-

Pepper (Capsicum spp.), a significant vegetable and spice crop, is extensively cultivated globally. In China, it ranks as the foremost vegetable crop by cultivation area, exceeding 21,000 km2[1]. With the continuous expansion of pepper cultivation areas and intensive exchange of germplasm resources, there has been a severe threat to the production of pepper due to viral diseases[2]. At present, over 70 viruses have been documented globally in relation to pepper cultivation, and more than 30 of them have been recorded in China[3−5]. These viruses include Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), Potato virus Y (PVY), Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV), Broad bean wilt virus 2 (BBWV2), Pepper mild mottle virus (PMMoV), and Pepper yellow leaf curl virus (PepYLCV). TMV and CMV have become the predominant pathogens in most regions due to their widespread distribution and high pathogenicity[6,7].

Pepper is also widely planted in fields, plastic tunnels, and greenhouses in Gansu and Ningxia (China). Several previous studies identified the pathogen composition and the distribution of dominant populations of viral diseases in pepper in Gansu and Ningxia. Xu et al. found CMV to be the predominant pathogen affecting pepper plants in Gansu, with infected plants exhibiting symptoms ranging from mild to severe mosaic patterns, stunted and bushy growth, vein necrosis, and apical shriveling[8]. Wen et al. identified that five viruses, including TMV, CMV, PMMoV, PVY, and Tobacco etch virus (TEV), infected pepper plants in the Hexi region of Gansu, with TMV and CMV being the predominant pathogens[9]. Another study found that sweet peppers were primarily infected by three viruses, CMV, PMMoV, and Alfalfa mosaic virus (AMV), in Ningxia, and the prevalence of CMV was significant[10]. However, those studies were conducted a long time ago. With the exchange of germplasm resources and the promotion of new varieties between provinces and even internationally, it is worth studying whether the types and quantities of viruses have changed. Therefore, it is vital to assess the current epidemic status and pathogen species of pepper viral diseases for effective prevention and control in Gansu and Ningxia.

The climate instability caused by global warming has intensified the difficulty of controlling the spread of plant viral diseases[11−13]. The cost of preventing and treating viral diseases usually accounts for a large proportion of production costs[4]. Most viruses that infect pepper are transmitted through arthropod vectors, such as aphids, whiteflies, or thrips[14,15]. So far, the use of insecticides to eliminate or suppress the population of these pests remains the main strategy for preventing and controlling viral diseases[16]. Generally, pests can develop resistance to chemicals in use[17], which brings new challenges to the control of pests and viruses. Given the limitations of chemical control and its environmental impact, resistant breeding is the safest and most effective way to control viral diseases.

Molecular marker-assisted selection (MAS) is a crucial way for resistance breeding in crops[18,19]. This approach eliminates the need for full plant maturity or inoculation, reducing the timeline and generations required compared to traditional phenotypic selection[20,21]. Studies have shown that the L gene provides resistance to TMV in pepper. There are four resistant alleles for the L locus, L1, L2, L3, L4 [22]. In recent years, many molecular markers of the L gene have been reported. For instance, three SCAR markers, namely PMFR11269, PMFR11283, and PMFR21200, are located 4.0 cM from the L3 locus[23]. These markers were derived from two RAPD markers, E18272 and E18286. There are multiple resistance genes to PVY in pepper, including pvr1, pvr21, pvr22, pvr3, pvr4, pvr5, pvr6, and pvr7, and molecular markers E41/M49-645, UBC191432, SCUBC191432, and Pvr1-S have been developed[24−27]. In addition, molecular markers for the resistance to CMV, namely CaTm-int3HRM and InDel-2-134, for the resistance to PMMoV, namely L4-SCAR, and for the resistance to PepYLCV, namely Chr-lcv-7 and Chr-lcv-12, have been successfully developed based on their resistance loci[28−31]. These molecular markers provided convenience for the molecular marker-assisted selection of the antivirus genes in pepper.

