-

Parthenium hysterophorus L. (Asteraceae: Heliantheae), commonly referred to as Parthenium, white top, congress grass, feverfew, or carrot weed, is recognized as one of the most invasive and noxious weeds across the globe[1]. It poses a severe threat to both natural and agricultural ecosystems, impacting biodiversity, agriculture, and human health globally[2]. The rapid spread of this invasive species has raised significant concerns, as its presence leads to reduced crop yields, displacement of native flora, and adverse effects on livestock due to its toxic properties[3]. The allelopathic nature of P. hysterophorus further exacerbates its invasive potential, making its control a significant challenge for farmers and environmentalists as it suppresses the growth of surrounding vegetation, reduces crop yields, and disrupts native plant communities. Conventional methods for managing Parthenium, including mechanical removal and chemical herbicides, have proven to be insufficient due to various limitations[4−6]. The ability of weeds to produce a vast number of seeds, their resilience to harsh environmental conditions, and the ineffectiveness of conventional control measures necessitate the development of alternative strategies for sustainable management[7]. Herbicide resistance, environmental concerns, and high costs associated with chemical control methods have led researchers to explore biological control as a viable alternative[8]. It has been reported that Bucculatrix parthenica, Epiblema strenuana, Listronotus setosipennis, Smicronyx lutulentus, and Zyogramma bicolorata are all effective against P. hysterophorus[9−11].

One promising approach is the use of indigenous fungal isolates (isolated from infected weeds) that have a natural ability to suppress weed populations. The use of native fungal isolates as biocontrol agents presents an environmentally friendly and sustainable method for managing Parthenium infestations[12,13]. Unlike chemical herbicides, which may cause ecological imbalances, fungal isolates specifically target the weed, reducing its growth and reproductive potential[14]. Extensive research has been conducted to explore the efficacy of indigenous fungal plant pathogens in controlling invasive weeds, including P. hysterophorus[15]. The potential of fungi as mycoherbicides is particularly promising, as they can be mass-produced and applied effectively in various environmental conditions[16]. Puccinia abrupta var. partheniicola (commonly called winter rust) showed a very promising effect against the Parthenium weed[17−20]. The success of a fungal biocontrol agent depends on its ability to grow and sporulate efficiently in synthetic media, which facilitates mass production of its infective stages, such as spores or vegetative mycelium[21]. Understanding the environmental conditions that influence fungal growth and sporulation is crucial for optimizing their effectiveness as biocontrol agents[22]. Factors such as temperature, pH, relative humidity, incubation time, and nutrient availability play a significant role in determining the pathogen‘s virulence and survival[23]. By identifying the most suitable growth conditions, the efficacy of fungal biocontrol agents can be enhanced, ensuring their successful establishment in field conditions. The integration of mycoherbicides into weed management programs can offer a long-term solution for controlling Parthenium, benefiting both agricultural productivity and biodiversity conservation[24,25].

The present study focuses on evaluating the optimal conditions required for the colony growth and sporulation of fungal isolates that can be utilized for the biocontrol of P. hysterophorus. The fungal isolates were cultured on PDA media and subjected to various levels of pH, temperature, and incubation time to determine the best interactive parameters for pathogen proliferation. The findings of this research contribute to understanding the ecological survival of fungal isolates and their potential application in integrated weed management programs. This knowledge will aid in the development of a sustainable and efficient biocontrol strategy for managing Parthenium infestations, reducing reliance on chemical herbicides, and promoting ecological balance.

-

Infected leaves of the Parthenium plant were gathered from nearby areas of Maharishi Markandeshwar (Deemed to be University), Ambala, Haryana, India. The surface sterilization of collected samples of Parthenium leaves was done by first washing under running tap water. To remove dirt and debris, plant leaves were sorted again and thoroughly rinsed using autoclaved distilled water. Following rinsing, the leaf surface was disinfected with 70% ethanol for 1 min and sodium hypochlorite (1%) for 5 min[26]. The plant leaves were thoroughly cleaned four to five times with autoclaved distilled water to eliminate any surface chemicals. Subsequently, the leaves were placed on autoclaved tissue paper and left for 30 min. Then, after proper drying and sterilization of leaves, they were used to isolate the fungi[27]. Following adequate drying, the surface-sterilized Parthenium leaves were sliced into smaller segments and placed on the petri plates containing PDA (Potato dextrose agar) medium enhanced with streptomycin. Then, the petri plates were incubated at 25 °C for 5–7 d and subsequently, the fungi were subcultured onto freshly prepared PDA plates to obtain pure cultures. PDA slants were used to maintain the pure culture of the isolated fungus and preserved the slants at 4 °C[25].

Identification of isolated fungi

-

Fungal isolates were first identified based on morphological characteristics of their spores and spore-producing structures with standard descriptions in the literature[28], and the isolates were initially assigned to a genus. Fungal identification was performed by amplifying and sequencing the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region using ITS1 and ITS4 primers, which served as the primary basis for species-level identification and GenBank submissions, as the ITS region is widely recognized as the most informative marker for fungal taxonomy[29]. BLAST analysis was done, followed by the formation of a phylogenetic tree, and sequence similarities were determined.

In vitro pathogenicity assessment of fungal isolates

-

The disc plate technique was performed to check the pathogenicity of fungal isolates. The 8 mm discs from the five-day-old culture of each fungal strain were removed aseptically and then placed on the lid of the sterilized petri plates. Healthy Parthenium leaves (sterilized by 70% ethanol) were placed on the lower side of the petri plates on wet filter paper. After that petri plates were incubated at 28–30 °C for 72 h. Spores dispersed from the upper lid to the leaves resulted in disease symptoms. Observations were made for the appearance of symptoms after 3 d of incubation[30].

Optimization of various growth parameters

-

The optimization of fungal growth parameters was carried out through a series of controlled experiments. The selected fungal isolates were cultured on PDA media under varying conditions to determine the optimal growth conditions. Growth was assessed by measuring the colony diameter at regular intervals[31]. The temperature range (15–35 °C) and pH range (5.0–7.0) were selected based on the known biology of mesophilic fungi like Alternaria, which typically grow best in moderate temperatures and slightly acidic to neutral pH conditions. The effect of temperature was studied in PDA solid media at different temperature conditions, i.e., 15, 20, 25, 30, and 35 °C[32]. The discs of 8 mm diameter were removed using a sterile cork borer from seven-day-old fungal cultures that were actively developing. Petri dishes were employed in triplicate for each temperature range maintained in the BOD incubator. Diameter was used as a measure of growth since it is a consistent indicator of fungal expansion. After 9 d of incubation, the area of radial expansion in two opposite directions was calculated for each fungal colony to estimate its size. Before sterilization, PDA media were adjusted to a pH of 5, 5.5, 6, 6.5, and 7 on separate plates that contained 15–20 mL of the medium. The isolated fungal isolates were cultured in the centre of Petri dishes for 9 d before being used as inoculum discs. Each pH range was tested in triplicate in separate Petri plates that were incubated to check growth at 25 °C for 9 d. Petri plates with PDA culture medium (about 15–20 mL) were used for incubation. Petri dishes were inoculated with discs of inoculum taken from a fungal culture that was 7 d old and vigorously developing. For each incubation period, three identical Petri plates were utilised. Incubation lasted 3, 5, 7, and 9 d at a temperature of 25 °C[33,34].

Statistical analysis

-

Each experiment was conducted in triplicate. Experimental results were analyzed following appropriate methods, such as Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and multiple regression analysis. Critical differences were computed at the p = 0.05 level after single-way ANOVA.

