-

With the advancement of socioeconomic development and heightened ecological awareness, bulbous flowers have gained increasing prominence in landscape and private gardens, becoming an integral part of modern horticulture and landscape design. Among these, Hippeastrum spp. stand out for their large, vibrant blooms, elegant stature, and auspicious symbolism of being 'destined for fame', earning widespread popularity. Hippeastrum spp. (this paper refers to it as Hippeastrum), the collective term for all species in the Hippeastrum genus of the Amaryllidaceae family, are commonly referred to as 'Amaryllis' in English[1]. This genus comprises nearly 90 species, native to Central and South America, whereas the true Amaryllis spp. originates from Africa. Over the past two centuries, more than 1,000 Hippeastrum cultivars have been developed worldwide, with most commercially available cultivars originating from Europe[2−4]. Large-scale Hippeastrum cultivation is primarily concentrated in the Netherlands, South Africa, Brazil, and the United States. In recent years, driven by the growing demand in China, Japan, and South Korea, the industrial cultivation of Hippeastrum has also established a significant presence in Asia.

Hippeastrum presents vast market potential with a wide range of application formats. It is used not only in potted plants, cut flowers, landscaping, and garden decoration but also in festive markets during Christmas, New Year, and the Lunar New Year, where it is especially favored in the form of potted plants and waxed bulbs. With the rapid development of modern protected agriculture, Hippeastrum has emerged as a representative high-value commercial crop. According to statistics, its yield in China can reach approximately 10,000 RMB per mu, highlighting its substantial economic value, driving the transition of agriculture from traditional cultivation to a more technology-driven and intensive production system. Moreover, due to its ease of cultivation and high flowering rate, Hippeastrum has become a burgeoning economic driver in home gardening. Notably, its medicinal potential is also gaining increasing attention, particularly the alkaloids found in its bulbs, such as galantamine, which plays a crucial role in treating Alzheimer's disease[5,6]. However, despite the growing global demand for Hippeastrum, high bulb prices remain a barrier to its broader adoption.

