-

Grasslands constitute one of the most extensive ecosystems globally, encompassing over 40% of total land area. These ecosystems provide essential resources such as fodder, food, energy, and medicinal products for human consumption while simultaneously offering critical ecological functions, including climate regulation, soil conservation, biodiversity maintenance, and aesthetic enhancement[1]. However, anthropogenic activities have led to a significant decline in both the quantity and quality of grasslands, exacerbating the imbalance between supply and demand for grassland resources[2]. Consequently, the development and utilization of grassland resources to enhance productivity and ecological benefits are crucial pathways for addressing human food security and sustainable development[3]. Forage grasses, a major component of grasslands, serve as food sources for numerous livestock species and contribute to increased carbon accumulation in soils[4]. These grasses are generally classified as warm- or cool-season, referred to as C4 and C3 forage grasses, respectively. Both types exhibit diverse morphological, physiological, and genetic characteristics, enabling their adaptation to various habitats and management conditions, thereby offering substantial utilitarian value to humanity[5]. However, grasslands have been suffering from ongoing degradation in recent years, which severely impairs the biomass yield and fodder quality of forage grasses. Therefore, it is urgent to further improve the environmental adaption and grassland productivity of this versatile resource for human benefit.

Transgenics represents an advanced technology utilized since 1996 to produce commercial grain and oil crops with desired traits[6]. This approach typically involves the transfer of one or several specific foreign target genes into the genome of the target organism using current genetic engineering techniques. This process enables predictable and directional genetic modifications, resulting in transgenic biological lines. Furthermore, breeders can swiftly eliminate undesired traits by interfering with or inhibiting the expression of existing genes in the genome. This technology offers high conversion efficiency, relatively short timeframes, and strong predictability, marking a significant advancement in modern biotechnology. Presently, transgenic technology in plant variety improvement primarily addresses herbicide resistance, insect resistance, disease resistance, abiotic stress resistance, yield enhancement, and nutritional quality improvement[6].

The development of novel forage grass cultivars with high biomass yield, improved forage quality, and enhanced stress resistance is crucial to meet diverse societal demands. Over the past decade, various innovative transgenic approaches have been established and developed for forage grasses[7−9]. However, the molecular breeding of forage grasses still faces numerous challenges, mainly due to polyploidy complexity, large genomes, self-incompatibility, and extremely low transformation efficiencies[10]. These obstacles also hinder the exploration and utilization of valuable functional gene resources, consequently limiting the widespread application of advanced biotechnologies such as genome editing and gene stacking in the genetic improvement of forage grasses[11].

