-

Fluctuations in environmental factors are unpredictable, exposing plants to different levels of biotic and abiotic stresses[1,2]. Abiotic stress, caused by nonliving environmental factors such as drought, salinity, and extreme temperature variations, severely disrupts plant physiology by impairing cellular homeostasis and transcriptional regulation[3]. These stressors interfere with critical metabolic processes, including enzymatic activity, ion balance, and membrane stability, ultimately stunting plant growth, development, and agricultural productivity[3]. Projected climate scenarios show rising global average temperatures exacerbating heat stress, which would disrupt plant photosynthesis, nutrient assimilation and reproductive development, ultimately reducing crop yields[4]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2021) forecasted a steady temperature increase of 0.2 °C per decade, and each 1 °C increase would reduced staple crop yields by 3%−7%, primarily through disrupted phenological phases and accelerated oxidative damage[5,6].

As sessile organisms, plants dynamically reconfigure their regulatory networks through evolutionary adaptation, enabling integrated control of gene expression and metabolic pathways to deploy robust stress-response strategies[7]. A pivotal mechanism in this adaptive repertoire is stress memory acquisition, wherein plants 'learn' from prior environmental challenges to optimize future responses[8]. Stief et al. delineated a tripartite framework for heat tolerance in Arabidopsis: (1) basal thermotolerance, (2) acquired thermotolerance, and (3) sustained acquired thermotolerance[9]. Basal thermotolerance relies on constitutive molecular chaperones [e.g., HSP (heat shock proteins)] and antioxidant systems, whereas acquired tolerance involves transcriptional reprogramming triggered by heat priming[9]. This priming-induced tolerance can either fade quickly or stabilize into heritable heat memory through epigenetic mechanisms (chromatin remodeling, DNA methylation, or small RNA regulation), preparing plants for recurring heat stress[9]. Heat stress memory, an epigenetically regulated mechanism, enables plants to retain molecular imprints of prior thermal exposure, thereby enhancing their physiological resilience under recurrent high-temperature stress[10]. This process involves chromatin remodeling, transcriptional priming, and post-translational modifications that prolong thermotolerance. Heat memory preserves acquired stress resistance by maintaining stress-activated proteins (e.g., heat shock factors) and epigenetic markers (e.g., histone acetylation), enabling plants to better withstand subsequent heat stress[10].

Escalating global temperatures would critically impair plant growth, reproductive success, and agricultural productivity and threaten food security. Decoding the molecular mechanisms governing heat stress memory thus becomes imperative for breeding climate-resilient crops. Existing approaches to boosting heat tolerance—from cross-breeding to genetic engineering—remain limited by poor trait inheritance, slow development timelines, and economic barriers[11]. In contrast, harnessing heat stress memory—a plant's epigenetic capacity to 'remember' prior heat exposure—offers a paradigm-shifting solution. This strategy leverages endogenous priming mechanisms (e.g., histone modification, DNA methylation) to precondition crops for recurrent heatwaves, thereby reducing dependency on resource-intensive breeding while improving yield stability under thermal extremes. Crucially, heat stress memory-based approaches align with socioeconomic viability, particularly benefiting smallholder farmers in heat-vulnerable regions. This review systematically examines (1) the pheno-physiological adaptations linked to retained heat resilience; (2) the molecular architecture of heat stress memory, focusing on chromatin dynamics and memory-associated genes (e.g., HsfA2, HSP22); and (3) the epigenetic-metabolic crosstalk modulating intergenerational stress inheritance.

-

When ambient temperatures surpass the optimal growth thresholds of plants, heat stress ensues, triggering irreversible damage to their growth and development[12]. Elevated temperatures disrupt cellular homeostasis and inhibit plant growth and development, and may ultimately lead to plant mortality[13]. Under high-temperature conditions, carbon assimilation processes in plants are significantly suppressed, resulting in markedly reduced photosynthetic efficiency[14]. Concurrently, elevated temperatures induce oxidative damage and interfere with normal metabolic pathways, thereby affecting the accumulation of both primary and secondary metabolites[15]. Furthermore, heat stress impairs normal protein synthesis, leading to the inactivation of key enzymes and damage to cellular membrane systems, ultimately causing severe detrimental effects on crop plants[16].

