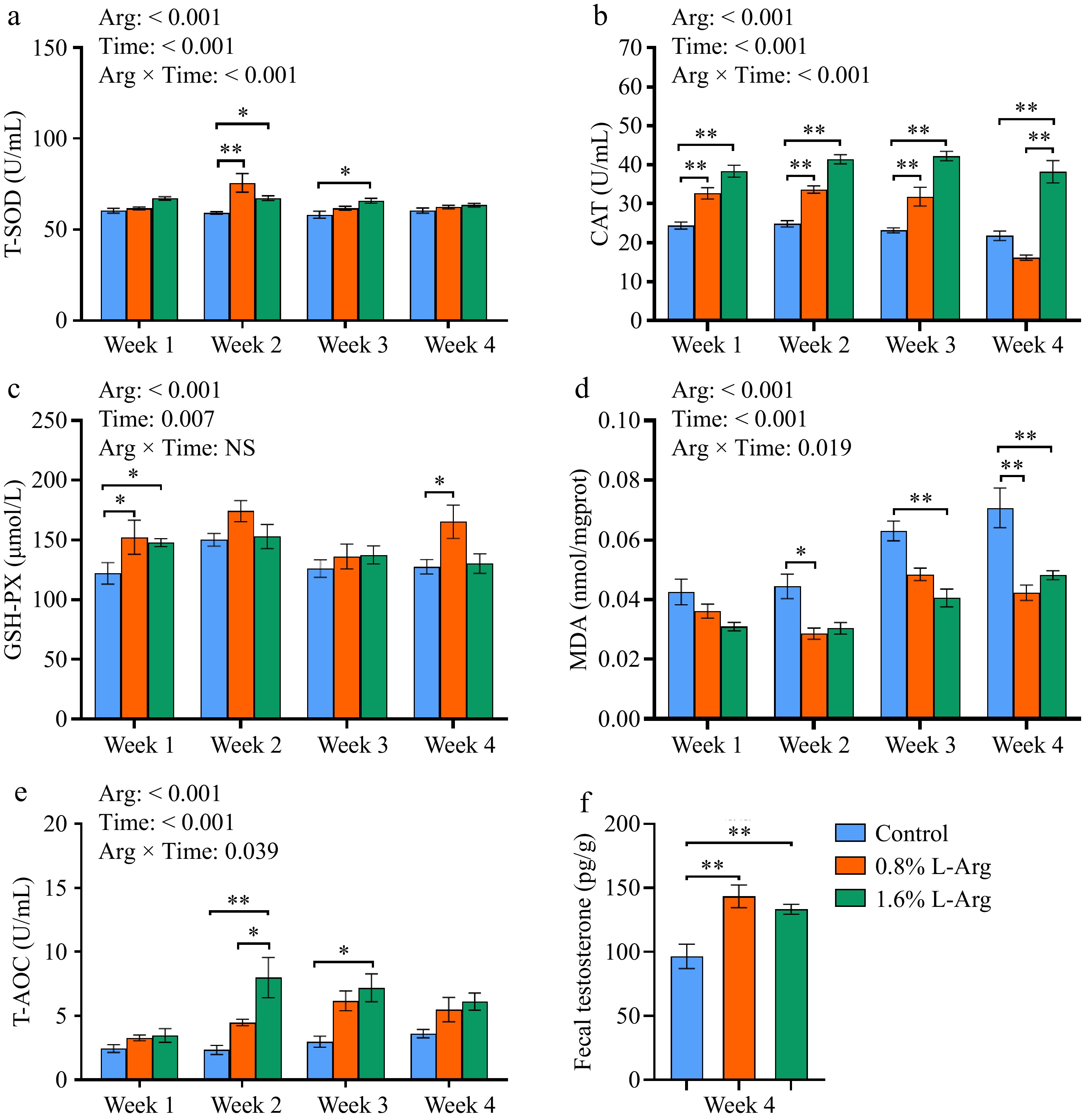

Dietary supplementation with L-Arg enhances the antioxidant capacity of boar semen. At Week 2, both the 0.8% and 1.6% groups significantly increased T-SOD levels in seminal plasma compared to the control group (p < 0.05). At Week 3, the 1.6% group significantly increased T-SOD levels in seminal plasma compared to the control group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3a). In Week 1, Week 2, and Week 3, the CAT level of the 0.8% group was significantly higher than that of the control group (p < 0.01). In Week 1, Week 2, Week 3, and Week 4, the CAT levels of the 1.6% group were significantly higher than those of the control group (p < 0.01); however, in Week 4, the CAT level of the 1.6% group was also significantly higher than that of the 0.8% group (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3b). At Week 1, the GSH-PX levels of the 0.8% and 1.6% groups were significantly higher than those of the control group (p < 0.05). At Week 4, the GSH-PX level of the 0.8% group was significantly higher than that of the control group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3c). In Week 2 and Week 4, the sperm MDA content of the 0.8% group was significantly lower than that of the control group (p < 0.05). In Week 3 and Week 4, the sperm MDA content of the 1.6% group was significantly lower than that of the control group (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3d). In Week 2 and Week 4, the T-AOC levels of the 1.6% group were significantly higher than those of the control group (p < 0.05). In Week 2, the T-AOC level of the 1.6% group was significantly higher than that of the 0.8% group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3e). At Week 4, fecal testosterone levels were significantly higher in the 0.8% and 1.6% groups than that of the control group (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3f). T-SOD (p < 0.001), CAT (p < 0.001), MDA (p = 0.019), and T-AOC (p = 0.039) have an Arg × Time interaction.

Figure 3.

Effects of dietary supplementation of L-Arg on the antioxidant capacity of semen and fecal testosterone. (a) Levels of T-SOD in seminal plasma. (b) Levels of CAT in seminal plasma. (c) Levels of GSH-PX in seminal plasma. (d) MDA content in sperm. (e) Levels of T-AOC in seminal plasma. (f) Fecal testosterone content at week 4.

