-

Northeast China, encompassing the Songhua River and Liaohe River Basins—two of China's Level-I Water Resource Zones—covers an area of 1.45 million km2. It spans the provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning, as well as eastern Inner Mongolia and northern Hebei[1]. This region contains China's largest expanse of black soil, approximately 1.09 million km2, and serves as a critical national grain-producing area[2]. In 2023, the three northeastern provinces achieved a combined grain output of 145 million metric tons, accounting for 21% of the country's total production. The large-scale agricultural development in Northeast China began in the 1980s. From 1986 to 2023, the agricultural cultivation area increased from 158,000 to 315,000 km2, nearly doubling, while grain production increased by 2.75 times. However, the rapid expansion of agriculture has imposed substantial ecological costs. The large-scale conversion of natural landscapes into farmland has resulted in wetland loss, declining groundwater levels, altered river flow regimes, and the degradation of habitats for endemic cold-water fish and migratory bird species[3].

Constrained by resources such as water, land, and space, there exists a significant competitive and coupling relationship between agricultural production and ecological protection. Overall, researchers hold both positive and negative assessments regarding the impact of agricultural production on the ecosystem. Some scholars have primarily focused on the damage caused by agricultural production to the ecosystem, and have suggested limiting or even reducing the scale of agriculture. Ecological researchers pay close attention to the ecological damage caused by agricultural activities, while some scholars emphasize the role of green agriculture in ecological improvement[4−6]. Win–win solutions that both conserve biodiversity and promote human well-being are difficult to realize. Trade-offs and the hard choices they entail are the norm[7]. How to balance ecological health and food security is a scientific and management issue that needs to be addressed urgently[8,9]. Especially for Northeast China, that has a crucial strategic position in the development of China's food security and ecological civilization construction, which is why research focusing on this region will be more practically meaningful. However, the factors causing conflicts between agriculture and ecology are complex and closely related to the features of study areas[10]. There are still shortcomings and challenges in scientifically understanding and balancing agricultural development and ecological protection in Northeast China.

Overall, scholars studying the balance between agriculture and ecology mainly focus on the following two aspects: (1) The balance between agricultural water use and ecological water use. Pang et al.[11] developed a water-use conflict analysis framework to optimally balance water requirements for ecosystems and human activities. Banadkooki et al.[12] proposed an integrated optimal allocation model to resolve water resource conflicts between agriculture and ecology in an arid area. (2) The balance between agricultural and ecological space demands. Studies have revealed the direct and indirect effects of agricultural expansion on wetland area and fragmentation[13,14]. Additionally, a number of models have been developed to analyze the changes in the distribution patterns of farmland and wetlands and to optimize them, including the CA-Markov model[15], the CLUE-S model[16], and the FLUS model[17]. In this paper, the interactions between agriculture and ecology in Northeast China are revealed, focusing on resource allocation and spatial distribution. Furthermore, the key contradictions between agricultural development and ecological protection are analyzed, and the corresponding integrated regulatory measures are proposed.

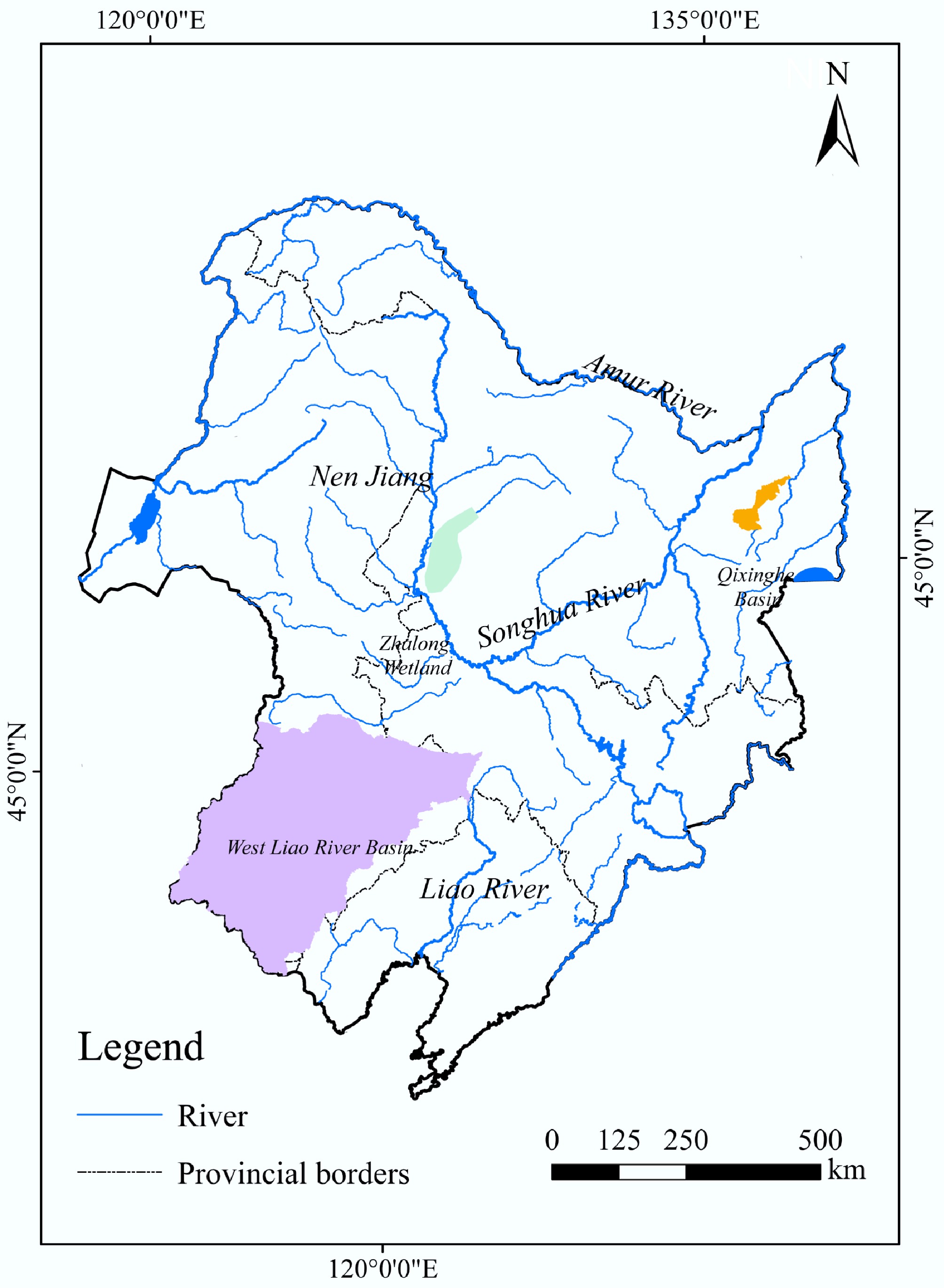

The study took the entire region and several typical river basins as the research areas (Fig. 1), and adopted an integrated point-area analytical approach. Owing to the complexity of the research subject, the data employed in this paper were diverse, encompassing remote sensing interpretation, site monitoring, and model simulations. Meanwhile, several technical approaches were proposed. A coupled hydrological and hydrodynamic model for agricultural irrigation and drainage processes were developed. Through multi-scenario simulations, the optimal spatial patterns of farmland were scientifically identified. Besides, a method for determining water consumption thresholds in semi-arid regions based on terrestrial water balance was proposed, underpinning the rational allocation of water resources for both agricultural and ecological purposes. Furthermore, a spatial connectivity analysis method considering migration routes and inhabitable zones for migratory bird species was proposed, accompanied by protection and restoration recommendations for wetlands in Northeast China.

