-

Agriculture is a cornerstone of human society, serving not only as the primary source of sustenance but also as a key driver of global food security, economic development, and community well-being. In the face of rapid population growth and the increasing demand for food, the importance of agriculture continues to grow. However, traditional agricultural practices, significantly shaped by the Green Revolution of the 20th century, have raised concerns about long-term sustainability. While the introduction of high-yielding crop varieties, synthetic chemicals, fertilizers, and improved irrigation systems boosted food production dramatically, these advances have also led to environmental degradation, including soil and water pollution, and the emergence of pesticide-resistant pests and pathogens[1].

The world population will be around 10 billion people by 2025, which means that food production capacities must be enhanced by 60%[2,3]. This forecast puts a lot of expectation on the agricultural sector to feed the increasing number of people, given the constraints of soil and land degradation, climate change, limited arable land and water, and natural resources depletion[4]. Pesticide utilization also intensifies these challenges by depleting the basic vital input resources for agriculture, besides underlining its sustainability complications[2,5].

Because of this, there is an increasing need for agriculture to embrace sustainable and environmentally friendly methods that not only enhance the quality of produce but also lessen its impact on the environment[6]. In this regard, microbial symbiosis needs to be considered. These microorganisms are involved in determining soil fertility, nutrient cycling, enhancing crop performances, and acting as biological control agents against crop diseases and environmental stresses[7]. The study of microbial synergies in agricultural fields has emerged as a promising path toward addressing the challenges of global food insecurity[8]. Over millions of years, these microbes have developed a mutual interaction with plants, where the plants cannot survive without these microbes, and vice versa. They are crucial in the maintenance of life and productivity of the terrestrial ecosystem[9].

Due to the specific positive impacts of these microbes on farming, it is possible to build constructive, mutually beneficial symbiosis between crops and these microorganisms, which allows researchers and farmers to create sustainable and highly productive agricultural systems[10]. Microbial partnerships enhance soil health and improve plant growth and adaptability to stressors such as climate change, drought, and pests[10]. Such natural allies can reduce the requirement for synthetic chemical inputs, lowering the production cost and enhancing the profit margin of the farmers in the long run, as well as at the same time promoting sustainable environmental practices[11].

Furthermore, microbial exploration is in accord with the principles of agroecology or regenerative agriculture, the strategies that look for ways to enhance the performance of the systems by mimicking the help of microorganisms. Exploiting the knowledge of such microbial interactions presents a way forward to the growing and immediate crises of food insecurity, environmental degradation, climate change impacts, and income diversification for farmers across the globe[12].

This review delves into the complex and fascinating world of microbial partnerships in agriculture, exploring the latest research, innovative techniques, and practical applications that could revolutionize the agricultural sector to a sustainable and resilient future for global food production.

-

The soil microbiome is a complex and diverse ecosystem, hosting a vast array of microorganisms. This intricate network encompasses bacteria, fungi, archaea, protozoa, and viruses, each contributing to the complicated web of interactions that sustain soil fertility and productivity. To put the scale of this microscopic world into perspective, a single handful of soil contains over a billion microbial cells[13]. More specifically, Chandra et al. reported that in a typical agricultural soil sample of just 1 cm3, one can find approximately: 90,000,000 bacterial cells, 4,000,000 actinomycetes, 200,000 fungi, 30,000 algae, 5,000 protozoa, and 30 nematodes[14]. In this context, earthworms are present in numbers less than one per cubic centimeter. The microbial activity in soil is not constant. It fluctuates both temporally and spatially. Perhaps most surprisingly, despite the enormous numbers of microorganisms present, only a small fraction is actively engaged at any given time. Blagodatskaya & Kuzyakov estimate that approximately 95% of soil microbes remain in a dormant state[15].

The most prevalent and varied microbial group is bacteria[16]. Despite the vast microbial diversity present in soil ecosystems, with an estimated 30,000 bacterial species inhabiting the soil, our current understanding and characterization encompass only a small fraction, approximately 3,000 of these species (Table 1)[17]. They exhibit an immense range of metabolic capabilities, enabling them to participate in nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, and the formation of symbiotic associations with plants. The abundance of bacterial phylotypes in soil typically varies between 102 and 106 per gram[18]. It is similar to the diversity on Earth. Furthermore, they have found a decrease in soil bacteria carrying capacity with increasing soil depth, which is influenced by factors like organic carbon distribution and plant root distribution.

Table 1. Examples for major soil microbial groups.

Major soil microbe group Examples Ref. Bacteria Common phyla: Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria [19] Common genus: Agrobacterium, Alcaligenes, Arthrobacter, Bacillus, Flavobacterium, Micromonospora, Nocardia, Pseudomonas, and Streptomyces [20,21] Fungi Common phyla: Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Glomeromycota, and Zygomycota [22] Common genus: Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Neurospora, Penicillium, Rhizopus, and Saccharomyces [17] Archaea Common superphyla: Euryarchaeota, TACK, DPANN, and Asgard [23] Common genus: Halovivax, Methanobrevibacter, Methanococcus, Pyrobaculum, Staphylothermus, Thermococcus, and Thermofilum [24,25] Protozoa Common species: Balantidium coli, Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia duodenalis, Plasmodium falciparum, Toxoplasma gondii, Trichomonas vaginalis, and Trypanosoma brucei gambiense [25] Fungi are another important component of the soil microbiome, forming a vast and intricate network of mycelium that extends throughout the soil matrix. They possess remarkable adaptability to a variety of ecological conditions owing to their high plasticity and capacity and contribute to the decaying complex organic matter, biogeochemical cycling of elements, and the formation of beneficial relationships with plant parts, known as mycorrhizal associations[26]. While it is estimated that an astonishing 1,500,000 fungal species thrive in the soil ecosystem, our current knowledge and formal description have been limited to merely 69,000 of these species, representing only a small fraction of the immense fungal diversity present in the soil (Table 1)[17]. Prominent fungal phyla are particularly important for the formation of arbuscular mycorrhizal associations with the majority of terrestrial plants. As summarized, one gram of soil contains 200 m of fungal hyphae[27].

Moreover, the soil microbiome also harbors a diverse community of archaea, which are found in agricultural soils and also in extreme environments like hot springs, hypersaline marshes, and acidic soils[28]. They are single-celled organisms, particularly abundant in nutrient-poor environments also. However, their abundance and prominence are much less than other soil microbial organisms[29]. Archaea form intricate interactions with other organisms in the ecosystem. These interactions can involve nutrient exchange, metabolic cooperation, or competitive relationships for resources and space[30]. Examples of this group are given in Table 1.

Soil protozoa are highly diverse, encompassing various groups such as ciliates, flagellates, naked and testate amoebae, and parasitic Sporozoa (Table 1)[31]. Mainly, this group of micro-organisms works as predators of bacteria and fungi, serving as natural controllers of microbial community and nutrient cycling within the soil ecosystem[32]. Protozoa are part of the soil food web, serving as prey for higher-level consumers like nematodes, microarthropods, and other soil fauna[33].

