-

Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi is a perennial herb belonging to the genus Scutellaria in the Lamiaceae family. With a long history of use in traditional medicine, it is considered a major medicinal herb due to its unique therapeutic properties, wide availability, and high yield. S. baicalensis was first recorded in Shennong Bencaojing and was classified as a superior-grade herb with no toxicity. Modern pharmacological studies have shown that its extracts possess antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and antioxidant properties[1]. Widely used in traditional Chinese medicine, S. baicalensis is valued for its ability to clear heat, detoxify the body, eliminate dampness, and relieve lung-heat-induced cough. Beyond clinical applications, it is also incorporated into medicinal cuisine for its health benefits[2].

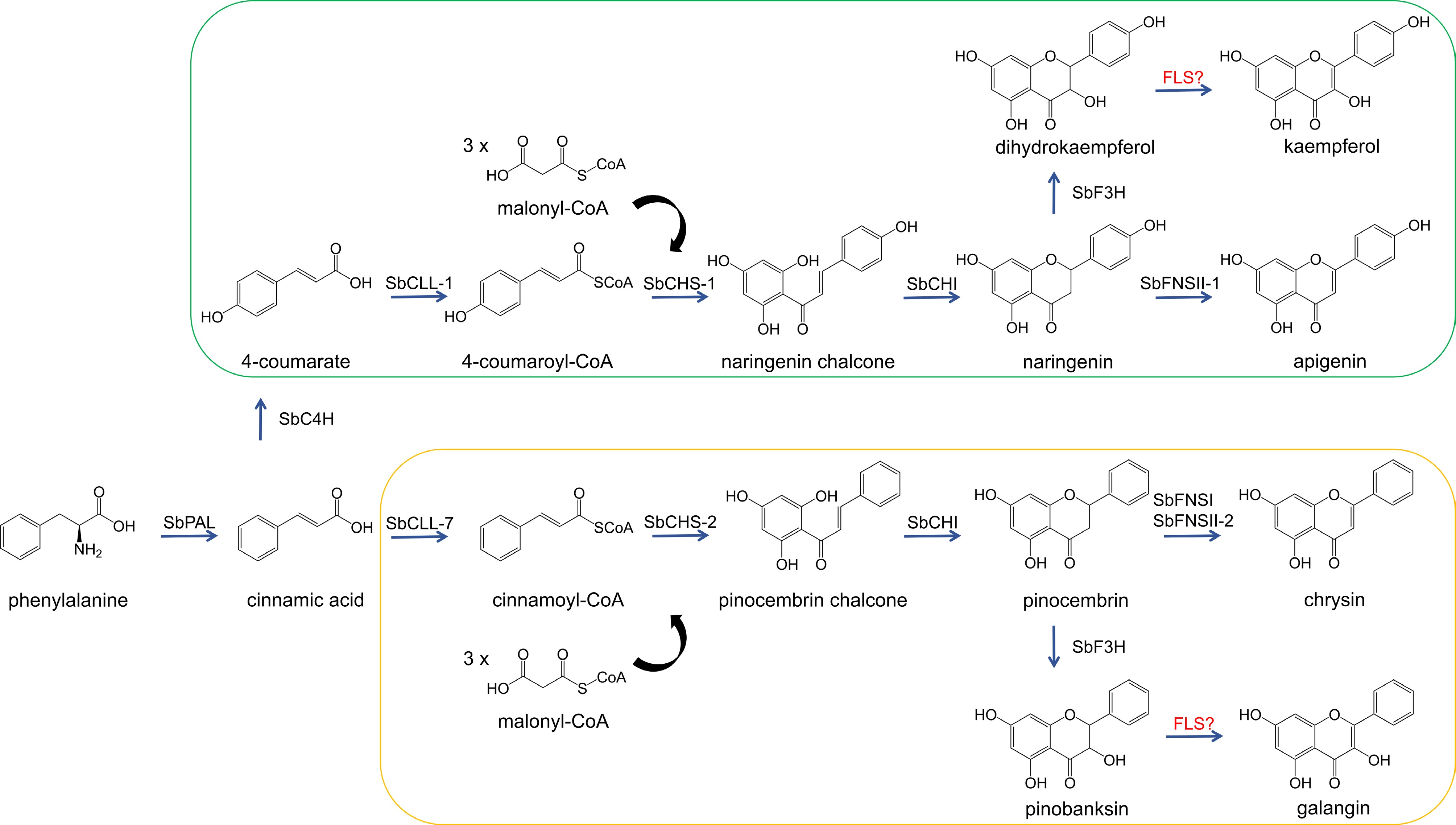

Flavonoids are considered responsible for the biological activity of S. baicalensis. Baicalein, baicalin, wogonin, and wogonoside are common active flavone components found in S. baicalensis, and their biosynthetic pathways have already been elucidated[3,4]. S. baicalensis also contains bioactive flavonols including kaempferol (4'-hydroxyflavonol), and galangin (4'-deoxyflavonol)[5], which are derived from another branch pathway of flavonoid biosynthesis (Fig. 1). These compounds have been reported to exhibit therapeutic effects against various cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and tumors[6,7]. However, the biosynthetic pathway of flavonols in S. baicalensis remains unclear.

Figure 1.

The biosynthetic pathway of flavonols in S. baicalensis. SbPAL, phenylalanine ammonialyase; SbC4H, cinnamate 4-hydroxylase; SbCLL-1, 4-coumarate CoA ligase; SbCHS, chalcone synthase; SbCHI, chalcone isomerase; SbFNS, flavone synthase; SbCLL-7, cinnamate-CoA ligase; SbF3H, flavanone 3-hydroxylase; FLS, flavonol synthase. The enzymes highlighted in red are still under investigation. The green-bordered part shows the metabolic pathway of 4'-hydroxyflavonoids; the yellow-bordered part shows the metabolic pathway of 4'-deoxyflavonoids.