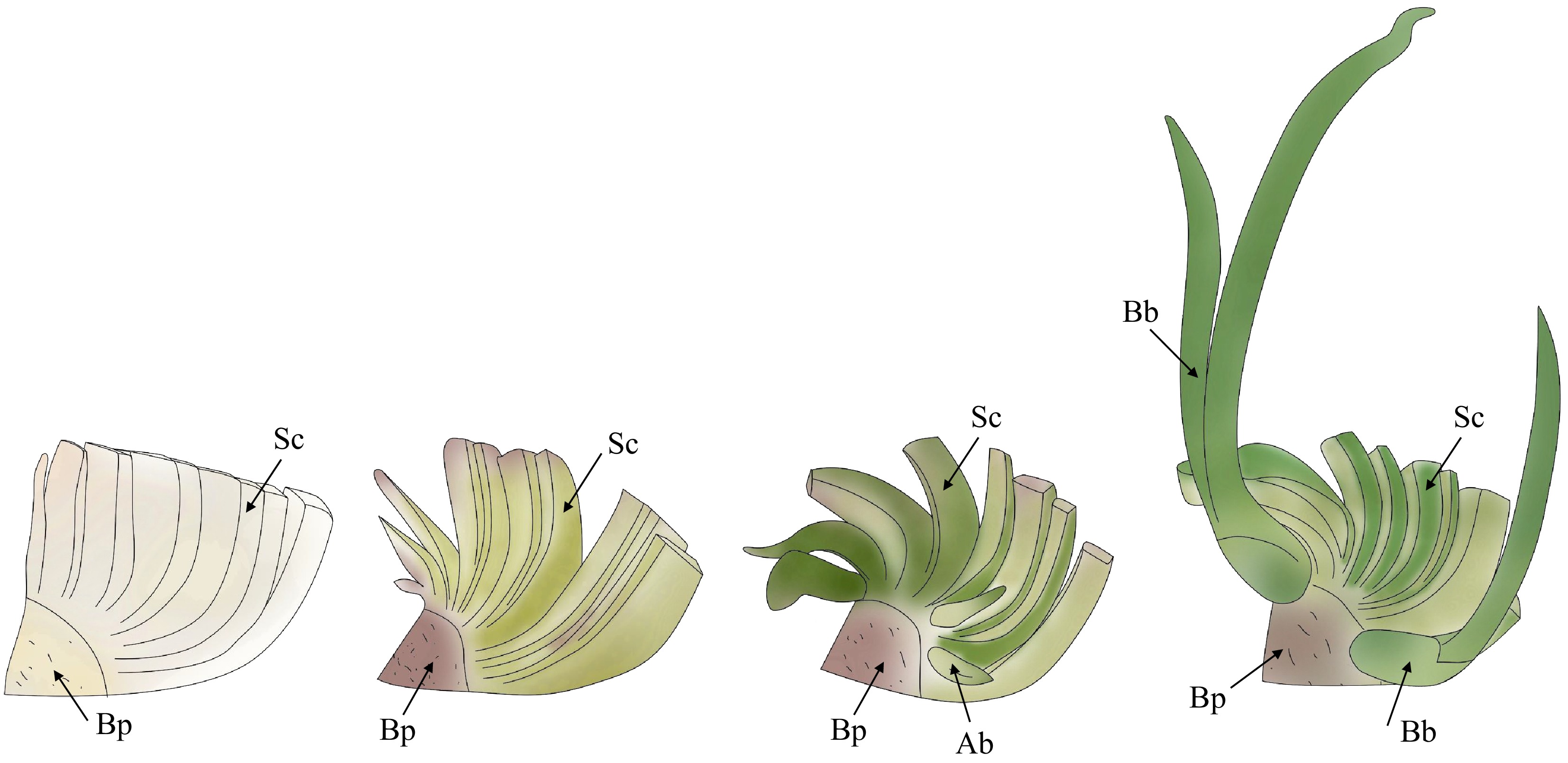

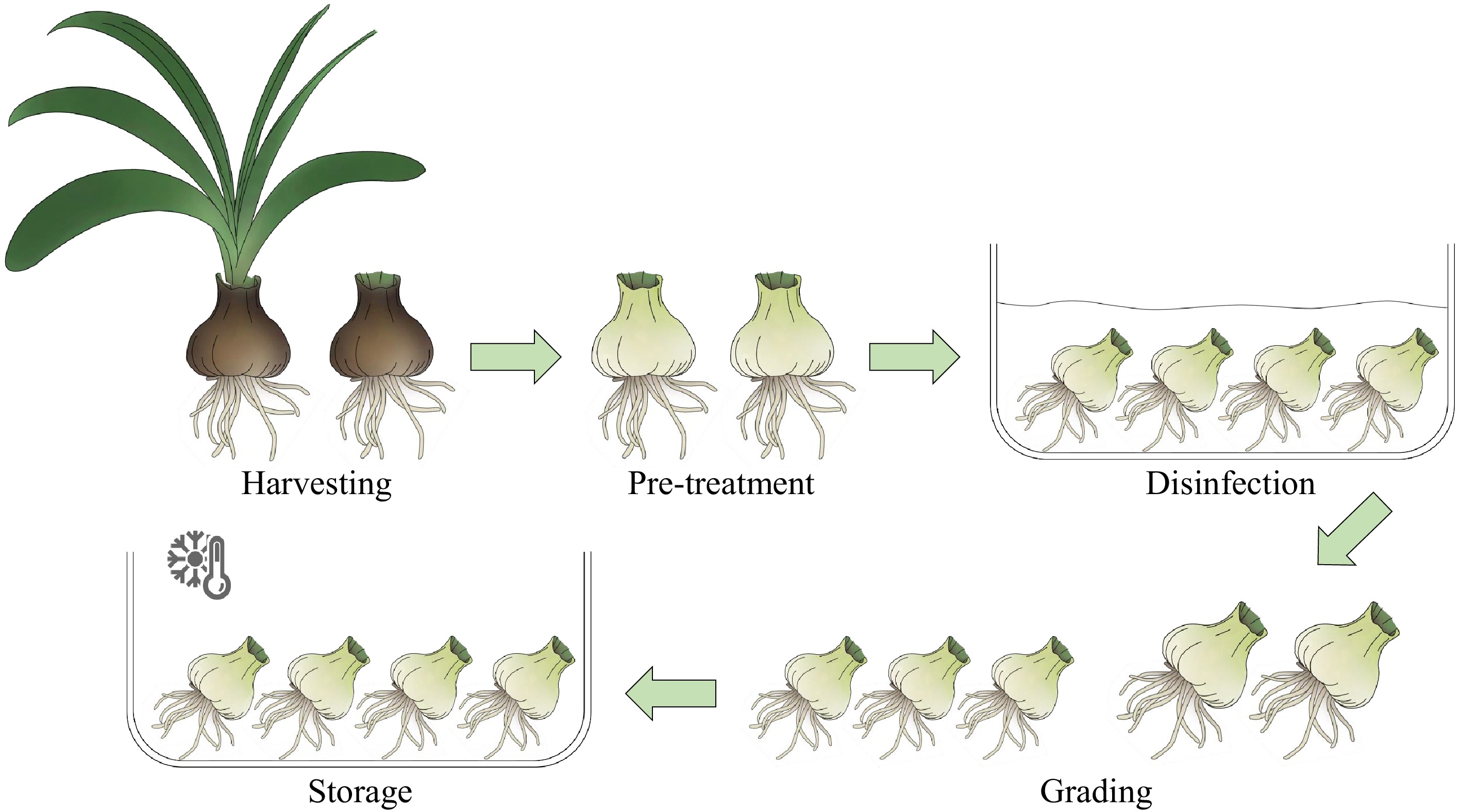

As a bulbous plant, the size of the bulb is a critical determinant of Hippeastrum's growth, flowering, and bulb quality[7]. Larger bulbs typically have more substantial reserves, significantly enhancing reproductive efficiency[8]. Hippeastrum can be propagated through seeds, tissue culture, bulb division, and bulb scale cuttings. Due to self-incompatibility in some cultivars and trait segregation in seed-propagated progeny, seed propagation is mainly utilized for breeding new cultivars. Given the high costs associated with tissue culture and the limited bulb division from mother bulbs, bulb scale cutting has emerged as the most commonly used propagation method in commercial production (Fig. 1). However, these small bulbs often require two to three years to reach flowering and enter the commercialization stage. During this period, slow bulb enlargement, poor development, and limited flowering pose significant challenges, alongside the lack of systematic techniques for regulating bulb development. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms regulating bulb development and enlargement, as well as optimizing postharvest treatments, is crucial for enhancing Hippeastrum's ornamental and medicinal potential and key to advancing its industrial-scale production.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of bulblet formation through scale cutting in Hippeastrum. Sc: scales; Bp: basal plate; Ab: axillary bud; Bb: bulblet.

Despite the rapid development of Hippeastrum's industrialization, comprehensive reviews focusing on its bulb development and postharvest treatments remain scarce. This review examines Hippeastrum bulb morphology, factors influencing bulb growth, and postharvest treatments. It aims to summarize existing cultivation and regulatory measures, providing theoretical insights into the developmental regulation and postharvest management of Hippeastrum bulbs. Additionally, the review seeks to offer strategies for reducing production costs and improving propagation efficiency through techniques such as plant growth regulators, thereby promoting the further industrialization of Hippeastrum.

-

The bulb is a plant's nutritional organ, formed by the enlargement of the leaf sheath base that arises from a disc-shaped shortened stem. Mapson et al.[9] defined it as a short, typically round underground stem enveloped by fleshy, vertical scales serving a storage function. The upper part of the bulb is tightly encased by fleshy leaf sheaths, with the true stem located at the bulb's base in the form of a shortened disc or flattened cone, referred to as the basal plate. The basal plate is surrounded by cylindrical, thick, fleshy scales that are white or yellowish-white in color. Bulbs can be categorized into two types based on the structure and arrangement of their scales: tunicated bulbs and scaly bulbs[10]. Tunicated bulbs feature scales arranged in a layered structure, tightly wrapped around each other, with a dry, membranous outer covering, as seen in onion (Allium cepa) and Lycoris bulbs. In contrast, scaly bulbs, also known as imbricated bulbs, have loosely arranged fleshy scales without an outer covering, such as Lilium spp. bulbs. Additionally, bulbs can be classified into onion-type and garlic-type based on the manner of scale enlargement, a system originally developed for edible bulbs[11]. In onion-type bulbs, the scales are formed from two parts: the leaf sheath base with a leaf blade and enlarged leaf sheaths with degenerated leaf blades, with the scales arranged in layers. In garlic-type bulbs, however, the scales develop from the enlargement of lateral buds that have not yet fully differentiated rather than from the enlargement of the leaf sheath base with a leaf blade.