Analysis of Alpha and Beta diversity of boar fecal microbiota

-

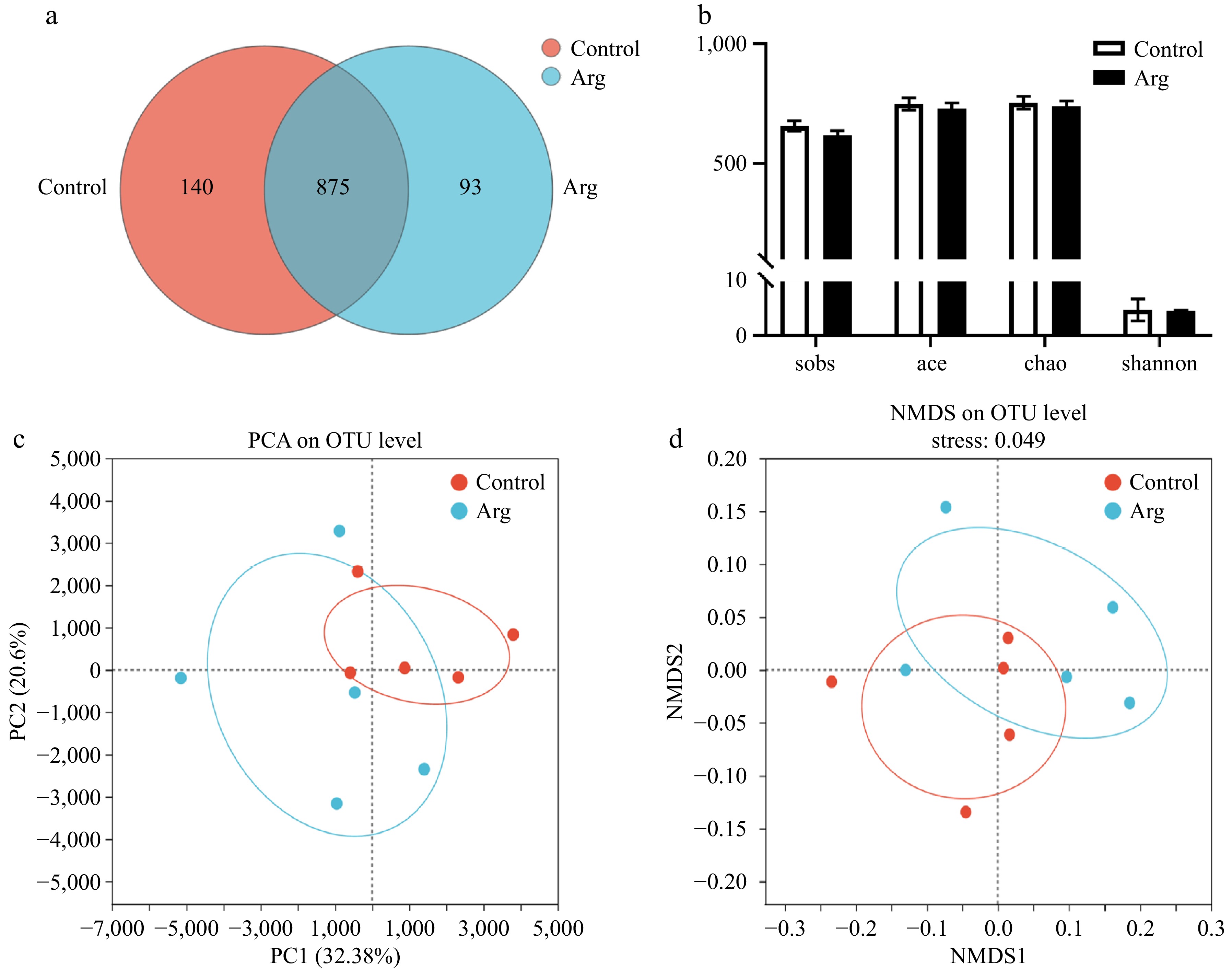

Based on the results of the above semen quality and semen antioxidant indicators, we selected the fecal samples of the control and 1.6% (Arg) groups at week 4 (L-Arg feeding end time) for microbiota analysis. From the species OTU level, the control and Arg groups had 875 identical OTUs. In addition, the control group had 140 unique OTUs, and the Arg group had 93 unique OTUs (Fig. 4a). The results of alpha diversity analysis of fecal microbiota showed that the species richness (Sobs, Ace, and Chao index) and diversity (Shannon index) of the Arg group were not significantly different from those of the control group (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4b). From the Beta diversity analysis, the PCA results showed a specific difference in the fecal microbiota between the two groups. The difference was significant (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4c, d).

Figure 4.

Analysis of Alpha and Beta diversity of fecal microbiota. (a) Species Venn plot analysis. (b) The sobs index represents the actual observed value of species richness, the ace index represents the species richness, the chao index represents the species richness, and the shannon index represents the species diversity. (c) PCA principal component analysis between two groups. (d) NMDS analysis based on weighted-unifrac distance calculation, stress = 0.049. Control: fecal samples at the third week; Arg: fecal samples from the 1.6% group at the third week.

