-

Tea, made from leaves of the plant Camellia sinensis, is one of the most widely consumed beverages worldwide. Black tea and green tea are the most consumed, accounting for 55% and 34% of the world's tea production, respectively[1]. There are also special types of tea, such as Oolong tea, white tea, dark tea, and yellow tea. Tea polyphenols (TPP)—mainly catechins and their derived compounds—are considered the major active constituents of tea, and their mechanisms of action have been reviewed recently[2]. Other known active constituents in tea are caffeine and a unique amino acid, theanine[3].

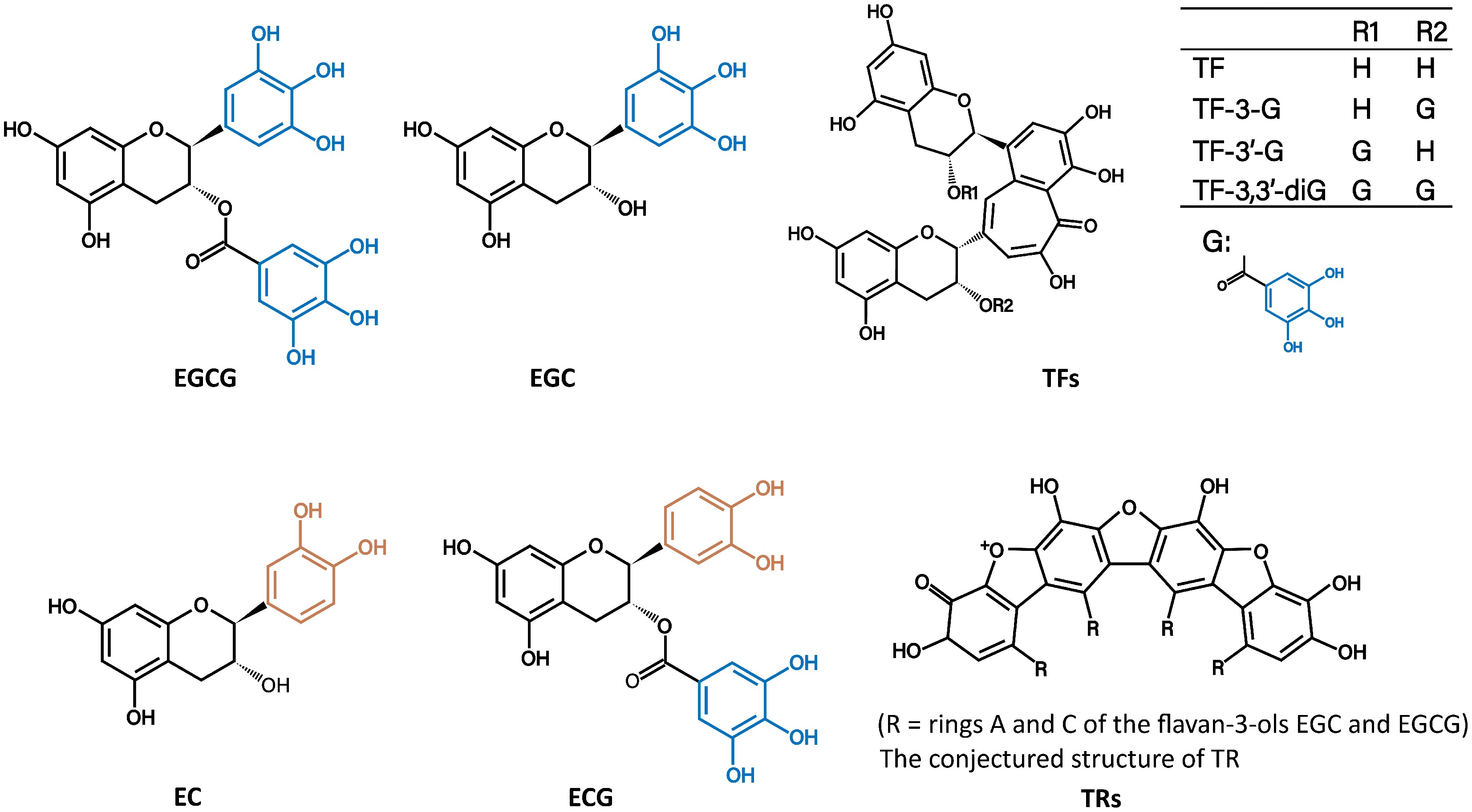

Green tea is an unfermented tea (0%–5% fermentation), and its production process primarily involves fixing, rolling, and drying. The fixing step is crucial, as it uses high heat (steaming or pan-frying) to rapidly inactivate enzymes in tea leaves, effectively preserving the polyphenolic compound. The major tea catechins are (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC), (−)-epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG), and (−)-epicatechin (EC)[3,4]. The structures of these catechins are shown in Fig.1. A typical brewed green tea beverage (e.g., 2.5 g tea leaves in 250 mL of hot water) contains 240–320 mg of catechins, of which 60%–65% is EGCG, as well as 20–50 mg of caffeine[3,4]. Black tea is a fully fermented tea (80%–90% fermentation), and its production process involves withering, rolling, fermentation, and drying, with fermentation being the critical step in determining its quality. During the fermentation process, most of the catechins are oxidized through the catalysis of endogenous polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase, and polymerized to form the dimeric theaflavins (TFs), polymeric thearubigins (TRs), and even higher molecular weight polyphenols[3−5]. The major TFs are TF, TF-3-gallate, TF-3'-gallate, and TF-3,3'-digallate, while TRs are a group of poorly characterized large molecular weight polymers (MW range 2–40 kDa). The structures of some of the black tea polyphenols are shown in Fig. 1. In black tea, catechins, TFs, and TRs each account for 3%–10%, 1%–6%, and 5%–20% of the dry weight, respectively, depending on the tea variety and processing methods.

Figure 1.

The structures of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC), (−)-epicatechin (EC), (−)-epicatechin-3-gallate(ECG), theaflavins (TFs), and thearubigins (TRs, conjecture from Haslam E. Phytochemistry 2003, 64: 61–73).

Tea has been used for thousands of years in China, initially for medicinal purposes, and then became a popular beverage associated with many beneficial health effects. However, modern scientific evidence for the health effects of tea has only started to accumulate in the past four or five decades. Consumption of tea is associated with a reduction in mortality due to cardiovascular diseases (CDVs) in large cohort studies, lower risk for certain types of cancers, and lower incidence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) in most of the studies[6−8]. In addition, there are numerous reports on the possible beneficial effects of different types of tea based mainly on results from laboratory studies. On the other hand, there are also concerns about the possible deleterious effects of tea consumption, such as pesticide residues and heavy metal contaminations, as well as whether tea consumption affects nutrient absorption. In this article, these issues will be discussed together with the effects of tea processing on the health effects of tea.