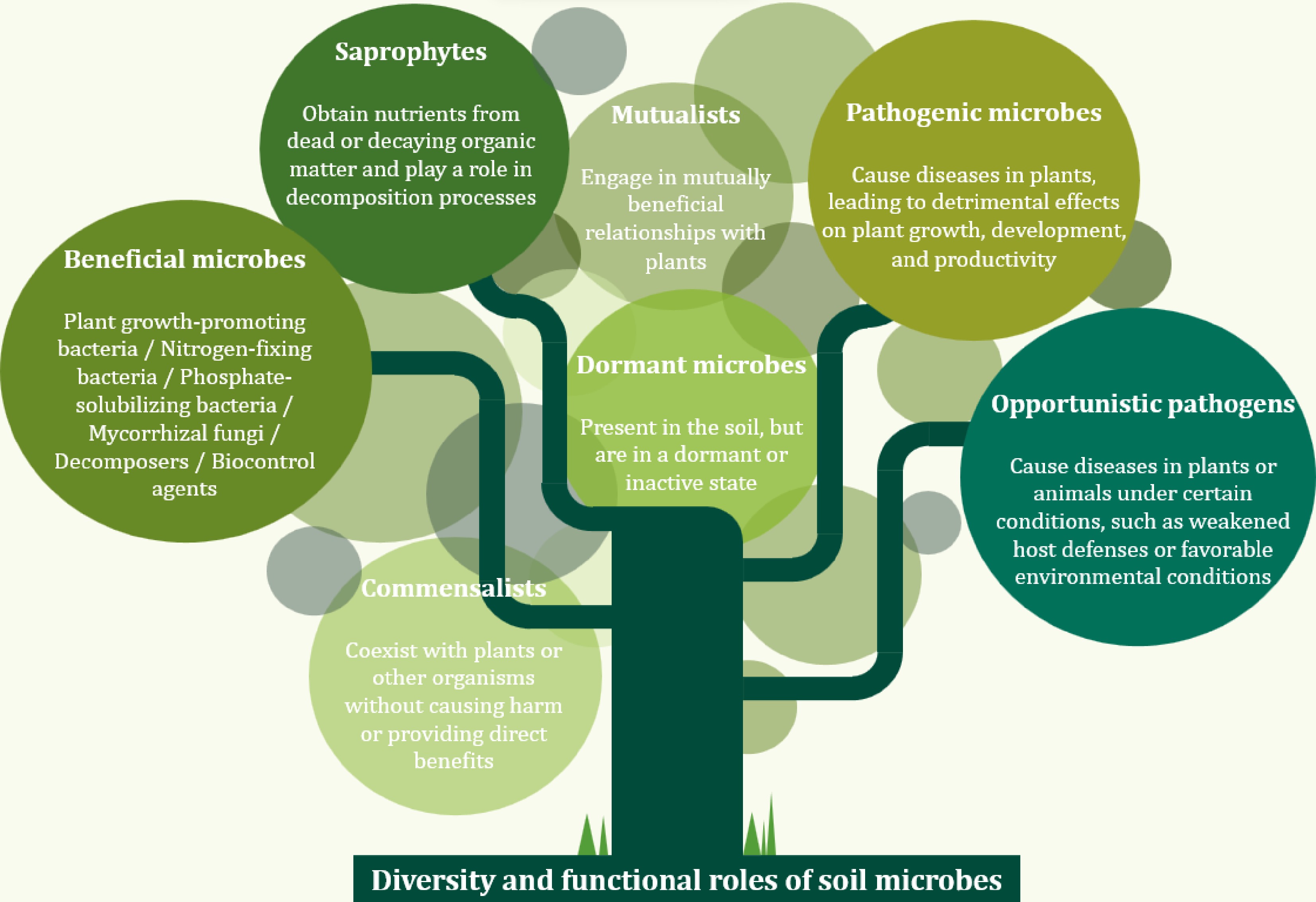

Not all microbes present in the soil are beneficial. These microorganisms can be broadly divided into several categories considering their main activities and their impact on plants and the soil ecosystem (Fig. 1). Some microbes can exhibit different roles or activities depending on the environmental conditions or their interactions with other microbes and plants.