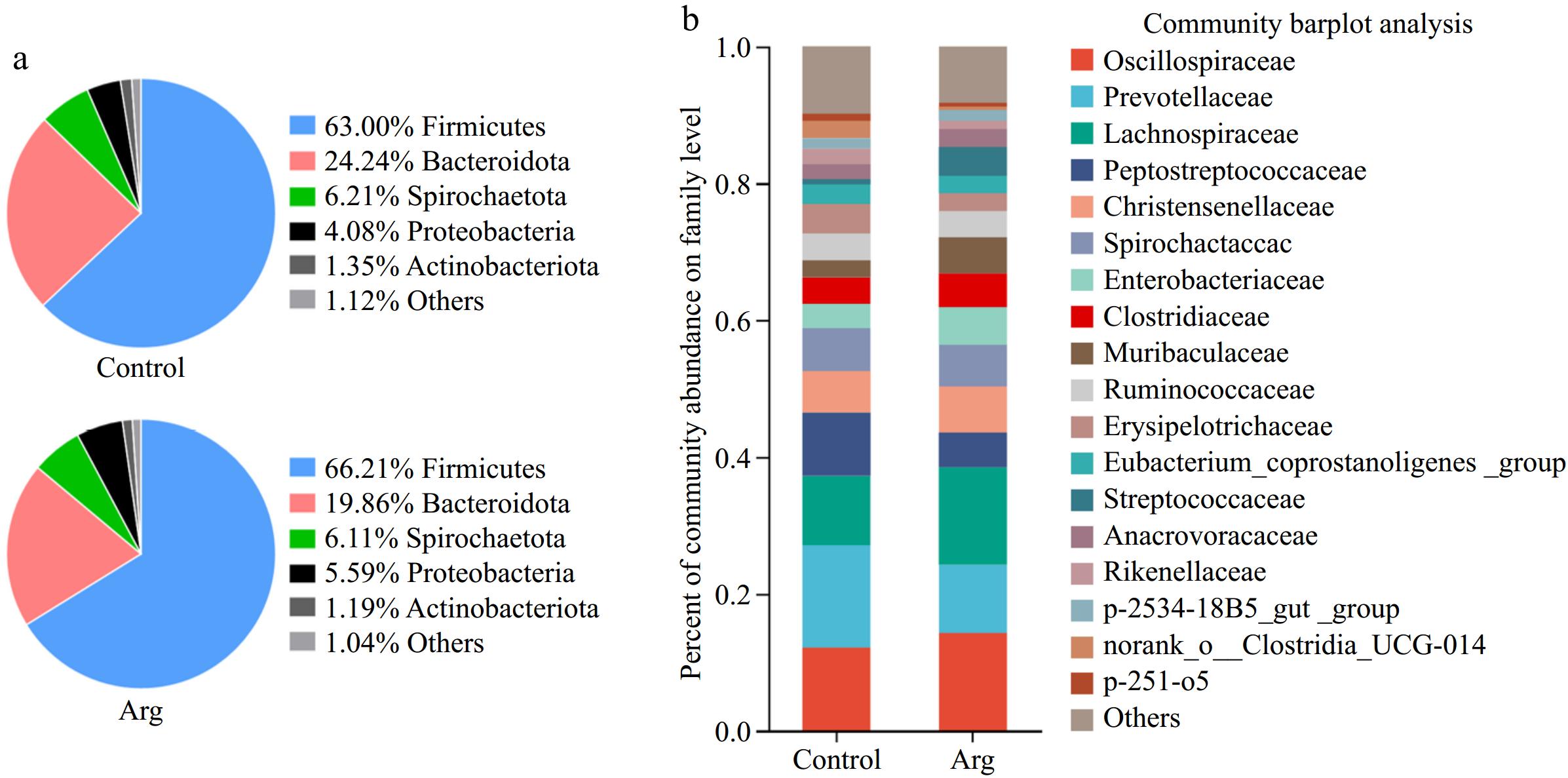

Composition of boar fecal microbiota

-

From the phylum level, the Arg and control groups were dominated by Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Spirochaetota, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria (Fig. 5a). From the family level, taking the content of more than 1% as the standard, the two groups were classified as Oscillospiraceae, Prevotellaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, Christensenellaceae, Spirochaetaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, Clostridiaceae, Muribaculaceae, Ruminococcaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, Eubacterium_coprostanoligenes_group, Streptococcaceae, Anaerovoracaceae, Rikenellaceae, p-2534-18B5_gut_group, norank_o_Clostridia_UCG-014, p-251-o5 are the dominant bacteria. Moreover, the content of Oscillospiraceae in the Arg group (14.23%) was higher than that in the control group (12.10%), the content of Prevotellaceae in the Arg group (9.97%) was lower than that in the control group (14.99%), the content of Lachnospiraceae in the Arg group (14.26%) was higher than that of the control group (10.11%), and the content of Peptostreptococcaceae in the Arg group (5.10%) was lower than that in the control group (9.28%) (Fig. 5b).

