-

The tea plant (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze), originating from southwest China, represents one of the most economically significant non-alcoholic beverage crops globally. Recently, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) promulgated a new set of health food regulations, which included tea devoid of added cream and sugar, with a calorie content of less than five[1]. As a healthy beverage, unlike water and coffee, tea contains a variety of substances beneficial to human health which retain their biological activity after processing, including polyphenols, theanine, caffeine, and aroma substances[2]. To better understand the genetic basis of secondary metabolism in tea plants, functional genomics research is critically important. However, as a self-incompatible plant, the tea plant is characterized by rich genetic variation, which creates an obstacle for its research. However, along with the development of next-generation sequencing technology, the study of the tea plant genome has made a breakthrough[3]. Metabolomics has emerged as a foremost omics-based technology, allowing researchers to comprehensively characterize diverse and dynamic metabolites within biological systems. Among all metabolomics studies of economic crops, the metabolome of tea plants is increasingly emphasized as it is highly altered due to varietal and environmental changes, so there are significant differences from other Camellia plants in terms of secondary metabolites[4,5]. Metabolomics is now effectively used in multidisciplinary studies along with genomics, and transcriptomics. The application of multidisciplinary metabolomics of tea plants, such as the joint analysis of millions of variant information and differential metabolites, can more accurately localize the target genes and guide the direction of functional genome research[6]. What's more, targeting the role of the environment in the regulation of secondary metabolism also requires the use of extensive germplasm resources as a basis. Although genomic and metabolomics techniques for tea plants have been comprehensively reviewed[5,7], precise targeting of metabolism-related genes through natural and artificial populations, and the roles of the environment in the regulation of secondary metabolites still have limitations. To provide perspectives for addressing this knowledge gap, this review systematically summarizes the latest research progress on the tea plant's various metabolites and the genetic mechanism underlying them.

-

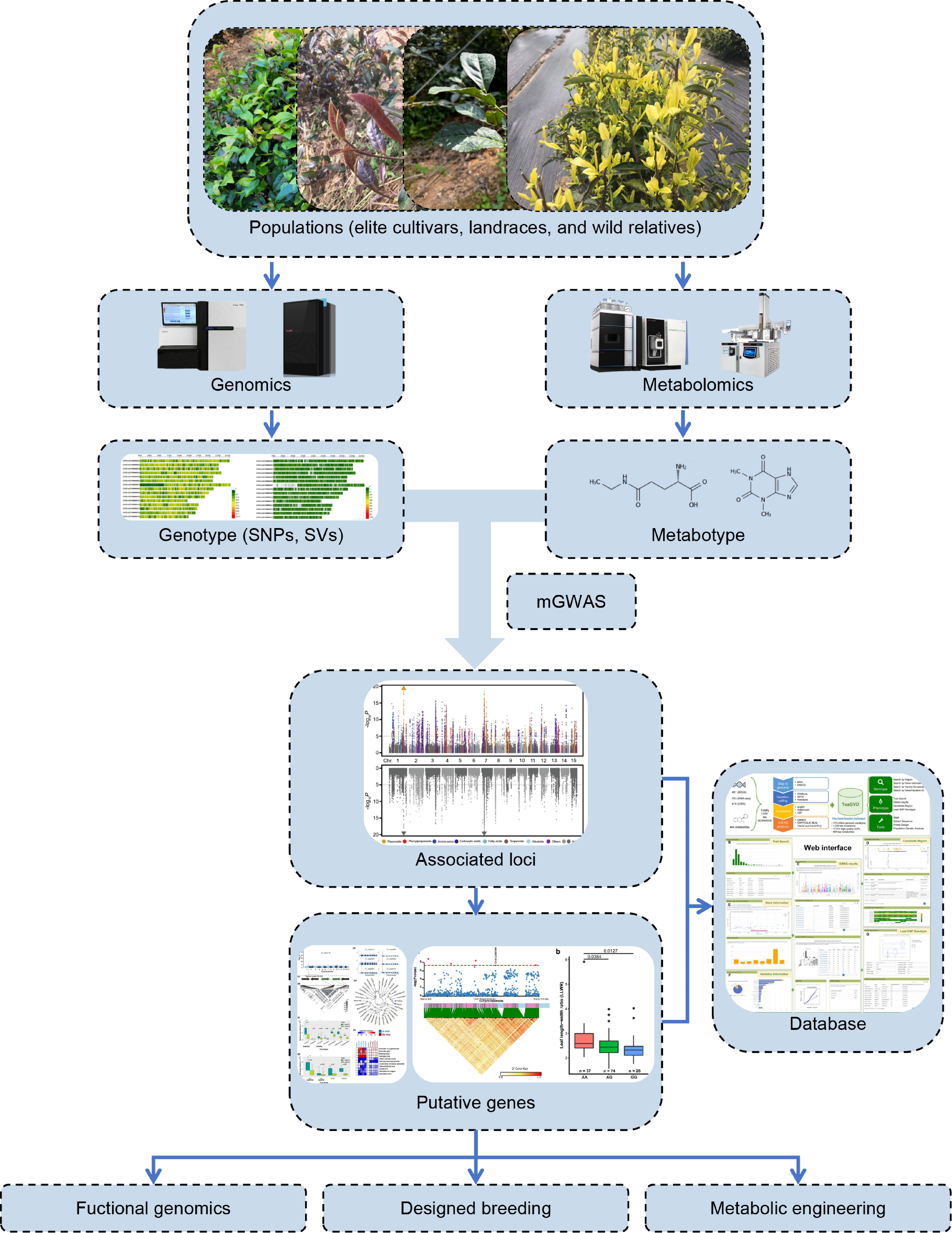

The metabolic profile of tea plants represents a sophisticated biochemical network comprising primary and specialized secondary metabolites, collectively shaping its ecological adaptability and therapeutic value[2,7]. Primary metabolites, including carbohydrates, amino acids, lipids, vitamins, nucleotides, and organic acids, form the foundation for cellular energy metabolism and structural maintenance[8]. However, it is the orchestrated production of secondary metabolites—particularly catechins, purine alkaloids, theanine, and volatile aromatic substances—that exhibit dual functionality. These substances respond to biotic and abiotic stresses while concurrently conferring multisystem health benefits to humans through dietary consumption (Fig. 1)[9].

Figure 1.