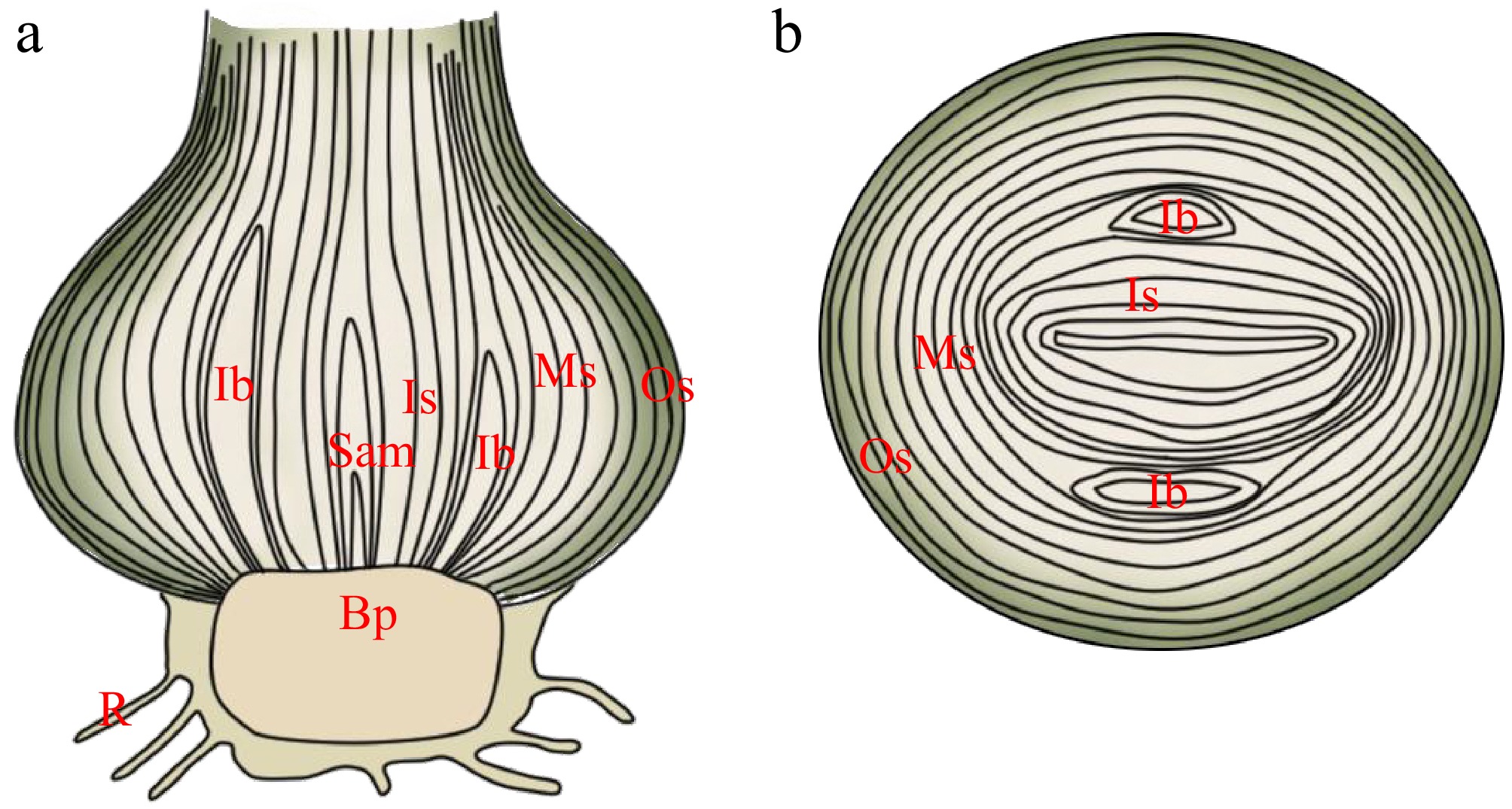

Bulb structures are likely intricately linked to both bulb development and propagation. Hippeastrum bulbs are classified as tunicated bulbs, with an enlarged oval shape composed of tightly arranged fleshy scales and a basal plate. The bulb is enclosed by a reddish-brown protective bulb skin (Fig. 2), resembling the form of an onion[12]. Compared to scaly bulbs, tunicated bulbs typically possess a well-developed outer layer that provides physical protection, retains moisture, and acts as a barrier against pathogens. The arrangement of the scales in Hippeastrum follows a specific pattern, with three cylindrical scales and one flattened scale forming a scale group[13]. This unique structure may assist in the functional differentiation of the bulb. For instance, flower bud differentiation and distribution in Hippeastrum are closely related to bulb development. Mature bulbs exhibit sympodial branching, with each growth unit comprising four leaves and one terminal inflorescence[14].

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of Hippeastrum bulb structure. (a) Longitudinal section of Hippeastrum bulb. (b) Cross-section of Hippeastrum bulb. Based on the classification of Lycoris bulb scales into three layers[15], Hippeastrum bulb scales are similarly divided into outer scales (Os), middle scales (Ms), inner scales (Is), and the basal plate (Bp). Sam: shoot apical meristem; Ib: inflorescence bud; R: root.

Bulbs serve as the primary nutrient storage organ for Hippeastrum, playing a crucial role in accumulating and storing nutrients. This not only protects the flower and leaf buds but also provides essential support for the plant's growth and development. Moreover, bulbs are vital to the reproduction of Hippeastrum. The apex of the basal plate acts as the growth point, and when the top growth point is damaged, it stimulates the sprouting of lateral buds and the formation of adventitious buds, ultimately leading to the formation of bulblets[13]. During scale-cutting propagation, bulblets typically form at the base of the scales, where the scales connect with the basal plate (Fig. 1). In this process, the scales play a key role, providing the necessary nutrients and material support for the sprouting of adventitious buds and the formation of bulblets[12]. The outer membrane coloration of Hippeastrum bulbs may be associated with flower color, although the specific correlation remains unclear; further investigation in this area may provide a useful reference for the identification of Hippeastrum germplasm resources[16]. In conclusion, the regulation of Hippeastrum bulb development is a critical issue that deserves further study.

-

The development of Hippeastrum bulbs directly determines flowering quality and reproductive efficiency, profoundly impacting their economic value. As the primary nutrient storage organ, bulb scales undergo dynamic changes throughout the growth cycle. During the early stages, nutrient consumption leads to bulb shrinkage, while later, the accumulation of photosynthetic products during vigorous leaf growth promotes the formation of new scales and bulb enlargement. In onion, bulb development is divided into three stages: initial enlargement, rapid enlargement, and enlargement cessation, with the enlargement phase lasting approximately one to two months[17,18]. In tulips (Tulipa gesneriana), bulbs expand rapidly during the early stages of bulb development; however, as development progresses, their rate of expansion gradually decelerates[19]. Bulb development may follow a stage-specific growth pattern. In onions, vertical growth predominates during the vegetative stage, whereas lateral growth accelerates significantly during bulb enlargement[20]. However, a systematic classification of the developmental stages in Hippeastrum bulbs has yet to be established. This section provides a comprehensive review of the exogenous factors (light, temperature, water, nutrients, and hormones) and endogenous factors (hormones and carbohydrates) that influence Hippeastrum bulb development, aiming to provide insights for advancing research in this area.

Long photoperiods and red-blue light promote Hippeastrum bulb growth

-

Light is one of the most critical environmental factors regulating plant growth and development, influencing numerous physiological processes. Its role in Hippeastrum bulb development is equally pivotal. Research has shown that light promotes the accumulation of organic matter in Hippeastrum bulbs[21]. Small bulbs grown in continuous darkness exhibit significantly lower dry weight and leaf area compared to those grown under light or alternating light-dark conditions[21], highlighting the essential role of light for bulb growth and enlargement. Furthermore, plants exposed to abundant light exhibit higher starch content in their bulbs compared to those grown in shaded conditions, potentially due to enhanced photosynthesis and increased carbon assimilation[22]. For one-year-old bulbs, sufficient light is particularly beneficial for dry matter accumulation.

