-

Drought stress is one of the crucial factors affecting plant growth and physiological processes. Drought tolerance is associated with a series of morphological and physiological changes, such as the accumulation of cuticular wax, osmoregulation, partial stomatal closure, and water uptake capacity through the roots in plants[1−4]. Cuticular wax is a protective barrier covering the above-ground surfaces of terrestrial plants[5]. It accumulates on the leaf surface during water-scarce conditions, effectively preventing non-stomatal water loss and maintaining the higher leaf water status, thereby enhancing the drought tolerance of plants[6,7].

The protective functions of the cuticular wax are determined by their biochemical composition which is complex in plants[8−10]. The cuticular wax is primarily composed of mixtures of very-long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) and their derivatives, including alkanes, ketones, aldehydes, primary and secondary alcohols, and acid derivatives[11]. Several studies have demonstrated that abiotic stresses can alter the composition of plant cuticular wax, particularly influencing the levels of alkanes, aldehydes, secondary alcohols, and fatty acids[12−14]. Furthermore, specific compositions of cuticular wax have been associated with drought tolerance[15]. For instance, genotypes with higher levels of alkanes generally exhibit enhanced performance under drought conditions compared to genotypes with lower wax content[16]. Similarly, in rice (Oryza sativa), a decrease in the content of alkanes, aldehydes, primary alcohols, and fatty acids within the cuticular wax was associated with decreased drought tolerance[17].

The biosynthesis and deposition of plant cuticular wax is a complex process that is influenced by both wax content and composition[11,14]. Multiple genes were involved in wax metabolic pathways[18]. During the biosynthesis stage, the content and composition of the cuticular wax are regulated by either the activity of key biosynthetic enzymes or the transcriptional levels of relative genes[19]. Among them, β-Ketoacyl-CoA Synthase (KCS), Eceriferum 1 (CER1), Wax Synthase Dioxygenase 1 (WSD1), and Glossy1 gene (GL1) are involved in cuticular wax biosynthesis[17,20−22]. These genes encode specific enzymes that catalyze the conversion of fatty acid precursors into cuticular wax components, thereby determining the type and quantity of cuticular wax[23,24]. Additionally, the transport pathway of cuticular wax is also a crucial aspect. The ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) Transporter Family plays a key role in this process which is responsible for exporting the synthesized cuticular wax to the plant cuticle and forming the wax layer on the plant surface[25]. Additionally, some transcription factors, such as WAX INDUCER1/SHINE1 (WIN1/SHN1), Ethylene-responsive transcription factor 2 (ERF2), and MYB-related gene 96 (MYB96) can also activate wax biosynthesis[26,27]. Studies have shown that drought stress can induce upregulation of the expression levels of genes related to cuticular wax metabolism in various plants, such as in wheat (Triticum aestivum), Arabidopsis thaliana, and alfalfa (Medicago sativa), thereby enhancing plants' drought resistance[28−30].

Centipedegrass (Eremochloa ophiuroides (Munro) Hack.) is one of the important warm-season turfgrass species. It is characterized by its developed stolons, long growing period, and low management input[31,32]. These advantages allow for its extensively utilized for green lawns, slope protection, and environmental remediation[33−35]. Furthermore, centipedegrass exhibits a pronounced tolerance to a variety of biotic and abiotic stresses, with a particular resilience to drought conditions[33,36]. Previous studies suggested that drought tolerance of centipedegrass might be associated with physiological factors, including root system growth, water retention capacity, chlorophyll content, proline content, and membrane stability[37−41]. However, research exploring the drought tolerance of centipedegrass from the perspective of leaf cuticular wax remains unknown.

Based on our previous study in centipedegrass, 'CG101' was superior to 'CG021' in drought tolerance[42]. Nevertheless, the differential mechanisms underlying these two genotypes in response to drought stress are not yet fully understood. The objectives of the present study were to: (i) compare differences in water retention capacity between the two genotypes, and (ii) elucidate the mechanisms of the differential drought tolerance from the levels of leaf cuticular wax accumulation and composition. The findings will provide a foundation for further exploration of the molecular mechanisms of drought tolerance and offer novel insights for breeding drought-tolerant cultivars in centipedegrass.

-

Sods of the drought-sensitive 'CG021' and the drought-tolerant 'CG101' were sampled from the Turfgrass Resource Nursery at Nanjing Agricultural University (Nanjing, China), and transplanted into PVC tubes (11 cm diameter and 50 cm depth) filled with peat soil. Plants were established for 60 d in a temperature-controlled greenhouse set at 30/25 °C (day/night), 60% relative humidity, and 14-h photoperiod (800 μmol/m2/s). Plants were clipped weekly to about 5 cm, watered every 3 d, mowed every 2 d, and fertilized once per week with water-soluble fertilizer (Scotts Miracle-Gro Company, USA). After root and canopy establishment, plants were moved into a growth chamber for one-week acclimation before treatments. The growth chamber was set at 30/25 °C (day/night), 70% relative humidity, and a 14-h photoperiod (600 μmol/m2/s).

Experimental design

-

All plants were established in PVC tubes and thoroughly watered before treatments. Subsequently, each genotype was subjected to two treatments: (i) the well-watered control, that plants were watered every 2 d, and (ii) drought stress, that irrigation was ceased until 24 d, then followed by a period of post-drought recovery through re-watering every 2 d. Each treatment was replicated five times, with each genotype being represented in five PVC tubes. During the experimental period, PVC tubes were placed in a growth chamber under environmental conditions identical to those of the acclimation period. The positions of all PVC tubes were reallocated every 2 d to avoid environmental differences.

Measurements of physiological indices

-

Soil water content (SWC) was monitored by a time domain reflectometry (Mini Trase Kit 6050X3, Soil Moisture Equipment Corp., Santa Barbara, CA, USA). During the experimental time at 0, 6, 12, 18, 24, re-1 (rehydration for 1 d), and re-6 (rehydration for 6 d) d, a 20 cm soil moisture sensor probe was fully inserted into the PVC tube until it was completely submerged in the soil. Data of SWC was rapidly recorded.