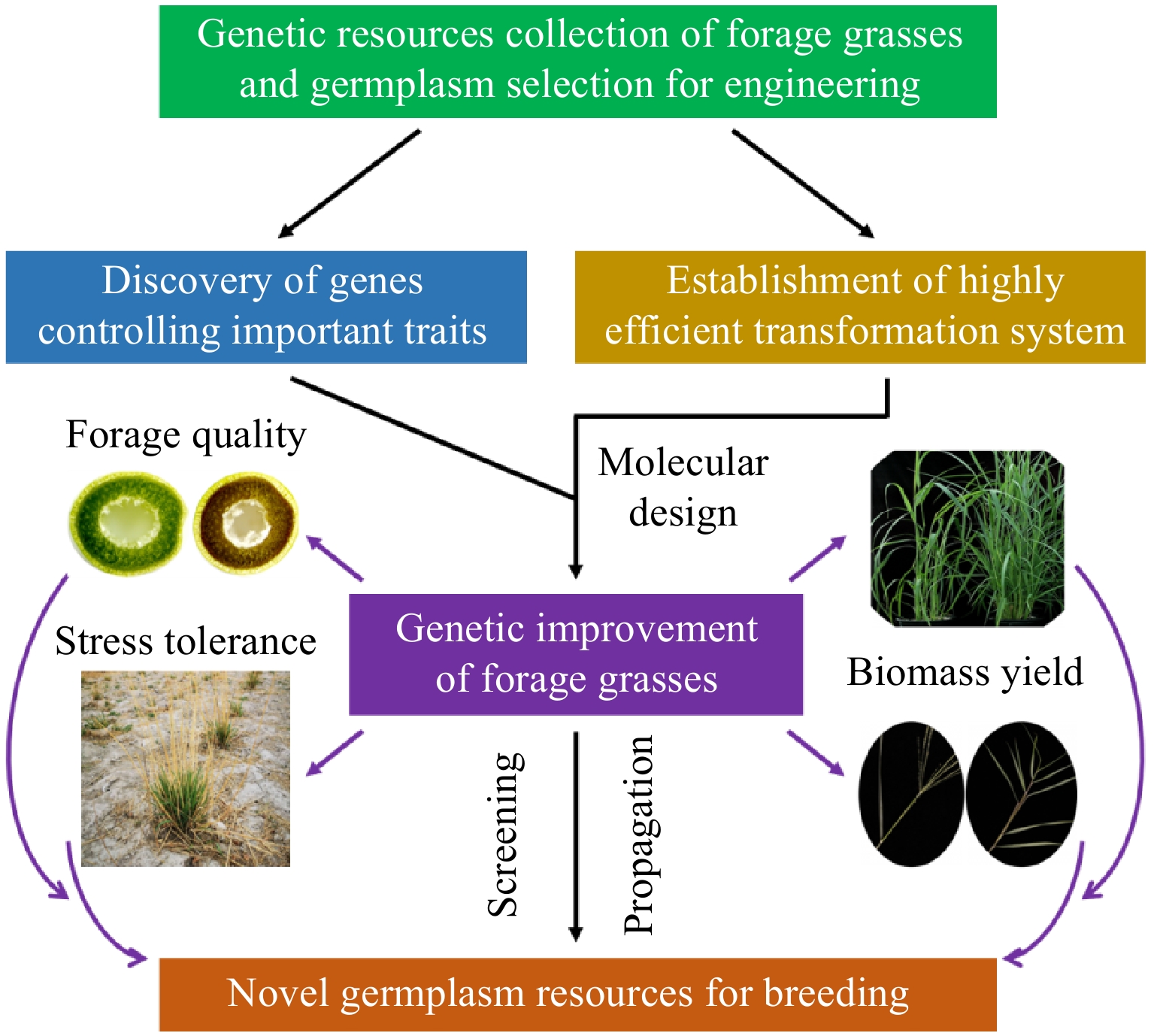

The current genetic improvement of forage grasses primarily focuses on three key objectives: biomass yield, forage quality, and stress resistance. The identification and manipulation of agronomically important genes represent two crucial steps in developing novel forage grass germplasm or cultivars that exhibit high biomass yield, superior forage quality, and enhanced stress resistance. Several important forage grasses, including oat (annual C3 grass), ryegrass (perennial C3 grass), sheepgrass (perennial C3 grass), and switchgrass (perennial C4 grass), have garnered increased attention in recent years due to their crucial roles in food, feed, or fuel production and environmental protection[12−15]. Thus, this review primarily examines the advancements in gene identification and manipulation technologies employed in the genetic improvement of these forage grasses over the past decade. Additionally, it discusses the potential applications of transgenic approaches in the breeding and cultivar development of forage grasses.

-

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) refers to the sequencing of an individual or population's genome utilizing advanced high-throughput sequencing technologies, followed by comprehensive bioinformatic analysis of sequence features to identify functional genes at the genome-wide level. Over the past decade, genome sequences of several forage grass species including oat, perennial ryegrass, sheepgrass, and switchgrass, as summarized in Table 1, have been successfully assembled. WGS has found widespread application in the identification and isolation of functional genes aimed at enhancing biomass yield, fodder quality, and stress resistance in forage grasses.

Table 1. Genome information of oat, ryegrass, switchgrass, and sheepgrass.