Flavonol synthase (FLS) is an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of dihydroflavonols into flavonols, and it belongs to the DOXC47 subfamily of the 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase (2ODD) family[8]. The activity of FLS was first observed in the cell culture medium of Petroselinum hortense[9], and subsequently characterized in other plant species, such as Arabidopsis thaliana (AtFLS1)[10], Citrus unshiu (CitFLS)[11], Oryza sativa (OsFLS)[12], and Allium cepa (AcFLS)[13]. FLSs from different plant species exhibit varying substrate specificities and, consequently, distinct functions. AtFLS1, CitFLS, and OsFLS possess bifunctional activities of both flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H) and FLS, enabling them to sequentially catalyze naringenin, converting it into dihydrokaempferol and subsequently kaempferol[10−12]. In contrast, AcFLS shows only monofunctional FLS activity, transforming dihydrokaempferol into kaempferol[13]. Despite extensive research on FLSs, the reactions they participate in are all related to the biosynthesis of 4'-hydroxyflavonols (kaempferol). To date, no FLS responsible for the biosynthesis of 4'-deoxyflavonols (galangin) has been reported, which restricts the production of 4'-deoxyflavonols in synthetic biology.

In this study, three FLSs, Sb2ODD8, Sb2ODD11, and Sb2ODD12, from S. baicalensis were identified. They were expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and assayed for their catalytic activity in vivo. The present results provide important clues for the biosynthesis of flavonols through metabolic engineering.

-

S. baicalensis plants were grown in the greenhouse of Shanghai Chenshan Botanical Garden (Shanghai, China).

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis of Sb2ODD genes

-

Multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic analyses were performed using MEGA 11[14]. The maximum-likelihood tree was generated under default parameters using Sb2ODD sequences alongside functionally characterized FNSI/F3H/FLS/ANS proteins, and bootstrap support values were calculated with 1,000 replicates.

Gene cloning and expression vector construction

-

Sb2ODD8 and Sb2ODD12, which were amplified by PCR, were cloned into the entry vector pDONR207 using the Gateway BP Clonase II Enzyme Kit (Invitrogen, MA, USA). The primers used for cloning the target fragments are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Sb2ODD11 was obtained by de novo synthesis (GenScript, Nanjing, China) and subsequently cloned into the entry vector pDONR207. To verify enzyme activity, all genes were cloned into the yeast expression vector pYesdest52 and prokaryotic expression vector pYesdest17.

In vivo yeast enzyme assays

-

The successfully constructed pYesdest52 vectors were transformed into S. cerevisiae WAT11[15] using the Yeast Transformation II Kit (ZYMO, CA, USA). The WAT11 were grown on synthetic drop-out medium plates without uracil (SD-Ura) containing 20 g/L glucose at 28 °C for 48 h. The recombinant yeast strains were initially cultured in SD-Ura liquid medium containing 20 g/L glucose at 28 °C for 24 h, until reaching an OD600 of 2–3. Yeast cells were harvested by centrifugation (4,000 × g, 10 min), washed, and resuspended in SD-Ura liquid medium containing 20 g/L galactose to induce heterologous protein expression. Substrates and 2-oxoglutarate were added to the induction medium. Following a 48-h fermentation period at 28 °C, yeast cells were harvested by centrifugation. Metabolites were extracted from the cell pellet using 1 mL of 70% MeOH (pH = 5.0) for metabolite analysis.

Protein purification, in vitro enzyme activity, and enzyme kinetic analysis

-

The empty vector or recombinant prokaryotic expression vector was transformed into Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3). Transformants were initially grown in 10 mL of LB liquid medium supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin at 37 °C for 12 h, and then inoculated into 300 mL of fresh LB medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/mL), and cultured at 37 °C until OD600 reached 0.6–0.8. Recombinant protein expression was induced by adding isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1 mM, followed by cultivation at 16 °C for 16 h.

Following cell harvesting, E. coli pellets were lysed using a high-pressure homogenizer (Constant Systems TS Series, Northants, UK). The crude lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to remove cellular debris. Supernatant was subjected to affinity chromatography purification using Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose resin (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Protein concentration was quantified via the Bradford assay with bovine serum albumin (BSA) standards. Purified proteins were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

The 100 μL reaction mixture consisted of 100 mM NaH2PO4 (pH = 6.8), 2 mM DTT, 1 mM 2-oxoglutarate, 2 mM ascorbic acid, 1 mM ATP, 0.25 mM FeSO4, 50 μM substrate, and 3 μg of purified recombinant protein. Reactions were performed at 37 °C for 1 h in open tubes. Enzyme activity was initiated by protein addition and terminated with ice-cold methanol. After centrifugation (16,000 × g, 10 min), supernatants were subjected to HPLC analysis. Michaelis-Menten parameters (Km and Kcat values) were derived from nonlinear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism (Version 8.0.2, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Standard compounds

-

Apigenin, chrysin, naringenin, and pinocembrin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Dihydrokaempferol, pinobanksin, kaempferol, and galangin were purchased from Yuanye-Biotech. The compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to obtain standard stock solutions (50 mM).

Metabolite analysis

-

Metabolite analysis was performed using an Agilent 1,260 Infinity II HPLC system. Flavonoids were detected at 280 nm with separation achieved on a Luna C18(2) column (100 × 2.0 mm, 3 μm) maintained at 35 °C. The flow rate was set to 0.26 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% (v/v) aqueous formic acid (A) and methanol: acetonitrile (1:1, v/v) containing 0.1% (v/v) formic acid (B). The gradient program was as follows: 0–3 min, 20% B; 3–20 min, 50% B; 20–30 min, 50% B; 30–36 min, 70% B; 37 min, 20% B and 37–43 min, 20% B. Metabolites were confirmed and measured by comparison to standards using retention times and calibration curves. Mass spectra were acquired using Thermo Q Exactive Plus in the negative ion mode with a heated ESI source. The flow rate of the auxiliary gas was set to 10 l/min, the temperature of the auxiliary gas heater was adjusted to 350 °C, the sheath gas flow rate was configured as 40 l/min, the spray voltage was set at 3.5 kV, and the capillary temperature was maintained at 20 °C.

