-

Water security has become paramount for global sustainable development. The United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda (SDG 6) highlights the critical status of global water resources, with Target 6 specifically addressing 'clean water and sanitation'[1]. Recent monitoring data reveal alarming trends: 40% of water bodies across 89 surveyed countries exhibit severe pollution, directly compromising drinking water safety for nearly three billion people[2]. Projections suggest this crisis may intensify, with the global water supply-demand gap potentially reaching 40% by 2030 without effective intervention[3]. China's decade-long efforts in water environment governance have yielded measurable improvements in surface water quality, as documented in the 'China Ecological Environment Status Bulletin' (2012–2022)[4]. However, persistent challenges remain, including deteriorating groundwater and coastal marine ecosystems, alongside an increase in the frequency of detecting emerging contaminants in drinking water supplies. The 2024 UN World Water Development Report underscores the geopolitical dimensions of water scarcity, identifying it as an emerging catalyst for international conflicts and advocating for enhanced transboundary cooperation in water resource management[5].

Reservoirs represent critical yet vulnerable components of water infrastructures, serving dual functions as engineered water storage systems and complex ecosystems[6]. Of the more than 58,000 large dams operating globally[7], many face mounting pressures from HM contamination—a priority concern due to metals' toxicity, bioaccumulation potential, and environmental persistence[8−10]. Climate change and anthropogenic activities have created complex pollution dynamics, where reservoir-specific hydrology mediates sediment-water interface processes that control metal speciation and bioavailability[11,12]. Ecological consequences are increasingly evident: HM concentrations in reservoir fish populations frequently exceed World Health Organization (WHO) safety thresholds, posing dietary exposure risks through trophic magnification[13−15]. Notably, structural similarities between reservoirs and tailings ponds have led to classification ambiguities in research contexts, despite their differing operational purposes. Both systems share a capacity for acute ecological damage, as demonstrated by the Xiannv Lake Reservoir incident, where HM release reduced sediment denitrifying bacteria abundance by 72%, severely disrupting microbial community structure and nitrogen cycling functions[16,17]. Similarly, the Rio Doce Dam failure revealed persistent ecosystem impacts, with dissolved HMs during high-flow periods correlating significantly with zooplankton community shifts toward metal-tolerant taxa five years post-collapse[18].

Contemporary research identifies secondary pollution from water infrastructure operations as an escalating concern[19]. While reservoirs may temporarily sequester pollutants[20,21], long-term risks persist, particularly in inter-basin transfer systems. Current understanding remains fragmented, with most studies examining individual projects rather than systemic interactions between water transfer networks and reservoir management[22−24]. This limitation stems partly from the conventional classification of reservoirs as lacustrine systems, despite fundamental differences in their formation, ecosystem dynamics, and vulnerability to anthropogenic impacts[25,26]. Comparative analyses highlight these distinctions: examination of more than 64,000 fish samples from 883 reservoirs and 1,387 lakes in western North America revealed that reservoir fish mercury (Hg) concentrations averaged 44% higher than those in lakes, with reservoir age showing phased influences—peaking at three years post-impoundment before declining, yet maintaining a 27% elevation long-term[27]. These mechanistic drivers explain this pattern: (1) enhanced methylmercury (MeHg) production during initial organic matter decomposition; (2) sediment exposure-submergence cycles from water-level management stimulating microbial activity; and (3) semi-enclosed hydrodynamics amplifying trophic transfer. These effects were particularly pronounced in arid regions and mining-impacted areas[28].

Current remediation technologies encounter considerable limitations. Although chemical methods, such as adsorption[29], ion exchange[30], and membrane separation[31], show partial effectiveness in removing HMs[32], they are often associated with high operational costs, secondary pollution, or limited efficiency. Emerging approaches based on nanomaterials and bioremediation offer promising potential but face substantial challenges in scalability for real-world applications[33−35]. This technological challenge is especially evident in complex water-energy-food-land (WEFL) coupled systems, as illustrated by the system archetype analysis of Indonesia's Jatiluhur Reservoir, where agricultural expansion, industrial development, and residential water demands together form a 'limits to growth' archetype[36]. Importantly, amid the rapid global expansion of hydropower projects, changes in watershed geochemical behavior due to dam construction and their associated ecological risks are becoming increasingly prominent scientific concerns[37]. Furthermore, existing risk assessment frameworks lack sufficient capacity to evaluate complex exposure scenarios, such as combined pollution and chronic low-dose exposure, further highlighting the pressing need for integrated and systematic solutions.