-

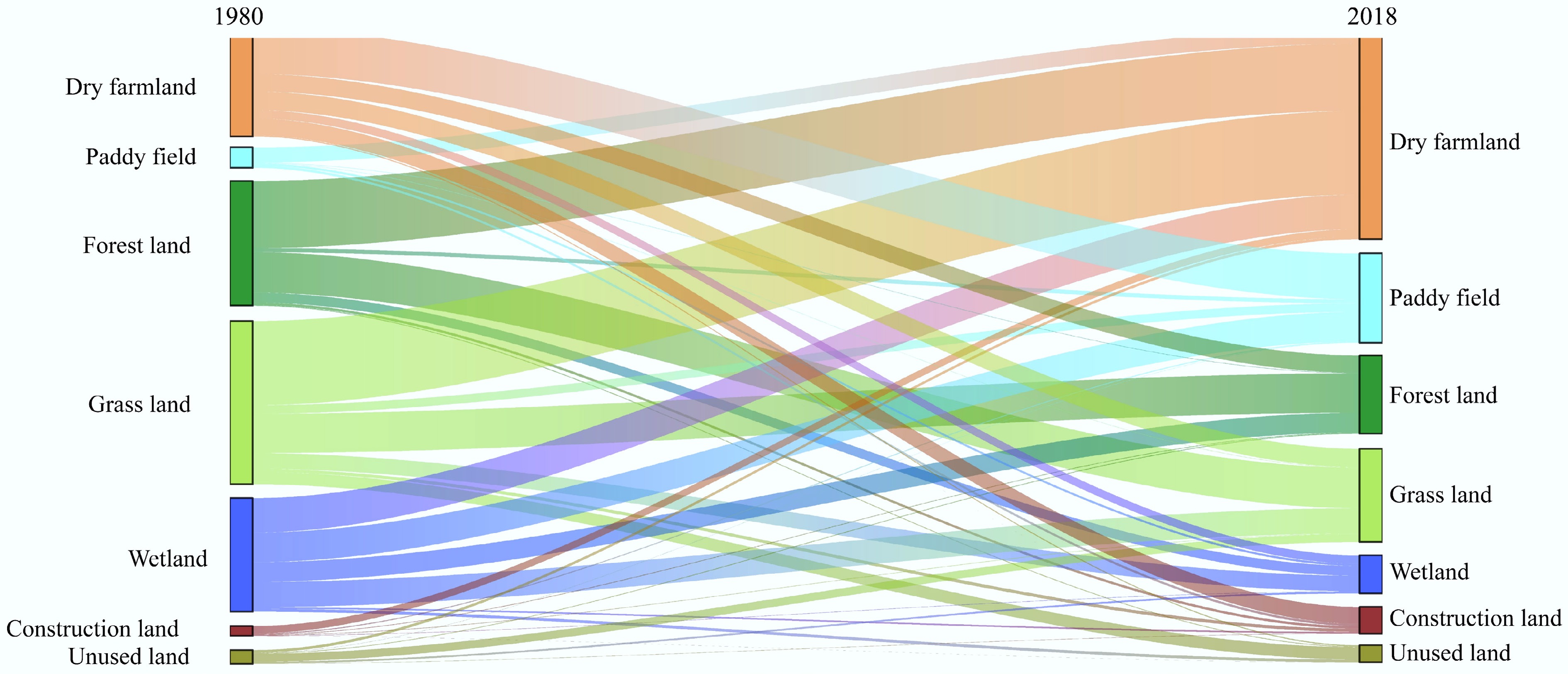

Based on land use data with a resolution of 30 m × 30 m for Northeast China from 1980 to 2018, the spatio-temporal changes in farmland and wetland areas were analyzed statistically. The findings revealed a significant reduction in wetland areas throughout Northeast China over the past 40 years. The total area of wetlands decreased from 98,600 km2 in 1980 to 71,600 km2 in 2018, representing a decline of 27.4%. Furthermore, the reduction in wetlands occurred mainly between 1980 and 2000, accounting for 90.2% of the total reduction during the entire study period. Spatially, the Songhua River Basin experienced the most substantial wetland loss, with a cumulative reduction of 26,500 km2—accounting for 98.1% of the overall wetland reduction in Northeast China. The most severely affected areas included lowland plains, particularly the Songnen Plain and the Sanjiang Plain.

The land use conversion analysis indicated that the primary factor contributing to the decline of the northeast wetlands was the encroachment of large-scale agricultural reclamation, as shown in Fig. 2. Based on land use changes in regions with wetland loss, it was found that 56.2% of these wetlands were transformed into farmland. Of these, 26.2% were specifically converted into paddy fields, and 30% were converted into dryland.

Excessive water use leading to river drying and groundwater decline

-

The expansion of farmland inevitably results in increased irrigation water consumption, causing intense water conflicts between agriculture and ecology. Northeast China receives relatively low annual precipitation, with a multi-year average of 530.4 mm. Most of the rainfall occurs during the flood season, with 60.4% of it concentrated between July and September. In contrast, the critical period for crop planting and tillering (April and May) receives only 67.7 mm of rainfall on average. The increase in cultivated land area has consequently led to a substantial escalation in irrigation requirements. In response to the increased demand for water, some regions have experienced excessive exploitation of water resources, which has contributed to the desiccation of rivers and the sustained decline of groundwater reserves[18].

Taking the Xiliao River Basin (XRB) as a case study, the challenges of competitive water utilization arising from agricultural reclamation and development were examined. The XRB covers an area of 138,000 km2, and is located in the core of the semi-arid farming-pastoral ecotone of Northeast China[19]. The region receives an average annual precipitation of only 391.7 mm, whereas the mean potential evapotranspiration is approximately 930.5 mm, demonstrating that evaporation substantially surpasses precipitation[20]. Known as China's 'Golden Corn Belt', the basin supports 18,600 km2 of dryland crop cultivation, primarily corn. In recent years, driven by the higher economic returns of rice, large-scale paddy fields have also been developed, dramatically increasing both the irrigated area and water consumption. From 2000 to 2018, the area planted with major grain crops—namely corn, wheat, and soybeans—increased substantially, expanding from 6,900 km2 in 2000 to 18,600 km2 in 2018, a 2.7-fold growth. Between 1980 and 2002, total water consumption in the basin rose from 2.31 billion to 5.35 billion m3. Since 2002, it has remained high, averaging around 4.85 billion m3 annually. The water resources development and utilization rate reached 97%, with agricultural water use accounting for nearly 90% of the total.

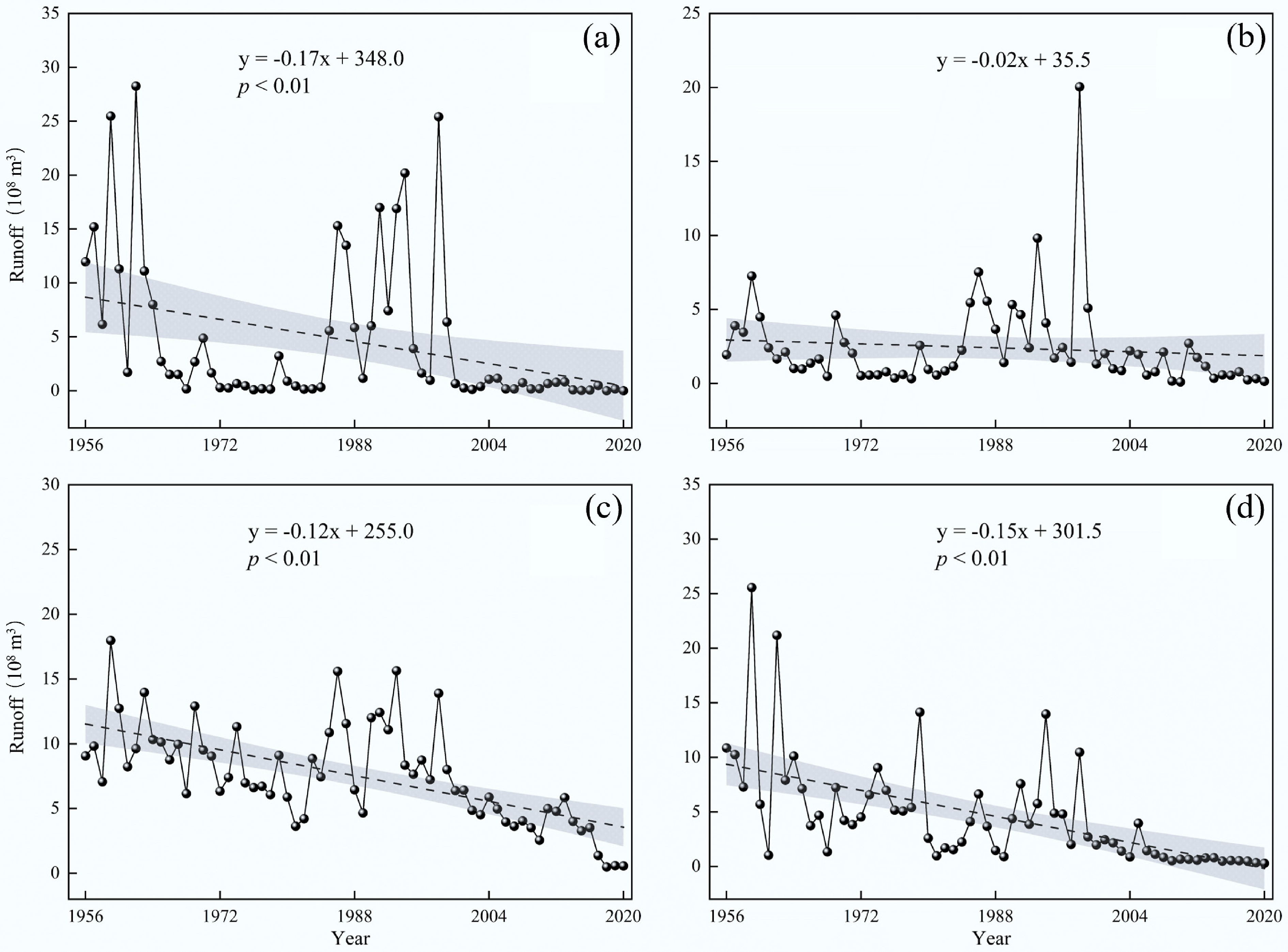

With the increase in water consumption, the runoff of the main stream and its tributaries in the XRB experienced a substantial decrease, resulting in frequent drying of the river. Among China's seven major river systems, the Xiliao River is now the only one in a persistently dry condition[21,22]. According to observed runoff data, the annual discharge in the Xiliao River's main channel declined significantly between 1956 and 2020, at a rate of 170 million m3 per year (p < 0.01), as shown in Fig. 3. Before 2000, the multi-year average runoff was approximately 880 million m3. After 2000, however, this figure dropped sharply to 52 million m3, representing a decline of over 94% and indicating a severe degradation of surface water availability. The runoff in the three principal tributaries of the Xiliao River—the Wulijimuren River, the Xar Moron River, and the Laoha River—also exhibited decreasing trends, with annual decreases of 20 million, 120 million, and 150 million m3, respectively.

