-

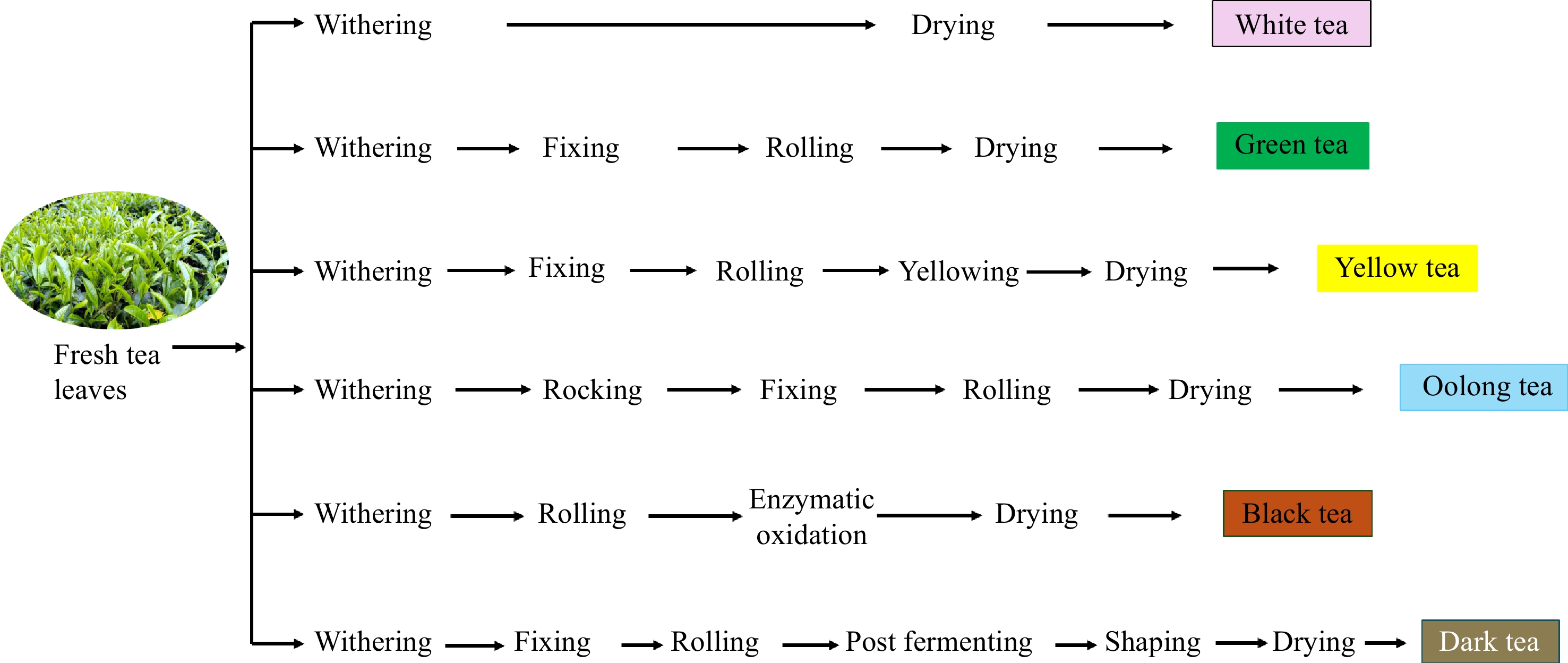

Tea is the most consumed beverage after water, known for its bioactive compounds that benefit human health. According to the International Tea Committee (ITC), China, India, and Kenya are the main tea producers, contributing to 68% of the total tea production[1]. It is widely known that tea is classified as green, oolong, and black tea according to the degree of oxidation. Additionally, six types of tea are classified by their processing methods: white tea, green tea, yellow tea, oolong tea, black tea, and dark tea (Fig. 1). Each processing method influences the appearance of tea, the color of the infusion, and the profile of bioactive compounds[2].

Freshly plucked tea leaves contain 75%−80% moisture content. These leaves undergo several processing stages depending on the desired final product[3]. Withering is the initial stage in tea processing, which aims to reduce the water content in fresh tea leaves, causing them to wilt and soften for subsequent processing steps[4]. During the withering process, complex chemical compounds in tea leaves degrade to simple active compounds such as amino acids, simple sugars, increased enzyme activity, and caffeine, while also forming volatile compounds[5]. This process creates a balance of flavors and aroma, enhancing the taste and color of the infusion and significantly influencing the quality of the tea product. However, withering also causes tea leaves to be exposed to extreme stress, such as mechanical injuries, sun exposure, temperature fluctuations, air heat, and dehydration. Oxidative stress occurs when the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in leaves exceed antioxidant defense capacities, damaging cellular components such as lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, and causing various physiological changes in leaves[6,7].

As a secondary metabolite, flavonoids are essential bioactive compounds that contribute to the quality of tea. Flavonoids are generally divided into several groups, including flavones, flavanols (flavan-3-ols), flavanones, flavonols, anthocyanins, and isoflavones[8]. Among these, flavonols are the predominant flavonoids found in tea after flavan-3-ol. Approximately 13% of flavonols and glycosides are found in fresh tea leaves[9]. The main flavonols in tea leaves are quercetin, myricetin, and kaempferol, found mainly as O-glycosides with a glycoside moiety at the C-3 position[10]. These compounds are key contributors to the astringent taste and red-brown color of tea infusion[11]. Furthermore, flavonols exhibit antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities that contribute to the health benefits of tea[12,13]. They also improve the plant's defense against ROS, as responsible for mitigating environmental stress[6].

Despite the importance of the withering process in tea production, many research areas remain unexplored regarding the role of flavonol glycosides during this process. Therefore, this review aims to understand the role of flavonol glycosides during the withering process and their effects on the biochemical properties and quality of tea. Firstly, it presents an overview of current knowledge on the withering process and flavonol glycosides, highlighting the technology applied and their role in improving tea quality. Subsequently, it offers the main role of flavonols and flavonol glycosides in mitigating oxidative stress in leaf cells during withering. Finally, the review discusses existing research gaps and suggests future research directions to enhance tea quality through the withering process.

-

As shown in Fig. 1, withering is the initial stage of tea processing, which aims to reduce the moisture content at a constant rate. This stage marks the beginning of the transformation from fresh leaf to finished tea and involves both physical (loss of moisture) and biochemical (enzyme activation, breakdown of complex molecules) changes. Understanding and optimizing the withering process is essential to produce high-quality tea consistently. During withering, the tea leaves become wilted and softened, and their color gradually darkens[4]. The concentration of sap within the tea leaf cells increases, causing the turgid leaves to become flaccid. Complex chemical compounds are degraded to simpler compounds, producing volatile flavor compounds, amino acids, and simple sugars. Furthermore, withering also improves enzyme activity and increases caffeine concentration[4,5]. Table 1 summarizes recent research on the withering process and its impact on biochemical changes and tea quality. Key withering factors such as duration, temperature, humidity, airflow, leaf maturity, and light significantly influence both physical and chemical transformations in tea leaves. Extended withering enhances enzyme activity, particularly polyphenol oxidase (PPO), promoting flavor and aroma development, while over-withering can reduce brightness and introduce off-flavors. Ideal conditions include temperatures of 20–30 °C, high humidity for slower dehydration, and steady airflow for uniform withering and microbial control. The quality and intensity also affect tea chemistry; UV rays enhance flavonoid production, red and yellow light influence the synthesis of metabolites, and controlled LED systems offer precise manipulation. Light intensity (50–200 μmol/m²/s) can stimulate beneficial metabolism, while excessive flux may degrade compounds. Indoor withering setups allow fine-tuning of these variables for consistent, high-quality tea. Different types of tea, white, green, oolong, and black, require different withering approaches, which will be briefly discussed.

Table 1. The withering treatment affects various tea processing processes and impacts biochemical changes and tea quality.

Type of tea Withering conditions Impact on the quality of tea Ref. Black tea Different degrees of withering with a final moisture content of approximately 65%, 60%, 55%, 50%, and 45% in the withered leaves (withered temp 33 °C, for 12 ± 1 h) - Reduce the total amount of catechins, flavonoids/flavonoid glycosides, theaflavins, and glycosidic bound volatiles (GBVs).