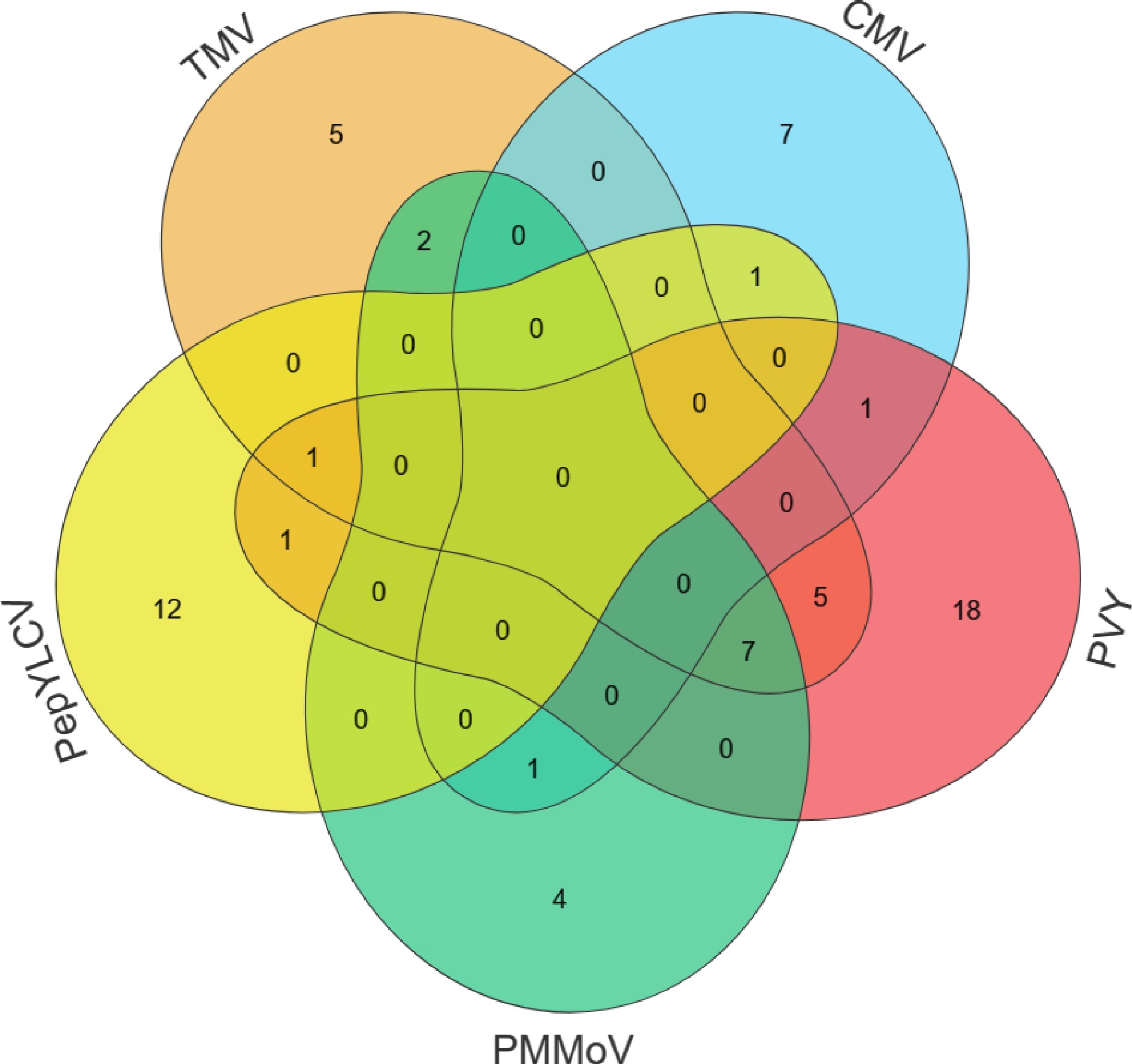

In this study, the occurrence of viral diseases was investigated and identified in Gansu and Ningxia, China. Our findings revealed that there were nine distinct viruses detected in 18 out of 21 samples, and mixed infections by multiple viruses are common. Additionally, we assessed the resistant loci of five prevalent viruses among 226 pepper germplasm accessions by established molecular markers, and 65 accessions were detected to contain at least one resistant locus. These findings will be beneficial for the innovation of antiviral germplasm and the breeding of antiviral cultivars in pepper.

-

A total of 21 plants suspected to be infected with viral diseases were collected from Gansu and Ningxia for virus detection (Supplementary Table S1). Additionally, 226 pepper germplasm accessions, affiliated with three species, including annuum L., chinense Jacq., and baccatum L., were used to assess the resistance to viral diseases, which were provided by the Vegetable Molecular Breeding Laboratory at the College of Horticulture, Gansu Agricultural University (Supplementary Table S2).

Extraction of DNA and RNA

-

The genomic DNA of the plants was extracted using the CTAB method, and its concentration and quality were evaluated using a Micro-spectrophotometer and 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The total RNA was extracted using the RNA simple Total RNA Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China), and the cDNA was synthesized using the onScript First-strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Genesand, Changsha, China).

Detection of viral diseases

-

The specific and reliable primers reported previously were used to detect ten common viruses in 21 samples that were suspected to be infected with viral diseases, respectively (Table 1). The occurrence of viral diseases was assessed based on whether the specific target sequences of viruses could be successfully amplified. The PCR amplification system consisted of a total volume of 10 μL reaction solution, including 5 μL of 2 × Taq PCR Master MIX II (Tiangen, Beijing, China), 1 μL of DNA template (100 ng/μL), 0.5 μL of forward primer, 0.5 μL of reverse primer (10 μM), 3 μL of ddH2O. The PCR reaction procedure was performed on a Gene Explorer (Bioer, Hangzhou, China) as follows: pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min; Denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 52−58 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 50 s, for a total of 35 cycles; final extension at 72 °C for 5 min, followed by preservation at 4 °C.

Table 1. Primers for identification of 10 viruses.

Virus Forward sequence (5'–3') Reverse sequence (5'–3') Fragment size

(bp)Annealing

temperature (°C)Ref. CMV TCTCATGGATGCTTCTCCGCG CCGTAAGCTGGATGGACAACC 760 55 [32] ChiVMV AAGATATGGGCTTCAAGAAACCTTACCG CCTACCCTACCGTCCAGTCCGAACATCCT 174 58 [33] ChiRSV ATGAACTGTACGCCGAAGGG AGTCCGATCGCCTATGAGGA 897 53 [34] TMV GTTCTTGTCATCTGCGTGGG GCTCTCGAAAGAGCTCCGAT 406 55 [34] TSWV TCACTGTAATGTTCCATAGCAA AGAGCAATYGTGTCAATTTTATTC 861 52 [32] ToMV GTTTCATTGTGCTGTTGAGTAC AGAAGTACCCATATTGCTTCTTG 362 57 [35] ToMMV ATGTCTTDCGCTATTACTTCTCCG CTCTGGTTGTAGAAACCTGTT 480 56 [35] PVY GGCATACGGACATAGGAGAAACT CTCTTTGTGTTCTCCTCTTGTGT 447 57 [36] PMMoV ATGGCTTACACAGTTTCC TTAAGGAGTTGTAGCCCAG 474 57 [37] BBWV2 AGTTATATGCTTGGGCAAGCGCATG CATGAACATTCCCCATCTCCACGTG 490 57 [32] Germplasm exploration for resistance to viral diseases in pepper