For leaf relative water content (RWC), the third fully expanded leaves from the apex of upright stems were excised and immediately weighed for fresh weight (FW). Samples were then moved into tubes with deionized water and kept in the dark at 4 °C for 12 h. Leaves were blotted dry and immediately weighed for turgid weight (TW). Subsequently, leaf samples were placed in an oven at 80 °C for 72 h to achieve a completely dried state, and the dry weight (DW) was measured[43]. Leaf RWC was calculated based on the following formula:

$ \rm{RWC\;({\text{%}})=[(FW - DW)/(TW - DW)]\times 100} $ To measure the rate of water loss (RWL) and the rate of water absorption (RWA), the third fully expanded leaves from the apex of upright stems were excised (0.25 g) and immediately weighed for the FW. Then, samples were moved into a growth chamber with a temperature of 25 °C and 50% relative humidity. Subsequently, leaves were weighed at 30, 60, 120, 180, 240, 300, 360, and 420 min, respectively, to obtain the dehydrated weight (Wt)[44]. For the RWA, detached leaves after 270 min of dehydration were weighed, and recorded as the initial weight (WD). Then, these leaves were re-immersed into centrifuge tubes filled with water. At the time points of 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, and 140 min, water on the surface of leaves was removed. Then, leaves were immediately weighed to obtain the absorption weight (WA)[45]. After dehydration was completed, leaves were dried, and dry weight was measured. The RWL and RWA were calculated based on the following formula:

$ \rm{RWL\; (g\cdot g}^{-1}\, DW\cdot min^{-1})=(FW-Wt)/(DW\times T) $ $ \rm{RWA\; (g\cdot g}^{-1}\, DW\cdot min^{-1})=(WA-WD)/(DW\times T) $ where, FW is the fresh weight, Wt is the weight at a specific time point during dehydration, DW is the dry weight, WA is the weight after absorption, WD is the initial weight before absorption, and T is the time interval in minutes.

Cuticular wax extraction and composition analyses

-

Leaf wax content (LWC) was determined following the method of Yu et al.[46]. The third fully expanded leaves with a similar length from the apex of upright stems were excised from mature plants. At 0, 20, and re-6 d, 0.25 g of leaves were collected for wax determination. The leaves were immediately weighed for the initial fresh weight (FW0), and then immersed in 30 mL chloroform for 15 s to obtain the extract. After evaporating the extract in a boiling water bath, the leaves were weighed again for the final fresh weight (FW1). Then, leaves were placed in an oven at 80 °C for at least 72 h, and the dry weight (DW) was measured. LWC was calculated based on the following formula:

$ \rm{LWC\; (mg\cdot g}^{\mathrm{-1}})=(FW_0-FW_1)/DW $ The cuticular wax composition was conducted at 24 d of the experiment. The third fully expanded leaves (0.35 g) with a similar length were taken from the apex of upright stems and collected for GC/MS analysis at Nanjing Innovation Biotech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China), following the method with some modifications[47]. After freeze-drying the sample in a 50 mL centrifuge tube, 10 mL of a chloroform/methanol mixture (volume ratio of 3:1) was added and extracted at room temperature for 45 s. The extract was then dried using a vacuum concentrator (CV200, Beijing JIAIMU Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Subsequently, the dried wax mixtures were dissolved in 20 μL of N, O-Bis(trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) and 20 μL of pyridine incubated for 45 min at 70 °C. The derivatives were redissolved in 1 mL of chloroform and filtered through a 0.45 μm organic membrane into a 2.0 mL brown autosampler vial.

Cuticular wax was identified by a GC-MS/MS (TSQ™ 9000 Triple Quadrupole Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry, Thermo Fisher, USA). A HP-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) was used to separate leaf wax, with helium as carrier gas (purity greater than 99.999%) at a flow rate of 3.0 mL/min. The injector temperature was set at 250 °C, and the injection volume was 1 μL in splitless mode. The initial tank temperature was 50 °C, which was then increased at a rate of 8 °C/min to 120 °C, and finally increased at a rate of 5 °C/min to 300 °C, where it remained for 15 min. Mass spectrometry parameters were set as follows: ion source temperature, 230 °C; quadrupole temperature, 150 °C; electron impact (EI), 70 eV. Mass spectra from 50 to 850 m/z were recorded in full scan mode. Compounds in each sample were identified by matching their mass spectra with the NIST/EPA/NIH Mass Spectral Library 2020 (NIST 2020).

RNA preparation and gene expression analysis

-

For expression pattern analysis of genes associated with drought response, leaf tissues (0.05 g) were collected from 'CG021' and 'CG101', respectively, after 24 d of drought treatment. RNA was extracted using the FastPure Plant Total RNA Isolation Kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., China). The quantity and integrity of the RNA samples were assessed with the Tecan Infinite 200 pro (Grödig, Austria). RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the HiScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (+ gDNA wiper) (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., China).

The obtained cDNA solution was subjected to analysis of gene expression level by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). qRT-PCR was performed using ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Without ROX) (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., China) on the Roche LightCycler480 II machine (Roche Diagnostic, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). The reaction mixture consisted of the following: primer 0.5 μL, 2 × ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Without ROX) 7.5 μL, cDNA 2 μL, and finally supplemented with ddH2O to 15 μL. The PCR conditions were set as follows: an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles, each consisting of 10 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 60 °C. The primer information is shown in Table 1. The levels of relative gene expression were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method.

Table 1. Sequences of primers used in this study.