- The withering degree is associated with increasing free amino acids and volatile compounds.

- The 60% moisture content of the withered leaves exhibited the highest sensory quality score and the best bioactivity of black tea.[97] Keemun black tea Dynamic withering technology: Fresh leaves

are spread on dynamic conveyors at a thickness of approximately 20 cm. Tea leaves remain in continuous motion at a speed of 5 m/min

(temp. maintained at 23 ± 1 °C; for 15 h).- Total catechins decrease after the withering process.

- Total theaflavins increase significantly.

- Dynamic withering technology has more floral and fruitier odor-active compounds.[34] Black tea Red-light irradiation (630–640 nm, 725–1,015 lx) for 9 h. Indoor temperature of 24–29 °C and a RH of 46%–50%. - Increase the activity of the PPO and POD enzymes and theaflavin formation during fermentation.

- The number of amino acids is increased by inducing up-regulated expression of phenylalanine and tryptophan synthesis genes and the activity of peptidases.

- Treatment with red light can reduce the astringent and bitterness of black tea and improve the strong, fruity aroma and fresh and mellow taste.[35] Black tea Red-light irradiation (630 nm, approximately 3,000 lx) and dark conditions (temperature maintained at 28 °C, RH: 70%). - Red light predominantly disrupts secondary metabolite biosynthesis, amino acid synthesis and metabolic pathways.

- Lower content of theobromine, catechin, and some flavonoid glycosides

- Generate the accumulation of amino acids and flavins.

- Produce black tea with a mild, thick, and fresh taste.[36] Keemun Black Tea Natural withering (8–19 °C, 24 h, humidity 48%–75%); Sun withering (15–17 °C, 2.5 h,

with 5.68–8.36 Klx, humidity 48%–56%); Warm air withering (18–22 °C; 7 h in the withering trough).- Warm air withering reduced the concentration of catechins and flavonoid glycosides, increasing the sweet taste of tea infusion.

- The sun withering produced Keemun black tea with intense bitterness and astringency compared to the warm air withering (sweeter taste).[32] Black tea Ethylene (treated with continuous air ethylene at 10 μL/L). UV-C irradiation (254 nm) at varying doses (1 and 15 kJ/m2). - UV-C (15 kJ/m2) treatment resulted in rapid color changes from green to red/brown and increased catechin oxidation of catechins into theaflavin.

- Ethylene and UV-C treatments can shorten the withering time while improving the accumulation of flavor components, leading to higher-quality tea with a faster processing time.[37] Green tea Indoor natural environment (25 °C, 60% RH, natural light of 200 lx); Artificial climate box

(15 °C, 70% RH, at dark); Artificial climate box with two yellow light emitting diodes (LED) lamps (15 °C, 70% RH, and LED light of 250 lx/9 W); Controlled atmosphere (15 °C, 70% RH, 3% CO2, at dark).- Low-temperature withering reduces the level of oxidation of polyphenols by blocking the activity of polyphenol oxidase and maintaining the expression of flavanol synthase genes. The relative total amount of flavonoids reduced after withering.

- Low temperature and yellow light enhanced the synthesis of γ-aminobutyric acid, the metabolism of phenylalanine-methyl salicylate, and tryptophan-indole.

- Combination treatments can maintain and enhance the taste quality of green tea products and increase the aroma of green tea products due to the highest relative amount of terpene volatiles and amino acid-derived volatiles.[31,49] White tea Sunlight withering (SW, 17.5 Klx, 48 h); Withering tank (WWT, by blasting fresh air at

30 °C, 48 h); Indoor withering (IW, room temp: 21–27 °C, 52%–37% humidity).- SW significantly improved astringent flavonoids and flavone glycosides in white tea.

- SW exhibited a more floral scent due to the increase in geraniol and linalool.

- WWT had a grassy scent due to higher levels of hexanal.[18,98] White tea Applied yellow light color with an intensity

of 5,000 lx during withering (duration 36 h,

0.5 m distance between the tea and light,

1 cm thickness of tea in the sieve, temperature 25 °C, a wind speed of 1 m/s, and a humidity of 60%).- Yellow light withering produces a superior aroma and a large amount of methyl salicylate, geraniol, and nerolidol.

- Increasing the expression of flavonoid 3,5-hydroxylase (F3'5'H) affected the high accumulation levels of quercetin, kaempferol, and luteolin in white tea.

- Affects the decrease in catechin synthesis but increases the expression of genes for theaflavin synthesis, such as PPO (CSS0019276.1 and CSS0002951.1) and POD (CSS0021668.1, CSS0007582.1, and CSS0011664.1).[21] Oolong tea Sun withering was carried out in the sun at different ambient temperatures, 43 and 30 °C, for 15, 30, 60, and 120 min. - Primary aroma components increased during 15 min of solar withering compared to indoor withering.

- Sun withering can significantly increase the expression of essential genes associated with the aroma-related metabolic pathway. Up-regulation of heat shock and other resistance protein-related genes quickly suppresses their expression.

- Short-term solar withering can improve the development of scent throughout the oolong tea manufacturing process.[40] Wuyi rock tea (oolong tea) Sunlight withering (SW, 5–7 leaf thickness, light intensity 57,000 lx, withering time 45 min, turning tea leaves every 15 min); Charcoal fire withering (FW, temperature in the withering chamber around 35 °C, withering time 200 min with manual turning every 100 min); Withering (WW, hot air temp. 35 °C, 5–7 cm of leaves thickness, withering time 225 min, every 75 min for turning tea leaves). - SW significant increase in gene expressions such as ubiquinone and other terpenoid-quinone biosynthesis (ko00130), pyruvate metabolism (ko00620), starch and sucrose metabolism (ko00500), and tryptophan metabolism (ko00380) pathways.

- SW effectively increases the number of nucleotides and derivatives, terpenoids, organic acids, and lipids, resulting in the mellowness of tea, the fresh and brisk taste, and aroma.

- WW treatment influences a high amount of gene expression of the glutathione metabolism (ko00480) and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (ko00940) pathways.[99] The withering process in white tea

-

White tea is typically produced from various combinations of buds and young leaves of Camellia sinensis, using minimal processing steps such as withering and drying[14]. There are four types of white tea classified according to leaf maturity: Bai Hao Yin Zhen or silver needle (buds only), Bai Mu Dan or white peony (bud + one leaf), Gong Mei (bud + 2–3 leaves), and Shou Mei (bud + 4 leaves or just leaves)[15]. The 'silver needle' is one of the grades of white tea and is generally covered with silver or silky white feathers known as the 'trichome' on the surface of the bud[16].

Withering typically reduces moisture from 70%–80% to 20%–30% under sunlight or controlled indoor conditions, followed by drying[17,18]. The duration varies according to leaf moisture; examples include 49 h at 25 °C before drying[19], 36 h at 30 °C and 47% RH[20], and up to 4 d combining sun and indoor withering before drying at 60 °C[21]. Modern methods may use withering tanks with controlled air, temperature (30 °C), and light spectra (red, yellow, blue, red-blue, or white)[18,21].

Withering significantly shapes the flavor, aroma, and chemical profile of white tea. Solar withering often yields more floral aroma but also more bitterness and astringency than indoor methods[18,22]. Mild oxidation during withering by PPO reduces catechins and phenolic acids, forming theaflavins and altering the levels of flavonoids, amino acids, sugars, and alkaloids. This oxidation influences the accumulation of 17 flavonoids and flavonoid glycosides, free amino acids, flavanones and their derivatives, sugars, and a purine alkaloid[23]. Prolonged withering also results in considerable changes in metabolites related to mild, umami, and sweet flavor and gene transcription[23,24].