Analysis of differential microbiota in feces

-

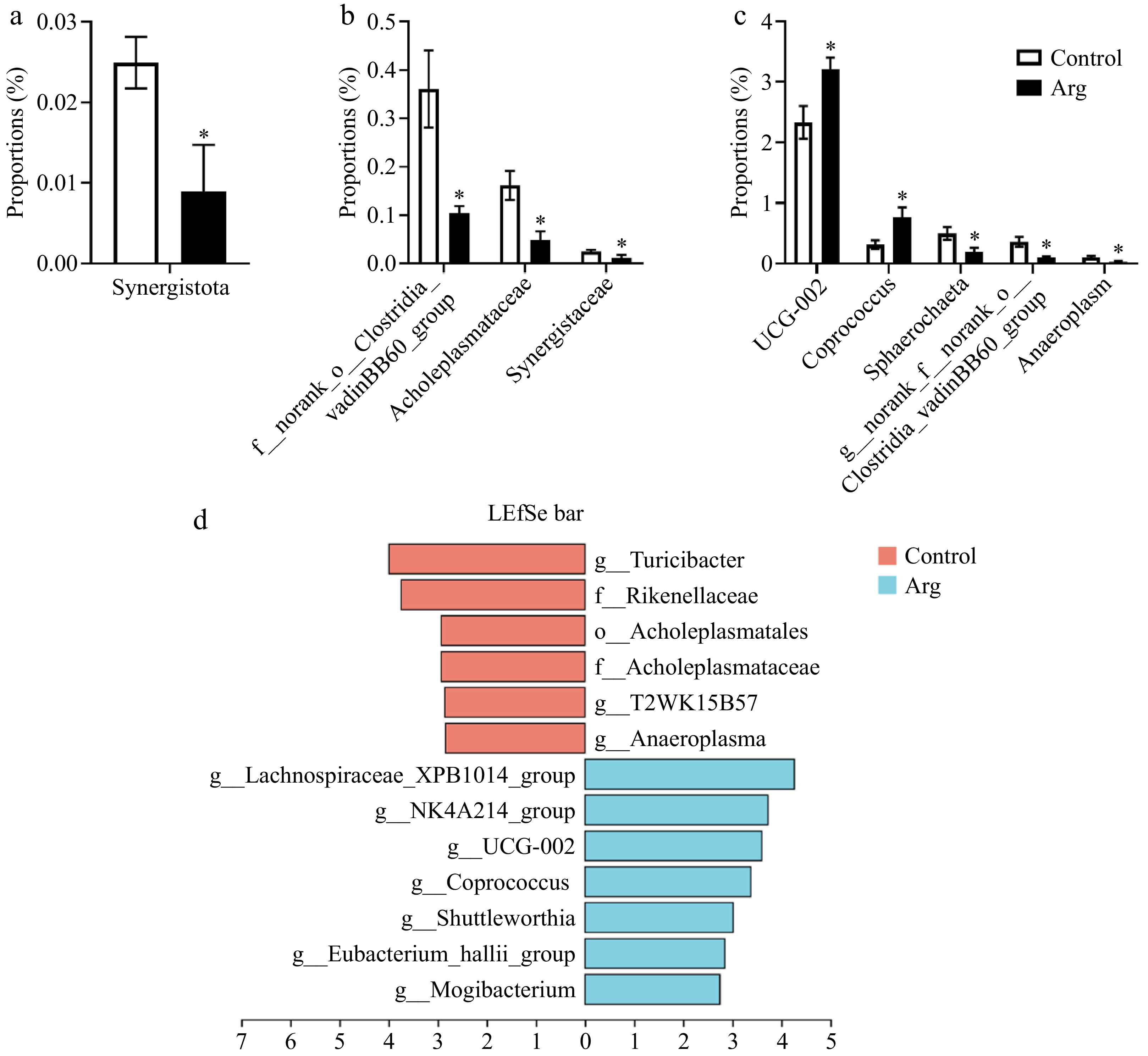

T-test analyzed differential microbiota between the Arg and control groups. From the phylum level analysis, the Synergistota richness in the Arg group was significantly lower than that of the control group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6a). From the family level analysis, the norank_o_Clostridia_vadinBB60_group, Acholeplasmataceae, and Synergistaceae were significantly enriched in the control group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6b). From the genus-level analysis, the UCG-002 (f_Oscillospiraceae) and Coprococcus were significantly enriched in the Arg group (p < 0.05). The Sphaerochaeta, norank_f_norank_o_Clostridia_vadinBB60_group, and Anaeroplasma were significantly enriched in the control group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6c). In addition, the results are similar to those of the T-test. A Lefse multi-level species difference discriminant analysis was performed. The Turicibacter, T2WK15B57, and Anaeroplasma were enriched in the control group (p < 0.05), and Lachnospiraceae_XPB1014_group, UCG-002, and Coprococcus were significantly enriched in the Arg group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6d).

Figure 6.

Analysis of differential microbiota in feces. (a) Species differences at the phylum level. (b) Species differences at the family level. (c) Species differences at the genus level. (d) Lefse multi-level species difference discriminant analysis (LAD > 2, p < 0.05). *, compared with the control group.