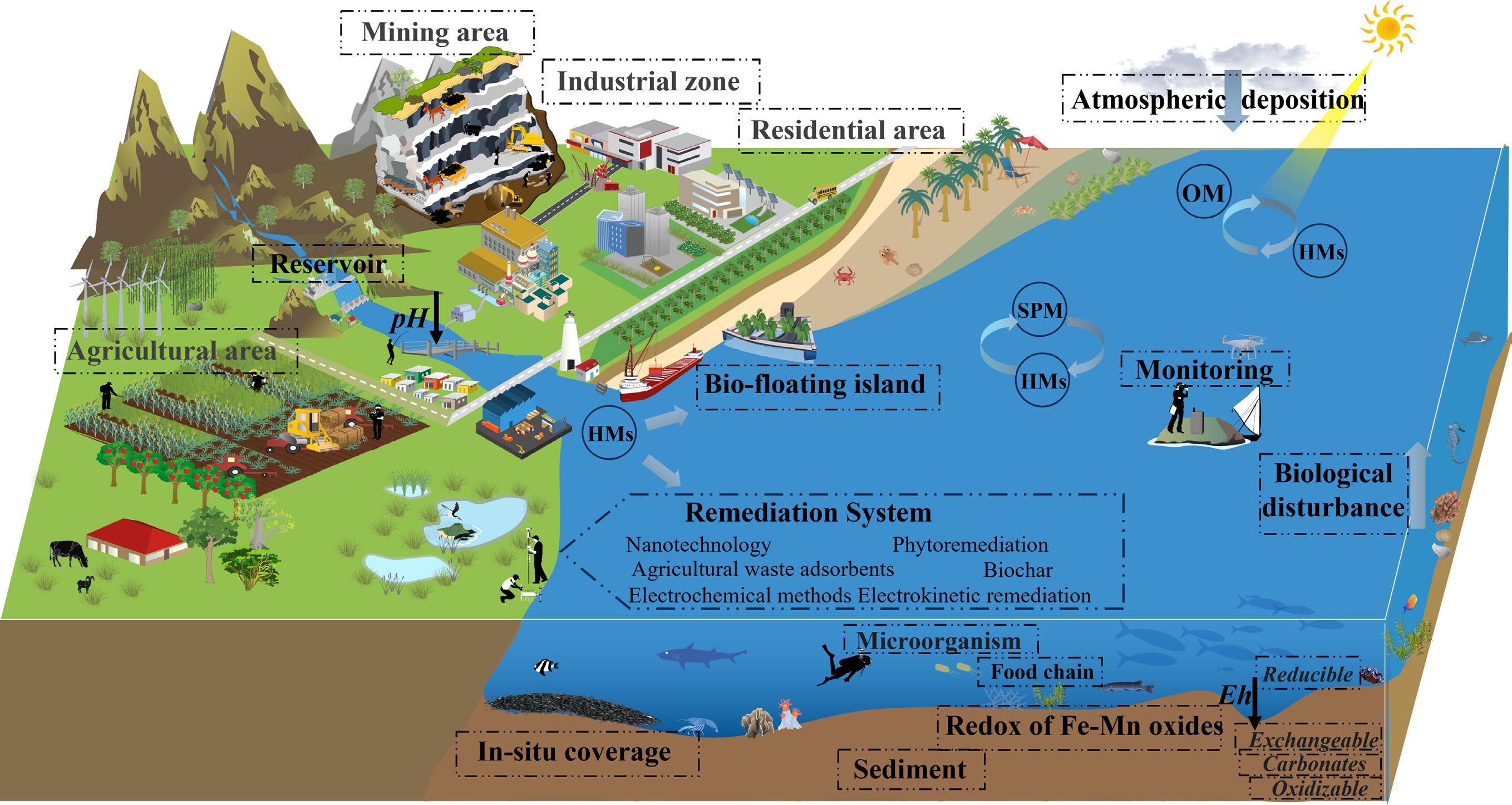

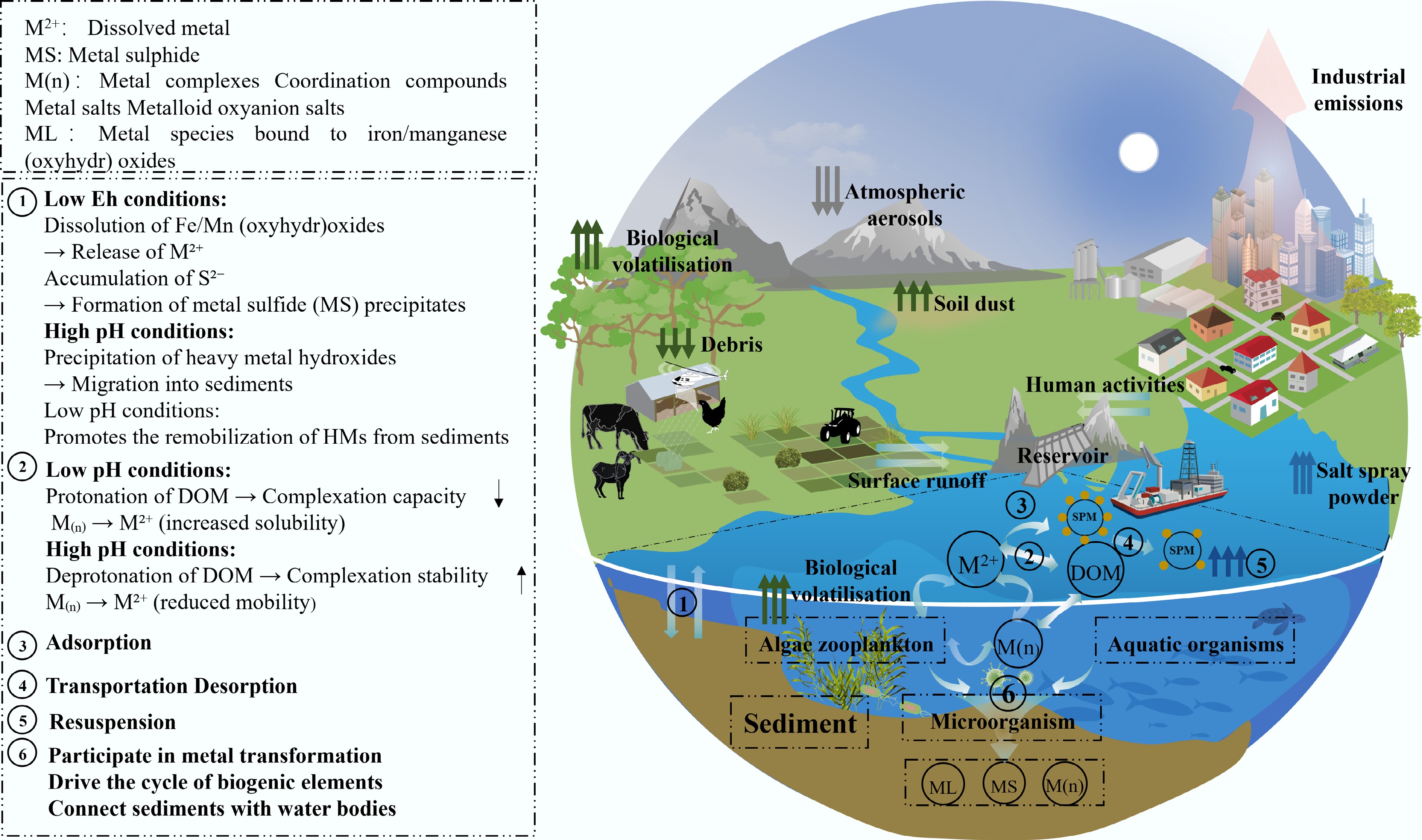

This interdisciplinary review integrates multi-source environmental data to systematically examine HM pollution in reservoirs through four analytical perspectives. To visually synthesize the interdisciplinary exploration of HM pollution in reservoirs, Fig. 1 illustrates a comprehensive conceptual framework that corresponds to the four analytical perspectives of this review: (1) source identification and attribution; (2) interfacial processes and transformation mechanisms; (3) ecological impacts and risk assessment; and (4) emerging technologies and green materials development. By synthesizing emerging monitoring technologies with innovative remediation strategies, this work provides a scientific basis and strategic reference for future in-depth research on HM pollution mechanisms, promotion of intelligent monitoring and green remediation technologies, and establishment of a unified and standardized technical standard system. This study aims to contribute to the development of sustainable management frameworks for reservoir ecosystems.

-

Reservoirs serve as essential infrastructure for freshwater storage, with water quality being a critical factor influencing both watershed ecological integrity and public health safety. Current research highlights that HMs in reservoir ecosystems display complex multi-media interfacial behaviors and significant ecological accumulation effects[38]. Three primary source pathways of HM in reservoir water bodies have been systematically identified: (1) point-source discharges originating from discrete emission sites; (2) non-point-source transport via diffuse surface runoff in agricultural regions; and (3) endogenous remobilization through redox cycling at the sediment-water interface. These distinct pollution sources exhibit regional variability while collectively shaping the spatial distribution and speciation of HMs by dynamically interacting with hydrodynamic conditions and biogeochemical processes[39].

HM contamination in aquatic systems compromises water quality, accumulates in sediments, and propagates through trophic levels via biomagnification, ultimately posing significant risks to human health[40]. Therefore, understanding the source contributions of diverse pollutants is critical for providing a scientific foundation to effectively manage reservoir water security.

Pollution source identification

Point-source pollution

-

Mining activities and industrial wastewater discharge represent two primary pathways of point-source pollution, characterized by notable spatial variability and long-term persistence[41,42]. Acid mine drainage (AMD), which originates from mine tailings ponds, is defined by its low pH levels and the presence of various dissolved HMs, making it a focal point of extensive research due to its distinct physicochemical properties[43]. Globally, approximately 18,000 tailings ponds have been constructed for storing metal and non-metal mining waste, with major mining nations confronting substantial AMD-related environmental challenges. The impacts of AMD on aquatic ecosystems can persist long after mining operations have ceased[44,45]. In recent decades, numerous countries have reported incidents of tailings ponds leakage, leading to severe ecological or environmental damage and, in some cases, loss of life[46]. A study by Techane et al. on the Legadembi gold mine tailings dam revealed that sulfide oxidation promotes the acidic dissolution of HMs, while downstream soils facilitate the migration of arsenic and tungsten via anion exchange processes[47]. Similarly, Wu et al., through the analysis of sediment cores from the Miyun Reservoir, identified a significant correlation between the enrichment levels of nickel and other HMs over the past two decades and the intensity of upstream mining activities[48].

Despite the widespread implementation of stringent environmental regulations (e.g., the EU IED Directive and China's GB8978-1996) and the active promotion of clean production technologies, legacy pollution in early industrial zones and the continuous emergence of novel pollutants have emerged as significant new environmental challenges[49]. For instance, Tytła et al. reported that sediments from the Dzierżno Duże Reservoir exhibited high to extremely high concentrations of multiple HMs, with industrial activities contributing up to 70% of the contamination[50]. Likewise, Chassiot et al. reconstructed a 50-year pollution history in the Saint-Charles River Reservoir, demonstrating that industrial discharges led to persistent HM accumulation in downstream sediments, thereby triggering ecological degradation[51].

Non-point source pollution

-

Non-point source (NPS) pollution exhibits significant spatial heterogeneity and complex transport mechanisms, characterized by dispersed emission sources and interconnected migration pathways[52]. Among various pollution sources, agricultural activities are the dominant contributor to NPS pollution, accounting for the largest proportion[53]. For example, sediment core analyses from India's Darna and Gangapur reservoirs in Nashik revealed distinct vertical HM distribution patterns that correspond chronologically to phases of agricultural development[54]. The Igboho Dam Reservoir provides direct evidence, where abnormally high concentrations of metallic elements in sediments were primarily linked to the long-term overuse of agrochemicals and organic fertilizers in adjacent farmlands[55]. Monitoring data from reservoirs in southeastern Brazil further indicate that HM pollution in areas affected by agricultural practices typically reaches moderate to severe contamination levels[56]. This pollution pressure propagates through the food chain, inducing cascading effects that significantly influence aquatic community structures. Australian studies demonstrated a statistically significant correlation (p < 0.05) between changes in benthic community composition in reservoirs and sediment HM concentrations, indicating that environmental stress caused by agricultural activities substantially alters the community succession patterns of reservoir ecosystems[57]. In addition to agricultural activities, atmospheric deposition represents another critical pathway for HM input into reservoirs. Elevated concentrations of HMs in sediments and algae from Fryanov Reservoir and Nové Mlýny Reservoir have been predominantly attributed to atmospheric deposition[58]. In addition, an analysis of a typical legacy pyrite mining area in the lower reaches of the Yangtze River found that heavy metals input from atmospheric deposition can enter reservoirs through pathways such as surface runoff. On one hand, they may accumulate in slow-flow areas like reservoir inlets alongside heavy metals from other sources, altering the spatial distribution of heavy metals in and around the reservoir. On the other hand, although their input flux is lower than that of active mining areas due to factors like the suspension of mining operations, they remain a significant source of heavy metals for the reservoir and the surrounding farmland soil[59].

Endogenous release

-

The internal release represents a significant contributor to HM pollution in reservoir water systems, driven by dynamic migration processes occurring at the sediment-water interface (SWI). Sediments act not only as a 'sink' but also as a potential 'source' of HMs and other pollutants under fluctuating environmental conditions[60]. These processes are primarily governed by three key mechanisms: (1) physical disturbance mechanisms, largely induced by human activities; (2) chemical transformation mechanisms, involving variations in parameters such as pH reduction and redox potential (Eh); and (3) biological mechanisms, including microbial metabolic activities and benthic bioturbation. The following sections will provide a comprehensive analysis of the impacts of HM pollution and the ecological risks associated with environmental changes at the SWI. Specifically, this section focuses on the pollution resulting from such changes. For example, studies conducted in the Keban Dam Reservoir demonstrated that the resuspension of surface sediments, along with the subsequent sedimentation of metal ions, resulted in concentrations of Cu, Zn, and barium (Ba) in deep water layers being two to three times higher than those in the epilimnetic waters[61]. Investigations into Sabalan Reservoir in Iran further revealed that sediments, acting as long-term accumulators of arsenic (As), continuously influence overlying water via interfacial diffusion, thereby posing significant environmental hazards[62]. This phenomenon is closely associated with reductive release processes at the SWI, particularly the critical role of iron-manganese reduction (IMR) in facilitating HM ion exchange. Taking the eutrophic area of Hongfeng Reservoir as a case study, the biogeochemical processes at the SWI exhibit typical characteristics of HM migration and transformation. Research data demonstrate that the reducing environment mediated by sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) generates S2−, which competes with PO43− for adsorption sites, thereby inducing the desorption of arsenate (HAsO42−/H2AsO4−). Simultaneously, the formation of FeS and ZnS precipitates results in negative fluxes of Cd and Zn[63]. Additionally, studies reveal that environmental resistance exerts minimal influence on this process. Regardless of seasonal variations such as dry-wet alternation or off-season regulation, the IMR cycle persistently drives arsenic release, establishing a continuous pollution pathway that is challenging to interrupt[64,65].