-

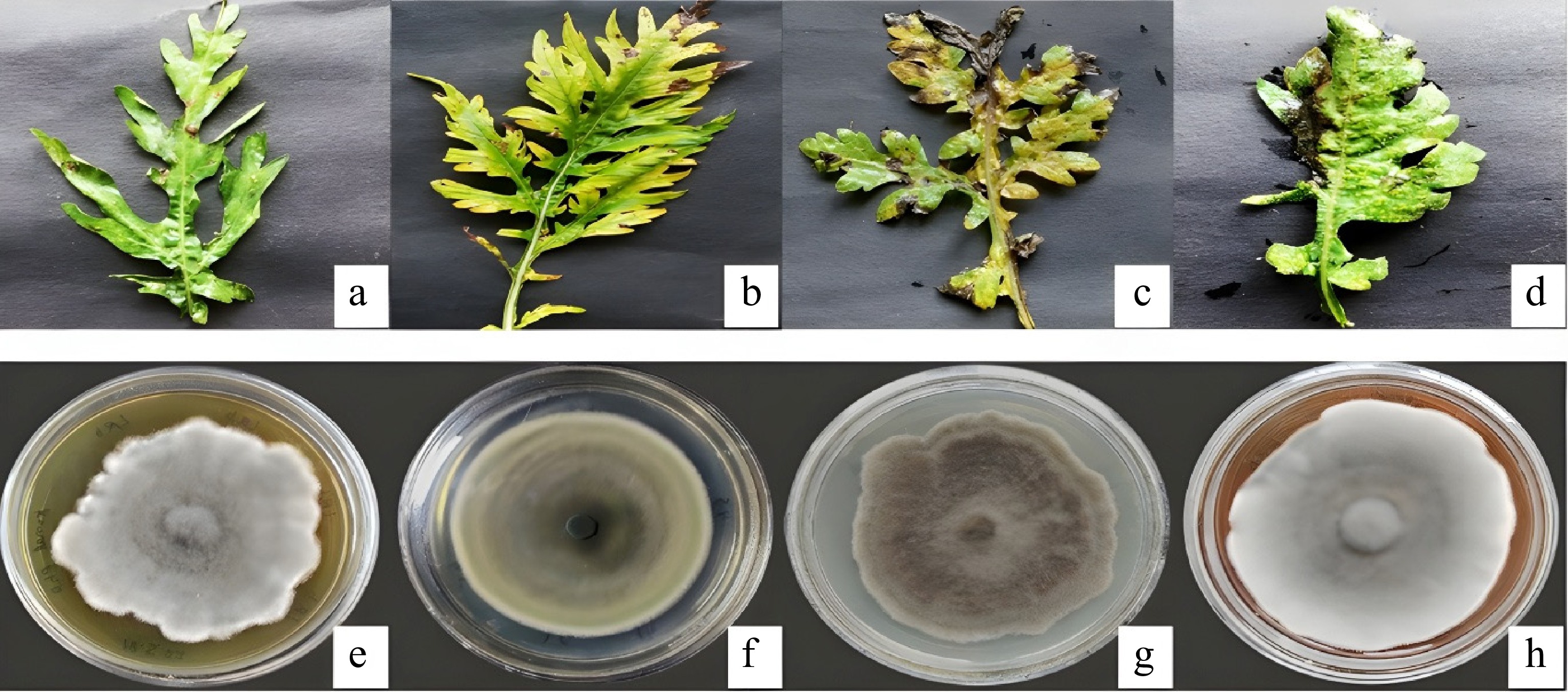

A population of Parthenium hysterophorus (Congress grass) in the MMU region of Ambala district was infected by black leaf spot disease. Fungal colonies isolated on PDA yielded four different types, which were microscopically belonging to the Alternaria (Fig. 1). Molecular characterization was conducted by GeneOmbio Technologies Pvt. Ltd, Pune, Maharashtra, using ITS region sequencing with universal primers ITS1 and ITS4. BLAST analysis identified the isolates as Alternaria alternata strain PHMMU2 and three strains of Alternaria macrospora (PHMMU1, PHMMU3, and PHMMU4). The sequences were submitted to the NCBI gene bank with accession numbers PQ483096, PQ433119, PQ483101, and PQ483102 (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Cultural characteristics of fungal isolates isolated from infected Parthenium leaves: (a)–(d) Diseased Parthenium leaves. (e) Alternaria macrospora strain PHMMU1. (f) Alternaria alternata strain PHMMU2. (g) Alternaria macrospora strain PHMMU4. (h) Alternaria macrospora strain PHMMU3.

Table 1. List of fungal isolates used in the study with their accession number.

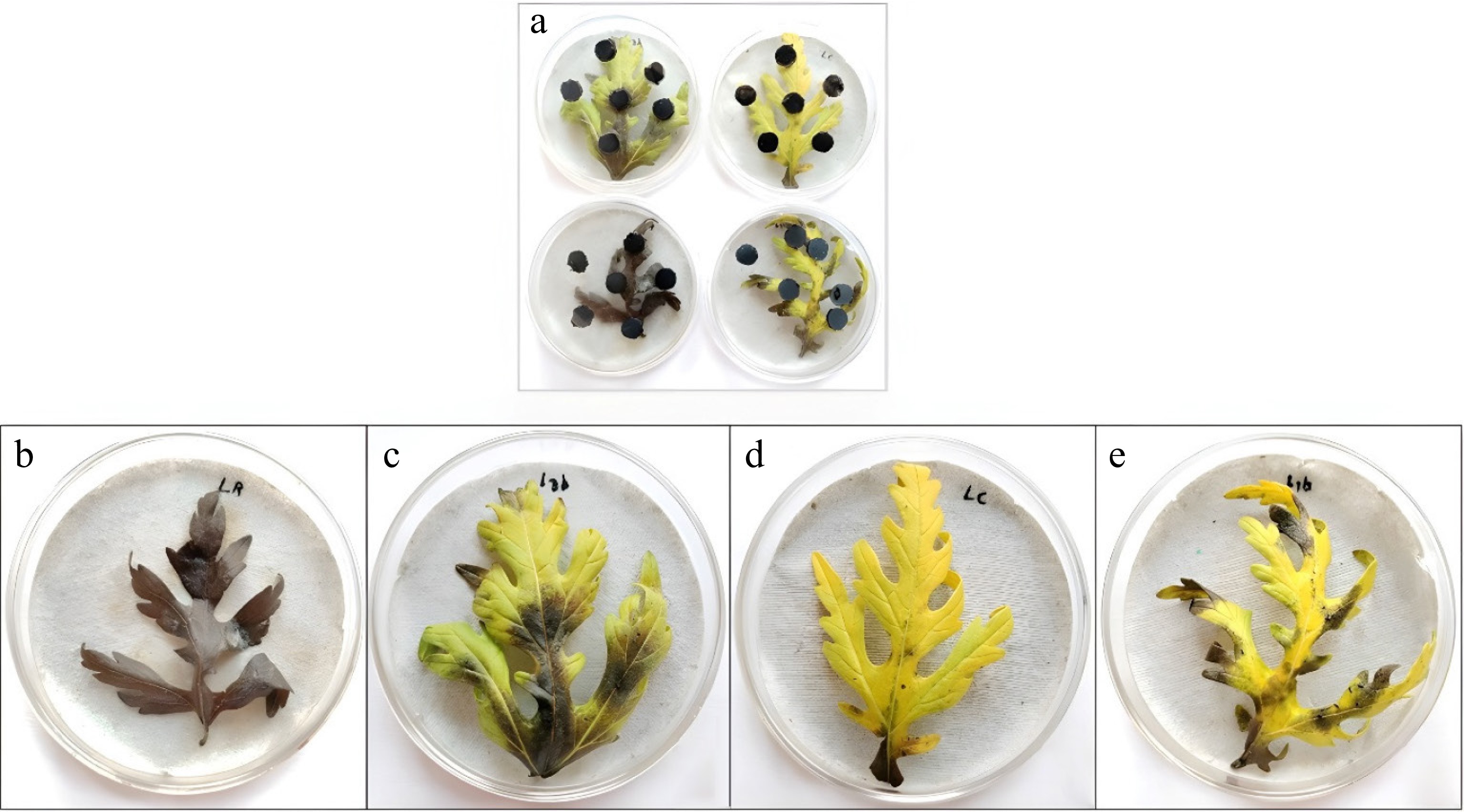

Sr. no. Plant part Fungal name Strain no. Accession no. 1. Leaf Alternaria macrospora PHMMU1 PQ433119 2. Leaf Alternaria alternata PHMMU2 PQ483096 3. Leaf Alternaria macrospora PHMMU3 PQ483101 4. Leaf Alternaria macrospora PHMMU4 PQ483102 The identity of these isolates was verified by comparing their ITS region sequences with those of reference Alternaria species available in GenBank. In vitro inoculation of fungi produced typical disease symptoms on healthy leaves using the disc plate technique, and re-isolation confirmed the pathogens' identity through cultural characteristics, thus fulfilling Koch's postulates and establishing their pathogenicity to P. hysterophorus (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Disc plate method. (a) Spores released from the fungal culture discs and penetration into Parthenium leaves. (b)–(e) Symptoms on Parthenium leaves after 72 h at 25 °C.

Experiments were conducted to optimize the temperature and pH conditions for pathogenic fungi within a temperature range of 15–35 °C. Typically, a lower pH environment is beneficial to the growth of fungi. The media were subjected to varying pH levels (pH 5–7) to investigate their impact on diverse fungal species over a period of 9 d. Upon subjecting the fungal isolates to varying temperatures, it was observed that the growth of the fungal isolates was significantly hindered at both 15 and 35 °C, which represent the temperature extremes for optimal growth. The optimal temperature for fungal isolates was determined to be 28 °C in PDA medium. However, little and least mycelial growth was observed at 15 and 35 °C, respectively. Similarly, on subjecting the fungal isolates to different pH levels, the results indicated that pH 7.0 provides the most favourable conditions for fungal growth. Additionally, incubation time positively influences colony diameter, with maximum expansion observed after 9 d of incubation. The colony diameters of four fungal isolates were analysed to assess growth differences among species.