-

The SCAR markers PMFR11283, which are linked to the L3 gene, were employed to filter 226 germplasm accessions for resistance to TMV in pepper (Table 2). InDel-2-134 was utilized for screening CMV resistance. In addition, PVY-CAPS, L4-SCAR, and Chr-lcv-7 were used to evaluate the resistance to PVY, PMMoV, and PepYLCV, respectively. The PCR amplification system and procedure are the same as described above. The amplification products were differentiated by 12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis or 2% agarose gel electrophoresis after PCR amplification.

Table 2. Marker information for identification of resistance to virus disease in pepper germplasm.

Virus Marker ID Forward primer (5'–3') Reverse primer (5'–3') Ref. TMV PMFR11283 CTGCAGAACAACAATGGCACG GGACTGCAGAGGAGGAAGC [23] CMV InDel-2-134 TGCTTCAGTTGAGTTGTCCA TAAATCCCCTTGTGGTGGCT [29] PVY PVY-CAPS CGAAGAGAGAAGGTC TCAGGGTAGGTTATT [24] PMMoV L4-SCAR ATCGATGCACCCCTCGTTTTAATC GAGCAGTGTGGAGTGTCTATTGCTCA [30] PepYLCV Chr-lcv-7 CTGATAACTGACAGTTTAGATAGGAATTGG CAACTCAGTCTATAACCGGTGTATG [31] Artificial inoculation of TMV and CMV

-

The accessions harboring the resistant loci of TMV and CMV, according to the results of MAS, were artificially inoculated at the pepper seedling stage. The accession c210, which exhibits high sensitivity to TMV and CMV, was provided by our lab as the control. One gram of susceptible leaves infected by TMV or CMV was weighed and ground with 50 mL of 0.01 mol/L phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The supernatant was collected for inoculation after centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 15 min. Seedlings were kept in the dark for 24 h before inoculation. Subsequently, a small amount of emery was sprinkled on the leaves that had been pre-inoculated. The inoculation method used was friction inoculation[32]. The procedure is as follows: a swab was utilized to pick up the inoculation suspension. Micro-injuries were then induced by gently rubbing the swab on the leaf surface. In total, three inoculations were carried out, with a 3 d interval between each. Additionally, TMV inoculation was performed during the four-leaf stage in pepper seedlings, whereas CMV inoculation was conducted during the two-leaf stage. The inoculated plants were cultivated in an artificial climate chamber under conditions of 28/20 °C and 20 % relative humidity under a 16-h/8-h cycle (light/dark).

Standards for disease level and disease index

-

On the 21st day after inoculation, the disease level and disease index (DI) of the inoculated plants was evaluated respectively, with five plants being surveyed for each type of disease. The methods for disease assessment adhere to the protocols detailed in the standards 'Rules for evaluation of pepper for resistance to diseases - Part 3: Rule for evaluation of pepper for resistance to tobacco mosaic virus (NY/T 2060.3-2011, China)' and 'Rules for evaluation of pepper for resistance to diseases - Part 4: Rule for evaluation of pepper for resistance to cucumber mosaic virus (NY/T 2060.4-2011, China)'. The disease levels of TMV and CMV were divided into six grades (Supplementary Tables S3 & S4), and the DI was calculated as follows:

$ DI=\frac{\sum \left(s\times n\right)}{N\times S}\times 100 $ Among them, 's' denotes the representative value of each disease level; 'n' signifies the number of plants in each disease level; 'N' represents the total number of plants investigated; 'S' indicates the representative value of the highest disease level. The resistance of pepper to TMV and CMV was divided into immune (I), highly resistant (HR), resistant (R), moderately resistant (MR), susceptible (S), and highly susceptible (HS) based on DI (Table 3).

Table 3. Evaluation criteria of resistance to TMV and CMV in pepper.

Resistance Disease index (DI) Immune (I) DI is 0 Highly resistant (HR) DI is greater than 0 and less than 10 Resistant (R) DI is greater than or equal to 10 and less than 20 Moderately resistant (MR) DI is greater than or equal to 20 and less than 40 Susceptible (S) DI is greater than or equal to 40 and less than 60 Highly susceptible (HS) DI is greater than or equal to 60 and less than or equal to 100 -