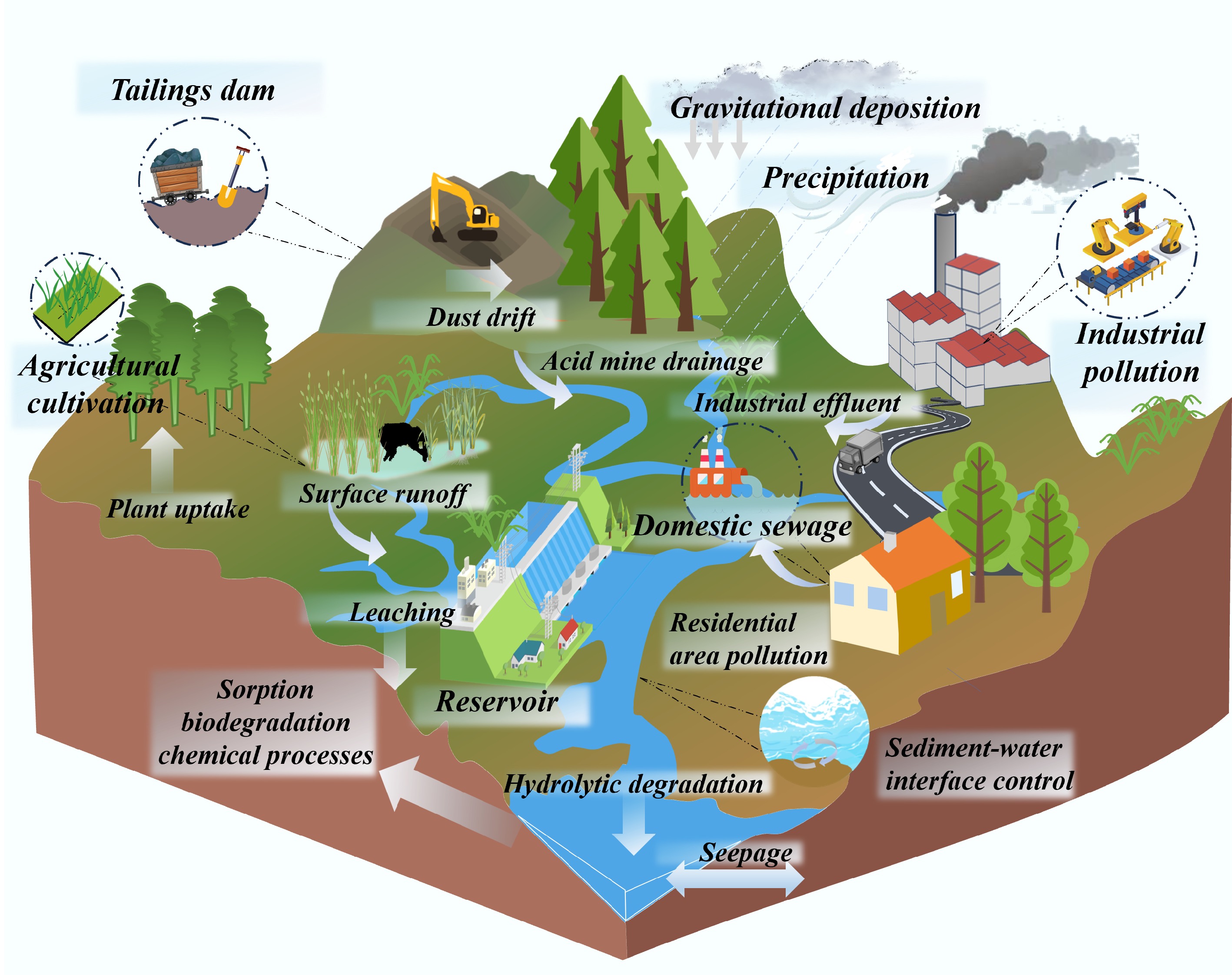

As depicted in Fig. 2, the multidimensional coupling mechanism of HM pollution in reservoirs demonstrates that real-world pollution processes are characterized by complex, networked interactions. The diagram identifies five major sources of HM pollution, which stem from both anthropogenic activities and natural processes contributing to reservoir contamination. Agricultural activities involving the use of fertilizers and pesticides, as well as soil erosion, facilitate the input of HM into reservoirs through surface runoff. Mining tailings, when subjected to rainwater erosion, can leach HMs into adjacent water bodies, which ultimately flow into reservoirs. Industrial emissions, such as exhaust gases and dust, lead to deposition—a phenomenon known as cross-media pollution. In addition, factories introduce HMs into reservoir watersheds either directly or indirectly via wastewater discharge, gaseous emissions, and solid waste disposal. Similarly, domestic and industrial sewage, whether discharged directly or insufficiently treated, also serves as a significant source of HM input into reservoir systems. Reservoir sediments serve as both a sink and a source of HMs. Under fluctuating environmental conditions, previously adsorbed HMs can re-release into the water column, contributing to what is known as 'internal pollution'. Microbially and plant-mediated processes further facilitate transformations of HMs (e.g., oxidation/reduction, complexation), thereby affecting their toxicity and mobility—an intricate process often referred to as the 'hidden cycle'. The biogeochemical cycling of HMs will be discussed in detail in the following section. Rivers function as conveyor belts, transporting HMs from diverse pollution sources within the watershed into reservoirs, acting as a key mechanism for pollution dispersion. Importantly, HM pollution does not simply result from linear accumulation originating from a single source; rather, it forms a three-dimensional network shaped by the interaction of multiple interfacial processes[66]. Given the complexity of geological environments and spatial structures, contamination originating from tailings ponds often remains concealed. Conventional investigation methods are labor-intensive, costly, and inadequate for providing detailed spatial distribution data[67,68]. Moreover, NPS pollution frequently induces delayed impacts on the environmental quality of receiving water bodies. For instance, when pollution levels exceed environmental capacity, eutrophication-induced hypoxia fundamentally alters the dynamics of the SWI: depletion of dissolved oxygen triggers IMR-mediated reductive dissolution, releasing previously immobilized HMs and converting them into bioavailable forms. This process, facilitated by benthic uptake and food chain transfer, perpetuates a vicious cycle[69]. The situation becomes even more complex under concurrent eutrophication and HM pollution, as the coupling of sulfur and carbon cycles modifies metal migration and transformation pathways. These multiple feedback mechanisms render traditional single-pollution control strategies largely ineffective, thus highlighting the urgent need to develop an integrated reservoir pollution management system based on the theory of multiprocess coupling.

Hydrogeochemical processes

-

The behavior of HMs in reservoir ecosystems involves a dynamic, multi-phase coupled process primarily driven by hydrogeochemical mechanisms that govern their migration and transformation. This process exhibits three-dimensional complexity: vertical stratification creates a pollution gradient layer transitioning from oxidized conditions in surface sediments to reduced states in deeper layers, while horizontal heterogeneity leads to pollution hotspots whose spatial distribution is shaped by hydrodynamic conditions, watershed characteristics, and biogeochemical cycles. The inherent complexity of this process results in considerable spatial heterogeneity and temporal variability[70−73]. A thorough understanding of these multi-phase coupling mechanisms is crucial for accurately predicting the environmental fate of HMs, assessing ecological risks, and developing targeted remediation technologies. Moreover, such insights form the theoretical foundation for the sustainable management of reservoir ecosystems.

Key regulatory role of pH

-

pH serves as a critical regulatory parameter in aquatic environmental chemistry, exerting substantial influence over the geochemical behavior of HMs through multiple mechanistic pathways[74]. As a master variable governing HM mobility within soil-sediment-water systems, pH regulates migration and transformation processes via complex chemical equilibria and interfacial reactions. Under acidic conditions (pH < 7), HM mobility is markedly enhanced through three primary mechanisms: (1) mobilization of exchangeable and carbonate-bound fractions (e.g., Cd, Zn, Cu, Pb) due to weakened sediment binding; (2) dissolution of IMR, releasing adsorbed Cr3+ and Ni2+; and (3) reduction of As5+ to the more toxic As3+ species[75−77]. Conversely, alkaline conditions (pH > 7) induce fundamentally different behaviors: (1) precipitation of Cd, Zn, Cu, and Pb as hydroxides, promoting speciation shifts toward oxidized and residual forms with reduced bioavailability; (2) stabilization of IMR, thereby immobilizing Cr3+ and Ni2+; and (3) oxidation of As3+ to the less toxic As5+, which subsequently adsorbs onto IMR or forms stable complexes[78−83]. Extensive reservoir studies consistently confirm the essential role of pH in regulating HM bioavailability, chemical speciation, and associated ecological risks. This pH-dependent dichotomy fundamentally governs HM fate in aquatic ecosystems, carrying significant implications for the development of effective pollution control strategies and risk assessment frameworks.

The influence of redox potential

-

As a master variable governing the environmental behavior of variable-valence HMs, Eh plays a pivotal role in species transformation and migration dynamics by regulating electron transfer processes. This redox-dependent behavior exhibits distinct stratification: (1) under oxidizing conditions (Eh > 300 mV), IMR effectively immobilizes HM ions through surface complexation and coprecipitation mechanisms; whereas (2) in reducing conditions (Eh < 100 mV), microbial-mediated reductive dissolution becomes the dominant process controlling HM release and transformation. The water-level fluctuation zones of reservoir banks represent a critical aquatic-terrestrial interface exhibiting pronounced spatiotemporal Eh heterogeneity due to periodic variations in water levels[84]. The Eh-dependent behavior of arsenic speciation exemplifies this pattern: As5+ dominates in highly oxidizing conditions (Eh > 450 mV), while at intermediate redox states (Eh = –100 to +100 mV), the microbial reductive dissolution of iron oxides releases adsorbed As5+ and promotes its conversion into the more toxic and mobile As3+ species[85,86]. Seasonally anoxic reservoir sediments typically develop strongly reducing microenvironments (Eh < 0 mV), where SRB play a dominant role in controlling the fate of HM[87]. Through dissimilatory sulfate reduction, SRB produce S2− that reacts with HM ions to form insoluble sulfide precipitates. Field observations from the Águas Claras Reservoir demonstrate that the coupling of low Eh and high SRB activity significantly reduces dissolved HM concentrations[88]. However, this Eh-HM relationship can exhibit nonlinear behavior in specific environments such as AMD systems, where sulfide oxidation rapidly consumes dissolved oxygen, leading to abrupt declines in Eh that unexpectedly promote HM mobilization[89]. These findings highlight the complex redox-driven mechanisms governing HM biogeochemical cycling in reservoir sediments.

Effects of organic matter

-

Organic matter (OM) also plays a critical role in modulating the environmental behavior of HMs through complexation processes. The OM pool in reservoirs consists of both macromolecular humic substances derived from terrestrial sources and low-molecular-weight compounds originating from autochthonous production, forming a dynamic system whose transformation pathways are further influenced by hydraulic retention[90−93]. Three principal mechanisms govern OM-HM interactions: (1) molecular complexation—dissolved organic matter (DOM), particularly humic acids (HA), forms stable complexes with HMs via oxygen-containing functional groups. While this process can enhance HM bioavailability, it may also reduce their mobility through the formation of macromolecular complexes, as evidenced by multiple reservoir studies[94−96]; (2) colloidal transport—organic-inorganic composite colloids possess a high specific surface area and surface reactivity, enabling effective adsorption of HMs and altering their migration patterns. Tracking after the Fundão Dam incident revealed that tailings-derived colloids decreased HM distribution coefficients by 40%–60% through solubilization[97]. Similarly, colloidal Cd accounted for 35%–40% of total Cd transport flux in Miyun Reservoir[98]; and (3) microbial mediation—OM indirectly influences HM biogeochemical cycling by shaping metal-resistant microbial communities, which constitutes a key mechanism in the self-remediation of a contaminated ecosystem[99]. In early studies, OM had not yet emerged as a central research focus in relation to its influence on HM behavior in reservoir bottom sediments. Research investigating the correlation mechanisms between the varying sources and compositions of OM and HM migration and transformation remains limited. Future studies should aim to elucidate the quantitative relationships between the molecular characteristics of OM and HM speciation transformation, as well as assess the relative contributions of OM from different sources in the HM multi-media migration processes. Such efforts would contribute to a more robust scientific theoretical foundation for the risk management of reservoir ecosystems.

As core geochemical parameters in reservoir environments, pH and Eh govern the speciation transformation and environmental fate of HMs through complex synergistic mechanisms. OM, acting as a critical ecological medium, further influences HM bioavailability via processes such as complexation, reduction, and competitive adsorption. Under oxidizing conditions, DOM such as fulvic acid forms stable complexes with HMs, thereby enhancing their mobility. Conversely, under reducing conditions, anaerobic OM degradation consumes electron acceptors (e.g., Fe3+, SO42−), which promotes HM release while simultaneously facilitating sulfide production (e.g., by SRB metabolism) or the formation of organo-metal precipitates that influence immobilization efficiency. The dynamic interactions among these key factors—pH, Eh, and OM—collectively form a comprehensive framework for assessing HM pollution risks in reservoir systems.

Biogeochemical cycles

-

The biogeochemical cycle provides a fundamental framework for understanding the dynamic processes of HM pollution in reservoir ecosystems, where microbial communities and suspended particulate matter (SPM) play pivotal roles. Microbial metabolic activities drive changes in HM speciation through redox reactions, OM decomposition, and biomineralization processes. At the same time, SPM functions as a critical intermediary in aquatic environments, facilitating horizontal HM transport via hydrodynamic processes, vertical flux through sedimentation and resuspension cycles, and trophic transfer via bioaccumulation. The complex interactions between microbial communities and SPM underscore their importance not only for advancing scientific research but also for informing effective management strategies in reservoir systems[100−104].