Figure 3.

Trends in runoff changes for the main stream and its tributaries of the XRB from 1956 to 2020. (a) Represents the mainstream; (b), (c), and (d) represent the three major tributaries: the Wulijimuren River, the Xar Moron River, and the Laoha River, respectively.

Due to surface water shortages, widespread groundwater extraction has been used to meet agricultural water demands. This has led to a continuous decline in groundwater levels and the expansion of groundwater depression cones through the basin. For instance, within the Horqin District situated in the lower reaches of the XRB, the depth of groundwater exhibited a marked increase from 6.1 m in 2000 to 14.6 m by 2020, indicating considerable depletion of the aquifer[23,24].

Upstream water resources development resulting in the drastic reduction of wetland inflows

-

The majority of wetlands in Northeast China are situated either downstream or adjacent to rivers, relying heavily on the inflow of river water for their sustenance. The analysis presented in the preceding section indicates that agricultural reclamation and development are likely to cause a significant decrease in river runoff, consequently diminishing the water availability for wetlands. When the water supply cannot meet the ecological requirements of wetlands, ecological degradation becomes inevitable.

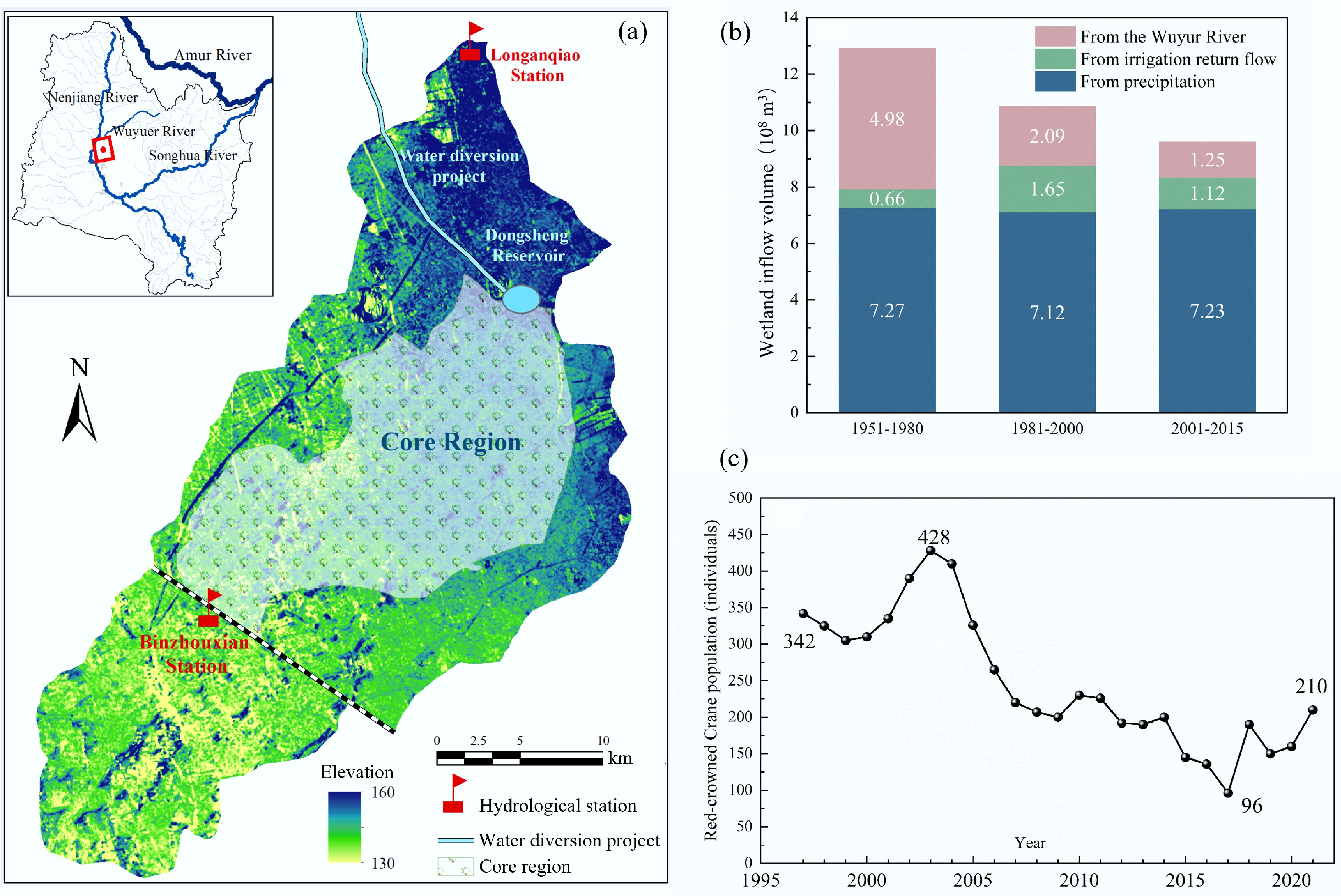

Taking the Zhalong Wetland (ZLW) as a case study, the impact of agricultural irrigation water consumption on wetland degradationn was further explored. The ZLW is the terminal wetland system of the Wuyu'er River, Northeast China's largest inland river, and harbors one of the country's most intact primitive wetland ecosystems (Fig. 4a). As a key staging area on the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, it has immense ecological significance for migratory birds and regional biodiversity. Since the 1980s, the combined effects of climate change and anthropogenic activities have markedly diminished runoff replenishment in the ZLM[25]. As illustrated in Fig. 4b, the average annual inflow of the Wuyu'er River into the ZLM decreased significantly, from 498 million m3 in the period 1951–1980 to merely 125 million m3 during 2001–2015[26]. This dramatic drop can be primarily attributed to extensive agricultural irrigation across the basin. The cultivated land area expanded from 8,630 km2 in the 1980s to 9,528 km2 in the 2010s. Additionally, over 40 reservoirs and diversion projects currently extract more than 350 million m3 of water annually[27], substantially diminishing the water resources that historically supported the ecosystems of the ZLW.

Figure 4.

(a) Location of Zhalong Wetland. (b) Changes in water source recharge characteristics, and (c) population of wild red-crowned cranes.

The decrease in river inflow has resulted in a significant contraction of wetland surface area. Concurrently, prolonged drought conditions and persistent water scarcity within the wetlands have expedited the transformation of marshlands into secondary saline-alkali soils. According to the present findings, the area of native reed marshes in the ZLW decreased by 130 km2 between 1980 and 2010. Conversely, salinized soils expanded from 150 km2 in 1979 to 260 km2 in 2017, over 30% of which occurred within core wetland zones[28]. The reduction of wetland areas and the increase in soil salinization have led to significant habitat degradation, particularly impacting rare waterbird species such as the Red-crowned Crane (Grus japonensis). Vegetation surveys revealed that by 2015, reed coverage had declined by 50% relative to levels observed in the 1980s, while the landscape connectivity for key habitats had become significantly fragmented[29]. Consequently, the wild crane population declined sharply from approximately 400 individuals to fewer than 100, reflecting a significant deterioration in ecological function and an increased risk to regional ecological security, as shown in Fig. 4c[28].