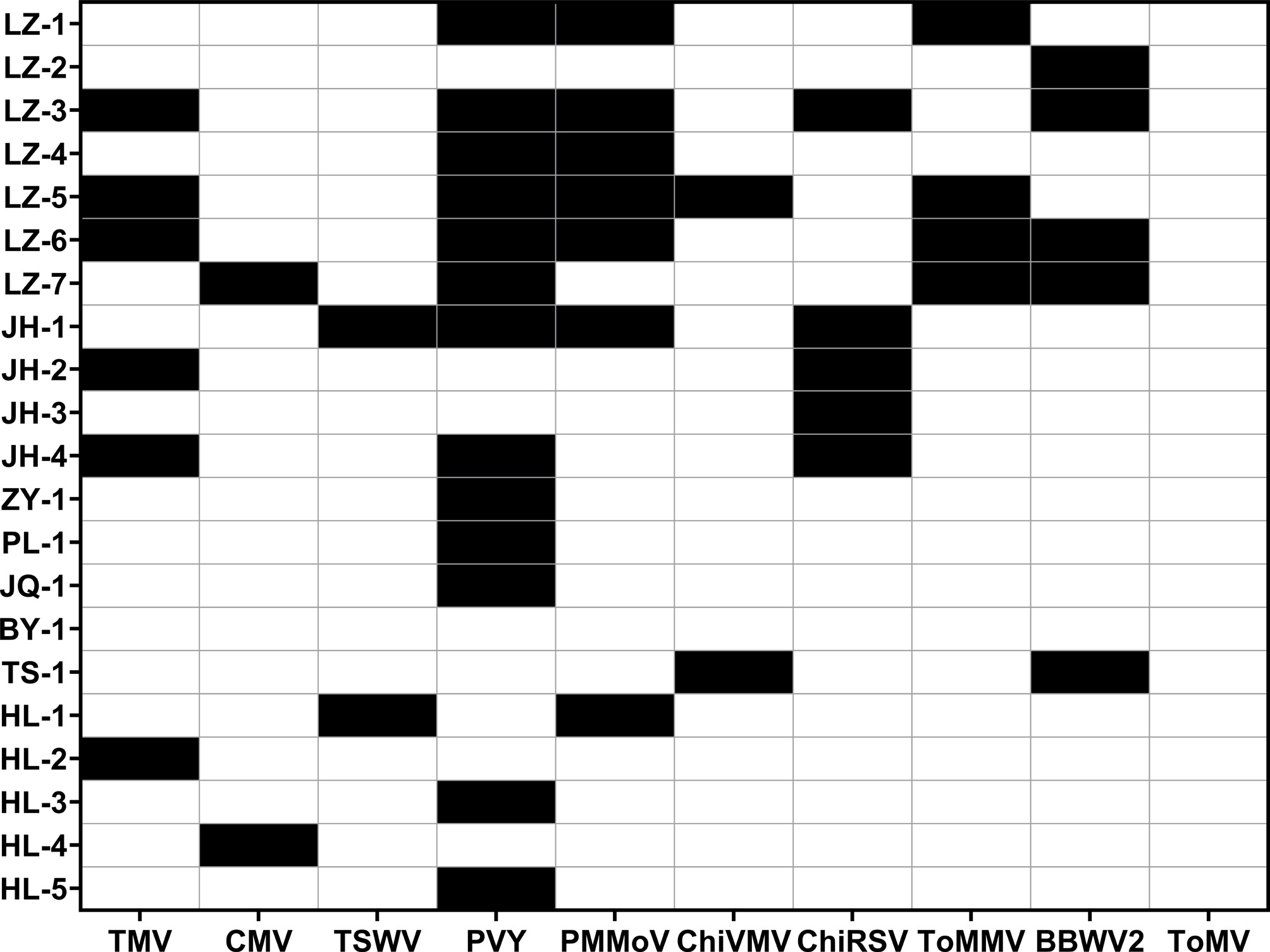

Plants with shrinkage, yellowing, necrosis, and mosaic leaves were suspected to be infected with viral diseases. To ascertain the distribution of viral diseases, molecular identification was performed on 21 germplasm samples that were suspected to be infected with viruses. The results revealed that nine viruses, including TMV, CMV, TSWV, PVY, PMMoV, ChiVMV, ChiRSV, ToMMV, and BBWV2, were detected in 18 samples (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table S5). Notably, the detection rate of PVY ranked first at approximately 61.90%, followed by PMMoV and TMV, with rates of 33.3% and 28.6%, respectively. While CMV, TSWV, and ChiVMV had the lowest detection rates, accounting for approximately 9.52%. Furthermore, 11 samples displayed mixed infections. Specifically, four samples exhibited dual infections (LZ-4, JH-2, TS-1, and HL-1), two samples had triple infections (LZ-1 and JH-4), two had quadruple infections (LZ-7 and JH-1), and three samples showed penta-infections (LZ-3, LZ-5, and LZ-6).

Figure 1.

Viral diseases detection results of 21 samples. Black boxes signify the detection of viral diseases, whereas the white boxes indicate none.