Species Assembly size (Gb) Contig N50 (kb) Genome coverage* Sequencing method Ref. Oat (A. atlantica Cc 7277) 3.69 513,200 84x PacBio and Illumina [16] Oat (A. eriantha CN 19328) 3.78 534,800 71x PacBio and Illumina [16] Hexaploid oat (Sanfensan) 10.76 75,273 100x Oxford Nanopore, Hi-C and Illumina [17] Diploid oat (A. longiglumis, CN 58139) 3.74 7,298 60x Oxford Nanoporeand Illumina [17] Tetraploid oat (A. insularis, CN 108634) 7.52 5,637 60x Oxford Nanopore, Hi-C and Illumina [17] Perennial ryegrass(P226/135/16) 1.13 70 9x PacBio and Illumina [18] Heterozygous Italian ryegrass (M2289) 0.586 5 28x Illumina [19] Perennial ryegrass (Kyuss) 2.28 11,740 70x Oxford Nanoporeand Illumina [20] Heterozygous Italian ryegrass (Rabiosa) 4.53 3,050 500x NRGene and Illumina [21] Perennial ryegrass (P226/135/16) 2.55 1074 81x PacBio, Illumina,BioNano and Hi-C [22] Sheepgrass (Lc6-5) 7.85 318,490 115x PacBio, Hi-Cand Illumina [23] Switchgrass (Alamo, tetraploid) 1.13 5,461 121x PacBioand Illumina [26] * Represents the highest genome coverage of all the sequencing methods. Oat (Avena sativa L.) is a high-quality annual cool-season C3 grass, utilized as both a food and feed crop. The large and complex genome of oats has resulted in delayed genome sequencing compared to other significant grain crops such as rice, maize, and soybean[13]. Consequently, researchers from multiple countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada, collaboratively initiated the 'Oat Genome Project' in 2010. They have subsequently completed the entire genome sequencing and chromosome-level assembly of diploid oats, as well as the sequencing of hexaploid common oats[16]. The genome of hexaploid oats was announced on June 23, 2020. Furthermore, Chinese scientists published a high-quality reference genome sequence of cultivated naked oats (Avenasativa var. nuda) in July 2022[17]. These advancements have established a foundation for basic biological research, functional genomics research, and molecular breeding of oats.

Perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) is a significant perennial cool-season C3 forage and turf grass with considerable economic and ecological importance[14]. Owing to its outcrossing nature, constructing a robust reference genome for ryegrass has been challenging using second-generation sequencing technology[18,19]. Consequently, gene identification in perennial ryegrass has primarily relied on transcriptomic data or PCR cloning based on homologous sequences. In 2021, Frei et al. assembled the perennial ryegrass Kyuss genome to 2.28 Gb with a Contig N50 of about 11.7 Mb[20]. In the same year, Copetti et al. developed a genome map for the Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) cultivar Rabiosa[21]. In 2022, Nagy et al. reassembled the perennial ryegrass P226/135/16 genome to 2.55 Gb with a Contig N50 of about 10.7 Mb[22]. Therefore, recent years have witnessed substantial advancements in perennial ryegrass genome sequencing and analysis, facilitated by third-generation sequencing technology.

Sheepgrass (Leymus chinensis (Trin.) Tzvel) is a high-quality perennial C3 forage grass that dominates extensive dry grassland communities and saline meadows[14]. The large and highly heterozygous genome of sheepgrass has historically presented significant challenges for functional genomics research. However, recent advancements in sequencing technologies and assembly methods have facilitated the publication of a high-quality chromosome-scale genome sequence for sheepgrass. This groundbreaking work reveals a sheepgrass genome approximately 8 Gb in size, with a contig N50 exceeding 300 Mb[23]. Based on WGS results, the researchers will deepen the understanding of polyploidy's impact on complex genetic traits of sheepgrass and identify more crucial genes associated with biomass yield, forage quality, and stress from this precious species[24].

Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) is a perennial warm-season C4 tall grass native to North America. Its high biomass yield, broad geographic adaptability, robust stress tolerance, and extensive root system make it valuable for feed, fuel, soil conservation, and phytoremediation[12]. Advancements in high-throughput sequencing technologies and sustained global research efforts have yielded substantial data and expertise in switchgrass WGS and genetic enhancement[25,26]. In 2021, Lovell et al. reassembled the switchgrass Alamo genome to 1.1 Gb with a Contig N50 of about 5.5 Mb[26]. The completion of switchgrass WGS has established a foundation for mining significant functional genes of interest[27−31].