The photoperiod plays a crucial role in bulb development. Long photoperiods, by extending the duration of photosynthesis, facilitate nutrient synthesis and accumulation, thereby supporting bulb formation and growth[13]. In contrast, short photoperiods may constrain these processes, impeding bulb development[13]. In vitro experiments on Hippeastrum showed that a 16/8 h light/dark photoperiod was optimal for bulblets growth[23]. Similarly, in onions and Narcissus, long photoperiods (≥ 14 h) are essential for bulb initiation, with extended day lengths accelerating bulb development, further demonstrating the positive effect of long photoperiods on bulb development[24,25]. Furthermore, long photoperiods elevate endogenous GA levels in various plants, suggesting that photoperiods may influence bulb development by regulating hormone homeostasis[26]. Thus, optimizing photoperiods is critical for the reproduction and development of Hippeastrum bulbs.

Light quality also significantly impacts bulb development. Studies have shown that specific red-to-blue light ratios can influence biomass accumulation in Hippeastrum bulbs. For instance, a red : blue ratio of 9:1 significantly increased soluble sugar accumulation during the vegetative stage of Hippeastrum hybridum 'Red Lion' bulbs but may delay flowering[27]. In contrast, a red : blue ratio of 1:3 promoted Hippeastrum 'Ferrari' seedling growth and biomass accumulation, improving fresh weight, dry weight, root length, root count, and bulb diameter[28]. Further research revealed that pure red light inhibits chlorophyll synthesis in seedlings, whereas the addition of blue light promotes it. A red : blue ratio of 1:3 facilitated photosynthetic pigment synthesis in leaves by upregulating genes involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis and reduced lipid peroxidation[28]. As a result, a red : blue ratio of 1:3 is considered ideal for promoting Hippeastrum 'Ferrari' seedling growth. While the roles of photoperiod and light quality in Hippeastrum bulb development have been explored to some extent, further studies are needed to validate and optimize light conditions tailored to specific cultivars. It is worth noting that the effect of light environment regulation depends on its synergy with temperature conditions, as the efficiency of light-driven photosynthetic product accumulation is highly contingent upon an optimal environment.

The complex effect of temperature on Hippeastrum bulb development

-

Temperature is another critical factor regulating Hippeastrum bulb development[29]. Studies across various Hippeastrum cultivars suggest that the optimal temperature for bulb growth is around 25 °C[30−33]. Bulbs grown at 25 °C exhibit significantly higher fresh weight, dry weight, diameter, and flowering quality compared to those cultivated at 30 °C[32]. In contrast, bulbs grown at 15 °C show markedly reduced circumference and leaf count compared to those grown at 25 °C[34]. However, Ijiro et al.[31] noted that a temperature of 30 °C enhances the enlargement rate during the late developmental stages of Hippeastrum bulbs. Similar trends are observed in onions, where warm temperatures (21–27 °C) are crucial for bulb growth, particularly during the late enlargement phase[23,35]. Additionally, Ephrath et al.[34] found that increasing the nighttime temperature, regardless of whether the daytime temperature was 22 or 27 °C, promoted an increase in bulb fresh weight. This suggests that a lower diurnal temperature variation may enhance the development of Hippeastrum bulbs.

Root-zone temperature also significantly influences bulb development. Studies indicate that root-zone temperature affects photosynthesis, assimilate allocation, mineral nutrition, and water uptake[36−38]. In a temperature gradient from 15 to 25 °C, Hippeastrum bulbs showed increasing circumference and leaf count with rising temperatures, with the longest circumference observed at 25 °C[33]. However, when soil temperatures drop below 15 °C, bulb growth halts[31]. Interestingly, for Hippeastrum 'Apple Blossom', reducing root-zone temperature has been shown to promote fresh weight, dry weight, and circumference[39].

Overall, temperature has a complex effect on Hippeastrum bulb development. Optimal cultivation temperatures vary depending on factors such as cultivar, bulb size, developmental stage, diurnal temperature fluctuations, and storage conditions. Adjusting both environmental and soil temperatures during cultivation may shorten the growth period and enhance flowering quality.

Flexible water and fertilizer management enhances Hippeastrum bulb growth

-

Water, along with macronutrients such as nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), and calcium, is essential for plant growth and development. Scientific water and fertilizer management can significantly enhance plant quality and yield[7]. Water deficiency inhibits Hippeastrum growth, primarily due to reduced stomatal conductance and impaired carbon assimilation[40,41]. Efficient water absorption is closely tied to nutrient availability; adequate nutrients promote root growth, increase water uptake, and enhance transpiration efficiency, ultimately driving plant growth and improving yield[42,43]. Improving soil nutrient levels boosts chlorophyll synthesis and photosynthesis, expands leaf area, and accelerates transpiration, thereby reducing evaporation and supporting plant development. This is particularly crucial for the quality and flowering of bulbous plants.

Appropriate fertilization accelerates Hippeastrum bulb growth, significantly increasing bulb fresh weight, circumference, and firmness and promoting bulb division[7,8]. Studies indicate that small Hippeastrum bulbs exhibit lower P requirements, likely due to the relatively modest nutrient demand during early development[31]. Tombolato et al.[44] emphasized the importance of adjusting fertilization based on the growth stage, avoiding excessive nutrient supply during early vegetative growth. Similar findings have been reported in research on onions and Lilium. In onions, applying twice the amount of N during the later growth phase compared to the early phase ensures sufficient N availability throughout both vegetative and reproductive growth phases[45−47].

Synergistic interactions between nutrients play a vital role in improving their synthesis, transport, and storage. For instance, calcium enhances the fresh weight of Hippeastrum bulbs and influences the content of N, K, and non-structural carbohydrates[48]. Fertilizer efficacy depends largely on the ratio and concentration of N, P, and K, with compound fertilizers generally outperforming single-nutrient fertilizers[49]. Jamil et al.[50] reported that applying N, P, and K at a ratio of 200:400:300 kg/ha effectively enhanced the ornamental traits of Hippeastrum. Similarly, El-Ghait et al.[51] found that a 6:6:6 g/L N, P, and K ratio boosted bulb fresh and dry weight. Ding et al.[52] observed that a fertilizer containing 20% N, P, and K was more effective than one with 15% N, P, and K in promoting seedling leaf, root, and bulb growth. This difference may be attributed to variations in nutrient concentrations[53]. Furthermore, Lv et al.[54] discovered that different Hippeastrum cultivars have distinct fertilization cycle requirements. Thus, water and nutrients play a pivotal role in Hippeastrum bulb development. Fertilization and irrigation strategies should be tailored to specific cultivars and growth stages, employing a 'small and frequent' approach to enhance bulb quality.