-

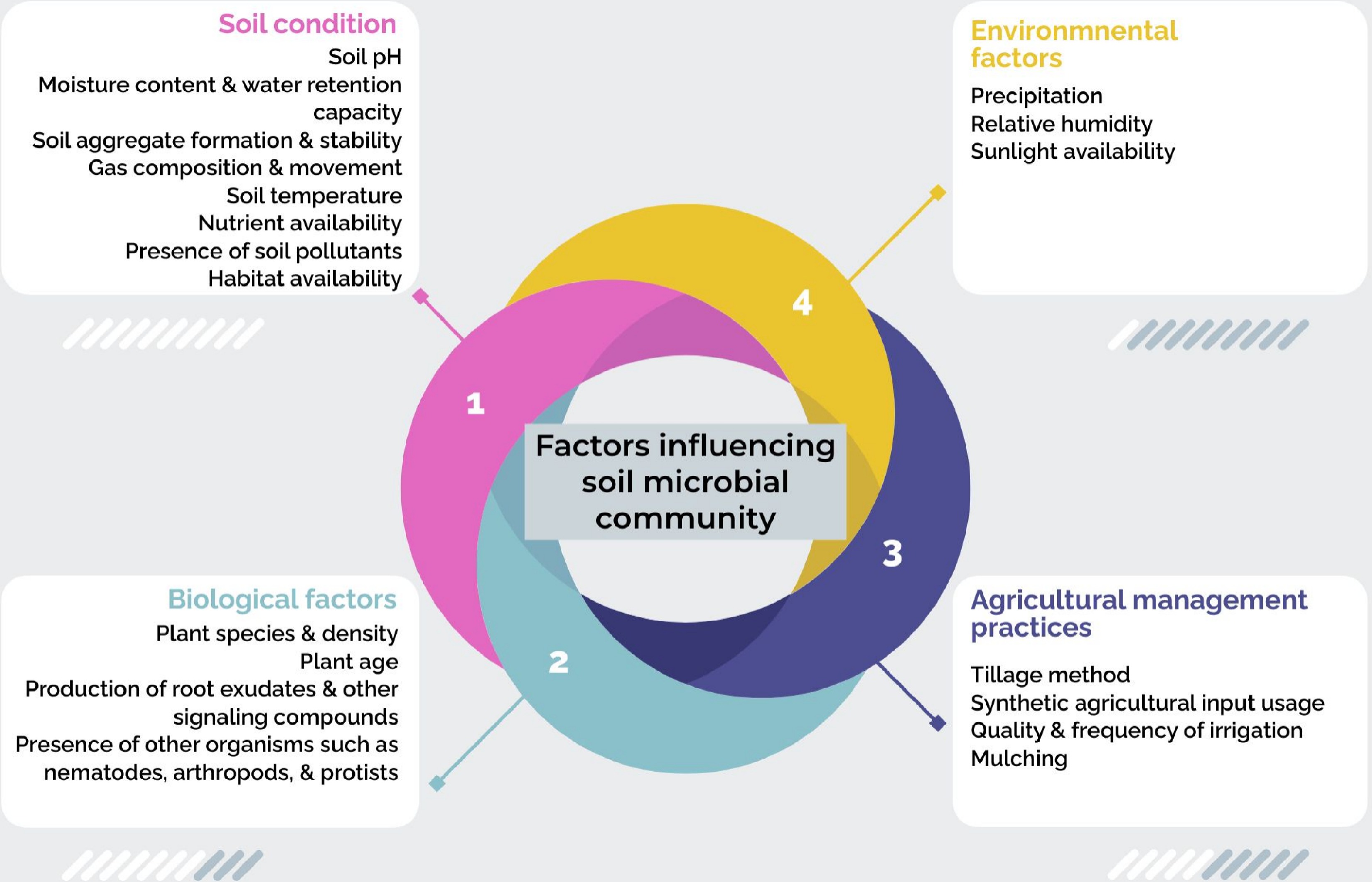

The soil microbiome is a highly dynamic and responsive system, with its composition and diversity shaped by a multitude of parameters, together with soil physicochemical properties, the types of plant species present within a given environment, as well as the specific agricultural practices employed, which contribute further to the intricate tapestry of microbial life within the soil (Fig. 2).

Physicochemical factors in soil

-

Soil microbes are known to be influenced by a broad range of environmental factors. Acidobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia have been found to grow well in acidic soils, while Actinobacteria and Firmicutes are found to grow well in neutral to alkaline soils[34]. Soil moisture also influences microbial abundance; bacteria are more common in drier soils, whereas fungi thrive in wetter conditions. As reported in previous literature, organotrophic bacteria, Azotobacter, actinomycetes, and fungi show the highest abundance when soil moisture levels correspond to 20%, 20%–40%, 40%, and 60% of the soil's maximum water capacity, respectively[35]. Furthermore, aeration, water retention, and temperature, which are dependent on physical soil properties such as particle size and soil aggregation, influence microbial habitats[22]. The provision of nutrients also affects microbial communities by favoring the groups with certain metabolic requirements. In addition, microbes are also susceptible to toxic heavy metals and contaminants such as microplastics that hinder their growth[36].

Biological factors

-

Different plant species selectively recruit and support specific microbial communities through root exudates, mucilage, and signaling molecules[37]. It also varies with the development processes of plants to adapt to variations in root secretion and nutrient absorption. However, the interactions with other organisms, such as nematodes, arthropods, and protists, can affect the community structure and the manner of interaction between microorganisms, as well as the rest of the soil communities.

Agricultural management practices

-

Tillage, mono-crop cultivation, and misuse of synthetic inputs erode the soil structure and reduce microbial richness and resistance, leaving only a few species resistant to the practices[5]. It causes acidification, an imbalance of nutrients, loss of organic materials, and water pollution from chemicals, affecting useful microorganisms in the soil. Nutrient pollution that triggers eutrophication can cause algal blooms, and a decrease in oxygen levels while affecting the species and microorganisms that live in the water[38]. Heavy machinery compacts soil around the root side, decreasing water and air availability for microbes and their activity[39]. The volume and quality of irrigation water, the timing, and frequency of watering can influence soil moisture conditions and nutrient availability, impacting microbial community composition[40]. Agricultural expansion often results in habitat conversion and fragmentation that can alter the ecosystems' structure and function, consequently reducing the above- and below-ground biotic diversity and microbes.

Apart from these three main determinants, other environmental conditions such as rain, humidity, and light for the growth of natural microorganisms are crucial[26]. All of them interconnect in intricate manners to control the complex ecology of the soil microbiome. These dynamics are vital in formulating strategies that ensure the revelation of commensal microbes that foster sustainable agricultural production.

-

Nitrogen is a part of chlorophyll, enzymes, proteins, as well as nucleic acids in plant cells[41]. The nitrogen cycle is also accomplished by the microbes, where nitrogen is transmuted into other forms, such as nitrates and ammonium, that are easily absorbed by the plants[42]. These microbes promote plant growth and performance[43]. Decreasing synthetic fertilizers, which are used to supply nitrogen to plants, leads to reducing the harm of greenhouse gas emissions, pollutants affecting groundwater, and soil acidification[44].

Nitrogen fixation

-

Soil microbes play a pivotal role in the nitrogen cycle. It involves a series of transformations that convert nitrogen from one form to another, and microorganisms are the primary drivers of these transformations[45]. Certain bacteria, known as diazotrophs, can convert atmospheric nitrogen (N2) into ammonia (NH3), via nitrogen fixation[46]. It is an essential step, as most living organisms cannot directly utilize atmospheric nitrogen. There are two main methods of nitrogen fixation facilitated by microorganisms: symbiotic nitrogen fixation (SNF) and a-symbiotic (free-living) nitrogen fixation (ASNF). SNF involves a mutualistic relationship between certain bacteria and leguminous plant species (family – Fabaceae)[9]. They are recognized as a subset of rhizobacteria that promote plant growth (e.g., Rhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, and Azorhizobium species)[47]. Rhizobia colonize the roots of the host plant and encourage the formation of root nodules. Inside these nodules, the bacteria live in organelle-like structures, which can convert N2 into NH3 using the nitrogenase enzyme complex[48,49]. This symbiosis can supply up to 80% of the nitrogen required by leguminous crops[50]. The NH3 synthesized by the bacteroid is assimilated by the host plant, providing it with a readily available source of nitrogen for plants. In exchange, the plant supplies food for bacteria with carbohydrates and a protected environment within the nodules[51]. ASNF is done by free-living (non-symbiotic) microorganisms that can fix atmospheric nitrogen without forming a direct association with plants. They form associations with decomposing plant residuals, soil aggregates, and termite habitats[52]. These microorganisms are found in soil, water bodies, and plant surfaces. They are represented by bacteria such as Azotobacter, Mycobacterium, Azospirillum, and Bacillus, Archaea including Methanococcales, Methanobacteriales, and Methanomicrobiales, and also Cyanobacteria like Anabaena, Nostoc, Anabaenopsis, and Tolypothrix[53]. Comparison between these two groups is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Key contrasts between symbiotic nitrogen fixation (SNF) and a-symbiotic (free-living) nitrogen fixation (ASNF)[54].