Statistical analysis

-

The multiple regression analysis performed on the experimental data (Supplementary Table S1) provides valuable insights into how different factors, such as fungus type, time, pH, and temperature, affect the colony diameter of fungal isolates. The overall model is highly significant, with an F-value of 29.48 and a p-value of 0.001, indicating that the combined influence of predictor variables explains a substantial proportion of the variation in colony diameter. The R-squared value of 93.72% suggests that the model accounts for 94% of the variability in colony diameter. In comparison, the adjusted R-squared of 93.59% and predicted R-squared of 93.37% further validate the model and its predictive accuracy. Among the independent variables, time (d) had the most effect on colony growth, with a high F-value of 114.94 and a p-value of 0.001, indicating that colony diameter increases significantly with time. Temperature (°C) also exhibited a strong influence, with an F-value of 25.12 and a p-value of 0.001, highlighting its critical role in determining fungal growth. The variable pH, however, showed a marginal effect on colony diameter, with a p-value of 0.05, suggesting that pH impacts growth. Still, the effect is less pronounced compared to time and temperature. Interestingly, fungal type showed a moderate influence on colony diameter with an F-value of 2.44 and a p-value of 0.065, indicating that the differences among the fungal isolates were not highly significant but could still contribute to variations in growth under different conditions. The lack-of-fit test produced a remarkably high F-value of 1,625.06 and a p-value of 0.001, suggesting that the model does not perfectly capture all the nuances of the data, potentially due to minor interactions or non-linearities not accounted for in the model. However, the pure error value is minimal (0.006), indicating that the variation in replicated measurements is negligible.

Analysis of main factors

-

The significance of the main factor analysis in ANOVA lies in its ability to identify and quantify the individual effects of each independent variable (factor) on the dependent variable. By analysing the main effects, ANOVA determines whether changes in factor levels result in statistically significant differences in the response variable. This analysis helps isolate the influence of each factor, allowing for an understanding of which factors significantly impact outcomes. Furthermore, the main factor analysis aids in optimizing experimental conditions by highlighting which factors contribute most to variability, guiding future improvements in the process.

Effect of fungal types

-

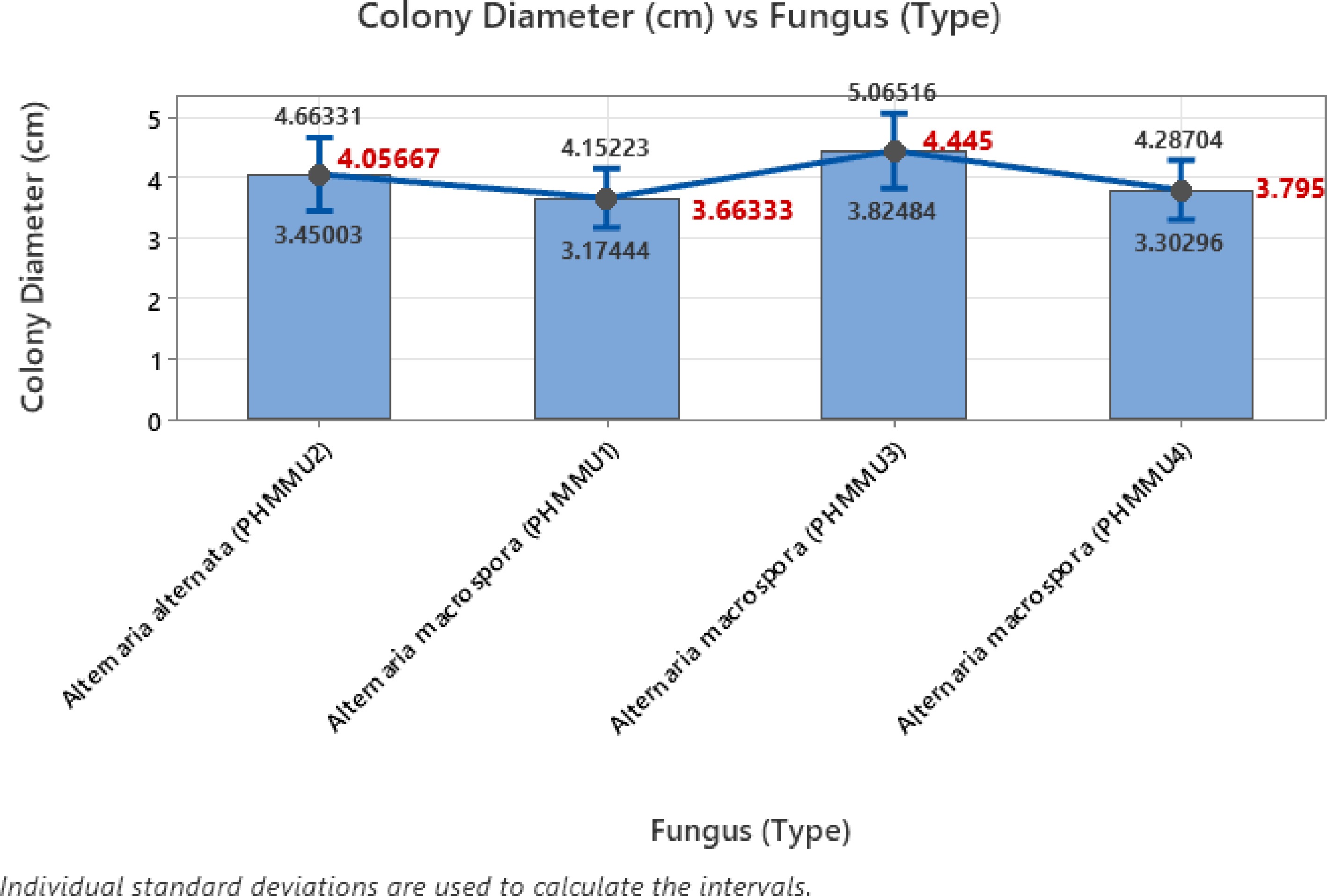

The one-way ANOVA analysis conducted to assess the effect of different fungal isolates on colony diameter revealed some insightful observations. The analysis included four fungal types, Alternaria alternata (PHMMU2) and three strains of Alternaria macrospora (PHMMU1, PHMMU3, and PHMMU4) with 60 observations for each type. The null hypothesis assumed that all mean colony diameters were equal, while the alternative hypothesis suggested that at least one mean was different. The analysis was performed at a significance level (α) of 0.05, and equal variances were assumed. The results showed that the F-value was 1.54, with a corresponding p-value of 0.204, indicating that the differences among the mean colony diameters of the four fungal types were not statistically significant. Since the p-value exceeds the 0.05 threshold, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected, implying that the colony diameters produced by these fungal types do not exhibit significant differences. Upon examining the descriptive statistics, Alternaria macrospora (PHMMU3) demonstrated the highest mean colony diameter of 4.445 cm, with a standard deviation of 2.401 cm and a 95% confidence interval ranging from 3.898–4.992 cm (Fig. 3). Conversely, Alternaria macrospora (PHMMU1) exhibited the lowest mean diameter of 3.663 cm, with a standard deviation of 1.893 cm and a 95% confidence interval between 3.117 and 4.210 cm. The mean diameters for Alternaria alternata (PHMMU2) and Alternaria macrospora (PHMMU4) were 4.057 and 3.795 cm, respectively, with corresponding confidence intervals indicating overlap among the groups. The pooled standard deviation (StDev) was 2.14986 cm, indicating some variability in colony diameters across the fungal types.

The error bar plot provides a visual representation of the 95% confidence intervals for the means of each fungal type. The overlapping confidence intervals among the four fungal types further reinforce the ANOVA results, suggesting that the observed differences in mean colony diameters are not statistically significant. Although slight variations in means exist, these differences are likely due to random variability rather than meaningful distinctions among the fungal types. Thus, the ANOVA analysis and the error bar plot together indicate that the colony diameters produced by different fungal types are relatively similar, with no statistically significant differences observed. This suggests that under the given experimental conditions, the fungal type does not substantially influence colony growth.