Hormonal regulation of Hippeastrum bulb development

-

Plant hormones play a critical role in regulating Hippeastrum bulb development, with numerous studies highlighting the significant growth-promoting effects of exogenous hormones. For example, spraying 100 mg/L indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) twice at 30 d intervals significantly increased bulb weight, whereas the same concentration of naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) showed no comparable effect, and prolonged application inhibited bulb growth[55,56]. However, tissue culture experiments have revealed that NAA can significantly promote the growth of small bulbs and roots, suggesting that its efficacy may depend on the application method[24,57,58]. The stimulatory effects of gibberellin (GA) on Hippeastrum bulb development are particularly notable. Spraying 100 mg/L GA six times at 10 d intervals significantly enhanced bulb growth and increased chlorophyll content, with even higher concentrations (1,000 mg/L) proving more effective[59]. The promotive effect of GA on bulb development is consistent with findings from studies on the bulb development of onions[59]. However, in Lycoris and Lilium, GA was found to inhibit bulb development[60,61], indicating that the hormonal regulation of bulb growth is species-specific. Moreover, ethephon, chlormequat chloride (CCC), and salicylic acid (SA) also markedly increased bulb weight. Conversely, certain hormones, such as abscisic acid (ABA), exhibit inhibitory effects on Hippeastrum growth[62,63]. These findings suggest that the impact of hormones on bulb development is governed by a complex interplay of species specificity, concentration, and application method.

The effects of exogenous hormones on bulb development are closely linked to their regulation of endogenous hormone homeostasis and metabolic activities. In Lilium, auxin treatment has been shown to elevate 6-Benzylaminopurine (6-BAP) levels while reducing Methyl Jasmonate (MeJA) levels and influencing carbohydrate metabolism; GA treatment leads to a decrease in endogenous Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) levels within the bulb[64,65]. In Lycoris, GA downregulates the expression of LrSUS1 and LrSUS2, reducing carbohydrate accumulation while promoting the accumulation of endogenous cytokinins (CK); ABA upregulates the expression of LrSS1, LrSS2, and LrGBSS1, enhancing starch biosynthesis and ultimately promoting bulb development[60,66]. However, the physiological and gene expression changes induced by exogenous hormone treatments in Hippeastrum bulbs remain largely unexplored. Furthermore, the potential regulatory mechanisms underlying hormonal control of Hippeastrum bulb development require further investigation. Addressing these aspects will not only provide new perspectives for theoretical research but also offer valuable guidance for optimizing hormonal applications in production practices.

Carbohydrate distribution and scale function differentiation

-

Hippeastrum bulbs undergo dynamic source-sink transitions during development. In the early stages, both the mother bulb and the one-year-old bulbs serve as source tissues, supplying energy and nutrients for shoot and root growth. As the leaves begin to provide assimilates, one-year-old bulbs transition into sink tissues, accumulating dry weight and starch—a process regulated by light[22]. In Lilium, bulb development is actually a process of starch accumulation involving the significant upregulation of starch synthesis-related genes such as SSS, AGPase, and SBE[67,68]. Regarding starch distribution, Hippeastrum bulbs exhibit distinct spatial heterogeneity. Histological analyses indicate that the mature outer scales contain significantly more starch granules than the inner scales, and the starch granules in the outer scales are notably larger in diameter[69]. Similar patterns have been observed in Lycoris bulbs[70]. Further ultrastructural investigations reveal that within a single scale, starch accumulates predominantly in the outermost parenchyma cells, with lower concentrations in the inner cells[69]. Notably, in Hippeastrum bulb cells, starch granules tend to accumulate near the cell wall, a distribution pattern also observed in Lilium bulbs[69,71]. However, current research on carbohydrate dynamics in Hippeastrum bulbs has primarily focused on histological characterization, with the physiological and transcriptional mechanisms underlying their 'outward' starch accumulation remaining unexplored.

Studies on other bulbous plants provide valuable insights into this phenomenon. For example, studies on Lycoris bulbs have revealed distinct sugar metabolism profiles among the outer, middle, and inner scales; the outer scales primarily accumulate starch, potentially serving as energy storage organs; the middle scales exhibit the highest sugar metabolism activity, with elevated enzymatic activities of AGPase, SSS, and GBSS; whereas the inner scales are enriched in soluble sugars and show high expression of CycD genes, possibly supporting cell division[72]. Similar patterns have been observed in Hippeastrum and Lilium bulbs[73]. These results suggest that the functional differentiation of scales may be closely linked to the heterogeneous distribution of carbohydrates. Notably, the dynamic allocation of carbohydrates during bulb development is likely regulated by sucrose transport genes[73], which mediate materials transport among scales, thereby establishing a finely tuned balance between developmental demands and energy storage. Future research on Hippeastrum bulb development should explore the key genes and regulatory mechanisms governing sugar metabolism across different scales, offering deeper insights into the functional differentiation of scales in bulb development.

