-

China's floral industry has experienced rapid development over the past four decades, achieving significant accomplishments. However, the sector still heavily relies on imported germplasm resources. Therefore, the development of indigenous new floral cultivars is essential for the industrialization and autonomy of China's floral sector. Primulina, native to China, is one of the country's unique floral resources. Primulina species exhibit remarkable floral diversity in both coloration and morphology, with prolonged flowering periods and some cultivars capable of blooming multiple times annually. Several species feature distinctive white-variegated foliage. Characterized by shade tolerance, drought resistance, and ease of cultivation, they possess high horticultural value as indoor potted plants, representing excellent native floral resources in China[1]. These traits not only establish them as ideal ornamental plants but also confer significant commercial potential for large-scale cultivation and market development. Currently, the market offers rather limited indoor floral options. The commercial Primulina cultivars that we have independently cultivated possess strong adaptability and offer both ornamental flowers and foliage, making them ideal superior alternatives for indoor ornamental plants.

The Gesneriaceae comprises numerous genera, with key representatives including Primulina, Chirita, Haberlea, and Saintpaulia. The genus Primulina (Gesneriaceae) is classified as a nationally protected wild plant due to its limited distribution, small population size, and specialized habitat requirements[2]. The genus Primulina was first established in 1883, initially comprising only a single species, Primulina tabacum. Through subsequent taxonomic revisions, the genus was expanded to incorporate partial species from Chirita and Chiritopsis, along with two species from Wentsaiboea. A comprehensive revision in 2011 redefined Primulina to encompass over 130 species[3].

Following years of research and taxonomic revisions, Primulina has emerged as the most species-rich genus within the Gesnerioideae subfamily. In recent years, numerous new species have been discovered in southern China[4]. Primulina species are distinguished by their vibrant flower colors, unique leaf patterns, high adaptability, and significant ornamental potential, positioning them as promising candidates for future development and breeding[5].

The propagation of Primulina can be broadly categorized into two methods: traditional seed propagation and asexual reproduction, the latter of which includes cutting, division, and tissue culture. While conventional propagation and cultivation techniques for Primulina are relatively well-established, they often result in issues such as trait segregation, low efficiency, and inconsistent offspring quality, which fail to meet the demands of commercial production[6].

In recent years, significant progress has been made in the conservation and genetic transformation of Primulina through the establishment of efficient and stable tissue culture systems. These systems have been developed via adventitious bud formation, providing effective theoretical and technical support for the process. Since Kukulczanda & Suszynska first demonstrated the strong regenerative capacity of African violet leaf explants[7], tissue culture research on Gesneriaceae plants has expanded globally. Research on tissue culture techniques of Primulina in China can be traced back to early studies on Chirita species. Huang first established a tissue culture system for Chirita tribracteata (now Primulina tribracteata), marking the beginning of domestic research in this field[8]. Subsequently, Liang optimized tissue culture protocols for two former Chirita species—Chirita fimbrisepala (now Primulina fimbrisepala) and Chirita pungentisepala (now Primulina pungentisepala)[9]. Although these studies were initially conducted under the traditional taxonomic system, their technical achievements remain integral to the early biotechnological research of Primulina following the taxonomic revision in 2011. To date, approximately 30 species of Primulina have been successfully cultured in vitro, including domestic species such as Chirita eburnean[10], Chirita fimbrisepala[9], and Chirita tribracteata[11], as well as international species like Primulina tamiana[12], Primulina tabacum[13], and Primulina dryas[14]. These studies provide a scientific basis for the conservation of wild Primulina resources.

Tissue culture techniques for Primulina plants have made significant progress. However, most studies, both domestically and internationally, have primarily focused on establishing tissue culture systems for wild germplasm resources of this genus, to provide effective theoretical and technical support for the conservation and genetic transformation of Primulina[15]. In recent years, new cultivars with high ornamental value and strong ecological adaptability have been developed, but research on these cultivars remains scarce. To date, no complete tissue culture system has been reported for hybrid Primulina cultivars. Currently, traditional propagation methods for Primulina, primarily based on cuttings, dominate commercial production. However, this approach often results in inconsistent offspring quality and increased disease susceptibility, making it less suitable for large-scale commercial cultivation. Since hybrid Primulina cultivars differ from wild species and among themselves, with significant genetic variation, the Primulina genus is large and genetically diverse, which can lead to considerable differences in propagation methods and efficiency. Therefore, establishing an effective tissue culture system for hybrid Primulina and applying it to commercialization is crucial.

The hybrid cultivars Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' and Primulina 'POP Corn' developed by our research group, are both internationally registered. Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' is notable as one of the first hybrid Primulina cultivars to be globally commercialized. The goal of this study is to establish a rapid propagation system of two hybrid cultivars. This system aims to develop efficient and high-quality cultivation and propagation techniques, ultimately enhancing the production efficiency and quality of new cultivars, and creating greater economic value.

-

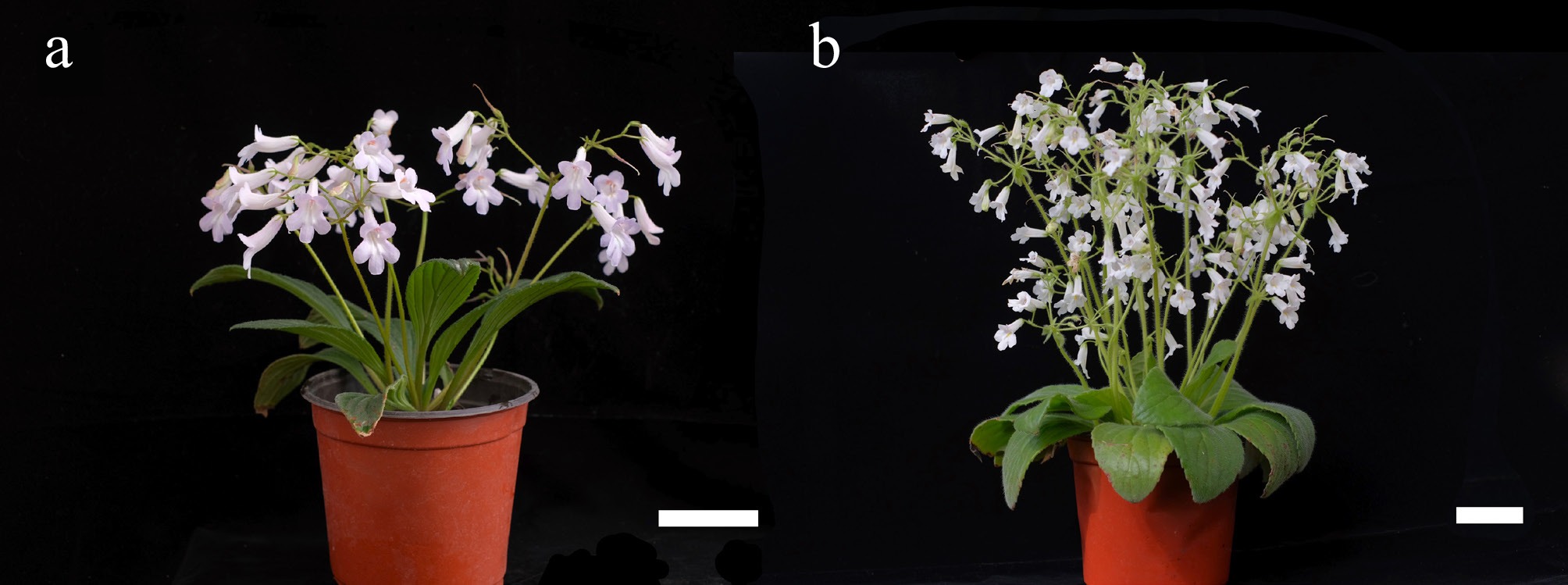

The hybrid cultivars Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' and Primulina 'POP Corn', both of these plants are diploid organisms. Furthermore, they are also both internationally registered and characterized by strong ornamental value and healthy growth, were propagated from 1-year-old seedlings. These plants were sourced from the greenhouse of the College of Horticulture, Beijing Forestry University, Daxing (China) (Fig. 1a, b).