Irrigation and drainage infrastructures alter flood regimes in marshy riverine wetlands

-

Beyond the displacement of ecological water consumption, agricultural irrigation further interferes with the inflow dynamics of wetlands via irrigation and drainage infrastructures. To meet agricultural irrigation demands and improve water management efficiency, large-scale irrigation and drainage infrastructure has been extensively developed in Northeast China. The continued expansion and upgrading of these systems—including irrigation canals, drainage ditches, flood diversion channels, and pumping stations—has notably enhanced flood and drought control capacities within farmlands. However, these highly engineered water systems have also substantially disrupted natural runoff generation and concentration processes, leading to altered flood dynamics in both irrigated areas and downstream marshy wetlands. Under natural subsurface conditions, the soil and vegetation of marsh wetlands efficiently absorb and store precipitation, moderating the generation and concentration of surface runoff. In contrast, irrigation and drainage infrastructure accelerate water discharge from fields by reducing soil retention capacity and shortening water residence times. Runoff is further concentrated by active drainage operations that rapidly remove ponded water from farmland. These modifications result in higher peak discharges and increased total flood volumes, while reducing baseflow during dry periods. This artificially accelerated runoff response causes sudden river flow surges following rainfall events, particularly during the flood season. Consequently, flood frequency and intensity in adjacent marsh wetlands have significantly increased. In areas with insufficient drainage capacity, these rapid hydrologic shifts often trigger ecological stress—manifesting as both prolonged inundation and erratic flooding-drought cycles—which compromises wetland health.

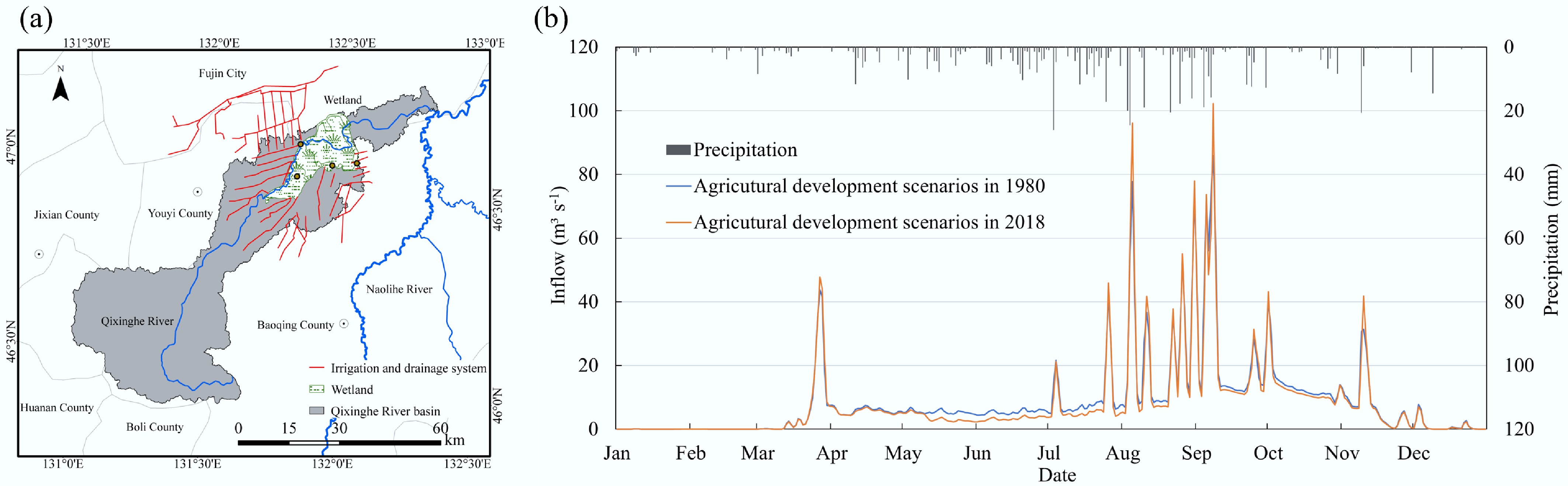

The Qixing River Basin (QRB), located in the heart of the Sanjiang Plain, serves as a typical example of these impacts. Decades of large-scale agricultural development have led to a shrinkage in its lower reaches. Multi-stage irrigation and drainage systems—including main channels, branch ditches, flood diversion conduits, and retention structures—have fundamentally altered hydrological processes in the basin. To elucidate the effects of agricultural irrigation and drainage infrastructure on the runoff dynamics within the QRB, a coupled hydrological-hydrodynamic model was developed. According to field observations and model simulations (Fig. 5), the wetland inflow regime in 2018 (under intensive agricultural development) differed significantly from that in 1980 (under natural conditions). Between May and late July of 2018, the inflow was significantly reduced, reaching a minimum discharge of only 2.26 m3 s–1, and exhibiting a prolonged period of low flow. However, by the end of July, during peak flood season, inflows increased abruptly—reaching a maximum flow of 102.3 m3 s–1, which represents a 19.1% increase relative to the levels recorded in 1980. Although total wetland inflow declined from 291 million m3 in 1980 to 263 million m3 in 2018, the volume of floodwater experienced an increase from 140 million to 165 million m3. The daily flow fluctuation ratio rose from 16 to 31, indicating heightened variability and intensity in flow patterns. These abrupt and intensified alterations in inflow dynamics have resulted in rapid increases in water levels, followed by slow recessions. Consequently, this has extended the duration of habitat submergence and contributed to the degradation of essential wetland environments.

Figure 5.

(a) The irrigation and drainage systems of QRB. (b) The daily flow into wetlands under different agricultural development scenarios.

Reduced hydrological connectivity of wetlands leads to habitat fragmentation

-

From the perspective of agricultural-ecological spatial patterns, the expansion of agricultural areas, along with the development of irrigation and drainage infrastructure, has led to significant fragmentation of wetland habitats in Northeast China[30]. These impacts are mainly reflected in two aspects: (1) reduced longitudinal river connectivity, which has severely compressed spawning habitats for migratory fish species such as chum salmon[31]; and (2) increased fragmentation of wetland systems, both within and between wetland areas, which have dramatically reduced suitable habitats necessary for species migration and habitation[32].

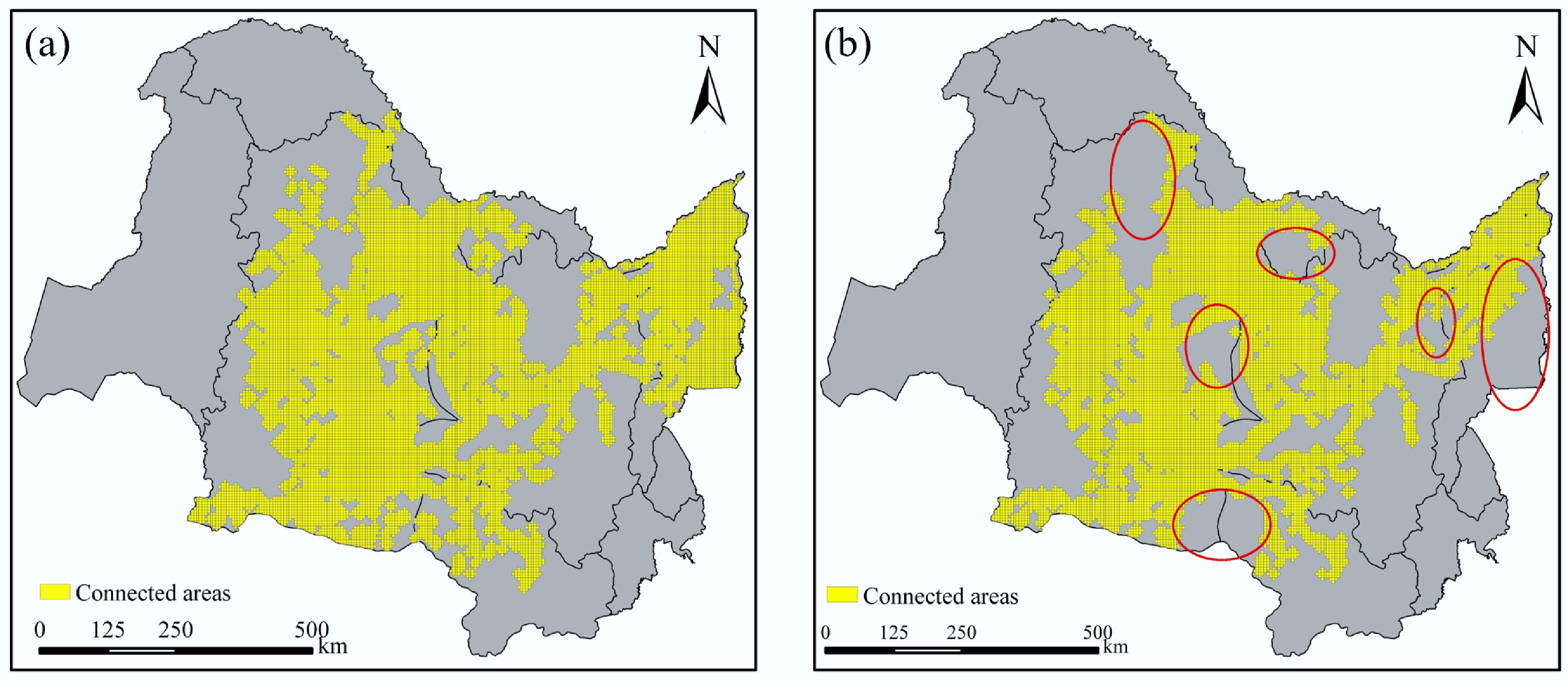

Taking the Songhua River Region (SHJR) as a case study, longitudinal data from 1980 to 2018 indicated a 33.8% reduction in the largest hydrologically-connected wetland patch, decreasing from 41.9% to 27.8%. Using 40 km, the average single-flight range of the Red-crowned Crane, as the threshold distance for assessing Stereoscopic Spatial Connectivity (SSC) among wetlands, the Stereoscopic Spatial Connectivity Index (SSCI) was calculated[33]. Over the past four decades, the SSCI in the SHJR decreased from 41.3% to 35.1% (Fig. 6). The decline was especially prominent in areas undergoing intensive agricultural development, such as the Sanjiang Plain, Songnen Plain, and the periphery of Xingkai Lake. The reduced SSCI indicates the formation of numerous 'ecological islands', significantly limiting viable migration routes and habitable zones for migratory bird species, especially Red-crowned Cranes.