A precise WGS not only makes transgenes' cloning easier, but also facilitates characterizing the locations of randomly integrated transgenes in the forage grass genome. As the evolution of high-throughput sequencing technologies and bioinformatics has led to a gradual reduction in WGS costs[32], more WGS of forage grasses will be assembled in the future. It is beneficial for precise and predictable gene manipulation in forage grasses to obtain desired traits through transgenic approaches.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS)

-

WGS provides comprehensive, precise, and efficient information for identifying forage grass genes at the genomic level. However, the identification of novel functional genes still requires combining other gene mining technologies. GWAS, based on linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis, has emerged as a powerful tool for dissecting complex agronomic traits and identifying superior alleles that enhance target traits. With the advancement of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, GWAS has been widely employed for rapid mining and identification of crucial genes for yield, quality, and stress resistance traits in forage grasses. As global warming makes severe droughts become more frequent in grasslands, breeding cultivars of forage grasses with high drought tolerance are urgently needed to ensure a sustainable fodder-supplying system. In perennial ryegrass, three significant SNPs were identified associated with biomass formation under drought stress[33]. Researchers also identified the primary locus controlling drought stress traits by combining GWAS and quantitative trait loci (QTL) analyses[34]. Heading date can affect flowering, yield stability, and adaptability of forage grasses, which is one of the most important traits for genetic modification. In oat, three loci associated with heading date have been identified through GWAS[35]. Among them, Vernalization 3 (Vrn3) and Vernalization 1 (Vrn1) have been identified in Mrg02, Mrg12, and Mrg21, respectively. These genomic regions contribute significantly to providing marker-assisted selection markers for breeding oat varieties with different heading dates. In switchgrass, GWAS analysis reveals five significant SNPs controlling heading date and anthesis traits to increase biomass by delaying the flowering of switchgrass[36]. Furthermore, independent research reported by Niu et al. deciphers the functions of FT in switchgrass flowering regulation, confirming the reliability of GWAS results[37]. The joint and sustained efforts of researchers will enhance our understanding of quantitative traits of forage grasses and facilitate their molecular design breeding.

Comparative transcriptomics analysis

-

Transcriptomics, a crucial component of functional genomics, enables researchers to conduct comprehensive analyses of transcription and gene expression patterns. Comparative transcriptomics analysis identifies new genes associated with target traits by examining variations in transcriptional levels under different conditions. In oat, the researchers utilized RNA-seq mediated transcriptome analysis to identify numerous salt tolerance genes including the transcription factors from MYB, bHLH, WRKY, and NAC families[38]. In perennial ryegrass, the researchers identified 36,497 up-regulated and 18,218 down-regulated genes following salt-alkali stress treatment through comparative transcriptomics analysis. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis and gene annotation suggest that these differentially expressed genes were primarily associated with stress response, signal transduction, energy production and conversion, and inorganic ion transport in perennial ryegrass[39]. Additionally, comparative transcriptomics analysis has been employed to investigate the response of transcription factor families in perennial ryegrass under salt stress, identifying WRKY, C3HL, NAC, and other transcription factors responsible for salt tolerance. In switchgrass, researchers identified PvUGT89A, a novel gene that metabolizes DNTS, through metabolite identification, transcriptome data mining, and in vitro recombinant protein expression and enzyme activity analysis[40]. Furthermore, overexpression of PvUGT89A significantly enhanced the DNTS clearance ability of switchgrass. This technology is now widely utilized in the exploration of superior genes in forage grasses, contributing significantly to their molecular breeding and genetic enhancement efforts.