Culture medium and culture conditions

-

The basic culture media used were MS and 1/2 MS, supplemented with different concentrations of NAA, 6-BA, and IBA according to the specific cultivation requirements. The media were further supplemented with 30 g/L sucrose, 6.0 g/L agar, and adjusted to a pH of 5.8−6.0. After inoculation, the explants were cultured under controlled conditions at 23 ± 2 °C, with a light intensity of 2,000−3,000 lx and a photoperiod of 16 h/d.

Surface sterilization of explants

-

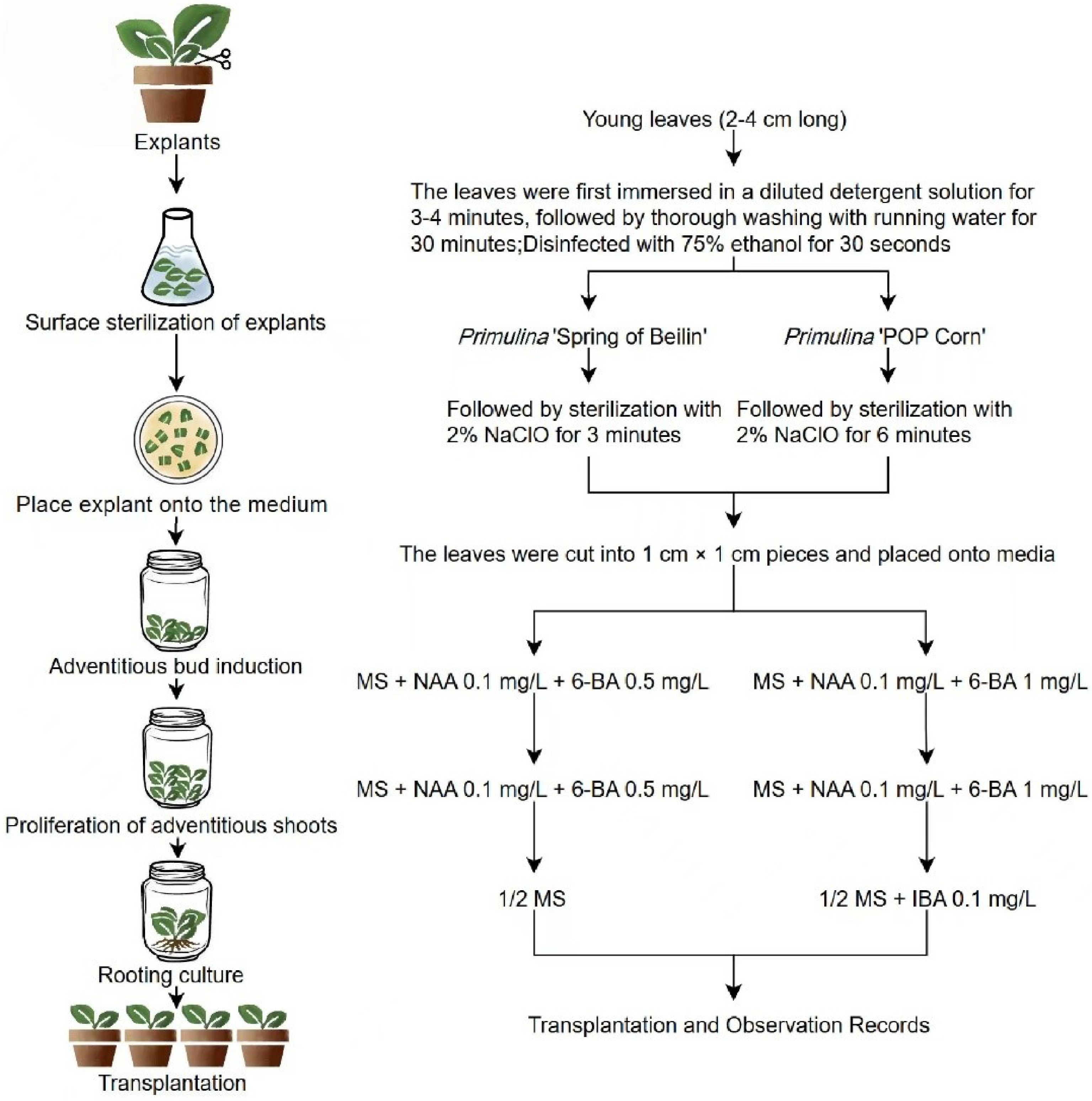

Healthy, pest-free plantlets with young leaves (2−4 cm long) from the apex of stems were selected. The leaves were first immersed in 1% (v/v) aqueous solution of household detergent (containing sodium lauryl benzene sulfonate [LAS] and alcohol ethoxylates [AE] as main surfactants) for 3−4 min, followed by thorough washing with running water for 30 min. The explants were then transferred to a laminar flow hood for sterilization. Initially, the leaves were immersed in 75% ethanol for 30 s and rinsed three times with sterile water. They were then sterilized in a 2% NaClO solution for 3−7 min, with gentle shaking to ensure complete contact with the solution. After sterilization, the explants were rinsed 3−5 times with sterile water, and excess moisture was removed using sterile filter paper. The leaves were then cut into 1 cm × 1 cm pieces and placed onto different media, with the adaxial side facing up and the abaxial side facing down. The contamination, browning, and survival rates were monitored for two weeks. The following parameters were calculated:

Browning rate (%) = (Number of browned explants/Total inoculated explants) × 100

Contamination rate (%) = (Number of contaminated explants/Total inoculated explants) × 100

Survival rate (%) = (Number of surviving, non-contaminated, and non-browned explants/Total inoculated explants) × 100

Screening of induction medium for adventitious buds

-

MS medium was used as the base, and different concentrations of NAA (0.1, 0.5, 1.5 mg/L) and 6-BA (0.5, 1.0, 2.0 mg/L) were tested. A total of 10 media were designed, including a control group (MS medium without plant growth regulators). Thirty leaf explants were inoculated on each medium, with three replicates per treatment. After 30 d of cultivation, the number of explants showing adventitious bud formation was recorded, and the adventitious bud induction rate was calculated as follows:

Induction rate (%) = (Number of explants forming adventitious buds/Total number of explants) × 100

Screening of proliferation medium for shoot clusters

-

The basic culture medium was MS, supplemented with various concentrations of NAA (0.1, 0.5, 1.5 mg/L) and 6-BA (0.5, 1.0, 2.0 mg/L), resulting in 10 different media, including the control group (MS medium without plant growth regulators). Explants that produced adventitious buds were transferred to these media for proliferation. Thirty adventitious shoots were inoculated per medium, with three replicates per treatment. After 30 d of cultivation, the propagation coefficient was calculated as follows:

Propagation coefficient = (Number of new shoots/Number of inoculated buds)