-

The Wetlands Protection Law of the People's Republic of China (2022) stipulates stringent regulations on the overall wetland area and enforces rigorous limitations on the utilization of wetland resources. Supplementary regulations, including the Wetlands Protection and Management Regulations, underscore the principles of 'compensation before requisition', and maintaining a 'balance between requisition and compensation' to avert the net loss of wetlands and safeguard their ecological functions. In practical applications, natural wetlands that are appropriated are frequently substituted with artificial wetlands. Nonetheless, constructed wetlands generally exhibit substantially reduced ecological functionality compared to natural wetlands, particularly regarding water purification, climate regulation, and the conservation of biodiversity[34]. For instance, the conversion of 0.01 km2 of Red-crowned Crane nesting habitat frequently results in the deterioration of neighboring regions and ecological corridors. Consequently, the area of compensatory wetlands should surpass that of the lost habitat to ensure the restoration of ecological integrity at the landscape scale. Functional Equivalence Assessment is critical to evaluating whether constructed wetlands can match the ecological functions of natural wetlands[35]. We advocate for the implementation of legally mandated quantitative criteria for functional equivalence, thereby ensuring that compensation measures adequately account for both the spatial extent and the ecological integrity of wetlands.

The wetland requisition-compensation balance system can be implemented through in-situ restoration or off-site reconstruction, with the objective of achieving functional equivalence. In cases where complete restoration of ecosystem services is unattainable, economic compensation can serve as an auxiliary strategy. An effective strategy involves the establishment of a wetland banking system, in which developers purchase wetland credits to fund off-site restoration through accredited agencies[36]. China is still in the pilot phase of establishing wetland banking and is working to improve the associated legal and institutional frameworks[37]. The expansion of pilot programs in Northeast China may facilitate the accelerated adoption and enhanced efficacy of this mechanism.

Controlling agricultural reclamation scale and total water consumption

-

To mitigate the ecological degradation resulting from excessive water use in irrigation, it is essential to determine an appropriate threshold for agricultural water consumption. This measure is necessary to regulate and prevent the unrestrained expansion of agricultural activities. We have proposed a technical framework for determining water consumption thresholds in semi-arid regions based on terrestrial water balance. The technical framework includes three parts: adaptability-based evaluation and selection of remote sensing products, calculation of agricultural and ecological water consumption, and determination of water consumption thresholds[38]. Furthermore, this method was applied to the XRB to establish a threshold for agricultural water consumption and identify the optimal scale of cultivation.

Using data on precipitation, evapotranspiration, runoff, and terrestrial water storage from 1980 to 2020, along with water balance modeling and multiple linear regression analysis, the relationship between agricultural water consumption and terrestrial water storage in the XRB was quantified. The analysis identified critical thresholds for agricultural water consumption required to stabilize terrestrial water storage. In areas dominated by agricultural water consumption, the consumption of water should account for 47.3%–63.1% of the annual precipitation. In areas where both agricultural and ecological demands are significant, the aggregate water consumption should be constrained to a range of 49.9% to 62.7% of the annual precipitation[38].

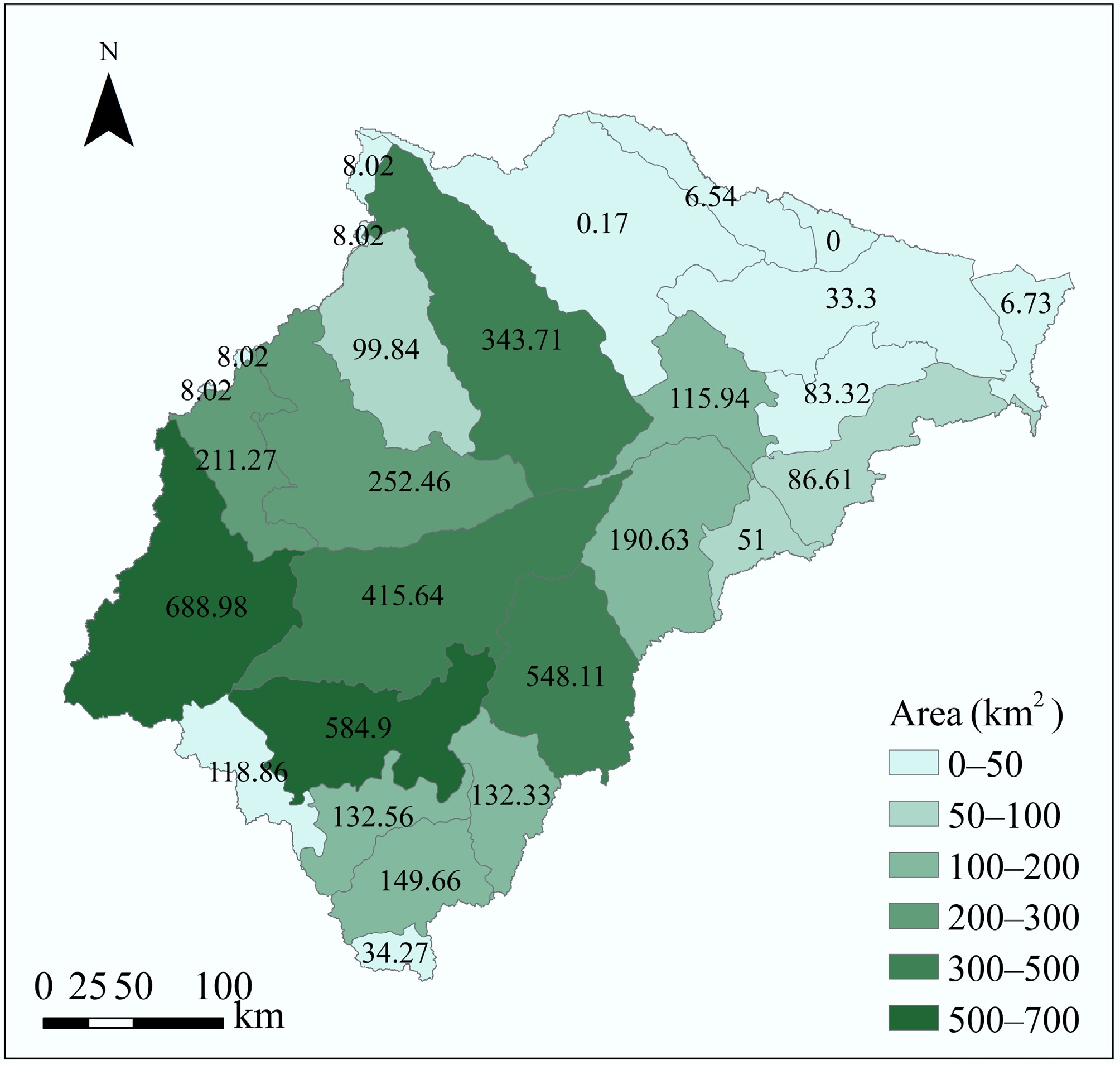

From 1980 to 2020, 21 of the 24 counties in the XRB exhibited persistent deficits in terrestrial water storage due to excessive water consumption for agricultural irrigation. Consequently, it is imperative to limit the agricultural reclamation scale and total water consumption to facilitate the restoration of terrestrial water storage and maintain water balance. According to our findings, converting each unit area of cropland to grassland in the XRB results in an approximate reduction of water consumption by 100 mm. To achieve the goal of replenishing terrestrial water storage, the farmland area needs to be reduced by 4,278 km2, accounting for 11.46% of the current total farmland area. Priority in optimizing and reducing the scale of cultivation should be assigned to the 21 counties and districts experiencing sustained water shortages (Fig. 7). Finally, additional analyses concerning the economic challenges that could result from the decrease in the area of farmland were performed. The government's annual compensation standard for converting farmland to grassland is approximately CNY 600,000 per km², resulting in a total compensation amount of CNY 2.57 billion. This amount represents 0.67% of the region's annual gross domestic product (GDP). Consequently, the strategy of converting farmland back to grassland is a viable option.