-

The beneficial health effects of tea and its constituents have been studied extensively in animal models and humans[6−12]. Numerous related studies have also been conducted in vitro, yielding data on the alteration of various signaling molecules by tea constituents and proposed mechanisms of action[13]. However, results from in vitro studies cannot be extrapolated to predict their actions in internal organs of animals, because of the bioavailability issue and the differences between the environment of cells in vitro and cells in vivo[2]. Even if a health effect can be demonstrated in animal models, it cannot be extrapolated to humans because of species differences, and the doses of the agent used in animal models are usually higher than those in humans. Therefore, the health effects of tea consumption in humans should be judged based on evidence from human studies, especially large, long-term cohort studies. Studies in animal models and in vitro may provide supporting evidence and mechanistic information for further verification in humans.

Prevention of cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and mortality

-

Based on the above criteria, the most convincingly observed health-beneficial effect of tea consumption is the prevention of CVDs[6−8]. In a recent meta-analysis of 38 prospective cohort data sets, Kim and Je showed that a moderate level of tea consumption (1.5–2.0 cups/day) reduced the risk of mortalities from all-cause, CVDs, and cancer. For CVDs mortality reduction, a plateau was observed (ES, 0.88–0.90) at tea consumption levels of 1.5–3.0 cups/day, and interestingly, a sustained significant reduction in mortality was observed at higher intake levels[8]. The greatest risk reduction for all-cause mortality was observed for the consumption of 2.0 cups/day (ES, 0.9), and for cancer mortality was the consumption of 1.5 cups/day (ES, 0.92); whereas additional consumption did not show a significant further reduction in the risk of death. It appears that the benefit in reducing mortality due to CVDs is more consistent than the reduction of cancer mortality, and both are major contributors to all-cause mortality. Most of these large cohort studies were conducted in China and Japan, where green tea was mainly consumed. In a cohort study in England, where black tea was consumed, tea consumption (two or more cups/day) was found to be associated with a lower mortality rate[9].

The prevention of CVDs by tea is also supported by many human and animal studies: (1) both green and black tea polyphenols have been shown to decrease lipid absorption, blood LDL-cholesterol level, and blood pressure; (2) black tea and green tea consumptions have been demonstrated to improve endothelium–dependent vasodilatation (elevating eNOS); and (3) the antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative, and anti-platelet effects of TPP in the cardiovascular system can also play important preventable roles[14−16].