-

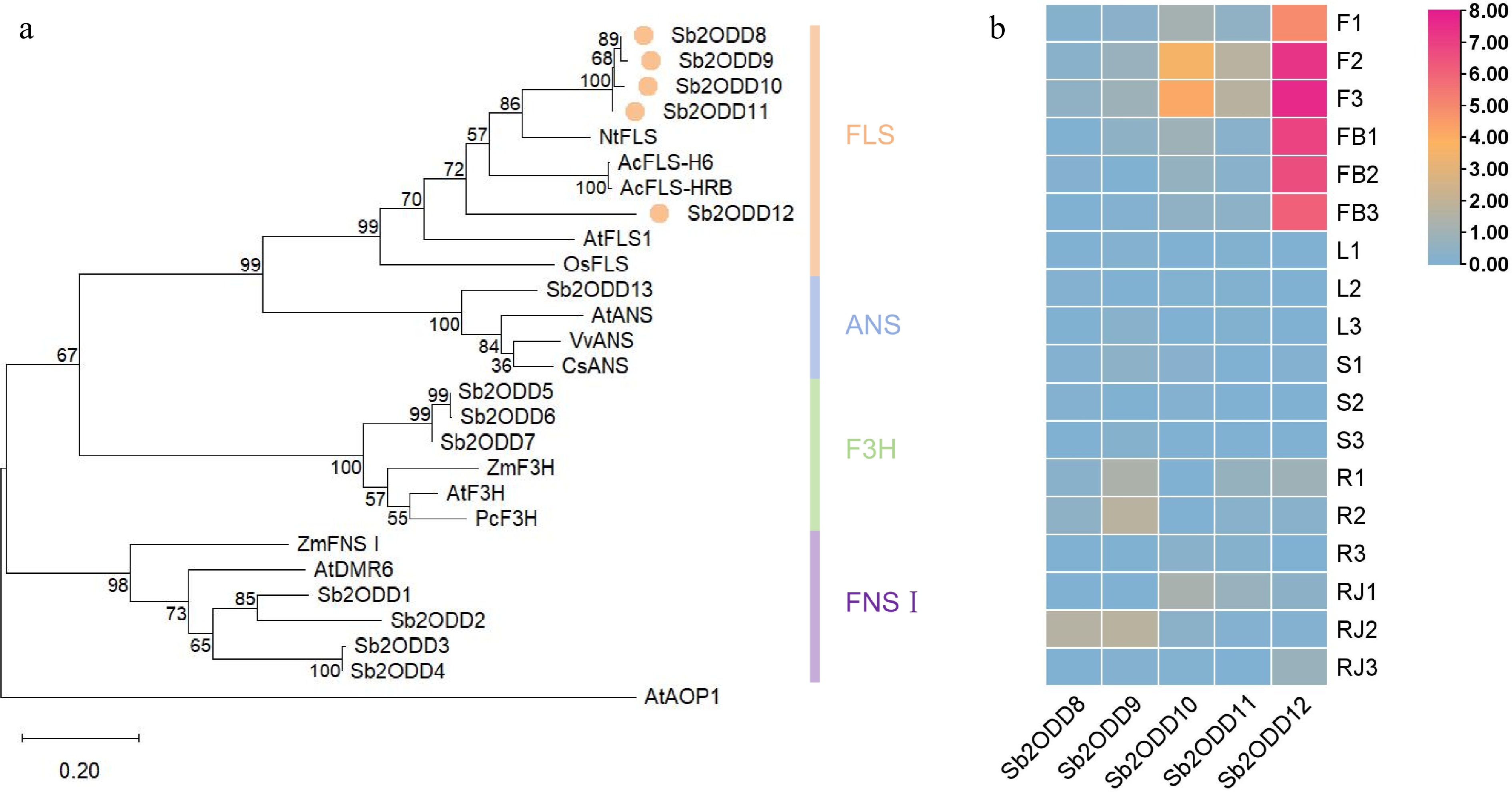

Our previous metabolomics analysis showed that S. baicalensis not only contains the classic 4'-hydroxyflavonol (kaempferol) but also 4'-deoxyflavonol (galangin)[5]. FLS is the key enzyme responsible for flavonol biosynthesis and may be involved in the biosynthesis of 4'-deoxyflavonol in S. baicalensis. Previously, the Sb2ODDs family in S. baicalensis were analyzed and genes with FNSI and F3H-related functions identified. To further explore the flavonol biosynthesis pathway in S. baicalensis, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using Sb2ODDs from the S. baicalensis genome (Fig. 2a), which showed that, in addition to the seven enzymes previously reported to cluster on the FNSI and F3H branches, there are five Sb2ODDs (named Sb2ODD8-Sb2ODD12) clustered with the reported FLS, and one (Sb2ODD13) clustered with ANS.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis and expression patterns of Sb2ODDs in S. baicalensis. (a) Phylogenetic tree of the 2ODD family members involved in flavonoid biosynthesis. The maximum-likelihood method was used to construct this tree with 1,000 replicate bootstrap support. The tree was rooted with AtAOP1. Accession numbers of the proteins used and their species names: NtFLS1, ABE28017, Nicotiana tabacum; AcFLS-H6, KY369209, Allium cepa; AcFLS-HRB, KY369210, Allium cepa; AtFLS1, At5g08640, Arabidopsis thaliana; OsFLS1, NP_001048230, Oryza sativa; AtANS, At4g22880; VvANS, ABM67590, Vitis vinifera; CsANS, AAT02642, Citrus sinensis; ZmF3H, NP_001130275, Zea mays; AtF3H, NP_190692; PcF3H, AAP57394, Petroselinum crispum; ZmFNSI, NP_001151167; AtDMR6, NP_197841; Sb2ODD1, Sb06g22120, Scutellaria baicalensis; Sb2ODD2, Sb02g38930; Sb2ODD3, Sb01g51050; Sb2ODD4, Sb01g51220; Sb2ODD5, Sb05g01401; Sb2ODD6, Sb05g01404; Sb2ODD7, Sb05g01631; Sb2ODD8, Sb0g04190; Sb2ODD9, Sb05g15130; Sb2ODD10, Sb05g15090; Sb2ODD11, Sb05g11030; Sb2ODD12, Sb05g11050; Sb2ODD13, Sb03g04100. (b) Tissue-specific expression heatmap of Sb2ODD8–Sb2ODD12. The color scale on the right represents the FPKM values normalized with log10. F, flower; FB, flower bud; L, leaf; S, stem; R, root; RJ, MeJA-treated root. the numbers behind indicated biological replicates.