Landscape of bioactive metabolites of tea plant and environmental response. MeJA, Methyl Jasmonate; MeSA, Methylsalicylate; GABA, γ-aminobutyricacid; Met, Methionine; IPP, Isopentenyl pyrophosphate; Ala, Alanine; Glu, Glutamic acid; DHS, 3-Dehydroshikimic acid; GA, Gibberellin; JA, Jasmonic acid; ABA, Abscisic acid, Pi, phosphate. Arrows link precursors from primary metabolism (dotted line circle) to the end products. ABA, GA, and JA represent phytohormone metabolism or signaling genes.

Polyphenols, accounting for 18%−36% of tea leaf dry weight, include flavonoids and phenolic acids[10]. Flavonoids can be divided into five groups (flavones, flavonols, flavanones, flavanols, and anthocyanins) according to the degree of oxidation of the C-ring[11]. Among these flavonoids, flavan-3-ols (catechins) occupy the largest share of polyphenols and have better biological activity, which consists of catechin (C) and its derivatives, including epicatechin (EC), epicatechin gallate (ECG), gallocatechin (GC), epigallocatechin (EGC), epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), and epigallocatechin 3-O-(3-O-methyl) gallate (EGCG3''Me)[12]. In human research, catechins have been demonstrated to remove harmful reactive oxygen components, exhibit potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, and anticancer activities[13]. Catechins and their derivatives are known to be key factors contributing to the astringent and bitter taste of tea[14]. Environmental stress causes the accumulation of reactive oxygen species in tea plants, leading to oxidation of cellular lipids and proteins and ultimately cell death, but flavonoids can reduce the formation of hydroxyl radicals and thus reduce oxidative stress in cells[15]. Purine alkaloids are the main alkaloids in tea plants, including caffeine (1,3,7-trimethylxanthine), theobromine (3,7-dimethylxanthine), theophylline (1,3-dimethylxanthine), and theacrine (1,3,7,9-tetramethyluric acid) depending on the number and position of methyl groups on the purine ring[16]. Similar to catechins, alkaloids offer a part of the bitter taste in tea infusion and could be used as a stimulant to improve cognitive performance[17]. Caffeine, occupying about 95% of total alkaloids, is recognized as an important secondary metabolite to help plants withstand biotic stresses[18]. As the predominant non-proteinogenic amino acid in tea, L-theanine (γ-glutamyl-L-ethylamide) constitutes the major component of free amino acids that critically define tea's flavor profile, not only imparting the characteristic umami taste comparable to sodium L-glutamate but also modulating the intricate balance between bitter and astringent sensations and pleasant flavor[19]. For humans, L-theanine has many beneficial health effects such as protecting neurons and regulating blood pressure[17]. As for the tea plant, degradation of chloroplast proteins under dark conditions leads to up-regulation of theanine synthesis[20], while degradation of theanine can be activated by light[21]. The aroma of tea is also one of the important factors affecting sensory quality[22], including volatile terpenes, phenylpropanoids/benzenoids, fatty acid derivatives, and compounds derived from carotenoids[23]. Tea plants activates stress response and pollinator attraction by releasing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) for interplant communication like (E)-2-hexenal, linalool, (E)-nerolidol, MeJA, and MeSA[24].

Environmental factors include light, temperature, moisture, soil, biology, geography, which regulate secondary metabolism[25]. Also as secondary metabolites, phytohormones play an indispensable role in the whole life history of plants, including growth, reproduction, and stress resistance[26]. Phytohormones constitute an intricate regulatory network coordinating secondary metabolism in tea plants through transcriptional regulation, alternative splicing mechanisms, and environmental signal integration[27]. The regulatory effects of phytohormones are primarily mediated by key components of hormone signaling, which act on enzymes involved in the synthesis and degradation of secondary metabolites[28] (Fig. 1). Gibberellin (GA) enhances theanine biosynthesis via GA-CsWRKY71 signaling, through upregulation of CsTSI expression by down-regulating the expression of CsWRKY71[29]. This process demonstrates GA's central role in nitrogen allocation, where endogenous GA3 levels at the bud emergence stage exhibit a significant positive correlation with theanine accumulation. The coordination between GA signaling and nitrogen metabolism underscores its regulatory specificity in secondary metabolite production. In jasmonic acid (JA) signaling, the JAZ-MYC regulatory module dynamically controls catechin biosynthesis through developmental-stage-specific mechanisms[30]. Three alternatively spliced CsJAZ1 variants (CsJAZ1-1/-2/-3) establish a hierarchical regulatory system: full-length CsJAZ1-1 physically interacts with CsMYC2 to inhibit transcriptional activation, while truncated CsJAZ1-3 destabilizes the complex through competitive binding. This splicing-based regulation allows precise modulation of JA signaling intensity during developmental transitions. Under high-temperature stress (40 °C), thermosensitive transcription factors CsHSFA1b/2 upregulate CsJAZ6 expression, subsequently binding to the CsEGL3-CsTTG1 complex to reduce catechin accumulation[31]. Furthermore, phosphorus deficiency triggers reciprocal regulation between phosphate starvation response regulators (CsPHR1/2) and CsJAZ3, synergistically activating the CsANR1-CsMYB5c transcriptional axis to drive catechin synthesis, revealing cross-talk between nutrient signaling and JA pathways[32]. Under cold stress, JA signaling was activated and CsMYB68/CsMYB147 were significantly up-regulated by JA, with the activator interacting with CsMYC2 to form the MYC2-MYB complex, which in turn regulated linalool synthase[33]. Abscisic acid (ABA) coordinates anthocyanin metabolism through tissue-specific and stress-responsive mechanisms. Metabolomic profiling identified a significant ABA enrichment in purple buds compared to mature leaves, displaying a developmental gradient inversely correlated with leaf maturation[34]. This spatial-temporal pattern mirrors anthocyanin accumulation dynamics, suggesting ABA-mediated activation of transcription factors regulating anthocyanin biosynthetic genes. Under combined stress conditions, volatile (Z)-3-hexenol modulates ABA homeostasis via UGT85A53-mediated glycosylation, enhancing reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging efficiency while optimizing stomatal conductance[35]. Despite the existence of a number of relevant studies, there is a lack of research on phytohormone-secondary metabolism interactions between different tea plant germplasm resources at different stages of growth and development, or in response to different adversities and stresses. The natural differences engendered by germplasm resources have the potential to facilitate the localization of key genes with greater efficiency and precision. However, this is difficult to carry out because of the lack of phenotyping and precise characterization of germplasm resources. What's more, due to the lack of a stable genetic transformation system, and the absence of a method for detecting and analysing the phytohormone and their derivatives, a systematic and comprehensive analysis of phytohormones in the tea plant is desperately needed.