The withering process in black tea

-

Black tea processing involves plucking, withering, rolling, fermentation, and drying[25]. Withering is essential to soften leaves for rolling and prevent breakage[26]. During withering, it causes deterioration in the color of the tea leaves and uneven moisture loss[27], faster at the apex and back (stomata side) than at the center and surface, leading to curling, shrinkage, and surface roughness[27,28]. Typically, tea leaves are withered for 8–12 h to reach 56%–62% moisture content, undergoing both physical withering (loss of turgidity) and biochemical changes that occur immediately after they have been plucked and withered, leading to the breakdown of complex compounds into simpler ones. This stage is known as chemical withering[25,29,30]. Controlling physical and chemical withering is crucial, as over-withering can produce flat-tasting tea, while a gradual reduction in moisture optimizes flavor development[26,29].

Air temperature also affects chemical changes; lower temperatures suppress PPO activity, preserving flavonol synthase genes[31], while warm air reduces catechins and flavonoid glycosides, enhancing sweetness. On the contrary, sun withering (2.5 h at 5.68–8.36 lx) can increase catechin content and astringency[32]. Optimal withering conditions support umami and sweetness by promoting sugar formation and degradation of flavonoid glycosides[33].

Various techniques and technologies have been implemented in the withering process to improve the quality of black tea. Innovations such as dynamic withering, used in Keemun black tea, employ moving conveyors to reduce catechins while increasing theaflavins, leading to enhanced floral and fruity notes[34]. Red light treatment (630–640 nm, light intensity 725–1,015 lx) for 9 h at 24–29 °C and 46%–50% RH, enhance the activities of PPO and peroxidase (POD) enzymes, increases amino acids by up-regulating the expression of phenylalanine and tryptophan synthesis genes, and enhances theaflavin production, improving taste and aroma, characterized by a strong, long-lasting floral and fruity aroma and a fresh and mellow taste, while reducing astringency and bitterness[35,36]. Furthermore, ethylene and UV-C treatments can shorten the withering time and improve the accumulation of flavor compounds, although further research is needed for industrial application[37].

The withering process in oolong tea

-

Oolong tea processing includes solar and indoor withering, turning-over (bruising), enzyme inactivation, rolling, and drying[38]. Withering begins with exposure to sunlight to reduce moisture, followed by indoor withering[39], which facilitates catechin migration from the vacuoles to the cytoplasm[2]. Sun withering changes leaf color from bright to dark green in 15–30 min, with drooping and moisture loss; extended exposure (60–120 min) causes browning and leaf brittleness[40]. Following solar withering, indoor withering with turning-over, also known as bruising, partially dehydrates and lightly damages the leaves, triggering key chemical transformations[41,42]. Bruising and withering are critical steps in producing quality oolong tea. This stage influences amino acids, enhances terpenoid volatiles, and reduces the release of C6 green leaf volatiles[41].

Solar withering induces multiple stresses on fresh tea leaves, leading to significant biochemical alteration[43,44]. Specifically, solar withering increases terpenoid biosynthesis and inhibits flavonoid biosynthesis in withered leaves[45]. During this process, nine genes involved in terpenoid metabolomic pathways are upregulated, including DXS, DXR, HMGS, ISPG, ISPH, GPPS, FPPS, AFS, and LIS[40]. Consequently, oolong tea produced by this method has a less bitter or astringent taste and a loss of umami flavor[43]. These regulatory mechanisms collectively contribute to the mild flavor of oolong tea and a strong floral and fruity aroma[40,44,45]. This unique processing method highlights the importance of withering in enhancing the sensory qualities and overall quality of oolong tea.

The withering process in green tea

-

Green tea is processed through fixation, rolling, and drying. Fixation, by hot steaming or panning, reduces moisture and inactivates PPO to prevent oxidation and preserve green color[23,46]. During peak harvest, limited capacity often requires fresh leaves to be spread on bamboo sieves or withering racks and stored under fluorescent light before fixation, a step known as 'mild withering'[47]. This softens the leaves and enhances the umami taste and aroma of green tea[47,48]. However, if not carefully managed, PPO activity or leaf damage can cause oxidation, affecting tea quality[3].

The spread of leaves for 15–18 h at low temperatures (15–20 °C) is reported to produce high-quality green tea with high amino acid content, medium catechin concentration, and low caffeine[48]. Studies on fresh tea leaves from Echa 10 cultivars, subjected to four different spreading conditions, reported a gradual reduction in moisture content as the spreading time increased, although the rate of water loss varied significantly between treatments[49,50]. The application of natural withering indoors effectively maintains the moisture content from 78.6% to 72.1% over 7 h, with an average water loss rate of 0.9% per h. On the contrary, low-temperature withering in darkness and under yellow light took 14 and 18 h to reduce the moisture content to 72.2% and 71.8%, with an average water loss rate of 0.46% and 0.38% per h, respectively[50]. Furthermore, withering at low temperatures with CO2 took 48 h to reduce the moisture content to 74.2%, with an average loss rate of 0.092% per h. These results also indicate that low temperatures can slow moisture loss during spread, extending the freshness period of tea leaves after harvest[50]. Low-temperature withering reduces polyphenol oxidation by inhibiting PPO activity and maintaining the expression of flavanol synthase genes[31]. Furthermore, it also inhibits the activity and gene expression of the enzymes Mg-dechelatase, chlorophyllase, pheophorbide, and oxygenase, thus reducing chlorophyll degradation in postharvest tea leaves[50].