Microbial-mediated morphological transformation

-

In water reservoirs, microbial adaptive mechanisms are essential for maintaining ecosystem stability and functionality. The increasing application of metagenomic technologies has provided powerful tools to investigate these mechanisms. Aquatic microbial community diversity strongly influences the expression of potential metagenomic functions, thereby regulating microbial responses to environmental changes[105]. For instance, studies have demonstrated that denitrifying bacteria contribute to MeHg production via the expression of the mercury methyltransferase A gene (hgcA) in surface waters of Brownlee Reservoir under nitrate-reducing conditions[106]. Additionally, Zhang et al. utilized metagenomics to identify Cu resistance genes and As resistance genes as dominant metal resistance genes (MRGs) in sediments from ten reservoirs in Central China, where MRGs dynamics are directly shaped by HM concentrations[107].

Metagenomic studies have revealed the molecular strategies employed by microorganisms to withstand HM stress, including the regulated expression of metal resistance genes and the reorganization of microbial community structures. In parallel, bioturbation and bioaccumulation processes in aquatic ecosystems contribute to the secondary release of HMs from sediments into organisms, playing critical roles in the biogeochemical cycling of HMs[108,109]. Field investigations at Toledo Bend Reservoir have demonstrated that benthic bioturbation can significantly alter the interfacial migration flux of Pb, with the extent of this influence being modulated by sediment properties, such as pH and OM content[110]. Similarly, studies on Castilseras Reservoir have confirmed the environmental risk associated with Hg transfer from bottom sediments to aquatic food webs, leading to elevated Hg concentrations in organisms at higher trophic levels[111]. MRGs primarily enable bacterial tolerance to HM toxicity through mechanisms such as efflux pumps, enzyme-mediated transport, and intracellular chelation of HMs. The environmental migration and transformation of MRGs have increasingly become focal points in environmental and ecological research in recent years. Collectively, these findings offer valuable insights into the assessment of environmental risks posed by HM pollution within reservoir ecosystems.

Role of SPM in HM transport and retention

-

SPM in aquatic systems serves as a key medium for the transport of HM, due to its large specific surface area and abundant reactive sites, which significantly influence contaminant dynamics via interfacial adsorption[112]. However, the HM retention capacity of SPM varies considerably across different reservoirs. For example, in Parker Dam, although SPM exhibits high HM concentrations, the dominance of quartz (accounting for more than 70% of its composition) limits surface reactivity, thereby reducing the overall pollution risk[113]. Conversely, in the Borçka Dam Reservoir affected by AMD, iron- and manganese-rich suspended particles contribute to over 85% of the adsorption flux of Cu and Zn, markedly increasing the risk of secondary pollution during sediment resuspension[114]. The adsorption of HMs onto SPM generally follows kinetic models that describe the equilibrium between HM species bound to particles and those in the dissolved phase, while also capturing concentration-dependent adsorption capacities and mechanistic insights into HM transport. Recent advances in modeling have uncovered system-specific behaviors; for instance, the enhanced CE-QUAL-W2 model combined with a two-dimensional laterally averaged model was applied to simulate Pb transport in the Shahid Rajaei Dam Reservoir, revealing temperature-dependent transformation processes of Pb[115]. Studies on the Three Gorges Dam illustrate that its operation has gradually diminished both SPM and the fraction of fine particles in the Yangtze Estuary, consequently lowering the resuspension potential of Pb and Cr[116].

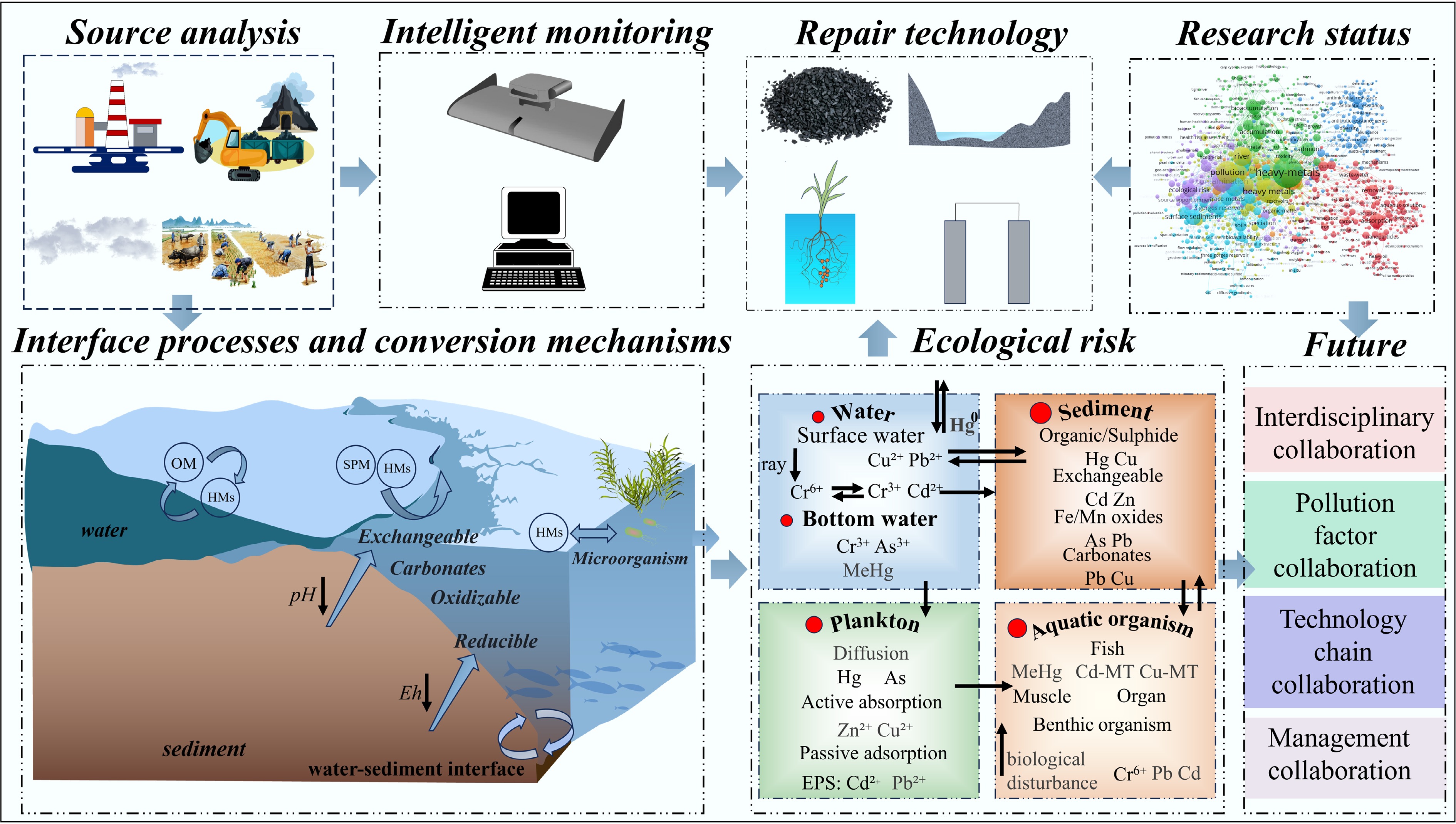

As schematically illustrated in Fig. 3, the multi-scale interactions between hydrogeochemical parameters (pH, Eh), biogeochemical components (OM, SPM), and microbial processes are systematically integrated to depict the dynamic behavior of HMs in reservoir ecosystems. These processes are primarily regulated by three key mechanisms: (1) pH-dependent dissolution-precipitation equilibria that influence HM bioavailability; (2) redox transformations driven by Eh, which affect elements like As, Fe, and Hg; and (3) OM-mediated speciation through complexation, colloid-assisted transport, and microbial interactions. Importantly, SRB-driven Hg methylation and SPM-mediated adsorption-desorption cycles contribute significantly to the dynamic flux network of HMs across the sediment-water-biota continuum. While these individual mechanisms are increasingly understood, critical knowledge gaps persist regarding the nonlinear synergistic interactions within pH-Eh-OM ternary systems, the quantitative relationships between microbial functional genes (e.g., hgcA) and HM speciation, and the impacts of climate change on SPM resuspension thresholds. To tackle these challenges, strategic research priorities involve developing advanced risk modeling frameworks that integrate multi-media (water-sediment-biota) HM speciation data with bioavailability algorithms to enable real-time warning systems. Additionally, engineering functional materials, such as sulfur-modified biochar and nanocomposites, are being designed to target key processes, including methylation inhibition and sulfide stabilization. The following sections provide a comprehensive evaluation of ecological risk quantification methodologies and emerging remediation technologies, offering both theoretical support and practical technical pathways for the sustainable management of HM pollution in reservoirs.

-

In recent years, substantial advancements have been made in the development of ecological risk assessment methods for HM pollution in reservoirs. Internationally, models based on multi-species toxicity data have become the predominant approach. These models quantify the relationship between pollutant concentrations and ecological effects by incorporating the varying sensitivities of organisms across different trophic levels. Among them, the Species Sensitivity Distribution (SSD) model is the most widely used. It assumes that species sensitivity follows certain statistical distributions (e.g., log-normal or logistic distributions) to determine threshold concentrations that safeguard a specified proportion of species. The construction of SSD models typically involves selecting ecologically representative test species from multiple trophic levels (producers, consumers, and decomposers), acquiring reliable toxicity data via standardized testing procedures, estimating model parameters using appropriate statistical techniques (e.g., maximum likelihood estimation), and assessing prediction reliability through uncertainty analysis[117]. Despite their widespread use, SSD models face limitations, such as insufficient taxonomic representativeness of test species and uncertainties in extrapolating laboratory-derived thresholds to field conditions[118,119]. To address these challenges, researchers have increasingly adopted Bayesian correlation models to enhance the accuracy of risk assessment and support evidence-based decision-making[120]. Critical indicators in ecological risk assessment include key thresholds such as the Hazardous Concentration for 5% of species (HC5) and the Hazardous Concentration for 50% of species (HC50), which reflect the sensitivity of organisms to pollutants. For instance, a study employing a modified SSD model across eight reservoirs in the lower Yellow River found significant differences in sensitivity between vertebrates and invertebrates under varying HM concentrations. Ni and Cd exhibited the lowest chronic risk thresholds, while Antimony (Sb) showed the highest; Cu already reached relatively high levels of chronic ecological risk[121]. Another study utilized SSD-based risk quotient (RQSSD) and joint probability curve (JPC) methods to evaluate ecological risks from 13 metal elements in reservoirs along Mexico's Atoyac River. The results from both the JPC and RQSSD methods confirmed that biological communities in the watershed are subjected to multiple metal-induced stressors[122]. SSD models and their improved methodologies have been extensively applied in surface water environmental monitoring, water quality assessment, and pollution identification, offering efficient and accurate detection capabilities that provide strong technical support for surface water research. However, the application of SSD models in reservoir environmental monitoring remains at an early stage. Future integration of SSD models with complementary approaches, as well as further development of their use in identifying reservoir pollution and assessing health risks, presents considerable potential for advancement. Table 1 summarizes the commonly used risk assessment models and health evaluation methods in current research, highlighting how these technological innovations provide more accurate tools for managing health risks associated with HMs in reservoir environments.