Primer name Forward primer (5'-3') Reverse primer (5'-3') EoMD CTCTGATCCATCGAGTCACATTAC GAGGGAAGCTCTGATGTTCATT EoCER1 ATGAACTACCTGGGGCACTG TAGAGGTCGTCGCTGGACTT EoKCS6 GGTACGAGCTCGCCTACATC TCTCCACGACCACATACCAA EoGL1 GTCCACACGCCTTCATTTTT TGTAGAAGCCGAGGTTGTCC EoWSD1 TGATTGGTCCAGTTGAGCAG GCTTGAGGGATTCAGCAAAG EoBCG11 TCTACCGCCTGCTCTTCTTC CAGTTCCGGTTTAGCCTTTG EoPDR8 CTCTGATCCATCGAGTCACATTAC GAGGGAAGCTCTGATGTTCATT Statistical analysis

-

Data were analyzed with SPSS 26.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical differences of RWL and RWA were determined using Student's t-test. The data for different treatments were analyzed with one-way Analysis of Variance. In the line graphs, the Least Significant Difference (LSD) at a confidence level of 0.05 was performed to compare significant differences between treatments. In the bar graphs, all measured parameters were described by the means ± standard error (SE), and Duncan's test was conducted to distinguish significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05). All graphs were created with Sigmaplot 14.0.

-

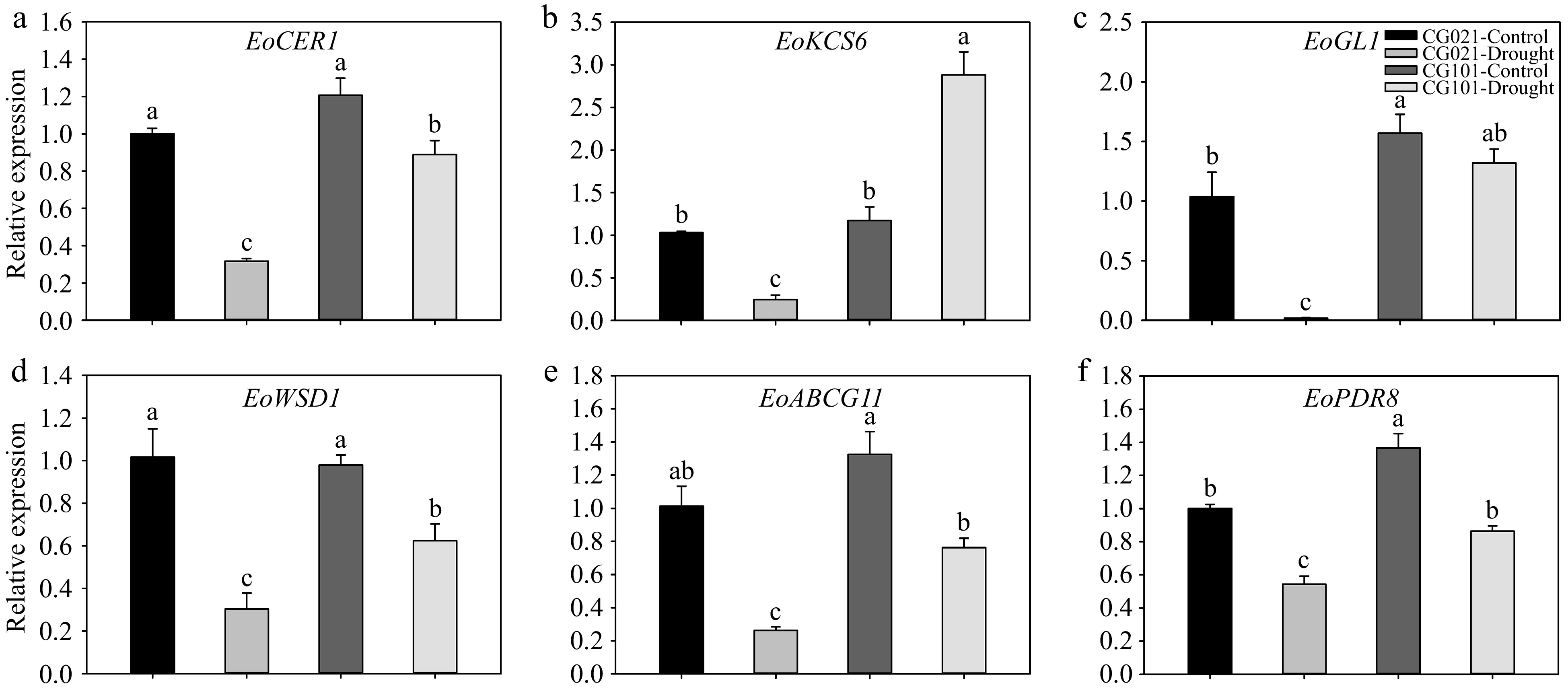

At the beginning of the treatments (0 d), both genotypes grew under a similar SWC of approximately 30% (Fig. 1). Under drought conditions, SWC reached the lowest point of 5.05%~6.88% for both genotypes at 24 d and returned to pre-drought stressed level following 1 d of post-drought re-watering. During the drought stress and post-drought recovery, no genotypic differences in SWC were observed, indicating that all plants were exposed to the same level of soil water status throughout the experiment.

Figure 1.

Soil water content in the drought-sensitive 'CG021' and the drought-tolerant 'CG101' during the experiment. Bars on the top indicate LSD values for the comparison among treatments on a given day.

Leaf water changes in response to drought stress

-

Drought stress caused a drastic decrease in RWC of both genotypes after 6 d of drought treatment (Fig. 2a). However, the drought-tolerant 'CG101' had significantly higher RWC than the drought-sensitive 'CG021' from 12 to 24 d of drought treatment. At 24 d of drought treatment, the RWC of 'CG101' was maintained at 81.53%, while, the RWC of 'CG021' was significantly decreased to 29.52%. During the rehydration process, the RWC of 'CG101' recovered to the well-watered control level at 1 d, while 'CG021' only recovered to 33.99% of the well-watered control level. Even at 6 d of re-watering, the RWC of 'CG021' was only recovered to 51.76% of the well-watered control level.

Figure 2.

(a) Relative water content, (b) rate of water loss, and (c) rate of water absorption in the drought-sensitive 'CG021' and the drought-tolerant 'CG101' during the experiment. Vertical bars indicate LSD values for the comparison among treatments on a given day. Error bars indicate the standard error (SE). Asterisks indicate significant differences (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001) between different genotypes at a certain time point.