-

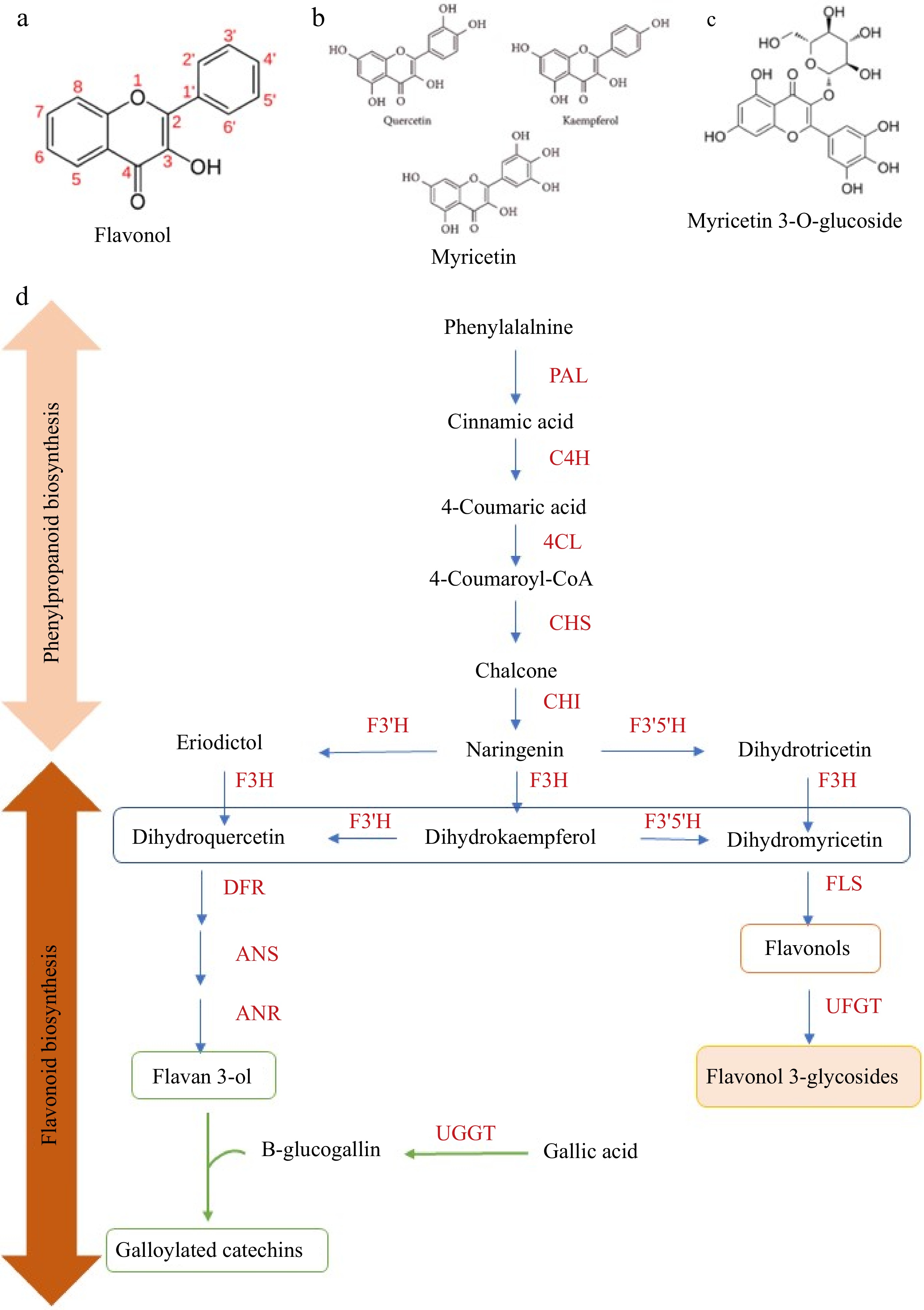

Flavonols are the second most abundant flavonoids in tea after flavan-3-ols and significantly influence tea taste, color, and aroma[51]. The basic structure of flavanols, shown in Fig. 2a–c, 3-hydroxyflavone, includes a hydroxyl group at the C-3 position. The main flavonol aglycones in tea include quercetin, myricetin, and kaempferol, typically found as O-glycosides with mono-, di-, or tri-glycosyl units[13]. Common glycosides include quercetin-3-O-galactoside (Q-gal), quercetin-3-O-glucoside (Q-glu), kaempferol-3-O-galactoside (K-gal), and kaempferol-3-O-glucoside (K-glu)[52]. These compounds, along with catechin and caffeine, are primarily responsible for the astringent and bitter taste, as well as its color and aroma[11].

Figure 2.

The basic skeleton of (a) flavonols, (b) aglycone flavonols, (c) flavonol glycosides, and (d) proposed biochemical changes of flavonoids in tea leaves during withering. Phenylpropanoid and flavonoid biosynthesis play a vital role in the biosynthesis of flavonol aglycones and flavonol glycosides. PAL, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase; C4H, cinnamate 4-hydroxylase; 4CL, 4-coumarate CoA ligase; CHS, chalcone synthase; CHI, chalcone isomerase; F3H, flavanone 3-hydroxylase; F3'5'H, flavonoid 3',5'- hydroxylase; F3'H, flavonoid 3'-hydroxylase; FLS, flavonol synthase; DFR, dihydroflavonol 4-reductase; ANS, anthocyanidin synthase; LAR, leucoanthocyanidin reductase; ANR, anthocyanidin reductase; UFGT, flavonol 3-O-glucosyltransferase; UGGT, UDP-glucose: galloyl-1-O-β-D-glucosyltransferase; ECGT, epicatechin: 1-O-galloyl-β-D-glucose O-galloyltransferase.

Fresh tea leaves contain approximately 3% flavonols and glycosides, although aglycones are rare[2]. Their content varies by leaf maturity and cultivar. In Duokangxiang, levels increase from buds (0.26 mg/g) to the fourth leaf (1.84 mg/g), then decrease in mature leaves (0.18 mg/g)[53]. Fudingdabaicha contains the highest levels of quercetin-3-O-glucosyl-rhamnosyl-glucoside (4.71–7.16 mg/g)[19]. Young leaves are richer in kaempferol than quercetin and myricetin[54]. Longjing 43 contains 2,078.7–2,726.5 mg/100 g fresh weight of total flavonol glycosides[55].

The flavonol glycoside content in various tea products is presented in Table 2. Several studies also reported that total flavonol glycosides in tea products range from 2.32−5.67 g/kg dry weight[56]. This study also indicated that green tea is particularly rich in kaempferol glycosides, while oolong tea contains higher levels of quercetin glycosides and myricetin glycosides. Another study reported that Longjing green tea contains 1.5 times more than Longjing green tea with short withering[57]. Black tea, on the other hand, is high in quercetin glycosides[56]. Similarly, green tea contains a high level of total flavonol glycosides compared to oolong and black teas, with respective ranges of 2,122−4,911, 1,672−3,877, and 1,511−4,176 μg/g[52].

Table 2. Flavonoid glycosides are found in various tea products (mg/g dry weight).

Identified flavonol glycosides Abbreviation Type of tea GT BT OT WT Myricetin-3-O-glucosyl-rhamnosyl-galactoside M-gal-rha-glu 0.12−0.26 0.16−0.17 0.33−0.36 n.d. Myricetin-3-O-glucosyl-rhamnosyl-glucoside M-glu-rha-glu 0.12−0.36 0.09−0.31 0.44−1.17 0.10 Myricetin-3-O-rhamnosyl-glucoside M-rha-glu 0.09−1.09 0.10−0.33 0.20−0.99 0.17 Myricetin-3-O-galactoside M-gal 0.16−1.24 0.10−0.49 0.21−1.66 0.27 Myricetin-3-O-glucoside M-glu 0.12−1.93 0.14−0.51 0.45−0.74 0.84 Quercetin-3-O-glucosyl-rhamnosyl-galactoside Q-gal-rha-glu 0.12−2.78 0.09−2.57 2.09−2.99 0.58 Quercetin-3-O-glucosyl-rhamnosyl-glucoside Q-glu-rha-glu 0.09−4.41 0.15−3.81 n.d. n.d. Quercetin-3-O-rhamnosyl-rhamnosyl-galactoside Q-gal-rha-rha 0.26−1.27 0.13−0.84 n.d. 13.86 Quercetin-3-O-rhamnosyl-rhamnosyl-glucoside Q-glu-rha-rha 0.10−0.97 0.13−0.3 n.d. n.d. Quercetin-3-O-rhamnosyl-galactoside Q-gal-rha 0.06−0.34 0.15−0.45 n.d. n.d. Quercetin-3-O-rhamnosyl-glucoside + Kaempferol-3-O-glucosyl-rhamnosyl-galactoside Q-glu-rha + K-gal-rha-glu 0.22−4.88 0.40−2.99 1.73−1.75 0.77 Quercetin-3-O-galactoside Q-gal 0.26−2.21 0.26−0.91 0.35−0.48 0.03 Quercetin-3-O-glucoside Q-glu 0.11−2.51 0.17−1.51 0.33−0.36 0.25 Kaempferol-O-rhamnosyl-rhamnosyl-galactoside K-gal-rha-rha 0.06−4.74 0.05−1.32 n.d. 5.73 Kaempferol-3-O-glucosyl-rhamnosyl-glucoside K-glu-rha-glu 0.05−8.65 0.25−5.87 n.d. n.d. Kaempferol-3-O-rhamnosyl-galactoside K-gal-rha 0.05−2.65 0.08−0.45 n.d. n.d. Kaempferol-O-rhamnosyl-rhamnosyl-glucoside K-glu-rha-rha 0.06−2.68 0.10−1.88 1.51−3.33 n.d. Kaempferol-3-O-galactoside K-gal 0.11−2.45 0.10−2.45 0.00−0.58 n.d. Kaempferol-3-O-rhamnosyl-glucoside K-glu-rha 0.06−2.61 0.06−2.61 0.32−0.48 0.07 Kaempferol-3-O-glucoside K-glu 0.10−1.46 0.17−1.33 0−0.38 n.d. Total flavonol glycosides TFG 3.78−17.81 5.57−14.77 11.18−12.06 23.30 TFG: Total flavonol glycosides; GT: Green tea; BT; Black tea; OT: Oolong tea; WT: White tea; n.d.: Not detected. The results are based on 474 tea samples reported by Fang et al.[19]. A comprehensive study that analyzed the composition of flavonol glycosides from 151 samples of different cultivars in China reported an average total flavonol glycosides content of 13.0 ± 6.86 mg/g, with a varied range of 0.32−38.0 mg/g. The study found that kaempferol 3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→3)-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranoside and quercetin 3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→3)-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranoside were the most dominant flavonol glycosides[58]. These findings underscore the importance of tea cultivars in determining the composition and concentrations of the tea product[52].