-

Plant genetic transformation involves the introduction of exogenous target genes into experimental plants through artificial biotechnological methods. Utilizing recombinant DNA principles, target genes are integrated into the plant genome, ensuring stable inheritance and acquisition of desired traits such as stress resistance, high yield, and quality[6]. This technology enables the genetic recombination of biological traits among different plants at the gene level to achieve specific objectives. It transcends natural biological constraints among species, offering possibilities for enhancing plant breeding efficiency. Currently, target gene introduction techniques in forage grasses primarily fall into two categories. The predominant approach is Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, which is widely used due to its clear mechanism, mature technology, and numerous successful applications[9,41−47]. However, this method is constrained by species genotype and explant types (Table 2). The second approach is particle bombardment, which is independent of genotype and explant types. Nevertheless, this method has several limitations in plant genetic transformation, including high cost, frequent insertion of multicopy genes, low transformation efficiency, and high gene silencing rates[48]. Recently, researchers have shown increasing interest in certain nanomaterials, such as silica, metals, polymers, magnetic nanoparticles, and carbon nanotubes. These nanomaterials can autonomously enter plant tissue cells, with both dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous plants exhibiting varying degrees of direct absorption of various nanoparticle types. This method has been successfully applied to several model crops, including wheat, corn, and rice[49−51]. However, nanoparticle-mediated transformation has yet to be utilized in any forage grasses to date.

Table 2. Transformation systems of oat, perennial ryegrass, sheepgrass, and switchgrass.

Species* Type of donors Gene transfer method Methodologies for improving transformation efficiency Oat[41] Seed induced embryogenic calli Agrobacterium mediated High quality embryogenic calli induction, vacuum, and sonication Oat[41] Leaf base induced embryogenic calli Agrobacterium mediated High quality embryogenic calli induction, vacuum, and sonication Perennial ryegrass[52] Seed induced embryogenic calli Agrobacterium mediated High quality embryogenic calli induction, cold shock,

L-Gln, addition, and myo-inositol removalPerennial ryegrass[42] Seed induced embryogenic calli Agrobacterium mediated High quality embryogenic calli induction and heat shock Perennial ryegrass[42] Shoot meristem tips Agrobacterium mediated Sonication Perennial ryegrass[53] Seeds induced embryogenic calli Particle bombardment High quality embryogenic calli induction Perennial ryegrass[54] Calli induced from shoot tips, seeds, and anthers Agrobacterium mediated High quality embryogenic calli induction Sheepgrass[43,45] Seed/inflorescence induced embryogenic calli Agrobacterium mediated High quality embryogenic calli induction and co-expressing wheat TaWOX5 Switchgrass[37,44,46] Seed/inflorescence induced embryogenic calli Agrobacterium mediated High quality embryogenic calli induction, vacuum, and

co-expressing maize ZmBbm and ZmWus2Switchgrass[55] Embryogenic cell suspension cultures Agrobacterium mediated Establishment of regenerable embryogenic cell suspension cultures Switchgrass[56] Inflorescence induced embryogenic calli Agrobacterium mediated Engineering A. tumefaciens to express a T3SS * Refers to all cited representive references from the last ten years. As the basis of transgenic breeding and plant genome editing, Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation technology has been thoroughly studied in forage grasses. To date, many efficient methods to deal with the induction and regeneration of embryogenic calli have been established in forage grasses. The methodologies employed for improving transformation efficiency of oat, perennial ryegrass, sheepgrass, and switchgrass are summarized in Table 2. Among them, the induction and selection of high-quality embryogenic calli are usually used for increasing the transformation efficiencies of oat, perennial ryegrass, sheepgrass, and switchgrass (Table 2). Recent studies also suggest that co-expression of morphogenic factors Triticum aestivum WOX5 (TaWOX5) and Zea mays Wuschel2 (ZmWus2)/Baby Boom (ZmBbm), respectively, can significantly increase transformation efficiencies of sheepgrass and switchgrass (Table 2). Another strategy to improve transformation efficiency of forage grass is based on engineering A. tumefaciens. For example, a 400% increase in transformation efficiency has been achieved in switchgrass by using engineered A. tumefaciens expressing a type III secretion system (T3SS) from Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae 61 (Table 2). Additionally, some physical stimulations including treatments with vacuum, sonication, heat/cold shock, and organic compounds such as glutamine (L-Gln) and myo-inositol have effects on the infection capacity of A. tumefaciens. These factors can be utilized to increase the transformation efficiency of forage grasses as well (Table 2).