Concerning the prevention of cancer by tea, there is strong evidence in animal studies; however, results are inconsistent in human studies[7]. This is probably due to differences in the etiology of different types of cancer, which is compounded by the different genetic and environmental factors of different populations. The evidence appears to be stronger for the prevention of certain specific types of cancer. For example, meta-analyses on the association between tea consumption and the risk of cancer found that frequent consumption of green tea was associated with lower risk of oral cancer (RR = 0.798)[17], lung cancer in women (RR = 0.78)[18], and colon cancer (OR = 0.82)[19].

Prevention of obesity and diabetes

-

The prevention of CVDs is closely related to the prevention of obesity and T2D. Many randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted, and most of them showed a body weight-reduction effect of tea in overweight or obese individuals[20−22]. For example, in subjects with obesity and metabolic syndrome, consumption of green tea (four cups/day) for eight weeks decreased body weight, LDL-cholesterol level, and oxidative stress[21]. In a study with overweight adults, daily ingestion of 600-900 mg tea catechins (with < 200 mg caffeine) for 90 d decreased body fat content[22].

Many RCTs and cohort studies have shown that consumption of tea (3–4 or more cups/day) decreased the risk of T2D[7,23]. However, in the Shanghai Women's and Men's Health Studies (n = 52,315), tea consumption was dose-dependently associated with an increase in T2D risk (HR = 1.2)[24]. In T2D patients, green tea extracts had no effect on HbA1c, glucose, and insulin levels in 6 RCTs[25].

The lowering of body weight gain and alleviating diabetic symptoms by tea have been demonstrated in many studies in animal models, commonly induced by a high-fat diet or genetically in the db/db mice[7]. In these studies, the effective prevention of fatty liver diseases was associated with lower weight gain. These could be supporting evidence for the beneficial effects of tea consumption in reducing body weight in overweight or obese individuals and alleviating diabetic symptoms. What is puzzling is the positive association between tea consumption and risk of T2D in the Shanghai studies[24]. It is also unclear why tea consumption had no effect on glucose and insulin levels in diabetic patients in the above-mentioned RCTs[25].

Other health effects of tea

Neuroprotective effects

-

Many studies in Japan and China showed that frequent tea consumption was associated with lower prevalence of cognitive impairment[26−30]. For example, recent studies in China showed that regular green tea consumption was associated with reduced cognitive decline, better cognitive functions, and lower levels of Alzheimer's disease-related biomarkers[28,29]. A recent meta-analysis of 18 studies comprising a total of 58,929 participants indicated that green tea consumption was inversely associated with cognitive impairment, showing an OR of 0.63, with the greatest benefit observed in individuals aged 50–69 years[30]. Some of the neuroprotective activities may be attributed to theanine, a unique amino acid in tea with high bioavailability that can pass the blood-brain barrier. Theanine has been shown to have stress-reducing and anti-anxiety properties[31,32].

Increasing muscle mass and functions

-

The reduction of muscle loss and improvement of muscle function by TPP in individuals with sarcopenia have been reviewed in many studies[12]. For example, in an RCT, ingestion of EC-enriched green tea extract (600 mg/d) for 12 weeks was found to increase isokinetic flexor muscle and handgrip strength and to attenuate muscle loss[33]. In a study with older adults, supplementation with tea catechins and essential amino acids after resistance exercise improved skeletal muscle mass[34]. TPP has also shown similar effects during muscle disuse in aged rats[35].

Reducing uric acid levels

-

Green tea consumption has been shown to decrease uric acid levels. A cross-sectional study conducted in a Beijing community with 1,583 participants found that the prevalence of hyperuricemia was 14.1% (20.2% in men and 7.4% in women)[11]. The study showed a negative correlation between tea consumption and hyperuricemia in men (OR of 0.56, high vs low), but not in women. A randomized crossover study involving ten healthy Japanese subjects also suggested that, after alcohol consumption, green tea extract can enhance uric acid and xanthine/hypoxanthine excretion[36]. The hypouricemic activities of different types of tea have been demonstrated in hyperuricemia models in mice and rats[37].

Decreasing inflammation and other disease markers

-

Green tea consumption has been associated with lower levels of blood inflammation markers and related diseases[10]. In an RCT involving 56 obese hypertensive participants, those who received green tea extract (379 mg/d) for three months showed a significant reduction in serum tumor necrosis factor α (14.5%) and C-reactive protein (26.4%), along with improvements in parameters associated with insulin resistance[38]. In another study on patients with end-stage renal disease, a three-month supplementation of catechins (455 mg/d) reduced hemodialysis-induced production of hydrogen peroxide, hypochlorous acid, proinflammatory cytokines, and atherosclerotic factors[39].