-

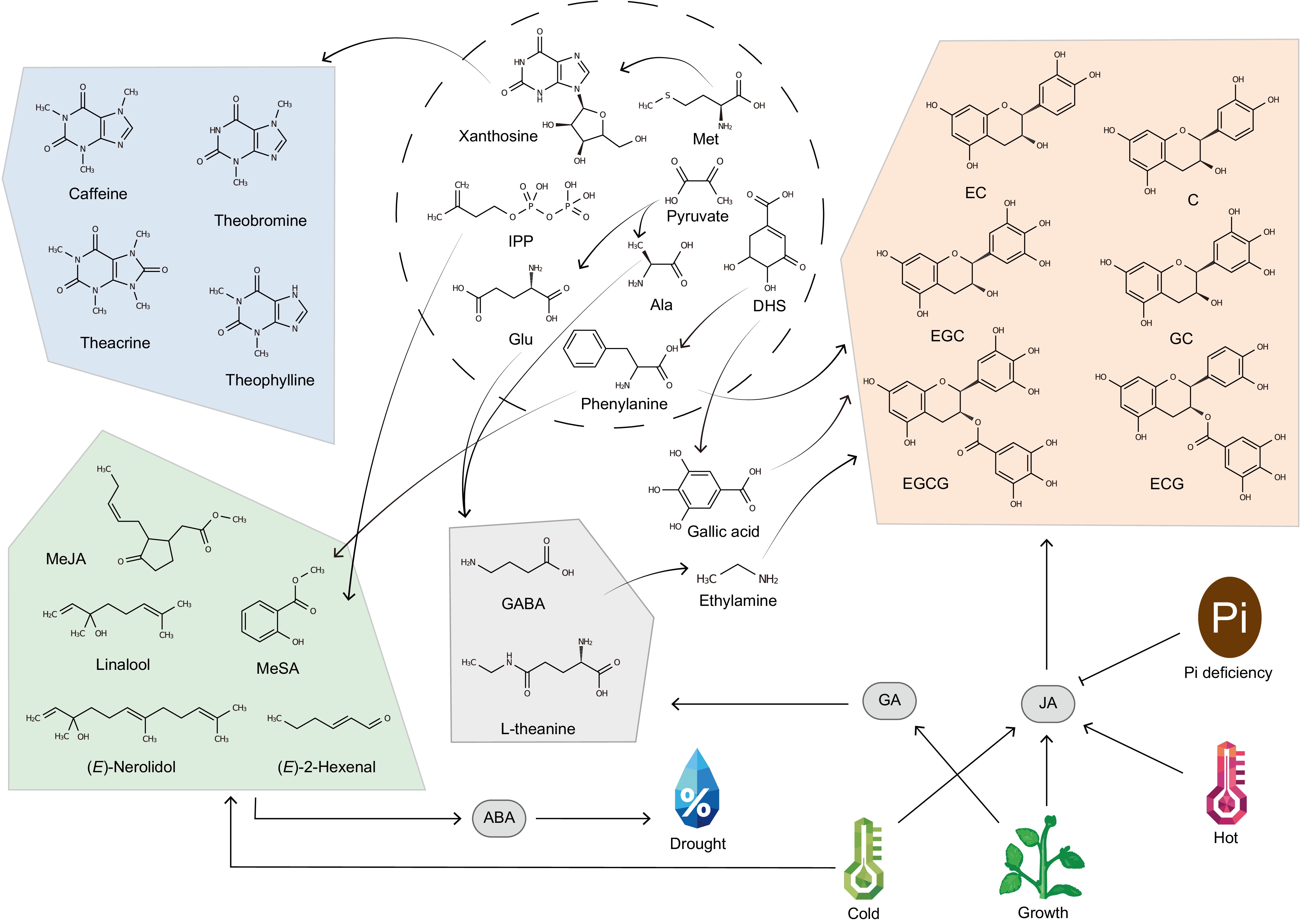

Germplasm refers to whole genetic material found in certain crops and its wild relatives, including all the alleles of different genes. Tea plant germplasm genetic diversity, encompassing elite cultivars, landraces, and wild relatives within Camellia Sect. Thea, serves as a cornerstone for breeding and adaptive evolution research. Germplasm are taxonomically categorized under two primary systems: Ming recognized 12 species and six varieties[36], while Chen simplified this to five species and two varieties, including C. tachangensis, C. taliensis, C. crassicolumna, C. gymnogyna, and C. sinensis, C. sinensis var. assamica, var. pubilimba[37]. Southwest China, particularly Yunnan and Guizhou provinces, remains the epicenter of tea biodiversity, hosting wild populations of C. taliensis and C. gymnogyna alongside ancient cultivated landraces[38]. Globally, tea cultivation has expanded to over 50 countries, with distinct ecological adaptations observed in assamica-type teas thriving in tropical regions (e.g., India, Kenya) and sinensis-types dominating temperate zones (e.g., Japan, China)[39,40].

To mitigate genetic erosion caused by habitat loss and climate change, both in situ and ex situ conservation strategies are prioritized. China has established protected areas in Yunnan and Guizhou, integrating UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization)-recognized cultural landscapes like the Jingmai Mountain ancient tea forests[41]. Globally, major ex situ repositories include China's National Germplasm Tea Repository (CNGTR, 3,700 accessions)[37], Japan's National Agriculture Research Organization Institute of Fruit Tree and Tea Science (NIFTS, 7,800 accessions)[42], and India's Tea Research Association, the Tocklai Experimental Station (TRA, TES, 2,100 accessions)[39]. Core collections, such as Sri Lanka's 64-accession and China's 532-accession primary core, simplify resource utilization by minimizing redundancy while preserving genetic breadth[43,44]. Recently, a study combined 1,325 Camellia accessions to uncover the genetic basis behind metabolic and agronomic traits of tea plants (Fig. 2), which collected 870 C. sinensis var. sinensis, 356 C. sinensis var. assamica, and 25 C. sinensis var. pubilimba, as well as, 74 C. sinensis relative species (including 40 C. taliensis, 17 C. tachangensis var. remotiserrata, 15 C. quinquelocularis, one C. sasanqua, and one C. oleifera)[45].