Gene overexpression technology

-

Researchers typically investigate gene function by modifying its expression through transgenic approaches, aiming to elevate target gene expression levels. This manipulation enables direct observation of phenotypic changes to obtain functional information or indirect analysis of functional characteristics by altering the coding sequence. Gene expression depends on cis-acting elements, such as transcription factors. The promoter sequence acts as a regulatory mechanism controlling the initiation of gene transcription, necessitating the analysis of spatiotemporal specificity of promoter function through transgenic strategies. Specifically, incorporating a strong promoter upstream of the target gene can lead to its overexpression under the influence of this promoter. Numerous plant-suitable promoters have been isolated from plants, viruses, and microorganisms. These promoters can be categorized into three groups based on their mode of action and function: (1) constitutive promoters, which regulate gene expression to maintain relatively constant levels across different parts or tissues; (2) tissue-specific promoters, whose regulatory effects confine gene expression to specific organs or tissues, exhibiting developmental regulation characteristics; (3) inducible promoters, where gene transcription levels significantly increase under specific physical or chemical signal stimulation. While this classification generally reflects their respective characteristics, in some instances, a single promoter type may exhibit features of other promoter types.

Constitutive promoters belong to the first category, characterized by their ability to initiate gene expression in all tissues and developmental stages. This continuous, non-specific activity maintains stable RNA and protein levels but lacks spatial and temporal regulation. In plant overexpression systems, the CaMV35S promoter from the cauliflower mosaic virus and plant-derived Ubiquitin promoters are widely used for their ability to drive strong, constitutive expression of transgenes across diverse plant tissues. However, their non-specific, ubiquitous expression can pose limitations, potentially leading to unintended phenotypic consequences or off-target effects in non-target tissues and developmental stages. For example, the degree of morphological alterations of the miR156 overexpressing transgenic switchgrass is highly correlated with miR156 level[57]. Relatively low levels of miR156 overexpression can increase biomass yield while producing plants with normal flowering time. Moderate levels of miR156 result in improved biomass but the plants are nonflowering. However, high miR156 levels always result in severely stunted growth, low biomass yield, and nonflowering. The second category is tissue-specific promoters, which initiate the expression of exogenous genes in targeted locations within the plant, addressing the nonspecific, sustained, and efficient expression associated with constitutive promoters. However, limitations exist, particularly regarding the need for high levels of expression in specific target tissues, which may not always be attainable, thus restricting the effectiveness of this class of promoters. Consequently, tissue-specific promoters have become a focal point in the development of plant overexpression technology. The third category comprises inducible promoters, which, depending on the growth environment can induce or inhibit the expression of target genes in response to specific physical or chemical signals. These promoters can rapidly trigger gene transcription 'on' or 'off' in response to stress, enabling precise control over gene expression.

Gene silencing technology

-

RNA interference (RNAi) is an effective and specific gene silencing technology, serving as a valuable tool for investigating gene function. RNAi technology has been employed to enhance antiviral properties and forage quality in ryegrass. For example, ryegrass mosaic virus (RgMV) significantly impacts the growth and yield of ryegrass, leading to dry matter losses ranging from 5% to 50%. Targeting viral genes, such as those encoding the capsid protein can be achieved by constructing vectors capable of expressing hairpin RNA (hpRNA). These RNAi vectors are introduced into ryegrass via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or particle bombardment, thereby interfering with viral expression and ultimately producing novel ryegrass germplasm highly resistant to RgMV[58]. Furthermore, RNAi technology has been utilized to silence the expression of major allergenic protein-encoding genes, such as Lol p5, thus generating non-allergenic or low-allergenic ryegrass materials[59]. Additionally, in switchgrass, downregulating the expression of caffeic acid O-methyltransferase gene (PvCOMT) through RNAi technology increased ethanol production by up to 38% compared with non-transgenic controls, enhancing the potential for lignocellulosic biocombustion without growth loss or increased sensitivity of the feedstock to rust[60,61].