Under room temperature conditions, as the duration of natural dehydration in leaves increased, the RWL of excised leaves from both 'CG101' and 'CG021' exhibited a rapid decline after 60 min (Fig. 2b). During the entire experimental period, the RWL of the drought-tolerant 'CG101' was lower than the drought-sensitive 'CG021' by 6.64%, 17.3%, and 7.89% at 30, 60, and 420 min, respectively.

At the initiation of the rehydration (20 min), the RWA of both genotypes was highest compared to other time points (Fig. 2c). The RWA of both 'CG021' and 'CG101' rapidly declined with the duration of rehydration time. There were no significant differences in the RWA between the two genotypes during the rehydration process.

Accumulation of the cuticular wax in response to drought stress

-

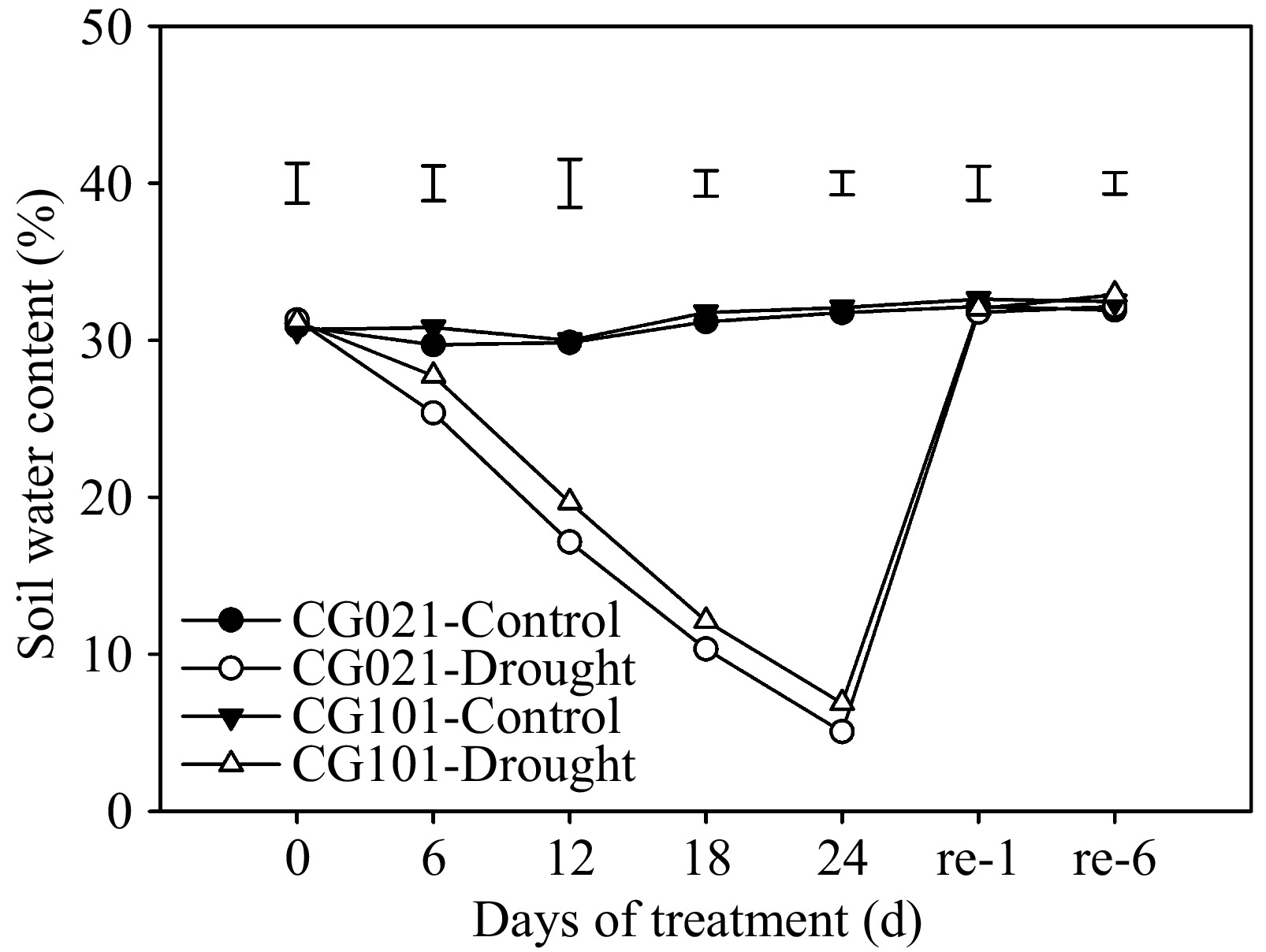

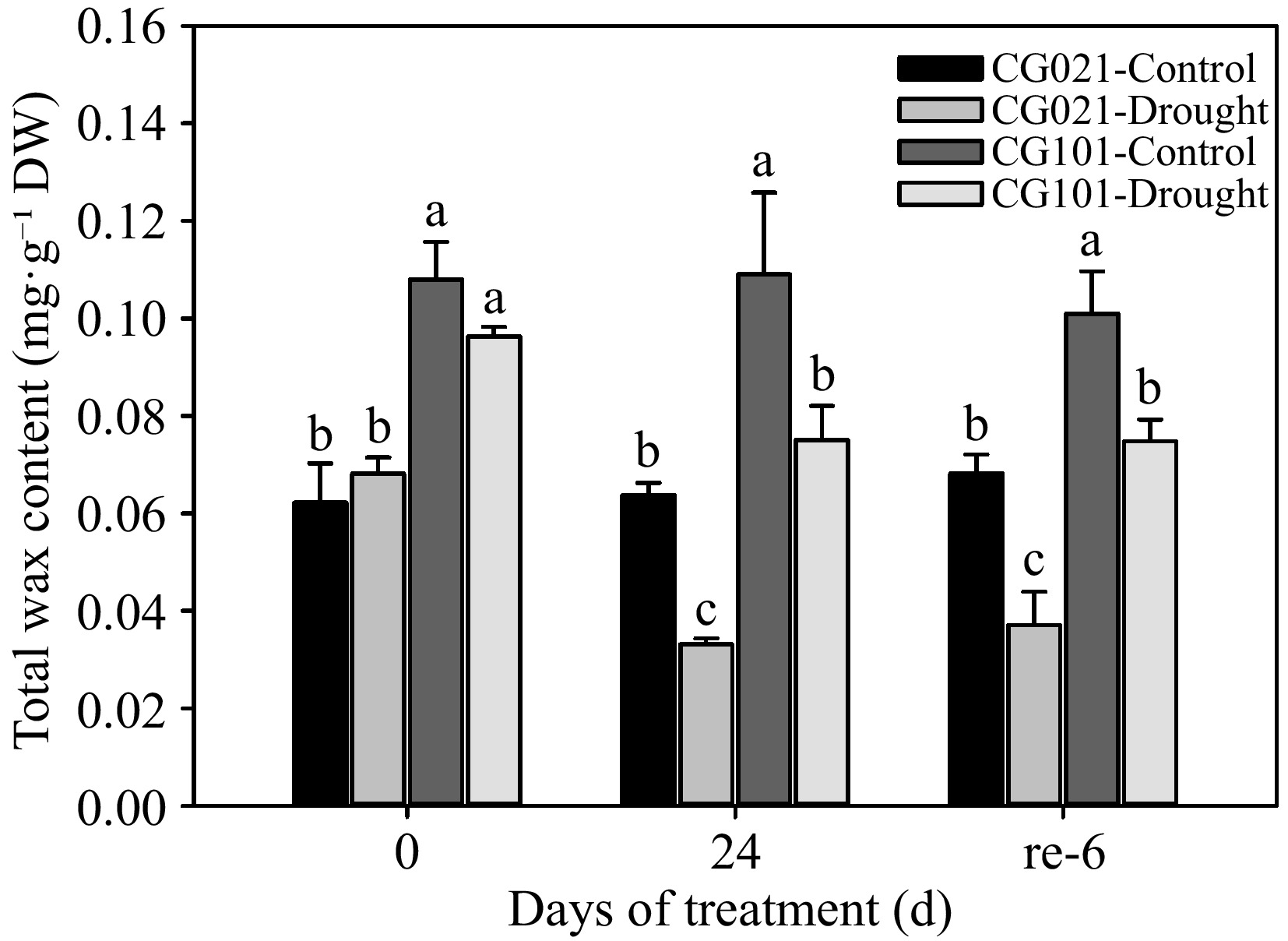

Under both well-watered, drought-stressed, and post-drought re-watered conditions, the LWC of the drought-sensitive 'CG021' was significantly lower than that of the drought-tolerant 'CG101' (Fig. 3). When plants were exposed to drought stress, the LWC decreased by 47.93% in 'CG021' and 31.12% in 'CG101', respectively, compared with the well-watered control level at 24 d. Upon re-watering for 6 d, the LWC of both genotypes did not recover to the well-watered control level.

Figure 3.

Leaf wax content in the drought-sensitive 'CG021' and the drought-tolerant 'CG101' during the experiment. Different letters indicate significant differences between different treatments at a certain point in time (p < 0.05).