Symbiotic nitrogen fixation A-symbiotic (free-living) nitrogen fixation Represented by only a few specialized bacterial types Represented by a diverse community of different nitrogen-fixing bacteria Need to receive a steady, direct supply of simple carbon compounds like succinate from their host plants Need to rely on variable and complex dissolved organic carbon from soil, which can be unpredictable in availability Benefited from carefully regulated, low-oxygen environments maintained by their host plants Experienced highly variable oxygen levels in the rhizosphere, influenced by soil properties and microbial/root respiration Need to get critical nutrients delivered directly by their host plants Must independently acquire essential nutrients from the soil environment Focus exclusively on nitrogen fixation, with all their fixed nitrogen being transferred to the host plant Able to access nitrogen from multiple sources (soil nitrogen plus their fixation), giving them flexibility Nitrification

-

NH3 in the soil goes through a two-step process known as nitrification. In the initial process, NH3 is converted to nitrite (NO2−) through the actions of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea. In the second step, NO2− is oxidized to nitrate (NO3−) by the action of nitrite-oxidizing bacteria[55]. High levels of nitrification may result in loss of nitrogen in the form of leaching and denitrification, which are some of the main environmental concerns like water pollution and emissions of greenhouse gases. A process called 'biological nitrification inhibition' works by interfering with the metabolic processes of nitrifying bacteria and archaea, thereby slowing down or inhibiting the conversion of NH3 to NO3−[56]. These inhibitors can act through various mechanisms: (1) directly inhibiting the activity of enzymes involved in the nitrification process, such as ammonia monooxygenase (AMO) and hydroxylamine oxidoreductase (HAO), which are key enzymes for the transformation of ammonia and nitrite, respectively[57]; (2) disrupting the cell membranes of nitrifying bacteria and archaea, affecting their permeability and nutrient uptake, ultimately inhibiting their growth and activity[58]; and (3) modifying soil conditions, such as pH or redox potential, creating an unfavorable environment for better function of nitrifying microorganisms.

Denitrification and ammonification

-

Denitrification is the process by which nitrate (NO3−) is converted back to gaseous forms of nitrogen as nitrous oxide (N2O) and N2, by denitrifying bacteria[59]. This process is important in anaerobic (oxygen-deficient) environments and helps complete the nitrogen cycle by turning nitrogen into gas. Facultative anaerobic bacteria like Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Clostridium are the dominant microbes in this step[60]. Ammonification is another important process where organic nitrogen compounds, like proteins and nucleic acids, are broken down by many heterotrophic bacteria and fungi, releasing NH3 as a byproduct[61]. This process is critical for recycling organic nitrogen back into the soil[62].

The efficacy of nitrogen-fixing microbes is often constrained by abiotic stresses, competition with native microbes, and formulation instability. The specificity of symbiotic relationships limits their universal application across cropping systems. Moreover, inconsistent field performance of biological nitrification inhibitors remains a challenge. Future work should focus on developing microbial consortia combining N-fixers and nitrification inhibitors, understanding plant genotype × microbe interactions, and enhancing microbial persistence through advanced delivery systems.

Phosphorus cycle

-

Phosphorus is essential for energy transfer, photosynthesis, and metabolic processes in plants, but most soil phosphorus is in forms that plants cannot absorb[63]. Normally, only 0.1% of total soil phosphorus is in H2PO4– and HPO42– which are plant-available forms[64]. Phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms, including certain bacteria (approximately 1%–50% of the overall microbial biomass) and fungi (approximately 0.1%–0.5% of the overall microbial biomass), convert these insoluble forms into plant-available ones, improving phosphorus availability, and promoting root development and plant growth[65,66]. This microbial activity reduces synthetic chemical usage, mitigates environmental risks like eutrophication, and supports sustainable farming practices by conserving natural resources[67].

Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria (PSB)

-

Several bacterial genera, including Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Enterobacter, Rhizobium, and Burkholderia, have been identified as efficient phosphate solubilizers. Other than that, Rhodococcus, Arthrobacter, Serratia, Chryseobacterium, Xanthomonas, Klebsiella, Agrobacterium, Azotobacter, Erwinia, Kushneria, and Pantoea have also been identified as potential bacteria for this purpose[68]. These bacteria can solubilize phosphorus through various mechanisms: (1) producing organic acids such as gluconic, citric, oxalic, and lactic acids, which can chelate and solubilize insoluble phosphorus compounds; (2) producing enzymes like phosphatases and phytases, which can hydrolyze organic phosphorus compounds and release inorganic phosphates; and (3) producing protons (H+) or CO2, to reduce the pH in the root zone, maximizing the solubility of phosphorus compounds[69].

Phosphate-solubilizing fungi (PSF)

-

Some of the fungi known to solubilize phosphorus are Aspergillus, Penicillium, Acremonium, Hymenella, Fusarium, and Neosartorya[69]. They can also solubilize phosphorus following the same mechanism as in phosphate-solubilizing bacteria.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF)

-

AMFs form symbiotic associations with the roots of approximately 80% of plant species, facilitating the uptake of organic and inorganic phosphorus from the soil[70]. These fungi collaborate with PSBs in the rhizosphere, enhancing nutrient acquisition and improving soil structure by providing carbohydrates to the bacteria and allowing them to colonize the rhizosphere[71]. AMF also influence bacterial community composition, support nitrogen fixation, and reduce nutrient leaching[72]. Most AMF species belong to the sub-phylum Glomeromycotina within Mucoromycota, comprising four orders: Glomerales, Archaeosporales, Paraglomerales, and Diversisporales, which include 25 genera[73,74].