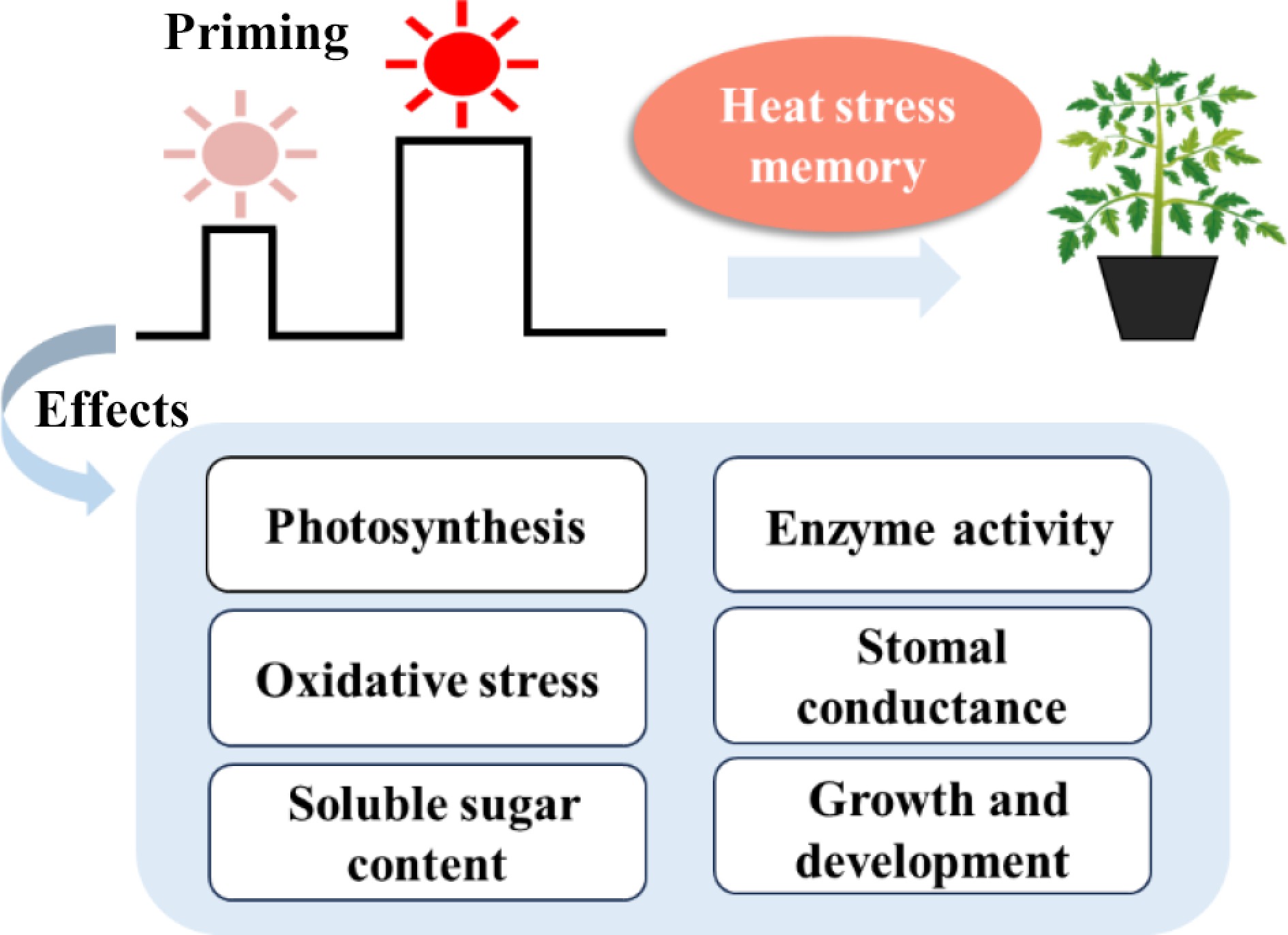

Plants possess the capacity to methodically modulate their physiological and morphological responses through establishing heat stress memory, a process that substantially enhances their adaption to subsequent heat stress (Fig. 1)[7,17,18]. Research has demonstrated that the establishment of heat stress memory is associated with a multitude of physiological regulatory mechanisms. Zhou et al. found that two rounds (day/night temperature 38/33 °C) of high-temperature treatments in tomato resulted in increased transpiration rate and stomatal conductance in the leaves, thereby significantly enhancing the leaves' cooling ability[17]. This study revealed that the initial round of high-temperature treatment enhanced the plant's capacity to adapt to repeated high-temperature environments via promoting leaf transpiration[17]. Sun et al. confirmed that tomato seedlings pretreated at 35 °C for 24 h had an elevated total hydrogen peroxide content and a significantly decreased heat damage index in their leaves under subsequent 45 °C high-temperature stress conditions[7]. The findings indicated that heat priming induced plants to establish high-temperature stress memory, which significantly enhanced the heat tolerance of seedlings by regulating the ROS (reactive oxygen species) metabolic pathways[7]. Olas et al. demonstrated that Arabidopsis subjected to 37 °C for 2 days exhibited a high survival rate at the lethal temperature of 44 °C, while all unpretreated plants perished[18]. Heat priming significantly modified starch metabolic enzymes and increased soluble sugar content, demonstrating enhanced plant tolerance to subsequent heat stress[18].

Figure 1.

Heat priming induced heat stress memory, allowing the tomato plants to acquire heat tolerance via physiological and morphological regulation.

Phytohormones as key signaling molecules regulating heat stress memory

-