Effect of time

-

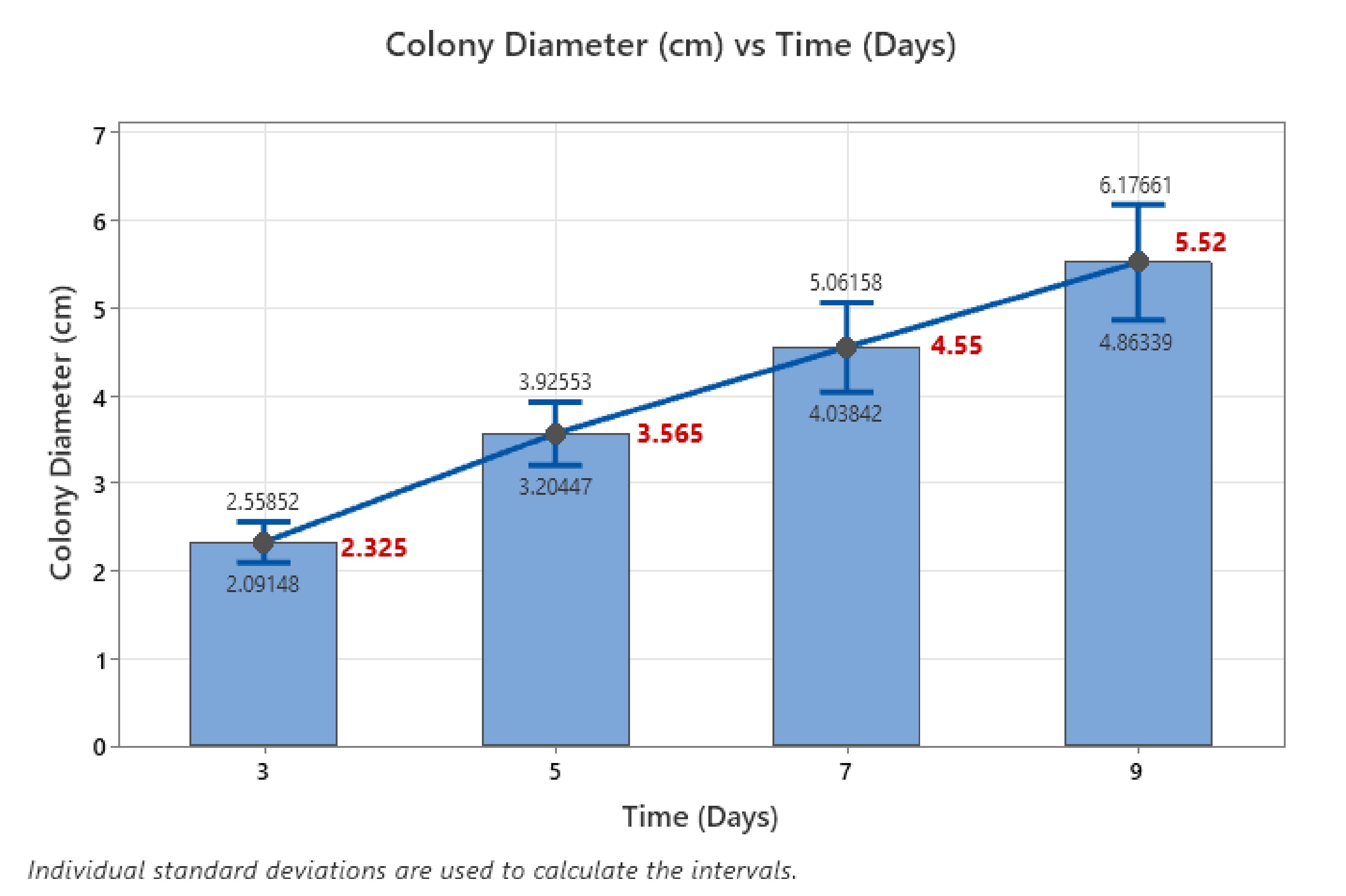

The one-way ANOVA conducted to evaluate the effect of time on colony diameter yielded statistically significant results, providing valuable insights into the growth dynamics of fungal colonies over time. The analysis tested the null hypothesis, which posited that the mean colony diameters across the four time points (3, 5, 7, and 9 d) were equal. The alternative hypothesis suggested that at least one mean was different. The analysis was conducted at a significance level (α) of 0.05, and equal variances were assumed. The results indicated a highly significant F-value of 34.12 with a corresponding p-value of 0.001, far below the 0.05 threshold. This compelling evidence led to the rejection of the null hypothesis, affirming that the mean colony diameters at different time intervals were indeed different. The adjusted sum of squares (Adj SS) for time was 336.4, and the mean square (Adj MS) was 112.147, indicating that a substantial portion of the total variation in colony diameter was attributable to the time factor. Upon the descriptive statistical analysis, a clear growth trend emerged over the observed time points. The mean colony diameter increased progressively from 2.325 cm on day 3 to 5.520 cm on day 9, highlighting a steady expansion in fungal growth with time (Fig. 4). The standard deviations for each time point showed a slight increase, reflecting some variability as growth progressed. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) further corroborated these findings. On day 3, the mean colony diameter fell between 1.864 and 2.786 cm, while by day 9, the confidence interval had expanded from 5.059 to 5.981 cm, demonstrating consistent growth.

The error bar plot visually reinforced this trend, with non-overlapping confidence intervals between most time points, indicating statistically significant differences in colony diameters as time progressed. The error bars for days 3 and 5, and days 7 and 9 showed distinct separation, reflecting a clear increase in colony size with time. The pooled standard deviation (StDev) was 1.81297, suggesting moderate variability across the different time points. In short, the ANOVA results and the error bar plot collectively underscore a significant effect of time on colony growth. The continuous increase in colony diameter over the 9 d indicates that time plays a critical role in determining fungal growth, with each subsequent time point exhibiting a marked increase in colony size.

Effect of temperature

-

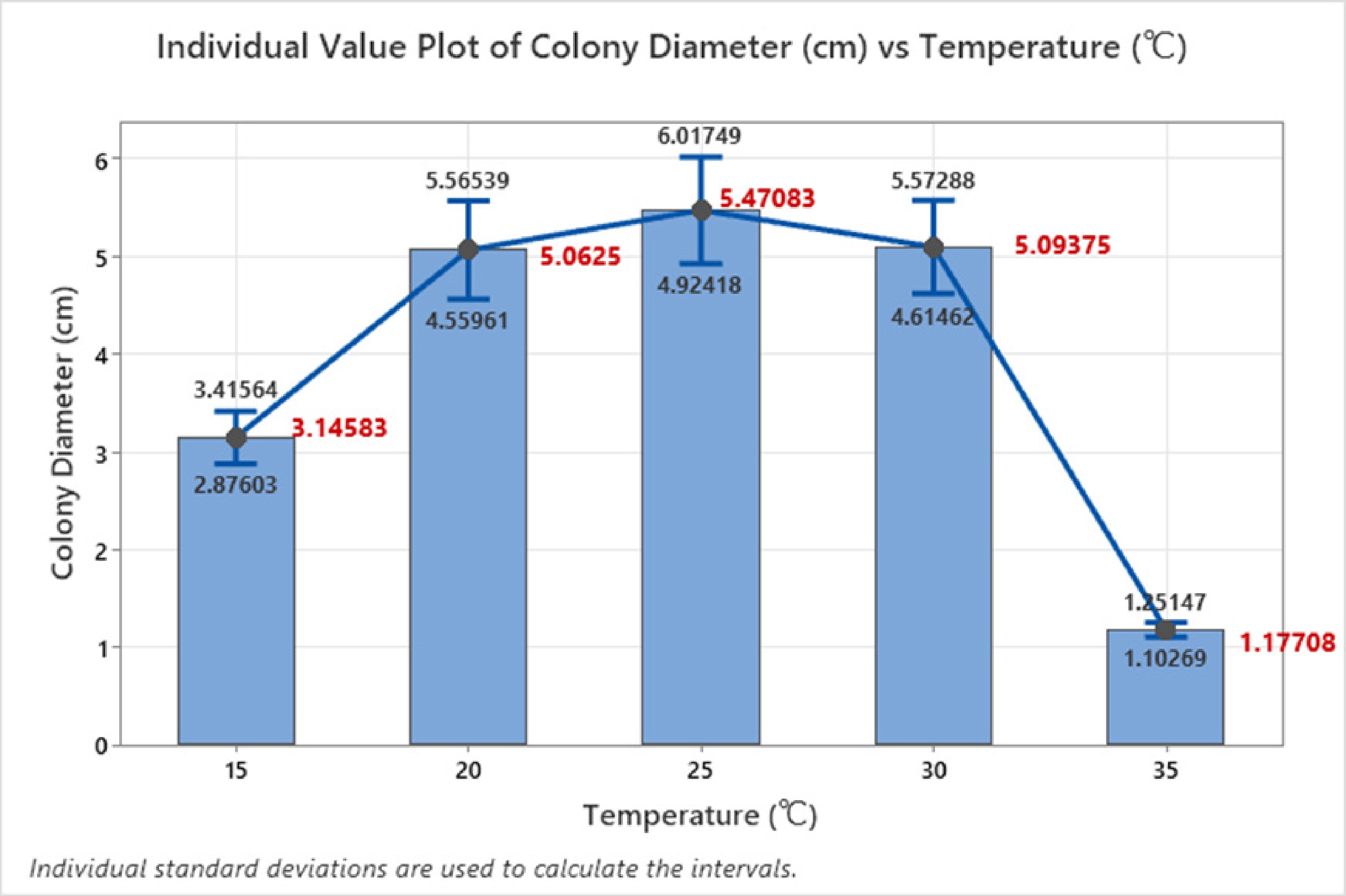

On a similar pretext, the one-way ANOVA analysis was performed to investigate the impact of temperature on the colony diameter, aiming to determine whether significant differences existed among the mean colony diameters at five different temperature levels (15, 20, 25, 30, and 35 °C). The null hypothesis suggested that all means were equal, while the alternative hypothesis proposed that at least one mean was different. The analysis was carried out at a significance level (α) of 0.05, assuming equal variances for the data. The results revealed a highly significant F-value of 77.60 with a corresponding p-value of 0.001, indicating that the differences in colony diameter across temperature levels were statistically significant. Since the p-value was well below the 0.05 threshold, the null hypothesis was rejected, confirming that temperature had a significant effect on fungal colony growth. The adjusted sum of squares (Adj SS) for temperature was 633.0, contributing a considerable proportion of the total variation, while the mean square (Adj MS) was 158.238. The error sum of squares was 479.2, with a mean square error of 2.039, suggesting relatively moderate variability across observations. Upon examining the means of colony diameter at different temperatures, an interesting pattern emerged. The mean colony diameter increased as the temperature rose from 3.146 cm at 15 °C to a peak of 5.471 cm at 25 °C, indicating that 25 °C was the optimal temperature for fungal growth (Fig. 5). However, beyond 25 °C, the colony diameter showed a slight decline, with the mean dropping to 5.094 cm at 30 °C and drastically falling to 1.177 cm at 35 °C, suggesting that higher temperatures may have inhibited fungal growth.