Figure 2.

Profiling of the worldwide distribution of Camellia accessions in a previous resequencing study[45]. The orange, blue, and green components of the figure represent wild, landrace, and elite Camellia accessions. Size of the cross logo represents the total accessions number of the country or province (source of map: GS (2016)1666).

Phenotypic diversity in the tea plant germplasm is exemplified by variations in leaf morphology (e.g., leaf size, serration), flower structure, and secondary metabolite profiles. For instance, C. sinensis var. assamica exhibits larger leaves and higher catechin content compared to the smaller-leaved C. sinensis var. sinensis varieties[46]. Biochemical analyses of 1,500 accessions in CNGTR revealed significant geographical gradients: tea polyphenols peak in Yunnan (38% dry weight), while catechin levels are highest in Hunan accessions[47]. Additionally, anthocyanin-rich purple tea 'Zijuan' and chlorophyll-deficient albino tea 'Baiye 1' demonstrate unique metabolic adaptations[48], such as stress resistance[49], and compensatory amino acid accumulation[50]. These traits underscore the interplay between the genetic background and environmental stressors.

As a perennial woody species with high heterozygosity, abundant repetitive sequences (~80%), and a large genome (~3.0 Gb)[51], the tea plant presents formidable challenges for genome assembly. However, the integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS), third-generation long-read sequencing, and advanced assembly techniques like Hi-C has overcome these barriers[52] (Table 1), facilitating the generation of high-quality reference genomes and their application in functional genomics, metabolic pathways, evolutionary biology, and molecular breeding[3]. In conclusion, assembled genomes have revolutionized the study of the tea plants[53−57].

Table 1. Progress in tea plant genome research.

YK10 SCZ V1.0 SCZ V1.1 SCZ V1.2 BY DASZ LJ43 HD TGY DY MJ TV 1 Seimei Chun gui ZJ Sequencing technology 2rd-NGS 2rd-NGS + SMRT SMRT + Hi-C Hi-C SMRT + Hi-C SMRT + Hi-C SMRT + Hi-C HiFi + Hi-C HiFi + Hi-C ONT + Hi-C HiFi + Hi-C HiFi + Hi-C HiFi + Hi-C HiFi + Hi-C Contig assembly size (Gb) 2.57 2.89 2.94 2.98 2.92 3.11 3.26 2.94 3.06 2.97 2.93 3.16 3.11 3.06 Contig N50 (kb) 19.96 67.07 600.46 − 625.11 2,589.80 271.33 2,610 1,940 723.70 − − 160,000.09 2,286.92 Scaffold N50 (Mb) 0.45 1.39 − 218.10 195.68 204.21 143.85 − − 207.72 199.23 214.86 − − Number of genes 36,951 33,932 50,525 32,331 40,812 33,021 33,556 43,779 42,825 34,896 30,069 55,235 54,797 39,673 Average full length of genes (bp) 6,174 6,821 5,237 7,127 6,263 7,927 10,815 5,452 5,651 6,961 − − − 7,493 Repeat sequence

(% of genome)80.89 − 86.78 − 74.13 87.41 80.06 70.75 78.15 86.77 70.61 79.4 73.97 84.17 Complete genome BUSCOs (%) 94 90 90.6 − 88.13 93.2 88.36 95 93.7 87.78 90.7 94.8 91.9 94.12 Ref. [51] [58] [64] [61] [60] [6] [54] [62] [63] [53] [55] [56] [57] [65] The first breakthrough emerged in 2017 with the draft genome assembly of C. sinensis var. assamica 'Yunkang 10'[51], which utilized Illumina short-read sequencing. This 3.02 Gb assembly revealed that long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons, particularly Ty1/copia and Ty3/gypsy, dominated genome expansion, accounting for 80.9% of repetitive content. Two whole-genome duplication (WGD) events were identified, with the recent Ad-β event (0.36 Mya) driving the expansion of gene families linked to flavonoid biosynthesis and stress responses. Comparative transcriptomic analyses further highlighted elevated expression of N-methyltransferases (NMTs) and flavonoid-related genes in tea leaves, explaining their suitability for beverage production compared to non-Thea Camellia species. Because SMRT (single molecule real-time) technology has longer read lengths and higher accuracy, it is suitable for sequencing complex genomes[52]. Subsequent studies leveraged hybrid sequencing approaches to improve assembly quality. In 2018, the genome of C. sinensis var. sinensis 'Shuchazao' was assembled using Illumina and PacBio platforms[58], achieving a scaffold N50 of 1.39 Mb and annotating 33,932 protein-coding genes. Divergence time estimates between sinensis and assamica varieties (0.38−1.54 Mya) and the identification of tea-specific gene families, such as serine carboxypeptidase-like (SCPL) genes involved in catechin acylation, underscored the role of tandem duplications in metabolic diversification. Hi-C (High-through chromosome conformation capture) technology contributes to the clustering and sorting of assembled fragments, and Hi-C orients to the correct location, taking genome assembly further to the chromosome level[59]. By 2020, chromosome-level assemblies of tea plants became feasible through Hi-C and PacBio HiFi sequencing. The 'Biyun' genome (2.92 Gb, scaffold N50: 195.68 Mb) anchored 97.88% of sequences to 15 pseudochromosomes, resolving the repetitive landscape dominated by Tat and Tekay LTR retrotransposons[60]. Parallel efforts on 'Shuchazao' achieved a scaffold N50 of 218.1 Mb, revealing that 28.6% of genes arose from tandem duplications post-CRT (Camellia recent tetraploidization) event, which facilitated the diversification of catechin and caffeine biosynthesis pathways[61]. These assemblies enabled precise mapping of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for key metabolites, linking polyploidy to molecular breeding. Wild and ancient tea resources have also been genomically characterized. The DASZ genome (3.11 Gb), derived from a Yunnan wild tea plant, identified 176 loci associated with catechin and gallic acid variation through genome-wide association studies (GWAS)[6]. But metabolic profiling revealed minimal differentiation between wild and cultivated accessions, suggesting limited domestication signatures. PacBio HiFi sequencing uses circular consensus reads to generate highly accurate (≥ 99%) long reads, dramatically reducing errors and improving variant detection to enable precise haplotype phasing and diploid genome assembly compared to standard SMRT reads. In 2021, the diploid genome of oolong tea cultivar 'Huangdan' was phased into two haplotypes (2.90 and 2.97 Gb) using PacBio HiFi and Hi-C, uncovering 23.57 million SNPs and allele-specific expression patterns[62]. Notably, terpene synthase (TPS) gene family expansions correlated with aroma biosynthesis, providing molecular insights into the cultivar's high-aroma characteristics. Similarly, the 'Tieguanyin' genome (3.06 and 2.92 Gb haplotypes) revealed 14,691 genes with allelic variations, of which 1,528 exhibited tissue-wide allele-specific expression, suggesting dominance effects in clonal propagation[63]. These haplotype assemblies highlighted the impact of heterozygosity on trait variation, helping us understand genetic mechanisms in breeding practices.