Phytohormones function as pivotal signaling molecules that integrate external environmental stimuli with endogenous developmental signals to synergistically regulate adaptive defense responses to heat stress in plants[19]. Abscisic acid (ABA) induces NADPH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate hydrogen) oxidase-mediated ROS production to activate antioxidant defenses while modulating sucrose metabolism and heat shock factor/protein (HSF/HSP) pathways[19]. The growth hormone auxin promotes thermomorphogenesis through HSP90-dependent receptor stabilization, and PIF (phytochrome interacting factor) regulates biosynthesis, driving hypocotyl elongation[19,20]. Brassinosteroids (BRs) enhance thermotolerance by stimulating HSP synthesis and membrane protein (e.g., ATPase and water channel proteins) accumulation, activating the RBOH1-H2O2-MPK2 (respiratory burst oxidase homolog 1-hydrogen peroxide-mitogen-activated protein kinase 2) signaling cascade[19,21,22]. Cytokinins (CKs) increase root antioxidant enzyme activities and HSP levels[19], and maintain stomatal regulation and stress protein homeostasis[23]. Altogether, these points demonstrate sophisticated hormonal coordination in plants in response to heat stress, which has significant implications for vegetable crop improvement.

Plant hormones have been demonstrated to exert a pivotal regulatory function in the process of heat stress-induced memory formation[8]. For example, ABA signaling cooperates with Switch/sucrose nonfermentable (SWI/SNF) chromatin remodelers to modify the chromatin structure, increasing stress-responsive genes' sensitivity to transcription factors and promoting long-term stress memory[24]. Yao et al. discovered that treatment of Arabidopsis seedlings with BRs resulted in a significant enhancement of heat tolerance and survival rate following heat priming[25]. The BR signaling pathway activates heat memory genes' expression by promoting dephosphorylation of BES1 (BRI1-ethyl methyl sulfon-SUPPRESSOR) and functions as a mediator of chromatin remodeling and H3K27me3 (histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation) demethylation, thereby ensuring the sustained activation of genes[25].