Rooting culture and transplantation

-

1/2 MS medium was used as the base for rooting, with different concentrations of IBA (0.1, 0.5, 1 mg/L) or NAA (0.1, 0.5, 1 mg/L) added to prepare seven media, including the control group (1/2 MS medium without plant growth regulators). The proliferated shoots were then transferred to these rooting media for root induction. Thirty shoots were inoculated on each medium, with three replicates per treatment. After 30 d of cultivation, root development was observed, and the number of rooted plants as well as their growth conditions were recorded. The rooted plantlets were subsequently transplanted into a substrate composed of peat, perlite, and vermiculite (2:1:1, V:V:V) and cultured for 2 weeks. During this period, survival rates and plant growth were monitored. The rooting rate and survival rate were calculated as follows:

Rooting rate (%) = (Number of rooted plants/Total number of inoculated shoots) × 100

Survival rate (%) = (Number of surviving plants/Total transplanted plants) × 100

Statistical analysis

-

Data were processed using Excel 2010 software, and variance analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0. Duncan's multiple range test was used for post-hoc comparisons. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

-

The surface sterilization results for Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' explants (Table 1) indicated that as the treatment time with 2% NaClO increased, the browning rate gradually increased and the survival rate gradually decreased. Although no significant differences were observed in contamination rates, significant differences were found between browning and survival rates at treatment times of 3, 3.5, and 4 min. The best results were obtained with a 3-min treatment, which resulted in a contamination rate of 4.44% and a survival rate of 95.57%. After a 30-s 75% ethanol treatment, 3 min of 2% NaClO sterilization was determined to be the optimal sterilization protocol for Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' leaf explants.

Table 1. Effect of different sterilization time on leaves of Primulina 'Spring of Beilin'.

Treatment 75% Ethanol

treatment time (s)NaClO treatment

time (min)Explant

number (n)Browning

rate (%)Contamination

rate (%)Survival

rate (%)A1 30 3 30 0 a 4.44 ± 1.92 b 95.57 ± 1.96 a A2 30 3.5 30 17.77 ± 5.08 b 11.10 ± 1.90 a 71.13 ± 5.09 b A3 30 4 30 48.90 ± 8.40 c 13.33 ± 3.35 a 37.80 ± 10.18 c Values are presented as means ± standard error. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). Effect of different sterilization treatment times on the survival of Primulina 'POP Corn'

-

The surface sterilization results for Primulina 'POP Corn' explants (Table 2) indicated that as the treatment time with 2% NaClO increased, the browning rate also increased, with the 7-min treatment resulting in significantly higher browning at 23.33%. The contamination rate was significantly higher after 5 min of treatment with 2% NaClO, while the lowest contamination rate occurred after 6 min at 7.78%. The highest survival rate of 88.89% was observed with the 6-min treatment. Therefore, after a 30-s 75% ethanol treatment, 6 min of 2% NaClO sterilization was found to be the optimal sterilization protocol for Primulina 'POP Corn' leaf explants.

Table 2. Effect of different sterilization time on leaves of Primulina 'POP Corn'.

Treatment 75% Ethanol

treatment time (s)NaClO treatment

time (min)Explant

number (n)Browning

rate(%)Contamination

rate (%)Survival

rate (%)B1 30 5 30 1.11 ± 1.92 b 35.56 ± 8.39 a 63.33 ± 6.66 b B2 30 6 30 3.33 ± 3.33 b 7.78 ± 1.92 b 88.89 ± 3.85 a B3 30 7 30 23.33 ± 6.67 a 10.00 ± 3.33 b 66.66 ± 5.77 b Values are presented as means ± standard error. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). Adventitious bud induction

Effect of NAA and 6-BA combinations on adventitious bud induction in Primulina 'Spring of Beilin'

-

Significant differences were observed in the differentiation rates among the 10 treatments for adventitious bud induction in Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' (Table 3). Analysis revealed that the C2 treatment achieved a significantly higher differentiation rate of 95.56% compared to the other nine treatments, all of which exhibited rates below 85%. Growth analysis further indicated that the C2 treatment promoted significantly better growth than the others. At high concentrations of plant growth regulators, explants displayed yellowing, partial browning, and other adverse effects. The lowest differentiation rates and the poorest growth were observed in the C8, C9, and C10 groups, where the NAA concentration was 1.5 mg/L. Overall, the type and concentration of plant growth regulators were found to significantly influence both differentiation rates and growth conditions. Moderate concentrations supported faster and healthier growth, while higher concentrations showed inhibitory effects. Under the MS + NAA 0.1 mg/L + 6-BA 0.5 mg/L condition, the induction rate reached 95.59%, with buds that were small, dense, and green (Fig. 2a, b).

Table 3. Effect of NAA and 6-BA on adventitious bud induction in Primulina 'Spring of Beilin'.

Treatment NAA

(mg/L)6-BA

(mg/L)Explant

number (n)Differentiation

rate (%)Growth conditions C1 0 0 30 8.89 ± 3.85 f Poor growth; initial differentiation; small, sparse, yellow-brown; mostly browned C2 0.1 0.5 30 95.56 ± 5.09 a Good growth; few undifferentiated; small, dense, green C3 0.1 1 30 84.44 ± 8.39 b Fair growth; some undifferentiated; small, dense, green; slight browning C4 0.1 2 30 72.22 ± 3.85 cd Good growth; partially undifferentiated; small, sparse, yellow-green; some browning C5 0.5 0.5 30 81.11 ± 5.09 bc Fair growth; some undifferentiated; small, dense, green; slight browning C6 0.5 1 30 82.22 ± 8.39 bc Fair growth; some undifferentiated; small, dense, green; slight browning C7 0.5 2 30 66.67 ± 3.34 d Good growth; partially undifferentiated; small, sparse, yellow-green; some browning C8 1.5 0.5 30 21.11 ± 5.09 e Poor growth; initial differentiation; small, sparse, yellow-green; some browning C9 1.5 1 30 10.00 ± 6.67 f Poor growth; initial differentiation; small, sparse, yellow-brown; mostly browned C10 1.5 2 30 13.33 ± 6.67 ef Poor growth; initial differentiation; small, sparse, yellow-green; some browning Values are presented as means ± standard error. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