Establishing a sustainable water replenishment mechanism for wetlands

-

Ecological water replenishment (EWR) has become a key strategy for wetland restoration in Northeast China, playing a vital role in maintaining water levels, improving water quality, enhancing hydrological connectivity, and restoring habitat functionality[38].

As exemplified by the ZLW, the EWR measure has been implemented since 2001 and has yielded significant outcomes. In that year, the project was launched to divert water from the Nenjiang River to replenish the ZLW, with an initial water diversion volume of approximately 460 million m3. By 2022, the total volume of water replenished had accumulated to 3 billion m3[27]. As a result, the water surface area in the core zone of the ZLW expanded from 300 to 700 km2, and reed marshes recovered to an area of 600 km2. In recent years, Northeast China has initiated a series of EWR projects for wetlands. As the scope of wetlands receiving EWR progressively increases, the imperative to establish a scientific and efficient water replenishment mechanism capable of sustained regular operation becomes increasingly critical.

Two main technical challenges hinder the regularization of EWR: determining the optimal spatiotemporal allocation of replenishment volumes and designing efficient replenishment pathways. We proposed that water resource allocation should be informed by habitat evaluations of indicator species (e.g., waterbirds, fish) to identify appropriate water levels across seasonal periods. Additionally, the design of water replenishment pathways depends on assessing wetland hydrological connectivity, which enables targeted zonal replenishment. In the ZLW, eco-hydraulic modeling alongside species-specific response analyses was employed to assess the effects of varying water regimes on essential habitats. Furthermore, a quantitative analysis was performed to examine the dynamic response relationship between fluctuations in water levels and the suitable habitat areas of key species, including red-crowned cranes, reeds, and fish, within the ZLW. Ultimately, a seasonal water level regulation plan for the ZLW was developed, incorporating considerations of the red-crowned cranes' breeding period, the reed sprouting phase, and the fish wintering season. The phased strategy directs concentrated water releases from May to June to address ecological water shortages and ensure crane nesting habitat. A second phase from September to October supports overwintering needs for aquatic species and maintains water conditions for the following year.

To improve replenishment efficiency, a zoning methodology based on hydrologic connectivity was developed using water-level dynamics across spatial grids. The process consists of three integrated phases:

• Phase 1: A two-dimensional hydrodynamic model simulates daily water-level changes. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is applied to extract dominant spatiotemporal patterns.

• Phase 2: Modelling outputs are clustered to delineate functionally distinct hydrologic zones, each with customized replenishment strategies[28].

• Phase 3: Thresholds for early warning and adaptive regulation are set using hydrologic frequency analysis or morphometric data. Real-time monitoring is enabled via telemetric sensors at key control points.

This approach enables dynamic monitoring and precision water management, improving replenishment efficiency and sustaining optimal ecological water conditions.

Optimizing the spatial arrangement of farmland and wetlands within the basin

-

Agricultural development alters the natural land surface and drainage processes, thereby affecting runoff generation and concentration mechanisms, which in turn affect the stability of wetland ecosystems. Defining and maintaining a scientifically sound spatial arrangement between farmland and wetlands is crucial for safeguarding ecological integrity and advancing sustainable development.

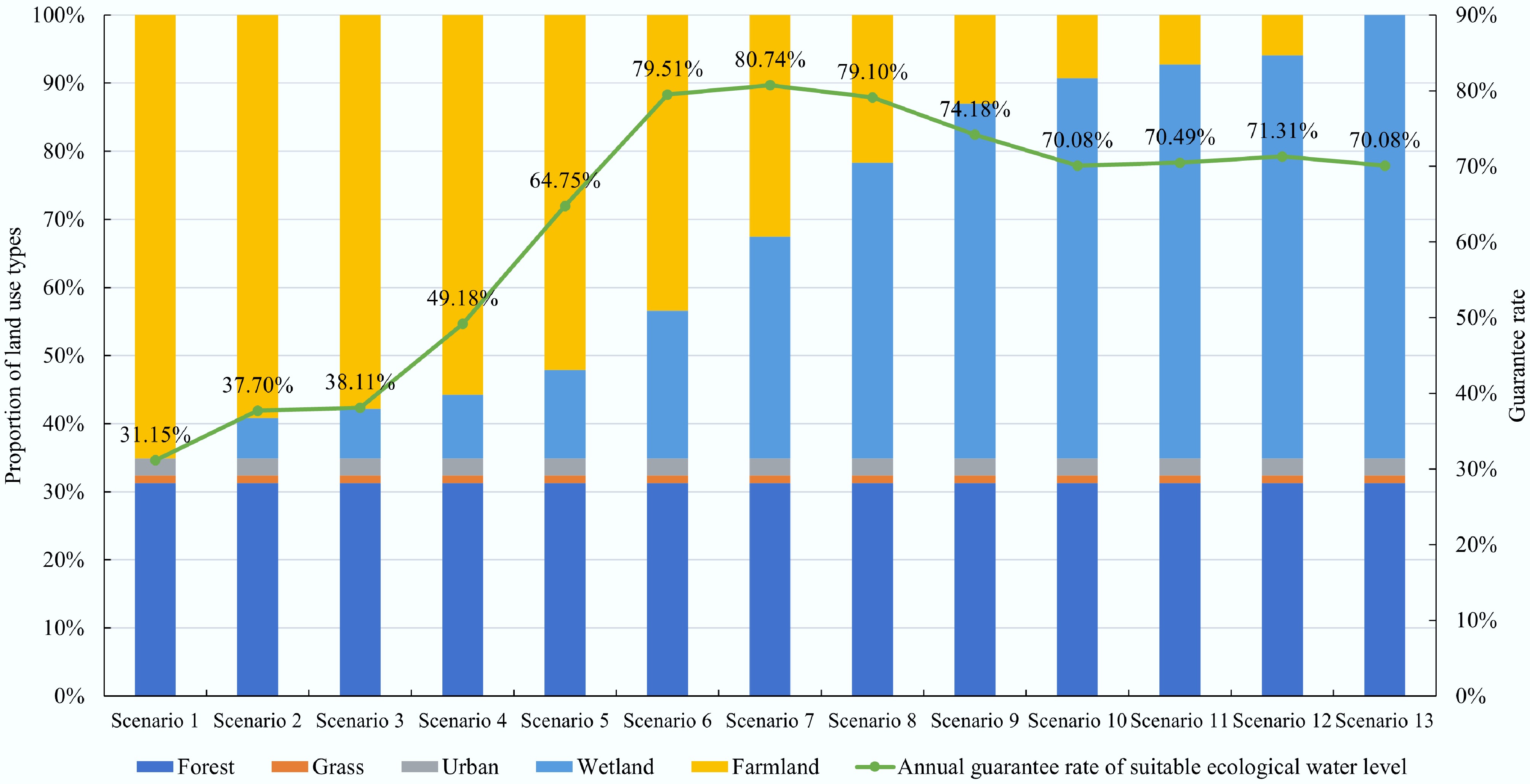

In the QRB, a coupled hydrological-hydrodynamic model was developed and validated. To examine the effects of variations in farmland-wetland spatial patterns on runoff, 13 distinct scenarios were designed. In each scenario, the proportions of forest, grassland, and urban land were held constant, while the relative ratios of farmland and wetlands were systematically modified. The study encompassed two boundary conditions: complete conversion of wetlands to farmland, and the complete conversion of farmland to wetlands. Intermediate scenarios involved varying the ratios of farmland to wetland (such as 10:1, 8:1, 1:10, and 1:8), culminating in a total of 13 configurations (Table 1). Using the developed hydrological-hydrodynamic model of the QRB, we systematically simulated the variability of basin runoff across these 13 distinct scenarios. These simulations employed meteorological data from a representative average water year within the QRB as input parameters. Based on the simulation outcomes, an optimized land use pattern for the QRB was proposed[39].