Table 1. Common risk assessment models and applications in reservoir-HMs research

N Model name Formula Parameter annotation Application scenario Potential ecological risk index (PERI) Eri = Tri × Ci/$ C_b^{i} $ Tri: Toxicity coefficient; Ci /$ C_b^{i} $: pollutant concentration/background value Sediment ecological risk assessment Comprehensive potential ecological risk index (RI) RI = ∑$ E_r^{i} $ $ E_r^{i} $: Ecological risk index for single pollutant Ecological risk assessment of multi-pollutant synergy Bioaccumulation factor (BAF) BAF = Cbiota / Cwater Cbiota: HM concentration in fish/shellfish Cwater: Aqueous concentration Assessment of enrichment effects in aquatic organisms Cwater Fish/shellfish Cwater: Aqueous concentration enrichment effects in aquatic organisms Target hazard quotient (THQ) $ THQ=\dfrac{EF\,\times \,ED\, \times \,FIR\,\times\, C}{RfD\,\times \,BW\,\times\, AT} $ EF: Exposure frequency (d/year); FIR: Ingestion rate (g/day); RfD: Reference dose (mg/kg·d); ED: Exposure duration (years); BW: Body weight (kg); AT: Averaging time (d) Health risk assessment of drinking water/aquatic products Lifetime cancer risk (LCR) LCR = SF × ADD SF: Slope factor (mg/kg·d) ADD: Average daily intake (based on water concentration and ingestion), (mg/kg·d) Long-term risk assessment of carcinogenic HMs Health risk assessment

-

Health risk assessment is essential for managing HM pollution in reservoirs, aiming to quantify potential health hazards from pollutants via multiple exposure pathways. The current mainstream approach relies on evaluation models recommended by the US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) to assess both carcinogens and non-carcinogen risks[123,124]. Recent methodological advancements have improved the reliability of these assessments by incorporating Monte Carlo (MC) simulation techniques. MC simulations enhance uncertainty quantification by constructing probabilistic analysis models that convert key parameters, such as HM concentrations and exposure frequency, into probability distributions[125,126]. For example, MC-based analysis of a reservoir water source revealed that arsenic concentration (contributing 73.5%) and drinking water intake rate (19.1%) are the primary contributors to carcinogenic risks[127]. A Monte Carlo assessment of five urban reservoirs in Iran identified Pb contamination in the Ardakan Reservoir and Ni contamination in the Meibod and Bahabad Reservoirs[128]. A notable advancement involves combining positive matrix factorization (PMF) with MC techniques. Studies in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area have demonstrated the effectiveness of this integrated approach in identifying pollution sources and predicting spatial risk patterns[129]. Importantly, this methodology has also demonstrated significant utility in evaluating sudden environmental incidents, as illustrated by studies following a tailings dam failure in Serbia. PMF source apportionment analysis confirmed that tailings materials were the dominant pollution source, contributing over 70%, with the highest contamination levels detected within a few kilometers downstream[130].

Intelligent monitoring and early warning system

-

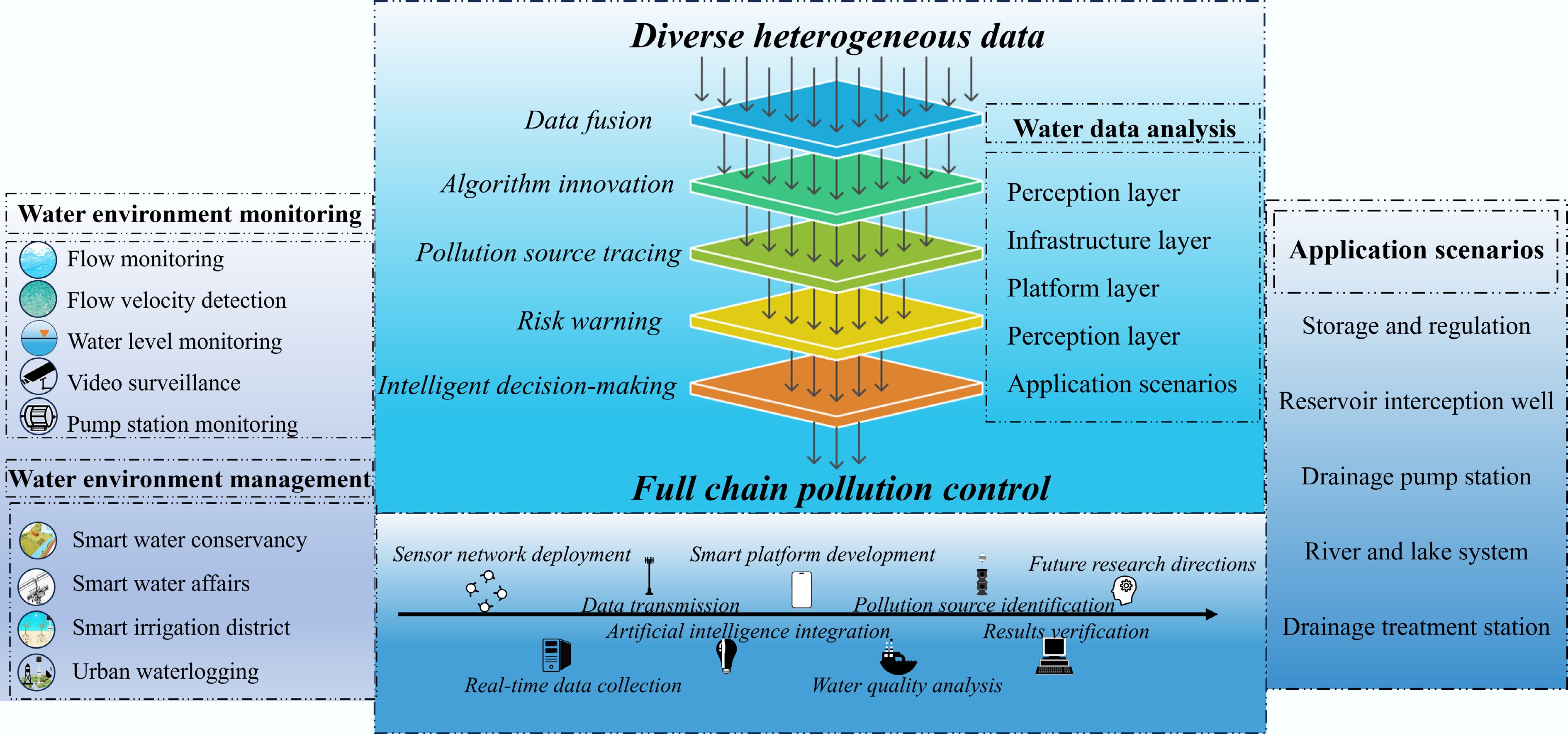

Assessing and monitoring potentially toxic HMs and metalloids across various ecological compartments and resident biological communities is critical for environmental protection[131]. Intelligent monitoring and early warning systems have become indispensable for preventing and controlling HM pollution in aquatic ecosystems. These advanced systems integrate high-precision sensor networks, Internet of Things (IoT)-based data transmission infrastructure, cloud computing analytics, and AI-powered predictive modeling to establish a comprehensive technological framework that covers the entire process from pollution detection to risk mitigation. By enabling real-time dynamic tracking of HM contamination, these systems promote a paradigm shift in pollution management strategies, transitioning from reactive remediation to proactive prevention through predictive modeling of contamination trends and data-driven decision support. The implementation of such integrated systems has significantly enhanced the scientific rigor and intelligent management capabilities of water environment governance, achieving minute-level response times to pollution events. Finally, a smart water environment management system that integrates monitoring, analysis, management, and application has been established, as shown in Fig. 4. This technological advancement marks a significant step toward safeguarding aquatic ecosystems and public health against HM contamination.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the full-chain technical architecture for smart water environment management.

Sensor networks and IoT real-time monitoring

-

The dynamic and complex nature of water environmental pollution necessitates the ongoing development and refinement of innovative sensing technologies to ensure accurate monitoring and effective risk assessment of HM pollution. Currently, mainstream sensing technologies can be broadly categorized into four types: optical sensors, electrochemical sensors, biosensors, and nanosensors. While optical sensors offer high sensitivity, their application in water monitoring remains limited due to factors such as high cost and susceptibility to environmental conditions[132]. Traditional electrochemical sensors, which have long served as primary tools for water environment monitoring, are being enhanced through the integration of sustainable materials and low-pollution manufacturing processes to improve their environmental compatibility[133]. Meanwhile, biosensors and nanosensors, known for their environmental friendliness and high specificity, have emerged as research hotspots in HM pollution monitoring[134]. In the field of biosensing technology, Ademola Adekunle's team innovatively employed microbial fuel cells to construct biosensors, enabling real-time monitoring of toxicity in mine drainage. Their research revealed a strong correlation between changes in microbial community composition within the sensors and HM exposure levels, with detection results showing high consistency (R2 = 0.92) when compared to traditional Microtox toxicity tests, thus confirming the reliability of this technology in addressing HM pollution[135]. Advances in nanosensing technology have created new possibilities for water quality monitoring. Researchers have developed a smart sensor capable of detecting multiple HMs by modifying carbon wire electrodes with gold nanoparticles. This innovation presents three key advantages: (1) the use of cost-effective carbon-based electrode materials combined with recycled plastic substrates, which supports resource sustainability; (2) strong pH adaptability and resistance to ion interference; and (3) the ability to simultaneously detect multiple HMs, including Cd2+, Pb2+, Cu2+, and Hg2+, with real-time data visualization achieved via an IoT platform[136]. The sensor has been effectively tested across various real-world water samples in India, showcasing its potential for practical applications. However, existing sensing technologies still encounter significant challenges in reservoir HM monitoring, such as limited field application, material performance constraints, and inadequate adaptability to complex aquatic environments. Therefore, future research should focus on developing low-cost, environmentally friendly, and functionally integrated sensing systems. By enhancing monitoring efficiency through multi-technology integration, these systems can provide critical technical support for early warning of HM pollution risks in reservoirs.