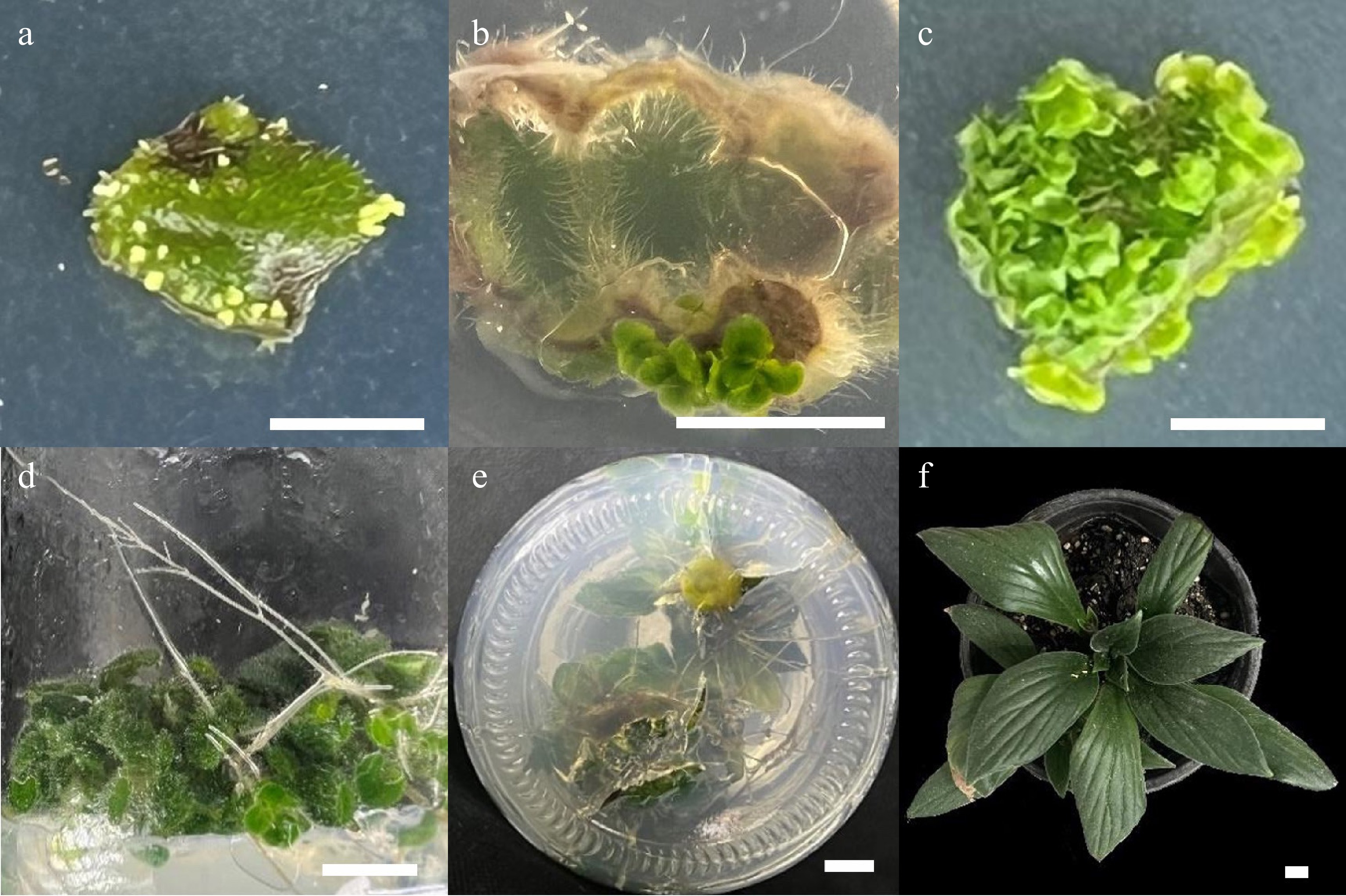

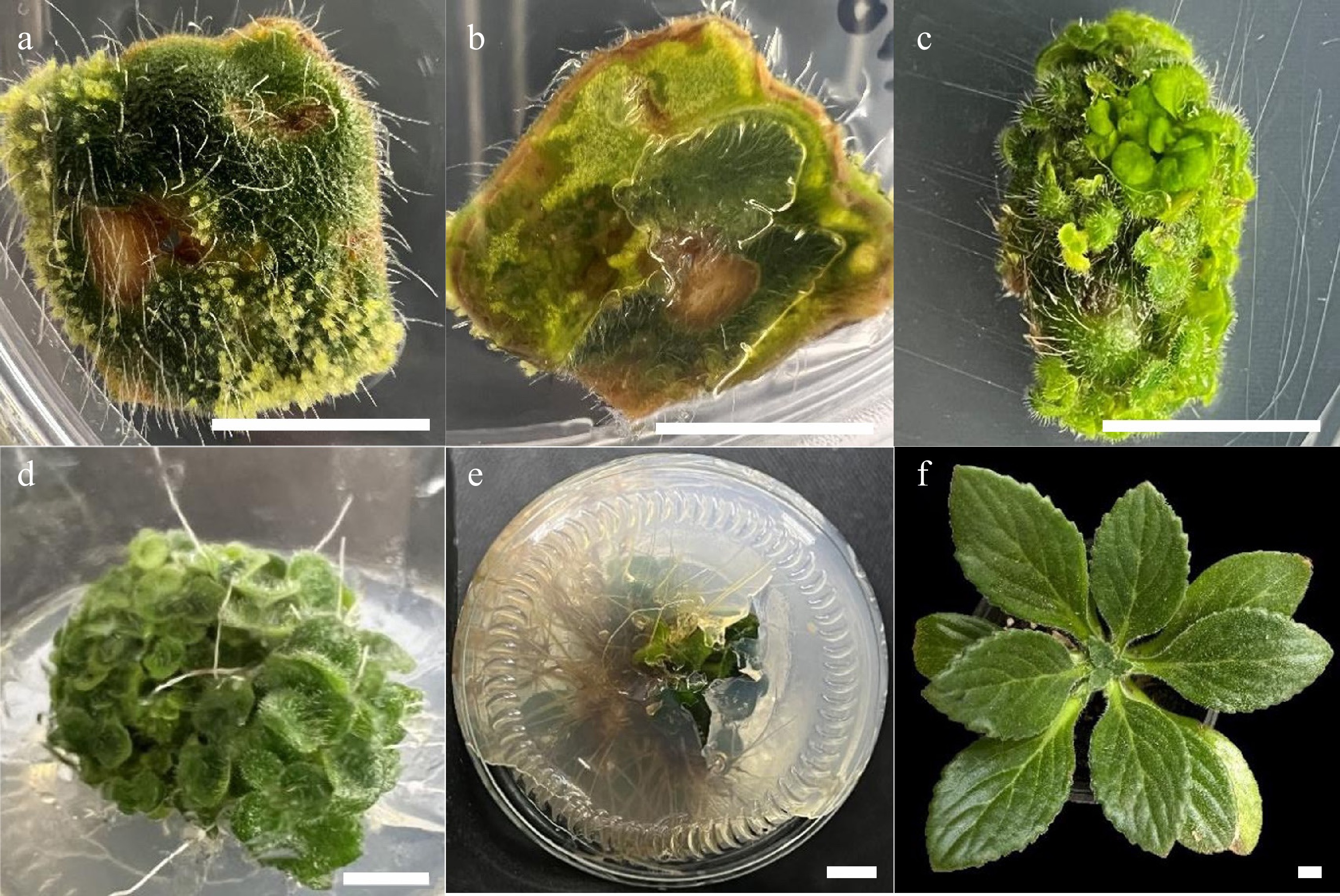

Figure 2.

Tissue culture process of Primulina 'Spring of Beilin'. (a) Adventitious buds on the front side of the leaf. (b) Adventitious buds on the back side of the leaf. (c) Proliferation of adventitious shoots. (d) Induction of root formation. (e) Condition of the root base. (f) Normal growth of the plant after transplantation. Scale bar = 1 cm.

Effect of NAA and 6-BA combinations on adventitious bud induction in Primulina 'POP Corn'

-

Similarly, significant differences were identified in the differentiation rates among the 10 treatments for adventitious bud induction in Primulina 'POP Corn' (Table 4). Analysis indicated that treatments D2, D3, and D4 achieved significantly higher differentiation rates than the remaining treatments, except for D6. Notably, the D3 treatment resulted in a 100% differentiation rate, with all leaves undergoing differentiation. Growth analysis showed that untreated explants or those subjected to high concentrations of plant growth regulators exhibited signs of browning and yellowing. In conclusion, the type and concentration of plant growth regulators added to the culture medium significantly affected both the differentiation rates and growth conditions of Primulina 'POP Corn'. Among the groups treated with 0.1 mg/L NAA, differentiation rates were notably higher, indicating that this concentration is optimal for adventitious bud induction in Primulina 'POP Corn'. Under the MS + NAA 0.1 mg/L + 6-BA 1 mg/L condition, the adventitious bud induction rate reached 100%, producing buds that were small, dense, and exhibited good growth (Fig. 3a, b).

Table 4. Effect of NAA and 6-BA combinations on adventitious bud induction in Primulina 'POP Corn'.