-

The biosynthesis in tea involves the shikimate, phenylpropanoid, and flavonoid pathways (Fig. 2d). The process begins with L-phenylalanine, which is converted to naringenin by phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL). Naringenin is then transformed into dihydrokaempferol by dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR), and further into kaempferol by flavonol synthase (FLS). Kaempferol acts as a precursor to other flavonols, such as quercetin and myricetin. These are glycosylated by UDP-glucose flavonoid-3-O-glycosyltransferases (UFGTs), forming flavonol glycosides. The UFGT activity is regulated by the CsUGT78A14 and CsUGT78A15 genes[59].

The accumulation of flavonol glycosides in tea is largely influenced by pre-harvest environmental stress and agronomic factors.

Variety and cultivar

-

The tea plant (C. sinensis [L.] O. Kuntze) has two main varieties, sinensis and assamica, each with distinct flavonol glycoside profiles[53,60]. The assamica variety contains more flavonol diglycosides, while sinensis accumulates higher levels of flavonol tri-glycosides, linked to differences in glycosyltransferase activity[58]. Specifically, assamica shows a higher activity of flavonol-3-O-glucoside L-rhamnosyltransferase and flavonol-3-O-rutinoside glucosyltransferase, while sinensis has more active flavonol-3-O-galactosylrhamnoside galactosyltransferase[58]. In particular, the cultivar has a greater influence on the composition of flavonol glycosides than the processing method[58].

Nitrogen supply

-

Nitrogen fertilization, essential for tea yield and quality, also affects the accumulation of flavonol glycosides. Optimal nitrogen levels enhance the production of quercetin-3-glucosides, kaempferol-3-galactosides, and kaempferol-3-glucosyl-rhamnosyl-glucosides[55]. On the contrary, nitrogen deficiency or excess reduces the content of flavonol glycosides, overall flavonoid levels, and carbohydrate synthesis. This may be due to the limited availability of sugar substrates such as UDP-glucose and hexose under nitrogen stress[55].

Leaf maturity

-

Only young tea leaves (bud to third leaf) are typically used in processing, as they greatly influence the quality of tea[61]. Flavonols, especially kaempferol, quercetin, and myricetin, accumulate most in young leaves, particularly the second leaf[53,54]. This high accumulation is associated with elevated expression of CsFLSa, which is about ten times higher than that of CsFLSb and CsFLSc. CsFLS regulates flavonol biosynthesis by converting dihydrokaempferol to flavonols[54].

Harvesting season

-

Seasonal variation affects the content of flavonol glycosides and the overall quality of tea leaves. Flavonol glycosides accumulate at higher levels in August, linked to up-regulation of CsFLs and CsUGTs, key genes in flavonol biosynthesis[62]. CsMYB67 also plays a vital role in the regulation of downstream flavonoid pathways, particularly in summer-harvested leaves[63]. Compounds such as quercetin-3-O-galactoside and kaempferol-3-O-(6"-O-p-coumaroyl)-glucoside, abundant in August, contribute to the characteristic bitterness and astringency of summer teas[62].

Light intensity

-

Light intensity and ultraviolet-B (UV-B) radiation significantly affect the accumulation of flavonol glycosides in tea. High levels of sunlight and UV-B upregulate CsMYB12, which activates flavonoid biosynthetic genes such as CsFLS, CsLARa, and CsDFRa, increasing flavonol production and tea astringency[64]. In contrast, shading reduces flavonol glycoside levels by suppressing CsHY5 and CsMYB12, thereby limiting downstream gene activation[64,65].

Elevated levels of carbon dioxide (CO2)

-

The rise in atmospheric CO2 due to climate change alters the metabolism and physiology[66]. Elevated CO2 enhances the expression of genes in the phenylpropanoid pathway, including the expression of CsANR (anthocyanidin reductase), an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of anthocyanidins to epicatechin, leading to increased catechin levels such as epigallocatechin (EGC) and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG)[67]. Furthermore, elevated CO2 also improves the production of salicylic acid and nitric oxide (NO), which activates phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), further promoting flavonoid biosynthesis[66]. While the role of FLS in the biosynthesis of flavonol glycosides under elevated CO2 remains unclear, a study in soybeans (Glycine max L.) suggests that higher CO2 can increase quercetin and kaempferol glycosides, indicating a potential adaptive response to oxidative stress[68].

Cold and drought stress

-

Tea plants are sensitive to cold and drought, both of which trigger distinct physiological and biochemical responses[69]. In drought, activation of CsMPK4a, a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), leads to phosphorylation of the CsWD40 protein at specific sites (Ser-216, Thr-221, and Ser-253), altering its interaction with key transcription factors (CsMYB5a, CsAN2) involved in the biosynthesis of procyanidin and anthocyanidin biosynthesis[70]. Drought also down-regulates flavonoid biosynthetic genes such as chalcone synthase (CHS), flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H), and flavonol synthase (FLS)[71]. In response to cold, tea plants, especially cold-resistant cultivars, accumulate more kaempferol, quercetin, and myricetin[72]. Cold stress also up-regulates the glycosyltransferase enzyme CsUGT78A14, promoting flavonol glycosides accumulation, and enhancing ROS elimination and stress tolerance[73].

Saline-alkali stress

-

Saline-alkali stress, which involves both ionic and osmotic stress, significantly affects tea plants, particularly due to elevated sodium ion (Na+) concentrations that disrupt ion homeostasis and cause toxicity[74]. Tea plants respond by altering gene expression in the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. For instance, CsHCT, which encodes hydroxycinnamoyl transferase, is upregulated under high salinity, suggesting its role in enhancing flavonoid accumulation to mitigate salt stress[75]. However, salinity reduces specific catechins, such as EGCG[74], and the involvement of flavonol synthase (FLS) in flavonol glycosides accumulation under saline-alkali conditions remains poorly understood. Further research is needed to clarify the role of flavonol metabolism in the mechanisms of adaptation to tea stress.