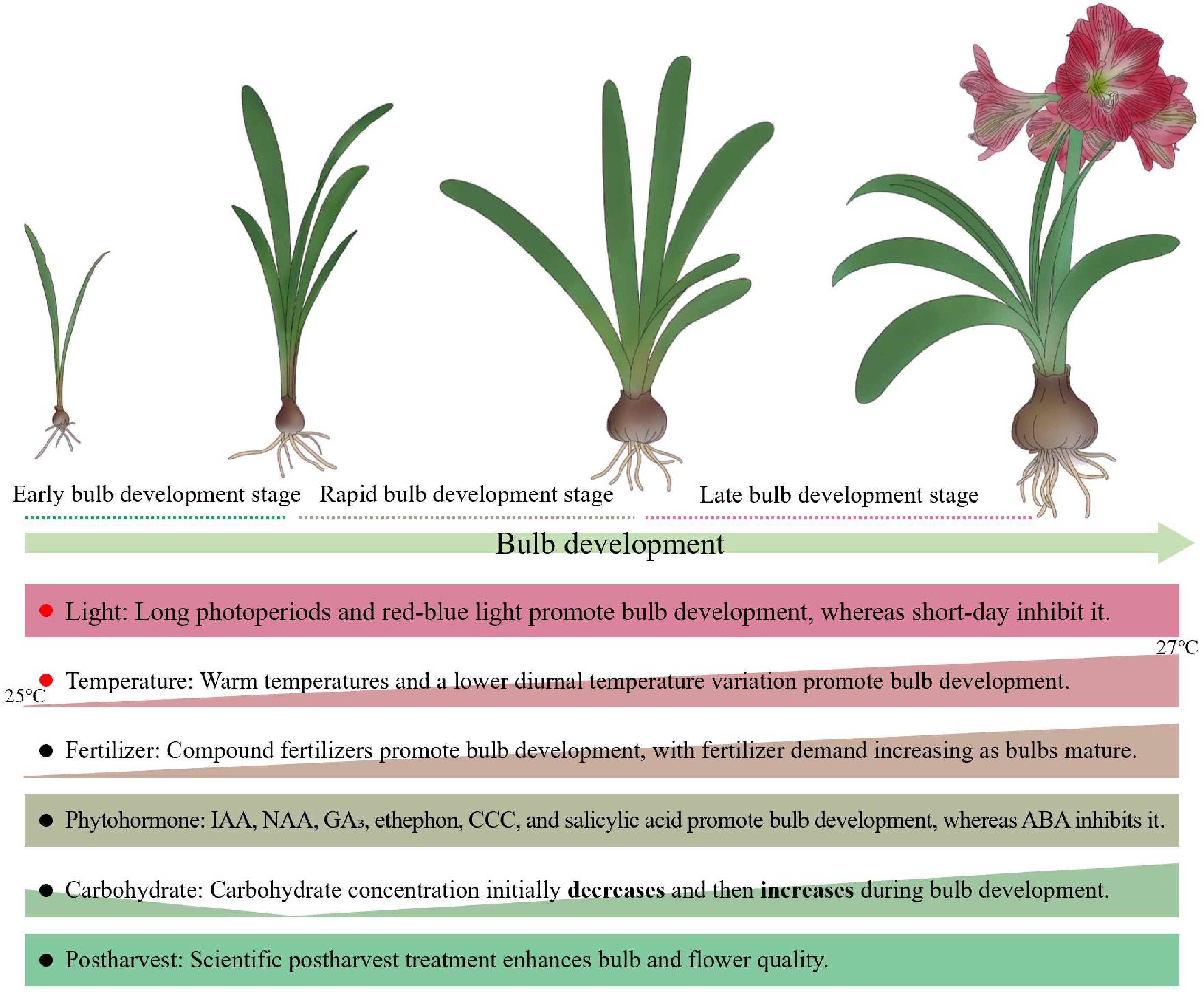

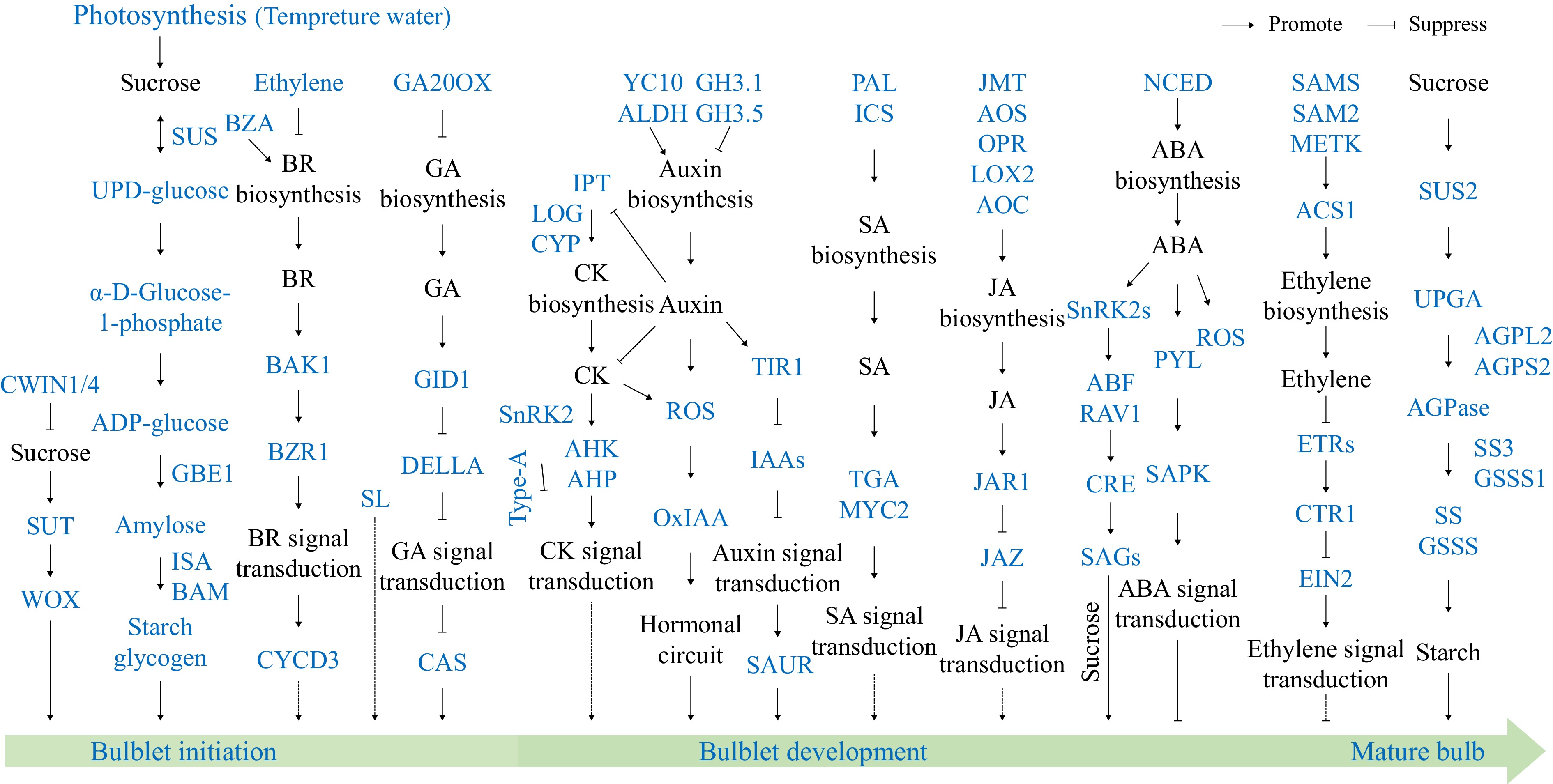

In summary, Hippeastrum bulbs development is a complex process governed by the interplay of multiple factors, including photoperiod, light quality, temperature, water-fertilizer management, hormone homeostasis, and carbohydrate metabolism (Fig. 3). Future research should concentrate on these factors to unravel the regulatory mechanisms underlying bulb development. This will provide both the theoretical foundation and technical pathways necessary to shorten the developmental period, enhance quality, and advance industrial applications.

Figure 3.

Diagram of factors affecting Hippeastrum bulb development. The classification of bulb developmental stages is based on current research on bulbous plants[17,18]. Rectangles indicate that regulatory factors (e.g., light and postharvest treatment) that may exert consistent effects across different developmental stages of Hippeastrum bulbs, or whose stage-specific effects remain insufficiently investigated (e.g., phytohormones). Right triangles indicate that the demand for certain factors (e.g., temperature, fertilizers, and carbohydrates) varies across different developmental stages of Hippeastrum bulbs. Red solid dots highlight factors that may serve as critical determinants of Hippeastrum bulb development. IAA, indole-3-acetic acid; NAA, naphthaleneacetic acid; GA3, gibberellin; CCC, chlormequat chloride; ABA, abscisic acid.

-

Postharvest treatment of Hippeastrum bulbs is a critical step in extending storage life and enabling efficient forcing cultivation. By artificially manipulating environmental conditions and physiological states, forcing cultivation induces plants to reach a specific developmental stage outside their natural season. It is widely used in ornamental horticulture to meet holiday market demands. Proper postharvest management not only enhances flowering quality but also allows for precise control over flowering periods, ensuring the achievement of cultivation and breeding goals. Research indicates that the ability of Hippeastrum scale cutting propagation is significantly influenced by cultivar characteristics and the bulbs' storage duration. With the growing global demand for Hippeastrum, many studies have focused on postharvest treatments. Building upon the fundamental objectives of postharvest management, this section systematically examines the critical operational junctures—specifically, the harvesting timing—and the corresponding technological protocols necessary to achieve these aims, thereby providing robust theoretical and practical support for Hippeastrum postharvest management.