Identification of germplasm accessions with resistance to TMV and CMV in pepper

-

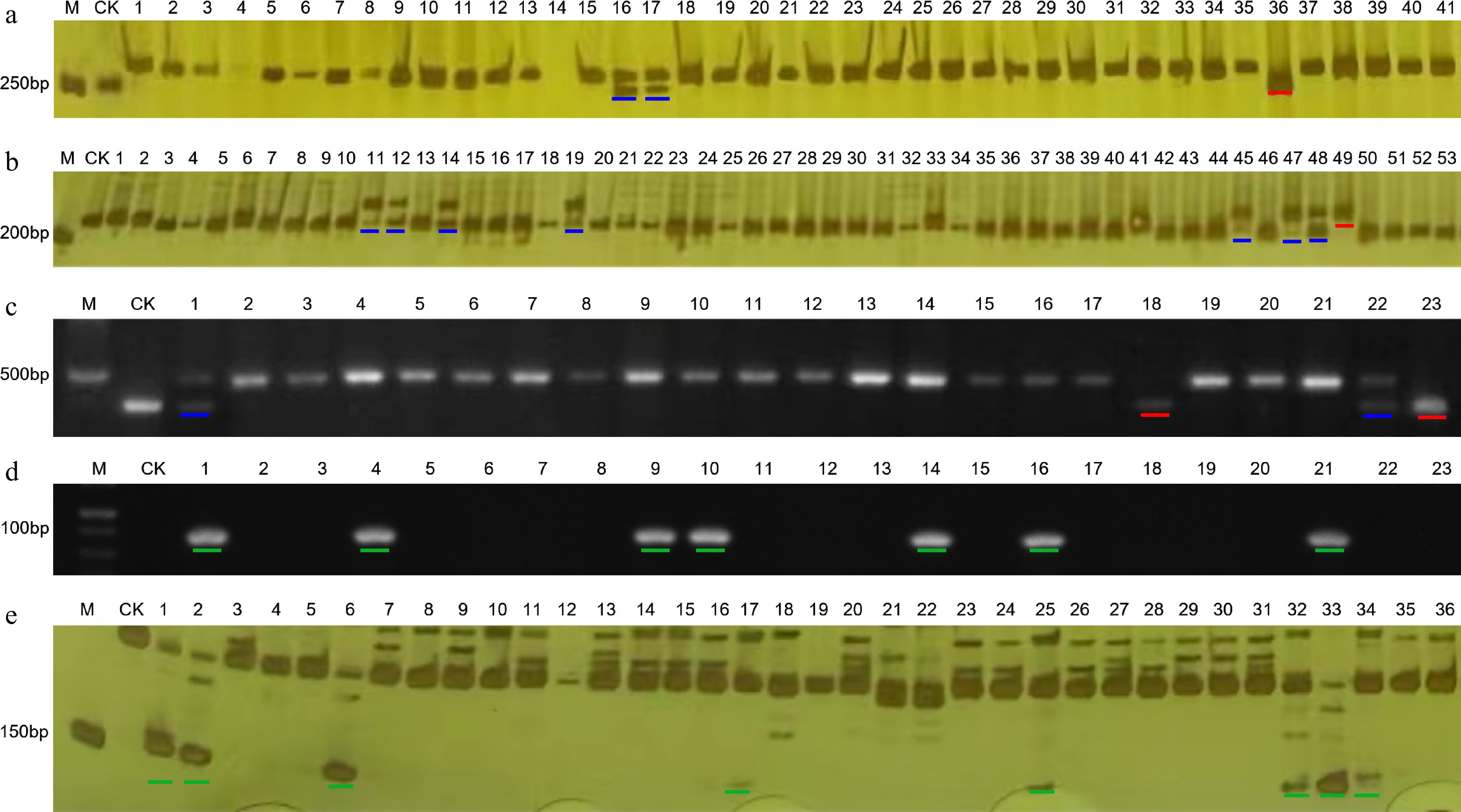

The resistance to TMV of 226 germplasm accessions of pepper was assessed using the co-dominant marker PMFR11283. The homozygous genotype with 270 bp and the heterozygous genotype with 270 and 283 bp represented the genotype of resistance to TMV, while the homozygous genotype with 283 bp indicated the susceptible genotype (Fig. 2a). The results showed that 20 accessions exhibited resistance to TMV, which accounted for 8.85% of the total (Table 4).

Figure 2.

The genotyping results of some germplasms obtained by molecular markers. (a) Marker PMFR11283. (b) InDel-2-134 marker. (c) Marker PVY-CAPS. (d) Marker L4-SCAR. (e) Marker Chr-lcv-7. M: DNA marker; CK: negative control. The red line indicates a homozygous genotype for resistance to disease, while the blue line indicates a heterozygous genotype for resistance to disease. The green lines represent the disease-resistant genotypes indicated by dominant markers.

Table 4. Statistics of germplasm accessions with resistance to viral diseases in pepper.

TMV (PMFR11283) CMV (InDel-2-134) PVY (PVY-CAPS) PMMoV (L4-SCAR) PepYLCV (Chr-lcv-7) A98, SP14, SP16, SP18, SP21, SP27, SP39, SP41, SP44,

SP45, SP46, SP48, SP55,

SP56, SP57, SP64, SP108, SP113, Suxuan 1,

Shenglong 4A33, SP34, SP35, SP37, SP42, SP68, SP70, SP71, SP72, SP79 A43, A45, A83, A88, SP14, SP16, SP19, SP21, SP36, SP37, SP38, SP41, SP44, SP45, SP46, SP47, SP48, SP50, SP51, SP53, SP54, SP55, SP56, SP62, SP64, SP65, SP66, SP93, SP94, SP96, SP97, SP108, SP113 A70, A78, SP14, SP16, SP21, SP40, SP48, SP55, SP56,

SP57, SP64, SP71, M4,

Suxuan 1A4, A22, A80, A89, A92, A97, SP35, SP51, SP90, SP106, SP108, R3, R8, R10, R11 The InDel-2-134 marker, which was a co-dominant marker and linked to the resistant locus qCmr2.1 of CMV, was used to evaluate the resistance to CMV. The resistant genotype was 230 bp or a co-existence of 230 and 211 bp genotypes, while the susceptible genotype was 211 bp (Fig. 2b). The results showed that 10 accessions harbored CMV resistance loci, representing 4.42% of the total accessions (Table 4).