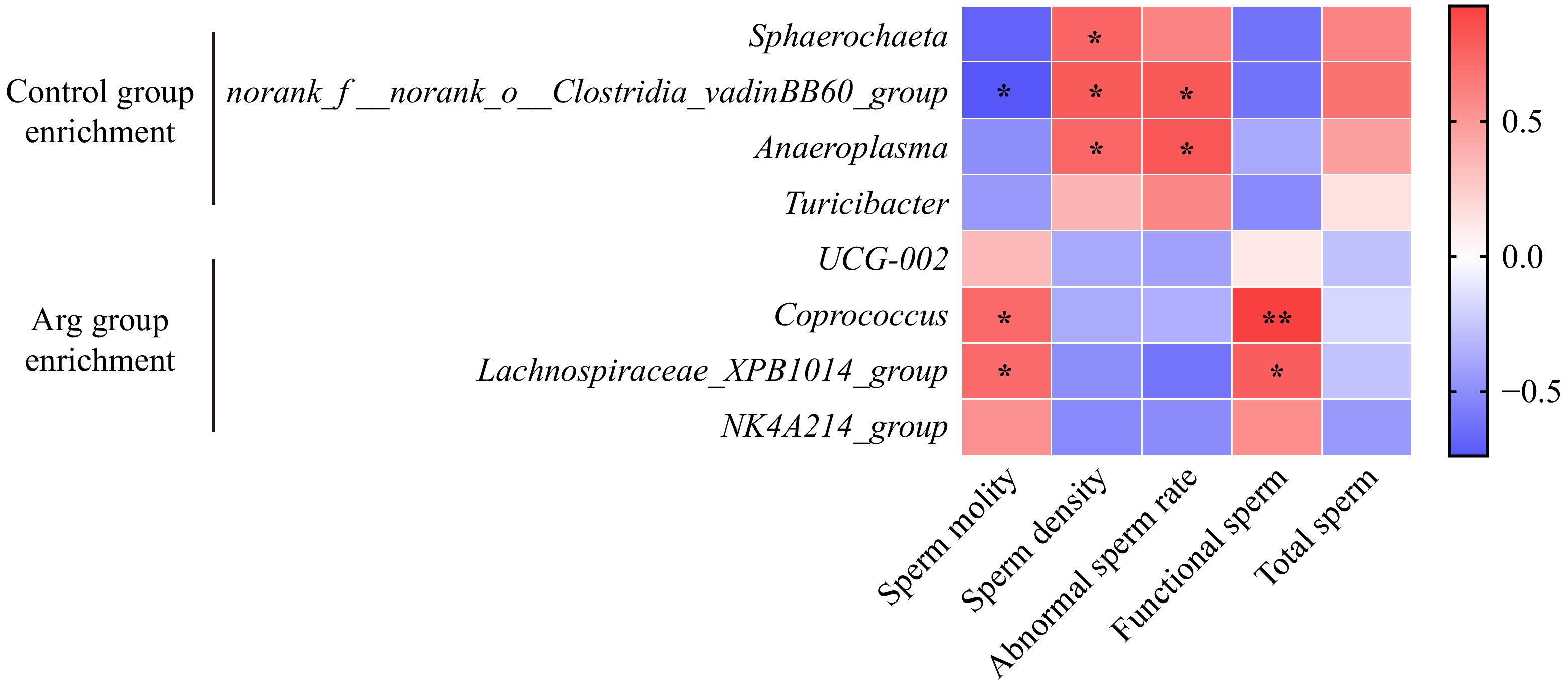

Analysis of the correlation between fecal differential microbiota and semen quality

-

Further, whether there is a correlation between the fecal differential microbiota and semen quality was analyzed. Sphaerochaeta had a significant negative correlation with sperm density (p < 0.05); norank_f_norank_o_Clostridia_vadinBB60_group had a significant negative correlation with sperm motility (p < 0.05) and a significant positive correlation with sperm density (p < 0.05) and abnormal sperm rate (p < 0.05); Anaeroplasma had a significant positive correlation with sperm density (p < 0.05) and abnormal sperm rate (p < 0.05). Coprococcus had significantly positively correlated with sperm motility (p < 0.05) and effective sperm (p < 0.01); Lachnospiraceae_XPB1014_group had significantly positively correlated with sperm motility (p < 0.05) and effective sperm (p < 0.05) (Fig. 7).

-

When exposed for a long time to environmental conditions with the temperature exceeding the upper temperature of the pig's thermoneutral zone (22.7 °C) and the humidity exceeding 86.6%, the semen quality of boars will be affected[24,25]. Sperm damage has been reported to occur at temperatures as low as 22.2 °C, only slightly above the thermoneutral zone of boars (17.7−20 °C)[26]. During this experiment, the indoor temperature was 24.5−31.2 °C, and the relative humidity was 81.0%−95%, which indicated that the boar was in a high-temperature and high-humidity environment. The boar was always under heat stress during the experiment. Scrotal temperature is highly correlated with testicular temperature[27], and the scrotum can regulate temperature by sweating and vasoconstriction[28]. In the case of large white boar, the normal scrotal surface temperature was 30.2 to 33.1 °C[29]. In this experiment, compared with the control group, after adding 0.8% and 1.6% L-Arg to the diet, the scrotal surface temperature of the boars decreased by about 0.3 and 0.6 °C, respectively.

In an in vitro test, where semen was put into L-Arg enriched diluent and then incubated at 39 °C, the results showed that L-Arg had a protective effect on sperm motility at high temperatures[21]. In this experiment, adding 0.8% and 1.6% L-Arg to the boar's diet could effectively alleviate the damage to semen quality by hot summer heat, and sperm motility increased with the increase of L-Arg concentration, which also showed the dependence of boar semen quality on L-Arg dose at high temperatures. However, the lack of significant difference between groups at week 3 may be that the gelatinous substance in the semen of the boars in the 1.6% group was not filtered cleanly, resulting in a bias in semen detection.