Molecular mechanisms underlying heat stress memory

-

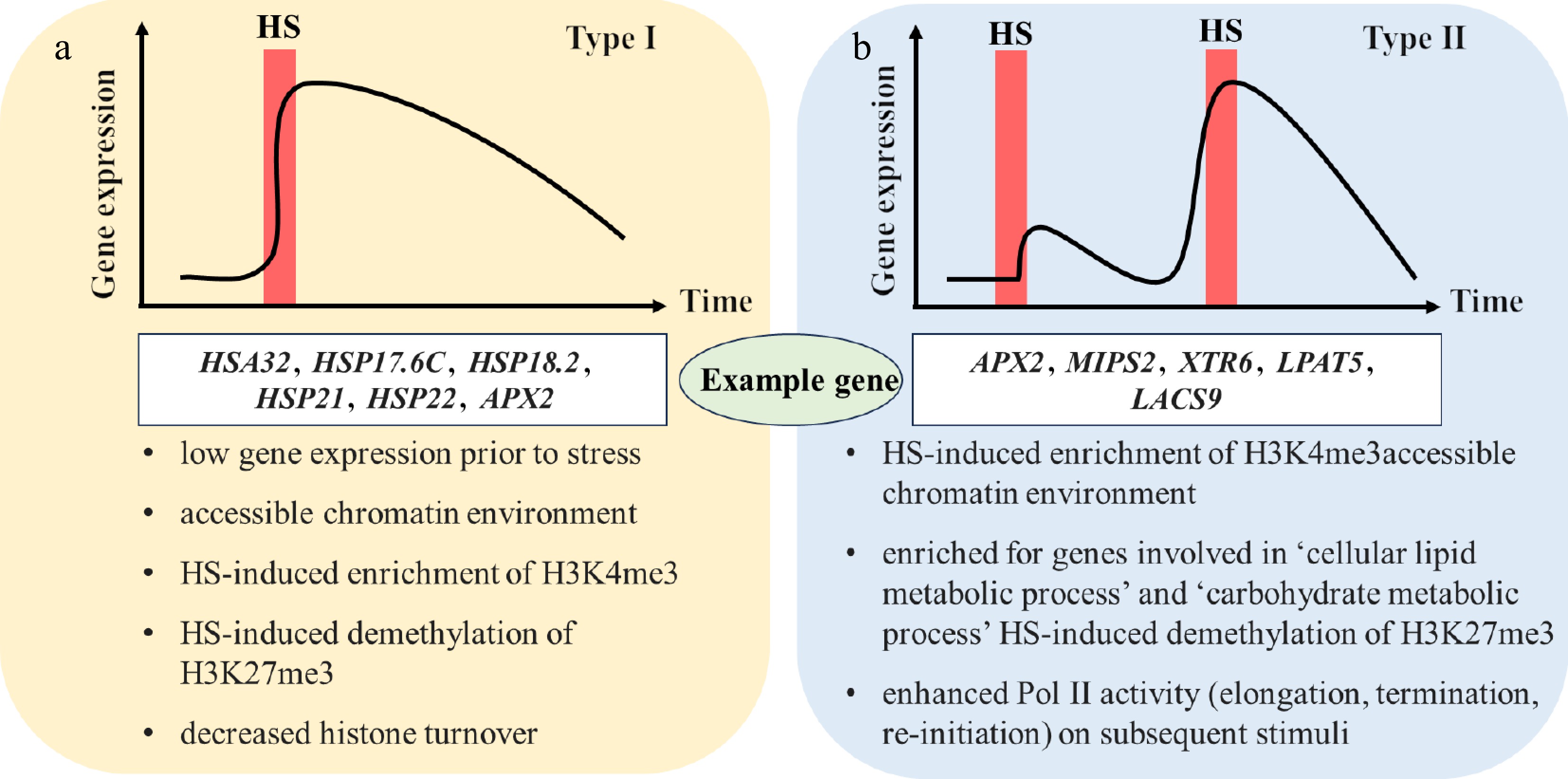

Heat stress induces transcriptional memory, characterized by sustained gene expression after transient stimulation or altered activation patterns under repeated stress[26]. Transcriptional memory comprises two types: Type I maintains sustained expression after stress ends, while Type II exhibits enhanced reactivation upon recurring stress (Fig. 2)[27]. Type I genes include HSP21 and HSP22, and Type II genes include MIPS2 (enzyme l-myo-inositol 1-phosphate synthase) and APX2 (ascorbate peroxidase)[26]. Subsequent stress alters plants' transcriptional responses, with memory genes showing distinct activation patterns compared with nonmemory genes[28]. In heat stress, memory genes such as APX2 and HSA32 (heat-induced 32-kD protein) are continuously induced after heat stress[29]. Nonmemory genes, such as HSP70 and HSP101, are induced to exhibit rapid loss during recovery[29]. Research on the regulation of heat stress memory has mainly concentrated on the transcriptional regulation of Hsfs, the stability of HSPs, and epigenetic modifications.