Identification of germplasm accessions with resistance to PVY, PMMoV, and PepYLCV

-

Another co-dominant marker, PVY-CAPS, was used to evaluate the resistance of pepper germplasm accessions against PVY. A fragment of 444 bp implied homozygous resistance to PVY, and a hybrid of 444 and 458 bp represented heterozygous resistance (Fig. 2c). On the contrary, the 458 bp meant to be susceptible. At last, a total of 33 accessions were detected to contain resistant loci of Pvr4 (Table 4).

The L4-SCAR marker, a dominant marker, was used to screen the PMMoV-resistant pepper germplasm. A 102 bp fragment could be amplified in resistant genotypes, while no PCR product was detected in susceptible samples (Fig. 2d). Finally, 14 accessions were identified to include resistant loci of L4 (Table 4).

Additionally, another dominant marker, Chr-lcv-7, was used to explore the appearance of peplcv-7, the loci related to the resistance to PepYLCV in pepper. There was a specific fragment of 151 bp in resistant genotypes and no product in susceptible genotypes (Fig. 2e). It was indicated that 15 accessions were identified as PepYLCV-resistant using Chr-lcv-7 marker, representing 6.64% of the total (Table 4).

Verification of artificial inoculation of resistance to TMV germplasm accessions

-

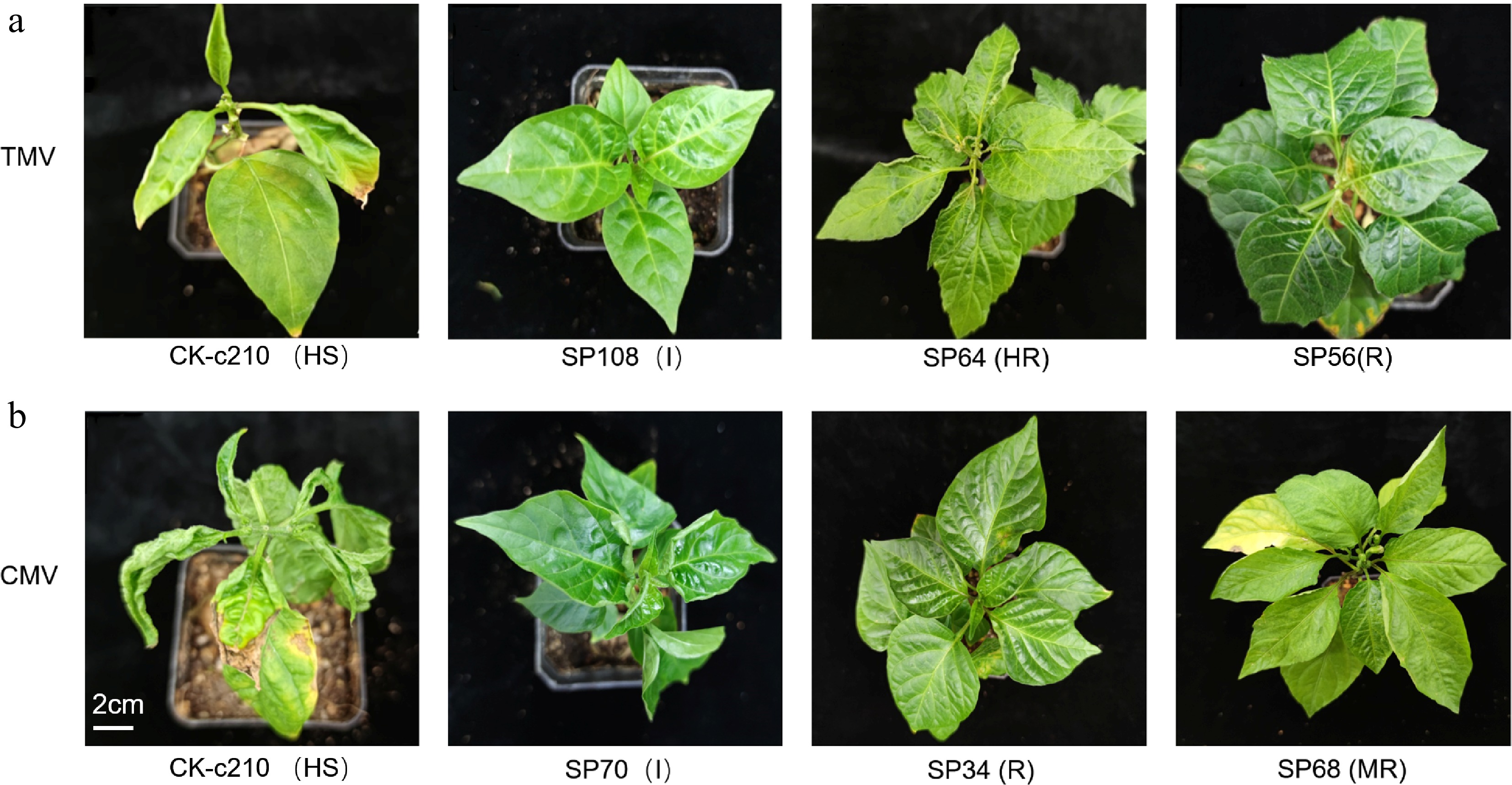

To evaluate the reliability of resistant accessions against TMV by MAS, five resistant accessions selected by PMFR11283, including A98, SP39, SP56, SP64, and SP108, were chosen for artificial inoculation with TMV during the seedling stage (Fig. 3a). The results showed that SP39 and SP108 were I and had no infection symptoms with a DI of 0. A few leaves on individual plants of SP64 exhibited slight desiccation with DI of 4.4, suggesting that the plants were HR. Secondly, a few leaves of SP56 and A98 plants exhibited acute, small yellow spots with DI of 11.1, suggesting R. However, the HS accession, c210, showed severe symptoms with DI of 73.3. In addition, TMV in inoculated plants was detected by TMV-specific primers, and the results indicated that no TMV was identified, which further proved that PMFR11283 and the resistant accessions selected were reliable.