Composition of the cuticular wax in response to drought stress

-

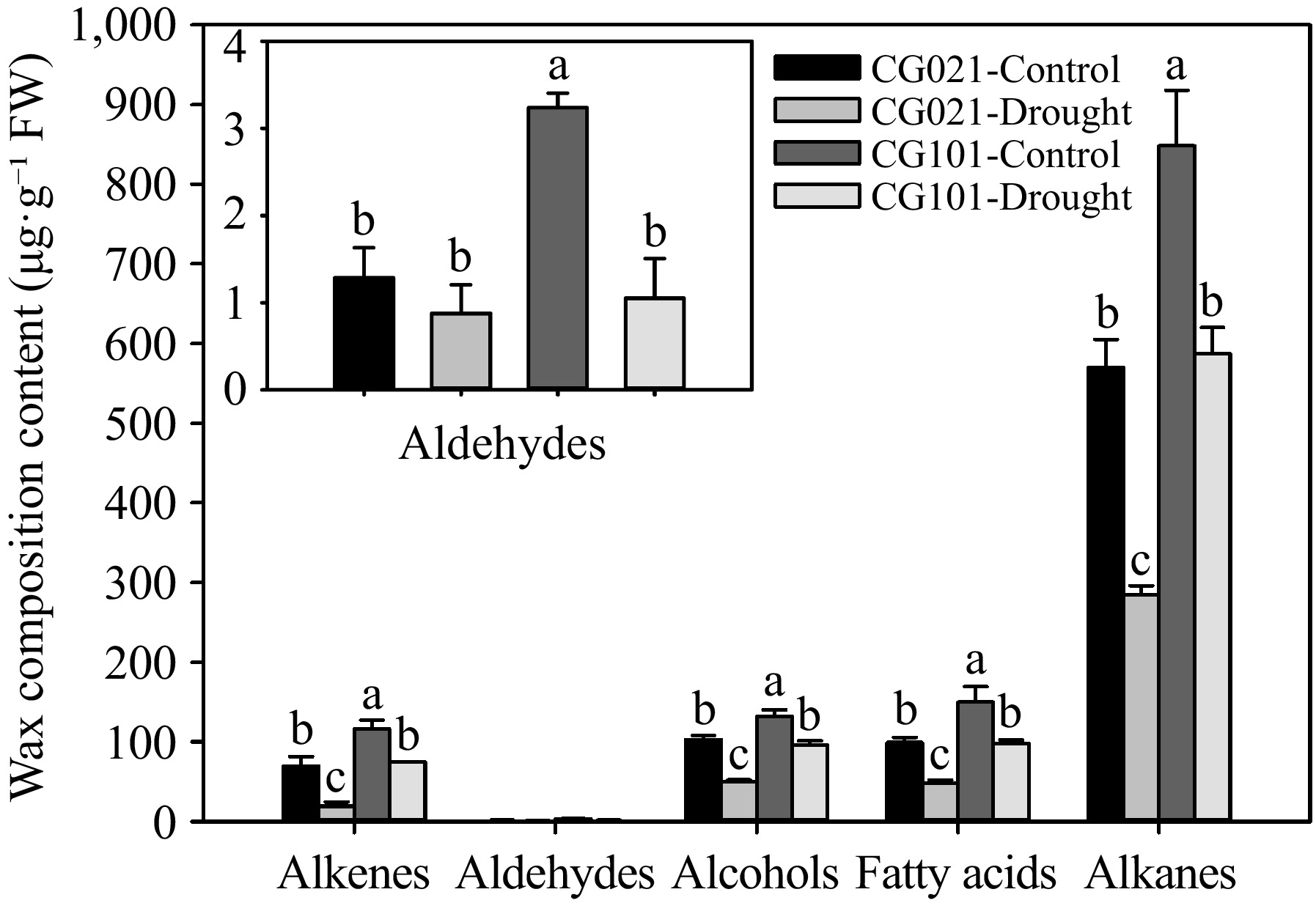

The cuticular wax compositions were predominantly composed of alkenes, aldehydes, alcohols, fatty acids, and alkanes at 24 d of drought stress in centipedegrass (Fig. 4). The content of alkanes was the highest, ranging from 570.17 to 848.23 μg·g−1 FW. Except for aldehydes, the cuticular wax compositions in both genotypes exhibited a significant decline after 24 d of drought stress. The levels of alkenes, alcohols, fatty acids, and alkanes were significantly lower by 73.97%, 47.44%, 51.17%, and 51.59%, respectively, in the drought-sensitive 'CG021' compared to the drought-tolerant 'CG101' under drought stress.

Figure 4.

The cuticular wax composition in the drought-sensitive 'CG021' and the drought-tolerant 'CG101' after 24 d of drought stress. Different letters indicate significant differences between different treatments (p < 0.05).

Carbon chain length of the cuticular wax composition in response to drought stress

-

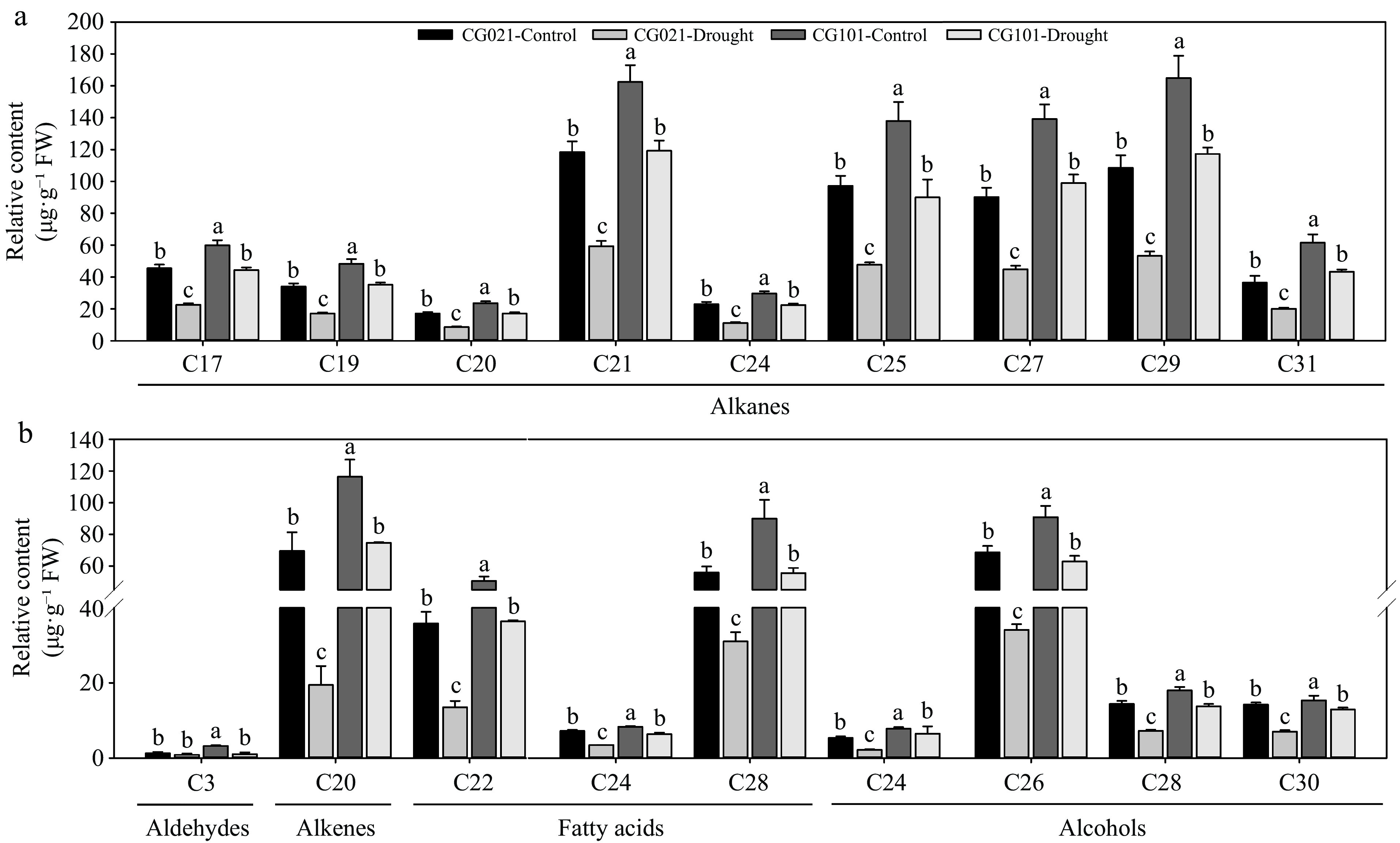

Compared with control plants, the drought-treated 'CG021' and 'CG101' exhibited decreases in the content of C17~C31 alkanes, C20 alkenes, C22, C24, and C28 fatty acids, and C24, C26, C28, and C30 alcohols (Fig. 5). However, drought-induced decline in the content of all carbon chain lengths was more pronounced in 'CG021' compared to 'CG101'. Under both well-watered and drought conditions, the content of alkanes, alkenes, fatty acids, and alcohols in 'CG021' was consistently lower than in 'CG101'. For C3 aldehydes, drought stress caused a decrease in 'CG101' but without change in 'CG021' (Fig. 5b). Increase was observed in control plants of 'CG101' compared to 'CG021' but not in drought-treated plants. Under drought stress, no significant difference was found in the two genotypes (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

The carbon chain length of the cuticular wax composition in the drought-sensitive 'CG021' and the drought-tolerant 'CG101' after 24 d of drought stress. Different letters indicate significant differences between different treatments (p < 0.05).