Based on the FPKM values in the transcriptome data of different tissues of S. baicalensis[4], the expression patterns of the SbFLS gene family were analyzed (Fig. 2b). The results showed that the five Sb2ODDs were mainly expressed in flowers and roots, and were almost not expressed in stems and leaves. The expression levels of Sb2ODD8, Sb2ODD10, Sb2ODD11, and Sb2ODD12 in flowers were higher than those in roots, while only Sb2ODD9 had higher expression levels in roots and methyl jasmonate-treated roots than in flowers and flower buds. Among them, Sb2ODD12 had the highest expression levels in flowers and flower buds, and maybe the main gene responsible for flavonol biosynthesis in flowers.

Structural characteristics of S. baicalensis FLS gene family proteins

-

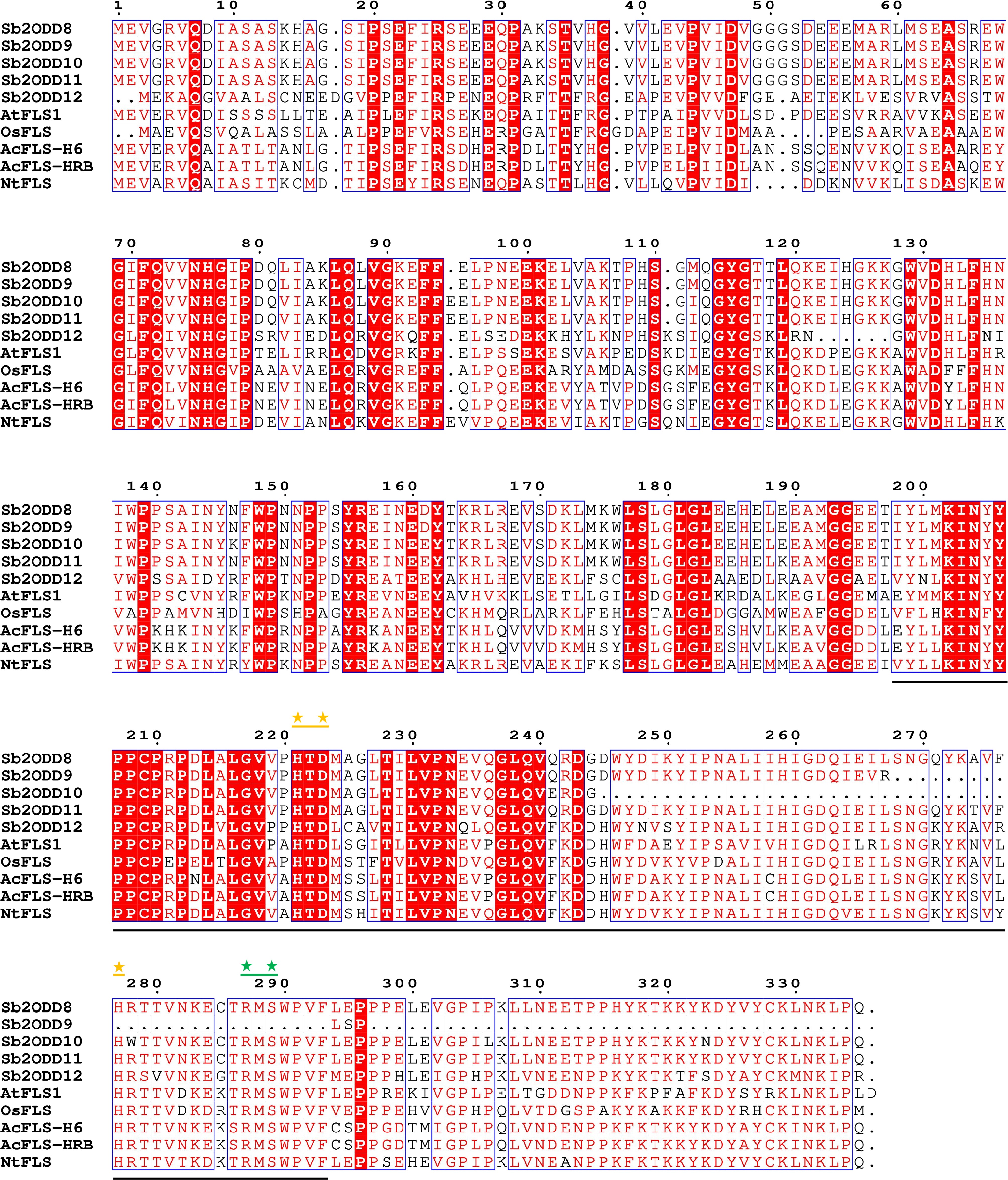

By comparing the FLS amino acid sequences of S. baicalensis with those of other reported species, the results showed that the proteins encoded by the Sb2ODD8, Sb2ODD11, and Sb2ODD12 genes in S. baicalensis have the conserved domains of 2-oxoglutarate and Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenase, including the important amino acid residues for binding Fe(II) and 2-oxoglutarate (Fig. 3). However, Sb2ODD9 and Sb2ODD10 lack the key conserved domains. According to the reported positions of Sb2ODDs on the chromosomes of S. baicalensis[16], the analysis showed that Sb2ODD8 (Sb0g04190) located on chromosome 0, Sb2ODD9 (Sb05g15130), Sb2ODD10 (Sb05g15090), Sb2ODD11 (Sb05g11030), and Sb2ODD12 (Sb05g11050) are all located on chromosome 5. Sb2ODD9 and Sb2ODD10 are tandem duplication genes, and so are Sb2ODD11 and Sb2ODD12.

Figure 3.

Sb2ODDs and other species FLS sequences alignment. Underlined regions indicates conserved domains which coordinate Fe(II) binding and 2-oxoglutarate binding. Yellow asterisks mark amino acid residues important for Fe(II) binding. Green asterisks mark amino acid residues important for 2-oxoglutarate binding.