Figure 2.

Two types of transcriptional memory: (a) Type I, sustained induction; (B) Type II, enhanced re-induction. This was made according to Pratx et al.[26], with some revisions. The red bar represents HS (heat stress), and x and y axes represents time and gene expression, respectively. The white boxes correspond to the related genes of the two types, followed by their features below the box. HSA, heat-induced protein; HSP, heat shock protein; APX, ascorbate peroxidase; MIPS, enzyme l-myo-inositol 1-phosphate synthase; XTR, xyloglucan endotransglycosylase; LPAT, lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase; LACS, long-chain acyl-coenzyme A synthetase.

Roles of Hsfs and HSPs in heat stress memory

-

Hsfs play a key role in heat stress memory (Table 1)[4,30]. These key transcription factors regulate signaling pathways to activate HSPs' expression, effectively maintaining plant cells' stability under repeated high-temperature conditions[4]. For instance, the transcription factor HsfA2 plays a pivotal regulatory role in the context of heat stress memory[30]. Following a mild heat stress pretreatment in Arabidopsis, HsfA2 knockout lines exhibited significant heat sensitivity when subjected to more severe heat stress[30]. Conversely, the overexpression of HsfA2 significantly enhanced heat tolerance in plants[31]. HsfA2 is indispensable for the formation of both types of transcriptional memory[29]. HsfA2 and HsfA3 form a heterodimeric complex that plays a pivotal role during the process of heat stress memory[29]. In tomato, HsfA1-overexpressing lines demonstrated superior growth in comparison with the wild-type following two stages of treatments at 45 and 51 °C[32].

Table 1. Plant heat stress memory-related Hsfs and HSPs

Type Function Ref. HsfA2/

HsfA3HsfA2 and HsfA3 maintain sustained expression of thermal memory-related genes by recruiting the methylation of histone H3K4. This epigenetic modification contributes to chromatin opening, which promotes the transcriptional activation of genes. [29] HsfA2 HsfA2 binds to heat memory gene promoters, sustaining their high expression after heat stress and prolonging the duration of AT via maintained HSP expression. It also regulates the H3K4me3 memory locus, preserving chromatin's openness for continuous transcription. [30] HsfA2 HsfA2 is able to bind to the promoter of the plastidial metalloproteinase FtsH6 gene and activate its expression. FtsH6 resets the thermal memory during the heat recovery phase by degrading HSP21 to the priming level. [31] HsfA1 HsfA1 is rapidly activated under heat stress conditions and coordinates heat tolerance in tomato by initiating the transcription of a large number of downstream heat-responsive genes. [32] HSP21 Sustained high expression of HSP21 is a key factor in the maintenance of thermal memory. During the thermal memory phase, the level of HSP21 determines the duration of thermal memory. [33] HSP101/

HSA32HSP101 and HSA32 play important roles in heat acclimation memory in Arabidopsis through the formation of positive feedback loops, post-transcriptional regulation, and maintenance of protein stability. [34] sHSP22 sHSP22 plays a role in the formation and maintenance of thermal memory by regulating growth hormones' polar transport and ABA signaling. [35] Hsfs, heat shock transcription factor; H3K4, histone H3 lysine 4; AT, acquired thermotolerance; HSPs, heat shock proteins; H3K4me3, histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation; FtsH6, filamentation temperature-sensitive H6; HSA32, heat-induced 32-kD protein; sHSP22, small heat shock protein 22. HSPs are also important for regulating heat stress memory in plants (Table 1)[10]. Sedaghatmehr et al. found that both the transcript levels and protein expression of HSP21 in Arabidopsis remained elevated during the heat memory phase after heat priming[33]. Further analysis showed that HSP21-overexpressing plants had higher survival rates with significantly increased seedling fresh weight, confirming HSP21 as a key component for heat stress memory[33]. Wu et al. demonstrated that HSA32 expression was markedly reduced in the hsp101 mutant during heat stress recovery, indicating that HSP101 positively regulates heat-induced HSA32 accumulation[34]. Notably, the hsa32-1 mutant exhibited a significantly accelerated degradation rate of HSP101 protein, underscoring the critical role of HSA32 in stabilizing HSP101[34]. The results suggest that HSP101 and HSA32 form a stable positive feedback regulatory loop that enhances each other's stability, thereby prolonging the duration of heat stress memory in Arabidopsis[34].