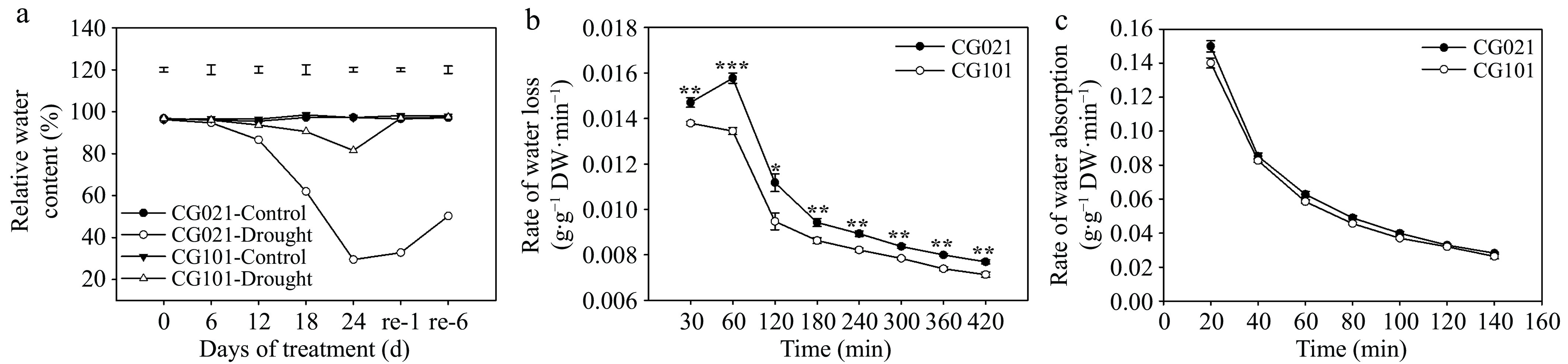

The relative expression of cuticular wax-related genes in response to drought stress

-

In 'CG101', drought stress led to a decrease in EoCER1, EoWSD1, EoABCG11, and Pleiotropic Drug Resistance protein 8 (EoPDR8), but an increase in EoKCS6 (Fig. 6a, b, d−f). In 'CG021', drought stress caused a significant decrease in the expression of EoCER1, EoKCS6, EoGL1, EoWSD1, EoABCG11, and EoPDR8 by 68.39%, 76.19%, 95.04%, 70.15%, 74.05%, and 45.65%, respectively, compared with the control (Fig. 6). Moreover, the reduction in expression level of EoCER1, EoWSD1, EoABCG11, and EoPDR8 was more pronounced in 'CG021' compared to 'CG101' (Fig. 6a, d−f). Under well-watered control, the expression level of EoCER1, EoGL1, and EoPDR8 was lower in 'CG021' than 'CG101' (Fig. 6a, c, f). Under drought stress, the expression level of each gene was higher in 'CG101' compared to 'CG021' (Fig. 6).

-

Plants maintain their essential water balance by reducing water loss, which is vital for physiological and biochemical activities under drought-stressed conditions[48,49]. Generally, drought-tolerant genotypes lose less water and maintain higher RWC than drought-sensitive genotypes under drought conditions[50,51]. In this study, although both genotypes of centipedegrass had significant reduction in RWC after 24 d of drought stress (Fig. 2a), the drought-tolerant 'CG101' showed a smaller decrease in RWC than the drought-sensitive 'CG021' under the same soil water level (Figs 1 & 2a). The greater leaf RWC in 'CG101' mainly resulted from the lower RWL, but not related to RWA (Fig. 2b, c). This finding was fully consistent with our previous study conducted in 'CG101' and 'CG021' of centipedegrass[42]. The greater RWC in the drought-tolerant 'CG101' was attributed to the cuticular wax in leaves, which was closely associated with leaf RWL, as discussed below.

The cuticular wax plays a protective role for plants against injuries caused by stressed environments[52]. Its content, composition, and morphology are also affected by drought stress[53]. Many studies have shown that drought stress alters the content of cuticular wax in various plants, such as in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), peanuts (Arachis hypogaea), rice, corn (Zea mays), and Arabidopsis thaliana[21,54−57]. In our study, it was observed that drought stress decreased the leaf wax content of both centipedegrass genotypes, however, the drought-tolerant 'CG101' had a significantly higher leaf wax content than the drought-sensitive 'CG021' (Fig. 3). Generally, plants with larger cuticular wax have the superior drought tolerance[50,58,59]. For example, drought-tolerant wheat cultivars with higher cuticular wax content exhibited better growth and higher RWC, indicating that wax-rich plants could enhance drought tolerance by maintaining higher water content[60]. In chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium), the greater content of wax was detected by regulating non-stomatal transpiration in drought-tolerant cultivars compared with drought-sensitive ones[50]. Therefore, the higher cuticular wax content in leaves of 'CG101' under drought stress could effectively reduce RWL by decreasing transpiration, thereby enhancing the RWC of the drought-tolerant 'CG101' in this study.