The standard deviations (StDev) for the different temperature levels indicated some variability, with a pooled standard deviation of 1.42796, suggesting moderate variation in colony diameter. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the means further reinforced these findings. At 25 °C, the confidence interval ranged from 5.065 to 5.877 cm, suggesting a higher and consistent growth rate. However, at 35 °C, the confidence interval shrank from 0.7710–1.5831 cm, reflecting significantly reduced growth and high sensitivity to extreme temperatures. The error bar plot visually confirmed these trends, with error bars for 25 and 30 °C overlapping slightly, indicating comparable growth at these temperatures. However, the error bars for 35 °C were distinct and positioned much lower, emphasizing the substantial drop in colony diameter at higher temperatures. The error bars for 15 and 20 °C also showed a noticeable progression toward higher growth as the temperature increased. Therefore, the analysis demonstrates that temperature significantly influences fungal colony growth, with 25 °C being the optimal temperature for maximizing colony diameter. Beyond this point, growth declines, especially at 35 °C, where the colony diameter drops drastically, suggesting that excessively high temperatures hinder fungal development.

Effect of pH

-

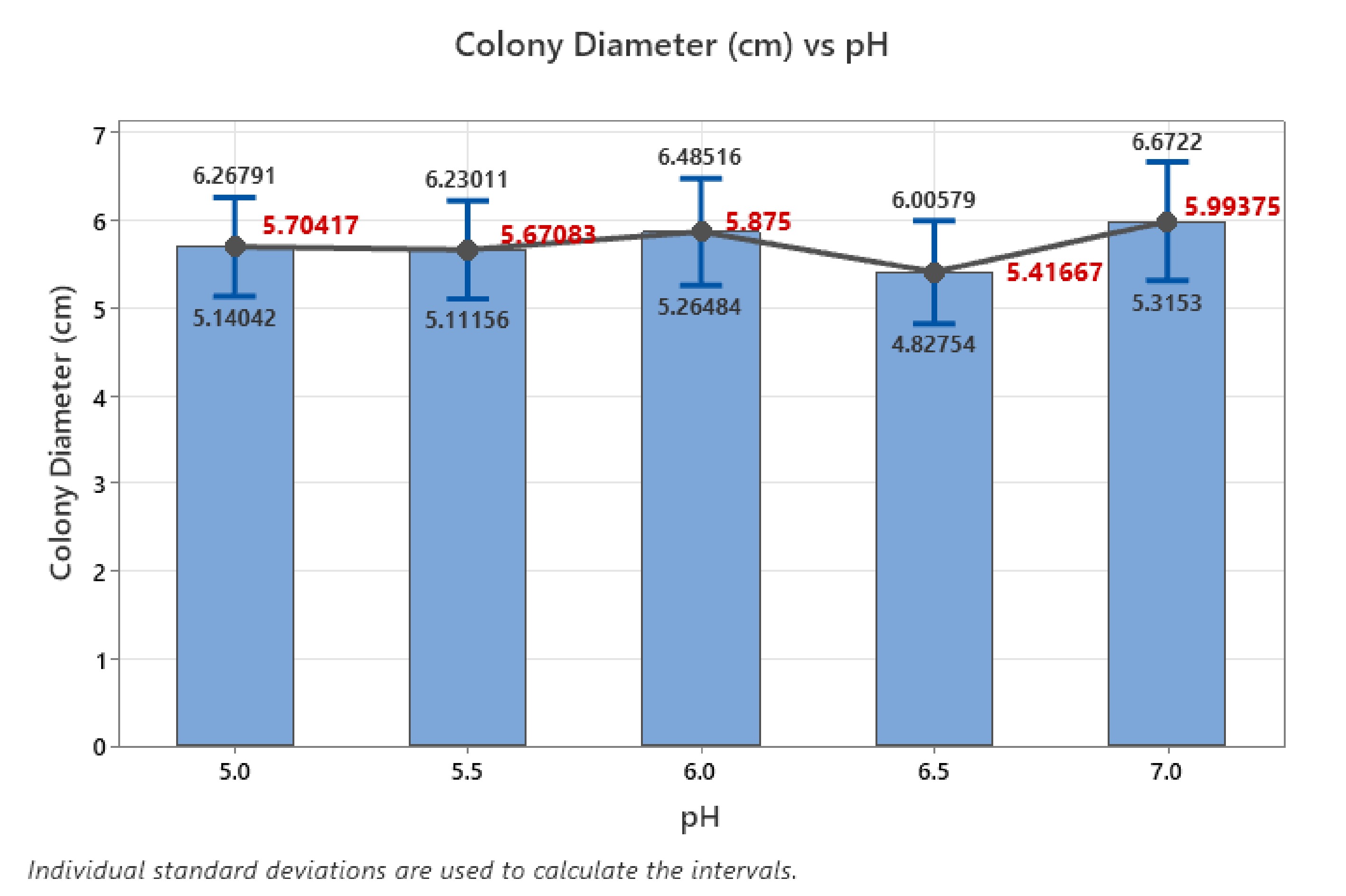

The one-way ANOVA analysis was conducted to assess the impact of varying pH levels (5.0, 5.5, 6.0, 6.5, and 7.0) on colony diameter to determine whether there were significant differences between the means across these conditions. The null hypothesis, which stated that all means were equal, was tested against the alternative hypothesis, which suggested that at least one mean was different. The results yielded an F-value of 0.54 and a p-value of 0.707, which is much higher than the significance level of α = 0.05. Since the p-value exceeds the threshold, the null hypothesis could not be rejected, indicating that the differences in colony diameter across the different pH levels were not statistically significant. The descriptive statistics further supported this conclusion. The mean colony diameter values ranged from 5.417 cm at pH 6.5 to 5.994 cm at pH 7.0, with only minor fluctuations between the means. Notably, the confidence intervals (CI) for all pH levels overlapped considerably, suggesting that any observed differences in colony diameter were likely due to random variation rather than the effect of pH (Fig. 6). For instance, at pH 5.0, the 95% CI ranged from 5.115–6.293 cm, while at pH 7.0, the interval was 5.404–6.583 cm, reflecting a high degree of overlap and no meaningful distinction between these groups.

The error bar plot visually reinforced these findings, as the error bars representing the confidence intervals overlapped significantly across all pH levels. Although there was a slight increase in colony diameter at pH 6.0 and 7.0, followed by a marginal dip at pH 6.5, these variations were not substantial enough to imply any significant trend. The pooled standard deviation of 2.07221 and the low R2 value of 0.91% confirmed that the model explained very little of the variability in colony diameter, with both the adjusted and predicted R2 values remaining at 0.00%. Thus, the analysis demonstrates that the pH variations between 5.0 and 7.0 had no significant effect on colony growth. The observed differences in mean colony diameter were minimal and within the range of random error, suggesting that the fungal colony exhibited relatively stable growth across this pH range.

Analysis of factor-interactions

-

Interaction plots in ANOVA are essential for understanding how two factors jointly influence the outcome. They reveal whether the effect of one factor changes based on the level of another, helping identify synergistic or antagonistic effects. These plots simplify the interpretation of complex relationships, ensuring accurate conclusions. In optimizing fungal growth against Parthenium weed, interaction plots highlight optimal combinations of temperature, pH, and time, guiding better experimental decisions.