-

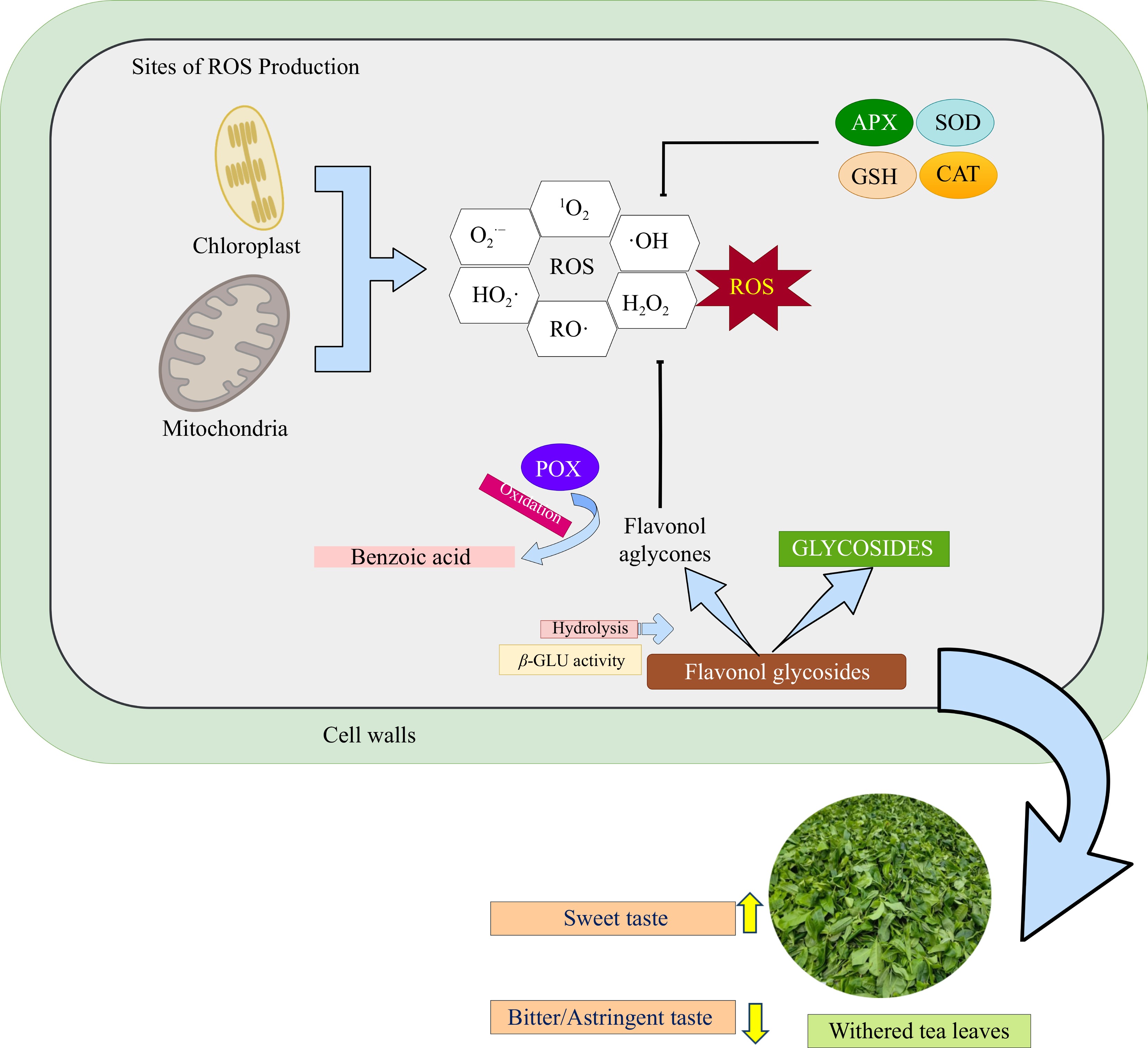

Post-harvest, tea leaves remain metabolically active, and the withering process exposes them to abiotic stresses such as sunlight, temperature shifts, dehydration, and mechanical injury[18,32,36,76]. These stresses trigger the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which function as signaling molecules in plant defense[17,40,77]. Under normal conditions, the balance between ROS production and ROS scavenging plays a role as signaling molecules for growth and responses to stress in plant cell metabolism. However, under stress conditions such as those encountered during withering, tea plants accumulate a high level of ROS. These include free radicals such as superoxide anion (O2·−), hydroperoxyl radical (HO2·), alkoxy radical (RO·), and hydroxyl radical (·OH), as well as non-radical molecules such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and singlet oxygen (1O2). The excessive accumulation of ROS leads to oxidative stress, which can cause cell damage and reduce the productivity of tea plants[77,78]. ROS originates mainly in organelles such as chloroplasts, mitochondria, plastids, peroxisomes, the cytosol, and the apoplast[79−81].

Chloroplasts and peroxisomes are key sites of ROS production during environmental stress, such as sunlight, heat, and dehydration during withering. In chloroplasts, photosystems I and II (PSI and PSII) in the thylakoid membranes generate ROS due to reduced CO2 availability from stomatal closure, causing excess light energy to convert O2 into O2·− through the Mehler reaction or into1O2, which is further transformed into H2O2 by Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase (SOD) in PSI[79−81].

In peroxisomes, under stress, the enzyme ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RUBP) carboxylase/oxygenase changes to oxygen as substrate, producing glycolate. Its oxidation by glycolate oxidase generates H2O2[81,82]. Additionally, the peroxisome also produces O2·− in the peroxisomal matrix as a by-product of metabolizing xanthine and hypoxanthine into uric acid, and in the peroxisomal membrane, releasing O2·− into the cytosol after using O2 as an electron acceptor[79,81]. Understanding these ROS pathways is crucial for managing oxidative stress and preserving tea quality during withering.

Degradation of flavonol glycosides as stress responses in tea leaves

-

Flavonols, mainly in glycoside form, contribute to photoprotection, hormone regulation, and ROS scavenging in plants[7]. However, the specific mechanisms underlying the degradation of flavonol glycosides during the withering process, particularly in their role in mitigating ROS accumulation in tea leaves, remain insufficiently understood. During withering, the degradation of flavonol glycosides are thought to be part of the plant's defense against excessive ROS, although the mechanisms remain unclear. This process likely involves both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems that work together to neutralize ROS and maintain cellular balance under stress.

Enzymatic antioxidant defense

-

During abiotic stress, tea leaves up-regulate antioxidant enzymes to counter elevated ROS levels. Key antioxidant enzymes include superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), monodehydroascorbate reductase (MDHAR), dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), glutathione reductase (GR), and guaiacol peroxidase (GPX)[81,82]. Additional enzymes such as peroxidases (POX), polyphenol oxidases (PPO), glutathione S-transferase (GST), peroxiredoxins (PRX), and thioredoxin (TRX) also contribute to ROS detoxification[81]. These enzymes act through distinct catalytic pathways in various subcellular compartments to maintain redox balance[81,83].

Tea leaves are subjected to extreme conditions due to various abiotic stresses after 12 h of withering. Under stress conditions, SOD enzymes initiate as the first line of defense from ROS-induced damages and convert O2·− into H2O2 by dismutation. Subsequently, the H2O2 generated is detoxified through the action of CAT, APX, and GPX, or further reduced to water (H2O) through the ascorbate-glutathione (AsA-GSH) cycle[81,83]. According to Deng et al.[17], the expression of key antioxidant enzymes, including glutathione reductase (GR), CAT, APX, and POX, increases gradually, in correlation with the gradual accumulation of ROS in tea leaves. CAT (EC.1.11.1.6), present in peroxisomes and mitochondria, plays a role in ROS by converting H2O2 into H2O. APX (EC.1.1.11.1), which is active mainly in chloroplasts, also converts H2O2 to H2O, using ascorbic acid (AsA) as a reducing agent, and produces monodehydroascorbate (MDHA) through the AsA-GSH cycle[81,83]. GR (EC 1.6.4.2), predominantly located in the chloroplast, with a small amount present in the mitochondria and the cytosol, reduces oxidized glutathione (GSSG) to its reduced form (GSH) using NADPH, facilitating the regeneration of ascorbic acid from MDHA and DHA[77,79,81,82].

Peroxidase (POX, EC 1.11.1.7) primarily oxidizes phenolic compounds (PhOH) to produce phenoxyl radicals (PhO·), using H2O2 as an electron acceptor, which is converted to H2O. In the presence of AsA, PhO· reacts with AsA, leading to the formation of monodehydroascorbate (MDHA), which is converted into dehydroascorbate (DHA)[83]. The detailed enzymatic mechanisms and reactions involved in the antioxidant defense system are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Mechanism of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants with their roles and localization in scavenging major reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Antioxidants Reaction with ROSa Subcellular locationa Function in ROS scavengingb Enzymatic antioxidants Superoxide dismutase

(SOD; EC 1.15.1.1)2O2·− + 2H+ → O2 + H2O2 Chloroplast, peroxisomes, cytosol, mitochondria, apoplast Converts superoxide to H2O2 Catalase

(CAT; EC 1.11.1.6)2 H2O2 → 2H2O + O2 Peroxisomes, mitochondria dismutation high levels of H2O2 into H2O and O2 Ascorbate peroxidase

(APX; EC 1.11.1.11)H2O2 + AsA → 2H2O + MDHA Chloroplast, peroxisomes, cytosol, mitochondria, apoplast Converts H2O2 to H2O using AsA as a reducing agent Monodehydroascorbate reductase

(MDHAR; EC 1.6.5.4)MDHA + NAD(P)H → AsA + NAD(P)+ Mitochondria, cytoplasm, chloroplast Regenerates ascorbate from MDHA Dehydroascorbate reductase

(DHAR; EC 1.8.5.1)2GSH + DHA → GSSG + AsA Mitochondria, cytoplasm, chloroplast Reduces DHA using an electron donor from GSH to maintain the ascorbate pool Glutathione peroxidase

(GPX; EC 1.11.1.9)H2O2 + GSH → H2O + GSSG Cytosol, mitochondria Reduces H2O2 and lipid peroxides Glutathione S-transferase

(GST; EC 2.5.1.18)R-X + GSH → GS-R + H-X Chloroplast, cytosol, mitochondria Detoxifies lipid hydroperoxides Peroxidases