Figure 3.

Artificial inoculation of germplasm accessions resistant to TMV and CMV in peppers. (a) Phenotypes of plants inoculated with TMV for 25 d. (b) Phenotypes of plants inoculated with CMV for 25 d.

Verification of artificial inoculation of resistance to CMV germplasm accessions

-

Five resistant accessions selected by InDel-2-134, namely SP34, SP42, SP68, SP70, and SP72, were inoculated with CMV (Fig. 3b). The results indicated that the HS accession, c210, exhibited extremely severe symptoms with DI of 91.1. SP70 exhibited no symptoms with DI of 0. A mild mosaic pattern was observed on a few leaves of SP34 and SP42 with DI of 15.5, demonstrating that the plants were resistant to CMV. The individual leaves of SP68 and SP72 were etiolated and slightly mosaic on the middle and upper leaves, and the DI were 22.2 and 28.9, respectively, which suggested that the resistance level to CMV of SP68 and SP72 was classified as MR. Furthermore, no amplified products were detected in the inoculated plants by specific primers of CMV. Two strategies, DI and PCR, demonstrate that the InDel-2-134 marker and the CMV-resistant accessions were also dependable.

-

In recent years, the incidence of viral diseases has been increasing, which undermines the sustainable development of the production of pepper. Previous studies showed that the major viruses infecting pepper plants were TMV and CMV in Gansu and Ningxia, with a combined infection rate of 77.7%[9]. This is consistent with the characteristics of virus lineages in other main production areas of pepper in China, such as Guangdong and Shandong[7,38]. However, this study found that the PVY and PMMoV were highly prevalent in 18 infected samples, whereas the detection rates of TMV and CMV were significantly lower. It is suggested that the dominance of viruses is shifting from TMV and CMV to PVY and PMMoV in Gansu and Ningxia. There were five viral diseases affecting peppers in Gansu as previously reported, namely TMV, CMV, PMMoV, PVY, and TEV[9]. In this study, nine viruses, including TMV, CMV, TSWV, PVY, PMMoV, ChiVMV, ChiRSV, ToMMV, and BBWV2, were detected in pepper plants in Gansu and Ningxia based on the infected germplasm collected. The occurrence of viruses such as ChiVMV and BBWV2 can be ascribed to both the frequent promotions of cultivars and the indirect dissemination facilitated by media or alternative biological vectors.

This study found that there was a high prevalence of mixed viral infections in the samples. For example, samples LZ-4, JH-2, TS-1, and HL-1 were infected with two viruses, LZ-1 and JH-4 with three, LZ-7 and JH-1 with four, and LZ-3, LZ-5, and LZ-6 with five. Mixed viral infections pose significant risks to the growth and development, yield, and quality of pepper, with the severity of effects varying depending on the specific viral combinations. These interactions can be categorized into synergistic or antagonistic types[39]. Synergistic interactions, such as helper dependence—where one virus facilitates the replication or transmission of another, lead to exacerbating the severity of the disease. In contrast, antagonistic interactions occur when one virus suppresses the fitness of another[40,41]. Notably, synergistic effects predominated in most cases, amplifying disease trends. Previous studies demonstrated that mixed infections involving CMV, PVY, and TMV significantly reduced biomass and production in pepper, with the combination of CMV + TMV causing the most severe losses (44% biomass reduction, 52% yield decline)[42]. Similarly, Kim et al. reported that simultaneous coinfection with CMV, PMMoV, and PepMoV induced more pronounced CMV-induced symptoms compared to single infections, highlighting the role of synergistic interactions in intensifying pathological outcomes[43].

Mapping resistance genes and developing molecular markers form the foundation for crop improvement and genetic breeding[44]. The PMFR11283 marker was associated with the L3 locus and co-segregated with the resistance QTL locus, which confers resistance to TMV pathotypes P0, P1, and P1,2[23]. The PMFR11283 and L4SC340 markers, resistance to TMV was evaluated in 62 pepper accessions by Hudcovicová et al.[45]. A total of three resistant genotypes were identified using the PMFR11283 marker. However, the L4SC340 marker did not exhibit any polymorphism, and it is believed that the applicability of the marker depends on the genetic background of tested breeding accessions. In this paper, a total of 20 accessions resistant to TMV were identified by marker PMFR11283.

Two QTLs, qCmr2.1 and qCmr11.1, were identified by Guo et al.[46]. The qCmr2.1 was a major QTL of resistance to CMV, and the Indel-2-134 marker was found to be linked to qCmr2.1[29]. Guo et al. used Indel-2-134 markers to screen for resistance to CMV in 109 pepper accessions. The results showed that there were 44 accessions carrying resistant fragments[46]. In this study, we identified 10 CMV-resistant accessions using the Indel-2-134 marker.