Roles of epigenetics in heat stress memory

-

Epigenetic mechanisms are central to heat stress memory, as evidenced by the roles of chromatin remodeling, DNA methylation, histone modifications, and regulation by noncoding RNAs[36]. One of the most prevalent histone modifications is methylation, playing a pivotal role in heat stress memory in plants[37]; see the detailed evidence shown in Table 2. Song et al. found that the histone methyltransferases SDG25 (Set Domain Group) and ATX1 (the Arabidopsis homolog of trithorax) in Arabidopsis are essential for maintaining stress-responsive gene expression during the stress recovery period[38]. They determined that these methyltransferases' H3K4me3 modifications increased and DNA methylation decreased, resulting in a 'transcriptional memory' under heat stress[38]. Lämke et al. demonstrated that there was a sustained accumulation of H3K4me3 and H3K4me2 (H3K4 dimethylation) at heat stress memory-related gene loci (APX2 and HSP22.0), and that elevated levels of this histone methylation modification are strongly associated with the formation of transcriptional memory[39]. Recent advances in single-cell RNA-seq have revealed the diversity of cell types and their transcriptional networks in plants' heat tolerance[40]. Integrated multi-omics approaches, including ATAC-seq (assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing) and GWAS (genome-wide association study), have identified key candidate genes, with further studies confirming their roles as critical regulators in the heat stress response[41,42]. The application of state-of-the-art molecular tools to the study of molecular mechanisms of high-temperature stress memory will provide a novel molecular perspective. Information on the key genes and proteins mentioned is shown in Supplementary Table S1 and S2, respectively.

Table 2. Histone-modifying epigenetic genes for heat stress memory in plants.

Type Function Ref. SDG25/

ATX1Mutations in SDG25 and ATX1 decrease histone H3K4me3 levels, increase DNA cytosine methylation, and suppress the expression of a subset of heat stress-responsive genes during stress recovery in Arabidopsis thaliana. [38] H3K4me3/H3K4me2 H3K4me2 and H3K4me3 are involved in transcriptional memory transmission during heat shock memory. [39] JMJ JMJ has H3K27me3 demethylase activity and is able to remove H3K27me3 modifications on heat memory-related genes such as HSP22 and HSP17.6C. [43] CSN5A The CSN5A subunit can regulate heat stress memory by resetting the heat stress memory genes APX2 and HSP22 and affecting H3K4me3. [44] ATX1 ATX1 is an H3K4 methyltransferase that has been shown to regulate H3K4me3 levels at the promoter of heat stress recovery genes. [45] SDG25, Set Domain Group; ATX1, Arabidopsis homolog of trithorax; H3K4me3, histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation; H3K4me2, histone H3 lysine 4 dimethylation; JMJ, Jumonji domain-contaning protein; H3K27me3, histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation; HSPs, heat shock proteins, CSN5A, constitutive photomorphogenesis 9 signalosome 5A; APX2, ascorbate peroxidase. -

The development of heat stress memory in plants is regulated by a number of factors, including the duration of heat priming, stress intensity, recovery duration, and different species and genotypes[7,46,47]. Sun et al. found that plants treated with a high temperature (35 °C) for 14 h and then recovered at 25 °C for 1.5 h exhibited superior growth performance under subsequent 45 °C stress conditions compared with those that recovered for 24 h[7]. Sun et al. found that tomato plants were exposed to different temperatures (35, 38, and 40 °C) at the same initiation time (14 h) and discovered that plants exposed to 35 °C exhibited the lowest heat damage index[46]. Furthermore, it was determined that heat-sensitive genotypes required a longer initiation period compared with heat-tolerant genotypes[46]. Oyoshi et al. found that after 5 min of heat stress at 40 °C, Arabidopsis exhibited a decreasing trend in the expression of most genes at 1 h of recovery at 21 °C[47]. However, the expression of genes that experienced 45 min of heat stress was highest at 1 h of recovery[47].