Treatment NAA

(mg/L)6-BA

(mg/L)Explant

number (n)Differentiation

rate (%)Growth conditions D1 0 0 30 36.67 ± 12.02 d Poor growth; initial differentiation; small, sparse buds; yellow-green; partial browning D2 0.1 0.5 30 96.67 ± 3.33 ab Good growth; few undifferentiated; small, dense buds; green D3 0.1 1 30 100.00 ± 0 a Good growth; complete differentiation; small, dense buds; green D4 0.1 2 30 96.67 ± 5.77 ab Good growth; few undifferentiated; small, dense buds; green D5 0.5 0.5 30 75.56 ± 5.09c Good growth; some undifferentiated; small, dense buds; green; slight browning D6 0.5 1 30 84.44 ± 8.39 bc Good growth; some undifferentiated; small, dense buds; green; slight browning D7 0.5 2 30 80.00 ± 12.02 c Good growth; some undifferentiated; small, dense buds; green; slight browning D8 1.5 0.5 30 53.33 ± 8.82 d Good growth; some undifferentiated; small, sparse buds; yellow-green; slight browning D9 1.5 1 30 43.33 ± 6.66 de Poor growth; mostly undifferentiated; small, sparse buds; yellow-green; slight browning D10 1.5 2 30 31.11 ± 5.09 e Poor growth; initial differentiation; small, sparse buds; yellow-green; slight browning Values are presented as means ± standard error. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). Proliferation of adventitious shoots

Effect of NAA and 6-BA combinations on the proliferation of Primulina 'Spring of Beilin'

-

Significant differences were observed in the propagation coefficients of adventitious shoots in Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' (Table 5). The propagation coefficient of treatment E2 was significantly higher than that of all other treatments, except for E1 and E3. The control treatment E1, which did not contain any plant growth regulators, showed a higher propagation coefficient compared to the treatments with plant growth regulators, except for E2. This suggests that plant growth regulators did not significantly promote the proliferation of adventitious shoots in Primulina 'Spring of Beilin'. Additionally, higher concentrations of NAA, specifically in treatments E8, E9, and E10, exhibited an inhibitory effect. In treatments E4, E7, and E10, with a 6-BA concentration of 2 mg/L, some shoots showed vitrification.

Table 5. Effect of NAA and 6-BA on proliferation and culture of Primulina 'Spring of Beilin'.

Treatment NAA

(mg/L)6-BA

(mg/L)Number of

explants (n)Propagation

coefficientGrowth conditions E1 0 0 30 11.33 ± 2.08 ab Good growth; green; few roots E2 0.1 0.5 30 14.33 ± 2.08 a Good growth; green; few roots E3 0.1 1 30 8.00 ± 3.00 abc Good growth; green; some rooting E4 0.1 2 30 5.67 ± 1.53 cd Good growth; yellow-green; some exhibited vitrification; few roots E5 0.5 0.5 30 5.67 ± 3.06 cd Good growth; green; some roots E6 0.5 1 30 5.67 ± 2.31 cd Good growth; yellow-green; some roots E7 0.5 2 30 7.33 ± 2.31 bc Good growth; yellow-green; some exhibited vitrification; few roots E8 1.5 0.5 30 5.67 ± 1.53 cd Good growth; yellow-green; some roots E9 1.5 1 30 6.33 ± 3.06 bcd Good growth; yellow-green; some exhibited vitrification; some roots E10 1.5 2 30 3.00 ± 1.00 d Poor growth; yellow-green; some exhibited vitrification; few roots Values are presented as means ± standard error. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). These results indicate that neither the concentration of NAA nor 6-BA followed a consistent trend in promoting adventitious shoot proliferation, and higher concentrations may even inhibit this process. This could be attributed to the specific characteristics of the Primulina genus or the vitrification observed during the proliferation of Primulina 'Spring of Beilin'. Statistical analysis revealed that the highest propagation coefficient, 14.33, was obtained under the lowest concentration of plant growth regulators, with healthy growth, green shoots, and no vitrification. Therefore, the MS + NAA 0.1 mg/L + 6-BA 0.5 mg/L medium was identified as the optimal medium for the proliferation of adventitious shoots in Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' (Fig. 2c).

Effect of NAA and 6-BA combinations on the proliferation and culture of Primulina 'POP Corn'

-

Significant differences were also found in the propagation coefficients of adventitious shoots in Primulina 'POP Corn' (Table 6). Among the treatments, the propagation coefficient in treatment F3 was significantly higher than in all other treatments. In the six media containing NAA at concentrations of 0.5 and 1.5 mg/L, the propagation coefficients were lower than that of the control, which did not contain plant growth regulators. In the media with NAA at 0.1 mg/L, the propagation coefficient was higher than in the control, but as the NAA concentration increased, the propagation coefficient gradually decreased. Furthermore, in the three media with NAA concentrations of 1.5 mg/L, vitrification was observed in the adventitious shoots to varying degrees.

Table 6. Effect of NAA and 6-BA on proliferation and culture of Primulina 'POP Corn'.

Treatment NAA (mg/L) 6-BA (mg/L) Number of

explants (n)Propagation

coefficientGrowth conditions F1 0 0 30 10.33 ± 1.53 bc Good growth; green; few roots F2 0.1 0.5 30 11.67 ± 1.15 b Good growth; green; few roots F3 0.1 1 30 17.33 ± 1.53 a Good growth; green; most rooted F4 0.1 2 30 10.67 ± 2.08 bc Good growth; green; few roots F5 0.5 0.5 30 7.67 ± 1.53 cd Good growth; green; some roots F6 0.5 1 30 9.33 ± 3.21 bc Good growth; green; few roots F7 0.5 2 30 6.00 ± 1.00 de Good growth; green; some roots F8 1.5 0.5 30 4.67 ± 0.58 ef Good growth; green; some exhibited vitrification; few roots F9 1.5 1 30 2.67 ± 1.53 f Poor growth; yellow-green; most exhibited vitrification; no roots F10 1.5 2 30 2.00 ± 1.00 f Poor growth; yellow-green; most exhibited vitrification; no roots Values are presented as means ± standard error. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). These findings suggest that low concentrations of NAA promote adventitious shoot proliferation in Primulina 'POP Corn', while higher concentrations inhibit shoot proliferation. Additionally, when the NAA concentration was held constant, the three treatments with 6-BA at 2 mg/L exhibited the lowest propagation coefficient, indicating that high concentrations of 6-BA may also inhibit adventitious shoot proliferation in Primulina 'POP Corn'. Statistical analysis showed that the highest propagation coefficient, 17.33, was observed in the medium with minimal plant growth regulators, which exhibited good growth, green shoots, and no vitrification. Therefore, the MS + NAA 0.1 mg/L + 6-BA 1 mg/L medium was identified as the optimal medium for adventitious shoot proliferation in Primulina 'POP Corn' (Fig. 3c).

Rooting culture and transplantation

Effect of different media combinations on rooting and transplanting of Primulina 'Spring of Beilin'

-

The rooting and transplanting results for Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' are shown in Table 7. Treatments G1, G2, G3, G5, and G6 performed well and exhibited significant differences when compared to G4 and G7. These treatments not only resulted in higher average root numbers but also achieved 100% rooting success. Analysis of the individual average root number and rooting rate revealed that the highest root number was observed in G1, which did not contain any plant growth regulators. As the concentration of plant growth regulators increased, the number of roots decreased. In treatments G4 and G7, which contained IBA and NAA concentrations of 1 mg/L, both the root number and rooting rate significantly declined, with some plants failing to root successfully.