A premature stop mutation in gene Sb2ODD9 truncated the protein to 271 residues, while the 265 amino acids in the N-terminal completely match Sb2ODD8. The C-terminal deletion of Sb2ODD9 abolishes the 2-oxoglutarate-binding domain, which may result in loss of function. Compared with Sb2ODD11, Sb2ODD10 lacks amino acids 245–280 of Sb2ODD11, a region that constitutes the conserved 2-oxoglutarate/Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenase domain. The amino acid sequence similarity between Sb2ODD11 and Sb2ODD12 is only 58.04%. However, the amino acid sequence similarity between Sb2ODD8 and Sb2ODD11 is 98.21%. This implies that Sb2ODD8 and Sb2ODD11 may have similar enzymatic activities, while Sb2ODD12 has different enzymatic functions. The open reading frames of Sb2ODD8, Sb2ODD11, and Sb2ODD12 were obtained by RT-PCR, which were 1,008, 1,011, and 987 bp, respectively (Supplementary Table S2).

Bifunctional enzyme activity identification of Sb2ODD8, Sb2ODD11, and Sb2ODD12 in yeast

-

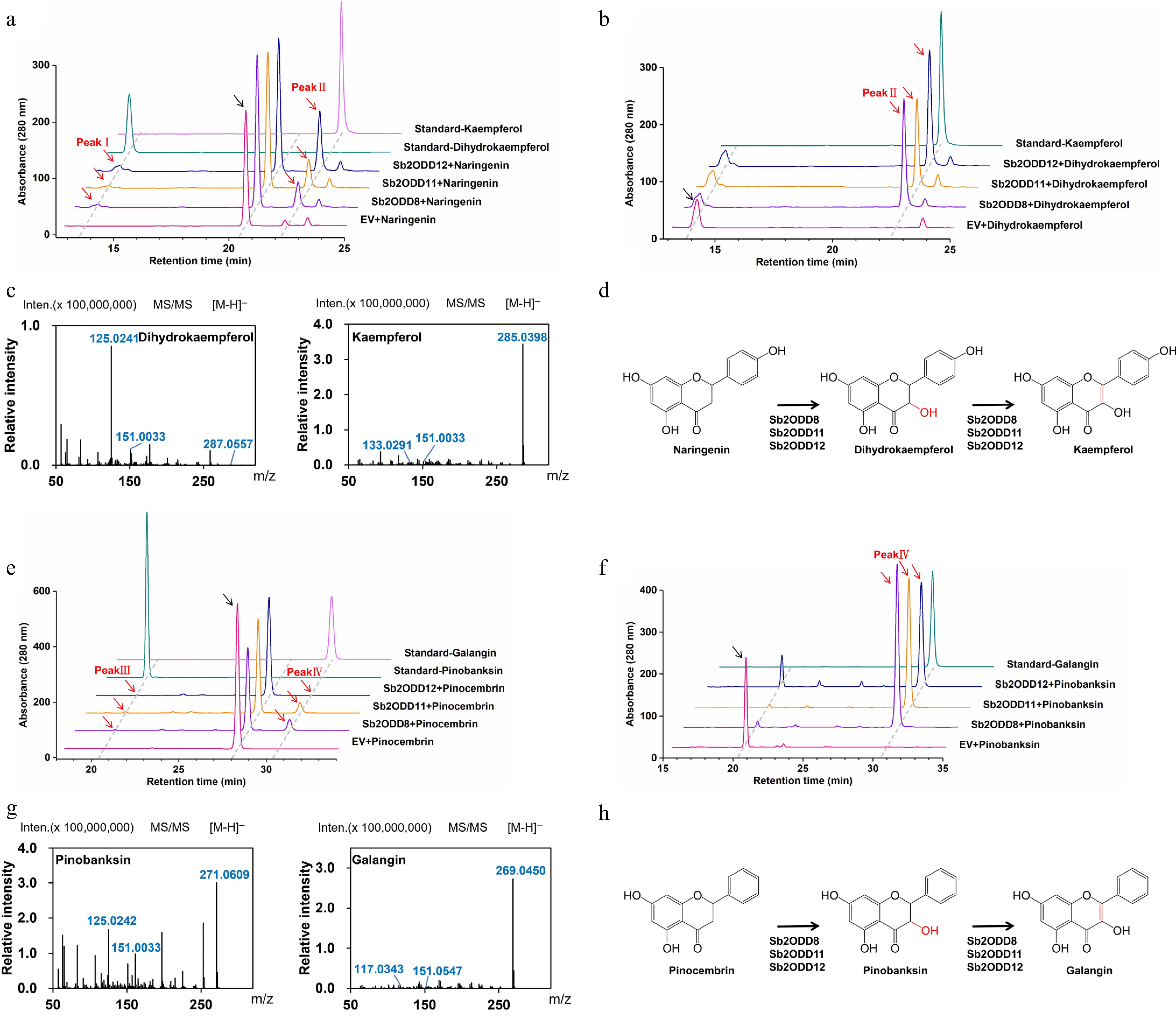

Through the S. cerevisiae heterologous expression system, the catalytic activities of the three enzymes Sb2ODD8, Sb2ODD11, and Sb2ODD12 were verified. HPLC analysis showed that when naringenin was used as the substrate, the three enzymes could catalyze the production of two characteristic product peaks (Fig. 4a). Comparative analysis with the dihydrokaempferol and kaempferol standards confirmed that all three enzymes exhibit bifunctional activity. In assays employing dihydrokaempferol as a substrate, HPLC analysis revealed that all three enzymes exclusively produced kaempferol as the reaction product (Fig. 4b). The products were identified by mass spectrometry as dihydrokaempferol (retention time 12.3 min, m/z 289 [M-H]−) and kaempferol (retention time 15.7 min, m/z 285 [M-H]−) (Fig. 4c), confirming that these enzymes have both F3H and FLS activities (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