(POX; EC 1.11.1.7)2PhOH + H2O2 → 2PhO· + 2H2O

2PhO· → cross-linked substances

PhO· + AsA → PhOH + MDHA

PhO· + MDHA → PhOH + DHACell wall, apoplast, vacuole Uses phenolics to reduce H2O2 Polyphenol oxidase

(PPO; EC 1.14.18.1)PhOH + O2 → Catechols

Catechols + O2 → Q + H2OThe thylakoid membrane of the chloroplast, cytosol, and vacuole Oxidizes phenolics, reduces ROS load Non-enzymatic antioxidants Ascorbic Acid AsA + O2·− → MDHA + H2O Chloroplast, peroxisomes, cytosol, mitochondria, apoplast Detoxifies H2O2 via the action of APX Glutathione (GSH) 2GSH + H2O2 → GSSG + 2H2O Cytosol, chloroplast, mitochondria, peroxisome, vacuole, apoplast Acts as a detoxifying co-substrate for enzymes like peroxidases, GR, and GST α-Tocopherol Tocopherol-OH+ROO· →

Tocopherol-O·+ROOHChloroplasts and mainly in mitochondrial membranes Guards against and detoxifies the products of membrane LPO Carotenoids Carotenoid + 1O2 →

Carotenoid + 3O2Chloroplast Detoxifying various ROS and capturing the lipid peroxyl radical (LOO·) Proline Proline + ·OH → Proline radical+H2O Mitochondria, cytosol, chloroplast Efficient scavenger of OH· and1O2 and prevents damage due to LPO Flavonoids Flavonoid-OH + ROS →

Flavonoid-O· + H2OVacuole and chloroplast Direct scavengers of H2O2 and1O2 and OH· APX: Ascorbate peroxidase; AsA: Ascorbic acid; DHA: Dehydroascorbate; DHAR: Dehydroascorbate reductase; GSH: Reduced glutathione; GSSG: Oxidized glutathione; GR: Glutathione reductase; MDHA: Monodehydroascorbate; PhOH: Phenolic compounds; PhO·: Phenoxyl radical; Q: Quinone; LPO: Lipid peroxidation; ROOH: Hydroperoxides; ROO·: Peroxyl radical; ROS: Reactive oxygen species. Notation of a and b according to the reference[79,81−83,100]. Non-enzymatic antioxidant defense

-

In addition to enzymatic antioxidants, tea leaves rely on low molecular weight antioxidants to maintain redox balance under abiotic stress. These non-enzymatic antioxidants scavenge ROS such as O2·−, H2O2, ·OH, and ROO·[69,79,81,82]. The main compounds include ascorbic acid (AsA), glutathione (GSH), α-tocopherol, carotenoids, and flavonoids, which help regulate ROS levels in the cell compartments during stress conditions such as the withering process[77,82].

Ascorbic acid (AsA) functions as an antioxidant by donating electrons to reduce superoxide radicals to H2O2. The resulting monodehydroascorbate (MDHA) is regenerated to AsA by monodehydroascorbate reductase (MDHAR)[77,82]. Glutathione (GSH) also plays a central role, directly scavenging ROS or participating in the ascorbate–glutathione cycle by reducing dehydroascorbate (DHA) to AsA, while being oxidized to glutathione disulfide (GSSG). GSSG is then recycled into GSH by glutathione reductase using NADPH[77,81].

α-Tocopherol, a lipid-soluble antioxidant, interrupts lipid peroxidation by neutralizing lipid peroxyl radicals and is regenerated by AsA or GSH[81]. Carotenoids, including β-carotene and xanthophylls, protect against photooxidative damage by quenching singlet oxygen (¹O2) and dissipating excess chlorophyll energy through non-photochemical quenching[77,81,82]. This mechanism is particularly critical to prevent ROS overproduction under conditions of high light intensity.

Flavonoids, particularly flavan-3-ols and flavonols, represent another major class of non-enzymatic antioxidants in tea, mitigating ROS-induced oxidative damage by disrupting the propagation of the free radical chain[69,77]. Specifically, flavonoids with ortho-dihydroxylated B-rings, such as catechin gallate, quercetin, and their glycosylated derivatives, are known to enhance photoprotection and improve acclimatization of tea plants under stress conditions[84]. The detailed reactions and cellular localization of non-enzymatic antioxidants are summarized in Table 3.

Flavonoids interact with ROS through three main mechanisms: (i) hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), (ii) single electron transfer followed by proton transfer (SET-PT), and (iii) sequential proton loss electron transfer (SPLET)[85,86]. As summarized in Table 4, HAT involves the donation of hydrogen from a flavonoid's hydroxyl group to ROS, forming a stable phenoxyl radical, predominantly in hydrophobic environments such as lipid membranes[86]. In SET-PT, an electron is transferred from the flavonoid to the radical, followed by proton transfer, typical of aqueous compartments such as the cytosol and vacuole[85,87]. SPLET starts with hydroxyl deprotonation, forming a phenolate anion that donates an electron to neutralize ROS and is especially effective under alkaline conditions in both cytosolic and apoplastic spaces[85,86].

Table 4. Mechanism of antioxidant scavenging of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Mechanism Principle Step-by-Step Reaction Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT) Direct hydrogen atom donation from the hydroxyl group to neutralize ROS Ar–OH + R· → Ar–O· + RH Single Electron Transfer (SET) Electron donation to R· Ar–OH + R· → Ar–OH·+ + R− Single Electron Transfer Proton-Transfer (SET-PT) Electron transfer followed by proton loss Ar–OH → Ar–OH·+ → Ar–O· + H+ Sequential Proton Loss Electron Transfer (SPL-ET) Deprotonation followed by electron transfer Ar–OH → Ar–O− → Ar–O· + e− Ar–OH: Antioxidant; R·: Radical. Reaction antioxidants according to Estévez et al.[85], Stepanic et al.[86]. Mechanism of degradation of flavonol glycosides mitigating oxidative stress during the withering process

-

During withering, tea leaves undergo oxidative stress, activating both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems to regulate ROS. The degradation of flavonol glycosides plays a key role in this defense, as evidenced by the significant reduction in flavonoid content reported during withering, suggesting their active involvement in ROS scavenging to mitigate oxidative damage[4,31,33].

Transcriptomic studies have shown that the expression of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) involved in flavonoid biosynthesis, including genes encoding enzymes for flavonols and catechin synthesis, is significantly downregulated during the withering process[4]. Specifically, the transcription of leucoanthocyanidin reductase (LAR) and anthocyanidin reductase (ANR), responsible for the biosynthesis of (+)-catechin, (+)-gallocatechin, (−)-epicatechin, and epigallocatechin (EGC), decreases sharply after 12 h of withering. Similarly, upstream DEGs in the phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathway, such as phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) and chalcone synthase (CHS), exhibit substantial down-regulation within the first three hours after withering[4,88]. On the contrary, the accumulation of flavonols and flavonol glycosides during withering appears to be cultivar dependent. For example, flavonol synthase (FLS) expression has been shown to increase in green and purple tea cultivars, correlated with elevated flavonol glycosides levels and simultaneous peroxidase (POX) activity, while albino cultivars show a progressive decline in flavonol glycosides with extended withering duration[89,90]. These metabolic adjustments result in substantial variation in the concentrations of total flavonoids, flavonoid glycosides, and catechins at the end of the withering phase[4,31,33].

During abiotic stress, the antioxidant activity of flavonol glycosides involves enzymatic deglycosylation followed by the interaction of the aglycone with ROS and oxidative enzymes. Two key degradation pathways during withering are enzymatic hydrolysis and enzymatic oxidation[7,11,91]. Prolonged withering increases the activity of PPO and glycosidase (GA) in tea leaves[17,92]. Although enzymatic oxidation typically requires cellular damage for enzyme-substrate interaction, glycosidic hydrolysis can occur independently of such contact[93].