Table 7. Effects of IBA and NAA concentration on the rooting and transplanting of adventitious buds of Primulina 'Spring of Beilin'.

Treatment IBA

(mg/L)NAA

(mg/L)Number of

explants (n)Average number

of roots per plantAverage

rooting rate (%)Transplanting

survival rate (%)Growth conditions G1 0 0 20 13.03 ± 1.99 a 100.00 ± 0 a 100.00 ± 0 a Strong roots, long; plants grow normally and healthily G2 0.1 0 20 10.67 ± 2.31 a 100.00 ± 0 a 100.00 ± 0 a Strong roots, long; plants grow normally and healthily G3 0.5 0 20 9.70 ± 2.41 a 100.00 ± 0 a 100.00 ± 0 a Strong roots, long; some plants grow slightly slower G4 1 0 20 4.07 ± 1.84 b 95.00 ± 5.00 a 63.33 ± 7.64 b Weak roots; some leaves exhibited vitrification, tissue loose G5 0 0.1 20 12.97 ± 3.33 a 100.00 ± 0 a 100.00 ± 0 a Strong roots, long; plants grow normally and healthily G6 0 0.5 20 10.20 ± 2.27 a 100.00 ± 0 a 98.33 ± 2.89 a Strong roots, long; plants grow normally and healthily G7 0 1 20 4.60 ± 1.51 b 90.00 ± 5.00 b 53.33 ± 7.64 c Weak roots; some leaves exhibited vitrification, tissue loose Values are presented as means ± standard error. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). Analysis of the transplanting survival rate and growth conditions showed that the survival rate was significantly lower in G4 and G7, with weak root systems and partial vitrification. Since no significant differences were found between treatments with no plant growth regulators and those with low concentrations of plant growth regulators in terms of survival rates, it was concluded that the best medium for rooting and healthy plant development in Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' was 1/2 MS medium without plant growth regulators (Fig. 2d−f). One year after transplantation, Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' are growing well and exhibit uniform growth (Fig. 3).

Effect of different media combinations on rooting and transplanting of Primulina 'POP Corn'

-

The rooting and transplanting results for Primulina 'POP Corn' are shown in Table 8. Treatments G1, G2, and G5 performed well, with significant differences compared to the other treatments. These treatments not only resulted in higher average root numbers but also achieved 100% rooting success. Analysis of the individual average root number and rooting rate revealed that the highest average root number (12.57 roots per plant) was observed in G2. As the concentration of plant growth regulators increased, the number of roots decreased. In treatments G4 and G7, which contained IBA and NAA concentrations of 1 mg/L, both the root number and the average rooting rate significantly declined.

Table 8. Effects of IBA and NAA concentration on the rooting and transplanting of adventitious buds of Primulina 'POP Corn'.

Treatment IBA

(mg/L)NAA

(mg/L)Number of

explants (n)Average

no. of roots

per plantAverage

rooting rate (%)Transplanting

survival rate (%)Growth conditions G1 0 0 20 11.72 ± 1.71 a 100.00 ± 0 a 100.00 ± 0 a Strong roots, long; plants grow normally and healthily G2 0.1 0 20 12.57 ± 2.65 a 100.00 ± 0 a 100.00 ± 0 a Strong roots, long; plants grow normally and healthily G3 0.5 0 20 4.83 ± 2.11 b 78.33 ± 7.64 a 81.67 ± 10.41 b Strong roots, long; some plants with leaf curling, slower growth G4 1 0 20 0.33 ± 0.25 c 21.67 ± 7.64 c 8.33 ± 7.64 c Weak roots, short; some leaves exhibited vitrification, tissue loose G5 0 0.1 20 7.43 ± 4.25 ab 83.33 ± 12.58 a 100.00 ± 0 a Strong roots, long; plants grow normally and healthily G6 0 0.5 20 3.27 ± 2.21 b 46.67 ± 27.54 b 81.67 ± 10.41 b Strong roots, long; some plants grow slightly slower G7 0 1 20 0.20 ± 0.26 c 11.67 ± 12.58 c 6.67 ± 7.64 c Weak roots, short; some leaves exhibited vitrification, tissue loose Values are presented as means ± standard error. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). Further analysis of transplanting survival rates and growth conditions showed that the survival rates of treatments G4 and G7 were significantly lower, with weak root systems and partial vitrification observed. Based on these results, the optimal medium for rooting and healthy plant development in Primulina 'POP Corn' was identified as 1/2 MS + IBA 0.1 mg/L (Fig. 4d−f). One year after transplantation, Primulina 'POP Corn' are growing well and exhibit uniform growth (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Tissue culture process of Primulina 'POP Corn'. (a) Adventitious buds on the front side of the leaf. (b) Adventitious buds on the back side of the leaf. (c) Proliferation of adventitious shoots. (d) Induction of root formation. (e) Condition of the root base. (f) Normal growth of the plant after transplantation. Scale bar = 1 cm.

-

In this study, sterile culture systems were established for two hybrid cultivars of Primulina, and the optimal media for adventitious bud induction, shoot proliferation, and rooting were identified to promote healthy plant development. Key factors influencing rapid propagation were analyzed and summarized, leading to the proposal of a preliminary protocol for the tissue culture-based mass propagation of these two Primulina hybrid cultivars, to promote future large-scale commercial production.

Selection and surface sterilization of explants

-

In general, 75% ethanol and HgCl2 are commonly used for surface sterilization of explants in Primulina species. However, HgCl2, a highly toxic heavy metal salt, is damaging to plant material, and residual HgCl2 is difficult to remove[16]. Previous studies on surface sterilization in Gesneriaceae plants, such as Sinningia speciosa, have shown that H2O2 is less effective as a disinfectant compared to NaClO and HgCl2[17]. Therefore, in this study, 75% ethanol and 2% NaClO were selected as the sterilizing agents for explants of the two hybrid Primulina cultivars. In this experiment, both sterilizing agents also achieved satisfactory results, with survival rates exceeding 85%.

Although significant progress has been made in tissue culture techniques for Primulina species over the past decades, the ethanol-HgCl2 sterilization method remains predominant in disinfection procedures. Notably, even the most recent studies on Primulina tissue culture continue to employ HgCl2 as the sterilizing agent[18]. In this study, we propose for the first time an alternative sterilization protocol using ethanol-NaClO combination. From a commercial perspective, HgCl2 poses substantial risks as a highly toxic compound, endangering both operator safety and environmental health through potential contamination. In contrast, NaClO serves as a non-toxic, environmentally friendly disinfectant with easier disposal requirements, better aligning with the safety and sustainability demands of commercial production. Consequently, our ethanol-NaClO sterilization strategy not only enhances experimental safety but also provides technical support for large-scale commercial propagation of Primulina.

In most studies on tissue culture and rapid propagation of Primulina species, leaf explants are commonly used, with fewer studies employing fruits[19], pedicels[10], stem segments[12], bracts[20], petals[8], or axillary bud-bearing flower pedicels[21]. Overall, leaves and petioles are commonly used as explants. They can rapidly induce bud formation under appropriate culture conditions and have a high regeneration efficiency[22].

However, materials that can only be collected during flowering and fruiting periods cannot support year-round tissue culture work. Additionally, preliminary experiments showed that the proliferation rate of leaf explants was higher than that of other types of explants in the two hybrid Primulina species. Furthermore, the orientation of leaf explants on the culture medium also affects the proliferation rate. Research has shown that when the adaxial surface of the leaf is placed facing upwards, both the induction frequency of adventitious buds and the number of adventitious buds per explant are significantly higher compared to when the abaxial surface is facing upwards. Therefore, in this study, we also adopted the method of placing the adaxial surface upwards[23].