As the core architecture of IoT technology, sensor networks enable the real-time collection and transmission of environmental parameters through distributed intelligent sensing nodes, offering notable advantages in water environment monitoring[137]. With the deep integration of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, innovative sensing systems have made groundbreaking advancements in monitoring HM ions in water bodies. For example, Pan et al. developed a smartphone-based edge computing platform that integrates portable sensing devices with IoT cloud services. This platform successfully enabled multi-parameter detection of HMs and intelligent identification of pollution sources across four typical industrial wastewater models, including electroplating, battery manufacturing, metallurgy, and pesticide wastewater. System tests demonstrated that the platform's detection results for real water samples were highly consistent with those obtained using traditional laboratory analysis methods, thereby providing an efficient technical solution for pollution traceability, environmental regulation, and water quality assessment[138]. Similarly, Muhammad-Aree & Teepoo developed a cost-effective and field-deployable paper-based HM detection strip integrated with a smartphone application. This system enables the rapid detection of HMs such as Zn, Cr, Cu, Pb, and Manganese (Mn) in wastewater samples within 1 min, with results closely aligning with those obtained through laboratory analysis[139]. While these technological innovations offer promising solutions for monitoring HMs in reservoirs, large-scale engineering applications remain challenging and require further advancements in material performance, device stability, and system reliability. Therefore, future research should prioritize the development of intelligent and eco-friendly monitoring technologies to strengthen technical capabilities in safeguarding reservoir water quality.

Machine learning and algorithms

-

Machine learning technologies are revolutionizing research methodologies and practical applications in the prevention and control of HM pollution in aquatic environments. Through multi-source heterogeneous data fusion and innovative intelligent algorithms, a comprehensive technical framework has been established, spanning from pollution source tracing to risk early warning[140,141]. Current mainstream algorithm systems, including neural networks, random forests, support vector machines, and Bayesian networks, exhibit exceptional performance in identifying pollution sources and assessing environmental risks[142]. For example, decision tree algorithms achieved a 99.6% accuracy rate in a study conducted at Rawal Dam[143]. In another study on HM pollution in the Yangtze River Estuary, the random forest model demonstrated strong predictive performance for Pb, with the average R value of the test set reaching 0.90 and root mean square error (RMSE) as low as 0.16 for predicting Pb concentrations in water samples[144]. Recent advancements have introduced a spatiotemporal correlation prediction model that integrates spatial clustering features with stacked Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. Based on data from 31 copper mine sites, the stacked LSTM model correctly classified 83.87% of the sites into medium- to high-risk categories. Moreover, its predicted spatial distribution of pollution risk was highly consistent with the actual distribution of mine sites, significantly improving the reliability of HM pollution risk assessment[145]. Deep learning technology has further overcome the limitations of traditional analytical methods, enabling precise identification of latent patterns within complex sensor data. Moreover, it facilitates intelligent interpretation and visualization of monitoring results through integration with IoT platforms. Nevertheless, the speciation variability of HMs in reservoirs presents significant challenges to the widespread adoption of this technology, including issues related to algorithm adaptability, limitations in data quantity and quality, and complexities in system integration, particularly the need for enhanced generalization across reservoirs with varying functions. By focusing on multimodal data fusing, hybrid model optimization, and the development of intelligent decision-support systems, scholars can construct an integrated 'monitoring-early warning-governance' prevention and control framework. This strategy would effectively complement remediation technologies such as microbial remediation, offering more innovative and efficient solutions for managing HM pollution in reservoirs. Strengthening interdisciplinary collaboration between environmental science and computer science is essential for advancing technological innovation in reservoir pollution prevention. Additionally, because the effective implementation of machine learning technologies fundamentally relies on high-quality monitoring data, continuous improvements in sensor network deployment and data quality assurance mechanisms are critically important.

-

The evolution of nanotechnology has markedly enhanced the efficiency of HM removal, achieving critical advancements in selectivity, renewability, and environmental compatibility[146]. For instance, thiol-functionalized nanomaterials exhibit exceptional dual functionality for HM detection and removal. A notable case is mercaptosuccinic acid-thiosemicarbazide-based non-conjugated polymeric nanoparticles, which achieve an ultralow detection limit of 95 nM (19.0 μg/L) for Hg2+ with a linear range spanning four orders of magnitude (0.1–1,471 μM), and demonstrate a removal efficiency of 90.42% within 50 min. Furthermore, Na2S treatment allows this material to be regenerated for five reuse cycles while sustaining less than 5% performance loss per cycle[147]. In complex pollution systems, composite nanomaterials show particularly outstanding performance. Ahmed et al. synthesized a Zn ferrite/reduced graphene oxide (GO) composite using a modified Hummers method, achieving adsorption capacities of 89.8 mg/g for Pb2+ and 119.0 mg/g for organic dyes while maintaining over 90% removal efficiency after five cycles[148]. The GO-Zn oxide (GO-ZnO) nanocomposite integrates excellent adsorption performance with antibacterial functionality, demonstrating adsorption capacities of 121.95 mg/g for Cd2+ and 277.78 mg/g for Pb2+, along with reducing the size and number of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, demonstrating remarkable antibacterial activity[149]. Ji et al. synthesized a magnetic Fe3O4/GO nanocomposite by integrating solvothermal synthesis with pyrolysis techniques. This novel material preserves the original Metal-Organic Framework (MOF) morphology and crystalline structure while exhibiting strong anti-interference properties, thereby facilitating efficient As5+ adsorption over a broad pH range (2–9)[150]. Green synthesis approaches enhance the practical applicability of nanomaterials by mitigating environmental hazards and reducing economic costs[151]. Additionally, the 'waste-treats-waste' concept has gained recognition as an additional environmentally sustainable strategy, with representative examples summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Examples of nanotechnology in remediating HM-contaminated water bodies

Material Preparation process HMs Performance indicators Features/applications Ref. Fe3O4-CS Plant extract Pb2+ Pb2+: 98.39% Cyclic stability: after three cycles, the adsorption capacity retention rates were 95.81%, 70.65%, 50.50%, and 42.75%, respectively [152] Cu2+ Cu2+: 75.52% Cd2+ Cd2+: 51.54% Ni2+ Ni2+: 45.34 Lignin hybrid NPs Chemical cross-linking method Pb2+ Pb2+: 150.33 mg/g Reaches equilibrium within 30 s, suitable for actual reservoir water treatment [153] Cu2+ Cu2+: 70.69 mg/g Fe3O4/SiO2 Rosemary extract As3+ As3+: 49 mg/g Biological-nano synergistic system achieves simultaneous oxidation and removal of As3+ [154] rGO/Ag NPs Green tea reduction Pb2+ Pb2+: 84.2% In actual AMD treatment, the Pb2+ removal rate increased from 46.4% to 63.2% after five cycles (due to the in situ formation of iron oxide) [155] nFeS@GS Geobacter biohybrid Cu2+ Cu2+: 87.9% The recovery rate of heavy metals after sodium citrate desorption is > 90.7%, which is suitable for acidic mine wastewater [156] Pb2+ Pb2+: 96.2% Cd2+ Cd2+: 95.1% Fly ash-nZVI/Ni Waste-derived Cr6+ Cr6+: 48.31 mg/g The removal rate of Cr6+, Cu2+, etc. in actual industrial wastewater is > 87% [157] Cu2+ Cu2+: 147.06 mg/g MNPs-WSP Walnut shell coprecipitation Cd2+ Cd2+: 1.43 mg/g Recovery rates of 85%–98%, suitable for various water sources such as tap water and groundwater [158] Despite recent advancements, the large-scale application of nanomaterial-based remediation technologies for HM pollution faces three major challenges: (1) technical limitations persist, such as material instability in complex water matrices (e.g., magnetic nanoparticle aggregation, reduced conductivity of GO, and solubility issues in MOF), as well as inefficient regeneration processes[159]; (2) there remains insufficient understanding of environmental risks, particularly regarding the bioeffects, bioaccumulation, distribution patterns, metabolic pathways, and organ-specific toxicity mechanisms of green nanomaterials (GNMs), due to a lack of comprehensive data[160,161]; and (3) engineering barriers hinder the transition of laboratory-scale achievements to practical, real-world applications. To address these issues, future research should adopt a hierarchically structured methodology that integrates multi-scale strategies. At the molecular level, advanced in situ spectroscopic techniques should be utilized to elucidate interfacial interactions between pollutants and functional materials, while real-time monitoring technologies must be developed to characterize the dynamic process. In green material design, priority should be given to plant- and microbe-derived GNMs with dual functionality: high HM affinity (e.g., sulfur-modified biochar), and climate mitigation potential via carbon-negative production from agricultural waste. At the system scale, optimization requires the implementation of comprehensive life cycle assessment (LCA) frameworks to evaluate energy costs associated with GNM synthesis, long-term ecological impacts, and circular economy potential. Technologically, synergistic processes should be engineered by integrating nano-adsorption for primary capture, membrane separation for concentration, and electrochemical recovery for resource recycling, thereby establishing an integrated remediation system[162,163].

Agricultural waste adsorbents

-

In HM remediation, agricultural waste adsorbents have emerged as an innovative and increasingly promising technology[164]. The widespread availability of agricultural biomass provides significant potential for waste recycling and value-added utilization. Various agricultural biosorbents have been effectively applied to remove trace metals from wastewater, as summarized in Table 3, which presents commonly used agricultural waste adsorbents for HM contamination, highlighting their high-efficiency, broad-spectrum removal of multiple HMs. Cost-effective modification techniques can further enhance their performance without significantly increasing costs, while maintaining efficacy across a wide pH range to accommodate diverse environmental conditions. Additionally, these adsorbents are derived from sustainable sources, including crop straws, fruit shells, and plant residues, offering an environmentally friendly and economical alternative to conventional materials.

Table 3. Comparative performance of agricultural waste-derived adsorbents for HM removal: methods, materials, and efficiency

Method Agricultural waste adsorbent Adsorption capacity/removal efficiency Ref. NaOH treatment Rice straw Cd2+ removal: 61.5% [167] Zn2+ removal: 52.9% H2SO4 Rice husk Zn2+ maximum adsorption capacities: 19.38 mg/g [168] Hg2+ maximum adsorption capacities: 384.62 mg/g Tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA) Ramie fiber Cu²+ maximum adsorption capacities: 0.587 mmol/g [169] Grinding & drying Walnut shell Cr6+ maximum adsorption capacities: 16.73~40.99 mg/g [170] NaOH + citric acid Peanut shell Cu²+ removal: 31% [171] NaOH + epichlorohydrin + N, N-dimethylformamide + TETA Pomelo peel Cr6+ maximum adsorption capacities: 193.17 mg/g [172] NaOH + TEMPO + NaBr + NaClO Luffa sponge Pb²+ maximum adsorption capacities: 96.6 mg/g [173] NaOH treatment Watermelon rind Cu2+ removal: 99.53% [174] Brine sediment Sawdust Zn: 5.59 mg/g [175] Cu 4.33 mg/g Boiling in HCl Coffee grounds Pb: 61.6 mg/g [176] Grinding & drying Pine cone Cr6+ removal: 90.84% [177] Grinding & drying Apple pomace (AP) & beetroot

residue (BR)Max Pb adsorption: 31.7 mg/g (AP), 79.8 mg/g (BR) [178] Grinding & drying Crab shell Pb removal > 97% [179] Cd removal > 90% TEPA + BCTTC Modification Metasequoia sawdust (MS) Pb2+ removal: 24.0% [180] Cd2+ removal: 93.2% Cyclopropylene chloride cross-linked polyethylene imine (PEI) and coconut shell carbon (CSC) Sugarcane bagasse, corn cob, peanut shell, coconut shell carbon (CSC) Complete removal (100%) of Cr6+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Cd2+ in

10 min[181] Polydopamine (PDA) functionalization Juncus effusus (JE) fiber Cr6+ maximum adsorption capacities: 145.8 mg/g [182] The commercial viability of adsorption-based treatment plants is influenced by several key factors. Among these, fixed and operational costs—such as installation expenses, adsorbent preparation and pretreatment expenditures, and regeneration costs—are particularly significant. Despite the enforcement of increasingly stringent environmental regulations, certain industrial sectors continue to exceed permissible limits for discharging harmful chemicals. Although some industries have adopted adsorption technology due to its relatively low cost, the assessment of its effectiveness largely depends on laboratory-scale batch adsorption experiments, while data from continuous-flow studies remain notably scarce[165].