Antibacterial and antiviral activities

-

The antibacterial effects of tea extracts have been demonstrated in many studies[40,41]. The commonly consumed tea brews can selectively inhibit and kill many bacterial species. The effects are mostly due to the activities of catechins. Sustained tea consumption has been shown to cause salivary microbiota shift[42]. Many studies have demonstrated that catechins and tea extracts can inhibit the enzyme activities and kill cariogenic bacteria such as Streptococcus mutans. The antibacterial activities of tea catechins have been proposed as the basis for the beneficial effects of tea consumption or even tea mouthwash against dental caries, gingivitis, and periodontitis observed in animal and human studies[43,44]. Tea constituents have direct access to the microorganisms in the oral cavity.

EGCG and other catechins have been shown to possess antiviral activities against a variety of viruses, such as hepatitis C virus, hepatitis B virus, influenza virus, and human papillomavirus[45]. EGCG mainly inhibits the early stages of viral infection, such as attachment, entry, and membrane fusion. During the pandemic of COVID-19, the antiviral activities against SARS-CoV-2 by tea catechins were extensively investigated, and the possible mechanisms of action have been discussed[46]. Most of the studies were conducted in vitro. Interestingly, Bettuzzi et al.[47] reported that ten SARS-COV-2 patients (swab-positive), while awaiting hospitalization, were treated for 15 d at home with two sessions of inhalation of catechin aerosol plus three catechin capsules per day (total catechins: 840 mg, including 595 mg EGCG), and all patients recovered fully without symptoms at a median of 9 d (ranged 7–15 d). The key factor for the success of this study could be the inhalation of catechin aerosol, which was delivered directly to the respiratory tract and the lungs. After drinking or gargling tea, the levels of EGCG and other catechins in the oral/nasal/pharyngeal cavity could be high enough to protect against viral infection[46]. It has been shown in Japan that daily gargling a tea catechin solution significantly lowered the incidence of influenza infection in the elderly[48]. These interesting studies need to be repeated in studies with more subjects, and the research can also be extended to other anti-viral studies in humans.

-

In previous sections, the possible health effects of tea consumption in general were discussed; most information was derived from studies on green tea, and some from black tea. This section will discuss the manufacture and features of some specialized teas: Oolong tea, white tea, dark tea, and yellow tea. The distinct processing methods of tea production shape the unique chemical compositions, tastes, and flavors of different types of tea. Comparisons of the beneficial health effects of different types of tea will be discussed. Also discussed are bottled tea and bubble tea beverages.

Manufacturing and specific characteristics of white tea, Oolong tea, dark tea, and yellow tea

-

White tea, which has been advertised to be better than green tea, is a lightly fermented tea (fermentation degree of 0%–10%) made by minimal processing that involves only withering and drying, preserving most of the constituents and natural flavor of the tea leaves[49]. The tea cells are relatively intact, and the endogenous enzymes catalyze mild protein hydrolysis leading to the formation and accumulation of amino acids, such as tyrosine, phenylalanine, and glutamate[50].

Yellow tea (fermentation degree of 10%–20%) is usually made from older tea leaves by fixing, rolling, yellowing, and drying. The yellowing process is the critical step; the high humidity and hot temperature promote the enzyme hydrolysis of proteins to form and increase the content of free amino acids such as theanine, glutamate, and aspartate[51,52]. During yellowing, TPP undergoes partial hydrolysis of the ester bond to form EGC, EC, and gallate, and reduces the bitterness of the tea.

Oolong tea, popular in China and Japan, is a semi-fermented tea (fermentation degree of 30%–60%). The manufacturing process includes withering, fine manipulation, fixing, rolling, and drying. Fine manipulation is the key process of Oolong tea production, damaging the leaf margin cells, leading to the production of color compounds and presenting green leaves with red edges[53]. The enzymatic reactions in the ruptured cells also produce numerous aromatic volatile substances, providing a sweet floral fragrance[54].

Dark tea is becoming more popular in China. It has a fermentation degree of 85%–100% and is made by withering, fixing, rolling, pile-fermentation, and drying. Pile-fermentation is a unique process involving microorganism fermentation. Under damp heat, microbial and endogenous enzymes catalyze the decomposition, oxidation, hydrolysis, and polymerization of the original tea constituents to form new products such as theabrownins (approximately 12% in Pu-erh tea) and water-soluble polysaccharides[55].

Comparative studies of the health effects of different types of tea

-

Many studies have found and compared some of the health-beneficial effects of different types of tea in rodent models. If the tea samples were from commercial sources, the comparison may not be valid – the sample analyzed may not be representative of the specific type of tea. On the other hand, if the different types of tea were made from the same batch of tea leaves, then the differences are due to the manufacturing process. The activities of the six major types of tea in China—green tea, black tea, Oolong tea, white tea, dark tea, and yellow tea prepared from the same batch of fresh tea leaves—have been compared by Sun et al.[56]. It was found that a 2% Oolong tea brew was more effective than the other five types of tea in decreasing weight gain and altering bile acid metabolism in mice[56]. Another study also found that a 4% commercial Oolong tea was more effective in reducing weight gain and triglyceride levels in rats than black tea, Pu-erh tea, or green tea[57]. The higher activity of Oolong tea may be attributed to newly formed catechin oligomers or 3'-methyl EGCG during the specific fermentation process[58].