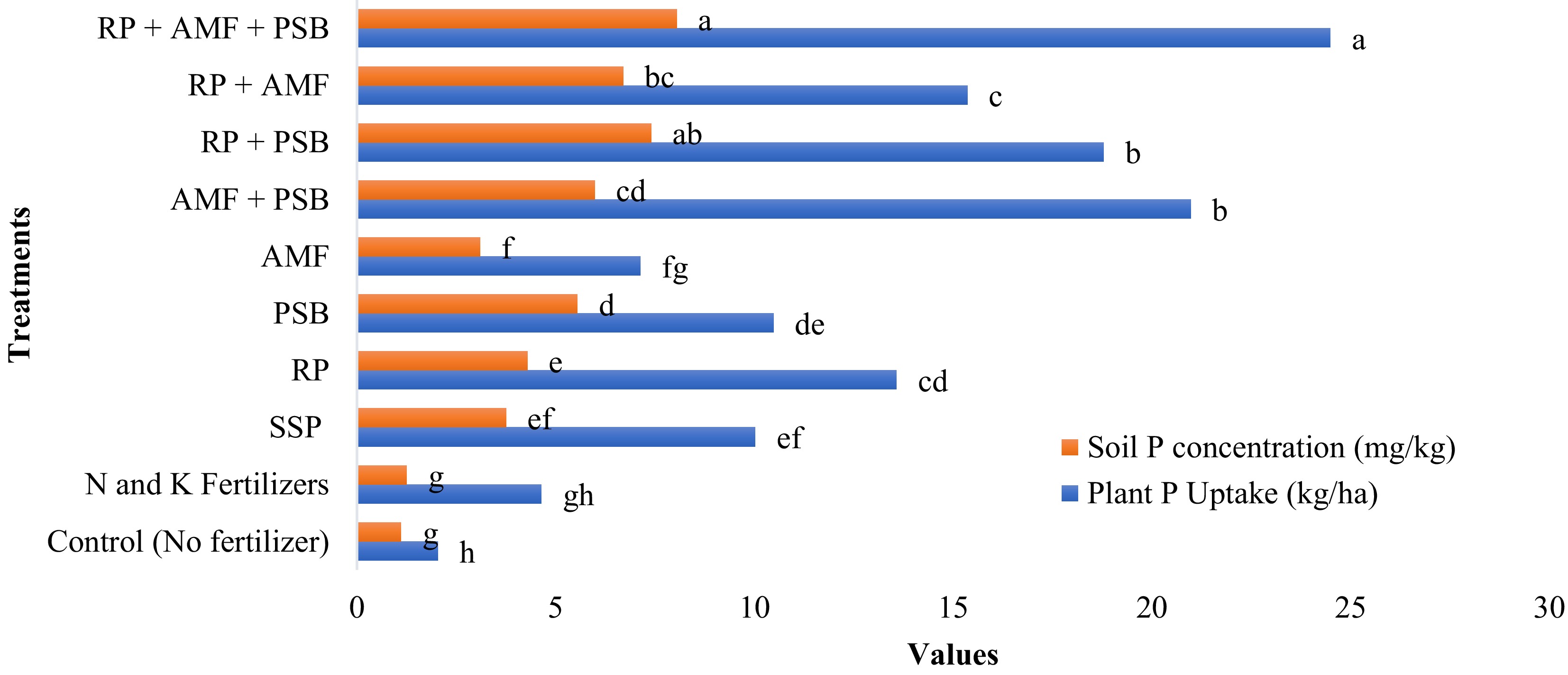

Previous research had confirmed that combined inoculation with AMFs and PSBs can increase the availability of phosphorus from both organic and inorganic sources in soil, making it a promising sustainable approach for phosphorus management in wheat farming (Fig. 3)[70]. Phosphorus availability is hindered by fixation in soils, and many PSB/PSF strains fail to perform consistently under field conditions. The symbiotic establishment of AMF is slow and often varies across host species and soil types. There is also a gap in understanding the interaction dynamics among PSB, PSF, and AMF in mixed inocula. Future efforts should aim to design multi-functional consortia, optimize inoculant formulations, and develop predictive tools for matching microbial strains to soil-crop systems.

Figure 3.

Effect of combined application of rock phosphate (RP), arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria (PSB) on soil phosphorus concentration and plant phosphorus uptake in wheat. Bars represent mean values of soil P concentration (mg/kg) and plant P uptake (kg/ha) under different nutrient management treatments. Treatments with shared letters are not significantly different at p ≤ 0.05. (RP: Rock Phosphate; AMF: Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi; PSB: Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria; SSP: Single Super Phosphate).

-

Certain microorganisms, known as microbial biocontrol agents, can suppress plant pathogens, enhancing plant health and disease management in agriculture. These agents offer an environmentally friendly alternative to synthetic pesticides by providing effective, sustainable pest control solutions, aligning with integrated pest management (IPM) principles and promoting ecological farming (Table 3)[75]. Despite promising lab results, many biocontrol strains fail under real-world conditions due to environmental variability and poor rhizosphere persistence. Regulatory bottlenecks and a lack of farmer adoption further limit their commercial success. Innovations should prioritize microbial strain stabilization, compatibility testing in consortia, and improved delivery methods such as encapsulation or seed coating. Comparative field trials across diverse agroecologies are also urgently needed.

Table 3. Pathogen suppression mechanisms in soil microbes.

Group of microbes Species Example Mechanism Ref. Bacterial biocontrol agents Bacillus species B. subtilis;

B. amyloliquefaciensRelease diverse antimicrobial compounds, including antibiotics, enzymes like cell wall hydrolases, and lipopeptides.

Reduce the growth of plant pathogens, promote systemic resistance in plants, and plant growth.[76,77] Pseudomonas species P. fluorescens;

P. aeruginosaProduce antibiotics like pyocyanin, pyrrolnitrin, and phenazine-1-carboxylic acid, siderophores (iron-chelating compounds), and other anti-microbial metabolites.

Induce systemic resistance and encourage plant growth.[78,79] Streptomyces species Streptomyces roseoflavus Produce a variety of antifungal, antibacterial compounds, and cell wall degrading enzymes like chitinase and β-1,3-glucanase. [80−82] Rhizobium species R. leguminosarum;

R. phaseoli;

R. trifolii; R. lentisProduce a variety of antifungal compounds such as hydrogen cyanide and antibacterial compounds like bacteriocins and trifolitoxin, lytic enzymes, and siderophores substances. [83] Fungal biocontrol agents Trichoderma species T. harzianum; T. viride Inhibit plant pathogens through mycoparasitism (directly parasitizing and feeding on other fungi), antibiosis (production of antimicrobial compounds.

Being an active competitor for resources like nutrients and space.[84] Gliocladium species G. catenulatum;

G. roseumParasitize and inhibit the spread of plant pathogens, particularly fungi and nematodes, through the production of enzymes and other metabolites. [83] Ampelomyces species Ampelomyces quisqualis Parasitize and feed on the mycelium of the powdery mildew pathogens. [85] Yeast Aureobasidium pullulans Create competition for nutrients and space, as well as the releasing enzymes and antimicrobial compounds. [86] Viral biocontrol agents Baculoviruses Used as biocontrol agents against insect pests.

Can cause lethal infections.[87] -

Plant hormones play a crucial role in regulating various aspects of plant growth and development[10]. Certain bacteria, including Azospirillum, Pseudomonas, and Bacillus sp., as well as fungi like Fusarium and Trichoderma, produce phytohormones such as auxins, cytokinins, and gibberellins[10]. For example, auxins like indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), produced by Azospirillum and Pseudomonas sp., stimulate root growth, leading to better nutrient and water uptake, and ultimately boosting crop yields. Cytokinin produced by Bacillus sp. enhances cell division and shoot growth, thereby increasing biomass and yield[88]. Ethylene, another key plant hormone, regulates processes like fruit ripening, senescence, and stress responses[89]. Some bacteria, such as Pseudomonas and Bacillus, produce the enzyme ACC (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid) deaminase, which lowers ethylene levels by breaking down its precursor (ACC). This reduction in ethylene delays fruit ripening, extends shelf life, and improves stress tolerance, enhancing crop quality and yields[90]. In addition to producing phytohormones, certain microbes can degrade or inactivate specific phytohormones, a process known as 'phytohormone degradation'. This ability allows them to regulate hormonal balances and influence plant growth patterns. Moreover, these microbes can produce antioxidants like SOD, POD, APX, CAT, and GR, which help mitigate abiotic stress conditions, further promoting desirable growth and enhancing crop productivity[91,92].