Antioxidant substances in seminal plasma can slow down stress damage to sperm. Studies have shown that L-Arg can enhance the antioxidant capacity of rat skeletal muscle, reducing the production of more than oxides[30]. Sperm are susceptible to heat stress, possibly due to the high content of unsaturated fatty acids in the plasma membrane and the low antioxidant capacity of seminal plasma[31]. Treatment of goat sperm with L-Arg reduces the degree of lipid peroxidation in sperm[32]. In this experiment, consistent with the above findings, L-Arg improved the antioxidant capacity of semen (increased levels of T-SOD, CAT, and T-AOC, decreased levels of MDA). As an essential hormone in the male body, testosterone also plays a vital role in sperm production. After supplementation with L-Arg in heat-treated mice, serum testosterone concentrations were restored, and testosterone synthesis-related gene expression was upregulated[22]. In this experiment, the fecal testosterone content was measured at week 4. It was found that the testosterone content in boars' feces increased significantly after adding L-Arg, which indicated that L-Arg could promote testosterone hormone production and have a sustained effect on boars after they stop feeding. Previous studies have noted that gut microbiota, particularly those in the cecum, rely on glucuronidase activity to efficiently deglucuronided testosterone (T) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), producing androgens, for reabsorption in the distal intestine[33,34]. In addition, microbial species such as Clostridium scindens and Ruminococcus gnavus have been found to have the ability to convert glucocorticoids and pregnenolone to androgens, resulting in elevated DHT and T levels in the gut[35]. L-Arg supplementation may alleviate damage to sperm caused by heat stress by increasing the antioxidant capacity of semen and regulating the amount of testosterone.

In previous studies, the broiler diet supplement L-Arg can enhance the gut barrier function and improve the gut microbiota[36]. After L-Arg supplementation in mice, the colonization of beneficial gut microbiota was increased[37]. In this experiment, at the phylum level, both the Arg and control groups were dominated by Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Spirochaetota, and Proteobacteria, consistent with the previous study on the gut microbiota structure of pigs[38]. At the family level, the content of Oscillospiraceae and Lachnospiraceae in the Arg group increased, while Prevotellaceae and Peptostreptococcaceae decreased. Oscillospiraceae were positively associated with acetate and butyrate production in pig colonic microbiome and fermentation product assays[39]. As a probiotic, Lachnospiraceae can ferment to produce short-chain fatty acid salts and has therapeutic effects on diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and fatty liver[40]. Sodium butyrate supplementation in adult roosters improves semen volume and sperm motility by enhancing antioxidant capacity and testosterone hormone secretion[41]. In the mice model of a high-fat diet, the abundance of Prevotellaceae increased significantly. At the same time, sperm motility decreased significantly[11], and Prevotellaceae plays an active role in promoting pulmonary fibrosis[42]. The high density of the Peptostreptococcaceae is found in the intestine of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic radiation proctitis, which indicates a link between the Peptostreptococcaceae and impaired mucosal immunity[43,44]. L-Arg supplementation is beneficial to gut colonization by short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria. Differential microbiota between the two groups, and Synergistota increased in the control group at the phylum level. Synergistota, as a gram-negative bacterium, is found to have increased abundance in the gut microbiota of patients with Ankylosing spondylitis and Alzheimer's disease[45,46]. In diabetic retinopathy, the increase of Synergistota abundance may lead to the disorder of catabolic reaction or the release of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), causing inflammatory damage[47]. In the Arg group, consistent with the above analysis of the composition of the microbiota, the central microbiota of Oscillospiraceae (UCG-002) and Lachnospiraceae (Coprococcus, Lachnospiraceae_XPB1014_group) increased significantly. However, in the control group, the central microbiota of Rikenellaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae (Turicibacter), and Acholeplasmataceae (T2WK15B57, Anaeroplasm) increased significantly. Rikenellaceae typically shows increased abundance in the gut microbiota of mice on a high-fat diet, and a high-fat diet can also negatively affect sperm through the gut microbiota[48]. Many studies have shown that Erysipelotrichaceae is involved in many disease and inflammatory response processes[49,50]. In the present study it was identified that the bacteria Sphaerochaeta, Coprococcus, and Lachnospiraceae are strongly related to sperm quality. There is limited research on Sphaerochaeta directly linking Sphaerochaeta to semen quality. These bacteria are known for their anaerobic and fermentative capabilities. They may influence the microbial environment in the reproductive tract, potentially affecting sperm motility through alterations in the local microbiota and associated metabolic activities. Coprococcus and Lachnospiraceae species are known to be involved in the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), particularly butyrate, which has anti-inflammatory properties. SCFAs can influence overall health, including reproductive health, by modulating systemic inflammation and metabolism. In the context of semen, Coprococcus and Lachnospiraceae may indirectly influence sperm motility through their effects on systemic health and possibly through direct interactions within the reproductive tract.