In vivo yeast enzyme assays of Sb2ODDs. (a) Assays of activity in yeast in vivo. HPLC analysis of yeast samples incubated with naringenin: top, kaempferol standard; second, dihydrokaempferol standard; middle, Sb2ODD12, Sb2ODD11, Sb2ODD8 with naringenin; bottom, empty vector control (EV). (b) Assays of activity in yeast in vivo. HPLC analysis of yeast samples incubated with dihydrokaempferol: top, kaempferol standard; middle, Sb2ODD12, Sb2ODD11, Sb2ODD8 with dihydrokaempferol; bottom, empty vector control (EV). (c) MS/MS patterns of Sb2ODD12, Sb2ODD11, Sb2ODD8 products, which were identical to dihydrokaempferol and kaempferol standard. (d) The reaction was catalyzed by Sb2ODD12, Sb2ODD11, Sb2ODD8 using naringenin as a substrate. (e) Assays of activity in yeast in vivo. HPLC analysis of yeast samples incubated with pinocembrin: top, galangin standard; second, pinobanksin standard; middle, Sb2ODD12, Sb2ODD11, Sb2ODD8 with pinocembrin; bottom, empty vector control (EV). (f) Assays of activity in yeast in vivo. HPLC analysis of yeast samples incubated with pinobanksin: top, galangin standard; middle, Sb2ODD12, Sb2ODD11, Sb2ODD8 with pinobanksin; bottom, empty vector control (EV). (g) MS/MS patterns of Sb2ODD12, Sb2ODD11, Sb2ODD8 products, which were identical to pinobanksin and galangin standard. (h) The reaction was catalyzed by Sb2ODD12, Sb2ODD11, Sb2ODD8 using pinocembrin as a substrate.

When pinocembrin was added as the substrate, the three enzymes could also catalyze the formation of two products, namely pinobanksin and galangin (Fig. 4e). Meanwhile, when reactions were conducted with pinobanksin as a single substrate, all three enzymes produced galangin as the reaction product (Fig. 4f). The products were identified by mass spectrometry as pinobanksin (m/z 271 [M-H]−), and galangin (m/z 269 [M-H]−) (Fig. 4g). The results showed that the FLS activity of the three enzymes was relatively high, and they could efficiently catalyze the conversion of dihydrokaempferol to kaempferol and pinobanksin to galangin, respectively (Fig. 4d, h).

Enzyme kinetics analysis of Sb2ODD8, Sb2ODD11, and Sb2ODD12

-

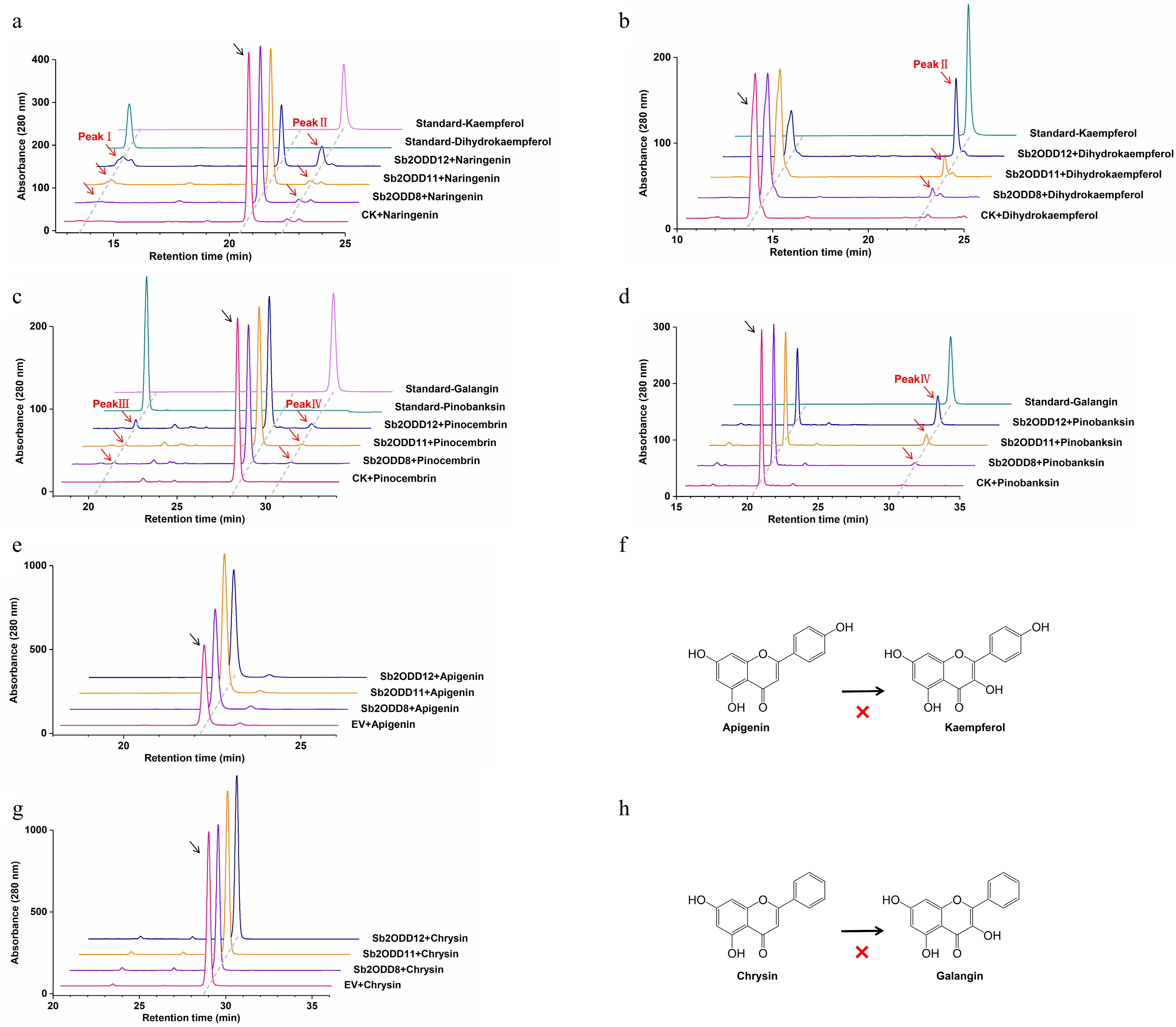

The three enzymes from the E. coli system were then purified (Supplementary Fig. S1), and the above results were also verified in the in vitro enzyme activity experiments (Fig. 5a−d). In addition, when apigenin and chrysin were added to the reaction systems of these three enzymes, no expected products (kaempferol and galangin) could be detected, indicating that they could not catalyze the conversion of flavones to flavonols (Fig. 5e−h).