Stress tolerance enhancement

-

With the ongoing effects of climate change, plants face stresses like drought, heat waves, salinity, pests, and extreme weather, making stress tolerance vital for crop productivity and food security[93].

Since drought conditions are becoming more severe worldwide, increasing plant tolerance to drought stress is crucial in managing plant stress. Specifically, glycine betaine compounds are beneficial to plants and soil microbes because they help maintain the water balance of plants, control the aperture of the stoma, and activate stress-responsive genes under drought conditions[94]. For instance, Bacillus and Pseudomonas that are resistant to drought have increased drought stress tolerance in crops like wheat, maize, and cotton[95].

Increased temperatures can lead to more frequent heat waves, which in turn contribute to reduced crop harvests and other socioeconomic challenges. Some microbes synthesize heat-stabilizing antimicrobial compounds to support membrane stability, protein configuration, and disease prevention in plants under heat stress conditions[82]. For instance, inoculating drought-resistant Sorghum bicolor with thermotolerant, chromium-reducing plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) like Providencia rettgeri and Myroides odoratimimus has been shown to enhance plant growth, boost antioxidant enzyme activities, and reduce stress markers, thereby increasing the crop's heat resistance[96].

Moreover, the microorganisms that affect plant hormones, including ethylene and auxins, can also cumulatively contribute to heat stress tolerance by altering root architecture and subsequent root growth to improve water and nutrient uptake. For instance, the use of heat-tolerant ACC deaminase-producing Bacillus cereus has been shown to enhance heat stress tolerance in tomato plants[97].

Plants also need osmotic balance and reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging for survival under the influence of salts in the soil microbes. These can be helpful for coastal and river basins where salinity issues appear due to poor irrigation and rising sea levels[98]. Soaking crops like wheat, rice, and cotton seeds in halotolerant bacteria such as Bacillus and Arthrobacter species has revealed an improvement in salt tolerance[99].

Overall, soil microbes can significantly promote root growth, nutrient acquisition, and stress tolerance, thereby enhancing plant resilience to extreme weather events, minimizing crop losses, and ensuring food security[100]. Many beneficial microbes also form biofilms on plant roots, facilitating colonization and ensuring proximity to the plant, which enables efficient nutrient exchange and hormone modulation[101]. Current microbial solutions for stress tolerance face scalability issues. The variability of stress conditions across regions requires location-specific microbial formulations. Moreover, the long-term ecological impacts of hormone-modulating microbes are not fully understood. Research must focus on the production of climate-resilient microbial strains, genomics-assisted selection of multi-trait strains, robust field validations, and co-development with local farming systems to ensure scalability.

-

Soil microbes improve soil structure by altering its physiochemical properties. Fungi and bacteria contribute to the formation and stabilization of soil aggregates. Fungal hyphae physically entangle soil particles, while fungi produce extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), such as glomalin, which act as a 'glue' binding particles together. Similarly, bacteria, cyanobacteria, and microalgae produce sticky compounds like extracellular polysaccharides and proteins that help cement soil particles, enhancing aggregate stability. For example, EPS produced by Sphingomonas paucimobilis and Caulobacter crescentus creates hydrophobic coatings on soil aggregates, making them more resistant to erosion[102]. Microbial activities, including enzymatic interactions, nutrient sharing, biofilm formation, and anaerobic–aerobic partnerships, facilitate the breakdown of complex organic matter and nutrient cycling, improving overall soil health and nutrient availability[103]. Environmental factors such as tillage, soil compaction, and chemical residues can disrupt these microbial networks. Research is needed to identify keystone species in soil aggregation and to quantify their contributions under different management systems. Incorporating soil structural metrics into soil health indices may better capture the impact of microbial interventions.

Some microbes are capable of purifying soil by mitigating the impact of soil pollutants, especially heavy metals, through the following processes (Table 4). This environmental pollution is a major concern as it affects the yield and the quality of food produced due to the overuse of fertilizers, pesticides, and other agro-products like livestock manure[104]. Certain microorganisms are capable of adsorbing and concentrating these toxic elements on the outer surfaces of their cells, thus sequestering them[105]. Some can synthesize enzymes that can convert heavy metals into forms that are less toxic or even non-soluble, thus decreasing their bio accessibility and translocation[106]. Some microbes can synthesize chelating agents or organic acids that sequester the heavy metals and form complexes or precipitates that are insoluble[107]. Some species can even transform certain heavy metals into volatile compounds, thus eliminating them from the soil[108]. The collective behavior of diverse microorganisms is often more efficient than that of individuals because of additive and mutually dependent metabolic processes. Techniques such as bio stimulation and bioaugmentation, where the addition of organic amendments or introduction of certain microbial strains help in increasing indigenous soil microbial activity in degrading or immobilizing the heavy metals[109].

Table 4. Microbes involved in bioremediation[105].