Liu et al. reported the hypolipidemic effect of all six types of tea (commercial) in mice fed a high-fat diet, and that white tea had the highest activity[59]. A similar study in rats also found that white tea was most effective in body weight control among the six types of tea, possibly due to the higher catechin content in white tea[60]. The hypouricemic activities of the six types of tea have been demonstrated and compared in hyperuricemic mice or rats; however, no conclusion can be reached on which type of tea is more important[37,61]. In a study on the effects of the six types of commercial tea on DSS-induced colitis in mice, it was found that treatment with tea extracts reduced inflammatory markers in both colon and liver tissues, maintained intestinal barrier integrity, and restored DSS-induced intestinal dysbiosis; fermented tea tended to be less effective[62]. Even though the anti-inflammatory activity of tea catechins has been shown in many studies[60], oral administration of EGCG to mice with inflamed bowel has been shown to aggravate colitis[63].

Summary and mechanistic consideration

-

The possible health effects of different types of tea in humans are difficult to compare, and results are scarce. Meta-analyses found that frequent consumption of green tea was associated with a lower risk of certain types of cancer[17−19]; however, data on black tea are scarce. These results are consistent with many animal studies showing that green, tea due to its higher catechin content, is generally more effective than black tea in the prevention of cancer[7,64].

On the health effects of different types of tea, if the green tea, in which catechins, caffeine, and theanine are the major active components, is used as a base, other active compounds may be produced at the expense of the decrease in catechins. For example, black tea contains less catechins than green tea because they are converted to TFs and TRs, which have very low or null bioavailability and are not absorbed. That is probably the reason why black tea is less efficient than green tea in many studies on cancer and diabetes prevention. However, the unabsorbed TPP in the gastrointestinal tract can exert their binding and redox actions on the epithelial cells and interact with microbiota to produce health-beneficial effects[2]. During the fermentation process of Oolong, yellow, or dark tea, different new products are known to be formed in small quantities; some of them contribute to the unique flavor or taste of the specific types of tea. However, the contribution of these newly formed compounds to the healthy effects of specific tea types has not been clearly elucidated. All types of tea are known to interact with gut microbiota and contribute to the biological activities[65−68]. However, most of the information was derived from correlational studies, and the specific microbiota-mediated health effects of different types of tea need to be further elucidated.

Pre-prepared tea beverages and their health effects

Bottled tea

-

Bottled tea beverages, ready for consumption without the traditional brewing process, are becoming popular, especially among people who have a busy schedule and prefer the taste and flavor. In the making of bottled tea, it is known that EGCG can be converted to gallocatechin gallate (GCG) during high-temperature sterilization. The amount of GCG formed accounts for only 0.84%–1.43% of the total catechins in green tea; whereas in some other bottled tea drinks, such as Hakuyou Oolong tea and Japanese Jenmai tea, the conversion to GCG can reach up to 45% of the total catechins. The stability of catechins is pH-dependent, being more stable under acidic pH. Therefore, ascorbic acid and citric acid are added to increase the acidity. For beverages at a pH below 4.5, the half-life of catechins is three months or longer[69]. During storage, catechins are slowly oxidized to form oligomers, and the content of EC-EGCG dimers is generally used as an indicator of freshness[70]. In addition to lowering the pH, ascorbic acid can also serve as an antioxidant, chelating metal ions and quenching reactive radical species. Ascorbic acid may also form conjugates with catechins. 6-C-Dehydroascorbic acid-EGCG and 8-C-dehydroascorbic acid-EGCG were detected in tea beverages at a concentration ranging from 0.23 to 1.97 µM[71].

As compared to traditionally brewed tea, the bottled tea, with the loss of catechins during processing and storage, would provide fewer health benefits. An additional concern is the presence of sweetening agents (sucrose, high-fructose corn syrup, or sugar substitutes) and other additives for maintaining color, extending shelf life, and enhancing flavor and taste. Frequent and excessive consumption of added sugar is known to be associated with the risk for dental caries, obesity, T2D, and other chronic diseases. 'Sugar-free' products, though calorie-free, often utilize artificial sweeteners, such as aspartame and sucralose, some of which may increase appetite, disrupt gut microbiota, and induce insulin resistance[72]. Thus, all these sweeteners and additives could reduce or overshadow the health benefits of tea, and this issue warrants further investigation.