Therefore, in this study, young leaves from two Primulina cultivars were selected as explants, and sterilized by soaking in 75% ethanol for 30 s, followed by disinfection with 2% NaClO solution. Significant differences in sterilization times and optimal survival rates were observed between the two hybrid Primulina cultivars. Specifically, the optimal survival rate for Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' was 95.57%, while for Primulina 'POP Corn', it was 88.89%. Moreover, the optimal NaClO treatment time for Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' was shorter than that for Primulina 'POP Corn', suggesting that Primulina 'POP Corn' exhibited greater tolerance to NaClO than Primulina 'Spring of Beilin'. This difference may be attributed to variations in the texture, thickness, and trichome density of the leaf explants; Primulina 'POP Corn' leaves are slightly thicker and more densely covered with trichomes compared to Primulina 'Spring of Beilin'.

Adventitious bud differentiation and proliferation

-

For the formation and proliferation of adventitious buds, it is generally believed that meristematic tissue originates from epidermal cells near the incision, adjacent to the vascular bundles. Through cell division and differentiation, a cluster of meristematic cells is formed, which subsequently gives rise to adventitious buds. In this process, plant growth regulators play a crucial role[24]. In the tissue culture of Gesneriaceae plants, the most common combination of plant growth regulators is NAA and 6-BA. In the tissue culture of Haberlea rhodopensis, it has been found that a combination of 0.2 mg/L 6-BA and 1.0–2.0 mg/L NAA is most effective in inducing bud differentiation[25]. In the tissue culture of Saintpaulia ionantha, it has been found that the supplementation of MS medium with 2.0 mg/L NAA and 1.0 mg/L 6-BA results in the highest number of sterile or vegetative flower buds regenerated from the surface of callus tissue derived from explants[26]. Study on the tissue culture of Chiritopsis repanda var. guilinensis identified the optimal plant growth regulator combination for adventitious bud induction as NAA and 6-BA[27], suggesting that NAA and 6-BA may play a decisive role in the differentiation of adventitious buds in the Primulina hybrid cultivars. For proliferation culture, a lower ratio of auxin to cytokinin generally favors the formation of shoots[27]. However, when the concentrations of plant growth regulators, such as NAA and 6-BA, exceed a certain threshold, adventitious bud formation is inhibited, and the propagation coefficient decreases. Therefore, the appropriate ratio of cytokinin to auxin is critical for the successful proliferation of adventitious buds.

In this study, the effects of different combinations of NAA and 6-BA on adventitious bud differentiation and proliferation were investigated. During the adventitious bud induction stage, it was observed that explants of the two Primulina hybrid cultivars exhibited high induction rates and good growth when cultured on MS + NAA 0.1 mg/L + 6-BA 0.5 mg/L, and MS + NAA 0.1 mg/L + 6-BA 1 mg/L media. The resulting buds were small, dense, and healthy, indicating that these two media were optimal for adventitious bud induction. Both media contained low auxin concentrations and yielded the best results. The experiment also demonstrated that higher concentrations of plant growth regulator combinations significantly decreased the differentiation capacity of adventitious buds. During the shoot proliferation stage, explants of the two Primulina hybrid cultivars exhibited the best growth on MS + NAA 0.1 mg/L + 6-BA 1 mg/L, and MS + NAA 0.1 mg/L + 6-BA 0.5 mg/L media, with green shoots and some rooting observed. However, as the auxin concentration increased, adventitious shoot growth deteriorated, with yellowing and vitrification observed in some cases. These results suggest that the two Primulina cultivars responded differently to the NAA and 6-BA combinations, and even closely related hybrids within the same genus may exhibit variations in tissue culture and rapid propagation at different stages. In the tissue culture of Dayaoshania cotinifolia, it has been found that an appropriate concentration of 6-BA can effectively induce the formation of adventitious buds, while a higher concentration leads to the vitrification phenomenon of the buds[28]. Research on Saintpaulia ionantha has revealed its remarkable sensitivity to cytokinins, particularly 6-BA, where concentrations exceeding 1.0 mg/L coupled with an imbalanced NAA ratio in the culture medium significantly elevate vitrification rates[29]. A positive correlation was observed between vitrification percentage and cytokinin concentrations, with 6-BA demonstrating more pronounced effects than ZT or KT. The underlying mechanisms may involve either: disruption of the equilibrium between cell division and differentiation by elevated cytokinin levels, resulting in disorganized proliferation of parenchyma cell clusters; or endogenous hormonal alterations, particularly ethylene overproduction, which triggers chlorophyll degradation, cellular deformation, and subsequent accumulation of fibrous and vesicular materials within cells, ultimately leading to vitrification phenomena[30]. Therefore, vitrification was observed in the high auxin concentration group during the proliferation stage of Primulina 'POP Corn', likely due to the excessively high concentration of 6-BA.

In this study, the propagation coefficient was calculated based on buds exceeding 0.3 cm in size per cluster, which were sufficiently developed to grow independently after isolation under sterile conditions. This methodological criterion may result in slightly lower propagation coefficients compared to those reported in previous studies.

Rooting culture and transplantation

-

The two hybrid Primulina cultivars used in this experiment showed signs of root formation or partial rooting even during the shoot proliferation stage. In previously reported rooting protocols for Primulina species, 1/2 MS medium is commonly used as the basic medium for root induction, with either minimal or no addition of plant growth regulators.

In the tissue culture of Lysionotus pauciflorus, adventitious buds regenerated easily on 1/2 MS medium without any plant growth regulators, indicating that this medium is suitable for the rooting of regenerated plantlets[31]. In the tissue culture of Chirita moonii, 1/2 MS medium was found to be more suitable for adventitious bud rooting induction than full-strength MS medium. This may be related to the lower concentration of nutrients in the 1/2 MS medium, which facilitates the action of rooting hormones[32].

For Primulina yungfuensis, a rooting culture without plant growth regulators resulted in the formation of both new adventitious buds and rooted plants[33]. In studies on the in vitro culture of Sinningia speciosa leaves found that a combination of 6-BA and NAA promoted adventitious bud induction and proliferation, while IBA or NAA facilitated root development[34]. In the study of Metabriggsia ovalifolia, it was found that the addition of small amounts of IBA, NAA, or IAA in 1/2 MS medium could induce the formation of adventitious roots within 2 weeks, with no significant differences in rooting effects, indicating that these three auxins have similar effects on adventitious root induction[35]. In this experiment, similar results were observed, with IBA and NAA showing little difference in their effects on root induction for the two experimental materials.

For Primulina 'Spring of Beilin', the optimal rooting medium was the basal medium without any plant growth regulators. Although the optimal rooting medium for Primulina 'POP Corn' was 1/2 MS + IBA 0.1 mg/L, which contained a small amount of IBA, there was no significant difference in rooting compared to the control group without any plant growth regulators. Therefore, it is speculated that during the rooting phase, the two hybrid Primulina cultivars in this experiment did not require plant growth regulators. Both cultivars exhibited robust root systems with long roots, and the transplant survival rates reached 100%, with the plants growing normally after transplantation. This may be attributed to the high concentration of plant growth regulators used in previous cultures, or it could be due to the intrinsic characteristics of the plants.