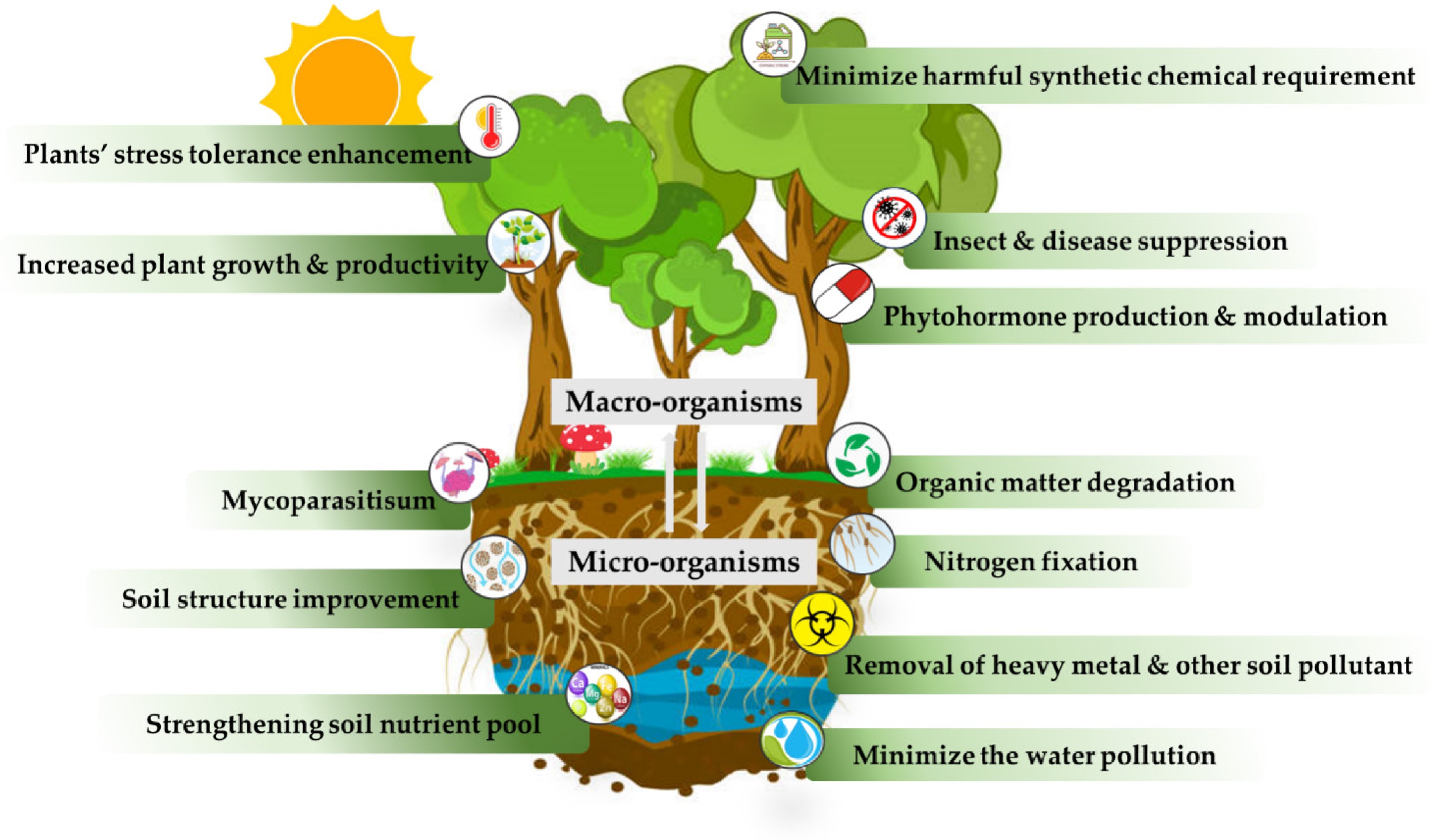

Heavy metal Micro-organism Average sorption efficiency (%) Chromium (Cr) Bacteria Acinetobacter sp. 87 Sporosarcina saromensis 82.5 Bacillus circulans 96 Bacillus cereus 78 Bacillus subtilis 99.6 Pseudomonas aeruginosa 72 Fungi Aspergillus sp. 92 Saccharomyces cerevisiae 95 Lead (Pb) Bacteria Cellulosimicrobium sp. 99.3–84.6 Methylobacterium organophilum 62.28 Bacillus firmus 98.3 Staphylococcus sp. 82.6 Cobalt (Co) Bacteria Vibrio fluvialis Mercery (Hg) Bacteria Enterobacter cloacae 28.6 Klebsiella pneumoniae 29.8 Pseudomonas aeruginosa 90 Bacillus licheniformis 70 Fungi Candida parapsilosis 80 Nikel (Ni) Bacteria Desulfovibrio desulfuricans 97.4–78.2 Flavobacterium sp. 25 Pseudomonas sp. 53 Fungi Aspergillus versicolor 30.5 Aspergillus niger 58 Copper (Cu) Bacteria Micrococcus sp. 55 Desulfovibrio desulfuricans 90.3–90.1 Bacillus firmus 74.9 Other than heavy metals, soils' natural microbial communities are engaged with removing or degrading various other pollutants such as hydrocarbons and petroleum products, chlorinated organic compounds, pesticides and herbicides, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), dyes and textile effluents, plastics, and microplastics[106]. But the potential capacity and rate depends on microbial species, the nature and concentration of the pollutant, and the environmental conditions. A summary of the benefits of the soil's natural microbial community on sustainable agriculture is shown in Fig. 4.

-

To increase microbial content and promote beneficial microbial partnerships in agricultural fields, several cost-effective actions can be implemented. First, maximizing soil health and quality is essential, followed by avoiding practices that hinder microbial multiplication.

Incorporating organic matter sources such as compost, manure, or green manures into the soil provides essential nutrients and energy for microbial growth[110]. Organic matter also enhances soil structure, aeration, and water-holding capacity, creating a favorable environment for microbial communities. Implementing diverse crop rotations and cover crops ensures a continuous supply of organic matter and root exudates[111,112]. Integrating trees, shrubs, and crops in agroforestry systems or practicing intercropping increases plant diversity, creating beneficial micro-climatic zones that foster microbial growth[113,114]. Maintaining soil coverage with mulch, cover crops, or crop residues helps retain soil moisture and regulate temperature, which are ideal conditions for microbial communities[115].

If purely organic farming is not feasible, integrated nutrient management can be adopted, combining organic and inorganic fertilizers to provide a balanced nutrient supply[116]. Proper irrigation scheduling, such as drip irrigation or deficit irrigation, helps maintain suitable soil moisture levels, avoiding anaerobic conditions or microbial dormancy due to drought[117]. Additionally, soil fertility can be improved with biochar and ash-like amendments[118−120].

Adopting reduced tillage or no-till farming preserves soil structure and minimizes disruption to microbial habitats[121]. The excessive use of chemical inputs, like synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and agrochemicals, can disrupt beneficial microbial communities and damage soil ecosystems[116]. It suppresses their growth and creates imbalances in soil pH and nutrient levels.

Growers can periodically apply biofertilizers containing beneficial microorganisms, such as rhizobia, azotobacter, and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria, which aid in nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, and plant growth promotion[122]. Similarly, microbial-based biopesticides can replace chemical pesticides, supporting a healthier soil ecosystem[123]. Additionally, different plant species can selectively recruit and support specific microbial communities, fostering a diverse and balanced soil microbiome.

-

While considerable progress has been made in characterizing the roles of soil microbes in agriculture, significant gaps remain. Many microbial inoculants perform inconsistently due to environmental variability, soil type incompatibility, or microbial competition. Moreover, the specificity of plant-microbe interactions challenges the development of universal solutions. Conflicting reports about the efficacy of certain microbial strains under abiotic stress, and limited understanding of their long-term ecological impacts, further complicate adoption. There is also debate over the effectiveness of single-strain vs consortia-based approaches. Addressing these gaps requires interdisciplinary research, open-access microbial databases, and harmonized testing protocols across agroecological zones.

Deciphering microbial functions

-

Identifying the full potential of each microbe in agriculture can be used to develop targeted microbial applications. Functional genomics enables the study of genes and active pathways in microbial communities through techniques such as metagenomics and metatranscriptomics[124]. Meta-genomics is the analysis of microbial communities directly from environmental samples, without the usual lab culturing[125]. This technology provides complete information about the diversity and functional potential of soil microbiomes. Such a study could reveal which microbes play key roles in essential functions like nutrient cycling, pathogen suppression, stress management, and growth promotion. Moreover, the molecular plant-microbe interactions studies help explain how plants recruit specific microbes through root exudates, and how such microbes impact plant physiology and development[126]. Understanding microbial networking, how microbes form complex networks and communicate through signaling molecules, can also help identify keystone species or functional groups that significantly impact soil health and plant productivity. By deciphering these microbial functions, scientists can design inoculants tailored to specific agricultural needs, such as promoting growth under drought conditions or enhancing resistance to pests.