Pangenome enhances plant research by uncovering comprehensive genetic diversity, enabling novel gene discovery, illuminating evolution and adaptation, and promoting crop trait-based improvement. In 2023, a high-quality pangenome of 22 elite C. sinensis cultivars, representing broad genetic diversity across three major varieties (C. sinensis var. sinensis, assamica, and pubilimba) was constructed. Assembled genomes averaged 3 Gb in size, and contig N50 ranged from 361 kb (LJ43) to 2,237 kb (BHZ), with 97.4% of sequences anchored to chromosomes. Notably, 887,986 structural variations were identified (435,505 deletions, 421,642 insertions, 6,595 duplications, 24,244 inversions), covering 5,959 Mb (200% of the genome). What's more, 75.2% of structural variations (SVs) overlapped with transposable elements (TEs), particularly LTRs and TIRs, indicating TE activity as a major driver of genomic diversity[66]. Up to this point, structural variation has been increasingly emphasised by researchers. The genome of the purple-leaf tea cultivar 'Zijuan' (C. sinensis var. assamica) was assembled using PacBio and Hi-C (3.06 Gb, N50: 214.76 Mb). The genome contains a large number of repetitive sequences, accounting for 84.17% (2.58 Gb) of the genome, with 2.25 Gb being TEs. A comparison of the SVs was undertaken, which helps to identify true 'purple bud tea' in breeding practices, thus avoiding potential misinterpretation of buds that turn purple as a result of environmental stresses[65].

Epigenetics is emerging as a research hotspot in genomics. 3D genome architecture, encompassing chromosomal territories, A/B compartments, topologically associating domains (TADs), and chromatin loops, plays a pivotal role in gene regulation by spatially organizing distal cis-regulatory elements into proximity with target genes, regulating secondary metabolite diversity in tea plants[67]. A compartments, enriched with active chromatin markers and higher gene expression, contrast with B compartments, which exhibit repressive epigenetic features such as elevated DNA methylation and transposon density. SVs and TEs are unevenly distributed across these compartments, with SVs preferentially enriched in A compartments and TEs localized near TAD boundaries. High-resolution 3D chromatin maps reveal that TADs and chromatin loops orchestrate the expression of key genes involved in secondary metabolism, such as those in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway and terpene synthase families. For instance, differential chromatin accessibility within TADs regulates the expression of F3'5'H, affecting the accumulation of specialized metabolites like EGC and EGCG[68]. Enhancer-promoter loops further integrate genetic and epigenetic variations to fine-tune the synthesis of aroma compounds, including phenylethyl alcohol and jasmone[67].

-

Advanced qualitative and quantitative techniques aim to provide comprehensive measurements of the entire set of metabolites. What's more, the integration of metabolomics into genetic resources research has revolutionized the understanding of biochemical diversity in tea plants. By coupling metabolic profiling with genomic tools, researchers can dissect the genetic basis of key quality-related metabolites and harness this knowledge for precision breeding.

-

Metabolomics utilizes high-throughput analytical techniques to systematically identify and quantify metabolites, providing a 'snapshot' of the biochemical state of tea plants. Mass spectrometry (MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy are the core technologies in this field. The breeding process requires metabolite detection in different tea cultivars, but the complexity of the tea matrix may be lost during sample extraction, derivatization, and separation. By analyzing the response of atomic nuclei to radiofrequency radiation in a magnetic field, NMR can elucidate metabolite structures accurately, thus it is suitable for identifying a wide range of tea metabolites. When different metabolites are detected, each metabolite has a specific chemical shift in the NMR pattern. For instance, caffeine exhibits characteristic signals at 3.22, 3.38, 3.77, and 7.63 ppm, while theanine and ECG show peaks at 1.10−7.97 ppm, and 4.81 ppm, respectively[69]. Moreover, Cui et al. combined NMR with machine learning algorithms to accurately identify marker metabolites such as caffeine, malic acid, lysine, and β-glucose from 219 black tea samples[70]. Therefore, a chemical fingerprint of black tea processing suitability has been constructed, which will be helpful for the breeding of specialized cultivars for black tea in the future. However, the relatively low sensitivity of NMR makes it difficult to detect low-abundance metabolites. In comparison, GC-MS, and LC-MS have clear advantages in both sensitivity and resolution[71]. GC-MS is suitable for separating and detecting VOCs. Two hundred and four volatile metabolites were identified in hybrids and their parents ('TGY' and 'HD') through HS-SPME-GC-MS, among which terpenes showed the apparent hypergamy[72]. This demonstrates that GC-MS is an effective analytical method for identifying and differentiating the complex volatile compounds in tea leaves and for providing a comprehensive characterization of their aroma components. The recent widespread application of GC-O-MS technology has accelerated the study of the characteristic aroma substances in tea, but the large-scale use of GC-O-MS in germplasm resources needs to be further investigated. Compared with GC-MS, LC-MS can effectively separate both polar and nonpolar compounds[73], making it particularly useful for detecting nonvolatile compounds such as flavonoids and purine alkaloids[74,75]. LC-MS has been employed in flavor studies of Assam tea, identifying 32 metabolites associated with tea flavor, such as theanine, caffeine, and EGC. Among these, 13 metabolites showed seasonal variation trends similar to EGCG, revealing dynamic fluctuations in the chemical constituents of tea leaves and their impact on quality[76]. Another study used LC-MS/MS to analyze 'Yabukita' tea, successfully identifying phenylpropanoid derivatives with antioxidant properties, providing new insights into the potential bioactive components in tea leaves[77]. Thus, LC-MS demonstrates remarkable analytical advantages and application potential in detecting nonvolatile substances related to tea flavor.