Furthermore, large-scale process design necessitates accurate estimation methods for kinetic parameters, isotherm models, and thermodynamic parameters in multicomponent systems, thereby imposing higher requirements on the accuracy of adsorption modeling. In the context of sustainable development, spent adsorbent regeneration critically enables waste stream reduction, secondary pollution prevention, and operating cost optimization. Simultaneously, recovering adsorbed substances not only enables the production of valuable byproducts but also helps mitigate environmental risks. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop environmentally benign and cost-effective regeneration techniques that enhance the reusability of adsorbents over multiple cycles[166].

Phytoremediation

-

Large aquatic macrophytes have demonstrated remarkable potential for accumulating HMs, with accumulation levels reaching up to 100,000 times the HM concentrations in surrounding water[183]. The mechanisms by which plants remediate HM-contaminated soil or water include phytoextraction, phytostabilization, phytovolatilization, and rhizofiltration[184]. Table 4 provides an overview of common aquatic plants that have been studied and validated for their ability to mitigate HM pollution in water. Based on current research data, aquatic plants demonstrate significant advantages and certain limitations in HM pollution remediation. In terms of treatment efficiency, representative species such as Lemna gibba achieve removal rates of 82%–95% for multiple metals, including Cd, Cu, Pb, Ni, and Cr[196], while Azolla exhibits even higher removal rates exceeding 92% for trivalent metals such as Pb2+, Al3+, and Fe3+[193], highlighting their exceptional broad-spectrum treatment capability and synergistic multi-pollutant removal characteristics. Regarding HM accumulation mechanisms, different species display distinct features: the root BAF of Vetiver for Cu reaches 2,313.89 under Al2(SO4)3 conditioning[187]. Notably, certain species, such as Chlorella vulgaris, can reduce molybdenum (Mo) concentrations from 0.540 mg/L to below the detection limit (< 0.0005 mg/L) within 72 h, achieving a removal efficiency of up to 99.9%[190]. This rapid removal capability highlights its potential for use in emergency remediation scenarios. However, these examples also highlight several existing challenges. For instance, different plant species have relatively specific environmental requirements. Lythrum salicaria L., for example, achieves optimal remediation efficiency only under a pH of 7 and an initial Ni2+ concentration of 10 mg/L[194]. Moreover, most plants require prolonged remediation periods, and due to limitations in current experimental settings, it is still uncertain whether large-scale application might result in these species becoming invasive within local ecosystems.

Table 4. Phytoremediation performance of various plant and algal species for HM removal from contaminated aquatic systems

Species Remediation site Remediation effect Target part Ref. Eichhornia crassipes Textile wastewater, mining wastewater Textile wastewater: Cr: 94.78%, Zn: 96.88%,

Mining wastewater: Fe: 70.5%, Cr: 69.1%Roots [185] Black algae Nutrient solution Cu2+: 61.4% Leaves [186] Cattail and vetiver Mensin gold bibiani Limited mining soil Hg: > 80%, As: > 80%, Cu: > 80%, Zn: > 80% Roots [187] Arundo donax and Phragmites australis Cartagena-La Unión mining area, Spain Phragmites australis: Pb: 480 mg/kg Stems and leaves [188] Arundo donax: Zn: 406 mg/kg Apium nodiflorum Nestos river, Greece The maximum daily removal capacity:

Cd: 0.208 kg, Cr: 0.45 kg, Cu: 0.368 kg, Pb: 0.113 kg,

Mn: 0.425 kg, As: 0.312 kg, Ni: 0.398 kg, Hg: 0.116 kg,

Zn: 0.357 kg, Sn: 0.197 kgWhole plant [189] Chlorella vulgaris Copper mine tailings water, northern Chile Cu: 64.7%, Mo: 99.9% Cell surface (adsorption) and intracellular (absorption) [190] Pistia stratiotes Steel mill wastewater Cd: 82.8%, Cu: 78.6%, Pb: 73% Roots [191] Salvinia natans Electroplating plant wastewater Zn: 84.8%, Cu: 73.8%, Ni: 56.8%, Cr: 41.4% Leaves [192] Azolla Polluted water bodies Al3+: 96%, Fe3+: 92%, Au3+: 100% Whole plant [193] Lythrum salicaria L Aquatic systems pH: 7 and Ni2+: 10 mg/L, Roots: 3,737.8 mg/kg,

Stems: 697 mg/kg, Leaves: 418.4 mg/kgRoots, stems and leaves [194] Stachys inflata Bama Pb-zinc mining area AMF + PGPR + earthworms: Pb availability increased:

25 mg/kg, Zn availability increased: 102 mg/kgWhole plant [195] Lemna gibba Hayatabad Industrial Estate (HIE) wastewater Cd: 95%, Cu: 93%, Pb: 82%, Ni: 88%, Cr: 92% Roots and shoots [196] Nymphaea aurora Hydroponic experiment pH: 5.5, Cd: 140 mg/g, Cd: 140 mg/g Shoots and leaves [197] Despite its notable advantages, including cost-effectiveness and environmental sustainability, phytoremediation still faces several technical challenges that limit its widespread application. First, most existing studies are based on controlled laboratory experiments or localized field trials conducted in specific contaminated areas, resulting in a lack of large-scale empirical validation. Second, the majority of research has concentrated on shallow water environments, leaving a significant knowledge gap regarding remediation effectiveness in deep-water systems. Third, successful implementation requires precise matching between plant species and pollutant—a requirement illustrated by Lythrum salicaria, which exhibits maximum Ni accumulation at pH 7[194]. However, natural fluctuations in water pH can significantly compromise its performance. Collectively, these limitations impede the engineering scalability and practical deployment of phytoremediation technologies. Therefore, future research should emphasize improving environmental adaptability assessments and optimizing critical process parameters to enhance reliability under variable conditions.

Biochar

-

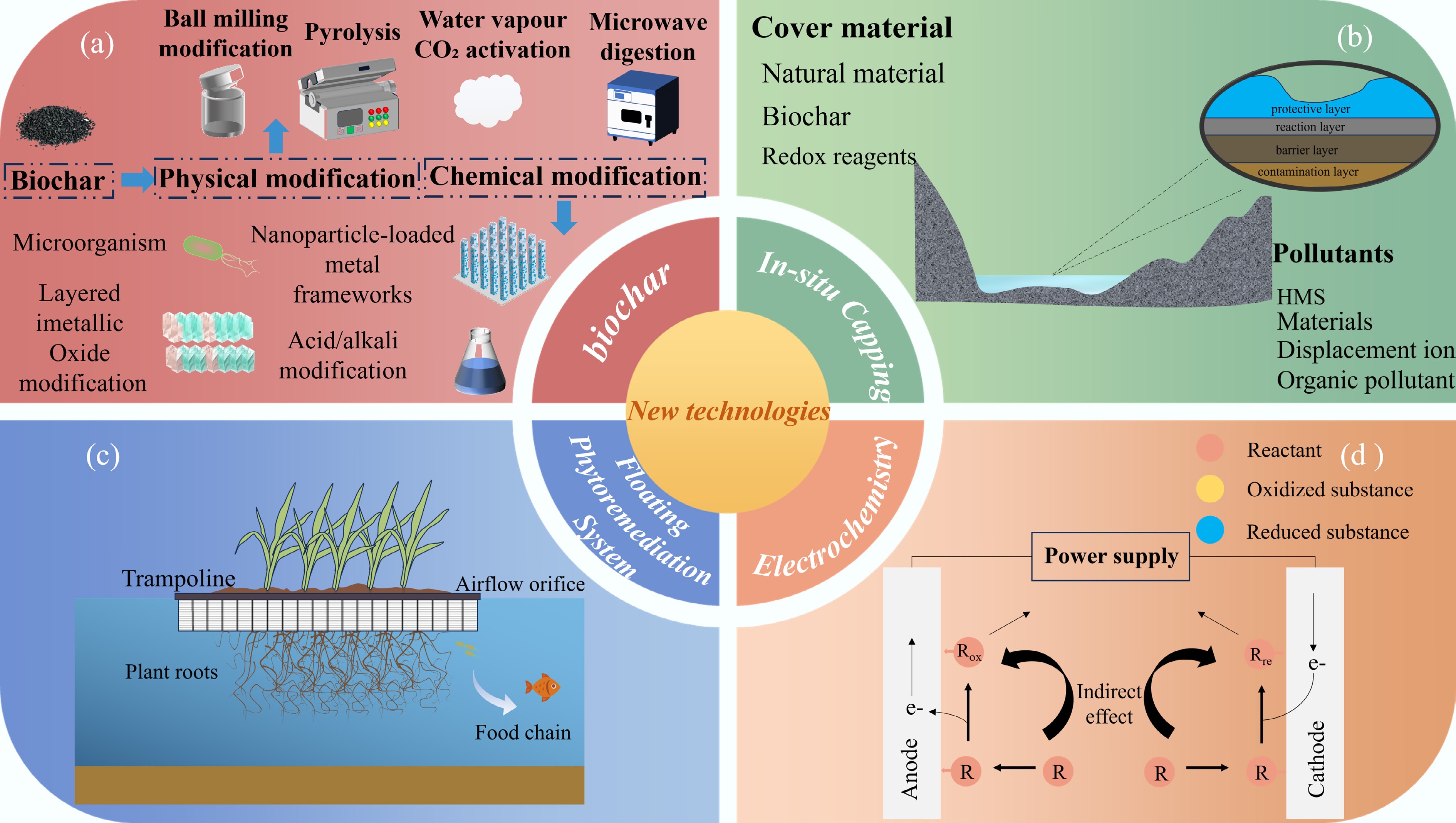

Biochar (BC) has emerged as a highly effective cross-medium remediation material, offering dual benefits for soil improvement and water purification. Due to its cost-effectiveness and environmental friendliness, BC remains a preferred option for metal ion removal in aquatic environments[198]. As shown in Fig. 5a, BC can be modified through various standard methods, which are broadly classified into physicochemical approaches. Modification strategies for biochar can significantly enhance its targeted removal capacity for specific pollutants, thereby improving its adaptability to the pollution characteristics of diverse aquatic environments. For instance, sulfurized magnetic biochar (SMBC) effectively reduces Cu/Ni/Zn concentrations in overlying water by 78%–92% and suppresses MeHg formation by 95%[199]. In another study focusing on Mn pollution in lake-reservoir systems, Zhao et al. developed a fixed-bed system utilizing rice straw biochars prepared at varying pyrolysis temperatures (300, 500, and 700 °C) and subjected to different modification methods (unmodified, pre-alkali treatment, and post-alkali treatment) to evaluate their dynamic adsorption behavior toward Mn2+. The findings revealed that pre-alkali-treated biochars exhibited significantly enhanced adsorption performance, with Pre-BC400 demonstrating a maximum static adsorption capacity of 41.06 mg/g. The Thomas model effectively described the dynamic adsorption process (R2 > 0.9). Both the initial Mn2+ concentration and influent flow rate were found to influence breakthrough and saturation times, indicating that operational parameters should be adjusted according to the severity of pollution in real-world applications. This research provides valuable technical insights for managing seasonal Mn contamination in lake reservoirs[200].