In summary, the above microbiota are related to gut immunity. Immune system activation caused by gut microbiome translocation not only leads to inflammation of the testes and epididymis but also affects the secretion of various sex hormones such as LH, FSH, and testosterone to affect spermatogenesis[51]. Therefore, supplementation with L-Arg can improve the gut microbiota to protect the gut barrier function better and reduce inflammation.

In the following correlation analysis, a significant correlation was found between microbiota and semen quality. In the analysis of the gut microbiota of Duroc boars with different semen utilization, it was found that there was a strong correlation between the gut microbiota and semen quality[52]. Studies have shown that chestnut polysaccharides can improve the damage caused by busulfan to sperm by regulating the gut microbiota[53]. Supplementation with the probiotic strains Lactobacillus fermentum NCDC 400 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus NCDC 610 increased the expression of genes associated with testosterone production. It maintained testicular tissue morphology[54]. The above findings illustrate a strong correlation between gut microbiota and spermatogenesis.

-

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that heat stress adversely affects the reproductive performance of boars. Supplementing their diet with L-Arg appears to mitigate these effects by enhancing semen quality and gut microbiota health during summer heat stress. The addition of 1.6% L-Arg to the diet led to significant improvements in semen quality and antioxidant capacity in boars. Microbiota analysis revealed that L-Arg supplementation resulted in beneficial changes at various taxonomic levels, including a reduction in Synergistota and an enrichment of specific beneficial bacterial groups. These findings suggest that L-Arg could be a valuable dietary supplement to improve reproductive health in boars under heat stress conditions, with potential mechanisms involving modulation of the gut microbiota.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32372935), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2020M681648) and the Jiangsu Postdoctoral Research Funding Program (2021K435C).

-

All procedures were reviewed and preapproved by the Nanjing Agricultural University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, identification number: NJAULLSC2021062, approval date: 2021/6/1. The research followed the 'Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement' principles to minimize harm to animals. This article provides details on the housing conditions, care, and pain management for the animals, ensuring that the impact on the animals is minimized during the experiment.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Li C; experimental protocol optimization, database design, data analysis & interpretation; Suo Y, Li X, Nagaoka K; data visualization: Li Y; draft manuscript preparation & revision: Wang K. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The 16S rRNA sequencing data can be obtained by logging onto the NCBI database (PRJNA937596).

-

All authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. Chunmei Li is the Editorial Board member of Animal Advances who was blinded from reviewing or making decisions on the manuscript. The article was subject to the journal's standard procedures, with peer-review handled independently of this Editorial Board member and the research groups.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang K, Suo Y, Li X, Nagaoka K, Li Y, et al. 2024. Improvement of seminal quality and microbiota diversity in heat-stressed boars through dietary L-arginine supplementation. Animal Advances 1: e006 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0024-0006

Improvement of seminal quality and microbiota diversity in heat-stressed boars through dietary L-arginine supplementation

- Received: 05 September 2024

- Revised: 22 October 2024

- Accepted: 31 October 2024

- Published online: 28 November 2024

Abstract: Heat stress negatively impacts boar reproductive performance. L-arginine (L-Arg) supplementation may help improve semen quality and gut microbiota during summer conditions. This study aimed to investigate the effect of dietary L-arginine supplementation on scrotal surface temperature, semen quality, semen antioxidant status, fecal testosterone content, and fecal microbiota in heat-stress boars during hot summer months. In the experiment, 15 boars of similar age (large white, about 480 d of age), body condition, and semen quality were selected and divided into three groups equally. The results showed that adding 1.6% L-Arg to the diet significantly improved the semen quality parameters of summer boars (p < 0.05). After adding 0.8% and 1.6% L-Arg to the diet, the antioxidant capacity of boar semen was significantly improved (p < 0.05). By analyzing the differential microbiota, at the phylum level, the Arg group had significantly reduced Synergistota abundance (p < 0.05); at the family level, the abundance of Acholeplasmataceae and Synergistaceae decreased significantly in the Arg group (p < 0.05); at the genus level, the UCG-002, Lachnospiraceae_XPB1014_group and Coprococcus were significantly enriched in the Arg group (p < 0.05). In the correlation analysis, there were different degrees of correlation between differential microbiota and semen quality indicators. The results provide a theoretical basis for L-Arg to improve semen quality in summer boars based on gut microbiota.

-

Key words:

- L-Arg /

- Summer boars /

- Semen quality /

- Antioxidant capacity /

- Fecal microbiota