Figure 5.

In vitro enzyme assays of Sb2ODDs. (a) HPLC analysis of enzyme activity in vitro using naringenin as a substrate: top, kaempferol standard; second, dihydrokaempferol standard; middle, Sb2ODD12, Sb2ODD11, Sb2ODD8 with naringenin; bottom, control check (CK). (b) HPLC analysis of enzyme activity in vitro using dihydrokaempferol as a substrate: top, kaempferol standard; middle, Sb2ODD12, Sb2ODD11, Sb2ODD8 with dihydrokaempferol; bottom, control check (CK). (c) HPLC analysis of enzyme activity in vitro using pinocembrin as a substrate: top, galangin standard; second, pinobanksin standard; middle, Sb2ODD12, Sb2ODD11, Sb2ODD8 with pinocembrin; bottom, control check (CK). (d) HPLC analysis of enzyme activity in vitro using pinobanksin as a substrate: top, galangin standard; middle, Sb2ODD12, Sb2ODD11, Sb2ODD8 with pinobanksin; bottom, control check (CK). (e) HPLC analysis of samples incubated with apigenin: top to bottom are Sb2ODD12, Sb2ODD11, Sb2ODD8 and empty vector control (EV). (f) Sb2ODDs cannot catalyze the formation of kaempferol from apigenin. (g) HPLC analysis of samples incubated with chysin: top to bottom are Sb2ODD12, Sb2ODD11, Sb2ODD8 and empty vector control (EV). (h) Sb2ODDs cannot catalyze the formation of galangin from chysin.

To compare the FLS activities of the three proteins Sb2ODD8, Sb2ODD11, and Sb2ODD12, enzyme kinetics experiments were carried out to analyze their differences in substrate affinity, reaction rate, and catalytic efficiency (Supplementary Fig. S2). The results showed that Sb2ODD11 had the highest affinity for dihydrokaempferol and pinobanksin (lowest Km values, Table 1). In comparison, Sb2ODD8 and Sb2ODD12 had higher Vmax and Kcat values for dihydrokaempferol and pinobanksin. The catalytic efficiency (Kcat/Km) of Sb2ODD8, Sb2ODD11, and Sb2ODD12 were also evaluated for different substrates. The Kcat/Km values of Sb2ODD8 and Sb2ODD12 for dihydrokaempferol were higher than those for pinobanksin, indicating that they preferentially catalyze the conversion of 4'-hydroxydihydroflavonol. In contrast, the Kcat/Km value of Sb2ODD11 for pinobanksin was higher than that for dihydrokaempferol, suggesting that it prefers to catalyze the conversion of 4'-deoxydihydroflavonol. Moreover, regardless of whether the substrate was dihydrokaempferol or pinobanksin, the order of FLS activity of these three enzymes was Sb2ODD11 > Sb2ODD12 > Sb2ODD8.

Table 1. Kinetic analysis of Sb2ODDs.

Enzyme Substrate Vmax (pkat/mg) Km (μM) Kcat (S) KcatlKm (M/S) Sb2ODD8 Dihydrokaempferol 360.80 125.30 242.22 1.93 × 106 Pinobanksin 404.30 143.10 271.42 1.90 × 106 Sb2ODD11 Dihydrokaempferol 105.50 10.60 71.07 6.70 × 106 Pinobanksin 92.86 8.60 62.56 7.27 × 106 Sb2ODD12 Dihydrokaempferol 542.20 55.81 356.95 6.40 × 106 Pinobanksin 361.70 54.17 238.12 4.40 × 106 -

S. baicalensis is rich in flavonoids, particularly renowned for containing bioactive 4'-deoxyflavonoids[3]. To date, the structural genes involved in the 4'-deoxyflavonoid biosynthetic pathway in S. baicalensis, including SbPAL, SbCLL-7, SbCHS-2, SbCHI, SbF3H, and SbFNSII-2, have been characterized[17,18], with the exception of SbFLS (Fig. 1). Baicalein, a representative 4'-deoxyflavone, has been successfully synthesized de novo in both Escherichia coli and Pichia pastoris[19,20] following the identification of the enzymes. Galangin, belonging to the 4'-deoxyflavonol class, exhibits significant pharmacological activity with demonstrated health benefits. However, the absence of SbFLS identification has become a limiting factor for galangin production through metabolic engineering[21,22]. To address this gap, SbFLS was characterized in S. baicalensis.

The DOXC47 subfamily of the 2ODD family comprises both flavonol synthase (FLS) and anthocyanidin synthase (ANS)[8]. Based on our previous genome-wide analysis of Sb2ODDs, six Sb2ODD members were identified within the DOXC47 subfamily[16]. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that five Sb2ODDs clustered with FLSs from other species, while one Sb2ODD grouped with ANS (Fig. 2a). Through amino acid sequence alignment, three full-length SbFLSs were cloned (Sb2ODD8, Sb2ODD11, and Sb2ODD12), all containing the conserved domains characteristic of 2-oxoglutarate binding domain and ferrous iron binding domain (Fig. 3). Sb2ODD12 exhibited the highest expression levels in flowers and flower buds (Fig. 2b), suggesting its potential role as the major effector gene for flavonol biosynthesis.

Previous studies have shown that Sb2ODD7 is a monofunctional F3H enzyme responsible for converting flavanones to dihydroflavonols, catalyzing the conversion of naringenin to dihydrokaempferol and pinocembrin to pinobanksin[16]. In this study, it was found that Sb2ODD8, Sb2ODD11, and Sb2ODD12 sequentially catalyze both naringenin and pinocembrin (Figs 4 and Fig. 5a−d), first generating the intermediate dihydroflavonols (dihydrokaempferol and pinobanksin) through their F3H activity, then further converting these to kaempferol and galangin via their FLS function. None of these enzymes could catalyze the conversion of apigenin or chrysin to kaempferol or galangin (Fig. 5e−h), indicating that the transformation from flavanones to flavonols requires initial F3H-catalyzed formation of dihydroflavonols followed by FLS-mediated desaturation to produce flavonols[10−12].