Table 1. Proportion of land use types under different scenarios in the QRB

Scenario Farmland Forest land Grassland Townland Wetland Farmland/

wetland1 65.08% 31.26% 1.12% 2.54% 0.00 All farmland 2 59.16% 31.26% 1.12% 2.54% 5.92% 10:1 3 57.85% 31.26% 1.12% 2.54% 7.23% 8:1 4 55.78% 31.26% 1.12% 2.54% 9.30% 6:1 5 52.06% 31.26% 1.12% 2.54% 13.02% 4:1 6 43.39% 31.26% 1.12% 2.54% 21.69% 2:1 7 32.54% 31.26% 1.12% 2.54% 32.54% 1:1 8 21.69% 31.26% 1.12% 2.54% 43.39% 1:2 9 13.02% 31.26% 1.12% 2.54% 52.06% 1:4 10 9.30% 31.26% 1.12% 2.54% 55.78% 1:6 11 7.23% 31.26% 1.12% 2.54% 57.85% 1:8 12 5.92% 31.26% 1.12% 2.54% 59.16% 1:10 13 0.00 31.26% 1.12% 2.54% 65.08% All wetland Based on the suitable ecological water level thresholds of the wetland in the QRB, the wetland water level process under 13 scenarios was evaluated, and the ecological water level assurance rate of the core area of the wetland under each scenario was evaluated for the four time periods—April–May, June–August, September–October, and November—as well as for the whole year. The results showed that increasing wetland area led to a steady improvement in the ecological water level guarantee rate, initially rising, and then leveling off (Fig. 8). After scenario 6, the guarantee rate stabilized above 70%, reaching a peak of approximately 80% between scenarios 6 and 8. This indicated that these configurations can support relatively optimal ecological water regimes in the QRB. However, further expansion of wetlands beyond this point led to a decrease in the downstream guarantee rate, primarily due to insufficient water usage upstream. This caused excessive water retention in wetlands, leading to prolonged inundation and increased swamping. Currently, the Sanjiang Plain—where the QBR is located—is one of China's major grain-producing regions, characterized by a farmland-to-wetland ratio of 3.7:1. The simulation analysis suggested that a ratio of 2:1 for the QBR is more sustainable and ecologically balanced.

Figure 8.

The relationship between the proportion of land use types and the guarantee rate of suitable ecological water level.

Protection and restoration of critical wetlands areas

-

Over the past 40 years, Northeast China has experienced a sharp decline in wetland areas, leading to the emergence of an 'ecological island' phenomenon. Considering the difficulties associated with large-scale and comprehensive restoration of natural wetlands, it is imperative to employ scientific methods to identify and prioritize critical areas for protection and restoration. Focused interventions within these domains have the potential to optimize the restoration of wetland ecological functions and enhance the overall efficacy of restoration initiatives.

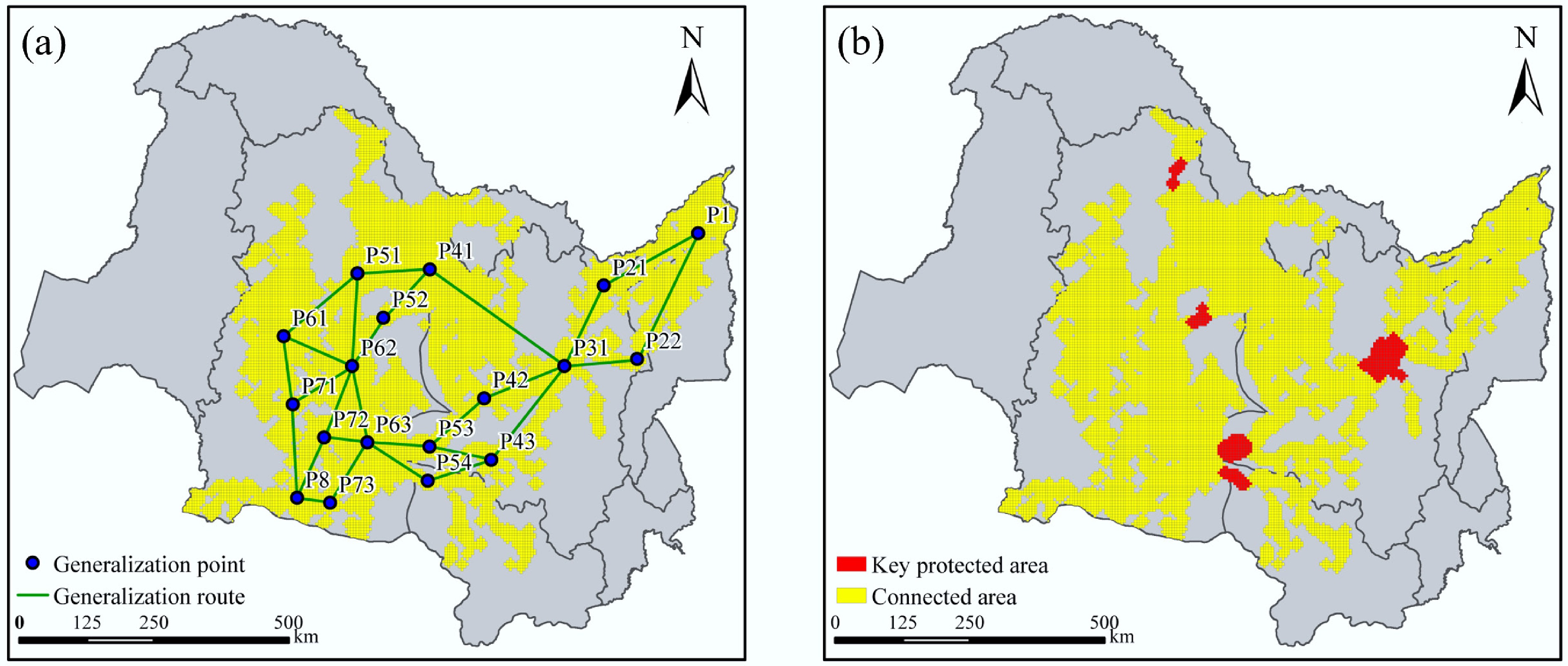

The distribution requirements of wetland patches in the habitat and migration of migratory birds were considered, and the integrity and connectivity of wetlands in Northeast China analyzed. By assessing how typical migratory birds' habitat and migration behaviors depend on intra-wetland and inter-wetland connectivity, critical wetland regions that warrant prioritized conservation and restoration efforts were delineated, and proposed regulatory measures to enhance wetland connectivity.

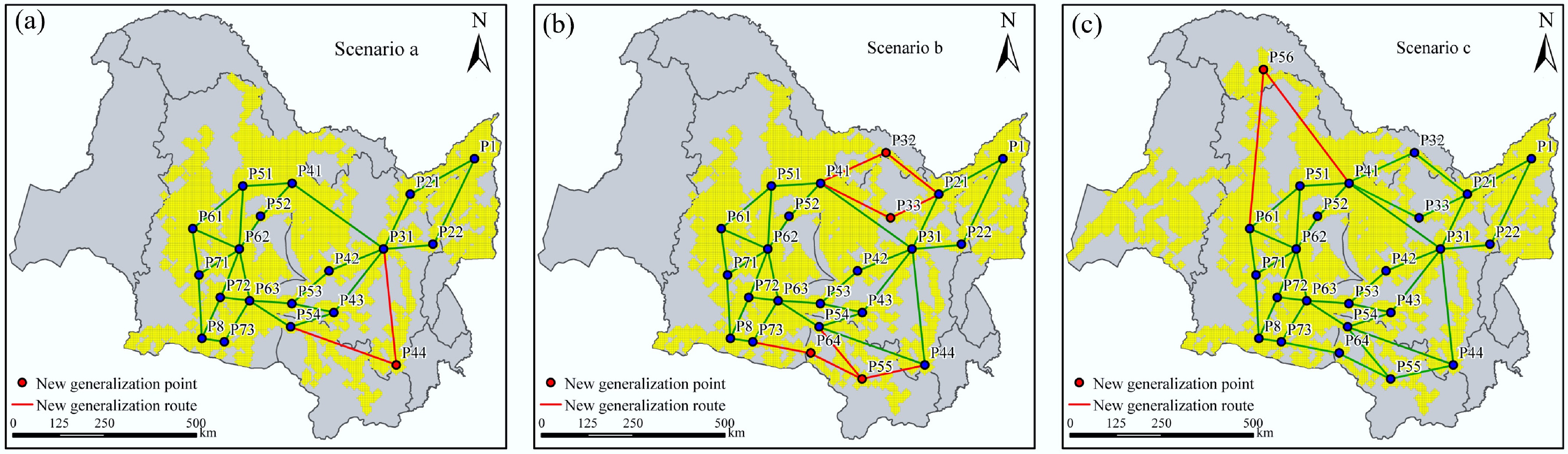

According to the current distribution of wetlands in the SHJR, the Generalized Routes (GRs) of typical migratory bird habitats and migration pathways were mapped in Fig. 9a. As a result, a total of 60 connectivity corridors within wetland areas have been identified. Based on these corridors, along with regional distribution patterns and the functional needs of wetland ecosystems, five key conservation zones were designated (Fig. 9b). These areas are predominantly situated in the vicinity of the Songnen Plain and the main stem of the Songhua River, corresponding to the habitat criteria established by the GRs for typical migratory birds.