Bubble tea

-

Bubble tea is a hybrid beverage that used to be called 'milk tea'. Since the 1980s, bubble tea – made of tea, tapioca pearls, and milk, as well as artificial flavoring and preservative agents – has become a popular beverage, especially among young people. The tapioca pearls, a hallmark characteristic of bubble tea, are prepared by soaking refined starch-balls (pearls) in sucrose solution or high-fructose corn syrup, contributing 150–200 kcal per serving of bubble tea[73]. Commercially popular 'bubble tea' is often made from pre-prepared tea-extract powder and non-dairy creamers. The latter contain saturated and trans-fats, which are known to increase cardiovascular disease risks[74]. Formulating products with authentic dairy, real fruit, and freshly brewed tea in an approach known as 'industrial novel tea beverages', would be an improvement. However, the presence of added sugar, artificial sweeteners, or refined starch, as well as synthetic additives such as ethyl vanillin, benzaldehyde, and sodium benzoate, remains a health concern.

-

Because of the beneficial effects of tea in the prevention of obesity and overweight, green tea extracts have been developed as a popular dietary supplement for body weight reduction. However, as reviewed previously[7], there are many case reports of liver toxicity of green tea extract-based dietary supplements taken by individuals for the purpose of weight reduction. For example, after taking 41–108 g of tea extract in total doses, elevation of serum aminotransferase activities was observed, and the elevated levels returned to normal after stopping the supplements. In some cases, upon rechallenging with the dietary supplement, further liver injury occurred[7]. The toxicity has been attributed to EGCG, although other catechins may also contribute to the toxicity. This overdose toxicity is consistent with laboratory experiments; for example, daily administration of 500−750 mg of EGCG/kg (body weight) by intragastric infusion (i.g.) caused dose-dependent liver toxicity, and the toxicity was more severe in fasting mice. In fasting dogs, a single bolus oral dose of 500 mg of EGCG/kg caused gastrointestinal damage and morbidity. However, the same dose given to pre-fed dogs in divided doses showed no toxicity[75]. In the Minnesota Green Tea Trial in postmenopausal women with green tea extracts (652 mg catechins, including 421 mg EGCG, twice a day), about 5% of the women in the treatment group showed elevated serum aminotransferase activity, and the elevated levels returned to normal with the cessation of green tea extract intake[7]. Nevertheless, toxicity due to the consumption of tea as a beverage has not been reported in humans, even though gastrointestinal irritation due to drinking tea, especially green tea, is known to occur. The tea beverage is usually ingested throughout the day, not at high doses as a bolus dose, as in the intake of supplements, which may be the reason for the lack of toxicity.

Possible effects of tea consumption on nutrient absorption

-

Although a weight reduction effect of tea consumption has been reported in animals fed a normal diet, the effects of moderate tea consumption on the absorption of macronutrients and fat-soluble vitamins in individuals on a normal or caloric-restricted diet need to be investigated.

Because of the ion-chelating potential of tea polyphenols, tea consumption has been suspected to decrease iron absorption. Indeed, such decrease has been observed with non-heme iron (from plant-based food), but not with heme iron (from animal-based food)[76]. For individuals or populations on a vegetarian diet, consumption of tea at mealtime could be an issue of concern.

It has been suspected that tea consumption may bind calcium and decrease its absorption to affect bone health. Contrary to this suspicion, many animal studies have shown that treatment with TPP resulted in higher bone mass, lower bone resorption, and greater bone strength[77,78]. Even though results from animal studies suggest a positive correlation between tea consumption and maintaining bone mineral density, it is not clear whether such a correlation exists in humans. The relationship between tea consumption and risk of osteoporosis has been investigated in more than ten studies in different parts of the world, and the results are inconsistent[78]. It appears that moderate tea consumption by individuals with adequate calcium intake would not affect calcium absorption and bone health. Whether heavy tea drinking would affect calcium absorption still remains to be investigated.

Pesticide residues and other contaminations

-

In the cultivation of tea, pesticides are used to control pests, and pesticide residues in tea have always been a concern globally. Based on the reported high insecticide residue levels in different tea samples, serious health concerns have been raised. For example, Feng et al.[79] reported that, out of the 223 Chinese tea samples analyzed, 198 samples contained pesticide residues and 39 samples had residue levels that exceeded the European Union (EU) maximum residue limits (MRL). A survey of pesticide residues in 116 imported tea samples on the Tokyo market from April 1992 to March 2010 showed that the pesticide detection rate in green tea (90%) was similar to Oolong tea (89%) and was lower in black tea (49%)[80].