Significance and value

-

Compared to the parental species Chirita fimbrisepala (now Primulina fimbrisepala) of Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' and Chirita pungentisepala (now Primulina pungentisepala) of Primulina 'POP Corn'[9], the tissue culture protocol established in this study is simpler. In the adventitious bud proliferation process of the parental species, explants need to differentiate into callus tissue before forming adventitious buds. In contrast, the two hybrid Primulina cultivars in this study did not exhibit significant callus formation and were able to directly form adventitious buds at the wound site[36]. This direct bud formation is more efficient than the indirect regeneration of adventitious buds through callus tissue. The two parental species required 22 weeks from surface sterilization to rooted plantlet transplantation[9], whereas the two hybrid cultivars in this study achieved successful rooting within 12 weeks and could be transferred to soil conditions between 12–16 weeks.

In the tissue culture of different varieties of Sinningia speciosa, significant differences were observed in the induction frequency of adventitious buds and the number of adventitious buds per explant between the two varieties. This indicates that there are differences in the adventitious bud induction capacity among different varieties in tissue culture, and the genetic background of the varieties has an important impact on adventitious bud induction[23]. Both hybrid Primulina cultivars in this experiment achieved differentiation rates exceeding 95%, with some groups reaching 100%, much higher than the differentiation rates observed in the two wild species. In contrast, the highest adventitious bud differentiation rates observed in the two parental species were only 80% and 82.22%[9], respectively, demonstrating significantly lower efficiency compared to the hybrids.

The experimental results demonstrated that the maximum propagation coefficient of the two hybrid Primulina cultivars reached 14–16, indicating that a single leaf explant could differentiate into 14–16 transplantable plantlets. In contrast, traditional leaf-cutting propagation yielded a propagation coefficient of only 1–2 and required the use of outer leaves from healthy mature plants. These findings confirm that tissue culture exhibits significantly higher propagation efficiency than conventional leaf-cutting methods. From a commercial production perspective, although leaf-cutting propagation is technically simpler, production must be demand-driven, and reducing the production cycle is critical for improving profitability. Tissue-cultured plantlets demonstrated notable advantages during transplantation: (1) higher survival rates, (2) faster scalability to meet large-volume demands, and (3) superior plant quality and uniformity. Therefore, the application of tissue culture technology in the commercial production of hybrid Primulina cultivars shows considerable potential for development.

This suggests that, despite some phylogenetic similarities within the Primulina genus, significant differences exist in both the propagation methods and propagation efficiency. These differences underscore the importance of developing tissue culture protocols for different cultivars, especially for newly hybridized cultivars. In the tissue culture of Saintpaulia spp., it was found that a high proportion of blue flower mutants and other solid color variants were observed among the progeny produced through tissue culture. These variants were not observed in leaf-cutting propagation. The solid color phenotypes were stably inherited in the progeny, indicating that tissue culture can induce somatic variation[37]. Although this phenomenon has not been observed in this study, a large number of transplanted seedlings are pending further observation, which also represents a new research direction. In addition, the establishment of tissue culture systems is also of great significance for the conservation of endangered plants. Studies have demonstrated the application of tissue culture techniques in the conservation of the endangered plant Oreocharis mileense[38]. The experimental materials used in this study, as artificially bred cultivars, have implications for the protection of many wild species of the genus Saintpaulia. The establishment of tissue culture systems for artificially bred cultivars also has significant application value in large-scale propagation of superior cultivars, germplasm resource preservation, and pathogen elimination[39].

-

In this study, an efficient tissue culture system for Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' was established. The optimal protocol involved sterilizing explants with 75% ethanol for 30 s, followed by disinfection in a 2% NaClO solution for 3 min. The most effective media for adventitious bud induction and shoot proliferation were MS + NAA 0.1 mg/L + 6-BA 0.5 mg/L.

For Primulina 'POP Corn', the optimal tissue culture system involved sterilizing explants with 75% ethanol for 30 s and treating them with 2% NaClO solution for 6 min. The best media for both adventitious bud induction and shoot proliferation were MS + NAA 0.1 mg/L + 6-BA 1 mg/L.

Both hybrid Primulina cultivars rooted without specific induction, with rooting occurring during the shoot proliferation stage. When a change in medium was implemented for rooting induction, the optimal protocols were 1/2 MS without plant growth regulators for Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' and 1/2 MS + IBA 1 mg/L for Primulina 'POP Corn', both resulting in 100% rooting success. One year after transplantation, the uniform group of transplanted seedlings exhibited vigorous growth and stable plant morphology. It is provisionally concluded that the establishment of a tissue culture system for hybrid Primulina may promote and improve the commercialization of Primulina. The experimental results demonstrated that although both hybrid Primulina cultivars could successfully regenerate aseptic plantlets using similar culture protocols, they exhibited significantly different responses to plant growth regulators in terms of type specificity, concentration dependence, and combination ratios. This underscores the necessity of developing individualized culture systems for distinct hybrid cultivars.

Future research should focus on improving early-stage proliferation efficiency, shortening the overall cultivation cycle, and enhancing the application of this protocol in commercial production. Additionally, establishing a genetic transformation system would contribute significantly to the breeding programs of Primulina species. Figure 6 depicts a brief description of the entire experimental process.

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (QNTD202306); National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFF1301704); The Special Research Funds for the Central Universities (2015ZCQ-YL-03); Horizontal project commissioned by enterprises and institutions for scientific and technological projects (2020HXFWYL20).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Liu Y, Hu X, Luo L, Zhang Y, Zhang Q; data collection: Liu Y, Hu X; analysis and interpretation of results: Liu Y, Hu X, Shen Z, Wu H, Sun C; draft manuscript preparation: Liu Y, Hu X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu Y, Hu X, Shen Z, Wu H, Sun C, et al. 2025. Breeding and rapid propagation of Primulina: a pioneering example of Chinese floral innovation and commercialization. Ornamental Plant Research 5: e023 doi: 10.48130/opr-0025-0021

Breeding and rapid propagation of Primulina: a pioneering example of Chinese floral innovation and commercialization

- Received: 24 January 2025

- Revised: 31 March 2025

- Accepted: 08 April 2025

- Published online: 04 June 2025

Abstract: Tissue culture technology, as an efficient method for plant propagation, holds significant importance for the development and promotion of new cultivars. In this study, we established an efficient tissue culture system for two newly bred hybrid Primulina cultivars: Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' and Primulina 'POP Corn', using leaf explants. The system included explant sterilization, adventitious bud differentiation, shoot proliferation, rooting, and transplantation. The results demonstrated that the optimal tissue culture system for Primulina 'Spring of Beilin' was as follows: explants were sterilized with 75% ethanol followed by disinfection in 2% NaClO solution for 3 min, achieving a survival rate of 95.57%. The optimal induction medium for adventitious bud differentiation and shoot proliferation was MS + NAA 0.1 mg/L + 6-BA 0.5 mg/L, resulting in an induction rate of 95.59% and a propagation coefficient of 14.33. The best rooting medium was 1/2 MS without plant growth regulators, with a transplant survival rate of 100%. For Primulina 'POP Corn', explants were sterilized with 75% ethanol and disinfected in 2% NaClO solution for 6 min, resulting in a survival rate of 88.89%. The optimal induction medium for adventitious bud differentiation and shoot proliferation was MS + NAA 0.1 mg/L + 6-BA 1 mg/L, achieving a 100% induction rate and a propagation coefficient of 17.33. The optimal rooting medium was 1/2 MS + IBA 1 mg/L, with a transplant survival rate of 100%. This study established efficient tissue culture systems for two hybrid Primulina cultivars, directly inducing adventitious buds without callus formation, and shortening propagation cycles. Using ethanol and NaClO for sterilization showed simplicity and non-toxicity for large-scale production, supporting large-scale propagation, and commercialization of Primulina cultivars.

-

Key words:

- Primulina /

- Rapid propagation /

- Tissue culture /

- Commercialization