Recently, the fusion of the SUPERMAN repressor domain X (SRDX) repressor domain to transcription factors has been employed to effectively suppress the expression of downstream target genes. Cen et al. utilized Chimeric Repressor Silencing Technology (CRES-T) to silence the DST gene in rice by attaching it to the SRDX domain. Building on this approach, they further introduced the OsDST-SRDX construct into perennial ryegrass to explore its functional applicability across different plant species. Transgenic lines expressing the OsDST-SRDX fusion gene exhibited distinct phenotypic differences compared to non-transgenic plants and demonstrated significant resistance to both salt shock and sustained salt stress. Physiological analyses revealed that the OsDST-SRDX fusion gene enhanced salt tolerance in transgenic perennial ryegrass by modifying various physiological responses[62]. Similarly, improvements in biomass yield have been achieved in switchgrass through CRES-T technology[63].

Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) is a valuable tool in plant molecular biology for transient gene silencing, commonly used to study gene function in species where stable genetic transformation is difficult to achieve. This technique exploits the plant's intrinsic RNA-mediated antiviral defense pathway to suppress target gene expression temporarily[64]. In the past decade, this methodology has been effectively utilized to identify and characterize functional genes in various forage grasses. Researchers implemented FoMV vectors and leaf friction inoculation methods, previously established in corn, sorghum, and wheat, to achieve VIGS in switchgrass, thus offering new approaches for investigating gene function and physiological traits in this significant bioenergy crop[65].

Gene editing technology

-

The predominant genome editing systems currently include zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) technologies. Among these, CRISPR/Cas9 emerges as a robust and optimal gene editing approach for functional analysis and genetic enhancement in forage grasses. This method employs site-specific nucleases or nucleotide-guided nucleases to precisely cleave or modify target gene sequences, thereby altering their function and effects. Over the past decade, CRISPR/Cas9 editing technology has been extensively applied in numerous forage crops, including cereals, trees, and vegetables, enhancing their biomass or grain yield, quality, and stress resistance[66−68]. Despite its potency, this tool has not been widely implemented in forage grasses due to its large, complex genomes and low transformation efficiencies. Recently, however, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing systems have been successfully established in several key forage grasses, including oat, ryegrass (Lolium spp.), sheepgrass, switchgrass, barley (Hordeum vulgare), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), and foxtail millet (Setaria italica)[7,8,23].

In oat, converting isoleucine to leucine at critical sites of the target protein for the herbicide 'halosulfuron-methyl' generates herbicide-resistant edited plants[69]. In ryegrass (Lolium spp.), eight T0 LpDMC1 knockout mutations were produced through CRISPR/Cas9 technology[53]. In sheepgrass, the effective Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing systems have been successfully established in Xiaofeng Cao's Lab[43]. Using this platform, they successfully knocked out LcTB1 with 11% transformation and 5.83% editing efficiency[43]. In switchgrass, Park et al. edited the 4-coumarate: CoA ligase 1 (Pv4CL1) gene, a key enzyme in lignin biosynthesis, using CRISPR/Cas9 technology with approximately 10% efficiency. Notably, they produced lines with homozygous mutations in four Pv4CL1 alleles, exhibiting lower lignin and higher sugar release[70]. Although CRISPR/Cas9 technology presents a powerful tool for gene functional analysis and genetic improvement of forage grasses, it still faces challenges in precise prediction and design of sgRNAs, particularly for homozygous editing of allopolyploid genomes (e.g., switchgrass and sheepgrass) compared to diploid ones (e.g., rice and maize). In contrast, RNAi technology typically utilizes 200−600 bp relatively conserved sequences, sufficient for gene silencing. Thus, RNAi technology remains competitive in gene functional analysis and genetic improvement of forage grasses.