Since the beginning of this century, the presence of octachlorodipropyl ether, 9,10-anthraquinone, and perchlorate in tea has become a new pollutant of concern. Identifying the residues and sources of these substances is essential for reducing pollution levels. Tang et al.[81] reported that a high level of octachlorodipropyl ether in Chinese tea came from the smoke of the mosquito coils in the tea workshop. An exceptionally high level of 9,10-anthraquinone (0.55 mg/kg) in black tea samples was detected, far exceeding the EU MRL of 0.02 mg/kg[82]. The anthraquinone contamination may come from exogenous sources, such as smoke exposure and paper-based packaging, as 9,10-anthraquinone is utilized in papermaking[83].

Although there are significant amounts of pesticide residues and other contaminants in tea, the assessment of the health risks should be based on the amounts of these compounds ingested through tea drinking. Different from grains, vegetables, and fruits, tea is mostly brewed first and then drunk by the tea consumer. Therefore, only the pesticides that leach to the tea infusion during tea brewing are ingested to affect health. During tea brewing, the leaching of pesticides from tea leaves is affected by their water solubility, the water temperature, and the surface area of tea leaves[84]. Currently, the correction factor of leaching rate is added to the commonly used risk quotient (RQ) method for risk assessment.

Based on the RQ method, many studies indicated that the potential health risk caused by pesticide residues through the consumption of tea infusion was negligible[85]. There were a few studies on the combined risk assessment of multi-pesticide residues. Studies on combined exposure to organophosphorus pesticide residues for tea drinking showed that there were no health concerns based on acute dietary exposure to tea infusion in a probabilistic way[86]. Lu et al.[87] conducted a systematic probabilistic co-exposure risk assessment on multiple pesticide residues in 1,629 tea samples and showed that the health risk posed to tea drinkers was negligible. Even though the conclusion of the recent risk assessment – based on models developed from animal data – appears to be appropriate, the possible accumulation of lipophilic pesticide residuals in long-term heavy tea consumers still needs to be investigated.

Microplastics have been detected in tea, present throughout the entire process from cultivation and processing to brewing[88]. The concentration of microplastics ranges from 70 to 3,472 particles per kg, with the highest levels found during the rolling phase of processing. The microplastic intake for children and adults through tea consumption is estimated to be 0.0538–0.0967 particles and 0.0101–0.0181 particles per kg body weight per day, respectively, with the exposure risk considered extremely low. However, studies indicate that a plastic teabag steeped in boiling water releases over 109 microplastic particles[89], which may pose potential health risks, and efforts to alleviate this problem are needed.

Fluoride, a common contaminant in tea, accumulates primarily through soil uptake. Concentrations in tea infusions vary significantly by type, with brick tea containing the highest levels (4.78 mg/L), followed by black (2.73 mg/L), green (1.37 mg/L), and white tea (0.49 mg/L)[90]. Adults consuming 1,500 mL/day of high-fluoride tea (e.g., brick tea) may exceed the WHO's recommended daily fluoride limit (4 mg/day), increasing the risk of adverse health effects.

Heavy metals

-

Heavy metals in tea, such as lead (Pb) and aluminum (Al), can be another health concern. Depending on the heavy metal content in the soil and water of the production area, there are large variations in heavy metal levels in tea produced in different areas. For example, the Pb content in tea from China, Turkey, and Iran was reported to be higher than that from Sri Lanka, Nigeria, and Japan, with Iranian black tea containing the highest amount of Pb, ranging from 8.38 ± 0.42 to 15.48 ± 0.58 μg/g[91,92]. Another comparative study on tea from China, Japan, and India found the highest average Pb content of 8.4 ± 3.2 mg/kg in Japanese tea, while Indian tea had the lowest average Pb content of 1.0 ± 0.7 mg/kg[93]. Studies in China have shown a fluctuation in the Pb content of Longjing tea, with a gradual rise in Pb content—from 0.63 to 1.45 mg/kg—during 1996 to 1999, followed by a stable level around 2.0 mg/kg from 2001 to 2004[94], and then a decrease to as low as 1 mg/kg[95]. The decrease was likely due to the banning of leaded gasoline, which decreased the Pb level in automobile exhaust and road dust. The more common sources of Pb are soil, chemical fertilizers, and pesticides[96].

The tea plant is known to efficiently absorb Al from the soil, and the Al content in mature tea leaves can reach 30,000 mg/kg[97]. The actual exposure risk of Pb or Al in tea depends on their quantity in the tea infusion. Based on the Pb leaching rate in tea (ranging from 12.6%–39.3%) and Pb level in tea (0.09–1.5 mg/kg), the calculated Pb level in a 200 mL green tea infusion brewed from 2.0 g tea leaves is 0.002 mg, which is much lower than the PTWI (the provisional tolerable weekly intake) of 0.025 mg/kg bw for Pb[93]. The leaching rate of Al is 17%–42%, but more than 90% of Al exists at a low-toxic organic state, and the contents of the toxic mononuclear Al and hydroxyl polymeric Al are less than 18% of total Al[98]. In summary, the dissolution of heavy metals in tea during brewing is low, their toxic forms are limited, and regular tea consumption should not pose a health risk to consumers.