In tea metabolomics research, although conventional MS techniques have been widely applied, challenges remain in the separation of structurally similar, low-abundance, or complex matrix metabolites. Emerging technologies such as ion mobility mass spectrometry (IM-MS) and time-of-flight mass spectrometry (TOF-MS) are also gradually being introduced into tea metabolomics research[78]. HS-GC-IMS has been successfully applied to the analysis of isomers in Huaguo tea, enabling the precise differentiation of structurally similar compounds that are difficult to identify by GC-MS, such as ethyl hexanoate/hexyl acetate and 4-methyl-1-pentanol/2-methyl-1-pentanol, based on differences in ion mobility ratio. Due to variations in mass, charge, and collision cross-sections, these isomers impart a unique floral and fruity aroma to the tea[79]. Meanwhile, Wang et al. combined GC-MS and GC × GC-TOFMS to accurately monitor the dynamic changes of 244 volatile metabolites during the processing of fresh-aroma green tea, pinpointing more than 10 key odor components including linalool, heptanal, and 2-pentylfuran[80]. Several attempts have been made to utilize ultra performance liquid chromatography triple-quadrupole linear ion-trap tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-QTRAP-MS) for broad-targeted metabolomic studies that investigate metabolic shifts in phytohormones in relation to aviation mutagenesis[81]. Advancements in resolution and sensitivity offered by these emerging mass spectrometry techniques provide robust technical support for a comprehensive analysis of tea flavor and quality.

In the study of tea flavor metabolites, three metabolomics strategies are primarily employed based on the detection targets: targeted, non-targeted, and widely targeted metabolomics[82]. While focusing on specific metabolites, targeted metabolomics strategies are analyzed by focusing on key substances. This strategy was applied to investigate flavor metabolites like flavonoids, lipids, and amino acid derivatives[83]. Moreover, this strategy elucidated changes in taste-related amino acids during the withering of black tea, revealing the dynamic regulation of amino acids and their driving proteins, thereby providing theoretical support for understanding how the sensory quality of tea is formed[84]. However, targeted metabolomics has certain limitations in detecting unknown metabolites, and untargeted metabolomics strategies compensate for this gap through high-throughput analyses[85]. Untargeted metabolomics has demonstrated significant advantages in high-throughput detection in the study of 'Tieguanyin' and Oolong tea cultivars. For example, in 'Tieguanyin', researchers detected 3,811 and 2,798 metabolic signals in the positive and negative ion modes, respectively. From these, they identified differential metabolites encompassing 11 categories—such as flavonoids, alkaloids, and phenolic amines—and discovered various tissue-specific compounds, including two rare A-type proanthocyanidins and two unique floral hydroxycinnamoylamides. This provided a systematic and comprehensive analysis of the metabolic diversity of the 'Tieguanyin' cultivar[86]. Similarly, in the identification of oolong tea cultivars, 14,741 metabolic signals were detected in both positive and negative ion modes, with 354 metabolites ultimately identified. These covered multiple classes of compounds, including flavonoids, phenolic acids, alkaloids, amino acids, and their derivatives. By screening 10 key marker metabolites, highly similar oolong tea cultivars could be effectively distinguished, providing a scientific basis for tea quality control and cultivar identification[87]. Although untargeted metabolomics offers broad coverage, its sensitivity, specificity, and quantitative accuracy are relatively low. In contrast, a widely targeted metabolomics strategy combines the advantages of both untargeted and targeted metabolic detection, enabling more thorough and accurate metabolic analyses[88]. Wang et al. demonstrated the advantages of widely targeted metabolomics in oolong tea research by successfully identifying 801 nonvolatile compounds, thus achieving the broad coverage of untargeted approaches while maintaining the high sensitivity of the targeted analysis. They identified 370 distinct metabolites from various producing regions, screened 35 region-specific markers, and linked 81 key compounds to sensory traits, effectively analyzing the mechanisms underlying flavor differences among oolong teas from different regions[89]. This strategy integrates the strengths of traditional targeted and untargeted approaches, overcoming the limitations of both. In situ detection methods are critical to detect spatial and tissue-specific metabolic dynamics. A study on the distribution pattern of B-ring trihydroxylated flavonoids in the outer layer of tea buds using the DESI-MSI method, led to an in-depth investigation of the biosynthetic mechanisms of flavonoids in tea plants[90].