The structural difference between kaempferol and galangin lies in whether the B-ring contains a 4'-hydroxy group. Enzyme activity assays demonstrated that Sb2ODD8, Sb2ODD11, and Sb2ODD12 possess bifunction F3H/FLS activity, consistent with the known functions of AtFLS1, CitFLS, and OsFLS[10−12]. However, these enzymes exhibit differences in substrate preference. AtFLS1, CitFLS, and OsFLS are capable of catalyzing the conversion of dihydrokaempferol (4'-hydroxydihydroflavonol) into kaempferol, and there have been no reports on their ability to catalyze pinobanksin (4'-deoxydihydroflavonol). In S. baicalensis, Sb2ODD11 exhibited higher catalytic activity toward pinobanksin than dihydrokaempferol, whereas Sb2ODD8 and Sb2ODD12 showed the opposite preference, demonstrating greater activity toward dihydrokaempferol than pinobanksin (Table 1). This suggests that Sb2ODDs may have undergone functional differentiation during evolution to adapt to specific metabolic requirements, particularly demonstrating uniqueness in the biosynthesis of 4'-deoxyflavanol (such as galangin). The differences not only highlight the novelty of Sb2ODDs but also provide new insights and potential tools for metabolic engineering of flavanol biosynthesis.

The high amino acid sequence similarity between Sb2ODD8 and Sb2ODD11 suggests their close evolutionary relationship and conserved enzymatic functions, which correlate with their similar catalytic activities toward dihydrokaempferol and pinobanksin. Chromosomal localization analysis provides evolutionary insights into these functional differences. Sb2ODD8 is located on chromosome 0, while Sb2ODD11 and Sb2ODD12 reside on chromosome 5. This distinct chromosomal distribution suggests that Sb2ODD8 may have emerged earlier in the evolutionary history of S. baicalensis, with Sb2ODD11 and Sb2ODD12 likely arising later through gene duplication events. Tandemly duplicated genes on the same chromosome often undergo functional divergence during evolution. Although initially possessing similar functions, selective pressures may drive these duplicated genes to acquire new functions or undergo functional fine-tuning. Such functional modifications are typically accompanied by amino acid sequence changes to accommodate novel catalytic requirements.

-

In summary, three flavonol synthase (FLS) genes, Sb2ODD8, Sb2ODD11, and Sb2ODD12 were identified and characterized in S. baicalensis. These enzymes exhibit bifunctional F3H/FLS activities, converting flavanones to dihydroflavonols, and then to flavonols. Enzyme kinetics revealed distinct substrate preferences, with Sb2ODD11 showing higher activity towards 4'-deoxydihydroflavonols and Sb2ODD8 and Sb2ODD12 preferring 4'-hydroxydihydroflavonols. These findings provide valuable insights into the biosynthesis of flavonols in S. baicalensis, and offer essential information for metabolic engineering of flavonol production.

This work is sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32470280), the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (22ZR1479500), the Special Fund for Scientific Research of Shanghai Landscaping & City Appearance Administrative Bureau (G242403 and G252405), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (YDZX20223100001003, YDZX20243100004002), and funding for Shanghai science and technology promoting agriculture from Shanghai Agriculture and Rural Affairs Commission (Hu Nong Ke Chan Zi [2023] No.8).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhao Q, Cui M; performed the experiments: Cui M, Zhu S, Chen Q; draft manuscript preparation: Zhu S, Chen Q; assisted with the LC-MS analysis: Kong Y, Xie L; revised the manuscript: Cui M, Zhao Q. All the authors analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

The genome of S. baicalensis is available in the National Genomics Data Center (https://bigd.big.ac.cn/gwh) with Accession No. GWHAOTC00000000. RNA sequencing data are available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra, under Accession No. SRP156996. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Sanming Zhu, Qiuying Chen

- Supplementary Table S1 The list of primers used for cloning the predicted Sb2ODDs in S.

- Supplementary Table S2 The list of sequences of the genes identified in this study.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 SDS PAGE analysis of the purified Sb2ODD8, Sb2ODD11, and Sb2ODD12.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Enzymatic kinetic curve of Sb2ODDs.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu S, Chen Q, Kong Y, Xie L, Zhao Q, et al. 2025. Characterization of three flavonol synthases involved in the biosynthesis of 4'-deoxyflavonol in Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. Medicinal Plant Biology 4: e035 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0025-0033

Characterization of three flavonol synthases involved in the biosynthesis of 4'-deoxyflavonol in Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi

- Received: 15 July 2025

- Revised: 02 September 2025

- Accepted: 05 September 2025

- Published online: 03 November 2025

Abstract: Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi is a traditional Chinese medicinal herb that is rich in 4'-deoxyflavonoids. Galangin (4'-deoxyflavonol) is a bioactive natural product found in S. baicalensis. To date, little is known about the biosynthesis of galangin. In this study, three flavonol synthases, Sb2ODD8, Sb2ODD11, and Sb2ODD12 were characterized from S. baicalensis. They exhibited bifunctional F3H/FLS activities (predominantly FLS), converting flavanones to dihydroflavonols, and then to flavonols. Enzyme kinetics revealed that they had distinct substrate preferences: Sb2ODD11 showed higher catalytic efficiency towards pinobanksin (4'-deoxydihydroflavonol), while Sb2ODD8 and Sb2ODD12 preferred dihydrokaempferol (4'-hydroxydihydroflavonol). These findings provide insights into the biosynthesis of flavonols in S. baicalensis and offer valuable information for metabolic engineering of flavonol production.

-

Key words:

- Scutellaria baicalensis /

- Flavonol synthase /

- Flavanone 3-hydroxylase /

- 4'-deoxyflavonol /

- Biosynthesis