-

In this article, the effects of tea consumption on human health were discussed. Data from human studies consistently demonstrate the association between tea consumption and reduced risk of CVDs, obesity, diabetes, and certain types of cancer. These are the most studied diseases in large human cohort studies and RCTs on tea and health. Such association is supported by many studies in animal models and cell lines to reach the conclusion that tea consumption prevents the development of these diseases. This conclusion is also consistent with the understanding of the biochemical properties and physiological actions of tea constituents, as well as the etiology of these diseases.

Some human studies suggest that tea consumption alleviates cognitive decline and muscle loss in seniors, hyperuricemia, bacteria or virus-induced diseases, and oxidative stress and inflammation in tissues. These possibilities are supported by results from laboratory studies. Additional human and animal studies may provide stronger evidence for these benefits of tea consumption.

Many of the above results were derived from studies with green tea in Asian populations, as well as some studies conducted with black tea and other types of tea. The effects of different types of tea have been compared in many animal studies. However, the results of these studies have not provided sufficient evidence, nor are there enough human data to assess whether Oolong tea, white tea, dark tea, or yellow tea is more or less effective than green tea in providing health benefits to tea consumers. The development of different types of tea is part of the Chinese tea culture. Like wine in France, the color, aroma, and subtle taste determine the quality and appearance of the tea. In bottled tea and bubble tea, the presence of added sugar, artificial sweeteners, or refined starch, as well as flavoring agents and preservatives, is likely to mitigate or overshadow the health benefits of tea. This topic needs further investigation.

Pesticide residues, heavy metals, and other contaminants in tea can be a health concern. Therefore, it is important for tea producers and regulatory agents to follow the regulations and laws. Risk assessment, based on the levels of these contaminants in tea brews, suggests that regular tea consumption should not pose a health risk. This brief risk assessment is for the general population and may not apply to individuals with certain abnormal physiological functions or diseases. Regarding whether tea consumption can affect nutrient absorption, it should not be a concern in well-nourished populations. However, it could be a problem for certain individuals. For example, tea drinking can decrease the absorption of non-heme iron from plant-based food, and this factor needs to be considered by vegetarians.

In conclusion, tea is an enjoyable and healthy beverage; consumers can select the tea types that they like. Additional research would further elucidate the health benefits and assess some of the health concerns of tea consumption.

This review article was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32372757).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization, writing − review and editing: Yang CS; writing − original draft: Yang CS, Yang M, Zhou L, Kan Z, Fu Z, and Zhang X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yang M, Zhou L, Kan Z, Fu Z, Zhang X, et al. 2025. Beneficial health effects and possible health concerns of tea consumption: a review. Beverage Plant Research 5: e035 doi: 10.48130/bpr-0025-0036

Beneficial health effects and possible health concerns of tea consumption: a review

- Received: 18 June 2025

- Revised: 31 August 2025

- Accepted: 22 September 2025

- Published online: 13 November 2025

Abstract: The health effects of tea made from tender shoots of tea plant (Camellia sinensis) have been studied extensively. This review article assesses the evidence for the health effects of tea consumption in humans, using results from studies in animal models and in vitro as supportive evidence and for mechanistic understanding. The evidence is solid for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases, obesity, diabetes, and some types of cancer. The prevention of cognitive decline and muscle loss in seniors, as well as the antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and hypouricemic activities, are all promising topics for additional studies in humans. Most of these data were obtained from studies with green tea. Black tea and other types of tea have also shown some beneficial health effects. Comparative studies on the health effects of the six major types of Chinese tea have been conducted in animal models; however, no conclusive results can be projected to humans. The presence of sugar, artificial sweeteners, or refined starch, as well as flavoring agents and preservatives, in bottled or bubble tea beverages may cause health concerns in reducing or overshadowing the beneficial health effects of tea. Pesticide residues, heavy metals, and other contaminants in tea can be health concerns. However, risk assessment based on the levels of these contaminants in tea brews suggests that regular tea consumption should not pose a health risk. In summary, tea is a healthy beverage; consumers can select the tea types that they enjoy. Additional research would further elucidate the health benefits and assess some of the health concerns of tea consumption.

-

Key words:

- Tea consumption /

- Health effects /

- Human relevance /

- Tea beverages /

- Pesticide residues and heavy metals