Objectives of postharvest treatment

-

The fundamental objective of postharvest treatment resides in resolving the biological paradox inherent to Hippeastrum bulbs across the harvest-replanting continuum through scientific intervention. This entails simultaneously preserving bulb vitality, regulating developmental progression, and mitigating the risks of storage and premature flowering triggered by environmental or physiological factors.

Flowering regulation and quality enhancement

-

Scientific postharvest treatment helps precisely regulate the flowering time of Hippeastrum, enabling early and multiple blooms that align with market demands for holidays such as the Lunar New Year and Christmas[74]. Additionally, postharvest treatments significantly improve flower quality, improving blooming uniformity, flower-leaf coordination, and overall ornamental effect[74−76]. Research shows that low-temperature treatments, such as storing bulbs at 8–12 °C for 30–60 d, can effectively promote flower bud differentiation, facilitating blooming within approximately 50 d when cultivated at optimal temperatures (22–25 °C)[76,77]. Moreover, for unsold high-cost bulbs, postharvest treatments can stimulate re-flowering, allowing them to retain value in the next year's market, thereby reducing production risks and increasing economic returns[75]. Although current research has predominantly focused on the regulatory effects of postharvest treatments on Hippeastrum's flowering quality and bloom period, maintaining bulb health is equally critical for ensuring subsequent vegetative growth and reproductive efficiency.

Ensuring bulb quality

-

Proper postharvest treatment can extend Hippeastrum bulb storage life, improve survival rates, and minimize economic losses caused by diseases or improper handling. By removing dead roots and inactive tissues, root health is improved, providing a strong foundation for subsequent planting. However, improper treatment may lead to bulb rot, flowering without leaves, or delayed leaf emergence[78]. Therefore, scientific and precise postharvest management is crucial, not only to ensure high flowering rates and quality in the following year but also to facilitate successful forcing cultivation and re-flowering, thereby meeting the increasing market demand for high-quality flowers.

The achievement of the aforementioned objectives hinges on the precise management of two dimensions: first, selecting the optimal harvest timing by comprehensively considering bulb state and market demand, and second, standardizing treatment protocols, which requires the harmonization of environmental modulators with bulb-specific responses. The following sections will elucidate these two critical elements in turn.

Harvest timing

-

The timing of harvest directly influences the development maturity and nutrient storage of Hippeastrum bulbs, which in turn affects propagation efficiency, flowering rates, and quality. Premature or belated harvesting may precipitate inefficiencies in flowering regulation or compromise bulb integrity. Research indicates that the optimal time for scale propagation is usually 30–50 d after flowering (around July), when the bulbs have undergone a vigorous growing period and nutrient reflow is sufficient, better supporting the formation of small bulblets after scale cutting[79,80]. Freshly harvested bulbs, with abundant nutrient reserves, can achieve a 92.1% bulblet formation rate[81]. Thus, harvesting bulbs at maturity provides a strong foundation for subsequent cultivation.

The harvest timing also affects the subsequent flowering of Hippeastrum. In East China, bulbs harvested in October, compared to those harvested in September, exhibit a higher flowering rate under the same storage conditions[76]. This suggests that a slight delay in harvesting promotes better nutrient accumulation and allows for the full development of flower buds, thus improving flowering rates. However, excessively delayed harvesting may result in shorter flower stalks and a delayed flowering period for forcing cultivation. Therefore, in practical cultivation, the harvest timing should be adjusted based on specific cultivation goals.

Postharvest treatment steps

-

Building upon the determination of optimal harvest timing, postharvest processing involves a multi-step treatment to transform the bulbs into a 'controllable state'. These steps include harvesting, pre-treatment, disinfection, grading, and storage (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Diagram of postharvest treatment process for Hippeastrum bulbs. During this process, all leaves should be removed, while the decision to retain or remove the roots should be based on subsequent industry needs, postharvest objectives, storage conditions, and cultivation plans.

Pre-treatment

-

After harvest, Hippeastrum bulbs should be cleaned by removing inactive outer scales, dead roots, dead leaves, and surface contaminants. Healthy bulbs that are firm, without scars and diseases, should be selected for grading, packaging, and storage[9,82,83]. During this process, all leaves should be removed, while the decision to retain or remove the roots should be based on subsequent industry needs, postharvest objectives, storage conditions, and cultivation plans. Generally, for bulbs intended for long-term storage or commercial production, root removal is recommended, whereas for bulbs stored for a short period or used for horticultural planting, retaining the roots is advisable to ensure optimal growth and flowering quality. Studies have shown that cutting leaves while retaining the roots for cold storage results in the best flowering performance, whereas cutting both leaves and roots leads to the poorest outcomes[84]. Consequently, scientifically sound pre-treatment measures are crucial for ensuring high-quality storage and excellent subsequent performance of Hippeastrum bulbs.

Bulb disinfection and grading

-

During harvesting or transportation, Hippeastrum bulbs are often damaged or infected by pests and pathogens, leading to diseases such as red spot disease[83]. To minimize the risk of disease, bulbs should be disinfected before storage[9]. Common disinfection methods include soaking bulbs in a 700-fold dilution of 70% carbendazim for 40–60 min or soaking in an 800-fold dilution of 75% chlorothalonil for 20 min, followed by drying[74,85]. Disinfection can effectively prevent pest and disease infections and enhance the bulbs' health during storage. It is important to avoid using copper-based chemicals (e.g., Kocide), as they may damage the bulbs. Upon completion of disinfection, Hippeastrum bulbs are graded according to their size and quality.

Temperature control

-

Hippeastrum bulb storage typically follows a staged treatment approach. Initially, a short-term treatment at around 27 °C is applied to remove excess moisture, followed by a refrigeration phase. Low-temperature storage adjusts the bulbs' physiological state, laying the foundation for subsequent cultivation and flowering. Research has shown that storing bulbs at 9–10 °C for 30–60 d can effectively synchronize the sprouting of both flower and leaf buds, resulting in uniform flowering[74]. Moreover, for production that requires both early flowering and vigorous plant growth, leaves can be retained during the low-temperature treatment. In practical applications, the refrigeration period should be tailored to specific cultivation goals and production needs to optimize flowering performance and production efficiency.

In summary, the postharvest processing steps and technical key points of Hippeastrum bulbs are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Postharvest treatment process and key technical points for Hippeastrum bulbs.

Processing Detailed approach Purpose/Reason Ref. Harvesting 1. Harvest 30−50 d after flowering.

2. Adjust harvesting time flexibly according to cultivation goals, avoiding overly late harvesting.

3. Harvesting under clear, sunny conditions.1. Bulbs are fully developed, with sufficient nutrient reallocation, which supports the formation of small bulbs.

2. Minimizing the risk of fungal or bacterial infections.[76,79,80] Pre-treatment 1. Remove inactive scales, decayed roots, dead leaves, and surface dirt, and select full, healthy bulbs free of pests and diseases for grading.

2. Retain or remove roots.Eliminate potential disease risks to ensure safe storage and future cultivation. [9,82,83] Bulb disinfection 1. Common disinfectants: Soak bulbs in 700x diluted 70% carbendazim for 40−60 min or soak in 800x diluted 75% chlorothalonil for 20 min.