Figure 3 presents a simplified schematic of flavonol glycoside degradation and antioxidant defense in tea leaves during withering. Deglycosylation, catalyzed by glycosidases, particularly β-glucosidase (β-GLU), is the first step, cleaving the β-glycosidic bond to release aglycones such as quercetin and kaempferol in the vacuole[7]. Prolonged withering upregulates β-GLU, enhancing the release of these aglycones, such as quercetin and kaempferol, which exhibit stronger antioxidant activity than their glycosylated forms[38,93]. Aglycones are then transported to compartments such as chloroplasts, mitochondria, or the apoplast, key ROS-generating sites under stress[94]. Additionally, prolonged withering is related to reduced levels of myricetin and quercetin and increased accumulation of benzoic acid derivatives, indicating further catabolic transformation, although this pathway remains unclear[93].

Figure 3.

Simplified schematic of flavonol glycosides degradation and antioxidant defense mechanisms in tea leaves during the withering process. This stage involves the action of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems to mitigate excess reactive oxygen species (ROS)[81,84]. Abiotic stress during withering triggers ROS generation in mitochondria and chloroplasts, which is subsequently mitigated by enzymatic antioxidants, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), catalase (CAT), and glutathione (GSH). Concurrently, flavonol glycosides, acting as non-enzymatic antioxidants, undergo enzymatic hydrolysis catalyzed by β-glucosidase, releasing flavonol aglycones and sugar moieties. Subsequently, the liberated flavonols function as ROS scavengers. Further oxidation of flavonols, mediated by peroxidase (POX), contributes to the formation of benzoic acid and its derivatives[7,93].

Once released, flavonol aglycones, such as quercetin, participate in ROS detoxification through both redox cycling and enzymatic pathways (Table 4). In the presence of H2O2 and POX, two quercetin molecules donate electrons to reduce H2O2 to water (H2O), generating semiquinone radical intermediates. Subsequently, these intermediates undergo dismutation, producing one molecule of O-quinone and one regenerated quercetin molecule. The O-quinone, in turn, can be enzymatically reduced back to quercetin by quinone reductase, using NAD(P)H as a reducing equivalent, thus restoring the antioxidant pool and preventing quinone-induced cytotoxicity[91,95]. The reaction sequence is summarized below:

$ \rm 2\;Quercetin\;+\;H_{2}{O}_{2} \to 2\;Semiquinone\;intermediates\;+\;2\;H_{2}{O} $ (1) $ {\rm 2\;Semiquinone \to Quercetin\;+\; }\mathit{O}{\text -}{\rm quinone} $ (2) $ \mathit{O}{\text -}{\rm quinone\;+\;NAD(P)H \to Quercetin\;+\;NAD(P)}^{+} $ (3) The degradation of flavonol glycosides is also influenced by processing conditions. For example, red-light irradiation during withering significantly increases the activity of PPO and POX, resulting in higher theaflavin content and accelerated degradation of flavonol glycosides. This process helps to reduce bitterness and astringency in the final black tea product[35,36]. Conversely, withering at low temperatures suppresses phenolic oxidation by limiting PPO activity and maintaining FLS gene expression, which also aids in the conversion of theobromine to caffeine[31]. Overall, flavonol glycoside degradation during withering serves as an adaptive response to oxidative stress by reducing ROS accumulation and protecting cellular integrity. Additionally, it plays a vital role in enhancing the sensory quality of tea by reducing the bitterness and astringency associated with these compounds.

-

This review summarizes the current understanding of the role of flavonols and flavonol glycosides during the withering process in tea production. During withering, tea leaves are exposed to abiotic stress factors such as sunlight, light intensity, and temperature fluctuations, leading to the formation of ROS. Oxidative stress occurs when ROS levels exceed the antioxidant defense system's capacity to neutralize them. Flavonol glycosides, which are considered end metabolites and are relatively stable against chemical or enzymatic changes, are degraded as part of the plant's response to mitigate cell damage caused by ROS.

Both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant defense systems contribute to the catabolism of flavonol glycosides. Enzymatic antioxidant defense, particularly hydrolysis and oxidation reactions, plays a dominant role in this degradation process. The degradation of flavonol glycosides during withering contributes to a sweeter, less bitter, and less astringent taste, which ultimately enhances the flavor and aroma of the tea.

Despite the accumulated knowledge of the degradation of flavonols during withering, several important questions remain. First, more research is needed to understand the changes in gene expression in flavonols and flavonol glycosides throughout each stage of tea processing. For example, a recent study suggests that β-GLU-mediated hydrolysis of flavonol glycosides during withering affects the up-regulation of benzoic acid and its derivatives[93]. However, the metabolic pathways leading to the formation of benzoic acid and its derivatives, which also influence the quality of tea, need further investigation.

The withering process, which typically takes about eight hours (depending on relative humidity, temperature, and tea type), is crucial to achieve the desired moisture content in the tea leaves. However, balancing the reduction in withering time while ensuring optimal physical and biochemical changes is a significant challenge. This is particularly important for the degradation of flavonol glycosides and the development of aroma and flavor. Technological advancements, such as varying levels of light radiation, dynamic withering technology, and specialized withering tanks, have improved tea quality. However, issues related to cost efficiency and energy consumption still need to be addressed.

With the advancement of analytical instrumentation, significant progress has been made in monitoring the dynamic changes of flavonol glycosides in tea, from the farm stage to the final product. Metabolomic techniques, including both targeted and non-targeted approaches, have been extensively utilized to enhance the understanding of the metabolites that contribute to tea leaf composition. The integration of metabolomics with other omics platforms (genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics) has proven particularly valuable, as these complementary data sets provide a comprehensive understanding of biological responses and metabolic alterations in tea plants under abiotic stress and throughout processing.

However, the effectiveness of metabolomic approaches is highly dependent on the rigor of sample preparation, including factors such as sampling strategy, extraction protocols, and solvent selection. Inadequate preparation can lead to limited information on metabolite distribution within tea leaves, hindering the accurate elucidation of metabolite biosynthesis and degradation at both tissue and cellular levels. To overcome these limitations, mass spectrometry imaging (MSI) has emerged as a promising technique that offers detailed spatial information on metabolite distribution, thus facilitating the interpretation of metabolic pathways within specific tissues. Notably, the non-destructive desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry imaging (DESI-MSI) technique has been successfully applied for the direct visualization of catechins, flavonols, and amino acids in oolong tea[96].

Flavonol glycosides in tea could serve as a fingerprint to determine the quality of different types of tea from various cultivars and geographical origins. This aspect provides opportunities for more precise quality control and authentication of tea products. Further research and technological advancements are essential to gain a deeper understanding of the mechanisms of degradation and to improve the efficiency and quality of tea processing.

-

The authors confirm the contributions to the article as follows: writing - preparation of original draft, visualization: Prawira-Atmaja MI; writing - review and editing, supervision: Puangpraphant S. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article.

-

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Prawira-Atmaja MI, Puangpraphant S. 2025. Flavonol glycosides in tea: the role of mitigating oxidative stress during the withering process. Beverage Plant Research 5: e031 doi: 10.48130/bpr-0025-0017

Flavonol glycosides in tea: the role of mitigating oxidative stress during the withering process

- Received: 28 February 2025

- Revised: 21 April 2025

- Accepted: 03 May 2025

- Published online: 17 October 2025

Abstract: Withering is a crucial step in tea production that reduces the moisture content and induces biochemical changes in tea leaves. The withering process triggers oxidative stress by accumulating reactive oxygen species (ROS) in tea leaves. The presence of flavonol glycosides is crucial for tea quality and tea's stress response to environmental changes pre- and post-harvest. However, the role of flavonol glycosides during withering remains unexplored. The degradation of flavonol glycosides during withering is mainly attributed to the enzymatic antioxidant defense system, which produces flavonol aglycones and soluble sugars that protect leaf cells from oxidative stress. This degradation contributes to a sweeter taste and enhances the taste and aroma of tea. This review emphasizes the role of the withering process and the degradation of flavonol glycosides, highlighting their role in neutralizing ROS formation as a response to oxidative stress, and discusses how changes in flavonol glycosides contribute to the taste of tea. The importance of the withering process in the degradation of flavonol glycosides is also highlighted. Further research is needed to understand the dynamic changes of flavonol glycosides during the withering process, which is essential to improving tea quality.

-

Key words:

- Flavonol glycosides /

- Withering /

- Tea processing /

- Oxidative stress /

- Antioxidant defense