-

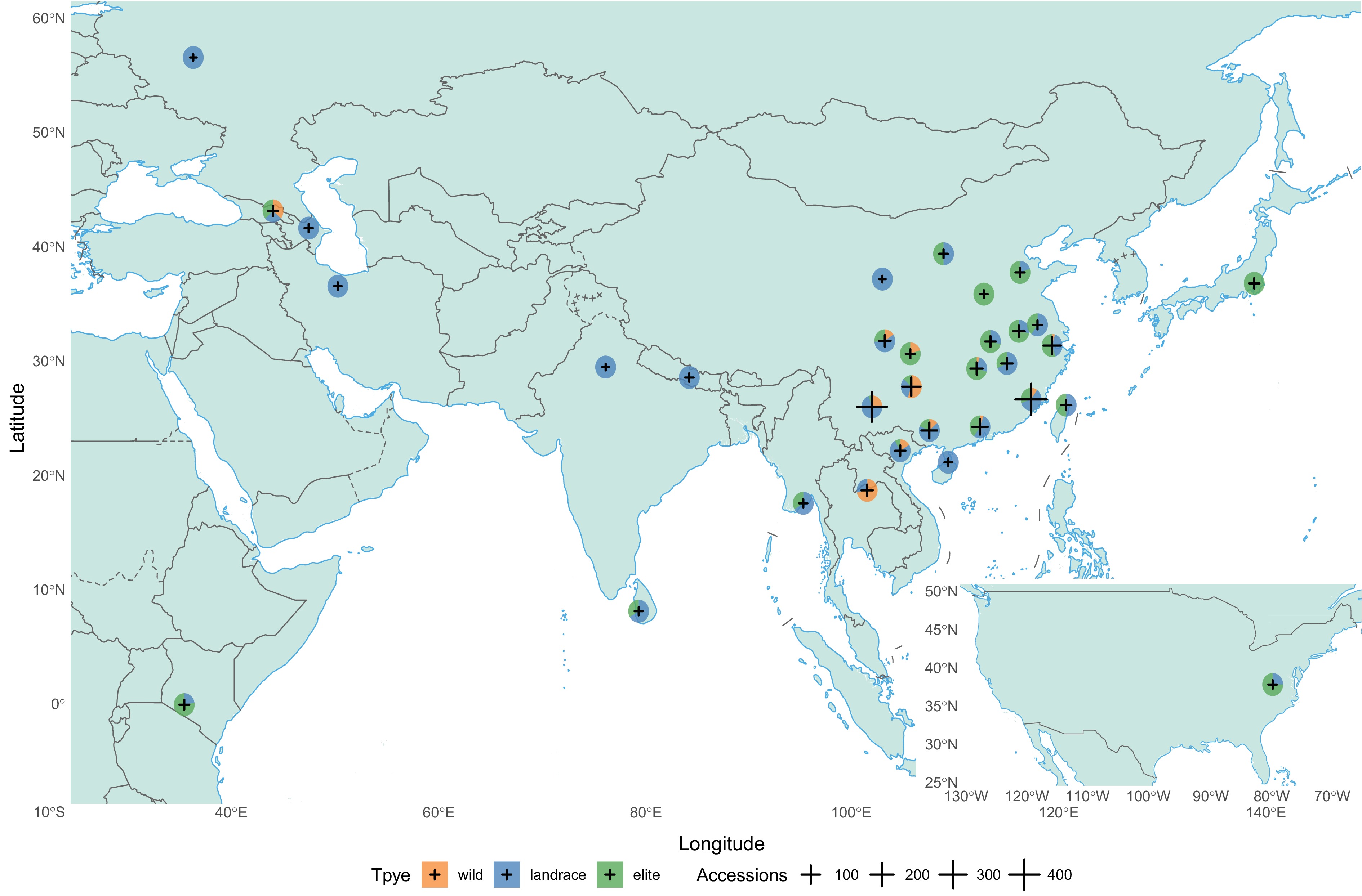

The diverse tea genetic resources, coupled with metabolite detection methodologies, enable the identification of metabolic quantitative trait loci (mQTL) which would further lead to a better location for the allele responsible for metabolites in tea plants. Bulked segregant RNA sequencing (BSR-Seq) analysis on the F1 population by crossing 'Jinxuan' and 'Zijuan' guided to CsFAOMT1 and CsFAOMT2 responsible for O-methylated catechins[91]. A high-density genetic map constructed using an F1 population derived from 'Yingshuang' and 'Beiyao Danzhu' revealed 25 stable QTLs associated with catechins and caffeine across multiple years. Notably, QTLs on chromosomes 3, 11, and 15 were consistently linked to ECG and EGCG, suggesting the presence of conserved regulatory hubs for catechin biosynthesis[92]. The dynamic accumulation of theanine was mapped to QTLs on chromosome 3 (qThea-3.1, qThea-3.2) through multi-year phenotypic and metabolic data[93]. This locus co-localized with CsTSI (theanine synthetase), whose allelic variations were strongly correlated with theanine content across diverse germplasm. Analysis of anthocyanin-rich tea accessions uncovered CsMYB75 and CsGSTF1 as key regulators of anthocyanin glycosylation, which directly influences leaf color and stress responses. Similarly, RNA-seq, BSR-seq, and bulked segregant analysis by sequencing (BSA-seq) were performed on the same F1 population as Jin et al. built[91] showed CsMYB75's positive regulation of anthocyanin, a 181-bp InDel in CsMYB75 promoter co-segregating with leaf color, providing a reference for anthocyanin mechanism in new purple cultivar creation[94]. However, previous studies using the tea germplasm to map mQTL have merely been pursued on a handful of metabolites or inadequate genotypic data. A large-scale combined metabolomics and natural population genetics study of tea plants is needed to understand its genetic and metabolic landscape.

Yu et al. pioneered the integration of transcriptome-derived 925,854 SNPs and untargeted metabolomics to dissect genetic and metabolite diversity across 136 Chinese tea accessions[95]. Phylogenetic clustering resolved five major groups, with CSA cultivars exhibiting distinct enrichment of flavanols, flavonol glycosides, and phenolic acids, while CSS-derived groups accumulated methylated catechins (EGCG3''Me). Selective sweep analysis highlighted regions like F3'5'H (flavonoid hydroxylation) and AMPDA (caffeine biosynthesis), linking genetic divergence to metabolic specialization. However, this study was limited to comparing different subpopulations without analyzing SNPs directly in association with metabolites, thus lacking allele pinpointing. This gap underscores the necessity of mGWAS (metabolic genome-wide association studies). mGWAS represents a transformative approach to deciphering the genetic architecture underlying certain kinds of metabolite accumulation in tea plants, enabling high-resolution mapping of loci regulating secondary metabolites critical to flavor and health benefits[96,97]. Furthermore, the focus on specific classes of secondary metabolites fails to capture the full metabolic landscape, potentially omitting regulatory networks influencing interrelated pathways. By integrating high-throughput metabolomic profiling with genome-wide variation data, mGWAS provides a comprehensive representation of the genetic and metabolic characteristics that define chemical diversity, bridging the gap between genomic variation and biochemical phenotypes[98]. RAD-seq (restriction site-associated DNA sequencing) is an efficient method to obtain SNP by sequencing restriction sites. For instance, Yamashita et al. combined RAD-seq-derived SNPs with metabolomic data from 150 tea accessions, identifying moderate prediction accuracies for catechins using genomic models, though lower accuracies were observed for amino acids and chlorophylls[97]. GWAS detected 80−160 top-ranked SNPs associated with key metabolites, pinpointing candidate genes such as flavonoid biosynthetic enzymes and transporters while revealing limited power to detect subpopulation-specific alleles linked to caffeine synthase pathways. Expanding on this, Fang et al. employed AFSM (amplified-fragment single-nucleotide polymorphism and methylation) on 191 accessions, uncovering 307 stable SNPs across three seasons associated with theanine, caffeine, and catechins[96]. Their work highlighted pleiotropic SNPs influencing multiple metabolites and validated enzymes like FLS, UGT, and MYB, reinforcing the role of flavonoid pathway genes. Besides the sequencing of DNA, the transcriptome is an efficient way to analyse variant information in coding sequences. Zhang et al. leveraged RNA-seq and Hi-C-based genome assembly of an ancient tea plant to map mQTLs for catechin biosynthesis, functionally validating allelic variants in CsANR, CsF3'5'H, and CsMYB5 that modulated enzymatic efficiency and metabolite flux[6]. However, these approaches, while powerful, are inherently constrained by their reliance on SNP-based markers (e.g., RAD-seq, AFSM) and RNA-seq, which overlook structural variations such as indels, copy-number variations, and transposable elements that dominate tea plants large, repetitive genome. These limitations underscore the necessity of complementary long-read resequencing, and pan-genomic approaches to resolve structural diversity and expand metabolite profiling. Recent advances in mGWAS leveraging pan-genomic resources have demonstrated the effectiveness of integrating SV detection with metabolomic profiling to unravel the genetic basis of key agronomic traits[45,66]. Using the original 'PanMarker' software with a graphical pangenome and previously published metabolic data[95], Chen et al. highlighted allelic variants in cytochrome B-561 (CYB-561), WDR, and DELLA as strongly correlated with catechin biosynthesis, while a serine-to-glycine substitution in CsDIOX altered substrate binding affinity, modulating catechin diversity[66]. Complementary studies employing large-scale metabolomics identified 2,837 metabolites across 215 tea accessions, with mGWAS uncovering 6,199 and 7,823 mQTLs in young and mature leaves, respectively[98]. A candidate substrate-product pairs (CSPP) network was constructed in this study, which aided in the annotation of unknown metabolites. These analyses revealed galloylation as the predominant enzymatic conversion in tea with key loci such as CsCCoAOMT (caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase) driving methylation of ECG, validated via cis-eQTL, and enzymatic assays. Moreover, UDP-glycosyltransferases CsUGTa and CsUGTb were likewise implicated in flavonoid diversification through allele-specific glycosylation patterns. Recently, 1,562 annotated metabolites across 300 tea accessions were analyzed through mGWAS, which identified 135,176 SNPs significantly correlated with metabolites. In this research, transcription factors such as MYB36, bHLH62, and NY-YB were identified as key regulators of EC synthesis[45]. Together, mGWAS have demonstrated irreplaceable efficiency in pinpointing genes encoding key enzymes of metabolic pathways and their upstream regulators through a genome-wide association strategy that resolves genetic variation and metabotype, providing a powerful tool for systematically unravelling the multilevel regulation of plant-specific metabolic networks. However, for highly heterozygous tea plants, mixed resequencing in different populations, or even between subpopulations with reproductive isolation, is likely to result in false-positive localization results. Furthermore, some metabolites with low heritability, but which play an important role in the quality of the tea, cannot be detected by GWAS. Therefore, the selection of populations and the precise counting of metabolites at multiple points over many years is a sufficient condition for the success of GWAS.