-

Forage grasses play a crucial role in global agriculture as primary sources of livestock feed. However, climate change, land degradation, and increasing demand for high-yield, high-quality fodder necessitate comprehensive exploration of functional genes in forage grasses to enhance their traits, resilience, nutritional value, and production efficiency[71]. The utilization of gene discovery, genetic transformation technologies, exploration and utilization of genetic resources, application of combination breeding and molecular design technologies, and multi-level, multi-factor evaluation and screening methods will contribute to the development of new forage grass varieties with enhanced adaptability and stress resistance, thereby promoting the sustainable growth of the forage industry (Fig. 1).

The rapid advancement of high-throughput sequencing technologies provide robust tools for this exploration. WGS (Trait-to-Trait, T-to-T) and pan-genome sequencing of forage grasses yield comprehensive, high-quality genomic sequences and diversity information, facilitating the identification of key genes associated with grass growth, development, disease resistance, and nutritional quality[10,72]. This lays the foundation for subsequent functional studies. Additionally, transgenics will remain the preferred approach for the genetic improvement of forage grasses in the future, particularly for introducing novel traits and modifying existing ones[73]. The rapid increase in plant genome sequencing and functional genomics data, coupled with new gene cloning and tissue culture methods, has accelerated improvement and trait development of forage grasses. These advancements are necessary to enhance forage grasses adaptability to climate change and ensure yields to feed the growing population.

Despite successes, the transformation of forage grasses remains challenging as many plant species and genotypes struggle to adapt to established tissue culture and regeneration conditions or exhibit poor transformation efficiency. The use of transcription factors promoting the formation and regeneration of embryogenic calli may offer improvement, but their broader applicability requires further testing. Additionally, complex traits are often controlled by multiple genes acting synergistically, necessitating more sophisticated gene manipulation techniques. The emergence of large fragment transformation and deletion technologies will facilitate improvements in complex traits. By introducing or deleting large genome segments, regulation of complex gene networks can be achieved, enabling multi-gene synergistic improvements and advancing precision breeding in forage grasses.

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD1902500), the Inner Mongolia Seed Industry Science and technology innovation major demonstration project (2022JBGS0014), the National Center of Pratacultural Technology Innovation (under preparation) (CCPTZX2023B01), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32101428), the Taishan Scholar Program of Shandong, the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2021QC098), and Qingdao New Energy Shandong Laboratory of Key Projects Programs (Grant No. QNESL KPP202302).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization and review of this manuscript: Fu C, Liu M, Wang Z, Yuan F; literature collection and writing-original draft: Fu X, Liu M, Zhao W, Liu Y; supervision, editing and revising manuscript: Fu C, Liu M. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Fu X, Zhao W, Wang Z, Yuan F, Liu Y, et al. 2024. The progress of genetic improvement of forage grasses through transgenic approaches. Grass Research 4: e027 doi: 10.48130/grares-0024-0025

The progress of genetic improvement of forage grasses through transgenic approaches

- Received: 07 November 2024

- Revised: 06 December 2024

- Accepted: 10 December 2024

- Published online: 25 December 2024

Abstract: Forage grasses, characterized by their broad ecological adaptability, are commonly cultivated as pasture, grazing, and hay crops for ruminant production. Transgenics, a cutting-edge technology, has been utilized to produce commercial grain and oil crops with desired traits since 1996. However, this advanced breeding technique has seen limited application in forage grasses due to their polyploidy complexity, large genomes, self-incompatibility, and extremely low transformation efficiencies. Over the past decade, various innovative transgenic approaches have been established and developed for forage grasses. This paper summarizes the research advancements in the genetic improvement of forage grasses through transgenic methods. The technologies involved in identifying and manipulating target genes are comprehensively reviewed. Additionally, opportunities and challenges of transgenics in forage grass improvement are discussed. With the establishment and application of novel transgenic technologies, new forage grass cultivars with high biomass yield, improved forage quality, and enhanced stress resistance are expected to be developed in the near future. These advancements could potentially alleviate the pressure from global and local demands for nutritious food and environmental security in the coming years.

-

Key words:

- Forage grasses /

- Genetic improvement /

- Transgenics /

- Gene identification /

- Gene manipulation