Apart from the leaf wax content, plants can synthesize various cuticular wax compositions, including alkanes, alkenes, aldehydes, fatty acids, and alcohols, to adapt to the drought-stressed environments[53,57]. Among them, the alkane synthesis in leaf wax is closely associated with water availability and has important influences on epidermal water loss[10,61]. Plants deficient in alkanes were reported to be incapable of effectively reducing transpiration under drought stress, which consequently resulted in leaf mortality and impeded post-drought recovery[24]. Nevertheless, VLCFAs were found to be more important than alkanes for drought adaptation in rice[17,57]. Additionally, the accumulation level of alcohol mixtures played a key role in reducing non-stomatal water transpiration[62]. Our study found that the content of C20 alkenes, C17~C31 alkanes, C22, C24, and C28 fatty acids, as well as C24, C26, C28, and C30 alcohols was lower in leaves of the drought-sensitive 'CG021' compared to the drought-tolerant 'CG101' under drought stress (Figs 4 & 5). These results suggested that the drought-resistant function of wax compositions might be not dominated by a single substance but relied on the synergistic effects of multiple compositions. For example, in the drought-tolerant 'Ningqi I' goji (Lycium barbarum), the content of alkanes, alcohols, esters, and fatty acids in leaf wax was significantly higher than in sensitive cultivars, and the enhanced wax accumulation in leaves of 'Ningqi I' significantly decreased the non-stomatal water loss[63]. In Arabidopsis, the MYB96 transcription factor could simultaneously activate alkane and alcohol synthesis pathways. MYB96-overexpressed lines exhibited improved drought tolerance due to the optimized total content and composition of wax[64]. Ectopic overexpression of CsECR increased the content of total wax and aliphatic wax fractions (fatty acids, alkanes, and alkenes) in the leaves and fruits of the transgenic tomato (Solanum lycopersicum)[65]. Therefore, we speculated that the higher cuticular wax content of alkenes, alcohols, alkanes, and fatty acids in this study might be directly responsible for the greater RWC in the drought-tolerant 'CG101' under drought conditions, thereby improving the drought tolerance of 'CG101'.

The biosynthesis and transport pathways of plant epidermal wax are a complex network involving the coordinated actions of several genes[66]. In Arabidopsis, the genes KCS6, GL1, and WSD1 have been reported to be involved in wax synthesis[20−22]. The CER1 gene has been found to function in wax biosynthesis and enhance the resilience to drought stress in rice[17]. In addition, research on Arabidopsis has revealed that the ABC transporter, known as DESPERADO, plays a crucial role in transporting cutin and wax to the extracellular matrix[25]. The ABCG11 of this study is one of ABC transporter family protein genes with a positive function in leaf wax transport[67]. The involvement of ABC genes associated with wax deposition has also been observed in moss (Physcomitrella patens), corn, and barley (Hordeum spontaneum)[68−70]. In the current study, the PDR8 is another member of the ABC transporter family[71]. In rice, the Osmyb60 loss-of-function mutant downregulated the expression of wax metabolic genes, such as OsPDR9, and OsCER1, including OsPDR8 under normal growth conditions, and reduced the total wax content on the leaf surface[17]. In the present study, it was observed that the transcription levels of wax metabolic genes EoCER1, EoKCS6, EoGL1, EoWSD1, EoABCG11, and EoPDR8 were higher in leaves of 'CG101' than those of 'CG021' (Fig. 6), contributing to the greater accumulation of the cuticular wax in the drought-tolerant 'CG101' than the drought-sensitive 'CG021' in centipedegrass under drought stress.

-

In the present study, drought stress led to a reduction in leaf water in both the drought-tolerant 'CG101' and the drought-sensitive 'CG021' of centipedegrass. However, 'CG101' exhibited strong water retention capacity as indicated by lower RWL and higher RWC than 'CG021'. The enhanced water retention in 'CG101' was associated with the cuticular wax content and composition. The greater content of cuticular wax in 'CG101' was mainly attributed to the higher expression level of wax metabolic genes, including EoCER1, EoKCS6, EoGL1, EoWSD1, EoABCG11, and EoPDR8. The increased cuticular wax composition was related to alkenes, alcohols, alkanes, and fatty acids in leaves of 'CG101'. Further study will focus on the function analysis of candidate genes involved in wax metabolic pathways through transgenic approaches to clarify the underlying molecular mechanisms.

This work was supported by the Breeding of New Varieties Evergreen Grass in Yangtze River Delta (ZA32303), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (KYPT2024006).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization and methodology: Yu J; data curation: Gao J, Li Q; investigation: Gao J, Hao T, formal analysis: Gao J, Fan N; writing – original draft: Gao J, Yu J; funding acquisition: Yu J, Yang Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Gao J, Hao T, Li Q, Fan N, Yang Z, et al. 2025. Water retention capacity in association with the accumulation and composition of cuticular wax contributing to drought tolerance in centipedegrass. Grass Research 5: e015 doi: 10.48130/grares-0025-0012

Water retention capacity in association with the accumulation and composition of cuticular wax contributing to drought tolerance in centipedegrass

- Received: 30 January 2025

- Revised: 01 April 2025

- Accepted: 03 April 2025

- Published online: 13 May 2025

Abstract: Centipedegrass is one of the most important warm-season turfgrasses with the advantages of strong stolons, long growing season, and low input requirements. Previous research found that the two genotypes of centipedegrass (the drought-tolerant 'CG101' and the drought-sensitive 'CG021') exhibited differential drought tolerance. The objectives of this study were to: (i) compare differences in water retention capacity between the two genotypes, and (ii) elucidate the mechanisms of the differential drought tolerance from the levels of leaf cuticular wax accumulation and composition. Plants were exposed to 24 d of drought stress and post-drought re-watered for 6 d. The findings indicated that 'CG101' exhibited superior drought tolerance, as reflected by the greater water retention capacity in comparison with 'CG021'. The enhanced water retention in 'CG101' was attributed to a lower rate of leaf water loss, which resulted from a higher cuticular wax accumulation and composition in leaves compared to 'CG021'. The increased cuticular wax content was associated with higher expression levels of genes related to wax metabolism, including EoCER1, EoKCS6, EoGL1, EoWSD1, EoABCG11, and EoPDR8 in 'CG101' under drought stress. The accumulation of the cuticular wax composition in 'CG101' involved alkenes, alkanes, alcohols, and fatty acids. Our results will provide a foundation for breeding drought-resistant cultivars in centipedegrass.

-

Key words:

- Water retention /

- Drought stress /

- Centipedegrass /

- Cuticular wax