As is widely known, the Pvr4 resistance gene in pepper confers complete resistance to the pathotypes of PVY. Subsequently, the codominant AFLP marker E41/M49-645 located 2.1 cM from Pvr4 was transformed into a PVY-CAPS for more accurate detection and tracking of this resistance gene by Caranta et al.[24]. In this study, a total of 33 accessions were identified as carrying the resistant loci of Pvr4. In addition, the L4 gene was reported to show the strongest resistant to PMMoV with a broad spectrum. L4-SCAR was a specific linkage SCAR marker developed by Lee et al. based on L4 resistance locus, with an identification accuracy of more than 90.5%[30]. Here, a total of 14 accessions were identified as harboring the L4 resistance locus using the L4-SCAR marker. Moreover, Siddique et al. carried out QTL mapping for the resistance to PepYLCV gene in pepper. A total of three QTLs, peplcv-1, peplcv-7, and peplcv-12, were detected, and they developed two markers, namely Chr7-LCV-7 and Chr12-LCV-12[31]. The QTL peplcv-7 explained 31.7% of the phenotypic variation with a LOD score of 8.6, indicating that it was the main resistance locus. The results of this study showed that 15 accessions were identified as resistant to PepYLCV using a Chr7-LCV-7 marker.

All in all, 226 accessions were assessed for resistance to five viral diseases in pepper in this study, and 65 accessions possess resistance to diseases. Among them, 46 plants exhibited single resistance, 11 plants displayed double resistance, and three plants showed triple resistance (Fig. 4 & Table 5). It is possible that subsequent breeding efforts can systematically screen and incorporate diverse resistance genes by backcross breeding combined with MAS for these abundant resistant germplasms, thereby accelerating varietal improvement. Our research serves as a solid foundation for the development of novel, comprehensively disease-resistant varieties in pepper.

Table 5. Statistics on pepper germplasm accessions resistant to viral diseases.

Category Pattern Germplasm accessions Single TMV A98, SP18, SP27, SP39, Shenglong 4 CMV A33, SP34, SP42, SP68, SP70, SP72, SP79 PVY A43, A45, A83, A88, SP19, SP36, SP38, SP47, SP50, SP53, SP54, SP62, SP65, SP66, SP93, SP94, SP96, SP97 PMMoV A70, A78, M4, SP40 PepYLCV A4, A22, A80, A89, A92, A97, R10, R11, R3, R8, SP106, SP90 Double TMV + PMMoV SP57, Suxuan 1 TMV + PVY SP41, SP44, SP45, SP46, SP113 PVY + PepYLCV SP51 CMV + PepYLCV SP35 CMV + PMMoV SP71 CMV + PVY SP37 Triple TMV + PVY + PepYLCV SP108 TMV + PVY + PMMoV SP14, SP16, SP21, SP48, SP55, SP56, SP64 -

This study utilized molecular markers to identify nine viral diseases in peppers from the Gansu and Ningxia regions of China. The identified diseases included TMV, CMV, TSWV, PVY, PMMoV, ChiVMV, ChiRSV, ToMMV, and BBWV2. Furthermore, the study screened 226 pepper germplasm accessions for resistance to five prevalent viral diseases—TMV, CMV, PVY, PMMoV, and PepYLCV—and found that 65 of these accessions exhibited resistance to one or more viruses. These results are highly significant for the advancement of disease-resistance breeding programs in pepper.

This work has been supported by the Science and Technology Major Project (Agriculture) of Gansu Province, China (24ZDNA005), the Industrial Support Plan Project of Department of Education of Gansu Province, China (2025CYZC-041), and the Primary Research & Development Plan of Gansu Province, China (25YFNA034).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wei B, Zhang T; performing most of the experiments and data analysis: Guo N, Zhang R, Wang Y; experiment and data analysis assistance: Wang L, Zhang T; draft manuscript preparation: Zhang T; manuscript revision: Xia G. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Sample information for detection of virus disease in pepper.

- Supplementary Table S2 Sample information of germplasms in pepper.

- Supplementary Table S3 Grading criteria for TMV infection in peppers.

- Supplementary Table S4 Grading criteria for CMV infection in peppers.

- Supplementary Table S5 Detection results of pepper virus disease in Gansu and Ningxia.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang T, Guo N, Zhang R, Wang Y, Xia G, et al. 2025. Molecular detection of viral diseases and the resistance of germplasm in pepper. Vegetable Research 5: e030 doi: 10.48130/vegres-0025-0024

Molecular detection of viral diseases and the resistance of germplasm in pepper

- Received: 03 April 2025

- Revised: 04 June 2025

- Accepted: 01 July 2025

- Published online: 20 August 2025

Abstract: Viral diseases, which generally cause wrinkled, yellow, and fallen leaves, are prevalent worldwide and cause significant damage to the quality and yield of pepper, even resulting in failed harvests. In this study, molecular identification was performed on 21 plant samples suspected to be infected with viruses in pepper, which were collected from various regions in Gansu and Ningxia, China. The results showed that nine viruses, including TMV, CMV, TSWV, PVY, PMMoV, ChiVMV, ChiRSV, ToMMV, and BBWV2, were detected in 18 samples. It is worth noting that 11 samples were found to be infected by at least two viruses. In addition, 226 pepper germplasm accessions were screened for resistance to TMV, CMV, PVY, PMMoV, and PepYLCV using molecular markers. Among the germplasms, there were 46, 11, and eight accessions exhibiting single, double, and triple resistance to viruses, respectively. These findings have great potential for accelerating the development of antiviral germplasms and cultivating new cultivars in Capsicum.

-

Key words:

- Pepper /

- Viral disease /

- Mixed infection /

- Antiviral germplasm /

- Molecular assisted selection