Time-temperature interaction

-

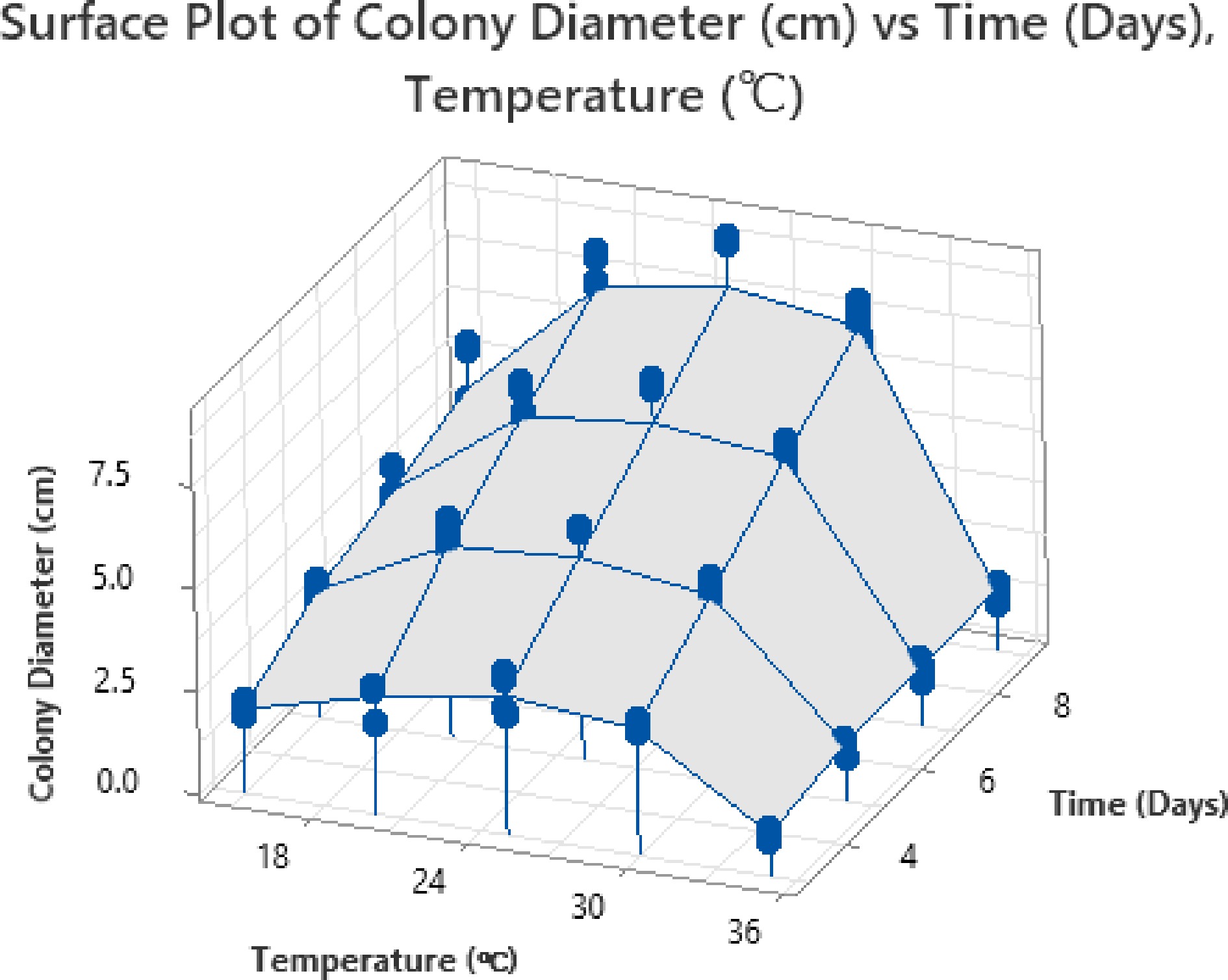

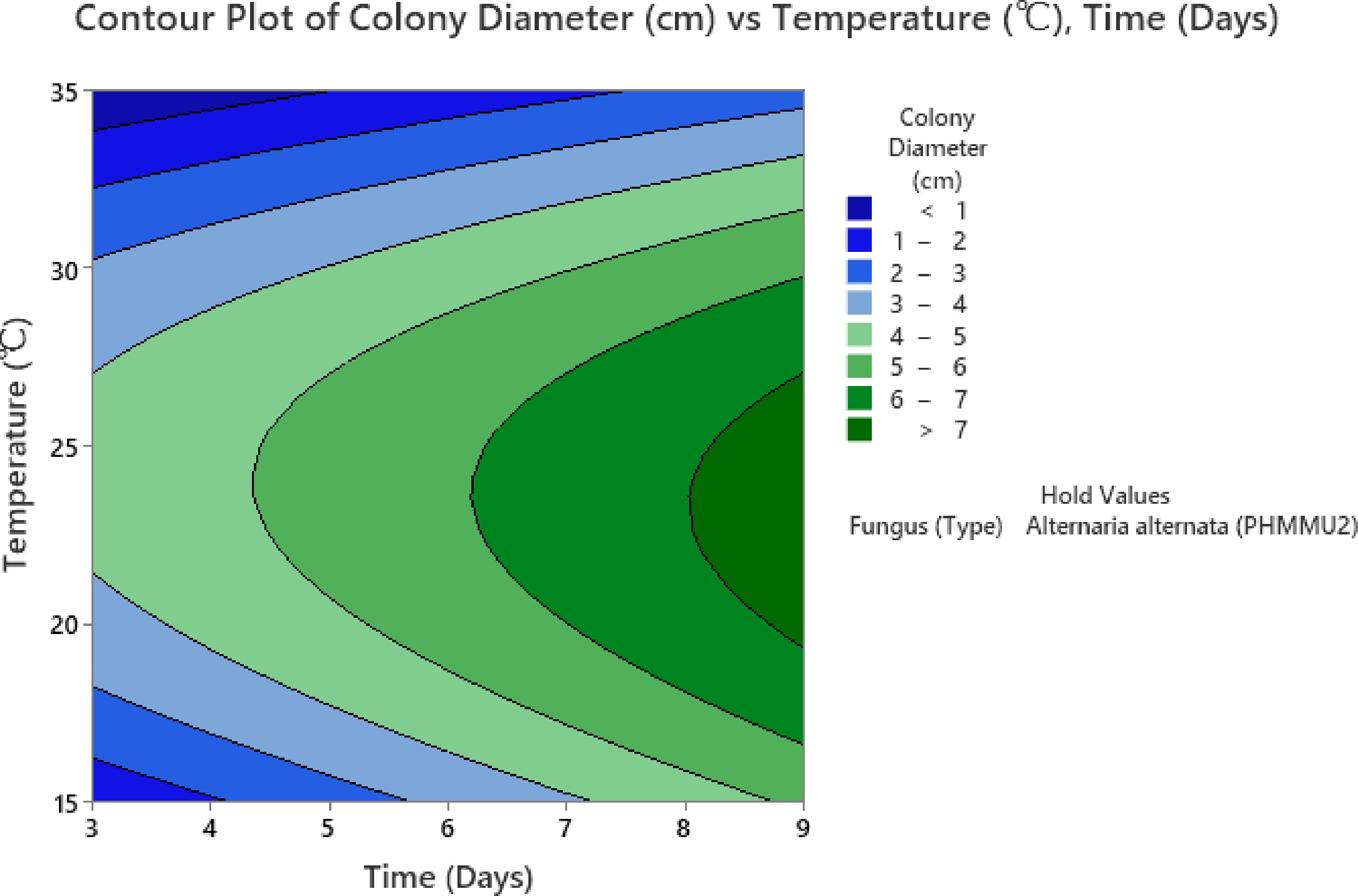

The surface and contour plots provide detailed insights into the combined effects of time and temperature on colony diameter growth (Fig. 7). From the surface plot, it is evident that the colony diameter shows a significant increase as the temperature rises from 18 to approximately 28 °C, with the maximum diameter observed after 6–7 d of incubation. The highest colony diameter, around 7.5 cm, is recorded at an optimal temperature of 28 °C and 6 d, suggesting that these conditions are ideal for the enhanced growth of the mycoherbicidal fungi targeting Parthenium weed. However, beyond this temperature range, particularly above 30 °C and after 7 d, a gradual decline in colony growth is observed, likely due to the adverse effects of excessive heat or nutrient depletion.

The contour plot further validates these findings by highlighting the regions of optimal growth (Fig. 8). The darker green regions, representing colony diameters greater than 7 cm, appear prominently around 25–30 °C and 6–7 d. Conversely, temperatures below 20 °C or above 32 °C, along with shorter incubation periods (3–4 d), lead to reduced colony growth, as indicated by the blue and light green zones where the colony diameter remains below 3 cm. This decline at higher temperatures suggests that the fungal strain may experience thermal stress, limiting its metabolic activity and growth.

These findings emphasize the need to maintain optimal temperature and incubation periods to maximize fungal growth and effectiveness in controlling Parthenium weed. Such optimized growth conditions can significantly enhance the biocontrol potential of the fungi, making it a more reliable and sustainable solution.