-

Heat stress memory—the epigenetic capacity of plants to retain and recall prior heat exposure—serves as a critical evolutionary adaptation enabling survival under escalating thermal extremes, positioning it as a strategic tool for climate-resilient agriculture[10]. Understanding heat stress memory is crucial for developing crops with sustained heat resilience. This review synthesizes recent breakthroughs underlying heat stress memory in plants. By leveraging these insights, next-generation molecular breeding could bypass conventional trial-and-error approaches, achieving precise thermotolerance enhancement while conserving genetic diversity. Future research must prioritize three frontiers: (1) Multi-omics analysis of single-cell RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, spatial omics, GWAS etc. to map chromatin accessibility and metabolic fluxes under repeated heat pulses; (2) transgenerational optimization to engineer heat memory heritability using engineered nanoparticles loaded with siRNA (small interfering RNA) targeting DNA methyltransferases; and (3) crop democratization, translating heat stress memory strategies from model systems (Arabidopsis) to climate-vulnerable crops, especially for vegetable crops (e.g., tomato, cucumber, pepper) through pan-genome-guided chromatin landscaping. Through the application of innovative and combined strategies, significant progress into uncovering the underlying heat stress memory mechanisms in plants will be made, which will benefit crop productivity and sustainability under global warming conditions.

We acknowledge the funding from Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (KJYQ2025027), Jiangsu Seed Industry Revitalization project [JBGS(2021)015], the earmarked fund for China Agriculture Research System (CARS-23), and the Bioinformatics Center of Nanjing Agricultural University.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhou R; draft manuscript preparation: Liu Y, Sun Y; tables and figures preparation: Zhou R, Liu Y, Sun Y; reviewing and editing with valuable comments: Lv P, Li Y, Ding F, Jiang F, Song X, Wu Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Detailed information of the key genes related to heat stress response in Arabidopsis thaliana mentioned in the review.

- Supplementary Table S2 Detailed information of the key proteins related to heat stress response mentioned in the review.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu Y, Sun Y, Lv P, Li Y, Ding F, et al. 2025. Morphological, physiological, and molecular mechanisms underlying heat stress memory in plants. Vegetable Research 5: e035 doi: 10.48130/vegres-0025-0036

Morphological, physiological, and molecular mechanisms underlying heat stress memory in plants

- Received: 12 April 2025

- Revised: 24 June 2025

- Accepted: 21 August 2025

- Published online: 19 September 2025

Abstract: Increasing climatic unpredictability makes plants suffer different environmental stresses, with escalating global temperatures positioning heat stress as a principal abiotic constraint. Exposure to excessive heat destabilizes cellular homeostasis, impairing growth trajectories and photosynthetic capacity while potentially triggering irreversible physiological impairments. Nevertheless, plants exhibit stress-priming capabilities through heat-induced molecular memory mechanisms that bolster tolerance to recurrent thermal challenges. In the context of global warming, elucidating the mechanisms underlying plants' heat stress memory and response is crucial for improving crops' resilience and adaptation. This review systematically elaborated the morphological, physiological, and molecular mechanisms underlying heat stress memory, in which phytohormones are key signaling molecules regulating the stress memory. The role of Hsfs (heat shock transcription factor), HSPs (heat shock proteins), and genetic and epigenetic regulation in plant heat stress memory were clarified. Furthermore, the factors (e.g., priming and recovery duration, species, and genotype differences) affecting heat stress memory were clarified. This study will contribute to mitigating the adverse effects of global warming on crop productivity and propose novel strategies for incorporating these findings into molecular breeding programs to enhance crop thermotolerance.