Figure 5.

The four HMs remediation methods introduced in this section are as follows: (a) Illustrates biochar modification approaches, including chemical modification and physical modification; (b) represents in situ capping technology; (c) stands for the Floating Phytoremediation System, also known as the Biological Floating Island; (d) denotes the electrochemical remediation method.

However, the practical applications of BC still faces several challenges: (1) difficulties in separation and recovery, as the small particle size of powdered BC complicates its effective separation from aqueous phases, potentially leading to secondary pollution; (2) limited regeneration capacity, as HM-laden BC is difficult to desorb, and improper disposal may transform it into hazardous waste; and (3) scalability bottlenecks, including regionally constrained raw material supply and low production yield due to high moisture content[201−203]. Therefore, future research should prioritize the development of more cost-effective, efficient, and environmentally sustainable methodologies.

In situ coverage and bio-floating island

-

In situ capping technology has emerged as an effective strategy for remediating HM-contaminated water bodies through innovative material design and process optimization. Figure 5b provides schematic illustrations of its working principles. This integrated approach combines physical containment, adsorption, and redox transformation to achieve sustainable remediation with minimal ecological impact. The system establishes a multifunctional barrier on the surface of contaminated sediments, which not only physically isolates and blocks HM diffusion pathways but also chemically immobilizes HMs via interactions with the capping material, thereby significantly reducing exposure risks to benthic organisms. Recent advances in remediation technologies have successfully overcome key limitations of traditional materials, such as poor selectivity and low stability. The electrokinetic-bioleaching coupled system (EK-bioleaching) demonstrates superior performance by reducing energy consumption by 40% and chemical costs by 45%, while effectively treating multiple metal contaminants to meet regulatory standards[204]. The multi-source mineral composite calcined material (MMCCM) reduces the diffusion flux of Cu/Co/Ni by 75%–82% through optimized particle size distribution[205]. A particularly noteworthy innovation is the ternary composite system composed of hydrothermal carbonized sediment (HCS), hydrated magnesium carbonate (HMC), and sodium percarbonate (SPC) at an optimal ratio of 25:60:15. This system simultaneously provides mechanical protection, chemical isolation, and oxygenation functions. It promotes the carbonation of Mn/Cu and regulates the specific binding of DOM fractions with metal ions: microbial byproducts and fulvic-like acids preferentially complex with Cu2+, while phenolic groups and HA tend to bind Mn2+. This significantly enhances remediation efficiency and environmental compatibility[206].

Bio-floating island technology, an environmentally friendly water remediation method introduced to China in the late 1980s, has become a critical tool for pollution control in lakes, reservoirs, and other water bodies. Figure 5c provides schematic illustrations of the working principles of bio-floating islands. By leveraging multiple mechanisms, including plant uptake, microbial metabolism, and substrate adsorption, this technology demonstrates exceptional pollutant removal efficiency while also providing ecological landscape benefits. Studies indicate that bio-floating islands are particularly effective in addressing HM pollution. Research shows that these islands exhibit significant remediation effects on HM contamination. For instance, a case study conducted in Loktak Lake, India, revealed that natural floating islands used as fish aggregation devices (FADs) could reduce Cd and Pb concentrations in water by 73.91% and 65.22%, respectively, while decreasing other HMs (Co, Cr, Cu, etc.) by 40.57%–49.16%. Simultaneously, HM accumulation in fish decreased by 24.07%–25.07%, significantly reducing ecological risks[207]. The research by Shahid et al. on four emergent plants (Brachia mutica, Typha domingensis, Phragmites australis, and Leptochloa fusca) in bacterial-assisted floating treatment wetlands (FTWs) revealed that bacterial inoculation significantly enhanced phytoremediation. The Phragmites australis plus bacteria group performed best, reducing Fe, Mn, Ni, Pb, and Cr concentrations to 0.53, 0.20, 0.09, 1.04, and 0.07 mg/L, respectively, after five weeks, with metals primarily accumulating in roots. Bacteria inoculation promoted metal uptake by enhancing plant biomass and root development, offering an eco-friendly solution for HM pollution[208].

These innovations address challenges such as secondary release and short remediation cycles, offering a reliable solution for the long-term treatment of HM-contaminated water[209]. As novel environmental functional materials and process intelligence continue to advance, in situ capping technology is rapidly progressing toward greater precision, sustainability, and eco-friendliness, demonstrating significant potential for widespread application. Additionally, research indicates that bio-floating islands effectively reduce HM pollution. Critical factors influencing the efficiency of HM removal include the selection of macrophyte species, the construction of microbial communities, and the integration of plant-microbe remediation strategies. Nevertheless, practical implementation necessitates careful attention to invasive species management and the prevention of material pollution[210,211]. Bio-floating island technology leverages its distinctive ecological purification mechanisms to provide sustainable solutions for addressing waterborne HM contamination, highlighting its significant potential for future environmental applications.

Electrochemical methods and electrokinetic remediation

-

Standard electrochemical methods employed in aquatic environments include electrochemical oxidation and reduction, electro-Fenton (EF) processes, electro-deionization, electrodialysis (ED), electroflotation, electrocoagulation, and capacitive deionization (CDI). These technologies offer functionalities that traditional approaches cannot achieve. In recent years, driven by innovations in nanomaterial-modified electrodes and process optimization, electrochemical techniques have seen significant advancements in the control of HM pollution, leading to a comprehensive technological transformation from monitoring to treatment[212]. Advanced sensing systems, such as GO-modified carbon felt electrodes, utilize their high-density surface functional groups to enhance electrodeposition capacity up to a hundredfold compared to conventional methods. A single gram of this material can effectively process over 29 g of HMs while maintaining detection sensitivity at the parts-per-billion (ppb) level. Regarding treatment processes, alternating current electrodeposition technology enables the selective recovery of HMs such as Cu, Cd, and Pb with removal efficiencies exceeding 99.9%, achieved through precise regulation of electrical parameters (0.1–10 kHz, 1–5 V). Meanwhile, the combined electrocoagulation-electroflotation process achieves a 98.7% Cr removal efficiency at a current density of 20 mA/cm2 while simultaneously reducing sludge production by 60%[213]. These innovative technologies surpass conventional methods by enabling on-site detection, reducing operational costs, and effectively utilizing existing infrastructure[214]. Although further research is needed to enhance electrode durability and develop advanced intelligent control systems, integrating nano- and micro-materials into newly developed electrochemical sensors offers groundbreaking solutions for establishing environmentally sustainable HM treatment systems[215]. As modular systems continue to evolve and processes become more refined, this technology is expected to become the preferred solution for addressing HM contamination in aquatic environments. Figure 5d illustrates a typical electrochemical method used for treating HMs in polluted water bodies.

Electrokinetic remediation has emerged as a novel and promising approach for HM pollution control. By utilizing low-intensity electric fields, this method drives multiple mass transfer processes such as electroosmosis, electromigration, and electrophoresis, enabling efficient removal of HMs from contaminated media[216]. Putra et al. explored the efficiency of an electrokinetic-enhanced phytoremediation (EP) system using Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.) for Pb2+ removal in contaminated water. The study demonstrated that a 2D electrode configuration promoted a V-shaped distribution and facilitated the migration of Pb ions toward the plant root zone in an agar medium. The EP system, when supplemented with 0.01% urea, significantly enhanced the bioconcentration factor (BC, up to 24.01) and translocation factor (TF, up to 0.61) for Pb. Additionally, the plants exhibited tolerance to Pb stress by maintaining chlorophyll content and biomass, offering an effective ecological solution for HM-contaminated water remediation[217]. Another study assessed the removal efficiency of electro-stimulated phytoremediation for Pb, Cr, and Cu in water using three experimental setups: phytoremediation alone, electrokinetic remediation alone, and combined electrokinetic-phytoremediation. Results demonstrated that the aluminum electrode-based electro-phytoremediation system, operating at 4V with a daily runtime of 2 h, achieved significantly higher removal efficiencies for Cd, Pb, and Cu compared to individual remediation methods. Complete removal (100%) of Cd and Pb was achieved within 15 d, while Cu was fully removed within 10 d. Electrical stimulation markedly enhanced the BCF of water hyacinth, demonstrating hyperaccumulation capacities for Cd and Cu. Additionally, electrostimulation promoted chlorophyll synthesis, improved plant growth, and enhanced stress resistance, highlighting the technology's potential for treating HM-contaminated wastewater[218]. Currently, this method presents several limitations, including uneven electric field distribution in large water bodies, susceptibility of electrode materials to corrosion and rapid degradation, and the potential for the installation to alter the pH and other physicochemical properties of the water body, which may subsequently impact the ecosystem. Despite significant advancements in electrokinetic remediation for soil applications, challenges remain for its implementation in large water bodies such as reservoirs, particularly in terms of optimal electrode configuration, energy consumption optimization, and ecological safety considerations[219]. Further research is required to address critical issues, including the selection of suitable electrode materials, optimization of operational parameters, and long-term ecological impact assessments, to facilitate the transition from laboratory-scale studies to practical engineering applications.

-

Research on HMs in reservoirs carries substantial ecological and public health significance. Its primary strength lies in enabling early identification of pollution risks from toxic HMs through scientific monitoring and assessment, thereby providing essential data that also allows for tracing pollution origins, supporting the formulation of source control strategies. In addition, advances in novel removal technologies and eco-friendly materials have enhanced progress in water pollution treatment, reducing remediation costs and contributing to long-term drinking water safety and aquatic ecosystem stability. However, traditional risk assessment methods face notable limitations in addressing complex scenarios such as combined pollution and chronic low-dose exposure, often failing to accurately evaluate potential risks. Meanwhile, intelligent monitoring technologies require further improvements in environmental adaptability and predictive accuracy to fulfill demands for real-time and precise monitoring. Furthermore, while promising, current research remains largely experimental, necessitating additional studies before these approaches can be broadly applied in pollution remediation efforts. Although emerging technologies such as nanomaterials and bioremediation demonstrate efficient HM removal capabilities, their engineering applications face limitations due to multiple challenges, including material stability, ecological safety, and cost-effectiveness. In addition, the absence of unified production standards and long-term efficacy evaluations complicates the harmonization of significant variations in preparation methods, action mechanisms, and practical implementations across different materials.