Time-pH interaction

-

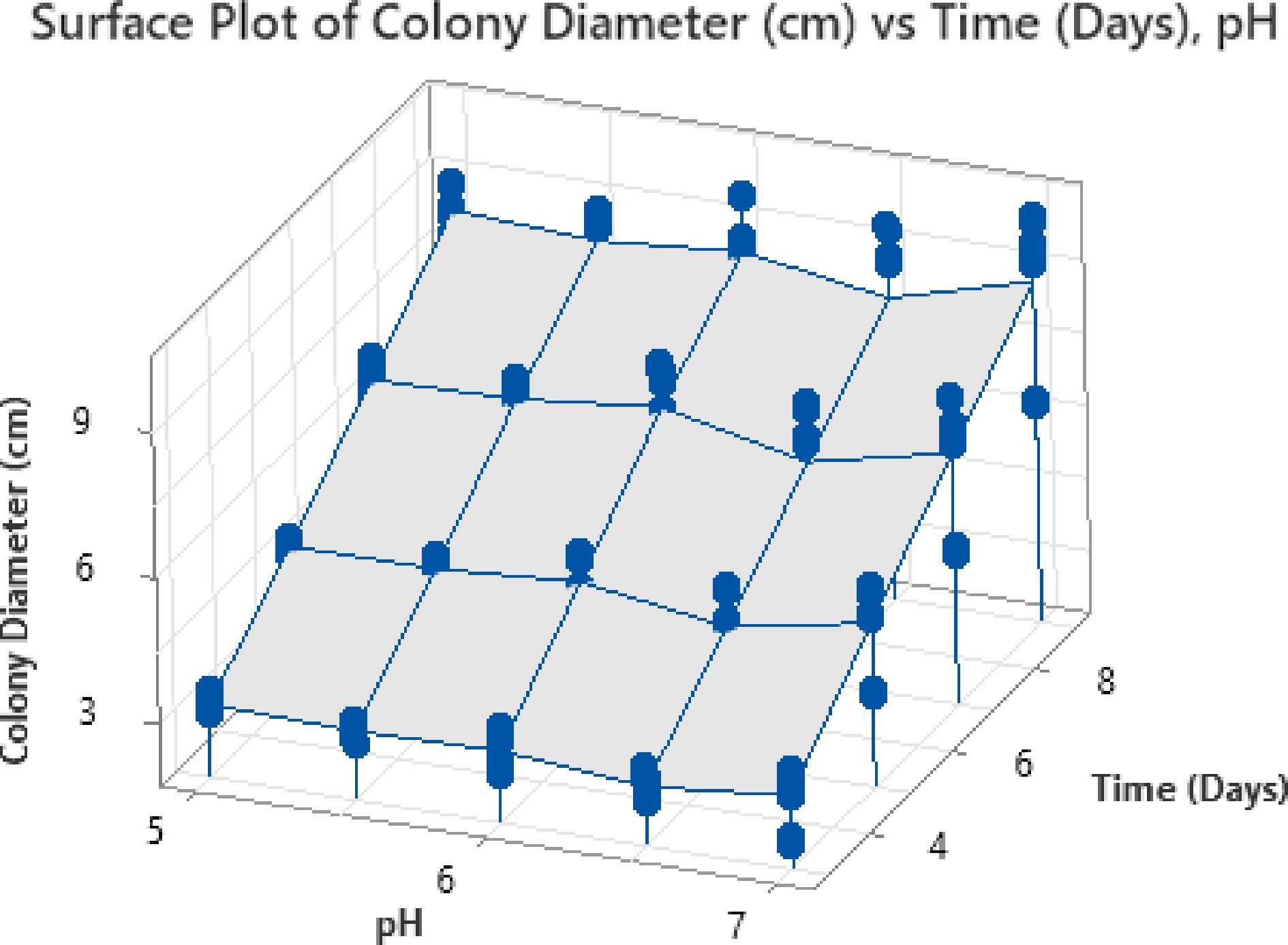

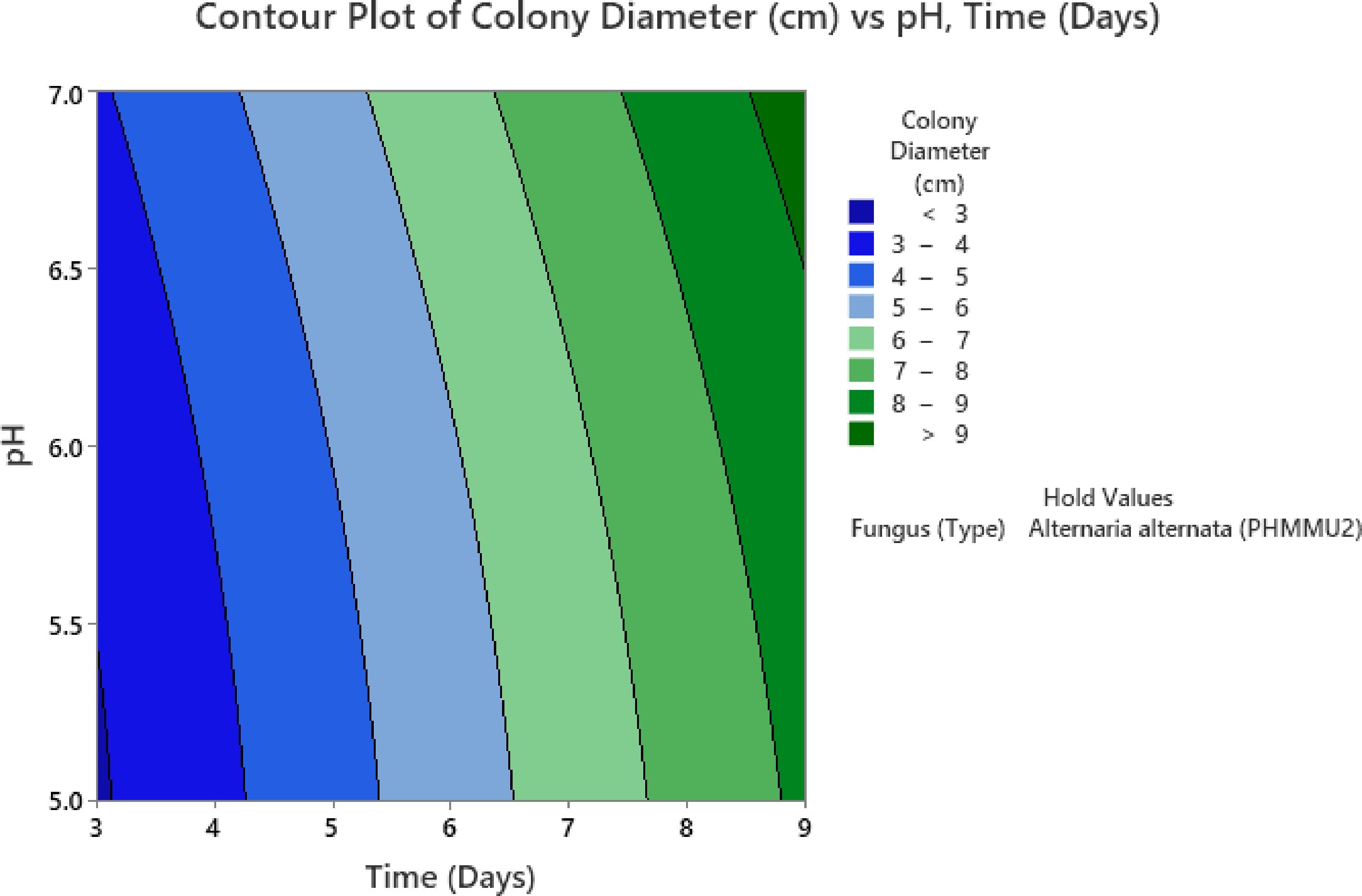

The surface plot depicting the interaction between pH and time in relation to colony diameter shows a gradual increase in growth as pH levels and incubation time advance (Fig. 9). Initially, at lower pH values 5.0 to 5.5, the colony diameter remains relatively small, even after 6–8 d. However, as the pH approaches neutral conditions (around 6.5 to 7.0), a significant increase in colony diameter is observed, suggesting that higher pH values closer to neutral are optimal for the growth of fungal isolates. The contour plot further corroborates this trend by displaying distinct bands of increasing colony diameter as both pH, and incubation time increase. Maximum colony growth exceeding 9 cm is recorded at pH values between 6.5 and 7.0 after 8–9 d of incubation, indicating that near-neutral pH promotes favourable fungal growth conditions.

Additionally, the contour plot highlights that at lower pH levels (5.0 to 5.5), the colony diameter remains restricted to below 3 cm, even after prolonged incubation periods (Fig. 10). The shift from blue to green zones in the contour plot visually illustrates the progressive enhancement in colony diameter with increasing pH and time.

This pattern suggests that Alternaria alternata thrives in environments where pH is maintained closer to neutrality, with a clear preference for a pH range between 6.5 and 7.0. These findings emphasize the importance of optimizing pH conditions to maximize fungal growth, especially in applications where enhanced biomass production is required for effective biocontrol of Parthenium weed.

-

The discussion highlights the critical role of optimizing growth parameters to enhance the colony development of fungal isolates, making them more effective mycoherbicidal agents against Parthenium hysterophorus. ANOVA results confirmed that temperature, pH, and incubation time significantly influenced colony growth, with p-values less than 0.05 for all factors. It was noted that the interaction between temperature and time was pivotal, with maximum colony growth of 7.8 cm recorded at 28 °C after 7 d of incubation. Similarly, time-pH interaction revealed 9.1 cm growth at pH 6.5 after 8 d. These findings are supported by surface and contour plots, which emphasize the optimal zones around 26–30 °C and pH 6.0–7.0. Biological control using fungal isolates, such as Alternaria alternata, offers an eco-friendly approach to managing invasive weeds like Parthenium hysterophorus, which poses significant threats to agriculture, biodiversity, and human health[35]. In this study, four fungal isolates, A. alternata (PHMMU2) and three strains of A. macrospora (PHMMU1, PHMMU3, and PHMMU4) were identified as potential biocontrol agents. Their desirable traits, such as high sporulation capacity, a narrow host range, and a fast growth rate, make them suitable candidates for large-scale production. However, optimizing growth conditions is essential for improving fungal biomass and conidial yield, as factors like nutrient availability, temperature, pH, and moisture content significantly influence fungal growth and sporulation[36].

While this study emphasizes the importance of optimizing sporulation for effective mycoherbicidal application, it is important to clarify that sporulation was not directly quantified under the tested conditions. Instead, colony diameter was used as a proxy indicator of fungal growth and biomass. Although mycelial expansion is often positively correlated with sporulation in many Alternaria species, this relationship is not always linear or consistent across all strains. Previous studies have reported a general association between vigorous colony development and higher conidial yield in Alternaria alternata and A. macrospora under favourable conditions[37,38].