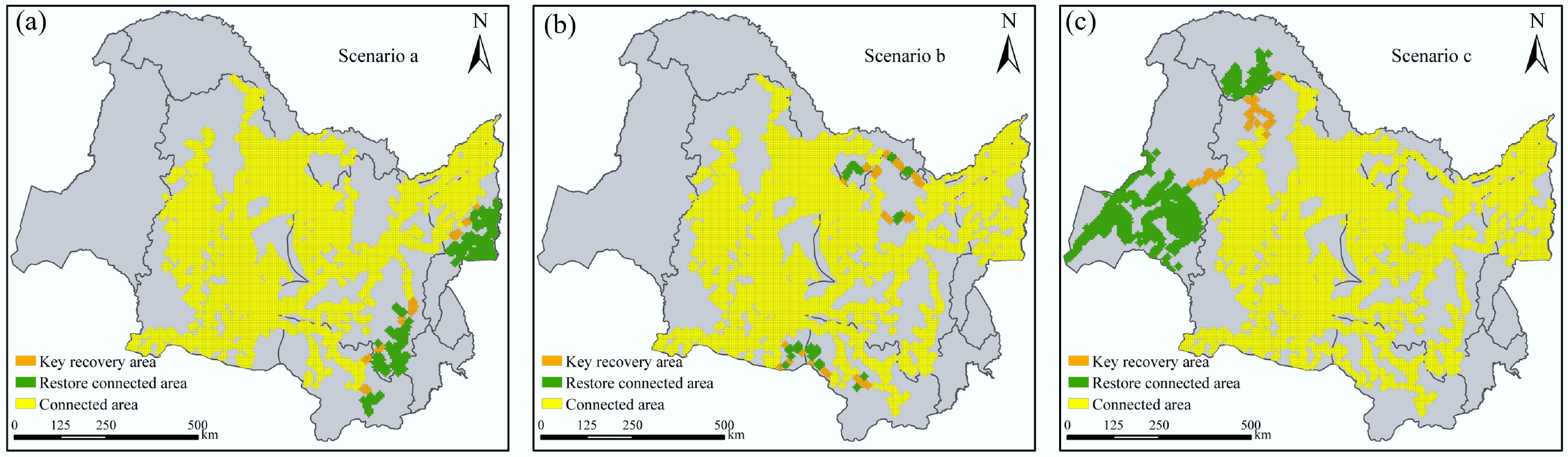

To guide restoration, three scenarios—high, medium, and low feasibility—were developed, and their outcomes are illustrated in Figs 10 and 11. In the high-feasibility scenario (scenario a), the restoration of 0.5 km2 of wetlands in critical locations within the Sanjiang Plain, the Second Songhua River Basin, and the Mudanjiang River Basin had the potential to increase the SSCI value from 35.1% to 38.7%. The medium-feasibility scenario (scenario b) involved the restoration of wetlands along the main river basins of the Heilongjiang and Songhua Rivers. This intervention was projected to enhance GR coverage in the northern, central, and southern parts of the Heilongjiang Basin, increasing the SSCI value to 40.6%. The low-feasibility scenario (scenario c) concentrated on establishing a connection between the Nenjiang and Erguna River Basins, which could potentially increase the SSCI value to 47.6%. However, this would require restoration in the river's headwater regions, which presents significant challenges. Considering current constraints, the medium-feasibility scenario was recommended as the preferred approach for wetland restoration in the SHJR. Implementation of this scenario is projected to restore the SSCI value of the SHJR to a level comparable to that recorded in 1980.

-

Northeast China serves as a fundamental pillar for the nation's food security and functions as a critical ecological barrier, reflecting the intrinsic conflict between constrained land and water resources and the increasing multifunctional demands placed upon them. This conflict has resulted in a range of issues, such as the reduction of river marsh wetlands, the drying up of rivers, and the fragmentation of habitats. Consequently, this study utilized a comprehensive methodological approach—including literature review, remote sensing interpretation, and model simulation—to systematically elucidate the core tensions between agricultural development and ecological protection in Northeast China. Furthermore, a comprehensive regulatory strategy was proposed to balance the resource and spatial demands of both agriculture and ecology.

Compared with traditional research, this study has the following innovations: (1) To address the challenge of balancing agricultural and ecological water use, a novel approach was proposed to establish water consumption thresholds based on terrestrial water balance. This method effectively quantifies agricultural water use and identifies appropriate farmland scales within the XRB. (2) To reconcile ecological water demand with water supply in wetlands, we innovatively incorporated the integrated irrigation and drainage systems within a distributed hydrological and hydrodynamic model. This approach elucidated the influence of agricultural activities on the flooding dynamics of wetlands and facilitated the appropriate spatial scales for agriculture and wetland. (3) To mitigate habitat fragmentation resulting from agricultural expansion, we proposed an assessment and regulation technique of SSC for wetlands, tailored to the habitat characteristics and migratory requirements of typical migratory bird species in Northeast China.

However, this study provides only a preliminary exploration of the competitive and balanced dynamics between agriculture and ecology in Northeast China, with certain limitations evident in both the methodology and the findings. For instance, regarding the habitat and migration requirements of migratory bird species, we only considered wetland size as an evaluation criterion. Other factors, including water depth, vegetation distribution, and proximity to anthropogenic activities within the area, should be examined in future research to enhance the precision of the SSC assessments in regional wetland ecosystems. Besides, the seasonal water replenishment strategy, designed to accommodate the requirements of various organisms such as red-crowned cranes, fish, and reeds across different seasons, requires further refinement to enhance the efficacy of wetland water restoration.

New opportunities under the water network construction

-

China is accelerating the construction of the national water network to address the uneven spatial distribution of water resources and enhance the country's water security. The water network in Northeast China is an important part of the national water network and serves as an important measure for addressing the conflicts between agricultural development and ecological protection in the future. Water diversion infrastructure facilitates the transfer of water from rivers characterized by substantial runoff, including the Heilongjiang River and the Yalu River, to rivers and wetlands experiencing water scarcity, such as the XRB, QRB, and ZLW.

Currently, a notable example of water network construction in Northeast China is the 'Three Rivers Interconnection' project, which encompasses the Heilongjiang, Songhuajiang, and Ussurijiang rivers. The project leverages the existing natural river systems, as well as irrigation and drainage channels, to divert water from the Heilongjiang River to the Songhua River basin. Subsequently, water is transferred from the Songhua River basin to the Naolihe River basin, a tributary of the Ussurijiang River located centrally within the Sanjiang Plain. As a result, a water resource distribution network encompassing an area of 17,000 km2 has been established.

Conclusions

-

Northeast China is experiencing significant ecological challenges as a result of extensive agricultural reclamation. To effectively address these challenges, the implementation of integrated strategies is imperative. Essential strategies encompass the establishment of the requisition-compensation balance system for wetlands, the regulation of agricultural reclamation intensity, the management of irrigation water consumption, the optimization of the spatial arrangement of farmland and wetlands, and the restoration of critical wetland areas.

It is important to acknowledge that, owing to constraints in the authors' expertise and the inherently elevated humus levels in the region's aquatic environments, this study did not undertake a comprehensive evaluation of non-point source pollution originating from agricultural activities or its associated ecological effects.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design, manuscript revision: Hu P, Yang Z, Liu H, Yang Q, Wang X, Yuan X; material preparation, data collection and analysis: Yang Z, Liu H, Yang Q, Wang X, Yuan X; draft manuscript preparation: Hu P. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFF1300902), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52394233), the Independent Research Project of State Key Laboratory (WR110146B0022024; WR110145B0102025), and the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST (2023QNRC001).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Peng Hu, Zefan Yang

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Hu P, Yang Z, Liu H, Yang Q, Wang X, et al. 2025. Core tensions and integrated strategies for balancing agricultural development and ecological protection in Northeast China. Agricultural Ecology and Environment 1: e008 doi: 10.48130/aee-0025-0008

Core tensions and integrated strategies for balancing agricultural development and ecological protection in Northeast China

- Received: 09 July 2025

- Revised: 29 August 2025

- Accepted: 20 September 2025

- Published online: 13 October 2025

Abstract: Northeast China serves as a crucial grain production base and ecological security barrier, playing an essential role in ensuring national food security and maintaining ecosystem stability. However, extensive land reclamation and intensive water resource exploitation have gradually weakened the region's ecological functions. This study revealed the critical challenges between agricultural expansion and ecosystem conservation, including the encroachment upon riverine wetlands, reduction in wetland water inflows, alterations of natural hydrological patterns, depletion of groundwater resources, and fragmentation of aquatic habitats. Moreover, the study introduced novel methodologies for hydrological and hydrodynamic modeling, determining agricultural and ecological water consumption thresholds, and assessing ecological connectivity. These approaches offer critical support for the rational resource allocation and spatial distribution of agriculture and ecology. In conclusion, a comprehensive set of regulatory strategies was proposed, including the establishment of a wetland compensation mechanism; the rational regulation of agricultural reclamation scale and total water consumption; the optimization of the spatial distribution of farmland and wetlands; the development of an efficient and systematic water replenishment mechanism for wetlands; and the protection and restoration of priority areas of wetlands. Importantly, the methodologies and findings possess considerable potential for application to analogous river basins.