-

Cultivated across numerous countries with a millennia-old history of domestication and utilization, the tea plant has developed substantial natural genetic variations and undergone intensive artificial selection through prolonged agricultural practices[54]. The global popularity of tea consumption stems primarily from its unique repertoire of specialized metabolites that confer both appealing flavor profiles and scientifically validated health-promoting properties[2]. Recent advancements in metabolomic profiling and next-generation sequencing technologies have revolutionized germplasm utilization by enabling large-scale characterization of genetic information, thereby facilitating systematic investigations into metabolic pathway regulations and agronomic trait architectures (Fig. 3)[66,98]. Unfortunately however, the current in-depth research on the molecular genetics and biochemistry of tea plants has not directly contributed to the practice of breeding, and the identification of a large number of functional genes could not be translated into applications. What's more, the substantial quantity of resequencing and metabolomic studies has resulted in data redundancy, resulting in a lack of avenues for timely integration and standardized use of the data. Hence, future research directions in tea germplasm exploration could prioritize three strategic domains: (1) Establishment of tea plant genetic engineering techniques, including the application of transgenes, precision editing of single bases or fragments, and the establishment of tea plant mutant libraries, and so on. These functional genomics studies can accelerate the breeding application of basic research; (2) Comprehensive data mining through multi-omics integration (metabolomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, etc.) coupled with emerging single-cell omics approaches, which offer novel insights for subsequent experimental validation of metabolic regulatory networks[99]. Furthermore, a database of comprehensive data is necessary for resource sharing[100]; (3) Implementation of hormone metabolomics to elucidate how ecological factors orchestrate secondary metabolism via phytohormone signaling cascades, particularly focusing on stress-induced metabolite biosynthesis. These integrated strategies will enable precision breeding programs tailored for enhanced metabolite production and climate resilience.

This work was supported by Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 324QN192), the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (ASTIP) (Grant No. 1610212024002), and Yunnan Key Laboratory of Tea Germplasm Conservation and Utilization in the Lancang River Basin (Grant No. 202449CE340010).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: the presented paper was conducted in collaboration of all authors. draft manuscript writing and revision: Liu Y, Li S, Xu X; manuscript review: Zhao X, Wang S, Li X, Ma J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Yiming Liu, Shixuan Li

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu Y, Li S, Xu X, Ma J, Li X, et al. 2025. Harnessing functional metabolite diversity in tea plant germplasm: from metabolic signatures to quality-oriented breeding. Beverage Plant Research 5: e034 doi: 10.48130/bpr-0025-0025

Harnessing functional metabolite diversity in tea plant germplasm: from metabolic signatures to quality-oriented breeding

- Received: 01 April 2025

- Revised: 19 May 2025

- Accepted: 05 June 2025

- Published online: 07 November 2025

Abstract: Tea plant (Camellia sinensis) exhibits remarkable metabolic diversity in their specialized secondary metabolites, such as catechins, theanine, caffeine, and volatile compounds, defining both ecological adaptability and therapeutic value. Environmental factors and phytohormonal regulation are proven as critical modulators of secondary metabolism, with certain signaling pathways coordinating stress-responsive metabolite production through transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. The development of chromosome-scale genome assemblies, pangenome, and 3D chromatin map resources has revealed extensive genomic variations that lead to metabolic distinctions. While metabolomics approaches including nuclear magnetic resonance, mass spectrometry, and emerging ion mobility techniques have enabled comprehensive profiling of flavor-related compounds, challenges persist in linking metabolic signatures to genetic determinants across diverse germplasms. Population genomics studies through metabolic genome-wide association have identified key quantitative trait loci and allelic variants governing metabolite accumulation. This review integrates recent metabolomic and genomic advancements to construct a roadmap for harnessing tea's functional metabolite diversity through germplasm resources, elucidating the biochemical and genetic foundations of quality traits to advance precision breeding applications.

-

Key words:

- Tea plant /

- Metabolomics /

- Secondary metabolites /

- Germplasm /

- Genome /

- mGWAS