To ensure clarity and consistency, the reported optimal conditions are based on interaction effects rather than single-factor analyses. While ANOVA identified 25 °C and pH 7.0 as optimal individually, time-temperature and time-pH interactions revealed greater fungal growth at 28 °C after 6–7 d (~7.5 cm) and at pH 6.5 after 8 d (9.1 cm). These interactions better reflect real-world conditions, where multiple factors act simultaneously. Therefore, 28 °C and pH 7.0 are reported as the final optima, providing a more practical and application-oriented framework for maximizing fungal biomass in mycoherbicidal formulations for sustainable Parthenium management.

This study provides essential in vitro insights into optimizing fungal growth; however, field validation remains a key limitation. Real-world conditions, such as environmental fluctuations, microbial competition, and moisture variability, can significantly affect fungal efficacy. To bridge this gap, future work will involve greenhouse trials and field-based experiments to evaluate the performance of these isolates under natural conditions. Additionally, efforts will focus on developing suitable formulations and delivery methods to enhance fungal survival and dispersal in the field. These steps are critical for translating laboratory findings into practical, scalable biocontrol strategies for sustainable Parthenium management.

The observed optimal temperature (28 °C) and pH (6.5–7.0) likely enhance Alternaria growth by supporting key metabolic and enzymatic functions. At 28 °C, cell wall-degrading enzymes, including cellulase, pectinase, and polygalacturonase, are maximally produced, facilitating nutrient assimilation and host colonization, thus aiding pathogenicity[28]. Similarly, near-neutral pH stabilizes enzyme structure, promotes efficient ion transport, and supports secondary metabolite production, including phytotoxins and conidia. These conditions create a favourable environment for both vegetative growth and potential virulence[39]. Although this study focused on colony expansion, future molecular-level investigations could further clarify the biological mechanisms linking growth conditions to mycoherbicidal efficacy in Alternaria species.

Although optimization of growth parameters for Alternaria species has been previously studied[29,40−44], the current work offers novel insights by specifically evaluating indigenous Alternaria alternata and A. macrospora strains isolated from naturally infected Parthenium hysterophorus in the agro-ecological context of Northern India (Haryana, Mullana). Unlike earlier studies that have often generalized growth profiles or used non-target weeds, this study focuses on strain-specific responses under varying abiotic conditions (temperature, pH, incubation time) with robust statistical validation, including interaction modelling. The identification of PHMMU2 and PHMMU3 as high-performing candidates under defined optimal conditions, supported by regression and contour analysis, provides a refined, data-driven foundation for future formulation and field application efforts. These findings bridge existing gaps between isolate identification and real-world scalability, offering an improved framework for developing effective, climate-adapted mycoherbicidal solutions against Parthenium in Indian cropping systems.

The interaction plots (Figs 7−10) were based on Alternaria alternata (PHMMU2), with 'fungal type' held constant. Although not statistically significant in ANOVA (p = 0.204) and regression (p = 0.065), potential strain-specific responses cannot be entirely ruled out. However, narrow confidence intervals, overlapping error bars, and consistent growth trends across all isolates suggest that the observed interaction patterns for PHMMU2 are broadly applicable to the A. macrospora strains as well. Thus, the optimal conditions derived from interaction plots are considered generalizable within this study. Future research may validate these findings through strain-specific interaction modelling.

While the multiple regression model demonstrated a high degree of fit (R2 = 93.72%), the significant lack-of-fit (p = 0.001) suggests the possible influence of unmodeled factors or minor nonlinear interactions not captured in the current model structure. This highlights the complexity of biological systems and indicates that future models could benefit from incorporating additional variables or nonlinear terms.

Although the one-way ANOVA indicated that differences among fungal isolates were not statistically significant, Alternaria macrospora (PHMMU3) exhibited the numerically highest mean colony diameter (4.445 cm) in the single-factor analysis. This strain consistently demonstrated robust growth across varying temperatures and incubation periods, suggesting potential for higher metabolic activity or adaptability under the tested conditions. While these observations warrant further investigation, they may indicate strain-specific traits that could enhance biomass production or conidial yield under optimized conditions. Future studies focused on physiological profiling and secondary metabolite analysis could help elucidate whether PHMMU3 possesses unique biocontrol advantages over other isolates.

The findings align with previous studies suggesting that mesophilic fungi exhibit optimal growth between 20 and 30 °C, with reduced activity at higher temperatures due to thermal stress[40]. A sharp decline in colony diameter at 35 °C was observed, attributed to the denaturation of cellular proteins and disruption of membrane integrity[41]. Similar patterns were observed in a previous study, indicating that moderate temperatures support optimal fungal activity. In terms of pH, maximum growth occurred at pH 7, which supports enzymatic activity and nutrient absorption[42]. Differences in growth patterns among fungal isolates were evident, with A. alternata (PHMMU2) displaying superior colony development compared to A. macrospora strains, suggesting species-specific variations in pH tolerance[43]. Colony diameter measurements over different incubation periods revealed a steady increase in fungal growth, with maximum expansion observed on the ninth day. Similarly, this finding concurs with previous research which, demonstrated that extended incubation allows for optimal fungal proliferation and mycelial development[30]. Moreover, a study also emphasized that sufficient incubation time facilitates the establishment of extensive hyphal networks, promoting efficient resource utilization[45]. These results confirm that temperature, pH, and incubation time are critical factors in determining fungal growth, providing a foundation for enhancing the effectiveness of fungal isolates as biocontrol agents for Parthenium management.

-

The study successfully optimized key growth parameters to enhance the colony growth of fungal isolates for controlling Parthenium hysterophorus. The results demonstrated that temperature, pH, and incubation time significantly influenced fungal proliferation, with the highest colony diameter observed at 28 °C, pH 7, and after 6–9 d of incubation. Interaction analysis provided valuable insights, confirming that deviations from these optimal conditions led to reduced colony growth. These findings highlight the importance of maintaining ideal growth conditions to maximize the efficacy of fungal isolates as a biocontrol agent. By establishing optimal growth conditions, this study contributes to enhancing the efficiency of Parthenium management, providing a sustainable and eco-friendly alternative to chemical herbicides. The optimized parameters not only improve fungal biomass and conidial yield but also pave the way for large-scale deployment of fungal biocontrol agents in integrated weed management programs. Furthermore, the study lays a solid foundation for advancing biological control methods that reduce the environmental impact of conventional weed control strategies.

Future research should focus on conducting field trials to validate the laboratory findings and developing robust mycoherbicidal formulations to ensure consistent efficacy under diverse environmental conditions. Additionally, exploring the scalability of mass production processes and evaluating the long-term effectiveness of these fungal isolates in real-world settings will further strengthen their role in sustainable agriculture.

The authors express their gratitude to Dr. Adesh Saini, Head of the Department of Bio-Sciences and Technology at Maharishi Markandeshwar (Deemed to be University), Mullana, Ambala, Haryana, India, for providing access to the necessary resources and laboratory facilities that enabled the successful completion of this research work.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study concept and design: Singh R; data and samples collection: Sahu K; data interpretation: Sehgal R; analysis and interpretation of results: Singh BJ; draft manuscript preparation: Sharma AK. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Experimental data.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Sahu K, Singh BJ, Sehgal R, Singh R, Sharma AK. 2025. Harnessing optimal growth conditions for improved biocontrol of parthenium weed using mycoherbicidal fungi. Studies in Fungi 10: e025 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0026

Harnessing optimal growth conditions for improved biocontrol of parthenium weed using mycoherbicidal fungi

- Received: 08 April 2025

- Revised: 04 September 2025

- Accepted: 09 September 2025

- Published online: 05 November 2025

Abstract: Parthenium hysterophorus is an invasive weed causing significant ecological, agricultural, and health-related issues worldwide. This study aimed to optimize various growth parameters to enhance the colony development and sporulation of fungal isolates for effective management of Parthenium hysterophorus. During field surveys, four fungal isolates were isolated from infected Parthenium leaves, and the fungal isolates were identified as Alternaria alternata and three different strains of Alternaria macrospora, based on morphological, cultural, and molecular analyses. To maximize the growth and efficacy of these fungal isolates, experiments were conducted to determine the optimal conditions for temperature, pH, and incubation time. The results revealed that the ideal conditions for maximizing colony diameter and sporulation were 28 °C, pH 7, and 6–9 d of incubation. Surface and contour plots highlighted the interaction effects of these factors, confirming that deviations from these conditions resulted in reduced colony growth. ANOVA results indicated that all main factors and their interactions had a significant impact on colony development, underscoring the importance of maintaining precise control over these variables. Optimizing these growth parameters is essential for enhancing the efficacy of fungal isolates as biocontrol agents. The findings provide a foundation for scaling up fungal biomass production and field application, offering an environmentally sustainable alternative to chemical herbicides. This work advances the development of effective biocontrol strategies to manage Parthenium weed while promoting safer and more sustainable agricultural practices, thereby reducing dependence on harmful chemical herbicides.