2. Avoid using copper-based chemicals.Prevent pest and disease infections. [74,83,85] Temperature control 1. Phased treatment: short-term treatment at around 27 °C to remove excess moisture; store at 9−10 °C for 30−60 d.

2. Flexibly arrange the cooling period.1. Promote synchronized sprouting of flower buds and leaf buds, unify flowering time, and improve flowering rate and quality.

2. Extend the storage life of bulbs.[74,77,86] Other treatments Soak the bulb base in a solution containing 150 mg/L GA at room temperature for 1−2 h. Rehydrate and promote root development. [78] Planting or forcing cultivation 1. Plant 60−70 d before desired flowering.

2. Select appropriate varieties and bulb sizes: larger bulbs

(≥ 8 cm in diameter) have higher flowering rates.Table 2. Summary of postharvest treatment techniques for Hippeastrum bulbs.

Treatment category Method Mechanism Detailed approach Physical treatment Optimization of harvest

timingRegulates bulb maturity and ensures adequate nutrient accumulation Harvest 30–50 d after flowering Mechanical pre-treatment Controls pathogens and reduces infection risks Remove dead roots, withered leaves, inactive scales, and surface dirt Cold storage Regulates moisture, suppresses respiration, and delays sprouting Gradual temperature adjustment: (1) Short-term treatment at 27 °C; (2) Storage at 9–10 °C for 30–60 d Chemical treatment Disinfection treatment Inhibits pathogens and reduces fungal/bacterial infections Use carbendazim and chlorothalonil; avoid copper-based chemicals (e.g., Kocide) GA treatment Promotes root development Soak bulbs in a 150 mg/L GA solution for 1–2 h Biological treatment (To be explored) (To be explored) (To be explored) -

With the rapid development of the horticultural industry and the rising demand for bulbous flowers in the consumer market, Hippeastrum has shown significant potential in both ornamental horticulture and medicinal applications. However, research on Hippeastrum remains in its early stages, particularly in areas such as bulb development regulation and postharvest treatment, where several challenges still need to be addressed. Future research should focus on the following areas.

Mechanism of bulb development regulation

-

Hippeastrum bulb development is a complex biological process influenced by environmental factors (such as light, temperature, and cultivation measures) and endogenous signals (Fig. 3). Despite advances in related plant species, the molecular mechanisms governing bulb development in Hippeastrum have not yet been elucidated, especially the specific interactions between environmental factors and bulb development. To address these gaps, future research should focus on systematically observing the bulb development process, utilizing high-throughput omics technologies to analyze the mechanisms of key regulatory factors and metabolic pathways, and through gene functional validation and regulatory network construction, provide a theoretical foundation for optimizing bulb development, improving propagation efficiency, and enhancing commercial performance. In addition, research should explore the effects of exogenous plant growth regulators and fertilizers on bulb development, identifying appropriate concentrations and application timings to provide scientific guidance for improving bulb quality and production efficiency. Notably, Shu et al.[87] conducted a comprehensive review of the regulatory networks governing the formation and development of bulbil structures in plants, including leaf axils, stems, inflorescences, and bulblets; these networks remain hypothetical for Hippeastrum due to the lack of direct molecular evidence. To inspire targeted investigations, this integrative framework was adapted (Fig. 5) as a conceptual roadmap for future studies on Hippeastrum bulb development.

Figure 5.

Integrative regulatory network of bulbil initiation and subsequent development: hormonal, carbohydrate, and environmental mediation. A referenced framework for future research on Hippeastrum (adapted from Fig. 6 of Shu et al.[87]).

Optimization of postharvest treatment and storage technologies

-

Postharvest losses (PHLs) in Hippeastrum bulbs are primarily manifested as bulb rot—resulting from pathogenic infections and microbial contamination—as well as abnormal flower bud development leading to low flowering rates and unpredictable blooming times, and bulb shrinkage caused by carbohydrate depletion during storage. These issues severely constrain their commercial viability and reflect common postharvest challenges across horticultural crops. Currently, postharvest research on Hippeastrum and many ornamental species lacks a systematic theoretical framework. Future studies could benefit from breakthroughs in emerging postharvest technologies developed for vegetables, fruits, and other crops, focusing on targeted preservation techniques (such as 1-MCP inhibitors and modified atmosphere packaging), non-thermal physical preservation methods, intelligent storage systems (such as electronic noses and hyperspectral imaging), and gene-editing-assisted breeding to effectively address the current challenges.

Integration of smart and industrialized production technologies

-

To meet market demand and reduce production costs, future research should integrate modern intelligent agricultural technologies to optimize Hippeastrum cultivation management. By advancing the breeding of superior varieties and developing efficient propagation techniques, it will be possible to improve cultivation practices and nutrient supply strategies, enabling large-scale production of high-quality bulbs and promoting the intelligent, intensive, and efficient development of the Hippeastrum industry. At the same time, research should explore the extraction and application of medicinal components in Hippeastrum, unlocking its vast potential in medicinal resource development.

In summary, future research on Hippeastrum bulb development and postharvest treatment should combine fundamental theories with practical production needs, focusing on interdisciplinary collaboration and technological innovation. By thoroughly analyzing the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying bulb development and optimizing cultivation and management techniques, this research will contribute to the sustainable development of the Hippeastrum industry. It will also provide significant economic and ecological benefits to the horticultural industry and related fields.

This research was funded by the Shanghai Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (Grant No. 2024-02-08-00-12-F00007), and Shanghai Science and Technology Program (Grant No. 24N22800600).

-

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: literature collection and organization: Shao L, Li X, Zhou L, Zhu J; manuscript preparation: Shao L; manuscript revision: Yang L, Zhang Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Lingmei Shao, Liuyan Yang

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Shao L, Yang L, Li X, Zhou L, Zhu J, et al. 2025. From bulb development to postharvest treatments: advances in Hippeastrum spp. research and industry applications. Ornamental Plant Research 5: e026 doi: 10.48130/opr-0025-0030

From bulb development to postharvest treatments: advances in Hippeastrum spp. research and industry applications

- Received: 18 January 2025

- Revised: 04 May 2025

- Accepted: 19 May 2025

- Published online: 27 June 2025

Abstract: Hippeastrum spp., renowned as highly sought-after perennial bulbous flowers, have gained increasing popularity in landscape gardening and festive markets due to their unique ornamental value. However, the high cost of bulbs and the lack of advanced techniques for regulating bulb development pose significant challenges to their industrialization. This review synthesizes recent progress in the study of Hippeastrum bulb morphology, developmental regulatory mechanisms, and postharvest treatments. It highlights the effects of factors such as light, temperature, nutrients, and phytohormones on bulb growth while also summarizing cultivation techniques and strategies for regulating bulb development. Based on current research, regulating bulb development emerges as a pivotal approach for improving bulb quality, reducing production costs, and enhancing both ornamental and medicinal potential. This review aims to provide a theoretical foundation for advancing the understanding of Hippeastrum bulb development and promoting its industrial-scale production, thereby fostering further research in this field.