Microbial breeding

-

Microbial breeding is a novel strategy described in choosing and optimizing persuasive characteristics of microbial strains for a beneficial impact on the agricultural system[127]. As in plant or animal breeding, microbial breeding begins with selection through cultivation, with researchers looking for strains with an inherent ability to perform specific functions such as nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, or suppression of specific pests and diseases. These strains may be cultured and isolated so that their quantity and potential can be enhanced. For example, beneficial mutations can be induced through chemical mutagens or the modern and more precise CRISPR, gifted gene manipulation to the microbial genome to produce strains with better characteristics, such as higher tolerance to stress or higher production of bacterial growth hormone[128]. Yet, the focus of the traditional approaches tends to be single-strain application, whereas microbial consortia design entails the development of microbial communities comprising multiple species that jointly provide improved value to plants and soil[129]. These consortia are comparatively better and have the potential to exhibit better results under different environmental conditions of environment than single strains. Microbial consortia can be tailored to specific crops and climate conditions, making them a powerful tool for climate-resilient and sustainable farming. By enhancing these microbial communities, farmers can improve crop yields and soil quality while reducing their dependence on chemical inputs[130]. By developing customized microbial products that are better suited to specific crops, soil types, or climates, microbial breeding can reduce the reliance on chemical fertilizers and pesticides.

Harnessing indigenous microbes

-

This approach can be identified as a way to implement the principles of sustainable agriculture by using microbes that are native to the given soil type and climate[131]. While the introduced microbes could fix nitrogen and solubilize phosphorus, indigenous microbes are more efficient than the introduced microbes since they are accustomed to the local stresses, including drought, salinity, or fluctuations in the pH of the soil[132]. Another advantage involves the use of native microbial communities in farming, which can also help in minimizing the use of chemicals and can be used as organic replacements for chemical fertilizers[133]. Promoting the use of local microbes might contribute to the rejuvenation and improvement of the soil's beneficial microbiome state, which would improve agricultural soil efficiency. Furthermore, the innovation based just on local microbial communities enables achieving regional microbial solutions, for instance, necessary in the area with a specific climate or soil that does not respond to the already existing microbial products.

By focusing on synthetic biology and microbial engineering, microbiome editing, machine learning, and AI in plant science, future microbial research can significantly advance sustainable agriculture[134]. These approaches offer innovative solutions to enhance crop health and yield while reducing their negative effects on the environment.

Integrating microbial solutions with modern technology not only enhances the efficacy of microbial applications but also aligns with sustainable agricultural practices. Monitoring and managing soil microbiomes are necessary for sustainable agriculture. As a summary, it includes: (1) sustainable agricultural practices like reduced tillage, cover cropping, and organic amendments; (2) uses of advanced sensor technology and data analytics, which allow for real-time monitoring of soil microbiomes; and (3) implementing practices such as crop rotation, reduced chemical input, and organic farming, which can sustain beneficial microbial communities.

-

The world faces immense challenges in achieving global food security while preserving the integrity of natural ecosystems. Conventional agricultural practices have contributed to soil degradation, water pollution, and biodiversity loss, necessitating a shift towards more sustainable and regenerative approaches. In this context, harnessing the power of microbial partnerships emerges as an important solution to address these challenges. Natural microbial community plays vital roles in nutrient cycling, pathogen suppression, stress tolerance enhancement, and overall plant growth promotion. Fostering symbiotic relationships between plants and beneficial microorganisms would unlock the potential for yield-enhancing and climate-resilient agricultural practices. From nitrogen-fixing bacteria to phosphate-solubilizing fungi and arbuscular mycorrhizal associations, these microbial partnerships offer a nature-based solution to minimize the dependency on synthetic inputs and suppress environmental impact. However, identifying true microbial partnerships requires a multifaceted approach. Continued research efforts are needed to identify new microbes and their synergistic interactions, design optimized microbial consortia tailored to specific crop types and environmental conditions, and develop effective delivery and monitoring systems for these beneficial microbes. Additionally, integrating microbial partnerships with precision agriculture techniques can enhance the efficiency and targeted application of these microbial inoculants. Interdisciplinary collaborations among microbiologists, plant scientists, agronomists, and climatologists will be crucial to accelerate the translation of these microbial solutions into practical agricultural applications. As the world strives to meet the growing global demand for food while mitigating the impact of climate change, embracing microbial partnerships contributes to a sustainable and nature-based approach to agriculture.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Dissanayaka NS, Atapattu AJ; data collection: Dissanayaka NS; analysis and interpretation of results: Udumann SS, Nuwarapaksha TD; draft manuscript preparation: Dissanayaka NS, Udumann SS. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

We would like to express our appreciation to the technical staff of the Agronomy Division of the Coconut Research Institute. We would like to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and constructive evaluation.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Dissanayaka NS, Udumann SS, Nuwarapaksha TD, Atapattu AJ. 2025. Microbial partnerships in agriculture: boosting crop health and productivity. Circular Agricultural Systems 5: e013 doi: 10.48130/cas-0025-0011

Microbial partnerships in agriculture: boosting crop health and productivity

- Received: 28 March 2025

- Revised: 08 October 2025

- Accepted: 11 October 2025

- Published online: 05 November 2025

Abstract: Plants and microbial organisms develop close symbioses that have a significant influence on agricultural productivity and plant health. These 'agricultural engines' have continuously supported balancing global food security from historical times. Against the backdrop of the global challenges faced by modern agriculture, including soil degradation and over-reliance on synthetic inputs, this review examines the intricate relationships within the soil microbiome, and their impact on sustainable crop production. It further investigates the pivotal functions of these partnerships in nutrient cycling, biotic stress suppression, hormone modulation, and stimulating and enhancing the flourishing growth of crops. Highlighting the importance of plant-microbe relationships, this study explores the potential of biological nitrification inhibitors, biocontrol agents, and biofertilizers, specifically, nitrogen-fixing bacteria and phosphorus-solubilizing microbes, to optimize nutrient use efficiency, suppress biotic stress, enhance nutrient availability for crops, and mitigate climate change. Furthermore, challenges related to environmental factors and the commercial adoption of microbial products are also scrutinized. The review concludes by outlining future research directions and envisioning the integration of microbial partnerships into sustainable climate resilience agricultural practices, thereby offering a holistic approach to address current agricultural challenges and pave the way for a more resilient and environmentally friendly food production system. This will help guide cutting-edge microbiome-based solutions, to improve global food production and agricultural resource use efficiency in the years to come.